4.1. Elicitations for Each Category of Wine by Attribute and Country

The relative frequencies of elicitations collected through the pick-any technique for each category of wine and country, and grouped by type of characteristic, are summarised in

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5.

Respondents mainly ascribed concrete wine characteristics to conventional wine, organic wine and biodynamic wine (

Table 2). Sensory characteristics of wine (i.e., ‘Low quality’, ‘Genuine taste’, and ‘Distinctive taste’) were mainly attributed to conventional, organic and biodynamic wines. Natural/sustainable-development wine was the wine least associated with low quality. French and Italian respondents had different opinions concerning the attributes of quality between conventional and organic wine; however, they agreed on the association of genuine taste with organic and natural/sustainable-development wines and wines with no added sulphites. French respondents reported a distinctive taste for natural/sustainable-development wine and wine with no added sulphites. Both samples agreed that organic and biodynamic wine were expensive, and conventional wine provided good value for money. French respondents also considered fair trade and carbon-neutral wines expensive.

The elicitation of image characteristics highlighted interesting consumer perceptions in relation to product-attribute associations (

Table 3). Indeed, the attribute ‘traditional’ was mostly reserved for conventional wine, while biodynamic and carbon-neutral wine were perceived as ‘innovative’ products. Biodynamic wine emerged as a product that requires more consumer knowledge than the other wine categories. The attributes of ‘luxurious’ and ‘linked to its origin’ were not specifically associated with any of the wines.

Benefits to the consumer mostly involved conventional, organic, biodynamic and no-added-sulphites wines (

Table 4). Health benefits were particularly relevant for wine with no added sulphites and organic wine. The attribute ‘pleasurable and fun’ was connected with conventional wine; organic and biodynamic wines were instead perceived as trendy products in both countries.

Conversely, benefits to society distinguished natural/sustainable-development, fair-trade and carbon-neutral wines (

Table 5). These wines elicited comments about winemakers’ responsibility, support for local producers and respect for ethical values. Benefits to the environment were mostly attributed to organic wine for both samples. French respondents also related benefits to the environment to biodynamic wines, and Italian respondents, to carbon-neutral wines.

