Knowledge and Attitudes towards Vitamin D among Health Educators in Public Schools in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Knowledge and Attitudes Scores towards Vitamin D

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.2. Knowledge Regarding Vitamin D

3.3. Attitudes Regarding Vitamin D

3.4. Factors Associated with Knowledge of and Attitudes towards Vitamin D

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Ghamdi, A.S.; Lyer, A.P.; Gull, M. Association between vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and cardiovascular disease in Saudi population. Indian J. Appl. Res. 2017, 7, 601–604. [Google Scholar]

- Sulimani, R.A.; Mohammed, A.G.; Alfadda, A.A.; Alshehri, S.N.; Al-Othman, A.M.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Khan, A.A. Vitamin D deficiency and biochemical variations among urban Saudi adolescent girls according to season. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aftab, S.A.S.; Fouda, M.A. Attitude and awareness of health care providers towards the therapeutic and prophylactic roles of Vitamin D. Mediterr. J. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 5, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Naughton, D.P. Vitamin D in health and disease: Current perspectives. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głąbska, D.; Kołota, A.; Lachowicz, K.; Skolmowska, D.; Stachoń, M.; Guzek, D. The Influence of Vitamin D Intake and Status on Mental Health in Children: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiamenghi, V.I.; de Mello, E.D. Vitamin D deficiency in children and adolescents with obesity: A meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. 2021, 97, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prono, F.; Bernardi, K.; Ferri, R.; Bruni, O. The Role of Vitamin D in Sleep Disorders of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parva, N.R.; Tadepalli, S.; Singh, P.; Qian, A.; Joshi, R.; Kandala, H.; Nookala, V.K.; Cheriyath, P. Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency and Associated Risk Factors in the US Population (2011–2012). Cureus 2018, 10, e2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lips, P.; Cashman, K.D.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B.; Bianchi, M.L.; Stepan, J.; El-Hajj Fuleihan, G.; Bouillon, R. Current vitamin D status in European and Middle East countries and strategies to prevent vitamin D deficiency: A position statement of the European Calcified Tissue Society. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 180, P23–P54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, S.; Strandvik, B. Vitamin D status in healthy children in Sweden still satisfactory. Changed supplementation and new knowledge motivation for further studies. Läkartidningen 2016, 107, 2474–2477. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, R.; Mølgaard, C.; Skovgaard, L.T.; Brot, C.; Cashman, K.D.; Chabros, E.; Charzewska, J.; Flynn, A.; Jakobsen, J.; Kärkkäinen, M.; et al. Teenage girls and elderly women living in northern Europe have low winter vitamin D status. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cashman, K.D.; Dowling, K.G.; Skrabakova, Z.; Gonzalez-Gross, M.; Valtuena, J.; De Henauw, S.; Moreno, L.; Damsgaard, C.T.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Molgaard, C.; et al. Vitamin D deficiency in Europe: Pandemic? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, R.E.K.; Li, L.-J.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Wong, T.Y.; Lamoureux, E.; Sabanayagam, C. Prevalence and Determinants of Suboptimal Vitamin D Levels in a Multiethnic Asian Population. Nutrients 2017, 9, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mithal, A.; Wahl, D.A.; Bonjour, J.P.; Burckhardt, P.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Eisman, J.A.; El-Hajj Fuleihan, G.; Josse, R.G.; Lips, P.; Morales-Torres, J.; et al. Global Vitamin D status and determinants of hypovitaminosis D. Osteoporos. Int. 2009, 20, 1807–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Daghri, N.M. Vitamin D in Saudi Arabia: Prevalence, distribution and disease associations. