Abstract

This analysis highlights the significant role that domestic actors play in determining the outcomes of economic sanctions. It models the behavior of the main opposition party during an economic sanction episode, and introduces two commonly used variables when considering the effectiveness of economic sanctions—regime type and issue type—from a different perspective. Using Bayesian probabilities and a two-stage game-theoretic approach, the analysis finds that states are more likely to impose economic sanctions related to security issues rather than to nonsecurity issues. The tendency to impose sanctions to coerce action on security-related issues is higher when opposition parties in the sanctioning state object to the sanctions. The findings demonstrate that sanctions are more effective when they are supported by the opposition in sender states, as well as target states. Consistent with the literature, this analysis finds that sanctions are more effective when they are targeted against democracies. The game results indicate that sanctions are more successful when they relate to security issues. This paper supplies policymakers with a simple criterion for economic sanctions successs comprised of the support of the opposition within the sender state, that the issue should be of high stakes, and there is support for the economic sanctions from a viable opposition within the target state.

JEL Classification:

F13; F51; F59

1. Introduction

Economic sanctions cost the United States (US) between $15 and $19 billion in potential exports annually, leading to a potential loss of 200,000 export jobs (Hufbauer et al. 1990). Morgan et al. (2014) report 1412 threatened and imposed economic sanction episodes between 1945 and 2005. The United States accounts for approximately 48% of sanctioning episodes, and continues to rely heavily on the foreign policy tool under the current Trump administration. This provides merit to the investigation of economic effectiveness, given their colossal economic, social and cultural repercussions (Morgan et al. 2014).

Regime type determines the set of preferences, options and utilities that the ruler and his/her support circles pose during an economic sanctions episode. Regime type refers to the form of government or sets of institutions ruling a nation-state. There is considerable variation in regime types, with liberal democracies falling on one end of the spectrum and personalist dictatorships occupying the other. For the purpose of this analysis, regime type concerns the question of whether a state is democratic or authoritarian. The assumption is that the behavior of elites within an authoritarian regime will follow from motivations that are markedly different from the motivations that drive behavior within democratic states (de Mesquita et al. 2005). Dictators with hybrid electoral regimes and liberal/semi-liberal economies will utilize different tactics to rally support than those used within personalist regimes.

Because of this, the regime type within a target state facing economic sanctions will be important to determine the actions that will be taken by the dictator, the ruler or the government.

The justification for focusing on issue type stems from the survival of the state logic. If the behavior motivating the enactment of an economic sanction pertains to the security of the target state or regime, the state would not compromise and would maintain its position. If the issue is non-security-related (e.g., the release of political prisoners on an outdated conflict), the state is more willing to compromise. Therefore, the type of the political issue or demand will determine the courses of action to be taken by the target state.

The role of domestic players in sanctions’ effectiveness has been controversial and puzzling. Allen (2008) finds that despite the increase of antigovernmental activity within target states due to sanctions, such political pressure is mitigated by domestic political structures. In contrast, with the use of count models of protest activity, Grauvogel et al. (2017) concludes that threats of sanctions act as signals for would-be protesters, and spark social unrest within targets that increase sanctions’ likelihood of success. Onder (2019) finds support for the association between domestic support for economic sanctions within targets and sanctions’ effectiveness. The present study provides an answer as to how the opposition within target states assist senders in fulfilling their objectives through economic sanctions.

The significance of domestic players within the sender states of economic sanctions has received attention. William and Lowenberg (1988) argue that advocacy for sanctions by domestic pressure groups within sender states increases the likelihood that the sanction will have the intended effect. Mclean and Roblyer (2016) suggest that public opinion in sender states matters in the initiation and effectiveness of sanctions. The public is more likely to support sanctions that promote humanitarian objectives and would lend political and economic advocacy to its government action. Conversely, McLean and Whang (2014) argue that, notwithstanding domestic public support for sanctions or their objectives within the sender state, public interest group preferences could limit the success of sanctions. Interest groups that are closely tied with targe-states’ economies do not prefer policies that engender losses to their assets; because of this, these groups are shown to lobby their governments to issue sanctions that do not cause the sending state to incur severe losses. This results in a lower probability that any sanction to be levied will bring about its intended effect.

A further conundrum regards the disagreement on whether economic sanctions work better against dictatorships (non-democracies) or against democracies. One line of literature argues that economic sanctions are more effective against personalist dictatorships and monarchies compared to a single-party rule authoritarian or military states (Escribà-Folch 2012). Similarly, Kaempfer et al. (2004) argue that sanctions decrease the budget available to dictators to repress opposition or buy out loyalty, thereby exerting pressure on dictators to amend their policies. Allen (2005) concludes that regardless of the sanctions’ duration, democratic targets suffer more from sanctions compared to dictatorships. On the other end of the debate, Major (2012) demonstrates that the recent literature on economic sanctions concluded the higher resilience rate of dictators in the face of gruesome economic sanctions compared to democracies. Nossal (1999) argues that sanctions are more effective against democracies due to their opposition’s ability to influence political outcomes compared to dictatorships.

A less clear argument has been purported for the significant effect of issue salience on economic sanctions’ outcomes. Ang and Peksen (2007) point out that issue salience influences outcomes, and if issue salience asymmetry favors the sender over the target, the effectiveness of sanctions improves dramatically. Wallace (2013) argues that the issue type matters in the threatening and imposition of sanctions. Democracies are more likely to sanction each other on nonsecurity-related issues, and are less likely to coerce each other economically on security-related matters. Security-related sanctions involve high politics, where the issue is concerned with disputes such as weapons proliferation, denial of strategic materials and territorial disputes. Conversely, nonsecurity-related sanctions involve low politics, where the issue is concerned with human rights, environmental policies and trade policies (Wallace 2013). The arguments suggesting a link between issue salience and sanction effectiveness do not specify the mechanisms by which the two constructs are related.

Studies addressing this association do not account for the potential roles of the party in government, opposition parties, public opinion, or pressure groups within the sender and the target.

