Abstract

The global city thesis and the migration thesis concern two important dimensions of the impacts of contemporary globalization on cities. The two theses are intrinsically linked. The central question is how we should approach migration in the new context of the global city, and how we should articulate their interrelationships. To address this question, we construct an integrative analytical framework linking global city and migration, and empirically apply it to Sydney. We build a set of indexes to measure global competitiveness, global migration, and global mobility of communities across global Sydney. The findings reveal that global competitiveness—the defining capacity of Sydney as a global city—has very weak association with global migration that measures the stock of foreign born population, but has very strong association with global mobility that measures the people movement in recent years. These findings call for a redefinition of migration to incorporate people movement to better capture the interplay between global city and migration.

JEL Classifications:

R11; R12

1. Introduction

Sydney is Australia’s leading global city. It is an important node in the global city network, linking Australia with the world economy. Sydney is also Australia’s foremost gateway city for migration. The global city thesis and the migration thesis for Sydney have been developing in parallel. The global city thesis has been economic-centric, focusing on Sydney’s growing capacity of global services, in particular, of advanced producer services [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. The advanced producer services include finance/banking, insurance, accountancy, advertising, law, and management consultancy, etc.; they are defining Sydney’s global city status according to the global city discourse [10,11,12,13]. On the other hand, the migration thesis has focused on the spatial settlement of migrant groups across the Sydney region or their socio-economic structures [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. There is a need to address the association between the two theses.

We argue that the global city thesis and the migration thesis are intrinsically linked. They reflect two important dimensions of the impacts of contemporary globalization on cities. Sydney’s rise as a global city is inseparable from its migration dynamics; both reflect Sydney and Australia’s increasing integration with the world. The question is how they are interrelated. In order to articulate the nexus between global Sydney and migration, we construct an integrative analytical framework linking them. Underpinned by the framework, we make a comprehensive examination of Sydney’s global services, foreign born population, and people movement. This is made through building three sets of indexes: global competitiveness index (GCI), global migration index (GMI), and global mobility index (GloMo) for the local communities across global Sydney. The findings provide new insights into the interrelationship between global Sydney and migration. They also call for a redefinition of migration in global Sydney, moving from the conventional perception of foreign born population to incorporate increasing people movement in contemporary globalization.

This article is organized as follows. Following this introduction, next section provides a literature review on the theses of global Sydney and migration respectively, to point out the gap in the scholarship and the need of this study to bridge them. The section on methods explains how this study is carried out, including the definition, calculation and data for the three indexes (GCI, GMI, and GloMo). The results offer the spatial patterns and statistical relationships of the three indexes across global Sydney. The last section concludes with a discussion on the nexus between global Sydney and migration, and suggests a redefinition of migration in global Sydney.

2. Global Sydney and Migration

2.1. Global Sydney

Global Sydney constitutes part of the broader global city discourse, which has responded to the increasing interaction between contemporary globalization and cities. The global city discourse has focused on the strategic roles of command and control played by many major urban nodes in the integrated world economy, in particular, on their capacity of providing advanced producer services [10,12,13,22,23,24]. The global city discourse has included Sydney as a member city in the global city network, and has ascertained Sydney’s evolving competitive position in the global context [12,13,22,23,25,26,27,28]. Empirically, the Globalisation and World Cities (GaWC) research program at Loughborough University measured the advanced producer services of world cities and thus ranked them in 2000, 2004, 2008, 2010 and 2012 respectively [29]. Cities were classified into Alpha, Beta, and Gamma levels. In 2000 and 2004, Sydney was classified as an Alpha city (very important world cities that link major economic regions and states into the world economy); in 2008, 2010 and 2012, Sydney was classified as an Alpha+ city (highly integrated cities that complement London and New York, largely filling in advanced service needs for the Pacific Asia). Informed by the GaWC’s ranking of world cities by advanced producer services, an Urban Immigrant Index was created to measure world cities by immigration stock, in which Sydney was ranked as an Alpha city, following New York, Toronto, Dubai, Los Angeles, and London [30].

Meanwhile, multiple angles have been employed to analyze Sydney’s economic transformation along with Australia’s integration with the world economy to justify its rise as a global city. Sydney’s economic transformation includes macroeconomic transformation, as well as the transformation of certain industry sectors that are the most impacted by contemporary globalization. These include the industrial shift from manufacturing to a post-industrial information economy [2]; the changed employment structure, global command and control functions, finance sector, and international economic connections [8]; and the emergence of a knowledge-based economy [9]. As Australia’s leading global city, Sydney is dominating Australian urban landscape. This dominance is reflected by its agglomeration of corporate headquarters, particularly in real estate, and insurance and investment services compared to other Australian capital cities [31]; and by being the headquarters of multinationals, producer services, and financial services in national, Asia Pacific, and international contexts [9]. The financial sector and the advanced producer services, the defining functions of global cities, are the most reflective of a global Sydney status. Sydney’s growth to be Australia’s financial and corporate capital has been related to the international financial system, the local political aspiration for a global city, and geographical connections with Asia [1]. As a result, there has been a process of the financialization of economic activities and its spatial manifestations in the Sydney region [5,6,7]. These economic transformations are clear manifestations of Sydney’s rise as a global city.

2.2. Migration

Much literature has been concerned with the spatial settlement of migrants in Sydney in terms of ethnic concentration, segregation, and assimilation. There are two contrasting strands of arguments. One strand of arguments is that Sydney is bifurcating with growing migration: one increasingly dominated by low to medium-income non-English-speaking migrant communities in the west and southwest; and the other comprised of established inner affluent areas and predominantly English-speaking “aspirational” areas on the metropolitan periphery [18]. Skill seems to be an important determining factor of this spatial bifurcation. Skilled migrants and unskilled migrants have different capacities to choose where to live upon arrival in Sydney. Migrants in the former group, who have recently arrived in Sydney, have a greater degree of spatial dispersal than earlier generations and the latter group; migrants in the latter group are much more constrained with regards to where they can afford to live, and have the desire and need to reside among co-ethnics who will support them in adjusting to life in Australia [32]. The constraints of the unskilled migrants help explain why low and moderate-income overseas arrivals continue to settle disproportionately in the western and south-western suburbs in Sydney, which are known as communities with high ethnicity and low socio-economic status [18].

