Abstract

The Regional Unit of Kastoria is a rural area in Northwestern Greece, located on the borderline with Albania. Kastoria city, the capital and the largest city of the Kastoria Regional Unit, is known for the production of high-quality fur products. The fur industry has faced a marked crisis from the 1980s onwards, which has contributed to pushing the local economy towards the development of tourism. However, the tourism industry, developed during the last 20 years, has an undefined character. Specifically, tourism is characterized as small-scaled owing to the limited number of mainly domestic tourists, who, in combination with the economic crisis of the last decade, slowed down the initial accelerated trend. The purpose of this paper is to capture the opinions and attitude of Kastoria visitors towards tourism, as well as to illustrate the changes as a consequence of the economic crisis. In this context, a survey was carried out in two periods (in 2008 at the beginning of economic crisis and in 2017 at the end of this crisis) using a structured questionnaire and with a sample of 232 visitors in total. Our findings are highlighted in an effort for policy makers and marketing planners to formulate appropriate marketing strategies and to reconstruct and promote the local touristic product and attract visitors in these border areas.

JEL Classification:

L83; O20; R12

1. Introduction

The special and alternative forms of tourism appeared in Greek reality during the 1980s, with a particular boom during the following two decades. Apart from skepticism towards the consequences of massive tourism (Triarchi and Karamanis 2017), they have contributed to an increase in demand for diversified tourism services as well as to the changes that have taken place in the tourism sector, contributing to society and in the content of development itself (Coccossis et al. 2011). At the same time, the development of alternative forms of tourism has been supported by both the investment support programs designed mainly by European initiatives and policies, and by the increasing life quality of Greek people owing to increased income and liquidity for consumption. Each form of tourism usually emphasizes in specific resources or activities or interests and events that all result in the differentiation among them and the categorization of tourism (Belias et al. 2017) at the base mainly of destination and tourism demand characteristics (Pearce 1989; Coccossis and Constantoglou 2006). The variety of special and alternative forms of tourism results occasionally in an overlap between the forms of tourism, of which not all are known to the general public (Kolokontes et al. 2009).

During the period 2008–2017, the Greek economy was in recession owing to the economic crisis of public debt, which negatively affected all the indicators of the economy. In the period 2008–2013, the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) decreased 26.5%, while the decline in domestic demand reached 31%. During the same period, unemployment rose from 8.6% to 27.9%, while productivity declined 6.5% (Petrakos and Psycharis 2016; Macdonald 2018; INSETE Intelligence 2019). After 2014 the Greek economy was gradually adjusted and recovered, with the exception of 2015, with the derailment and the imposition of capital controls, until 2017, the year that the economy’s growth begun again (INSETE Intelligence 2019).

In this volatile environment, tourism exhibited a significant decline till 2012 (Papatheodorou and Arvanitis 2014; GTO—Greek Tourism Organization 2015), and then managed to recover, having a substantial contribution to the national economy with its constantly increasing revenue (INSETE Intelligence 2019). The foreign-incoming tourism between 2009 and 2017 offered to the Greek economy approximately €125 billion, while its revenues increased by 50% from 2012 until 2017. The employment in tourism between 2009 and 2017 increased by 12.7%, in contrast to other sectors of the economy, where a decline of approximately 18% was recorded (SETE Intelligence 2018; INSETE Intelligence 2019; ELSTAT—Hellenic Statistical Authority 2019). However, the alternative forms of tourism were characterized as one of the Greek economy crisis’ victims, as they relied mainly on domestic tourism. Domestic tourism has suffered a significant decline owing to the decline in Greek citizens’ incomes (Chatzitheodoridis et al. 2014, 2016). Although, during the last three years, domestic tourism has recorded a slight increase, it is characteristic and noteworthy that the domestic tourism expenditure for trips of at least one overnight stay was €1.398 million for 2017, when in 2008, it was €3.868 million. Thus, during the period of economic crisis, the expenditure of domestic tourism decreased by 63.9% (ELSTAT—Hellenic Statistical Authority 2018).

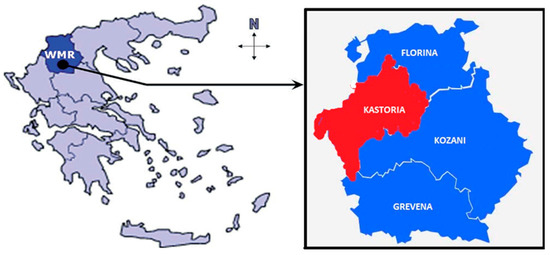

The Region of Dytiki (Western) Macedonia, where the Regional Unit of Kastoria is located (Figure 1), has been, post-war to date, the major place of electricity production throughout the country owing to abundant lignite deposits (Kolokontes and Chatzitheodoridis 2008). On the contrary, concerning the tourism sector, taking into account the regional distribution of tourism expenditure as well as the numbers of beds, Kastoria occupies the last position between the thirteen regions of the country (Zacharatos et al. 2014; SETE Intelligence 2018; Chatzikyriakidis 2019). For all these decades, the area of Kastoria has remained in the shadow of the energy axis of the Region of Dytiki Macedonia (Kozani, Ptolemaida, Florina), supporting its development by establishing a “brand name” in the fur field, while keeping unchanged its natural resources. During the 1990s, the decline in fur activity forced the local community to re-orientate its development strategy, combining in its main axes, tourism with traditional fur production and trade. Moreover, touristic infrastructure in Kastoria had been steadily increasing during the last five years before the economic crisis, an effort that was halted by the economic crisis (Chamber of Kastoria 2018). Despite the efforts of the local community, the tourism product of Kastoria remains small in size, indefinable, and connected to both the domestic tourism and the area’s varied environmental and cultural resources (Chamber of Kastoria 2018). The limited contribution of tourism to the local economy and the lack of tourist identity, of both Kastoria and the Region of Dytiki Macedonia in general, are readily apparent and remain the main issues in their strategic development planning (BCS—Development and Environmental Consultants 2018).

Figure 1.

Map of Greece with Dytiki (Western) Makedonia Region and regional section of Kastoria.

This paper focuses on comparing Kastoria’s visitors’ views about the tourism product of the area before and at the end of Greek economic crisis, as well as identifying the resources associated with the attractiveness of the area that shape its tourism product. The study concerns a rural area that belongs to the list of less favored and mountainous areas, not surrounded by the sea, and at the same time located in the border area. All these characteristics underline the difficulties for the tourism activities’ development by such areas in a viable size. The contribution of the study is to highlight the need of these less favored areas for redesign and reconstruction of their rural tourism product, taking into account the perceptions and opinions of current visitors. At the local level, the identification of crucial tourism resources and structural elements of tourism (especially under economic instabilities) could lead to the enhancement of the attractiveness of the tourist destination through strategic marketing planning. This investigation of the tourism product’s identity could be adopted from similar rural areas under geographical disadvantages. The study consists of the introduction, the presentation of the region under examination, the way the research is carried out, and the methodology followed. Finally, the research’s results are presented and discussed with a summary of the conclusions as the last part of the study.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Tourism Impacts and the New Tourism

The current pandemic of Covid-19 has caused a dramatic impact on the global economy and especially on tourism, where it is expected to significantly change the tourism performance and image for an unknown period of time (Gössling et al. 2020; UNWTO—United Nations World Tourism Organization 2019). Despite this, tourism remains one of the largest economic activities in the world, contributing more than 10% to global GDP (WTTC—World Travel & Tourism Council 2016; UNWTO—United Nations World Tourism Organization 2019), while in recent decades, it has linked destinations and made travel more affordable. The international, multiplier, and export dimension of tourism, which is the main reason for its growth, is also its “Achilles’ heel”, as the activity itself is exposed to changes related to its development (Gee and Fayos-Solà 1997; Dwyer et al. 2009). Political, economic, and environmental trends and the climate change, as well as technological, demographic, and social trends, are in a constant conversation with tourism as they are in an interactive relationship and differentiate it accordingly, through dynamic changes (Guduraš 2014).