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 175, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Raddadi, R.; Bahijri, S.; Borai, A.; AlRaddadi, Z. Prevalence of lifestyle practices that might affect bone health in relation to vitamin D status among female Saudi adolescents. Nutrition 2018, 45, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shaikh, A.M.; Abaalkhail, B.; Soliman, A.; Kaddam, I.; Aseri, K.; Al Saleh, Y.; Al Qarni, A.; Al Shuaibi, A.; Al Tamimi, W.; Mukhtar, A.M. Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency and Calcium Homeostasis in Saudi Children. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2016, 8, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Daghri, N.M.; Hussain, S.D.; Ansari, M.G.; Khattak, M.N.; Aljohani, N.; Al-Saleh, Y.; Al-Harbi, M.Y.; Sabico, S.; Alokail, M.S. Decreasing prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the central region of Saudi Arabia (2008–2017). J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 212, 105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlFaris, N.A.; AlKehayez, N.M.; AlMushawah, F.I.; AlNaeem, A.N.; AlAmri, N.D.; AlMudawah, E.S. Vitamin D Deficiency and Associated Risk Factors in Women from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, S.M.; Shati, A.A.; Alqahtani, Y.A.; Dawood, S.A.; Siddiqui, A.F.; Zaki, M.S.A.; Khalil, S.N. Prevalence and Correlates of Vitamin D Deficiency in Children Aged Less than Two Years: A Cross-Sectional Study from Aseer Region, Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. Program Guide for the Operational Plan of the School Health Affairs Administration for the Academic Year 1440/1441 AH, 2019, General Administration of School Health Affairs. Available online: https://departments.moe.gov.sa/schoolaffairsagency/RelatedDepartments/SchoolHealth/Pages/pperational.aspx (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Aljefree, N.; Lee, P.; Ahmed, F. Exploring Knowledge and Attitudes about Vitamin D among Adults in Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2017, 5, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamoudi, L.H.; Almuteeri, R.Z.; Al-Otaibi, M.E.; Alshaer, D.A.; Fatani, S.K.; Alghamdi, M.M.; Safdar, O.Y. Awareness of Vitamin D Deficiency among the General Population in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 2019, 4138187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshamsan, F.M.; Bin-Abbas, B.S. Knowledge, awareness, attitudes and sources of vitamin D deficiency and sufficiency in Saudi children. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Education. Statistical Evidence for the Academic Year 1438/1439 AH. 2018, (pp. 5–85); Jeddah: General Administration of Education in Jeddah Governorate. Available online: https://edu.moe.gov.sa/jeddah/DocumentCentre/Pages/default.aspx?DocId=929d43a6-1e95-48cc-aee0-d198ed2c49c6 (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Raosoft Inc. RaoSoft Sample Size Calculator. 2004. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Aljefree, N.M.; Lee, P.; Ahmed, F. Knowledge and attitudes about vitamin D, and behaviors related to vitamin D in adults with and without coronary heart disease in Saudi Arabia. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.; El-Dahiyat, F.; Jairoun, A.; Raed, R.; Butt, I.; Abdel-Majid, W.; Abdelgadir, H. The sunshine under our skin: Public knowledge and practices about vitamin D deficiency in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. Arch. Osteoporos. 2019, 14, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blebil, A.Q.; Dujaili, J.A.; Teoh, E.; Wong, P.S.; Bhuvan, K. Assessment of Awareness, Knowledge, Attitude, and the Practice of Vitamin D among the General Public in Malaysia. J. Karnali Acad. Health Sci. 2019, 2, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abukhelaif, A.E.; Alzahrani, S.A.; Al-Thobaiti, L.Y.; Alharbi, A.A.; Al, K.M.; Shumrani, Y.S. Assessment level of awareness of Vitamin D deficiency among the public residents of Al-Baha region; Saudi Arabia. Med. Sci. 2021, 25, 2728–2736. [Google Scholar]

