Abstract

The objective of the paper is to analyse and compare the consequences of the coronacrisis on the entrepreneurship of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Slovakia and the Czech Republic with the aim of identifying the determinants of changes in entrepreneurship. The secondary empirical research was carried out based on the analysis of secondary and primary data. The analysis used economic indicators of SMEs, governmental measures and surveys of the views of entrepreneurs. The analysis used data from statistical databases and official reports from government institutions and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), as well as data from primary surveys conducted by NGOs. Descriptive statistics, financial analysis and cross-comparison methods were used to process the data. The results revealed changes in the business of SMEs in the Czech Republic and Slovakia during the crisis, such as the adaptation of business strategies, improvement of flexibility and acceleration of digitalisation processes. These changes highlighted the importance of building business agility. The summary of the main changes in SME business based on both secondary data and primary surveys and the perception of state anti-pandemic aid by managers as feedback to governments represent the main contributions of the paper.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the most important factors that will affect the business environment in the years 2020 and 2021. The rapid onset and spread of the epidemic have made it a pandemic affecting a geographically large area of the world, requiring coordinated international cooperation. The rapid spread of the COVID-19 epidemic had a significant impact on the global financial market, posing unprecedented risks to the global economy and causing large losses to investors in a short period of time (Mou 2020). The decline in economic activity affected both developed and developing countries. The main economic impact of the H1N1 pandemic was due to fear and discrimination, which are the main factors affecting the economy (Gong et al. 2020). In the European Union (EU) as a whole, economic performance has declined, mainly due to the downturn of the major EU economies (Fuentes and Moder 2021).

The noncyclical crisis caused by the uncontrollable spread of COVID-19 demonstrated its unpredictable nature (Iacob et al. 2021). The pandemic limited the ability of large masses of people to continue their professional activities due to the measures of physical distancing. This affected the production capacity and ultimately the aggregate supply of the economy (Oncioiu et al. 2021). Compared to the 2008 crisis, the economic recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic had a greater impact on businesses. As a result of the various measures taken to prevent the spread of the disease, many companies had to reduce or cease operations. This caused significant problems for the economies of the affected countries.

The direct effects of the coronacrisis were observed in most countries (Balasoiu 2021; Abd Aziz et al. 2022; Turnea et al. 2020) in terms of reduced income, job losses, customer preferences, low demand, cash flow problems, obstacles to the free flow of capital, labour and trade. Companies in some sectors have lost up to 60% of their intrinsic value in one year (Rizvi et al. 2022). The tourism, transport and culture sectors have experienced the most significant declines in economic activity. The recovery of the global economy after the COVID-19 pandemic will depend on the human response to the crisis (Lenzen et al. 2020). Governments around the world have taken a number of measures to mitigate the negative impact of the pandemic on aspects of personal and professional life, the economy and public health. The measures taken have led to (temporary) disruptions in global supply chains. This has had an impact on foreign trade and consumer price trends, which have been characterised by increasing momentum in 2021.

Due to their limited resources, SMEs are among the most vulnerable categories of enterprises in times of crisis, and COVID-19 has a particularly negative impact on them. Publications by authors such as Birbirenko et al. (2020), Langworthy and Warnecke (2021), Gashi et al. (2021), Clampit et al. (2022) and Abuhussein et al. (2021) have studied and analysed the impact of the crisis on the SME economy in countries around the world. The majority of the publications make use of data and methods from secondary and quantitative research. Only a few studies, such as Al-Fadly (2020) or Du et al. (2023), explore the impact of the coronacrisis on SME entrepreneurship through primary qualitative research. This paper aims to fill this gap and provide results summarising the changes in SME business based on combining secondary data analysis and primary questionnaire surveys in two countries and comparing the results.

The position of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the national economy is particularly important given their contribution to total employment, value added and economic development. The importance of SMEs can also be seen in the structure of economically active units. According to the UNCTAD (2022)’s report, micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) account for more than 90% of all enterprises. On average, they provide 70% of total employment and 50% of gross domestic product (GDP). The impact of the pandemic on the SME economy will therefore have the greatest impact on national economic performance. Proper support for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises is key to a sustainable and inclusive recovery from the pandemic. This has led to this paper focusing on SMEs.

The aim of the paper is to analyse the impact of the crisis on SME entrepreneurship in Slovakia and the Czech Republic in order to identify the determinants of changes in entrepreneurship not only through the analysis of changes in economic indicators, but also through information obtained directly from firm managers in a primary survey. This complex view distinguishes the paper from other published studies. The paper contributed to the theoretical knowledge by summarising the changes in the business of SMEs due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The empirical contribution can be found in the results from Slovakia and the Czech Republic regarding the impact of the pandemic on the business of SMEs. The assessment of entrepreneurs’ views on government support measures to mitigate the effects of the pandemic and the extent of their use by SMEs can serve as feedback and inspiration for policy makers in proposing appropriate government interventions.

2. Literature Review

Given the economic implications of COVID-19, some researchers have examined the economics in specific areas. Li and Xu (2022) conducted a comprehensive review and analysis of publications in the field of financial innovation. Most financial activities were restricted during the coronacrisis due to public isolation, travel restrictions, movement restrictions and other similar measures, which was a significant blow to many small and medium-sized enterprises (Saputra and Herlina 2021). Some studies have shown that COVID-19 caused supply chain disruptions and thus a decline in the economic performance of SMEs (Al-Hakimi et al. 2021; Zainal et al. 2022). Although national governments have taken a number of measures to improve supply chain performance, they appear to have failed to ensure sufficient supplies of essential goods at a time when consumers were panic buying, particularly of food and healthcare products. (Nicola et al. 2020; Goel et al. 2021). Mody et al. (2021) have begun to review research on the sharing economy. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on economic, environmental and social change has been analysed by Bashir et al. (2020). There is still a need to adopt strategies that ensure long-term survival, with environmental sustainability becoming one of the most important factors in the pandemic crisis (Lu et al. 2021).

According to Iancu et al. (2022), limited access to liquidity, lack of strong government support, poorly prepared and motivated human resources, and low digitalisation were the weaknesses of SMEs and the main obstacles to resilience in this crisis. Research by Du et al. (2023) showed that COVID-19 had a significant negative impact on profitability, operations, economics and access to finance. According to the findings of the study, external financial support plays an important role in the ability of SMEs to persevere and succeed through technological innovation rather than their actual output. As a result, SMEs are under increasing pressure to modernise their operations through a variety of technologies (Zaverzhenets and Łobacz 2021). Xia et al. (2021) developed a technology-organisation-environment model that is useful for adapting to changing circumstances, as it allows the study of interactions between processes, inputs and outputs. The COVID-19 pandemic has led SMEs to abandon their traditional methods in favour of more environmentally friendly ones in order to operate in a sustainable manner. To achieve this, SMEs need technologies that can be adapted (Du et al. 2023).

Other factors influencing the ability of SMEs to survive and cope with the coronacrisis include employee and customer satisfaction in the changing situations. (Khan et al. 2022; Fasth et al. 2022; Thekkoote 2023). A study by Dyduch et al. (2021) showed that the alignment of the organisation’s internal and external environments had a mitigating effect on the decline in business performance during the coronacrisis. According to Zhang et al. (2021), top management should evaluate both internal and external factors that affect the company’s performance, understand their results and seize the opportunities to protect the company. The importance of strategic flexibility, innovation-oriented strategies, implementing agile behaviour and dynamic capabilities and applying creativity to adapt to new conditions has been highlighted as a matter of survival in emerging economies (Chomicki and Mierzejewska 2020; Thukral 2021; Zutshi et al. 2021; Yaya et al. 2022; Chen et al. 2023). According to Zahoor et al. (2022), agile adaptation and exploitation of new opportunities were the main means of coping with the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in Finnish SMEs.

SMEs are the main source of new product and technology development (Le and Nguyen 2022). The addition of new products, processes and management activities related to the delivery of a product or service can also be considered innovation (Miocevic 2022). Some SMEs have responded to the crisis by applying creativity in problem solving to seize opportunities (Thukral 2021). For these opportunities to be realised, some government intervention is needed to remove the negative effects of blocking constraints (Adam and Alarifi 2021). SMEs continue to pose a significant challenge to economic policy makers and investors in the current dynamic business environment (Rahman et al. 2022). A study by Al-Fadly (2020) highlights the need for more government action to support surviving firms and revive lost businesses.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, most countries introduced measures to support SMEs and the self-employed, with a particular focus on maintaining short-term liquidity and employment. These measures take different forms in the following areas: financial instruments, payment deferrals, employment and structural policies (OECD 2021). Some countries have introduced measures on short-time working, temporary lay-offs and sick leave. In these cases, governments provide wage support and income to temporarily laid-off workers and firms to maintain employment. Many countries have also introduced measures specifically targeted at the self-employed. To ease liquidity constraints, governments have introduced measures to defer taxes, social security payments, debts, rent and utility bills. In some cases, tax breaks, debt repayment moratoria or loan guarantees have also been introduced to encourage commercial banks to lend more to SMEs. Several countries have increased direct lending to SMEs or the provision of grants and subsidies by public institutions to bridge the income gap. Some countries are increasingly focusing on structural policies to help SMEs adopt new working methods and technologies or find new markets and sales channels so that they can continue to operate while the measures are being implemented. These policies focus not only on pressing short-term challenges, but also on supporting their continued growth. (SBA 2020a; OECD 2020).

