“We Are Having a Huge Problem with Compliance”: Exploring Preconception Care Utilization in South Africa

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Population, Recruitment, and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis and Theoretical Framework

2.5. Trustworthiness

2.6. Findings

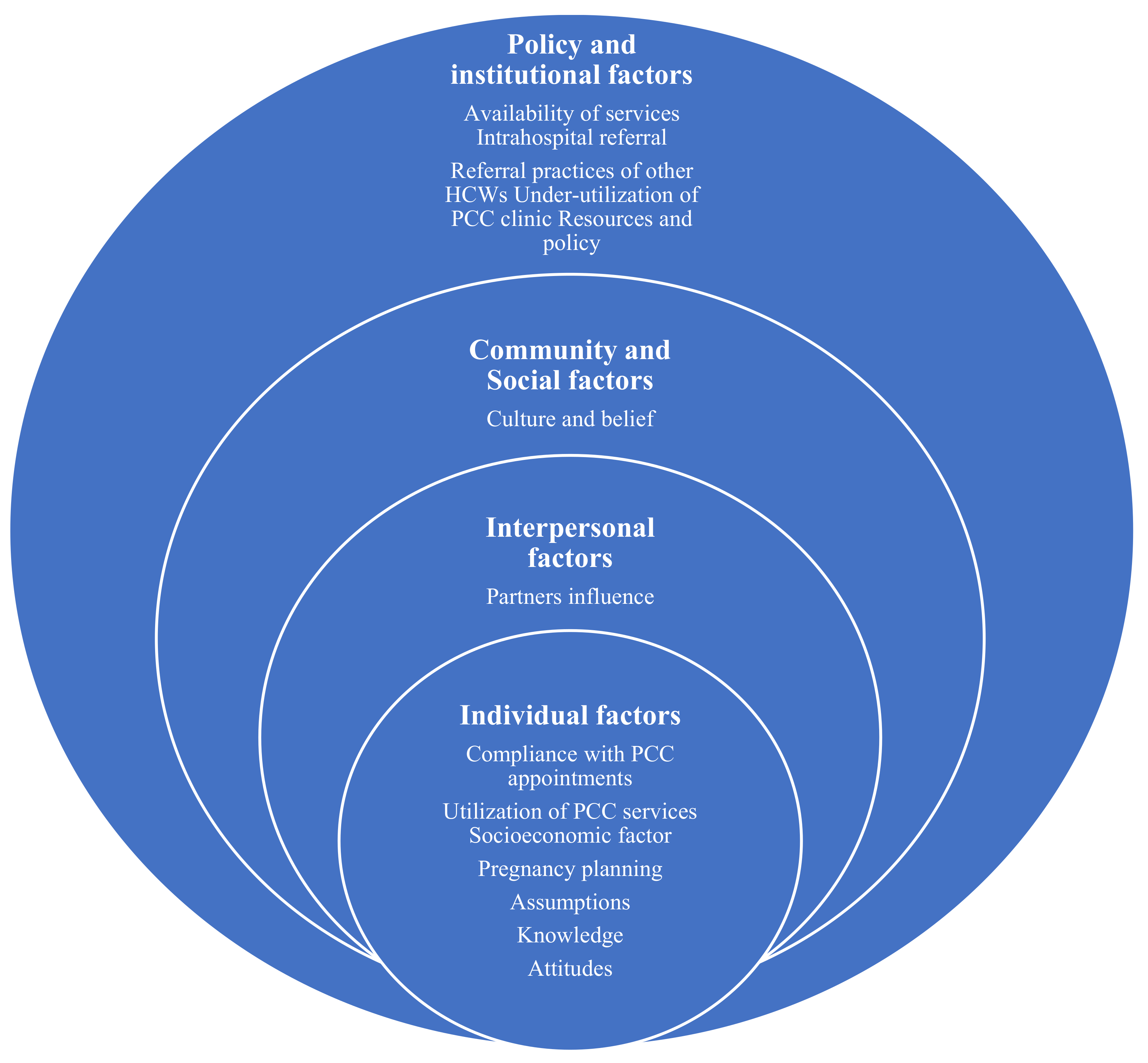

2.7. Using the Social-Ecological Model to Explore PCC Utilization

2.8. Individual-Level Factors

2.9. Poor Compliance with PCC Appointments

“We advise our patients even on discharge that before you decide to fall pregnant again, please come and see us in our pre-pregnancy clinic … we tell them it is documented in their discharge summaries … we are big on PCC, but I don’t think it happens everywhere”.(HC3)

