Improving Long-Term Adherence to Monitoring/Treatment in Underserved Asian Americans with Chronic Hepatitis B (CHB) through a Multicomponent Culturally Tailored Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

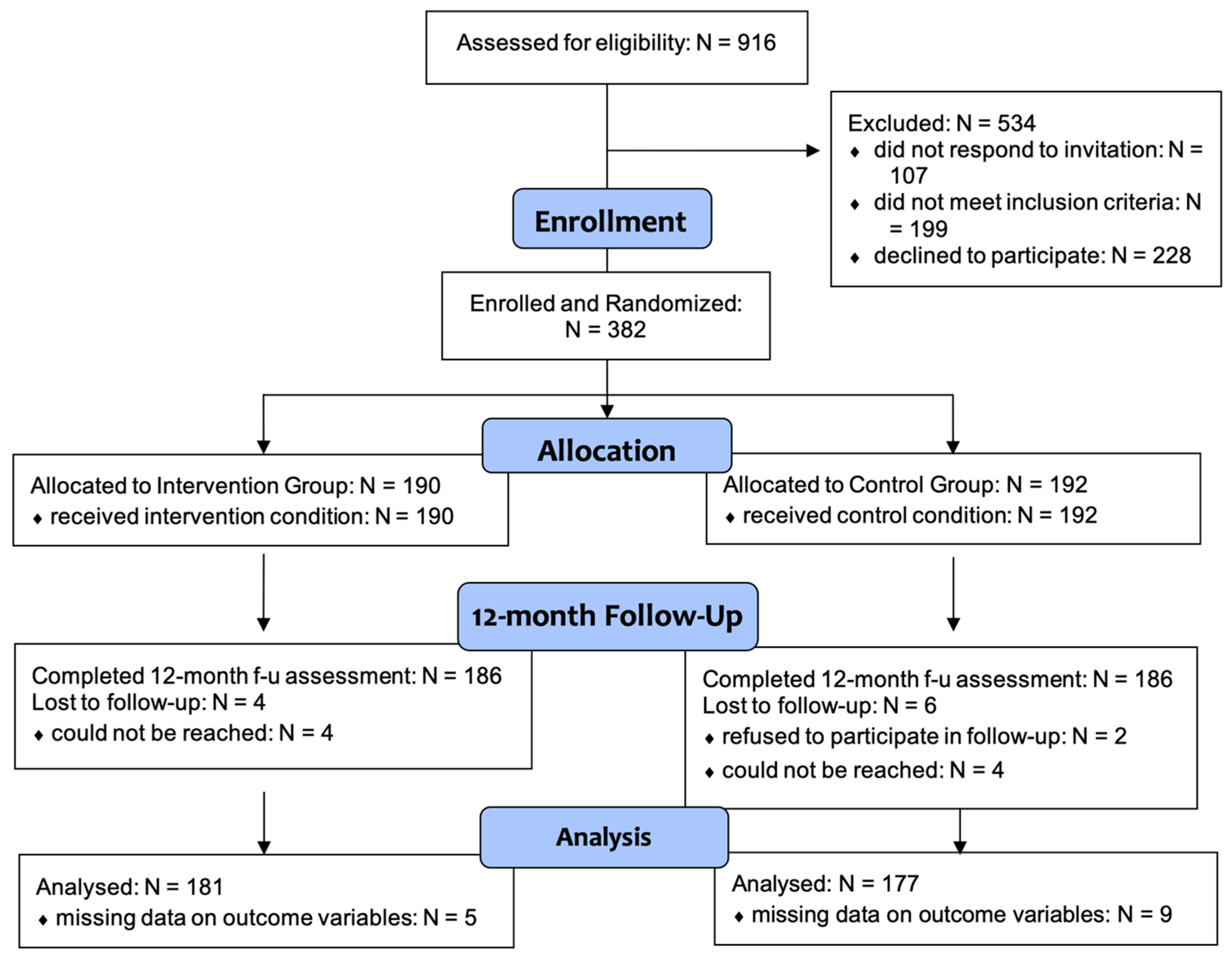

2.1. Participant Recruitment

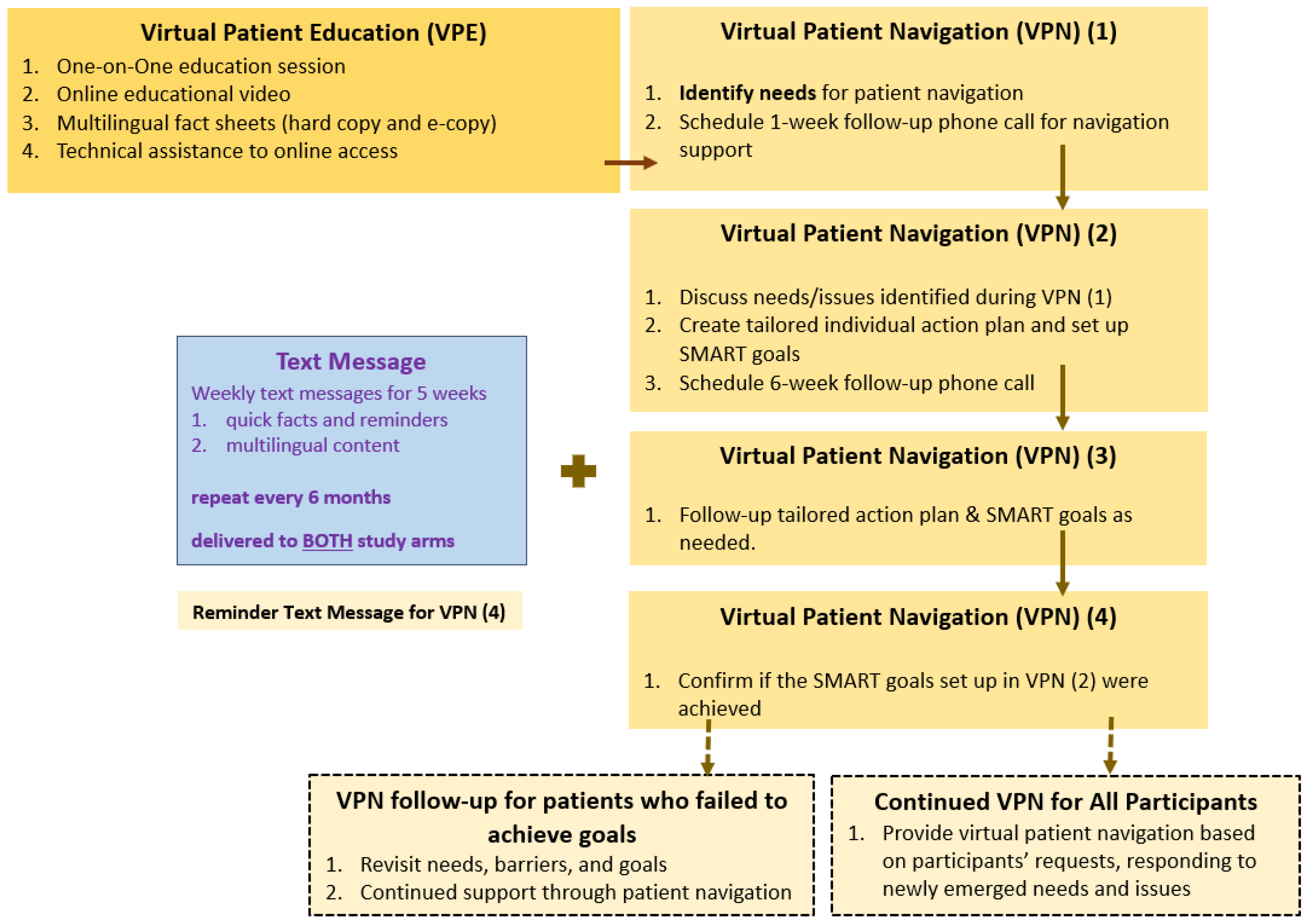

2.2. Intervention Component

2.2.1. Component 1: Virtual Patient Education (VPE)

2.2.2. Component 2: Virtual Patient Navigation (VPN)

2.2.3. Component 3 (Both Study Arms): Mobile Health (mHealth) Text Messages

2.2.4. Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Varbobitis, I.; Papatheodoridis, G.V. The Assessment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B under Antiviral Therapy. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2016, 22, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papatheodoridis, G.V.; Chan, H.L.-Y.; Hansen, B.E.; Janssen, H.L.A.; Lampertico, P. Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B: Assessment and Modification with Current Antiviral Therapy. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 956–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Toy, M.; Demirci, U.; So, S. Preventing Hepatocellular Carcinoma: The Crucial Role of Chronic Hepatitis B Monitoring and Antiviral Treatment. Hepatic Oncol. 2014, 1, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (IOM). Eliminating the Public Health Problem of Hepatitis B and C in the United States: Phase One Report. Available online: https://www.nationalacademies.org:443/hmd/Reports/2016/Eliminating-the-Public-Health-Problem-of-Hepatitis-B-and-C-in-the-US.aspx (accessed on 6 January 2017).

- Terrault, N.A.; Bzowej, N.H.; Chang, K.-M.; Hwang, J.P.; Jonas, M.M.; Murad, M.H. AASLD Guidelines for Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B. Hepatology 2016, 63, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Issues Its First Hepatitis B Treatment Guidelines. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/hepatitis-b-guideline/en/ (accessed on 6 January 2017).

