A Comparison of Rehospitalization Risks on Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Patients after Recovery from Acute Coronary Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

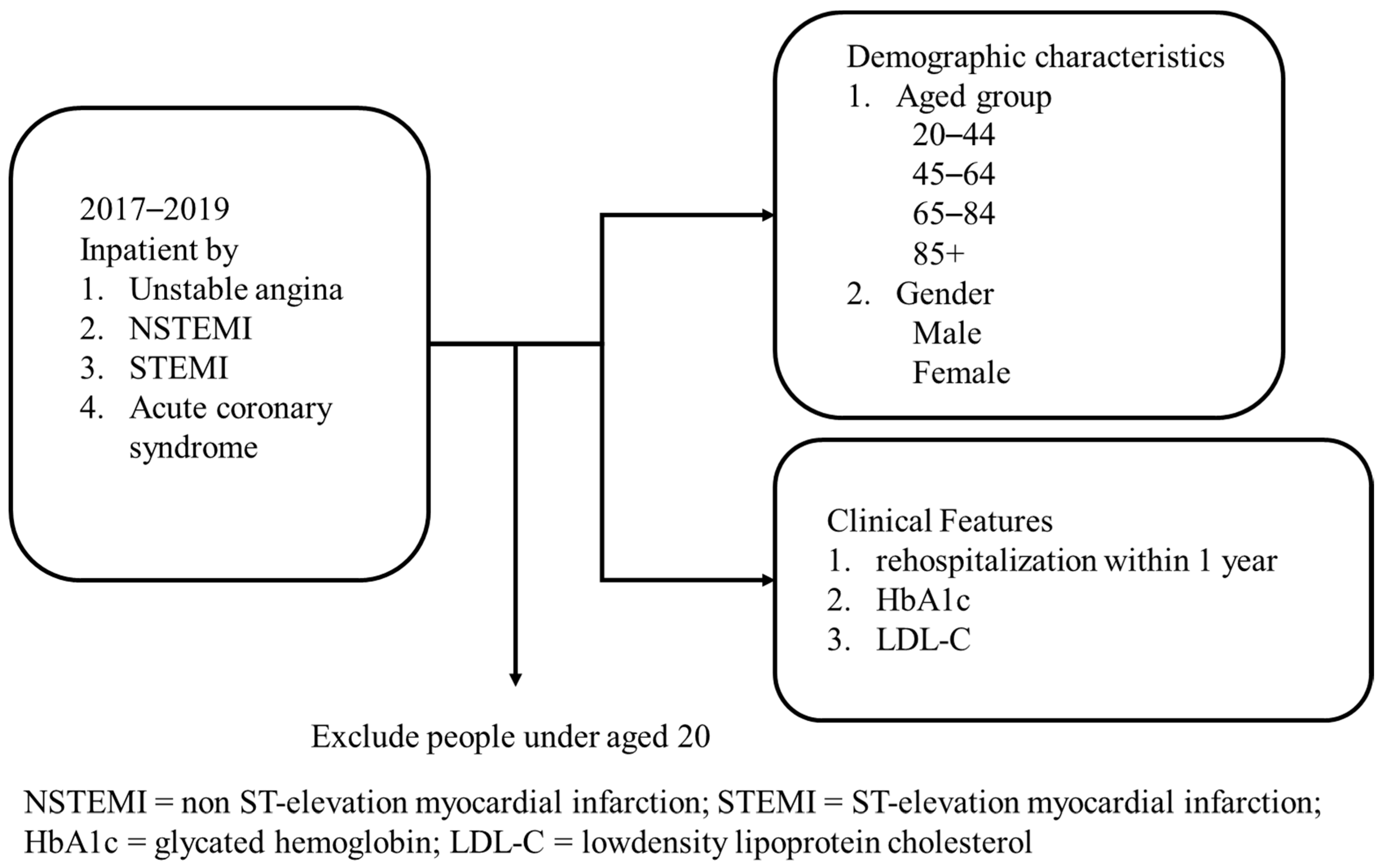

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tochikubo, O.; Ikeda, A.; Miyajima, E.; Ishii, M. Effects of insufficient sleep on blood pressure monitored by a new multibiomedical recorder. Hypertension 1996, 27, 1318–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Tanaka, H. Overtime work, insufficient sleep, and risk of non-fatal acute myocardial infarction in Japanese men. Occup. Environ. Med. 2002, 59, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kageyama, T.; Nishikido, N.; Kobayashi, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; Kabuto, M. Commuting, overtime, and cardiac autonomic activity in Tokyo. Lancet 1997, 350, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Nakamura, K.; Tanaka, M. Increased risk of coronary heart disease in Japanese blue-collar workers. Occup. Med. 2000, 50, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tenkanen, L.; Sjoblom, T.; Harma, M. Joint effect of shift work and adverse life-style factors on the risk of coronary heart disease. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 1998, 24, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkic, K.; Schwartz, J.; Schnall, P.; Pickering, T.G.; Steptoe, A.; Marmot, M.; Theorell, T.; Fossum, E.; Høieggen, A.; Moan, A.; et al. Evidence for mediating econeurocardiologic mechanisms. Occup. Med. 2000, 15, 117–162. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Division, Ministry of Health and Welfare, ROC (Taiwan). Cause of Death Statistics; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Taipei, Taiwan, 2021. Available online: https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/np-1776-113.html (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, D.P.; Hodgson, T.A.; Sinsheimer, P.; Browner, W.; Kopstein, A.N. The economic cost of the health effects of smoking. Milbank Q. 1986, 64, 489–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, W.; Henriette, M.B.; Erik, P. Money for health: The equivalent variation of cardiovascular diseases. Health Econ. 2004, 13, 859–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaziano, T.A. Economic burden and the cost-effectiveness of treatment of cardiovascular diseases in Africa. Heart 2008, 94, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H. Diabetes and stroke. Bull. Taiwan Stroke Soc. 2007, 14, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, N.; Lin, I.F.; Weinstein, M.; Lin, Y.H. Evaluating the quality of self-reports of hypertension and diabetes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2003, 56, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanson, P.; Salenave, S. Metabolic syndrome in Cushing’s syndrome. Neuroendocrinology 2010, 92, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A.; Chua, N.; Khir, R.N.; Chong, P.F.; Lim, C.W.; Rizwal, J.; Rahman, E.A.; Aiza, H.; Arshad, M.K.M.; Ibrahim, Z.O.; et al. Impact of Cholesterol Levels on Acute Coronary Syndrome Mortality in North of Kuala Lumpur. