1. Introduction

Seetanah (

2011) claim that there remain a number of scholars who question the relationship between tourism and economic growth (

Oh 2005;

Lee 2006;

Brau et al. 2007;

Figini and Vici 2009), the scientific literature nevertheless is practically unanimous in considering tourism a driver of economic development, not in the least in terms of creating jobs, contributing to the balance of payments, and providing local income to tourist destinations (

Lea 1988;

Sinclair 1998;

Balaguer and Cantavella-Jordá 2002;

Cuadrado-Roura and López 2011;

Nieto et al. 2016). In fact, numerous studies that analyze the impact of tourism on national and regional economies highlight its positive influence on not only economic growth, but also social and cultural development (

Kim et al. 2006;

Seetanah 2011). As

Song et al. (

2012) affirm, the study of tourism from an economic perspective is a relatively recent phenomenon, in turn drawing from a relatively young economic sector itself (

Guthrie 1961;

Gerakis 1965;

Gray 1996). The global relevance

1 international tourism has acquired over the past few decades has awakened an interest on the part of specialists who, in addition to publishing an extensive bibliography of this field in a relatively short period (

Dwyer et al. 2010;

Tribe 2011), have inquired more deeply into the relationship between tourism and the economic reality of today’s world. It is understandable, then, that in recent years numerous studies have focused on the nature of tourism throughout the global economic crisis, which started in 2008 (

Eugenio-Martín and Campos-Soria 2014;

Stylidis and Terzidou 2014).

Among these authors, there is significant agreement surrounding the impacts of the economic crisis on tourism. In addition to the well-known impacts of economic recession—a decline in GDP, a rise in unemployment, reduction of public and private investment, social cuts, etc.—the tourism sector experiences its own impacts, such as a change in the demand and behavior of tourists, a reduction of tax revenue from tourism, and a decrease of international tourist arrivals. (

Smeral 2009;

2010;

Eugenio-Martín and Campos-Soria 2014). In the case of Southern European countries, such as in Spain, Greece, Portugal or Italy where international tourism plays an important role, the crisis has threatened the very fundaments of the economy, adding to greater instability and adverse effects (

Boukas and Ziakas 2013;

Papatheodorou and Arvantis 2014;

Cellini and Cuccia 2014). In the case of Spain, the scientific literature has already abundantly demonstrated the importance of tourism as a key economic sector—there is no further need to investigate this point in this study. More appropriately, this study takes into consideration scholarship regarding the nature of tourism, predominantly international, in instances of economic decline, with the aim of determining patterns of behavior that may inform the design of more efficient tourism management strategies (

Henderson 2007).

Following this line of reasoning, the conclusions made by

Cuadrado-Roura and López (

2011) and

Nieto et al. (

2016) about the impact of the economic crisis on Spain’s tourism are of particular relevance to this study. The authors inquire into the contribution of specific tourist activities to the Spanish economy, emphasizing their impact on GDP—making up nearly 10% of its total—their capacity to generate employment, and their role in compensating the trade deficit. Despite the perceived strengths of the sector, the authors also note a number of weaknesses, such as the cyclical fluctuations stemming from changes in demand, both nationally and internationally, in the wake of the economic crisis; the low levels of productivity created by the hospitality sector; or, the increase of local prices for tourism products, which compromises Spain’s competitiveness in the market for beach destinations. In contrast,

Nieto et al. (

2016) argue that the real impact of the economic crisis is not found as much in the decline of tourist arrivals itself, which was very short-lived due to rapid recuperation in the following years, as it is in the decrease of income that resulted from it. Moreover, they emphasize that the continued importance of the sector will depend on the diversification and quality of tourism products. Conscious of the fact that the country’s beach tourism operates in a highly competitive market, they suggest developing other kinds of tourism, such as cultural tourism, which valorize the cultural and natural heritage of the country.

Cultural tourism takes up a central position in the scientific literature as a driver of socioeconomic development, capable of establishing new tourist destinations. In 2015, the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) organized the World Conference on Tourism and Culture to acknowledge these new alliances between tourism and culture. During this conference, the debate highlighted not only the ability of cultural tourism to protect cultural heritage, but equally so its ability to promote sustainable development, stimulate job growth, and raise awareness among the local population. Taking into account these capabilities, there has been a desire to investigate more seriously the nature of cultural tourism of an international character in Spain throughout the economic crisis. Practically all studies analyze the macroeconomic performance of tourism, yet lack a focus on different modalities according to the motivation of travelers, especially international ones.

More precisely, the increased number of international tourists who visited Spain in the period of 2006–2016 has undoubtedly contributed to the country’s macroeconomic recovery, as tourist spending, the increased contribution of tourism to overall GDP, and the country’s job growth attest to. However, within this trend, have all kinds of tourism acted in the same way? Have all tourist typologies contributed to the Spanish economy equally from a macro point of view? Has beach tourism remained the principal form of tourism? Faced with the impossibility of investigating all the variables of tourism, and by extension answering all these questions, this study limits itself to forms of cultural tourism that are consumed by international tourists in Spain. The goal is to analyze how the economic crisis has affected this form of tourism, which, according to the scientific literature, has proven to be vital to economic development of destination localities, and to determine patterns of behavior in periods of economic decline that may help to shape more effective tourist planning strategies. More precisely, the main goal of this study is to analyze the behavior of international tourists whose principal motivation consists of exploring culture, before, during, and after the economic crisis. For this purpose, the study focuses on the number of international cultural tourism arrivals and the spending that they generate, compared to the total number of international tourist arrivals and their generated spending.

