Promoting Women’s Economic Empowerment Through Economic Diplomacy: The Case of the Arab Gulf’s Free Trade Agreements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Background

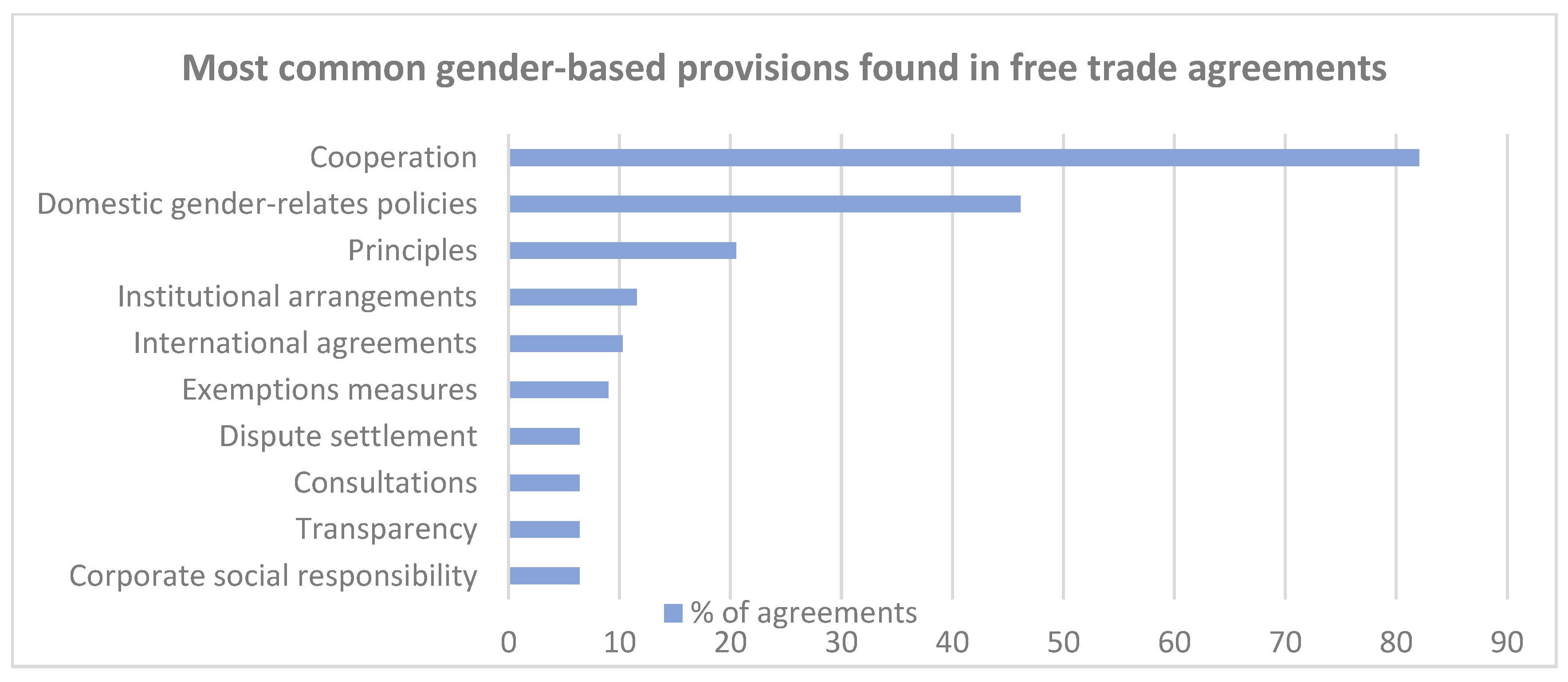

2.1. The Trade Policy and Gender Nexus

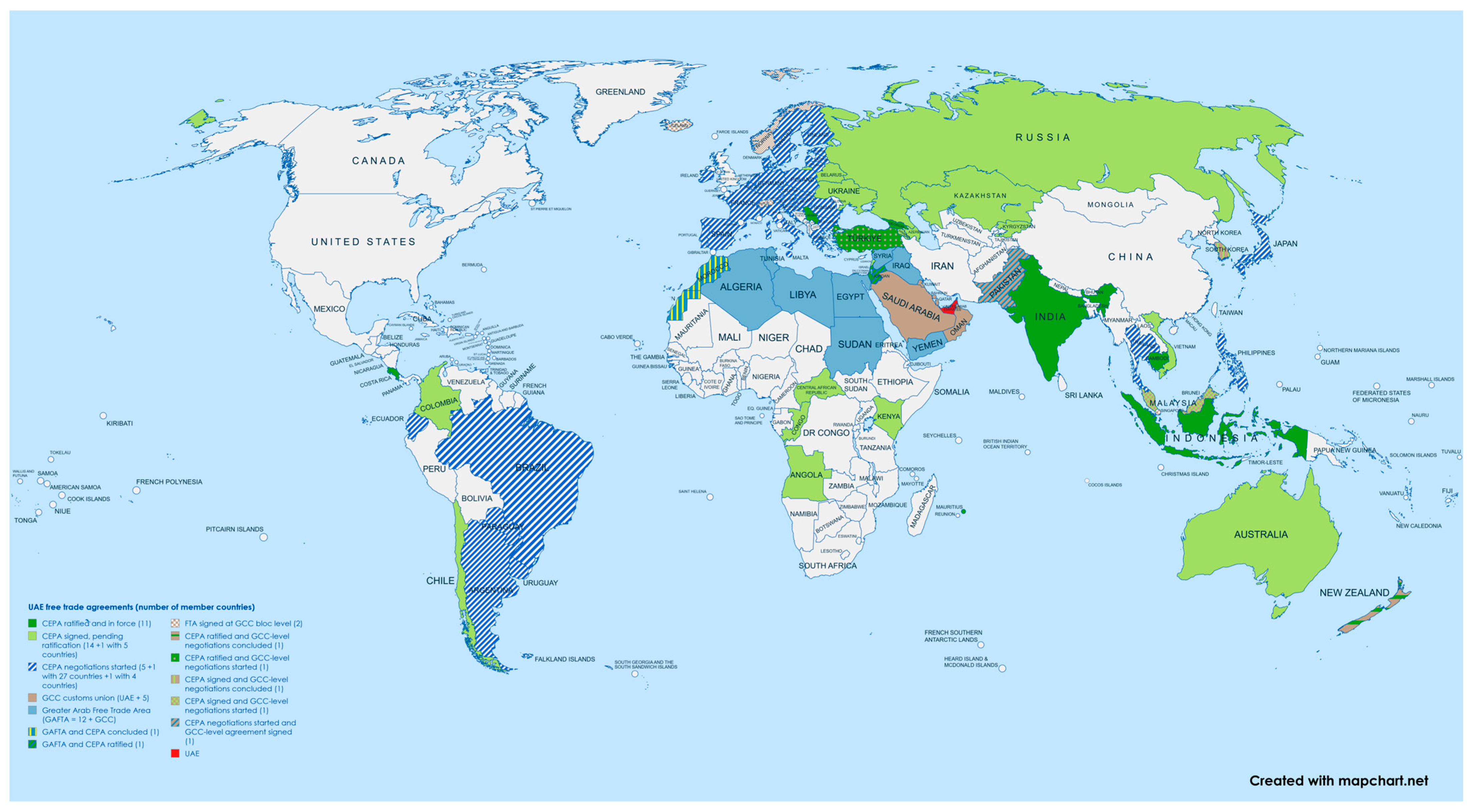

2.2. GCC Economic Diplomacy and Economic Gender Empowerment Efforts

3. Methodology

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Product schedules for customs’ purposes can contain gender terms like “women’s garments”, for example, but this does not count as a term increasing the gender responsiveness of the agreement. |

| 2 | The UAE Gender Balance Council’s objectives are to reduce the gender gap across all government sectors, enhance the UAE’s ranking in global competitiveness reports on gender balance and promote gender balance in decision-making positions. |

References and Notes

Primary Sources

- Agreement on Facilitating and Developing Inter-Arab Trade: https://www.economy.gov.lb/public/uploads/files/3635_6707_7295.pdf, accessed on 20 May 2025.

- Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement between the Government of the Republic of India and the Government of the UAE https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/cepa_india, accessed on 22 May 2025.

- Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement between the Government of the United Arab Emirates and the Government of the Kingdom of Cambodia. https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/cepa_cambodia, accessed on 22 May 2025.

- Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement Between the Government of the United Arab Emirates and the Government of the Republic of Costa Rica. https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/uae-costa-rica-cepa, accessed on 22 May 2025.

- Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement Between the Government of the United Arab Emirates and the Government of the Republic of Indonesia. https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/cepa_indonesia, accessed on 21 May 2025.

- Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement Between the Government of the United Arab Emirates and the Government of the Republic of Serbia. https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/uae-serbia-cepa, accessed on 10 June 2025.

- Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement Between the Government of the United Arab Emirates and the Government of the State of Israel https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/cepa_israel, accessed on 22 May 2025.

- Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement Between the Republic of Mauritius and the United Arab Emirates. https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/cepa_mauritius, accessed on 22 May 2025.

- Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement between United Arab Emirates and Georgia. https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/uae-georgia-cepa, accessed on 22 May 2025.

- Free Trade Agreement Between the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf and the Republic of Singapore. https://www.moet.gov.ae/documents/20121/1478861/Singapore+-GCC+FTA-en.pdf, accessed on 15 May 2025.

- Free Trade Agreement Between the EFTA States and the Member States of the Co-Operation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf. https://www.moet.gov.ae/documents/20121/1478895/GCC-EFTA+FTA_en.pdf, accessed on 10 May 2025.

- GCC-Singapore Free Trade Agreement (GSFTA) Brief Guide https://www.moet.gov.ae/documents/20121/1478861/FTA+between+GCC+and+Republic+of+Singapore+booklet-en.pdf, accessed on 7 May 2025.

- The Free trade agreement between the Gulf Cooperation Council and the European Free Trade Association Quick Guide. https://www.moet.gov.ae/documents/20121/1478895/FTA+between+the+GCC+and+EFTA+Booklet-en.pdf, accessed on 5 May 2025.

- The UAE-Cambodia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement Handbook. https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/cepa_cambodia, accessed on 22 May 2025.

- The UAE-India Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement Handbook. https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/cepa_india, accessed on 22 May 2025.

- The UAE-Indonesia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement Handbook. https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/cepa_indonesia, accessed on 22 May 2025.

- The UAE-Israel Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement Handbook. https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/cepa_israel, accessed on 21 May 2025.

- The UAE-Türkiye Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement Handbook. https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/cepa_turkey, accessed on 22 May 2025.

- Türkiye-United Arab Emirates Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/cepa_turkey, accessed on 22 May 2025.

- US-Bahrain Free Trade Agreement. https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/bahrain-fta/final-text, accessed on 17 April 2025.

- US-Oman Free Trade Agreement: https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/oman-fta/final-text, accessed on 17 April 2025.

Secondary Sources

- Alesina, A., & Rodrick, D. (1994). Distributive politics and economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(2), 465–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab News. (2022). UAE unveils national plan to double GDP by 2031. Available online: https://arab.news/2ywfe (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Arabian Business. (2024, January 22). Women in UAE workplace: 23.1 Per cent private-sector surge; Wage equality, pregnancy and maternity laws explained. Available online: https://www.arabianbusiness.com/culture-society/women-in-uae-workplace-23-1-private-sector-surge-wage-equality-pregnancy-and-maternity-laws-explained (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Bahri, A. (2021). Gender mainstreaming in free trade agreements: A regional analysis and good practice examples. Gender, Social Inclusion and Trade Knowledge Product Series. Gender, Social Inclusion and Trade Working Group. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, M., & Yin, Z. (2024). Trade-gender alignment of international trade agreements: Insufficiencies and improvements. Journal of World Trade, 58(5), 807–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emirates News Agency (WAM). (2018, April 10). Mohammed bin rashid approves new law on equal pay. WAM—Emirates News Agency. Available online: https://www.wam.ae/en/article/hszr6uy9-mohammed-bin-rashid-approves-new-law-equal-pay (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Forbes Middle East. (2023, February 13). 100 most powerful businesswomen 2023. Forbes Middle East. Available online: https://www.forbesmiddleeast.com/lists/top-100-most-powerful-businesswomen-2023/ (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- General Secretariat of the Gulf Cooperation Council. (2024). Available online: https://www.gcc-sg.org/en-us/CooperationAndAchievements/Achievements/RegionalCooperationandEconomicRelationswithotherCountriesandGroupings/Pages/main.aspx (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Gulf Research Center. (2023). Gulf women in the workforce: Research paper. Gulf Research Center. Available online: https://www.grc.net/documents/643a0dd02a521GulfWomenintheWorkforceResearchPaper.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Gulf Time. (2023). UAE’s CEPA programmes break new ground in 2023. Gulf Time. Available online: https://gulftime.ae/uaes-cepa-programmes-break-new-ground-in-2023/ (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Hausmann, R., Tyson, L., & Zahidi, S. (2010). The Global Gender Gap Report 2010. World Economic Forum. [Google Scholar]