Until the current pandemic, which reduced and zeroed in many cases the use and value of products, services (private and public), and resources included in tourism, there was the impression that it was mainly the environmental and the economic trends representing the most influential and diversifying activity. At the same time, owing to its size and complexity, tourism as a phenomenon has mainly economic, environmental, and socio-cultural impacts on the destinations and people affected (Guduraš 2014; Shin et al. 2017; Martín Martín et al. 2018). Mass tourism, large gatherings, over-exploitation, depletion of environmental resources and tourist destinations, and ultimately over-tourism itself create negative externalities and deadlocks in the economies, societies, and environments that support it (Smith 1989; Macleod 2004; Pintassilgo and Silva 2007; Schubert 2010; Martínez Garcia et al. 2017). In the beginning of the 1980s, these negative effects were felt and made necessary the development of a new tourism form through the segmentation of the tourism activity in order to improve its sustainability, but also to meet the tourist demand for more environmentally friendly and specialized tourism products, although the dominance of mass tourism has not been reduced yet.

The “new tourism” that emerged against mass tourism had as its main axis and priority the natural, structured, and cultural environment in the context of tourism development planning of an area. The variations of this model presented in the next years were usually in agreement with the need to maintain the authentic and unique image of the tourist destination, and thus the investment and projects would be limited in size and scale, while the participation of the local population was necessary. Rosenow and Pulsipher (1979) proposed the term “new tourism” as a way of developing American tourism. The key element was for both the local communities and their visitors to be equally benefited from the new diversified tourism, each one contributing in their own way. The new tourism (Rosenow and Pulsipher 1979) was based on eight principles: (1) unique heritage and environment, (2) special quality attractions, (3) trying to develop additional local attractions, (4) economic opportunities and cultural enrichment, (5) local services, (6) marketing communication, (7) adaptation of assets to the local carrying capacity, and (8) prevention of energy losses (Triarchi and Karamanis 2017). These principles seem to represent a good basis for a small-scaled tourism development plan today, for destinations that do not seek over-tourism or under-tourism as an ‘alternative’ for visitors who just want to avoid the negative effects of mass tourism (Martín Martín et al. 2018; Jayasundera 2019).

From this time point and gradually, the “new” tourism took many forms, mainly on the basis of the specialized demand from tourists with specific and different interests. The term “alternative forms of tourism” today is under the framework of “special tourism forms” and contains a variety of other forms of tourism or specialized markets (Pearce 1989; Coccossis and Constantoglou 2006; Isaak 2010). So, the alternative tourism includes a number of tourist forms such as “eco”, “agro”, “community”, and “rural tourism” (Aslam et al. 2014).

However, in addition to the specialized demand from tourists in the frame of the alternative forms of tourism, the role of the tourist destination as content that includes specific products, services, resources, and the experience provided locally is of equally high importance (Buhalis 2000). The “destination mix” created by the combination of the content included the following: infrastructures and facilities, attractions and events, transfers, and the hosting resources provided to visitors (Huang et al. 2013). The “destination mix” along with the intangible characteristics of the place (fame, experience) and the promotion create, in the tourists’ mind, the impression of the ‘tourism image’ of a destination (Kim and Perdue 2011). The tourism image leads to the creation of the brand and the tourism product of an area (Pereira et al. 2012). According to Wheeler et al. (2011), the branding of a destination requires a holistic approach and does not focus on specific characteristics. On the other hand, the components of the tourism products have been the subject of many typologies in the past.

2.2. Tourism in the European Rural Areas

One of the most important forms of alternative tourism is tourism developed in rural areas and, more specifically, agro-tourism (Guido Van and Durand 2003). After the 1970s, it began to grow in Europe mainly owing to the effects of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the farmers’ crisis (Dimitrovski et al. 2012) regarding their agricultural productions. Since the 1990s, various European Union (EU) programmes and community initiatives (LEADER, PRODER, Integrated Development Programmes of the Rural Areas) led to an explosion in the development of alternative forms of tourism in the European rural areas (Iakovidou et al. 2002; Castellano-Álvarez et al. 2019) and in particular of agro-tourism in the countries of the south (Iakovidou 1997; Nastis and Papanagiotou 2009; Chatzitheodoridis et al. 2016). Keeping this in mind, there was an important contribution of the integrated local development strategies, which were supported mainly through the community initiative LEADER that had boost agro tourism through the construction of a significant number of agro tourism accommodations and businesses (Chatzitheodoridis et al. 2016; Castellano-Álvarez et al. 2019). Several of those investments, mainly in construction of traditional hostels, were implemented and in the Region of Western Macedonia (RWM—Region of Dytiki (Western) Macedonia 2017). At the same time, agro-tourism became known to the general public and gained a reputation to the point of almost complete identification with the alternative forms of tourism. This period coincided with the liquidity increase for consumption, which had an impact on the increased domestic demand for holidays, apart from summer season holidays (BCS—Development and Environmental Consultants 2018). In Greek society, in the decade of 2000, people were informed more about the other forms of alternative tourism, while additional interests were expressed related to tourism forms beyond agro-tourism, even during the economic crisis.

Alternative forms of tourism, especially agro tourism, are more compatible with the rural areas on account of their size (relatively small scaled), their direct connection with the environment, and the relatively less negative or even positive effects on this, but also with the potential to be the result of a local planning (Fleischer and Felsenstein 2000; Sanagustin-Fons et al. 2018).

The definition of “agro-tourism” is difficult to formulate, as many definitions have been proposed in the international literature concerning its meaning and characteristics (Lane 1994; Iakovidou 1997; Marques 2006; Phillip et al. 2010). In an effort to combine different definitions, agro-tourism constitutes an activity developed in a non-urban environment by those employed in the primary and secondary sectors of production (match more with Iakovidou’s definition). It offers the possibility to the tourist-visitor to enrich his/her touristic experience by participating in activities and in the countryside life, while he/she contributes positively to the social and economic development of the areas. Agro-tourism is directly related to locality, improving the quality of life and working conditions of rural populations, and contributes to the viability of local communities, promotes local traditional products, and eventually contributes to cultural protection and the preservation and utilization of architecture and the cultural heritage of each place (Giannetto and Souca 2011; Sanagustin-Fons et al. 2018). In the framework of European policy, the development of this form of tourism utilizes and protects the admittedly exceptional natural and cultural environment of the countryside, leads to the diversification of the productive base of local rural communities (Chatzitheodoridis and Kontogeorgos 2020), and offers new jobs and supplementary income to the local population (Anthopoulou 2000), not only from the purely tourist activity, but also from the use and marketing of local traditional products. Depending on the type of accommodation and the participation of the visitor-tourists in the rural life, agro-tourism is developed in various types (Anthopoulou 2000; Phillip et al. 2010; Dimitrovski et al. 2012).

