Work from Home: Measuring Satisfaction between Work–Life Balance and Work Stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Working from Home

2.2. Work–Life Balance

2.3. Work Stress

2.4. Job Satisfaction

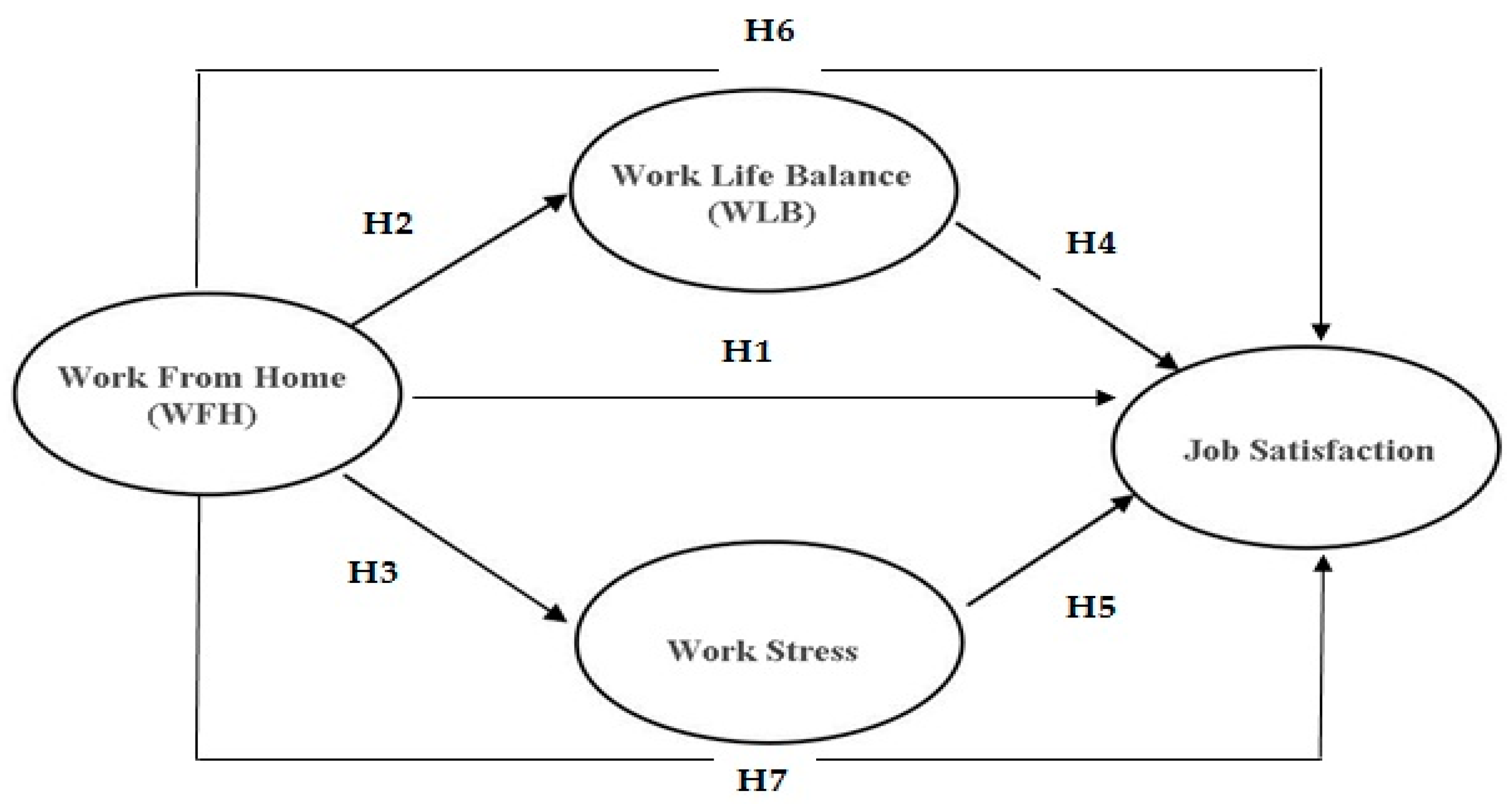

3. Material and Methods

4. Data Analysis and Results

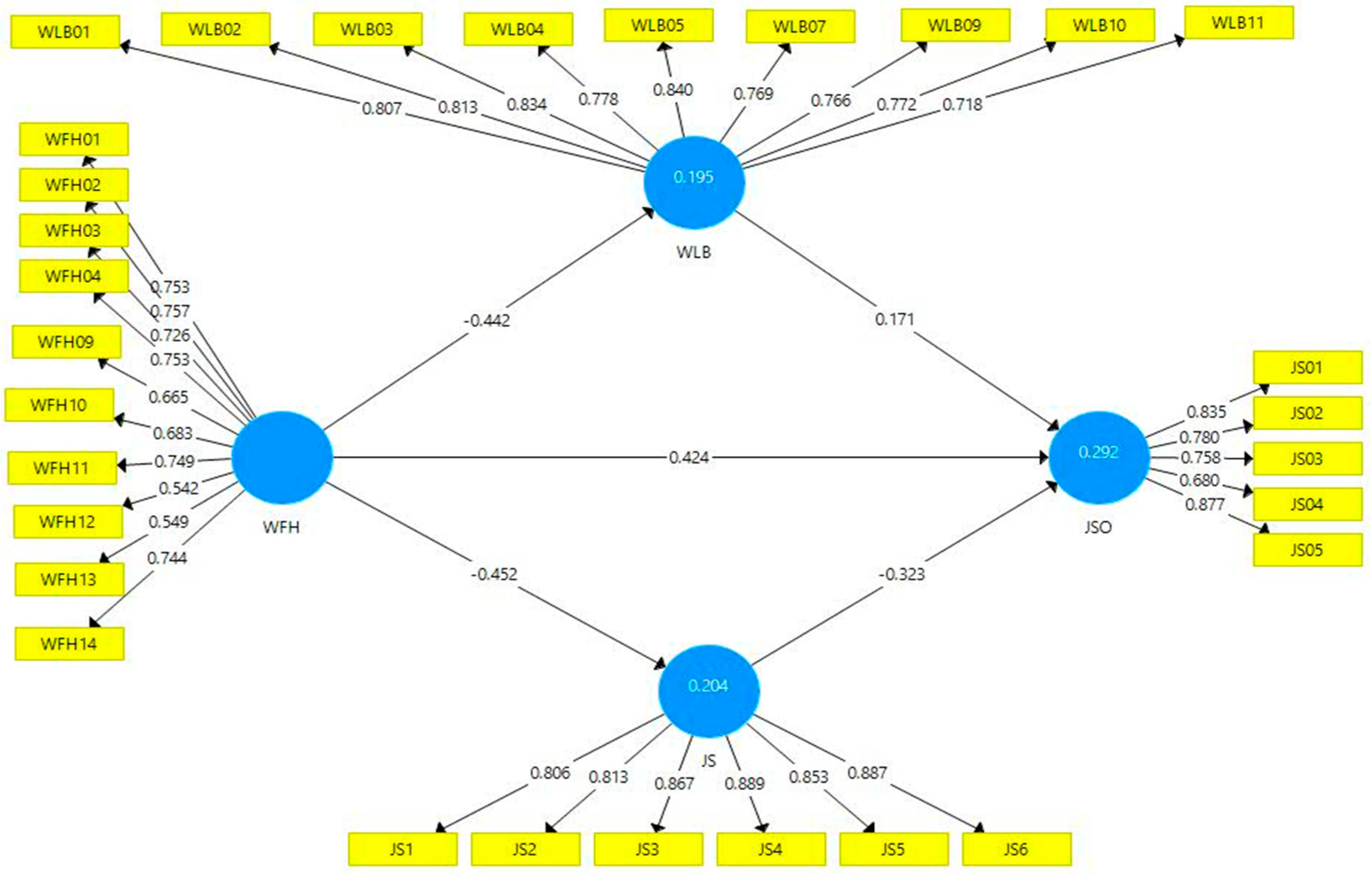

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

Q2 = 1 − (1 − 0.292)(1 − 0.204)(1 − 0.195)

