Vulnerability through the Eyes of People Attended by a Portuguese Community-Based Association: A Thematic Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Research Problem

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting, Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Study Rigour

2.6. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

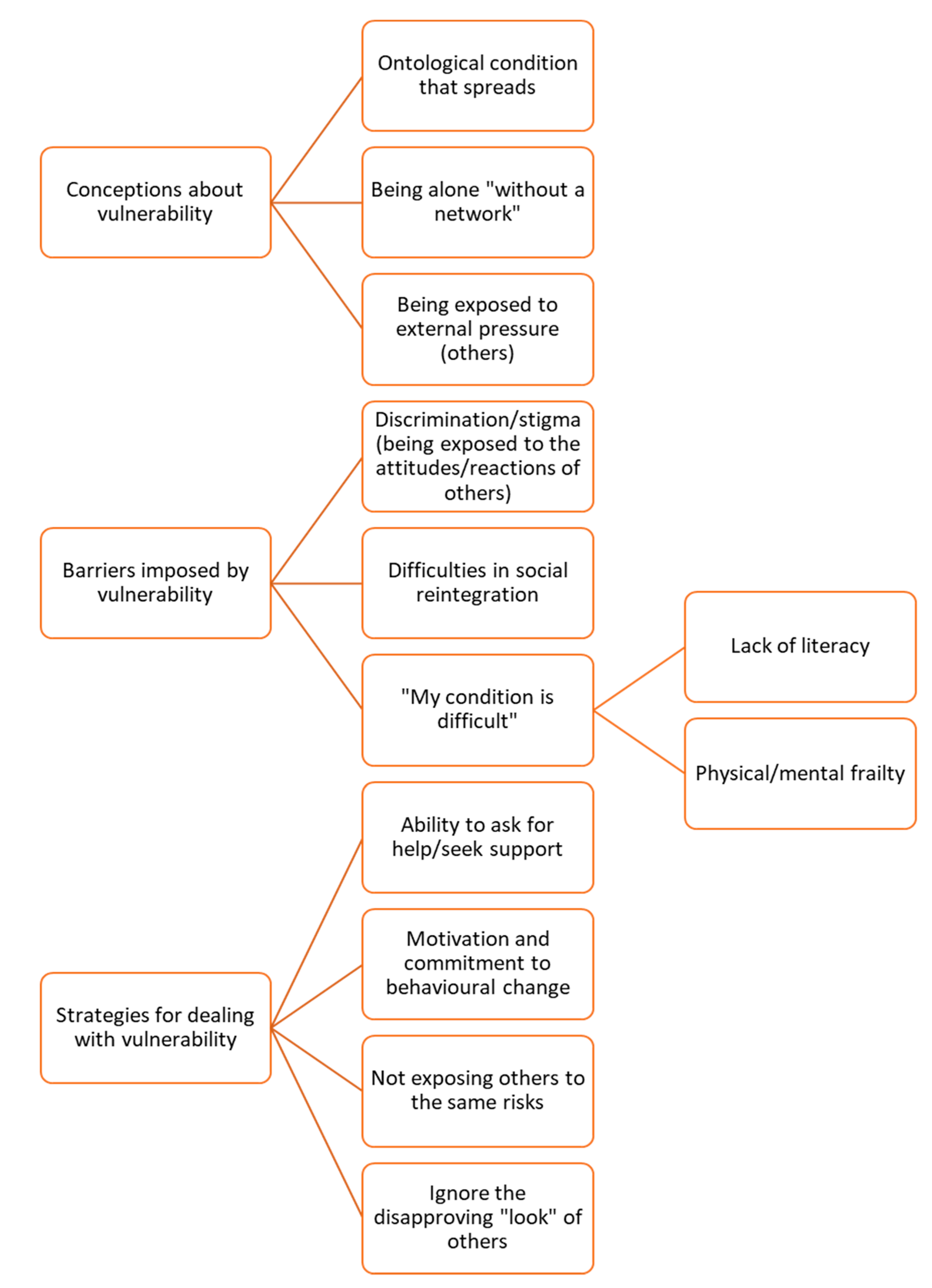

3.2. Qualitative Findings

3.2.1. Conceptions about Vulnerability

P1: “It’s part of a period of life that I lived, when I was living on the street, that’s when I felt this effect the most (…) Yes, it’s a snowball, and it affects our whole life (…) I lived on the street because the money I received from the unemployment fund was not enough to pay for a room and now due to drug consumption I continue to live on the street and spend all my money on drugs”.