Several studies from many different countries indicate either positive economic, environmental, and social effects of tourism in the rural areas (Loukissas 1982; Park et al. 2008; Pascariu and Tiganasu 2014; Woo et al. 2015), or a negative impact (Almeida García et al. 2016; Hajimirrahimi et al. 2017; Ibănescu et al. 2018). After the continuous development of agro-tourism since the early 1990s, during the last years and specifically after the economic crisis of 2008, skepticism began to arise regarding the limits of rural tourism (Chatzitheodoridis et al. 2014; Martínez Guaita et al. 2019; Castellano-Álvarez et al. 2019; Martín Martín et al. 2020). This has as main causes both the maximization of the agro-tourism product in some rural areas and its relationship and impact with seasonality and viability (Dimitrovski et al. 2012; Martín Martín et al. 2020). The subsidies to create agro-tourism accommodations through the various policies combined with the high occupancy rates of such accommodation before 2008 have created a high funding demand for related investments. Especially in the case of the integrated local development strategies in some countries such as Greece, they led the local action groups (LAGs) to channel most of their resources into investments in agro-tourism. In these cases, local strategies were linked with operational programmes that did not favor the multifunctionality of the rural areas, but channeled much more than 50% of their total budgets in measures mainly into agro-tourism activities (Chatzitheodoridis et al. 2006). At the same time, tourism in rural areas is linked to seasonality and a short length of stay, which does not allow for the overall high occupancy of these businesses throughout the year (Barros and Machado 2010; Martín Martín et al. 2020), as well as with investments by the locals that they had not always made as purpose, the creation of a viable business, and the upgrade of their living level (Castellano-Álvarez et al. 2019). The rapid increase of the number of agro-tourism businesses in countryside, combined with the economic crisis that triggered both a decline in demand and problems such as a lack of liquidity, led to a loss in the viability of many such businesses and investments (Chatzitheodoridis et al. 2014). The economic crisis simply has highlighted the wrong strategy of some LAGs who transformed agro-tourism into a dominant activity in their rural areas and not an activity that would provide diversification of the local production and additional income to the rural population.

Furthermore, the impacts of the declining demand owing to the economic crisis, especially by the domestic tourists who were usually the main customers of agro-tourism accommodation and hostels, cannot be ignored (Guduraš 2014; Chatzitheodoridis et al. 2016; Voutskidis 2016; Varvaressos et al. 2017; Castellano-Álvarez et al. 2019). According to Chatzitheodoridis et al. (2014), in the rural areas of Greece during the economic crisis, investments in tourism accommodation were limited or faced implementation problems. Especially in the regional sections of the Region of Western Macedonia, such as Grevena and Florina, some tourist facilities have been devalued (Parallaxi 2018) and in the same period tourism cooperatives and traditional agro-tourism guesthouses have been forced to suspend their operations or close completely (Chatzitheodoridis et al. 2016). The tourism’s size in terms of tourist accommodations, arrivals, and overnight in the case of Kastoria regional section stays has remained small, while the high dependence of the area’s tourism from the domestic visitors has prevented following the country’s tourism development during the economic crisis. According to Bogdanov and Zečević (2011), the rural tourism situation in Serbia was similar in the period between 1990 and 2010, where the tourism sizes declined mainly owing to the high dependence of activity by the domestic tourism, as well as by the structure and the small size of the tourism product in specific Serbian rural areas (Dimitrovski et al. 2012). In Spain, which was also subjected to the ‘bad face’ of economic crisis according to Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2019) in the Region of La Vera, owing to the economic crisis, the demand for accommodations in this rural region was significantly reduced and the small businesses in rural tourism and in the relevant investment had viability problems.

Less favored and mountainous areas, the islands, and border areas mostly belong in the rural areas and, as such, their development potential is limited. Rural tourism is usually one of the few economic opportunities of the rural areas (Wilson et al. 2001). For instance, in the case of Greece, within periods of economic instability such as in the last economic crisis, these areas account more losses in comparison with the urban or coastal areas, as their main connection often with domestic tourism leads to withering and loss of human resources and income (Papatheodorou et al. 2010; Giannetto and Souca 2011; Papatheodorou and Arvanitis 2014; Guduraš 2014; Varvaressos et al. 2017). A survey of visitors’ impressions and their views in such rural areas with small-scaled tourism on their resources and attractions, as well as their tourist image, may lead local authorities and stakeholders involved in tourism to create the right mix of destination and, finally, an attractive tourist product for their area. Such an effort requires planning, improving supply, and selecting appropriate marketing strategies.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area

The Kastoria Regional Unit was selected as the case study of this paper. Kastoria is geographically located in Western Macedonia, bordering Albania on the north. Administratively, it belongs to the Region of Dytiki (Western) Macedonia and, together with Kozani, Florina, and Grevena, comprises the four regional units of the region (Figure 1). Kastoria consists of three Municipalities with a total population of 51,414 inhabitants. According to the 2011 census, 35,874 of the total population are residents of the municipality of Kastoria.

The per-capita GDP of Kastoria is low, a fact that ranks it among the lowest positions at the country level, while it decreased by 19% during the period 2008–2016, and gross value added (GDA) decreased by 16% in the same period (Chatzikyriakidis 2019). Kastoria’s per-capita GDP composition comprises 10.33% of primary production, 17.74% of secondary production, and 75.2% of the dominant tertiary sector (RWM—Region of Dytiki (Western) Macedonia 2017). Although a significant decline in productive activity in the traditional fur industry was observed over the last decades, it has not diminished its importance to the local economy as it continues to contribute productively and commercially mainly through its export orientation. According to the Chamber of Kastoria (2018), trade and services were strongly affected by the economic crisis, while during the period 2009–2017, the local economy shrunk by 1800 businesses in all sectors. Accordingly, the unemployment rate in Kastoria recorded a steady increase, which has its roots in both the earlier recession of the fur industry and the subsequent economic crisis. However, it should be noted that, regarding the primary sector, the area has a strong advantage in the production of apples and beans.

Kastoria has significant natural and cultural resources. The lake of Kastoria is closely linked with the area endowing it with magnificent natural beauty. The lake includes the lakeside area and the mountain range to the west and north, as well as the city of Kastoria itself. It is a landscape of high aesthetics and a wetland of great ecological value, as it maintains rich bird’s fauna, while significant infrastructures have been developed associated with urban and tourist functions on its lakeside (hiking trails, cultural infrastructures, and so on).

Part of the city of Kastoria has been declared as a traditional settlement, which is singled out mainly for its traditional mansions and churches. Kastoria was an important urban and administrative center of the wider region during the Byzantine, Post-Byzantine, and Ottoman periods, preserving significant monuments of those periods (there are more than 72 characterized as monuments of the modern era). Among those monuments, there is a significant number of house-mansions of “Macedonian Architecture”. Moreover, the most remarkable attractions of Kastoria are the lake’s prehistoric settlement of Dispilio, the Drakos’ cave located in the north part of the city, the aquarium, and the importance of the number and quality museums. Finally, there are two significant elements for the tourist development of the area; that is, the ski resort on the Vitsi mountain and Kastoria’s airport with the ability to receive international flights. At the same time, the Egnatia motorway vertical axis has improved the area accessibility mainly with the urban centers of northern Greece and generally to neighboring Balkan countries.