The publications provide information on the main impacts of the pandemic crisis on the business sector, factors affecting the survival of SMEs during the pandemic period, options for overcoming the pandemic crisis and the need for state aid. A comprehensive assessment of the changes in the economy and business of SMEs due to the impact of the coronacrisis, or an assessment of the adequacy and sufficiency of state support to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by business managers, is only marginally found in existing studies. This paper aims to fill this gap in the literature. It also adds to the existing knowledge by comparing the impact of the coronacrisis on SME entrepreneurship in two EU countries, Slovakia and the Czech Republic.

3. Methodology

A review of many scientific papers focused on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on SMEs in countries around the world showed the importance of addressing this issue and was the inspiration for the objectives and methodology of the paper. The authors deal with the contemporary research focused on the reactive agility of enterprises in the context of the coronacrisis and follow up their previous works focused on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy of the selected countries and on the determinants of the external and internal business environment that cause the need for building enterprise agility in the context of the coronacrisis impact.

3.1. Initial Data

The sources of secondary data were the databases of the Czech Statistical Office (CSO 2023a, 2023b) and official reports of government institutions (MPO CR 2021) and NGOs in 2020–2022 (SBA, IPSOS, OECD, UNCTAD). The subjects of the analysis were government measures to support SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic (SBA 2020a; MPO CR 2021; OECD 2020, 2021) and SME data on the number of business units, number of employees, production, amount of sales, added value and profit in 2019–2021 (SBA 2021a, 2022; CSO 2023b).

The results of quantitative primary surveys conducted by NGOs in the Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic were analysed from the official reports of the Slovak Business Agency and IPSOS in the Czech Republic. The survey results and questionnaires from Slovakia can be found at:

https://www.sbagency.sk/sites/default/files/sprava_kvalita_pp_fin_0.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2023) (SBA 2020c) and https://www.sbagency.sk/sites/default/files/sprava_z_prieskumu_postojemsp_k_pp.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2023) (SBA 2021b). The primary survey, its results and the questionnaire conducted by IPSOS in the Czech Republic can be found at: https://amsp.cz/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Ipsos-pro-AMSP_Covid-a-Zm%C4%9Bny-v-podnik%C3%A1n%C3%AD_FINAL-_TZ-1.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2023) (IPSOS 2021).

3.2. Methods and Variables

The method used was secondary empirical research based on the analysis of both secondary and primary data. Secondary research is an empirical method based on the use of data collected by someone else. It can be qualitative or quantitative (Tegan 2023). Our secondary research is quantitative and uses data from meta-analyses and public sector databases.

In processing the economic data, methods of descriptive statistics and economic analysis were used, especially indices of change. The development trend of the economic indicators was assessed using time series analysis and the calculation of development indices (Ix). The development index is calculated as follows:

where X is the value of the economic indicator, t is the period. The result is expressed as a percentage. A positive result indicates growth, a negative result indicates decline.

Time series analysis is used to identify trends, seasonal variations and random fluctuations in data. There are a number of theoretical models for this analysis. A moving average model (see Gershenfeld 1999), which was used in this study, is used to identify trends and seasonal variations.

The primary data analysed in the paper come from quantitative questionnaire surveys conducted by the Slovak Business Agency in Slovakia and IPSOS in the Czech Republic. A questionnaire survey is a data collection method used to obtain information from respondents about their opinions, attitudes or behaviours. The theoretical basis of questionnaire research is that the researcher uses existing theories and models to create the questions necessary to obtain the desired information (Rea and Parker 2014). The minimum research sample (n), which serves as the main assumption allowing the generalisation of the research results to the entire population (all SMEs), is determined by the following relationship (Pacáková et al. 2009):

where ‘z’ is the reliability coefficient of the data, ‘p’ is the confidence level and ‘c’ is the margin of error. By applying the formula and then performing the calculation, it was found that with a base set of over 20,000 units, with a confidence interval of 95% and a margin of error of 5%, 384 respondents are required in the survey.

3.3. The Characteristics of the Quantitative Primary Surveys

Quantitative surveys in the Slovak Republic were carried out by the Slovak Business Agency in cooperation with the Association of Slovak Entrepreneurs and the Slovak Trade Union. The data collection was based on a questionnaire prepared by the Slovak Business Agency. The first survey was conducted in October 2020 (SBA 2020c). The aim of the survey was to find out the opinions of sole proprietors, small and medium-sized entrepreneurs on the impact of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, the measures implemented in the companies, the anti-pandemic measures taken in connection with the second wave of the coronacrisis and to obtain information on the preferred support measures. A total of 1109 respondents participated in the survey. The second survey was conducted in December 2021 and focused on the monitoring SME financing (SBA 2021b). As part of the questionnaire questions, entrepreneurs assessed the government’s measures to mitigate the effects of the coronacrisis, as well as the impact of the coronacrisis on the level of digitalization in their enterprises. A total of 1000 respondents participated in the survey. The answers of the entrepreneurs were evaluated according to a second-level classification based on four observed characteristics of the respondents: type of economic activity SK NACE, legal form, registered office and length of business activity. The statistical analysis programme IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26.0, was used to process and evaluate the individual responses.

The quantitative survey in the Czech Republic was conducted by IPSOS for the Association of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and Tradesmen of the Czech Republic in February 2021 using a structured online questionnaire (IPSOS 2021). The aim of the survey was to map the impacts of the coronacrisis and their management from the perspective of SME entrepreneurs. The target group consisted of sole proprietors and owners, managers and directors of SMEs with 4–250 employees. The responses of the entrepreneurs were analysed by classification into sole proprietorships and other SMEs and by sector of activity (manufacturing, trade, services).

In both countries, the survey method used was by means of a questionnaire. The representative samples in the surveys were drawn by stratified random sampling from a core set of small and medium-sized enterprises operating in the Slovak and Czech Republics in 2020 and 2021. The respondents to the surveys were representatives of business decision-makers, i.e., business owners, CEOs, managing directors or competent personnel authorized to answer the questions. The focus and goal of the surveys were the same, but the content of the questionnaires differed in some questions. Therefore, the same questions were selected from the surveys to ensure comparability. The first part of the questionnaires concerned the identification of the respondent: number of employees, type of activity, region of operation and age of the enterprise. The second part of the questionnaires contained questions aimed at assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and its intensity, areas, or indicators of the company most affected by the pandemic and measures taken in the companies to overcome the pandemic crisis. The third part of the questionnaires was focused on managers’ attitudes towards the state support provided during the pandemic and the extent to which it was used. The last selected question concerned the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on digitization processes in the company.

4. Results

This section presents the results of the secondary research in the following order: the impact of the pandemic on the SME economy, an overview of the measures taken by the Slovak and Czech governments to support SMEs, and the results of the primary quantitative surveys in the Slovak and Czech Republics. Small and medium-sized enterprises represent 99.8% of the total number of business entities in both the Slovak and the Czech economies. They account for almost two thirds of employment in the business economy and contribute more than half of the total value added (56% in the Czech Republic and 54% in Slovakia), which is comparable to the EU average.

4.1. The Impact of the Pandemic on the Economy of SMEs

One of the hardest hit and most vulnerable sectors in the first wave of the pandemic was the accommodation and food services sector, which was already experiencing restrictions or outright closures. Another sector severely affected by the pandemic was the other services sector, which includes education, health and social work and covers a wide range of activities—from health care provided by trained health professionals in hospitals and other facilities, to home care and social work activities without the involvement of health professionals. Within the other services sector, culture, entertainment and recreation (live performances, museum activities, gambling activities, sports and leisure activities) and personal services such as hairdressing, beauty and other personal care activities also form an important group. In addition to the sectors mentioned above, commerce—and in particular retail outlets—was also affected by major restrictions and closures. During the first wave of the pandemic, almost all retail outlets were closed. Those that were allowed to remain open had to comply with strict hygiene requirements to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. The restriction on the number of people in the premises, together with the rising costs of improving hygiene levels, reduced the bottom line for businesses, which saw their operating costs rise and their revenues fall. The final sector directly affected by the ban and restrictions was transport. The border regime is linked to this and other sectors. Travel restrictions and border closures during the first wave of the pandemic almost completely halted international passenger traffic and severely restricted international freight traffic, which in turn affected all sectors that rely on the import and export of goods. (SBA 2020b; MPO CR 2021).

