Evolution and Theoretical Implications of the Utility Concept

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Framework

3. Evolution of the Utility Concept

4. Utility Approaches

4.1. Dual Utility and Its Influence on Utilitarianism and Consequentialism

4.2. Outcome and Procedural Utility

4.3. Hedonic and Instrumental Utility

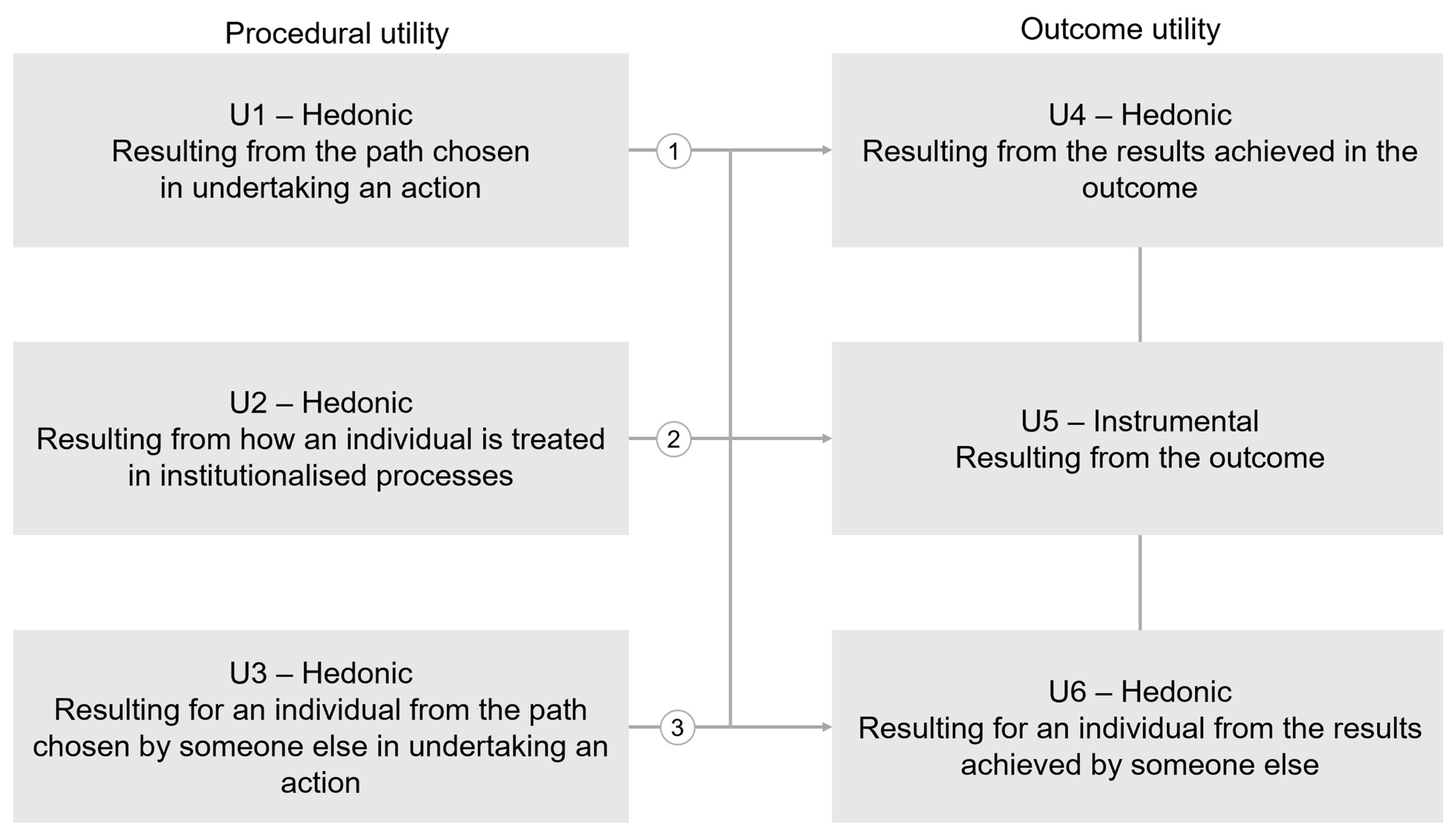

- PU arises from the method selected to act, as outlined in Figure 3 (U1). Consider the task of lawn mowing: an individual can either perform the task personally or outsource it, e.g., pay for a garden maintenance service. If the individual experiences procedural pleasure from undertaking the task, they will likely choose to mow their lawn. Conversely, if the HU derived from this personal involvement is negative, the individual will evaluate the cost of purchasing the service.

