More or Less Openness? The Credit Cycle, Housing, and Policy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Literature

3. The Model

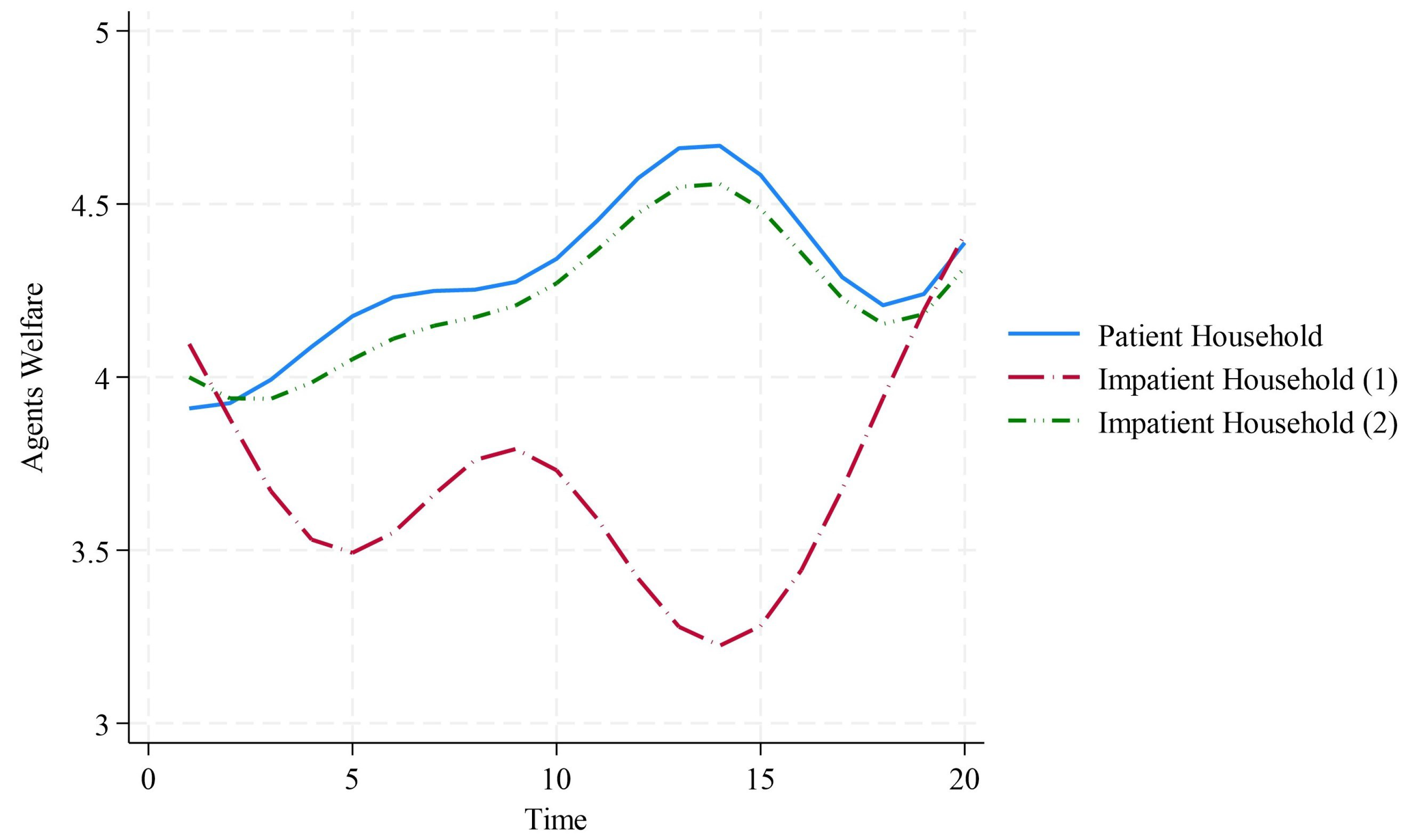

3.1. Households

3.2. Firms

3.2.1. The Production of Final Goods

The Demand of Consumption Goods

The Phillips Curve

3.2.2. Intermediate Production—Reproducible Capital

Rental Capital

Capital Production

3.2.3. Housing Production

3.3. Intermediaries (Banks)

3.4. Market-Clearing Conditions

3.4.1. Labor Market

3.4.2. Physical Capital Market

3.4.3. Housing Market

3.4.4. Lending

3.4.5. Final Output

3.5. The Credit Cycle

3.5.1. Credit Constraint

3.5.2. Credit Expansion

4. Monetary Policy and the Credit Cycle

4.1. Perfect Competition

4.1.1. Perfect Foresight

4.1.2. Imperfect Foresight

4.2. Cournot Competition

4.2.1. Perfect Foresight

4.2.2. Imperfect Foresight

4.3. Monetary Policy

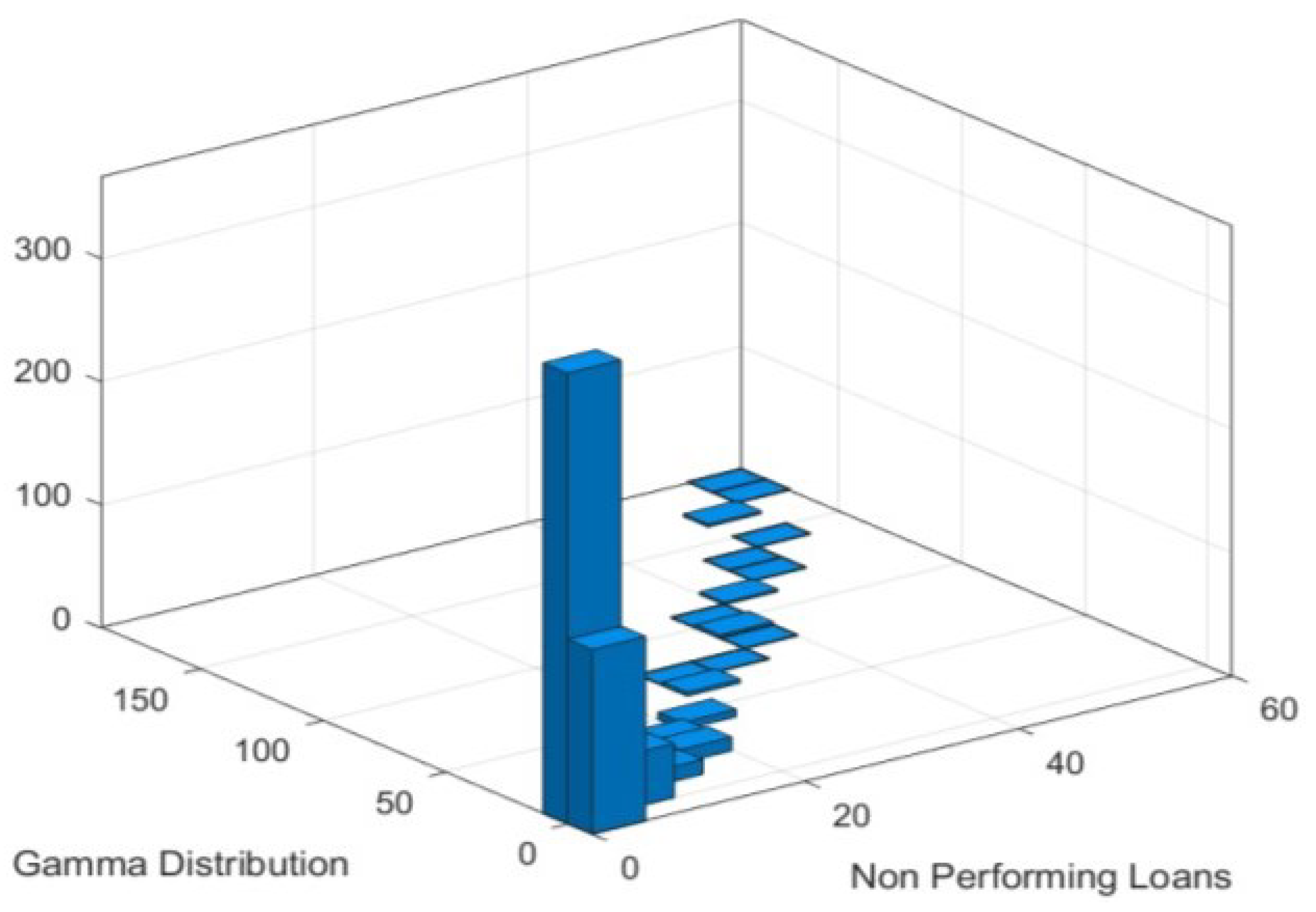

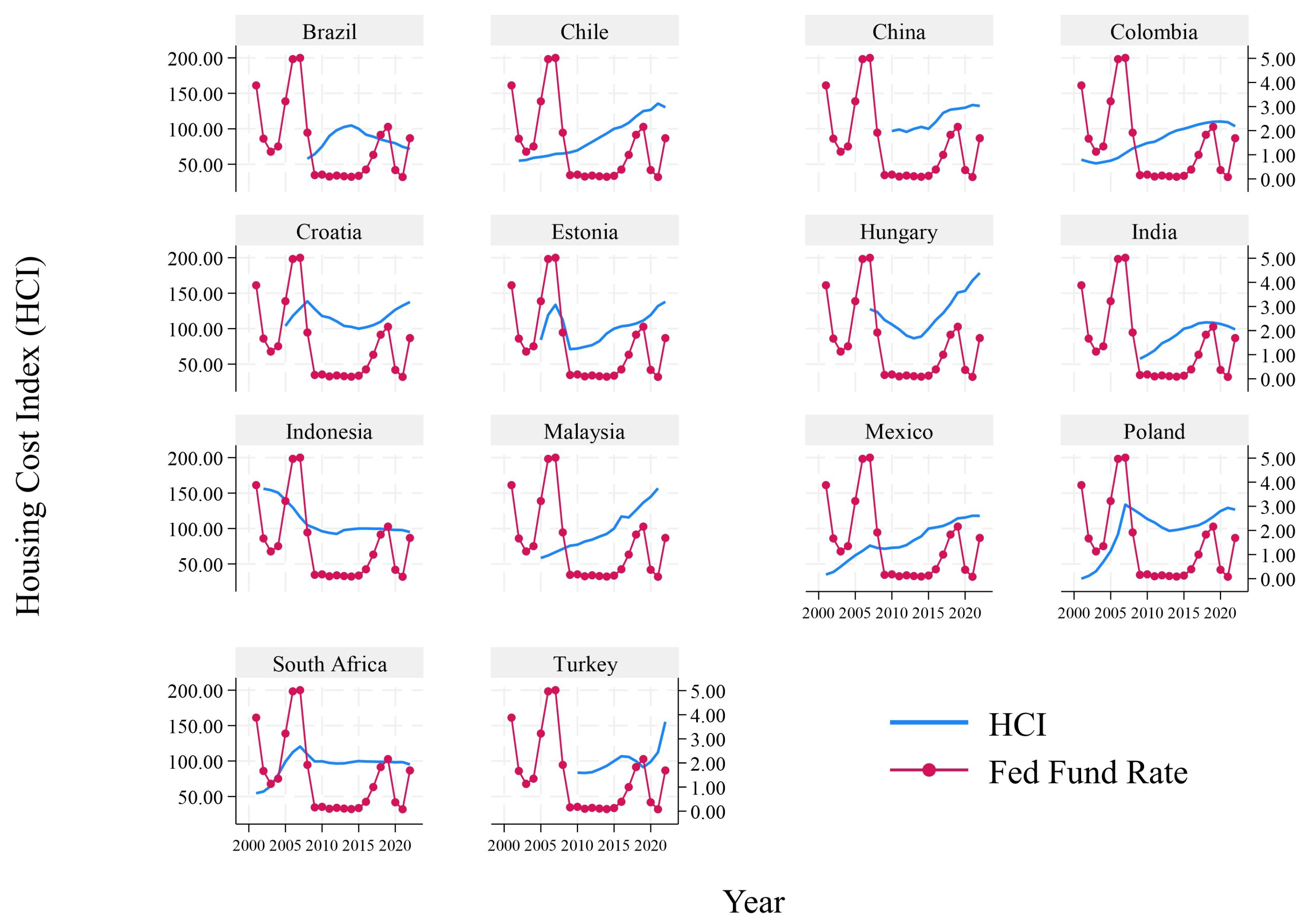

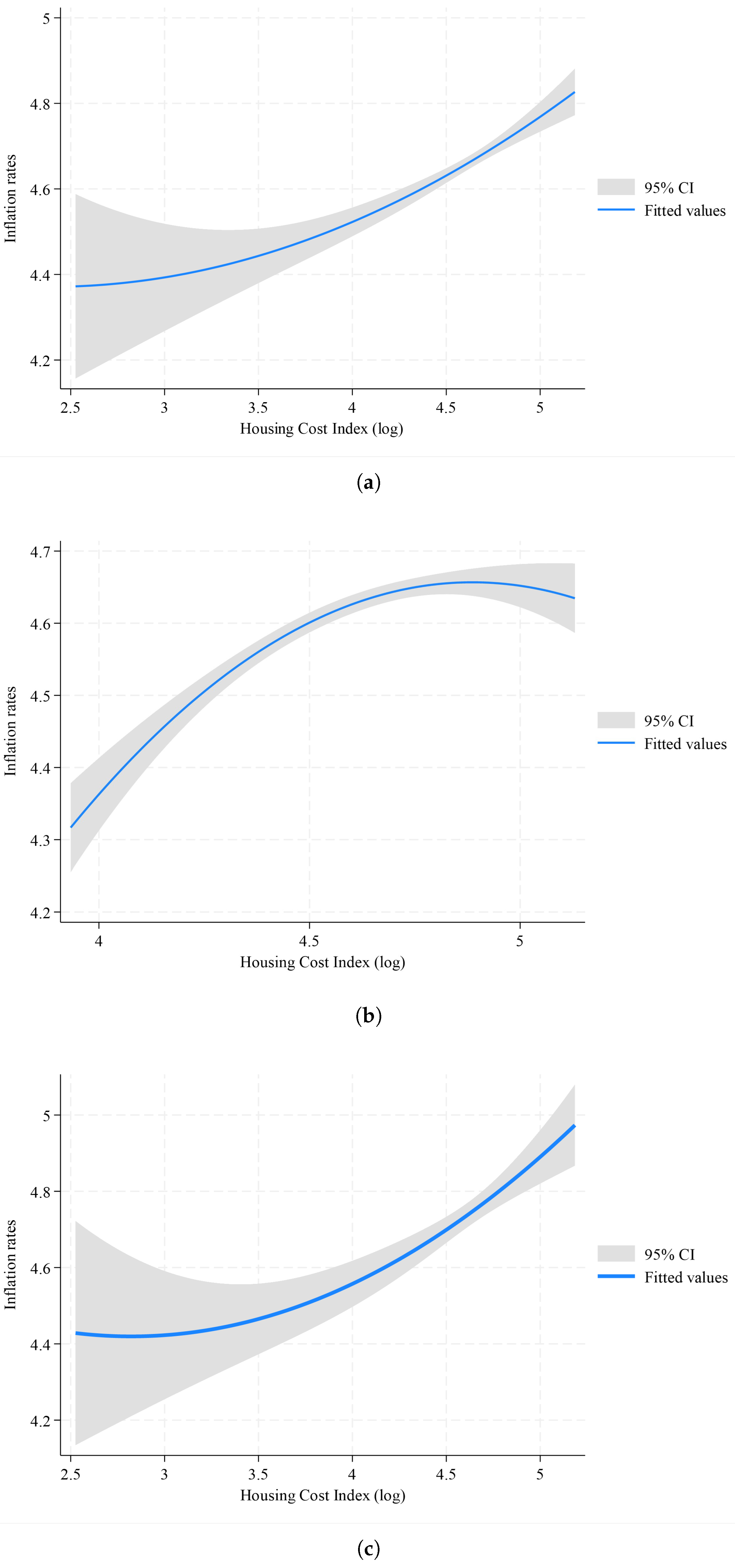

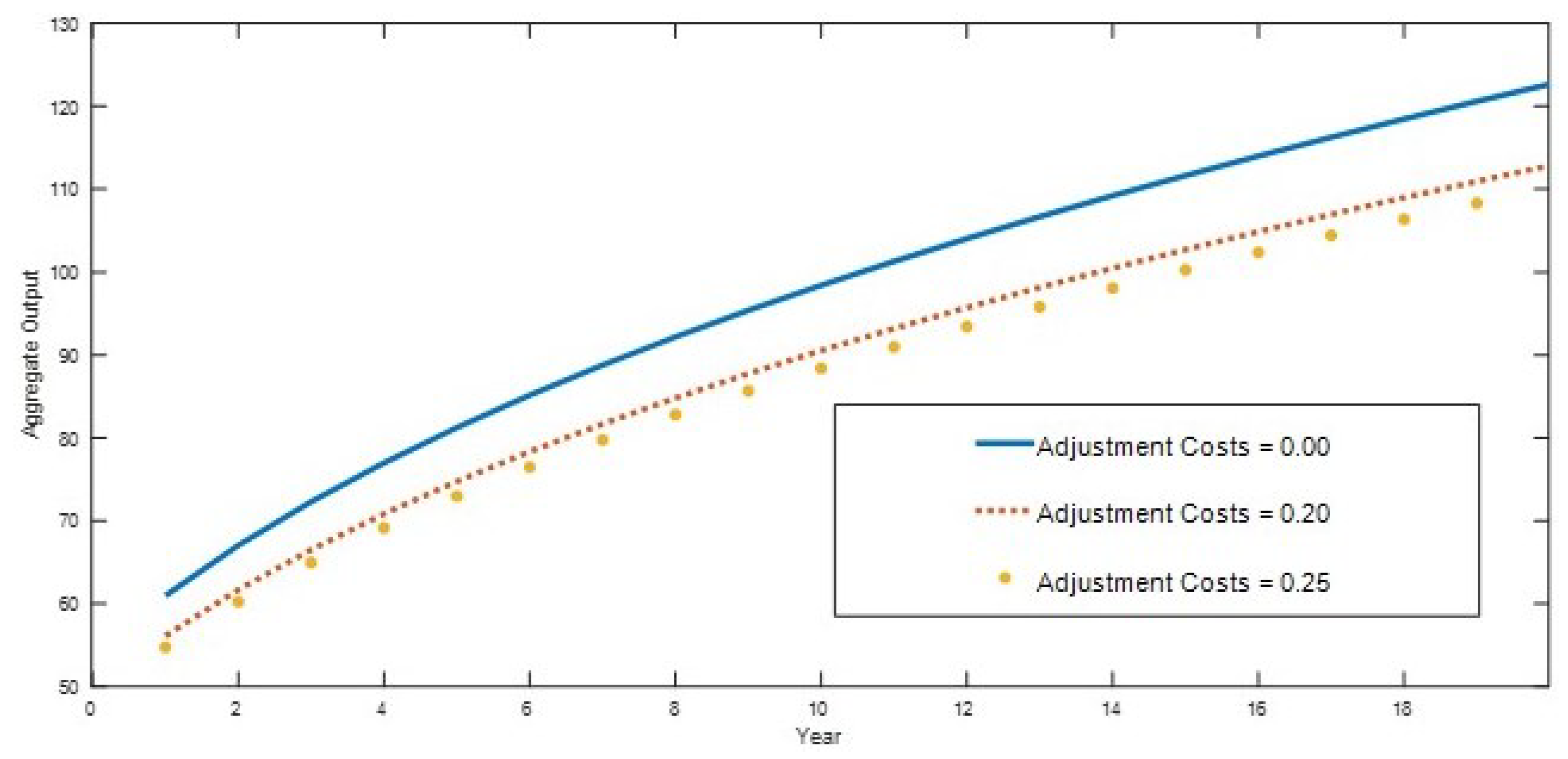

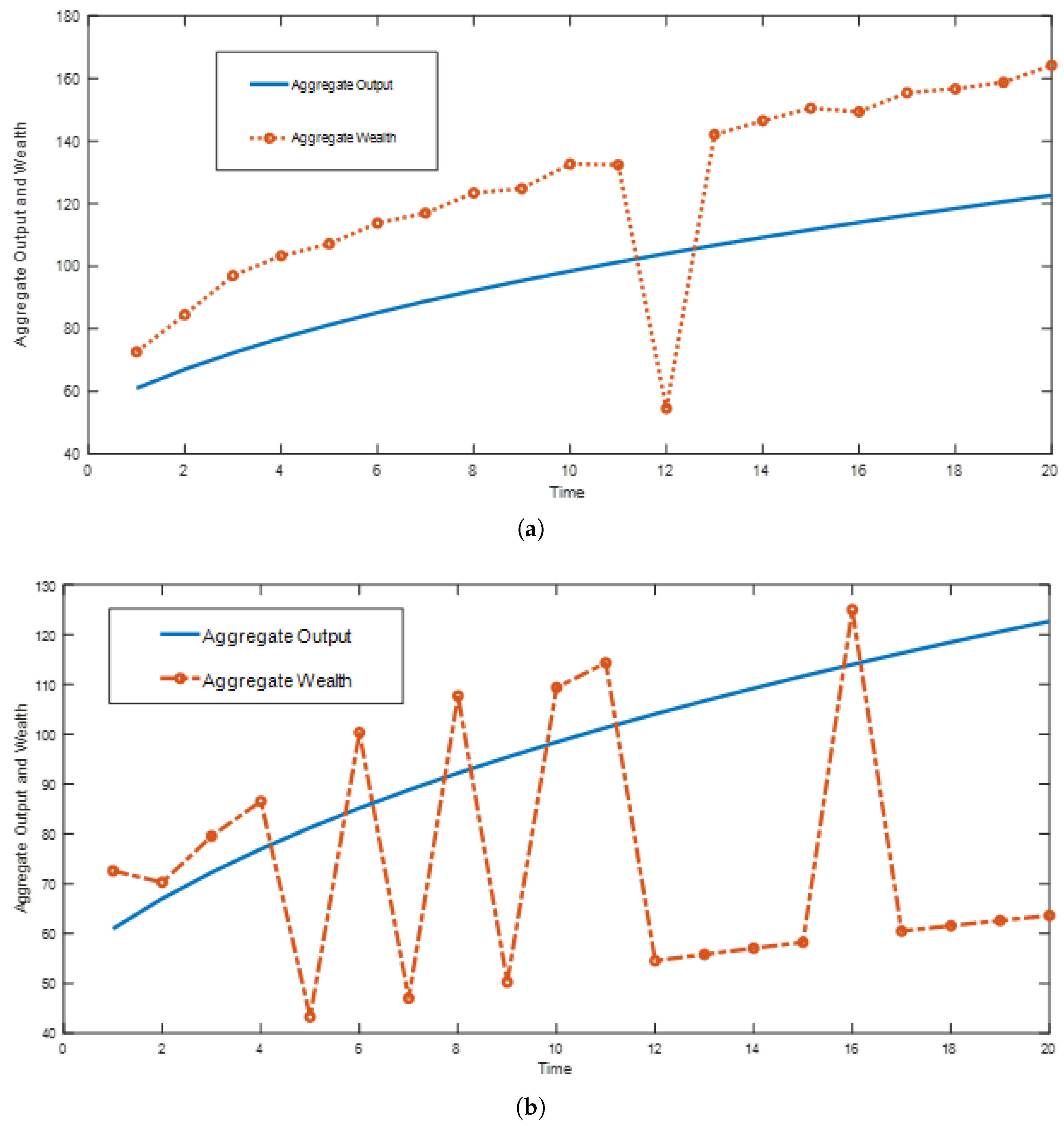

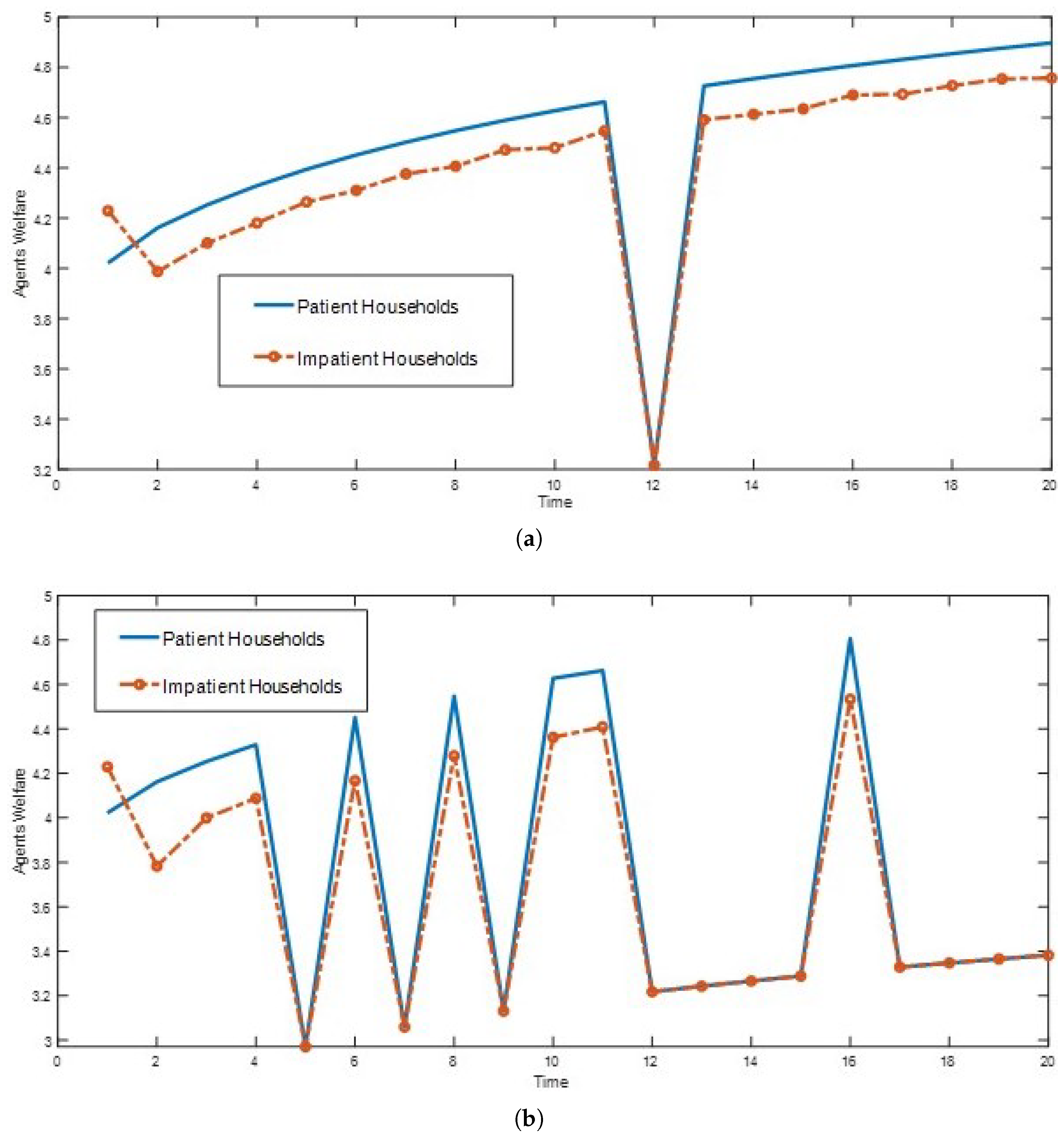

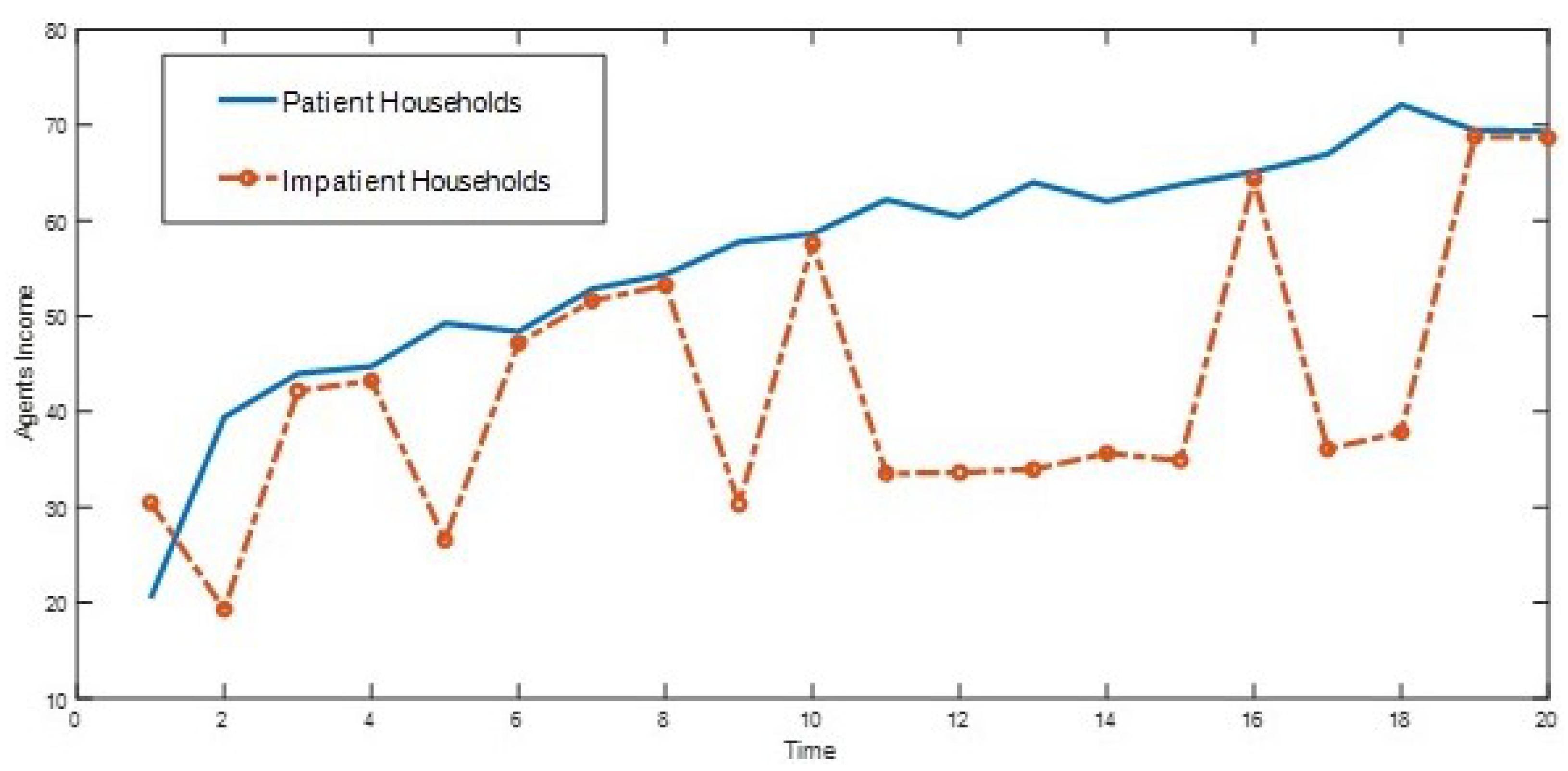

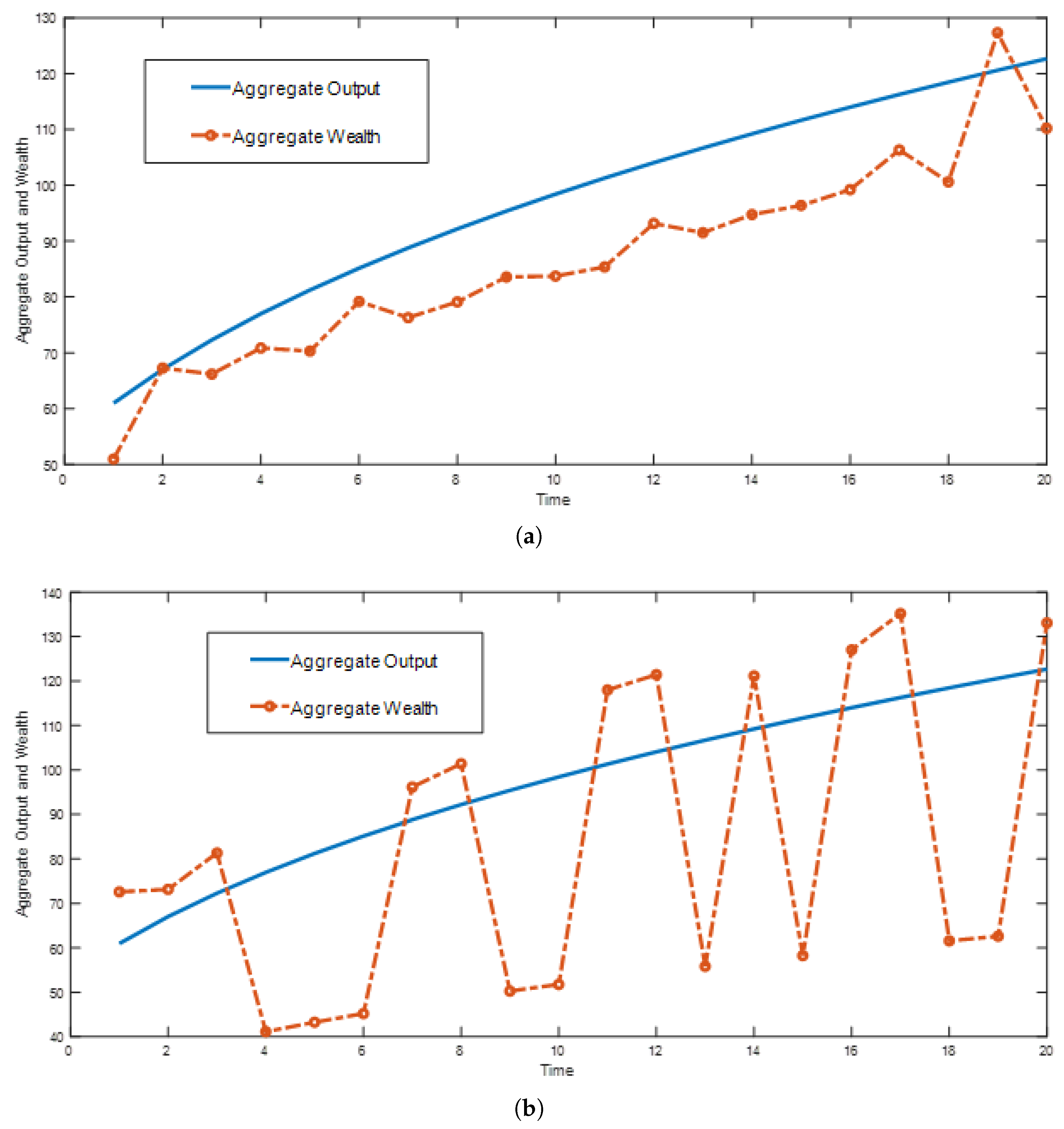

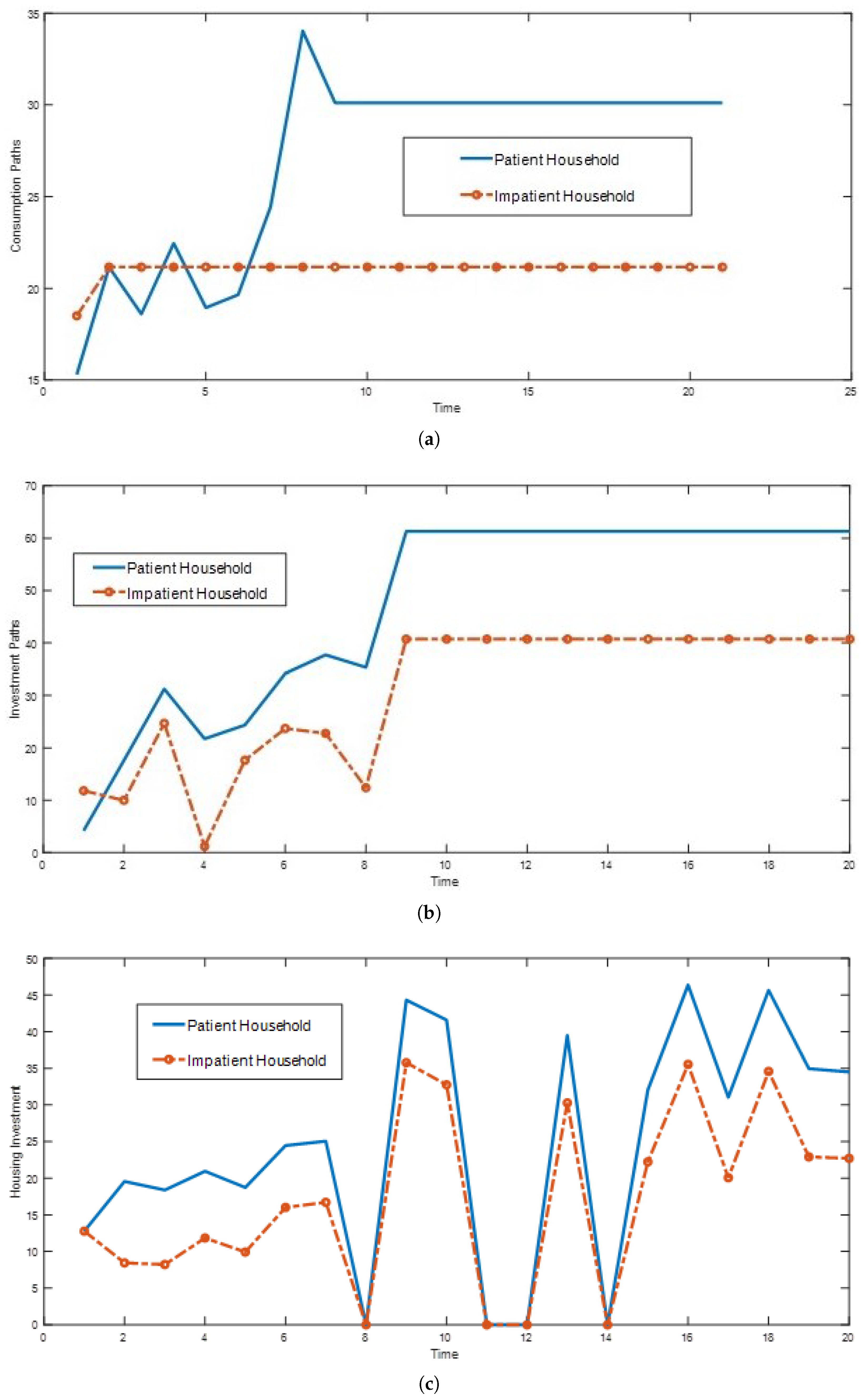

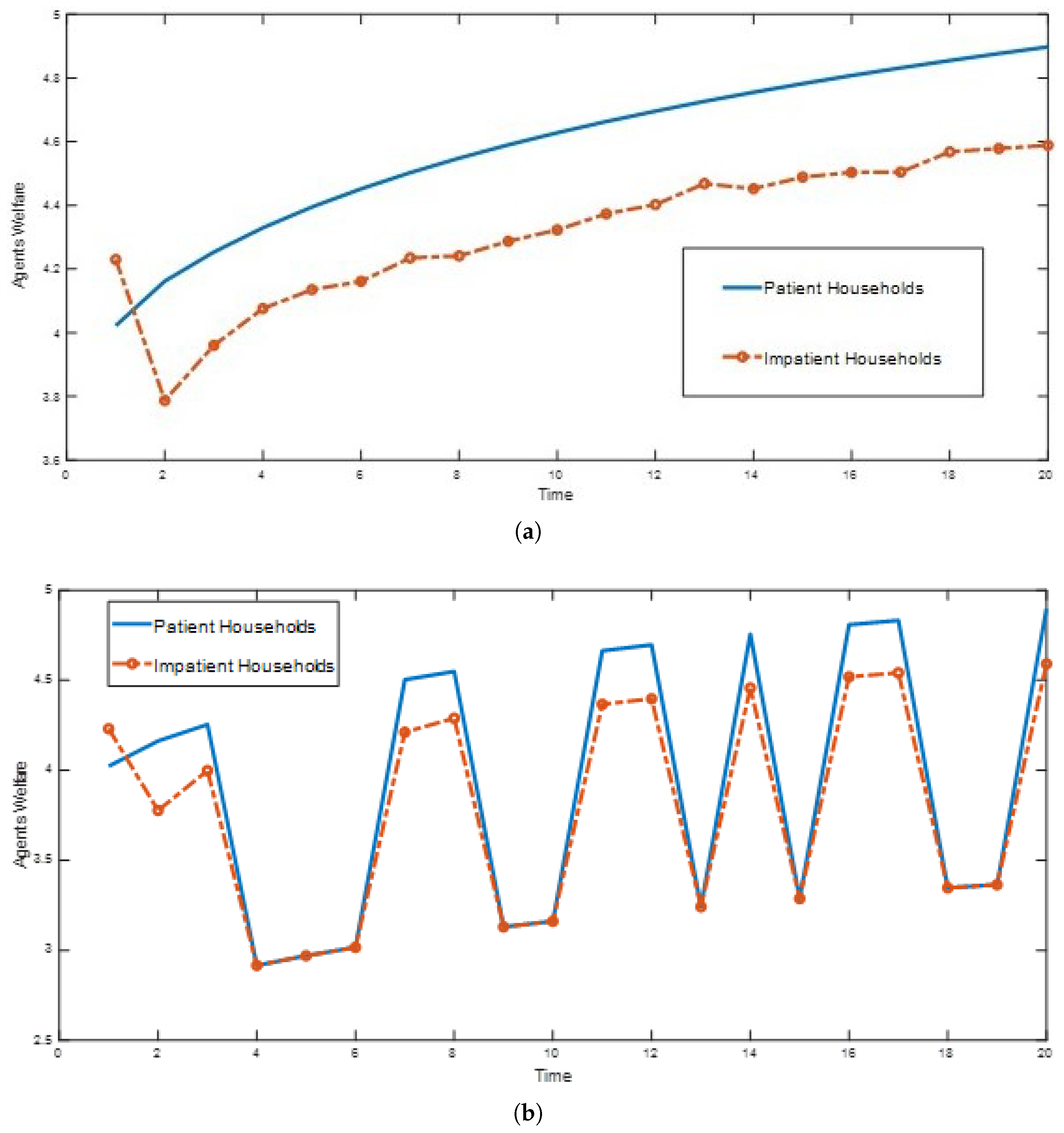

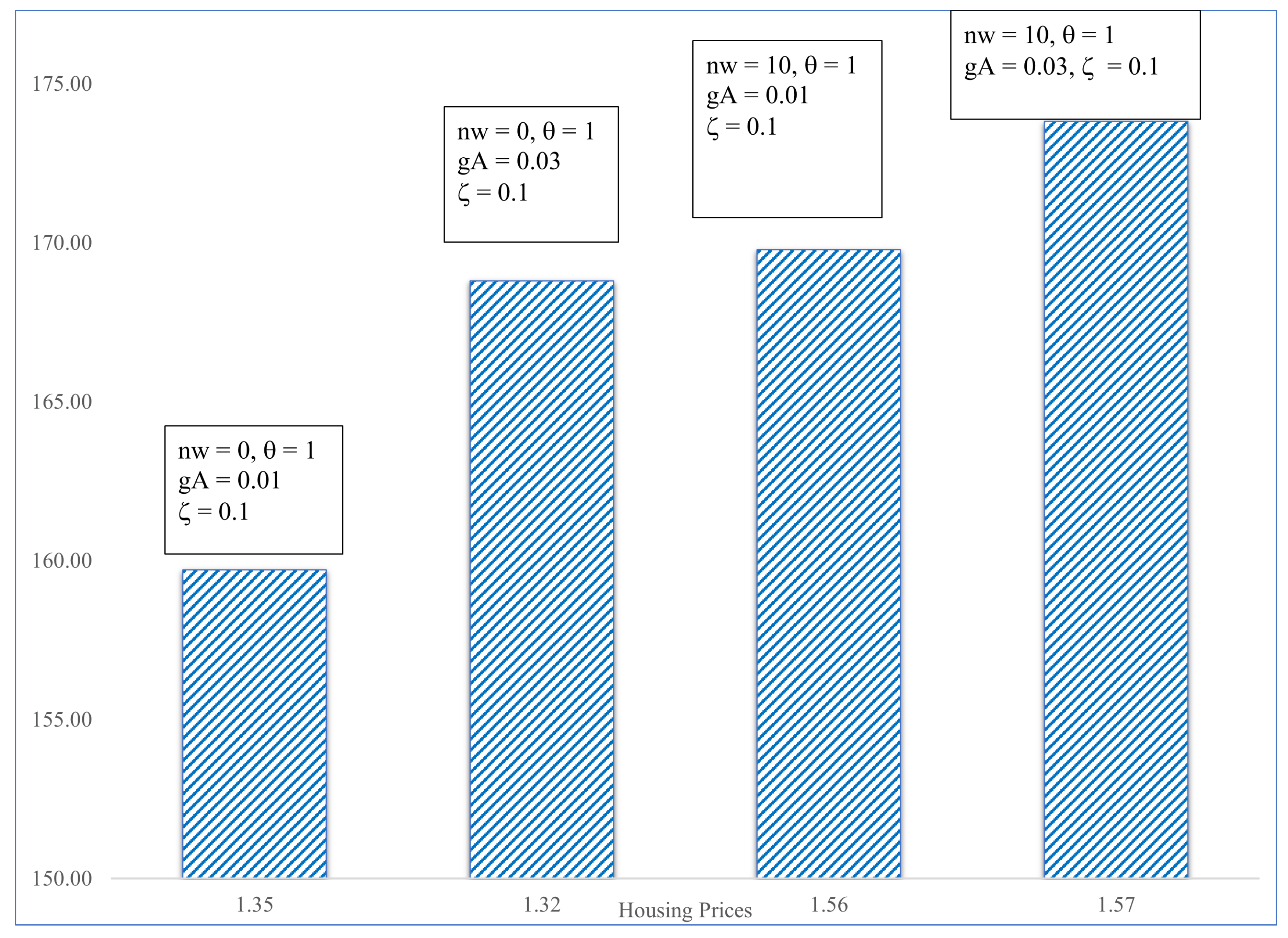

5. Numerical Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Proofs

Appendix A.1. The Phillips Curve

- (1)

- , then , which implies , for all t and i = 1...n. This implies that prices are constant in the steady state.

- (2)

- With constant prices, we have the following:

Appendix A.2. Rental Capital

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- ;