This analysis highlights the role of domestic actors in determining the effectiveness of economic sanctions. Using a two-stage, game-theoretic approach on the use of economic sanctions, it is argued that sanctions are more effective when the opposition in sender states supports the sender state’s government’s decision to threaten or impose sanctions. Sanctions’ effectiveness decreases when the opposition in target states supports the governmental action of the target state. The model suggests that under subgame perfect equilibrium, the opposition within the target state displays a greater influence on the outcome of any sanction event than the opposition within the sender state. A mechanism is proposed to explain this result—opposition in targets offer more political clout to the government to rally popular support that is likely to mobilize economic resources to address inadequacies created by sender sanctions.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

The effectiveness of economic sanctions has received considerable attention. Hufbauer et al. 1990) show that 34% of 115 cases (representing 40 sanction episodes) were effective to some degree. Pape (1997) subsequently criticizes their approach and indicates that only 5 out of the 40 cases were real successes (a success rate of about 5% for the entire 115 cases). Conventional wisdom suggests a general ineffectiveness of economic sanctions. Only a few studies report potential positive gains, like preventing long committed wars and thwarting military expansions by aspiring leaders or states (McCormack and Pascoe 2017). However, some analyses focus on smart sanctions that are characterized by a high likelihood of success (e.g., serious sender commitment, an invocation of international support, targeting core economic sectors within the target and the enactment of sanctions as opposed to merely threatening them) (Zarate 2013; Leoffler 2009; Eckert 2008). However, these studies commonly fail to examine the interaction of domestic opposition within sanctioning states and target states together on the success or failure of a sanction episode.

2.1. Success of Economic Sanctions

Evidence for the success of economic sanctions has been controversial. While many studies have been pessimistic about sanctions and their effectiveness, a few analyses find that sanctions work especially if they are more targeted. Inspecting the descriptive evidence confirms this picture. In the most updated data on sanctions, as seen in Table 1, the TIES dataset v4.0 shows that sanctions succeed in 37.5% of observed episodes using the most restrictive definition of success, and in 56.3% of observed episodes under the most relaxed definition of success (missing cases removed N = 1024) (Morgan et al. 2014).

Table 1.

Sanctions’ Success Ratios (Morgan et al. 2014).

The prevailing view is that economic sanctions do not work (Kaplowitz 1998; Doxey 1971; Galtung 1967). However, sanctions are foreign policy instruments that are being used more frequently over time, and this is true especially of sanctions enacted by Western states in attempts to force target states to change their behavior. Sanctions mostly fail to achieve these goals, and often civilians suffer as a result of them (Pape 1997; Hufbauer et al. 1990; Cortright and Lopez 2000). The near-consensus in the literature reflects the idea that sanctions are not only unsuccessful, but that they may also be counterproductive (Bienen and Gilpin 1980). Senders do not commit sufficient resources to support their threatened and imposed sanctions, and this weakens their effectiveness. States can sanction each other for symbolic reasons, and they do not signal a willingness to act with the resolve needed to ensure the attainment of the goal that motivated the sanctions (Lindsay 1986).

2.2. Domestic Actors’ Response to Economic Sanctions

The public choice perspective on economic sanctions focuses on the role played by pressure groups within the sender and the target states. William and Lowenberg (1988) argue that the most effective sanctions are characterized by income losses on the part of target states’ groups benefiting from their governments’ policy. This implies that a shift in the position of pressure groups in support of sender state government policy objectives leads to more effective sanctions, given the preference shift which domestic groups undergo within the target. Kirshner (1997) points out that the most successful sanctions are those that focus upon the core groups within the target state that the target government relies on for political and economic support. Therefore, if these groups do not support their own dictator or government in the target, they are more likely to shift interests in favor of the state government contingent upon their economic benefits. Escribà-Folch and Wright (2010) suggest that sanctions are more effective in targeting monarchs and personalist regimes because they incur greater losses to the specific types of revenue that would be used to fund their patrons and supporters at home. This logic implies that if the monarchs and personalist regimes garner sufficient economic and political support from pressure groups within their polities, they will not concede to the goals of an imposed sanction because they would maintain resources sufficient to to sustain their de-incentivized objectives.

Most of the economic sanctions are imposed by democracies against dictatorships. This allows researchers to examine the varying responses of regimes to survive in light of economic coercion. Escribà-Folch and Wright (2010) argue that sanctions are less effective against single-party authoritarian regimes and military ruling dictatorships when compared to monarchies or personalist regimes. When a state is targeted for economic sanctions, Wright and Escribà-Folch (2012) show that that authoritarian parties will protect the interests of elites and the ruling regime by lending political support to its policies. In his social conflict analysis, Jones (2015) suggests that if authoritarian states exhibit a vibrant middle class, their regimes will find it more difficult to maintain power following a sanctions episode without changing the sanctioned behavior. This creates a condition under which the sanction is more likely to achieve its intended goal.

Some attention has been also paid to the association between domestic and international political pressure and sanctions’ effectiveness. Allen (2008) suggests that for sanctions to be effective in autocratic targets, an international coalition needs to exert political costs on the ruling regime of the target. While domestic antigovernment activity increases with the initiation of sanctions, domestic political structures subsume their effects, mitigating their influence on changing the policy of the regime. In an earlier analysis, Allen (2005) discusses that domestic structures influence the success and failure of sanction episodes. Political agreement among domestic decision-makers on the sanction episode within the sender makes them even more likely to be successful. However, when groups within the target state are able to effectively shape public opinion in opposition to the sanction, the sanction becomes less likely to achieve its intended aim. (Onder 2019).

H1:

Sanctions supported by the opposition are more effective.

2.3. Regime Type and Sanction Success

An extensive line of research examines the association between target regime type and sanction effectiveness. Peksen (2019) argues that regime type influences the rate of economic sanction effectiveness. Single-party governments and military dictatorships are more likely to resist sanctions and to endure costs when compared to personalist regimes. This is due to the institutional advantage endowed by the former (e.g., more resources, a strong state apparatus and better bureaucracies and alliances). Sanctions levied against personalist regimes succeed at a rate similar to sanctions waged against democracies. This, in turn, suggests that sanctions are more likely to be effective against democratic regimes than against institutionally rich dictatorships.