Q2 = 1 − 0.479

Q2 = 0.521

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. (Survey Items)

References

- Ammons, Samantha K., and William T. Markham. 2004. Working at Hdome: Experiences of Skilled White Collar Workers. Sociological Spectrum 24: 191–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Amanda J., Seth A. Kaplan, and Ronald P. Vega. 2015. The Impact of Telework on Emotional Experience: When, and for Whom, Does Telework Improve Daily Affective Well-Being? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 24: 882–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarbouyeh, Amir, and Seyed Gholamreza Jalali Naini. 2014. A Study on the Effect of Teleworking on Quality of Work Life. Management Science Letters 4: 1063–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baruch, Yehuda. 2000. Baruch-2000-New Technology, Work and Employment Qualis A1 Muito Importante. New Technology, Work and Employment (Print) 15: 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Yehuda. 2001. The Status of Research on Teleworking and an Agenda for Future Research. International Journal of Management Reviews 3: 113–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzunegui-Eraso, Angel, and Amaya Erro-Garcés. 2020. Teleworking in the Context of the Covid-19 Crisis. Sustainability 12: 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, Tim Andrew, Stephen T. T. Teo, Laurie McLeod, Felix Tan, Rachelle Bosua, and Marianne Gloet. 2016. The Role of Organisational Support in Teleworker Wellbeing: A Socio-Technical Systems Approach. Applied Ergonomics 52: 207–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Ming Che, Rong Chang Jou, Cing Chu Liao, and Chung Wei Kuo. 2015. Workplace Stress, Job Satisfaction, Job Performance, and Turnover Intention of Health Care Workers in Rural Taiwan. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health 27: NP1827–NP1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Heejung. 2018. Future of Work and Flexible Working in Estonia: The Case of Employee-Friendly Flexibility. Tallin: Arenguseire Keskus, p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Heejung, and Tanja van der Lippe. 2020. Flexible Working, Work–Life Balance, and Gender Equality: Introduction. Social Indicators Research 151: 365–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clark, Andrew E. 1996. Job Satisfaction in Britain. British Journal of Industrial Relations 34: 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, Marja, and Robert A. W. Kok. 2014. Workplace Flexibility and New Product Development Performance: The Role of Telework and Flexible Work Schedules. European Management Journal 32: 564–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Aaron, and Efrat Liani. 2009. Work-Family Conflict among Female Employees in Israeli Hospitals. Personnel Review 38: 124–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, Francoise, Elif Baykal, and Ghulam Abid. 2020. E-Leadership and Teleworking in Times of COVID-19 and Beyond: What We Know and Where Do We Go. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, Vittorio, and Linda Wirth. 1990. Telework: A New Way of Working and Living. International Labour Review 129: 529–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Selwyn T., and Robert L. Webster. 1998. IS Managers’ Innovation toward Telecommuting: A Structural Equation Model. Proceedings of the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 4: 161–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedáková, Denisa, and Lucia Ištoňová. 2017. Slovak IT-Employees and New Ways of Working: Impact on Work-Family Borders and Work-Family Balance. Československá Psychologie (Czechoslovak Psychology) LXI: 68–83. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Gwenith G., Carrie A. Bulger, and Carlla S. Smith. 2009. Beyond Work and Family: A Measure of Work/Nonwork Interference and Enhancement. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 14: 441–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonner, Kathryn L., and Michael E. Roloff. 2010. Why Teleworkers Are More Satisfied with Their Jobs than Are Office-Based Workers: When Less Contact Is Beneficial. Journal of Applied Communication Research 38: 336–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, Ravi S., and David A. Harrison. 2007. The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown About Telecommuting: Meta-Analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology 92: 1524–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gálvez, Ana, Francisco Tirado, and Jose M. Alcaraz. 2020. ‘Oh! Teleworking!’ Regimes of Engagement and the Lived Experience of Female Spanish Teleworkers. Business Ethics 29: 180–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, Timothy D., and Kimberly A. Eddleston. 2020. Is There a Price Telecommuters Pay? Examining the Relationship between Telecommuting and Objective Career Success. Journal of Vocational Behavior 116: 103348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbrecht, Margo, Susan M. Shaw, Laura C. Johnson, and Jean Andrey. 2008. ‘I’m Home for the Kids’: Contradictory Implications for Work-Life Balance of Teleworking Mothers. Gender Work and Organization 15: 454–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbrecht, Margo, Susan M. Shaw, Laura C. Johnson, and Jean Andrey. 2013. Remixing Work, Family and Leisure: Teleworkers’ Experiences of Everyday Life. New Technology, Work and Employment 28: 130–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Ya Yuan, Chyi Huey Bai, Chien Ming Yang, Ya Chuan Huang, Tzu Ting Lin, and Chih Hung Lin. 2019. Long Hours’ Effects on Work-Life Balance and Satisfaction. BioMed Research International. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jackson, Leon T. B., and Edwina I. Fransman. 2018. Flexi Work, Financial Well-Being, Work–Life Balance and Their Effects on Subjective Experiences of Productivity and Job Satisfaction of Females in an Institution of Higher Learning. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 21: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Laura C., Jean Andrey, and Susan M. Shaw. 2007. Mr. Dithers Comes to Dinner: Telework and the Merging of Women’s Work and Home Domains in Canada. Gender, Place and Culture 14: 141–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, Sree V., and P. Jyothi. 2012. Assessing Work-Life Balance: From Emotional Intelligence and Role Efficacy of Career Women. Advances in Management 5: 332. [Google Scholar]