The other strand of arguments is that the ethnic concentration in Sydney does not translate into high levels of ethnic segregation, but into a spatial assimilation that reflects an intermixing of different ethnic groups with each other and with the host society, a view of Australian multiculturalism as “assimilation in slow motion” [17,20]. Empirical studies of Sydney’s western communities indicate some positive aspects of the ethnic concentration, which are seen in the roles of multicultural alliances in spatial convergence, a notion of “togetherness of difference” or “politics of difference” [33,34]. Burnley [14,15] argues that the term segregation is inappropriate for almost all ethnic groups, and the term ghetto, or even enclave, is inappropriate for the ethnic concentrations in Sydney. Although a few suburbs with high ethnic concentrations are experiencing economic difficulties, and have higher proportions of persons with limited English, lower incomes, and no jobs, ethnic concentrations are not the cause of disadvantages [14,15]. On the other hand, as Sydney’s foreign born population has grown, the overall pattern of settlement reflects a greater ethnic mix in both high- and low-socioeconomic areas [32]. The relatively low levels of segregation and high levels of spatial assimilating differentiate Sydney from other global cities; the impacts of globalization and international migration are different everywhere [16].

2.3. Linking Global City and Migration: An Integrative Analytical Framework

As suggested above, the global Sydney thesis and the migration thesis have been developing in parallel. The global Sydney thesis has been economic-centric, focusing on Sydney’s economic transformation, in particular, on its growing global capacity of advanced producer services that are the defining attributes of a global city. The migration thesis has concerned the spatial patterns of the migrant population across the global Sydney region, with a focus on whether the evolving patterns indicate a trend of bifurcating or intermixing. Their interrelationships, however, have not been sufficiently addressed in the scholarship.

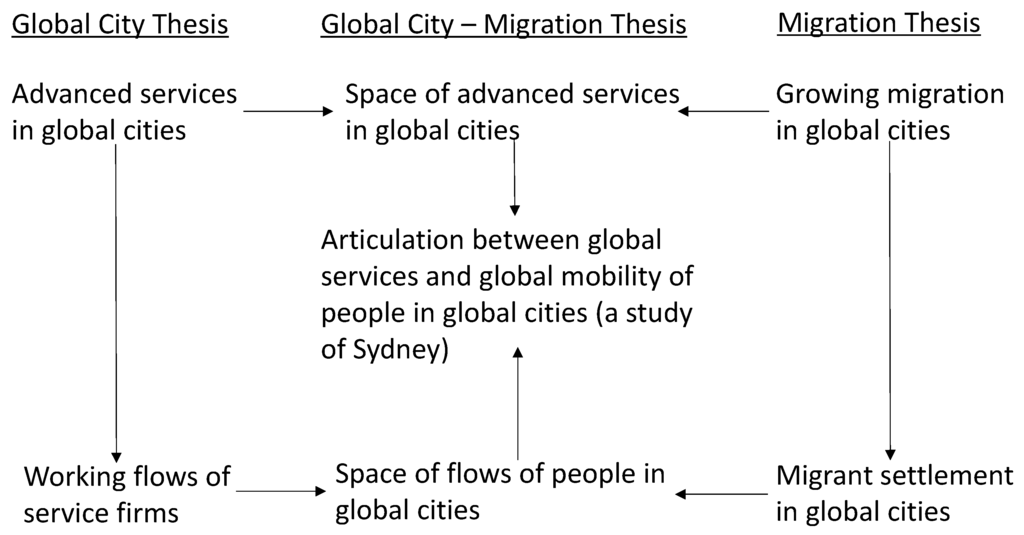

In this study, we construct an integrative analytical framework to link the global Sydney thesis and the migration thesis (see Figure 1). The new framework is underpinned by Sassen’s [10] thesis on global cities as the prime sites for advanced producer services and key nodes in economic globalization, and by Castells’ [35] proposition for global space of flows in a networked society. Sassen [10] distinguishes “the global city” from historically important cities to capture the influence on contemporary globalization on cities, and to emphasize the production of financial and service products in global cities. For Castells [35], “the space of flows” presents a new spatial logic in that places do not disappear but they become defined by their positions within flows as nodes and hubs. Integrating “global city” and “space of flows” aims to enable an articulation of the interrelationships between global Sydney and migration, through the nexus of Sydney’s space of global services and Sydney’s space of flows of people.

The integrative analytical framework aims to advance the scholarships on global city and migration respectively. For the scholarship on global city, seemingly the global city–migration framework is built upon the same underpinning theses of global city and global space of flows as the world city network model [12]. However, they are different in subject and methodology. The world city network concerns an interlocking network of world cities through the “working flows” of the global service firms (electronic and embodied flows of information and knowledge, and face-to-face meetings involving business travel), which are facilitated by the advances in information and communication technologies [12]. The global city–migration framework, however, focuses on the interrelationships between global services and migration within individual global cities, which are the strategic nodes of the global network. The physical flows of migration to and from cities differentiate themselves from the working flows of service firms housed in different cities. For the scholarship of migration, the global city–migration framework moves beyond the traditional approach of migrant settlement to the space of flows of people, to address growing migration. It also moves from a traditional nation-based approach to a city-based approach to analyze contemporary migration. Incorporating the space of flows of people into the global city–migration framework helps capture the new dynamics of people movement in cities as both a contributory and a resultant factor of contemporary globalization.

Figure 1.

Integrative global city–migration analytical framework.

Applying the integrative global city–migration analytical framework to Sydney, this study aims to test two hypotheses concerning the interrelationships between global Sydney and migration:

- Sydney’s capacity of global services is not necessarily linked to its global migration defined by foreign born population in its role as a gateway city for immigrants;

- Sydney’s capacity of global services is linked to its global mobility of people in its role as an urban node in the global city network.