- (iii)

- .

Appendix A.3. Interest Rates

| Developed Countries | |||

| Deficit | Population | Financing | |

| (Millions) | (%) | ||

| Finland | 0.6 | 5.6 | 70 |

| Germany | 0.7 | 83.3 | 90 |

| Greece | 0.2 | 10.4 | 70–75 |

| Portugal | 0.1 | 10.9 | 60–70 |

| United Kingdom | 4.3 | 68.4 | 80–95 |

| Developing Countries | |||

| Deficit | Population | Financing | |

| (Millions) | (%) | ||

| Argentina | 4.0 | 46.2 | 50–70 |

| Brazil | 5.8 | 215.3 | 80 |

| Chile | 0.6 | 19.6 | 75 |

| Colombia | 5.2 | 51.9 | 70 |

| Mexico | 2.2 | 127.5 | 80–90 |

| India | 47.0 | 1417 | 85 |

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Bank Interest Rate | 946 | 5.7 | 12.3 | 0.0 | 316.0 |

| Credit to GDP (Percentage) | 926 | 107.0 | 69.5 | 8.0 | 288.5 |

| Current Account to GDP (Percentage) | 985 | −0.5 | 5.8 | −30.9 | 28.0 |

| Deposit Interest Rate (Percentage) | 862 | 4.7 | 6.4 | 0.0 | 74.7 |

| Devaluation Rate (Percentage) | 944 | 1.3 | 15.0 | −272.2 | 120.0 |

| Fed Fund Interest Rate (Percentage) | 990 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 5.0 |

| Foreign Reserves (USD Millions) | 986 | 108,160 | 392,610 | 195 | 3,900,000 |

| Gap Between Interest Rates | 946 | 4.3 | 12.3 | −2.2 | 314.3 |

| Household Debt to GDP (Percentage) | 771 | 50.1 | 31.0 | 2.5 | 137.4 |

| Index of Housing Cost (Base Year = 2015) | 667 | 100.7 | 24.3 | 12.5 | 178.5 |

| Inflation Rate (Percentage) | 914 | 4.1 | 5.3 | −3.4 | 93.6 |

| Lending Interest Rate (Percentage) | 830 | 8.9 | 10.5 | 0.0 | 118.4 |

| Money Market Interest Rate (Percentage) | 745 | 4.4 | 6.2 | −0.6 | 86.1 |

| Nominal Exchange Rate (Domestic Currency to USD) | 989 | 536.2 | 1929.4 | 0.5 | 15,731 |