- Post, S.E.; Sodhi, N.K.; Peng, C.; Wan, K.; Pollack, H.J. A Simulation Shows That Early Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B Infection Can Cut Deaths and Be Cost-Effective. Health Aff. 2011, 30, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, C.; Holmberg, S.D.; McMahon, B.J.; Block, J.M.; Brosgart, C.L.; Gish, R.G.; London, W.T.; Block, T.M. Is Chronic Hepatitis B Being Undertreated in the United States? J. Viral Hepat. 2011, 18, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckman, M.H.; Kaiser, T.E.; Sherman, K.E. The Cost-Effectiveness of Screening for Chronic Hepatitis B Infection in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, 1294–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tong, M.J.; Pan, C.Q.; Hann, H.-W.; Kowdley, K.V.; Han, S.-H.B.; Min, A.D.; Leduc, T.-S. The Management of Chronic Hepatitis B in Asian Americans. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2011, 56, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Census Bureau 2020 Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People Born Outside of the United States and Viral Hepatitis|CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/populations/Born-Outside-United-States.htm (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Kim, A.K.; Singal, A.G. Health Disparities in Diagnosis and Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Liver Dis. 2015, 4, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.X. Patient Navigator Intervention for Improving Health-Related Quality of Life in HBV Infected Patients. Unpublished Report. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Ristau, J.T.; Trinh, H.N.; Garcia, R.T.; Nguyen, H.A.; Nguyen, M.H. Undertreatment of Asian Chronic Hepatitis B Patients on the Basis of Standard Guidelines: A Community-Based Study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012, 57, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juday, T.; Tang, H.; Harris, M.; Powers, A.Z.; Kim, E.; Hanna, G.J. Adherence to Chronic Hepatitis B Treatment Guideline Recommendations for Laboratory Monitoring of Patients Who Are Not Receiving Antiviral Treatment. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bastani, R.; Glenn, B.A.; Maxwell, A.E.; Jo, A.M.; Herrmann, A.K.; Crespi, C.M.; Wong, W.K.; Chang, L.C.; Stewart, S.L.; Nguyen, T.T.; et al. Cluster-Randomized Trial to Increase Hepatitis B Testing among Koreans in Los Angeles. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2015, 24, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hu, D.J.; Xing, J.; Tohme, R.A.; Liao, Y.; Pollack, H.; Ward, J.W.; Holmberg, S.D. Hepatitis B Testing and Access to Care Among Racial and Ethnic Minorities in Selected Communities Across the United States, 2009–2010. Hepatology 2013, 58, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.P.; Fisch, M.J.; Zhang, H.; Kallen, M.A.; Routbort, M.J.; Lal, L.S.; Vierling, J.M.; Suarez-Almazor, M.E. Low Rates of Hepatitis B Virus Screening at the Onset of Chemotherapy. J. Oncol. Pract. 2012, 8, e32–e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, G.X.; Zhang, G.Y.; Zhai, S.; Ma, X.; Tan, Y.; Shive, S.E.; Wang, M.Q. Hepatitis B Screening among Chinese Americans: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ma, G.X.; Fang, C.Y.; Seals, B.; Feng, Z.; Tan, Y.; Siu, P.; Yeh, M.C.; Golub, S.A.; Nguyen, M.T.; Tran, T.; et al. A Community-Based Randomized Trial of Hepatitis B Screening Among High-Risk Vietnamese Americans. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.X.; Tan, Y.; Wang, M.Q.; Yuan, Y.; Chae, W.G. Hepatitis B Screening Compliance and Non-Compliance among Chinese, Koreans, Vietnamese and Cambodians. Clin. Med. Insights Gastroenterol. 