3.2. Tourism in the Study Area

Tourism in Kastoria’s area, as well as throughout the Region of Dytiki Makedonia, can be described as limited to the number of accommodations, arrivals, and overnight stays, and is mainly associated with the utilization of the region’s natural and cultural resources, as well as with commercial activity of fur. The tourist product of Kastoria is difficult to describe beyond its the strong connection with the domestic tourism, the small number of overnight stays, and its limited seasonality.

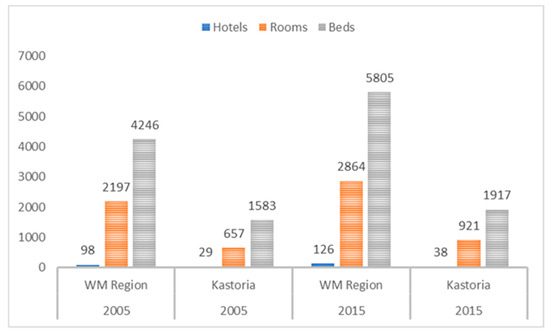

The Region of Dytiki Makedonia has a very small share in the number of hotels throughout the country. During 2015, the 126 total units corresponded to 1.29% of level units and just 0.7% of the rooms and beds of the entire country (BCS—Development and Environmental Consultants 2018). At the level of beds, the Kastoria area holds 33% of the total potential of the region, while there are qualitative differences in the accommodation composition compared with the other regional sections. Comparing the years 2005 and 2015, there was an increase in the number of hotel units and rooms and beds, respectively, in both the region and in Kastoria (Figure 2). This increase is attributed to the period up to 2010 as a result of the increased demand for winter holidays and excursions observed before the economic crisis. Moreover, Kastoria has two of the three total five-star hotels in the region and 13 of the 18 total four-star hotels (ELSTAT—Hellenic Statistical Authority 2017). The total number of rooms and beds of the five- and four-star hotels in Kastoria is 354 rooms and 764 beds, compared with the corresponding 477 rooms and 916 beds throughout the region. Kastoria also has 6 three-star and 7 two-star hotels, 7 villas, and 36 rental units (BCS—Development and Environmental Consultants 2018).

Figure 2.

Number of hotels, rooms, and beds in the Region of Dytiki Macedonia (WM Region) and Kastoria in the years 2005 and 2015.

The data above show the quality superiority of Kastoria in terms of hotel accommodation compared with the rest of the areas of the Region of Dytiki Makedonia. The overwhelming majority of hotel accommodation is concentrated within the Municipality of Kastoria. Finally, it should be noted that the Vitsi ski resort in Kastoria has three ski slopes, a snowboard and snow-park, a slope for beginners, and a ski school.

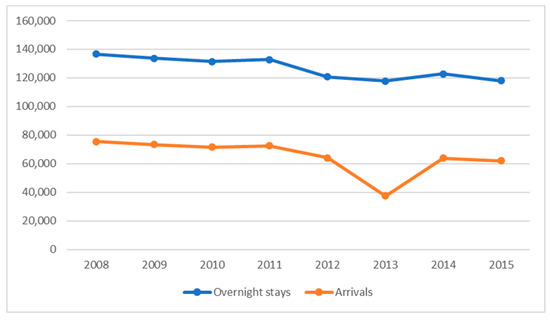

In 2015, the percentage of overnight stays of foreign tourists in the area of Kastoria was 16.67% of all overnight stays. This was the highest percentage in the whole region, a fact that does not reduce the strong dependence of the area on domestic tourists (83.33%). Overall, during the period 2008–2015, the number of arrivals and overnights in the area of Kastoria recorded a steady decline of 2–3% annually (Figure 3). The main reason of this decline course was the decrease in domestic tourism, as the overnight stays of foreign tourists in Kastoria did not record a substantial decline. The fact that there is no sea in the region affects the time distribution of arrivals and overnight stays, as the seasonality is less pronounced compared with the country and the months of summer holidays are those with the lowest demand (BCS—Development and Environmental Consultants 2018).

Figure 3.

Evolution of the number of arrivals and overnights per year in Kastoria for the period 2008–2015.

The recorded overnight stays per visitor in the area in 2015 were approximately 2.3, with almost unchanged fluctuations throughout the year, except for specific periods. The most visited periods in Kastoria, with the highest levels of visitation and overnight stays, are during the holidays of Christmas, New Year, Easter, the Kastoria Carnival (Ragutsaria), and the River Party in Nestorio (Chamber of Kastoria 2018).

3.3. Data Collection and Methodology

In this study, primary and secondary data sources were used. Specifically, primary data were collected using a questionnaire from a random sample of visitors/tourists of Kastoria in two different years. The two surveys that took place in 2008 and 2017 aimed mainly to investigate the ‘recognition’ of the tourism product of the Kastoria area by the visitors and their views of the tourism resources and services of the area. The questionnaires were collected through personal interviews in 2008 and 2017, and in particular during the first ten days of May in both years. The bulk of the questionnaires (90%) were filled by customers of the city’s hotels and tourist accommodations, and the rest by hostels within the regional unit of Kastoria. The visitors’ questionnaire included questions related to the following: the individual and family characteristics of the respondent, their transport and accommodation, their preferences and perceptions regarding the tourist resources of the area and the form of tourism there, their satisfaction with the local services provided, as well as their intentions for future visits back to the area. The random sample in both years was 260 visitors. From the questionnaires collected, only 232 (126 of 2008 and 106 of 2017) were considered as reliable, which represented the final sample.

Firstly, descriptive statistics were calculated for the data gathered. Then, data were analyzed by the use of statistical test x2 for the comparison of the quality characteristics, and finally the binary logistic regression analysis was applied to classify visitors of the Kastoria City in visitors willing to visit the city again and visitors who are reluctant to visit Kastoria again (“willing” and “reluctant”). At this point, it must be noted that binary logistic regression is most useful in cases where we want to model the event probability for a categorical response variable with two outcomes. As the probability of an event (willing or reluctant) must lie between 0 and 1, it is impractical to model probabilities with linear regression techniques, because the linear regression model allows the dependent variable to take values greater than 1 or less than 0. The logistic regression model is a type of generalized linear model that extends the linear regression model by linking the range of real numbers to the range 0–1.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Participants

The participants of both surveys are domestic tourists (99.1%), single (59.5%), male (53.4%), having a high school level of education (56.4%), mainly between 31 and 45 years old (43.5%), and their place of origin is a distance less than 3 h from Kastoria (73%). The respondents’ demographic profile is presented in Table 1 as a total and for the two years separately. In particular, the demographic profiles of the respondents of the two surveys have limited differences. The common element is the absence of foreign tourists, as there were only two tourists from Europe in the sample of 2017 and none in 2008. However, one can observe that there is a significant change between the place of origin of participants. In 2008, the visitors from neighboring areas (distance less than 3 h) made up 73% of the total sample, whereas this percentage was reduced in 2017 to 58.5%, with a respective increase of the visitors from places of origin with distance between 3 and 6 h.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants in the survey of 2008 and 2017.

