Pharmacist Intervention in Portuguese Older Adult Care

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Ageing and the Elderly

3.1. Disease Prevalence and Risk Factors in Older Adults

3.2. Problems Associated with Medication Use in Older Adults

3.3. Social Responses for Older Adults

3.4. Strategies for Active and Healthy Ageing

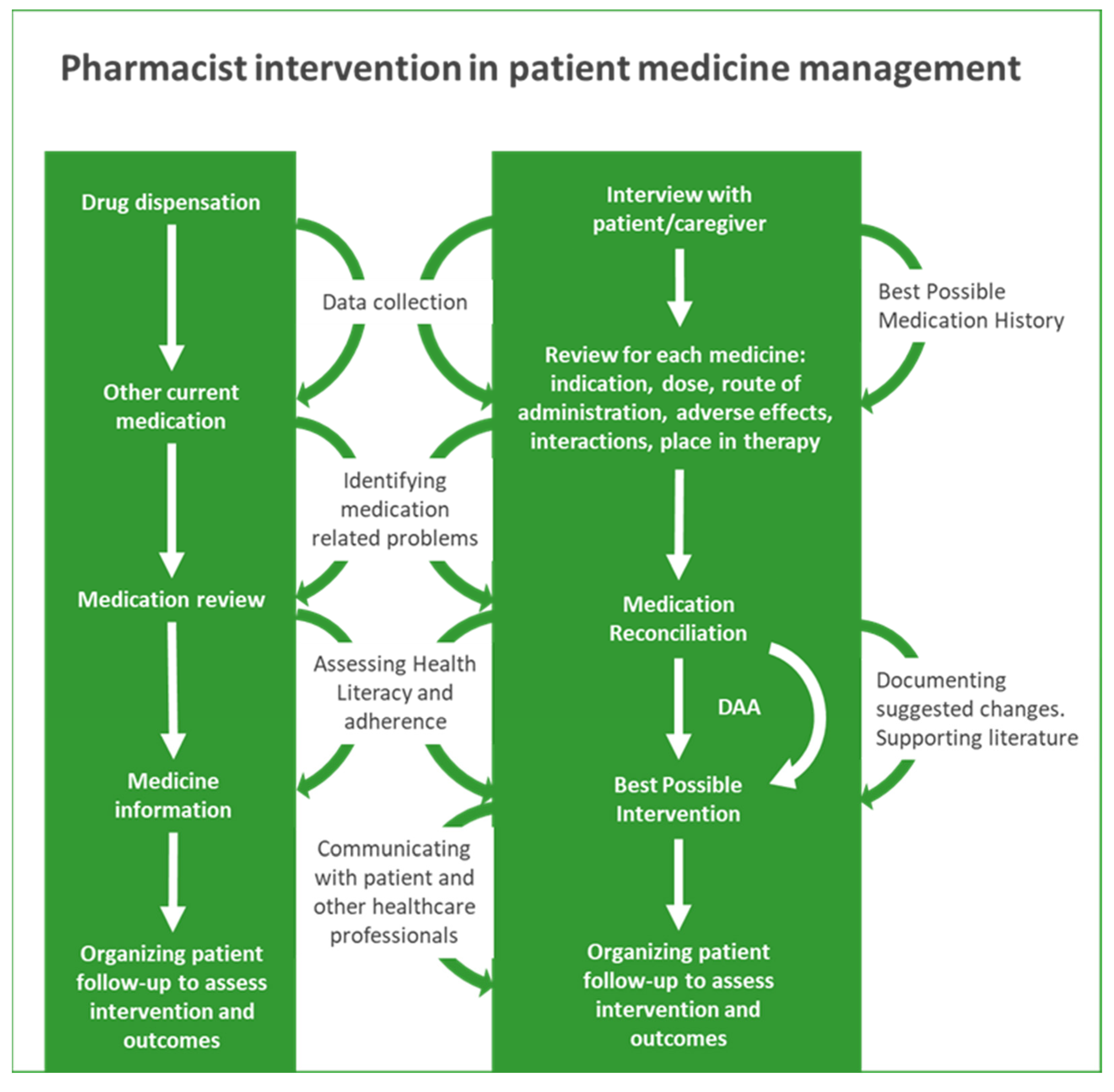

4. The Importance of the Pharmacist in the Follow-Up of Older Adults

4.1. Promoting the Correct, Effective, and Safe Use of Medicines

4.1.1. Drug Dispensation

4.1.2. Medication Review Service (RevM)

4.1.3. Medication Reconciliation Service (RecM)

4.1.4. Dose Administration Aids (DAAs)

5. Emergent Challenges

5.1. Deprescription

5.2. Update for Review and Reconciliation of Medication

5.3. Promotion of Health Literacy in Older Adults and Training for Informal Careers

5.4. Pharmacy Support to Long-Term Care Facilities (LTCF)

5.5. Pharmacy Support for the Older Adults

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Direção-Geral da Saúde. Programa Nacional Para a Saúde Das Pessoas Idosas; Direção-Geral da Saúde: Lisboa, Portugal, 2006.

