Competitive Factors of Fashion Retail Sector with Special Focus on SMEs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Competitiveness

2.2. Characteristics and Competitive Factors of Fashion Retail Sector

- Trade margins have a significant impact at both micro and macro levels, affecting inflation, companies “sensitivity to macroeconomic variables, companies’ innovation activity, investments and potential economic growth (Haldane 2018; Hambur and La Cava 2018).

- Retailers typically rent out their stores. The location of the store is probably the most important and costly decision a retailer must make in order to achieve long-term success (Öner 2014). The rent structure depends on the retailer’s and the owner’s attitude to risk and expectations about the future economic situation (Brueckner 1993).

- Numerous studies have shown that goodwill included in intangible assets has a positive effect on corporate performance and value (Kliestik et al. 2018; Rodov and Leliaert 2002; Satt 2016; Ocak and Findik 2019).

- The correlation between company size and profitability has been examined several times by researchers, but with different results (Doğan 2013; Lee 2009; Niresh and Velnampy 2014). Based on Doğan’s literature research, the vast majority of researchers found a positive correlation between firm size and profitability (Hall and Weiss 1967; Saliha and Abdessatar 2011), and a smaller proportion of researches found negative correlation or no correlation between the two factors at all (Whittington 1980; Banchuenvijit 2012).

- Studying internal factors, it is important to notice that each company has the interest to sell as many products as possible at the highest possible price. In order to do achieve this goal, they need to have as many customers as possible who come back to their stores more than once and repeat the purchase more than once. In the recent period, marketing principles have undergone many changes and as a result, the focus has shifted to customer needs and consumer expectations (Kumar et al. 2012; Ismail et al. 2015; Andersen et al. 2020). Environmental factors, for example, can significantly increase consumer satisfaction through a calm, anxiety-free atmosphere that also helps build a relaxed relationship with sellers, while increasing sales (Hosseini and Jayashree 2014).

- Several authors have confirmed that sellers can have a significant impact on customers because they reflect corporate core values and the company back in their work, they affect the company’s image, market share and profit (Meyer et al. 2016; Bamfo et al. 2018). Nevertheless, MacGregor et al. (2020) found significant differences between the attitudes of owners/senior managers and low-level management to marketing, innovations within CSR activity.

- Consumer satisfaction is one of the most important tools for a successful business. Pakurár et al. (2019) analyzed the effect of service quality dimensions on customer satisfaction in bank industry and they found that employee competences are among the most important issues. Achieving consumer satisfaction and loyalty is a basic element of corporate strategy, a tool of gaining a competitive advantage (Kenesei 2017). Consumer loyalty is a kind of barometer that predicts future customer behavior (Hill et al. 2007; Zineldin et al. 2014).

- In addition to increasing competition and the development of digitalization (Gazzola et al. 2020), consumer awareness has also strengthened and created a situation in which product quality and optimized pricing are no longer enough for long-term success. Companies can already build their success on long-term customer relationships. Many studies demonstrate that acquiring a new customer costs up to six to eight times more than retaining a customer (Rosenberg and Czepiel 1984; Matzler and Hinterhuber 1998), hence, researches places more emphasis on retaining customers than acquiring new ones.