Another line of argument suggests that sanctions work better against democracies than against dictatorships (Brooks 2002; Kaempfer et al. 2004; Major 2012). This argument explores the ability of a dictatorial regime to sidestep the effects of losses targeted both against the leader personally and against the regime’s political and economic cliques. Dictators can do this in a variety of ways, including the relallocation of wealth away from their opponents and the masses, and shifting it toward themselves and their supporters. This ability is absent for democratic leaders, who are restrained through many institutional mechanisms to alter the distribution of economic resources or wealth. The cost of sustaining popular support through the provision of selective goods is too high, because the popular base for democratic leaders is sufficiently large. Democratic leaders cannot simply repress en maase due to deeply rooted social norms preventing such a practice.

H2:

Sanctions against democracies are more effective compared to nondemocracies.

2.4. Issue Salience Association with Sanctions’ Success

A considerable amount of research links issue salience to economic success. Effective sanctions often aim to achieve a more narrowly targeted objective, such as the release of a hostage or prisoner; those with the objective to coerce broader policy objectives like demilitarization or nuclear non-proliferation are less likely to achieve their goals (Lindsay 1986; Hufbauer et al. 1990; Ang and Peksen 2007). Threating or imposing sanctions with the goal to compel change to a broader policy is more likely to result in harm to the local population in the target state (Wood 2008; Peksen 2009; Peksen and Drury 2010; Adam and Tsarsitalidou 2019). Another argument states that economic sanctions are more effective in achieving targeted objectives, such as restricting the target government or elites from resources. Such targeted sanctions are capable of achieving symbolic objectives like derailing popular support for dictators or mobilizing international community against an oppressive practice of the target regime (Lindsay 1986; Whang 2011; Giumelli 2011; Biersteker et al. 2016).

Wallace (2013) argues that if the divisive issue is related to security matters, democracies will not impose sanctions on other democracies. On the contrary, if the issue at stake is a nonsecurity-related matter, then democracies may impose sanctions on other democracies. From the evidence available, it seems that economic sanctions are more effective when issue salience is very high for the coercer and the differential in salience is high between the sender and target. Overall, if the issue is of extreme importance to the sender (such as in security-related matters) and the asymmetry of salience between the sender and the target is high, perceptions diverge in favor of the sender, and sanctions are likely to be more effective.

H3:

Economic sanctions are more likely to be imposed with the goal to coerce action on security issues than to coerce action on nonsecurity issues.

H4:

Sanctions imposed with the goal to coerce action on security issues are more effective than those enacted with the goal to coerce action on nonsecurity issues.

3. Methodology

In this study, game theory is used to analyze the strategic interaction between states in economic sanctions episodes. States are modeled as rational decision-makers (Tsebelis 1990). The study contributes theoretically to the empirical studies on economic sanctions by showing the underlying interaction between sender and target states.

3.1. Description of a Basic Economic Sanctions Game

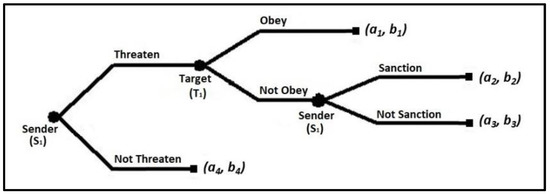

An economic sanction episode is a transaction between two parties, the sender and target states, as seen in Figure 1. The sender has two possible outcomes at the start of the interaction: to threaten initiating sanctions or not to threaten the target. Once the sender makes the threat, the target either obeys or does not obey the threatened sanctions. If the target does not obey, the sender must sanction or not sanction. This is a simplified case where there is no opposition in the sender and the target states.

Figure 1.

The Extensive Form of the Models without Opposition in General.

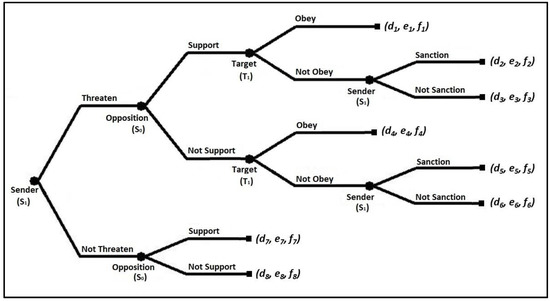

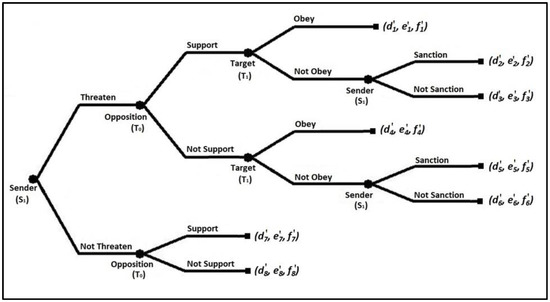

Figure 2 and Figure 3 maps the introduction of the opposition in the sender state and the target state. In cases where opposition is at play, each actor has two players: the government and the opposition. The sender has two classical outcomes: to threaten with sanctions or to uphold the status quo (not to threaten). The opposition then has two possible outcomes: supporting or not supporting (opposing) the sanctions policy of their governments. Given either of the opposition choices, the target state either obeys or challenges the sanctions. If the target state does not obey the threat, the sender’s government either sanctions or does not sanction the target state.

Figure 2.

Extensive Form of the Models with Opposition in the Sender State.

Figure 3.

Extensive Form of the Models with Opposition in the Target State.

3.2. The Games in General and Sequence of the Moves

3.2.1. The Game with no Opposition Party (Non-Democracy v. Non-Democracy)

The players are the sender state S1, the opposition party in the sender state S0, the target state T1 and the opposition party in the target state. Below is the sequence of moves for sanction episodes between a sender state where there is no opposition party in both the sender and target states:

- The sender S1 moves first by choosing either to threaten or not to threaten economic sanctions on a target state, T1.

- After observing the sender’s S1 behavior, the target state T1 either obeys S1’s terms or does not obey its demands. If T1 obeys, then the game ends peacefully.

- If T1 chooses not to obey, then S1 chooses either to sanction (SA) or not to sanction (SN).

3.2.2. The Game with an Opposition Party in Sender State (Democracy v. Non-Democracy)

If there is opposition in a sender state, the opposition plays after the government in the sender state that chooses to threaten economic sanctions. Below is the sequence of the moves for sanction episodes between sender S1, opposition S0, and target T1:

- The sender state S1 moves first by choosing either to threaten economic sanctions on a target state T1 or chooses not to threaten economic sanctions.