- Geddawy, A.; Al-Burayk, A.K.; Almhaine, A.A.; Al-Ayed, Y.S.; Bin-Hotan, A.S.; Bahakim, N.O.; Al-Ghamdi, S. Response regarding the importance of vitamin D and calcium among undergraduate health sciences students in Al Kharj, Saudi Arabia. Arch. Osteoporos. 2020, 15, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotta, S.; Gadhvi, D.; Jakeways, N.; Saeed, M.; Sohanpal, R.; Hull, S.; Famakin, O.; Martineau, A.; Griffiths, C. “Test me and treat me”—Attitudes to vitamin D deficiency and supplementation: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Glatt, D.; White, L.; Iniesta, R.R. Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions towards Vitamin D in a UK Adult Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsadig, Y.M.A.; Imad, A.; Saeed, R.; Khalid, E.T.M. Vitamin D Deficiency and Risk of Hair Loss: Knowledge and Practice of Adult Female Population in Saudi Arabia, 2020. Asian J. Med. Health 2021, 19, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Alwehibi, F.A.; Aldrees, M.A.; Bnfadliah, R.S.; Alshammari, A.S.; Alasgah, S.M.; Ramadan, Y.K. Knowledge and Attitude towards Vitamin D among Saudi Female university students at Princess Nourah University. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2021, 33, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.A.; Eid, M.; Ahmed, S.; Abboud, M.; Sami, B. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding Vitamin D deficiency among community pharmacists and prescribing doctors in Khartoum city, Sudan, 2020. Matrix Sci. Pharma 2020, 4, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejla, L.; Erben, G.R. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease, with emphasis on hypertension, atherosclerosis, and heart failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6483. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami, A.; Farjami, Z.; Ferns, G.A.; Hanachi, P.; Mobarhan, M.G. Evaluation of the knowledge regarding vitamin D, and sunscreen use of female adolescents in Iran. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareef, T.A.; Jackson, R.T. Knowledge and attitudes about vitamin D and sunlight exposure in premenopausal women living in Jeddah, and their relationship with serum vitamin D levels. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2021, 40, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amri, F.; Gad, A.; Al-Habib, D.; Ibrahim, A.K. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding Vitamin D among primary health care physicians in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia, 2015. World J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 1, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Parmenter, K.; Waller, J.; Wardle, J. Demographic variation in nutrition knowledge in England. Health Educ. Res. 2000, 15, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characterization | Total (n = 231) n (%) | Male (n = 112) n (%) | Female (n = 119) n (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| <34 | 26 (11.3) | 21 (18.8) | 5 (4.2) | <0.001 |

| 35–44 | 138 (59.7) | 69 (61.6) | 69 (58) | |

| 45–54 | 58 (25.1) | 19 (17) | 39 (32.8) | |

| 55–62 | 9 (3.9) | 3 (2.7) | 6 (5) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 17 (7.4) | 10 (8.9) | 7 (5.9) | 0.05 |