Even though the Spanish Ministry of Tourism in recent years has launched a number of projects that promote tourism diversification, actual tourist development since the 1970s has tended to focus on recreational forms of tourism, such as beach tourism. Our hypothesis departs from the idea that economic instability in Spain affects to a larger extent those forms of tourism, such as cultural tourism, that are less territorially rooted, and despite their ability to socioeconomically develop tourist localities, generate less impact on the economy and have less international repercussions than beach tourism. Verifying this hypothesis will first and foremost reveal the weaknesses of cultural tourism, and sustain the necessity for measures that strengthen and consolidate the sector. In order to fulfill the objective of this study, verify the working hypothesis, and draw representative conclusions, our methodology comprises two secondary objectives (SO), which have been developed to structure the current research:

2. Methodology

In order to test the hypothesis as well as the research questions, the methodology of this study is structured in two stages that deal with two different methodologies. First, combining qualitative and quantitative techniques, this study constructs an economic contextualization of the period of 2006–2016, emphasizing the evolution of the economic crisis in Spain, and the nature of the international tourism sector from a macroeconomic perspective. For the purpose of this first research stage, the study analyzes a specialized bibliography and processes statistical data from the following reports and statistical sources of the Institute of Tourism Studies:

Spanish Touristic Movements (Movimientos Turísticos Españoles, FAMILITUR). The statistical unit of the General Sub-directorate of Touristic Knowledge and Studies (Subdirección General de Conocimiento y Estudios Turísticos), which gathers data on the travels of residents into Spain. A broad sample of household questionnaires forms the basis of these data. Over the course of a three-month period, a total of 16.500 households across all regions of Spain were questioned, accounting for a total of 66.000 questionnaires, conducting in-person as well as over the phone.

Touristic Movement at Borders (Movimiento Turístico en Fronteras, FRONTUR). The statistical unit of the General Sub-directorate of Touristic Knowledge and Studies (

Subdirección General de Conocimiento y Estudios Turísticos), which gathers data on the entry of non-residents into Spain (

Institute of Tourism Studies 2017a). The objective of this survey is to quantify and characterize the flows of visitors entering Spain. Since May 1996, the survey has collected data from administrative sources, both public and private, that record border traffic. This includes manual counts of vehicles and people, as well as sample surveys at access points (roads, airports, seaports, and rail stations). On an annual basis, the survey comprises approximately 2,200,000 manual counts as well 360,000 personal surveys. This source has proven particularly important for this study in that it shows the total number of international tourists who have visited Spain during the period of analysis, as well as the total number of international tourists whose principal motivation was of a cultural nature.

Tourist Expenditure Survey (Encuesta de Gasto Turístico (EGATUR). The statistical unit of the General Sub-directorate of Touristic Knowledge and Studies (

Subdirección General de Conocimiento y Estudies Turísticos), which gathers data on the spending of non-resident visitors in Spain (

Institute of Tourism Studies 2017b). This survey is directly related to FRONTUR, which provides the technical, logistical, and operational support as well as the overarching framework for this expense survey. Every month, this survey interviews a sample of 106,300 travelers, 19,000 of which are gathered at highway border points, 80,000 at airports, 6,500 at seaports, and 800 at train stations)

Satellite Account of Tourism in Spain (Cuenta Satélite del Turismo en España, CSTE) ofb the Institute of Tourism of Spain (

Insituto de Turismo de España). An economic database related to tourism, designed as a satellite to the main system of National Accounts, which allows for the measurement of the impact of tourism on the national economy of Spain. The CSTE is produced by the General Sub-directorate of National Accounts of the National Institute of Statistics (

Subdirección General de Cuentas Nacionales del Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE). The Satellite Account of Tourism in Spain can be described as a combination of accounts and tables, derived from the main national accounting methodologies, which present the different economic parameters (supply and demand) of tourism, in an interrelated form, according to a given reference date (

Institute of Tourism Studies 2017c).

Second, employing a quantitative methodology, this study extracts and analyzes data from the Register of Cultural Statistics of the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sports of Spain (

Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports 2017). This source gathers a selection of the most representative data in the realm of culture from various statistical sources and aims to facilitate objective knowledge of the state of culture, as well as its evolution, in Spain. More specifically, this source presents data from the Resident Tourism Survey (ETR/FAMILITUR), and the Tourist Expenditure Survey (EGATUR), which is a part of the National Statistical Plan, which was developed by the National Institute of Statistics in 2015. The Register of Cultural Statistics of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports of Spain shows international tourist arrivals with cultural motivation, and it intends to emphasize the importance of the cultural sector as a driver of such large economic contributors as Tourism (

Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports 2017).

One of the main contributions of this study is exactly its focus on statistical data from the Register of Cultural Statistics by the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports. Indeed, this study aims to systematically code these unprocessed data in an effort to attain high representativeness—a feat that would be hard to do with a separately designed survey and sample. The statistical processing of these data thus opens the door to scientifically evaluate the impact of international cultural tourism, to which little study has been dedicated in Spain. Understanding its behavior will directly contribute to the development of strategic planning efforts, which will help reinforce Spain’s cultural tourism sector and cement its position as a cultural destination. In the end, this study attempts to demonstrate statistically that cultural tourism generates legitimate tourist flows for the Spanish economy, which, if managed appropriately, can position them as a valuable alternative to more conventional and currently dominant beach tourism.