“The doctor told me I must come to the hospital to discuss it if I plan to fall pregnant because the drugs, I am taking are so dangerous to the child. So that the doctor can control the drugs, but I never come to the hospital because I didn’t plan to fall pregnant until I noticed I was four months pregnant”.(PC1)

“I was informed that when I am about to fall pregnant, I should come because I have got a heart problem so that they can discuss what I am going to do. I did not come back to the hospital before I became pregnant. I did not follow what they told me, but when I realize that I was pregnant, I did stop the warfarin. I didn’t plan to fall pregnant. It just happened”.(PC2)

“We are having a huge problem with compliance; I would say one-third of the patients don’t pitch after an appointment is given. A lot wouldn’t come, yet some would come to get more information because they want to plan another baby. some will not pitch because they don’t see the relevance, but I would like to see the number increasing”.(HC1)

“We do see patients who are told by us on discharge after delivery to come for PCC, who have not who have actually fallen pregnant and then come to me, the reason is that many pregnancies are unplanned”.(HC3)

2.10. Contraceptive and Folic Acid Utilization Experience among Women

“I have used contraceptives before. I was on the three months injection, Depo-Provera … I stopped because I was bleeding and having an allergic reaction, it itches a lot”.(PC1)

“I was on Traphasil 2009 to 2011, but I defaulted I didn’t have any reason, I just didn’t want those pills anymore”.(PC21)

“The doctor gave me folic acid after I became pregnant. I was on folic acid during pregnancy, not before pregnancy”.(PC14)

“… no one informed me that I should take folic acid before pregnancy, I did not know about it, I started taking folic acid after I became pregnant”.(PC13)

“What is folic acid? … No, I didn’t take anything, I didn’t take folic acid before pregnancy …”(PC23)

2.11. Unplanned Pregnancy

“Three-quarters of our pregnancies are unplanned. In fact, in KwaZulu-Natal, 70% of our patients come as unplanned or unintended pregnancies, so they do not come to you in time. They are coming to you when they are already pregnant”.(HC1)

“Most patients reason for not seeking PCC is that pregnancy was just unplanned, they have not been on contraception. This is not a challenge for local only, is a worldwide challenge … majority of the pregnancy are unplanned”.(HC3)

“It was not my plan to fall pregnant, it just happened, and I was shocked when I noticed that I was already four months gone”.(PC1)

“I was on Traphasil, the tablet … then well it didn’t work properly I don’t know why it didn’t work I can say due to stress I don’t know”.(PC13)

2.12. Women’s Attitude towards PCC Information

“Most of the time, we women think we understand everything, and we don’t need more information of which we have the wrong information. If we take time to find information… understand and use it things will be better”.(PC3)

“… I will rather say we don’t understand the information given to us like most of us don’t follow the instructions because we don’t understand it like seriously, we don’t understand … most of us even if you can tell us about something, we don’t want to know more. Yes, it is our lack of knowledge, sometimes we don’t understand that language (medical language), and we have already given up”.(PC20)

2.13. Assumptions Made by Women about Healthcare Workers and PCC

“It is not right we cannot be able to tell the nurses that we want to fall pregnant because they use to tell us that as we are cardiac patients, we are not allowed to fall pregnant now and again. Therefore, it is easier for me to come here already pregnant … it is better when we are already married because the nurses are always complaining about everything. I should not ask for PCC”.(PC15)

“The sisters told me to come when I plan to fall pregnant … I did not come for PCC before I fell pregnant because the nurses will shout at me if I come to tell them that I would want to fall pregnant”.(PC18)

2.14. Socioeconomic Factors

“… there are patient’s issues where patients don’t have resources to get to the hospital because of lack of transport, and a lot of them are not working”.(HC3)