2.3. Related Empirical Studies Using SEM Model

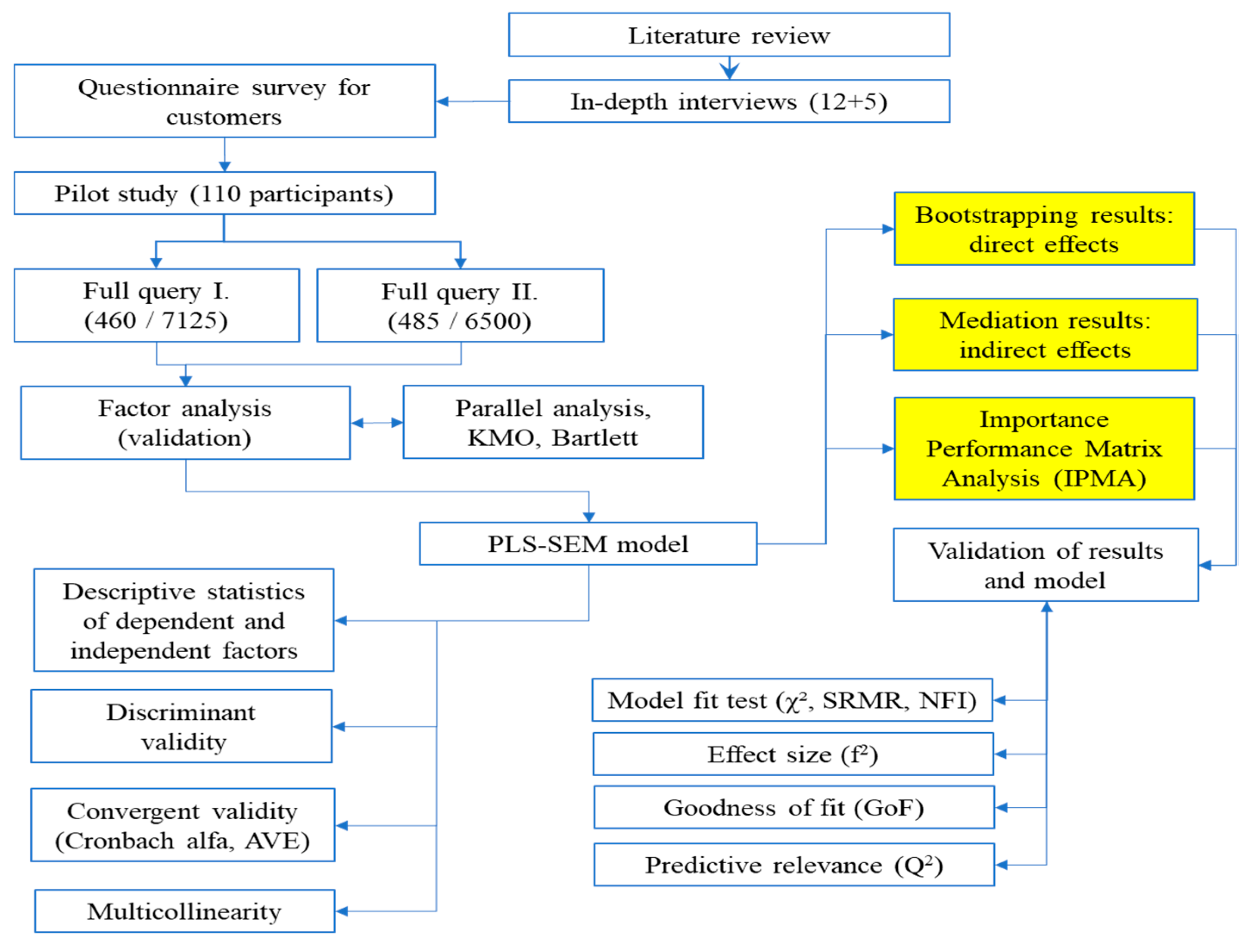

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

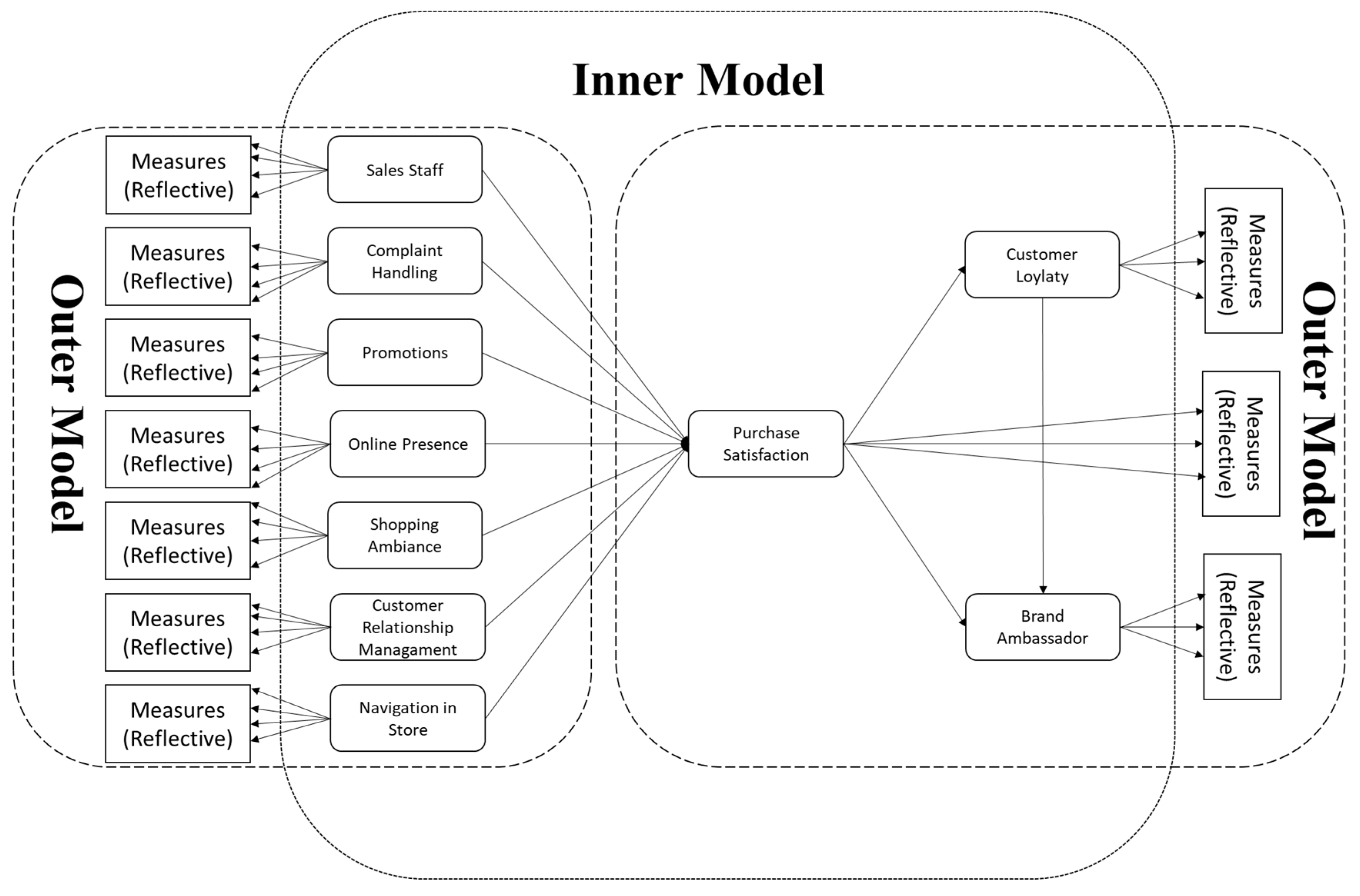

4.2. Factors and Indicators in the Model

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.4. PLS-SEM Test Results

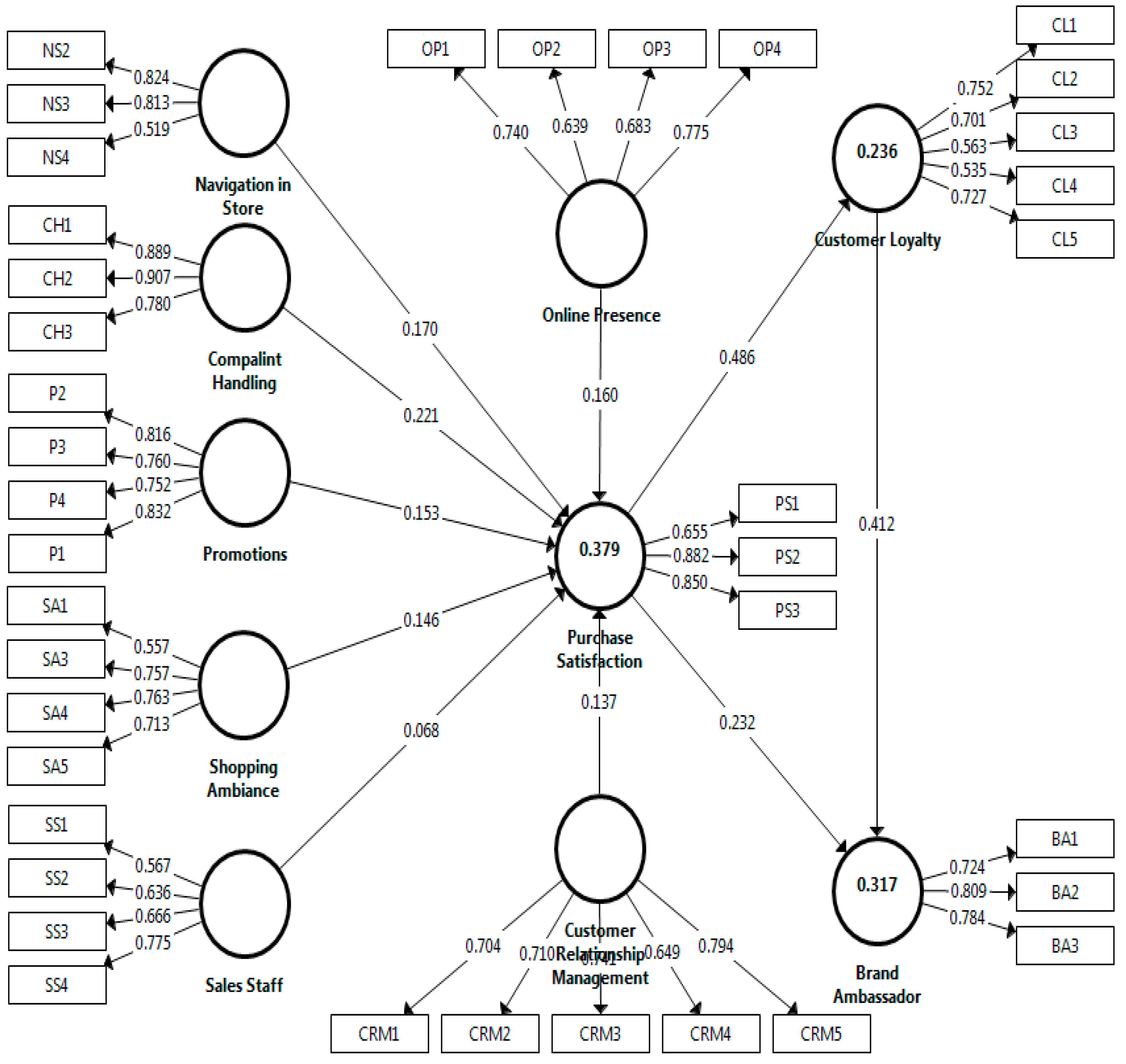