From a methodological standpoint, this study tries to, on the one hand, represent international flows of cultural tourism in Spain. For this purpose, and in order to facilitate the interpretation of these data and their synthetic visualization, this study has configured a number of chronological tables and graphs. On the other hand, this study also tries to analyze the behavior of cultural tourism during the period of 2003–2014 with the objective of determining variations between periods of economic crisis versus periods of non-crisis. To this end, T-tests have been developed for independent samples to compare each of the variables of economic crisis and non-crisis. With the help of these methodological results, this study aspires to detect patterns of behavior produced during the global economic crisis that may inform concrete actions of tourism planning.

3. Results

Between 1994 and 2007, Spain experienced a period of historic significance in terms of macroeconomic expansion: GDP growth rose about 70%, with annual growth rates of approximately 4% (

Pereda et al. 2009); public accounts closed with surpluses in the 2005, 2006, and 2007 tax years; and, public debt dropped to below 40% of the GDP, compared to 60% of the European Union. These outstanding economic data were accompanied by an inflation rate, which, as

Outes (

2012) affirms, had been the lowest in 30 years, and, above all else, by excellent job growth numbers. The unemployment rate went down from 24.1% and 3.8 million unemployed in 1994, to 8.2% and 1.8 unemployed in 2007; 20.3 million were employed at the time (

Alonso and Furió 2010).

Even though economic indicators already noted some global economic fluctuation throughout the year 2007, it was not until September of 2008 that the crash of the U.S. bank Lehman Brothers triggered a financial crisis that extended across both sides of the Atlantic, rapidly affecting the Eurozone. An official recession was declared on 14 November 2008. This disruption caused a severe structural crisis of the euro currency, as well as the monetary and financial policies of the EU, which in turn, among other consequences, provoked significant distrust among the member states. The Spanish economy plunged into recession in the first trimester of 2009, after having witnessed negative GDP growth for two subsequent trimesters (

Alonso and Furió 2010). In the first place, the Spanish crisis had manifested itself in the bursting of the real estate bubble. The sharp decline in home prices, combined with growing unemployment, forced many homeowners to default on their mortgages. Unable to sell their properties, this generated a wave of forced evictions (

Outes 2012). Second, the crisis caused inflationary and deflationary tensions as a result of an excessive dependence on petroleum imports, as well as monetary policy based on cheap credit. Finally, a severe lack of solidity of the Spanish banks came to light after the relaxation of financial market regulations during the real estate bubble.

The crisis generated dramatic consequences for the Spanish economy. Unemployment, which had reached a historic low in the spring of 2007, with 1.8 million unemployed (7.95% of the active population), reached a historic maximum in 2013, with more than 6.2 unemployed (27.16% of the active population). Moreover, Spain’s public debt climbed to 93.4% of GDP, the risk premium disappeared by the summer of 2011, surpassing its record in 2012 when it registered 616 base points compared to the German bonds at 10 years, and crime reached the highest levels it had ever seen since the economic crisis of 1993. As a result of higher unemployment, instability of the job market, and a loss of purchasing power, significant cuts in public spending were made, particularly in education and health, causing much social unrest and a negative outlook on the future.

Today, macroeconomic data show levels similar to those before the recession, indicating the near-completion of the recovery process. In 2016 Spain’s GDP grew by 3.5% when compared to the previous year, arriving at 1.1 million euros. The low price of oil, the outstanding performance of the tourism sector, the low interest rates, and the adjustment of the government’s budget were the principal drivers of Spain’s economic recovery. As a result, Spain’s GDP has been able to recuperate a 10.7% and 7.8% share of respectively the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union, and the European Union (

CEOE 2016). Even though 475.000 jobs were created, the number of workers remains two million below its maximum according to the Active Population Survey. Despite this positive outlook, there remain a number of factors that hinder a full recovery, for example, the precariousness of labor, the negligible added value of economic activity, the low birth rate, and the limited implementation of new information and communication technologies.

3.1. Main Tendencies of Tourism Activity during the Spanish Economic Crisis According to the Analysis of Macroeconomic Variables

Despite the downward trend of the period of 2006–2016, tourism performed surprisingly well, contributing considerably to the recovery of the Spanish economy by means of tourism income, its contribution to GDP, and the creation of jobs. The relative weight of international tourism proved a significant source of strength, as will be shown later. In 2006, 58.4 million international tourists were registered, compared to 75.3 million ten years later in 2016—a supposed increase of about 28.9%. Since 2013, Spain has been repeatedly breaking the record numbers of foreign tourists as a result of the economic recovery of those countries whose residents visit Spain, especially Germany, France, and the UK, and the political instability of its competitor-countries, such as Tunisia, Morocco, Egypt, and Turkey. Two years in this period are outliers: 2008, with a drop of −8.8% after the start of the global economic recession, and 2016, the year with the highest number of international tourist arrivals ever, 75.3%, which constitutes a 10.4% increase since 2015 (