- International Trade Centre (ITC). (2015). Unlocking markets for women to trade. International Trade Centre. [Google Scholar]

- International Trade Centre (ITC). (2020). Mainstreaming gender in free trade agreements. ITC. Available online: https://www.intracen.org/resources/publications/mainstreaming-gender-in-free-trade-agreements (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Karam, F., & Zaki, C. (2024). When trade agreements are gender-friendly: Impact on women empowerment using firm data. Journal of Economic Integration, 39(4), 875–898. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27343220 (accessed on 10 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Luke, D. (2019). Gender considerations in FTAs, regional integration agreements and preferential trade schemes. Presentation by the Coordinator, African Trade Policy Centre, Economic Commission for Africa, at the WTO Workshop on Gender Considerations in Trade Agreements. Available online: https://unctad.org/meeting/gender-considerations-trade-agreements (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Monteiro, J.-A. (2018). Gender-related provisions in regional trade agreements. WTO Staff Working Paper ERSD-2018-15. WTO. Available online: https://www.wto-ilibrary.org/content/papers/25189808/269 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Plummer, M., Cheong, D., & Hamanaka, S. (2010). Methodology for impact assessment of free trade agreements. Asian Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Reuters. (2021). Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-emirates-companies-women/uae-listed-companies-must-have-at-least-one-female-board-member-regulator-idUSKBN2B71NI/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Saner, R., & Yiu, L. (2002). International economic diplomacy: Mutations in post-modern times. Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Vision 2030. (2023). Vision 2030 overview. Saudi Vision 2030. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/media/cofh1nmf/vision-2030-overview.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Simonetti, I. (2019, March 28). Gender considerations in Chile’s trade agreements. Presentation of the Head of Gender Department Directorate of International Economic Relations Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Chile at the WTO Workshop on Gender Considerations in Trade Agreements. Datos Económicos. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/non-official-document/SimonettiPresentation.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Supreme Council for Women. (n.d.). Gender balance center. Supreme Council for Women—Kingdom of Bahrain. Available online: https://www.scw.bh/en/category/gender-balance-center (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- The National. (2022, December 5). UAE seeks 22 CEPAs by 2031 as Ukraine trade talks start. The National. Available online: https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/economy/2022/12/05/uae-seeks-22-cepas-by-2031-as-ukraine-trade-talks-start (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- The National. (2023, February 18). UAE–India trade grows 10 % in the first year since CEPA deal was signed. The National. Available online: https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/economy/2023/02/18/uae-india-trade-grows-10-in-the-first-year-since-cepa-deal-was-signed/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- UAE Government Portal. (2024a). Gender equality: Gender balance. Women|The Official Portal of the UAE Government. Available online: https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/social-affairs/gender-equality/gender-balance (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- UAE Government Portal. (2024b). Principles of the 50. The Official Portal of the UAE Government.

- UAE Government Portal. (2024c). UAE gender balance council strategy 2026. The Official Portal of the UAE Government.

- UAE Ministry of Economy and Tourism. (2025). Comprehensive Economic partnership agreements. Ministry of Economy—UAE. Available online: https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/cepa (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- UNCTAD. (2017). Trade and gender toolbox. United Nations conference on trade and development DITC 2017/1. UNCTAD Trade and Gender Tool Box. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. (2023). Compilation guidelines for measurement of gender-in-trade statistics. Pilot testing methodologies. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/stat2023d2_en.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- United Arab Emirates Embassy (Washington, D.C.). (n.d.). Women in the UAE. UAE Embassy in Washington, D.C. Available online: https://www.uae-embassy.org/discover-uae/society/women-in-the-uae (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- United Kingdom Department for Business and Trade. (2024, February 19). Trade update: UK–Gulf cooperation council FTA negotiations. GOV.UK. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/trade-update-uk-gulf-cooperation-council-fta-negotiations (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Vanhee, T. (2024). CEPAs and FTAs: Exploring new partnership agreements by UAE and GCC countries. Available online: https://aurifer.tax/cepas-and-ftas-exploring-new-partnership-agreements-by-uae-and-gcc-countries/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- World Economic Forum. (2024). Global gender gap report. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2024.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- World Trade Organisation. (2017). Joint declaration on trade and women’s economic empowerment on the occasion of the WTO ministerial conference in Buenos Aires in December 2017. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/mc11_e/genderdeclarationmc11_e.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