3. Methods

The above two hypotheses are to be tested by three sets of indexes, which are applied to all the local communities across global Sydney. Geographically, global Sydney refers to the Greater Sydney region. Its boundary is defined by the Sydney Statistical Division in the Australian Statistical Geography Classification (ASGC). It contains 64 ASGC’s Statistical Local Areas (SLAs), which are treated as the local communities of global Sydney in this study. Global Sydney has a land area of 12,428 km², and had a resident population of 4,428,976 and an employment population of 1,835,363 in the Australian Census 2011.

The three sets of indexes are global competitiveness index (GCI), global migration index (GMI), and global mobility index (GloMo) respectively:

- GCI measures a community’s capacity of global services in terms of knowledge-intensive industries, highly-skilled occupations, higher levels of qualifications and median income.

- GMI measures a community’s stock and diversity of migrant populations who were born overseas.

- GloMo measures a community’s new people movement from overseas and elsewhere in Australia.

The indicators and weightings of the three sets of indexes are listed in Table 1. The indicators for GCI include high-end industries, occupations, qualifications and income, which combine to reflect a community’s capacity of global services. The construction of GCI has been informed by the global city discourse that highlights a city’s capacity of advanced producer services in the integrated world economy [10,12] and the urban competitiveness measures of a city’s economic performances [36,37]. GMI considers not only foreign-born population as a whole, but also people from non-English-speaking countries and dominant ethnic group, to reflect both stock and diversity of migrants. The construction of GMI has been informed by the Urban Immigrant Index that ranks global immigrant cities [30]. The GloMo is designed specifically for this study to differentiate from previous studies. Unlike GMI that is based on people’s country of birth, GloMo emphasizes people movement from overseas and elsewhere in Australia. Furthermore, GloMo incorporates factors of non-Australian-citizens and movers from outside Sydney to capture the complexity of people movement.

Table 1.

Indicators and weightings of global competitiveness index (GCI), global migration index (GMI), and global mobility index (GloMo).

| Indexes | Indicators | Weightings |

|---|---|---|

| GCI | Percentage of employed persons in the knowledge-intensive industries | 20% |

| Total number of employed persons in the knowledge-intensive industries | 10% | |

| Percentage of employed persons in the highly-skilled occupations | 20% | |

| Total number of employed persons in the highly-skilled occupations | 10% | |

| Percentage of employed persons with higher levels of education | 20% | |

| Median weekly individual income | 20% | |

| GMI | Percentage of foreign-born population | 40% |

| Total number of foreign-born population | 30% | |

| Percentage of foreign-born population not from English-speaking countries | 15% | |

| No one ethnic group is more than 25% of the foreign-born population | No, 15%; Yes, −15% | |

| GloMo | Percentage of international movers | 40% |

| Total number of international movers | 30% | |

| Percentage of non-Australian-citizen movers in total moving population | 20% | |

| Percentage of movers from outside Greater Sydney region in total internal movement population | 10% |

For the three sets of indexes, both percentages and total numbers of major indicators are included to achieve a holistic understanding and to avoid skewing results. The weightings reflect the indicators’ importance in the index. For GCI, industries and occupations have higher weightings than qualification and income. For GMI, foreign-born-born population has much higher weightings than people from non-English-speaking countries and dominant ethnic group. For GloMo, international movers enjoy a dominant weighting to highlight global movement. For indicators that have both percentages and total numbers, percentages have higher weightings than total numbers. Likewise, these approaches have been informed by the measures of advanced producer services in global cities [10,12], and compositions and weightings of the Urban Immigrant Index [30]. The data are collected from the Australian Census 2011. The data for GMI and GloMo are based on Place of Usual Residence; the data for GCI are based on Place of Work. The indicators are defined as follows to facilitate data collection:

- The knowledge-intensive industries include the following industry divisions in the Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC) 2006: Information Media and Telecommunications; Financial and Insurance Services; Rental, Hiring and Real Estate Services; and Professional, Scientific and Technical Services.

- The highly-skilled occupations include the following occupation groups in the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) 2006: Managers, and Professionals.

- The higher levels of education include the following levels of qualifications the Australian Standard Classification of Education (ASCED) 2001: Postgraduate Degree, Graduate Diploma and Graduate Certificate, and Bachelor’s Degree.

- The foreign born population is determined by the country of birth.

- The English-speaking countries include Australia, the UK and Ireland, New Zealand, the USA and Canada.

- The recent people movement is based on the Five Years Usual Residence Indicator in the Australian Census 2011, which indicates people who moved their residences in the period 2006–2011.

z-Scores for the indicators are calculated to standardize the values. The final value for each index is the sum of the indicators’ z-scores weighted. Higher values reflect higher performances in the composite index. The standardization and summing of indexes have also been informed by the Urban Immigrant Index [30]. The 64 SLAs are mapped, using legends of quartiles of the index values. Spatial patterns are described and statistical relationships are measured for the indexes, to test the hypotheses concerning the interrelationships between global Sydney and migration.