| Married | 194 (84) | 97 (86.6) | 97 (81.5) | |

| Divorced | 14 (6.1) | 5 (4.5) | 9 (7.6) | |

| Widow | 6 (2.6) | 0 | 6 (5) | |

| Education level | ||||

| Diploma | 66 (28.6) | 26 (23.2) | 40 (33.6) | 0.16 |

| Bachelor | 159 (68.8) | 82 (73.2) | 77 (64.7) | |

| Postgraduate | 6 (2.6) | 4 (3.6) | 2 (1.7) | |

| School stage | ||||

| Primary | 103 (44.6) | 35 (31.3) | 68 (57.1) | <0.001 |

| Intermediate | 65 (28.1) | 34 (30.4) | 31 (26.1) | |

| Secondary | 63 (27.3) | 43 (38.4) | 20 (16.8) | |

| Experience years | ||||

| 1–5 | 30 (13) | 11 (9.8) | 19 (16) | <0.001 |

| 6–10 | 87 (73.7) | 21 (18.8) | 66 (55.5) | |

| 11–15 | 46 (19.9) | 32 (28.6) | 14 (11.8) | |

| 16–20 | 33 (14.3) | 28 (25) | 5 (4.2) | |

| Above 20 | 35 (15.2) | 20 (17.9) | 15 (12.6) | |

| Educational offices | ||||

| North | 59 (25.5) | 8 (7.1) | 51 (42.9) | <0.001 |

| East | 74 (32) | 46 (41.1) | 28 (23.5) | |

| Centre | 36 (15.6) | 27 (24.1) | 10 (8.4) | |

| South | 42 (18.2) | 12 (10.7) | 30 (25.2) | |

| Naseem | 11 (4.8) | 11 (9.8) | 0 | |

| Safa | 9 (3.9) | 8 (7.1) | 0 | |

| Job title | ||||

| Administrator | 168 (72.7) | 77 (68.8) | 91 (76.5) | 0.18 |

| Teacher | 63 (27.3) | 35 (31.3) | 28 (23.5) | |

| Specialization | ||||

| Islamic | 36 (15.6) | 24 (21.4) | 12 (10) | 0.004 |

| Linguistic | 36 (15.6) | 17 (15.2) | 19 (16) | |

| Science | 53 (22.9) | 26 (23.2) | 27 (22.7) | |

| Computer science | 5 (2.2) | 3 (2.7) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Home Economics and Art | 19 (8.2) | 14 (12.5) | 5 (4.2) | |

| Social Science | 31 (13.4) | 16 (14.3) | 15 (12.6) | |

| Management and Economics | 26 (11.3) | 5 (4.5) | 21 (17.6) | |

| Media | 3 (1.3) | 0 | 3 (2.5) | |

| General | 16 (6.9) | 5 (4.5) | 11 (9.2) | |

| No speciality | 6 (2.6) | 2 (1.8) | 4 (3.4) | |

| Knowledge Questions | Total (n = 231) n (%) |

|---|---|

| Have you ever heard of Vitamin D? | |

| Yes | 230 (99.6) |

| No | 1 (0.4) |

| Do you think Vitamin D is important for your health? | |

| Yes | 229 (99.1) |

| No | 0 |

| I don’t know | 2 (0.9) |

| Where did you hear about Vitamin D or Vitamin D deficiency? | |

| Doctor | 148 (64.1) |

| Nurse | 19 (8.2) |

| Internet | 112 (48.5) |

| Family/Friends | 117 (50.6) |

| Pharmacist | 19 (8.2) |

| Newspaper | 36 (15.6) |

| Television | 75 (32.5) |

| Other | 5 (2.2) |

| Where do you think the body gets vitamin D from? | |

| Diet | 70 (30.3) |

| Sun exposure | 114 (49.4) |

| supplements | 62 (26.8) |

| I don’t know | 1 (0.4) |

| All of the above | 155 (67.1) |

| What type of food is a good source of vitamin D? | |

| Vegetables & Fruits | 71 (30.7) |

| Milk | 80 (34.6) |

| Fatty fish (salmon, sardine) | 162 (70.1) |

| Olive oil | 25 (10.8) |

| Egg | 84 (36.4) |

| I don’t know | 19 (8.2) |

| Which of the following you think are the benefits of Vitamin D? | |

| Strong bones | 218 (94.4) |

| Prevents heart diseases | 62 (26.8) |

| It has no benefit | 0 |

| I don’t know | 6 (2.6) |

| Vision | 36 (15.6) |

| Prevents anemia | 39 (16.9) |

| In your opinion which one of the following categories is more at risk of developing Vitamin D deficiency? | |