4.4.1. Assessment of Outer (Measurement) Model

4.4.2. Assessment of Inner (Structural) Model

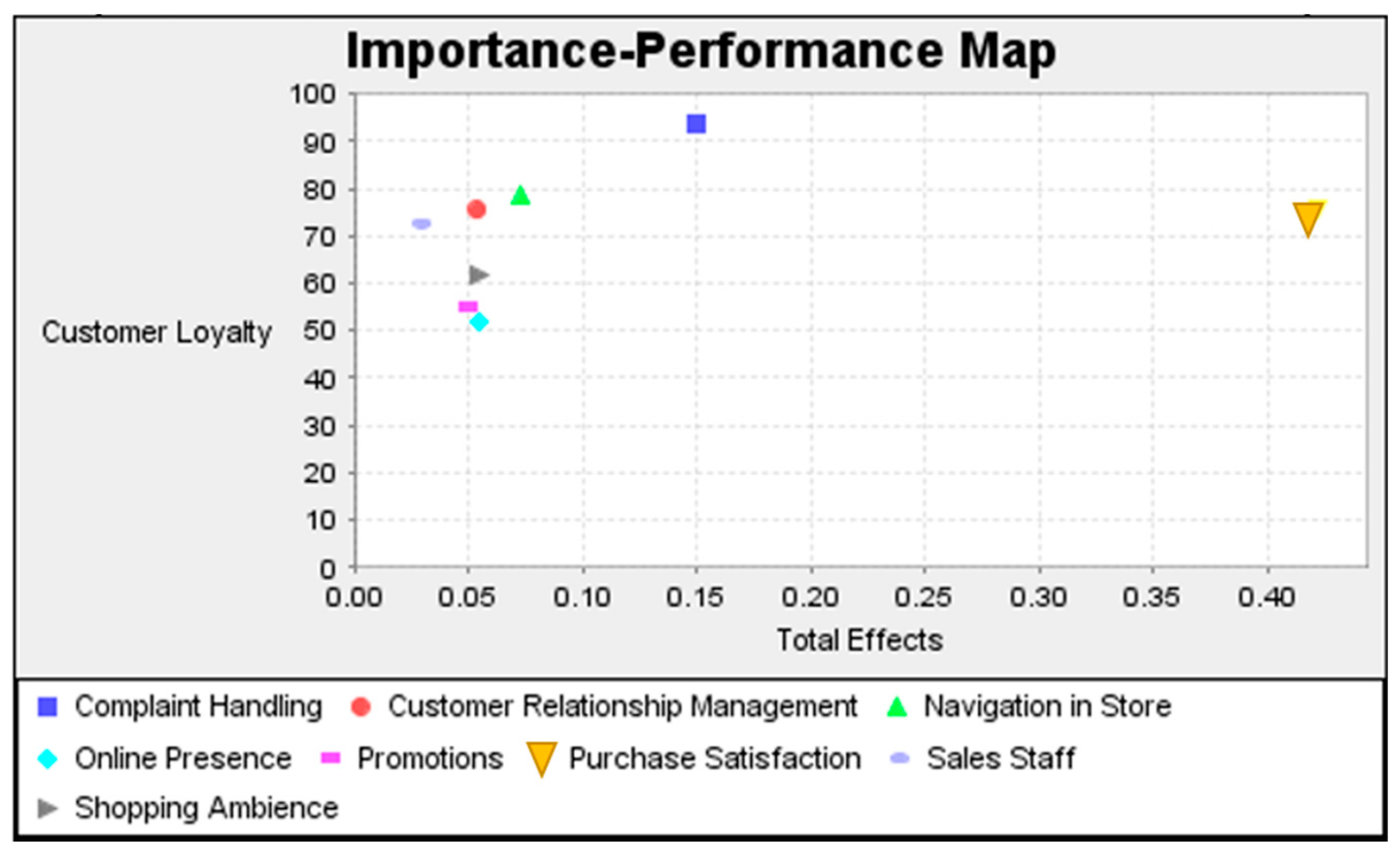

- In terms of the development of customer loyalty, sales staff do not have much role in addition to a general routine. However, in a situation where a customer complaint arises for some reason, it becomes critical how the company and sales staff handle the situation. If communication, staff behavior, possible compensation or other action in the complaint handling process is inadequate, the customer’s loyalty to the brand/store can be greatly diminished. Similarly, if the complaint is handled beyond the consumer expectations, the loyalty can increase.