| Nonperforming Loans (Percentage of Debt) | 543 | 4.1 | 5.3 | 0.2 | 45.6 |

| Openness Index 2001–2022 | 940 | 69.7 | 28.7 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Developed Countries | 396 | 87 | 10 | 29 | 100 |

| Developing Countries | 544 | 57 | 32 | 0 | 100 |

| Per Capita GDP (Constant USD of 2015) | 987 | 24,031 | 29,724 | 263 | 288,275 |

| Private debt to GDP (Percentage) | 771 | 80.0 | 40.4 | 12.5 | 185.3 |

| Real GDP growth | 989 | 2.8 | 3.6 | −21.4 | 14.0 |

| Total Factor Productivity (Rate of Growth) | 665 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Unemployment Rate | 871 | 8.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 33.0 |

| U.S. Central bank Rate | 990 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 5.3 |

| VIX | 990 | 20.2 | 6.2 | 11.1 | 31.8 |

| Year | 990 | 2012 | 6 | 2001 | 2022 |

| yit = ai + bXit + vit | ||||||

| (A): All Countries | ||||||

| 2001–2022 | 2001–2014 | 2015–2022 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: D log Credit/GDPi | ||||||

| D log Credit/GDPus | 0.5196 *** | 0.4549 *** | 0.3810 ** | 0.3474 ** | 1.0388 *** | 1.1067 *** |

| (0.1066) | (0.0880) | (0.1427) | (0.1244) | (0.1394) | (0.0927) | |

| D log GDPpc | −0.2445 *** | −0.2677 *** | −0.2963 *** | −0.3221 *** | −0.2145 *** | −0.2044 *** |

| (0.0248) | (0.0257) | (0.0355) | (0.0367) | (0.0309) | (0.0356) | |

| Adj R2 | 11% | 11% | 28% | |||

| Chi2 | 142 | 80 | 314 | |||

| Observations | 881 | 881 | 543 | 543 | 338 | 338 |

| (B): Developed Countries | ||||||

| 2001–2022 | 2001–2014 | 2015–2022 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: D log Credit/GDPi | ||||||