According to Table 2, concerning the visitors’ accommodation for each year separately and in total, there is a tendency to prefer traditional hostels and hotels in the medium category (two-, three-star), with their price range either between 45 and 75 euros or below 45 euros (especially during 2017). Furthermore, the visitors of 2008 stayed mainly in double and single rooms (73.8% and 23.8%, respectively), whereas the visitors of 2017 stayed mainly in double and rooms with more than three beds (64.1% and 34%, respectively). As a result, the differences between the two years are not so great, so as to support that we are facing a major change in consumer behavior. Additionally, in 2008, 57.1% of the visitors stayed up to two nights in Kastoria, whereas the other 42.9% stayed three or four nights. In 2017, the percentage of the visitors that stayed in area for two nights increased to 79.2% of all visitors, confirming the short duration of visitors’ stay in the area.

Table 2.

Accommodation characteristics of the participants in the survey of 2008 and 2017.

From the total number—sum of both years—of visitors, 36.2% participated in a group trip-excursion via a travel agency; for each year, 2008 and 2017, this percentage was 41.3% and 30.2%, respectively. The rest of the respondents organized their trip by themselves by booking the accommodation in which they were staying. It is obvious that almost 70% of the visitors of 2017 preferred to travel individually without using the services of any travel agency.

4.2. Tourism Product through Visitors’ Perceptions

The visitors of Kastoria, during both 2008 and 2017, positively evaluated a series of services and characteristics of the tourism product of the area, as seen in Table 3. In particular, when asked about the quality of the accommodation in which they stayed, the hospitality of the residents, the quality of services and food, as well as the organization of attractions they visited, they responded, at high percentages, that all of them were very good or good in terms of quality. Despite this general finding, there are differences between the 2008 and 2017 visitors. Specifically, the evaluation of visitors of 2008 is very positive regarding the quality of the above elements, with the exception of the organization of the attractions, which they evaluated as moderate (53.2%). On the contrary, the evaluation of the visitors of 2017, although positive in all services, is more conservative. However, in the case of the organization of attractions, the majority of the visitors in 2017 (65.1%) evaluate it as very good or good.

Table 3.

Quality evaluation of core tourism services by the visitors of 2008 and 2017.

However, apart from the differentiation in the organization of attractions of Kastoria, which seems to have significantly improved during the period of crisis, the statistical Chi square test is also interesting. Specifically, Table 4 depicts the differentiation between the visitors of the two years regarding the creation of negative impressions. Therefore, visitors before the economic crisis, with a percentage of 39.7%, consider that there was nothing negative to mention, whereas 30.2% were negatively impressed by the garbage in the lake and in the city, and 13.4% of the visitors were negatively impressed by parking and the city’s narrow and uphill roads. None of the visitors of 2008 considered the prices to be high.

Table 4.

Cross tabulation for negative impressions and period/year.

In contrast, the visitors during the end of the economic crisis (2017), at 57.5%, mentioned nothing negative in the area. However, the visitors who had a negative impression of garbage and the city’s streets were 16% and 23.1%, respectively. Finally, 17% of all visitors during 2017 mention that the prices for food and accommodation in the area of Kastoria were high. It is likely that the economic crisis has improved the region’s image concerning cleanliness and attractions, in order to upgrade the area attractiveness. At the same time, the reduction in the purchasing power of visitors has created the impression of high prices for some visitors.

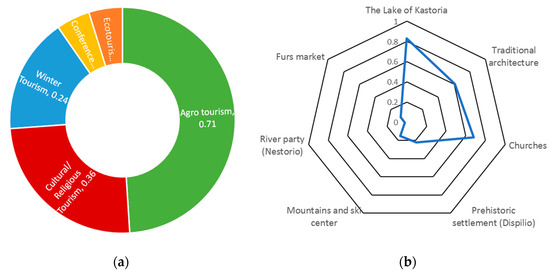

There is a particular interest in visitors’ assessments regarding the form of tourism that they believe the activity has in Kastoria. According to the mean values, as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, the visitors during 2008 believe that agro-tourism is the main form of tourism, followed by cultural and winter tourism to a lesser, but still significant degree (Figure 4a). Both eco-tourism and conference tourism were the last to be identified with the tourism product of Kastoria. Moreover, the same visitors estimate that the lake of Kastoria is the most important tourism pole of the area, followed by the churches/monasteries and the traditional architecture (Figure 4b), a fact that, to some extent, justifies their views on the form of tourism. The above picture was significantly differentiated by the visitor-respondents during the 2017 survey.

Figure 4.

(a,b) Mean value of the indicative forms of tourism and the most important tourism resources of the survey respondents in 2008.

Figure 5.

(a,b) Mean value of the indicative forms of tourism and the most important tourism resources of the survey respondents in 2017.

On the other hand, according to visitors in 2017, the predominant forms of tourism in Kastoria, with almost the same importance, are winter tourism and agro-tourism. Meanwhile, in the second degree, but at a measurable level, there are views that support the identification of the tourism form with cultural tourism and eco-tourism (Figure 5a). During 2017, the dominant assessment that the most significant tourism pole is the lake of Kastoria still exists, considering as the next important pole the mountainous areas with the ski center, as well as the traditional architecture of the area as the third tourism pole (Figure 5b). Finally, it is important to mention that the tourism resources, such as the tourist fur market, the lake prehistoric settlement, and the organization of the river party in Nestorio, are evaluated as less significant by fewer visitors.

The lake of Kastoria with the lakeside area seem to be the tourist pole-symbol, not only of the city, but also of the wider area, as evidenced by the answers of the visitors of both years. The fur market, as a factor in attracting visitors, seems to be declining over time, as seen in the ranking of the region’s tourist resources in both years. Despite this, a percentage of 50% of 2008 visitors stated that the purpose of their trip to Kastoria was to buy fur products and 65.9% declared that they bought or would buy fur products and as souvenirs. In 2017, 17% of visitors stated that their trip aimed at buying fur products and 51.9% bought or would buy as souvenirs, which shows that, even after the economic crisis, visitors are, to a significant degree, determined to buy a fur souvenir from Kastoria. Although interest in the fur market seems to be declining, fur production continues to be a useful factor in the framework of tourism planning in the region, which is necessary to be combined with innovative elements and actions.

4.3. Tourists’ Loyalty to the Current Tourism Product

In this study, the visiting decision is based on a set of personal characteristics and on a set of city services and characteristics, which in combination can affect visitors’ decision whether or not to visit the City of Kastoria and the broader area again. However, these characteristics could have a multiple or multidimensional effect on a visitor’s decision. Thus, a given characteristic may be associated with many incentives related to the decision of whether or not to visit this area again. Using the logistic regression model, the probability of visiting Kastoria again can be described as follows: πi = 1/(1 + e^(−z_i)), where pi is the probability that the ith case will visit Kastoria again and Zi is the value of the unobserved continuous variable for this ith case. The model also assumes that Z is linearly related to the predictors (the visitors characteristic and beliefs). Thus, Ζi = b0 + b1Χi1 + b2Χi2 + … + bpΧip, where Xij is the jth predictor for the ith case, bj is the jth coefficient, and p is the number of predictors. Finally, the regression coefficients are estimated through an iterative maximum likelihood method.