| Region/Continent | # of Mentions | Scope | Coverage | Format |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Union | 160 | Commitments to act, acknowledgements and reaffirmations | Equality, non-discrimination, education, skill development, health and safety, maternal care | Mix of binding and non-binding commitments; in main text and annex |

| North America | 148 | Reaffirmations and cooperation-based provisions | Labour concerns, resource access, market and technology, participation in economic growth | Mostly non-binding commitments, in main text and annex, side agreements and preamble |

| Africa | 101 | Commitments to act, reaffirmations | Access to resources, entrepreneurship, representation in decision-making positions | Mix of binding and non-binding commitments, in main text, annex, complementary instruments |

| South America | 87 | Reaffirmations and cooperation-based provisions | Labour, market access, resource access, women’s role in growth and development, childcare | Mostly non-binding commitments, in main text and annex |

| Asia–Pacific | 66 | Right to regulate provisions; reservations | Healthcare, nutrition, child care, maternity and women’s safety | Mostly binding commitments, in main text and annex |

| Country/Group | Date | Status of Negotiations |

|---|---|---|

| European Union | 1991 | Suspended in 2008 |

| Arab countries | March 2001 | GAFTA signed in 2005 |

| EFTA | February 2006 | Agreement signed in June 2009 |

| Mercosur | October 2006 | Meetings held, pending |

| Japan | 1987 | Six rounds completed, pending |

| Lebanon | n/a | Agreement signed in 2004 |

| Syria | n/a | Initial agreement signed, final form pending |

| Pakistan | August 2004 | Preliminary signature in September 2023 |

| India | August 2004 | Two rounds completed, pending |

| China | April 2005 | Last round held in 2009, negotiations September 2024 |

| Türkiye | May 2005 | Four rounds completed, negotiations resumed in 2024 |

| New Zealand | December 2006 | Several rounds completed, initial agreement signed in October 2009, final form pending with negotiations concluded in October 2024 |

| Singapore | January 2007 | Agreement signed in December 2008 |

| South Korea | May 2007 | Two rounds completed, negotiations concluded in December 2023 |

| Australia | May 2007 | Several rounds completed, pending |

| Malaysia | February 2011 | Preliminary discussions, negotiations resumed in May 2025 |

| UK | June 2022 | Signature expected in 2025 |

| Indonesia | September 2024 | Negotiations started |

| Country | Date Signed | Date Entered into Force |

|---|---|---|

| India | 18 February 2022 | 1 May 2022 |

| Israel | 31 May 2022 | 1 April 2023 |

| Indonesia | 1 July 2022 | 1 September 2023 |

| Türkiye | 3 March 2023 | 1 September 2023 |

| Cambodia | 8 June 2023 | 25 January 2024 |

| Georgia | 10 October 2023 | 27 June 2024 |

| Costa Rica | 17 April 2024 | 1 April 2025 |

| Mauritius | 22 July 2024 | 1 April 2025 |

| Jordan | 6 October 2024 | 15 May 2025 |

| Serbia | 5 October 2024 | 1 June 2025 |

| Agreement | Agreement Provisions | Handbook Provisions |

|---|---|---|

| UAE-India Signed 18 February 2022 Entered into force 1 May 2022 | CHAPTER 13: MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES Article 13.2: Cooperation to Increase Trade and Investment Opportunities for SMEs With a view to more robust cooperation between the Parties to enhance commercial opportunities for SMEs, each Party shall seek to increase trade and investment opportunities, and in particular shall: […] (b) strengthen collaboration with the other Party on activities to promote SMEs owned by women and youth, as well as start-ups, and promote partnerships among these SMEs and their participation in international trade; […] ARTICLE 13.4 Committee on SME Issues 1. The Parties shall establish the Committee on SME Issues (SME Committee) comprising representatives of each Party. 2. The SME Committee shall: […] (l) facilitate the exchange of information on entrepreneurship education and awareness programs for youth and women to promote the entrepreneurial environment in the territories of the Parties; […] | n/a |

