Abstract

Scholars who study compulsory voting realize their research in countries where compulsory voting already exists. On the contrary, there are not many studies that deal with ex ante analyses of the economic and political consequences of voter behavior caused by a new element in public elections—compulsory voting. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to find out what voters’ reactions will cause when compulsory voting is introduced in the Czech Republic. This paper has the ambition to contribute to the understanding of the economic and political context of sanctions for non-voters. The analysis of non-voters’ willingness to change their behavior due to the fine and the determination of the amount of this fine in the Czech Republic are the practical benefits of this study. In this way, we determine the “abstention price” of a vote. The input data of the analysis are data obtained by a questionnaire survey conducted in the Czech Republic in 2020; the target group is 807 respondents. The basic statistical operations, and binary and multinomial logistic regressions were employed in this study. The results of the research show that compulsory voting has only a minimal effect on the turnout. The introduction of compulsory voting changes the characteristics of the typical voter. Voters with lower political interest and political knowledge will take part in the elections more often. The fine that non-voters would be willing to pay is approx. 6% of their average monthly income.

1. Introduction

According to Downs (1957), political markets can be compared to economic markets in certain contexts. One of the areas in which similarity can be found is the voter/consumer’s decision-making process. The voter, like the consumer in the economic market, compares marginal benefits with marginal costs to realize a positive net benefit. In other words, the benefits realized by the choice must outweigh the costs of the choice (Volejnikova and Kuba 2020). Blais (2000) considers, for example, the time spent selecting candidates, getting acquainted with their programs, the way to the ballot boxes, etc., to be the most significant cost. The willingness to make decisions (choose/consume) depends on many factors and determinants, such as the availability of information, available resources, time, knowledge, etc. However, the question remains whether these costs can be quantified and, if so, where there is a threshold at which the costs are already so high that the voter chooses not to vote.

Economic markets can answer this question through a price market mechanism. However, in political markets, this price is not explicitly set. Therefore, this paper seeks to determine the “abstention price” using the willingness-to-pay method, which is commonly used to determine the prices of publicly provided goods and services (e.g., Guagnano et al. 1994; Green et al. 1998; Halaskova et al. 2018; Prokop and Stejskal 2020).

The “abstention price” is considered the amount of fine that the voter is willing to pay if he or she does not participate in the elections with statutory compulsory participation. The analysis uses knowledge from previous research focused on the issue of compulsory voting, which it applies to the environment of the Czech Republic. In the Czech Republic, voters currently vote in a voluntary voting system, but the issue of compulsory voting is often a publicly discussed topic due to the declining interest in elections.

The results of our research have theoretical as well as methodological contributions in the area of compulsory voting and setting the amount of fine for non-participation. In theory, the research contributes to previous assumptions that the introduction of mandatory voting will reduce the quality of election results (Dassonneville et al. 2017). The results also show that the introduction of compulsory voting will not have a significant mobilizing effect in the Czech Republic (Halaskova and Halaskova 2020). Finally, the amount of fine that people are willing to pay for non-participation is determined, which can be considered one of the ways to appreciate the vote.

2. Theoretical Background

The issue of compulsory voting (participation in public elections) has been discussed for several decades. One of the most important scholars who discussed this topic is Lijphart (1997). In his work, he postulates several reasons why it is appropriate for them to have compulsory participation in elections from time to time. One of the reasons is the fact that rational decision-making in elections requires great expertise and competence from citizens, and unequal turnout is biased towards weaker citizens. The second reason is that the influence of unequal participation in elections causes unequal political influence during the term of the winning coalition. It is possible to add that an important reason to think about compulsory voting is also the fact that voter turnout is declining in almost all democratic countries (World Bank 2017). In some types of elections, turnout is minimal, although elections result in the occupation of important chambers of parliament or regional governments (Jakee and Sun 2006). Jakee and Sun (2006) summarized this with the statement: “that turning out to vote is, after all, irrational in individual cost-benefit terms.” At the same time, they come across a well-known theorem on rational ignorance, or “zero turnout”, which consists of the fact that the voter expects that his preferred candidate will be elected. However, this expectation is completely wrong. This means that the expected economic or social benefits will not materialize, but the costs of the public election have been realized. The net marginal benefit is, therefore, negative. Despite this theorem, public choice is, in principle, the only democratic means of deciding on public affairs. Therefore, there are several studies that analyze the determinants influencing turnout.

It is necessary to understand whom the voter is and why he or she comes to vote. In this area, there are a number of political, sociological, but also economic or psychological studies explaining the factors influencing turnout. Merrifield (1993) or Geys (2006) explain the socio-economic, political, and institutional variables influencing turnout. Powell (1986) or Brown-Iannuzzi et al. (2017) focus on political attitudes. Some others supplement it with knowledge about the so-called partisanship, another major determinant of political courts and decisions. Craw (2017), Hill (2018), and Enriques and Romano (2019) are studying institutional structures affecting voter turnout. The studies show a difference between the institutional structure influencing American voters, while in individual European states, the institutional structure is rather a secondary factor.

