Analysis of Supply and Demand to Enhance Educational Tourism Experience in the Smart Park of Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

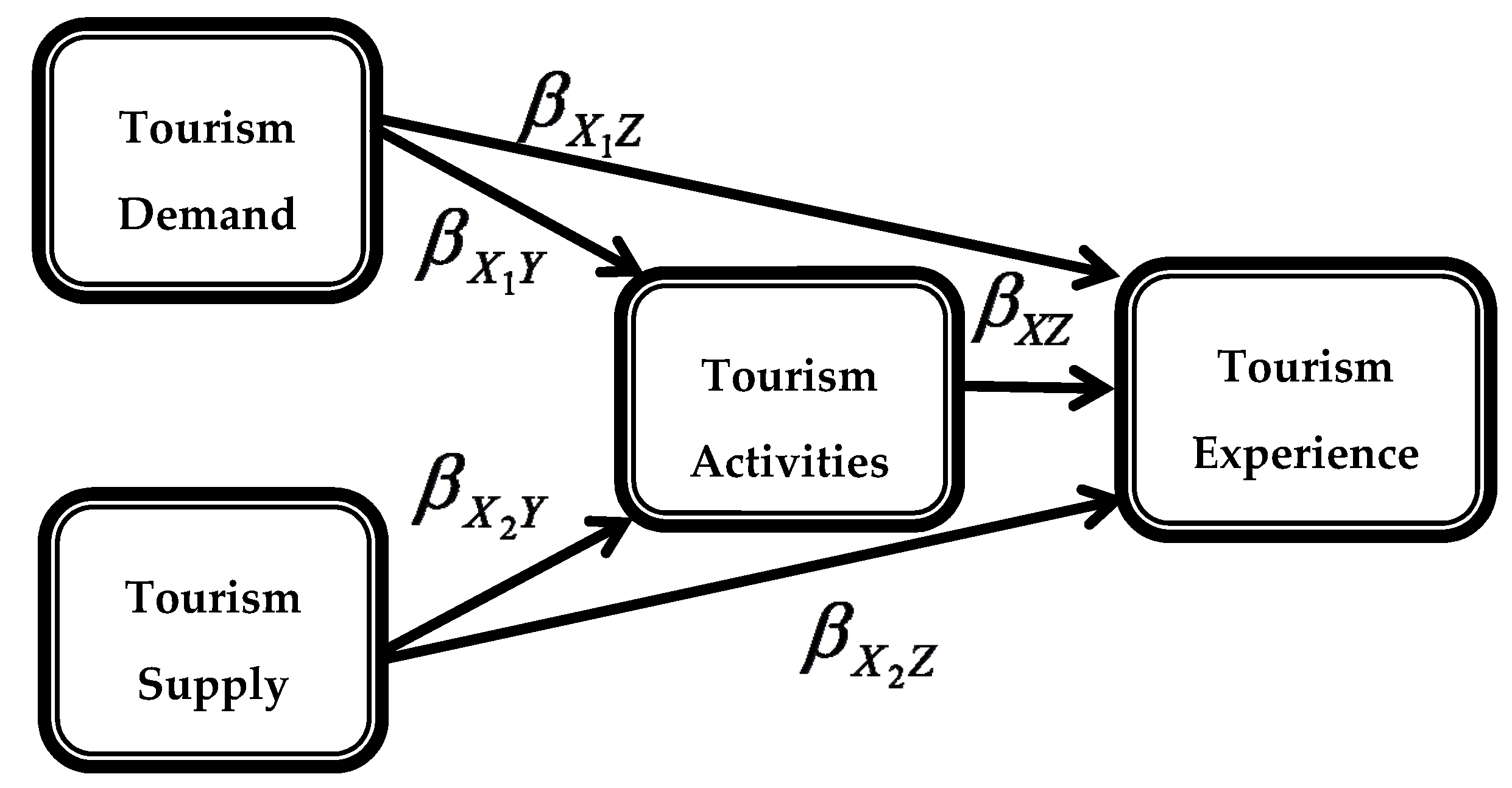

3. Method

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Respondents and Description of Variables