| UAE-Israel Signed 31 May 2022 Ratified 1 April 2023 | CHAPTER 13: SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES Article 13.2: Cooperation to Increase Trade and Investment Opportunities for SMEs With a view to more robust cooperation between the Parties to enhance commercial opportunities for SMEs, the Parties may: […] (b) collaborate on activities to promote SMEs owned by women and their participation in international trade […] | Strengthens cooperation to enhance commercial opportunities for SMEs by: ▷ Encouraging collaboration on activities to promote women-owned SMEs and their participation in international trade |

| UAE-Indonesia Signed 1 July 2022 Ratified 1 September 2023 | CHAPTER 13: SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES Article 13.2: Cooperation 1. The Parties shall strengthen their cooperation under this Chapter, which may include: […] (b) strengthening their collaboration on activities to promote SMEs owned by women and youth, as well as start-ups, and […] | Strengthens cooperation between dedicated SMEs centres, incubators and accelerators, export assistance centres, SMEs owned by youth and women and start-ups |

| UAE-Türkiye Signed 3 March 2023 Ratified 1 September 2023 | CHAPTER 13: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY SECTION 13-B: COOPERATION ARTICLE 13.8: Cooperation Activities and Initiatives The Parties shall endeavour to cooperate on the subject matter covered by this Chapter, such as through appropriate coordination, training and exchange of information between their respective intellectual property offices, or other institutions, as determined by each Party. Cooperation activities and initiatives undertaken under this Chapter shall be subject to the availability of resources, upon request, and on terms and conditions mutually agreed upon between the Parties. Cooperation may cover areas such as: [….] (d) intellectual property issues relevant to: […] and (iv) empowering women and youth; CHAPTER 15: SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES ARTICLE 15.2: Cooperation to Increase Trade and Investment Opportunities for SMEs With a view to more robust cooperation between the Parties to enhance commercial opportunities for SMEs, each Party shall seek to increase trade and investment opportunities, and in particular shall: […] (b) strengthen its collaboration with the other Party on activities to promote SMEs owned by women and youth, as well as start-ups, and promote partnership among these SMEs and their participation in international trade […] | Strengthens cooperation to enhance commercial opportunities for SMEs by: ▷ Encouraging collaboration on activities to promote women-owned SMEs and their participation in international trade |

| UAE-Cambodia Signed 8 June 2023 Ratified 25 January 2024 | CHAPTER 10: INVESTMENT ARTICLE 10.4: Responsible Business Conduct 3: Each Party recognises the importance of Investors and enterprises implementing due diligence in order to identify and address adverse impacts, such as on the environment and labour conditions, in their operations, their supply chains and other business relationships. […] ARTICLE 10.5. Non-derogation of Health, Safety and Environmental Measures 3: The parties reaffirm the right of each Party to regulate within its territory to achieve legitimate policy objectives, such as with respect to the protection of the environment and addressing climate change; social or consumer protection; or the promotion and protection of health, safety, gender equality, and cultural diversity. CHAPTER 11: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY SECTION B: COOPERATION ARTICLE 11.11: Cooperation Activities and Initiatives The Parties shall endeavour to cooperate on the subject matter covered by this Chapter, such as through appropriate coordination, training and exchange of information between their respective intellectual property offices, or other institutions, as determined by each Party. Cooperation activities and initiatives undertaken under this Chapter shall be subject to the availability of resources, upon request, and on terms and conditions mutually agreed upon between the Parties. Cooperation may cover areas such as: [….] (d) intellectual property issues relevant to: […] (iv) empowering women and youth. CHAPTER 12: SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES ARTICLE 12.2: Cooperation to Increase Trade and Investment Opportunities for SMEs With a view to more robust cooperation between the Parties to Enhance commercial opportunities for SMEs, each Party shall seek to increase trade and investment opportunities, and in particular shall: […] (b) strengthen its collaboration with the other Party on activities to promote SMEs owned by women and youth, as well as start-ups, and promote partnerships among these SMEs and their participation in international trade. ARTICLE 12.4: Sub-Committee on SME Issues 2. The SME Sub-Committee shall: […] (l) facilitate the exchange of information on entrepreneurship education and awareness programs for youth and women to promote entrepreneurial environment in the territories of the Parties; | n/a |

