Abstract

Launched in 2013, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was originally devised to link East Asia and Europe through a network of physical and digital infrastructure. This article analyses the BRI’s development in the European context by offering a comparative analysis of 727 BRI and BRI-like projects within 46 European countries from 2005 to 2021. The analysis considers projects’ location, typology, status, and the main enterprises involved in each project. According to our results, there is a “two-speed Europe”. Indeed, while the vast majority of projects are included in the Digital Silk Road (e.g., telecommunication, transfer technology, data centre, 5G, fintech) and are located in North-Western Europe, traditional investments in infrastructure (e.g., ports, roads, railways, SEZ) are concentrated in South-Eastern Europe and the Balkan countries. While North-Western Europe is particularly concerned about cyber security and data protection issues, various South-Eastern European countries look favorably upon the development opportunities offered by the BRI. The BRI is clearly different from the Western approach to development (based on competition and economic liberalism) and integration (based on treaties). The BRI approach—including its platform, leveraging political flexibility, economic pragmatism, ability to mobilize resources, and ability to create synergies between state and business—could take advantage of the flaws of the European integration process. The BRI, with its strengths as well as weaknesses, represents an opportunity for the EU to understand the need for greater economic and political foresight, social cohesion, and economic flexibility to meet the development needs of its member countries. China, too, can draw inspiration from cooperating with EU countries on how to improve the reception of its investment initiatives by focusing on reciprocity, security guarantees, and protection of rights and the environment.

JEL Classification:

F02; F50; O52; O53

1. Introduction

Global outlooks forecast that developing and emerging markets will grow almost twice as fast as advanced countries and that the global population will increase by 25% by 2040 (GIO, 2018). These profound structural, economic, and demographic changes require greater efforts in terms of investments in order to close the “infrastructure gap” penalizing not only Africa and Asia, but also the most developed countries (GIO, 2018). Bridging the “infrastructure gap” requires implementing an ambitious investment program capable of providing worldwide efficient telecommunications, transport, and primary services networks.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) can be interpreted as one of various responses to this global challenge. Following the footsteps of the historical Silk Road, the BRI was originally devised to link East Asia and Europe through the development of a powerful network of physical and digital infrastructure. Launched in 2013, the original project has evolved over time both in terms of geographical expansion and the variety of connected socio-economic contexts (e.g., the Digital Silk Road (DSR), Green Silk Road, Health Silk Road, and Polar Silk Road, extending also to Africa, Oceania, and Latin America). Various Western-style alternatives have been proposed over time. However, these failed to achieve the BRI success (e.g., the Blue Dot Network), both in terms of countries involved and in terms of infrastructure completed. The Western approach focuses on free market competition as a promoter of economic development and the stipulation of international treaties as a prerequisite for economic integration. The BRI stands out as a cooperation platform, characterized by a pragmatic approach, political flexibility, and soft power. However, its ability to coordinate private companies’ activities with national interests raises concerns about the geopolitical impact of the BRI on US technological and political hegemony and the cyber security of many Western countries involved in the DSR.

With particular reference to the impact of the BRI in Europe, a “two-speed Europe” emerges. On the one hand, North-Western countries are rather sceptical about BRI, but they hosted most DSR projects. On the other hand, various Eastern and Southern European countries have joined the BRI and look favourably upon its investment projects. In this context, EU institutions play an ambiguous role. Indeed, while caring about the cyber security of its member countries, the EU did not offer a resolute community response, leaving the various countries to interface with China autonomously.

The purpose of this article is to provide a detailed mapping of BRI (and BRI-like) projects in Europe (both EU and non-EU countries). BRI-like projects are those that, although lacking an official BRI label, are characteristic of BRI projects and allow a “holistic understanding of global Chinese connectivity projects”, as declared by the IISS China Connects platform,1 which provided the data used in this article. We retrieved detailed information for 727 BRI projects in the European territory: location, typology, year, status of the project (i.e., completed, cancelled, halted, ongoing, or planned), and the main enterprises involved. Results confirm the existence of a “two-speed Europe”, a double Chinese strategy, and the involvement of a small group of powerful Chinese high-tech enterprises in most DSR projects.

2. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Its Evolution: A Review

2.1. The Historical Roots of BRI

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also called the One Belt One Road (OBOR) Initiative, is a strategic project by the People’s Republic of China. The purpose of BRI is to improve China’s trade connections with countries in Eurasia, thus contributing to addressing the global “infrastructure gap”. It draws inspiration from the traditional Silk Road Economic Belt established during the Han Dynasty (which ruled China from 206 BC to 220 AD). Established in 130 BC, the ancient Silk Road was a network of trade routes connecting China, the Far East, and the Middle East up to Europe. The routes extend for more than 6400 km. Although these routes were unsafe and lacked centralized management and protection, they opened a period of flourishing economic and cultural exchanges between West and East through a “relay trade”, in which commodities were exchanged different times before reaching their final destination (Rong, 2022). The Silk Road Economic Belt made it possible to trade commodities such as precious stones and metals, dyes, fruits and vegetables, silk and livestock, leather and hides, or spices, perfumes, and porcelain. Moreover, it promoted the exchange of knowledge (language, religion, philosophy, and science) and the export of inventions such as paper and gunpowder to the West, with China importing honey, wine, gold, and horses. The terrestrial Silk Road had its counterpart in the Maritime Silk Road connecting East Asia, Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian Peninsula, and Eastern Africa up to Europe by sea. Following the rise of the Mongol Empire and the establishment of the Pax Mongolica, which made the routes safer, the Silk Road experienced a period of great development, becoming an important route of communication as well as trade between East and West. The Ottoman Empire terminated the Silk Road in 1453, thus interrupting East–West connections.

2.2. Goals, Features, and Evolution of the BRI

The BRI aims to promote cooperation and integration among Eurasian countries by establishing advantageous relationships for all partners (win-win relationships). The BRI is part of China’s “grand strategy” to boost its influence and leadership in the international arena (Wang, 2016) through soft power and political and economic activism. Chinese president Xi Jinping announced the BRI in September 2013 at Nazarbayev University in Astana (Kazakhstan). In October of the same year, the maritime route (the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road) and the intent to establish the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) were announced. The aim of AIIB is to involve a great number of countries in raising the necessary funds for investments in railway and port infrastructures. Along with China, which holds the largest number of shares, other important participants include India, Russia, Germany, Republic of Korea, and Australia. Moreover, China created the Silk Road Fund in 2014 to promote direct investments capable of financing projects that go beyond logistics. The main economic advantages coming to China from the BRI are the expansion of its exports, the promotion of its currency (Renminbi) as an international currency, and the reduction of transportation costs, tariffs, and frictions in trade (China Power, 2017). BRI was also a profitable opportunity for China to use its foreign exchange reserves through lending and solving China’s “product glut” of basic materials such as cement and steel to be used in the construction of infrastructure (Zhang, 2024).

The BRI aims to develop and enhance transportation and logistics infrastructure to promote the commercial expansion of Chinese manufacturing and services along the OBOR routes. The goal is to connect Asia and Europe along five routes, the first three via land, the last two via sea. The first one should link China, Central Asia, Russia, and Europe. The second one should connect China, Central Asia, and the Middle East. The third route should connect China with Southeast and South Asia and the Indian Ocean. The fourth and the fifth routes are part of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road and link China with Europe (through the South China Sea and Indian Ocean) and with the South Pacific Ocean (through the South China Sea). Infrastructural and commercial initiatives aim to create different “economic co-operation corridors”: the New Eurasia Land Bridge, China–Mongolia–Russia, China–Central Asia–West Asia, China–Indochina Peninsula, China–Pakistan, and Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar.2 BRI has also expanded to Africa, Oceania, and Latin America.

In Europe, the BRI aims to create direct trade links with Spain and Germany through railway and motorway connections. The BRI Maritime Route runs along Eastern and Southern Asia and reaches the Mediterranean and its strategic ports (Piraeus in Greece, Trieste and Palermo in Italy) through the Suez Canal. In Northern Europe, the port of Hamburg in Germany plays a key role.

In 2023, China released a white paper titled ‘The Belt and Road Initiative: A Key Pillar of the Global Community of Shared Future’, with the aim of giving “the international community a better understanding of the value of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), facilitate high-quality cooperation under it, and ultimately deliver benefits to more countries and peoples”.3 The white paper summarizes BRI achievements in the last decade. China has signed more than 200 BRI cooperation agreements involving 30 international organizations and more than 150 countries.4 In 2024, 80% of the United Nations’ 193 member countries have joined BRI (Casarini, 2024), although North America, Brazil, Paraguay, various Western–Northern European countries, Russia, North Korea, Australia, Japan, and India are the most important countries that have not officially signed up.