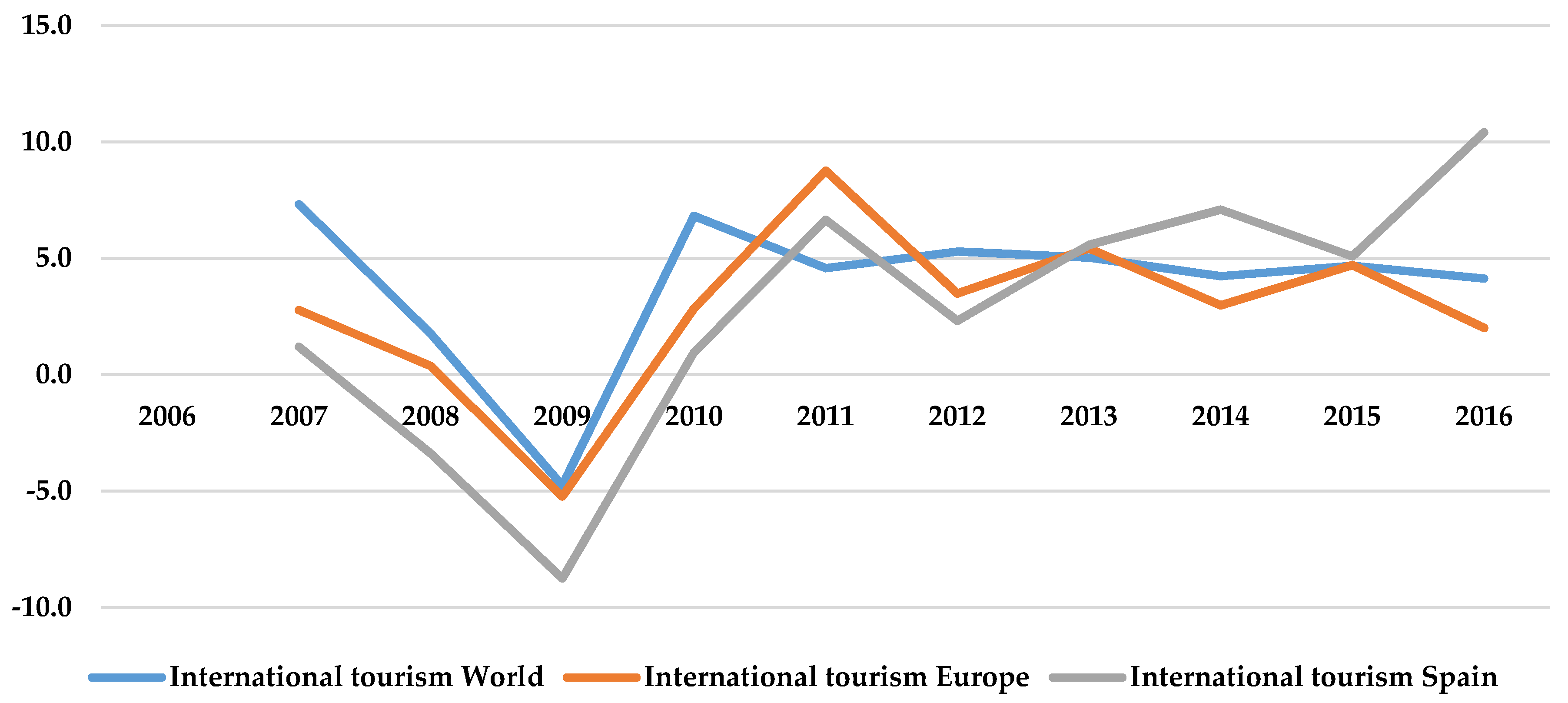

Figure 1). The increased arrival of international tourists was offset by the unusual but negative tendency of Spanish tourist travellers in the same period. Indeed, the year 2010 saw a sharp decline of −6.1% compared to 2009, which in turn had seen a negative growth of −1.7% when compared to 2008. This fact relates to the slower recovery of Spain, which generated smaller spending from residents.

A comparison of these results with those registered by the UNWTO in relation to the arrival of international and European tourists, found in the series

UNWTO Tourism Highlight, provides a number of valuable insights. Already in 2008, the UNWTO witnessed a drop of −3.8% in the number of international tourist arrivals, while in Europe and the rest of the world the decline in visitor numbers was not noted until 2009. In addition, in Spain, two consecutive years of losses were noted, compared to just a single year for Europe and the rest of the world. Thus, one could argue that the decline in international tourism manifested itself first in Spain, and lasted much longer there than in other parts of the world. In contrast, Spain has been experiencing a higher percentage increase in international tourist arrivals, compared to that of Europe and the rest of the world. The year 2016 is especially significant, showing an increase of nearly 10%, when compared to 4.1% and 2% in the rest of the world and Europe respectively (

Figure 1).