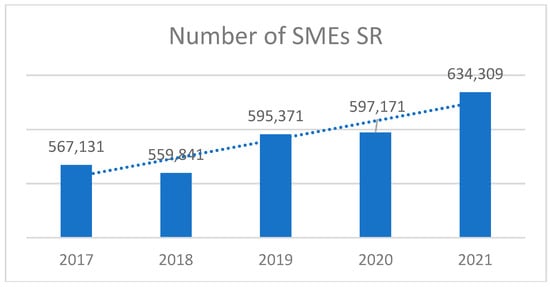

The number of small and medium-sized enterprises is one of the most important quantitative indicators characterising the state of the SME sector. The development of the number of newly created SMEs was very dynamic during the period analysed. The number of business start-ups in the Slovak Republic that fall into the SME size category during and after the two waves of the pandemic (as opposed to micro-enterprises) did not reach the pre-pandemic level. Most newly born enterprises in the Slovak Republic are micro or small enterprises. In 2020, 83,173 business units (all SMEs) were created. Compared to 2019, the number of business entities created decreased by 2%. The development of the number of liquidated business entities in the SR in 2020 indicates that entrepreneurs did not stop their business activities immediately after the outbreak of the pandemic. The unclear epidemiological situation and the deteriorating performance of enterprises caused the closure of the most affected enterprises only in the 3rd and 4th quarter of 2020. In 2020, 47,648 business entities closed—8449 (or 15.06%) fewer than in 2019. In 2021, the number of business entities closing increased to 51,724. The lower number of business entities closing is also due to the adoption of the COVID-19 support measures. The most significant decrease in the number of enterprise deaths was in the liberal professions (−32.1%). More than four fifths of the total number of enterprises that disappeared were sole proprietorships (82.1%) (SBA 2021a). Given that the number of newly born units was higher than the number of units that disappeared, there was a net gain of 14.9% in 2021. This is the highest level of net growth in the last 10 years. Compared with the previous year, the number of SMEs increased by 37,138 units (SBA 2022). The development of the number of SMEs in the Slovak Republic in the period 2017–2021 is shown in the graph in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Development of the number of SMEs in the Slovak Republic in the period 2017–2021. Source: own processing according to data of SBA (2022).

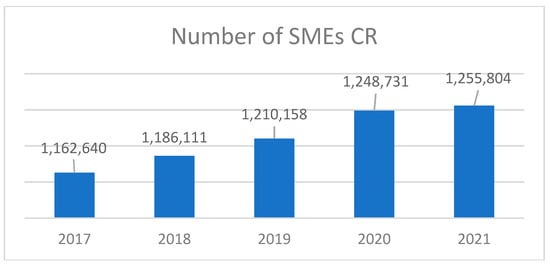

According to the Czech Statistical Office, 94,490 business entities were established in the Czech Republic in 2020, of which 62,188 were sole proprietors. Compared to 2019, the number of established business entities decreased by 6379, a decrease of 6.3%. In 2021, 102,709 business entities were established, an increase of 8219 new business entities compared to 2020. In 2020, 61,601 business entities disappeared, representing 42,923 fewer entities than in 2019. The number of disappeared business entities increased by 2920 to 64,521 in 2021. More than 70% of the total number of disappeared business entities in both pandemic years were sole proprietorships (CSO 2023a). As in the Slovak Republic, there was a net increase in the number of SMEs in the Czech Republic in 2020 and 2021, as more enterprises were created than disappeared. Compared with the previous year, the number of SMEs increased by 38,573 entities in 2020 and by 7073 entities in 2021 (CSO 2023b). The development of the number of SMEs in the Czech Republic in the period 2017–2021 is shown in the graph in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Development of the number of SMEs in the Czech Republic in the period 2017–2021. Source: own processing according to data of CSO (2023b).

- Employment

Micro-enterprises were the most important in terms of employment among SMEs in the Slovak Republic. In 2021, their share was 46.1%. Small and medium-sized enterprises have a significantly lower share (14.1% each) (SBA 2022). Table 1 gives an overview of the percentage change in employment between 2017 and 2021.

Table 1.

Changes in employment in SMEs in the Slovak Republic.

Employment in the business sector decreased by 1.0% (by 18.3 thousand persons) to 1870.6 thousand persons. The share of persons employed in the profit-oriented business sector in the total number of persons employed in the Slovak economy decreased to 79.4% in 2021. Entrepreneurs operating in the hotels and restaurants sector had problems retaining their employees. Employers in these sectors faced the problem of redundancies, with employment falling by 9.2% and 7.2%, respectively. Only two branches, information and communication activities and selected market services, recorded an increase in business employment in 2021 (SBA 2022).

- The Gross output of SMEs in the Slovak Republic

In 2020, non-financial SMEs produced products and services with a total value of EUR 62,889 million, which represents 45.31% of the total gross output of non-financial corporations in the Slovak Republic in that year. The volume of the gross output of SMEs thus decreased by 13.57% in 2020 compared to the previous year as a result of the pandemic. In the second half of 2020, the volume of gross output started to increase gradually and the increase in output compared to 2019 occurred only in the first quarter of 2021. The changes in the production of SMEs in the Slovak Republic are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Year-on-year comparison of the gross output of SMEs in Slovakia in the period 2020–2021.

- The Profit of SMEs in the SR

SMEs reported a total profit of EUR 4790 million in 2020, representing 53.09% of the profit generated by all non-financial companies in the Slovak Republic in 2020. Compared to 2019, which was not affected by the negative impact of the pandemic, SMEs thus reported a lower profit of EUR 640 million (or 32.92%). The impact of the second wave of the pandemic was more pronounced for micro and small enterprises, which is also related to their sectoral structure. The volume of profits made by micro and small enterprises in 2021 did not exceed the volume of profits before the pandemic and decreased compared to 2020, especially by 47% for small enterprises. Table 3 shows the changes in the profits of SMEs in the SR.

Table 3.

Year-on-year comparison of the profits of SMEs in Slovakia in the period 2020–2021.

The economic indicators for the group of SMEs in the Czech Republic and their development in 2020 and 2021 are not publicly published in any available information source. Therefore, they are not presented in the results.

4.2. Government Measures to Support SMEs

The governments of the Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic have introduced measures to support SMEs and the self-employed with the aim of maintaining short-term liquidity and employment in enterprises. An overview of the individual measures in the four areas is given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Overview of SME support measures in the Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic.

In the area of employment, the Slovak government provided wage subsidies to SME employers and compensation to individual entrepreneurs as a contribution to the loss of income from employment, determined according to a minimum 10% decrease in turnover. The Czech Government decided to grant only wage subsidies to those employed.

In the area of payment deferral, in both the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic SMEs and sole proprietors could apply for deferral of income tax payments and for deferral of loan or mortgage repayments without deterioration of the borrower’s creditworthiness for a maximum of 9 months. In the Slovak Republic, employers and self-employed persons who are compulsorily insured and who have experienced a decrease in turnover of 40% or more were able to apply for the deferral of social security contributions and the advance payment of health insurance contributions. The Slovak government also approved a waiver of the obligation to pay employer’s social insurance, pension saving and supplementary pension saving contributions if the employer or compulsorily insured self-employed person was closed for at least 15 days in April 2020, based on a decision of the Health Insurance Office.

In the area of financial instruments, the Czech government introduced all three instruments. In addition to loan guarantees and interest subsidies, it has created special loan funds to help SMEs raise working capital. The Government of the Czech Republic has guaranteed loans and/or paid interest on bank loans and provided subsidies in the form of an interest subsidy for loans to SMEs or a lump sum for self-employed persons without income.

Structural policy instruments have been used only in the Czech Republic, in the form of the Czech Rise Up Programme to support innovative enterprises, including start-ups, and the Technology Programme to support the acquisition of new technological equipment and facilities by SMEs, which is directly related to the fight against the spread of the virus (OECD 2021).

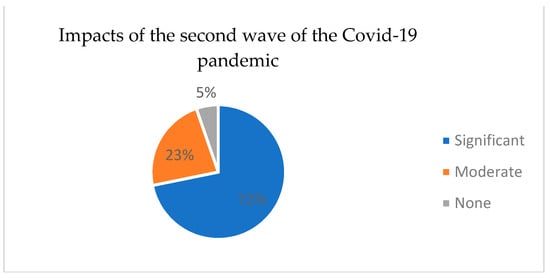

4.3. The Results of the Survey on the Views of Entrepreneurs in the Slovak Republic

The negative impact of the adoption of anti-pandemic measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Slovakia is felt by 94.7% of the surveyed companies (see Figure 3). Most of the enterprises experiencing a significant negative impact of the measures taken are in the food service sector, but were also found in the arts, entertainment, recreation and sport sectors.

Figure 3.

Assessment of the negative impact of anti-pandemic measures in the SME in the SR. Source: adjusted from data of SBA (2020c).

