Abstract

This study examines the feminization of poverty in Indonesia, focusing on the distinct vulnerabilities faced by female-headed households. Utilizing data from the 2023 National Socio-Economic Survey (SUSENAS) involving 291,231 households, this study applies a logistic regression model to investigate gender-specific determinants of household poverty. This research finds that education, digital literacy, financial inclusion, and the employment sector are significant factors influencing poverty status, with female-headed households facing disproportionately higher risks. These gaps are mainly attributed to systemic barriers in financial access, digital literacy gaps, and limited labor market opportunities for women. This study emphasizes the importance of implementing gender-responsive policy measures, including targeted education, enhanced digital literacy training, and inclusive financial programs. By presenting empirical evidence from Indonesia, this study contributes to the discourse on gender and poverty, offering actionable insights for the development of inclusive poverty alleviation strategies.

1. Introduction

Poverty remains a multidimensional challenge in Indonesia, with the poverty rate of women (9.49%) slightly higher than that of men (9.23%) in 2023 (Badan Pusat Statistik, 2023a). Although previous studies identified determinants such as education, financial access, and gender inequality (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2020; Klasen, 2018), studies in Indonesia remain limited in terms of integrating contemporary variables, including digital literacy and an intersectional analysis of female-headed households. Most studies have employed income-based approaches (Ravallion, 2020), whereas multidimensional aspects such as access to digital services and intra-household dynamics remain understudied. This study tries to address these gaps by considering gender poverty and female-headed households. This research will be more comprehensive than previous studies as it will integrate modern determinants such as information technology (IT) skills and financial inclusion, such as bank account ownership, using national data SUSENAS, 2023. Consequently, the novelty of this research lies in analyzing the impact of female-headed households, as well as the inclusion of formal technology and financial access variables, which are rarely investigated in the Indonesian context, marking this work as distinct from the research by Mabrouk (2023) and Zenebe (2020).

Female poverty includes absolute, relative, and multidimensional aspects. Absolute poverty refers to a lack of necessities, whereas relative poverty emphasizes inequality in access to economic opportunities compared to others in society (Allen, 2017; Ravallion, 2020). Multidimensional poverty encompasses education, health, and living standards, emphasizing the complex realities faced by women in Indonesia. However, in many cases, poverty is measured by a single dimension, such as by expenditure (Rao, 2006) or food consumption (Pape & Mistiaen, 2018). In this research, we will use expenditure per capita as an indication of poverty status. Furthermore, other research (Araki & Olivos, 2024; Egyir et al., 2023) has found that gender inequality, as reflected by gaps in education, financial access, and labor market participation, has a significant impact on female poverty. These dynamics reveal that women disproportionately bear the burden of poverty owing to systemic inequality, limited access to resources, and sociocultural barriers to economic empowerment. Consequently, women are more likely to experience poverty than men (Atozou et al., 2017; Bradshaw et al., 2017). Although extant studies on women and poverty have evolved over recent decades, particularly in developing countries, they often overlook factors such as marital status, digital and financial access, and educational opportunities (Edwar & Blanca, 2022; Mabrouk, 2023).

Female-headed households are often more vulnerable to poverty. This is caused by a various socio-economic factors, including limited access to education and employment opportunities, lack of social protection, and limited control over household resources (Bikorimana & Sun, 2020; Biswal et al., 2020; Duc, 2022; Sharma, 2023). However, several previous studies, such as the work by Rahman et al. (2021), found no significant gender-based differences owing to targeted social assistance programs. These contradicting findings drive the need for further research to generate more precise strategies to reduce poverty in female-headed households. In addition, previous studies confirmed that educational attainment and financial inclusion reduce poverty, particularly for women. According to Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (2020), women with better access to formal financial services are more likely to escape poverty than those who rely on informal resources. Additionally, García-Vélez and Nuñez Velázquez (2021) and Wei et al. (2021) also emphasized the long-term benefits of education in reducing poverty among women in rural settings, where access to economic resources remains limited. Lebni et al. (2020) and M. Zhang et al. (2024) found that female-headed households are more likely to experience poverty and have limited access to financial services, which can exacerbate their poverty.

The above discussion indicates that financial inclusion, a household being headed by a female, demographic characteristics, and poverty are closely related. Financial inclusion can reduce poverty, particularly among women, by increasing access to financial services and promoting economic empowerment. Several studies have examined and supported this argument, including those from Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (2020) and Cozarenco and Szafarz (2023). These studies concluded that financial inclusion is an essential factor in reducing poverty and promoting economic growth. However, women often face barriers concerning access to financial services, which can hinder their economic progress and increase their risk of poverty. In fact, access to financial services, including savings, credit, and insurance, can assist households in managing risk, investing in human capital, and enhancing their overall well-being (Yap et al., 2023). Despite the potential benefits of financial inclusion, several households in Indonesia remain excluded from formal financial services, this is particularly true for female-headed households (Putri & Hartono, 2024). Therefore, this study focused on the gender dimension of poverty in Indonesia, particularly in the context of female-headed households.

The relationship between financial inclusion and poverty alleviation is complex. For example, Omenihu et al. (2024) explained that the relationship between financial inclusion and poverty alleviation is complex and influenced by various factors, including the types of available financial services, financial literacy levels, and the regulatory environment. Previous studies also demonstrated that financial inclusion can positively impact poverty reduction, particularly in vulnerable populations such as women and rural households (Kumar & Jie, 2023). However, research on the effect of financial inclusion on female-headed households in Indonesia is limited, particularly regarding poverty.

Therefore, this study aims to fill this research gap by providing a gender-disaggregated analysis of the economic and social factors influencing poverty, particularly among female-headed households, utilizing contemporary variables such as digital access and financial inclusion. This study will examine the impact of financial inclusion on poverty reduction in female-headed households and identify key factors influencing this relationship. The findings of this study contribute to the literature on financial inclusion and poverty alleviation, particularly in the context of female-headed households in Indonesia. By examining the relationship between financial inclusion and poverty, this study provides new insights into the complex relationship between poverty, financial inclusion, and gender. The findings of this study can inform policy interventions aimed at reducing poverty and promoting financial inclusion in Indonesia, with a focus on addressing the specific needs of female-headed households.

2. Methodology

The data used in this study were obtained from the Indonesian 2023 National Socioeconomic Survey (SUSENAS), which comprised 341,802 households and 1,048,575 individuals. The final sample was obtained using multistage stratified sampling approach and comprised 291,231 households and 669,297 individuals. Stratification ensures representation across a wide range of demographics.