4.2. Product–Attribute Associations

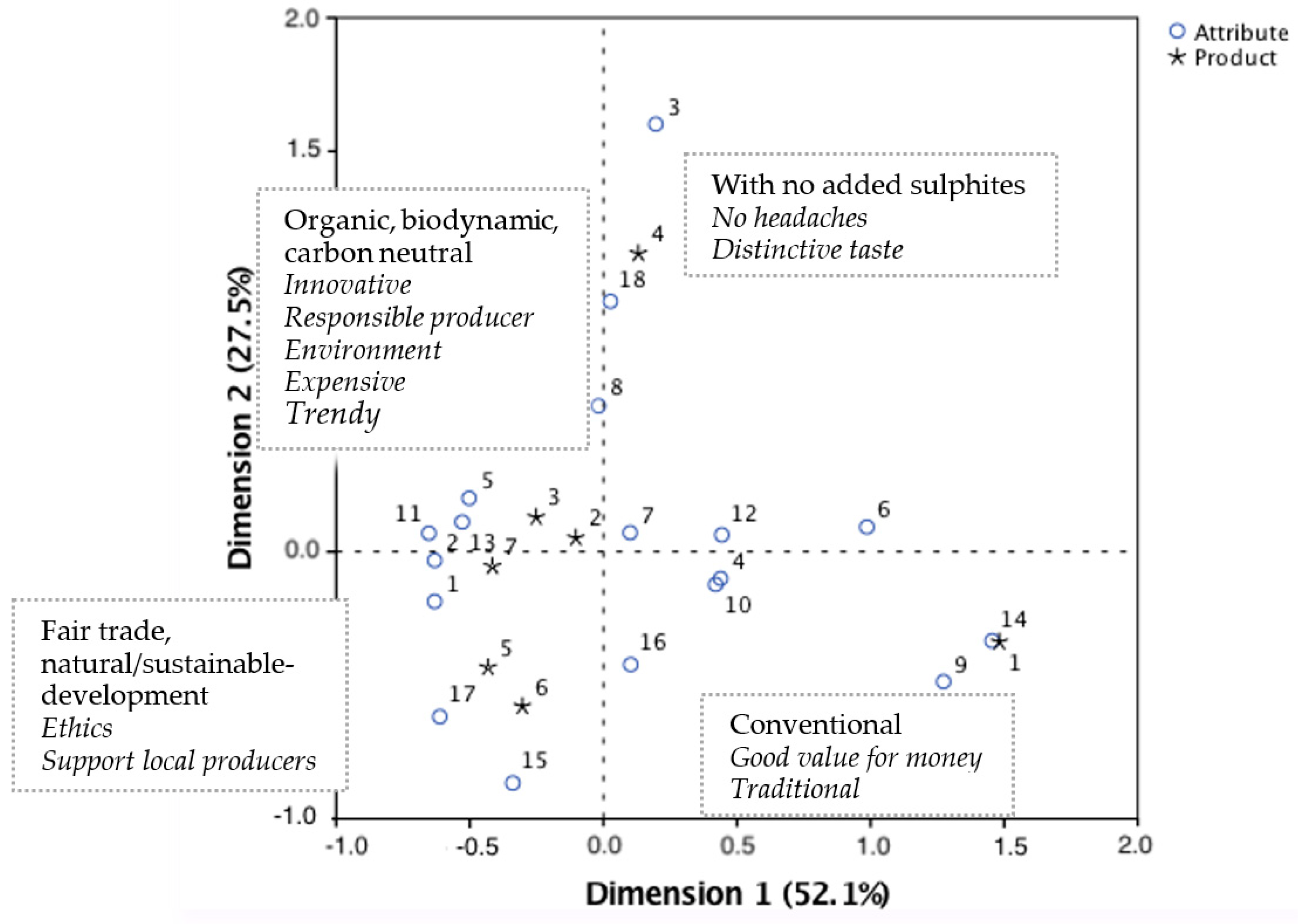

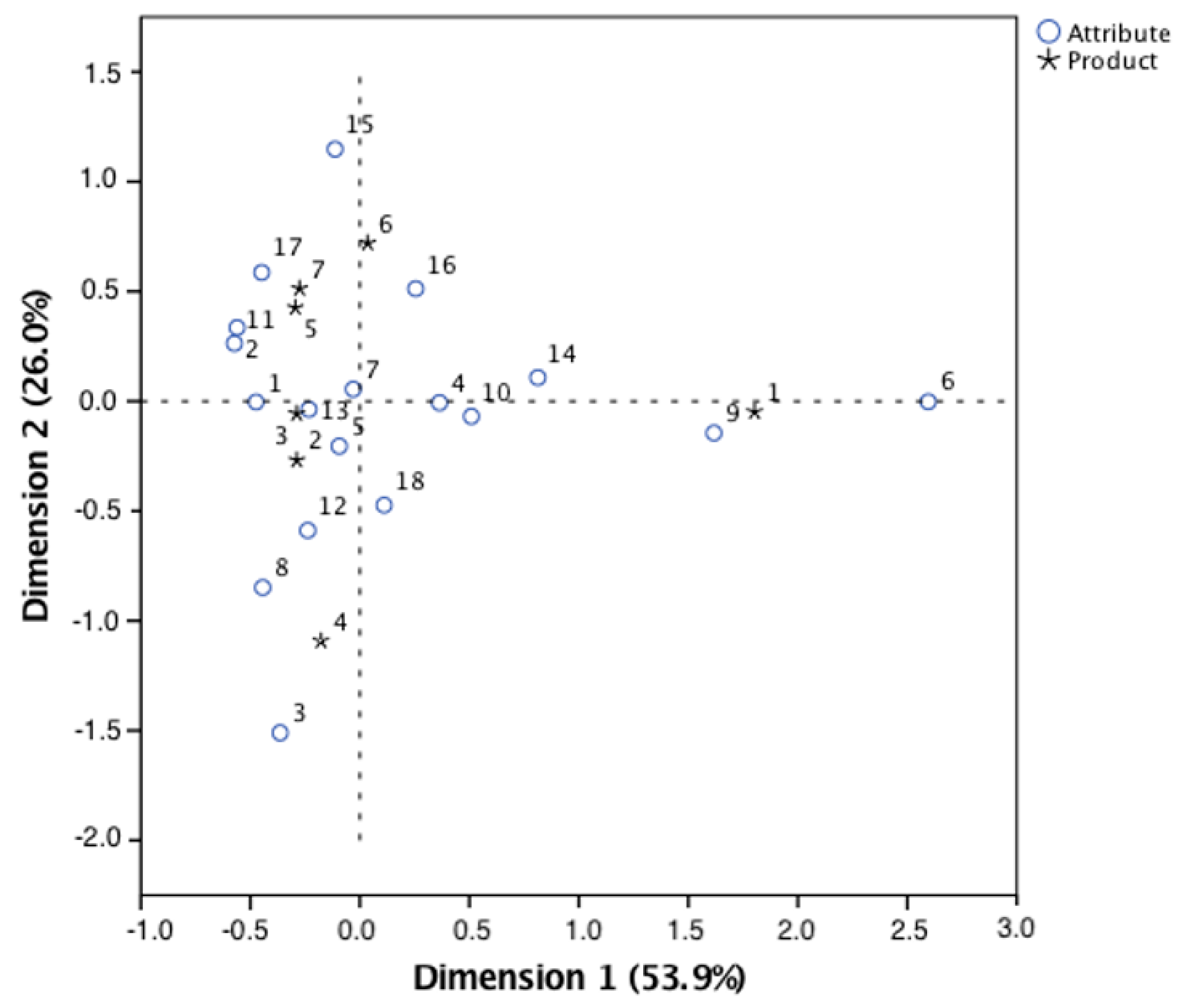

Figure 1 and

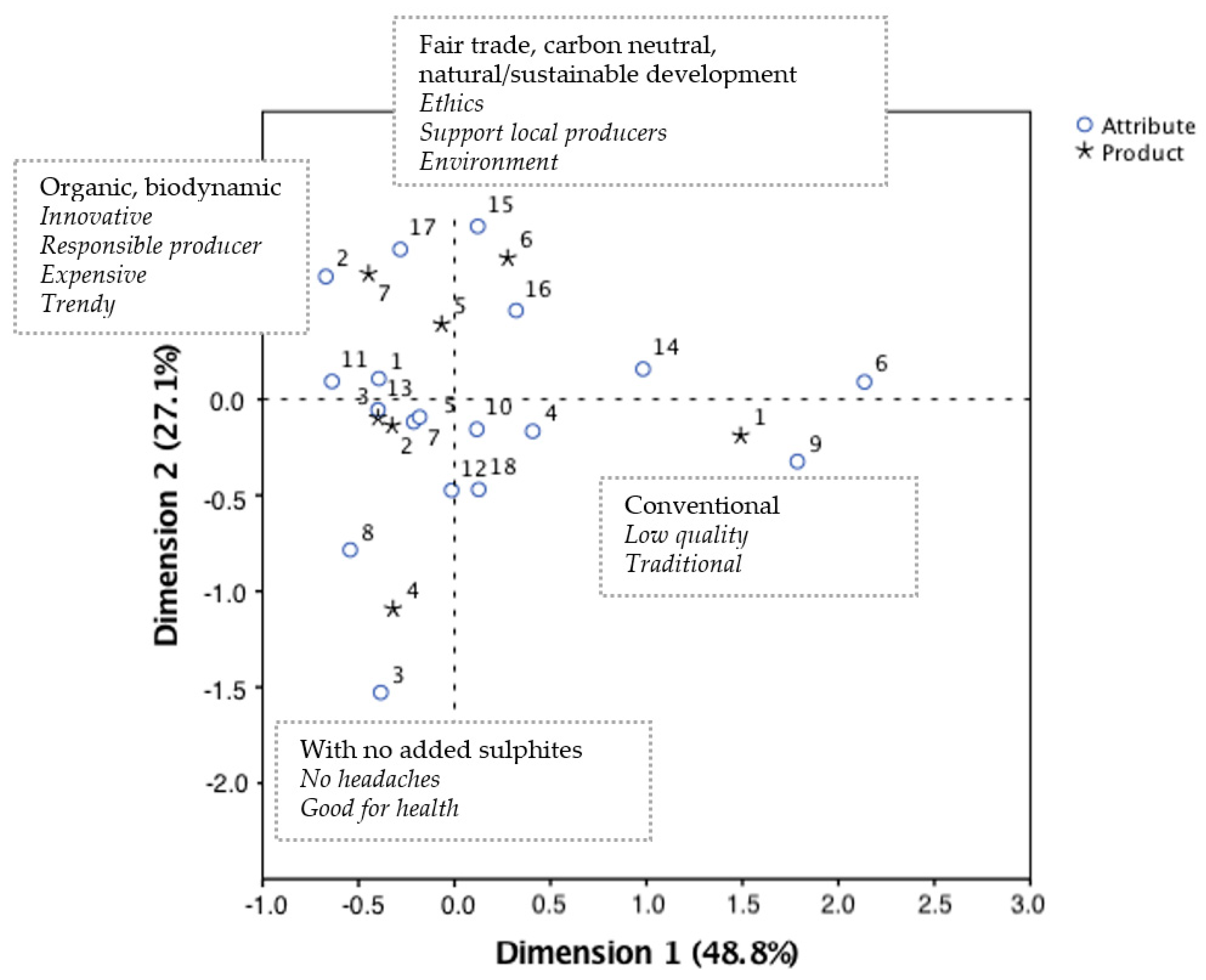

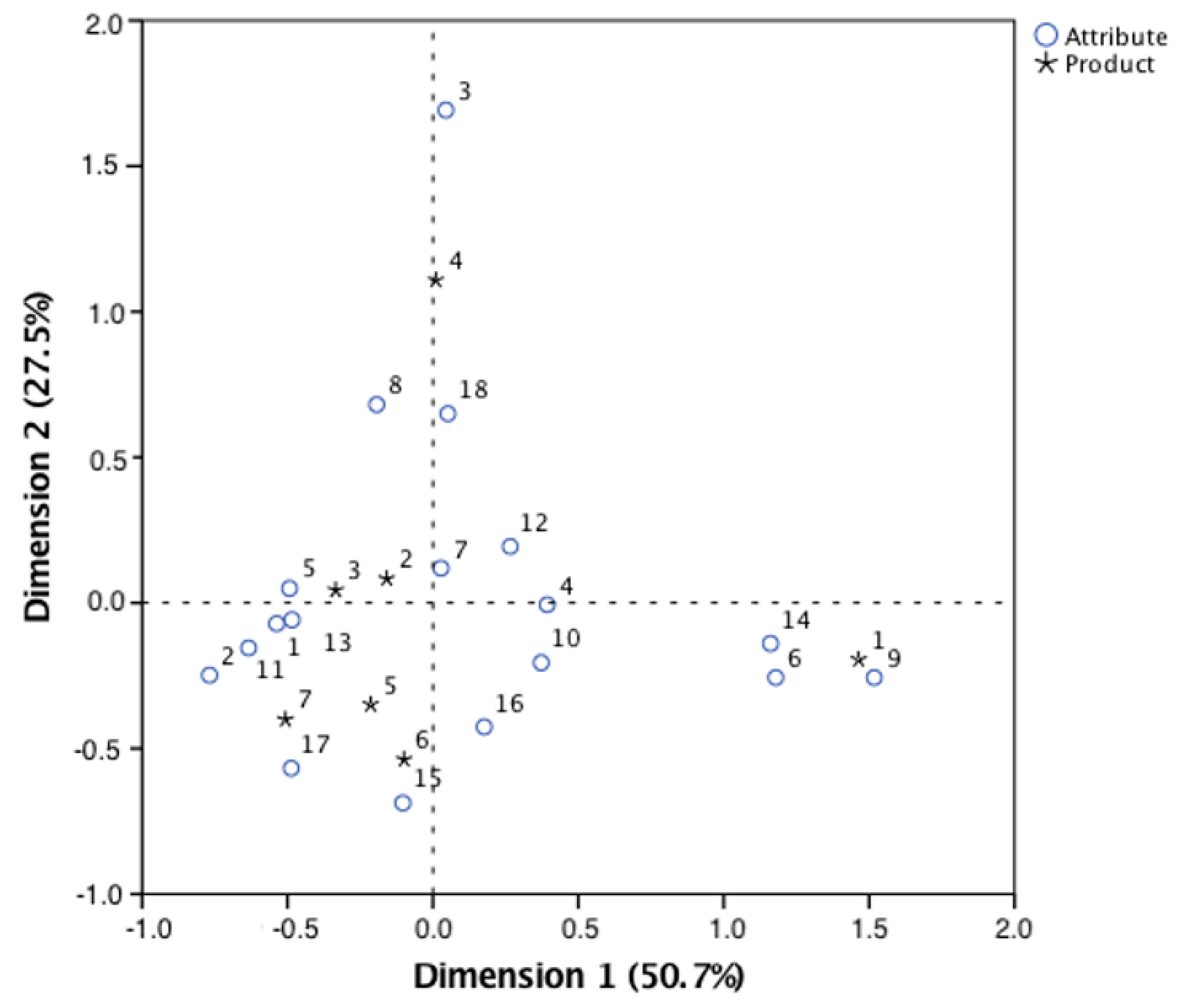

Figure 2 present consumers’ perception maps for product-attribute associations captured by the analysis of the questionnaires for the French and Italian respondents, respectively. The maps demonstrate that there were some similarities between the product-attribute associations of the two samples. However, French respondents appeared to be slightly more able to associate attributes with the proposed products than were Italian respondents. Indeed, in the perceptual map for the Italian sample, some attributes were located near the origin of the dimensions (e.g., pleasurable and fun #4, luxurious #10, trendy #5, and requiring education to appreciate #7). This means that these attributes tended to be discarded when consumers were asked to characterise some of the proposed wines. In addition, the French respondents were unsure in their evaluations of some attributes (e.g., requiring education to appreciate #7). In both samples, organic and biodynamic wines were positioned near the origins of