4.2. Instrument Test

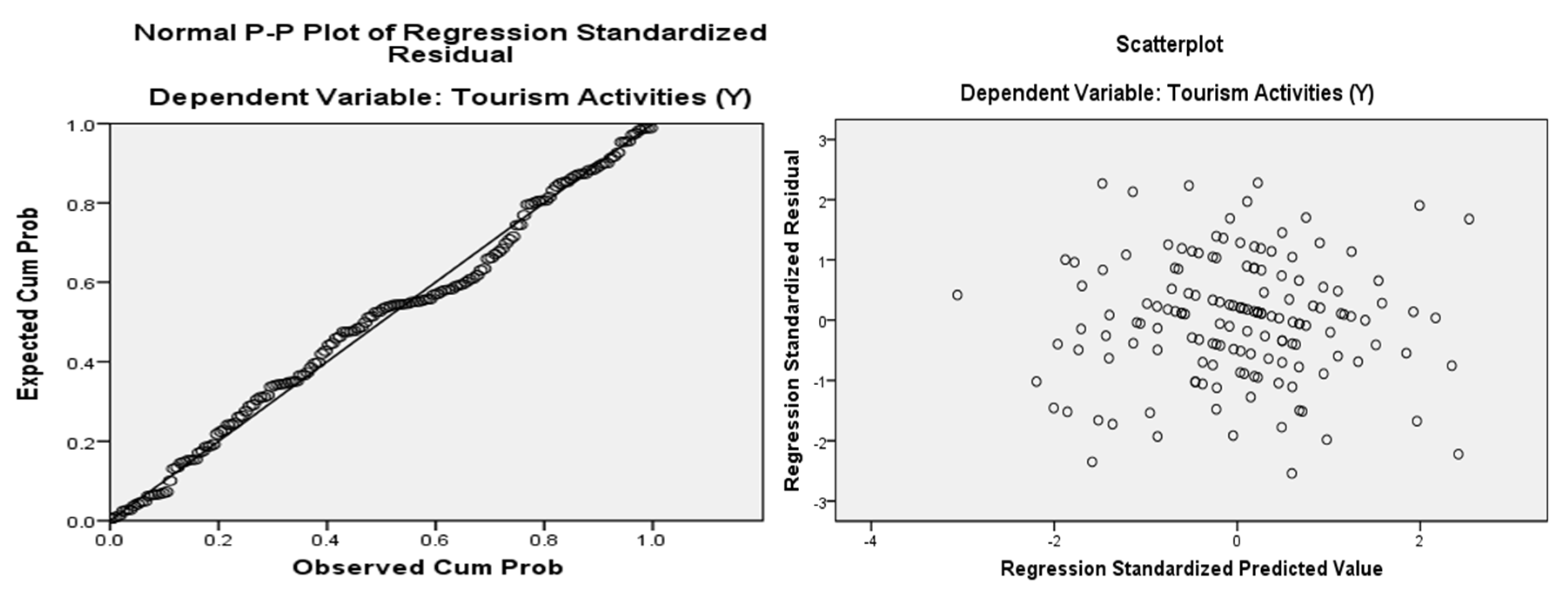

4.3. Normality Data Test

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aho, Seppo K. 2001. Towards a general theory of touristic experiences: Modelling experience process in tourism. Tourism Review 56: 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankomah, Paul K., and Trent R. Larson. 2002. Education Tourism: A Strategy to Suistainable Tourism Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Available online: http: //unpan1.un.org/ intradoc/ groups/public/documents/idep/unpan002585.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2015).

- Berry, Leonard L., Lewis P. Carbone, and Stephan H. Haeckel. 2002. Managing the total customer experience. MIT Sloan Management Review 43: 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Binkhorst, Esther. 2005a. Creativity in the experience economy, towards the co-creation tourism experience? Paper presented at the Presentation at the Annual ATLAS Conference ‘Tourism, Creativity and Development’, Barcelona, Spain, October. [Google Scholar]

- Binkhorst, Esther. 2005b. The co-creation tourism experience. Available online: http://www.esade.edu/cedit2006/pdfs2006/papers/esther_binkhorst_paper_esade_may_06.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2017).