A binary logistic regression model was employed to estimate the probability of a household being categorized as poor (dependent variable coded as 1 = poor and 0 = non-poor). One of the main reasons for using a logistic regression model over multiple linear regression is the categorical nature of the dependent variable. In this study, poverty, as measured by poverty status, is treated as categorical data and, according to Achia et al. (2010), the use of a linear regression model is not suitable for categorical data. In other words, a logistic regression model is used to predict the probability of an event based on one or more independent variables. Unlike linear regression, which produces output in the form of continuous values, a logistic regression model is used when the dependent variable is dichotomous (two categories). This model was selected for its suitability in analyzing dichotomous outcome variables and its capacity to interpret marginal effects (Cox, 2018; Harrell, 2015; Tranmer & Elliot, 2008). Furthermore, the use of a logistic model is also based on the flexibility of this model, as it does not assume the data must be normally distributed (McCullagh, 2019) and is resistant to heteroscedasticity (Rodriguez & Smith, 1994). Various studies ((Filmer & Pritchett, 2001; Isah Abubakar & Lawal, 2024; Joshi et al., 2012; Nurdiansyah & Khikmah, 2020) have shown that logistic regression can be used effectively with survey data to identify the determinants of poverty across countries.

In this study, thirteen variables were used to estimate the probability of a household being categorized as poor (Table 1). The dependent variable was poverty status, based on the national poverty line of IDR 535,547 per capita per month (Badan Pusat Statistik, 2023b). The independent variables included education (Edu), age (Age), female-headed household (Fem_Head), working status (Work), domicile (urban or rural) (Loc), IT skills (IT_Skill), Family size (Hhsize), employment sector (Form_SEC), bank account ownership (BA), and access to credit (CA). These independent variables was selected based on previous studies, including Obayelu Abiodun and Ogunlade (2006), Moorosi (2009), Sharma (2023), Tran and Le (2021), and Emara and Mohieldin (2020).

Table 1.

Descriptions of variables and hypothesis.

The binary logistic model applied in this research is estimated using the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) approach. The MLE approach works by maximizing the likelihood function, which is the chance (probability) that the observed data are generated by a model with certain parameters (Cox, 2018; Tukur & Usman, 2016). Additionally, the marginal effects were computed to interpret the magnitude of each variable’s impact on poverty probability. Hosmer and Lemeshow (2000) noted that a marginal effect in a model shows how much of a change in probability (output) results from a small change (usually one unit) in the independent variable, assuming the other variables are constant. Given that logistic model is non-linear, the logistic regression coefficient (β) cannot be directly interpreted as a change in probability as in linear regression. Therefore, the marginal effect is used to interpret the real impact of the independent variable on probability. In addition, all models report robust standard error, and significance levels are denoted at 1% (***), 5% (**), and 10% (*). Diagnostic tests, such as multicollinearity, heteroscedasticity, conformity, and model specification (Linktest), are used to ensure robustness and marginal effects to facilitate interpretation.

The logit model in this study is

3. Results

3.1. Poverty Distribution and Socio-Demographic Structure and Digital Literacy

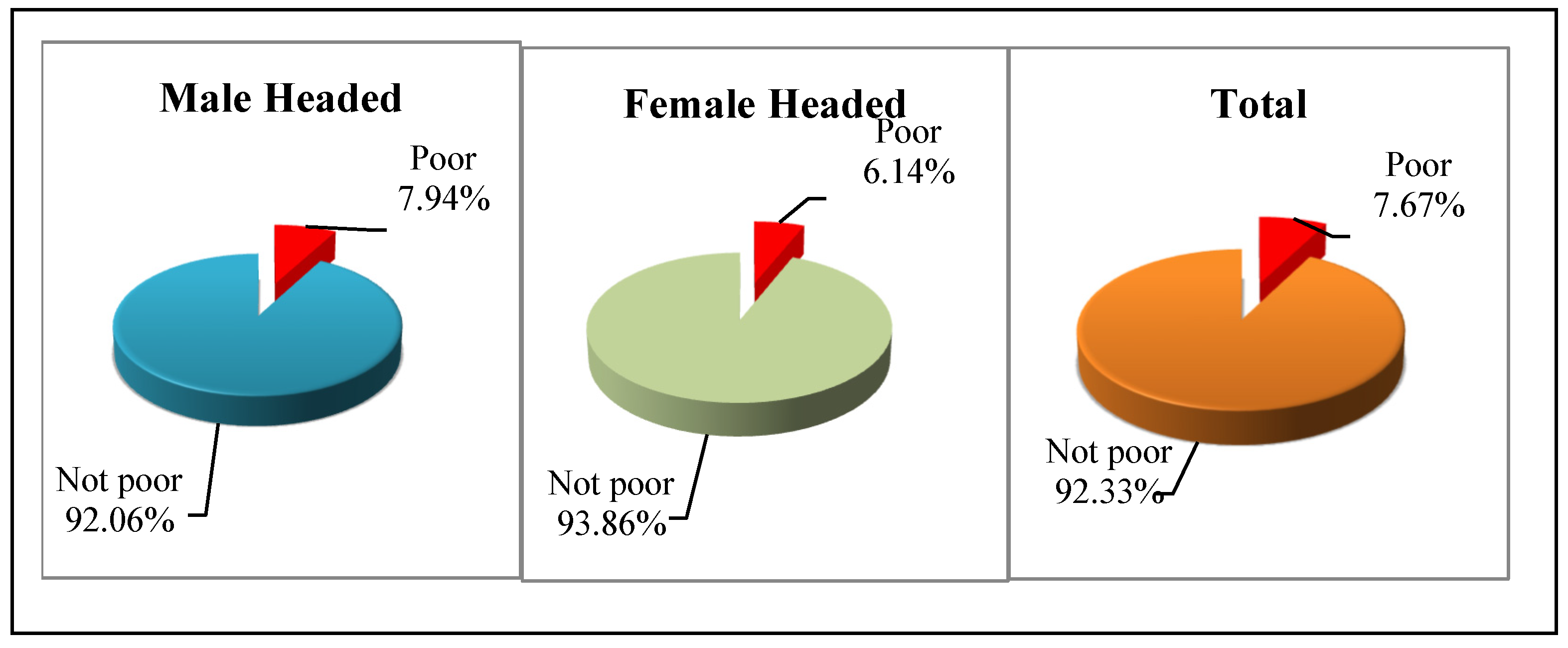

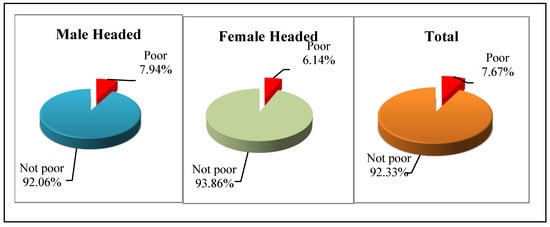

Figure 1 presents the poverty status across households with male and female heads. Of the total 291,231 households surveyed, 84.84% (247,074) were male-headed and 15.16% (44,157) were female-headed. Overall, 7.67% (22,329) of households were classified as poor, whereas 92.33% (268,902) were categorized as non-poor. When disaggregated by gender, the incidence of poverty was slightly higher among male-headed households, with 7.94% (19,616) falling below the poverty line. Conversely, only 6.14% (2713) of female-headed households were classified as poor. The remaining majority in both groups are non-poor households—92.06% (227,458) and 93.86% (41,444) of male-headed and female-headed households, respectively.