- Kazekami, Sachiko. 2020. Mechanisms to Improve Labor Productivity by Performing Telework. Telecommunications Policy 44: 101868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jaeseung, Julia R. Henly, Lonnie M. Golden, and Susan J. Lambert. 2019. Workplace Flexibility and Worker Well-Being by Gender. Journal of Marriage and Family. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, Alison M., and Robert Mangel. 2000. The Impact of Work-Life Programs on Firm Productivity. Strategic Management Journal 21: 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, Ellen Ernst, Brenda A. Lautsch, and Susan C. Eaton. 2006. Telecommuting, Control, and Boundary Management: Correlates of Policy Use and Practice, Job Control, and Work-Family Effectiveness. Journal of Vocational Behavior 68: 347–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Amit, and Karen Z. Kramer. 2020. The Potential Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Occupational Status, Work from Home, and Occupational Mobility. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lait, Jana, and Jean E. Wallace. 2002. Stress at Work: A Study of Organizational-Professional Conflict and Unmet Expectations. Relations Industrielles 57: 463–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, D. J., and M. J. Sirgy. 2019. Work-Life Balance in the Digital Workplace: The Impact of Schedule Flexibility and Telecommuting on Work-Life Balance and Overall Life Satisfaction. In Thriving in Digital Workspaces. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Huei Ling, and Ven hwei Lo. 2018. An Integrated Model of Workload, Autonomy, Burnout, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover Intention among Taiwanese Reporters. Asian Journal of Communication 28: 153–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, Edwin A. 1970. Job Satisfaction and Job Performance: A Theoretical Analysis. Organizational Behavior & Human Performance 5: 484–500. [Google Scholar]