Along with the progress in the construction of the six infrastructural economic corridors, the Mombasa–Nairobi Railway and the Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway have been completed. The China–Europe Railway Express has reached more than 200 cities, crossing 25 European countries. The Maritime Silk Road network reached 117 ports in 43 countries. BRI also opened direct flight routes with 57 partner countries. Along with building infrastructure, the BRI promoted industrial and financial cooperation, poverty reduction, and employment growth, together with scientific and technological cooperation among scientists, technicians, researchers, and technology transfer platforms.5

The BRI has gone beyond simply building infrastructure since the beginning to improve land, sea, and air connectivity. It has expanded both in terms of geographical coverage and variety of socio-economic contexts. The BRI was originally devised to link East Asia and Europe, but in time it also extended to Africa, Oceania, and Latin America. The BRI now also encompasses the Green Silk Road, the Health Silk Road, the Polar Silk Road, and the Digital Silk Road (DSR). In 2015, a Green Silk Road Fund was established and supported by Chinese private entrepreneurs to finance more green BRI projects (e.g., solar power projects). The Health Silk Road (HSR) emerged in 2015 with the purpose of improving healthcare infrastructure to “enhance public health and foster international cooperation in the healthcare sector” (Yuan, 2023, p. 333). Chinese HSR strategy has been successful during the Ebola 2014–2016 outbreak in West Africa; during the COVID-19 pandemic, China provided masks, ventilators, and testing kits to various countries and vaccines, especially to developing ones (Yuan, 2023). The Polar Silk Road (PSR) was announced in the white paper titled ‘China’s Arctic Policy’ in January 2018 to “facilitate connectivity and sustainable economic and social development of the Arctic” (Tillman et al., 2018, p. 346)6 and promote the development of Arctic Sea routes that can connect China with Europe via the Arctic Ocean. PSR involves Russia and the Nordic countries in the development of a vast, technologically advanced telecommunications network. In 2015, China strengthened its partnership with Russia for the improvement of satellite navigation, particularly of the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System (BDS).7 China started collaborations with Russia, Finland, Japan, and Norway for the construction of a vast fibre-optic maritime cable link across the Arctic Circle (Tillman et al., 2018). In 2012, China began cooperating with Iceland for the exploitation of geothermal energy (Tillman et al., 2018). However, the growing geopolitical tensions and security concerns have slowed down many of these initiatives in recent years (Edstrøm et al., 2025).

The technological content of the BRI is well encapsulated in the DSR. The DSR is a relevant component of the BRI. It aims to expand Chinese digital technologies in developed and developing countries by helping Chinese tech companies to penetrate foreign markets and foster Chinese technological development. It promotes the export and development of e-commerce, AI, 5G fibre optic cables, and data centres. In 2015, China released a white paper about the need for “an Information Silk Road”, aimed at improving international communications connectivity through more powerful communication line networks and cross-border optical cables. Although “digital infrastructure projects were already underway since the early 2010s, the white paper was the earliest articulation of the branding for the DSR” (Reddy, 2023). The geopolitical role of the DSR and the importance of digital soft power are undeniable: although the US held the world leadership for the control of submarine cables, according to the ‘MIIT Made in China 2025 Key Technology Roadmap’, China aims to capture 60% of the international market through domestic fibre optic communication equipment by 2025 (USCBC, 2015). Almost all global internet traffic passes through submarine cables, while less than 5% passes through satellites. These cables are therefore the true political-economic connectors between countries in the modern era, because they allow the exchange of economic, military, health, and private data. The Chinese PEACE Cable Project (Pakistan and East Africa Connecting Europe), led by Huawei, has certainly been the most ambitious in this context, because it connects South Asia, East Africa, and Europe through a network of submarine cables. Although PEACE is privately owned, there is no doubt about the geostrategic relevance of this project and its consistency with Chinese national objectives (Burton, 2020). Another context in which China aims to develop technological autonomy from US hegemony concerns cross-border payment infrastructure. Chinese Fintech companies and their online payment platforms, such as Tencent’s WeChat Pay and Alibaba’s Alipay, compete with the dominant US-led system SWIFT and are developing and expanding within the DSR framework (Ghiasy & Krishnamurthy, 2020). DSR has achieved vast expansion in both Europe and South Asia in terms of both telecommunication networks and payment systems. DSR’s development in Southeast Asia has been favoured by various institutionalization mechanisms and channels, such as the organization of DSR-related events and technology training sessions (Zheng, 2024). In 2019, China launched the ‘Belt and Road International Cooperation Initiative on Digital Economy’ together with Egypt, Laos, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, Thailand, Türkiye, and the United Arab Emirates, and signed 85 standardization cooperation agreements with 49 countries in the DSR context (Ghiasy & Krishnamurthy, 2020).

The DSR has recently become a BRI key pillar due to the predominant participation of Chinese private tech companies (Zheng, 2024) and a strong penetration in Western countries. The BRI has strategically evolved over the last decade, partly changing its objectives and methods of intervention. Factors internal to the Chinese economy, such as the difficulty of various developing countries in repaying their debts to China and the poor profitability of some large BRI projects8, have led Beijing to rethink the BRI approach, placing greater focus on small, smart, and environmental-friendly9 projects with high digital content and protected by anti-corruption and clean governance rules (the so-called Clean Silk Road10). Indeed, various BRI projects provided opportunities for new forms of corruption that have generated little development and little benefit for China itself (e.g., the corruption scandal connected to the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor—CPEC). In general, the amount of financing available and destined to BRI projects has tapered off in favour of projects with more socio-political content (Hawkins, 2023). However, China will continue to support big infrastructure projects that may be relevant, according to geopolitical and long-run perspectives, especially in countries such as Indonesia, Laos, and Vietnam (Zhang, 2024).

In 2023, 10 years after its launch, a report of the Boston University Global Development Policy Center found that “the BRI has delivered significant benefits to the countries that China has engaged with, but has also accentuated real risks for China and host countries alike” (Gallagher et al., 2023, p. 5). Among the benefits are enormous resources that China’s development finance institutions (DFIs) have contributed to the Global South (at least USD 331 billion from 2013 to 2021, including USD 91 billion allocated to Africa) and the promotion of a new model of South–South cooperation with southern-led institutions. BRI also prompted economic growth since “Chinese finance is […] more associated with economic growth, addressing infrastructure bottlenecks and increased energy access than World Bank lending” (Gallagher et al., 2023, p. 5). On the other hand, the most important risks associated with BRI refer to debt distress and environmental issues.

2.3. Western Alternatives to the BRI

The BRI has not been welcomed with enthusiasm by several countries outside the Eurasian context or under its political influence. The US–China trade conflict that began in 2017 has somehow changed the Western political attitude towards BRI, which became a sort of “road to a new global order” (Zhang, 2024). Various countries see BRI as a China-centric program aimed at improving the political and economic power of China. The idea of BRI as a global infrastructural development program raised two main concerns: the quality, transparency, and environmental sustainability of infrastructure projects; and the problem of debt sustainability (Hansbrough, 2020). This latter concern considers in particular the risk of debt distress in some borrower countries that would have China as the main creditor (Hurley et al., 2019; Horn et al., 2013). China had to bail out 22 developing countries between 2008 and 2021 as a consequence of their difficulty in repaying loans spent on building BRI infrastructure.

As a consequence, the US, Australia (Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade—DFAT), and Japan (Japan Bank for International Cooperation—JBIC) created the Blue Dot Network (BDN) in 2019 as an alternative to the BRI. The BDN is a multilateral organization oriented to the private sector but supported by governments, aiming to provide an international certification framework for infrastructure projects.11 BDN is consistent with Western liberal and market-based orientation in that it aims to provide investors with information signals regarding projects worthy of financing on the basis of their non-exploitative nature and coherence with the social, economic, and environmental objectives encapsulated in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The BDN would essentially “frame BRI projects as sub-standard” (Ashbee, 2021, p. 133). However, the BDN is a certification system that does not provide any funding for reducing the global infrastructure gap (Hansbrough, 2020); it does not even provide for planning infrastructure projects that remain in the hands of uncoordinated private initiatives. Despite having the BDN been relaunched in June 2021 under the auspices of the OECD, “the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ forms of economic power upon which it rests constitute an unstable amalgam that is likely to constrain the BDN’s capacities and prospects” (Ashbee, 2021, p. 133).

In June 2021, the G7 proposed the ‘Build Back Better World initiative’ (B3W) as an alternative to the BRI with the aim of providing infrastructure development in various developing countries. Following various difficulties, this US-led G7 project was re-launched as the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII). This initiative builds on the principles and structure of the BDN and aims to encourage private sector investments in those developing countries that most need infrastructure development. In December 2021, the EU Global Gateway was launched as a complementary Western alternative to BRI, more oriented to leverage EU economic and political power.