“… sometimes patients just did not come for PCC due to financial thing the hospital or clinic is too far for them to get to”.(HC1)

2.15. Interpersonal Level Factors

2.16. Women’s Partners’ Influence

“Sometimes you find that the challenge is not from the patients but from the partner who doesn’t understand why she needs to come to the hospital now that she not pregnant because PCC is not a concept that everybody is aware of”.(HC3)

“For me, my man got no time … … he is working and could not get time off work, and we are supposed to come together”.(PC22)

2.17. Community and Social Level Factors

2.18. Culture and Belief

“… some culture doesn’t believe in English medicine and involving those things when one is planning pregnancy. But I think that every woman needs to take care of their life. Like in my culture, we believe that you can have a miscarriage if you tell someone that you want to fall pregnant because of this I don’t think I can come for PCC”.(PC20)

“I have never used contraceptives before … I don’t like it, and I don’t believe that I have to use contraceptives. I don’t know if it might happen for me to have a baby; it will happen; I can’t stop it anyway … it is just what I believe in”.(PC23)

2.19. Institutional and Policy Level Factors

2.20. Availability of PCC Services and Intrahospital Referral of Women

“We have the dedicate pre-pregnancy clinic here, so patients are referred to us from the obstetric clinic here, the high-risk clinic, the fetal-medicine clinic, and on few occasions, we normally get outbounds coming in from another hospital”.(HC1)

“… we are usually asked to review cardiac patients regarding a potential pregnancy … we do have in-hospital referral because loads of women with many severe conditions are managed in this hospital”.(HC2)

“… we see patients with serious medical conditions, who have delivered their babies here, so before discharge, we counsel them about family planning and place them on appropriate contraceptives”.(HC4)

2.21. PCC Referrals and Screening from the Base Hospitals

“I do get calls from other institutions for patients with losses and patients with medical problems. They do get referred occasionally from the base hospitals but not in the kind of numbers that I would like to see because I see patients after they have fallen pregnant, which is sometimes a bit late”.(HC3)

“… if people don’t refer, then we will not see enough patients, we get few referrals from the base hospitals for the pre-pregnancy care”.(HC1)

2.22. Under-Utilization of PCC Clinic

“There are huge benefits of PCC, and I would say that our PCC clinic should be more utilized. Unfortunately, our PCC clinic is under-utilized because people are not in the habit of referring patients to the clinic … it will make a huge difference if patients are referred. Right now, there are months I might not see any patients”.(HC3)

“… the problem with the clinic is that it is under-utilized because HCWs in the other disciplines do not identify women adequately, do not counsel women about fertility issues, so we actually lose the opportunity to refer these patients to our clinic so that they can be accessed before pregnancy”.(HC4)

2.23. PCC Material and Resources

“Why can’t we have something like mom connect (a WhatsApp application for pregnant women) for non-pregnant women … everybody got a smartphone, and we have WhatsApp, messages will be sent about the importance of PCC”.(HC3)

“… am not aware of any pamphlets, posters or any other PCC materials, we need those, we don’t have access to the internet so if you want to give a patient literature to take home that they can read and exchange with their family is very difficult for us to do that”.(HC5)

“There is a lack of knowledge from the health care worker perspective about the importance of seeing patients preconceptionally … doctors in particular and nurses are not fully aware of the value of PCC because they think they have bigger problems. So, we think that PCC is nothing important, but I think it is a big mistake … there is no PCC in-service education, workshops, and training, PCC is not given enough emphasis”.(HC3)

“… health workers outside of obstetrics and gynaecology poorly understood contraception, they only know contraindication to some of the contraception. For example, in the rheumatology clinic, a patient may be told you can’t use the combined oral contraceptive because you are at risk for venous problems. We stop there but shouldn’t we tell the patient what they can do, we are telling them what they can’t use, but we are not telling them what they can use”.(HC2)

2.24. PCC Policy and Guidelines

“We have national guidelines on how to treat HBP in pregnancy. We need something similar. PCC directives should come from higher up so that people will have to do it. There are no policy and guidelines, and we need one”.(HC3)