- The education or training of sales staff and store managers should focus on customer complaint handling. It is not enough to educate and train the store manager on proper complaint handling, it is also useful to involve all the sales staff working there in such training. It may be necessary to check the level of practical knowledge at regular intervals through online tests or situational exercises with a mystery shopper. It may be also worth changing the company’s policy on what can be accepted as a legitimate complaint in unclear cases. Similarly, it may be worth increasing the limit as long as a complaint is considered legitimate and a refund or product exchange is offered. In order to exceed consumer expectations, some basic compensation (gift, coupon, discount) may also be considered in each case of a complaint.

4.4.3. Examining Indirect Effects—Mediation Analysis

4.4.4. Importance Performance Matrix Analysis (IPMA)

4.4.5. Validation of Structural Model

4.5. Analysis of Retailers’ Practices

4.6. Limitations and Agenda for Future Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akimova, Irina. 2000. Development of Market Orientation and Competitiveness of Ukrainian Firms. European Journal of Marketing 34: 1128–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, Peter, Fei L. Weisstein, and Song Lei. 2020. Consumer response to marketing channels: A demand-based approach. Journal of Marketing Channels. 26: 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamfo, Bylon ABeeku, Courage Simon Kofi Dogbe, and Harry Mingle. 2018. Abusive customer behaviour and frontline employee turnover intentions in the banking industry: The mediating role of employee satisfaction. Cogent Business and Management 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchuenvijit, Wanrapee. 2012. Determinants of Firm Performance of Vietnam Listed Companies; Cambridge: Academic and Business Research Institute. Available online: http://aabri.com/SA12Manuscripts/SA12078.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2019).

- Barakonyi, Károly. 2000. Strategic Management. Budapest: Nemzeti Tankönyvkiadó Rt. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Barney, Jay, Mike Wright, and David J. Ketchen. 2001. The Resource-Based View of the Firm: Ten Years after 1991. Journal of Management 27: 625–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertola, Paola, and Jose Teunissen. 2018. Fashion 4.0. Innovating Fashion Industry trough Digital Transformation. RJTA. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/RJTA-03-2018-0023/full/html (accessed on 2 October 2019).

- Brueckner, Jan K. 1993. Inter Store Externalities and Space Allocation in Shopping Centers. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 7: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttle, Francis, and Jamie Burton. 2002. Does service failure influence customer loyalty? Journal of Consumer Behaviour 1: 217–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachero-Martínez, Silvia, and Rodolfo Vázquez-Casielles. 2018. Developing the Marketing Experience to Increase Shopping Time: The Moderating Effect of Visit Frequency. Administrative Sciences 8: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Injazz J., and Karen Popovich. 2003. Understanding customer relationship management (CRM): People, process, technology. Business Process Management Journal 9: 672–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csallner, András Erik. 2015. Introduction to the Use of the SPSS Statistical Software Package. Notes. (In Hungarian) Szeged. Available online: https://docplayer.hu/19541693-Bevezetes-az-spss-statisztikaiprogramcsomag-hasznalataba.html (accessed on 17 September 2018).

- Csath, Magdolna, Csaba Fási, Balázs Nagy, Nóra Pálfi, Balázs Taksás, and Szergej Vinogradov. 2018. The role of knowledge and value intangibles in the age of great changes: The case of Hungary in international comparison. KÖZ-GAZDASÁG 3: 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Csath, Magdolna. 2019. Soft factors of competitiveness—Theoretical background (in Hungarian). In Csath, Magdolna; Taksás, Balázs; Nagy, Balázs; Vinogradov, Szergej; Pálfi, Nóra; Fási, Csaba—Csath, Magdolna (szerk.) A Versenyképesség-Mérés Változásai és új Irányai. Budapest: Dialóg Campus Kiadó-Nordex Kft, pp. 13–50. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos, Adamantios, and Judy A. Siguaw. 2006. Formative versus Reflective Indicators in Organizational Measure Development: A Comparison and Empirical Illustration. British Journal of Management 17: 263–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, Mesut. 2013. Does Firm Size Affect the Firm Profitability? Evidence from Turkey Mesut Doğanx Does Firm Size Affect the Firm Profitability? Turkey Research Journal of Finance and Accounting 4. ISSN 2222-1697, ISSN 2222-2847. Available online: www.iiste.org (accessed on 25 November 2019).