| D log Credit/GDPus | 0.7553 *** | 0.6814 *** | 0.5978 *** | 0.5412 *** | 1.2064 *** | 1.1491 *** |

| (0.0757) | (0.0577) | (0.0826) | (0.0679) | (0.1371) | (0.0909) | |

| D log GDPpc | −0.0793 *** | −0.0732 ** | −0.0922 *** | −0.0839 ** | −0.1164 *** | −0.2652 *** |

| (0.0223) | (0.0236) | (0.0274) | (0.0284) | (0.0344) | (0.0495) | |

| Adj R2 | 21% | 18% | 39% | |||

| Chi2 | 141 | 64 | 260 | |||

| Observations | 377 | 377 | 233 | 233 | 144 | 144 |

| (C): Developing Countries | ||||||

| 2001–2022 | 2001–2014 | 2015–2022 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: D log Credit/GDPi | ||||||

| D log Credit/GDPus | 0.2298 | 0.1773 | 0.0573 | 0.0381 | 0.8373 *** | 1.0595 *** |

| (0.1745) | (0.1468) | (0.2351) | (0.2064) | (0.2214) | (0.1502) | |

| D log GDPpc | −0.3202 *** | −0.3479 *** | −0.3757 *** | −0.4088 *** | −0.2798 *** | −0.1947 *** |

| (0.0361) | (0.0372) | (0.0515) | (0.0533) | (0.0455) | (0.0491) | |

| Adj R2 | 13% | 14% | 27% | |||

| Chi2 | 95 | 59 | 145 | |||

| Observations | 504 | 504 | 310 | 310 | 194 | 194 |

| yit = ai + bXit + vit | ||||||

| (A): All Countries | ||||||

| 2001–2022 | 2001–2014 | 2015–2022 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Household Debt to GDP (log) | ||||||

| Housing Price (log) | 0.6043 *** | 0.6515 *** | 0.6752 *** | 0.6704 *** | 0.0800 | 0.3458 |

| (0.0665) | (0.0724) | (0.0842) | (0.0757) | (0.2804) | (0.2606) | |

| Exchange Rate (log) | −0.0658 *** | −0.0679 *** | −0.0567 *** | −0.0639 *** | −0.0780 *** | −0.0709 *** |

| (0.0091) | (0.0093) | (0.0117) | (0.0119) | (0.0146) | (0.0149) | |

| Openness | 0.9040 *** | 0.8631 *** | 1.0008 *** | 0.9319 *** | 0.7714 *** | 0.7813 *** |