Figure 1.

Poverty status based on sex of head of household.

These findings challenge the commonly held assumption in previous poverty studies that female-headed households are universally more vulnerable to poverty. In this dataset, female-headed households exhibit a marginally lower poverty rate than male-headed households. This result may reflect diverse socio-economic dynamics, such as targeted social protection programs, higher resilience in female-headed households, or an underrepresentation of the most vulnerable women in formal surveys. However, this calls for cautious interpretation, as the structural disadvantages faced by female-headed households may manifest in non-monetary dimensions of poverty, which were not captured in this dataset.

Table 2 presents a descriptive overview of the sociodemographic and economic characteristics of households based on survey data. Demographically, the population is predominantly rural, with 59.92% of respondents residing in villages and the remaining 40.08% living in urban areas. Household heads were predominantly male, with 84.84% of households headed by men and 15.16% headed by women. This distribution reflects the sample’s prevailing patriarchal household leadership structure.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Regarding labor participation, 91.13% of husbands were employed, emphasizing their primary role as economic providers. Conversely, only 45.24% of wives were employed; the majority (54.76%) were not engaged in formal or informal employment. A similar gender pattern was observed regarding entrepreneurial engagement: 52.18% of husbands were entrepreneurs, compared with only 25.33% of wives. These results emphasize significant gender disparities in both labor force participation and economic autonomy, which may be influenced by sociocultural norms and unequal access to economic opportunities.

The respondents’ digital literacy appeared to be limited, with only 13.42% possessing information technology (IT) skills. This low level of digital competence may hinder access to digital markets and e-governance services, particularly in rural settings. Moreover, access to formal credit remains constrained, with only 20.67% of respondents reporting access to credit facilities. Such limitations in financial inclusion may adversely affect households’ economic resilience and entrepreneurial capacity.

The ownership of financial accounts further reveals gender discrepancies. Although 53.53% of husbands had bank accounts, only 46.46% of wives did, emphasizing the gender gap regarding financial inclusion. In terms of employment sector, most respondents were engaged in the primary sector (38.01%) and service industries (28.33%), followed by trade (13.12%) and secondary or industrial activities (12.22%). This indicates a labor structure that is heavily reliant on agriculture and services, which is consistent with the majority of the participants being from rural areas. Moreover, most households reported access to adequate sanitation (71.70%) and safe drinking water (86.22%). These findings suggest considerable progress in basic service provision, although disparities may still exist in remote or underserved regions. Overall, the descriptive statistics emphasized the interplay between geographic, gender, and economic factors in shaping household welfare and access to resources.

3.2. Model Estimation and Hypothesis Testing

The results of the multicollinearity estimation using the VIF test obtained an average VIF value of 1.72, which is smaller than 10. As suggested by Senaviratna and Cooray (2019) and Bayman and Dexter (2021), this result indicates that there is no collinearity among the independent variables used in the logistic model in this study. The results of the collinearity test for each independent variable also show the same result, namely, the absence of multicollinearity among the independent variables. This conclusion is based on the respective VIF values (see Table 3). Although some studies suggest that the logistic regression model does not require classical assumption tests like those used in multiple linear regression, such as normality, heteroscedasticity, and multicollinearity, the model’s feasibility test is a crucial step in ensuring that the logistic regression model is reliable and can be used to make accurate predictions. Regarding the feasibility test for the logistic regression model, the Hosmer and Lemeshow test was used, as suggested by Bayman and Dexter (2021). In this case, if the p-value from the Hosmer and Lemeshow test is greater than the specified significance level (0.05), then the model is considered to fit the data, which indicates that there is no significant difference between the observations and predictions.

Table 3.

The results of the multicollinearity test.

The results of logistic regression (Table 4) indicated that (1) years of education, (2) ownership of a bank account, (3) age, (4) domicile, (5) information technology skills, (6) working status, (7) working in the formal sector, (8) sanitation status, and (9) drinking water source were significantly associated with the likelihood of poverty. Similar results were found for the variable female-headed households; having an employment position tended to decrease the likelihood of poverty. This conclusion is based on the results of testing the influence of each independent variable on the dependent variable using the Wald test. If the p-value from the Wald test is less than 0.05, then the variable is considered to have a significant influence on the probability of the event (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 2000).

Table 4.

Logit regression results.

4. Discussion

A logit regression model was employed to estimate the likelihood of a household being poor, with the following key findings:

Female-headed households were less likely to be poor (β = −0.289 (see Table 4), marginal effect = −0.012% (Table 5)). Female-headed households show less likelihood of becoming poor, particularly when females have access to credit, education, or digital skills. Comparative studies have confirmed these vulnerabilities and emphasized the need for targeted policy interventions (Bradshaw et al., 2018; Zenebe, 2020). Interestingly, having a female as the head of a household (in the model) significantly decreased the likelihood of poverty, which confirmed the argument regarding the feminization of poverty. Inequality of employment opportunities, dual responsibilities as breadwinners and caregivers, and low productive assets are the main factors affecting this. This phenomenon, as observed in studies such as that from Mgomezulu et al. (2024), indicated that female-headed households, in both rural and urban areas, are directly and positively correlated with household income. This statement refers to the success of the Semillas Program in Mexico, which transformed 60,000 low-income households headed by women into self-sufficient microenterprises in three years. Moreover, JEEViKA has successfully impacted approximately 1.8 million women across numerous villages, demonstrating significant efficacy in enhancing women’s empowerment by augmenting their economic participation.

Table 5.

Logit marginal effects.

Furthermore, the ownership of bank account, by either spouse, is associated with a lower poverty risk, with stronger effects for the husband. The marginal effects of bank account ownership by a husband or wife are −0.027 and −0.010 (see Table 5), respectively, with a statistical significance value of p < 0.001 indicating that husbands who have bank accounts tend to be less poor by 2.7% and wives who have bank accounts have a 1% reduced chance of being poor. Bank account ownership is a key indicator of financial inclusion and plays a significant role in reducing the risk of household poverty. In the Indonesian context, the bank account ownership by either spouse indicates access to formal financial services, which can strengthen economic resilience, expand productive investment opportunities, and increase financial management capacity (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2020). Previous experimental studies indicated that access to a bank account encouraged saving behavior, reduced consumptive spending, and improved household economic stability (Bachas et al., 2021).

