The Tariff Liberalisation Policy Nexus with Non-Tariff Measures: Panel Model Evidence in the SA–EU Fruit Products Trade

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Gap Identified Through Literature

2. Literature

2.1. Brief Institutional Background and Policy Environment of SA–EU Fruits Products Trade

2.2. Brief Theoretical and Empirical Literature

2.3. Conceptual Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Variables Selection

3.2. Description of the Data Used

3.3. Model Specification and Estimation

3.3.1. Time Series Properties of the Data

3.3.2. Pre-Testing of Data and Model Suitability

3.3.3. Specified Empirical Model

4. Results

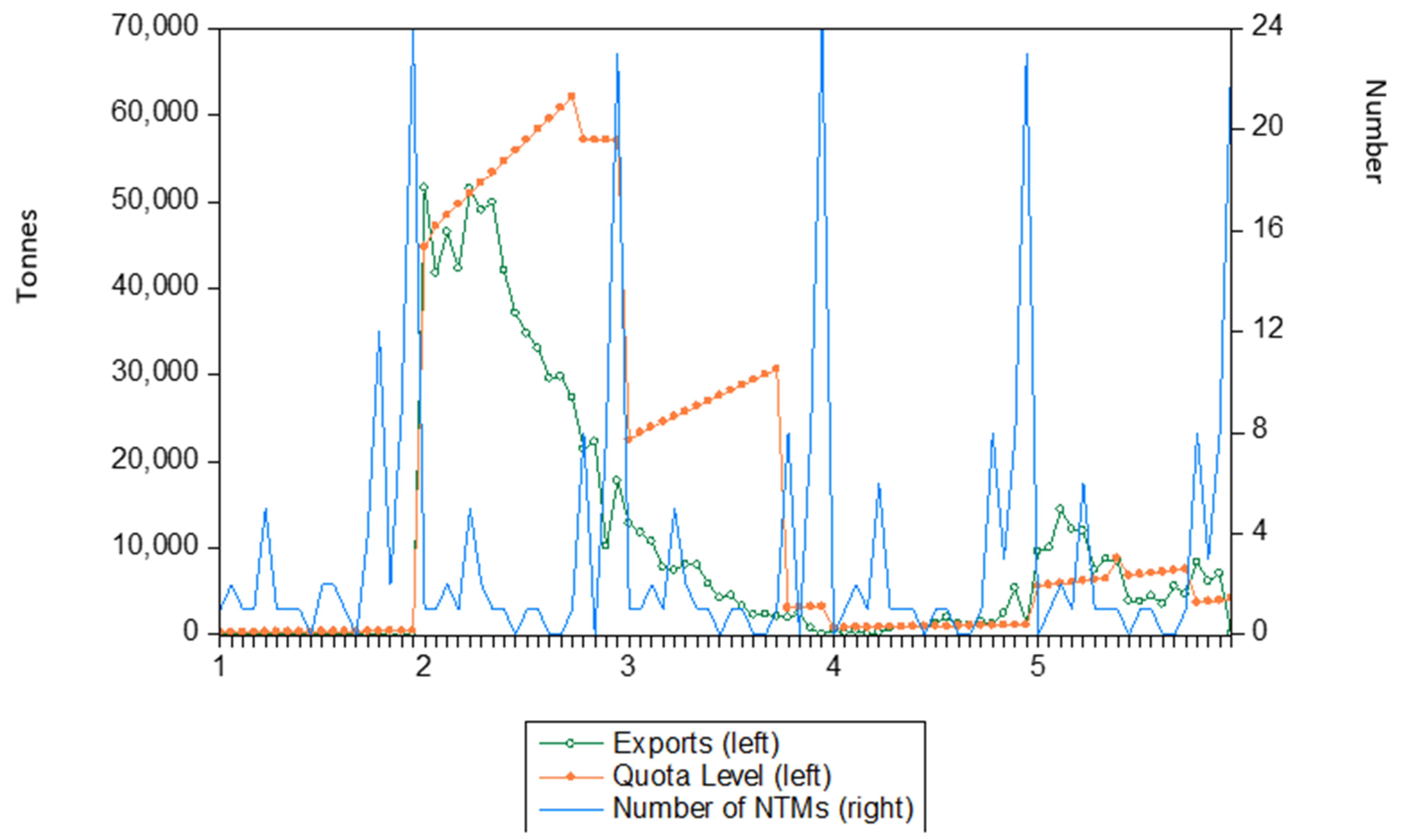

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Graphical Representation of the Data