“There isn’t a PCC guideline, nationally or from the local department of health, so non am not aware of any … but there is the maternity care guideline which is a South African guideline that is made for Primary Health Care, it does mention the issue of PCC, but that is not sufficient”.(HC2)

3. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Meeting to Develop a Global Consensus on Preconception Care to Reduce Maternal and Childhood Mortality and Morbidity; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; p. 9241505001. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/78067/9789241505000_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- World Health Organization. Preconception Care: Regional Expert Group Consultation; WHO: New Delhi, India, 2014; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/205637/B5124.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Shawe, J.; Delbaere, I.; Ekstrand, M.; Hegaard, H.K.; Larsson, M.; Mastroiacovo, P.; Stern, J.; Steegers, E.; Stephenson, J.; Tydén, T. Preconception care policy, guidelines, recommendations and services across six European countries: Belgium (Flanders), Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2015, 20, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Biratu, A.K. Addressing the High Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes through the Incorporation of Preconception Care (PCC) in the Health System of Ethiopia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2017. Available online: https://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/24859/thesis_andargachew%20kassa%20biratu.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Osborn, D.; Cutter, A.; Ullah, F. Universal Sustainable Development Goals; Stakeholder Forum; The UN Development Program: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/1684SF_-_SDG_Universality_Report_-_May_2015.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Sijpkens, M.K.; van Voorst, S.F.; de Jong-Potjer, L.C.; Denktaş, S.; Verhoeff, A.P.; Bertens, L.C.; Rosman, A.N.; Steegers, E.A. The effect of a preconception care outreach strategy: The Healthy Pregnancy 4 All study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Ekem, N.N.; Lawani, L.O.; Onoh, R.C.; Iyoke, C.A.; Ajah, L.O.; Onwe, E.O.; Onyebuchi, A.K.; Okafor, L.C. Utilisation of preconception care services and determinants of poor uptake among a cohort of women in Abakaliki Southeast Nigeria. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 38, 739–744. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, K.; Elbashir, I.M.H.; Ibrahim, S.M.; Mohamed, A.K.M.; Alawad, A.A.M. Knowledge, attitude and practice of preconception care among Sudanese women in reproductive age about rheumatic heart disease at Alshaab and Ahmad Gassim hospitals 2014–2015 in Sudan. Basic Res. J. Med. Clin. Sci. 2015, 4, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Mutale, P.; Kwangu, M.; Muchemwa, C.M.K.; Silitongo, M.; Chileshe, M.; Siziya, S. Knowledge and preconception care seeking practices among reproductive-age diabetic women in Zambia. Int. J. Transl. Med. Res. Public Health 2017, 1, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kassie, A. Assessment of Knowledge and Experience of Preconception Care and Associated Factors among Pregnant Mothers with Pre Existing Diabetes Mellitus Attending Diabetic Follow Up Clinic at Selected Governmental Hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018. Ph.D. Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018. Available online: http://213.55.95.56/bitstream/handle/123456789/13486/Aychew%20Kassie.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Demisse, T.L.; Aliyu, S.A.; Kitila, S.B.; Tafesse, T.T.; Gelaw, K.A.; Zerihun, M.S. Utilization of preconception care and associated factors among reproductive age group women in Debre Birhan town, North Shewa, Ethiopia. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, C. Utilization of Preconception Care Services among Women of Reproductive Age in Kiambu County, Kenya. Ph.D. Thesis, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. Available online: https://ir-library.ku.ac.ke/handle/123456789/18676 (accessed on 29 March 2020).

- Fekene, D.B.; Woldeyes, B.S.; Erena, M.M.; Demisse, G.A. Knowledge, uptake of preconception care and associated factors among reproductive age group women in West Shewa zone, Ethiopia, 2018. BMC Women’s Health 2020, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goshu, Y.; Liyeh, T.; Ayele, A. Preconception Care Utilization and its Associated Factors among Pregnant Women in Adet, North-Western Ethiopia (Implication of Reproductive Health). J. Women’s Health Care 2018, 7, 2167-0420. [Google Scholar]