axes. This location suggests that perceptions of these categories of wines were different within the groups of informants. Consumers seemed to be uncertain about associating specific attributes to these products. Therefore, they were unable to converge on clear preferences, and a differentiated positioning of these two categories, unlike the others, did not emerge.

Two latent dimensions, Dimension 1 and Dimension 2, explained approximately 80% of the variance within the French sample and approximately 75% in the Italian sample. Dimension 1 distinguished the sustainable wines from the conventional wine, and explained 52.1% of the variance in the French sample and 48.8% in the Italian sample. Dimension 2 explained 27% of the variance in both samples and distinguished wine with no added sulphites from other sustainable wines. This dimension was also able to discriminate attributes promoting health and sensory benefits from those linked to the respect of ethics.

The perceptual map of the French consumers (

Figure 1) highlights the following:

conventional wine (Product 1) was mainly perceived as good value for money (#14) and traditional (#9)

wine with no added sulphites (Product 4) was perceived as having a distinctive taste (#18), not causing headaches (#3) and being good for health (#8)

natural or sustainable-development wine promoted by producers’ organisations and fair-trade wine (Products 5 and 6, respectively) were perceived as having the same benefits, that is, respecting ethical values (#17) and supporting local production (#15)

organic wine and biodynamic wine (Products 2 and 3, respectively) were close to the origin of the axes and associated with requiring education to appreciate (#7), as well as with being trendy (#5) and expensive (#13)

carbon-neutral wine (Product 7) were perceived similarly to organic and biodynamic wines, and were considered expensive (#5), but respondents recognised this wine as being produced by a more responsible winemaker (#1) and being harmless to the environment (#2).

It was evident that some attributes did not have a specific association with any of the proposed wines. The attributes of low quality (#6), luxurious (#10), pleasurable and fun (#4), genuine taste (#12) and linked to its origin (#16) were in the positive dimension of the maps, but far from the assessed wines.

The perceptual map of the Italian consumers (

Figure 2) highlights the following:

conventional wine was perceived as being traditional (#9) and of low quality (#6), and to a lesser extent as being good value for money (#14)

consumers identified wine with no added sulphites as different from the other sustainable wines, perceiving it as not causing headaches (#3) and being good for health (#8)

carbon-neutral wine, natural or sustainable-development wine promoted by producers’ organisations and fair-trade wine were located on the opposite side of Dimension 2, far from wine with no added sulphites

carbon-neutral wine was perceived as being harmless to the environment (#2) and respectful of ethical values (#17)

organic wine and biodynamic wine were close to each other and shared the characteristics of requiring education to appreciate (#7) and being trendy (#5), expensive (#13) and innovative products (#11) from responsible producers (#1).

For the Italian sample, sustainable wine promoted by producers’ organisations did not receive any particular attribute association. In addition, some attributes did not receive a specific wine association. This was the case for the characteristics of pleasurable and fun (#4), luxurious (#10), genuine taste (#12), and distinctive taste (#18).