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; WHO, Ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 9789241565042. [Google Scholar]

- D’ascanio, M.; Innammorato, M.; Pasquariello, L.; Pizzirusso, D.; Guerrieri, G.; Castelli, S.; Pezzuto, A.; De Vitis, C.; Anibaldi, P.; Marcolongo, A.; et al. Age Is Not the Only Risk Factor in COVID-19: The Role of Comorbidities and of Long Staying in Residential Care Homes. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework; World Health Organization, Ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Saúde. Estratégia Nacional Para o Envelhecimento Ativo e Saudável 2017–2025; Ministério da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017.

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística Censos. 2021. Available online: https://censos.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpgid=censos21_main&xpid=CENSOS21&xlang=pt (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- PORDATA. Base de dados Portugal Contemporâneo Indicadores de Envelhecimento Segundo Os Censos. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/Portugal/Indicadores+de+envelhecimento+segundo+os+Censos++-525 (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística Tábuas de Mortalidade Em Portugal Desagregação Regional—2018–2020. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_destaques&DESTAQUESdest_boui=473165032&DESTAQUESmodo=2 (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development OECD Statistics. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeId=9 (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Romana, G.Q.; Kislaya, I.; Gonçalves, S.C.; Salvador, M.R.; Nunes, B.; Dias, C.M. Healthcare Use in Patients with Multimorbidity. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Healthy Life Years at Age 65 by Sex. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tepsr_sp320/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Ellis, G.; Sevdalis, N. Understanding and Improving Multidisciplinary Team Working in Geriatric Medicine. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malet-Larrea, A.; Arbillaga, L.; Gastelurrutia, M.; Larrañaga, B.; Garay, Á.; Benrimoj, S.I.; Oñatibia-Astibia, A.; Goyenechea, E. Defining and Characterising Age-Friendly Community Pharmacies: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 27, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, A.R.; Plácido, A.I.; Curto, I.; Morgado, M.; Herdeiro, M.T.; Roque, F. Acceptance of Pharmaceutical Services by Home-Dwelling Older Patients: A Case Study in a Portuguese Community Pharmacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, L.; Gonzalez-Freire, M.; Fabbri, E.; Simonsick, E.; Tanaka, T.; Moore, Z.; Salimi, S.; Sierra, F.; de Cabo, R. Measuring Biological Aging in Humans: A Quest. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.B.; Yu, X.W.; Yi, X.R.; Wang, C.H.; Tuo, X.P. Epidemiology of Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases and Evaluation of Life Quality in Elderly. Aging Med. 2018, 1, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licher, S.; Darweesh, S.K.L.; Wolters, F.J.; Fani, L.; Heshmatollah, A.; Mutlu, U.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Heeringa, J.; Leening, M.J.G.; Ikram, M.K.; et al. Lifetime Risk of Common Neurological Diseases in the Elderly Population. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2019, 90, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avasthi, A.; Grover, S. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Depression in Elderly. Indian J. Psychiatry 2018, 60, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsamo, M.; Cataldi, F.; Carlucci, L.; Fairfield, B. Assessment of Anxiety in Older Adults: A Review of Self-Report Measures. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Midão, L.; Giardini, A.; Menditto, E.; Kardas, P.; Costa, E. Polypharmacy Prevalence among Older Adults Based on the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 78, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozkok, S.; Aydin, C.O.; Sacar, D.E.; Catikkas, N.M.; Erdogan, T.; Kilic, C.; Karan, M.A.; Bahat, G. Associations between Polypharmacy and Physical Performance Measures in Older Adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 98, 104553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falch, C.; Alves, G. Pharmacists’ Role in Older Adults’ Medication Regimen Complexity: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallio, S.E.; Kiiski, A.; Airaksinen, M.S.A.; Mäntylä, A.T.; Kumpusalo-Vauhkonen, A.E.J.; Järvensivu, T.P.; Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, M.K. Community Pharmacists’ Contribution to Medication Reviews for Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaam, M.; Naseralallah, L.M.; Hussain, T.A.; Pawluk, S.A. Pharmacist-Led Educational Interventions Provided to Healthcare Providers to Reduce Medication Errors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskaleva, D.; Tufkova, S. Social and Medical Problems of the Elderly. J. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2017, 6, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-de Araújo, J.R.; Tomaz-de Lima, R.R.; Ferreira-Bendassolli, I.M.; Costa-de Lima, K. Functional, Nutritional and Social Factors Associated with Mobility Limitations in the Elderly: A Systematic Review. Salud Publica Mex. 2018, 60, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.E.; Chatterji, S.; Kowal, P.; Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; McKee, M.; Rechel, B.; Rosenberg, L.; Smith, J.P. Macroeconomic Implications of Population Ageing and Selected Policy Responses. Lancet 2015, 385, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, J.A.; Ramos, G.C.F.; Barbosa, A.T.F.; Medeiros, S.M.; De Almeida Lima, C.; Da Costa, F.M.; Caldeira, A.P. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Polypharmacy in Community Elderly: Population Based Epidemiological Study. Medicina 2018, 51, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bories, M.; Bouzillé, G.; Cuggia, M.; Corre, P. Le Drug–Drug Interactions in Elderly Patients with Potentially Inappropriate Medications in Primary Care, Nursing Home and Hospital Settings: A Systematic Review and a Preliminary Study. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, L.E.; Spiers, G.; Kingston, A.; Todd, A.; Adamson, J.; Hanratty, B. Adverse Outcomes of Polypharmacy in Older People: Systematic Review of Reviews. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, L.; Larkin, J.; Lombard-Vance, R.; Murphy, A.W.; Hynes, L.; Galvin, E.; Molloy, G.J. Prevalence and Predictors of Medication Non-Adherence among People Living with Multimorbidity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Promoting Rational Use of Medicines. Available online: https://www.who.int/activities/promoting-rational-use-of-medicines (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- World Health Organization. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies. Evidence for Action; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gast, A.; Mathes, T. Medication Adherence Influencing Factors—An (Updated) Overview of Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaje, A.; Weston-Clark, M.; Raj, R.; Orlu, M.; Davis, D.; Rawle, M. Factors Associated with Medication Adherence in Older Patients: A Systematic Review. Aging Med. 2018, 1, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, R.; Watanabe, F.; Kamei, M. Factors Associated with Medication Non-Adherence among Patients with Lifestyle-Related Non-Communicable Diseases. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kini, V.; Michael Ho, P. Interventions to Improve Medication Adherence: A Review. JAMA 2018, 320, 2461–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Félix, J.; Ferreira, D.; Afonso-Silva, M.; Gomes, M.V.; Ferreira, C.; Vandewalle, B.; Marques, S.; Mota, M.; Costa, S.; Cary, M.; et al. Social and Economic Value of Portuguese Community Pharmacies in Health Care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, D.; Placido, A.I.; Mó, R.; Simões, J.L.; Amaral, O.; Fernandes, I.; Lima, F.; Morgado, M.; Figueiras, A.; Herdeiro, M.T.; et al. Daily Medication Management and Adherence in the Polymedicated Elderly: A Cross-Sectional Study in Portugal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bou Malham, C.; El Khatib, S.; Cestac, P.; Andrieu, S.; Rouch, L.; Salameh, P. Impact of Pharmacist-Led Interventions on Patient Care in Ambulatory Care Settings: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social. Decreto-Lei n.o 64/2007; Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social: Lisbon, Portugal, 2007.