- Brunner-Sperdin, Alexandra, and Mike Peters. 2009. What influences guests' emotions? The case of high-quality hotels. International Journal of Tourism Research 11: 171–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, Dimitrios. 2000. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management 21: 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. 2013. Data Statistik Tahun 2013. Available online: https://yogyakarta.bps.go.id/ (accessed on 15 February 2014).

- Cohen, Eric H. 2008. Youth Tourism to Israel. Educational Experiences of the Diaspora. Clevedon: Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Chris, and Colin Michael Hall. 2008. Contemporary Tourism: An International Approach. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, Geoffrey I., and Brent J. Ritchie. 1999. Tourism. Competitiveness, and Societal Prosperity. Journal of Business Research 44: 137–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly, and Jeremy Hunter. 2003. Happiness in everyday life: The uses of experience sampling. Journal of Happiness Studies 4: 185–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, Larry, and Chulwon Kim. 2003. Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Current Issues in Tourism 6: 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverri, Per. 2005. Video-based Methodology: Capturing Real-time Perceptions of Customer Processes. International Journal of Service Industry Management 16: 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formica, Sandro. 2001. Measuring Destination Attractiveness: A proposed Framework. Paper presented at the International Business Conference, Miami, FL, USA, December 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Frechtling, Douglas C. 2001. Forecasting Tourism Demand: Methods and Strategies. London: Butterworth-Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Ghozali, Imam. 2008. Model Persamaan Struktural Konsep dan Aplikasi Dengan Program Amos 16.0. Semarang: Diponegoro University. [Google Scholar]

- Goeldner, R. Charles, and Brent J. R. Ritchie. 2006. Tourism: Principles, Practices, Philosophies, 10th ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Salah. 2000. Determinants of Market competitiveness in an environmentally sustainable tourism Industry. Journal of Travel Research 38: 239–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrigan, David. 2009. Branded Content: A New Model For Driving Tourism Via Film And Branding Strategies. Tourismos: An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism 4: 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kamenidou, Irene, Spyridon Mamalis, and Contantinos-Vasilios Priporas. 2009. Measuring Destination Image and Consumer Choice Criteria: The Case of Mykonos Island. Tourismos: An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism 4: 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jeongmi, and Daniel R. Fesenmaier. 2015. Sharing Tourism Experiences: The Postrip Experience. Journal of Travel Research 56: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jong-Hyeong, Brent J. R. Ritchie, and Bryan McCormick. 2012. Development of a Scale to Measure Memorable Tourism Experience. Journal of Travel Research 51: 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, Metin, and Mike Rimmington. 1999. Measuring tourist destination competitiveness: Conceptual considerations and empirical findings. Hospitality Management 18: 273–83. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/2338968/Measuring_tourist_destination_competitiveness_conceptual_considerations_and_empirical_findings (accessed on 20 January 2016). [CrossRef]

- Larsen, Svein. 2007. Aspects of a Psychology of the Tourist Experience. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 7: 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Bruce. 2001. Resource and Environmental Management. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mossberg, Lena. 2007. A Marketing Approach to the Tourist Experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 7: 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Haemoon, Ann Marie Fiore, and Miyoung Jeoung. 2007. Measuring Experience Economy Concepts: Tourism Applications. Journal of Travel Research 46: 119–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parahalad, Coimbatore Krishna, and Venkat Ramaswamy. 2004. Co-creating Unique Value with Customers. Strategy and Leadership 32: 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Sanghun, and Carla Almeida Santos. 2016. Exploring the Tourist Experience: A Sequential Approach. Journal of Travel Research 56: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, Joseph B., and James H. Gilmore. 1999. The Experience Economy: Work Is a Theatre and every Business a Stage. Cambridge: Harvard Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Pitana, I. Gede, and Putu G. Gayatri. 2005. Sosiologi Pariwisata. Yogyakarta: Andi Offset. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsson, Susanne H. G., and Sudhir H. Kale. 2004. The Experience Economy and Commercial Experiences. The Marketing Review 4: 267–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Personal, Social and Humanities Education (PSHE). 2013. Tourism and Hospitality Studies; Introduction to Tourism. Available online: http://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/en/curriculum-development/kla/pshe/nss-curriculum/tourism-and-hospitality-studies/Tourism_English_19_June.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2016).