However, many of these studies postulate the conclusion that expecting the rational behavior of the voter is only part of the theory; in practice, the voter is exposed to a large number of influences and factors that affect the voter’s behavior. It was expected that in countries with higher turnout, it would be possible to demonstrate a relationship between the socio-economic situation of individuals and turnout. However, this relationship has not been satisfactorily confirmed (Powell 1986). Powell’s study shows only the relationship between the level of education and the willingness to participate in elections. This claim is refuted by Topf (1995). Based on a study of the results of electoral behavior in European countries, he concludes that there is no significant relationship between the educational level of the cohort and the willingness to participate in elections.

Lijphart (1997) provides evidence that maximizing turnout through compulsory voting is the best option to offer (others may include the introduction of institutional mechanisms, a change in electoral rules, the introduction of weekend voting, the concurrence of multiple elections, etc.). These have been discussed in a number of studies, e.g., Powell (1980, 1986) and Franklin (1996). However, only some of them provide empirical evidence on the effectiveness of introducing compulsory voting through field experiments to examine the effects of Get-Out-The-Vote campaigns (Gerber and Green 2017). However, there are also many critics. They discuss the usability of these data in other countries and the possibility of extrapolating and estimating human behavior over longer periods (Banerjee et al. 2017).

There are currently compulsory voting laws in almost 30 countries, but only ten of them enforce the mandate to vote and punish abstention by a fine (Gonzales 2020).

Chapman (2018) recommends using compulsory voting to increase turnout. Jackman (2001) states that compulsory voting must be based on legislation that obliges citizens to vote in elections. However, this legal obligation must be accompanied by either compulsory voter registration (U.S. reality) or fines for non-compliance with this legal obligation. Jackman (2001) provides evidence that compulsory voter turnout increases turnout by up to 30% (as confirmed by a study by Bechtel et al. 2018). The same trend has been observed in Switzerland, Argentina, and Australia. Despite restrictions and fines, a large number of voters remain who do not go to the polls and prefer to pay a fine. They are mostly principled rejecters of mandatory public elections. This trend is also observed where compulsory voting has been abolished (e.g., the Netherlands in 1970). Similarly, the setting of the fine for non-voting is a determinant of turnout (according to León (2017), a 75% reduction in the fine for non-voting reduced turnout in Peru by 5.3%).

An important question that needs to be asked, based on the abovementioned, is what effect of compulsory voting on the outcome of the election, or what fine (sanction), voters are willing to bear. According to the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance Compulsory Voting (2019), sanctions for absenteeism in Austria were set at a maximum of USD 750 (2017 prices), then, if the fine was not paid, two weeks in prison. However, studies do not indicate how many fines were collected, as well as how many “excuses” were applied (illness, work, travel, urgent family matters, technical interruptions, etc.).

Funk (2007) presents a study from Switzerland, where compulsory voting was abolished and sanctions for non-voting were only symbolic. The abolition of compulsory voting significantly reduced the average turnout, and the introduction of correspondence voting (by mail) has not been shown to increase turnout. This study concludes that in areas of public interest, a non-sanctioned law aimed at civic duty may have a greater impact on behavior than measures that affect the cost of ensuring public wealth. This study provides evidence that compulsory voting leads to higher turnout even with very low fines. This conclusion is supported by other studies, such as Cepaluni and Hidalgo (2016), Hoffman et al. (2017) and Mikusova Merickova et al. (2020).

The study by Dassonneville et al. (2019) dealt with compulsory voting in Switzerland, but also in Australia, Belgium, and Brazil. They define the so-called ‘reluctant voters’ hypothesis: “Compelling voters to vote tends to weaken the impact of proximity considerations on electoral behaviour, although this effect remains limited and is only significant in half of the elections that were investigated.”

Gonzales (2020) analyzed the impact of the introduced absenteeism fee in Peru (compulsory voting since 1933). Until 2006, the fee was set in a uniform amount, and then the fees were set depending on the social status of the voter (three categories). However, other studies only provide information on the amount of the fee; there is no argument for its amount (e.g., according to Bray (2017), Australia has a USD 20 non-voting fee; in the Netherlands, this is only USD 5). Pilet (2007) informs that the amount of the fine in Belgium is between EUR 25 and 50; if the absence in the next election is repeated, the fine increases to EUR 50 to 120.

The above research pays particular attention to countries where compulsory voting has already been introduced. Political, social, but also economic impacts are assessed ex post in all mentioned studies. In some European countries, the issue of compulsory voting is discussed at the political level. This is happening, for example, in Poland or the Czech Republic. However, there are only a few studies on this topic. One of them is Czesnik (2013) who deals with the political impacts associated with compulsory voting in Poland. The results show that compulsory voting dramatically increases turnout, but only in specific social groups. However, it was concluded that, despite this fundamental change in the electoral process, the results of the elections remain unchanged.

This research builds on the original assumptions and expands the current state of knowledge of the issue of compulsory turnout by analyzing the economic and political implications arising from financial sanctions for non-voters. Not many studies examine ex ante voters’ willingness to pay a certain amount of fine. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to determine how voters’ behaviors will be changed when compulsory voting is introduced in the electoral parliamentary system in the Czech Republic. Our study will determine the amount of fine that can change the behavior of non-voters into voters.

Based on the above-mentioned findings from previous studies, three research questions are defined:

- RQ1.

- How will the introduction of compulsory voting affect voter turnout in the Czech Republic?