- Farias, I.P.S.; Montenegro, L.A.S.; Wanderley, R.L.; de Pontes, J.C.X.; Pereira, A.C.; Almeida, L.F.D.; Cavalcanti, Y.W. Physical, Nutritional and Psychological States Interfere with Health Related Quality of Life of Institutionalized Elderly. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Solidariedade e da Segurança Social. Portaria n.o 67/2012 de 21 de Março. Diário Da Repúb. 2012, 58, 1324–1329. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research Active and Healthy Ageing (AHA). Available online: https://www.euro.centre.org/domains/active-and-healthy-ageing (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Bell, V.; Pita, J.R. A Importância Do Farmacêutico Na Gestão Dos Medicamentos Nas Estruturas Residenciais Para Pessoas Idosas Em Portugal. Infarma 2021, 33, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwadiugwu, M.C. Multi-Morbidity in the Older Person: An Examination of Polypharmacy and Socioeconomic Status. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 582234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Decade of Healthy Ageing Functional Baseline Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kayyali, R.; Funnell, G.; Harrap, N.; Patel, A. Can Community Pharmacy Successfully Bridge the Gap in Care for Housebound Patients? Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivan, N.F.M.; Singh, D.K.A.; Shahar, S.; Wen, G.J.; Rajab, N.F.; Din, N.C.; Mahadzir, H.; Kamaruddin, M.Z.A. Cognitive Frailty Is a Robust Predictor of Falls, Injuries, and Disability among Community-Dwelling Older Adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campani, D.; Caristia, S.; Amariglio, A.; Piscone, S.; Ferrara, L.I.; Barisone, M.; Bortoluzzi, S.; Faggiano, F.; Dal Molin, A.; Silvia Zanetti, E.; et al. Home and Environmental Hazards Modification for Fall Prevention among the Elderly. Public Health Nurs. 2021, 38, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osibona, O.; Solomon, B.D.; Fecht, D. Lighting in the Home and Health: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. Understanding How Older Adults Negotiate Environmental Hazards in Their Home. J. Aging Environ. 2022, 36, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupanagudi, U.F. Flooring: A Risk Factor for Fall-Related Injuries in Elderly People Housing. In Techno-Societal; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 797–804. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, T.; Martins, L. Environmental Determinants of Home Accident Risk Among the Elderly. a Systematic Review. In Occupational and Environmental Safety and Health III; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 571–578. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, G.M.; Kale, H.L. Fall Prevention in Central Coast Community Pharmacies. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2018, 29, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmeke, M.; Koster, E.S.; Janatgol, O.; Taxis, K.; Bouvy, M.L. Pharmacy Fall Prevention Services for the Community-Dwelling Elderly: Patient Engagement and Expectations. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 1450–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh-Park, M.; Doan, T.; Dohle, C.; Vermiglio-Kohn, V.; Abdou, A. Technology Utilization in Fall Prevention. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 100, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regional Committee for Europe. Strategy and Action Plan for Healthy Ageing in Europe, 2012–2020; WHO: Valeta, Malta, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Mental Health of Older Adults. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Galenkamp, H.; Gagliardi, C.; Principi, A.; Golinowska, S.; Moreira, A.; Schmidt, A.E.; Winkelmann, J.; Sowa, A.; van der Pas, S.; Deeg, D.J.H. Predictors of Social Leisure Activities in Older Europeans with and without Multimorbidity. Eur. J. Ageing 2016, 13, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero Jiménez, B.; Conde-Caballero, D.; Juárez, L.M. Loneliness among the Elderly in Rural Contexts: A Mixed-Method Study Protocol. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2021, 20, 1609406921996861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XXII Governo Constitucional. Programa Do XXII Governo Constotucional 2019–2023. 2019. Available online: https://www.portugal.gov.pt/download-ficheiros/ficheiro.aspx?v=%3d%3dBAAAAB%2bLCAAAAAAABACzsDA1AQB5jSa9BAAAAA%3d%3d (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- European Commission RePEnSA—Portuguese Network for Health and Active Ageing|Futurium. Available online: https://futurium.ec.europa.eu/en/active-and-healthy-living-digital-world/ecosystems-and-deployment/best-practices/repensa-portuguese-network-health-and-active-ageing (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Leguelinel-Blache, G.; Castelli, C.; Rolain, J.; Bouvet, S.; Chkair, S.; Kabani, S.; Jalabert, B.; Rouvière, S.; Choukroun, C.; Richard, H.; et al. Impact of Pharmacist-Led Multidisciplinary Medication Review on the Safety and Medication Cost of the Elderly People Living in a Nursing Home: A before-after Study. Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2020, 20, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Algharably, E.A.E.; Budnick, A.; Wenzel, A.; Dräger, D.; Kreutz, R. High Prevalence of Multimorbidity and Polypharmacy in Elderly Patients With Chronic Pain Receiving Home Care Are Associated With Multiple Medication-Related Problems. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 686990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, M.; Akdeniz, M.; Kavukcu, E. Assessment of Comorbidity and Use of Prescription and Nonprescription Drugs in Patients Above 65 Years Attending Family Medicine Outpatient Clinics. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2019, 5, 2333721419874274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policarpo, V.; Romano, S.; António, J.H.C.; Correia, T.S.; Costa, S. A New Model for Pharmacies? Insights from a Quantitative Study Regarding the Public’s Perceptions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawan, M.; Reeve, E.; Turner, J.; Todd, A.; Steinman, M.A.; Petrovic, M.; Gnjidic, D. A Systems Approach to Identifying the Challenges of Implementing Deprescribing in Older Adults across Different Health-Care Settings and Countries: A Narrative Review. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 13, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde. Decreto-Lei No 307/2007, de 31 de Agosto—Regime Jurídico Das Farmácias de Oficina; Diário da República, 1.a série; Ministério da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2007; pp. 6083–6091.