- Edmonds, Timothy. 2000. Regional Competitiveness and the Role of the Knowledge Economy. House of Commons Library, Research Paper 00/73. Available online: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/rp00-73/ (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- European Parliament. 2020. Small and Medium Sized Enterprises. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/63/a-kis-es-kozepvallalkozasok (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Lacker. 1981. Evaluating Structural Equation models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, Patrizia, Enrica Pavione, Roberta Pezzetti, and Daniele Grechi. 2020. Trends in the Fashion Industry. The Perception of Sustainability and Circular Economy: A Gender/Generation Quantitative Approach. Sustainability 12: 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, Gary, and Karina Fernandez-Stark. 2011. Global Value Chain Analysis: A Primer. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Karina_FernandezStark/publication/265892395_Global_Value_Chain_Analysis_A_Primer/links/54218b00 0cf274a67fea984b.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2016).

- Giovanis, Apostolos N., and Pinelopi Athanasopoulou. 2016. Drivers of customer loyalty in fast fashion retailing: Do they vary across customers? Paper presented at 9th Annual Conference of the Euromed Academy of Business, Warsaw, Poland, September 14–16; pp. 863–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, Noor, Nadia Aslam, and Amir Gulzar. 2019. Sustainable Service Quality and Customer Loyalty: The Role of Customer Satisfaction and Switching Costs in the Pakistan Cellphone Industry. Sustainability 11: 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Christian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2011. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 19: 139–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Tomas M. Hult, Christian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2014. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). European Business Review, 106–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Tomas M. Hult, Christian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2016. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Newbury Park: Kennesaw State University. [Google Scholar]

- Haldane, Andrew G. 2018. Market Power and Monetary Policy, Speech at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Policy Symposium, Jackson Hole, Wyoming. August 24. Available online: https://www.bis.org/review/r180829a.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- Hall, Marshall, and Leonard Weiss. 1967. Firm Size and Profitability. Review of Economics and Statistics 49: 319–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambur, Jonathan, and Gianni La Cava. 2018. Business Concentration and Mark-ups in the Retail Trade Sector. Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Nigel, Greg Roche, and Rachel Allen. 2007. Customer Satisfaction: The Customer Experience through the Customer’s Eyes. London: Cogent Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, Zohre, and Sreeenivasan Jayashree. 2014. Influence of the store ambiance on customers’ behavior-apparel stores in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Management 9: 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R. Duane, and Michael A. Hitt. 1999. Achieving and maintaining strategic competitiveness in the 21 st century: The role of strategic leadership. Academy of Management Perspectives 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Isma Suhaila, Azim Azmi Naem Farveez, Robert Jeyakumar Nathan, and Masyitah Mahadi. 2015. Parents’ Purchase Behaviour and Buying Decision on Luxury Branded Children’s Clothing. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 9: 87–92. Available online: http://www.ajbasweb.com/old/ajbas/2015/Special%20MPCN%20LANGKAWI/87-92.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Kandampully, Jay, Tingting Zhang, and Anil Bilgihan. 2015. Customer loyalty: A review and future directions with a special focus on the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 27: 379–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenesei, Zsófia. 2017. Possibilities of measuring customer satisfaction in a multidimensional approach (in Hungarian). Statisztikai Szemle 95: 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapalová, Alena. 2011. Competitiveness of Firms, Performance and Customer Orientation Measures–Empirical Survey Results. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis LIX: 195–202. Available online: https://acta.mendelu.cz/media/pdf/actaun_2011059070195.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2017).