Table 5 presents the dependent and independent variables that are developed using the information collected in the research stage and depict the analysis used. In order to identify both cases, where the estimated model has small adaptation and cases that have an enormous effect in the model, the examination of residuals is required in the logistic regression analysis. Field (2005) provides analytical directions for a residual analysis of such models. However, the residual analysis of this model indicated that there is no need for special treatment of data in order to face extreme values or effects of specific cases in the total adaptation of the model. Field (2005) has also proposed the examination of multicollinearity by investigating the paired cross-correlations using the process of partial correlation provided by Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20.0 for Windows. Despite the existence of multicollinearity, this does not affect the values of the factors participating in the model, but only their significance. The examination of partial cross-correlations and the verification of the Pearson statistic showed that there is no statistically important cross-correlation between the variables participating in the model.

Table 5.

Logistic regression analysis for the factors affecting visitors’ decision to visit Kastoria again.

The above results indicate that visitors who characterize their visit to Kastoria as a short trip for recreation and as a winter destination are more probable to visit Kastoria again. The same occurs for visitors who claim that the main reason to visit Kastoria is to buy furs. It should be mentioned that visitors who claim that everything is fine in Kastoria (referring to garbage, traffic or parking problems), indicating a positive attitude towards the city, are willing to visit the city again. On the other hand, there are visitors who claim that the quality of the hotels, rooms, and accommodation in general is average and these visitors are reluctant to visit Kastoria again. On the contrary, food quality and food places attract visitors to visit the city once again. The above model correctly classifies 9 out of 10 visitors who took part in this survey (see Table 6 and Figure 6). The above characteristics can act as strategy points that should be enhanced by the local authorities and could affect the visitors’ willingness to re-visit the city of Kastoria.

Table 6.

Classification table for willingness to re-visit Kastoria (α).

Figure 6.

ROC for the cut value of the classification table. Note: area = 0.951, S.E. = 0.027, sig. = 0.000.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The present study is based on a survey that took place in Greece in two years, before the economic crisis and in the last year of the crisis. Specifically, the study attempts to outline, through the visitors of a rural border region, its tourism product, the tourism characteristics, and form, as well as compare the differences between the two periods. Kastoria has a rich history, many natural resources, and a long tradition of fur manufacturing and trade, while its lake dominates the landscape of the area and the homonymous city.

During the first years of the economic crisis, Kastoria was trying to develop tourism in order to compensate for the losses of the fur sector, mainly through the strengthening of tourism infrastructures. By 2010, there was a significant increase in the number of the beds with new hotel accommodations and traditional agro-tourism guesthouses. The area’s accommodations appear to be superior in number and quality compared with the other areas in the Region of Western Makedonia, where it belongs.

Visitors of the area during 2008 came mainly from cities and regions relatively close to Kastoria. The visitors were attracted by the fame of fur products made in Kastoria and they had the desire to take an excursion to the lake, the city, as well as the wider area. Moreover, the visitors positively evaluated the area’s accommodations and services, while largely equating the tourism product of the area with agro-tourism and cultural/religious tourism. Before the economic crisis, agro-tourism gained publicity and was almost complete identified with the alternative forms of tourism. The liquidity increases for consumption led to the increased domestic demand for off-season holidays and agro-tourism boost in Greece (BCS—Development and Environmental Consultants 2018). This could possibly justify to a large extent the identification of agro-tourism with the tourism product of Kastoria from the visitors during 2008.

Regarding the visitors during 2017, who appear to be more “aware”, they come from longer distance areas, have relatively lower incomes available to spend, and are more conservative in their rating of tourist accommodations and services. The reduction of travel expenses and the core stay behaviors by the domestic visitors before and during the Greek economic crisis are in agreement with similar studies (Voutskidis 2016; Varvaressos et al. 2017). As for their evaluations concerning the tourism product of the area, they equate it with alternative forms of tourism and, more specifically, with winter tourism, agro-tourism, and eco-tourism, as well as, to a lesser degree, cultural tourism. After 2000, people were informed more about the other forms of alternative tourism, while additional interests were expressed related to tourism forms beyond agro-tourism, even during the economic crisis. This development may have influenced and contributed to the formation and differentiation of the views of the visitors of 2017, who widely identified the tourist product in the form of the winter tourism and eco-tourism.

After the comparison between the two samples, it is concluded that Kastoria has solved or improved problems during the period of economic crisis, related to the attractiveness of the area, such as the cleanliness and organization of its attractions. The Lake of Kastoria is the most significant tourist attraction for visitors in both years, followed by churches and traditional mansions for the pre-crisis visitors, while for the post-crisis visitors, mountains with the ski resort as well as the traditional buildings. Furthermore, fur products remain the basic product for visitors to buy and must emerge into a major tourist factor that should be re-evaluated in the context of a modern tourism strategy. The regression analysis indicated that visitors are willing to visit again Kastoria for a short trip during winter to buy furs. These visitors present a positive attitude towards the City of Kastoria and claim that, in Kastoria, everything is fine regarding garbage, traffic, and parking problems. An issue that should be examined is the service quality of the hotels, rooms, and accommodation in general, as low quality in the accommodation services makes visitors reluctant to visit Kastoria again. According to previous relevant studies in other Balkan countries, rural tourism has positive effects for the rural areas and remains one of the most important axes of rural development (Ibănescu et al. 2018). In these countries, the regional and prefectural authorities seem to follow a focused tourism plan. Bulgaria and Romania have started to follow a management pattern of rural tourism points of interest, in an effort to be specialized in a particular type of tourism such as spa tourism or cultural tourism (Maneva and Stoeva 2014). Moreover, in Italy, they are giving priority to the networking of agro-tourism resources, services’ improvement, and marketing planning for improved performance (Giannetto and Souca 2011; Schiavone et al. 2016).

The above conclusions suggest that the tourism product of Kastoria constitutes a collage of alternative forms of tourism. Nevertheless, within the context of developing a clear and attractive tourism identity of the area, the challenge is to transform this mosaic through a modern strategy into a single tourism image. This project requires both the optimization and interconnection of the tourism forms of the area into a mix that will also include innovative elements and dynamic communication and promotion policies.