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria No 1429/2007, de 2 de Novembro; Diário da República, 1.a série; Ministério da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2007; Volume 211, p. 7993.

- Ministério da Saúde. Plano Nacional de Saúde: Orientações Estratégicas Para 2004–2010; Ministério da Saúde: Lisboa, Portugal, 2004.

- Direção-Geral da Saúde. Plano Nacional de Saúde: Revisão e Extensão a 2020; Direção-Geral da Saúde: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015.

- Newman, T.V.; San-Juan-Rodriguez, A.; Parekh, N.; Swart, E.C.S.; Klein-Fedyshin, M.; Shrank, W.H.; Hernandez, I. Impact of Community Pharmacist-Led Interventions in Chronic Disease Management on Clinical, Utilization, and Economic Outcomes: An Umbrella Review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Launches Global Effort to Halve Medication-Related Errors in 5 Years. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-03-2017-who-launches-global-effort-to-halve-medication-related-errors-in-5-years (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Pan American Health Organization Rational Use of Medicines and Other Health Technologies—PAHO/WHO|Pan American Health Organization. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/topics/rational-use-medicines-and-other-health-technologies (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Indian Pharmaceutical Association. Responsible Use of Medicines Campaign for Awareness on Responsible Use of Medicines; WHO: Mumbai, India.

- De Almeida Simoes, J.; Augusto, G.F.; Fronteira, I.; Hernández-Quevedo, C. Portugal: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2017, 19, 1–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care What We’re Doing about Medicines. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/medicines/what-we-do?utm_source=health.gov.au&utm_medium=callout-auto-custom&utm_campaign=digital_transformation (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Juanes, A.; Garin, N.; Mangues, M.A.; Herrera, S.; Puig, M.; Faus, M.J.; Baena, M.I. Impact of a Pharmaceutical Care Programme for Patients with Chronic Disease Initiated at the Emergency Department on Drug-Related Negative Outcomes: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2018, 25, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestres, C.; Hernandez, M.; Agustí, A.; Puerta, L.; Llagostera, B.; Amorós, P. Development of a Pharmaceutical Care Program in Progressive Stages in Geriatric Institutions. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavaco, A.M.; Grilo, A.; Barros, L. Exploring Pharmacists’ Orientation towards Patients in Portuguese Community Pharmacies. J. Commun. Healthc. 2020, 13, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde. Plano Nacional Para a Segurança Dos Doentes 2015–2020; Ministério da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2015.

- Ministério da Saúde. Plano Nacional Para a Segurança Dos Doentes 2021–2026; Ministério da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021.

- Lewicki, J.; Religioni, U.; Merks, P. Evaluation of the Community Pharmacy Comorbidities Screening Service on Patients with Chronic Diseases. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2021, 15, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moczygemba, L.R.; Alshehri, A.M.; David Harlow, L., III; Lawson, K.A.; Antoon, D.A.; McDaniel, S.M.; Matzke, G.R. Comprehensive Health Management Pharmacist-Delivered Model: Impact on Healthcare Utilization and Costs. Am. J. Manag. Care 2019, 25, 554–560. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Robles, A.; Benrimoj, S.I.; Gastelurrutia, M.A.; Martinez-Martinez, F.; Peiro, T.; Perez-Escamilla, B.; Rogers, K.; Valverde-Merino, I.; Varas-Doval, R.; Garcia-Cardenas, V. Effectiveness of a Medication Adherence Management Intervention in a Community Pharmacy Setting: A Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2022, 31, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griese-Mammen, N.; Hersberger, K.E.; Messerli, M.; Leikola, S.; Horvat, N.; van Mil, J.W.F.; Kos, M. PCNE Definition of Medication Review: Reaching Agreement. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2018, 40, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuscart, J.B.; Pelayo, S.; Robert, L.; Thevelin, S.; Marien, S.; Dalleur, O. Medication Review and Reconciliation in Older Adults. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imfeld-Isenegger, T.L.; Soares, I.B.; Makovec, U.N.; Horvat, N.; Kos, M.; van Mil, F.; Costa, F.A.; Hersberger, K.E. Community Pharmacist-Led Medication Review Procedures across Europe: Characterization, Implementation and Remuneration. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS. Structured Medication Reviews and Medicines Optimisation: Guidance; NHS: London, UK, 2020.