| (0.0849) | (0.0829) | (0.1109) | (0.1068) | (0.1343) | (0.1316) | |

| Unemployment Rate | −0.0210 *** | −0.0070 * | −0.02497792 ** | −0.0062 | −0.0192 ** | −0.0097 * |

| (0.0044) | (0.0030) | (0.0059) | (0.0042) | (0.0071) | (0.0046) | |

| Adj R2 | 38% | 43% | 28% | |||

| Chi2 | 468 | 352 | 103 | |||

| Observations | 612 | 612 | 387 | 387 | 225 | 225 |

| (B): Developed Countries | ||||||

| 2001–2022 | 2001–2014 | 2015–2022 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Household Debt to GDP (log) | ||||||

| Housing Price (log) | 0.2565 ** | 0.2323 ** | 0.2453 * | 0.1408 | 0.2867 | 0.3612 |

| (0.0880) | (0.0875) | (0.1096) | (0.1065) | (0.2647) | (0.2365) | |

| Exchange Rate (log) | 0.0217 | 0.0483 ** | −0.0059 | 0.0478 ** | 0.0478 ** | 0.0666 *** |

| (0.0117) | (0.0154) | (0.0176) | (0.0213) | (0.0174) | (0.0196) | |

| Openness | −0.2246 | −0.3175 | −0.4175 | −0.6568 ** | 0.1617 | 0.1474 |

| (0.1932) | (0.1840) | (0.2566) | (0.2349) | (0.3403) | (0.2704) | |

| Unemployment Rate | −0.0146 ** | −0.0201 *** | −0.0275 ** | 0.0028 | −0.0153 * | −0.0088 ** |

| (0.0047) | (0.0032) | (0.0088) | (0.0044) | (0.0066) | (0.0044) | |

| Adj R2 | 6% | 6% | 12% | |||

| Chi2 | 27 | 12 | 31 | |||

| Observations | 382 | 382 | 216 | 216 | 130 | 130 |

| (C): Developing Countries | ||||||

| 2001–2022 | 2001–2014 | 2015–2022 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Household Debt to GDP (log) | ||||||

| Housing Price (log) | 0.6779 *** | 0.7394 *** | 0.6784 *** | 0.7447 *** | 1.1125 ** | 1.0107 ** |

| (0.0866) | (0.0726) | (0.1025) | (0.0855) | (0.3508) | (0.2902) | |

| Exchange Rate (log) | −0.0458 *** | −0.0273 ** | −0.0390 * | −0.0212 | −0.04316 * | −0.0157 |