- López-Igual, Purificación, and Paula Rodríguez-Modroño. 2020. Who Is Teleworking and Where from? Exploring the Main Determinants of Telework in Europe. Sustainability 12: 8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, Daulatram B. 2003. Organizational Culture and Job Satisfaction. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 18: 219–36. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Brittany Harker, and Rhiannon MacDonnell. 2012. Is Telework Effective for Organizations?: A Meta-Analysis of Empirical Research on Perceptions of Telework and Organizational Outcomes. Management Research Review 35: 602–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, Charlotte K., Mareike Reimann, and Martin Diewald. 2021. Do Work–Life Measures Really Matter? The Impact of Flexible Working Hours and Home-Based Teleworking in Preventing Voluntary Employee Exits. Social Sciences 10: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakrošienė, Audronė, Ilona Bučiūnienė, and Bernadeta Goštautaitė. 2019. Working from Home: Characteristics and Outcomes of Telework. International Journal of Manpower 40: 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neirotti, Paolo, Emilio Paolucci, and Elisabetta Raguseo. 2013. Mapping the Antecedents of Telework Diffusion: Firm-Level Evidence from Italy. New Technology, Work and Employment 28: 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, Derrick J., and Yulin Fang. 2005. Individual, Social and Situational Determinants of Telecommuter Productivity. Information and Management 42: 1037–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilles, Jack M. 1997. Telework: Enabling Distributed Organizations: Implications for It Managers. Information Systems Management 14: 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novianti, Khusnul Rofida, and Kenny Roz. 2020. Teleworking and Workload Balance on Job Satisfaction: Indonesian Public Sector Workers During Covid-19 Pandemic. APMBA (Asia Pacific Management and Business Application) 1: 8997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Minjeong, and Sungyong Choi. 2020. The Competence of Project Team Members and Success Factors with Open Innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 6: 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raišiene, Agota Giedre, Violeta Rapuano, Kristina Varkulevičiute, and Katarína Stachová. 2020. Working from Home-Who Is Happy? A Survey of Lithuania’s Employees during the COVID-19 Quarantine Period. Sustainability 12: 5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roz, Kenny. 2019. Job Satisfaction as a Mediation of Transformational Leadership Style on Employee Performance in the Food Industry in Malang City. International Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting Research (IJEBAR) 3: 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieman, Scott, and Paul Glavin. 2017. Ironic Flexibility: When Normative Role Blurring Undermines the Benefits of Schedule Control. Sociological Quarterly 58: 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schriesheim, Chester, and Anne S. Tsui. 1980. Development and Validation of a Short Satisfaction Instrument for Use in Survey Feedback Interventions. Western Academy of Management Meeting 1980: 115–17. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Younghwan, and Jia Gao. 2019. Does Telework Stress Employees Out? A Study on Working at Home and Subjective Well-Being for Wage/Salary Workers. Journal of Happiness Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stewart, Wendy, and Julian Barling. 1996. Daily Work Stress, Mood and Interpersonal Job Performance: A Mediational Model. Work and Stress 10: 336–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcour, P. Monique, and Larry W. Hunter. 2017. Technology, Organizations, and Work-Life Integration. In Work and Life Integration: Organizational, Cultural, and Individual Perspectives. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- van Meel, Juriaan. 2011. The Origins of New Ways of Working: Office Concepts in the 1970s. Facilities 29: 357–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, Ronald P., Amanda J. Anderson, and Seth A. Kaplan. 2015. A Within-Person Examination of the Effects of Telework. Journal of Business and Psychology 30: 313–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virick, Meghna, Nancy DaSilva, and Kristi Arrington. 2010. Moderators of the Curvilinear Relation between Extent of Telecommuting and Job and Life Satisfaction: The Role of Performance Outcome Orientation and Worker Type. Human Relations 63: 137–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, Christina, Michaéla C. Schippers, Sebastian Stegmann, Arnold B. Bakker, Peter J. van Baalen, and Karin I. Proper. 2019. Fostering Flexibility in the New World of Work: A Model of Time-Spatial Job Crafting. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojčák, Emil, and Matúš Baráth. 2017. National Culture and Application of Telework in Europe. European Journal of Business Science and Technology 3: 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Particulars | Items | Frequency (n = 472) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 303 | 64.2% |

