Can the AD-AS Model Explain the Presence and Persistence of the Underground Economy? Evidence from Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

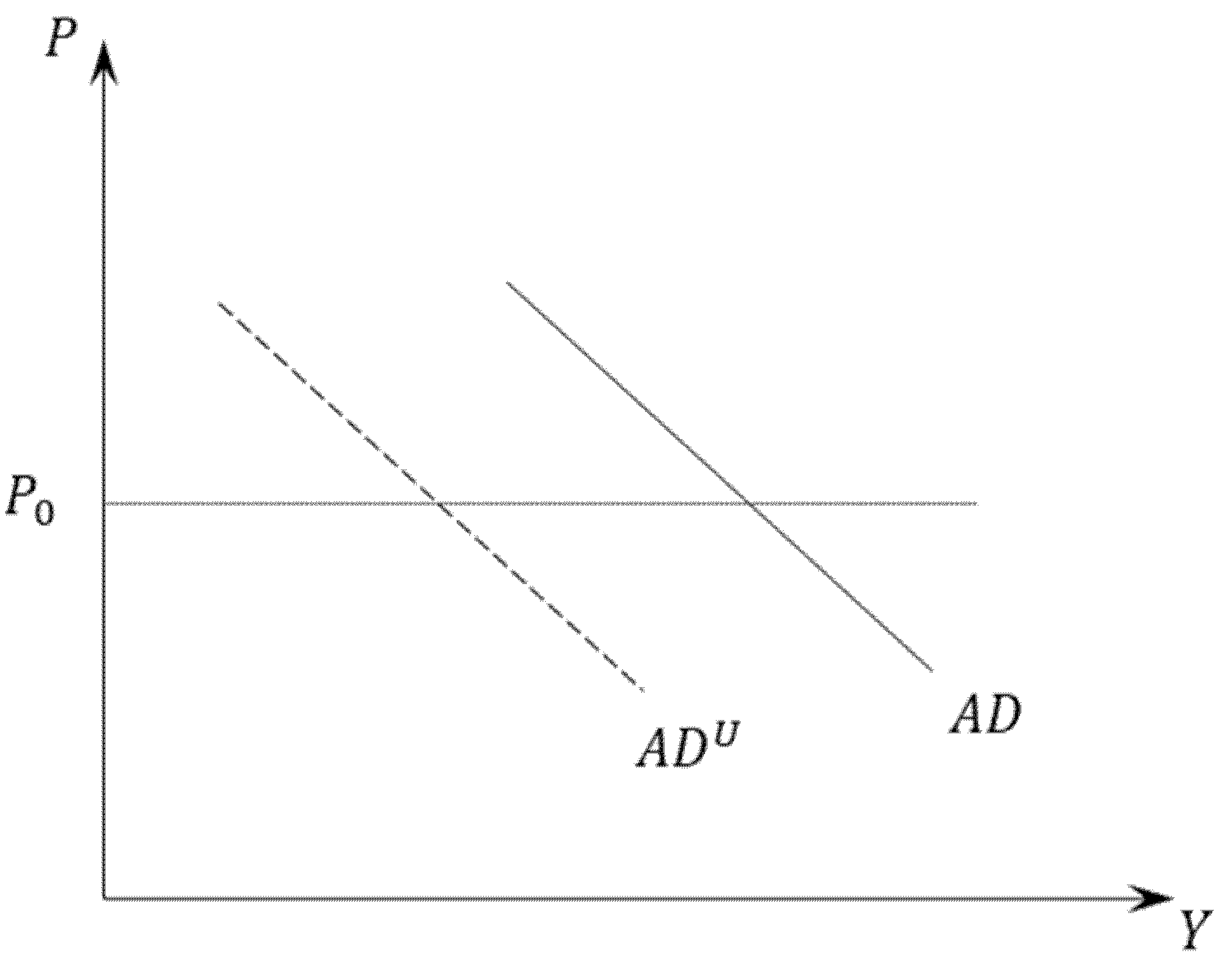

2. The AD with Tax Evasion

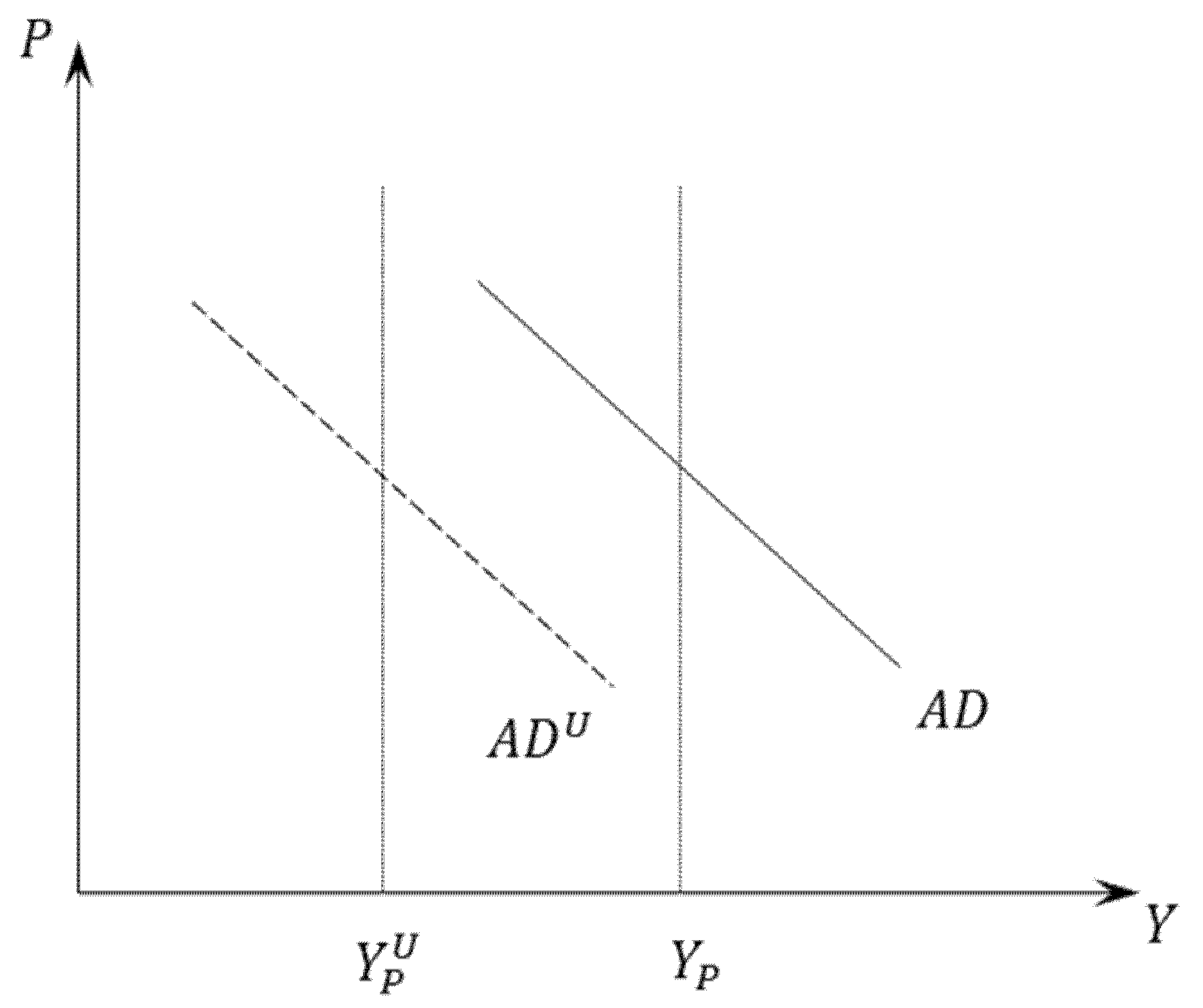

3. The Underground Economy and the Potential Output