Finally, although the research is limited in sample size, it constitutes a springboard for future and in-depth studies focused in the direction of tourism planning for the only region of Greece that has no sea, and specifically to the rural border area of Kastoria, in which the tourism sector dominates over the other Region Units of the Western Makedonia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C.; methodology, A.K. and F.C.; validation, A.K. and F.C.; official analysis, A.K.; research, F.C.; data editing, A.K.; writing—initial preparation plan, F.C.; writing—critique and editing, F.C. and A.K.; supervision, F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Almeida García, Fernando, Maria-Angeles Peláez-Fernández, Antonia Balbuena-Vazquez, and Cortes-Macias Rafael. 2016. Residents’ perceptions of tourism development in Benalmádena (Spain). Tourism Management 54: 259–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthopoulou, Theodosia. 2000. Agrotourism and the Rural Environment: Constraints and Opportunities in the Mediterranean Less-Favored Areas. Tourism and the Environment: Regional, Economic, Cultural and Policy Issues. Edited by Briassoulis Helen and Jan Van der Straaten. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 357–73. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, Mohammed, Khairil-Wahidim Awang, and Othman Nor’ain. 2014. Issues and Challenges in Nurturing Sustainable Rural Tourism Development. Tourism, Leisure and Global Change 1: 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, Carlos Pestana, and Luis Pinto Machado. 2010. The length of stay in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 37: 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BCS—Development and Environmental Consultants. 2018. Integrated Tourism Development Plan of the Region of Dytiki (Western) Macedonia. Kozani: Region of Western Macedonia. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Belias, Dimitrios, Efstratios Velissariou, Dimitrios Kyriakou, Konstantinos Varsanis, Lavrentis Vasiliadis, Christos Mantas, Labros Sdrolias, and Koustelios A. Athanasios. 2017. Tourism Consumer Behavior and Alternative Tourism: The Case of Agritourism in Greece. In Innovative Approaches to Tourism and Leisure. Cham: Springer, pp. 465–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, Natalijia, and Bojan Zečević. 2011. Basic assessment of the rural tourism situation in Serbia. In Public Private Partnership in Rural Tourism. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) ”Sustainable Tourism for Rural Development“. Edited by Svetlana Djurdjevic Lukic. Belgrade: The United Nations, pp. 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, Dimitrios. 2000. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management 21: 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano-Álvarez, Javier, Francisco Maria de la Cruz del Río-Rama, Jose Álvarez-García, and Amador Durán-Sánchez. 2019. Limitations of Rural Tourism as an Economic Diversification and Regional Development Instrument. The Case Study of the Region of La Vera. Sustainability 11: 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamber of Kastoria. 2018. Memorandum on Proposals for the Development of Entrepreneurship of the Regional Section of Kastoria. Kastoria: Chamber of Kastoria. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Chatzikyriakidis, Ioannis. 2019. Endogenous development strategy: The case study of Kastoria-Florina zone. Master’s thesis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Chatzitheodoridis, Fotios, and Achilleas Kontogeorgos. 2020. New entrants’ policy into agriculture: Researching new farmers’ satisfaction. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural 58: e193664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzitheodoridis, Fotios, Anastasios Michailidis, Dimitrios Tsilochristos, and Kazaki Sofia. 2006. Integrated Rural Development Programmes in Greece: An Empirical Approach to their Management, Practice and Results. Aeihoros 5: 58–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzitheodoridis, Fotios, Achilleas Kontogeorgos, and Loizou Efstratios. 2014. The Lean Years: Private Investment in the Greek Rural Areas. Procedia Economics and Finance 14: 137–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzitheodoridis, Fotios, Achilleas Kontogeorgos, Petroula Litsi, Ioanna Apostolidou, Ansatasios Michailidis, and Efstratios Loizou. 2016. Small Women’s Cooperatives in less favored and mountainous areas under economic instability. Agricultural Economics Review 17: 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Coccossis, Harris, and Mary Constantoglou. 2006. The Use of Typologies in Tourism Planning: Problems and Conflicts. Paper presented at 46th Congress of the European Regional Science Association (ERSA) «Enlargement, Southern Europe and the Mediterranean», Volos, Greece, August 30–September 3. [Google Scholar]

- Coccossis, Harris, Tsartas Paris, and Griba Eleftheria. 2011. Special and Alternative Forms of Tourism. In Demand and Supply of New Tourism Products. Athens: Kritiki Publications. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrovski, Darko-Dragi, Todorovića Aleksandar, and Valjarevićb Aleksandar-Djordjie. 2012. Rural Tourism and Regional Development: Case Study of Development of Rural Tourism in the Region of Gruţa, Serbia. Procedia Environmental Sciences 14: 288–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, Larry, Edwards Deborah, Mistils Nina, Roman Carolina, and Scott Noel. 2009. Destination and enterprise management for a tourism future. Tourism Management 30: 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELSTAT—Hellenic Statistical Authority. 2017. Arrivals and Overnights in Hotel Press and Camping Accommodations. Athens: Hellenic Statistical Authority. [Google Scholar]

- ELSTAT—Hellenic Statistical Authority. 2018. Survey of Quality Characteristics of the Domestic Tourists. Athens: Hellenic Statistical Authority. [Google Scholar]

- ELSTAT—Hellenic Statistical Authority. 2019. Tourism 2019. Athens: Hellenic Statistical Authority. [Google Scholar]

- Field, Andy. 2005. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. London: SAGE Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, Alia, and Daniel Felsenstein. 2000. Support for small-scale rural tourism: Does it make a difference? Annals of Tourism Research 27: 1007–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, Chuck, and Eduardo Fayos-Solà. 1997. International Tourism: A Global Perspective. Madrid: World Tourism Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Giannetto, Carlo, and Maria-Louiza Souca. 2011. Rural tourism–improving services as an instrument to obtain sustainable economic activity and overcoming the economic crisis. In Moving from the Crisis to Sustainability: Emerging Issues in the International Context. Edited by Calabro Garcia, D’Amico Augusto, Lanfranchi Maurizio, Maschella Giovanni, Pulejo Luisa and Salomone Roberta. Milano: FrangoAngeli, pp. 313–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, Stefan, Daniel Scott, and Hall Michael. 2020. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GTO—Greek Tourism Organization. 2015. Trends in Tourist Traffic: 2008–2015. Athens: Hellenic Statistical Authority. [Google Scholar]

- Guduraš, Dejan. 2014. Economic crisis and tourism: Case of the Greek tourism sector. Ekonomska misao i praksa 2: 613–32. [Google Scholar]

- Guido Van, Huylenbroeck, and Guy Durand. 2003. Multifunctionality Agriculture: A New Paradigm for European Agriculture and Rural Development: Perspectives on Rural Policy and Planning. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hajimirrahimi, Seyed Davood, Elham Esfahani, Veronique Van Acker, and Witlox Frank. 2017. Rural second homes and their impacts on rural development: A case study in East Iran. Sustainability 9: 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Chenchen, Keunyoung Oh, Qiongyao Zhang, and Choi Yung-Jung. 2013. Understanding the City Brand in the Regional Tourism Market Among College Students. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 30: 662–71. [Google Scholar]

- Iakovidou, Olga. 1997. Agro-tourism in Greece: The case of women agro-tourism co-operatives of Ambelakia. MEDIT 8: 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Iakovidou, Olga, Alex Koutsouris, and Partalidou Maria. 2002. The development of rural tourism in Greece through Initiative LEADER II: The case of Northern and Central Chalkidiki. NEW MEDIT 4: 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ibănescu, Bogdan-Constantin, Oana-Mihalena Stoleriu, Alina Munteanu, and Iatu Corneliu. 2018. The Impact of Tourism on Sustainable Development of Rural Areas: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability 10: 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSETE Intelligence. 2019. The Greek Economy: Development and Economic Policy after Leaving the Memorandums. Athens: Institute of Hellenic Tourism Business Association. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Isaak, Rami Khalil. 2010. Alternative tourism: New forms of tourism in Bethlehem for the Palestinian tourism industry. Current Issues in Tourism 13: 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasundera, J. 2019. Over-Tourism Leads to Under-Tourism. A Luxury Travel Blog.com. Available online: https://www.aluxurytravelblog.com/2019/04/11/over-tourism-leads-to-under-tourism/ (accessed on 29 May 2020).