- The opposition party S0 in the sender state moves next by selecting options either to support or not to support the government’s policy.

- After observing the sender’s (S1) and the opposition’s (S0) strategies, the target state T1 either obeys or does not obey the sender state. If T1 obeys, then the game ends peacefully.

- If T1 chooses not to obey, then S1 chooses either to impose sanctions or not to impose sanctions.

3.2.3. The Game with an Opposition Party in Target State (Non-Democracy v. Democracy)

If there is opposition T0 in a target state T1, T0 plays after T1. Below is the sequence of the moves for this case:

- The sender state S1 moves first by choosing either to threaten or not to threaten economic sanctions.

- The target state T1 moves next by selecting options either to obey or not to obey.

- After observing S1’s and T1’s strategies, the opposition in target T0 either supports or does not support the target state.

- If T1 chooses not to obey, S1 chooses either to sanction the sanctions, or not to sanction after T0′s strategies.

The games above are applied to two different settings: economic sanctions related to security matters, and economic sanctions related to nonsecurity issues. Since the literature, as shown above, has found that issue type and salience determine a portion of economic sanctions success, these have been performed. There is an expectation that the sanctions will yield differing probabilities contingent on the issue type involved. Table 2 presents the categorization of security and nonsecurity issues and provides examples for illustration. Categories were developed using Wallace’s (2013) categorization of issue types (whether sanctions are a result of security-related or nonsecurity-related concerns) in relation to economic sanctions from the TIES dataset. This typology allows a perspective regarding each states’ behavior in certain types of disputes. Note that the TIES dataset issue codes are presented in parentheses. The TIES dataset provides up to three primary reasons for economic sanction cases, and this study incorporates them when calculating conditional probabilities.

Table 2.

Types of Issues Precipitating Economic Sanctions.

Table 3 depicts ten scenarios analyzed in this paper by using game theory. Notice that five scenarios involve security-related issues, and five scenarios involve nonsecurity-related issues. First row models (model 1 and model 3) involve games where there is no opposition in sender and target states, while the models in other rows involve games with supporting or non-supporting opposition.

Table 3.

Models for the Comparison of Sanctions for Security and Nonsecurity Issues.

The dependent variable is the utility obtained by players from the use of strategies during economic sanction episodes. Independent variables are: (a) the sanctions’ intensity stage, which is a dummy variable where economic sanctions are threatened or imposed, (b) the conflict type, which is a dummy variable where it is either a security- or nonsecurity-related interstate conflict, and (c) the regime type, where there is strategic opposition (democracy), and there is no strategic opposition (non-democracy). Units of analysis are observations on a dyad (sender-target) experiencing economic sanctions.

There are three different types of dyadic interactions examined in models; there are: (1) non-democracy v. non-democracy, (2) democracy v. non-democracy, and (3) non-democracy v. democracy. In order to keep the models parsimonious, this study does not consider democratic interaction. However, model results will be intuitive for democratic dyadic relationships.

The influence of the electorate (public opinion) on decision-makers (S1, S0, T1, and T0) is important in specifying payoffs for each actor. As the sender state controls the initiation and timing of the economic sanctions, the target state (T1) can only respond to these steps (Major 2012). If the sender state is a democratic regime, the electorate in the sender state plays an important role in influencing the decision-makers’ (government’s and opposition’s) determination of the expected utility of the sanctions, since the electorate can vote to remove them from their office.

Kaplowitz (1998) indicates that economic sanctions are helpful in creating cohesion among different political groups in the target state, with leaders being able to manipulate any causes of economic hardships resulting from the sanctions, blame the sender state for their misbehaviors, and influence the electorate to rally against the sender state. For non-democratic targets, regardless of whether the target state has an opposition party or not, the imposition of sanctions results in cohesion instead of fragmentation between the different groups. However, when the targets are democracies, it is important to analyze the role of their opposition on economic sanctions outcomes.

3.3. Payoffs

The Threat and Imposition of Economic Sanctions (TIES) dataset v.4.0 (Morgan et al. 2014) is used to calculate Bayesian probabilities. Issue type (security or nonsecurity) and crisis intensity (threatening–imposition stages) are considered when calculating the conditional probabilities. The following assumptions are used to simplify the calculation of the players’ payoffs:

- Assume that the cost of economic sanctions, both for security and nonsecurity-related issues, is ci. Here, cs1 is a value from [0, Cs1] for the sender state S1 and cT1 is the cost of sanctions, which is a value from [0, CT1], for the target state T1.

- Assume that the utility obtained from sanctions, related to security issues, is uisec, while uinsec is for the utility obtained from sanctions related to nonsecurity issues.

- The probability of economic sanctions imposition is p.

- The ultimate payoffs for players are the difference between the utility obtained from economic sanctions minus the cost of the sanctions: uisec*p-ci (for sanctions related to security issues) or uinsec*p-ci (for sanctions related with nonsecurity issues).

- For simplicity, the cost is assumed to be a constant value, and the utility of sanctions is a function F(x). For sanctions related to security issues, uS1sec ~ F(uS1sec) on [p-Cs1, p] for S1; uT1sec ~ G(uT1sec) on [p-CT1, p] for T1. For sanctions related to nonsecurity issues, uS1sec ~ F(uS1nsec) on [p-Cs1, p] for S1, and uT1nsec ~ G(uT1nsec) on [1-p-CT1, 1-p] for T1.

- The expected utility of players for games on security-related sanctions is a function of uisec where f(uisec) = (uisec*p-ci). Similarly, the expected utility of players for games on nonsecurity-related sanctions is a function of uinsec, where f(uinsec) = (uinsec*p-ci). For simplicity, uisec and uinsec are normalized to 1.

- The sender and its opposition know their cost (ci), and the target and their opposition know their cost (ci). Therefore, it is assumed that players know their costs, but not that of their opponent(s).

- Credit that the opposition gets for supporting the current sanction policy is denoted as q, and reduces the sender state’s (S1) payoff by a factor of (1-q).

- Reputation loss by the sender state for backing down and/or the target state for obeying is known as audience cost, and is coded as −a for actors. Conversely, opposition in sender state and target state, which gains utility from their governments’ reputation loss, is coded as a.