4. Results

4.1. Spatial Relationship

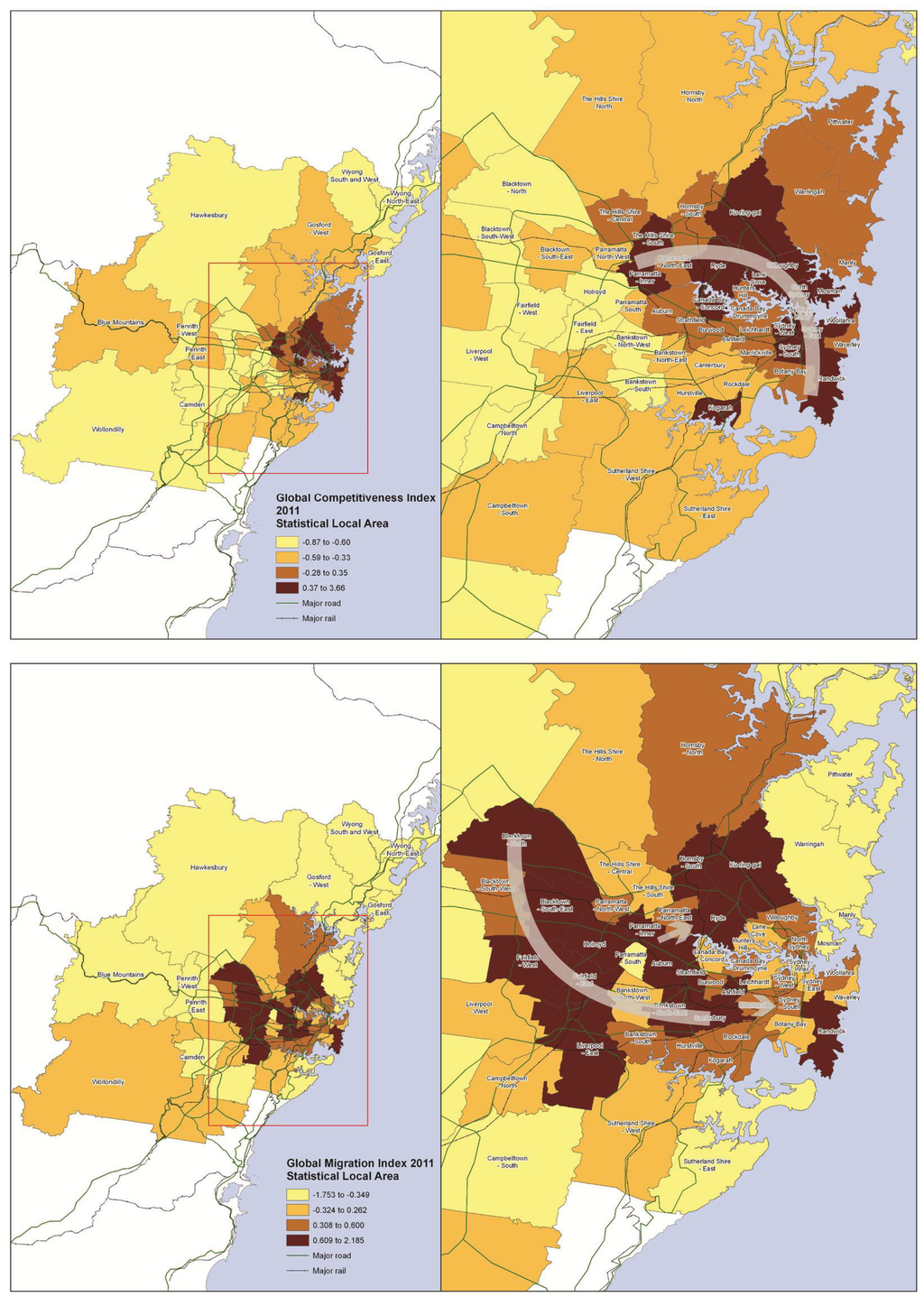

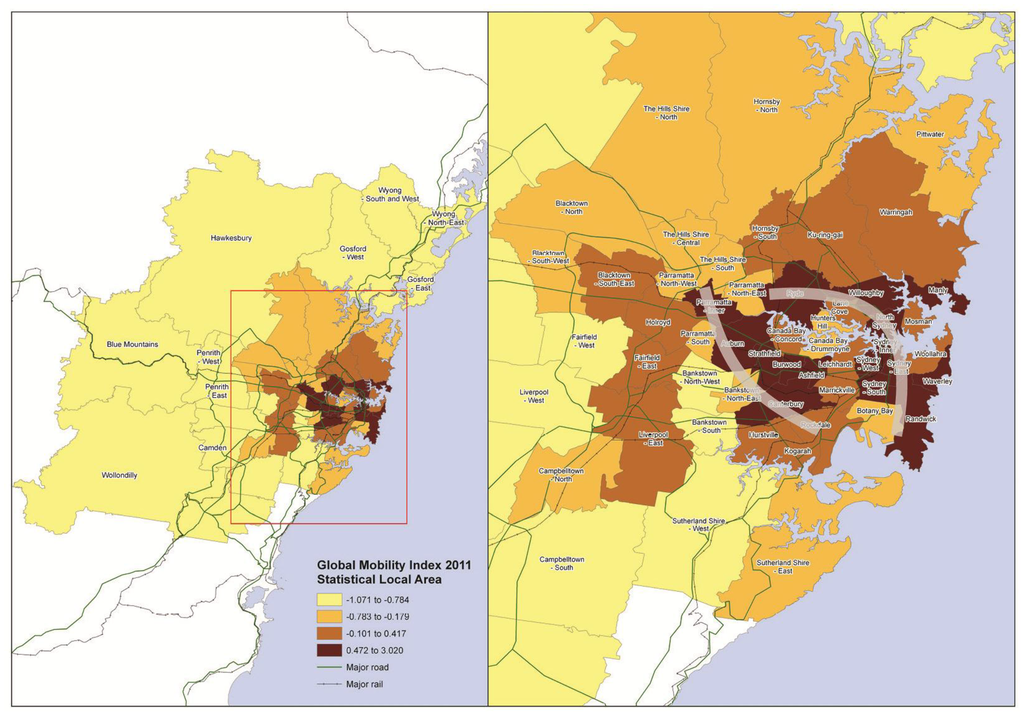

Figure 2 presents the spatial coverage of GCI, GMI, and GloMo across global Sydney. The values of the indexes for each SLA are provided in Appendix Table A1. The three indexes demonstrate diverging and converging spatial patterns. The GCI and GMI, on the one hand, ascertain some previous perceptions of the geographical locations of Sydney’s global capacities and migrant communities with substantive evidence. On the other hand, they reveal the newest geographical developments of Sydney’s global capacities and migrant communities that were not known before. The GloMo combines newcomers from overseas and elsewhere in Australia into Sydney, whose spatial coverage has not ever been comprehensively examined.

Figure 2.

GCI, GMI and GloMo in global Sydney.