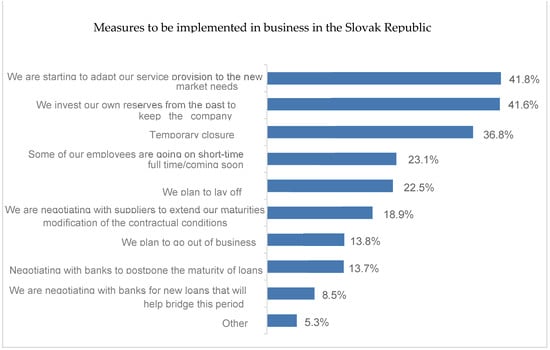

The results of responses to the question “What measures are you implementing in your business in response to the coronacrisis to reduce losses?” are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Measures implemented in Slovak enterprises during the COVID-19 pandemic. Source: adjusted from data of SBA (2020c).

In response to the second wave of the coronacrisis, companies are implementing a wide range of measures to reduce losses. The most common measure taken by the companies surveyed (42%) is to adapt the services they provide to the new needs of the market. At the same time, the same proportion of respondents (42%) are approaching the current crisis in their business by investing their own reserves from the past to keep the business running. More than a third (37%) of the interviewed entrepreneurs have temporarily closed their business, either because of an order from the Central Crisis Staff of the Slovak Republic or because of a significant drop in demand and sales. Almost a quarter (23%) of entrepreneurs have responded to the second wave of the coronacrisis by reducing the working hours of their employees or plan to do so soon. A more radical measure, in the form of redundancies, is also planned by almost a quarter (23%) of the companies surveyed. Plans to lay off staff are most common among food service entrepreneurs (44%). The worst-case scenario, i.e., closing down completely, is planned by a further 14% of SMEs in the near future.

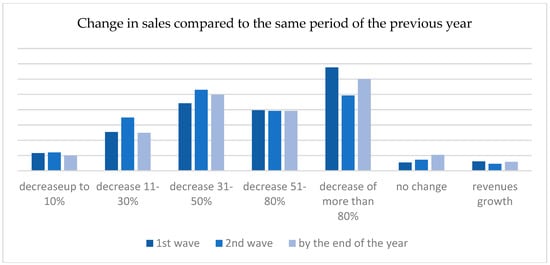

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on SMEs’ revenues, according to the responses of entrepreneurs, is shown in the graph in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Changes in the sales of SMEs in the Slovak Republic compared to the same period of the previous year. Source: adjusted from data of SBA (2020c).

The answers of the entrepreneurs show that during the first wave of the coronacrisis (April–May 2020) up to 94% recorded a drop in sales, while most of the enterprises recorded a significant drop in sales of more than 80%. The same proportion, 94% of SMEs, also recorded a fall in turnover in the second wave of the crisis. Compared with the first wave, however, the situation is slightly different, with a larger number of entrepreneurs experiencing smaller falls in turnover in the current situation. However, up to half of the SMEs experienced a fall in turnover of up to 50% compared with the same period a year earlier. Across all economic sectors, the decline in turnover in both waves of the crisis was most pronounced in those sectors most affected by anti-pandemic measures, such as food services, arts, entertainment and recreation.

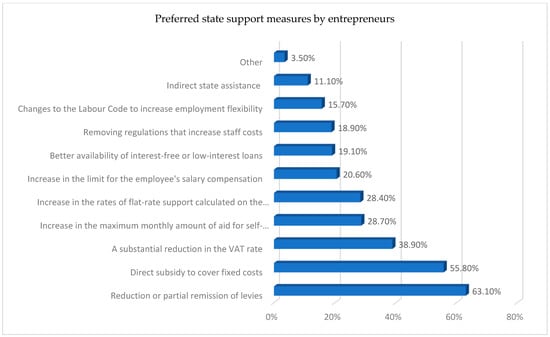

The preferred measures to support businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic are shown in Figure 6. Businesses would clearly like to see a reduction or partial waiver of taxes (63%). More than half (56%) of businesses prefer measures in the form of direct subsidies to cover their fixed costs. The third most desired measure to help businesses in the current difficult situation is a significant reduction in the VAT rate. This measure is favoured by 39% of entrepreneurs. This is followed by measures that have already been adopted by the Slovak government, such as an increase in the maximum monthly amount of subsidies for self-employed persons and one-person limited liability companies, and an increase in the rates of lump-sum subsidies calculated on the basis of the decrease in turnover. The companies participating in the survey were also interested in indirect government support in the form of changes to the Labour Code to increase employment flexibility (preferred by 16% of respondents) or the provision of advisory and other services to help overcome the second wave of the crisis (11% of entrepreneurs).

Figure 6.

Preferences of entrepreneurs in the Slovak Republic for state support measures. Source: adjusted from data of SBA (2020c).

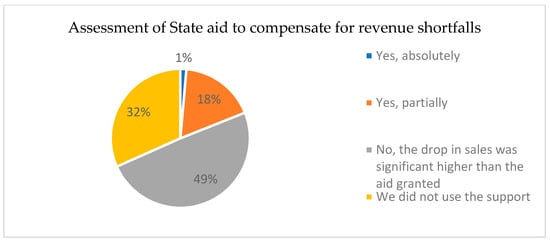

The evaluation of the government’s economic measures to support SMEs was carried out in two surveys, at the beginning of the second wave of the pandemic and at the end of the pandemic. At the beginning of the period, in the second wave of the pandemic, the results of the survey in Figure 7 indicate that the existing state aid did not compensate for the drop in sales of entrepreneurs in Slovakia. For almost half of the enterprises surveyed (49%), the fall in turnover was significantly higher than the state aid received. The situation was worst for entrepreneurs in the restaurant and catering sector, where more than half (65%) of the entrepreneurs experienced a fall in turnover significantly higher than the state aid. For various reasons, almost a third (32%) of the enterprises surveyed had not yet used state aid.

Figure 7.

Assessment of state aid to compensate for the loss of the revenues of SMEs in the Slovak Republic. Source: adjusted from data of SBA (2020c).

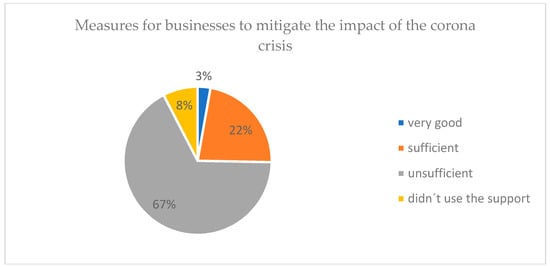

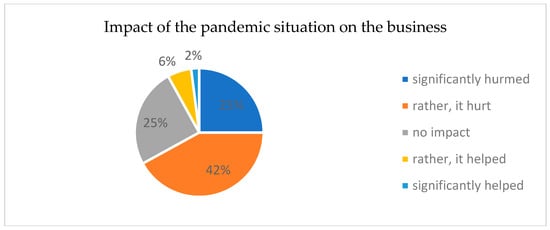

In the second survey, conducted in 2021, firms were asked to rate their assessment of measures to mitigate the impact of the coronacrisis. The results are presented in Figure 8. More than two thirds of SMEs (67.1%) rate the current economic measures for entrepreneurs aimed at mitigating the impacts of the coronacrisis as insufficient. Only 2.8% of entrepreneurs rate the measures as very good and more than a fifth (22.5%) as sufficient. A total of 7.6% of SMEs did not make use of the support measures.

Figure 8.

Assessment of measures for entrepreneurs in the Slovak Republic to mitigate the impact of the coronacrisis. Source: adjusted from data of SBA (2021b).

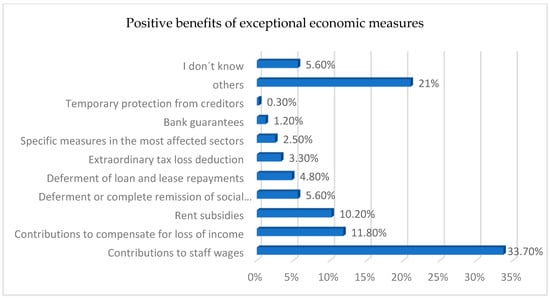

Figure 9 shows which of the exceptional economic measures to mitigate the negative effects of COVID-19 were most valued by the entrepreneurs. The most valued measure by the entrepreneurs surveyed was the wage subsidy for employees (33.7%), and the second most valued measure was the compensation for loss of income (11.8%). Conversely, the least valued measures were bank guarantees (1.2%) and temporary protection from creditors (0.3%). A total of 21.0% of SMEs mentioned the option ‘Other’ under economic measures. The most common option mentioned by respondents in the ‘Other’ category was ‘None of the above’. Contributions to employees’ salaries were most appreciated by small entrepreneurs (35.3%), those operating in the accommodation and catering sector (43.2%), those from the Banská Bystrica region (38.0%) or those operating for 3–5 years or 5–10 years (34.6%). Contributions to compensate for the loss of income were most appreciated by entrepreneurs in the hotels and restaurants sector (18.9%), in the regions of Bratislava and Trencin (15.3%), or those operating for 5 to 10 or more years (12.5%) or up to 29 years (16.1%). Rent subsidies were most appreciated by entrepreneurs in the trade sector (14.6%), aged up to 29 years (14.5%) or from the Žilina region (14.7%).