Social norms and patriarchal structures still place men as the main decision-makers in the household economy. Therefore, when bank accounts are owned by husbands, their use is more likely to be directly related to productive economic activities such as micro-enterprises, investments, or income management from the formal sector, which has a stronger effect on reducing the risk of poverty than if only the wife had an account. However, although the impact of women’s account ownership on poverty reduction is often hampered by limited access to waged work and other structural barriers, it remains important for fostering economic empowerment and financial independence. Thus, these findings confirmed that policies to increase bank account ownership need to more explicitly consider gender-related factors to optimize the potential for financial inclusion in the poverty alleviation agenda.

Cultural norms and financial control gaps limit women’s effective use of financial services, indicating the need for gender-sensitive financial literacy programs (Maina & Györke, 2025; Rink et al., 2021). Recent studies by Sun et al. (2022) and Wang and Do (2023) indicated that households with bank accounts have better economic resilience in the face of shocks such as pandemics or rising food prices; however, the result ultimately proved uneven. Behind these optimistic figures lies a deep inequality—the anti-poverty effect of bank account ownership is weaker among female-headed households than their male-headed counterparts. This can affect the ability of female-headed households to alleviate poverty, as revealed by Johnen and Mußhoff (2023). The root of the problem is multidimensional. In rural Bangladesh, a study by Hasan et al. (2023) found that although women have access to bank accounts, a lack of understanding of basic features such as digital payments and fund transfers hindered the effective use of digital financial services.

As presented in Table 4 and Table 5, access to credit, especially for women (CA wife), significantly reduces the likelihood of poverty (β = −0.088, marginal effect = −0.41%) at a 90% level of significance. Access to credit reduces the risk of poverty, and it is particularly effective for women during emergency situations, rather than being used for investment purposes. These findings indicate that from a household economic perspective, women, particularly wives, tend to allocate resources to activities oriented towards family well-being, such as child education, health, and consumption of nutritious food. When women have control over financial resources, family spending becomes more productive and has a long-term impact on poverty reduction. In Indonesia, women play a substantial role in the informal economy and micro-, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Many women, especially those in rural areas, operate homes or microbusinesses that support the family economy. Access to credit allows them to expand their businesses, increase working capital, and create income diversification. This reduces a household’s vulnerability to economic shocks and strengthens its economic resilience to structural poverty. Additionally, wives having access to credit has a social empowerment effect. When loans are managed by women it increases their self-confidence, bargaining position in household decision-making, and participation in socio-economic activities.

Additionally, our findings reflect gender barriers in accessing productive loans owing to limited collateral, the trust of financial institutions, and social norms. Microcredit programs targeted at women in rural China increase women’s empowerment, but poverty reduction is relatively lower in female-headed households compared to male-led households (Wu et al., 2024). In addition, differences were evident in the investment behavior of smallholder farms led by women or men in microcredit programs in Western Kenya. The findings showed that although women participate more frequently and have higher loan repayment rates, the impact on poverty reduction is more significant in male-led households (Jindo et al., 2023).

The logistic regression results indicated a statistically significant and negative impact of household IT skills in relation to poverty status. In Table 4, the estimated coefficient for IT skills is β = −0.283, with a standard error of 0.033; this was significant at the 1% level. The marginal effect is 0.0137 (Table 5), indicating that households with IT skills are 1.37 percentage points less likely to be poor when holding other factors constant. This finding emphasized the potential of digital literacy in enhancing household economic outcomes. IT skills may contribute directly to income-generating opportunities (e.g., digital entrepreneurship, remote work) or indirectly by improving access to information, financial services, and markets.

IT skills had a significant adverse effect on poverty across all models, emphasizing the importance of digital literacy in enhancing well-being. In this era of a rapidly growing digital economy, IT skills have become a key differentiator between poverty and prosperity. A recent study (J. Zhang et al., 2024) revealed that mastering basic digital skills can reduce the risk of poverty in rural households. However, attitudes towards technology play a role in explaining the digital skills gap between male and female students, emphasizing the importance of addressing the attitude gap to improve women’s digital skills (Campos & Scherer, 2024).

Furthermore, the employment of both the husband and wife is associated with significantly lower poverty, particularly for the husband. The estimation results reveal that the marginal effects of employment status for both spouses are negatively and statistically significant. Specifically, the marginal effect for the husband’s employment status is slightly higher at 2.6%, while the wife’s employment status is at 0.7%, with both effects significant at the 0.1% level (p < 0.001) (see Table 5). This finding suggest that when either spouse is employed, the likelihood of the household escaping poverty increases considerably, with the wife’s employment contributing a slightly greater effect. This highlights the critical role of dual-earner households in reducing poverty risk, particularly in contexts where women’s economic participation is often undervalued or constrained.

However, women frequently encounter structural barriers that hinder their full engagement, such as patriarchal cultural norms, restrictive gender roles, and institutional policies, that collectively limit their opportunities for paid employment. The study by Israni and Kumar (2021) provides compelling evidence of how such structural barriers continue to impede women’s participation in paid work, thereby reinforcing economic disparities and undermining poverty alleviation efforts. Addressing these systemic challenges is essential to unlocking the potential of the female labor force and enhancing household economic resilience. Even when women work, they continue to bear a domestic burden and have reduced income from benefits, reinforcing structural poverty as a long-term issue. M. Zhang et al. (2024) emphasized that women, especially female heads of households, face higher vulnerability to poverty owing to structural inequalities in access to capital, property, and financial services. Conversely, the cultural patriarchy in Indonesia necessitates women obtaining their husbands’ approval in financial decisions, even though they are the day-to-day business managers. This suppresses the positive influence of self-efficacy in applying for credit (Mardika et al., 2024).

Moreover, the sector of employment also determines the probability of becoming poor. Employment in the primary sector is significantly associated with an increased risk of poverty compared to employment in sectors such as trade and services (β = 0.261 and marginal effect = 0.012, p < 0.001). As presented in Table 4, regression results indicate that individuals employed in the primary sector have a 1.2 percentage point higher probability of falling into poverty than those working in other sectors. Job positions and the formal sector show varying influences. Working in the primary sector increases the risk of poverty compared to working in other sectors. Nonetheless, the effect appears to be less pronounced among female-headed households, as women are disproportionately concentrated in employment that lacks social protection and adequate remuneration. Liu (2019) reveals that, despite women’s high participation rates in agriculture and production, they are often confined to occupations with low professional status and low wages. Syahreza et al. (2024) indicated that 68% of female workers in Indonesia’s manufacturing sector are employed in low-wage jobs without social security, with wages 35% lower than those of their male counterparts for equal work. Sajjad and Eweje (2021) stated that female workers, particularly those in manufacturing sectors (such as garment manufacture), experienced a significant decrease in employment and income, increasing their vulnerability to poverty.