- Kliestik, Tomas, Maria Kovacova, Ivana Podhorska, and Jana Kliestikova. 2018. Searching for key sources of goodwill creation as new global managerial challenge. Polish Journal of Management Studies 17: 144–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, Paul, and Maurice Obstfeld. 2003. International Economics. Budapest: Panem. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Vinod, Zillur Rahman, Absar Ahmad Kazmi, and Praveen Goyal. 2012. Evolution of sustainability as marketing strategy: Beginning of new era. Paper presented at International Conference on Emerging Economies—Prospects and Challenges (ICEE-2012), Pune, India, January 12–13; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Huang Ning, An Sheng Lee, and Yo Wen Liang. 2019. An Empirical Analysis of Brand as Symbol, Perceived Transaction Value, Perceived Acquisition Value and Customer Loyalty Using Structural Equation Modeling. Sustainability 11: 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jim. 2009. Does Size Matter in Firm Performance? Evidence from US Public Firms. International Journal of the Economics of Business 16: 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yu Lim, Minji Jung, Robert Jeyakumar Nathan, and Jae-Eun Chung. 2020. Cross-National Study on the Perception of the Korean Wave and Cultural Hybridity in Indonesia and Malaysia Using Discourse on Social Media. Sustainability 12: 6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Li. 2008. Study of the relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty in telecom enterprise. Paper presented at 4th International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Mobile Computing, Dalian, China, October 12–14; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, Henry F. 1974. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 39: 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, Robert K., Włodzimierz Sroka, and Radka MacGregor Pelikánová. 2020. A comparative study of low-level management’s attitude to marketing and innovations in the luxury fashion industry: Pro-or anti-CSR? Polish Journal of Management Studies 21: 240–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makó, Csaba, Miklós Illéssy, and András Borbély. 2018. Automation and creativity at work. Educatio 27: 192–207. (In Hungarian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Matzler, Kurt, and Hans Hinterhuber. 1998. How to make product development projects more successful by integrating Kano’s model of customer satisfaction into quality function deployment. Technovation 18: 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Tracy, Donald Barnes, and Scott Friend. 2016. The role of delight in driving repurchase intentions. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, Robert Jeyakumar, Vijay Victor, Chin Lay Gan, and Sebastian Kot. 2019. Electronic commerce for home-based businesses in emerging and developed economy. Eurasian Business Review 9: 463–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, Robert Jeyakumar, Vijay Victor, Melanie Tan, and Maria Fekete Farkas. 2020. Tourists’ Use of Airbnb App for Visiting a Historical City. Information Technology and Tourism 22: 217–42, ISSN 1943-4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann-Bodi, Edit. 2013. Examining the impact of customer acquisition method on customer satisfaction and loyalty in the organizational market. Investigating the impact of the recommendation using structural modeling. Vezetéstudomány-Budapest Management Review 44: 29–44. (In Hungarian). [Google Scholar]

- Niresh, J. Aloy, and Thirunavukkarasu Velnampy. 2014. Firm Size and Profitability: A Stud y of Listed Manufacturing Firms in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Business and Management 9: 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocak, Murat, and Derya Findik. 2019. The Impact of Intangible Assets and Sub-Components of Intangible Assets on Sustainable Growth and Firm Value: Evidence from Turkish Listed Firms. Sustainability 11: 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2011. New sources of growth: Knowledge-Based Capital. Key Analyses and Policy Conclusions, Synthesis Report. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/sti/inno/knowledge-basedcapital-synthesis.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2017).

- Öner, Özge. 2014. Retail Location, Jönköping University, JIBS Dissertation Series No. 097. Available online: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:715468/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Pakurár, Miklós, Hossam Haddad, János Nagy, József Popp, and Judit Oláh. 2019. The Service Quality Dimensions that Affect Customer Satisfaction in the Jordanian Banking Sector. Sustainability 11: 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pálfi, Nóra. 2019. Cultural and social capital as a factor of competitiveness based on the literature review (in Hungarian). In Csath, Magdolna; Taksás, Balázs; Nagy, Balázs; Vinogradov, Szergej; Pálfi, Nóra; Fási, Csaba—Csath, Magdolna (szerk.) A Versenyképesség-Mérés Változásai és új Irányai. Budapest: Dialóg Campus Kiadó-Nordex Kft, pp. 137–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal. 2011. Consumer culture and purchase intentions toward fashion apparel in Mexico. Journal of Database Marketing and Customer Strategy Management 18: 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, Christian M., Sven Wende, and Jan-Michael Becker. 2015. SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS, Bönningstedt. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Robine, W. L. 2017. Globalization and the Fashion Industry. Available online: https://fashionhistory.lovetoknow.com/fashion-clothing-industry/globalization-fashion-industry (accessed on 5 January 2019).

- Rodov, Irena, and Philippe Leliaert. 2002. FiMIAM: Financial method of intangible assets measurement. Journal of Intellectual Capital 3: 323–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, Larry J., and John A. Czepiel. 1984. A Marketing Approach to Customer Retention. Journal of Customer Marketing 1: 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruane, Lorna. 2014. Exploring Generation Y Consumers’ Fashion Brand Relationships. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10379/4395 (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- Saliha, Theiri, and Ati Abdessatar. 2011. The Determinants of Financial Performance: An Empirical Test Using the Simultaneous Equations Method. Economics and Finance Review 10: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Satt, Harit. 2016. Holidays’ effect and optimism in analyst recommendations: Evidence from Europe. Corporate Ownership and Control Journal 13: 467–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Tsui-Yii, and Chien-Ching Yang. 2019. Generating intangible resource and international performance: Insights into enterprises organizational behavior and capability at trade shows. Journal of Business Economics and Management 20: 1022–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SmartPLS GmbH. 2019. SmartPLS Software and Webpage. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com/ (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Statista.com. 2019. Most Expensive Retail Locations Worldwide as of June 2019, by Annual Rent. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/264903/most-expensive-shoppingstreets-for-retail-rent-worlwide/ (accessed on 2 October 2019).