Communities with high GCIs form a “global arc”, which runs through central Sydney and links northwest and southeast communities at both ends. The “global arc” was first suggested in Sydney’s metropolitan strategy City of Cities [38] referring to the economic corridor of jobs and major infrastructure stretching from Macquarie Park to Port Botany through Chatswood, St Leonards, North Sydney, Sydney CBD, and Sydney Airport. Compared to the “global arc” identified in City of Cities in 2005, the “global arc” based on the GCI extends at both ends to include Parramatta in the southwest and Randwick in the southeast. Communities with the highest GCIs remain in Sydney CBD and North Sydney, with declining GCIs for communities along both directions of the “global arc”. The GCI results substantiate the traditional “global arc” in Sydney, and reveal its newest geographical developments of emerging global communities.

Communities with the highest GMIs remain in the west and southwest areas, which have been traditionally known for high ethnic concentration in Sydney. However, the GMI indicates that communities with high foreign-born populations are expanding northward and eastward. For example, Ryde and Ku-ring-gai in the north, and Randwick in the east, have considerably high GMIs. More communities in the north and in the east areas of Sydney fall into the second quartile of GMI. Sydney’s growing migration is reflected by high GMIs not only in communities that were traditionally known for high ethnic concentration, but also in communities which that traditionally known for low ethnic concentration.

The GloMo coverage seems to combine the spatial patterns of GCI and GMI. Communities with the highest GloMos form two arcs, facing each other. The east arc almost coincides with the “global arc” of communities with high GCIs in the east area; the west arc almost coincides with communities with high GMIs in the west area. The communities around the two arcs mostly fall into the second quartile of GloMo 2011. The top communities of GloMo are the two CBDs in global Sydney: inner Sydney and inner Parramatta. Two eastern communities Manly and Waverley also indicate considerably high GloMos.

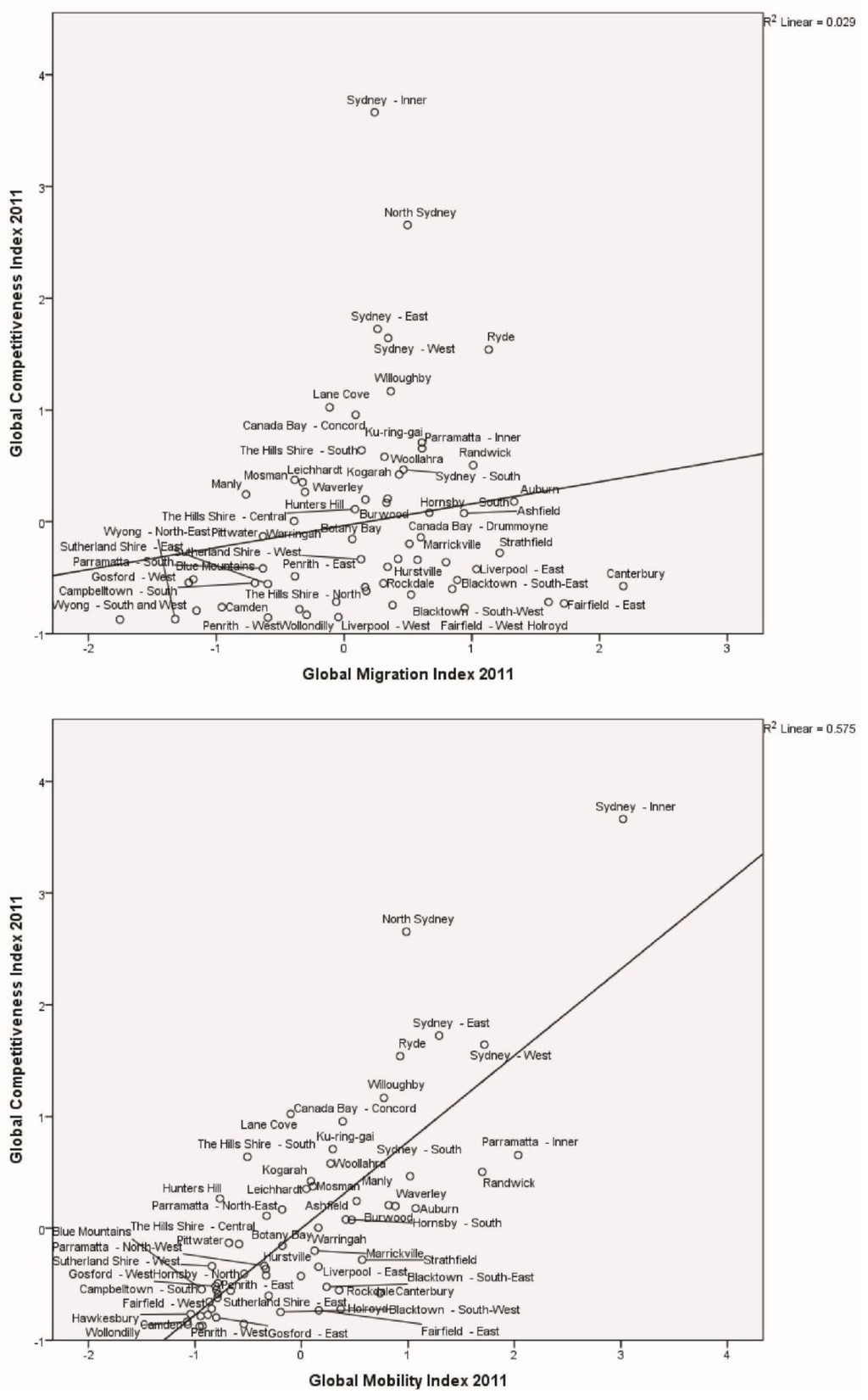

4.2. Statistical Relationship

To test the roles of migration and people movement in explaining global services, two regression models are run to measure the relationships between GCI with GMI, and between GCI and GloMo respectively. The regression results are show in Table 2. Their respective relationships are illustrated in Figure 3. The results show that GCI is poorly influenced by GMI (R² = 0.029), but is strongly linked to GloMo (R² = 0.575). GMI is not a significant predictor of GCI (Beta = 0.171, p < 0.176), while GloMo is a significant predictor of GCI (Beta = 0.758, p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Regression results (n = 64).

| Dependent variable: GCI | R² | Adjusted R² | Beta coefficients | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable: GMI | 0.029 | 0.014 | 0.171 | 0.176 |

| Independent variable: GloMo | 0.575 | 0.568 | 0.758 | 0.0001 |

Figure 3.