2.4. BRI and Its Geopolitical Implications and Challenges

The BRI is called upon to address various challenges related above all to its geopolitical impact, along with economic issues. As mentioned above, problems emerge in various developing countries in relation to the difficulties of managing debt from BRI projects. Some fear that China is laying a debt trap for borrowing countries participating in the BRI, with the purpose of forcing borrowing countries to relinquish some of their strategic assets to decrease their debt burdens (the so-called debt-trap diplomacy, see Himmer and Rod (2022)). These fears originate mostly within Western countries, which see the BRI as a neocolonial and imperialistic strategy targeted at the Global South, in spite of the Global South perspective being more nuanced towards China (Degli Esposti, 2025).

Along with strategic issues, corruption and different inefficiencies make various BRI projects unprofitable. In other cases, DSR projects provoke opposition from domestic tech companies. In Western countries, problems related to the BRI mainly revolve around burning geopolitical and national security issues. Indeed, US–China technological rivalry fosters the risks of tech bifurcation (Zheng, 2024) and a progressive polarization between East and West. The US, in particular, fears that the BRI, and even more so the DSR, may become a sort of Trojan horse for a China-led economic and military expansion. Clearly and compared to other infrastructure projects, the DSR not only impacts the flow of trade but also involves delicate geopolitical, security, and military issues that risk going beyond the goal of bridging the infrastructure gap. The US has taken this risk very seriously, and in 2019, the Trump Administration opposed the direct connection between the US and Hong Kong through the Pacific Light Cable Network. The Biden Administration has made these fears its own. In 2022, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ruled that Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE will no longer be authorized to import and sell their products in the US, as the new 5G networks are exposed to the risk of cyber espionage. Other Chinese companies entered the US blacklist, such as Dahua, Hikvision (providing video surveillance tools), and Hytera. The ban had significant economic implications for many small US businesses forced to replace Chinese surveillance-sensitive technologies with more expensive alternatives.

The BRI projects’ nature is extraneous to the way of conceiving economic integration and development in the Western context. As commented by Yu (2018, p. 234): “BRI is very much in line with the distinctive Chinese character of past grand initiatives. That is fluid in nature, opaque in implementation plan and flexible in concrete measures of projects”. Among Western countries, integration is based on international treaties. These treaties define participants, the principles, legal bases, and methods with which to implement economic integration. On the contrary, the legal basis of BRI is political, not normative; BRI is a flexible, open, and inclusive cooperation platform, characterized by a pragmatic approach and political flexibility (Bonelli, 2017). In addition to this, while in the West the dominant idea of economic development is based on economic liberalism with competition and free markets, in the Chinese context, private companies and the government collaborate to pursue national interests through an “ever-changing complex bureaucratic decision-making process” (Yu, 2018, p. 234). The Huawei case is emblematic in this sense. The Chinese approach promotes the development of projects and infrastructures unthinkable in the modern Western context, as shown by the limited success of BDN. Through the BRI, China has broken away from the Western aid practices for developing countries. China has often embarked on potentially unprofitable projects in very disadvantaged countries with the intention of pursuing long-term economic and strategic objectives. Despite poor short-term profitability, China found alternative development solutions by leveraging its strong coordination capacity and rapid mobilization of resources even in difficult contexts. For example, the Chinese government has helped some poor African countries to pay Huawei for the construction of telecommunication networks by facilitating the export of raw materials to China: “this kind of all-encompassing coordination would be unthinkable in the West” (Zhang, 2024). China’s answer to the problem of excessive indebtedness in some BRI countries is extending the repayment period or lowering the interest rate, in clear contrast with the Western “haircut approach” to restructuring the debt of African countries (Zhang, 2024). Obviously, this approach is not without shadows, linked to the tendency to overlook corruption, socio-political issues, the protection of human rights, and to exercise soft power towards the most vulnerable countries.

2.5. BRI and the EU: Potentials, Concerns, and the Two-Speed Europe

Initially, the BRI was looked at with great optimism in the EU as a tool able to foster Sino-European connectivity, with the EU being the endpoint of both land and maritime BRI routes (Casarini, 2024). China, sharing the same vision of Europe as the western terminus of the BRI (Skala-Kuhmann, 2019), concentrated on infrastructure projects such as railways (in Southeast Europe) and ports (in the Mediterranean) (Casarini, 2016). The enthusiasm for the BRI can be traced back to the time of fruitful political and commercial relations between China and Europe, particularly in the 2000s. In 2013, the EU and China approved the ‘EU-China 2020 Strategic Agenda for Cooperation’. In 2015, the European Commission signed an MoU with China for improving transport connectivity (EU–China Connectivity Platform) and enhancing synergies between the BRI and the EU’s Trans-European Transport Network, also involving the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI). The China–EU Co-Investment Fund was established in 2017 through the collaboration between the European Investment Fund and the Silk Road Fund. However, these initiatives have had little success (Mardell, 2025). In 2019, the EU–China Strategic Outlook laid the foundations for a joint roadmap for the future of EU–China cooperation in technology. In December 2020, the EU and China reached a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (EU–China CAI) with the purpose of creating a more level playing field for EU investors. However, the CAI was blocked in 2021 by the European Parliament due to sanctions disputes. The same year, the EU launched the Global Gateway as a smarter and more sustainable alternative to the BRI, consistent with Western social and environmental standards. Although the Global Gateway is more modest in terms of budget, scale and attractiveness, it represents a turn towards a more competitive (and defensive) EU attitude towards BRI (García-Herrero, 2024) and the end point of a progressive deterioration of EU–China cooperation (Farnell & Crookes, 2016): “economic relations between China and Europe have become tense, as both sides gear up to defend their markets [and] the balance of economic power has clearly been shifting to China’s advantage” (Holslag, 2015, pp. 146–147).

However, the Global Gateway has not completely interrupted collaborations between China and European institutions. Indeed, while the latter tried to recalibrate relations with China by implementing defensive and derisking policies (Chimits et al., 2023), China and EU countries continued to collaborate both within the BRI but also along the BRI, within the so-called “third-party market cooperation”, i.e., cooperation between China and EU countries in third countries (Mardell, 2025).

Since the EU has neither provided a common response to the BRI12 nor a common EU strategy (Skala-Kuhmann, 2019), China has established economic–diplomatic relations with individual member countries and received quite heterogeneous responses. China has tried to exploit the lack of European cohesion by establishing relationships with countries most affected by the crisis (e.g., Greece) and the peripheral ones in Eastern Europe. With the latter (both EU members and candidates), China has developed particular platforms since 2012, such as the 16+1 framework, aimed at promoting cooperation for the construction of infrastructure and the development of these countries. These economic initiatives allowed China (but also Russia and Türkiye) to extend its political influence in EU member countries having uneasy relations with Brussels, and which could nevertheless influence the latter’s policies (Godement & Vasselier, 2017). In peripheral European countries, China has become a sort of alternative to the EU (Jakimów, 2019), further challenging a difficult and controversial European integration process.

The 18 EU member countries that have joined the BRI by signing a MoU are located mainly in Southern and Eastern Europe with the exception of Luxembourg and Austria (although the latter has never denied or confirmed having signed the MoU).13 Western and Northern EU countries had a more critical attitude towards BRI, fearing the alleged predatory nature of Chinese investments. This attitude began to be shared also by those countries that joined the BRI, especially from 2016, and complained about the lack of reciprocity by China, which limited foreign investment in its markets (Oertel, 2020). In 2018, 27 of the 28 national EU ambassadors to Beijing (with the exclusion of Hungary) prepared a report that denounced BRI’s detrimental effects on free trade and EU national interests, and the need for major transparency and adherence to EU rules and standards. Italy decided to leave the BRI in 2023 after signing the MoU in 2019 (Mazzocco & Palazzi, 2023).

It is interesting to note that the bulk of Chinese investments in Europe takes place within countries that did not join the BRI: “88 percent of [Chinese] investment flowed to just four countries, the ‘Big Three’ European economies (the UK, France and Germany) and Hungary” (Kratz et al., 2023, p. 3). While BRI infrastructure projects continue mostly in Southern, Central, and Eastern European (CEE) countries (and various non-EU Balkan states), Western Europe concentrates on high-tech, financial, and monetary connectivity. Thus, the impression is that a “two-speed Europe” emerges when it comes to China’s BRI, both in terms of sectors covered and geographical expansion (Casarini, 2024).