- Ramos, Célia M. Q., and Paulo M. M. Rodrigues. 2013. Research Note: The Importance of Online Tourism Demand. Tourism Economics 19: 1443–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riduwan. 2009. Aplikasi Statistika dan Metode Penelitian untuk. Administrasi dan Manajemen. Bandung: Dewa Ruci. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, Brent W. 2003. Managing Educational Tourism. Great Britain: Cromwelll Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J. R., and Simon Hudson. 2009. Understanding and Meeting the Challenges of Customer/Tourist Experience Research. International Journal of Tourism Research 11: 111–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Athena. 2013. The Role of Educational Tourism in Raising Academic Standards. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 2: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Haiyan, and Lindsay Turner. 2006. Tourism Demand Forecasting. In International Handbook on the Economics of Tourism. London: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, F. Ian, and Stephen Tax. 2004. Toward an Integrative Approach to Designing Service Experiences. Lessons Learned from the Theatre 22: 609–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrooke, John. 2002. The Development and Management of Visitors Attractions. London: Butterworth-Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Tarssanen, Sanna. 2005. Handbook for Experience Tourism Agents. Rovaniemi: University of Lapland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Shane. 2006. Theorizing Educational Tourism: Practices, Impacts, and Regulation in Ecuador. New York: Columbia University. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, Dallen J., and Gyan P. Nyaupane. 2009. Heritage Tourism and Its Impacts: Cultural Heritage and Tourism in the Developing World: A Regional Perspective. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism Product Development Strategy (TPDS). 2007. Available online: http://www.failteireland.ie/FailteIreland/media/WebsiteStructure/Documents/4_Corporate_Documents/Strategy_Operations_Plans/Tourism-Product-Development-Strategy-2007–2013.pdf?ext=.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2016).

- Tourism Policy Review Group (TPRG). 2003. New Horizons for Irish Tourism, an Agenda for Action. Available online: http://www.dttas.ie/sites/default/files/publications/tourism/english/executive-summary-tourism-renewal-group-report-sept-2009/tourismreviewreport03.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2016).

- Urry, John. 2002. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies, 2nd ed. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Duim, René. 2007. Tourism scapes: An actor-network perspective on sustainable tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research 34: 961–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengesayi, Sebastian. 2003. A Conceptual Model of Tourism Destination Competitiveness and Attractiveness. Available online: http://www.anzmac.org/conference_archive/2003/papers/CON20_vengesayis.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2014).

- Verma, Rohit, Gerhard Plaschka, and Jordan J. Louviere. 2002. Understanding customer choices: a key to successful management of hospitality services. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administrative Quarterly 43: 15–24. Available online: http://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1057&context=articles (accessed on 20 January 2016). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Bin, and Shen Li. 2008. Education Tourism Market in China An Exlorative Study in Dalian. International Journal of Business and Management 3: 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yoeti, Oka A. 2008. Perencanaan dan Pengembangan Pariwisata. Jakarta: PT. Pradnya Paramita. [Google Scholar]