- RQ2.

- Will the characteristics of the voters who vote in parliamentary elections change when compulsory voting is introduced?

- RQ3.

- How high of a fine are voters willing to pay for non-voting?

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

The analysis is based on quantitative data, which were obtained by a questionnaire survey conducted in the first week of May in 2020. Data were obtained through online surveys. The creation of the questionnaire and the mediation of data collection was performed by the sociological agency, Sociores (www.sociores.cz (accessed on 19 April 2021)). A representative sample of respondents (N = 808) from the Czech National Panel (www.narodnipanel.cz (accessed on 19 April 2021)) was selected for the research. The representativeness of the sample was ensured by quotas. Before filling in the questionnaire, the respondent was asked about age, gender and educational background. If a sufficient number of answers were collected in the target group, the respondent could not fill out the questionnaire. The data collection was preceded by a pilot survey in April 2020. The obtained data were adjusted according to the usual sociological rules, and included the reduction of the set of citizens who do not have the right to vote (N = 1). The final sample examined is N = 807 respondents.

The questions in the questionnaire were created on the basis of the search for theoretical knowledge as acquired in previous research focused on voting behavior. From a large number of surveys, two basic groups of factors influencing electoral decision-making were selected:

- Socioeconomic characteristics of the voter—used, for example, in the studies of Jankowski and Strate (1995); Inglehart et al. (2003); Franko et al. (2016); Dassonneville (2017); Blais (2000);

- Political knowledge, awareness, and interest—used, for example, in the studies of Rubenson et al. (2004); Denny and Doyle (2008); Dostie-Goulet (2009); Ellingsen and Hernæs (2018).

A complete overview of the basic variables and the basic descriptive statistics are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of variables.

In addition to the above variables, the analysis also includes the variable “age squared”, which considers the relationship between turnout and the election cycle. The literature assumes that interest in elections does not increase steadily (linearly) with age. Willingness to vote only increases with age until a certain age, and then interest in elections decreases again (Wass 2007; Blais et al. 2004; Bhatti and Hansen 2012).

An important variable in the research was the willingness of voters to pay for not participating in elections. The respondent was gradually asked the following question:

- “Imagine that compulsory voting would be introduced in the Czech Republic now. This means that every citizen with the right to vote should have a statutory obligation to vote. Failure to do so could result in a financial penalty, as is the case in Belgium or Luxembourg, for example. Would you participate in the election in that case?”

If they answered, “definitely not” or “probably not”, they were asked the following question:

- “You state that when introducing compulsory voting, you would not go to the polls even though there would be a fine. How high would the financial fine have to be for you to change this decision and go to the polls instead?”

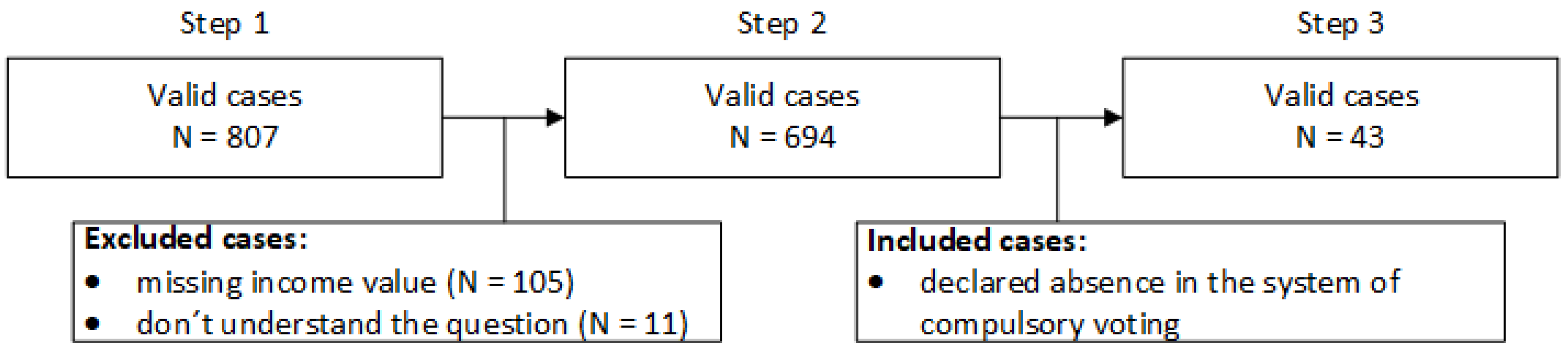

Only 43 respondents had the ability to answer this question, which is only more than 5% of the total number of respondents (N = 807). The total number of respondents entering the individual parts of the analysis is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Total number of respondents in the analysis.

We used basic statistical methods, binary and multinomial logistic regression models for the data analysis. We performed the analysis in the SPSS software. We tested the collinearity between independent variables using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for each regression model. Multicollinearity was rejected in the models (VIF < 5).

3.2. Methodology

The research methodology is based on a theoretical research. Within the analysis, it was possible to examine three areas of problems.

- Impact of compulsory voting on turnout

The aim is to determine how the willingness of voters to participate in elections would be changed if compulsory voting were introduced in the parliamentary elections in the Czech Republic. Basic statistical methods and graphical interpretations are used for this aim.

- 2.