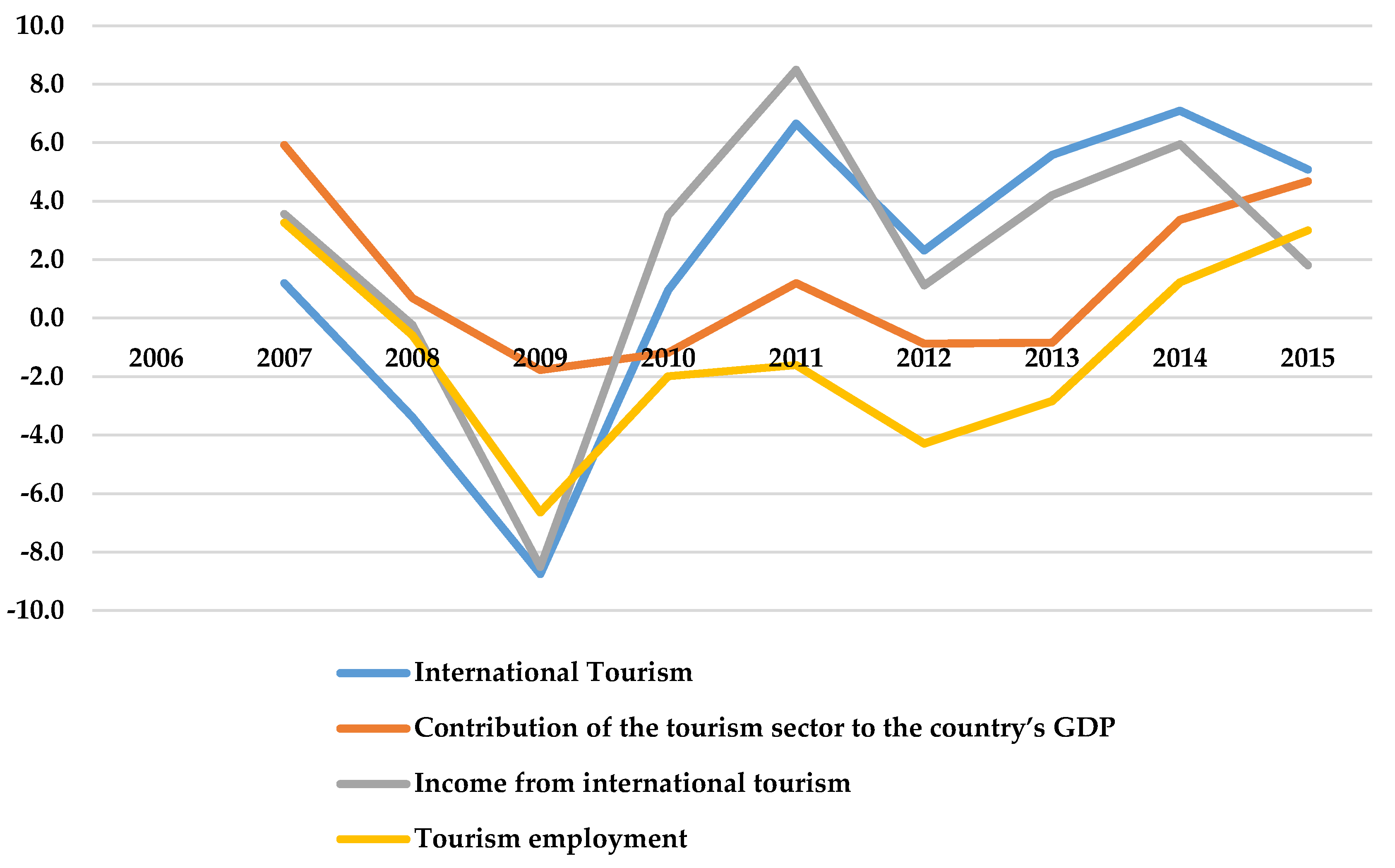

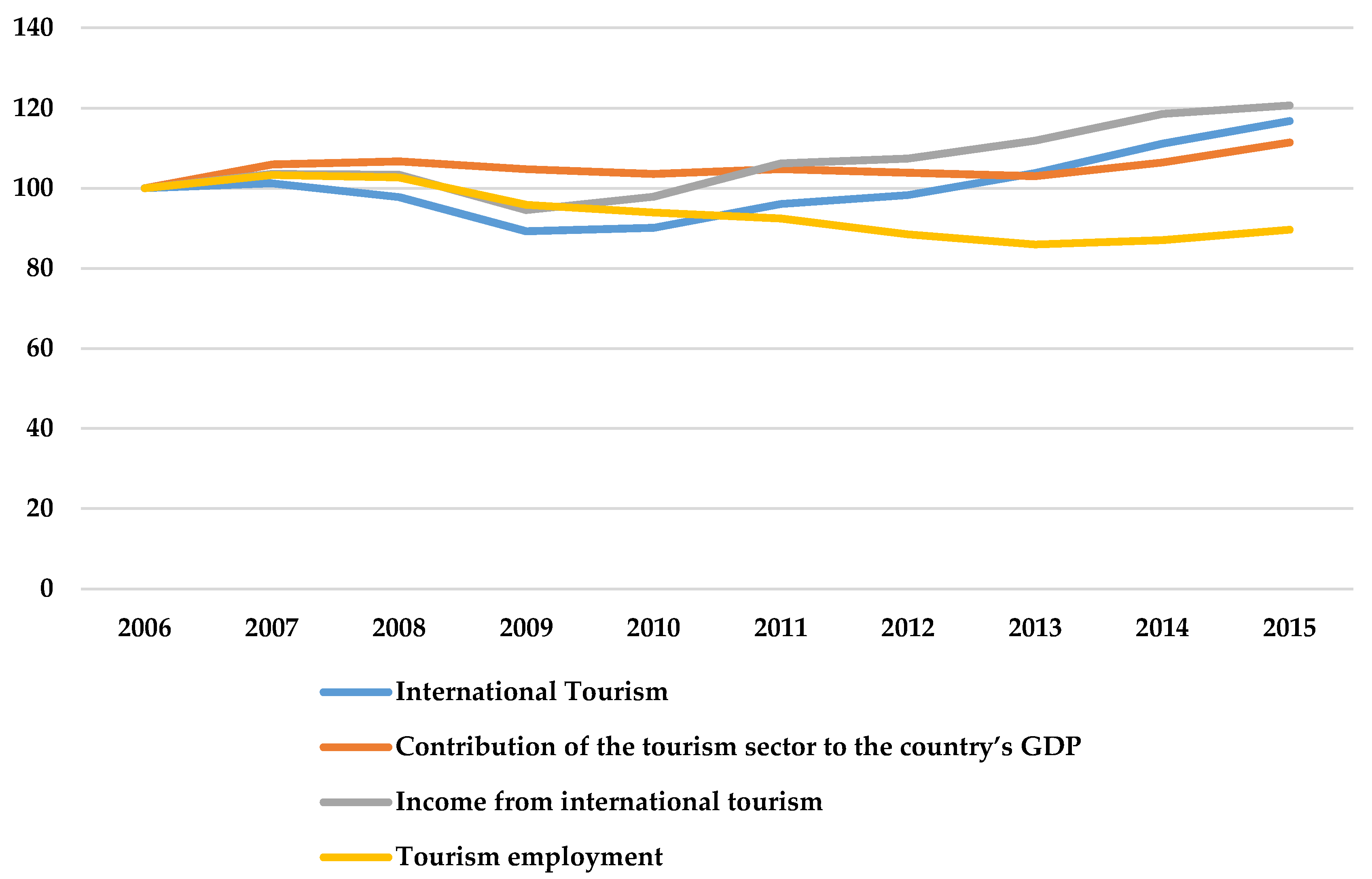

Regarding the income from international tourism, Spain experienced an increase from 42 billion euros in 2006, to 51 billion in 2016, a 22% increase, which also broke the 50 billion mark for the first time in 2015. In the years 2008 and 2009, income from international tourism experienced two years of consecutive negative growth in Spain, −0.2% and −8.5% respectively. As was the case with international arrivals, the decline manifested itself first in Spain, before becoming apparent in Europe and the rest of the world. However, unlike the case before, Spain’s relative income did not surpass that of other European countries or the rest of the world, except for in 2014, when Spain registered 1.5 percentage points of growth ahead of the rest of Europe. Moreover, throughout the entire period of analysis, income from tourism surpasses spending, generating a surplus in the balance of payments. It is noteworthy that since 2014, spending from tourism, despite remaining below incomes, has grown rapidly in terms of percentages (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

During the 2006–2015 period, the contribution of tourism to the Spanish economy (GDP) experienced a percentage increase of 19.6%, from 106,828.6 million euros in 2006 to 119,011 million in 2015. Two biennial periods were marked by negative growth: 2009 (−1.7%) and 2010 (−1.8%), and 2012 (−0.8%) and 2013 (−0.8%). The year 2015 saw the highest number at 119,011 million. On the other hand, the average contribution of the tourism sector to the country’s GDP has been 10.6%, with a minimum of 10.2% in 2010, and a maximum of 11.1% in 2015. These numbers remain close to that of the annual contribution of tourism to world GDP, which fluctuates between 9% and 10%. Moreover, the Satellite Account of Tourism in Spain (CSTE) reveals a noteworthy contribution of tourism to total employment, with the creation of 2.49 million jobs postings in 2015, or, 13.9% of all jobs created in Spain that year. The percentage of total jobs created by the tourism sector has remained above 10% in the period of 2006–2015, surpassing 13% in the last two years.

Nonetheless, the absolute numbers have not reached the same level as in 2010, when 2.9 million jobs, or 15.7% of all jobs, were created by tourism.

These data highlight the important role that the tourism sector has played in the national context, as it has positioned itself as one of the principal drivers of Spain’s economic recovery during the crisis. In addition, these numbers also emphasize the importance the tourism sector has played internationally; as mentioned earlier, Spain received 68.2 million international tourists in 2015, placing it third only to France (84.5), and the United States (77.5), according to the