The analysis of deviations from the expected responses in the French (

Table 6) and the Italian (

Table 7) samples shows that respondents positively associated conventional wine with the characteristics of tradition, good value for money, pleasurable and fun. Conventional wine is a broad product concept and respondents associated with it the attributes of being low quality and luxurious. However, conventional wine was not seen as trendy, innovative, or more expensive. Respondents also had negative perceptions of the societal benefits of a more responsible winemaker, harmlessness to the environment, and respect for ethical values in the case of conventional wine.

Organic and biodynamic wines received moderate attribute associations in relation to the expected levels of response, as confirmed by their positions for both products and countries close to the centre of the perceptual maps. Organic wine was associated with the characteristics of being harmless to the environment, trendy, good for health and more expensive. For Italian respondents, organic wine also has a genuine taste. Organic wine was not seen as being low quality, traditional, or supporting local production for the Italian respondents. For the French respondents, organic wine was not perceived as having the attributes of being innovative or requiring education to appreciate.

Biodynamic wine was perceived by both samples as more expensive and innovative, but not able to support local production and not providing good value for money. French respondents highlighted the perception that it can be harmless to the environment. Italian respondents positively associated it with luxury and requiring education to appreciate, but negatively associated it with tradition, respect of ethical values, and links to the origin.

Wine with no added sulphites was clearly associated with health benefits (‘does not cause headaches’ and ‘good for health’) and for French respondents, it also has a distinctive taste. Negative associations were found for its benefits to society and the environment (‘harmless to the environment’, ‘supports local production’, ‘linked to its origin’, and ‘respect for ethical values’).

Respondents expressed only positive associations with natural or sustainable-development wine promoted by producers’ organisations in relation to respect for ethical values. French respondents highlighted the benefits of local production and greater responsibility of the winemaker.

Fair-trade wine was linked to its ability to support local production and respect of ethical values, but was negatively associated with harmlessness to the environment, innovativeness and healthiness.

Conversely, carbon-neutral wine was perceived as harmless to the environment and innovative. Italian respondents added the characteristics of greater responsibility of the winemaker and respect for ethical values. Carbon-neutral wine was not perceived as a traditional product with a genuine taste.