- Differences between voters in the system of voluntary voting and in the system of compulsory voting

This part focuses on the influence of selected variables on turnout. The first step of the analysis is based on the comparison of two binominal regression models. A different dependent variable is used in each model. In Model 1, the dependent variable is “participation in the voluntary voting system” and in Model 2, the dependent variable is “participation in the compulsory voting system”. The independent variables are the same for both models. Furthermore, the analysis is supplemented by a multinomial regression analysis, which compares voters voting only in the system of voluntary voting with voters voting only in the system of compulsory voting and with non-voters. This multinomial logistic regression model differs from previous binomial regression models by input variables. Model 2 (compulsory voting) includes all voters who would participate in compulsory voting, regardless of the answer to the question of voluntary voting. In the multinomial logistic regression model, the variable “compulsory voting” includes only voters who do not want to vote voluntarily and will only vote when compulsory voting is introduced.

The aim of the analysis is to find out how the structure of voters will change when using the system of voluntary or compulsory voting in elections. This step will make it possible to define the circle of citizens who do not participate in elections in the system of compulsory voting (so-called non-voters) and determine their characteristics.

- 3.

- Willingness of non-voters to pay a real fine in the compulsory voting system

The last part of the analysis is focused on non-voters in the system of compulsory voting and analyzing the economic impact of such behavior. The aim is to find out what types of citizens refuse to vote in the compulsory voting system. Subsequently, the basic statistical methods for these groups are used to determine the amount of fine that non-voters are willing to pay for non-participation.

4. Results

4.1. Impact of Compulsory Voting on Turnout

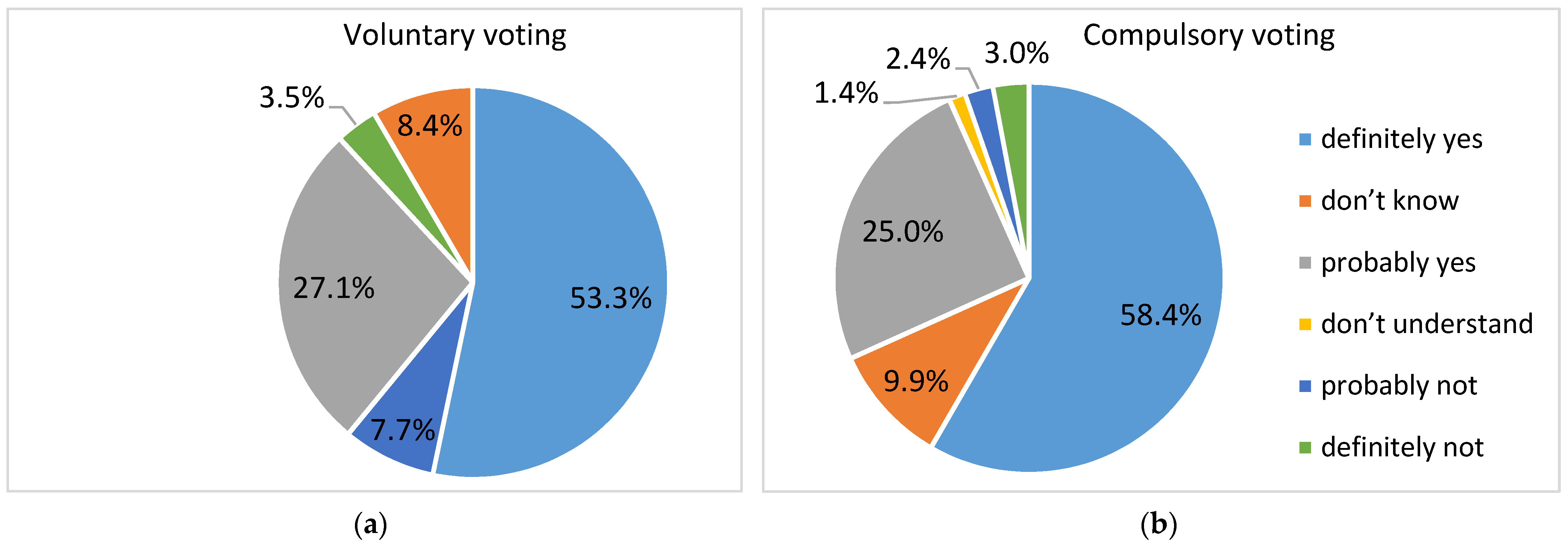

The first part of the analysis focuses on the impact of the introduction of compulsory voting. Figure 2 presents the change in turnout.

Figure 2.

You would be willing to take part in the next parliamentary elections when voluntary (a) compulsory (b) participation is introduced?

We are aware that questions about turnout/non-turnout also have social, psychological, and ethical consequences. In practice, it is not possible to distinguish between the answers of those who believe they will go to the polls and those who feel that it is bad to go to the polls (“bad behavior”) and therefore declare it without being sure that they will go to the polls. We also noticed this phenomenon in our research because the declared turnout differs from the actual turnout. However, we believe that this phenomenon appears in most studies, because it is not possible to assess the veracity of the respondent’s statement.