The concept of “two-speed Europe” has distant roots. The concept was originally linked to the fear that it would be increasingly difficult for member countries to achieve timely convergence and harmonious integration following the enlargement of the EU and the various episodes of economic crisis met (e.g., see Piris, 2011). The concept has been applied to Eurozone integration, the failure to adopt the euro (Adler-Nissen, 2016), the scarce degree of business cycle synchronization within the Eurozone (Camacho et al., 2020), and potential persistent divergences between “core” and “peripheral” member countries (e.g., Bayoumi & Eichengreen, 1993). A “two-speed Europe” seems to emerge also in the context of EU–China relations (Levy & Révész, 2022), with interesting implications for the approach of the BRI to the EU. Indeed, the concept of “two-speed Europe” implies China’s “double-strategy”, i.e., two different strategic approaches in dealing with core and peripheral European countries, with the first group mostly located in North-Western Europe. China’s aim in dealing with core European countries is to invest in strategic assets and R&D. European peripheral countries are mostly located in South-Eastern Europe, a strategic position to access the EU market. In these countries, China aims to develop large-scale infrastructure, build production and logistics hubs, and privatize strategic assets to reduce transportation costs (Di Donato, 2020).

It is worth remembering that, although most Chinese EU investments are outside the BRI (i.e., without signing a MoU), this does not mean that they pursue different goals compared to the typical BRI projects. As commented by Brattberg and Soula (2018), “Europe is a prime investment destination for the Belt and Road Initiative. Though not all Chinese investments in Europe are strictly BRI-related, Chinese foreign direct investment there has soared from under €1 billion in 2008 to €35 billion in 2016”.

The UK case is emblematic in this sense. Although the UK has not joined the BRI, in 2015, the country aimed to become China’s best Western partner, thus inaugurating a “golden era” for UK–China relations (Meredith, 2022) and mitigating the domestic “north–south divide”. Indeed, the northern UK area suffered the sunset of long-established mining and steel industries. Improving transport connectivity was considered a first step for the establishment of an economic “powerhouse” in the north of England (Ashbee, 2024). Austerity policies made it difficult for the British government to undertake massive investments in infrastructure without external resources. Xi Jinping’s visit to the UK in 2015 represented the opportunity to include the Northern Powerhouse UK initiative in the BRI landscape. In his opening address at the inaugural Belt and Road Summit held in Beijing in May 2017, Xi Jinping cited explicitly the “Northern Powerhouse initiative of the UK” among the policy initiatives for which China enhances coordination (BRA, 2017). UK–China relations implied a significant involvement of Chinese enterprises in the improvement of the UK’s communications infrastructure. Unfortunately, the cyber security concerns that emerged in the US also affected the UK (plus Australia and Japan). The consequence of these fears has been Huawei’s ban from participating in the national 5G network construction in these countries. The UK, in particular, decided to remove Huawei’s technological equipment from 5G national networks and communications infrastructure by 2027 (Kelion, 2020). Similar concerns have also emerged among various EU countries,14 which imposed restrictions on Huawei and ZTE for 5G network infrastructure, especially after the European Commission adopted the so-called 5G Cybersecurity Toolbox in 2020 (EU NIS, 2020). The same year, Sweden also banned Huawei and ZTE from its 5G networks on security grounds, while Germany planned to take Huawei and ZTE components out of 5G core networks by the end of 2026 (Kroet, 2024). In 2022, the UK Prime Minister Sunak declared that the golden era was over and China became a “systemic challenge to Britain’s values and interests” (Meredith, 2022). However, these turning points are not economically painless (O’Halloran, 2020). The removal of Huawei devices from the UK’s 5G has lowered the level of service, making the UK’s 5G network the worst in Europe (Stevens, 2024). This result sheds a disturbing light on the EU’s (and UK’s) real capabilities to provide competitive technological alternatives.

The main concerns are apparently linked to the DSR and its consequences in terms of cyber security and political influence, particularly in Western European countries. Also, in the case of the more traditional BRI projects, “Chinese investment in critical infrastructure all over the EU has raised security concerns” (Calatayud, 2023, p. 1). In particular, the EU raised concerns on issues such as lack of transparency, debt sustainability, open procurement, and poor standards in terms of labour and human rights and environmental protection (Brattberg & Soula, 2018).

Whereas EU institutions may try to control EU member countries and impose European data protection standards and conditions in its economic relations with China15, the situation is more delicate vis-à-vis EU candidate countries. In particular, Balkan countries (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia) are deeply involved in various BRI projects, and this may have consequences for the EU both through their geographical proximity and their possible EU membership in the near future. Western Balkan countries are strategically important for China because they are key access points to central Europe. China invested more than EUR 6 billion in this area, with particular attention to Serbia and Montenegro, as the port of Bar represents an important access into Europe from the Adriatic (Barkin & Vasovic, 2018).

In light of these issues, it is essential to have a clear overview of the BRI projects undertaken in the European context, going beyond the projects undertaken following the signing of an MoU. To the best of our knowledge, detailed reviews of Chinese investment projects in Europe in the frame of the BRI are rare and incomplete. In the next section, BRI and like-BRI projects from 2005 to 2021 are analyzed in all European countries, and their characteristics and those of the companies involved are examined.

3. The BRI in Europe: An Empirical Comparative Analysis

3.1. Data and Methodology

This article offers a comparative analysis of 727 projects in the context of China’s BRI within 46 European countries. Data have been collected from the IISS China Connects platform.16 Although the BRI was officially launched in 2013, our analysis also includes projects undertaken from 2005 and classified as ‘BRI-like’, i.e., projects with BRI characteristics able to promote a “holistic understanding of global Chinese connectivity projects” and preparatory to the more recent Digital Silk Road (DSR) initiative (see IISS China Connects platform). Therefore, our analysis considers projects undertaken between 2005 and 2021, although the dataset about the DSR is updated up to December 2020, and the dataset about the BRI covers the period through December 2021. The list of all European countries is reported in Table 1, which indicates the number of projects associated with each country, the type of relationship with the EU, their geographical location within Europe (East, West, South, and North), and finally, the year the countries joined (and left) the BRI. For completeness, Table 1 also contains European countries that have not hosted BRI projects (8 countries over a total of 54 countries), although these will not be further considered in the analysis.

Table 1.

European countries.

We have considered all the countries that are part of geographical Europe in the United Nations Geoscheme,17 plus other EU member countries, candidate countries for membership, and countries associated with the EU (Cyprus, Georgia, Türkiye, and the island of Greenland). Countries that have not been recipients of Chinese investments in line with the BRI project have not been considered in the analysis (Åland Islands, Channel Islands, Gibraltar, Holy See, Ireland, Isle of Man, Lichtenstein, Svalbard and Jan Mayen Islands). This implies that 46 countries have been analyzed.

We have retrieved the location, typology, year, status of each project (i.e., completed, cancelled, halted, ongoing, or planned), and the main enterprises involved. Table 2 reports the classification of projects according to their typology. The 25 typologies have been classified according to their involvement in the more traditional infrastructure projects with poor digital content (BRI) or DSR. Some typologies contain projects that have been classified both as BRI and DSR. Projects within the Health Silk Road (E-Health) have been classified both as part of the BRI and the DSR. However, in this article, the Health Silk Road is kept in a distinct category.

Table 2.

Characteristics and classification of projects between the BRI and the DSR.

3.2. BRI Projects Among European Countries: Status and Dynamics

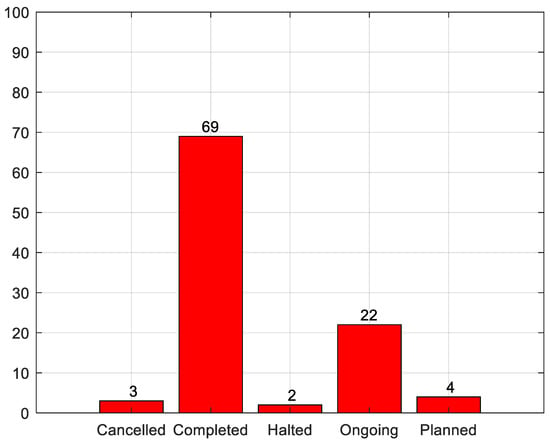

Figure 1 allows us to analyze the status of the 727 projects considered in this article. Currently, 69% of the projects have been completed, 22% have to be completed, 5% have been cancelled or halted, and the remaining 4% are only planned.

Figure 1.

Status of projects (percentage values). Source: IISS China Connects platform. Own elaboration. Data in the Figure are percentages. The total number of projects cancelled is 19, completed 504, halted 17, ongoing 157, and planned 30.

