Career Trajectories of Higher Education Graduates: Impact of Soft Skills

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Soft Skills as Determinants of Employability: Literature Review

2.1. The Importance of Soft Skills in the Workplace

- ⮚

- O describes a person’s tendency to think in an abstract and complex way. Those with the highest scores tend to be creative, adventurous, and intellectual. However, those with low scores tend to avoid the unknown and follow traditional methods.

- ⮚

- C describes a person’s ability to exercise self-discipline and control in order to pursue their goals.

- ⮚

- E describes a person’s tendency to seek stimulation from the outside world, attracting the attention of others. Extraverts actively engage with others. However, introverts conserve their energies and do not work to gain social rewards.

- ⮚

- A describes a person’s tendency to put the needs of others before their own and to cooperate.

- ⮚

- N describes the tendency to experience negative emotions: fear, sadness, shame, anxiety.

2.2. Soft Skills as Determinants of Employability

- ⮚

- Complex problem solving: Knowing how to find solutions to the problems faced by the company is a valuable asset. As challenges become increasingly complex and require global responses, individuals who facilitate solutions make a difference.

- ⮚

- Flexibility: Organizations are changing rapidly, and it is important for individuals to be flexible and adaptable in their daily work. They need to be able to adapt their work speed quickly and not feel disconcerted by a sudden change in their habits.

- ⮚

- Critical thinking: Questioning is the basis of all development. Being able to “criticize objectively”, in a logic of continuous improvement, allows to learn and to question the established models, without reproducing the mistakes of the past. Companies wishing to evolve have every interest in calling on people who bring a fresh and critical perspective.

- ⮚

- Creativity: Coming up with new things is better. Recruiting creative individuals who “think out of the box” allows companies to better face their competitors.

- ⮚

- Emotional intelligence: The ability to identify, understand and control one’s emotions and those of the people around us is also important. It allows not only to be more fulfilled in one’s daily life, but also to better understand others (one’s team, manager, clients).

- ⮚

- Ability to manage a negotiation: Negotiation is an essential step for any company. Having employees who master the art of persuasion and know how to negotiate in a “win–win” logic is crucial. Negotiating well means knowing your speech and your product by heart, but it also means knowing how to listen to the other person.

- ⮚

- Customer Service Skills: This human skill is based on active listening to the other person (especially when it is a customer). The sense of customer service is the ability to provide a clear, precise and appropriate response to the needs of its customers.

- ⮚

- Judgment and decision making: Being flexible, creative and critical, while understanding others, is a strong behavioral skill. However, if you want to be a key player in the company, you also need to be able to make the right decisions.

- ⮚

- Team spirit: To maintain a healthy and sustainable dynamic, it is essential that all employees are driven by a common project, which is the success of the company. Recruiting people who like to play collectively and succeed together makes it possible to obtain a team sharing the same values of mutual aid, solidarity and cohesion.

- ⮚

- Team Management: The ability to manage is not only for people who have managerial responsibilities over their employees. Leadership is a soft skill to possess, as it allows one to effectively direct the efforts of a group in a common direction leading to the achievement of objectives.

2.3. Theoretical Conclusions

- i.

- Soft skills determine the career paths of higher education graduates.

- ii.

- Do soft skills vary from an open access institution to a regulated institution?

- iii.

- Soft skills are what distinguish one individual from another when it comes to finding a job.

- iv.

- They are not only determinant for hiring, but also for career opportunities, hence their great importance.

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. Methodology

- i.

- The first step

- ii.

- The second step

3.2. Data Mobilized

4. Resultants

4.1. Description of the Sample

- ⮚

- For French, 29% of respondents have an excellent level of proficiency, 52% have a high level and 19% have an average level.

- ⮚

- With regard to communication skills in English, the level is low to average for 82% of respondents. Only 18% have a more than average level.

- ⮚

- In terms of communication skills, 77% of respondents had a low level while 23% had a good level.

- ⮚

- In terms of computer knowledge, 83% of respondents stated that they had poor knowledge, and only 17 had good knowledge.