According to the results, the declared turnout in the voluntary voting system is 80.4% (sum of answers “definitely yes” and “rather yes”). This is a much higher turnout than the actual turnout in the last parliamentary elections in 2017 (60.8%). When the government makes a decision about compulsory voting (and sets a sanction in the form of a fine for non-participation), respondents said their turnout would increase to 83.4%. It follows from this first finding that the introduction of compulsory voting will not substantially increase the interest in participating in elections, so it is a relatively ineffective tool. The change of the declared participation with the introduction of compulsory voting is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Change of voter turnout with the introduction of compulsory voting.

Table 2 shows that 91 non-voters (or not decided) declare participation in the event of the introduction of compulsory voting. Contrastingly, 60 voters who plan to participate in the elections voluntarily are thus reluctant (or not decided) to vote should compulsory voting be introduced. This result suggests that the introduction of compulsory voting may not have a significant positive impact on increasing turnout. It also supports the assumption that if elections are interesting to voters, voluntary turnout can be high.

4.2. Differences between Voters in the System of Voluntary Voting and in the System of Compulsory Voting

Table 3 shows the influence of selected determinants (independent variables) from the areas of socio-economic characteristics (age, education, sex, etc.) and political knowledge (information, interest in politics, etc.) on the voters’ willingness to participate in elections. Two own research models are compared in which there are different dependent variables (Model 1: voter participation in the voluntary voting system; Model 2: voter participation in the compulsory voting system).

Table 3.

Influence of individual determinants on the system of voting.

Table 3 presents the results of the two models, which express the change in the characteristics of voters with the introduction of compulsory voting.

The variables “age” and “age squared” indicate the existence of a relationship between voter life cycle and turnout. A positive coefficient beta of variable “age squared” and a negative coefficient beta of variable “age squared” express the lower turnout in middle-aged voters. Contrastingly, young and older people are interested in voting. This applies to both models.

Model 2 shows that education is a significant variable for compulsory turnout. Voters with lower education are less willing to go to the polls in general. This is confirmed by the results of research. With mandatory participation in elections, the participation of this group of voters will be even lower.

The determinants of “sex” and “income” were not found to be significantly related to voter turnout. The results confirm that the environment from which they come also has a significant effect on voter behavior: for voters from rural areas, turnout will be reduced if compulsory voting is introduced.

The voter’s interest in going to the polls is also determined by political experience, previous experience with elections (so-called political knowledge). Having enough information about elections, political parties, coalitions, etc., has a strong influence on voter behavior. The voter who voted in the previous election is more likely to vote in the next election. This thesis is valid in both systems of elections. In the system of voluntary voter turnout, the variable “Difference in programs” is significant. People with political knowledge and the ability to distinguish political parties are motivated to vote. With the introduction of compulsory voting, political knowledge ceases to be significant.

Information asymmetry has a major impact on voter behavior. Information from pre-election surveys has a significant impact on voter decision-making in both systems. The level of quality and availability of political information has a significant impact on turnout, especially in the voluntary voting system. Watching public television and watching political content on social networks motivates voters to vote. Conversely, with the introduction of voluntary voting, less or poorly informed people will also take part in elections. Table 4 shows the characteristics of voters voting only voluntarily, voters voting only in the compulsory voting system, and non-voters in both systems.

Table 4.

Differences between voluntary voters, voters voting only in the system of compulsory elections, and non-voters answers.

The reference group of voters in the model is voluntary voters. The results show the following:

- Comparison of characteristics of voters voting voluntarily and voting only in the system of compulsory voting (“Compulsory voting” model);

- Comparison of the characteristics of voters who vote only voluntarily and non-voters who refuse to vote even with the introduction of compulsory voting (“Non-voters” model).

It is clear from the results that voters voting only in the system of compulsory voting and non-voters have similar characteristics. They differ from each other mainly by the significance of individual variables. It is clear that voters who vote only in the compulsory voting system or do not vote are middle-aged people. Furthermore, these people are not regular voters and do not have political knowledge (they do not recognize differences in programs, and they do not watch pre-election surveys) and they do not have quality political information (they do not watch public TV or social networks). If we are to look for reasons that motivate non-voters to abstain even though they face a fine, we need to focus on other factors that are not included in our analysis.

4.3. Willingness of Non-Voters to Pay a Real Fine in the Compulsory Voting System

The previous part of the research defined people who will not respect the law (when compulsory voting is enacted) under the threat of a fine. The following results focus only on this special focus group.

Based on the results of the research (Models 1 and 2), it is possible to state the characteristics of persons—non-voters as follows:

- Middle aged;

- Living in rural areas;

- Less educated;

- Low interest in politics (or insufficient or poor-quality information about politics).

Voters who declared participation in the case of the introduction of compulsory voting were removed from the data. The remaining approximately 16% was divided into those who indicated that they were considering participating but not definitively decided (80) and the remaining 43 respondents answered this question:

“You state that when introducing compulsory voting, you would not go to the polls even though there would be a fine. How high would the financial fine have to be for you to change this decision and go to the polls instead?”

Some voters have expressed protest at the introduction of compulsory voting. There are answers: the state cannot impose fines for non-participation; fines do not make sense; compulsory voting is the end of freedom; absence is also an opinion. The description of the distribution of the values of fines filled in by the respondents in the questionnaire is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Description of the distribution of the values.