Relationship between GCI and GMI, and between GCI and GloMo in global Sydney (n = 64).

5. Concluding Discussion

The findings reveal both spatial patterns and statistical relationships between GMI, and GCI and GloMo respectively in global Sydney. They ascertain the two hypotheses concerning the interrelationships between global Sydney and migration proposed earlier. As a global city, Sydney’s capacity for global services is more related to its global mobility of people movement than its global migration of foreign born population. Sydney’s rise as a global city has been accompanied by multiple and profound changes in its migration patterns. One prominent change is the growing scale and diversity of the foreign born population [32,39]. However, this study finds that classifying global migration by foreign born population is insufficient in capturing its associations with global Sydney. The global mobility of people movement better addresses the complexities of contemporary migration in global cities.

Both differentiation and embedment exist between global mobility and global migration. Global mobility includes people movement from Australia (internal migration) and from overseas (international migration). Internal migration and international migration are determined by the direction of movement, not by the country of birth; both internal migration and international migration include people born in Australia and overseas [40]. In 2006–2011, returning Australians (Australia-born people) accounted for 10% of international migration, after China and India only as the third largest group by country of birth. For the knowledge intensive industries that are most related to Sydney’s global city status, returning Australians accounted for an even higher share of 18% in international migration. Excluding them in the conventional analysis of migration by country of birth will miss a significant cohort of people movement. This study raises the question of redefining migration according to global mobility of people movement, which is more relevant to Sydney as a global city.

The integrative global city–migration analytical framework proves to be valid in addressing the interrelationships between global city and migration, through a case study of Sydney. One critique to the global city discourse is that a focus on business and technological dimensions of global cities is accompanied by the lack of a focus on the relationship between migration and global cities [30,41]. In effect, migration constituted an important component in the earliest global city hypothesis. In Friedmann’s [22] world city hypothesis, world cities are points of destination for large number of both domestic and/or international migrants as well. Sassen’s [10] global city–migration thesis argues that global cities are the main destinations for immigrants with divided social polarizations between skilled migrants and unskilled migrants. The subsequent global city discourse has paid more attention to the economic dimension of globalization and cities, focusing on the world city network through the working flows of global service firms [12]. The integrative global city–migration analytical framework proposed in this study is not a return back to the earliest thesis of global cities as destinations of immigration and polarization [10,21]. Rather, it integrates a global city’s economic competitiveness with migration through the nexus of people movement to articulate their interrelationships.

This study attests that global city is a meaningful spatial scale for analyzing migration in contemporary globalization. Australian international migration has undergone significant transformations in the last few decades of globalization in terms of nature, composition, and effects [32,42,43]. These transformations constitute a paradigmatic shift in Australian international migration; one dimension of the shift is the increasing role played by the Australian cities most linked into the global economic system, especially Sydney [43]. The importance of city-based analysis of contemporary globalization has been acknowledged in the global city discourse. A single world economic system is overtaking the traditional economic roles and powers of nation states; cities or city-regions are emerging as dominant spatial scales as central nodes in the world economy [10,22,24,44,45]. Global city regions are now “active agents in shaping globalization itself” as “motors” or new “spatial nodes” of the global economy [45]. However, a similar understanding has not been shared for cities and migration. A barrier to this search for understanding is a failure to recognize that the world city is an important and appropriate unit for analyzing the effects of both immigration and internal migration [32]. This study illustrates that global city is an important spatial scale for migration analysis, incorporating both international and internal people movement, in addition to the conventional nation-based approach to immigration.

The findings need to be considered in relation to Australia’s migration history and policy. Unlike European and Asian countries, Australia, along with the United States, Canada and New Zealand, is a “land of recent settlement”. It is also seen as a “traditional migration country” since it is one of the few nations that have a formal immigration program. Its immigration policy has played a determining role in its migration composition and patterns in history. Compared to other “traditional” migration countries, Australian migration has a number of distinctive elements, one of which is the highly planned and closely managed nature of its immigration system [46]. In the last few decades of globalization, Australian migration has undergone significant transformations in terms of nature, composition, and effects [32,42,43]. They constituted a paradigm shift in Australian migration, one dimension of which is the increasing role played by the Australian cities most linked into the global economic system, especially Sydney [43].

The effects of two important immigration policy changes since the mid-1990s are observed by this study: one is the introduction of temporary migration; the other is an increasing focus on skilled migrants. They marked a significant shift from the post-War immigration policy that had focused almost exclusively on recruiting permanent worker settlers to meet the labor needs of a rapidly growing economy, especially in manufacturing [46]. Since the mid-1990s, Sydney and Australia’s integration with the global economy has been developing with an accelerated rate. This globalization process has been concurrent with the migration policy effect of a growing number of new migrants who are characterized by flexible movement and high skills and a declining number of old migrants who are characterized by permanent settlement and low skills. The former is more captured by GMI while the latter is more captured by GloMo. The Australian migration history and policy changes contextualize a distinctive understanding of the differentiation of global migration and global mobility and their associations with global competitiveness, which are identified in this study.

To sum up, this study addresses a scholarly deficiency, and proposes an integrative analytical framework to link global city and migration. A case study of global Sydney provides new insights into the spatial patterns and statistical relationships of the city’s global competitiveness, global migration, and global mobility. Furthermore, it sheds light on the nexus through which the interrelationships between global city and migration are articulated. As a global city, Sydney’s capacity of global services is more related to its global mobility of people movement than its global migration of foreign born population. These findings suggest a need to redefine migration, moving from the conventional definition by country of birth to incorporate people movement, to address the relationship between global city and migration in contemporary globalization.