Despite some advances, the findings from the Wald test indicate that age negatively and significantly influences the probability of being poor (β = −0.011, p < 0.001), although the marginal effect remains relatively small at 0.05% (Table 5). This suggests that each additional year in the age of a female household head slightly reduces the likelihood of experiencing poverty. This result aligns with the argument presented by Ainistikmalia (2019), who noted that, particularly among older women, there is increased vulnerability to poverty, thereby underscoring the importance of targeted social protection measures for aging female populations. Marital status has a significant effect on men, consolidating their traditional role as the primary income earner (Cui et al., 2025; Syrda, 2020). Opportunities to escape the grip of poverty differ between men and women based on age. Data from developing countries, including Indonesia, reveal that, for men, increasing age is like a ladder that helps them get out of poverty. Each additional decade of age reduces their risk of poverty, as found by Do et al. (2025) in Vietnam and Thailand. Their study provided important insights into how the age of the household head can protect against poverty in rural Southeast Asia. Using panel data from Vietnam and Thailand, they found that households with older heads tended to have stronger economic resilience to various social and economic shocks. This suggests that an older age not only provides life experience but also increases the ability of families to escape the poverty trap, both in absolute and multidimensional terms. This finding emphasizes the importance of integrating the roles of older adults into development policies to promote effective and sustainable poverty alleviation. In Indonesia, men aged 45–60 years have a poverty rate that is 15% lower than younger age groups (Badan Pusat Statistik, 2023a). The mechanism for this is detailed and indicates that accumulated work experience, an extensive professional network, and access to more stable formal work become valuable capital. A similar pattern is observed in the study by Sugiharti et al. (2022) in Indonesia, which found that mature male informal workers have a greater chance of switching to formal employment compared to younger workers.

The logistic regression results indicated a negative impact for age on poverty status in Indonesia, as showed in Table 4. This result indicates that older age groups tend to have a lower probability of being poor than younger age groups. This phenomenon can be explained through several social, economic, and cultural factors that are typical in the Indonesian context. First, older individuals have generally achieved relative economic stability owing to their accumulated assets and longer work experience. Several of these individuals already have their own homes, either through purchases during productive times or family inheritance. Fixed-asset ownership reduces the expenditure burden and increases economic resilience to poverty. In addition, most older adults in Indonesia have strong social networks, including financial and non-financial support from children or other family members. This corresponds with the values of collectivism and intergenerational responsibility, which remain strong in Indonesian society. Second, social protection reduces older adults’ economic vulnerability. Several government programs, such as the Family Hope Program (PKH), Non-Cash Food Assistance (BPNT), and pensions for civil servants, provide protection that assists older adults in maintaining their standard of living above the poverty line. Therefore, formal and informal support for older adults allows them to survive in decent economic conditions, even if they are no longer economically productive. Conversely, younger age groups, particularly those aged 20–35, face a higher risk of poverty. This is related to the relatively high unemployment rate in this age group, the dominance of informal work, and limited access to decent and stable jobs. In addition, the younger generation often experiences economic burdens, such as loan repayment installments and education costs, and does not have productive assets, making them more vulnerable to economic shocks. Thus, the negative correlation between age and poverty reflects a structural condition in which older individuals in Indonesia tend to be more socially and economically protected, whereas younger age groups are more vulnerable to poverty due to job instability and limited access to economic resources.

Education was inversely associated with poverty. This conclusion is based on a Wald test in which its probability value is less than 0,05 (β = −0.089, p < 0.000). The negative sign implies that each additional year of education reduces the probability of poverty by 0.42%. This emphasizes the role of education as key instrument in vertical social mobility. These findings are consistent with previous findings, such those by Panyi et al. (2025) and Spada et al. (2023), which indicated that education not only expands individuals’ access to higher-quality employment but also increases productivity, adaptability to labor market changes, and financial resilience in the long term. Previous findings indicate that education enhances labor market participation and increases income opportunities (Ariansyah et al., 2024; Wicaksono et al., 2023). These findings confirm that each year of formal education lowers the probability of individuals stagnating in poverty, thereby reinforcing education’s role as a social equalizer. Investment in education has long-term impact on poverty reduction, not only for individuals who receive education but also for families across generations. One study (Yu et al., 2025) found that the educational level of children was significantly associated the risk of poverty for their parents in old age. Therefore, increasing children’s educational abilities significantly reduces the likelihood of their parents experiencing poverty, in both absolute and relative terms. This finding strengthens the argument that education is not only an instrument of individual development, but also an effective social mechanism to break the chain of poverty between generations. Thus, policies that promote access to education or improve the quality of it can be seen as an investment strategy in the sustainable poverty alleviation agenda. These results align with the study by Sulistyaningrum and Tjahjadi (2022), which found that workers with lower levels of education tend to experience higher income inequality than those with secondary or tertiary education. By increasing access to and engagement with formal education, particularly at the primary and secondary levels in rural areas, income disparities across social groups can be reduced more evenly. Therefore, policies that encourage widespread school participation are crucial in Indonesia’s inequality reduction agenda.

Examining Table 4 and Table 5, a larger family size (HHsize) increases the likelihood of poverty (β = 0.479, marginal effect = 0.023%, p < 0.001). Family size influences poverty positively and significantly across the model. Each additional family member increases the likelihood of poverty, indicating the burden of dependents within a household. However, the coefficient is slightly lower for female-headed households, which may be because of the presence of social networks or more efficient consumption patterns. Family size is an important determinant of poverty in Indonesia. In Indonesia’s socio-economic context, the higher the number of family members, the greater the household’s consumption needs. This can trigger significant economic pressure, particularly for households with limited sources of income. Several underlying reasons for this can be suggested. First, the limited distribution of resources is a major obstacle. In many cases, the household income in Indonesia does not increase proportionally with the increase in family members. For example, if a household is dependent on one or two sources of income, additional family members, particularly those who are not economically productive such as children or older adults, will increase the burden of consumption without increasing income capacity. Consequently, the per capita expenditure decreases and the risk of malnutrition, low education, and limited access to health services increases, all of which contribute to long-term poverty. Second, the quality of resource investment per household member tends to decline in large families. In small families, parents tend to be able to provide better attention, education, and nutrition for each child. However, in large families, these resources must be shared, which leads to a decrease in the quality of human investment. Previous empirical studies in Indonesia found that children from large families tend to have lower levels of education, which in turn increases their chances of escaping intergenerational poverty.

Third, a gap exists concerning access to productive employment, particularly in rural areas or areas with low economic growth. Consequently, households with many family members face significant internal competition in terms of access to work, which exacerbates economic pressures. Additionally, the burden of childcare often falls on women, which can reduce their participation in the formal workforce, reinforcing their economic dependence on a single source of income. Fourth, cultural factors and social norms in some regions in Indonesia encourage the idealization of large families; however, this has not been accompanied by economic readiness or adequate social support. This mismatch between family structure and economic conditions is a structural factor that strengthens the cycle of poverty. Thus, within the household economics framework, large family sizes in Indonesia are a significant risk factor for poverty because they increase the burden of consumption, decrease investment per individual, and weaken a family’s long-term economic resilience.