| Female | 169 | 35.8% | |

| Age (years) | 20–25 | 31 | 6.6% |

| 26–30 | 137 | 29% | |

| 31–35 | 95 | 20.1% | |

| 36–40 | 64 | 13.6% | |

| >41 | 145 | 30.7% | |

| Marital status | Married | 343 | 72.7% |

| Unmarried | 129 | 27.3% | |

| Education | High school | 12 | 2.5% |

| Diploma/bachelor’s | 238 | 50.4% | |

| Master’s/doctoral | 222 | 47% | |

| Tenure | 1–5 years | 167 | 35.4% |

| 6–10 years | 99 | 21% | |

| 11–15 years | 80 | 16.9% | |

| 16–20 years | 37 | 7.8% | |

| >20 years | 89 | 18.8% | |

| Current employment | Private company employees | 156 | 32.8% |

| Government employees | 288 | 61.2% | |

| Others | 28 | 6% | |

| Length doing WFH | <1 month | 74 | 15.8% |

| 1–2 month | 340 | 71.9% | |

| >2 month | 58 | 12.4% |

| Construct | Items | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work from home | WFH01 | 0.753 | 0.880 | 0.891 |

| WFH02 | 0.757 | |||

| WFH03 | 0.726 | |||

| WFH04 | 0.753 | |||

| WFH09 | 0.665 | |||

| WFH10 | 0.683 | |||

| WFH11 | 0.749 | |||

| WFH12 | 0.552 | |||

| WFH13 | 0.549 | |||

| WFH14 | 0.744 | |||

| Work–life balance | WLB01 | 0.807 | 0.920 | 0.941 |

| WLB02 | 0.813 | |||

| WLB03 | 0.834 | |||

| WLB04 | 0.778 | |||

| WLB05 | 0.840 | |||

| WLB07 | 0.769 | |||

| WLB09 | 0.766 | |||

| WLB10 | 0.772 | |||

| WLB11 | 0.718 | |||

| Work stress | WS1 | 0.806 | 0.925 | 0.903 |

| WS2 | 0.813 | |||

| WS3 | 0.867 | |||

| WS4 | 0.889 | |||

| WS5 | 0.853 | |||

| WS6 | 0.887 | |||

| Job satisfaction | JS01 | 0.835 | 0.849 | 0.937 |

| JS02 | 0.780 | |||

| JS03 | 0.758 | |||

| JS04 | 0.680 | |||

| JS05 | 0.877 |

| Variable | AVE | √AVE | Correlation Score among Latent Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WFH | WLB | WS | JS | |||

| WFH | 0.623 | 0.789 | 0.789 | −0.442 | 0.737 | −0.254 |

| WLB | 0.728 | 0.853 | 0.697 | −0.452 | 0.494 | |

| WS | 0.585 | 0.764 | 0.853 | −0.389 | ||

| JS | 0.623 | 0.789 | 0.789 | |||

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Path Coefficient | t-Value | p-Value | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | WFH → JS | 0.424 | 8.496 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H2 | WFH → WLB | −0.442 | 10.456 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H3 | WFH → WS | −0.452 | 9.642 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H4 | WLB → JS | 0.171 | 2.861 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H5 | WS → JS | −0.323 | 4.721 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H6 | WFH → WLB → JS | 0.146 | 3.926 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H7 | WFH → WS → JS | −0.075 | 2.729 | 0.000 | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Irawanto, D.W.; Novianti, K.R.; Roz, K. Work from Home: Measuring Satisfaction between Work–Life Balance and Work Stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia. Economies 2021, 9, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9030096

Irawanto DW, Novianti KR, Roz K. Work from Home: Measuring Satisfaction between Work–Life Balance and Work Stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia. Economies. 2021; 9(3):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9030096

Chicago/Turabian StyleIrawanto, Dodi Wirawan, Khusnul Rofida Novianti, and Kenny Roz. 2021. "Work from Home: Measuring Satisfaction between Work–Life Balance and Work Stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia" Economies 9, no. 3: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9030096

APA StyleIrawanto, D. W., Novianti, K. R., & Roz, K. (2021). Work from Home: Measuring Satisfaction between Work–Life Balance and Work Stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia. Economies, 9(3), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9030096