P10: “During my childhood my father beat me because yes… so I felt vulnerable, because I couldn’t do anything, I thought why was he doing that to me, why? And he felt vulnerable because he couldn’t do anything. Now he still feels vulnerable because I can’t stop consuming”.

P5: “The truth is that I need a friend to be able to talk, so I don’t get to this point of keeping everything, and then when it explodes it’s like this (…), after my father died, after 6 months my brother left home and my mother worked at night (…) I was always alone, so I’ve been used to being alone for a long time (…) It’s been very difficult, I don’t know what to do with my life, what I can do myself…”

P7: “I have no support from anyone, not even the family (…) anyone! I only have the support of my son, nothing else, I stopped talking to them, because I am of a nature that they do not admit. I did so much for them, but they don’t recognize…”

P9: “I prefer to be alone in my corner, because I have no one to help me”

P10: “Alone (…) I don’t have anyone, my father died, my wife died, I mean I don’t have anyone else”

P4: “Yes, it’s not just for me, it’s because of my environment, I think people are like that, a little weak and they always go after each other; and it is easy, for example, to find someone who has never smoked anything; and they say then don’t you want to try it? Or they see me smoking and ask to try it. If they didn’t call me I wouldn’t go. I never have money, but when I do, I think straight away, of course I do (…) Dealers call me every day, write “there are big scenes in the neighbourhood, you get 50€ for two”, “you take 50€ and you get a bonus”, scenes like that …”

3.2.2. Barriers Imposed by Vulnerability

P4: “Yes, I think that people, at least my family, think I’m a drug addict and look at me as a drug addict, and that’s why I don’t get a job, because I’m not all hot to go to work”.

P6:” Oops, when I was on the street, they looked at me differently”.

P7: “Yes, I do, the recriminatory look of people”.

P8: “They look from the side (…) some people, not all”.

P9: “There were people who discriminated against me, others who tried to help me and I didn’t want to; sometimes not accepting help makes things more difficult!”

P10: “I say I have leishmaniasis and people look at me in a different way! And they ask, can you catch Filipe? If you get that scared, how much more if I said I have HIV, it’s not…”

P3:” I’ve been criticized many times and they said you’re like this because you want to, and you don’t have a job because you don’t want to. But it’s not quite like that, I was made fun of at school for not wearing designer clothes, or for being chubby, or because my mother doesn’t have a profession that is said to be worthy. My mother, always did everything to not miss us with anything…”

P2: “I have missing teeth and when I look for a job, there are people who look at me and say “we just want younger people”. My image doesn’t help me, I know, but what can I do…”

P1: “At the moment, what I feel is difficulty in integrating myself into society again, it seems that I am dependent on everything (…) I even wanted to attend professional training, but they said that it would be difficult to enter”.

P7: “At my age, it’s so hard to find a job! I’ve been looking for an alternative for months and nothing…”

P7: “(…) I have no studies. I would like to know, even more, read and write, and study at a school. I need studies and I don’t have them. I feel sad, I feel that instead of going up, I go down, because with a lack of studies everything is more difficult. Even for cleaning tasks, I need a driver’s license, I’ve been to about three or four interviews and they all ask for a driver’s license and they don’t accept me because of that, but it’s not just me, it’s with several people. Do you need a license to clean windows? For God’s sake, if they wanted to help a person in need, they wouldn’t, they wouldn’t”.

Interviewer: “(…) Can you tell me what you mean by vulnerability and human fragility? Do you know?”; P2: “No, because I have no studies”.

P6: “Wow, that’s not very easy. When I found out I had this [HIV] it wasn’t easy, you see? To accept that I had this wasn’t very easy, it didn’t really fit in my head. When I fell in the hospital, I was told what this was, now it took years and years to get it into my head. It was not easy. And even now I get anxious and stressed”.

P7: “My condition is difficult (…) my depression, there are things that I cannot deal with, they have already seen, that I am under enormous pressure. I went to treatments, I’ve been hospitalized a few times, they [professionals] know everything, but this is not easy. When a person is discouraged, sad, a person is forced to smoke a cigarette to kill the stress”.

P9: “I also had that… persecution. I also have these thoughts, that…” Interviewer: Do you think people were following you?” P9: “Yes, yes”.