Figure 9.

Assessment of the contribution of the exceptional economic measures to mitigate the negative impacts of COVID-19 on SMEs in the Slovak Republic. Source: adjusted from data of SBA (2021b).

Deferral or total exemption from social contributions was most appreciated by small entrepreneurs (6.5%), those in the transport and information sector (7.9%), those from the Košice region (8.7%) or those who had been in business for less than 3 years (7.7%). The deferral of loan and lease repayments was most appreciated by medium-sized entrepreneurs (8.0%), those from the construction sector (6.0%), those in the Banská Bystrica region (6.5%) or those aged up to 29 years (16.1%). The extraordinary tax loss deduction was most appreciated by small entrepreneurs (6.0%), those in the trade sector (5.7%), those from the Banská Bystrica and Trnava regions (4.3%) or those aged 60 and over (8.8%). Specific measures in the most affected sectors were most appreciated by entrepreneurs in the accommodation and catering sector (8.1%) and agriculture (7.9%), from the Nitra region (4.4%), or aged 6–9 years (3.8%). Bank guarantees (1.2%) and temporary protection from creditors (0.3%) were considered less important measures in the fight against the crisis by the entrepreneurs surveyed.

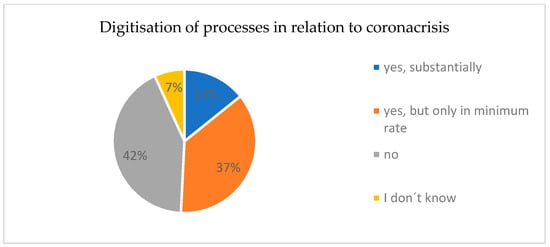

The survey also looked at the impact of the coronacrisis on initiating or supporting digitisation and its processes. The results are shown in the graph in Figure 10. For only 14.2% of SMEs, the coronacrisis had a fundamental impact on digitisation and related processes, and for more than a third (36.6%) of entrepreneurs it had a minimal impact. For 42.4% of SMEs, the economic crisis did not trigger any digitisation-related processes. A total of 60.8% of SMEs that have not digitised or have only digitised to a minimal extent consider that the nature of their business does not require digitisation and related processes. Digitisation was recorded mainly in the trade sector (60.7%), especially in Banská Bystrica (54.3%) and in the Košice and Bratislava regions (both 54.1%). The expansion of digitalisation was more pronounced among entrepreneurs who had been in business for 5 to 10 years (54.8%). The SMEs that did not digitise their processes in the context of the economic crisis (42.4%) operate mainly in the transport, information (55.1%) and industry (50.5%) sectors, are mainly in the Žilina (46.6%) and Trenčín (45.9%) regions, are more likely to have been in business for less than 3 years (46.7%), and are younger than 29 years of age (45.2%).

Figure 10.

Impact of the coronacrisis on the promotion of digitalisation in SMEs in the Slovak Republic. Source: adjusted from data of SBA (2021b).

The results of the survey on barriers to the digitisation of business processes are shown in Figure 11. High costs are perceived as a barrier by a fifth of SMEs (20.0%), while the time required is perceived as a barrier by 16.3% of respondents. A tenth (10.3%) of entrepreneurs consider that their employees do not have the necessary digital skills and therefore have not started to digitise more fundamentally. The fewest (4.2%) see legislation as an obstacle.

Figure 11.

Barriers to the digitalization of processes in SMEs in the Slovak Republic. Source: adjusted from data of SBA (2021b).

4.4. The Results of the Survey on the Opinions of Entrepreneurs in the Czech Republic

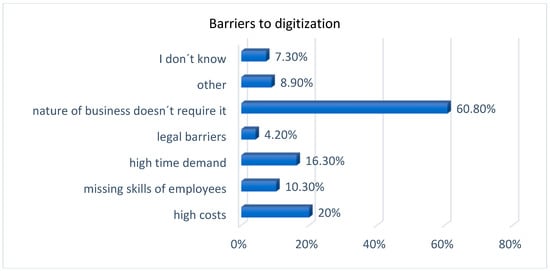

The survey was conducted after almost a year of the pandemic, and as expected, at least 2/3 of SMEs were negatively affected. An assessment of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the business of SMEs in the Czech Republic from the perspective of entrepreneurs is shown in the graphs in Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Impact of the pandemic situation on the business of SMEs in the Czech Republic. Source: adjusted from data of IPSOS (2021).

Figure 13.

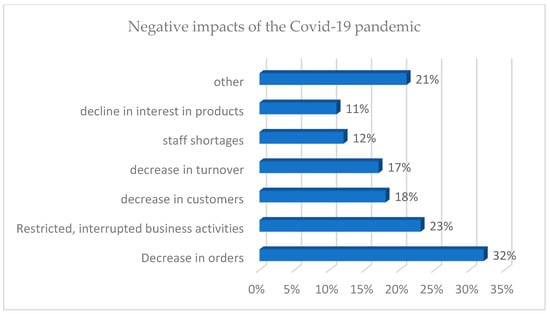

Negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in the SMEs in the CR. Source: adjusted from data of IPSOS (2021).

The results in Figure 12 show that two out of three SMEs were negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (67%). For 25% of respondents there was no impact on business change. A total of 8% of enterprises reported that the COVID-19 situation had helped them, often through increased sales through online channels. Most of the companies that were not affected by COVID-19 are simply in sectors that were not affected by the pandemic. For the time being, these include the construction industry, which is doing well thanks to long-term contracts, and the food industry. Sales are also increasing in the hygiene, drugstore, cleaning and disinfectant sectors, etc.

The second question asked for the specific negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the situation in SMEs. The results are presented in Figure 13. In addition to the difficulties associated with a reduction in activity (23% of respondents), companies were mainly faced with a reduction in orders (32%). Manufacturing and industry were most affected. These tend to be more complex, and at a time when the market situation cannot be read in a European or global context, business partners are not making strategic decisions about new orders, projects or new suppliers. Realistically, part of the industry, even abroad, is paralysed from this point of view. This has, of course, led to a fall in sales, as reported by 17% of respondents. Consumption has also fallen, with 18% of respondents reporting a loss of customers.

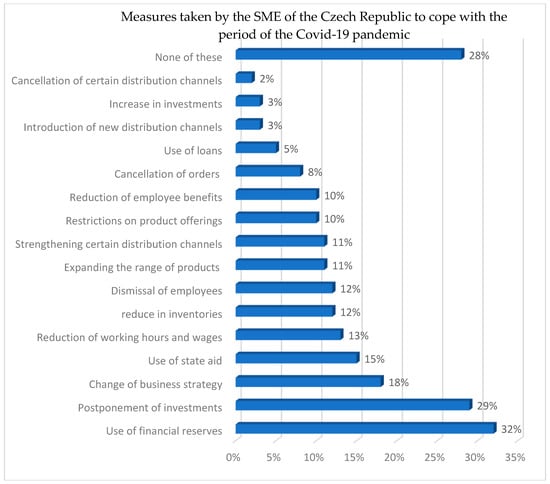

SMEs relied significantly more on themselves than on government support, which is typical of the SME segment. An overview of the measures implemented by entrepreneurs in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic is given in Figure 14. The results in Figure 14 show that 32% of the enterprises affected by the COVID-19 situation had to dip into their financial reserves and almost a third of them (29%) postponed their investments, which significantly slowed down their development. Government support was used by 15% of the sample. On the positive side, firms have shown a wide range of creativity in order to save their existence. A change in business strategy was implemented by 18% of enterprises, 18% of enterprises expanded the production of products and 17% of respondents changed their distribution channels. Measures that have had a negative impact on economic results include cancelling orders and limiting product ranges for 18% of respondents.

Figure 14.

Measures implemented by the MSP of the Czech Republic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Source: adjusted from data of IPSOS (2021).

In the context of the pandemic situation, enterprises have been very flexible in their response to employees and have tried to find ways to operate in a limited mode. On the positive side, companies have ‘discovered’, for example, the home-office (24%), although it is more complicated to run the business. A total of 12% of companies have also been forced to make redundancies, although this figure may seem surprisingly small. A total of 13% of companies have reduced wages and working hours and 10% have reduced benefits.