2010, 2010, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, C.; Lee, S.; Tanaka, M.; Juon, H.-S. Ethnic Differences in Prevalence and Barriers of HBV Screening and Vaccination Among Asian Americans. J. Community Health 2012, 37, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shankar, H.; Blanas, D.; Bichoupan, K.; Ndiaye, D.; Carmody, E.; Martel-Laferriere, V.; Culpepper-Morgan, J.; Dieterich, D.T.; Branch, A.D.; Bekele, M.; et al. A Novel Collaborative Community-Based Hepatitis B Screening and Linkage to Care Program for African Immigrants. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, S289–S297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, W.W.; Lu, P.-J.; O’Halloran, A.; Kim, D.K.; Grohskopf, L.A.; Pilishvili, T.; Skoff, T.; Nelson, N.P.; Harpaz, R.; Markowitz, L.E.; et al. Surveillance of Vaccination Coverage Among Adult Populations—United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2016, 65, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.K.; Ali, S.H.; Ðoàn, L.N.; Yi, S.S.; Trinh-Shevrin, C.; Kwon, S.C. Social Media Use and Misinformation Among Asian Americans During COVID-19. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 764681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.X.; Zhu, L.; Lu, W.; Tan, Y.; Truehart, J.; Johnson, C.; Handorf, E.; Nguyen, M.T.; Yeh, M.-C.; Wang, M.Q. Examining the Influencing Factors of Chronic Hepatitis B Monitoring Behaviors among Asian Americans: Application of the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ispas, S.; So, S.; Toy, M. Barriers to Disease Monitoring and Liver Cancer Surveillance Among Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B in the United States. J. Community Health 2019, 44, 610–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burman, B.E.; Mukhtar, N.A.; Toy, B.C.; Nguyen, T.T.; Chen, A.H.; Yu, A.; Berman, P.; Hammer, H.; Chan, D.; McCulloch, C.E.; et al. Hepatitis B Management in Vulnerable Populations: Gaps in Disease Monitoring and Opportunities for Improved Care. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2014, 59, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, H.; Yim, C.; Chan, A.; Ho, M.; Heathcote, J. Sociocultural Factors That Potentially Affect the Institution of Prevention and Treatment Strategies for Hepatitis B in Chinese Canadians. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 23, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimla, A.; Zhu, L.; Lu, W.; Golub, S.; Enemchukwu, C.; Handorf, E.; Tan, Y.; Yeh, M.-C.; Nguyen, M.T.; Wang, M.Q.; et al. Factors Associated with Hepatitis B Medication Adherence and Persistence among Underserved Chinese and Vietnamese Americans. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Census Bureau. About the Topic of Race. Available online: https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Ma, G.X.; Tan, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, M.Q.; Zhai, S.; Yu, J.; Seals, B.; Siu, P.; Ma, X.; Fang, C.Y.; et al. Testing a Program to Help Monitor Chronic Hepatitis B among Asian-American Patients; Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI): Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, N. Theories for Social Epidemiology in the 21st Century: An Ecosocial Perspective. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 30, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, T.L. Introduction to Chronic Hepatitis B Infection. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2006, 101, S1. [Google Scholar]