After excluding extreme meaningless values and missing values (values out of the range (0, 100,000), 30 responses were included in the analysis. A value of “0” is considered a missing value because this voter would take part in the mandatory vote (he or she is not willing to pay for not voting). Values above 100,000 were reported by only 2 respondents. These values are several times higher compared to the average wage (38,525 CZK). We therefore consider them extremely meaningless. Basic descriptive statistics are given in Table 6.

Table 6.

Amount of fine (CZK) for non-voting.

The average value of the fine that voters are willing to pay for non-participation is CZK 18,614. The amount thus absolutely determined is not sufficiently informative. However, the median level already provides some real information. The amount of the fine, which would have to be enacted for not participating in the elections, would have to be around CZK 2000 in the Czech Republic. This value is approximately 6% of the average income valid in the Czech Republic for 2020. The ratio of the level of the fine to the non-voter’s income is shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Amount of fine (percentage of wages) for non-voting.

This conclusion is also confirmed by the results, which determined that the amount of the acceptable fine should not exceed 20% of the voter’s income. For policymakers, however, this information is important. If the fine is to act preventively and force voters to behave in a certain way, it must be set as a percentage of the voter’s income and be higher than 20%.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The issue of compulsory voting in public elections is not one of those most frequently realized by research teams. This is the case even though various politicians in many countries are discussing this possibility as a suitable way to increase turnout in parliamentary elections. However, other options and evidence on the effectiveness of this tool are not discussed in this public debate.

The results of this preliminary case study in the Czech Republic, which are presented in this paper, clearly show that the introduction of compulsory voting changes the behavior of voters and leads to a slight increase in turnout. However, this restrictive regulatory tool also changes the character of voters—i.e., voters with lower education from the rural environment, who do not have sufficient information about political parties, will more often go to the polls. For other voters, it is possible to observe a rejection of the reaction to this “hard” tool. Many voters declare their disapproval by demonstrative non-voting in future elections. Research into the amount of the fine has shown that a fine of more than CZK 2000 (EUR 1 = approx. CSK 26, average wage = CZK 38,525) could change the status of many voters from non-voter to voter.

The presented results are not in full agreement with the study conducted in Poland (Czesnik 2013). Although the Czech Republic is a neighbor of Poland, the voters’ behavior is different. The introduction of compulsory voting in the Czech Republic would not have such a high effect on turnout (RQ1), as was recorded in Poland. Regarding the characteristics of voters, these results confirm that the socio-economic characteristics of voters influence the voters’ willingness to vote in elections (RQ2). In both countries, the level of education level is an important predictor of the compulsory voting system. However, this contradicts the research of Quintelier et al. (2011), which focused on compulsory voting across 36 countries and did not prove education level as a significant predictor. Higher interest in elections for voters with a high level of education (in the system of compulsory voting) can be justified by higher social capital and the fact that they see the importance of the need to comply with social and legal norms.

In addition to education level, it is necessary to draw attention to the significant influence of the environment in which the voter lives. Our analysis shows that the non-voters often come from rural areas. The difference in results between Poland and the Czech Republic can also be observed in the variable gender of the voter, which is not significant in the Czech Republic. The fundamental difference between the voters of both systems is individual political interest and asymmetry of information. The introduction of compulsory voting will increase participation, especially for citizens who often do not have political knowledge and sufficient information to make competent decisions. This may ultimately change the results of the election. Other researched variables are not significant in the compulsory voting system; the results prove that compulsory voting would eliminate the problems associated with intergenerational differences (age and income inequality).

The contribution of the last part of the analysis is the extension of the original literature on tools to increase voter turnout. This part deals with the penalty (fine) that the voter is willing to face for non-voting. The results show that the median value of the fine is CZK 2000. This is approximately 6% of the gross monthly average income of a Czech worker (RQ3). It should be added to the consideration that if nonvoters save money on transportation and not missing work, then perhaps this price is not so high. Strictly rational people can make this consideration, and if they find that the cost of voting is higher than the potential benefit, they choose “non-vote”. This reasoning occurs in the issue of rational choice (rational ignorance) in the theory of public economics. We consider this to be a proposal for future research. The President of the Republic, who is a supporter of compulsory voting, thus proposes a significantly higher fine at the level of CZK 5000 (Novinky 2013), although there is no broader political agreement on the introduction of compulsory voting. It can be argued that such a high fine can change the behavior of non-voters.

The final results show that the introduction of compulsory voting with the threat of a fine will change voters’ behavior not only positively but also negatively (for example, by “protest” behavior).

This supports the conclusions about the possible negative effects of compulsory voting (Uggla 2008; Kouba and Lysek 2016; Singh 2019).

6. Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the low number of respondents who responded to the question of the amount of the fine for non-voting. Answering the question was accessible only to respondents who stated in the questionnaire that they would not participate in the compulsory voting in the next election. The significant reluctance of respondents to answer (for example, about the amount of their monthly income) can also be considered limiting. It should be noted that the data were collected in May 2020, i.e., during the COVID-19 pandemic situation, and the respondents may have been affected by the extraordinary life situation. To some extent, the declared voluntary participation, which amounts to more than 80%, may also be related to this. This is almost 20% more than how much participation in the last decade has fluctuated. At the time the data were collected, there was above average trust in government in society.