| UAE-Georgia Signed 10 October 2023 Ratified 27 June 2024 | CHAPTER 11: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY SECTION B: COOPERATION ARTICLE 11.11: Cooperation Activities and Initiatives The Parties shall endeavour to cooperate on the subject matter covered by this Chapter, such as through appropriate coordination, training and exchange of information between their respective intellectual property offices, or other institutions, as determined by each Party. Cooperation activities and initiatives undertaken under this Chapter shall be subject to the availability of resources, upon request, and on terms and conditions mutually agreed upon between the Parties. Cooperation may cover areas such as: [….] (d) intellectual property issues relevant to: […] (iv) empowering women and youth. CHAPTER 13: SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES ARTICLE 13.2: Cooperation to Increase Trade and Investment Opportunities for SMEs With a view to more robust cooperation between the Parties to Enhance commercial opportunities for SMEs, each Party shall seek to increase trade and investment opportunities, and in particular shall endeavour to: […] (b) strengthen its collaboration with the other Party on activities to promote SMEs owned by women and youth, as well as start-ups, and promote partnerships among these SMEs and their participation in international trade. | Handbook not published. |

| UAE-Mauritius Signed 17 April 2024 Ratified 1 April 2025 | CHAPTER 10: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY SECTION B: COOPERATION ARTICLE 10.11: Cooperation Activities and Initiatives The Parties shall endeavour to cooperate on the subject matter covered by this Chapter, such as through appropriate coordination, training and exchange of information between their respective intellectual property offices, or other institutions, as determined by each Party. Cooperation activities and initiatives undertaken under this Chapter shall be subject to the availability of resources, and on request, and on terms and conditions mutually agreed upon between the Parties. Cooperation may cover areas such as: [….] (d) intellectual property issues relevant to: […] (iv) empowering women and youth. CHAPTER 14: SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES ARTICLE 14.2: Cooperation to Increase Trade and Investment Opportunities for SMEs With a view to more robust cooperation between the Parties to enhance commercial opportunities for SMEs, each Party shall seek to increase trade and investment opportunities, and in particular shall: […] (b) strengthen its collaboration with the other Party on activities to promote SMEs owned by women and youth, as well as start-ups, and promote partnerships among these SMEs and their participation in international trade; and […] ARTICLE 14.4: Sub-Committee on SME Issues 2. The SME Sub-Committee shall: […] (l) facilitate the exchange of information on entrepreneurship education and awareness programs for youth and women to promote entrepreneurial environment in the territories of the Parties; | Handbook not published. |

| UAE-Costa Rica Signed 22 July 2024 Ratified 1 April 2025 | CHAPTER 12: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY SECTION B: COOPERATION ARTICLE 12.11: Cooperation Activities and Initiatives The Parties shall endeavour to cooperate on the subject matter covered by this Chapter, such as through appropriate coordination, training and exchange of information between their respective intellectual property offices, or other institutions, as determined by each Party. Cooperation activities and initiatives undertaken under this Chapter shall be subject to the availability of resources, and on request, and on terms and conditions mutually agreed upon between the Parties. Cooperation may cover areas such as: [….] (d) intellectual property issues relevant to: […] (iv) empowering women and youth. CHAPTER 13: SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES ARTICLE 13.2: Cooperation to Increase Trade and Investment Opportunities for SMEs With a view to more robust cooperation between the Parties to enhance commercial opportunities for SMEs, each Party shall seek to increase trade and investment opportunities, and in particular shall: […] (b) strengthen its collaboration with the other Party on activities to promote SMEs owned by women and youth, as well as start-ups, and promote partnerships among these SMEs and their participation in international trade; […] ARTICLE 13.4: Sub-Committee on SME Issues 2. The Sub-Committee may consider any matter arising under this Chapter. The functions of the Subcommittee shall include: […] (l) facilitate the exchange of information on entrepreneurship education and awareness programs for youth and women to promote entrepreneurial environment in the territories of the Parties; | Handbook not published. |