4. Results

Table 4 shows the TIES dataset delineated according to issue type and sanctions policy intensity. The TIES dataset indicated that of 348 cases, where threatened sanctions were related to security issues, 185 cases escalated to the imposition stage. In the second category, 722 cases were sanctions related to nonsecurity issues, with 333 cases escalating to the imposition stage. The probability of a threatened sanction related to security issues is thus 348/(348 + 722) = 32%, and the probability of a sanction related to nonsecurity issues is 722/(348 + 722) = 67%.

Table 4.

Summary of the TIES Dataset v4.0.

Table 5 presents the Bayesian probabilities for the ten scenarios (events) modeled. Row one compares models 1 and 4, which indicate that the probability of a sender state without opposition to imposing economic sanctions on security issues is 0.53 (compared to 0.45 on nonsecurity issues). The percentage difference is almost 18% in favor of security-related matters. This result presents the evidence supporting the third hypothesis that states tend to impose economic sanctions on security issues more than on nonsecurity issues.

Table 5.

Bayesian Probabilities for four models.

The second row also compares model 1 and model 4, suggesting that the probability of a sender state without opposition backing down from imposing economic sanctions over security-related issues is 0.46 (compared to nonsecurity at 0.55). The percentage difference between both probabilities is 20%, favoring sanctions related to nonsecurity-related matters.

These first two rows demonstrate the case where sender states are more likely to impose economic sanctions on security-related issues. Sender states are less likely to back down, given that the issue at hand is related to security matters. On the other hand, senders without opposition (nondemocratic regime types) are less likely to impose sanctions given non-security issues, and are more likely to back down on nonsecurity issues.

Cases for which sender governments garner opposition support for sanctions are presented in rows three and four. Model 2 (+) and model 5 (+) compared in row 3 suggest that if sender states threaten economic sanctions while the opposition is in support, the probability of imposing the sanctions does not change with respect to an issue type. The fourth row, comparing model 2 (+) and model 5 (+), suggests that the probability of backing down for senders with support from their opposition for sanctions does not change since the opposition lends support to the sanctions. Rows 3 and 4 indicate that if the opposition supports the sending government, governments tend to impose sanctions generally and rarely back down. Therefore, for the target state, observing the strategic interaction between actors in the sanction sending state is an important source of information on selecting its decisions.

Rows 5 and 6, which compare model 2 (−) and model 5 (−), where there is a non-supporting opposition party in the sender state. The fifth row suggests that the probability of senders imposing sanctions when the opposition does not back the government over security-related issues is 0.34 and 0.30 for nonsecurity issues (a percentage difference of 13% favoring security-related issues). Row 6 also suggests that the probability of senders backing down from imposing sanctions on security issues (given that the opposition does not support the governments’ action), is 0.63 and 0.70 for nonsecurity issues, giving a percentage difference of 11% favoring nonsecurity-related issues. This scenario shows that senders have a higher probability of imposing sanctions on security-related issues despite a lack of support from their opposition. Similarly, senders have a higher probability of backing down when nonsecurity-related issues are involved, and the opposition does not support the threatened sanctions.

Rows 7 and 8 in Table 5 above compare model 3 (+) and model 6 (+), and suggest that if there is a supporting opposition in the target state, the probability of sender states to impose threatened sanctions is 0.24 for security issues and 0.51 for nonsecurity issues. Similarly, if there is a supporting opposition in the sender target state, the probability of sender states to back down after threatening sanctions is 0.76 for security issues and 0.78 for nonsecurity issues. These results indicate that sender states tend to impose sanctions related to nonsecurity issues more than security issues when there is a non-supporting opposition in the target state. Besides, sender states tend to back down for security-related economic sanctions when there is a supporting opposition in the target state.

Rows 9 (−) and 10 (−) compare the case where there is a non-supporting opposition in a target state by comparing model 3 and model 6. The results show that the probability of sender states to impose threatened sanctions is 0.35 for security issues and 0.38 for nonsecurity issues. Besides, the probability of sender states to back down after threatening sanctions is 0.66 for security issues and 0.59 for nonsecurity issues. Similar to the results above, sender states tend to back down sanctions related to nonsecurity issues more than security issues when there is a non-supporting opposition in the target state. However, sender states tend to impose for security-related economic sanctions and for nonsecurity-related issues at an almost similar level of probability.

Comparison of rows 7, 8, 9 and 10 indicates that the probability of a sender state to de-escalate the level of crisis from the threatening stage is dramatically higher for both security- and nonsecurity-related issues when there is a non-supporting main opposition party in a target state. However, when senders impose sanctions, they tend to impose such sanctions on nonsecurity (p = 0.51) issues rather than security issues (p = 0.24).

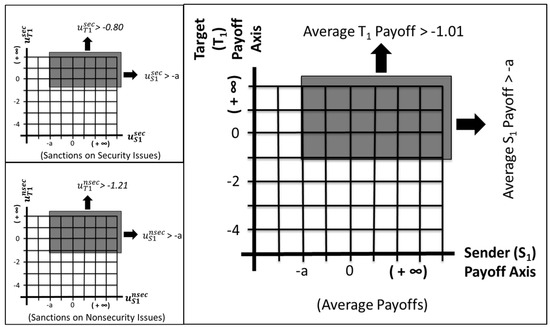

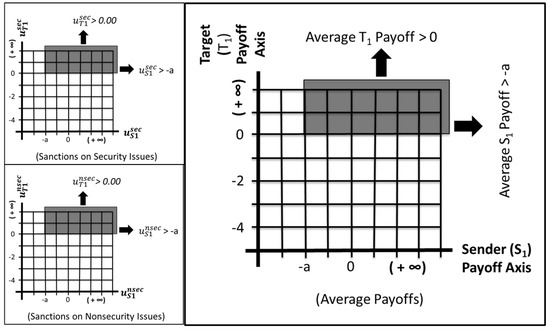

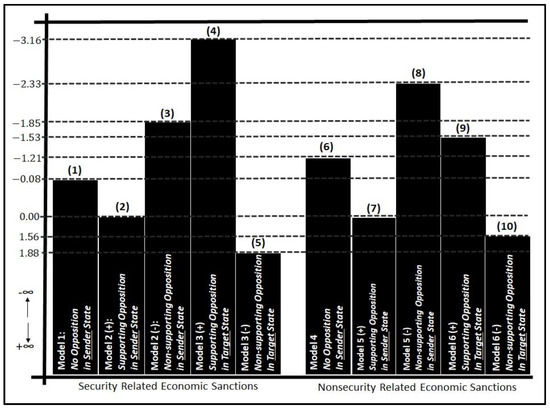

Figures in the next pages present payoff ranges at subgame perfect equilibrium conditions for both sender state and target state. The sender state payoff range is kept fixed at any value larger than −a across all models. This helps to see the variation in target state payoffs across models to observe the influence of economic sanctions on target states.