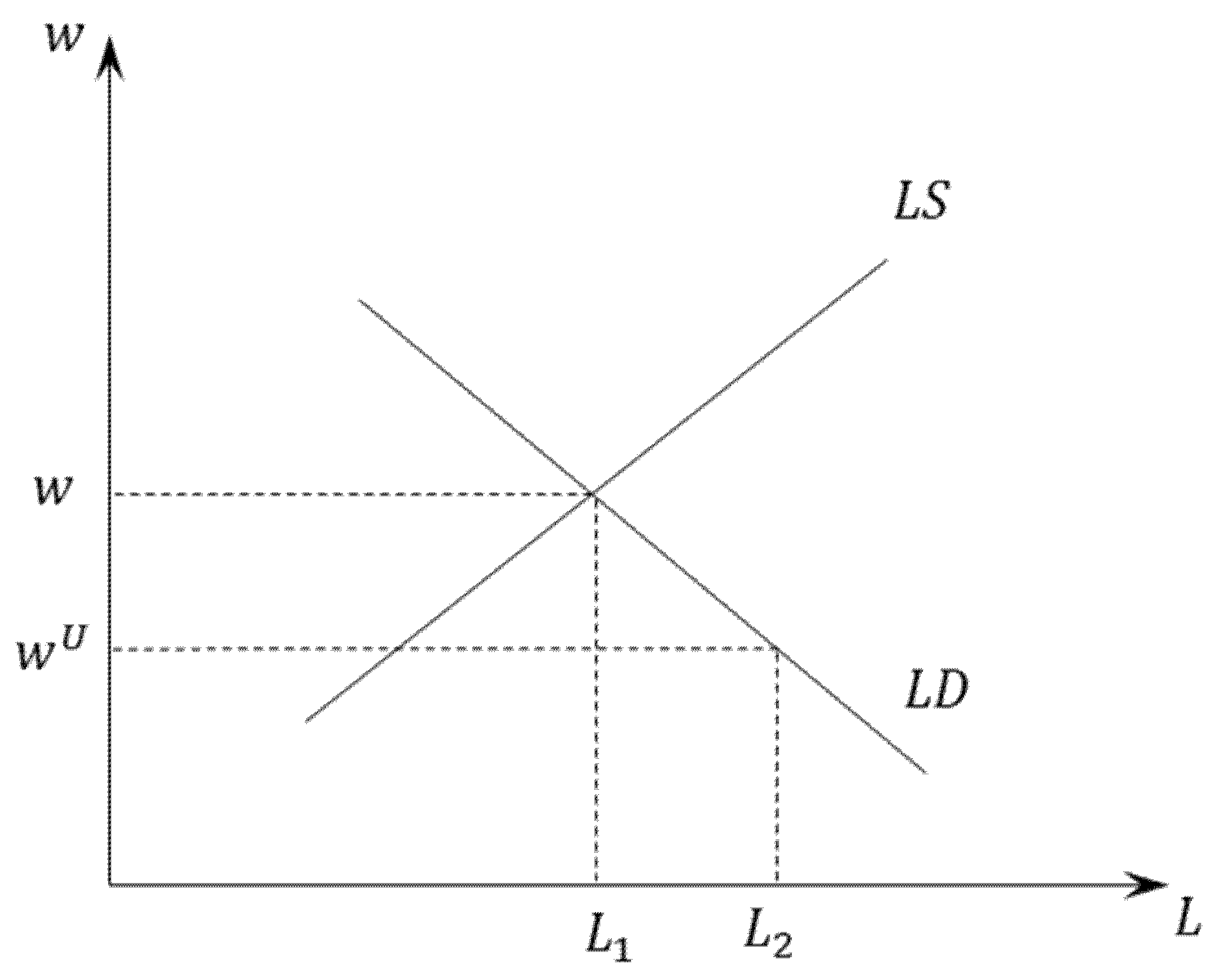

4. The AS with Undeclared Work

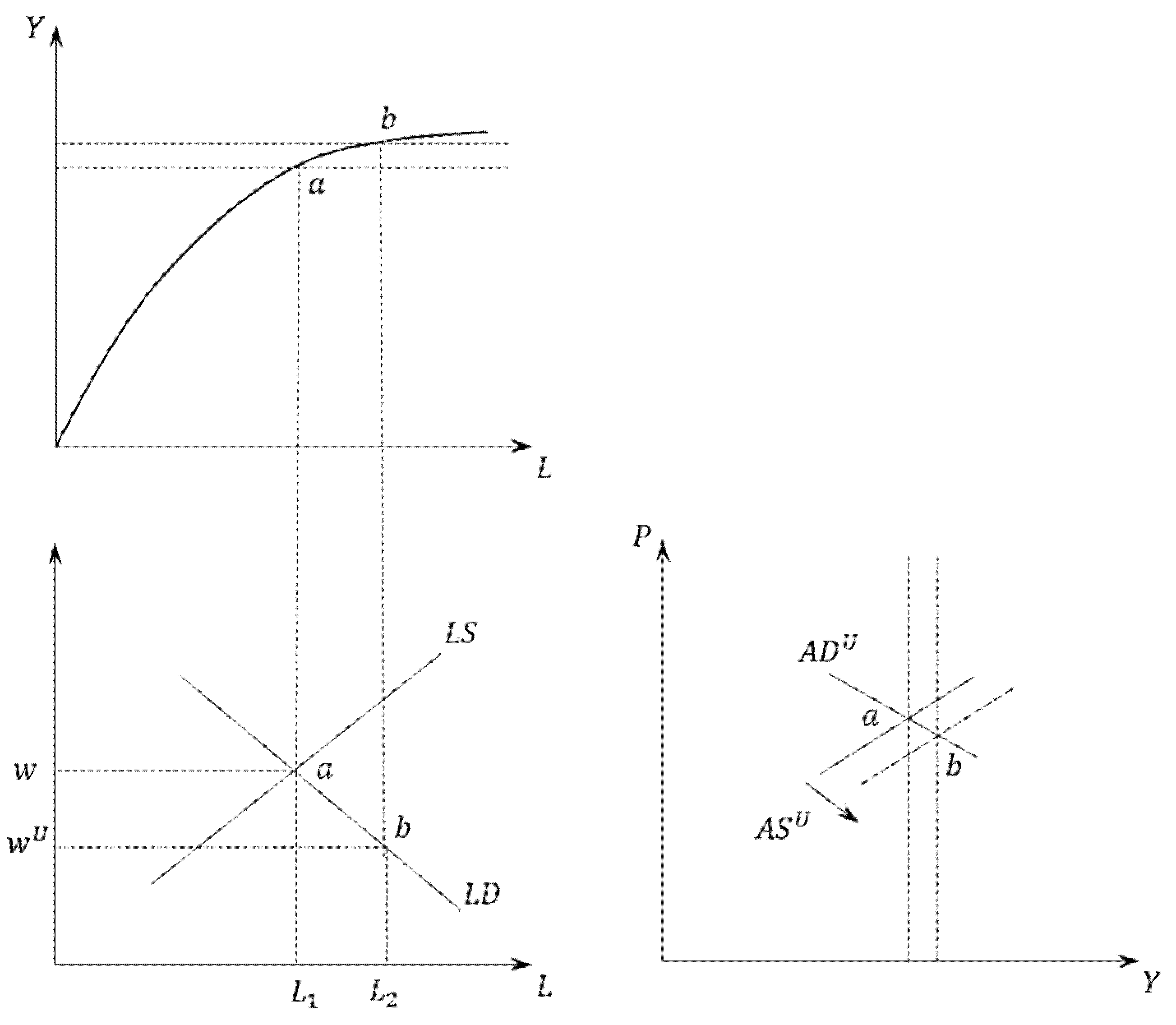

5. The Extended AD-AS Model: A Simple Comparison

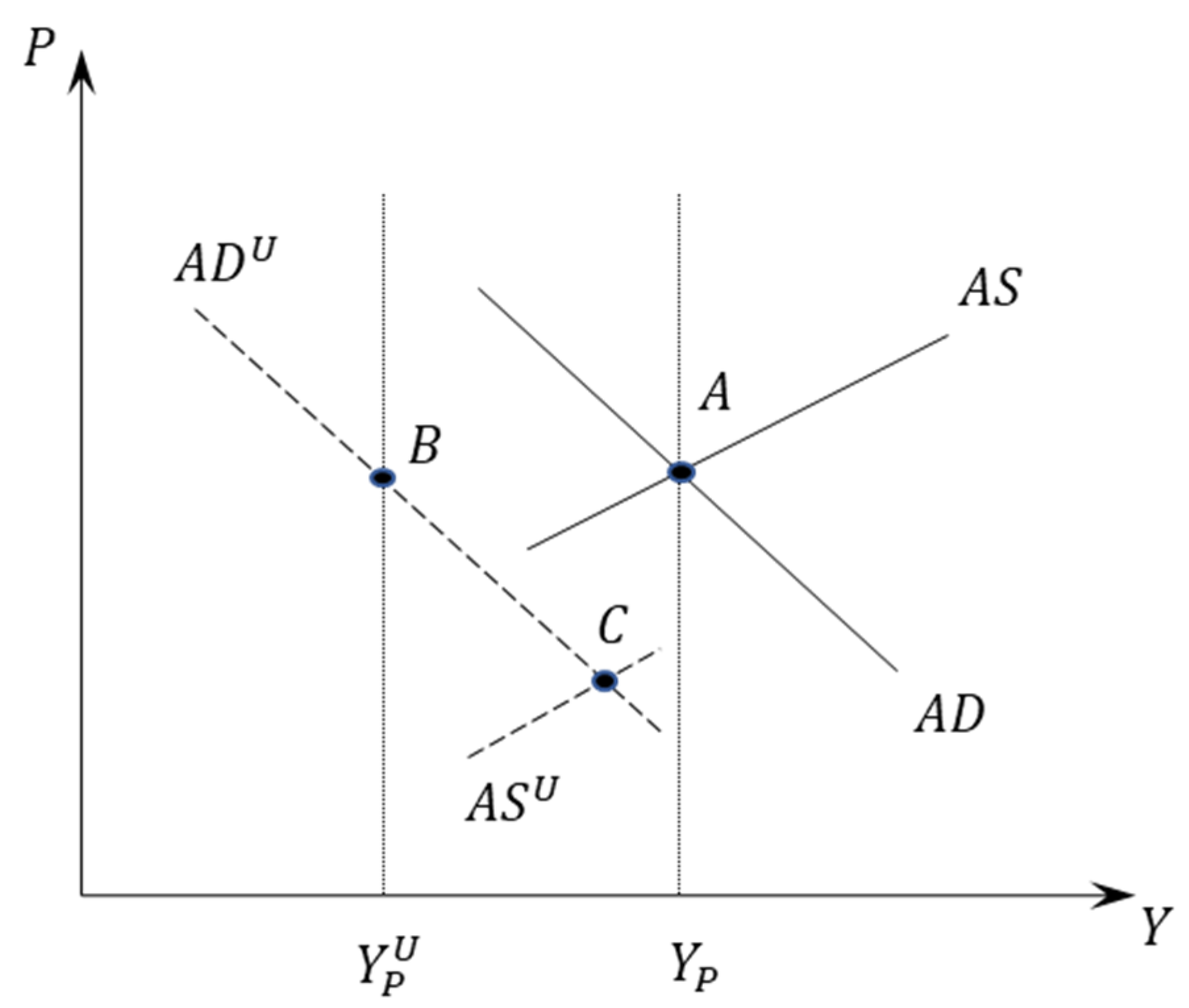

- Point characterises the short-run equilibrium of an economy with a large share of the underground economy (where a supply-side positive shock exists);

- Point characterises the long-run equilibrium of an economy with a large share of the underground economy (where the potential output is lower);

- Point characterises the equilibrium of an economy with a low share of the underground economy (where both the potential output and the AD are higher). In this case, point A is both the short-run equilibrium and the long-run equilibrium.

Discussion: Economic Outcomes and Policy Implications

- In the short run, if the positive effect of the underground economy on both the employment level and the actual level of output is significant (i.e., the lowers much) point could be a potentially better situation than point , since the cost of living is lower, and the purchasing power is higher. Furthermore, point C approaches point A in terms of output .

- In the long run, instead, the reverse is true: point is a better situation than point , since the potential output is lower in the presence of a larger share of the underground economy.