- Dlamini, B.B.; Nhlengetfwa, M.N.; Zwane, I. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Towards Preconception Care Among Child Bearing Women. Int. J. Health Nurs. Med. 2019, 2, 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Olowokere, A.; Komolafe, A.; Owofadeju, C. Awareness, knowledge and uptake of preconception care among women in Ife Central Local Government Area of Osun State, Nigeria. J. Community Med. Prim. Health Care 2015, 27, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wanyonyi, M.K.; Abwalaba, R.A. Awareness and Beliefs on Preconception Health Care Among Women Attending Maternal & Child Health Services at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital in Eldoret, Kenya. J. Health Med. Nurs. 2019, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayinka, O.A.; Achi, O.T.; Amos, A.O.; Chiedu, E.M. Awareness and barriers to utilization of maternal health care services among reproductive women in Amassoma community, Bayelsa State. Int. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2014, 6, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Seman, W.A.; Teklu, S.; Tesfaye, K. Assessment of the knowledge, attitude and practice of residents at tikur anbesa hospital about preconceptional care 2018. Ethiop. J. Reprod. Health 2019, 11, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Tokunbo, O.A.; Abimbola, O.K.; Polite, I.O.; Gbemiga, O.A. Awareness and perception of preconception care among health workers in Ahmadu Bello University teaching university, Zaria. Trop. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 33, 149–152. [Google Scholar]

- Ayele, A.D.; Belay, H.G.; Kassa, B.G.; Worke, M.D. Knowledge and utilisation of preconception care and associated factors among women in Ethiopia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 78. [Google Scholar]

- Batra, P.; Higgins, C.; Chao, S.M. Previous adverse infant outcomes as predictors of preconception care use: An analysis of the 2010 and 2012 Los Angeles mommy and baby (LAMB) surveys. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 1170–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, V.K.; Amamoo, M.A.; Anderson, A.D.; Webb, D.; Mathews, L.; Rowley, D.; Culhane, J.F. Barriers to women’s participation in inter-conceptional care: A cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Kallner, H.K.; Danielsson, K.G. Prevention of unintended pregnancy and use of contraception—important factors for preconception care. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2016, 121, 252–255. [Google Scholar]

- Temel, S.; Birnie, E.; Sonneveld, H.; Voorham, A.; Bonsel, G.; Steegers, E.; Denktaş, S. Determinants of the intention of preconception care use: Lessons from a multi-ethnic urban population in the Netherlands. Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, J.; Li, G.; He, X.; Ma, F.; Meng, Q.; Cao, Q.; Meng, Y.; Howson, C. Factors influencing the quality of preconception healthcare in China: Applying a preconceptional instrument to assess healthcare needs. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 360. [Google Scholar]

- Charaf, S.; Wardle, J.L.; Sibbritt, D.W.; Lal, S.; Callaway, L.K. Women’s use of herbal and alternative medicines for preconception care. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 55, 222–226. [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Qualitative Research; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Todes, A. New African suburbanisation? Exploring the growth of the northern corridor of eThekwini/KwaDakuza. Afr. Stud. 2014, 73, 245–270. [Google Scholar]

- Lehohla, P. Census 2011: Population Dynamics in South Africa; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015; pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N.; Fisher, E. Ecological models of health behavior. Health Behav. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 5, 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, L.; Gauvin, L.; Raine, K. Ecological models revisited: Their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nurs. Open 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lindgren, B.-M.; Lundman, B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 56, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Asresu, T.T.; Hailu, D.; Girmay, B.; Abrha, M.W.; Weldearegay, H.G. Mothers’ utilization and associated factors in preconception care in northern Ethiopia: A community based cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 347. [Google Scholar]

- Bortolus, R.; Oprandi, N.C.; Morassutti, F.R.; Marchetto, L.; Filippini, F.; Tozzi, A.E.; Castellani, C.; Lalatta, F.; Rusticali, B.; Mastroiacovo, P. Why women do not ask for information on preconception health? A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ojukwu, O.; Patel, D.; Stephenson, J.; Howden, B.; Shawe, J. General practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes and views of providing preconception care: A qualitative investigation. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2016, 121, 256–263. [Google Scholar]