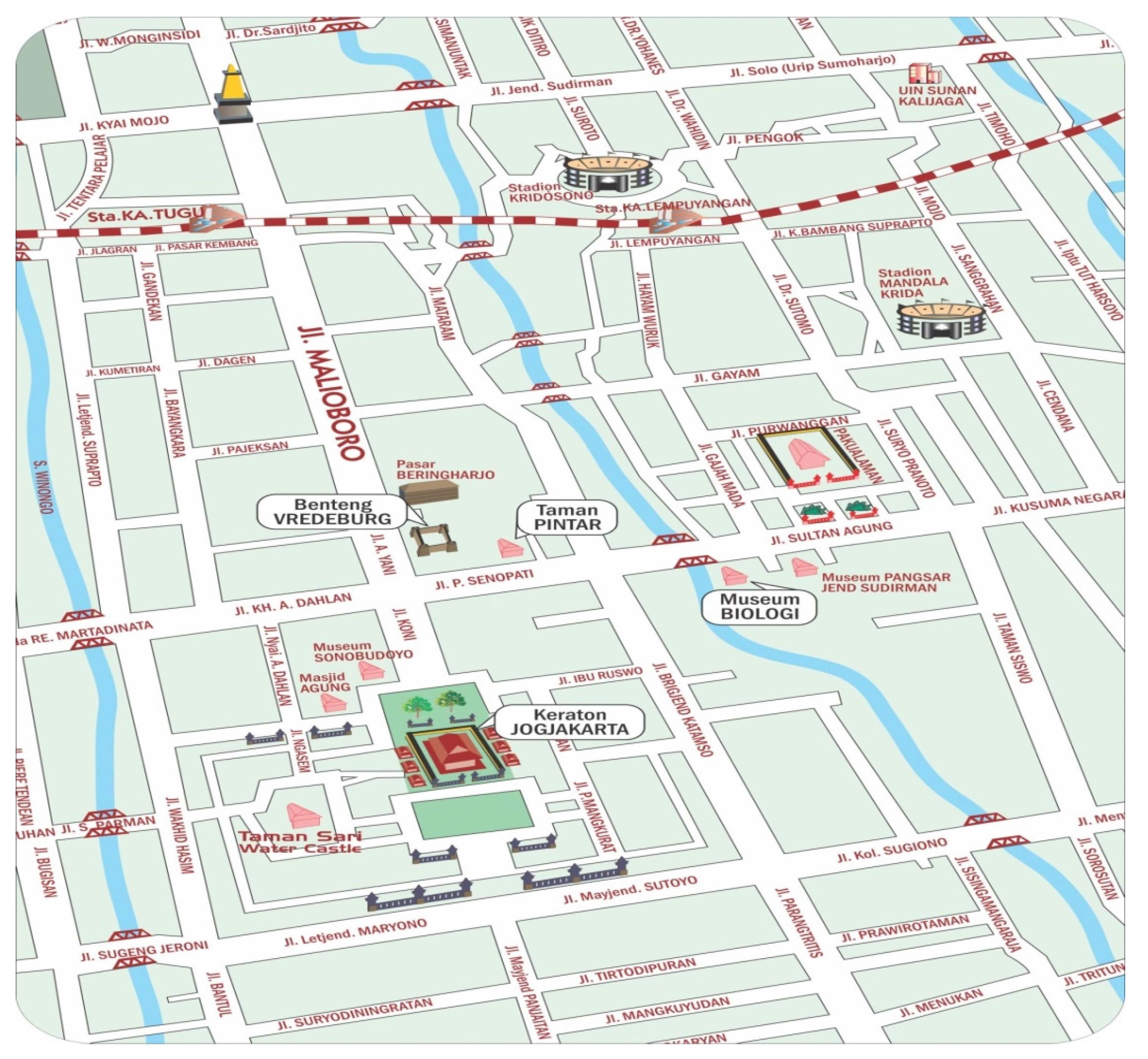

| 1 | Source: reproduce using online sources: https://bakung16.files.wordpress.com/2008/03/peta-quantum-service.jpg. |

| Variable/Score | Choice of Answers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Tourism Demand | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| Tourism Supply | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| Tourism Activities | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| Tourism Experience | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| No | Description | Frequency (People) | Percentage (%) | No | Description | Frequency (People) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gender | 4 | Origin | ||||

| Male | 54 | 36.0 | Yogyakarta | 34 | 22.7 | ||

| Female | 96 | 64.0 | Beyond Yogyakarta, in Java Island | 103 | 68.7 | ||

| Beyond Java Island | 3 | 8.7 | |||||

| 2 | Age | 5 | Education | ||||

| 12–40 Th | 118 | 78.7 | Junior High School | 50 | 33.3 | ||

| 25–34Th | 19 | 12.7 | Senior High School | 61 | 40.7 | ||

| 35–44 Th | 6 | 4.0 | Diploma | 12 | 8.0 | ||

| 45–54 Th | 6 | 4.0 | Bachelor | 21 | 14.0 | ||

| 55–64 Th | 1 | 0.7 | Postgraduate | 1 | 0.7 | ||

| Others | 5 | 3.3 | |||||

| 3 | Marital Status | 6 | Frequency of Visits | ||||

| Married | 29 | 19.3 | 1 time | 72 | 48.0 | ||

| Unmarried | 121 | 80.7 | 2–3 times | 62 | 41.3 | ||

| > 3 times | 16 | 10.7 | |||||

| Questionaire Item/Likert Scale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Questionaire Item/Likert Scale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | % | F | % | F | % | F | % | F | % | F | % | F | % | F | % | ||