- If the main goal of policy makers is the economic growth, they should devote their greatest efforts to fighting against the underground economy.

- If the policymakers look especially at the present, the underground economy could be to some extent tolerated (in some countries, it seems that this happens).

6. Empirical Analysis

- -

- The coefficient is the impact in the current time period (it is usually called the impact multiplier);

- -

- The coefficients , , and are the effects in the previous time periods (they are usually called the interim multipliers);

- -

- The total effect of on is instead called the long-run equilibrium effect and is given by: . Since in the long run long-run equilibrium (in a steady-state equilibrium, exactly): .

- In model (12), the correlation between and is always negative and, in many cases, statistically significant. Hence, both the short-run correlation and the long-run correlation between the shadow economy and economic growth are negative.

- In model (13), instead, the correlation between and is negative (although quite small) and statistically significant only at the current time period (at the time ). Hence, the short-run correlation between the shadow economy and unemployment is negative and, thus, the short-run correlation between the shadow economy and employment is positive.

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Recent estimates suggest that the informal economy comprises more than half of the global labor force (International Labor Organization 2020) and around one third of GDP worldwide (Medina and Schneider 2018). |

| 2 | |

| 3 | Mazhar and Méon (2017), instead, assume that a government has two instruments to finance a given level of public spending: a flat tax on output and seigniorage. Hence, their result of a positive relation between shadow economy and inflation relies on the possibility that a government can control monetary policy, namely there is not an independent central bank. |

| 4 | We consider as (partly) exogenous to taxes, since there are numerous other determinants affecting the share of the underground economy. Indeed, the size of the underground economy has many causes, including not only tax burden, but also corruption, organised crime, government instability, low quality of political institutions and weak rule of law (see, e.g., Medina and Schneider 2017, 2018). |

| 5 | When the goods market is in equilibrium, the aggregate expenditure is equal to real output (). |

| 6 | Recall that in the space, the is downward sloping because of three well-known effects: wealth effect (the negative effect of prices on consumption), interest rate effect (the negative effect of prices on investment) and international effect (the negative effect of prices on net exports). For the international effect to occur, of course, it needs to assume that the exchange rate does not change. |

| 7 | By definition, a higher level of potential GDP implies a lower natural unemployment rate. This is consistent with the empirical finding that (at least in advanced countries) productivity growth is strongly negatively correlated with unemployment in the long run (see Pissarides and Vallanti 2007). |

| 8 | Formally, the potential output can be represented by a long-run production function where the main inputs (in addition to the labour factor) are physical capital, infrastructure and public capital, human capital, entrepreneurship and technological progress. Of course, the potential output is not affected by demand factors and, thus, the AD movements will only have effects on prices. |

| 9 | The aggregate supply is upward sloping in the (𝑃 − 𝑌) space, meaning that when aggregate demand changes, firms adjust both price and quantity (for example, when aggregate demand increases, firms increase both price and quantity). Note that in this case there is a potential active role for economic policy: government and central bank can increase (by means of expansive economic policies) the actual level of GDP at the cost of higher inflation (an increase in the percentage change in the price index). |

| 10 | The Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) measures the regional underground employment rate, namely the ratio between the regional underground employment and the regional total employment. We use this variable as a proxy for the regional shadow economy. This is consistent with the theoretical model where the underground economy plays a key role on the supply-side of the labour market. |

| 11 | Usually, the optimal lag-length is obtained by using a relatively large number of lags and choosing the model with the lowest value of AIC, SBC or any other criterion. However, this approach generates two considerable problems: (1) a large number of lags can give rise to a severe multicollinearity problem; (2) a large number of lags means a considerable loss of degrees of freedom, i.e., many additional parameters to estimate. Another solution, it could be the so-called “Koyck transformation” that introduces a lagged term of the dependent variable. In that case the DL model (9) becomes: , where , is the immediate effect of on , while is the long-run effect of on under the steady-state equilibrium condition, i.e., . In dynamic panel models that include the presence of a lagged dependent variable among the regressors, however, the traditional OLS estimators are biased and, thus, different and more sophisticated methods of estimation need to be used. |

| 12 | Note that the null hypothesis that all region-specific unobserved effects are null (all = 0) is rejected. Thus, the fixed-effects model seems to be an appropriate specification. |