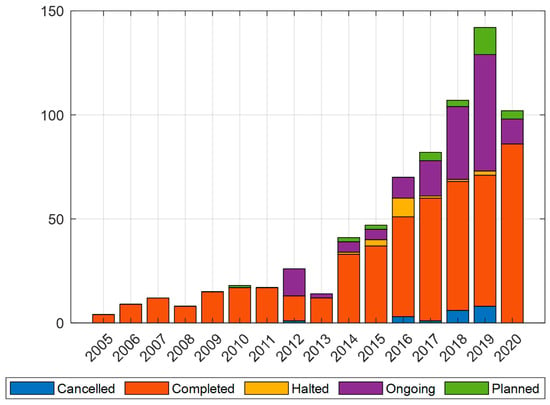

According to Figure 2 and although some BRI-like projects have been undertaken since 2005, a significant acceleration has occurred since 2013, the year the BRI was inaugurated. The year when the greatest number of projects were launched or planned was 2019. This is probably the consequence of the great number of European countries that joined the BRI in the period 2015–2018 (see Table 1). It is interesting to notice that the vast majority of projects currently halted or cancelled date back to fairly recent periods. This may be connected to the cyber security concerns discussed in Section 2.5. However, it is necessary to analyze the typologies of the halted/cancelled projects to confirm this hypothesis. Also significant is that the number of new projects started to decline following the outbreak of the pandemic. Our current data do not allow us to go beyond 2020, since data about DSR projects are updated only up to 2020. Further research may test the impact of geopolitical imbalances following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 on BRI projects in Europe.

Figure 2.

Number of projects in Europe by year and status. Source: IISS China Connects platform. Own elaboration. 2021 projects are not in the Figure since data about DSR ended in 2020.

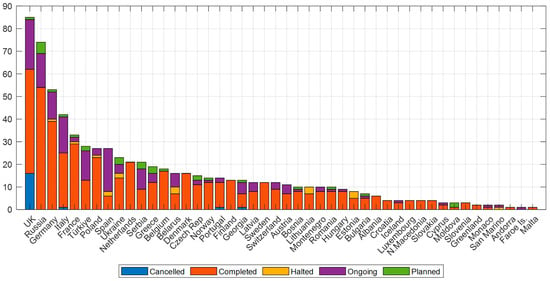

As reported in Table 1, 28 European countries have joined BRI (all EU candidate countries and 17 EU member countries). Only eight European countries have not joined the BRI, and neither are they involved in BRI-like projects: the majority are microstates, except Ireland and Lichtenstein. Figure 3 clarifies the distribution of projects among European countries: 12% of projects are located in the UK, 10% in Russia, 7% in Germany, 6% in Italy, and 5% in France. The remaining 60% of the projects are distributed among the other European countries. It is interesting to note how the vast majority of the projects that have been cancelled are located mainly in the UK, with fewer cases in Italy, Portugal, and Georgia.

Figure 3.

Number of projects for each European country and their status. Source: IISS China Connects platform. Own elaboration.

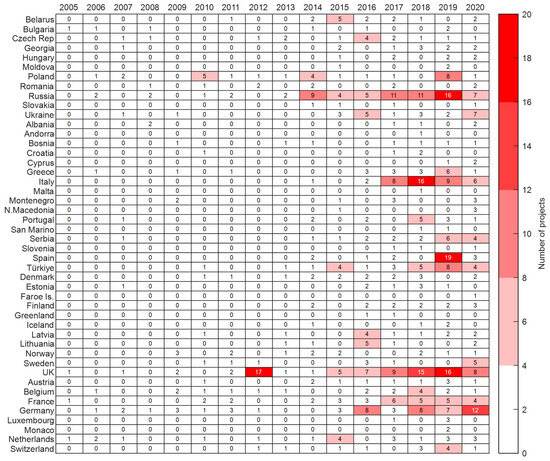

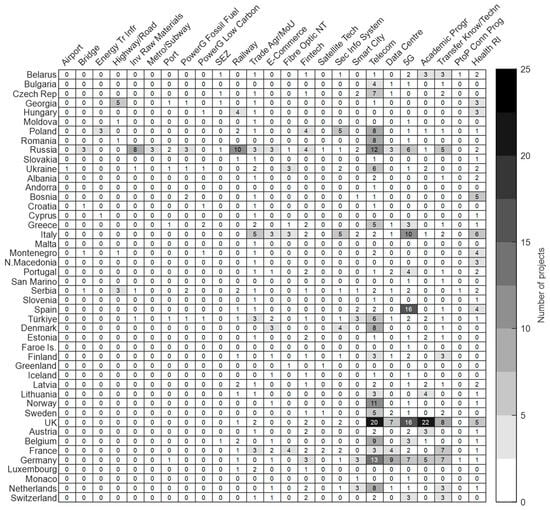

Figure 4 shows the temporal distribution of projects within each country. The majority of projects have been initiated after 2013 in all countries. However, China’s relations with countries such as Germany, the UK, Poland, and Russia appear to precede the launch of the BRI and have persisted in time.

Figure 4.

Temporal distribution of projects within each country. Source: IISS China Connects platform. Own elaboration. Values range from 0 to 19. Countries are ordered according to their geographical position (East, South, North, and West).

3.3. Projects Typologies Within Europe: The Role of the Digital Silk Road

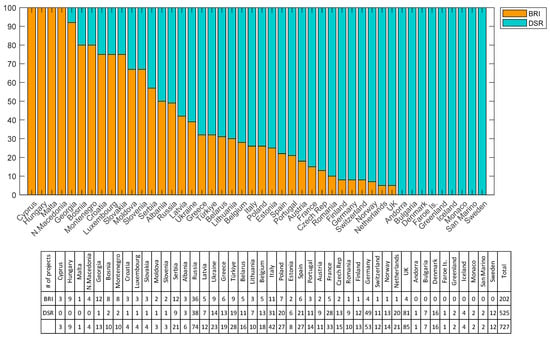

Of the 727 projects analyzed, 72% are classified as part of the DSR, while the remaining 28% are part of the BRI. This suggests that BRI investments in Europe have a high digital content and can be traced back to the DSR. However, these proportions change according to the country, as Figure 5 demonstrates. There is strong heterogeneity among European countries in terms of the dominance of BRI or DSR projects, with some geographical coherence. Indeed, the share of BRI projects is close to or higher than 50% in South-Eastern countries (including Cyprus, Hungary, Malta, North Macedonia, Georgia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Croatia, Slovakia, Moldova, Slovenia, Serbia, Albania, and Luxembourg as an exception).

Figure 5.

Percentage of BRI and DSR projects for each country (number of projects in the Table). Source: IISS China Connects platform. Own elaboration.

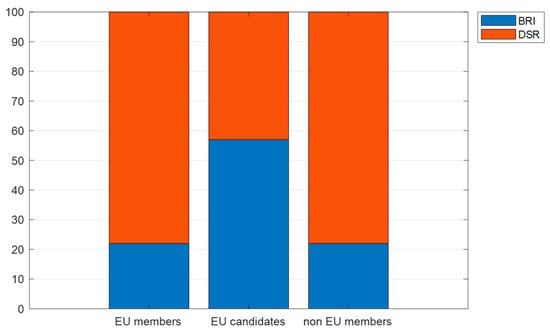

Figure 6 underlines how the share of BRI projects is higher than 50% among EU candidate countries in South-Eastern Europe, while DSR projects predominate among non-EU countries and most Western–Northern countries. Concrete examples of BRI investments include the East–West Highway Corridor in Georgia, the Budapest–Belgrade Railway in Serbia, the MINOS Solar Power Project in Greece, the Emba Hunutlu power station in Türkiye, and the Yuzhny Black Sea Port in Ukraine. Among DSR investments, it is worth mentioning 5G broadcasts in many UK cities, as well as extensive cooperation with Chinese companies such as Huawei and Alibaba in the fields of communications, information security systems, smart cities, and fintech in Germany and France. These results seem to confirm a “two-speed Europe”, as discussed in Section 2.5.

Figure 6.

Percentage of BRI and DSR projects for each group of countries (EU members, candidates, and non-EU countries). Source: IISS China Connects platform. Own elaboration.

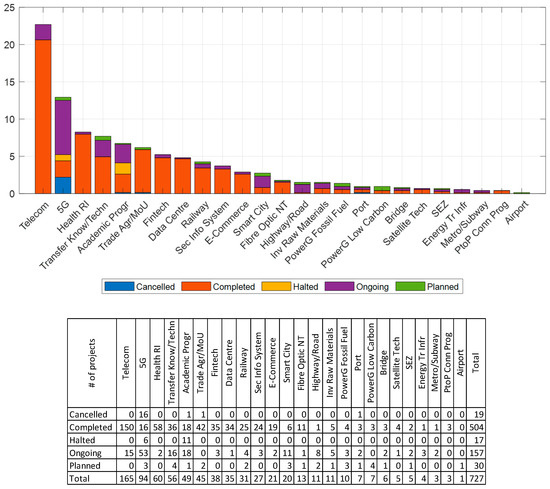

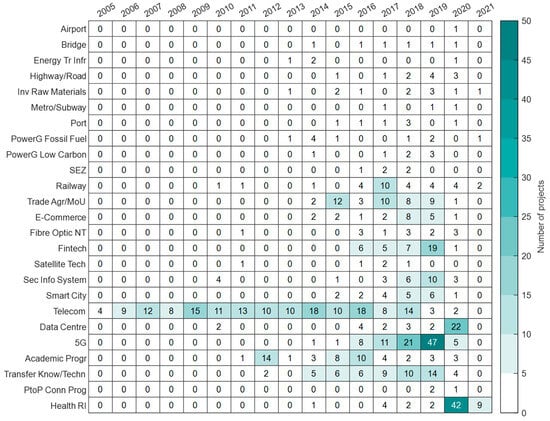

Figure 7 offers the opportunity to investigate project typologies in more detail. More than 30% of the projects concern telecommunications (i.e., telecom and 5G). Interestingly, most of the cancelled projects involved 5G, and most of the halted ones are academic programs. 5G is the most problematic category in terms of uncompleted status (i.e., halted, cancelled, or ongoing), which aligns with the analysis of Section 2.5.