UNWTO (

2016). Similarly, it also took up the third position in terms of income from international tourism, with a total of 56.5 million USD. The United States occupied first place with 204 million, while China ended second with 114.1 million USD in income from international tourism (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

3.2. Nature of International Cultural Tourism in Spain (2006–2014)

With the objective of obtaining comparable results about the nature of cultural tourism in Spain, this study has analyzed the indicator “entry of international tourists with primarily cultural motivations as well as the spending their generate during their stay in Spain”, taken from the Register of Cultural Statistics of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports of Spain. For the purpose of this study, this indicator was interpreted as a trip to Spain that hinges on culture. This approximates most closely a type of cultural tourism of international origin.

Before unpacking the information contained within this indicator, it may be helpful to review some of the key concepts treated in this study, as defined by the Register of Cultural Statistics of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports of Spain. The following are among the most used:

International tourist. A person who does not reside in Spain, travels to this country and spends at least one night, regardless of their country of residency. This does not include the following: persons who reside in Spain and leave or return to the country, and international visitors who enter or leave without having spent at least one night there. This does include Spanish nationals who have their residency abroad and visit Spain.

Trip. The displacement of a person from their usual surroundings for at least one overnight stay. The usual surroundings are the municipality where they have their primary residency (home). Excluded from this definition are displacements to work and those persons who maintain a residency longer than 12 consecutive months. Also excluded are those persons for whom traveling is a part of their daily work routine, as well as excursions, that is, displacements of one day without overnight stay.

Culturally motivated trip

2. Trips taken around Spain, which, according to the person taking them, was initiated mainly for cultural purposes.

Total spending. Includes all the expenditures made on the trip. This definition is especially important in the case of international tourists, since they include expenditures prior to the trip such as an airline ticket or a tourist bundle.