References

- Abdel-Latif, Hany, Bazoumana Ouattara, and Phil Murphy. 2017. Catching the mirage: The shadow impact of financial crises. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 65: 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aizenman, Joshua, Yothin Jinjarak, Hien Thi Kim Nguyen, and Donghyun Park. 2019. Fiscal space and government-spending and tax-rate cyclicality patterns: A cross-country comparison, 1960–2016. Journal of Macroeconomics 60: 229–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, James, Lucas Navarro, and Susan Vroman. 2009. The effects of labour market policies in an economy with an informal sector. Economic Journal 119: 1105–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, Toichiro, Pu Chen, Carl Chiarella, and Peter Flaschel. 2006. Keynesian dynamics and the wage-price spiral. A baseline disequilibrium approach. Journal of Macroeconomics 28: 90–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bajada, Christopher. 2003. Business cycle properties of the legitimate and underground economy in Australia. Economic Record 79: 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeri, Tito, and Pietro Garibaldi. 2002. Shadow Activity and Unemployment in a Depressed Labour Market. CEPR Discussion Papers, 3433. June. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=323388 (accessed on 17 August 2002).

- Boeri, Tito, and Pietro Garibaldi. 2005. Shadow sorting, NBER Chapters. In NBER International Seminar on Macroeconomics. Edited by Jeffrey A. Frankel and Christopher Pissarides. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 125–63. [Google Scholar]

- Catalina, Granda, and Danny García. 2020. Informality, Tax Policy and the Business Cycle: Exploring The Links. Documento de Trabajo, Alianza EFI-Colombia Científica, Número de serie: WP5-2020-001. Bogotá: Alianza EFI. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Pu, and Peter Flaschel. 2005. Keynesian Dynamics and the Wage-Price Spiral: Identifying Downward Rigidities. Computational Economics 25: 115–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Pu, and Peter Flaschel. 2006. Measuring the interaction of Wage and Price Phillips Curves for the US economy. Studies in Nonlinear Dynamics and Econometrics 10: 10–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Pu, Carl Chiarella, Peter Flaschel, and Willi Semmler. 2006. Keynesian macrodynamics and the Phillips curve. An estimated baseline macro-model for the U.S. economy. In Quantitative and Empirical Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamic Macromodels. Contributions to Economic Analysis. Edited by Carl Chiarella, Reiner Franke, Peter Flaschel and Willi Semmler. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Çiçek, Deniz, and Ceyhun Elgin. 2011. Cyclicality of fiscal policy and the shadow economy. Empirical Economics 41: 725–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, Emilio, Luisanna Onnis, and Patrizio Tirelli. 2016. Shadow economies at times of banking crises: Empirics and theory. Journal of Banking & Finance 62: 180–190. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, Emilio, Lorenzo Menna, and Patrizio Tirelli. 2019. Informality and the labor market effects of financial crises. World Development 119: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, Amitava Krishna, and Peter Skott. 2006. Keynesian Theory and the AD–AS Framework: A Reconsideration. Contributions to Economic Analysis 277: 149–72. [Google Scholar]

- Elgin, Ceyhun. 2012. Cyclicality of Shadow Economy. Economic Papers 31: 478–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, Ceyhun, and Ferda Erturk. 2019. Informal economies around the world: Measures, determinants and consequences. Eurasian Economic Review 9: 221–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, Ceyhun, and Burak R. Uras. 2013. Public debt, sovereign default risk and shadow economy. Journal of Financial Stability 9: 628–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eng, Yoke-Kee, and Chin-Yoong Wong. 2008. A short note on business cycles of underground output: Are they asymmetric? Economics Bulletin 3: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Flaschel, Peter, Gangolf Groh, Christian Proaño, and Willi Semmler. 2008a. Estimation and Analysis of an Extended AD–AS Model. Topics in Applied Macrodynamic Theory, DMEF 10: 137–212. [Google Scholar]