4.2. Panel Model Regression Results

Discussion of Results Including Policy Implications

4.3. Test of the Validity of the Fixed Effects

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbot, P. (2002). Tariff-rate quotas: Failed market access instrument. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 9(1), 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S. (2015). Trade liberalization. In Palgrave dictionary of emerging markets and transition economics (pp. 393–412). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ajewole, K., Beckman, J., Gerval, A., Johnson, W., Morgan, S., & Sabala, E. (2022). Do Free Trade Agreements Benefit Developing Countries? An Examination of US Agreements (No. 329076). United States Department of Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman, J., Gale, F., & Lee, T. (2021). Agricultural market access under tariff-rate quotas (No. 1473-2021-046). Economic Research Service. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/308595/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Bellmann, C., & Sugathan, M. (2022). Promoting and Facilitating trade in environmental goods and services: Lessons from regional trade agreements. Forum on Trade, Environment & SDGs (TESS). Available online: https://tessforum.org/media/2022/06/TESS-Technical-Paper-Promoting-and-Facilitating-Environmental-Goods-and-Services-2.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Berden, K. G., Francois, J., Tamminen, S., Thelle, M., & Wymenga, P. (2009). Non-Tariff Measures in EU-US Trade and Investment—An Economic Analysis. Rotterdam, ECORYS Nederland BV. Available online: http://tracker.borderlex.eu/doc/674/European%20Commission%20Analysis%20on%20Non-Tariff%20Measures%20in%20the%20EU-US%20Economic%20Analysis.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Binkley, J. K., & Young, J. S. (2023). The chow test with time series-cross section data. Journal of Statistical and Econometric Methods, 12(1), 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, J. C., & Tangermann, S. (2000). Tariff rate quotas in the EU. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 29(1), 31327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., Villoria, N. B., & Xia, T. (2020). Tariff quota administration in China’s grain markets: An empirical assessment. Agricultural Economics, 51(2), 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, D. C., & Sheldon, I. (2024). The United States’ challenge(s) to Canada’s dairy import tariff rate quotas: What is all the fuss about? Ohio State Legal Studies Research Paper, No. 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipollina, M., & Demaria, F. (2020). The trade effect of the EU’s preference margins and non-tariff barriers. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(9), 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirera, X., Foliano, F., & Gasiorek, M. (2016). The impact of preferences on developing countries’ exports to the European Union: Bilateral gravity modelling at the product level. Empirical economics, 50, 59–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delev, C. (2023). Regulating TRQ schemes under WTO law: Time to throw away old bananas? Journal of World Trade, 57(3), 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, J., & Shepherd, B. (2018). The economics of non-tariff measures: A primer. FERDI Working Paper, No. P212. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/269493/1/ferdi-wp212.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Dolabella, M. (2020). Bilateral effects of non-tariff measures on international trade: Volume-based panel estimates. International Trade series, No. 155 (LC/TS.2020/107), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Available online: https://repository.eclac.org/handle/11362/46014 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- European Commission. (2018). Individual Reports and Info Sheets on Implementation of EU Free Trade Agreements. SWD (2018) 454 final. Available online: https://www.eumonitor.nl/9353000/1/j9vvik7m1c3gyxp/vkt385i3c8y2 (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- European Commission. (2021). Individual information sheets on implementation of EU Trade Agreements. SWD (2021) 297 final. Available online: https://www.astrid-online.it/static/upload/trad/tradoc_159786.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- European Commission. (2022a). Individual information sheets on implementation of EU Trade agreements. SWD (2022) 730 final. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/documents-register/api/files/SWD(2022)730_0/090166e5f258a919?rendition=false (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- European Commission. (2022b). FAQ on preference utilisation rates (PUR), duty savings and tariff rate quotas (TRQ). Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/7fc51410-46a1-4871-8979-20cce8df0896/library/7765b74a-b251-4eda-9533-99c046769e63/details (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Fall, F., & Langle, K. (2020). Trade liberalisation and product mix adjustments: Evidence from South African firms. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/trade-liberalisation-and-product-mix-adjustments-evidence-from-south-african-firms_f8499821-en (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Fathelrahman, E., Osman, R., Hoag, D. L. K., Sixt, G. N., & Strzepek, K. (2024). Bilateral trade welfare impacts of India’s export ban of non-basmati rice using the Global Partial Equilibrium Simulation Model (GSIM). Foods, 13(19), 3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, N. (2023). Dairy concessions in Canadian trade: A discursive institutionalist account. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 29(1), 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodsi, M. (2023). Exploring the ‘non-tariff measures black box’: Whose regulatory NTMs on which products improve the imported quality? International Economics, 173, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodsi, M., & Stehrer, R. (2022). Trade policy and global value chains: Tariffs versus non-tariff measures. Review of World Economics, 158(3), 887–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Pareja, S., Llorca-Vivero, R., & Martínez-Serrano, J. A. (2019). Reciprocal vs nonreciprocal trade agreements: Which have been best to promote exports? PLoS ONE, 14(2), e0210446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J. H., Peterson, E., & Ramniceanu, R. (2015). Assessing the impact of SPS regulations on US fresh fruit and vegetable exports. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 40(1), 144–163. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J., Xie, C., & Boys, K. (2022). Firms, Agricultural Imports, and Tariff-Rate Quotas: An Assessment of China’s Wheat, Corn, and Rice Imports Using Firm-Level Data (No. 938-2022-1211). Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/321889/files/IATRC%20CP28%20-%20GrantXieBoys.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Grubler, J., & Reiter, O. (2021). Characterising non-tariff trade policy. Economic Analysis and Policy, 71, 138–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L. A., Maggi, F., Piermartini, R., & Rubínová, S. (2020). The value of the Committee on Agriculture: Mapping Q&AS to trade flows. WTO Staff Working Paper, No. ERSD-2020-15. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/228654 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Jafari, Y., & Britz, W. (2018). Modelling heterogeneous firms and non-tariff measures in free trade agreements using Computable General Equilibrium. Economic Modelling, 73, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, Y., Britz, W., Guimbard, H., & Beckman, J. (2021). Properly capturing tariff rate quotas for trade policy analysis in computable general equilibrium models. Economic Modelling, 104, 105620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordaan, A., & Kanda, P. (2011). Analysing the trade effects of the EU-SA & SADC trading agreements: A panel data approach. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 14(2), 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, V. (2013). Preferential tariff formation–the case of the United States. Journal of World Trade, 47(4), 835–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaziboni, L. (2020). The usage of EPA Tariff-Rate Quotas (TRQ) by South Africa and the EU. Report for the EU-SA Partners for Growth Programme. Available online: https://sadc-epa-outreach.com/images/files/TRQ_Value_chain_report_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Keck, A., & Lendle, A. (2012). New evidence on preference utilization. In World Trade Organization Staff Working Paper No. ERSD-2012-12. World Trade Organization (WTO). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzius, L., Sandkamp, A., & Yalcin, E. (2019). Trade protection and the role of non-tariff barriers. Review of World Economics, 155(4), 603–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirpichev, D., & Moral-Benito, E. (2018). The costs of trade protectionism: Evidence from Spanish firms and non-tariff measures. Documentos de Trabajo del Banco de España, 1848(14), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, P. R., & Obstfeld, M. (2018). International economics: Theory and policy. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, C., & Bharti, N. (2020). Why NTM is a Challenge in Trade Relations? Evidence from India–Africa Agricultural Trade. Insight on Africa, 12(2), 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A., Lin, C. F., & Chu, C. S. J. (2002). Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. Journal of econometrics, 108(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmar, B., & Skully, D. (2003, June 23–26). China’s TRQ administration after one year: Crossing the river by feeling for stones. Contributed paper presented at the international conference agricultural policy reform and the WTO: Where are we heading? Capri, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchopa, C. L. (2021). Economic impact of tariff rate quotas and underfilling: The case of canned fruit exports from South Africa to the EU. Economies, 9(4), 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchopa, C. L., Bahta, Y. T., & Ogundeji, A. A. (2019). Tariff rate quota impacts on export market access of South African fruit products into the EU market. Agrekon, 58(4), 426–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchopa, C. L., Bahta, Y. T., & Ogundeji, A. A. (2020). Trade and welfare impacts of the frozen orange juice tariff rate quota of South Africa. The International Trade Journal, 34(2), 222–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchopa, C. L., Bahta, Y. T., & Ogundeji, A. A. (2021). Quantifying the missed EU market access opportunity for South African frozen strawberries. African Journal of Business and Economic Research, 16(3), 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, L. (2018). Reflections on the economic modelling of free trade agreements. Journal of Global Economic Analysis, 3(1), 156–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2019). Agricultural policy monitoring and evaluation 2019. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2024). Non-tariff measures. Tariffs are the tip of the iceberg: How behind the border issues impact trade. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/trade/topics/non-tariff-measures/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Ofori-Amoah, B. (2024). Regional trade agreements: Theory, aspirations, and realities. In The african continental free trade area: Prospects, problems and challenges (pp. 55–76). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Orden, D., Xie, C., Bowen Chen, L. B., & Zulauf, C. (2019). WTO dispute panel report on China’s administration of Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs) for certain agricultural products. Farmdoc Daily, 9(84). Available online: https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2019/05/wto-dispute-panel-report-on-chinas-administration-of-tariff-rate-quotas-trqs-for-certain-agricultural-products.html (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Orefice, G. (2017). Non-tariff measures, specific trade concerns and tariff reduction. The World Economy, 40(9), 1807–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rena, R. (2008). WTO and agricultural trade-some issues and perspectives. KASBIT Journal of Business, 1(1), 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Revell, B. J. (2017). Brexit and tariff rate quotas on EU imports: A complex problem. EuroChoices, 16(2), 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rial, D. P. (2014, July 16–20). Study of average effects of non-tariff measures on trade imports. Policy issues in international trade and commodities research study Series No. 66. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/itcdtab68_en.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Sachs, J. D., Lafortune, G., Fuller, G., & Drumm, E. (2023). Implementing the SDG stimulus. In Sustainable development report 2023. SDSN; Dublin University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, G. K. (2011). Implications of non-tariff measures on international business operations: A case of India’s textiles and clothing firms. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 5(2), 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, B., & Wilson, N. L. (2013). Product standards and developing country agricultural exports: The case of the European Union. Food Policy, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepotylo, O. (2016). Effect of non-tariff measures on extensive and intensive margins of exports in seafood trade. Marine Policy, 68, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, M. B., & Bhatta, G. R. (2018). Selecting appropriate methodological framework for time series data analysis. The Journal of Finance and Data Science, 4(2), 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skully, D. (1999a). US Tariff-Rate Quotas for Peanuts. ERS/USDA. Available online: https://corpora.tika.apache.org/base/docs/govdocs1/704/704873.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Skully, D. (2000). US TRQs for peanuts, sugar, and tobacco: Historical allocation and nondiscrimination. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 29(1), 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skully, D. W. (1999b). The economics of TRQ administration (No. 943-2016-74604). Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/14584/files/wp9906.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Skully, D. W. (2001). Liberalizing tariff-rate quotas. Agricultural Policy Reform in the WTO—The Road Ahead. Market and Trade (pp. 59–67). Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/41330/31770_aer802g_002.pdf?v=0 (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Suanin, W. (2023). Processed food exports from developing countries: The effect of food safety compliance. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 50(2), 743–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchakounte, A. D., & Fiankor, D. D. D. (2021). Trade costs and demand-enhancing effects of agrifood standards: Consequences for Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of African Trade, 8(1), 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thow, A. M. (2009). Trade liberalisation and the nutrition transition: Mapping the pathways for public health nutritionists. Public Health Nutrition, 12(11), 2150–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TRALAC. (2018). Economic partnership agreement between the European and Southern African development community group. Available online: https://www.tralac.org/documents/newsletters/2049-sadc-eu-epa-faqs-july-2018.html (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- UNCTAD. (2012). Volume 1: A Practical Guide to Trade Policy Analysis—UNCTAD. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/gds2012d2_en.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Vickers, B. (2018). Global Britain, Trade and Development: Issues and Priorities Post-Brexit. Navigating Uncertainty: Towards a Post-Brexit Trade and Development Agenda, 97, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, X., Yang, Z., Dong, H., Fan, X., & Wang, Y. (2018). Barriers to sustainable food trade: China’s exports food rejected by the US Food and Drug Administration 2011–2017. Sustainability, 10(6), 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolfrey, S., & Bilal, S. (2017). The impact of economic partnership agreements on the development of African value chains. ECDPM. Discussion Paper, 213. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/78247591/DP213-Impact-EPAs-African-Value-Chains.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Yuan, Y., & Awokuse, T. O. (2003, July 27–30). Exchange rate volatility and US poultry exports: Evidence from panel data. 2003 Annual meeting (No. 22083). American Agricultural Economics Association (New Name 2008: Agricultural and Applied Economics Association), Montreal, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Zainuddin, M. R. K., Sarmidi, T., & Khalid, N. (2020). Sustainable production, non-tariff measures, and trade performance in RCEP countries. Sustainability, 12(23), 9969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time Period | Policy Event |