- IU from the outcome achieved. This corresponds to the IU described in Figure 3 (U5), which is obtained through the goods acquired in that outcome. For example, purchasing a new car provides material benefit through its use for commuting to work and during leisure time.

- HU from the outcome represents the psychological well-being in Figure 3 (U4). For instance, if a new car is a desired sophisticated sports model, its possession provides significant satisfaction while the same does not apply if you can only afford a second-hand economy car that is barely functional.

5. Procedural Utility

5.1. Procedural Utility in Individual Actions

5.2. Procedural Utility in Interpersonal Relationships

5.3. Intersubjective Procedural Utility as Communicative Utility

- The non-communicative use of knowledge to achieve individual or collective material goals;

- The communicative use of knowledge to achieve a shared understanding of interpreting reality.

5.4. Language-Based Preferences

5.5. Procedural Utility in Institutionalised Processes

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achime, N. H. (1990). Book review: Human desire and economic satisfaction. Review of Radical Political Economics, 22(2–3), 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, M. D., Dolan, P., & Kavetsos, G. (2017). Would you choose to be happy? Tradeoffs between happiness and the other dimensions of life in a large population survey. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 139, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angner, E. (2011). Are subjective measures of well-being ‘direct’? Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 89(1), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batley, R. (2007). On ordinal utility, cardinal utility and random utility. Theory and Decision, 64(1), 37–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becattini, G. (2018). Pantaleoni, maffeo (18571924) (pp. 10009–10010). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentham, J. (1996). The collected works of Jeremy Bentham: An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation (J. H. Burns, & H. L. A. Hart, Eds.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaug, M. (1993). The meaning of the market process: Essays in the development of modern Austrian economics. The Economic Journal, 103(418), 757–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, S. J., Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., & Sevilla, A. (2024). Parental time investments and instantaneous well-being in the United States. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 72(1), e12402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, J. (2018). Libertarianism after Nozick. Philosophy Compass, 13(2), e12485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, T. J. (1989). A methodological assessment of multiple utility frameworks. Economics and Philosophy, 5(2), 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broome, J. (1991). “Utility”. Economics and Philosophy, 7(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, H. J. (1989). Human desire and economic satisfaction. Tibor scitovsky. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 37(2), 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelen, A. W., Moene, K. O., Sørensen, E. Ø., & Tungodden, B. (2013). Needs versus entitlements-an international fairness experiment. Journal of the European Economic Association, 11(3), 574–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capraro, V., Di Paolo, R., Perc, M., & Pizziol, V. (2024a). Language-based game theory in the age of artificial intelligence. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 21(212), 20230720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capraro, V., Halpern, J. Y., & Perc, M. (2024b). From outcome-based to language-based preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 62(1), 115–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colander, D. (2007). Retrospectives: Edgeworth’s hedonimeter and the quest to measure utility. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(2), 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, D., & Sen, A. (1984). Choice, welfare and measurement. The Economic Journal, 94(374), 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A., Vives, M., & Corey, J. D. (2017). On language processing shaping decision making. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(2), 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremaschi, S. (2004). Ricardo and the utilitarians. The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 11(3), 377–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Crespo, R. F. (2020). On money as a conventional sign: Revisiting Aristotle’s conception of money. Journal of Institutional Economics, 17(3), 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziechciarz, M. (2024). Panel data analysis of subjective well-being in European countries in the years 2013–2022. Sustainability, 16(5), 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R. A. (2004). The economics of happiness. Daedalus, 133(2), 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, M., Alexandrova, A., Coyle, D., Agarwala, M., & Felici, M. (2022). Respecting the subject in wellbeing public policy: Beyond the social planner perspective. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(8), 1494–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, A., Becker, A., Dohmen, T., Enke, B., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2018). Global evidence on economic preferences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(4), 1645–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatas, E., Hargreaves Heap, S. P., & Rojo Arjona, D. (2018). Preference conformism: An experiment. European Economic Review, 105, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausto, D. (2008). The Paretian school of thought in Italy. History of Economics Review, 48(1), 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flux, A. W., Pantaleoni, M., & Bruce, T. B. (1898). Pure economics. The Economic Journal, 8(31), 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B. S. (2004). Beyond outcomes: Measuring procedural utility. Oxford Economic Papers, 57(1), 90–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2000). Happiness, economy and institutions. The Economic Journal, 110(466), 918–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, K. T., & Todres, L. (2011). Kinds of well-being: A conceptual framework that provides direction for caring. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 6(4), 10362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamal, Y., Pinto, N., & Iossifova, D. (2023). The role of procedural utility in land market dynamics in greater Cairo: An agent based model application. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 51(4), 954–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, O. (2024). Utility under the dark tetrad. Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, 30(59), 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, F. (1982). On some difficulties of the utilitarian economist (pp. 187–198). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hands, D. W. (2014). Paul Samuelson and revealed preference theory. History of Political Economy, 46(1), 85–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslett, D. W. (1990). What is utility? Economics and Philosophy, 6(1), 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, L. W., Knight, T., & Richardson, B. (2013). An exploration of the well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic behaviour. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(4), 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houthakker, H. S. (1950). Revealed preference and the utility function. Economica, 17(66), 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V. (2016). Eudaimonic and hedonic orientations: Theoretical considerations and research findings (pp. 215–231). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshanloo, M., Jovanović, V., & Park, J. (2020). Differential relationships of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being with self-control and long-term orientation1. Japanese Psychological Research, 63(1), 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (2011). Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking (pp. 252–270). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Krueger, A. B. (2006). Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminitz, S. C. (2017). Contemporary procedural utility and Hume’s early idea of utility. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(1), 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, I., & Assor, A. (2006). When choice motivates and when it does not. Educational Psychology Review, 19(4), 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjosavik, D. J. (2003). Methodological individualism and rational choice in neoclassical economics: A review of institutionalist critique. Forum for Development Studies, 30(2), 205–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layard, R., Mayraz, G., & Nickell, S. (2008). The marginal utility of income. Journal of Public Economics, 92(8–9), 1846–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, P. C. (2016). Economic evaluations, procedural fairness, and satisfaction with democracy. Political Research Quarterly, 69(3), 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, N., & Rendon Teresa, H. (2006). A hermeneutic of Amartya Sen’s concept of capability. International Journal of Social Economics, 33(10), 710–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLure, M. (2000). The Pareto-Scorza polemic on collective economic welfare. Australian Economic Papers, 39(3), 347–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLure, M. (2008). Vilfredo pareto, 1906 Manuale di economia politica, Edizione Critica, Aldo Montesano, Alberto Zanni and Luigino Bruni (eds), (Milan: EGEAUniversità bocconi editore, 2006) pp. XXII, 706, $66. ISBN 88-8350-084-9. Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 30(1), 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mill, J. S. (2010). The principles of political economy. In The Two Narratives of Political Economy (pp. 295–344). Scrivener Publishing LLC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millgram, E. (2000). What’s the use of utility? Philosophy & Public Affairs, 29(2), 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscati, I. (2013). Were Jevons, Menger, and Walras really cardinalists? On the notion of measurement in utility theory, psychology, mathematics, and other disciplines, 1870–1910. History of Political Economy, 45(3), 373–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, M. (2016). Minding the happiness gap: Political institutions and perceived quality of life in transition. European Journal of Political Economy, 45, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancheva, M. G., Ryff, C. D., & Lucchini, M. (2020). An integrated look at well-being: Topological clustering of combinations and correlates of hedonia and eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(5), 2275–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M. C., Coelho, F., & Silva, G. M. (2023). Is there a happy culture? Multiple paths to national subjective well-being. Kyklos, 76(4), 613–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramrattan, L., & Szenberg, M. (2021). Introduction and general overview of economic happiness (pp. 1–16). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, D. (2014). On the principles of political economy, and taxation. Cambridge University Press (CUP). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A., & Sraffa, P. (1951). The works and correspondence of David Ricardo. Volume i: On the principles of political economy and taxation. The Economic Journal, 61(244), 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, W. J. (1992). Edgeworth’s mathematical psychics: A centennial notice (pp. 167–175). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, B., & Cheek, N. N. (2017). Choice, freedom, and well-being: Considerations for public policy. Behavioural Public Policy, 1(1), 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seigel, J. E., Napoleoni, C., & Gee., J. M. A. (1977). Smith, Ricardo, Marx. The American Historical Review, 82(1), 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, A., & Nedeljković, Z. (2023). Three concepts of happiness: From ancient Greece to modern sciences. Politea, 13(26), 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. (1991). Utility: Ideas and terminology. Economics and Philosophy, 7(2), 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. (2006). Reason, freedom and well-being. Utilitas, 18(1), 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, M., & Kim, Y. (2022). Hedonic consumption and consumer’s choice under the windfall gains. Journal of Korea Society of Industrial Information Systems, 27(2), 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, A., & Li, H. (2021). How do utilitarian versus hedonic products influence choice preferences: Mediating effect of social comparison. Psychology & Marketing, 38(8), 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shizgal, P. (2012). Scarce means with alternative uses: Robbins’ definition of economics and its extension to the behavioral and neurobiological study of animal decision making. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidgwick, H. (2011). The methods of ethics. Cambridge University Press (CUP). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyrms, B., & Narens, L. (2018). Measuring the hedonimeter. Philosophical Studies, 176(12), 3199–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnabend, H. (2016). Fairness constraints on profit-seeking: Evidence from the German club concert industry. Journal of Cultural Economics, 40(4), 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, G. R. (2006). Richard Layard’s happiness: Worn philosophy, weak psychology, wrong method and just plain bad economics! The Political Quarterly, 77(4), 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutzer, A., & Frey, B. S. (2006). Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? The Journal of Socio-Economics, 35(2), 326–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H., & Phillips, R. G. (2018). Indicators and community well-being: Exploring a relational framework. International Journal of Community Well-Being, 1(1), 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K., & Demircioglu, M. A. (2020). Is impartiality enough? Government impartiality and citizens’ perceptions of public service quality. Governance, 34(3), 727–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A., Cafiero, C., & Montibeller, M. (2016). Pareto efficiency, the Coase theorem, and externalities: A critical view. Journal of Economic Issues, 50(3), 872–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, A., Costa, A., & Foucart, A. (2021). Are our preferences and evaluations conditioned by the language context? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 45(2), 408–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigliarolo, F. (2020). Towards an ontological reason law in economics: Principles and foundations. Insights into Regional Development, 2(4), 784–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winfrey, J. C. (1993). Derailing value theory: Adam smith and the Aristotelian tradition. Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 15(2), 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, U. (2016). The transformations of utility theory: A behavioral perspective. Journal of Bioeconomics, 18(3), 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, L. (2018). Measuring well-being: A multidimensional index integrating subjective well-being and preferences. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 19(4), 456–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | IU | HU | IU | HU |