| Tourism Demand (X1) | Tourism Supply (X2) | ||||||||||||||||

| Souvenirs | 8 | 5.3 | 17 | 11.3 | 779 | 52.6 | 46 | 30.7 | Educational tourism | 7 | 4.7 | 7 | 4.7 | 73 | 48.7 | 63 | 42.9 |

| Transportation | 13 | 8.7 | 31 | 20.7 | 58 | 38.7 | 48 | 32.0 | Transportation | 8 | 5.3 | 28 | 18.7 | 88 | 58.7 | 26 | 17.3 |

| Pilgrimage Activities | 20 | 13.3 | 50 | 33.3 | 64 | 42.7 | 16 | 10.7 | Accomodatiom | 14 | 9.3 | 30 | 20.0 | 77 | 51.3 | 29 | 19.3 |

| Learn and Culture | 10 | 6.7 | 30 | 20.0 | 77 | 51.3 | 33 | 22.0 | Special needs facilities | 6 | 4.0 | 10 | 6.7 | 97 | 64.7 | 37 | 24.7 |

| Conference/meetiing | 3 | 2.0 | 20 | 13.3 | 83 | 55.3 | 44 | 29.3 | Toilet | 10 | 6.7 | 21 | 14.0 | 85 | 56.7 | 34 | 22.7 |

| Learn new language | 4 | 2.7 | 23 | 15.3 | 80 | 53.3 | 43 | 28.7 | Souvenirs | 8 | 5.3 | 23 | 15.3 | 77 | 51.3 | 42 | 28.0 |

| Information Services | 28 | 18.7 | 72 | 48.0 | 39 | 26.0 | 11 | 7.3 | Photographers services | 20 | 13.3 | 46 | 30.7 | 67 | 44.7 | 17 | 11.3 |

| Culinary servuces | 22 | 14.7 | 64 | 42.7 | 50 | 33.3 | 14 | 9.3 | Parking area | 10 | 6.7 | 52 | 34.7 | 72 | 48.0 | 16 | 10.7 |

| Learn new tcehnology | 10 | 6.7 | 29 | 19.3 | 82 | 54.7 | 29 | 19.3 | Culinary services | 7 | 4.7 | 29 | 19.3 | 86 | 57.0 | 28 | 18.7 |

| Photographer services | 24 | 10.0 | 46 | 30.7 | 61 | 40.7 | 19 | 12.7 | Information services | 6 | 4.0 | 22 | 14.7 | 88 | 58.7 | 34 | 22.7 |

| Tourism Activities (Y) | Tourism Experience (Z) | ||||||||||||||||

| Pilgrimage activities | 5 | 3.3 | 11 | 7.3 | 91 | 60.7 | 43 | 28.7 | Leraning language | 19 | 12.7 | 64 | 42.7 | 49 | 32.7 | 18 | 12.0 |

| Conference/meeting | 7 | 4.7 | 33 | 22.0 | 86 | 57.3 | 24 | 16.0 | Learning art and culture | 10 | 6.7 | 35 | 23.3 | 73 | 48.7 | 32 | 21.3 |

| Learn history | 19 | 12.7 | 58 | 38.7 | 65 | 43.3 | 8 | 5.3 | Learning new technology | 6 | 4.0 | 37 | 24.7 | 67 | 44.7 | 40 | 26.7 |

| Learn new language | 1 | 0.7 | 33 | 22.0 | 91 | 60.7 | 25 | 16.7 | Learning history | 9 | 6.0 | 45 | 30.0 | 62 | 41.3 | 34 | 22.7 |