| Individuals not outdoors often | 63 (27.3) |

| Cover up skin when out | 46 (19.9) |

| Individuals with dark skin | 7 (3) |

| Individuals who avoid sun exposure | 202 (87.4) |

| None of the above | 2 (0.9) |

| I don’t know | 9 (3.9) |

| Vitamin D is synthesized inside our body? | |

| Yes | 172 (74.5) |

| No | 29 (12.6) |

| I don’t know | 30 (13) |

| Factors affecting vitamin D synthesis from sunlight. | |

| Season | 27 (11.7) |

| Skin Pigmentation | 28 (12.1) |

| Sunscreen use | 72 (31.2) |

| Time of day | 75 (32.5) |

| Cloud cover | 38 (16.5) |

| Latitude | 7 (3) |

| Pollution | 23 (10) |

| Smoking | 20 (8.7) |

| High-fat diet | 43 (18.6) |

| None of the above | 13 (5.6) |

| I don’t know | 58 (25.1) |

| Vitamin D helps the absorption of calcium in the body? | |

| Yes | 175 (75.8) |

| No | 10 (4.3) |

| I don’t know | 46 (19.9) |

| Taking Vitamin D supplements reduces the risk of Vitamin D deficiency | |

| Yes | 208 (90) |

| No | 6 (2.6) |

| I don’t know | 17 (7.4) |

| Attitudes Questions | Total (n = 231) n (%) |

|---|---|

| I like to expose myself to sunlight | |

| Agree | 67 (29) |

| Disagree | 91 (39.4) |

| Neither agree or disagree | 73 (31.6) |

| Do you think vitamin D is important for your health? | |

| Yes | 229 (99.1) |

| No | 0 |

| I don’t know | 2 (0.9) |

| The exposure to sunlight is harmful for the skin. | |

| Agree | 81 (35.1) |

| Disagree | 94 (40.7) |

| Neither agree or disagree | 56 (24.2) |

| I am concerned that my current vitamin D levels might be too low. | |

| Agree | 154 (66.7) |

| Disagree | 57 (24.7) |

| Neither agree or disagree | 20 (8.7) |

| I am willing to undergo test for vitamin D if a medical condition demands it | |

| Yes | 230 (99.6) |

| No | 1 (0.4) |

| Socio-Demograhics | Knowledge | p Value | Attitudes | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good Knowledge n = 104 n (%) | Low Knowledge n = 127 n (%) | Positive Attitudes n = 99 n (%) | Negative Attitudes n = 132 n (%) | |||