Acknowledgments

This study received financial support from the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection. The author wishes to thank the following people for their contribution: Richard Manderson and William McClure provided useful comments on the study; Dan Payne and Yang Liu helped produce the map and visuals; and Shaun Allen and Lucas Carmody provided research assistance.

Appendix

Table A1.

GCI, GMI and GloMo for SLAs in global Sydney.

| SLAs | GCI | GMI | GloMO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ashfield | 0.075 | 0.939 | 0.472 |

| Auburn | 0.179 | 1.33 | 1.072 |

| Bankstown-North-East | −0.362 | 0.798 | −0.335 |

| Bankstown-North-West | −0.621 | 0.174 | −0.788 |

| Bankstown-South | −0.653 | 0.524 | −0.863 |

| Blacktown-North | −0.602 | 0.846 | −0.307 |

| Blacktown-South-East | −0.522 | 0.886 | 0.236 |

| Blacktown-South-West | −0.747 | 0.38 | −0.196 |

| Blue Mountains | −0.544 | −1.214 | −0.937 |

| Botany Bay | −0.155 | 0.065 | −0.179 |

| Burwood | 0.207 | 0.341 | 0.819 |

| Camden | −0.858 | −0.595 | −1.066 |

| Campbelltown-North | −0.854 | −0.044 | −0.54 |

| Campbelltown-South | −0.549 | −0.697 | −0.798 |

| Canada Bay-Concord | 0.956 | 0.091 | 0.388 |

| Canada Bay-Drummoyne | −0.139 | 0.6 | −0.586 |

| Canterbury | −0.577 | 2.185 | 0.739 |

| Fairfield-East | −0.732 | 1.722 | 0.163 |

| Fairfield-West | −0.772 | 0.944 | −0.879 |

| Gosford-East | −0.796 | −1.154 | −0.8 |

| Gosford-West | −0.516 | −1.179 | −0.805 |

| Hawkesbury | −0.765 | −0.956 | −1.039 |

| Holroyd | −0.719 | 1.6 | 0.37 |

| Hornsby-North | −0.404 | 0.341 | −0.537 |

| Hornsby-South | 0.079 | 0.668 | 0.417 |

| Hunters Hill | 0.265 | −0.306 | −0.765 |

| Hurstville | −0.342 | 0.575 | 0.16 |

| Kogarah | 0.422 | 0.432 | 0.089 |

| Ku-ring-gai | 0.709 | 0.609 | 0.295 |

| Lane Cove | 1.024 | −0.113 | −0.101 |

| Leichhardt | 0.352 | −0.324 | 0.046 |

| Liverpool-East | −0.425 | 1.036 | −0.005 |

| Liverpool-West | −0.717 | −0.061 | −0.843 |

| Manly | 0.244 | −0.767 | 0.518 |

| Marrickville | −0.198 | 0.511 | 0.124 |

| Mosman | 0.374 | −0.386 | 0.108 |

| North Sydney | 2.655 | 0.497 | 0.985 |

| Parramatta-Inner | 0.655 | 0.61 | 2.035 |

| Parramatta-North-East | 0.169 | 0.332 | −0.181 |

| Parramatta-North-West | −0.334 | 0.423 | −0.349 |

| Parramatta-South | −0.418 | −0.634 | −0.332 |

| Penrith-East | −0.489 | −0.384 | −0.784 |

| Penrith-West | −0.783 | −0.349 | −0.947 |

| Pittwater | −0.13 | −0.634 | −0.681 |

| Randwick | 0.505 | 1.011 | 1.698 |

| Rockdale | −0.552 | 0.308 | 0.354 |

| Ryde | 1.54 | 1.132 | 0.927 |

| Strathfield | −0.279 | 1.218 | 0.571 |

| Sutherland Shire-East | −0.557 | −0.596 | −0.664 |

| Sutherland Shire-West | −0.337 | 0.133 | −0.84 |

| Sydney-East | 1.725 | 0.262 | 1.293 |

| Sydney-Inner | 3.664 | 0.239 | 3.02 |

| Sydney-South | 0.466 | 0.465 | 1.02 |

| Sydney-West | 1.643 | 0.345 | 1.718 |

| The Hills Shire-Central | 0.112 | 0.086 | −0.327 |

| The Hills Shire-North | −0.586 | 0.165 | −0.783 |

| The Hills Shire-South | 0.639 | 0.137 | −0.507 |

| Warringah | 0.005 | −0.391 | 0.159 |

| Waverley | 0.198 | 0.167 | 0.882 |

| Willoughby | 1.168 | 0.366 | 0.774 |

| Wollondilly | −0.833 | −0.292 | −1.071 |

| Woollahra | 0.58 | 0.316 | 0.274 |

| Wyong-North-East | −0.871 | −1.321 | −0.93 |

| Wyong-South and West | −0.875 | −1.753 | −0.956 |

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- M. Daly, and B. Pritchard. “Sydney: Australia’s financial and corporate capital.” In Sydney: The Emergence of a World City. Edited by J. Connell. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 167–188. [Google Scholar]

- R. Fagan. “Industrial change in the global city: Sydney’s new spaces of production.” In Sydney: The Emergence of a World City. Edited by J. Connell. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 144–166. [Google Scholar]