- Kim, Dohee, and Richard Perdue. 2011. The Influence of Image on Destination Attractiveness. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 28: 225–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kolokontes, Argyrios, and Fotios Chatzitheodoridis. 2008. Unemployment and Development Priorities and Prospects of Western Macedonia Region Greece: A Sectoral Approach. The Empirical Economic Letters 7: 1103–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kolokontes, Argyrios, Vassiliki Lykourinou, and Theodossiou George. 2009. Tourism development of the Florina Prefecture: The visitors’ attitude. PRIME Transaction International Journal 2: 59–74. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Lane, Bernard. 1994. What is Rural Tourism? In Rural Tourism and Sustainable Rural Development. Edited by B. Bramwell and B. Lane. Clevedon: Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Loukissas, Philippos. 1982. Tourism’s regional development impacts: A comparative analysis of the Greek Islands. Annals of Tourism Research 9: 523–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, Roderick. 2018. A Financial and Economic Crisis in Greece. In Eurocritical: A Crisis of the Euro Currency. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 25–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, Donald. 2004. Tourism, Globalization and Cultural Change: An Island Community Perspective. Cleveland: Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Maneva, Savina, and Teodora Stoeva. 2014. Development and management of rural areas in Bulgaria by introducing alternative types of tourism. In Rural Economies in Central Eastern European Countries after EU Enlargement. Edited by Agnieszka Wrzochalska. Warsaw: Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics, pp. 125–31. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, Helena. 2006. Searching for complementarities between agriculture and tourism—The demarcated wine-producing regions of northern Portugal. Tourism Economics 12: 147–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Martín, Jose Maria, Jose Manuel, Guaita Martínez, and Salinas Fernández Jose Antonio. 2018. An analysis of the factors behind the citizen’s attitude of rejection towards tourism in a context of over tourism and economic dependence on this activity. Sustainability 10: 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Martín, Jose Maria, Jose Antonio, Salinas Fernández, Jose Antonio, Rodríguez Martín, and Ostos Rey Maria del Sol. 2020. Analysis of Tourism Seasonality as a Factor Limiting the Sustainable Development of Rural Areas. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 44: 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Garcia, Esther, Josep-Maria Raya, and Majó Joaquim. 2017. Differences in residents’ attitudes towards tourism among mass tourism destinations. International Journal of Tourism Research 19: 535–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Guaita, Jose Manuel, Jose Maria, Martin Martín, Jose Antonio, Salinas Fernández, and Mogorrón Guerrero Helena. 2019. An analysis of the stability of rural tourism as a desired condition for sustainable tourism. Journal of Business Research 100: 165–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastis, Stefanos, and Evaggelos Papanagiotou. 2009. Dimensions of rural sustainable development in mountainous and Less favored areas–Evidence from Greece. Journal of Geographical Institute Jovan Cvijic Sasa 59: 111–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheodorou, Andreas, and Pavlos Arvanitis. 2014. Tourism and the economic crisis in Greece: Regional perspectives. Région et Développement 39: 183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Papatheodorou, Andreas, Jaume Rossello, and Honggen Xiao. 2010. Global Economic Crisis and Tourism: Consequences and Perspectives. Journal of Travel Research 49: 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parallaxi. 2018. SOS from the Hotels of Vasilitsa that are Closing, Parallaxi Magazine [online]. Available online: https://parallaximag.gr/epikairotita/sos-apo-ta-ksenodocheia-tis-vasilitsa-pou-kleinoun (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Park, Duk-Byeong, Yoo-Shik Yoon, and Lee Mo-Sie. 2008. Rural community development and policy challenges in South Korea. Journal of Economic Geographical. Society of Korea 11: 600–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pascariu, Gabriela-Carmen, and Ramona Tiganasu. 2014. Tourism and sustainable regional development in Romania and France: An approach from the perspective of new economic geography. Amfiteatru Economic 16: 1089. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, Douglas. 1989. Tourist Development. Essex: Longman Scientific and Technical Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, Rosaria, Antonia Correia, and Schutz Ronaldo. 2012. Destination Branding: A Critical Overview. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism 13: 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakos, George, and Yiannis Psycharis. 2016. The spatial aspects of economic crisis in Greece. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 9: 137–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillip, Sharon, Colin Hunter, and Blackstock Kirsty. 2010. A typology for defining Agritourism. Tourism Management 31: 754–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintassilgo, Pedro, and Joao-Albino Silva. 2007. Tragedy of the Commons’ in the Tourism Accommodation Industry. Tourism Economics 13: 209–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenow, John, and Gerreld Pulsipher. 1979. Tourism, the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Lincoln: Media Productions & Marketing. [Google Scholar]

- RWM—Region of Dytiki (Western) Macedonia. 2017. Operational Programme of Dytiki Macedonia 2014–2020. Kozani: Region of Dytiki Macedonia. [Google Scholar]

- Sanagustin-Fons, Victoria, Teresa Lafita-Cortés, and Moseñe Jose. 2018. Social Perception of Rural Tourism Impact: A Case Study. Sustainability 10: 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavone, Francesca, Hamid El Bilali, Sinisa Berjan, and Zheliaskov Aleksander. 2016. Rural tourism in Apulia Region: Results of the 2007–2013 Rural Development Programme and 2020 Prospective. AGROFOR International Journal 1: 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, Stefan. 2010. Coping with Externalities in Tourism: A Dynamic Optimal Taxation Approach. Tourism Economics 16: 321–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SETE Intelligence. 2018. The Contribution of Tourism in the Greek Economy in 2017. Athens: Hellenic Tourism Business Association. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Hio-Jung, Hyun-No Kim, and Son Jae-Yung. 2017. Measuring the economic impact of rural tourism membership on local economy: A Korean case study. Sustainability 9: 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Valene. 1989. Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Triarchi, Eirini, and Kostas Karamanis. 2017. Alternative Tourism Development: A Theoretical Background. World Journal of Business and Management 3: 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO—United Nations World Tourism Organization. 2019. World Tourism Barometer. 17 vols. Madrid: UNWTO—United Nations World Tourism Organization, p. 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varvaressos, Stelios, Dimitrios Papayiannis, Pericles Lytras, and Melissidou Sgouro. 2017. Impacts of Economic Recession on Greek Domestic Tourism. Journal of Tourism Research 17: 155–72. [Google Scholar]

- Voutskidis, Athanasios. 2016. The Economic Crisis and their Impacts to the Greek Internal Tourism. Master’s Thesis, School of Social Sciences, Hellenic Open University, Patra, Greece. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, F., W. Frost, and B. Weiler. 2011. Destination Brand Identity, Values, and Community: A Case Study from Rural Victoria. Australia Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 28: 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S., D. R. Fesenmaier, J. Fesenmaier, and J. C. Van Es. 2001. Factors for success in rural tourism development. Journal of Travel Research 40: 132–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Eunju, Hyelin Kim, and Uysal Muzaffar. 2015. Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research 50: 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTTC—World Travel & Tourism Council. 2016. It’s Not Sustainable Tourism … Just Tourism! Available online: https://medium.com/@WTTC/it-s-not-sustainable-tourism-just-tourism-e480e3e1f3fe (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Zacharatos, Gerasimos, Maria Markaki, and Soklis George. 2014. The Regional Characteristics of Tourism in Greece: A Cluster Analysis. Paper presented at 18th Scientific Conference of the Association of Greek Regional Scientists, Technological Educational Institute of Crete, Heraklion, Greece, May 15–17. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).