Note that if the target state has obtained the higher covered area, then the more utilities. This study assumes that the lower the target payoff (lower ranges), the more efficient are the economic sanctions. Figure 4 presents the payoff ranges for the sender and target states in models 1 and 4.

Figure 4.

Payoffs for sender and target (no opposition).

For the target state, seen above in Figure 4, the payoff score is any value bigger than −0.80 for sanctions related to security issues, and is any value bigger than −1.21 for sanctions related to nonsecurity issues. Two covered areas on the left suggest that the target state receives lower payoffs for economic sanctions related to security issues. The covered area on the right shows that when a sender state with a nondemocratic regime type imposes economic sanctions, the target state payoff becomes any value greater than −1.01, irrespective of the issue type.

Figure 5 presents the payoff distributions for the sender and target states for model 2 (+) and model 5 (+). In this game, the sender state has a supporting opposition (S1 is a democracy), and the target state does not have an opposition party (T1 is a nondemocracy). After keeping the sender payoff range fixed at uS1sec,nsec > −a, the target state payoff is uT1sec > 0 for sanctions related to security issues, and uT1nsec > 0 for sanctions related to nonsecurity issues. Results in the figure depict that when opposition within a sender state supports the government, a nondemocratic target state receives the same payoff scores irrespective of the issue type.

Figure 5.

Payoffs for Players when There is a Supporting Opposition in the Sender State.

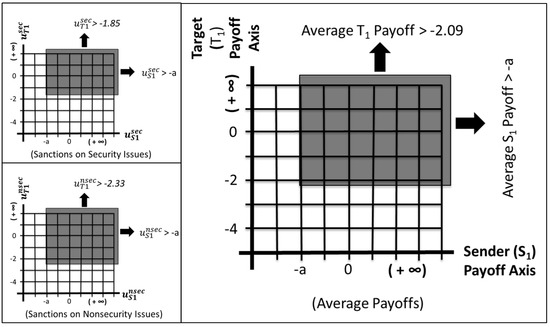

Figure 6 depicts the payoff distributions for the sender and target states in model 2(−) and model 5(−), where the opposition opposes the sender state government’s sanctioning policy. When the sender state payoff is kept fixed at uS1sec > −a, the target state payoff becomes uT1sec > −1.85 for sanctions related to security issues, and uT1nsec > −2.33 for sanctions related to nonsecurity issues. In this game, the target state receives a lower payoff for sanctions related to security-related issues. However, as seen from the comparison of average payoffs, the target receives a higher payoff under the condition of a non-supporting opposition as opposed to the condition of a supporting opposition in a sender state.

Figure 6.

Payoffs players when there is a non-supporting opposition in the sender state.

Comparing average payoffs for the target state in Figure 5 and Figure 6, it is observed that the target state receives a lower level of payoffs when the opposition party supports the sender government. Therefore, sanctions work better when there is a supporting opposition in the sender state, which result provides evidence for the support of the first hypothesis, which states this. Moreover, comparison of payoffs with respect to issue types provides evidence for the support of the fourth hypothesis, which notes that economic sanctions related to security issues work better than sanctions on nonsecurity-related issues. Results show that sender states receive greater payoffs resulting from security-related sanctions than from nonsecurity-related sanctions when there is a non-supporting opposition in the sender state. The issue type is irrelevant when the opposition party supports the government in the sender state because target state payoffs do not change.

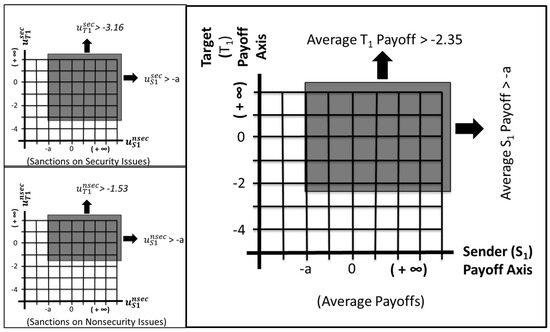

Figure 7 presents the payoff distributions for the sender and target states in model 3 (+) and model 5 (+). In this game, the sender (S1) does not have an opposition party (S1 is a nondemocracy), whereas the target (T1) has an opposition party (T1 is a democracy). The opposition party in the target supports their government’s counter-sanctions policy against the sender state. When the sender state payoff is kept fixed at uS1sec > −a, the target state payoff becomes uT1sec > −3.16 for sanctions related to security issues, and uT1nsec > −1.53 for sanctions related to nonsecurity issues. In this game, the target state with a supporting opposition gets the highest levels of payoffs for sanctions connected to security-related issues. This shows that when a democratic target state with a supporting opposition party can use the rally around the flag effect policy successfully, economic sanctions bring out the worst outcome for the sender state.

Figure 7.

Payoffs for players when there is a supporting opposition in the target state.

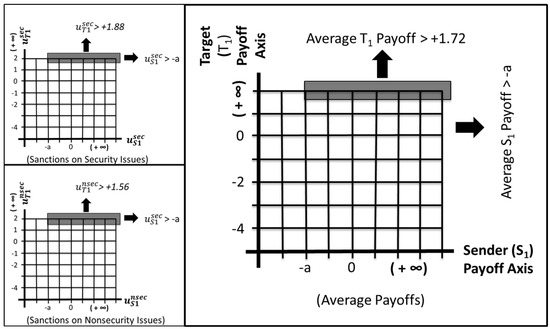

Figure 8 depicts the payoffs for the sender and target states in model 3 (−) and model 5 (−). Similar to the game above, the sender is a nondemocracy, whereas the target is a democracy. The opposition party in this target does not support their government’s counter policy. According to the payoff results, the target state gets a payoff range of uT1sec > +1.88 for sanctions related to security issues, and uT1nsec > +1.56 for sanctions related to nonsecurity issues. In this game, although the target state with a non-supporting opposition gets across lower levels of payoffs for sanctions on security issues than nonsecurity ones, the difference is very small. The target state gets the lowest level of payoffs when there is a non-supporting opposition. Therefore, when a target state is a democracy, but opposition to the sanction is not successfully fostered within the electorate, economic sanctions bring out better outcomes for the sender state, given the comparison of average payoffs from Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Payoffs for players when there is a non-supporting opposition in the target state.