| Age | ||||||

| <34 | 13 (12.5) | 13 (10.2) | 0.76 | 16 (16.2) | 10 (7.6) | 0.06 |

| 35–44 | 60 (57.7) | 78 (61.4) | 53 (53.5) | 85 (64.4) | ||

| 45–54 | 28 (26.9) | 30 (23.6) | 28 (28.3) | 30 (22.7) | ||

| 55–62 | 3 (2.9) | 6 (4.7) | 2 (2) | 7 (5.3) | ||

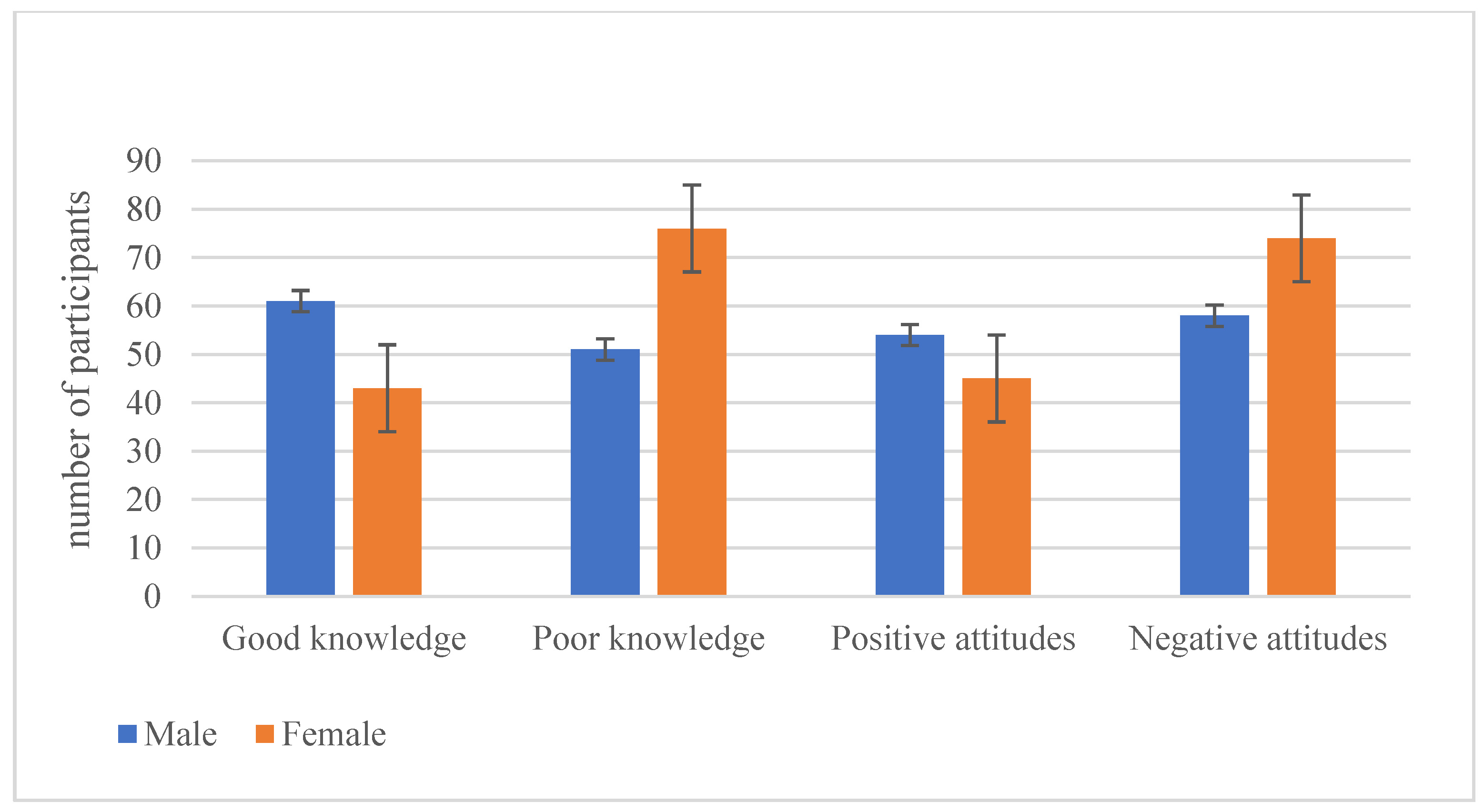

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 61 (58.7) | 51 (40.2) | 0.005 | 54 (54.5) | 58 (43.9) | 0.11 |

| Female | 43 (41.3) | 76 (59.8) | 45 (45.5) | 74 (56.1) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 6 (5.8) | 11 (8.7) | 0.76 | 7 (7.1) | 10 (7.6) | 0.61 |

| Married | 90 (86.5) | 104 (81.9) | 81 (81.8) | 113 (85.6) | ||

| Divorced | 6 (5.8) | 8 (6.3) | 7 (7.1) | 7 (5.3) | ||

| Widow | 2 (1.9) | 4 (3.1) | 4 (4) | 2 (1.5) | ||

| Education level | ||||||

| Diploma | 22 (21.2) | 44 (34.6) | 0.01 | 30 (30.3) | 36 (27.3) | 0.8 |

| Bachelor | 77 (74) | 82 (64.6) | 67 (67.7) | 92 (69.7) | ||

| Postgraduate | 5 (4.8) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (2) | 4 (3) | ||