- Weinbaum, C.M.; Williams, I.; Mast, E.E.; Wang, S.A.; Finelli, L.; Wasley, A.; Neitzel, S.M.; Ward, J.W. Recommendations for Identification and Public Health Management of Persons with Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2008, 57, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States: A Roadmap to Elimination (2021–2025); U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sorrell, M.F.; Belongia, E.A.; Costa, J.; Gareen, I.F.; Grem, J.L.; Inadomi, J.M.; Kern, E.R.; McHugh, J.A.; Petersen, G.M.; Rein, M.F.; et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Management of Hepatitis B. Hepatology 2009, 49, S4–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R.J.; Khalili, M. A Patient-Centered Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Educational Intervention Improves HBV Care Among Underserved Safety-Net Populations. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2020, 54, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacciarini, J.-M.R.; Shattell, M.M.; Coady, M.; Wiens, B. Review: Community-Based Participatory Research Approach to Address Mental Health in Minority Populations. Community Ment. Health J. 2011, 47, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julian McFarlane, S.; Occa, A.; Peng, W.; Awonuga, O.; Morgan, S.E. Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) to Enhance Participation of Racial/Ethnic Minorities in Clinical Trials: A 10-Year Systematic Review. Health Commun. 2022, 37, 1075–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, G.J.; Fang, T.; Zola, J.; Dariotis, W.M. Destigmatizing Hepatitis B in the Asian American Community: Lessons Learned from the San Francisco Hep B Free Campaign. J. Cancer Educ. 2011, 27, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsu, L.; Bowlus, C.L.; Stewart, S.L.; Nguyen, T.T.; Dang, J.; Chan, B.; Chen, M.S., Jr. Electronic Messages Increase Hepatitis B Screening in At-Risk Asian American Patients: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012, 58, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intervention (N = 181) | Control (N = 177) | Total (N = 358) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Participant Source | 0.14 | |||

| existing cohort | 106 (58.6%) | 117 (66.1%) | 223 (62.3%) | |

| new participants | 75 (41.4%) | 60 (33.9%) | 135 (37.7%) | |

| Age in years | 0.99 | |||

| mean (SD) | 53.18 (12.63) | 53.20 (13.93) | 53.19 (13.27) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.70 | |||