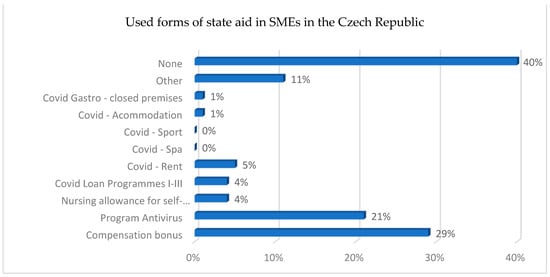

The survey also looked at the forms of government support received by SMEs. The results are presented in Figure 15. It is interesting to note that up to 40% of SMEs have not used any state aid scheme. The most commonly used schemes were the compensatory allowance (29%) and the antivirus programme (21%). For sole proprietors (SMEs), the most used scheme is the compensation bonus, in combination with the antivirus programme for the employees of sole proprietors and in combination with rent, although this is reflected rather sporadically in this sample. As far as companies are concerned, the antivirus programme was a common instrument of support, despite reservations about its establishment. The main problem was its instability, since it was approved 1–2 months in advance, which is somewhat removed from the reality of strategic decisions—the possible dismissal of an employee alone is a decision that affects the cash flow of the company for almost half a year. Credit support (COVID-19 loan programmes through the CMZRB) is surprisingly little represented in the sample, with only 4% of enterprises having used it.

Figure 15.

Forms of state aid used in SMEs in the Czech Republic. Source: adjusted from data of IPSOS (2021).

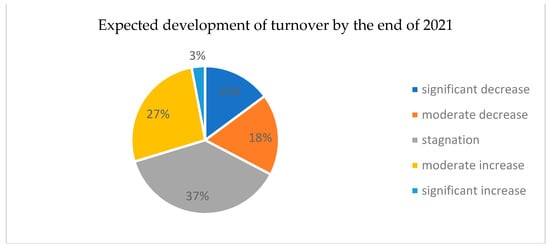

In view of the measures taken to cope with the coronacrisis and the possibility of using state aid, the survey also asked enterprises to comment on the expected development of turnover until the end of 2021. The results of the survey are shown in Figure 16. It shows that 33% of enterprises expect their turnover to decrease, but on the contrary, almost the same proportion, 29%, expect their turnover to grow in 2021. A third group of companies, with a share of 38%, expect no change in turnover. There is greater pessimism among those affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, with up to 41% of this group expecting a decline in turnover and only 23% expecting turnover to grow. More than half of enterprises (56%) expect it to take more than a year to recover from the effects of the pandemic.

Figure 16.

Turnover outlook for SMEs in the Czech Republic by the end of 2021. Source: adjusted from data of IPSOS (2021).

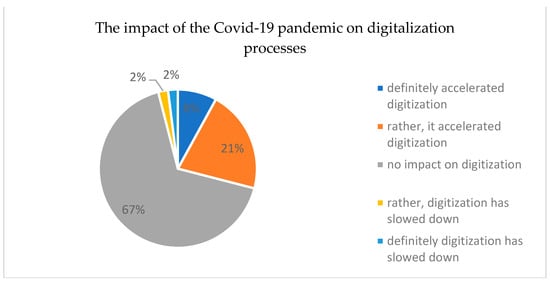

The survey also looked at how the pandemic situation affected the digitalisation process in SMEs. The COVID-19 situation clearly accelerated the use of communication platforms such as Zoom, Teams, Webex and Google Meetapod. It has also accelerated the online version of certain services and products in the education and consumer market. On the other hand, the survey shows that companies have been working with digitalisation for a long time and that the pace of digitalisation in manufacturing, for example, is not directly dependent on unexpected external factors. For services, the explanation is that they had already achieved a relatively high level of digitisation before the e-business era. The results of the responses shown in Figure 17 indicate that three out of ten enterprises have accelerated the digitisation process due to the impact of COVID-19. A total of 2/3 of the enterprises stated that the crisis did not affect the digitisation process and only 4% of the enterprises were slowed down by the crisis.

Figure 17.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on digitalization processes in SMEs in the Czech Republic. Source: adjusted from data of IPSOS (2021).

Unsurprisingly, the push for digital has increased in every category surveyed without exception. New technologies have helped many to avoid being left behind. It is interesting to note the difference in perceived pressure to digitise between sole traders and businesses (36 vs. 61%). One explanation could be the greater interactivity with the environment, which is of course due to the higher capacity of larger units. We expect at least the online communication platforms (Teams, Webex, Zoom, etc.) to remain, as they are fast, cheap, flexible and very effective in many situations.

At the end of the survey, respondents were given the opportunity to add their own comments on coping with the COVID-19 period. Savings, high fixed costs, limited investment in development and changes to currently established business models were the most common comments from companies. This is a very difficult period that will ultimately have some negative consequences, but may also mark a change for the better for many companies. This change may appear at least in terms of a reordering of priorities, perhaps with a focus on previously neglected segments of potential customers, but perhaps also in a form of patriotism as companies rediscover local suppliers rather than Asian ones.

4.5. The Comprehensive Comparison of the Results of the Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic

- The Status and development of the number of SMEs

The share of SMEs in the total number of business entities is identical in the Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic. The share of SMEs in the national value added (56%) is also the same and the same trend in the number of SMEs can be observed. In both countries, more enterprises were created than disappeared during the years of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, the total number of enterprises increased over time.

- The Negative effects of coronacrisis

The direct survey of entrepreneurs’ opinions shows that the negative impact of the coronacrisis was felt by many more SMEs in the Slovak Republic than in the Czech Republic (94.7% vs. 66%). While in Slovakia 72% of the enterprises felt a significant negative impact, in the Czech Republic it was only 25%. A total of 5% of Slovak SMEs and up to 25% of Czech SMEs did not experience any negative effects, while a further 8% of enterprises were even helped by the crisis. Specifically, the negative impact of the crisis on Czech entrepreneurs was manifested in a decrease in orders and business interruption, which led to a decrease in turnover for 17% of Czech enterprises and up to 94% of Slovak SMEs.

- Turnover development

The survey in the Slovak Republic did not assess specific negative effects, but the development of turnover during the individual waves of the crisis was evaluated, where 1/3 of the enterprises recorded and expected a decrease in turnover of more than 80% by the end of the year, and almost 2/3 of the enterprises also experienced a decrease. Only 3% of enterprises in the Slovak Republic recorded an increase in turnover, which is significantly lower than in the Czech Republic, where up to 1/3 of enterprises expect an increase in turnover and a further 37% of enterprises expect turnover to stagnate.

- Measures taken by enterprises to cope with the coronacrisis

Adapting the business to new market needs is the measure most frequently mentioned by Slovak SMEs (42%), while Czech entrepreneurs commented on more specific measures in this area, such as adapting distribution channels, expanding or limiting the offer and changing the business strategy, which was mentioned by a total of 55% of entrepreneurs. The use of financial savings from the past is more common in the Slovak Republic than in the Czech Republic (41.6% compared to 32%). Restrictive measures with regard to employees, such as lay-offs and the reduction of working time, and thus of wages, are applied almost twice as often in Slovak SMEs as in Czech SMEs (45.6% vs. 25%). Taking out new loans to finance business operations or requesting a deferral of the repayment of existing loans are measures taken by 19% of Slovak SMEs, while in the Czech Republic only 5% of enterprises mentioned the possibility of taking out loans.

- The Forms of State aid granted and used

The forms of state aid approved by the governments to support SMEs are comparable in Slovakia and the Czech Republic with one difference: unlike in Slovakia, the government of the Czech government has also introduced special three loan funds for SMEs. Direct subsidies to cover fixed costs and VAT reduction were the most preferred measures that 97% of Slovak entrepreneurs would welcome from the government, but these measures were not adopted by the Slovak government. Regarding the use of the available forms of state support, most Slovak entrepreneurs consider the support measures insufficient (half of the enterprises in 2020 and up to 2/3 of the enterprises at the end of the COVID-19 pandemic period). While 1/3 of Slovak enterprises did not use state support in 2020, only 8% did in 2021. In the Czech Republic, the share of SMEs that did not use state support was much higher, at 40%. The most used and valued were the contributions to staff salaries and compensation for loss of income. These forms of support were used by 45% of Slovak SMEs and 50% of Czech enterprises. Rent subsidies (5%) were used equally by Slovak and Czech entrepreneurs.

- The impact of the coronacrisis on the digitization processes of SMEs

In the area of support for the digitalization of SMEs, the COVID-19 pandemic had a positive impact on SMEs in both the Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic, while the effect on the acceleration of digitalization processes was more pronounced in Czech enterprises than in Slovak ones (23% vs. 14%). In up to 2/3 of Czech SMEs, and in only 42% of Slovak enterprises, the crisis had no impact on digitalisation processes.

5. Discussion

Already in the period before the pandemic, at the end of 2019, there was a decline in global demand, which was exacerbated by the pandemic measures in place. In the case of Slovakia and the Czech Republic, there was a decline in industrial production and further extensive restrictions in services and other sectors, and the overall situation led to a reduction in consumption, followed by a decline in production, which will be reflected in a decline in GDP in 2020. Sharp falls in demand and production due to blockades and supply chain disruptions led to the sharpest contraction in activity on record in 2020. Factories remained operational and were supported by strong export demand and restocking. Overall, the impact of the pandemic in 2020 was milder than the euro area average and smaller than initially expected. Restrictions also led to the suspension of more than 3000 transactions in early 2020. (Bečka 2020). After a slowdown in the first quarter, economic growth picks up in the second quarter of 2021, supported by the easing of measures and a gradual recovery in economic activity, especially in the services sector. The fiscal support will be partly offset by grants from the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility, which could reach EUR 6.3 bn over the period 2021–2026 (OECD 2020).