Our results align with those in a study on household dynamics by M. Zhang et al. (2024), who found that female-headed households are often better able to manage resources economically, despite their limitations. In Ghana, although female-led household incomes are rarer (about 20% compared to male-led households), they tend to invest 31% to 38% more in children’s education. These findings show that women effectively manage resources for long-term priorities despite facing financial constraints (Asiedu et al., 2024). Although female-led households in the U.S. have higher poverty rates, the women leading them are more likely to work full-time and manage resources efficiently to reduce child poverty. This demonstrates the ability of women to manage resources despite facing economic challenges (Sharma, 2023).

Furthermore, domicile—particularly the distinction between urban and rural areas—substantially impacts poverty rates. The results of the logit regression estimation show that the domicile variable has a significant effect on the probability of poverty. A logit regression coefficient of −0.329 with p < 0.001 indicates that living in urban areas reduces the chances of becoming poor compared to rural households. A marginal effect of −0.015 indicates that households in urban areas have a 1.5% chance of being poor. Living in urban areas generally reduces the risk of poverty due to better access to education, health services, and economic opportunities. However, these benefits are not always shared equally between groups, especially female-headed households. In Indonesia, before the implementation of the Village Fund Program, the poverty rate in rural areas was approximately 7.6% higher than that in urban areas. Following the program’s implementation, a significant reduction in rural poverty rates was achieved, demonstrating the effectiveness of community-based interventions in reducing poverty disparities between regions.

In a glittering city that promises better jobs and access to services, not all residents experience the same advantages in fighting poverty. Data from various developing countries reveal that living in urban areas reduces the risk of poverty compared to rural areas, as Christiaensen and Todo (2014) found in their study of developing countries. In Vietnam, urbanization reduced the poverty rate through job creation and industrial (manufacturing) sector growth (Pham & Riedel, 2019).

However, women do not experience the success story of urbanization. Many urban women experience poverty in the narrow alleys of the slums of Jakarta or Mumbai that is no less severe than their sisters in village settings. Munguía (2024) found that the anti-poverty benefits of city living were less pronounced for women, who remain more vulnerable to poverty—particularly higher levels or poverty—despite living in cities that should offer more economic opportunities. Women in the urban areas of developing countries face significant barriers to accessing safe and affordable public transportation. These barriers include limited infrastructure, high transportation costs, and safety concerns, all of which reduce women’s mobility and their access to decent employment opportunities (Borker, 2024).

Sanitation has a statistically significant negative relationship with poverty (β = −0.284, marginal effect = −0.014%, p < 0.001), whereas access to safe drinking water had no significant relationship. Access to sanitation and adequate sources of drinking water have a negative correlation with poverty. However, the effects of access to drinking water are not significant for female-headed households. This indicates that the quality of basic infrastructure does not always guarantee prosperity without equal economic access. In some cases, female heads of households are often left behind in terms of access to adequate sanitation. These inequalities are exacerbated by structural barriers, limited economic opportunities, and deepening poverty (Mercer, 2023). Furthermore, Goodman et al. (2022) found that women’s participation in a group-led microfinance program in Kenya significantly increased their social capital, which in turn contributed to reducing water and food insecurity. These findings suggested that when women build trust and solidarity through microfinance groups, they not only gain better access to water but also increase household economic resilience, particularly among vulnerable families and women-led households.

Overall, these findings strengthen the understanding that education, finance, digitalization, and living conditions significantly influence poverty status, while emphasizing the importance of a gender-based approach in designing effective poverty alleviation policies. The same variables have different impacts on female-headed households, emphasizing the need for more targeted interventions, such as expanding women’s access to business capital and digital skills training and implementing social protection tailored to the needs of female-headed households.

5. Conclusions

This study provides robust evidence that poverty is shaped by a convergence of factors, including educational attainment, gender dynamics, financial access, sectoral employment, digital skills, and infrastructure. Furthermore, this study emphasized the critical role of gender in shaping multidimensional poverty outcomes in Indonesia. In particular, female-headed households experience increased vulnerability owing to intersecting weaknesses such as limited educational attainment, reduced access to financial services, and lower levels of digital literacy. These findings emphasize the urgent need for gender-responsive strategies that extend beyond income-based measures.

Policy efforts must prioritize equitable access to digital skills education and training, particularly for women in rural and underserved areas. Financial inclusion initiatives must cater to the unique needs of female-led households and ensure access to credit, savings, and digital financial platforms. In addition, the labor market must evolve to support more inclusive employment opportunities and social protections that reduce the systemic barriers women face.

Therefore, addressing female poverty requires an integrated, multi-sectoral approach that combines economic, technological, and institutional reforms. Future research should continue to explore the pathways in which gender dynamically intersects with poverty, leveraging both quantitative and qualitative data. By strengthening the empirical foundation for gender-sensitive development policies, Indonesia can take essential steps towards inclusive and sustainable poverty alleviation.