4.3. Wine Involvement, Propensity towards EMCB, and Perceptions of Sustainable Wines

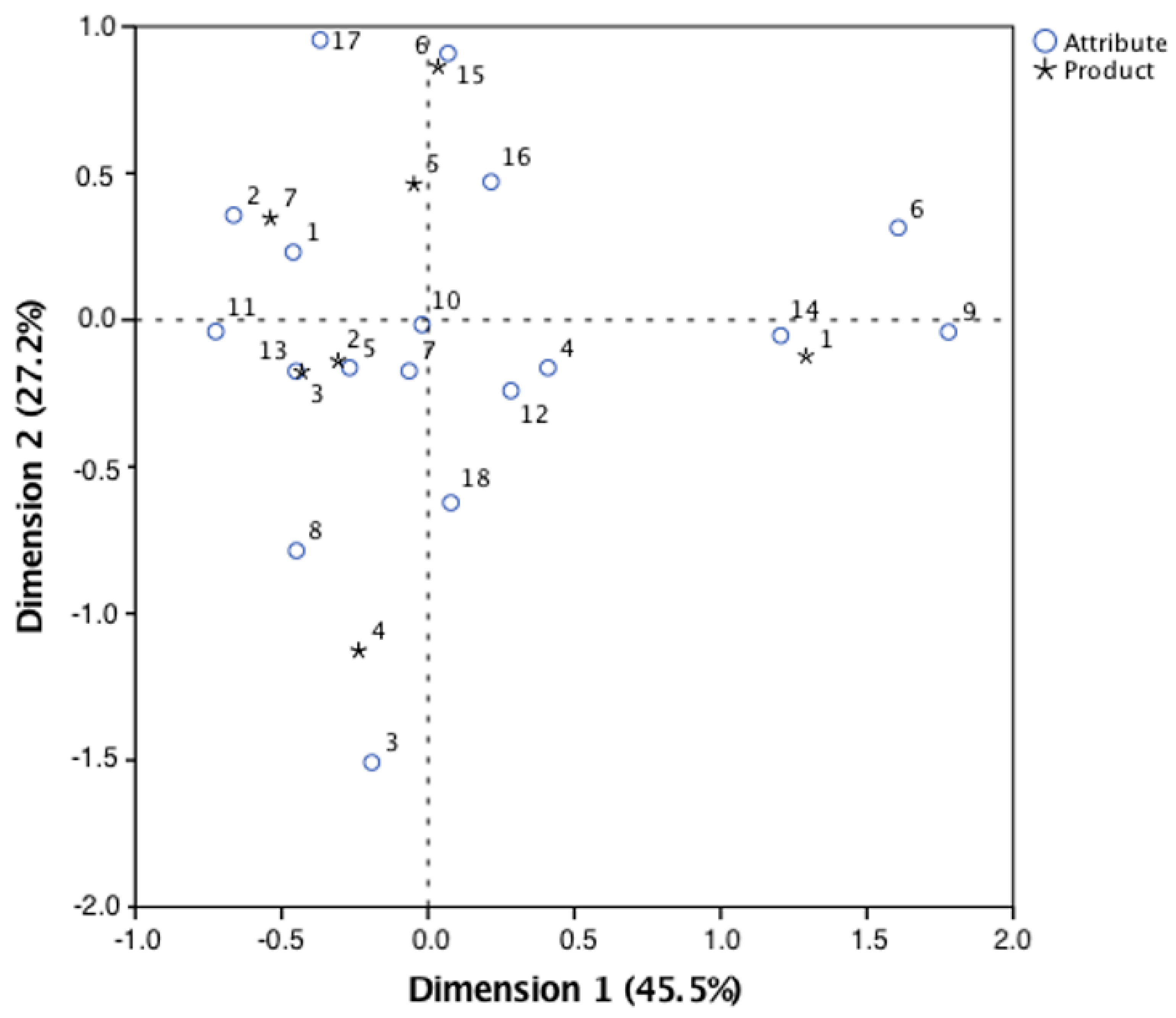

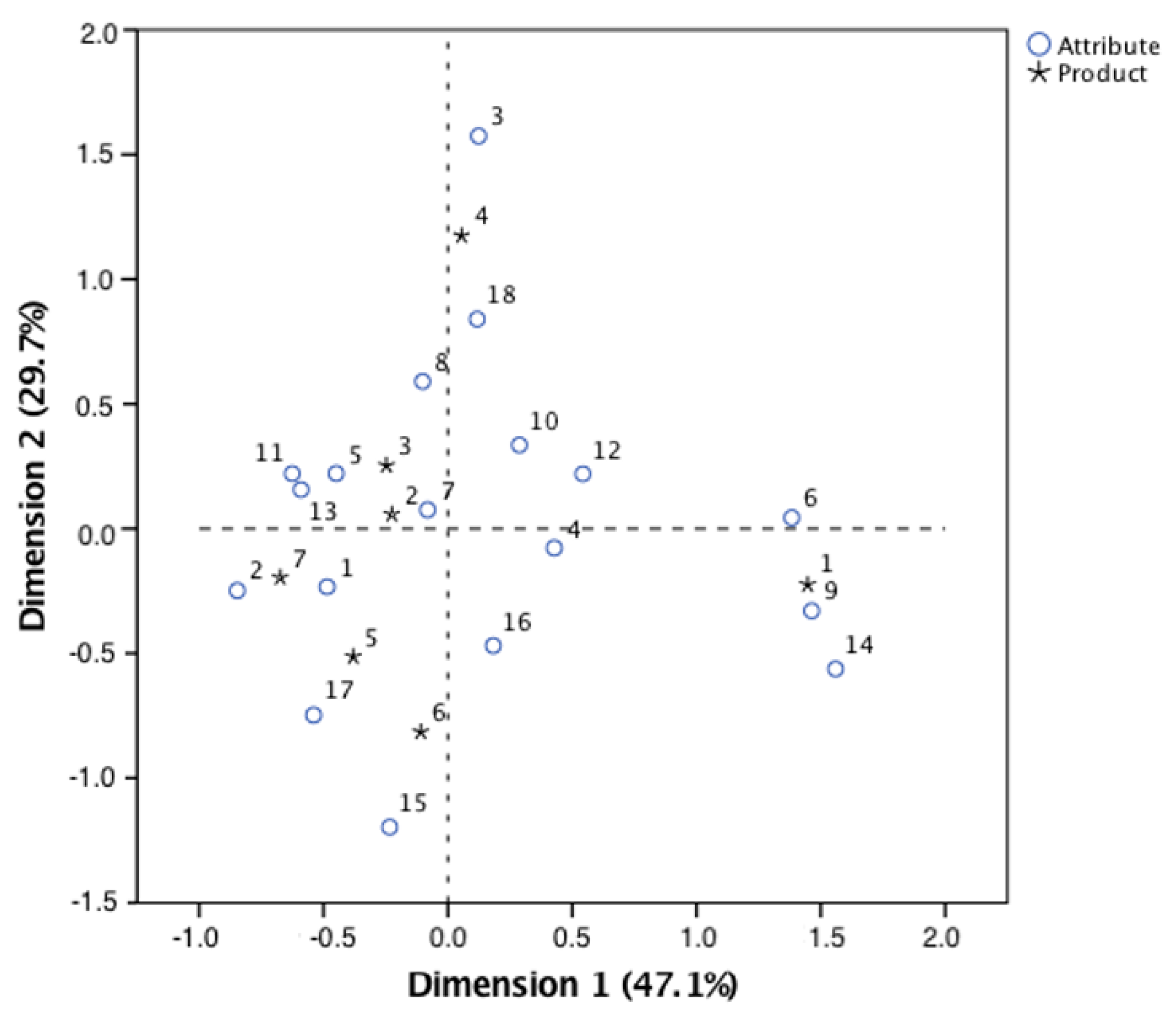

French and Italian respondents were assigned to four clusters of consumers combining ‘low’ and ‘high’ levels of EMCB and ‘low’ and ‘high’ levels of involvement with wine. Four perceptual maps were generated to analyse the influences of EMCB and wine involvement on consumers’ perceptions of sustainable wine (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The four types of consumers are as follows: (1) low EMCB and low wine involvement (T1,

Figure 3); (2) low EMCB and high wine involvement (T2,

Figure 4); (3) high EMCB and low wine involvement (T3,

Figure 5); and (4) high EMCB and high wine involvement (T4,

Figure 6).

Two perceptions were shared by all clusters: (1) conventional wine is different from sustainable wines and is associated with tradition, good value for money and low quality; and (2) wine with no added sulphites is associated with health benefits.

The associations identified by the four clusters of respondents followed similar patterns for the other types of surveyed wine. However, some differences between clusters appeared. Less-involved consumers belonging to T1 and T3 associated specific attributes to conventional wine and wine with no added sulphites, but showed less discriminatory ability in relation to the other sustainable wines. Some products and attributes were located near the perceptual space origin (

Figure 3 and

Figure 5). When involvement with wine and EMCB were low (T1), few specific attributes were clearly ascribed to sustainable wines (e.g., fair-trade wine supports local producers and respect for ethical values). When involvement was low but EMCB was high (i.e., among T3 consumers), natural/sustainable-development, fair-trade and carbon-neutral wines were positioned very closely to each other in the perceptual space and only an ethical value (attribute #15 ‘supports local producers’) received more attention than the other attributes attached to sustainable wines.