|---|---|

| 2004 | TDCA came into full effect * |

| 2004 | Review of the TDCA occurred and appropriate amendments made |

| 2007 | Start of the process to work towards EPA involving EU, South Africa, and SADC ** |

| 2008 | Exporter administered permits became subject to the Agricultural Black Economic Empowerment (AgriBEE) sector charter in South Africa *** |

| 2012 | Full implementation of the TDCA—final phase of tariff preferences |

| 2013 | Accession of Croatia to the EU |

| 2014 | EPA negotiations concluded |

| 2016 | SADC–EU–EPA signature and implementation (EPA replaced the trade Chapter of the TDCA). SADC–EU–EPA capped some TRQs and further tariff liberalisation occurred for some tariff lines. |

| 2020 | Launch of major review of EU trade policy |

| 2021 | Start of SADC–EPA review after 5 years of implementation |

| Variable | Description | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Export Quantity (EXP) | Level of exports (in tonnes) from South Africa to the EU | TARIC database of the EU |

| Quota Level (QTL) | The available predetermined quantity (in tonnes) of product at which the EU applies a preferential tariff for imports from South Africa. | South African Annual Government Gazette (Various issues). |

| NTMs (NTM) | Total count of the number of NTMs affecting a particular TRQ. | Author compilation based on WTO Integrated Trade Intelligence Portal (ITIP) |

| MFN tariff (MFN) MFNsit MFNℎit | Most Favoured Nation Tariff (% ad valorem) charged for out-of-quota export quantities. Indicator equal to 1 if the MFN tariff charged is lower than the cut-off level of 17.89%; otherwise, the indicator is equal to zero. Indicator equal to 1 if the MFN tariff charged is higher than the cut-off level of 17.89%. | WTO Tariff Analysis Online (TAO) Author calculation Author calculation |

| In-quota tariff (IQT) | Preferential tariff rate (% ad valorem) charged for within quota export quantities. | WTO Tariff Analysis Online (TAO) |

| IQTsit | Indicator equal to 1 if the in-quota tariff charged is lower than the cut-off level of 8.96%; otherwise, the indicator is equal to zero. | Author calculation |

| IQTℎit | Indicator equal to 1 if the in-quota tariff charged is higher than the cut-off level of 8.96%; otherwise, the indicator is equal to zero. | Author calculation |

| Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) | Dummy variable equal to 1 if trade was occurring under the SADC–EU–EPA; otherwise, the dummy is equal to zero. | Author calculation |

| TRQ Description | HS 6-Digit Codes of Tariff Lines Included | Quota in 2004 (t) | Quota in 2021 (t) | Types of Measures (NTMs) Present |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strawberries | 081110 | 280 | 415 | SPS, TBT |

| Canned mixed fruit * | 200840/50/70 | 44,800 | 57,156 | SPS, TBT, QR |

| Tropical canned fruit | 200892/97 | 2240 | 3260 | SPS, TBT, QR |

| Frozen orange juice | 200911 | 784 | 1141 | SPS, TBT, QR |

| Apple/Pineapple juice ** | 200941/71/79 | 5600 | 4063 | SPS, TBT, QR |

| Variable | Level (0) 1st Difference (1) | Intercept | Intercept and Trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-Stat | p-Value | Conclusion | t-Stat | p-Value | Conclusion | ||

| EXP | 0 | −107.940 | 0.0000 | Stationary | −152.469 | 0.0000 | Stationary |

| 1 | −110.052 | 0.0000 | Stationary | −85.8580 | 0.0000 | Stationary | |

| LogEXP | 0 | 3.27303 | 0.9995 | Non-stationary | 1.29425 | 0.9022 | Non-stationary |

| 1 | −1.08534 | 0.1389 | Non-stationary | −6.31067 | 0.0000 | Stationary | |

| QTL | 0 | 0.35256 | 0.6378 | Non-stationary | −0.39853 | 0.3451 | Non-stationary |

| 1 | −6.49177 | 0.0000 | Stationary | −7.32946 | 0.0000 | Stationary | |

| LogQTL | 0 | −1.88083 | 0.0300 | Stationary | −0.27634 | 0.3911 | Non-stationary |

| 1 | −7.11032 | 0.0000 | Stationary | −7.20589 | 0.0000 | Stationary | |

| NTM | 0 | 19.1505 | 1.0000 | Non-stationary | 17.4146 | 1.0000 | Non-stationary |

| 1 | 1.52355 | 0.9362 | Non-stationary | −1.99290 | 0.0231 | Stationary | |

| LogNTM | 0 | 1.27837 | 0.8994 | Non-stationary | −1.00341 | 0.1578 | Non-stationary |