7. Future Research

Despite considerable limitations, we consider our research to be the first step in further analyzing the impact of the introduction of compulsory voting and the “valuation” of individual votes. However, in addition to the Czech Republic, it is necessary to focus on other countries where compulsory voting is not applied, but its introduction is the subject of public discussion. These are, for example, other CEE countries (Slovakia, Hungary), where no attention is paid to this issue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.K. and J.S.; methodology, O.K.; software, O.K.; validation, O.K.; resources, J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, O.K.; writing—review and editing, J.S.; visualization, O.K.; supervision, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by a grant no. SGS_2021_022 provided by University of Pardubice—Student Grant Agency in 2021.

Data Availability Statement

The study did not report any data.

Acknowledgments

Authors greatly appreciate reviewers’ efforts to improve this paper with comments and suggestions for improvement. The current form of the paper is much better than the original. We really appreciate the work of anonymous reviewers and thank them for it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Banerjee, Abhijit, Rukmini Banerji, James Berry, Esther Duflo, Harini Kannan, Shobhini Mukerji, Marc Shotland, and Michael Walton. 2017. From Proof Of Concept To Scalable Policies: Challenges And Solutions, With An Application. Journal of Economic Perspectives 31: 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtel, Michael M., Dominik Hangartner, and Lukas Schmid. 2018. Compulsory Voting, Habit Formation, and Political Participation. The Review of Economics and Statistics 100: 467–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, Yosef, and Kasper M. Hansen. 2012. The Effect of Generation and Age on Turnout to the European Parliament—How Turnout Will Continue to Decline in the Future. Electoral Studies 31: 262–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, André. 2000. To Vote or Not to Vote?: The Merits and Limits of Rational Choice Theory: The Merits and Limits of Rational Choice Theory. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Blais, André, Elisabeth Gidengil, and Neil Nevitte. 2004. Where Does Turnout Decline Come from? European Journal of Political Research 43: 221–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, Hubert. 2017. The Cases for and against Compulsory Voting: Defining and Defending Its Democratic Ideals. Available online: http://www.professorbray.net/Teaching/49s/StudentSurveys/Fall2017/SMM_Paper2_CompulsoryVoting.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Brown-Iannuzzi, Jazmin L., Kristjen B. Lundberg, and Stephanie McKee. 2017. The Politics Of Socioeconomic Status: How Socioeconomic Status May Influence Political Attitudes and Engagement. Current Opinion in Psychology 18: 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cepaluni, Gabriel, and Daniel F. Hidalgo. 2016. Compulsory Voting Can Increase Political Inequality: Evidence from Brazil: Evidence from Brazil. Political Analysis 24: 273–80. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26350000 (accessed on 19 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- Chapman, Emilee Booth. 2018. The Distinctive Value of Elections and the Case for Compulsory Voting. American Journal of Political Science 63: 101–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craw, Michael. 2017. Institutional Analysis of Neighborhood Collective Action. Public Administration Review 77: 707–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czesnik, Mikolaj. 2013. Is Compulsory Voting A Remedy? Evidence from the 2001 Polish Parliamentary Elections. East European Politics 29: 499–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassonneville, Ruth. 2017. Age and Voting. In The SAGE Handbook of Electoral Behaviour. Edited by Kai Arzheimer, Jocelyn Evans and Michael S. Lewis-Beck. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Dassonneville, Ruth, Marc Hooghe, and Peter Miller. 2017. The Impact of Compulsory Voting on Inequality and the Quality of the Vote. West European Politics 40: 621–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassonneville, Ruth, Fernando Feitosa, Marc Hooghe, Richard R. Lau, and Dieter Stiers. 2019. Compulsory Voting Rules, Reluctant Voters and Ideological Proximity Voting. Political Behavior 41: 209–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, Kevin, and Orla Doyle. 2008. Political Interest, Cognitive Ability and Personality: Determinants of Voter Turnout in Britain. British Journal of Political Science 38: 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostie-Goulet, Eugénie. 2009. Social Networks and the Development of Political Interest. Journal of Youth Studies 12: 405–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, Anthony. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper & Bros. [Google Scholar]