| Learn art and culture | 20 | 13.3 | 49 | 32.7 | 68 | 54.3 | 13 | 8.7 | Pilgrimage activities | 26 | 18.0 | 61 | 40.7 | 44 | 29.3 | 18 | 12.0 |

| Field study/research | 2 | 1.3 | 16 | 10.7 | 79 | 52.7 | 53 | 35.3 | Involved with local communities | 14 | 9.3 | 45 | 30.0 | 64 | 42.7 | 27 | 18.0 |

| Learn new technology | 2 | 1.3 | 10 | 6.7 | 74 | 59.3 | 64 | 42.7 | |||||||||

| Validity Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questionaire Item | Correlated-Item Total Correlation | Questionaire Item | Correlated-Item Total Correlation | Questionaire Item | Correlated-Item Total Correlation | Questionaire Item | Correlated-Item Total Correlation |

| X1.1 | 0.651 | X2.1 | 0.610 | Y1 | 0.592 | Z1 | 0.759 |

| X1.2 | 0.458 | X2.2 | 0.546 | Y2 | 0.774 | Z2 | 0.883 |

| X1.3 | 0.791 | X2.3 | 0.758 | Y3 | 0.757 | Z3 | 0.841 |

| X1.4 | 0.512 | X2.4 | 0.636 | Y4 | 0.678 | Z4 | 0,724 |

| X1.5 | 0.386 | X2.5 | 0.829 | Y5 | 0.460 | Z5 | 0.666 |

| X1.6 | 0.791 | X2.6 | 0.755 | Y6 | 0.783 | Z6 | 0.594 |

| X1.7 | 0.486 | X2.7 | 0.787 | Y7 | 0.418 | ||

| X1.8 | 0.508 | X2.8 | 0.780 | ||||

| X1.9 | 0.548 | X2.9 | 0.861 | ||||

| X1.10 | 0.791 | X2.10 | 0.612 | ||||

| Reliability Test | |||||||

| Reseach Variable | Cronbach Alpha | ||||||

| X1 | 0.743 | ||||||

| X2 | 0.771 | ||||||

| Y | 0.756 | ||||||

| Z | 0.785 | ||||||

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t (Partial Effect) | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (Regression Coefficient) | Standard Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 13.961 | 1.693 | 8.249 | 0.000 | |

| Tourism Demand (X1) | −0.045 | 0.058 | −0.066 | −0.780 | 0.437 |

| Tourism Supply (X2) | 0.263 | 0.054 | 0.411 | 4.855 | 0.000 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | Df (Degree of Freedom) | Mean Square | F (Simultaneous Effect) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 200.449 | 2 | 100.225 | 12.911 | 0.000 a |

| Residual | 1141.124 | 147 | 7.763 | ||

| Total | 1341.573 | 149 |

| Model | R (Determinant Coefficient) | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Standard Error of the Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.451 a | 203 | 192 | 3.40011 |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t (Partial Effect) | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (Regression Coefficient) | Standard Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 3.224 | 2.202 | 1.464 | 0.145 | |

| Tourism Supply (X2) | 0.095 | 0.064 | 0.117 | 1.471 | 0.143 |

| Tourism Activities (Y) | 0.495 | 0.100 | 0.393 | 4.932 | 0.000 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wijayanti, A.; Damanik, J.; Fandeli, C.; Sudarmadji. Analysis of Supply and Demand to Enhance Educational Tourism Experience in the Smart Park of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Economies 2017, 5, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies5040042

Wijayanti A, Damanik J, Fandeli C, Sudarmadji. Analysis of Supply and Demand to Enhance Educational Tourism Experience in the Smart Park of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Economies. 2017; 5(4):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies5040042

Chicago/Turabian StyleWijayanti, Ani, Janianton Damanik, Chafid Fandeli, and Sudarmadji. 2017. "Analysis of Supply and Demand to Enhance Educational Tourism Experience in the Smart Park of Yogyakarta, Indonesia" Economies 5, no. 4: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies5040042

APA StyleWijayanti, A., Damanik, J., Fandeli, C., & Sudarmadji. (2017). Analysis of Supply and Demand to Enhance Educational Tourism Experience in the Smart Park of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Economies, 5(4), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies5040042