- Subramaniam, Mohan, and Mark A. Youndt. 2005. The influence of intellectual capital on the types of innovative capabilities. Academy of Management Journal 48: 450–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suebsaiaun, Atisin, and Thepparat Pimolsathean. 2018. Thai home improvement retailer customer loyalty: A SEM analysis. Journal of International Studies 11: 120–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, Vijay, Jose Joy Thoppan, Maria Fekete-Farkas, and Janush Grabara. 2019. Pricing strategies in the era of digitalisation and the perceived shift in consumer behaviour of youth in Poland. Journal of International Studies 12: 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, Vijay, Nadirah Sharfa, Robert Jeyakumar Nathan, and Jalal Hanaysha. 2018. Use of Click and Collect E-tailing Services among Urban Consumers. Amity Journal of Marketing 3: 1–16, ISSN 2456-1703. Available online: https://amity.edu/UserFiles/admaa/b9dbbPaper%201.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Whittington, Geoffrey. 1980. The Profitability and Size of United Kingdom Companies. The Journal of Industrial Economics 28: 335–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Ken Kwong-Kay. 2013. Partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Marketing Bulletin 24: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- World Trade Organization. 2018. World Trade Statistical Review 2018. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/wts2018_e/wts18_toc_e.htmhttps://shenglufashion.com/2018/08/16/wto-reports-world-textile-and-apparel-trade-in-2017/ (accessed on 2 October 2019).

- Zatta, Nascimento Fernando, Elmo Tambiso Filho, Fernando Celso de Campos, and Rodrigo Randow Freitas. 2019. Operational competencies and relational resources: A multiple case study. RAUSP Management Journal 54: 305–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zineldin, Mosad, Katty Samir Nessim, Emmie Thurn, and David Gustafsson. 2014. Loyalty, Quality and Satisfaction in FMCG Retail Market does Loyalty in Retailing Exist? Journal of Business & Financial Affairs 3: 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| H | Std Beta (β) | Mean (M) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p | Test Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complaint Handling -> Purchase Satisfaction | H1 | 0.221 | 0.234 | 4.837 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Customer Loyalty -> Brand Ambassador | H2 | 0.412 | 0.417 | 7.419 | 0.000 | Supported |

| CRM -> Purchase Satisfaction | H3 | 0.137 | 0.162 | 3.136 | 0.009 | Supported |

| Online Presence -> Purchase Satisfaction | H4 | 0.160 | 0.182 | 4.160 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Promotions -> Purchase Satisfaction | H5 | 0.153 | 0.192 | 4.571 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Purchase Satisfaction -> Brand Ambassador | H6 | 0.232 | 0.297 | 3.991 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Purchase Satisfaction -> Customer Loyalty | H7 | 0.486 | 0.490 | 10.205 | 0.003 | Supported |

| Sales Staff -> Purchase Satisfaction | H8 | 0.068 | 0.084 | 1.617 | 0.106 | Not Supported |

| Shopping Ambiance -> Purchase Satisfaction | H9 | 0.146 | 0.148 | 2.787 | 0.006 | Supported |

| Navigation in Stores-> Purchase Satisfaction | H10 | 0.170 | 0.172 | 3.316 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase Satisfaction -> Customer Loyalty -> Brand Ambassador | 0.20 | 0.20 | 6.37 | 0.00 |

| Complaint Handling -> Purchase Satisfaction -> Customer Loyalty | 0.11 | 0.11 | 4.60 | 0.01 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonda, G.; Gorgenyi-Hegyes, E.; Nathan, R.J.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Competitive Factors of Fashion Retail Sector with Special Focus on SMEs. Economies 2020, 8, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8040095

Gonda G, Gorgenyi-Hegyes E, Nathan RJ, Fekete-Farkas M. Competitive Factors of Fashion Retail Sector with Special Focus on SMEs. Economies. 2020; 8(4):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8040095

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonda, Gyorgy, Eva Gorgenyi-Hegyes, Robert Jeyakumar Nathan, and Maria Fekete-Farkas. 2020. "Competitive Factors of Fashion Retail Sector with Special Focus on SMEs" Economies 8, no. 4: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8040095

APA StyleGonda, G., Gorgenyi-Hegyes, E., Nathan, R. J., & Fekete-Farkas, M. (2020). Competitive Factors of Fashion Retail Sector with Special Focus on SMEs. Economies, 8(4), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8040095