3.2.3. Strategies for Dealing with Vulnerability

P2: “I turn to people who are not my family, and these are the people who give me the most support. I came to ask for help because I wanted to change”.

P3:” I think I’m having it now with InPulsar than I had before. Previously, it was not easy, I was already unemployed and was denied help many times, and now, as far as I can see, I still have no reason to complain”.

P5: “They [InPulsar] always have their doors open to help; They have professionals in the social, health and legal areas. And they even give us psychological support”.

P7: “Yes, they have helped me, nobody points the finger at me, everyone helps and supports me in here, they never point the finger at me”.

P10: “They are really tireless”. I’m so glad I came here and ask for help in time.

P1: “When I was living on the street, I had many moments when I thought that this was not life and that I had to change something. After all, living on the street is not a system”.

P6: “I am waiting to take a course, Carpentry (…). I still have time, since I didn’t learn at 18, I’m learning now at 50”.

P7: “I have to be a strong woman. After all, I have a son, it’s the most important thing in my life… It’s not with a social support check (189 euros) that I’m going to take my life forward. I need to find a job to give you a better life!”

P10: “I won’t give up, I won’t! I take methadone, it’s one of the things I want too, it’s a goal, to end methadone”.

P1:” Yes. I got HIV from someone who had it, but at the time he couldn’t tell me he had it and we had sex and it happened… he never told me he had HIV, I was very angry. But since then, I’ve never exchanged syringes with anyone, I’ve never had sex without a condom, always respecting others”.

P10: “(…) I’ve had several girls, since I have HIV it was always with a “condom” and I haven’t found the exact girl to say like that (…) Look, I have HIV”.

P1: “I don’t know. Because I lived in Belgium for 12 years and I know what it is and for me I can ignore it”.

P2: “Walking around with my face uncovered and I like to pass by and they don’t point at me (…) they’re ready to look at me, but I don’t care. Move on”.

P3: “I never waste time on what others think about me”.

P5: “I don’t know, I don’t notice it! Sometimes it’s my boyfriend who says (…) but I don’t care”.

P6: “Now I don’t know, but before it was more difficult”.

P11: “When they discriminated against me, it was without me knowing, it was behind the scenes. I recognize that sometimes pretending not to see yourself may not be enough. Then we have to give it a go!”