| (0.0117) | (0.0094) | (0.0152) | (0.0135) | (0.0178) | (0.0189) | |

| Openness | 0.1514 | 0.3334 *** | 0.4515 ** | 0.5995 *** | −0.3936 * | −0.3095 |

| (0.1055) | (0.0972) | (0.1375) | (0.1209) | (0.1666) | (0.1734) | |

| Unemployment Rate | 0.0077 | 0.0132 ** | 0.0056 | 0.0185 ** | 0.0160 | 0.0152 ** |

| (0.0061) | (0.0043) | (0.0087) | (0.0065) | (0.0090) | (0.0058) | |

| Adj R2 | 25% | 30% | 14% | |||

| Chi2 | 127 | 16 | 12 | |||

| Observations | 230 | 230 | 135 | 135 | 95 | 95 |

| yit = ai + bXit + vit | ||||||

| (A): All Countries | ||||||

| 2001–2022 | 2001–2014 | 2015–2022 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Gap Between Interest Rates | ||||||

| log Ex Ratet | 3.1775 *** | 2.1920 ** | 2.3839 * | 1.9756 * | 5.2248 * | 1.1037 |

| (0.8954) | (0.6925) | (0.9691) | (0.8294) | (2.2642) | (1.8741) | |

| log Ex Ratet+1 | 1.5258 | 0.5224 | 1.6263 | 0.5991 | −0.2961 | −5.4699 |

| (0.8942) | (0.6976) | (0.9619) | (0.8416) | (2.2264) | (1.8079) | |

| Inflationt | 0.7489 *** | 0.7545 *** | 0.7301 *** | 0.7557 *** | 0.7133 *** | 0.6490 *** |

| (0.0592) | (0.0584) | (0.0684) | (0.0720) | (0.1190) | (0.1044) | |

| Inflationt−1 | 0.4448 *** | 0.3807 *** | 0.3921 *** | 0.3551 *** | 0.6151 *** | 0.7657 *** |

| (0.0543) | (0.0520) | (0.0610) | (0.0631) | (0.1134) | (0.1119) | |

| Dummy low growth | 0.8024 ** | 0.5041 | 0.1834 | 0.7383 *** | 1.7388 *** | 0.9995 *** |

| (0.3089) | (0.2775) | (0.3865) | (0.4267) | (0.5083) | (0.3339) | |

| Adj R2 | 54% | 52% | 59% | |||

| Chi2 | 915 | 506 | 623 | |||

| Observations | 802 | 802 | 499 | 499 | 303 | 303 |

| (B): Developed Countries | ||||||

| 2001–2022 | 2001–2014 | 2015–2022 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Gap Between Interest Rates | ||||||

| log Ex Ratet | 0.1917 | 1.3289 | −0.2366 | 0.7776 | 3.0196 ** | 2.9055 ** |

| (0.7861) | (0.8719) | (1.0027) | (1.1313) | (1.0756) | (1.0128) | |

| log Ex Ratet+1 | 2.5259 ** | 2.3153 ** | 2.2381 * | 2.9505 ** | 3.6886 ** | 2.6114 * |

| (0.8307) | (0.9142) | (1.0741) | (1.1300) | (1.2329) | (1.1552) | |

| Inflationt | 0.2314 *** | 0.2194 ** | 0.1890 * | 0.1967 | 0.0508 | 0.1726 * |

| (0.0653) | (0.0766) | (0.0917) | (0.1106) | (0.0893) | (0.0754) | |

| Inflationt−1 | 0.2373 *** | 0.1947 ** | 0.1452 | 0.1278 | −0.1007 | −0.1854 ** |

| (0.0671) | (0.0736) | (0.0940) | (0.1015) | (0.0929) | (0.0790) | |

| Dummy low growth | 0.2088 | 0.0167 | 0.1013 | 0.2621 | 0.0748 | 0.0423 |

| (0.1593) | (0.1594) | (0.2068) | (0.2340) | (0.2115) | (0.1730) | |

| Adj R2 | 12% | 3% | 9% | |||

| Chi2 | 34 | 13 | 26 | |||

| Observations | 342 | 342 | 216 | 216 | 126 | 126 |

| (C): Developing Countries | ||||||

| 2001–2022 | 2001–2014 | 2015–2022 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Gap Between Interest Rates | ||||||

| log Ex Ratet | 3.4332 ** | 2.2067 * | 2.8720 * | 2.2097 * | 4.8284 | 6.7914 * |

| (1.2127) | (0.8998) | (1.2986) | (1.0568) | (3.2854) | (2.7618) | |

| log Ex Ratet+1 | 0.8570 | −0.0293 | 1.0811 | 1.0126 | −1.2860 | −4.5774 |

| (1.1942) | (0.9065) | (1.2766) | (1.0716) | (3.0984) | (3.1582) | |

| Inflationt | 0.7250 *** | 0.7269 *** | 0.7092 *** | 0.6904 *** | 0.6772 *** | 0.5884 *** |

| (0.0785) | (0.0760) | (0.0914) | (0.0946) | (0.1588) | (0.1320) | |

| Inflationt−1 | 0.3588 *** | 0.3265 *** | 0.2912 *** | 0.2987 *** | 0.5662 *** | 0.6210 *** |

| (0.0714) | (0.0676) | (0.0804) | (0.0806) | (0.1526) | (0.1270) | |

| Dummy low growth | 2.3424 *** | 1.3633 ** | 2.2400 ** | 3.4648 *** | 2.3985 ** | 1.7599 * |

| (0.5778) | (0.5122) | (0.8632) | (0.9899) | (0.8135) | (0.6484) | |

| Adj R2 | 46% | 43% | 51% | |||

| Chi2 | 387 | 219 | 241 | |||

| Observations | 460 | 460 | 283 | 283 | 177 | 177 |

| Selected Countries | Observed | Predicted | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bolivia | 2.42 | 2.97 | −0.55 |

| Brazil | 7.24 | 7.28 | −0.04 |

| Chile | 2.48 | 4.10 | −1.62 |

| China | 1.94 | 1.79 | 0.16 |

| Colombia | 3.91 | 4.88 | −0.96 |

| Costa Rica | 2.13 | 1.59 | 0.54 |

| Hungary | 1.12 | 2.22 | −1.09 |

| India | 4.88 | 5.05 | −0.17 |

| Average | 3.27 | 3.73 | −0.47 |

| 1 | Measured through the Housing Price Index of the OECD. |

| 2 | See Table A1. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | See Table A2. |

| 5 | Accordingly, housing wealth accounted for approximately 50 percent of Chinese households’ net worth between 2004 and 2019. |

| 6 | Leading to reversals of capital flows when lending conditions change (Mendoza, 2002; Calvo et al., 2006). |

| 7 | For example, the U.S. economy. |

| 8 | Directly or indirectly, independently of the exchange-rate regime. |

| 9 | Which includes expectations about the future, mortgage rates, house prices, and rental rates. |

| 10 | Provided by housing shares, m. |

| 11 | And the return. |

| 12 | Note that in the absence of the idiosyncratic shock , housing would become a safer investment. |

| 13 | Including collateral for debt, and full or partial financing. |

| 14 | For example, in the case of China (Dong et al., 2021). |

| 15 | Coming from housing shares and bank deposits. |

| 16 | These shares are recurrent housing expenditures. |

| 17 | Given by external conditions, such as natural catastrophes, market conditions, etc., with |

| 18 | See Appendix A online. |

| 19 | Accumulated assets. |

| 20 | We are assuming here that physical capital is homogeneous and is traded under perfect market competition. |

| 21 | Expressed by the demand elasticity and the banks’ shares in the market. |

| 22 | Which depends on the firms’ own capital n, among other aspects. |

| 23 | The degree of market competition would determine the magnitude of this effect. |

| 24 | Given the fixed amount of land. |

| 25 | Interbank real interest rate. |

| 26 | See Appendix A.3. |

| 27 | The idea is to represent extreme cases described in the literature, where the global cycle can lead to excessive credit growth in boom times and excessive contraction in bad times (Rey, 2018). |

| 28 | Based on taxation in good times and a subsidy in adverse times. |

| 29 | Note that the maximum rates reached during the Global Financial Crisis in developing countries were 1.17 and 1.36, respectively. |

References

- Acoling, A., Hoek-Smit, M., & Green, R. (2022). Measuring the housing sector’s contribution to GDP in emerging market countries. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 15(5), 977–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian, T., Natalucci, F., & Qureshi, M. (2023). Macro-financial stability in the COVID-2019 crisis: Some reflections. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 15, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, K., Benigno, G., & Kiyotaki, N. (2018). Monetary and financial policies in emerging markets. Working paper. Princeton University. [Google Scholar]

- Bank for International Settlements (BIS). (2023). Statistics database. Bank for International Settlements. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Mexico. (2024). Economic information system. Bank of Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Baqaee, D., Farhi, E., & Sangani, K. (2024). The supply-side effects of monetary policy. Journal of Political Economy, 132(4), 1065–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beraja, M., Fuster, A., Hurst, E., & Vavra, J. (2019). Regional heterogeneity and the refinancing channel of monetary policy. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(1), 109–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernanke, B., Gertler, M., & Gilchrist, S. (1999). The financial accelerator in a quantitative business cycle framework. In J. B. Taylor, & M. Woodford (Eds.), Handbook of macroeconomics (Vol. I). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, D., & Zhong, M. (2023). Understanding bank and nonbank credit cycles: A structural exploration. Journal of Money Credit and Banking, 55(1), 103–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, V., & Shin, H. S. (2015). Capital flows and the risk-taking channel of monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 71, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, R., & Krishnamurthy, A. (2008). Collective risk management in a flight to quality episode. The Journal of Finance, 63(5), 2195–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, R., & Simsek, A. (2022). Monetary policy with opinionated markets. American Economic Review, 112(7), 2353–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, G. (1983). Staggered prices in a utility-maximizing framework. Journal of Monetary Economics, 12, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, G., Izquierdo, A., & Talvi, E. (2006). Sudden stops and phoenix miracles in emerging markets. American Economic Review, 96(2), 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillo, J., Mendoza, E., Nugher, V., & Roldan Peña, J. (2021). Tight money-tight credit: Coordination failure in the conduct of monetary and financial policies. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 13(3), 37–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casen. (2022). Encuesta caracterización socioeconómica nacional 2020. Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia, Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bank of Argentina. (2024). Statistics database. Central Bank of Argentina. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bank of Brazil. (2024). Statistics database. Central Bank of Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bank of Chile. (2024). Statistics database. Central Bank of Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bank of Colombia. (2024). Statistics database. Central Bank of Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Christiano, L., Ilut, C. L., Motto, R., & Rostagno, M. (2010). Monetary policy and stock market booms. NBER Working Paper 16402. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Christiano, L., Motto, R., & Rostagno, M. (2014). Risk shocks. American Economic Review, 104(1), 27–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarida, R. (2019). The global factor in neutral policy rates: Some implications for exchange rates, monetary policy, and policy coordination. International discussion papers 1244. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J., & Ludvigson, S. C. (2019). Drivers of the great housing boom-bust: Credit conditions, beliefs, or both? NBER working paper No. 25285. National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w25285 (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- DANE. (2024). National administrative department of statistics, colombia. Housing deficits. DANE. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, F., Liu, J., Xu, Z., & Zhao, B. (2021). Flight to housing in China. Journal of Economic Dynamic and Control, 130, 104189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duca, J., Muellbauer, J., & Murphy, A. (2021). What drives house price cycles? International experience and policy issues. Journal of Economic Literature, 59(3), 773–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenbaum, M., Rebelo, S., & Wong, A. (2022). State-Dependent Effects of Monetary Policy: The Refinancing Channel. American Economic Review, 112(3), 721–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gali, J., & Monacelli, T. (2005). Monetary policy and exchange rate volatility in a small open economy. Review of Economic Studies, 72, 707–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geanakoplos, J. (2016). The credit surface and monetary policy. In Progress and confusion: The state of macroeconomic policy (pp. 143–153). International Monetary Fund and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geanakoplos, J., & Wang, H. (2020). Quantitative easing, collateral constraints, and financial spillovers. American Economics Journal: Macroeconomics, 12(4), 180–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, M., Kiyotaki, N., & Pristino, A. (2016). Wholesale banking and bank runs in macroeconomic modelling of financial crises. In J. Taylor, & H. Uhlig (Eds.), Handbook of macroeconomics (1st ed., Vol. 2, pp. 1345–1425). Chapter 16. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Gertler, M., Kiyotaki, N., & Queralto, A. (2012). Financial crises, bank risk exposure and government financial policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 59(Supplement), 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gete, P. (2020). Expectations and the housing boom and bust. An open economy view. Journal of Housing Economics, 49, 101690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoviello, M. (2005). House prices, borrowing constraints, and monetary policy in the business cycle. American Economic Review, 95(3), 739–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoviello, M., & Neri, S. (2010). Housing market spillovers: Evidence from an estimated DSGE model. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2, 125–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilzetzki, E., & Jin, K. (2021). The puzzling change in the international transmission of U.S. macroeconomic policy shocks. Journal on International Economics, 130(C), 103444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMF. (2023). International monetary fund. international finance statistics. IMF. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica. (2024). Population and housing statistics. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica. [Google Scholar]