| 1 | −11.1010 | 0.0000 | Stationary | −11.5674 | 0.0000 | Stationary | |

| Correlated Random Effects—Hausman Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Test Cross-Section Random Effects | |||

| Test Summary | Chi-Sq. Statistic | Chi-Sq. d.f. | Prob. |

| Cross-section random | 32.378803 | 4 | 0.0000 |

| Variable | Mean | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Std. Dev. | C.V. | Skewness | Ex. kurtosis | Missing obs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | 9861 | 3680 | 0 | 51,609 | 14,415 | 1.4617 | 1.7199 | 1.7395 | 0 |

| Quota | 16,711 | 5675 | 280 | 62,103 | 21,176 | 1.2672 | 1.0292 | −0.5281 | 0 |

| NTMs | 3 | 1 | 0 | 24 | 5.5580 | 1.6786 | 2.7093 | 6.8982 | 0 |

| Variable Dep. Variable—Export Quantity | Model 1: Common Effects | Model 2: Random Effects | Model 3: | Model 4: Fixed Effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (Prob.) | t-Statistic | Coefficient (Prob.) | t-Statistic | Coefficient (Prob.) | t-Statistic | Coefficient (Prob.) | t-Statistic | |

| Constant | −0.176266 (0.7518) | −0.317875 | −0.656740 (0.0000) | −0.788388 | 1.825550 (0.0290) | 2.263611 | −8.680788 (0.1330) | −1.53056 |

| Quota Level (QTL) | 0.976633 (0.0000) | 16.26097 | 1.015345 (0.0000) | 11.34599 | 0.936339 (0.0000) | 14.54079 | 2.294642 (0.0042) | 3.019369 |

| Number of NTMs (NTM) | −0.032811 (0.8242) | −0.223154 | −0.122755 (0.4658) | −0.734382 | −2.636021 (0.0005) | −3.812462 | 0.135514 (0.6708) | 0.427883 |

| [Number of NTMs] × [Above mean in-quota tariff] (HIGHIQT) | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.243652 (0.0011) | −3.48854 |

| [Number of NTMs] × [Below mean in-quota tariff] (LOWIQT) | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.017846 (0.7944) | −0.26219 |

| Economic Partnership Agreement Dummy (EPA) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.888201 (0.7549) | 0.314194 |

| [Economic Partnership Agreement Dummy] × [ Quota Level] (EPAQTL) | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.000187 (0.6850) | −0.40828 |

| [Above mean out-of-quota tariff] × [ Quota Level] (HIGHMFN) | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.000584 (0.1134) | −1.61531 |

| [Below mean out- of-quota tariff] × [ Quota Level] (LOWMFN) | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.000132 (0.0387) | −2.13078 |

| [Number of NTMs] × [ Quota Level] (NTMQTL) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3.35 × 10−6 (0.0189) | 2.436716 |

| R-squared Prob(F-statistic) | 0.828002 0.000000 | 0.669019 0.000000 | 0.867703 0.000000 | 0.856927 0.000000 | ||||

| Durbin–Watson Stat | 0.848520 | 0.881291 | 0.958774 | 1.479978 | ||||

| Redundant Fixed Effects Tests Test Cross-Section Fixed Effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Effects Test | Statistic | d.f. | Prob. |

| Cross-section F | 9.754498 | (4,44) | 0.0000 |

| Cross-section Chi-square | 36.822326 | 4 | 0.0000 |

| TRQ ID | Effect |

|---|---|

| Frozen Strawberries | −1.750448 |

| Canned Pears, Apricots, and Peaches | 1.346671 |

| Fruit Mixtures | −2.537186 |

| Frozen Orange Juice | −0.358754 |

| Apple Juice | 1.743138 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muchopa, C.L. The Tariff Liberalisation Policy Nexus with Non-Tariff Measures: Panel Model Evidence in the SA–EU Fruit Products Trade. Economies 2025, 13, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13010001

Muchopa CL. The Tariff Liberalisation Policy Nexus with Non-Tariff Measures: Panel Model Evidence in the SA–EU Fruit Products Trade. Economies. 2025; 13(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuchopa, Chiedza L. 2025. "The Tariff Liberalisation Policy Nexus with Non-Tariff Measures: Panel Model Evidence in the SA–EU Fruit Products Trade" Economies 13, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13010001

APA StyleMuchopa, C. L. (2025). The Tariff Liberalisation Policy Nexus with Non-Tariff Measures: Panel Model Evidence in the SA–EU Fruit Products Trade. Economies, 13(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13010001