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 249, S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, F.M.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Moye, L.A.; Rouleau, J.L.; Rutherford, J.D.; Cole, T.G.; Brown, L.; Warnica, J.W.; Arnold, J.M.O.; Wun, C.-C.; et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 335, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994, 344, 1383–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, C.P.; Blazing, M.A.; Guigliano, R.P.; McCagg, A.; White, J.A.; Theroux, P.; Darius, H.; Lewis, B.S.; Ophuis, T.O.; Jukema, J.W.; et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2387–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, B.D.; Hans, G.S.; Moran, A.; Scartozzi, M.; John, B.W. Statin dose based on limited evidence. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 759–760. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, J.K. Safety and efficacy of statins in Asians. Am. J. Cardiol. 2007, 99, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiss, D.; Seshasai, S.R.K.; Welsh, P.; Murphy, S.A.; Ho, J.E.; Waters, D.D.; DeMicco, D.A.; Barter, P.; Cannon, C.P.; Sabatine, M.S.; et al. Risk of Incident Diabetes With Intensive-Dose Compared With Moderate-Dose Statin Therapy: A Meta-analysis. JAMA 2011, 305, 2556–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsheikh-Ali, A.A.; Maddukuri, P.V.; Han, H.; Karas, R.H. Effect of the magnitude of lipid lowering on risk of elevated liverenzymes, rhabdomyolysis, and cancer: Insights from large randomized statin trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 50, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juraschek, S.P.; Blaha, M.J.; Whelton, S.P.; Blumenthal, R.; Jones, S.R.; Keteyian, S.J.; Schairer, J.; Brawner, C.A.; Al-Mallah, M.H. Physical fitness and hypertension in a population at risk for cardiovascular disease: The henry ford exercIse testing (FIT) Project. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e001268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spratt, K.A. Managing diabetic dyslipidemia: Aggressive approach. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2009, 109, S2–S7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reddigan, J.I.; Riddell, M.C.; Kuk, J.L. The joint association of physical activity and glycaemic control in predicting cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality in the US population. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 632–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, M.C.; Yen, C.H.; Chen, S.C.; Chen, C.C.; Wang, C.C.; Lee, M.C. Perceived Health Status and Its Related Factors among Elderly Population with and without Obesity in Taiwan. Taiwan Geriatr. Gerontol. 2008, 3, 289–310. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ascenzo, F.; De Filippo, O.; Gallone, G.; Mittone, G.; Deriu, M.A.; Iannaccone, M.; Ariza-Solé, A.; Liebetrau, C.; Manzano-Fernández, S.; Quadri, G.; et al. Machine learning-based prediction of adverse events following an acute coronary syndrome (PRAISE): A modelling study of pooled datasets. Lancet 2021, 397, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Non-Diabetic | Diabetic | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | 0.3374 | |||