- Kamara, A., & Koirala, N. (2023). The Dynamic Impacts of Monetary Policy Uncertainty Shocks. Economies, 11(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyotaki, N., & Moore, J. (1997). Credit cycles. Journal of Political Economy, 105(2), 211–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, E. (2002). Credit, Prices and Crashes: Business Cycles with a Sudden Stop. In S. Edwards, & J. Frankel (Eds.), Preventing currency crises in emerging markets. Chapter 7. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mian, A., Sufi, A., & Verner, E. (2017). Household Debt and Business Cycles Worldwide. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(4), 1755–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minsky, H. (1986). Stabilizing an unstable economy. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mordor Intelligence. (2024). Real estate market in india size & share analysis–growth trends & forecasts (2024–2029). Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/real-estate-industry-in-india (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Muellbauer, J. (2024). Housing and macroprudential policy. Economics Series Working Papers 1056. University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, E. C. Y., & Feng, N. (2016). Housing market dynamics in a small open economy: Do external and new shocks matter? Journal of International Money and Finance, 63, 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obstfeld, M., & Rogoff, K. (1995). Exchange rate dynamics redux. Journal of Political Economy, 103(3), 624–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). Statistics dataset. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Pateiro-Rodriguez, C., Martín-Bermúdez, F., Barros-Campello, E., & Pateiro-Lopez, C. (2025). On the weak impact of base money on broad money in the context of unconventional monetary policy: Euro area 2008–2024. Economies, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazzesi, M., & Schneider, M. (2016). Housing and Macroeconomics. In J. Taylor, & H. Uhlig (Eds.), Handbook of Macroeconomics (1st ed., Vol. 2, pp. 1547–1640). Chapter 19. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Quadrini, V. (2020). The impact of industrialized countries’ monetary policy on emerging economies. IMF Economic Review, 68, 550–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey, V. (2016). Macroeconomic Shocks and their Propagation. In J. Taylor, & H. Uhlig (Eds.), Handbook of Macroeconomics (1st ed., Vol. 2, pp. 71–162). Chapter 2. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart, C., Reinhart, V., & Tashiro, T. (2015). Does reserve accumulation crowd out investment? Journal of International Money and Finance, 63, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, H. (2016). International channels of transmission of monetary policy and the Mundellian trilemma. IMF Economic Review, 64(1), 6–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, H. (2018). Dilemma not trilemma: The global financial cycle and monetary policy independency. NBER working paper 21162. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Rotemberg, J. (1982). Monopolistic price adjustment and aggregate output. The Review of Economic Studies, 49(4), 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J. (2021). Can policy tame the credit cycle? IMF Economic Review, 69, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, J. (1980). Asset accumulation and economic activity: Reflections on contemporaneous macroeconomic theory. Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, C. (2010). Monetary theory and policy. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woodford, M. (2003). Interest rates & prices. Foundations of a theory of monetary policy. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2021). Introducing the adequate housing index (AHI). A new approach to estimate the adequate housing deficit within and across emerging economies. Policy Research Working Paper 9830. World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital Share in Final Production | 0.35 | Quadrini (2020) | |