The negative impact of the crisis on the economies in 2020 and 2021 is also reflected in the evolution of the economic performance of the SME sector. In 2020, the growth trend of all major SME economic indicators is interrupted. The quarantine measures during the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on SMEs, which had problems with cash flow and maintaining employment. During the 2020 and 2021 pandemics, staff retention was a particular problem for hotels and restaurants. The construction and industrial sectors were among the other sectors with significant employment losses. The only sector of the economy where labour demand increased was information and communication services. As a result of the measures taken, the owners of retail businesses were also forced to partially or completely downsize, leading to a significant decline in retail sales, which fell more in 2020 than in 2019. Based on the results presented, it can be concluded that profit is the indicator most affected by the impact of the pandemic. Similarly to gross output and value added, the profit of SMEs in the SR experienced the largest decline in 2020. Compared to the previous year, only medium-sized enterprises reported higher profits in 2021, while micro and small enterprises in the SR experienced a more pronounced decline in profits than in 2020. The results of the primary research showed that the negative impact of the crisis on economic results, especially on sales, was felt more by Slovak entrepreneurs than by Czech ones. A larger share of Czech entrepreneurs expected an increase or maintenance of the level of turnover, while in Slovak SMEs a decrease in turnover prevails. The negative impact of the pandemic crisis on financial indicators was also pointed out by Du et al. (2023); Iancu et al. (2022) and Langworthy and Warnecke (2021).

The impact of the pandemic was also felt in business innovation activities. Small and medium-sized enterprises reassessed their planned innovation activities or suspended them altogether (SBA 2021b; IPSOS 2021). Even in 2021, enterprises did not have sufficient scope for a significant improvement in investment activity. This is because a stronger upturn in investment activity was hampered by input shortages (especially in industrial production, as a supply shock), but also by rapidly rising input prices, mainly due to the opening of the economy and the easing of anti-pandemic measures. A significant part of the services sector was closed. Consumption became more goods-oriented, leading to stronger growth in global demand for consumer goods and affecting the availability of some components and materials (SBA 2021a). According to the results of the presented primary research, the measures taken by Slovak and Czech SMEs to cope with the crisis were about the same proportion of positive and creative measures (about 50%), i.e., adapting the way of doing business and offering products to market changes and using financial savings for business operations and investments. Chomicki and Mierzejewska (2020); Thukral (2021) and Yaya et al. (2022) in their studies also pointed to the need to apply strategies oriented towards innovation, agility and creativity. Different results in the presented primary surveys were found in the use of restrictive measures towards employees, where almost twice as many Slovak as Czech entrepreneurs reduced the costs of employees either by dismissing them or by reducing working hours and wages.

In contrast to 2020, when the coronacrisis broke out, SMEs were already better able to cope with the negative effects of the pandemic in 2021, which was reflected in an increase in the number of active SMEs in Slovakia and the Czech Republic. The increase in SME activity was also driven by a number of government support measures, which were comparable in scope and intensity in both Slovakia and the Czech Republic. In the overview of measures taken by governments in 54 countries according to the OECD report (2020), the governments of Slovakia and the Czech Republic used only three of all of the forms of aid mentioned. Both Czech and Slovak entrepreneurs made the most use of and valued compensation for the loss of earnings in the form of subsidies and sickness benefits for the self-employed and subsidies for employees. The results differed with regard to the intensity of the use of state aid, where twice as many Czech entrepreneurs as Slovak entrepreneurs did not use any state aid. Satisfaction with the adequacy of state support measures was very low among Slovak SMEs. The inadequacy of government measures was also pointed out by Nicola et al. (2020); Goel et al. (2021) and Al-Fadly (2020) in their research. The acceleration or initiation of digitisation processes in SMEs as a result of the economic crisis, which was much more pronounced in Czech SMEs than in Slovak SMEs, has a positive impact on the transformation of the companies’ business.

Based on the publications, secondary research results and primary surveys, the main changes in the business of SMEs due to the coronacrisis can be summarized as follows:

- Economic downturn: SMEs were severely affected by business closures, travel restrictions and reduced demand for many goods and services.

- Financial problems: Limited access to finance and the liquidity crisis made it difficult for SMEs to obtain financial support to cover costs, especially when their revenues were falling.

- Changes in the working environment: Enterprises have had to adapt their working environment, often moving to homeworking, which has required investment in technology and new working practices.

- Demand and changes in consumer behaviour: Some sectors have benefited (e.g., online retail), while others (e.g., restaurants, tourism) have suffered a significant drop in demand.

- Regulatory changes: SMEs had to adapt to new regulations and safety guidelines, which often meant additional costs for compliance with hygiene standards and safety measures.

- Digital transformation: The pandemic has forced many SMEs to move quickly to online payments, e-commerce and other digital solutions to remain competitive.

- Supply chain changes: Travel restrictions and border closures have caused problems in supply chains, affecting the availability of raw materials and goods.

- Employment: many SMEs have had to reduce staff, cut working hours or close altogether, affecting employment in a range of sectors.

6. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic emergency has triggered specific needs for structural change in both businesses and institutions. In the context of the pandemic, it also appears that the country’s technological readiness and related digital transformation may be key in the short term. On the other hand, the deteriorating investment climate may slow down the necessary structural changes. One of the most vulnerable and hardest hit groups of companies are SMEs, which in some cases have been existentially affected by the anti-pandemic measures. The impact of the coronavirus has also been reflected in the economic performance of the SME sector. The lack of demand, low liquidity, non-negligible fixed costs and resulting financial problems have been a burden for many of them due to the coronavirus crisis. In order to mitigate the negative financial effects of the crisis, governments have adopted a number of support measures for SMEs. However, according to a survey of the views of entrepreneurs, the majority of SMEs in the Slovak Republic did not consider the state aid to be sufficient and a fifth of entrepreneurs did not make use of it. In the Czech Republic, up to 40% of entrepreneurs did not make use of state support and there was also little interest in the new loan funds, as small entrepreneurs were wary of taking on more debt in the uncertain period of the crisis.

At the same time, in the context of the EU’s objectives for the coming decades, it is crucial to support the transition not only to a digital but also to a sustainable economy by increasing the number of SMEs using digital technologies as well as the number of SMEs adopting sustainable business practices and models while maintaining their competitiveness. In line with EU objectives, SMEs thus make an important contribution to a resource-efficient and climate-neutral economy with a flexible approach to digitalisation. The pandemic has forced SMEs to adapt and look for new ways to operate and stay in business. Some businesses have been able to adapt flexibly to the new conditions and even increase their competitiveness, while others are still struggling to recover and adapt to the new business environment. Changes in consumer behaviour and competition have meant that SMEs have had to adapt their offerings and strategies to meet the growing demand for digital and online services, as well as for environmentally and socially responsible products and services.

The financial crisis has shown that the need to learn and adapt is essential for survival. The increase in the number of SMEs, the increase in production and value added in SMEs in the Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic in 2021 indicate the ability of SMEs in the Slovak Republic to adapt to change. Business agility, as the need to adapt to new conditions, to react quickly and flexibly, or to focus on creating value for the customer, is in demand in various sectors. While a small organisation is often naturally agile, larger medium and large organisations need to increase their agility as the uncertainty, ambiguity and variability of problems and the environment increases.

The implications of the study can be seen in providing empirical results of changes in the business of SMEs due to the COVID-19 pandemic in two EU countries. The results of the study also reveal the perception of state support during the coronacrisis by SME managers, which can be used as feedback for governments and their applied mitigation measures. According to Slovak and Czech entrepreneurs, governments should provide more support in the form of direct subsidies for fixed costs or VAT reduction to help SMEs overcome financial problems due to reduced sales and liquidity. The paper contributes to the existing knowledge by summarising changes in SME business during the coronacrisis and the directions of future entrepreneurial activities.