Figure 7.

Types of projects in percentage values (number of projects in the Table). Source: IISS China Connects platform. Own elaboration.

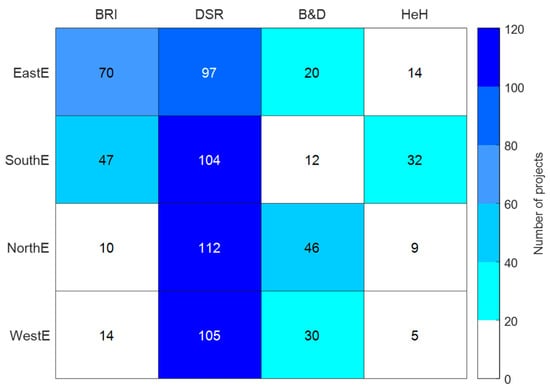

The 25 project typologies have been grouped into 4 categories in order to investigate the relationship between project features and European countries: pure BRI, pure DSR, hybrid type (both BRI and DSR), and the Health Silk Road/E-Health. The latter is kept distinct to estimate the role of the COVID-19 pandemic, despite HSR projects being classified as BRI or DSR. Countries have been grouped according to their geographical location (Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, Northern Europe, Western Europe). Figure 8 reports the results. BRI projects have been located in particular in Eastern and Southern Europe, similarly to the Health Silk Road projects (concentrated in the years of the COVID-19 pandemic, see Figure 9). Although the DSR projects are the most numerous and widespread across Europe, they are mostly concentrated in Northern and Western Europe, especially if also hybrid typologies are considered. The more traditional BRI projects concerning physical infrastructure are located mostly in South and Eastern Europe. China has concluded various deals with the European countries most affected by the crisis. The case of the strategically important Greek Port of Piraeus is emblematic in this sense. In 2016, the Port was acquired by the Chinese state-owned enterprise China Ocean Shipping (Group—COSCO) and experienced a strong productivity increase, although the adopted labour and environmental practices raised some concerns among local communities (Calatayud, 2023).

Figure 8.

Distribution of projects among European countries according to typologies and geographic regions. Source: IISS China Connects platform. Own elaboration. E = Europe, B&D = both BRI and DSR, HeH = Health Silk Road/E-Health. In this Figure, projects part of the Health Silk Road/E-Health are kept distinct from other BRI and DSR projects. Values range from 5 to 112.

Figure 9.

Temporal distribution of projects according to typologies. Source: IISS China Connects platform. Own elaboration. Data range from 0 to 47. Projects have been ordered according to the digital content (BRI, DSR and HeH).

These results are coherent with those in Figure 5 and Figure 6 and the comment by Brattberg and Soula (2018): “while the bulk of China’s investments still go to Western Europe, there has been an uptick in BRI-related activities in Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe including the Western Balkans. These regions generally have political and regulatory environments that are more favorable to China than those in Western Europe. Moreover, their infrastructure needs are often substantial and their available financing options more limited. For these reasons, China has, for instance, jumped in to finance a $1.1 billion railway between Budapest and Belgrade to realize its vision of creating a transportation and energy hub for the BRI, though progress has so far been slow”.

Figure 9 shows that the vast majority of projects implemented before 2013 dealt with telecommunications and academic programs. 5G projects are mostly concentrated between 2016 and 2019, while the Health Silk Road projects are concentrated in the years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 10 presents the geographical distribution of projects according to their typology. Most telecommunication projects are located in the UK, Germany, Russia, and Norway. Academic programs are concentrated in the UK. 5G projects are concentrated in the UK, Spain, and Italy. Russia is the country with the greatest variety of projects undertaken, followed by Türkiye. Most physical infrastructure (e.g., airports, ports, railways) is concentrated in Georgia, Poland, Hungary, Russia, and Serbia.

Figure 10.

Number of projects within each European country according to typology. Source: IISS China Connects platform. Own elaboration. Data range from 0 to 22. Countries are ordered according to their geographical position (East, South, North, and West). Projects have been ordered according to the digital content (BRI, DSR and HeH).

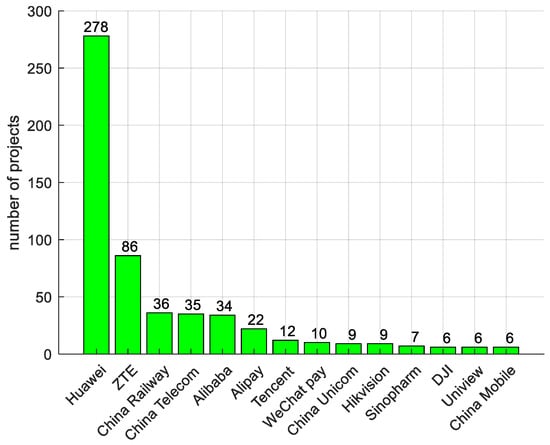

3.4. Enterprises Involved in the Projects

In the 727 projects taken into consideration, 148 Chinese companies/institutions were involved.18 Many companies are state-owned enterprises. Only 14 companies/institutions take part (or have taken part) in more than five projects. These 14 companies have participated in 74% of the total number of projects (541 projects in total). Huawei alone was involved in 278 projects, or 38% of the total, in line with the predominance of the DSR. This means that, despite the high number of enterprises/institutions involved in the BRI within Europe, the vast majority of projects have involved a small group of powerful enterprises/institutions (together with other enterprises in some cases), as reported in Figure 11. It is worth noting that 17 of the 19 cancelled projects involved Huawei: 1 in Portugal and 16 in the UK. Of these 17 projects, 16 concern 5G and only 1 is an academic program in the UK.

Figure 11.

Companies involved in the projects (with a number of projects > 5). Source: IISS China Connects platform. Own elaboration. Alibaba also includes Alibaba group, Alibaba foundation, and Alibaba cloud. Sinopharm includes China National Pharmaceutical Group and China Sinopharm International Corporation. China Railway includes China Railway 9th Bureau; China Railway Electrification Engineering Group, China Railway Construction Corporation (CRCC), China Railway Group (CREC), China Railway International Group, China Railway Major Bridge Engineering Group, China Railway Harbin Group, and China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation (CRRC). Huawei includes Huawei Marine. Tencent includes Tencent Cloud. Since more companies have taken part in the same project in some cases, the sum of projects in Figure 11 is 556 instead of 541.

Table 3 indicates the characteristics of each one of the 14 companies/institutions reported in Figure 11, the number and types of projects followed, and the countries covered. Half of the companies are state-owned.19 Except for Sinopharm (pharmaceutical sector) and China Railway (transport sector), all the other companies are specialized in e-commerce, telecommunications, surveillance systems, drones, or online payment platforms. Some of them have been banned in the US or have met difficulties in Europe, as discussed in Section 2.4 and Section 2.5.

Table 3.

Description of the companies involved in the projects (with a number of projects > 5).

It is noteworthy to mention the rivalry between Alipay and WeChat pay as online payment platforms, which confirms the relevance for China of fintech in the European context. The geographical extension of these companies spreads throughout Europe. These data seem to confirm that the BRI focuses above all on the digital sector with a large and predominant presence in Western countries (as discussed in Section 2), while investments in infrastructure, especially in Eastern European countries, are residual (with the exception of transport).

4. Conclusions

The BRI is an ambitious project that has evolved over time both in terms of geographical extension, type of initiative, and intervention strategy. In 2018, the countries that joined the BRI already represented more than 33% of global GDP, and over 50% of the world’s population (OECD, 2018).

Successes and risk factors apart, the BRI represents a non-Western way of addressing the global infrastructure gap. China has proposed a pragmatic and flexible platform capable of completing projects and infrastructures that would otherwise be unachievable in the Western context, due to the rigidity of international treaties and the limited ability of free market forces to promote growth in the poorest contexts. There is no shortage of dark sides, though: from the opacity of procedures to the risk of excessive debt, corruption, compromises, violations of human rights protection and environmental protection, and political influence through soft power.