- Flaschel, Peter, Reiner Franke, and Christian Proaño. 2008b. On the (In)Determinacy of New Keynesian Models with Staggered Wages and Prices. Mimeo: Bielefeld University. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, Jeffrey, Carlos Vegh, and Guillermo Vuletin. 2013. On graduation from fiscal procyclicality. Journal of Development Economics 100: 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, Robert E., and Charles I. Jones. 1999. Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? Quarterly Journal of Economics 114: 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2011. Statistical Update on Employment in the Informal Economy. Geneva: ILO. [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Organization. 2020. 13. Informal Economy. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/dw4sd/themes/informal-economy/lang--en/index.htm#33 (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- La Porta, Rafael, and Andrei Shleifer. 2008. The unofficial economy and economic development. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 39: 275–363. [Google Scholar]

- Loayza, Norman, and Jamele Rigolini. 2011. Informal Employment: Safety Net or Growth Engine? World Development 39: 1503–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankiw, N. Gregory. 2015. Essentials of Economics, 7th ed. North Way: Cengage Learning EMEA. [Google Scholar]

- Mazhar, Ummad, and Pierre-Guillaume Méon. 2017. Taxing the unobservable: The impact of the shadow economy on inflation and taxation. World Development 90: 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Medina, Leandro, and Friedrich Schneider. 2017. Shadow Economies around the World: New Results for 158 Countries over 1991–2015. CESifo Working Papers, No. 6430. Munich: CESifo. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, Leandro, and Friedrich Schneider. 2018. Shadow Economies Around the World: What Did We Learn Over the Last 20 Years? International Monetary Fund (IMF) Working Paper No. 18/17. Washington, DC: IMF. [Google Scholar]

- Pissarides, Christopher, and Giovanna Vallanti. 2007. The impact of TFP growth on steady-state unemployment. International Economic Review 48: 607–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, David. 2006. Advanced Macroeconomics, 3rd ed. New York and London: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Friedrich, and Dominik H. Enste. 2000. Shadow economies: Size, causes, and consequences. Journal of Economic Literature 38: 77–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schneider, Friedrich, and Dominik H. Enste. 2002. Hiding in the Shadows. The Growth of the Underground Economy. Economic Issues N° 30, International Monetary Fund (March). Washington, DC: IMF. [Google Scholar]

- Toichiro, Asada, Pu Chen, Carl Chiarella, and Peter Flaschel. 2006. AD–AS and the Phillips Curve: A Baseline Disequilibrium Model. Contributions to Economic Analysis 277: 173–227. [Google Scholar]

- Toichiro, Asada, Carl Chiarella, Peter Flaschel, and Proaño Christian. 2007. Keynesian AD-AS, Quo Vadis? Working Paper Series 151; Sydney: Finance Discipline Group, UTS Business School, University of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Torgler, Benno. 2007. Tax Compliance and Tax Morale: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Vegh, Carlos, and Guillermo Vuletin. 2015. How Is Tax Policy Conducted over the Business Cycle? American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7: 327–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | Model (12) | Model (13) |

|---|---|---|

| −0.241 (2.49) * | −0.017 (2.01) * | |

| −0.236 (2.19) * | 0.101 (1.65) | |

| −0.258 (1.67) | −0.012 (1.51) | |

| −0.216 (1.71) | 0.099 (1.79) | |

| −0.188 (2.08) * | 0.012 (1.84) | |

| Statistical tests | ||

| F test all = 0 | Prob > F 0.000 | Prob > F 0.000 |

| R2 overall | 0.4635 | 0.5072 |

| Observations 220 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lisi, G. Can the AD-AS Model Explain the Presence and Persistence of the Underground Economy? Evidence from Italy. Economies 2021, 9, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040170

Lisi G. Can the AD-AS Model Explain the Presence and Persistence of the Underground Economy? Evidence from Italy. Economies. 2021; 9(4):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040170

Chicago/Turabian StyleLisi, Gaetano. 2021. "Can the AD-AS Model Explain the Presence and Persistence of the Underground Economy? Evidence from Italy" Economies 9, no. 4: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040170

APA StyleLisi, G. (2021). Can the AD-AS Model Explain the Presence and Persistence of the Underground Economy? Evidence from Italy. Economies, 9(4), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040170