| Goods with only IU | >0 | =0 | Effective drug with no hedonic impact | Value based solely on functionality |

| Goods with only HU | =0 | >0 | Non-functional collectable car, rare stamp | No instrumental function |

| Positive IU, negative HU | >0 | <0 | Effective but unpleasant medicine with side effects | Hedonic discomfort reduces overall value |

| Negative IU, positive HU | <0 | >0 | Harmful but tasty foods, alcohol, drugs, smoking, reckless driving | Subjective pleasure outweighs potential objective harm |

| Domain | Agent(s) | Source of Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Individual action | Same subject | Autonomy, freedom, capacity, direct involvement |

| Interpersonal relationship | Self and other individual | Communicative interaction, mutual recognition, dialogic exchange, exchanges of goods outside the market mechanism |

| Institutionalised processes | Individual and institution | Fairness, transparency, participation, procedural justice |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Foggia, G.; Arrigo, U.; Beccarello, M. Evolution and Theoretical Implications of the Utility Concept. Economies 2025, 13, 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100283

Di Foggia G, Arrigo U, Beccarello M. Evolution and Theoretical Implications of the Utility Concept. Economies. 2025; 13(10):283. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100283

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Foggia, Giacomo, Ugo Arrigo, and Massimo Beccarello. 2025. "Evolution and Theoretical Implications of the Utility Concept" Economies 13, no. 10: 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100283

APA StyleDi Foggia, G., Arrigo, U., & Beccarello, M. (2025). Evolution and Theoretical Implications of the Utility Concept. Economies, 13(10), 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100283