The multidimensional poverty measurement paradigm employed in this investigation, while elucidative, can be enhanced through the incorporation of a broader array of indicators and a more meticulous methodological framework. The implementation of a more advanced Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) within the empirical construct has the potential to enrich the analysis and yield more precisely tailored policy implications. In addition, the absence of interaction variables is a limitation that needs to be considered. This research predominantly draws upon quantitative data, which, despite considerable generalizability, may overlook contextual and subjective experiences that could be effectively captured through a qualitative methodology. Therefore, future research should use a mixed-methods design to enrich our understanding of the social, cultural and institutional barriers that exacerbate gender-based poverty. Additionally, future studies should explicitly include interaction variables to obtain a more holistic and responsive understanding of the issue of gender inequality in multidimensional poverty. In parallel, incorporating multidimensional poverty into a more robust model will generate more detailed policy implications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.E., R.E.F. and K.S.; methodology, R.A.E. and K.S.; software, R.E.F. and R.N.; validation, R.E.F. and R.N.; formal analysis, R.A.E., R.E.F. and K.S.; investigation, R.N. and R.E.F.; resources, R.A.E. and Y.Y.; data curation, R.N.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.E. and R.E.F.; writing—review and editing, R.A.E., R.E.F. and K.S.; visualization, R.E.F. and R.N.; supervision, R.A.E.; project administration, Y.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study are available from the corresponding author at reasonable request. The Data Micro Susenas can be assessed at Available online: https://silastik.bps.go.id/v3/index.php/site/login/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Achia, T. N., Wangombe, A., & Khadioli, N. (2010). A logistic regression model to identify key determinants of poverty using demographic and health survey data. European Journal of Social Sciences, 13, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ainistikmalia, N. (2019). Determinants of the elderly female population with low economic status in Indonesia. Jurnal Ilmu Ekonomi Terapan, 4(2), 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, B. R. C. (2017). Absolute poverty: When necessity displaces desire. American Economic Review, 107(12), 3690–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, S., & Olivos, F. (2024). Low income, Ill—being, and gender inequality: Explaining cross—National variation in the gendered risk of suffering among the poor. In Social indicators research (Vol. 174, Issue 1). Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariansyah, K., Wismayanti, Y. F., Savitri, R., Listanto, V., Aswin, A., Ahad, M. P. Y., & Cahyarini, B. R. (2024). Comparing labor market performance of vocational and general school graduates in Indonesia: Insights from stable and crisis conditions. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 16(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, E., Karimu, A., & Iddrisu, A. G. (2024). Structural changes in African households: Female-headed households and children’s educational investments in an imperfect credit market in Africa. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 68, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atozou, B., Mayuto, R., & Abodohoui, A. (2017). Review on gender and poverty, gender inequality in land tenure, violence against woman and women empowerment analysis: Evidence in Benin with survey data. Journal of Sustainable Development, 10(6), 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachas, P., Gertler, P., Higgins, S., & Seira, E. (2021). How debit cards enable the poor to save more. Journal of Finance, 76(4), 1913–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayman, E., & Dexter, F. (2021). Multicollinearity in logistic regression models. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 133(2), 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikorimana, G., & Sun, S. (2020). Multidimensional poverty analysis and its determinants in Rwanda. International Journal Economic Policy in Emerging Economies, 13(5), 555–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, S. N., Mishra, S. K., & Sarangi, M. K. (2020). Feminization of multidimensional poverty in Rural Odisha. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studie in Humanities, 12(5), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Borker, G. (2024). Understanding the constraints to women’s use of urban public transport in developing countries. World Development, 180, 106589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badan Pusat Statistik. (2023a). Berita Resmi Statistik 2023. Available online: http://www.bps.go.id/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Badan Pusat Statistik. (2023b, January 16). Percentage of poor population in September 2022 increased to 9.57 percent. Official Statistics News No. 07/01/Th. XXVI. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/id/pressrelease/2023/01/16/2015/persentase-penduduk-miskin-september-2022-naik-menjadi-9-57-persen.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Bradshaw, S., Chant, S., & Linneker, B. (2017). Gender and poverty: What we know, don’t know, and need to know for Agenda 2030. Gender, Place & Culture, 24, 1667–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, S., Chant, S., & Linneker, B. (2018). Challenges and changes in gendered poverty: The feminization, de-feminization, and re-feminization of poverty in Latin America. Feminist Economics, 25(1), 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D. G., & Scherer, R. (2024). Digital gender gaps in students’ knowledge, attitudes and skills: An integrative data analysis across 32 countries. In Education and information technologies (Vol. 29, Issue 1). Springer US. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiaensen, L., & Todo, Y. (2014). Poverty reduction during the rural-urban transformation—The role of the missing middle. World Development, 63, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D. R. (2018). Analysis of binary data. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozarenco, A., & Szafarz, A. (2023). Financial inclusion in high-income countries: Gender gap or poverty trap? In Handbook of microfinance, financial inclusion and development (pp. 272–296). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, S., Jing, F. F., Ma, H., Zhu, M., Yan, Y., & Wang, S. (2025). A longitudinal dyadic analysis of financial strain and mental distress among different-sex couples: The role of gender division of labor in income and housework. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2020). The global Findex database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and opportunities to expand access to and use of financial services. World Bank Economic Review, 34(2018), S2–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M. H., Nguyen, T. T., & Grote, U. (2025). Insights on household’s resilience to shocks and poverty: Evidence from panel data for two emerging economies in Southeast Asia. Climate and Development, 5529, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, N. N. (2022). The impact of household head labor status and worker characteristics on household poverty: Evidence in Vietnam. Journal of Eastern European and Central Asian Research, 9(3), 432–466. [Google Scholar]

- Edwar, J., & Blanca, H. (2022). Vulnerability to multidimensional poverty: An application to Colombian households. Social Indicators Research, 164(1), 345–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egyir, I. S., O’Brien, C., Bandanaa, J., & Opit, G. P. (2023). Feeding the future in Ghana: Gender inequality, poverty, and food insecurity. World Medical & Health Policy, 15(4), 638–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emara, N., & Mohieldin, M. (2020). Financial inclusion and extreme poverty in the MENA region: A gap analysis approach. Review of Economics and Political Science, 5(3), 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. H. (2001). Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data-or tears: An application to educational enrollments in States of India. Demography, 38(1), 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Vélez, D., & Nuñez Velázquez, J. J. (2021). A network analysis approach in multidimensional poverty. Poverty and Public Policy, 13(1), 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, M. L., Elliott, A., & Melby, P. C. (2022). Water insecurity, food insecurity and social capital associated with a group-led microfinance programme in semi-rural Kenya. Global Public Health, 17(6), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, F. E., Jr. (2015). Regression modeling strategies. In Binary logistic regression (Issue 2). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R., Ashfaq, M., Parveen, T., & Gunardi, A. (2023). Financial inclusion—Does digital financial literacy matter for women entrepreneurs? International Journal of Social Economics, 50(8), 1085–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D. W., Jr., & Lemeshow, S. (2000). Applied logistic regression (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isah Abubakar, I., & Lawal, M. (2024). The determinants of the correlates of poverty among households in Sokoto state, Nigeria: Evidence from binary logistic model. International Journal of Law, Politics and Humanities Research, 6(6), 174–188. Available online: https://cambridgeresearchpub.com/ijlphr/article/view/389 (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Israni, M., & Kumar, V. (2021). Gendered work and barriers in employment increase unjust work–life imbalance for women: The need for structural responses. International Journal of Community and Social Development, 3(3), 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindo, K., Andersson, J. A., Quist-Wessel, F., Onyango, J., & Langeveld, J. W. A. (2023). Gendered investment differences among smallholder farmers: Evidence from a microcredit programme in western Kenya. Food Security, 15(6), 1489–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnen, C., & Mußhoff, O. (2023). Digital credit and the gender gap in financial inclusion: Empirical evidence from Kenya. Journal of International Development, 35(2), 272–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N., Maharjan, K., & Piya, L. (2012). Determinants of income and consumption poverty in far-western rural hills of Nepal―A binary logistic regression analysis. Journal of Contemporary India Studies: Space and Society, 2, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Klasen, S. (2018). The impact of gender inequality on economic performance in developing countries. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 10(1), 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. S., & Jie, Q. (2023). Exploring the role of financial inclusion in poverty reduction: An empirical study. World Development Sustainability, 3, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebni, J. Y., Gharehghani, M. M. A., Soofizad, G., Khosravi, B., Ziapour, A., & Irandoost, S. F. (2020). Challenges and opportunities confronting female-headed households in Iran: A qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health, 20(1), 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. (2019). What does in-work poverty mean for women: Comparing the gender employment segregation in Belgium and China. Sustainability, 11, 5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, F. (2023). Empowering women through digital financial inclusion: Comparative study before and after COVID-19. Sustainability, 15, 9154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, C. W., & Györke, D. K. (2025). A selective systematic review and bibliometric analysis of gender and financial literacy research in developing countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(3), 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardika, D. R. W., Damayanti, T. W., Rita, M. R., & Supramono, S. (2024). Determinants of discouraged borrowers and gender as contextual factors: Evidence from Indonesian MSMEs. Cogent Business and Management, 11(1), 2336300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullagh, P. (2019). Generalized linear models. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, E. (2023). Exploring female-headed households’ sanitation needs, Tasikmalaya. (SLH Learning Paper 17). The Sanitation Learning Hub. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgomezulu, W. R., Dar, J. A., & Maonga, B. B. (2024). Gendered differences in household engagement in non-farm business operations and implications on household welfare: A case of rural and Urban Malawi. Social Sciences, 13(12), 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorosi, P. (2009). Gender, skills development and poverty reduction. Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, 81, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Munguía, J. T. (2024). Identifying gender-specific risk factors for income poverty across poverty levels in Urban Mexico: A model-based boosting approach. Social Sciences, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurdiansyah, S., & Khikmah, L. (2020). Binary logistic regression analysis of variables that influence poverty in central Java. Journal of Intelligent Computing & Health Informatics, 1(1), 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Obayelu Abiodun, E., & Ogunlade, I. (2006). Analysis of the uses of information and communication technology for gender empowerment and sustainable poverty alleviation in Nigeria. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology, 2(3), 45–69. [Google Scholar]