3.2.1. Nature of International Tourism in Spain “with Primarily Cultural Motivations”: Number of Cultural Tourists and Their Generated Spending

During the 2006–2014 period, a total of 83.8 million international visitors with primarily cultural motivations were registered, comprising 12.7% of the total number of registered international tourists in Spain (

Table 1). The number grew from 5.9 million international visitors with primarily cultural motivations in 2006, to 7.1 million in 2014, experiencing a total growth of 16.9% for the interval analyzed. The number of international tourist arrivals with primarily cultural motivations experienced three periods of decline: in 2005 (−31.9%), during a period of economic consolidation; in 2009 (−25%); and, 2012–2014 (−11.6%; −9.2%; −4.15%), two periods of full economic recession.

International tourists with primarily cultural motivations spent 72.437 billion euros throughout the period of 2003–2014, which makes up 12.1% of total spending by international tourists over the same period (

Table 2). During the period analyzed, the touristic spending increased by 52.9%, from 4.907 billion euros in 2003, to 7.506 billion in 2014. There were four years registering negative growth rates: 2005, which saw a decrease of 44.7%, produced during a period of economic consolidation, compared to 2009 (−22.3%), 2012 (−10.7%), and y 2013 (−0.8%), periods of full economic recession. In contrast, two years of significant growth of international tourist spending correspond with a higher number of international tourist arrivals: 2007 (53.2%), and 2011 (42%). Moreover, one of the most relevant observations in regards to international cultural tourism is the spending increase of 52.9%: from 4.907 billion euros in 2003, to 7.506 billion in 2014.

3.2.2. Behavior of International Tourism with Primarily Cultural Motivations (2003–2016)

In order to determine the behavior of international tourism with primarily cultural motivations in Spain, this study compares two items:

These two items were compared in function of to the following variables:

Variable 1. International tourists;

Variable 2. International tourists with primarily cultural motivations;

Variable 3. Total spending of international tourists;

Variable 4. Spending of international tourists with primarily cultural motivations;

Variable 5. Average spending per international tourist; and,

Variable 6. Average spending per international tourist with primarily cultural motivations.

In order to analyze these data,

T-tests were developed for independent samples to compare the variables in the two groups (items). The results obtained from the Student’s

T-test for independent samples (

Table 3) shows no difference between the two groups (the years of non-crisis vs. crisis) for the number of general visitors (t(10) = −1.91,

p = 0.09) and for the number of visitors with primarily cultural motivations (t(10) = 0.38,

p = 0.71). Nor was there a difference between the groups for total spending generated by general visitors (t(10) = −1.04,

p = 0.32) or for spending generated by visitors with primarily cultural motivations (t(10) = −1.72,

p = 0.12). Still, while the average spending generated by visitors with primarily cultural motivations remains roughly the same in the years of non-crisis as well as for those of crisis (t(10) = −99,

p = 0.35), there was a difference in the average spending generated by general visitors (t(10) = −2.62,

p = 0.03). Concretely, this study observes that the spending generated by general visitors was greater in years of crisis than in the years of non-crisis.

4. Discussion

The reliance of this study on data from the Register of Cultural Statistics of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports of Spain does present a few caveats in regards to the representativeness of results and the richness of conclusions. First, there are clear limitations to the comparability of the indicators. Each one comprises different items, which, with a higher number of cases, cannot be compared among one another as a direct result of their design. Moreover, whereas the statistics and official reports from the Institute of Tourism Studies are up to date (2016), the same cannot be said of the data from the Register of Cultural Statistics of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports of Spain, which do not include the years 2015 and 2016. This prevents a full view of the nature of the cultural tourism during the last two years, which cannot be completed and verified until the most recent data are released. It is therefore important to remember the provisionary character of this study’s conclusions. Finally, a number of the conclusions derived from analyzing these data do not allow for absolute corroboration of the research questions and hypothesis; more scientific research based on additional data is needed to complete this study.

The results of this analysis into the behavior of international cultural tourism show that there are hardly any differences between the period of economic crisis and that of non-economic crisis, at least in terms of the number of visitors, total tourist spending, and average tourist spending. This finding does not corroborate the first part of this study’s hypothesis, which proposed that economic instability in Spain would affect to a larger extent those types of tourism, such as cultural tourism, which are less rooted in the geographic landscape than, for example, beach tourism. Cultural tourism has remained anti-cyclical throughout the period analyzed in this study, although it is true that events such as the San Jacobeo Holy Year, discussed next, may have skewed the results. Nonetheless, this comparative analysis does support the second part of the original hypothesis, which proposed that cultural tourism, despite its ability to develop destinations from a socio-economic point of view, has a lesser impact on the overall economy, and a smaller international projection than, for example, beach tourism. In the period observed, the average spending generated by international tourists is higher in years of crisis than in years of non-crisis, while the spending generated by international tourists with primarily cultural motivations is maintained throughout years of crisis and non-crisis. In fact, the descriptive statistical analysis shows that international tourism grew by 27.7% during the period analyzed, as opposed to 17.7% growth for cultural tourism. Similarly, the analysis also demonstrated that international tourism experienced only two years of negative growth, 2008 (−3.4%) and 2009 (−8.8%), as opposed to cultural tourism, which experienced 5 years of negative growth: 2005 (−31.9%), 2009 (−25%), 2012 (−11.6%), 2013 (−9.2%) , and 2014 (−4.1%).