Comparison of Figure 7 and Figure 8 provides mixed evidence for the support of the second hypothesis, which notes that economic sanctions are more effective against democracies compared to non-democracies. As seen from the figures, the average payoffs for the target state are much lower when there is a non-supporting opposition party. Conversely, figures comparison shows that the target state gets a higher level of payoffs when the opposition party supports the government in the target state.

Figure 9 presents the summarized target state payoff ranges for the ten scenarios derived from the six models. Results show that the role of opposition in the target state is more important than the role of the opposition party in the sender state, especially for economic sanctions in general (see column 4).

Figure 9.

Overall Target Payoff Ranges (Sender payoff ranges held fixed at values bigger than −a).

The overall model results in Figure 9 show that the sender’s opposition party can send credible signals to the rival state in a crisis by creating a second information source that confirms the government’s determination. In the subgame perfect equilibrium (SPE) condition, the opposition’s confirmatory signal changes the probability of sanctions imposition. The opposition party can strengthen or weaken the credibility of economic sanctions imposed by exploiting the audience cost. The strategy of an opposition party in a sender state is an important factor for the target state’s strategies against the sender state. Similarly, the strategies of the opposition party in the target is an important indicator of the sender state’s follow-up strategies. Therefore, the success of the economic sanctions depends on the degree of commitment by the government, together with that of the opposition party. As a result, when there is a strategic opposition in a sender state, this democratic nature of the sender state could force the sender state’s government to be more selective about imposing economic sanctions. Both the government and opposition can be pushed or punished by the electorate when the government pursues an international economic sanction policy, because sanctions should be utilized as an effective foreign policy tool.

5. Discussion

This paper explains the mechanism linking sanction effectiveness to the opposition’s behavior within the target, as well as the sender states. In an episode where the opposition within the sender lends support to its government in its sanctioning endeavors, the sanctions are more likely to work. The pressure groups’ effect furnishes the logic behind this relationship. The target state will be more fearful once it observes a hard commitment to sanctions. Pressure groups in target states can assist the sender government in restricting resources for the dictator or the core regime within the target to finance their course of action, whether cooptation or repression. By the same token, if the opposition in the target state supports the sanctions ushered by the sender, the effectiveness of sanctions would improve, given that the opposition in the sender is in support of its government. The worst sanctions’ effectiveness outcomes are recorded when the opposition in the target supports the target state government. This worsening also increases if the opposition in the sender does not support its governments’ sanctions. This opens up more resource avenues to the target regime to furnish its alternative actions in defiance to the sender. Building on the social mobilization models, if the target features a vibrant middle class that acts in support of the sender state, resources to the ruling regime will be further restrained and political pressure amassed, leading to likely policy changes as seen from the probabilities in Table 5.

The best outcome for economic sanctions with respect to regime type is that the opposition in the target acts against the wishes of its government, and the episode is related to a security-related issue. The worst outcomes for economic sanctions are found when the target state has a supportive opposition, and the episode relates to a security issue. As an illustration, consider the United States–Canada sanctions against South Korea in 1975. South Korea desired to attain nuclear weapons to protect itself from the threat of North Korea. Within the South Korean polity, pressure groups from the business community did not want to lose their close ties to US and Canadian markets. Therefore, they did not support their governments’ decisions. In less than two years, the Korean government changed its policy to conform to the wishes of the US, dissolving its plans for nuclear capability.

The present study has also demonstrated that issue salience is an important aspect of economic sanctions’ effectiveness. Consistent with prior research, nonsecurity-related objectives like human rights- or political prisoners-related sanctions work more effectively compared to security-related matters such as terrorism and nuclear proliferation. It is found that when the opposition supports the government, sanctions work better in both security and nonsecurity conflict scenarios. The target state will be affected similarly across both issue types (security and nonsecurity) when the opposition supports the sending governments’ sanctioning episode. This emerges from the overall credible signaling argument. Targets are therefore more likely to change their behavior when they perceive that all actors within the sending side are rallying around the flag and committing all necessary resources to make the sanctions work. This does not change with respect to the issue type because the opposition is in full support. The issue type seems to matter only when credible signals are weak.

The theoretical models suggested here indicate that nonsecurity issues have lower probabilities of escalating to imposition from the threatening stage than security-related matters. This result is linked to the high prohibitive costs associated with wars and the low salience of nonsecurity-related issues. States are not willing to fight each other over global warming or human rights violations. This research provides the support that nonsecurity-related issues are scapegoats for leaders, where they can tout their strength through the imposition of sanctions based on these types of issues. Leaders seek to please their constituents, and one way is the imposition of sanctions on nonsecurity-related issues, such as international law breaches, despite their general ineffectiveness.

6. Conclusions

This analysis has suggested that during times of conflict, where economic sanctions are being considered, sanctions work better for security-related issues. The likelihood of an escalation of economic sanctions from the threatening stage to the imposition stage increases for security-related issues compared to nonsecurity-related ones in dictatorships and countries with little to no opposition.

The findings also provided evidence that security-related issues intensify the state’s reactions on a target state behaving in a way that poses a real or perceived threat to the survival of the sending regime. Therefore, senders are more likely to initiate harsh measures on disputes which comprise their essential existence. Issue salience continues to be a trustworthy predictor of crisis escalation in international relations. Those issues with higher salience are, therefore, most likely to be dealing with security concerns and are more likely to result in war.

The overall results indicate that the best-case scenario for successful economic sanction outcomes is when there is a supporting opposition in the sender state, and there is a non-supporting opposition in the target state for security-related issues. In a similar vein, sanctions bring out worst outcomes when there is a non-supporting opposition in the sender state and a supporting opposition in the target state, and sanctions are related to nonsecurity issues. This study demonstrated that an understanding of both regime type and issue type are necessary to explain the success or failure of economic sanctions.