- Khalil, H.; Bell, B.; Chambers, H.; Sheikh, A.; Avery, A.J. Professional, Structural and Organisational Interventions in Primary Care for Reducing Medication Errors. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 10, CD003942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scott, I.A.; Gray, L.C.; Martin, J.H.; Pillans, P.I.; Mitchell, C.A. Deciding When to Stop: Towards Evidence-Based Deprescribing of Drugs in Older Populations. Evid. Based Med. 2013, 18, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Monzón-Kenneke, M.; Chiang, P.; Yao, N.; Greg, M. Pharmacist Medication Review: An Integrated Team Approach to Serve Home-Based Primary Care Patients. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Salahudeen, M.S.; Bereznicki, L.R.E.; Curtain, C.M. Pharmacist-Led Interventions to Reduce Adverse Drug Events in Older People Living in Residential Aged Care Facilities: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 3672–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care Home Medicines Review. Available online: https://www.ppaonline.com.au/programs/medication-management-programs/home-medicines-review (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Canada Ministry of Health MedsCheck. Available online: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/medscheck/medscheck_original.aspx (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Stewart, D.; Madden, M.; Davies, P.; Whittlesea, C.; McCambridge, J. Structured Medication Reviews: Origins, Implementation, Evidence, and Prospects. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2021, 71, 340–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society Pharmacist Independent Prescribing. Available online: https://www.rpharms.com/recognition/all-our-campaigns/pharmacist-prescribing (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Tonin, F.S.; Aznar-Lou, I.; Pontinha, V.M.; Pontarolo, R.; Fernandez-Llimos, F. Principles of Pharmacoeconomic Analysis: The Case of Pharmacist-Led Interventions. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 19, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Mota-Filipe, H.; Guerreiro, M.P.; da Costa, F.A. Primary Health Care Policy and Vision for Community Pharmacy and Pharmacists in Portugal. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 18, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direção-Geral da Saúde. Norma No 018/2016 de 30/12/2016 2/7; Direção-Geral da Saúde: Lisboa, Portugal, 2016.

- Lourenço, A.F. Inovação Em Saúde: Primeiro Contributo Para o Desenvolvimento de Um Novo Modelo de Prática Do Farmacêutico Clínico Nos Cuidados de Saúde Primários. Coimbra. 2018. Available online: https://estudogeral.sib.uc.pt/bitstream/10316/84625/1/Disserta%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20Final_corrigida_AFL.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Choi, Y.J.; Kim, H. Effect of Pharmacy-Led Medication Reconciliation in Emergency Departments: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2019, 44, 932–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Pharmaceutical Federation. Medicines Reconciliation: A Toolkit for Pharmacists; International Pharmaceutical Federation: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ordem dos Farmacêuticos. ROF 106. 2013. Available online: https://www.ordemfarmaceuticos.pt/fotos/publicacoes/bc.106_reconciliacao_da_medicacao_um_conceito_aplicado_ao_hospital_consulta_farmaceutica_de_revisao_de_medicacao_9863584205a12ec698cec5.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Renata, A. Reconciliação de Terapêutica. Rev. Clin. Hosp. Prof. Dr. Fernando Fonseca 2015, 3, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Grupo de Trabalho para a dispensa de proximidade Relatório Projeto de Proximidade. 2020. Available online: https://www.infarmed.pt/documents/15786/2304493/Projeto+de+proximidade+-+Relat%C3%B3rio/d478b639-2c72-45f6-ef65-bc881eea06aa (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Oliveira, J.; Silva, T.C.E.; Cabral, A.C.; Lavrador, M.; Almeida, F.F.; Macedo, A.; Saraiva, C.; Fernandez-Llimos, F.; Caramona, M.M.; Figueiredo, I.V.; et al. Pharmacist-Led Medication Reconciliation on Admission to an Acute Psychiatric Hospital Unit. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 20, 2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.; Dias, P.; Alves, C.; Feio, J.; Lavrador, M.; Oliveira, J.; Figueiredo, I.V.; Rocha, M.J.; Castel-Branco, M. Medication Reconciliation During Admission to an Internal Medicine Department: A Pilot Study. Acta Med. Port. 2022, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmacy Programs Admnistrator Pharmacy Programs Admnistrator—DAA. Available online: https://www.ppaonline.com.au/programs/medication-adherence-programs-2/dose-administration-aids (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Hersberger, K.E.; Boeni, F.; Arnet, I. Dose-Dispensing Service as an Intervention to Improve Adherence to Polymedication. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 6, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, E.; Twining, L.; Walters, L. Understanding the Decision to Commence a Dose Administration Aid Background and Objectives. Aust. Fam. Physician 2017, 46, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haywood, A.; Llewelyn, V.; Robertson, S.; Mylrea, M.; Glass, B. Dose Administration Aids: Pharmacists’ Role in Improving Patient Care. Australas. Med. J. 2011, 4, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, A.; Mónico, B.; Lourenço, M.; Lourenço, O. Dose Administration Aid Service in Community Pharmacies: Characterization and Impact Assessment. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria n.o 455-A/2010, de 30 de Junho; Diário da República: Lisbon, Portugal, 2010.