| UAE-Serbia Signed 5 October 2024 Ratified 1 June 2025 | CHAPTER 11: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY SECTION B: COOPERATION ARTICLE 11.11: Cooperation Activities and Initiatives The Parties shall endeavour to cooperate on the subject matter covered by this Chapter, such as through appropriate coordination, training and exchange of information between their respective intellectual property offices, or other institutions, as determined by each Party. Cooperation activities and initiatives undertaken under this Chapter shall be subject to the availability of resources, upon request, and on terms and conditions mutually agreed upon between the Parties. Cooperation may cover areas such as: [….] (e) intellectual property issues relevant to: […] (iv) empowering women and youth. CHAPTER 13: SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES ARTICLE 13.2: Cooperation to Increase Trade and Investment Opportunities for SMEs With a view to more robust cooperation between the Parties to enhance commercial opportunities for SMEs, each Party shall seek to increase trade and investment opportunities, and in particular shall: […] (b) strengthen its collaboration with the other Party on activities to promote SMEs owned by women and youth, as well as start-ups, and promote partnerships among these SMEs and their participation in international trade; […] ARTICLE 13.4: Sub-Committee on SME Issues 2. The Sub-Committee shall: […] (l) facilitate the exchange of information on entrepreneurship education and awareness programs for youth and women to promote entrepreneurial environment in the territories of the Parties; | Handbook not published. |

| GCC (amended) Adopted on 31 December 2001 | CHAPTER FIVE: DEVELOPMENT OF HUMAN RESOURCES Article 13: Population Strategy Member States shall implement the “General Framework of Population Strategy of the GCC States”, adopt the policies necessary for the development of human resources and their optimal utilization, provision of health care and social services, enhancement of the role of women in development, and the achievement of balance in the demographic structure and labor force to ensure social harmony in Member States, emphasize their Arab and Islamic identity, and maintain their stability and solidarity. | Handbook not published. |

| GAFTA | n/a | Handbook not published. |

| GCC-Singapore | n/a | n/a |

| GCC-EFTA | n/a (Preamble reaffirms the Universal Declaration of Human Rights) | n/a |

| Bahrain-USA | ANNEX 15-A: LABOR COOPERATION MECHANISM Cooperative Activities Article 4: The Parties may undertake cooperative activities through the Labor Cooperation Mechanism on any labor matter they consider appropriate, including: […] (f) gender-related issues: elimination of discrimination with respect to employment and occupation and other gender-related issues; (Chapter 15 reaffirms the International Labour Organisation’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its Follow-up) | Handbook not published. |

| Oman-USA | n/a (Chapter 16 reaffirms the International Labour Organisation’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its Follow-up) | Handbook not published. |

| Dimension | UAE– India | UAE – Indonesia | UAE–Israel | UAE– Türkiye | UAE– Cambodia | UAE– Georgia | UAE– Mauritius | UAE– Costa Rica | UAE– Serbia | GAFTA | GCC– Singapore | GCC–EFTA | Bahrain–USA | Oman–USA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Frequency of relevant provisions | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| 2. Location of relevant provisions | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| 3. Affirmations and reaffirmations | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| 4. Cooperation activities | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| 5. Institutional arrangements | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| 6. Procedural arrangements | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| 7. Review and funding | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| 8. Settlement of disputes | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| 9. Waivers, reservations, and exceptions | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| 10. Minimum legal standards | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Limited Responsiveness | |||||||||||||||||

| Evolving Responsiveness | |||||||||||||||||

| Advanced Responsiveness | |||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakardzhieva, D.; Chehab, S. Promoting Women’s Economic Empowerment Through Economic Diplomacy: The Case of the Arab Gulf’s Free Trade Agreements. Economies 2025, 13, 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100290

Bakardzhieva D, Chehab S. Promoting Women’s Economic Empowerment Through Economic Diplomacy: The Case of the Arab Gulf’s Free Trade Agreements. Economies. 2025; 13(10):290. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100290

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakardzhieva, Damyana, and Sara Chehab. 2025. "Promoting Women’s Economic Empowerment Through Economic Diplomacy: The Case of the Arab Gulf’s Free Trade Agreements" Economies 13, no. 10: 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100290

APA StyleBakardzhieva, D., & Chehab, S. (2025). Promoting Women’s Economic Empowerment Through Economic Diplomacy: The Case of the Arab Gulf’s Free Trade Agreements. Economies, 13(10), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100290