| Capital Share in Housing Production | 0.40 | Assumption | |

| Constant Productivity in Final Production | A | 10 | Assumption |

| Constant Productivity in Housing Production | Z | 10 | Assumption |

| Patient Household Discount Factor | s | 0.97 | Gete (2020) |

| Impatient Household Discount Factor | b | 0.85 | Gete (2020) |

| Housing Preferences in Utility Function | 0.15 | Acoling et al. (2022) | |

| Housing Shares | vs | 0.50 | Assumption |

| Capital Utilization in Final Production | ksh | 0.70 | Data |

| Bank Reserve Ratio | 0.10 | Data | |

| Adjustment Costs | 0.20 | Data | |

| Mean of Housing Shock (Impatient Agent) | b | 0.55 | Data |

| Standard Deviation Housing Shock (Impatient Agent) | b | 0.05 | Data |

| Mean of Default Shock | x | −0.10 | Data |

| Standard Deviation of Default Shock | x | 0.10 | Data |

| Coefficient of Full Liquidity | 1.00 | Assumption |

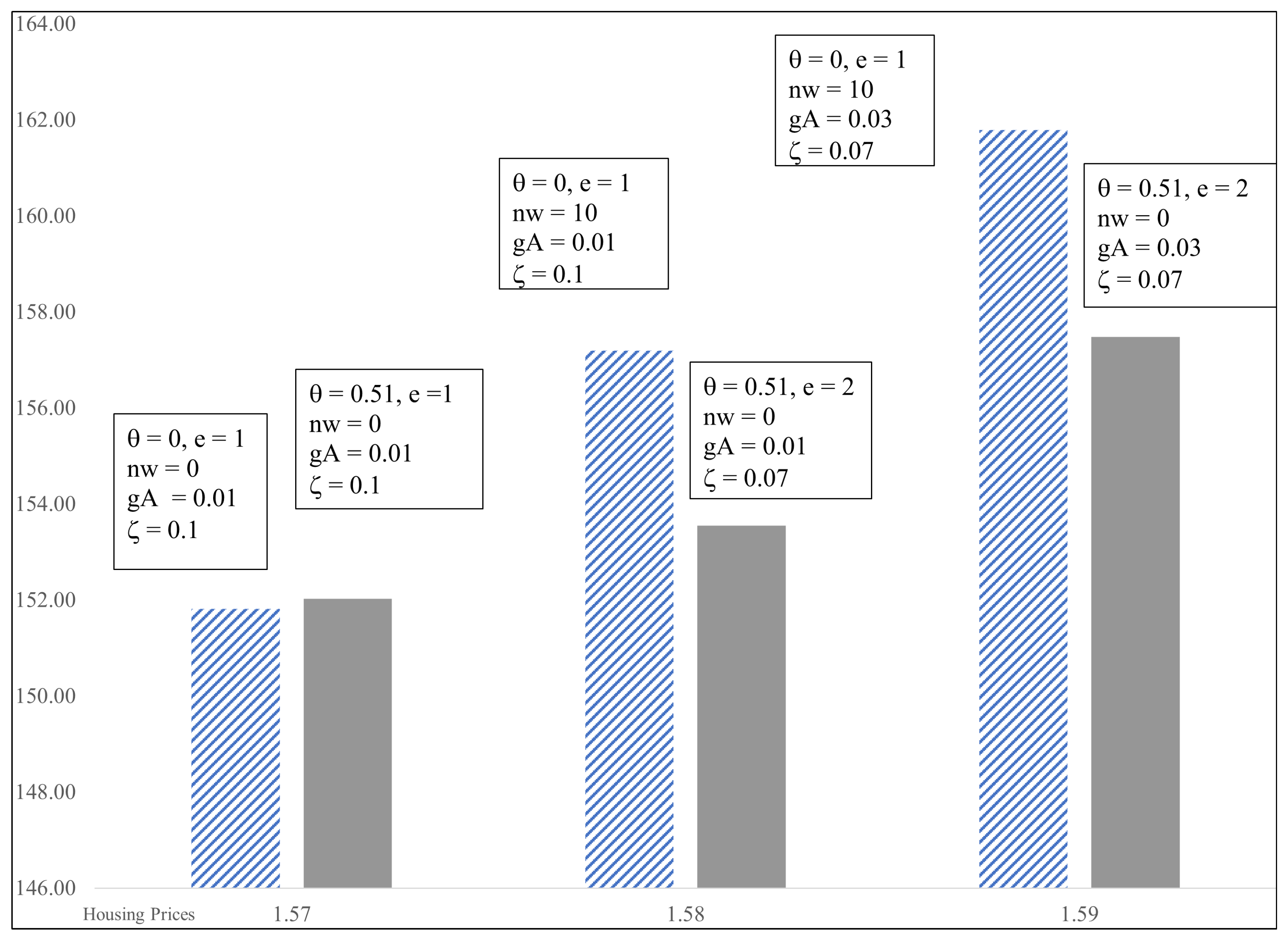

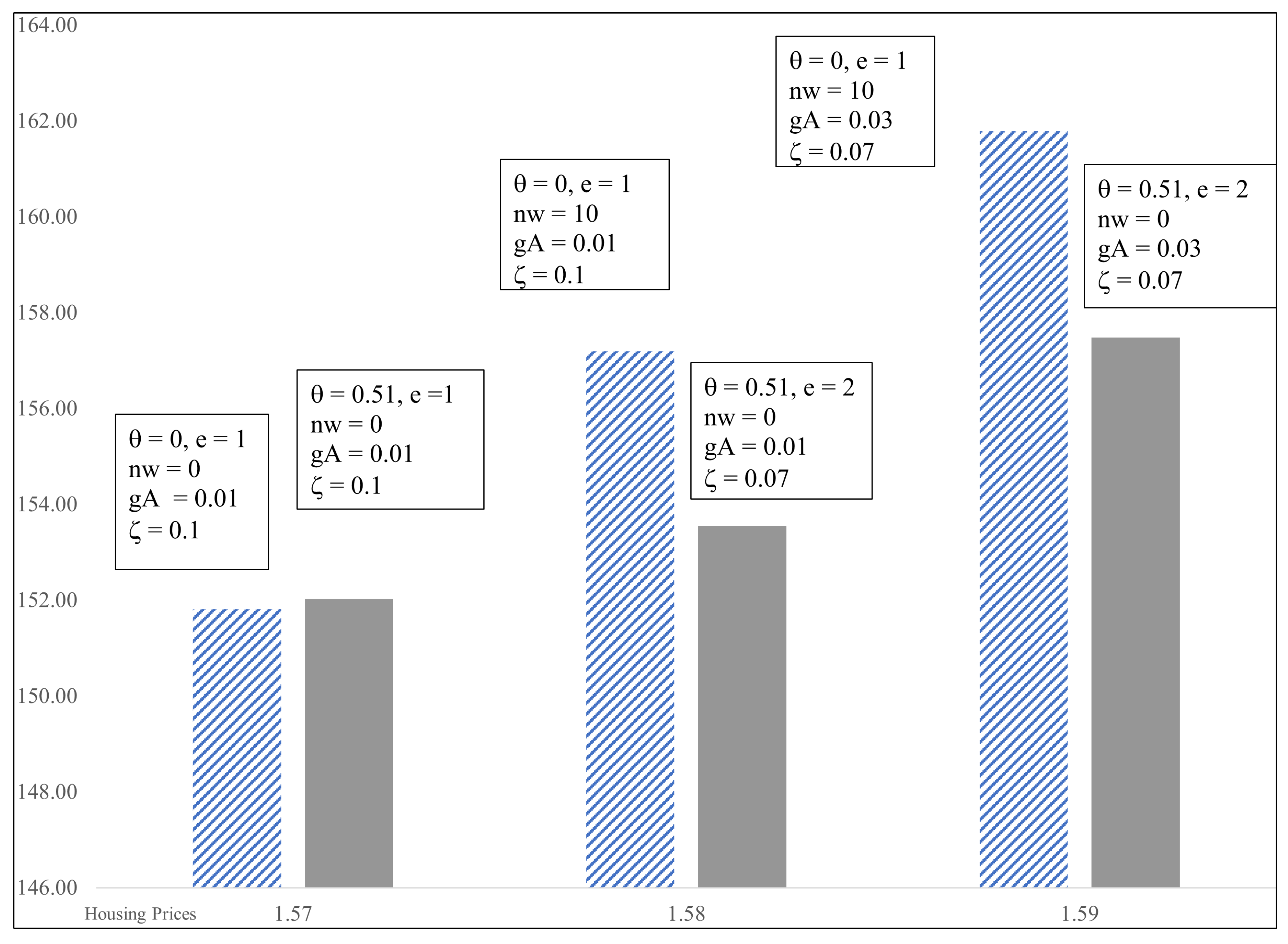

| Interest Rates | Prices | Housing Shocks | Income | Investment | Liquidity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wealth | Deposits | Lending | Housing | Saver | Borrower | Saver | Borrower | Saver | Borrower | Deposits | Credits | |

| Panel A | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| = 1; e = 1; nw = 0; gA = 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 159.71 | 1.02 | 1.13 | 1.35 | 0.88 | 1.23 | 66.63 | 53.63 | 2.95 | 31.30 | 38.10 | 45.29 |

| Std Deviation | 30.26 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 18.39 | 20.43 | 10.98 | 14.85 | 16.33 | 14.69 |

| Rate of Growth | 1.2% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.6% | ||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| = 1; e = 1; nw = 0; gA = 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 168.81 | 1.04 | 1.16 | 1.32 | 0.88 | 1.23 | 53.07 | 62.59 | 0.83 | 31.10 | 20.67 | 29.60 |

| Std Deviation | 48.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 34.73 | 48.68 | 4.72 | 26.07 | 17.80 | 13.38 |

| Rate of Growth | 4.3% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.7% | ||||||||

| Panel B | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| = 1; e = 1; nw = 10; gA = 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 169.78 | 1.02 | 1.14 | 1.56 | 1.11 | 1.23 | 70.90 | 53.39 | 35.46 | 24.33 | 5.64 | 16.08 |

| Std Deviation | 32.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 18.14 | 16.63 | 17.40 | 10.96 | 15.09 | 13.58 |

| Rate of Growth | 1.2% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.8% | ||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| = 1; e = 1; nw = 10; gA = 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 173.82 | 1.01 | 1.13 | 1.57 | 1.11 | 1.23 | 74.66 | 40.77 | 39.45 | 13.60 | 3.12 | 12.81 |

| Std Deviation | 36.78 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 30.39 | 23.22 | 19.73 | 9.19 | 11.77 | 10.59 |

| Rate of Growth | 2.9% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.6% | ||||||||

| Interest Rates | Prices | Housing Shocks | Agents’ Income | Agents’ Investment | Liquidity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wealth | Deposits | Lending | Housing | Saver | Borrower | Saver | Borrower | Saver | Borrower | Deposits | Credits | |

| Panel A | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| = 0.51; e = 1; nw = 0; gA = 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 152.02 | 1.02 | 1.13 | 1.56 | 1.11 | 1.23 | 60.04 | 47.64 | 29.03 | 20.88 | 4.63 | 9.82 |

| Std Deviation | 29.15 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 16.46 | 14.59 | 15.36 | 9.73 | 12.38 | 11.12 |

| Rate of Growth | 1.0% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.7% | ||||||||

| Panel B | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| = 0.51, e = 2; nw = 0; z = 0.07; gA = 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 153.55 | 1.03 | 1.11 | 1.58 | 1.14 | 1.23 | 58.47 | 50.56 | 28.97 | 24.03 | 2.08 | 13.03 |

| Std Deviation | 29.87 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 15.80 | 14.50 | 12.08 | 8.75 | 8.16 | 10.30 |

| Rate of Growth | 1.1% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.5% | ||||||||

| Panel C | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| = 0.51, e = 2; nw = 0; z = 0.07; gA = 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 157.48 | 1.02 | 1.09 | 1.60 | 1.14 | 1.23 | 62.90 | 54.46 | 32.43 | 26.20 | 1.14 | 12.06 |

| Std Deviation | 34.13 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 24.89 | 21.08 | 15.36 | 10.64 | 7.09 | 9.47 |

| Rate of Growth | 1.9% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.5% | ||||||||

| Interest Rates | Prices | Housing Shocks | Agents’ Income | Agents’ Investment | Liquidity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wealth | Deposits | Lending | Housing | Saver | Borrower | Saver | Borrower | Saver | Borrower | Deposits | Credits | |

| Panel A | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| q = 0.51; e = 1; nw = 0; gA = 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 152.02 | 1.02 | 1.13 | 1.56 | 1.11 | 1.23 | 60.04 | 47.64 | 29.03 | 20.88 | 4.63 | 9.82 |

| Std Deviation | 29.15 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 16.46 | 14.59 | 15.36 | 9.73 | 12.38 | 11.12 |

| Rate of Growth | 1.0% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.7% | ||||||||

| Panel B | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| q = 0.51, e = 2; nw = 0; z = 0.07; gA = 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 153.55 | 1.03 | 1.11 | 1.58 | 1.14 | 1.23 | 58.47 | 50.56 | 28.97 | 24.03 | 2.08 | 13.03 |

| Std Deviation | 29.87 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 15.80 | 14.50 | 12.08 | 8.75 | 8.16 | 10.30 |

| Rate of Growth | 1.1% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.5% | ||||||||

| Panel C | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| q = 0.51, e = 2; nw = 0; z = 0.07; gA = 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 157.48 | 1.02 | 1.09 | 1.60 | 1.14 | 1.23 | 62.90 | 54.46 | 32.43 | 26.20 | 1.14 | 12.06 |

| Std Deviation | 34.13 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 24.89 | 21.08 | 15.36 | 10.64 | 7.09 | 9.47 |

| Rate of Growth | 1.9% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.5% | ||||||||

| Interest Rates | Prices | Housing Shocks | Agents’ Income | Agents’ Investment | Liquidity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wealth | Deposits | Lending | Housing | Saver | Borrower | Saver | Borrower | Saver | Borrower | Deposits | Credits | |

| Panel A | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| = 1; e = 1; gA = 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 142.12 | 1.20 | 1.33 | 1.33 | 1.11 | 1.23 | 50.26 | 25.70 | 4.64 | 2.55 | 18.08 | 27.27 |

| Std Deviation | 25.91 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 9.59 | 7.54 | 9.22 | 4.99 | 10.08 | 9.07 |

| Rate of Growth | 0.9% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.5% | ||||||||

| Panel B | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| = 1; e = 1; z = 0.03; gA = 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 144.65 | 1.21 | 1.25 | 1.39 | 1.19 | 1.23 | 50.92 | 28.22 | 9.76 | 5.16 | 12.97 | 23.58 |

| Std Deviation | 27.18 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 9.39 | 9.06 | 11.75 | 6.12 | 11.61 | 11.26 |

| Rate of Growth | 0.9% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.4% | ||||||||

| Panel C | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| = 1, e = 1; z = 0.03; gA = 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 145.72 | 1.19 | 1.23 | 1.41 | 1.19 | 1.23 | 50.71 | 29.31 | 11.53 | 6.18 | 11.21 | 21.87 |

| Std Deviation | 31.21 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 15.15 | 14.53 | 12.49 | 7.23 | 11.67 | 11.32 |

| Rate of Growth | 2.0% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.7% | ||||||||

| Interest Rates | Prices | Housing Shocks | Agents’ Income | Agents’ Investment | Liquidity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wealth | Deposits | Lending | Housing | Saver | Borrower | Saver | Borrower | Saver | Borrower | Deposits | Credits | |

| Panel A | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| q = 0.5; e = 1; gA = 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 142.73 | 1.20 | 1.33 | 1.34 | 1.11 | 1.24 | 50.45 | 26.14 | 5.14 | 2.65 | 17.63 | 21.83 |

| Std Deviation | 26.43 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 10.16 | 7.83 | 9.57 | 4.89 | 10.47 | 9.72 |

| Rate of Growth | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.7% | ||||||||

| Panel B | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d | b | |

| q = 0.54; e = 3; z = 0.03; gA = 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 144.34 | 1.21 | 1.24 | 1.39 | 1.19 | 1.22 | 50.58 | 27.99 | 9.44 | 5.39 | 13.21 | 29.87 |

| Std Deviation | 27.62 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 10.48 | 10.32 | 11.66 | 6.79 | 11.64 | 15.09 |

| Rate of Growth | 1.0% | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.6% | j | |||||||

| Panel C | ||||||||||||

| W | Rd | Rl | S | es | eb | Ws | Wb | ms | mb | d1 | b | |

| q = 0.47, e = 3; z = 0.03; gA = 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 150.18 | 1.20 | 1.24 | 1.39 | 1.19 | 1.23 | 53.11 | 30.66 | 11.32 | 6.43 | 12.35 | 27.19 |

| Std Deviation | 32.92 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 15.12 | 16.13 | 12.89 | 8.16 | 12.28 | 15.71 |

| Rate of Growth | 1.6% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.5% | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farias, M.E.; Godoy, D.R. More or Less Openness? The Credit Cycle, Housing, and Policy. Economies 2025, 13, 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070207

Farias ME, Godoy DR. More or Less Openness? The Credit Cycle, Housing, and Policy. Economies. 2025; 13(7):207. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070207

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarias, Maria Elisa, and David R. Godoy. 2025. "More or Less Openness? The Credit Cycle, Housing, and Policy" Economies 13, no. 7: 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070207

APA StyleFarias, M. E., & Godoy, D. R. (2025). More or Less Openness? The Credit Cycle, Housing, and Policy. Economies, 13(7), 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070207