| Male | 227 (62.36) | 131 (64.53) | 96 (59.63) | |

| Female | 137 (37.64) | 72 (35.47) | 65 (40.37) | |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 67.49 ± 14.32 | 68.48 ± 14.56 | 66.24 ± 13.95 | |

| Age group | 0.0160 | |||

| 20–44 | 26 (7.14) | 15 (7.39) | 11 (6.83) | |

| 45–64 | 127 (34.89) | 68 (33.50) | 59 (36.65) | |

| 65–84 | 172 (47.25) | 89 (43.84) | 83 (51.55) | |

| 85+ | 39 (10.71) | 31 (15.27) | 8 (4.97) | |

| Principal diagnosis | 0.0064 | |||

| Unstable angina | 34 (9.34) | 10 (4.93) | 24 (14.91) | |

| NSTEMI | 142 (39.01) | 88 (43.35) | 54 (33.54) | |

| STEMI | 175 (48.08) | 99 (48.77) | 76 (47.20) | |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 13 (3.57) | 6 (2.96) | 7 (4.35) | |

| Rehospitalization due to ACS or stroke within 1 year | 0.8246 | |||

| YES | 37 (10.16) | 20 (9.85) | 17 (10.56) | |

| NO | 327 (89.84) | 183 (90.15) | 144 (89.44) | |

| All | Non-Diabetic | Diabetic | p-Value 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0883 | ||||

| Mean | 93.90 | 88.24 | 99.44 | |

| Std | 35.32 | 29.70 | 39.44 | |

| Q1 | 67.00 | 65.00 | 71.00 | |

| Median | 88.00 | 85.00 | 90.00 | |

| Q3 | 110.00 | 105.00 | 120.00 |

| Variable | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Diabetes | 0.8246 | 0.8639 | ||||

| Yes | 1.08 | 0.55–2.14 | 0.94 | 0.46–1.93 | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Gender | 0.7404 | 0.9176 | ||||

| Male | 1.13 | 0.55–2.30 | 0.96 | 0.42–2.17 | ||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Age | 0.2709 | 0.2570 | ||||

| 20–44 | 3.36 | 0.57–19.89 | 4.06 | 0.62–26.41 | ||

| 45–64 | 2.86 | 0.63–12.96 | 3.27 | 0.65–16.54 | ||

| 65–84 | 1.64 | 0.36–7.53 | 1.73 | 0.36–8.18 | ||

| 85+ | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Principal diagnosis | 0.0970 | 0.0890 | ||||

| Unstable angina | 3.11 | 0.34–28.16 | 2.82 | 0.31–26.10 | ||

| NSTEMI | 1.63 | 0.20–13.35 | 1.72 | 0.21–14.36 | ||

| STEMI | 0.88 | 0.11–7.38 | 0.80 | 0.09–6.84 | ||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, H.-P.; Weng, S.-J.; Ho, Z.-P.; Xu, Y.-Y.; Liu, S.-C.; Tsai, Y.-T. A Comparison of Rehospitalization Risks on Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Patients after Recovery from Acute Coronary Syndrome. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061003

Yang H-P, Weng S-J, Ho Z-P, Xu Y-Y, Liu S-C, Tsai Y-T. A Comparison of Rehospitalization Risks on Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Patients after Recovery from Acute Coronary Syndrome. Healthcare. 2022; 10(6):1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061003

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Ho-Pang, Shao-Jen Weng, Zih-Ping Ho, Yeong-Yuh Xu, Shih-Chia Liu, and Yao-Te Tsai. 2022. "A Comparison of Rehospitalization Risks on Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Patients after Recovery from Acute Coronary Syndrome" Healthcare 10, no. 6: 1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061003

APA StyleYang, H.-P., Weng, S.-J., Ho, Z.-P., Xu, Y.-Y., Liu, S.-C., & Tsai, Y.-T. (2022). A Comparison of Rehospitalization Risks on Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Patients after Recovery from Acute Coronary Syndrome. Healthcare, 10(6), 1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061003