- Omenihu, C. M., Brahma, S., Katsikas, E., Vrontis, D., Siachou, E., & Krasonikolakis, I. (2024). Financial inclusion and poverty alleviation: A critical analysis in Nigeria. Sustainability (Switzerland), 16(19), 8528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panyi, A. F., Whitacre, B. E., & Young, A. (2025). The shifting relationship between educational attainment and poverty: Analysis of seven deep southern states. Annals of Regional Science, 74(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, U. J., & Mistiaen, J. A. (2018). Household expenditure and poverty measures in 60 min: A new approach with results from Mogadishu. In World Bank policy research working paper (p. 8430). the Poverty and Equity Global Practice. Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/research (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Pham, T. H., & Riedel, J. (2019). Impacts of the sectoral composition of growth on poverty reduction in Vietnam. Journal of Economics and Development, 21(2), 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, M. S., & Hartono, D. (2024). The financial inclusion gender gap: A case study of households in Indonesia. Jurnal Ekonomi Dan Studi Pembangunan, 16(2), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M. H., Kabir, M. S., Moon, M. P., Ame, A. S., & Islam, M. M. (2021). Gender role on food security and consumption practices in Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology, 39(9), 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D. P. (2006). Poverty measurement using expenditure approach. School of Economics, University of Queensland. [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion, M. (2020). On measuring global poverty. Annual Review of Economics, 12(1), 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, U., Walle, Y. M., & Klasen, S. (2021). The financial literacy gender gap and the role of culture. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 80, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A. G., & Smith, S. M. (1994). A comparison of determinants of urban, rural and farm poverty in Costa Rica. World Development, 22(3), 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, A., & Eweje, G. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic: Female workers’ social sustainability in global supply chains. Sustainability, 13(22), 12565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaviratna, N. A. M. R., & Cooray, T. M. J. A. (2019). Diagnosing multicollinearity of logistic regression model. Asian Journal of Probability and Statistics, 5(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M. (2023). Poverty and gender: Determinants of female-and male-headed households with children in poverty in the USA. Sustainability, 15(9), 7602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, A., Fiore, M., & Galati, A. (2023). The impact of education and culture on poverty reduction: Evidence from Panel data of European countries. Social Indicators Research, 175(3), 927–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiharti, L., Aditina, N., & Esquivias, M. A. (2022). Worker transition across formal and informal sectors: A panel data analysis in Indonesia. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 12(11), 923–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistyaningrum, E., & Tjahjadi, A. M. (2022). Income inequality in Indonesia: Which aspects cause the most? Journal of Indonesian Economy and Business, 37(3), 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L., Small, G., Huang, Y. H., & Ger, T. B. (2022). Financial shocks, financial stress and financial resilience of Australian households during COVID-19. Sustainability, 14(7), 3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahreza, D. S., Harmen, H., Zulfri, A., Chintia, A., Fonataba, P. W., Rahma, Z., & Malau, S. (2024). Implikasi kebijakan untuk mengatasi kesenjangan upah gender di lingkungan kerja manufaktur. Growth, 22(1), 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrda, J. (2020). Spousal relative income and male psychological distress. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(6), 976–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H. T. T., & Le, H. T. T. (2021). The impact of financial inclusion on poverty reduction. Asian Journal of Law and Economics, 12(1), 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranmer, M., & Elliot, M. J. P. (2008). Binary logistic regression. In Cathie marsh for census and survey research (pp. 454–490). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukur, K., & Usman, A. U. (2016). Binary logistic regression analysis on addmitting students using jamb score. International Journal of Current Research, 8(1), 25235–25239. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M., & Do, M. H. (2023). Reported shocks, households’ resilience and local food commercialization in Thailand. Journal of Economics and Development, 25(2), 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W., Sarker, T., Żukiewicz-Sobczak, W., Roy, R., Monirul Alam, G. M., Rabbany, M. G., Hossain, M. S., & Aziz, N. (2021). The influence of women’s empowerment on poverty reduction in the rural areas of Bangladesh: Focus on health, education and living standard. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, P., Theresia, I., & Al Aufa, B. (2023). Education–occupation mismatch and its wage penalties: Evidence from Indonesia. Cogent Business and Management, 10(3), 2251206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B., Niu, L., Tan, R., & Zhu, H. (2024). Multidimensional relative poverty alleviation of the targeted microcredit in rural China: A gendered perspective. China Agricultural Economic Review, 16(3), 468–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, S., Lee, H. S., & Liew, P. X. (2023). The role of financial inclusion in achieving finance-related sustainable development goals (SDGs): A cross-country analysis. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 36(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S., Guo, Q., & Liang, Y. (2025). The power of education: The intergenerational impact of children’s education on the poverty of Chinese older adults. International Journal of Educational Development, 116, 103297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenebe, A. (2020). Feminization of multidimensional urban poverty in sub—Saharan Africa: Evidence from selected countries. African Development Review, 32(4), 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Wang, D., Ji, M., Yu, K., Qi, M., & Wang, H. (2024). Digital literacy, relative poverty, and common prosperity for rural households. International Review of Financial Analysis, 96, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., You, S., Yi, S., Zhang, S., & Xiao, Y. (2024). Vulnerability of poverty between male-and female-headed households in China. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).