One of the limitations of the study is the fact that the effects of the coronacrisis were still evolving when the primary surveys were conducted, and not all changes in business may have been covered. Another limitation can be the use of a quantitative research method, which doesn’t make it possible to identify specific factors and obstacles that companies had to overcome during the coronacrisis. A revised version of the questionnaire could be used in future research. Further research will also focus on qualitative research into the ability of SMEs to cope with unpredictable change and the barriers needed to build their agility. Detailed case studies are needed to see how SMEs can cope with crisis periods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, review and editing A.J.S.; formal analysis, resources, data curation, V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was elaborated within the framework of the project No. 1/0333/22 under the VEGA agency, Slovakia.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found in the official statistical databases of the Czech Statistical Bureau (https://vdb.czso.cz/vdbvo2/faces/cs/index.jsf?page=vystup-objekt&z=T&f=TABULKA&pvo=ORG05&skupId=3773&katalog=33695&&v=v7__KODAKT__571__1&str=v386&kodjaz=203) (accessed on 25 October 2023), official reports and surveys of the Slovak Business Agency (https://www.sbagency.sk/stav-maleho-a-stredneho-podnikania (accessed on 20 October 2023), https://www.sbagency.sk/analyzy-a-prieskumy-podnikatelskeho-prostredia) (accessed on 20 October 2023), survey of the IPSOS agency (https://amsp.cz/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Ipsos-pro-AMSP_Covid-a-Zm%C4%9Bny-v-podnik%C3%A1n%C3%AD_FINAL-_TZ-1.pdf) (accessed on 5 November 2023), and official reports of the OECD (https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/Cz-Rep.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2023), https://oecd.dam-broadcast.com/pm_7379_119_119680-di6h3qgi4x.pdf) (accessed on 15 November 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Abd Aziz, Nurul-Ashykin, Mohd Hizam-Hanafia, Hasif-Rafidee Hasbollah, Zuraimi-Abdul Aziz, and Nik-Syuhailah-Nik Hussin. 2022. Understanding the Survival Ability of Franchise Industries during the COVID-19 Crisis in Malaysia. Sustainability 14: 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhussein, Tala, Husam Barham, and Saheer Al-Jaghoub. 2021. The effects of COVID-19 on small and medium-sized enterprises: Empirical evidence from Jordan. Journal of Enterprising Communities-People and Places in the Global Economy 17: 334–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, Nawal-Abdalla, and Ghadah Alarifi. 2021. Innovation practices for survival of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the COVID-19 times: The role of external support. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 10: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Fadly, Ahmad. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on SMEs and employment. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 8: 629–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hakimi, Mohamed A., Moad-Hamod Saleh, and Dileep B. Borade. 2021. Entrepreneurial orientation and supply chain resilience of manufacturing SMEs in Yemen: The mediating effects of absorptive capacity and innovation. Heliyon 7: e08145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasoiu, Narcis. 2021. Global Economy in the COVID-19 Era. The Impact of the Pandemic on the Economic and Financial Systems. In Resilience and Economic Intelligence through Digitalization and Big Data Analytics. Book Series International Conference on Economics and Social Sciences. Warsaw: Sciendo, pp. 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, Muhammad-Farhan, Benjiang Ma, and Luqman Shahzad. 2020. A brief review of socio-economic and environmental impact of Covid-19. Air Qual Atmos Health 13: 1403–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bečka, Michal. 2020. Vplyv súčasnej globálnej pandémie SARS-CoV-2 na zamestnanosť v ekonomike Slovenskej republiky. Economic Review 49: 188–214. [Google Scholar]

- Birbirenko, Svitlana, Yuliia Zhadanova, and Natalia Banket. 2020. Influence of pandemic of coronavirus infection COVID-19 on economic resilience of Ukrainian enterprises. Economic Annals-XXI 183: 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Wanyi, Rong Jin, and Yuchuan Xie. 2023. Strategic flexibility or persistence? Examining the survival path of export enterprises under COVID-19. Chinese Management Studies 17: 320–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomicki, Michal, and Katarzyna Mierzejewska. 2020. Preparation of Polish enterprises to accept remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic. E-mentor 5: 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clampit, Jack-A., Melanie-P. Lorenz, John-E. Gable, and Jim Le. 2022. Performance stability among small and medium-sized enterprises during COVID-19: A test of the efficacy of dynamic capabilities. International Small Business Journal-Researching Entrepreneurship 40: 403–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czech Statistical Office (CSO). 2023a. Birth and Death of Businesses. Public Database. Available online: https://vdb.czso.cz/vdbvo2/faces/en/index.jsf?page=vystup-objekt&z=T&f=TABULKA&pvo=ORG09&skupId=3549&katalog=33695&&str=v719&kodjaz=203 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Czech Statistical Office (CSO). 2023b. Businesses by Size of Business (Number of Employees). Public Database. Available online: https://vdb.czso.cz/vdbvo2/faces/en/index.jsf?page=vystup-objekt&z=T&f=TABULKA&pvo=ORG05&skupId=3773&katalog=33695&&v=v7__KODAKT__571__1&str=v386&kodjaz=203 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Du, Lijie, Assif Razzaq, and Muhammad Waqas. 2023. The impact of COVID-19 on small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Empirical evidence for green economic implications. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 30: 1540–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyduch, Wojciech, Pawel Chudziński, Szymon Cyfert, and Maciej Zastempowski. 2021. Dynamic capabilities, value creation and value capture: Evidence from SMEs under Covid-19 lockdown in Poland. PLoS ONE 16: e0252423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasth, Jonas, Viktor Elliot, and Alexander Styhre. 2022. Crisis management as practice in small- and medium-sized enterprises during the first period of COVID-19. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 30: 161–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, Natalia Martín, and Isabella Moder. 2021. The Scarring Effects of COVID-19 on the Global Economy. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/scarring-effects-covid-19-global-economy (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Gashi, Albane, Iliriana Sopa, and Ymer Havolli. 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on economic aspects of business enterprises: The case of Kosovo. Management-Journal of Contemporary Management Issues 26: 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershenfeld, Neil. 1999. The Nature of Mathematical Modeling. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 205–208. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, Rajeev K., James W. Saunoris, and Srishti S. Goel. 2021. Supply chain performance and economic growth: The impact of COVID-19 disruptions. Journal of Policy Modeling 43: 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Binlei, Shurui Zhang, Lingran Yuan, and Kevin Z. Chen. 2020. A balance act: Minimizing economic loss while controlling novel coronavirus pneumonia. Journal of Chinese Governance 5: 249–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacob, Andreea-Teodora, Silvia Elena Iacob, and Sorin Nastasia. 2021. Restarting COVID-19-Affected Economies. In Resilience and Economic Intelligence through Digitalization and Big Data Analytics. Book Series International Conference on Economics and Social Sciences. Warsaw: Sciendo, pp. 277–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iancu, Anica, Luminita Popescu, Anca Antonaeta Varzaru, and Costin Daniel Avram. 2022. Impact of Covid-19 Crisis and Resilience of Small and Medium Enterprises. Evidence from Romania. Eastern European Economics 60: 352–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPSOS. 2021. Covid-19 and Changes in Business. Available online: https://amsp.cz/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Ipsos-pro-AMSP_Covid-a-Zm%C4%9Bny-v-podnik%C3%A1n%C3%AD_FINAL-_TZ-1.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Khan, Karamat, Sheng Liu, Baowei Xiong, Leihao Zhang, and Chuntao Li. 2022. Innovation to Immune: Empirical Evidence From COVID-19 Focused Enterprise Surveys. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 850842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langworthy, Melissa, and Tonia Warnecke. 2021. “Top-Down” Enterprise Development and COVID-19 Impacts on Gulf Women. Journal of Economic Issues 55: 325–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Thanh Tiep, and Van Kha Nguyen. 2022. Effects of quick response to COVID-19 with change in corporate governance principles on SMEs’ business continuity: Evidence in Vietnam. Corporate Governance. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, Manfred, Mengyu Li, Arunima Malik, Francesco Pomponi, Ya-Yen Sun, Thomas Wiedmann, Futu Faturay, Jacob Fry, Blanca Gallego, Arne Geschke, and et al. 2020. Global socio-economic losses and environmental gains from the Coronavirus pandemic. PLoS ONE 15: e0235654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Bo, and Zeshui Xu. 2022. A comprehensive bibliometric analysis of financial innovation. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 35: 367–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Li, Junlin Peng, Jing Wu, and Yi Lu. 2021. Perceived impact of the Covid-19 crisis on SMEs in different industry sectors: Evidence from Sichuan, China. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 55: 102085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miocevic, Dario. 2022. Don’t get too emotional: How regulatory focus can condition the influence of top managers’ negative emotions on SME responses to economic crisis. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 40: 130–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, Makarand Amrish, Lydia Hanks, and Mingming Cheng. 2021. Sharing economy research in hospitality and tourism: A critical review using bibliometric analysis, content analysis and a quantitative systematic literature review. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 33: 1711–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Jinjin. 2020. Research on the impact of COVID19 on global economy. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 546: 032043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MPO CR. 2021. Strategy of SME Support in the Czech Republic for 2021–2027. Available online: https://www.mpo.cz/assets/cz/rozcestnik/pro-media/tiskove-zpravy/2021/3/Strategie-podpory-MSP-v-CR-pro-obdobi-2021-2027.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Nicola, Maria, Zaid Alsafi, Catrin Sohrabi, Ahmed Kerwan, Ahmed Al-Jabir, Christos Iosifidis, Maliha Agha, and Riaz Agha. 2020. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International Journal of Surgery 78: 185–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]