- Ordem dos Farmacêuticos. Norma Geral Preparação Individualizada Da Medicação; OF: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete, J.; Yuksel, N.; Schindel, T.J.; Hughes, C.A. Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Provided by Community Pharmacists: A Scoping Review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhec, M. Clinical Pharmacist Consultant in Primary Care Settings in Slovenia Focused on Elderly Patients on Polypharmacy: Successful National Program from Development to Reimbursement. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 43, 1722–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoel, R.W.; Giddings Connolly, R.M.; Takahashi, P.Y. Polypharmacy Management in Older Patients. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnaswami, A.; Steinman, M.A.; Goyal, P.; Zullo, A.R.; Anderson, T.S.; Birtcher, K.K.; Goodlin, S.J.; Maurer, M.S.; Alexander, K.P.; Rich, M.W.; et al. Deprescribing in Older Adults With Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2584–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.A.; Carnovale, C.; Gabiati, C.; Montori, D.; Brucato, A. Appropriateness of Care: From Medication Reconciliation to Deprescribing. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2021, 16, 2047–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordem dos Farmacêuticos Orientações Para a Revisão Da Medicação. 2021. Available online: https://www.ordemfarmaceuticos.pt/fotos/editor2/2021/Documentos/orm_of.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- International Pharmaceutical Federation. Medication Review and Medicines Use Review A Toolkit for Pharmacists; International Pharmaceutical Federation: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). FIP Emphasises Pharmacists’ Wider Medication Review Roles in Update of Its Medicines Use Review Toolkit. Available online: https://www.fip.org/news?news=newsitem&newsitem=423 (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Costa, S.; Horta, M.R.; Santos, R.; Mendes, Z.; Jacinto, I.; Guerreiro, J.; Cary, M.; Miranda, A.; Helling, D.K.; Martins, A.P. Diabetes Policies and Pharmacy-Based Diabetes Interventions in Portugal: A Comprehensive Review. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2019, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Jiang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Ju, X.; Zhang, X. What Is the Meaning of Health Literacy? A Systematic Review and Qualitative Synthesis. Fam. Med. Community Health 2020, 8, e000351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugesu, L.; Heijmans, M.; Rademakers, J.; Fransen, M.P. Challenges and Solutions in Communication with Patients with Low Health Literacy: Perspectives of Healthcare Providers. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; An, W.; Zheng, C.; Zhao, D.; Wang, H. Multidimensional Health Literacy Profiles and Health-Related Behaviors in the Elderly: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2022, 9, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilton, T.; Barry, M.M. The Critical Role of Health Promotion for Effective Universal Health Coverage. Glob. Health Promot. 2021, 29, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.; Kirubakaran, R.; Isaac, R.; Dozier, M.; Grant, L.; Weller, D. RESPIRE collaboration Theory of Planned Behaviour-Based Interventions in Chronic Diseases among Low Health-Literacy Population: Protocol for a Systematic Review. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, J.; Rondia, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Kohn, L. Health Literacy: What Lessons Can Be Learned from the Experiences and Policies of Different Countries? Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2022, 37, 886–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde. Despacho n.o 3618-A/2016; Diário da Republica 2.a série; Ministério da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2016; Volume 8660-(5).

- Telo-de-Arriaga, M.; Santos, B.; Silva, A.; Mta, F.; Chaves, N.F.G. Plano de Ação Para a Literacia Em Saúde; DGS: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- De Almeida, C.V.; da Silva, C.R.; Rosado, D.; Miranda, D.; Oliveira, D.; Mata, F.; Maltez, H.; Luis, H.; Filipe, J.; Moutão, J.; et al. Manual De Boas Práticas Literacia Em Saúde; DGS: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019; ISBN 9789726752882. [Google Scholar]

- Ordem dos Farmacêuticos Regulamento n.o 1015/2021 [Código Deontológico Da Ordem Dos Farmacêuticos] de 20 de Dezembro de 2021; Diário da República: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021; Volume 244, pp. 143–159.

- De Wit, L.; Fenenga, C.; Giammarchi, C.; Di Furia, L.; Hutter, I.; De Winter, A.; Meijering, L. Community-Based Initiatives Improving Critical Health Literacy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Evidence. BMC Public Health 2017, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assembleia da República Lei n.o100/2019, de 6 de Setembro; Diário da Republica: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019; Volume 171, pp. 3–16.