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Virokannas, E.; Liuski, S.; Kuronen, M. The contested concept of vulnerability–A literature review. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2018, 23, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numans, W.; Regenmortel, T.V.; Schalk, R.; Boog, J. Vulnerable persons in society: An insider’s perspective. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2021, 16, 1863598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezzina, R.; Gopikumar, V.; Jenkins, J.; Saraceno, B.; Sashidharan, S.P. Social Vulnerability and Mental Health Inequalities in the “Syndemic”: Call for Action. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 894370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.G. Vulnerability in Research: Basic Ethical Concepts and General Approach to Review. Ochsner J. 2020, 20, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, S.K.; Arafat, S.M.; Marthoenis, M.; Kabir, R. Homeless mentally ill people and COVID-19 pandemic: The two-way sword for LMICs. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, J. Vulnerable Adults and the Law; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fineman, M.A. Equality, autonomy, and the vulnerable subject in Law and politics. In Vulnerability: Reflections on a New Ethical Foundation for Law and Politics; Fineman, M.A., Grear, A., Eds.; Ashgate: Surrey, UK, 2013; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bielby, P. Not ‘us’ and ‘them’: Towards a normative legal theory of mental health vulnerability. Int. J. Law Context 2019, 15, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineman, M. The vulnerable subject and the responsive state. Emory Law J. 2010, 60, 251–275. Available online: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol60/iss2/1 (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Fineman, M. Vulnerability and Social Justice. Valpso. Univ. Law Rev. 2019, 53, 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabovschi, C.; Loignon, C.; Fortin, M. Mapping the concept of vulnerability related to health care disparities: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaskerud, J.; Winslow, B.J. Conceptualizing vulnerable population’s health-related research. Nurs. Res. 1998, 47, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, J.; Santos, A.; Costa, L.; Lima, A.; Lima, J.; Vasconcelos, B. Vulnerability and its dimensions: Reflections on Nursing care for human groups. Rev. Enferm. UERJ 2020, 28, e39222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Evans, G. Developmental science in the 21st century: Emerging questions, theoretical models, research designs and empirical findings. Soc. Dev. 2000, 9, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamwey, M.; Allen, L.; Hay, M.; Varpio, L. Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Model of Human Development: Applications for Health Professions Education. Acad. Med. 2019, 10, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozaei, J.; Chuang, W.; Allen, C.; Garmestani, A. Social vulnerability, social-ecological resilience and coastal governance. Glob. Sustain. 2022, 5, E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, A.; Gouveia, J.P.; Schmidt, L.; Sousa, J.C.; Simões, S. Energy poverty in Portugal: Combining vulnerability mapping with household interviews. Energy Build. 2019, 203, 109423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, S.; Carvalho, B.; Esteves, M. Portugal, Balanço Social 2021. Um Retrato do País e dos Efeitos da Pandemia. Lisboa: Nova SBE Economics for Policy Knowledge Center, Fundação “la Caixa”, BPI, 2021. Available online: https://www.novasbe.unl.pt/Portals/0/Files/Reports/SEI%202021/Relat%F3rio%20Balan%E7o%20Social_Janeiro%202022.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Peroni, P.; Timmer, A. Vulnerable groups: The promise of an emerging concept in European Human Rights Convention law. Int. J. Const. Law 2013, 11, 1056–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvale, G.; Moll, S.; Miatello, A.; Robert, G.; Larkin, M.; Palmer, V.; Powell, A.; Gable, C.; Girling, M. Codesigning health and other public services with vulnerable and disadvantaged populations: Insights from an international collaboration. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S.; Barker, S.; Kaur, R.; Kerry, F.; Mitchell, W.; Happs, A.; Fry, G.; Morrison, V.; Fortinsky, R.; Oyebode, J. Involving minority ethnic communities and diverse experts by experience in dementia research: The caregiving HOPE study. Dementia 2018, 17, 990–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken-Roche, D.; Bell, E.; Macdonald, M.E.; Racine, E. The Concept of ‘Vulnerability’ in Research Ethics: An In-Depth Analysis of Policies and Guidelines. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2017, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, J.; Austin, Z. Qualitative research: Data collection, analysis, and management. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2015, 68, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Amann, J.; Sleigh, J. Too Vulnerable to Involve? Challenges of Engaging Vulnerable Groups in the Co-production of Public Services through Research. Int. J. Public Adm. 2021, 44, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett, D.K. Qualitative Methods in Social Work Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ten Have, H.; Gordijn, B. Vulnerability in light of the COVID-19 crisis. Med. Health Care Philos. 2021, 24, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuran, C.; Morsut, C.; Kruke, B.; Krüger, M.; Segnestam, L.; Orru, K.; Nævestad, T.O.; Airola, M.; Keränen, J.; Gabel, F.; et al. Torpan Vulnerability and vulnerable groups from an intersectionality perspective. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, M.; Guizardi, F. The concept of vulnerability and its meanings for public policies in health and social welfare. Cad. Saúde Pública 2018, 34, e00101417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, C.; Schneider, D. Vulnerabilidade, família e o uso de drogas: Uma revisão integrativa de literatura. Psic. Ver. 2021, 30, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calpe-López, C.; Martínez-Caballero, M.A.; García-Pardo, M.P.; Aguilar, M.A. Resilience to the effects of social stress on vulnerability to developing drug addiction. World J. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 24–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.M. A Representação da Vulnerabilidade Humana Como Motor Para a Recuperação do Paradigma do Cuidar em Saúde; The Representation of Human Vulnerability as an Engine for the Recovery of the Health Care Paradigm. Doctoral Thesis, Universidade Católica Portuguesa (UCP), Porto, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bühlmann, F. Trajectories of Vulnerability: A Sequence-Analytical Approach. In Social Dynamics in Swiss Society. Life Course Research and Social Policies; Tillmann, R., Voorpostel, M., Farago, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 9, pp. 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Paugam, S. Les Formes Élémentaires de la Pauvreté; PUF: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Obasuyi, F.; Rasiah, R.; Chenayah, S. Identification of Measurement Variables for Understanding Vulnerability to Education Inequality in Developing Countries: A Conceptual Article. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020919495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisser-Lohmann, E. Ethical aspects of vulnerability in research. Poiesis Prax. 2012, 9, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. The Principle of Respect for Human Vulnerability and Personal Integrity; Report of the International Bioethics Committee of UNESCO; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013.