Findings of this research have also indicated that economic sanctions should be used restrictively. They are suitable for nonsecurity-related matters, such as human rights or trading practices. Democratic governments should only utilize them when the main opposition supports their behaviors. The government should garner the support of all domestic actors, if possible (including the electorate), to prevent the opposition from exploiting the issue to their benefit. Dictatorships are not immune from the opposition or electorate effects, and therefore their governments need also to marshal the support of main stakeholders within their states.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers for excellent comments on an earlier drafts.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adam, Antonis, and Sofia Tsarsitalidou. 2019. Do sanctions lead to a decline in civil liberties? Public Choice 180: 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Susan Hannah. 2005. The determinants of economic sanctions success and failure. International Interactions 31: 117–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Susan Hannah. 2008. The domestic political costs of economic sanctions. Journal of Conflict Resolution 52: 916–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, Adrian U-Jin, and Dursun Peksen. 2007. When do economic sanctions work? Asymmetric perceptions, issue salience, and outcomes. Political Research Quarterly 60: 135–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienen, Henry, and Robert Gilpin. 1980. Economic Sanctions as a Response to Terrorism. Journal of Strategic Studies 3: 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biersteker, Thomas J., Sue E. Eckert, and Marcos Tourinho, eds. 2016. Targeted Sanctions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Risa A. 2002. Sanctions and regime type: What works, and when? Security Studies 11: 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortright, David, and George Lopez. 2000. The Sanctions Decade: Assessing UN Strategies in the 1990s. Boulder: Lynne Reinner. [Google Scholar]

- de Mesquita, Bruce Bueno, Alastair Smith, James D. Morrow, and Randolh M. Siverson. 2005. The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doxey, Margaret P. 1971. Economic Sanctions and International Enforcement. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Sue E. 2008. The Use of Financial Measures to Promote Security. Journal of International Affairs 62: 103–11. [Google Scholar]

- Escribà-Folch, Abel. 2012. Authoritarian responses to foreign pressure: Spending, repression, and sanctions. Comparative Political Studies 45: 683–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribà-Folch, Abel, and Joseph Wright. 2010. Dealing with tyranny: International sanctions and the survival of authoritarian rulers. International Studies Quarterly 54: 335–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galtung, Johan. 1967. On the Effects of International Economic Sanctions: With Examples from the Case of Rhodesia. World Politics 19: 378–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giumelli, Francesco. 2011. Coercing, Constraining and Signalling: Explaining UN and EU Sanctions after the Cold War. London: ECPR Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grauvogel, Julia, Amanda A. Licht, and Christian von Soest. 2017. Sanctions and signals: How international sanction threats trigger domestic protest in targeted regimes. International Studies Quarterly 61: 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufbauer, Gary Clyde, Jeffrey J. Schott, and Kimberly Ann Elliott. 1990. Economic Sanctions Reconsidered. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Lee. 2015. Societies Under Siege: Exploring How International Economic Sanctions (Do Not) Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaempfer, William H., Anton D. Lowenberg, and William Mertens. 2004. International economic sanctions against a dictator. Economics & Politics 16: 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplowitz, Donna Rich. 1998. Anatomy of a Failed Embargo: U.S. Sanctions against Cuba. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshner, Jonathan. 1997. The microfoundations of economic sanctions. Security Studies 6: 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoffler, Rachel L. 2009. Bank Shots: How the Financial System Can Isolate Regimes. Foreign Affairs 88: 101–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, James M. 1986. Trade Sanctions as Policy Instruments. International Studies Quarterly 30: 153–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, Solomon. 2012. Timing Is Everything: Economic Sanctions, Regime Type, and Domestic Instability. International Interactions 38: 79–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, Daniel, and Henry Pascoe. 2017. Sanctions and preventive war. Journal of Conflict Resolution 61: 1711–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclean, Elena V., and Dwight A. Roblyer. 2016. Public support for economic sanctions: An experimental analysis. Foreign Policy Analysis 13: 233–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, Elena V., and Taehee Whang. 2014. Designing foreign policy: Voters, special interest groups, and economic sanctions. Journal of Peace Research 51: 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T. Clifton, Navin Bapat, and Yoshiharu Kobayashi. 2014. Threat and imposition of economic sanctions 1945–2005: Updating the TIES dataset. Conflict Management and Peace Science 31: 541–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nossal, Richard Kim. 1999. Liberal Democratic Regimes, International Sanctions, and Global Governance. In Globalization and Global Governance. Edited by Vayrynen Raimo. Baltimore: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Onder, M. 2019. International Economic Sanctions Outcome: The Influence of Political Agreement. Ph.D. dissertation, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pape, Robert A. 1997. Why economic sanctions do not work. International Security 22: 90–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peksen, Dursun. 2009. Better or worse? The effect of economic sanctions on human rights. Journal of Peace Research 46: 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peksen, Dursun. 2019. Autocracies and Economic Sanctions: The Divergent Impact of Authoritarian Regime Type on Sanctions Success. Defence and Peace Economics 30: 253–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peksen, Dursun, and A. Cooper Drury. 2010. Coercive or corrosive: The negative impact of economic sanctions on democracy. International Interactions 36: 240–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsebelis, George. 1990. Are sanctions effective? A game-theoretic analysis. Journal of Conflict Resolution 34: 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, Geoffrey. 2013. Regime type, issues of contention, and economic sanctions: Re-evaluating the economic peace between democracies. Journal of Peace Research 50: 479–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whang, Taehee. 2011. Playing to the home crowd? Symbolic use of economic sanctions in the United States. International Studies Quarterly 55: 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, H. Kaempfer, and Anton David Lowenberg. 1988. The theory of international economic sanctions: A public choice approach. The American Economic Review 78: 786–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Reed M. 2008. “A hand upon the throat of the nation”: Economic sanctions and state repression, 1976–2001. International Studies Quarterly 52: 489–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Joseph, and Abel Escribà-Folch. 2012. Authoritarian institutions and regime survival: Transitions to democracy and subsequent autocracy. British Journal of Political Science 42: 283–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarate, Juan. 2013. Treasury’s War: The Unleashing of a New Era of Financial Warfare. New York: Public Affairs. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).