- Abrha, M.W.; Asresu, T.T.; Weldearegay, H.G. Husband Support Rises Women’s Awareness of Preconception Care in Northern Ethiopia. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 3415795. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomainen, H.; Cross-Bardell, L.; Bhoday, M.; Qureshi, N.; Kai, J. Opportunities and challenges for enhancing preconception health in primary care: Qualitative study with women from ethnically diverse communities. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002977. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, J.; Boyle, J.; Kirkham, R.; Connors, C.; Whitbread, C.; Oats, J.; Barzi, F.; McIntyre, D.; Lee, I.; Luey, M. Preconception care for women with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A mixed-methods study of provider knowledge and practice. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 129, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Frayne, D.J. Preconception care is primary care: A call to action. Am. Fam. Physician 2017, 96, 492–494. [Google Scholar]

- Poels, M.; Koster, M.P.H.; Franx, A.; van Stel, H.F. Healthcare providers’ views on the delivery of preconception care in a local community setting in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stern, J. Preconception Health and Care: A Window of Opportunity; Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis: Uppasala, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mazza, D.; Chapman, A.; Michie, S. Barriers to the implementation of preconception care guidelines as perceived by general practitioners: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Ukoha, W.C.; Dube, M. Primary health care nursing students’ knowledge of and attitude towards the provision of preconception care in KwaZulu-Natal. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2019, 11, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sijpkens, M.K.; Steegers, E.A.; Rosman, A.N. Facilitators and barriers for successful implementation of interconception care in preventive child health care services in the Netherlands. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, S.D.; Earp, J.A.L. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: Twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 364–372. [Google Scholar]

| Pseudonym | Diagnosis | Age | Highest Education Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCI | Cardiac abnormality | 32 years | Grade 12 |

| PC2 | Cardiac abnormality | 22 years | Grade 12 |

| PC3 | Infertility | 26 years | Diploma |

| PC4 | Infertility | 39 years | Grade 10 |

| PC5 | Infertility and HIV | 32 years | Grade 12 |

| PC6 | Infertility and chronic anaemia | 40 years | Bachelors degree |

| PC7 | Cardiac abnormality, Obesity, and Hypertension | 23 years | Grade 11 |

| PC8 | Cardiac surgery, diabetes, and Hyperthyroidism | 33 years | Grade 12 |

| PC9 | Infertility | 30 years | Grade 12 |

| PC10 | Infertility | 45 years | Grade 11 |

| PC11 | Infertility | 23 years | Grade 12 |

| PC12 | Infertility | 30 years | Grade 12 |

| PC13 | Chromosomal abnormality | 37 years | Grade 12 |

| PC14 | Chromosomal abnormality | 30 years | Grade 10 |

| PC15 | Cardiac abnormality | 26 years | Grade 12 |

| PC16 | Cardiac abnormality | 26 years | Diploma |

| PC17 | Kidney disease and Hypertension | 29 years | Grade 12 |

| PC18 | Cardiac abnormality | 20 years | Grade 10 |

| PC19 | Diabetes and Placenta previa | 35 years | Grade 12 |

| PC20 | Cardiac abnormality and diabetes | 39 years | Grade 12 |

| PC21 | Obesity | 33 years | Grade 12 |

| PC22 | Cardiac abnormality and Hypertension | 30 years | Grade 7 |

| PC23 | Cardiac abnormality and Obesity | 29 years | Grade 12 |

| PC24 | Hypertension and Obesity | 34 years | Diploma |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ukoha, W.C.; Mtshali, N.G. “We Are Having a Huge Problem with Compliance”: Exploring Preconception Care Utilization in South Africa. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061056

Ukoha WC, Mtshali NG. “We Are Having a Huge Problem with Compliance”: Exploring Preconception Care Utilization in South Africa. Healthcare. 2022; 10(6):1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061056

Chicago/Turabian StyleUkoha, Winifred Chinyere, and Ntombifikile Gloria Mtshali. 2022. "“We Are Having a Huge Problem with Compliance”: Exploring Preconception Care Utilization in South Africa" Healthcare 10, no. 6: 1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061056

APA StyleUkoha, W. C., & Mtshali, N. G. (2022). “We Are Having a Huge Problem with Compliance”: Exploring Preconception Care Utilization in South Africa. Healthcare, 10(6), 1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061056