The BRI influences the geopolitical balance by challenging US hegemony. In the EU context, the BRI has filled the void left by European institutions on the periphery of the EU. It has invested in strategic infrastructure in those countries affected by austerity measures (the most significant case being the Greek port of Piraeus) and has offered prospects for growth and infrastructural development in Eastern European countries (see Figure 5 and Figure 10) and especially in candidate countries to EU membership (see Figure 6). A completely different strategy was adopted towards the countries of Northern and Central Europe which, despite not having joined the BRI, are the main recipients of Chinese investment flows in Europe in key technological sectors, such as telecommunications systems and payment systems (fintech) (see Figure 10). China has therefore adopted a dual strategy for a de facto “two-speed Europe”.

The empirical investigation of this article, which analyzed 727 projects in Europe from 2005 to 2021 in the context of the BRI, confirms the existence of a dual strategy for a “two-speed Europe”. But the most interesting aspect concerns those countries most sceptical of the BRI (North-Central European countries), which have not signed any MoU. In spite of this, the Chinese investments have been fully coherent with the DSR goals. It should be noted that China’s major commercial and political partners (such as Russia and North Korea) are not part of the BRI. This may suggest that signing the MoU is actually targeted at the most problematic countries. This could also explain Italy’s exit from the BRI and its recent strengthening of trade relations with China within a political and diplomatic context more suited to its characteristics and needs. Since the current DSR data do not allow us to go beyond 2020, further research may test the impact of geopolitical imbalances following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and other policy changes (e.g., 5G policies) on Chinese projects in Europe. Similar analysis would require the comparison of our present data with other databases and the use of more sophisticated statistical analysis.

Despite the limitations, our empirical analysis suggests that the Chinese strategy aims to achieve BRI/DSR goals in the most developed countries through other types of agreements. This strategy seems to have worked particularly well in Europe. In Northern and Western Europe, there have been massive Chinese investments in telecommunications, surveillance, data centres, and the transfer of knowledge. These were sensitive and strategic investments that the EU began to question with significant delay (e.g., 5G cancellations clustered in the UK, see Figure 7), demonstrating poor coordination between member countries and little political foresight. The technological backwardness of the West may have played a role in this dynamic, as the technologies provided by Chinese companies such as Huawei and ZTE (see Figure 11) have no real competitors in the European context, which has traditionally rejected common industrial policies to create technological champions.

The preeminence of the Chinese technological giants cannot be questioned. The West (the US, but also partly the EU) could only react by banning some Chinese companies. However, this is costing European companies dearly and may prevent their learning process, as they are forced to rely on more expensive and technologically less advanced solutions and suppliers. The BRI, despite all its limitations, shows the economic strength of the synergy between private companies and state policies for the promotion of national interests.

Although the results of our empirical analysis require further research and adequate interpretation within recent theories on international relations and geoeconomics, we can formulate some preliminary conclusions. First, the task of European countries and the EU should be to harmonize their national and community interests in order to have compatible approaches to external investors and challenges. Second, European countries and the EU should be engaged with the BRI, having better internal coordination and a stronger common policy of investment in strategic sectors, also by means of common resources. The EU must take what is good in the BRI platform (public and private sector synergy, planning, flexibility and pragmatism, long-term vision) and correct its weaknesses and drawbacks (e.g., prevention of corruption, protection of rights, respect for the environment). This new approach may be fundamental to regain confidence in peripheral European countries, return to competitiveness, and rebalance the “two-speed Europe”, a situation that does not favour further European integration.

In this context, further research is also needed for a deeper comparison between the BRI and the potential of Western alternatives discussed in Section 2.3. Attention will need to be paid to what the EU can actually achieve in terms of pragmatism and flexibility in light of its institutional and regulatory framework. Only in this perspective can the EU require that China take inspiration from the European context and experience on how to improve the reception of its investment initiatives by focusing on reciprocity, security guarantees, and protection of rights and the environment. Even in this context, further research is needed on the aspects that can actually be modified and improved in the Chinese approach and institutional framework of investments abroad.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C. and B.D.; methodology, S.C.; software, S.C.; formal analysis: S.C.; data curation, S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C. and B.D.; writing—review and editing, S.C. and B.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data came from the IISS China Connects platform (https://chinaconnects.iiss.org/).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See https://chinaconnects.iiss.org/about.aspx (accessed on 29 September 2025). |

| 2 | See routes and corridors at https://www.euobor.org/index.php?app=OBOR (accessed on 29 September 2025). |

| 3 | See http://en.moj.gov.cn/2023-10/11/c_929533.htm (accessed on 29 September 2025). |

| 4 | 44 countries are in Sub-Saharan Africa, 19 countries are in Middle East and North Africa, 25 countries are in East Asia and Pacific, 23 countries are in Latin America and Caribbean and 34 countries are in Europe and Central Asia. 17 countries are part of the EU while 8 countries are part of the G20. One country (Italy) is part of G7 but it left the BRI in December 2023. Panama exited the BRI in February 2025 (see Nedopil, 2025). |

| 5 | See http://english.scio.gov.cn/m/whitepapers/2023-10/12/content_116739405.htm (accessed on 29 September 2025) for more details. |

| 6 | See https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2018/01/26/content_281476026660336.htm (accessed on 29 September 2025). for more details. |

| 7 | BeiDou is a satellite system alternative to GPS. It reached full global coverage in 2020. It has a larger constellation of satellites than GPS and is more modern and therefore more accurate (i.e., in terms of positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) data). BeiDou represents a real threat to US GPS dominance and an attractive alternative even in developing countries (see Sewall et al., 2023). |

| 8 | An emblematic example is the Chinese-built highway project in Montenegro. It was designed to link the port of Bar in Montenegro to Serbia. A Chinese loan for the construction of the first part of the infrastructure has sent Montenegro’s debt soaring. The government was forced to adopt austerity measures to balance its finances. Despite this, according to the International Monetary Fund, Montenegro cannot afford to take on any more debt to complete the project. China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC), the state-owned Chinese company that is building the first part of the highway, signed a MoU in 2018 to complete the rest of the road on the basis of a public–private partnership. However, these partnerships are viewed with suspicion in Europe due to their potential economic unsustainability (Barkin & Vasovic, 2018). |

| 9 | China signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the United Nations Environment Programme with the goal of building a green BRI for 2017–2022. See http://english.scio.gov.cn/m/whitepapers/2023-10/12/content_116739405.htm (accessed on 29 September 2025). Environmental goals have been confirmed during the Third Belt and Road Forum in 2023. |

| 10 | See the Thematic Forum on Clean Silk Road of the Third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation held in Beijing on 18 October 2023. |

| 11 | See https://www.bluedot-network.org/about (accessed on 29 September 2025). |

| 12 | A still timid response to the BRI appears to be a new strategy promoted by the EU aimed at improving connectivity towards Eastern neighborhood and the Balkans (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/50752_en, accessed on 29 September 2025). European connectivity projects would be financed by both public and private funding mechanisms, subjected to a regulatory framework and coherent with the rules-based international system (Brattberg & Soula, 2018). |

| 13 | The countries are Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Czech Republic, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. |

| 14 | These concerns seem to be linked to an event that occurred in Poland in 2019. An employee of Huawei was arrested on spying charges. As a reaction, the Poland’s internal affairs minister proposed to work on an EU-NATO joint position about Huawei potential exclusion from their markets (The Guardian, 2019). Similar accidents happened also in other countries. |

| 15 | In his speech at the May 2017 Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, the European Commission Vice-President Jyrki Katainen claimed that “China is at one end of the ‘Belt and Road’—Europe is at the other. Done the right way, more investment in cross-border links could unleash huge growth potential with benefits for us all […] any scheme to connect Europe and Asia should adhere to the following principles […] it should be an open initiative based on market rules and international standards […] We need to build a true network and not a patchwork. […] Transparency on our plans and activities must be the basis for our cooperation […] Sustainability is essential […] We must use the wisdom of the multilateral banks […] Finally, we should ensure that there are real benefits for all stakeholders” (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/26154_en, accessed on 29 September 2025). |

| 16 | See https://chinaconnects.iiss.org/ (accessed on 29 September 2025). |

| 17 | See https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/ (accessed on 29 September 2025). It is commonly referred to as the M49 standard in the UN Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use. |

| 18 | For 66 project the companies/institutions involved were not indicated in the database. In some projects more than one company/institution was involved. |

| 19 | It is not always easy to establish the government’s actual influence on Chinese private businesses. An important case is that of Alipay (see Lianhe Zaobao, 2024). |