Consumers with high involvement with wine (i.e., T2 and T4 consumers) found it easier to ascribe product-attribute associations (e.g., the distinctive taste of wine with no added sulphites) to sustainable wines than did the other two clusters. Consumers belonging to T2, who have high involvement with wine but have low environmental and ethical consciousness, seemed to have a more developed discriminant ability for attributes than for products (

Figure 4). They ascribed benefits to society such as support for local producers (fair-trade wine), respect for ethical values (natural/sustainable-development wine), more responsible winemakers, as well as harmless to the environment (carbon-neutral wine). Organic and biodynamic wines had a similar, and less distinctive, position near the origin of the perceptual map. Consumers in T4 with both high EMCB and product involvement seemed to make clearer distinctions than the other groups (

Figure 6). Organic and biodynamic wines were associated with certain product characteristics and benefits (i.e., being trendy, more expensive and requiring education), while natural/sustainable-development, fair-trade and carbon-neutral wines were mainly associated with benefits to society (i.e., support for local producers and respect for ethical values).

These findings highlight that involvement with the product can influence the ability to discriminate among different types of sustainable wine for the consumer. Conversely, consumers’ EMCB does not emerge as having the strength to explain differences in consumer perceptions.

Rather than consciousness of ethically minded behaviour, wine involvement seems to be the driver of consumers’ perception of wine through it generating interest in and knowledge about different types of wine.