- R. Hu. “Clustering: Concentration of the knowledge-based economy in Sydney.” In Building Prosperous Knowledge Cities: Policies, Plans and Metrics. Edited by T. Yigitcanlar, K. Metaxiotis and J. Carrillo. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2012, pp. 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- R. Hu. “Remaking of central Sydney: Evidence from floor space and employment surveys in 1991–2006.” Int. Plan. Stud. 19 (2014): 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. O’Neill, and P. McGuirk. “Prosperity along Australia’s eastern seaboard: Sydney and the geopolitics of urban and economic change.” Aust. Geogr. 33 (2002): 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. O’Neill, and P. McGuirk. “Reconfiguring the CBD: Work and discourses of design in Sydney’s office space.” Urban Stud. 40 (2003): 1751–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. O’Neill, and P. McGuirk. “Reterritorialisation of economies and institutions: The rise of the Sydney basin economy.” Space Polity 9 (2005): 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Searle. Sydney as a Global City. Sydney, Australia: Department of Urban Affairs and Planning, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- R. Stein. Sydney Globalizing: A World City in National, Pacific Asian and International Context. Berlin, German: Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, Bauhaus Kolleg, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- S. Sassen. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo, 2nd ed. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- S. Sassen. “Urban impacts of economic globalism.” In Cities in Competition: Productive and Sustainable Cities for the 21st Century. Edited by J.F. Brotchie, M. Batty, E. Blakely, P. Hall and P.W. Newton. Melbourne, Australia: Longman Australia, 1995, pp. 36–57. [Google Scholar]

- P.J. Taylor. World City Network: A Global Urban Analysis. New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- P.J. Taylor. “Advanced producer service centres in the world economy.” In Global Urban Analysis: A Survey of Cities in Globalization. Edited by P.J. Taylor, P. Ni, B. Derudder, M. Hoyler, J. Huang and F. Witlox. London, UK: Earthscan, 2011, pp. 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- I. Burnley. “Immigrant city, global city? Advantage and disadvantage among communities from Asia in Sydney.” Aust. Geogr. 29 (1998): 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. Burnley. “Levels of immigrant residential concentration in Sydney and their relationship with disadvantage.” Urban Stud. 36 (1999): 1295–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Forrest, M. Poulsen, and R. Johnston. “Everywhere different? Globalisation and the impact of international migration on Sydney and Melbourne.” Geoforum 34 (2003): 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Forrest, M. Poulsen, and R. Johnston. “A “multicultural model” of the spatial assimilation of ethnic minority groups in Australia’s major immigrant-receiving cities.” Urban Geogr. 27 (2006): 441–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Healy, and B. Birrell. “Metropolis divided: The political dynamic of spatial inequality and migrant settlement in Sydney.” People Place 11 (2003): 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- D. Ley, and P. Murphy. “Immigration in gateway cities: Sydney and Vancouver in comparative perspective.” Prog. Plan. 55 (2001): 119–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Poulsen, R. Johnston, and J. Forrest. “Is Sydney a divided city ethnically? ” Austr. Geogr. Stud. 42 (2004): 356–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Baum. “Sydney, Australia: A global city? Testing the social polarisation thesis.” Urban Stud. 34 (1997): 1881–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Friedmann. “The world city hypothesis.” Dev. Change 17 (1986): 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Friedmann. “Where we stand: a decade of world city research.” In World Cities in a World System. Edited by P.L. Knox and P.J. Taylor. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- S. Sassen. Cities in a World Economy. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Pine Forge, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- J.V. Beaverstock, P.J. Taylor, and R.G. Smith. “A roster of world cities.” Cities 16 (1999): 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B.J. Godfrey, and Y. Zhou. “Ranking world cities: Multinational corporations and the global urban hierarchy.” Urban Geogr. 20 (1999): 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P.J. Taylor, P. Ni, and B. Derudder. “Introduction: The GUCP/GaWC project.” In Global Urban Analysis: A Survey of Cities in Globalization. Edited by P.J. Taylor, P. Ni, B. Derudder, M. Hoyler, J. Huang and F. Witlox. Londo, UK: Earthscan, 2011, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- R. Hu, E.J. Blakely, and Y. Zhou. “Benchmarking the competitiveness of Australian global cities: Sydney and Melbourne in the global context.” Urban Policy Res. 31 (2013): 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GaWC. “The World According to GaWC.” Available online: http://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/gawcworlds.html (accessed on 4 February 2015).

- L. Benton-Short, M.D. Price, and S. Friedman. “Globalization from below: the ranking of global immigrant cities.” Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 29 (2005): 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Tonts, and M. Taylor. “Corporate location, concentration and performance: Large company headquarters in the Australian urban system.” Urban Stud. 47 (2010): 2641–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Hugo. “Sydney: The globalization of an established immigrant gateway.” In Migrants to the Metropolis: The Rise of Immigrant Gateway Cities. Edited by M. Price and L. Benton-Short. New York, NY, USA: Syracuse University Press, 2008, pp. 68–96. [Google Scholar]

- K.M. Dunn. “Rethinking ethnic concentration: The case of Cabramatta, Sydney.” Urban Stud. 35 (1998): 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Gow. “Rubbing shoulders in the global city: Refugees, citizenship and multicultural alliances in Fairfield, Sydney.” Ethnicities 5 (2005): 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Castells. The Rise of the Network Society. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- P.K. Kresl, and B. Singh. “Competitiveness and the urban economy: Twenty-four large US metropolitan areas.” Urban Stud. 36 (1999): 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P.K. Kresl, and B. Singh. “Urban competitiveness and US metropolitan centres.” Urban Stud. 49 (2012): 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New South Wales Department of Planning. City of Cities: A Plan for Sydney’s Future. Sydney, Australia: Department of Planning, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- I. Burnley. “Diversity and difference: Immigration and the multicultural city.” In Sydney: The Emergence of a World City. Edited by J. Connell. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 244–272. [Google Scholar]

- R. Hu. “Migrant knowledge workers: An empirical study of global Sydney as a knowledge city.” Expert Syst. Appl. 41 (2014): 5605–5613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Samers. “Immigration and the global city hypothesis: Towards an alternative research agenda.” Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 26 (2002): 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Collins. “The changing political economy of Australian immigration.” Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 97 (2006): 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Hugo. “Globalization and changes in Australian international migration.” J. Popul. Res. 23 (2006): 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Friedmann, and G. Wolff. “World city formation: An agenda for research and action.” Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 6 (1982): 309–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.J. Scott. Global City-Regions: Trends, Theory, Policy. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- G. Hugo. “Change and continuity in Australian international migration policy.” Int. Migr. Rev. 48 (2014): 868–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).