| School stage | ||||||

| Primary | 43 (41.3) | 60 (47.2) | 0.52 | 44 (44.4) | 59 (44.7) | 0.94 |

| Intermediate | 29 (27.9) | 36 (28.3) | 27 (27.3) | 38 (28.8) | ||

| Secondary | 32 (30.8) | 31 (24.4) | 28 (28.3) | 35 (26.5) | ||

| Experience years | ||||||

| 1–5 | 13 (12.5) | 17 (13.4) | 0.26 | 10 (10.1) | 20 (15.2) | 0.59 |

| 6–10 | 33 (31.7) | 54 (42.5) | 36 (36.4) | 51 (38.6) | ||

| 11–15 | 21 (20.2) | 25 (19.7) | 22 (22.2) | 24 (18.2) | ||

| 16–20 | 20 (19.2) | 13 (10.2) | 17 (17.2) | 16 (12.1) | ||

| Above 20 | 17 (16.3) | 18 (14.2) | 14 (14.1) | 21 (15.9) | ||

| Job title | ||||||

| Administrator | 74 (71.2) | 94 (74) | 0.62 | 76 (76.8) | 92 (69.7) | 0.23 |

| Teacher | 30 (28.8) | 33 (26) | 23 (23.2) | 40 (30.3) | ||

| Specialization | ||||||

| Islamic | 21 (20.2) | 15 (11.8) | 0.18 | 18 (18.2) | 18 (13.6) | 0.8 |

| Linguistic | 12 (11.5) | 24 (18.9) | 17 (17.2) | 19 (14.4) | ||

| Science | 24 (23.1) | 29 (22.8) | 20 (20.2) | 33 (25) | ||

| Computer science | 3 (2.9) | 2 (1.6) | 3 (3) | 2 (1.5) | ||

| Home Economics and Art | 6 (5.8) | 13 (10.2) | 7 (7.1) | 12 (9.1) | ||

| Social Science | 16 (15.4) | 15 (11.8) | 14 (14.1) | 17 (12.9) | ||

| Management and Economics | 9 (8.7) | 17 (13.4) | 8 (8.1) | 18 (13.6) | ||

| Media | 0 | 3 (2.4) | 2 (2) | 1 (0.8) | ||

| General | 9 (8.7) | 7 (5.5) | 8 (8.1) | 8 (6.1) | ||

| Not specified | 4 (3.8) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (2) | 4 (3) | ||

| Socio-Demographics | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Attitude | Knowledge | Attitude | |

| Age | ||||

| <34 | 11.8 ± 3.1 | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 8.8 ± 2.7 | 3.6 ± 0.5 |

| 35–44 | 12.1 ± 3.4 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 10.4 ± 3.1 | 3.3 ± 0.7 |

| 45–54 | 11.5 ± 3.6 | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 11.1 ± 2.6 | 3.2 ± 0.7 |

| 55–62 | 14 ± 5.2 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 9.8 ± 1.9 | 3.1 ± 0.7 |

| p value | 0.7 | 0.007 | 0.29 | 0.7 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 10.9 ± 2.6 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 11.5 ± 3.9 | 3.1 ± 0.6 |

| Married | 12.1 ± 3.5 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 10.7 ± 2.7 | 3.2 ± 0.7 |

| Divorced | 12.4 ± 3.2 | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 8.6 ± 2.9 | 3.8 ± 0.7 |

| Widow | 0 | 10.5 ± 3.6 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | |

| p value | 0.54 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.04 |

| Education level | ||||

| Diploma | 9.9 ± 2.6 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 10.16 ± 3.2 | 3.3 ± 0.7 |

| Bachelor | 12.16 ± 3.3 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 10.4 ± 2.7 | 3.62 ± 0.7 |

| Postgraduate | 13.5 ± 4.6 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 14 ± 1.4 | 3.5 ± 2.1 |

| p value | 0.001 | 0.63 | 0.25 | 0.68 |

| Job title | ||||

| Administrator | 11.6 ± 2.9 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 10.4 ± 2.9 | 3.3 ± 0.7 |

| Teacher | 12.8 ± 4.2 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 11 ± 2.8 | 3 ± 0.6 |

| p value | 0.08 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.01 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hamhoum, A.S.; Aljefree, N.M. Knowledge and Attitudes towards Vitamin D among Health Educators in Public Schools in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2358. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122358

Hamhoum AS, Aljefree NM. Knowledge and Attitudes towards Vitamin D among Health Educators in Public Schools in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2022; 10(12):2358. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122358

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamhoum, Amal S., and Najlaa M. Aljefree. 2022. "Knowledge and Attitudes towards Vitamin D among Health Educators in Public Schools in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 10, no. 12: 2358. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122358

APA StyleHamhoum, A. S., & Aljefree, N. M. (2022). Knowledge and Attitudes towards Vitamin D among Health Educators in Public Schools in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 10(12), 2358. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122358