- GEP-Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento Rede de Serviços e Equipamentos. Available online: http://www.cartasocial.pt/index2.php (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Kosari, S.; McDerby, N.; Thomas, J.; Naunton, M. Quality Use of Medicines in Aged Care Facilities: A Need for New Models of Care. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2018, 43, 591–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diário da República Despacho Normativo n.o 12/98, de 25 de Fevereiro. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/despacho-normativo/12-1998-211235 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Delgado-Silveira, E.; Bermejo-Vicedo, T. The Role of Pharmacists in Geriatric Teams: The Time Is Now. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 1119–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comissão Setorial para a Saúde do Sistema Português da Qualidade Recomendação Da Comissão Setorial Para a Saúde Do Sistema Português Da Qualidade Para a Gestão Da Medicaçãonas Estruturas Residenciais Para Pessoas Idosas (ERPI). 2014. Available online: http://www1.ipq.pt/PT/SPQ/ComissoesSectoriais/CS09/Documents/Recomendacao_paraGT_ERPI.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Koprivnik, S.; Albiñana-Pérez, M.S.; López-Sandomingo, L.; Taboada-López, R.J.; Rodríguez-Penín, I. Improving Patient Safety through a Pharmacist-Led Medication Reconciliation Programme in Nursing Homes for the Elderly in Spain. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 42, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segurança Social Manual Dos Processos-Chave Estrutura Residencial Para Idosos. Available online: https://www.seg-social.pt/documents/10152/13652/gqrs_lar_estrutura_residencial_idosos_Processos-Chave/1378f584-8070-42cc-ab8d-9fc9ec9095e4 (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Ministério da Saúde. Decreto-Lei n.o176/2006 de 30 de Agosto; Ministério da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2006.

- Litsey, J. Evolution of Consulting Pharmacy and Medication Management. Top. Geriatr. Med. Med. Dir. 2015, 37, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, N. Consultant Pharmacist’’-What Does It Mean? Hosp. Pharm.-Lond. 2008, 15, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Malson, G. The Role of the Consultant Pharmacist in the NHS. Pharm. J. 2015, 295, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.; Mortimore, G. Prescriber. August 2018. Available online: https://wchh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/psb.1695 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Disalvo, D.; Luckett, T.; Bennett, A.; Davidson, P.; Agar, M. Pharmacists’ Perspectives on Medication Reviews for Long-Term Care Residents with Advanced Dementia: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2019, 41, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, D.; Beaton, C.; Liang, J.; Basu, K.; Hum, M.; Propp, A.; Yanni, L.; Chen, Y.; Ghafari, P. Cost Impact of a Pharmacist-Driven Medication Reconciliation Program during Transitions to Long-Term Care and Retirement Homes. Healthc. Q. 2020, 23, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PORDATA. Base de dados Portugal Contemporâneo Agregados Domésticos Privados Unipessoais: Total e de Indivíduos Com 65 e Mais Anos. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/DB/Portugal/Ambiente+de+Consulta/Tabela (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Berg-Weger, M.; Morley, J.E. Loneliness in Old Age: An Unaddressed Health Problem. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria No 1427/2007, de 2 de Novembro; Diário da República, 1.a série; Ministério da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2007; Volume 211, pp. 7991–7992.

- PORDATA. Base de dados Portugal Contemporâneo Farmácias: Número. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/Portugal/Farmácias+número-153 (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Infarmed–Autoridade Nacional do Medicamento e Produtos de Saúde, I.P. Listagem de Farmácias. Available online: https://extranet.infarmed.pt/LicenciamentoMais-fo/pages/public/listaFarmacias.xhtml (accessed on 13 July 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, A.R.; Teixeira-Lemos, E.; Mascarenhas-Melo, F.; Lemos, L.P.; Bell, V. Pharmacist Intervention in Portuguese Older Adult Care. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1833. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101833

Rodrigues AR, Teixeira-Lemos E, Mascarenhas-Melo F, Lemos LP, Bell V. Pharmacist Intervention in Portuguese Older Adult Care. Healthcare. 2022; 10(10):1833. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101833

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Ana Rita, Edite Teixeira-Lemos, Filipa Mascarenhas-Melo, Luís Pedro Lemos, and Victoria Bell. 2022. "Pharmacist Intervention in Portuguese Older Adult Care" Healthcare 10, no. 10: 1833. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101833

APA StyleRodrigues, A. R., Teixeira-Lemos, E., Mascarenhas-Melo, F., Lemos, L. P., & Bell, V. (2022). Pharmacist Intervention in Portuguese Older Adult Care. Healthcare, 10(10), 1833. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101833