- Venter, I.; Wyk, N. Experiences of vulnerability due to loss of support by aged parents of emigrated children: A hermeneutic literature review. Community Work Fam. 2019, 22, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsen, C. Vulnerability in homeless adolescents: Concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2819–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaslip, V.; Hean, S.; Parker, J. Lived experience of vulnerability from a Gypsy Roma Traveller perspective. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 1987–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajoie, C.; Fortin, J.; Racine, E. Enriching our understanding of vulnerability through the experiences and perspectives of individuals living with mental illness. Account Res. 2019, 26, 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guignon, C. On Being Authentic; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff, K.; Krohn, H.; Crawley, J.; Howard, M.; Zadeh, P.M.; Varacalli, F.; Ravi, P.; Sattler, D. The little things are big: Evaluation of a compassionate community approach for promoting the health of vulnerable persons. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardcastle, S.J.; Hancox, J.; Hattar, A.; Maxwell-Smith, C.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Hagger, M.S. Motivating the unmotivated: How can health behavior be changed in those unwilling to change? Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biggs, A.; Brough, P.; Drummond, S. Lazarus and Folkman’s psychological stress and coping theory. In The Handbook of Stress and Health: A Guide to Research and Practice; Cooper, C.L., Quick, J.C., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: West Sussex, UK, 2017; pp. 351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Condon, L.; Bedford, H.; Ireland, L.; Kerr, S.; Mytton, J.; Richardson, Z.; Jackson, C. Engaging gypsy, Roma, and traveller communities in research: Maximizing opportunities and overcoming challenges. Qual. Health Res. 2019, 29, 1324–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey-Pearce, G.; Walker, S.; Fairgrieve, S.; Parker, M.; Rapley, T. The burden of proof: The process of involving young people in research. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomm-Bonde, L. The Naïve nurse: Revisiting vulnerability for nursing. BMC Nurs. 2012, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torralba i Roselló, F. Ética del Cuidar; Editorial MAPFRE: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Conalogue, D.; Maunder, N.; Areington, A.; Martin, K.; Clarke, V.; Scott, S. Homeless people and health: A qualitative enquiry into their practices and perceptions. J. Public Health 2021, 43, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Age (Years) | Sex | Educational Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 43 | Male | 7th year (3rd cycle of basic education) |

| P2 | 56 | Female | 3rd year (1st cycle of basic education) |

| P3 | 24 | Female | 9th year (3rd cycle of basic education) |

| P4 | 41 | Female | 7th year (3rd cycle of basic education) |

| P5 | 25 | Female | 12th grade (secondary school) |

| P6 | 49 | Male | Attended basic school but never finished |

| P7 | 49 | Female | 2nd year (1st cycle of basic education) |

| P8 | 65 | Male | 4th year (1st cycle of basic education) |

| P9 | 34 | Male | 8th year (3rd cycle of basic education) |

| P10 | 42 | Male | 7th year (3rd cycle of basic education) |

| P11 | 67 | Male | 9th year (3rd cycle of basic education) |

| P12 | 31 | Female | 9th year (3rd cycle of basic education) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laranjeira, C.; Piaça, I.; Vinagre, H.; Vaz, A.R.; Ferreira, S.; Cordeiro, L.; Querido, A. Vulnerability through the Eyes of People Attended by a Portuguese Community-Based Association: A Thematic Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1819. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101819

Laranjeira C, Piaça I, Vinagre H, Vaz AR, Ferreira S, Cordeiro L, Querido A. Vulnerability through the Eyes of People Attended by a Portuguese Community-Based Association: A Thematic Analysis. Healthcare. 2022; 10(10):1819. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101819

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaranjeira, Carlos, Inês Piaça, Henrique Vinagre, Ana Rita Vaz, Sofia Ferreira, Lisete Cordeiro, and Ana Querido. 2022. "Vulnerability through the Eyes of People Attended by a Portuguese Community-Based Association: A Thematic Analysis" Healthcare 10, no. 10: 1819. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101819

APA StyleLaranjeira, C., Piaça, I., Vinagre, H., Vaz, A. R., Ferreira, S., Cordeiro, L., & Querido, A. (2022). Vulnerability through the Eyes of People Attended by a Portuguese Community-Based Association: A Thematic Analysis. Healthcare, 10(10), 1819. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10101819