| Chinese | 138 (76.2%) | 138 (78.0%) | 276 (77.1%) | |

| Vietnamese | 43 (23.8%) | 39 (22.0%) | 82 (22.9%) | |

| Gender | 0.66 | |||

| male | 87 (48.1%) | 81 (45.8%) | 168 (46.9%) | |

| female | 94 (51.9%) | 96 (54.2%) | 190 (53.1%) | |

| Marital Status | 0.37 | |||

| currently married | 145 (80.1%) | 145 (83.8%) | 290 (81.9%) | |

| not married | 36 (19.9%) | 28 (16.2%) | 64 (18.1%) | |

| Education | 0.67 | |||

| ≤hs | 123 (68.0%) | 124 (70.1%) | 247 (69.0%) | |

| ≥college | 58 (32.0%) | 53 (29.9%) | 111 (31.0%) | |

| Employment | 0.24 | |||

| employed | 115 (64.2%) | 109 (61.9%) | 224 (63.1%) | |

| unemployed | 9 (5.0%) | 17 (9.7%) | 26 (7.3%) | |

| not in labor force | 55 (30.7%) | 50 (28.4%) | 105 (29.6%) | |

| Annual Household Income | 0.17 | |||

| <USD 20 k | 85 (47.0%) | 96 (54.2%) | 181 (50.6%) | |

| ≥USD 20 k | 96 (53.0%) | 81 (45.8%) | 177 (49.4%) | |

| Nativity Status | 0.17 | |||

| foreign-born | 180 (99.4%) | 173 (97.7%) | 353 (98.6%) | |

| US-born | 1 (0.6%) | 4 (2.3%) | 5 (1.4%) | |

| Length of U.S. Residency | 0.35 | |||

| <10 yrs | 20 (11.5%) | 25 (14.9%) | 45 (13.2%) | |

| ≥10 yrs | 154 (88.5%) | 143 (85.1%) | 297 (86.8%) | |

| Having Health Insurance | 0.04 | |||

| no | 20 (11.0%) | 33 (18.8%) | 53 (14.8%) | |

| yes | 161 (89.0%) | 143 (81.2%) | 304 (85.2%) | |

| Having A Regular Physician | 0.16 | |||

| no | 20 (11.6%) | 27 (17.0%) | 47 (14.2%) | |

| yes | 152 (88.4%) | 132 (83.0%) | 284 (85.8%) | |

| English Proficiency | 0.07 | |||

| not at all/not well | 116 (64.1%) | 129 (72.9%) | 245 (68.4%) | |

| well/very well | 65 (35.9%) | 48 (27.1%) | 113 (31.6%) |

| Variable | Total | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. participants | 358 | 181 | 177 |

| CHB clinic follow-up, % | 86.2% | 54.2% | |

| Model 1, OR (95% CI) | 5.21 (3.11–8.74) | 1 (Ref) | |

| Model 2, OR (95% CI) | 7.35 (4.06–13.33) | 1 (Ref) |

| Variable | Total | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. participants | 358 | 181 | 177 |

| CHB laboratory monitoring, % | 79.0% | 45.2% | |

| Model 1, OR (95% CI) | 4.53 (0.59–7.22) | 1 (Ref) | |

| Model 2, OR (95% CI) | 6.60 (3.77–11.56) | 1 (Ref) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, G.X.; Zhu, L.; Lu, W.; Handorf, E.; Tan, Y.; Yeh, M.-C.; Johnson, C.; Guerrier, G.; Nguyen, M.T. Improving Long-Term Adherence to Monitoring/Treatment in Underserved Asian Americans with Chronic Hepatitis B (CHB) through a Multicomponent Culturally Tailored Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101944

Ma GX, Zhu L, Lu W, Handorf E, Tan Y, Yeh M-C, Johnson C, Guerrier G, Nguyen MT. Improving Long-Term Adherence to Monitoring/Treatment in Underserved Asian Americans with Chronic Hepatitis B (CHB) through a Multicomponent Culturally Tailored Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare. 2022; 10(10):1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101944

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Grace X., Lin Zhu, Wenyue Lu, Elizabeth Handorf, Yin Tan, Ming-Chin Yeh, Cicely Johnson, Guercie Guerrier, and Minhhuyen T. Nguyen. 2022. "Improving Long-Term Adherence to Monitoring/Treatment in Underserved Asian Americans with Chronic Hepatitis B (CHB) through a Multicomponent Culturally Tailored Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial" Healthcare 10, no. 10: 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101944

APA StyleMa, G. X., Zhu, L., Lu, W., Handorf, E., Tan, Y., Yeh, M.-C., Johnson, C., Guerrier, G., & Nguyen, M. T. (2022). Improving Long-Term Adherence to Monitoring/Treatment in Underserved Asian Americans with Chronic Hepatitis B (CHB) through a Multicomponent Culturally Tailored Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare, 10(10), 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101944