- Ellingsen, Sebastian, and Øystein Hernæs. 2018. The Impact of Commercial Television on Turnout and Public Policy: Evidence From Norwegian Local Politics. Journal of Public Economics 159: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriques, Luca, and Alessandro Romano. 2019. Institutional Investor Voting Behavior: A Network Theory Perspective. Law Working Paper N° 393/2018. Brussels: ECGI. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, Mark N. 1996. Electoral Participation. In Comparing Democracies: Elections and Voting in Global Perspective. Edited by Laurence LeDuc, Richard G. Niemi and Pippa Norris. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Franko, William W., Nathan J. Kelly, and Christopher Witko. 2016. Class Bias in Voter Turnout, Representation, and Income Inequality. Perspectives on Politics 14: 351–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, Patricia. 2007. Is There an Expressive Function Of Law? An Empirical Analysis of Voting Laws with Symbolic Fines. American Law and Economics Review 9: 135–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, Alan S., and Donald P. Green. 2017. Field Experiments on Voter Mobilization: An Overview of a Burgeoning Literature. In Handbook of Field Experiments. Edited by Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee. Amsterdam: North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Geys, Benny. 2006. Explaining Voter Turnout: A Review of Aggregate-Level Research. Electoral Studies 25: 637–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, L. Martinez. 2020. Voters’ Sophisticated Response to Abstention Fines. Depression. Available online: https://european.economicblogs.org/voxeu/2019/le%C3%B3n-ciliotta-martinez-voters-response-abstention-fines (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Green, Donald, Karen E. Jacowitz, Daniel Kahneman, and Daniel McFadden. 1998. Referendum Contingent Valuation, Anchoring, And Willingness To Pay For Public Goods. Resource and Energy Economics 20: 85–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagnano, A. Gregory, Thomas Dietz, and Paul C. Stern. 1994. Willingness to Pay for Public Goods: A Test of The Contribution Model. Psychological Science 5: 411–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halaskova, Martina, Renata Halaskova, and Viktor Prokop. 2018. Evaluation of efficiency in selected areas of public services in European Union countries. Sustainability 10: 4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halaskova, Martina, and Renata Halaskova. 2020. Evaluation of indicators of public administration in EU countries by use of multidimensional analysis. Scientific Papers of the University of Pardubice, Series D: Faculty of Economics and Administration 28: 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, David. 2018. American Voter Turnout: An Institutional Perspective. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, Mitchell, Gianmarco León, and María Lombardi. 2017. Compulsory Voting, Turnout, and Government Spending: Evidence from Austria. Journal of Public Economics 145: 103–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Ronald, Pippa Norris, and Inglehart Ronald. 2003. Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change around the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance Compulsory Voting. 2019. Available online: https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/voter-turnout/compulsory-voting (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Jackman, Simon. 2001. Compulsory Voting. In International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Edited by Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Jakee, Keith, and Guang-Zhen Sun. 2006. Is Compulsory Voting More Democratic? Public Choice 129: 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, Thomas B., and John M. Strate. 1995. Modes of Participation over the Adult Life Span. Political Behavior 17: 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouba, Karel, and Jakub Lysek. 2016. Institutional determinants of invalid voting in post-communist Europe and Latin America. Electoral Studies 41: 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, Gianmarco. 2017. Turnout, Political Preferences and Information: Experimental Evidence from Peru. Journal of Development Economics 127: 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijphart, Arend. 1997. Unequal Participation: Democracy’s Unresolved Dilemma Presidential Address, American Political Science Association, 1996. American Political Science Review 91: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrifield, John. 1993. The Institutional and Political Factors That Influence Voter Turnout. Public Choice 77: 657–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikusova Merickova, Beata, Marketa Sumpikova, Nikoleta Jakus Muthova, and Juraj Nemec. 2020. Contracting and Outsourcing in Public Sector in the Czech Republic. Scientific Papers of the University of Pardubice, Series D: Faculty of Economics and Administration 28: 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novinky. 2013. Zeman Chce Prosadit Volební Povinnost Sankcemi, Uvažuje o Pokutě 5000 Korun. Available online: https://www.novinky.cz/domaci/clanek/zeman-chce-prosadit-volebni-povinnost-sankcemi-uvazuje-o-pokute-5000-korun-179295 (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Pilet, Jean-Benoit. 2007. Choosing Compulsory Voting In Belgium: Strategy and Ideas Combined. Paper Presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions Workshop “Compulsory Voting: Principles and Practice”, Helsinki, Finland, May 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, G. Bingham. 1980. Voting Turnout in Thirty Democracies: Partisan. Legal, and Socio- Economic Influences. In Electoral Participation: A Comparative Analysis. Edited by Rose Richard. Beverly Hills: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, G. Bingham. 1986. American Voter Turnout In: Comparative Perspective. American Political Science Review 80: 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, Viktor, and Jan Stejskal. 2020. Cross-Generation Analysis of E-Book Consumers’ Preferences—A Prerequisite for Effective Management of Public Library. Information 11: 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintelier, Ellen, Marc Hooghe, and Sofie Marien. 2011. The Effect of Compulsory Voting On Turnout Stratification Patterns: A Cross-National Analysis. International Political Science Review 32: 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenson, Daniel, André Blais, Patrick Fournier, Elisabeth Gidengil, and Neil Nevitte. 2004. Accounting for the Age Gap in Turnout. Acta Politica 39: 407–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Shane P. 2019. Politically unengaged, distrusting, and disaffected individuals drive the link between compulsory voting and invalid balloting. Political Science Research and Methods 7: 107–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topf, Richard. 1995. Electoral Participation. In Citizens and the State. Edited by Hans-Dieter Klingemann and Dieter Fuchs. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Uggla, Fredrik. 2008. Incompetence, Alienation, or Calculation? Explaining Levels of Invalid Ballots and Extra-Parliamentary Votes. Comparative Political Studies 41: 1141–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volejnikova, Jolana, and Ondrej Kuba. 2020. An Economic Analysis of Public Choice: Theoretical Methodological Interconnections. Scientific Papers of the University of Pardubice, Series D: Faculty of Economics and Administration 28: 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wass, Hanna. 2007. The Effects of Age, Generation and Period on Turnout in Finland 1975–2003. Electoral Studies 26: 648–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2017. World Development Report 2017: Governance and the Law. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).