In 2004, international tourism with primarily cultural motivations experienced a decrease of −31.9%, compared to the year before (2003). This number remains difficult to explain, as this happened to be a period of economic growth. One potential explanation, as pointed out by

Manzanera (

2004) and

Araujo Cardalda (

2009), is that 2004 was the Holy Year of San Jacobeo, which could have influenced the 22% increase in the arrival of international tourists and the immediate sharp decline of −31.9% once over. In fact, the Pilgrim’s Office in Santiago de Compostela registered a total of 179,944 pilgrims, 23% of which were foreigners (

Oficina del Peregrino 2017). Interestingly enough, the year 2010—already in full economic crisis—was also the Holy Year of San Jacobeo. As in the year 2004, the numbers show a 30% increase of international cultural tourist arrivals compared to 2009. However, unlike the year 2005, the following year (2011) did not witness a decrease, but instead a further increase of 23.5%. Perhaps a slight economic recovery in the originating countries of cultural tourists (the UK, France, and Germany) may explain the absence of a drop in visitors after the San Jacobeo Holy Year.

It is certain that, as Europe continues its economic recovery, the number of international arrivals of tourists with primarily cultural motivations begins to decline, reaching figures similar to those prior to the economic crisis. It remains difficult to explain why Spanish cultural tourism witnessed such as decline in the last two years, keeping into account the country’s wealth of cultural heritage and the diversity of its cultural offerings on the one hand, as well as the decline of competing countries due to political instability on the other hand. It certainly would be interesting to investigate whether or not public (and private) policies surrounding cultural tourism are efficient, particularly in channeling the diverted flow of tourists no longer visiting countries such as Tunisia, Egypt, or Turkey. These uncertainties not withstanding, the results from this study’s section on tourist spending do show a direct correlation between the decline of international cultural tourist arrivals, and the decline in tourist spending. However, despite the decrease in international cultural tourist arrivals of −4.1% in 2014, spending remained positive. The forthcoming publication of 2015 and 2016 data may clarify whether this is due to an isolated event or a trend that might point towards other conclusions.

It is true that international tourists with primarily cultural motivations were affected the same by the economic crisis as international tourists who occasionally engage in cultural activities during their stay, but their respective nature has been different. The impact of the economic crisis has not affected cultural tourism in a “better” or “worse” way, but rather in different ways. The decline of tourist numbers has been limited, although with higher rates of decline that has been followed by periods of significant percentage increases. More worrisome is the decline of international visitors in a period where records numbers have been registered. Given the lack of more detailed studies, one could provisionally argue that this outcome is due to the fact that cultural tourism is a more stable yet still small niche market in a country like Spain that is specialized in recreational (beach) vacations. Even more concerning is the perceived incapacity of cultural tourism to grow, despite the current excellent opportunities.

5. Conclusions

While there exist numerous publications that analyze tourism from a macroeconomic perspective, as mentioned in the introduction, few—at least in the case of Spain—take into account cultural tourism. Despite this difficulty, it is nonetheless meaningful to briefly position this study within the field of specialized literature.

First and foremost, it must be emphasized that the results of this study once again underscore the importance of the tourist sector to the economy of Spain—both in times of growth, as well as decline. In this sense, the study positions itself in the line of many other works that investigate the key role tourism plays in both national and regional economies (

Lea 1988;

Sinclair 1998;

Balaguer and Cantavella-Jordá 2002;

Kim et al. 2006;

Seetanah 2011), and in particular the role it plays in times of significant economic downturn (

Cuadrado-Roura and López 2011;

Nieto et al. 2016). In the particular case of Spain, tourism has acted as an outstanding driver of economic recovery, contributing to the country’s GDP, creating jobs and stabilizing the country’s balance of payments—even so at a slower rate than was the case in previous decades, as pointed out by

Cuadrado-Roura and López (

2011), and

Nieto et al. (

2016). Despite the strength of the sector, the effects of the crisis have impacted Spain’s tourism, producing practically the same consequences (decline of international tourist arrivals; changes in consumer behavior in tourism; decline in spending; etc.) as observed in the works by

Boukas and Ziakas 2013;

Papatheodorou and Arvantis 2014;

Cellini and Cuccia 2014).

The conclusions drawn by

Nieto et al. (

2016) about how the crisis has affected the nature of international tourist arrivals in Spain coincides with the results obtained from this study, at least for the entry of international tourists who occasionally engage in cultural activities during their visit. The number of tourists declines in instances where the recession is more acute, but is limited in duration to one or perhaps two years before experiencing significant increases once again in successive periods. The results also coincide with the conclusion that the UK, Germany and France are the principal countries of origin for international tourists visiting Spain.

Even though there is hardly any literature that reviews the nature of international cultural tourism from a demand point of view,

Nieto et al. (

2016), in their analysis about the economic crisis and international tourism in Spain hint at a possible connection between demand, strength of the tourism sector, and the diversification of tourism products. The authors conclude that more robust character of the tourism sector in light of the economic crisis traces its roots back to efforts to diversify Spanish tourism products, which has attempted to offer other kinds of products such as cultural tourism in addition to more traditional types of recreational (beach) tourism. The interpretation of these data gathered in this study indicates that cultural tourism, at least in terms of international tourist arrivals, has indeed remained stable throughout the crisis, even though it has not grown significantly ever since. Realistically, has this kind of tourism contributed significantly to the economic recovery of Spain? Is there a tourism offer that is capable of channeling the foreign ‘cultural tourist’? We agree with

Nieto et al. (

2016) that it is important to stimulate alternative tourism products in addition to beach tourism, without diminishing the latter. Or, in other words, it is important to plan diversification of tourism products in such a way that consciously takes into account the relative weight different kinds of tourism (recreational, cultural, etc.) carry in the overall economy, as well as adapting public and private tourism policies, which may have been mobilized for this purpose.