References

- Adler-Nissen, R. (2016). The vocal euro-outsider: The UK in a two-speed Europe. The Political Quarterly, 87(2), 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbee, E. (2021). The blue dot network, economic power, and China’s belt & road initiative. Asian Affairs: An American Review, 48(2), 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbee, E. (2024). The United Kingdom, the belt and road initiative, and policy amalgams. Asia Europe Journal, 22, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkin, N., & Vasovic, A. (2018, July 16). Chinese ‘highway to nowhere’ haunts Montenegro. Reuters. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-silkroad-europe-montenegro-insi/chinese-highway-to-nowhere-haunts-montenegro-idUSKBN1K60QX/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Bayoumi, T., & Eichengreen, B. (1993). Shocking aspects of European monetary unification. In F. Torres, & F. Giavazzi (Eds.), The transition to economic and monetary union in Europe (pp. 193–240). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bonelli, E. (2017). One belt one road: Soft law as a Chinese alternative to international treaties. ISPI Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale. Available online: https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/one-belt-one-road-soft-law-come-alternativa-cinese-ai-trattati-internazionali-16493 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- BRA. (2017, November 20). The UK’s northern powerhouse initiative needs a belt and road strategy. Belt and Road Advisory. Available online: https://beltandroad.ventures/beltandroadblog/2017/11/20/the-uks-northern-powerhouse-initiative-needs-a-belt-and-road-strategy (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Brattberg, E., & Soula, E. (2018, October 19). Europe’s emerging approach to China’s belt and road initiative. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available online: https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2018/10/europes-emerging-approach-to-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative?lang=en (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Burton, C. (2020). Huawei’s geostrategic role (Red Watch Report). European Values Center for Security Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Calatayud, L. C. (2023). The complex relationship between Europe and Chinese investment: The case of Piraeus (Working Paper No. 01). Lau China Institute, King’s College London. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, M., Caro, A., & Lopez-Buenache, G. (2020). The two-speed Europe in business cycle synchronization. Empirical Economics, 59(3), 1069–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarini, N. (2016). When all roads lead to Beijing. Assessing China’s new silk road and its implications for Europe. The International Spectator, 51(4), 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarini, N. (2024). The future of the Belt and Road in Europe: How China’s connectivity project is being reconfigured across the old continent– and what it means for the Euro-Atlantic alliance (Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) Papers). Istituto Affari Internazionali. [Google Scholar]

- Chimits, F., Ghiretti, F., & Stec, G. (2023). Updating the EU action plan on China. De-risk, engage, coordinate. Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS). [Google Scholar]

- China Power. (2017, May 8). How is the belt and road initiative advancing China’s interests? China power project. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Available online: https://chinapower.csis.org/china-belt-and-road-initiative (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Degli Esposti, N. (2025). Assessing western discourse on ‘Chinese Neocolonialism’ in the global South. The International Spectator, 60(2), 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Donato, G. (2020, May 6). China’s approach to the belt and road initiative and Europe’s response. Italian Institute for International Political Studies ISPI. Available online: https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/chinas-approach-belt-and-road-initiative-and-europes-response-25980 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Edstrøm, A. C., Hauksdóttir, G. R. T., & Lackenbauer, P. W. (2025). Cutting through narratives on Chinese arctic investments. Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- EU NIS. (2020, January 23). Cybersecurity of 5G networks—EU toolbox of risk mitigating measures (CG Publication 01/2020). NIS Cooperation Group.

- Farnell, J., & Crookes, P. I. (2016). The politics of EU-China economic relations. An uneasy partnership. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, K. P., Kring, W. N., Ray, R., Moses, O., Springer, C., Zhu, L., & Wang, Y. (2023). The BRI at ten: Maximizing the benefits and minimizing the risks of China’s belt and road initiative. Global Development Policy Center. [Google Scholar]

- García-Herrero, A. (2024, December 16). David and goliath: The EU’s global gateway versus China’s belt and road initiative. Bruegel Newsletter. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/newsletter/david-and-goliath-eus-global-gateway-versus-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Ghiasy, R., & Krishnamurthy, R. (2020). China’s digital silk road. Strategic implications for EU and India. Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies (IPCS) and the Leiden Asia Centre (LAC). [Google Scholar]

- GIO. (2018). Global Infrastructure Outlook. Infrastructure investment needs 56 countries, 7 sectors to 2040. Global Infrastructure Hub. [Google Scholar]

- Godement, F., & Vasselier, A. (2017). 16+1 or 1x16? China in Central and Eastern Europe. In F. Godement, & A. Vasselier (Eds.), China at the gates. A new power audit of EU-China relations (pp. 64–74). European Council on Foreign Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Hansbrough, J. V. (2020). From the blue dot network to the blue dot marketplace: Away to cooperate in strategic competition. In A. L. Vuving (Ed.), Hindsight, insight, foresight. Thinking about security in the Indo-Pacific. Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep26667.16 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Hawkins, A. (2023, October 16). China woos global south and embraces Putin at belt and road Beijing summit. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/oct/16/china-woos-global-south-and-embraces-putin-at-belt-and-road-beijing-summit (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Himmer, M., & Rod, Z. (2022). Chinese debt trap diplomacy: Reality or myth? Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 18(3), 250–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holslag, J. (2015). Explaining economic frictions between China and the European union. In V. K. Aggarwal, & S. A. Newland (Eds.), Responding to China’s rise: US and EU strategies, the political economy of the Asia Pacific (pp. 131–150). Chapter 7. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, S., Parks, B. C., Reinhart, C. M., & Trebesch, C. (2013). China as an international lender of last resort, policy research working paper 10380. World Bank. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099450403272313885/pdf/IDU046bbbd8d06cc0045a708397004cbf4d2118e.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Hurley, J., Morris, S., & Portelance, G. (2019). Examining the debt implications of the belt and road initiative from a policy perspective. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 3(1), 139–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakimów, M. (2019). Desecuritisation as a soft power strategy: The Belt and Road Initiative, European fragmentation and China’s normative influence in Central-Eastern Europe. Asia Europe Journal, 17, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelion, L. (2020, July 14). Huawei 5G kit must be removed from UK by 2027. BBC. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-53403793 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Kratz, A., Zenglein, M. J., Sebastian, G., & Witzke, M. (2023). EV battery investments cushion drop to decade low. Chinese FDI in Europe: 2022 update. Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS). [Google Scholar]

- Kroet, C. (2024, August 12). Eleven EU countries took 5G security measures to ban Huawei, ZTE. Euronews. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/next/2024/08/12/eleven-eu-countries-took-5g-security-measures-to-ban-huawei-zte (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Levy, K., & Révész, Á. (2022). No common ground: A spatial-relational analysis of EU-China relations. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 27(3), 457–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lianhe Zaobao. (2024, January 10). Has alipay become a state-owned enterprise? Think China. Available online: https://www.thinkchina.sg/economy/has-alipay-become-state-owned-enterprise (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Mardell, J. (2025, March 26). Should the EU “Reconnect” with China? Internationale Politik Quarterly. Available online: https://ip-quarterly.com/en/should-eu-reconnect-china (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Mazzocco, I., & Palazzi, L. (2023, December 14). Italy withdraws from China’s Belt and Road Initiative. CSIS—Center for Strategic & International Studies. Available online: https://www.csis.org/analysis/italy-withdraws-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Meredith, S. (2022, November 29). ‘Golden era’ for Britain and China’s relationship is over, UK PM Rishi Sunak says. CNBC. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/11/29/uk-pm-rishi-sunak-says-the-golden-era-for-britain-and-china-is-over.html (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Nedopil, C. (2025). Countries of the belt and road initiative. Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University. Available online: www.greenfdc.org (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- OECD. (2018). OECD business and finance outlook 2018. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertel, J. (2020, September 7). The new China consensus: How Europe is growing wary of Beijing (ECFR Policy Briefs). European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR). Available online: https://ecfr.eu/?p=2853 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- O’Halloran, J. (2020, July 10). UK mobile operators warn removing Huawei tech would cost ‘low billions’ and take five years. Computer Weekly. Available online: https://www.computerweekly.com/news/252485974/UK-mobile-operators-warn-removing-Huawei-tech-would-cost-low-billions-and-take-five-years (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Piris, J. C. (2011). The future of Europe: Towards a two-speed EU? Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, R. K. (2023). Digital silk road. Beijing’s digital footprint and its political implications. ORCA: Organisation for Research on China and Asia. Available online: https://www.orcasia.org/digital-silk-road (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Rong, X. (2022). The silk road and cultural exchanges between east and west. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Sewall, S., Vandenberg, T., & Malden, K. (2023, February). China’s BeiDou: New dimensions of great power competition. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School. [Google Scholar]

- Skala-Kuhmann, A. (2019). European responses to BRI. An overdue assessment. Horizons: Journal of International Relations and Sustainable Development, (14), 144–157. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/e48504060 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Stevens, C. (2024, February 15). Since Huawei was banned, is the UK’s 5G service the worst in Europe? Eureporter. Available online: https://www.eureporter.co/business/digital-technology/2024/02/15/since-huawei-was-banned-is-the-uks-5g-service-the-worst-in-europe/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).