- ⮚

- In terms of practical knowledge, 83% of the respondents stated that they had poor knowledge and 17% had good knowledge. During their studies, 60% of the respondents stated that they had done internships in preparation for their studies.

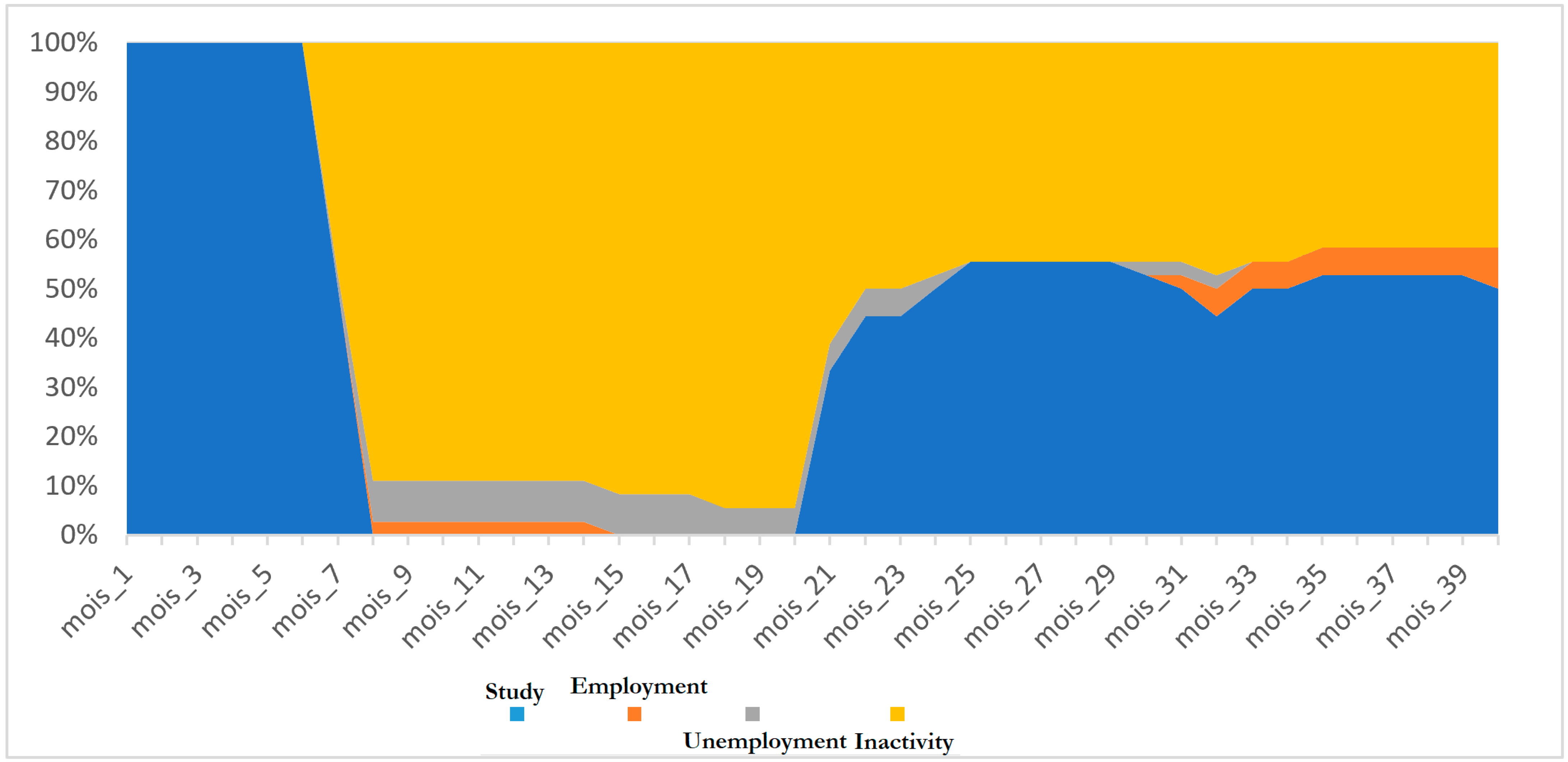

4.2. Trajectory Typology

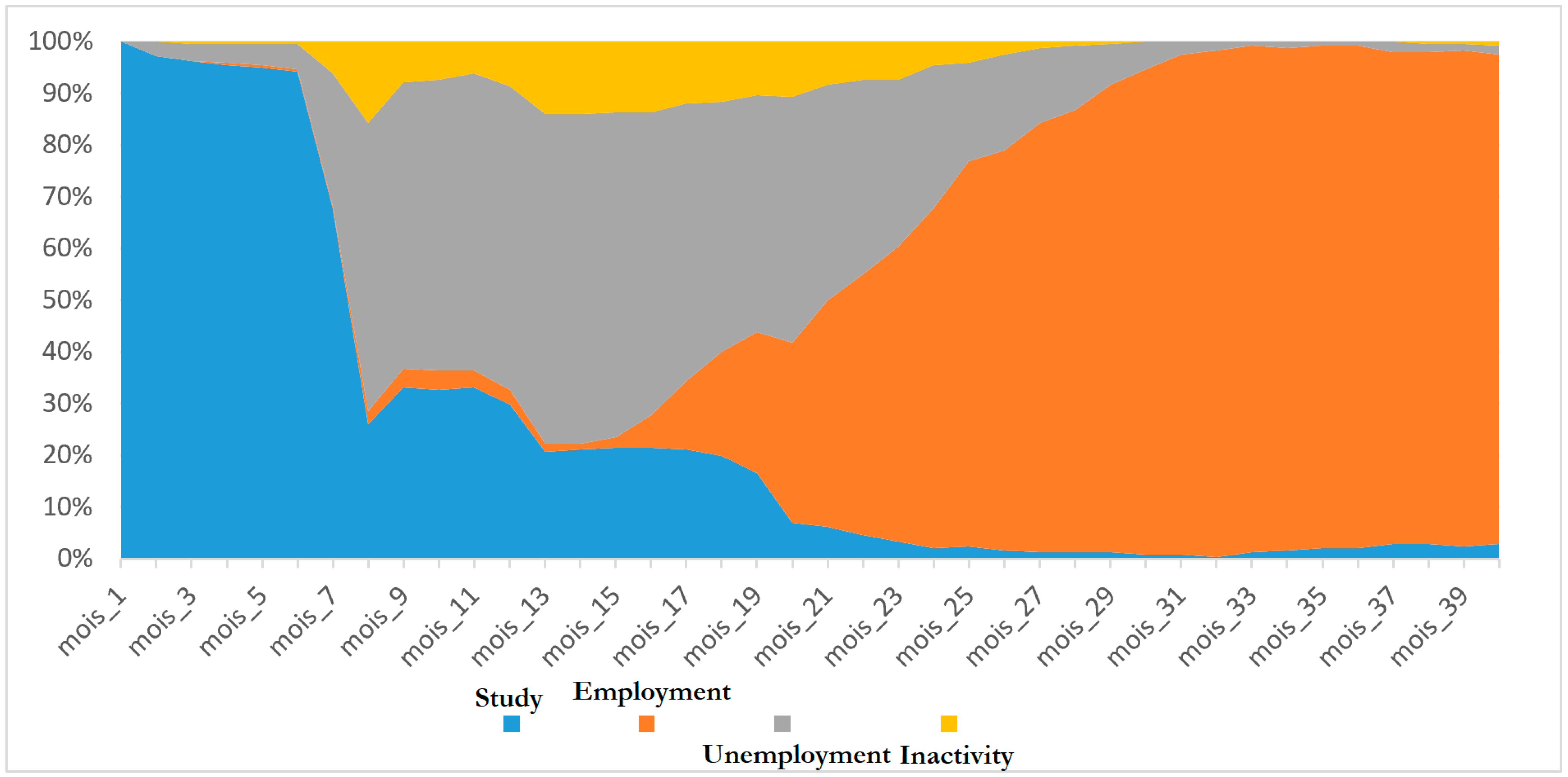

- Class 1: Transitions to Employment

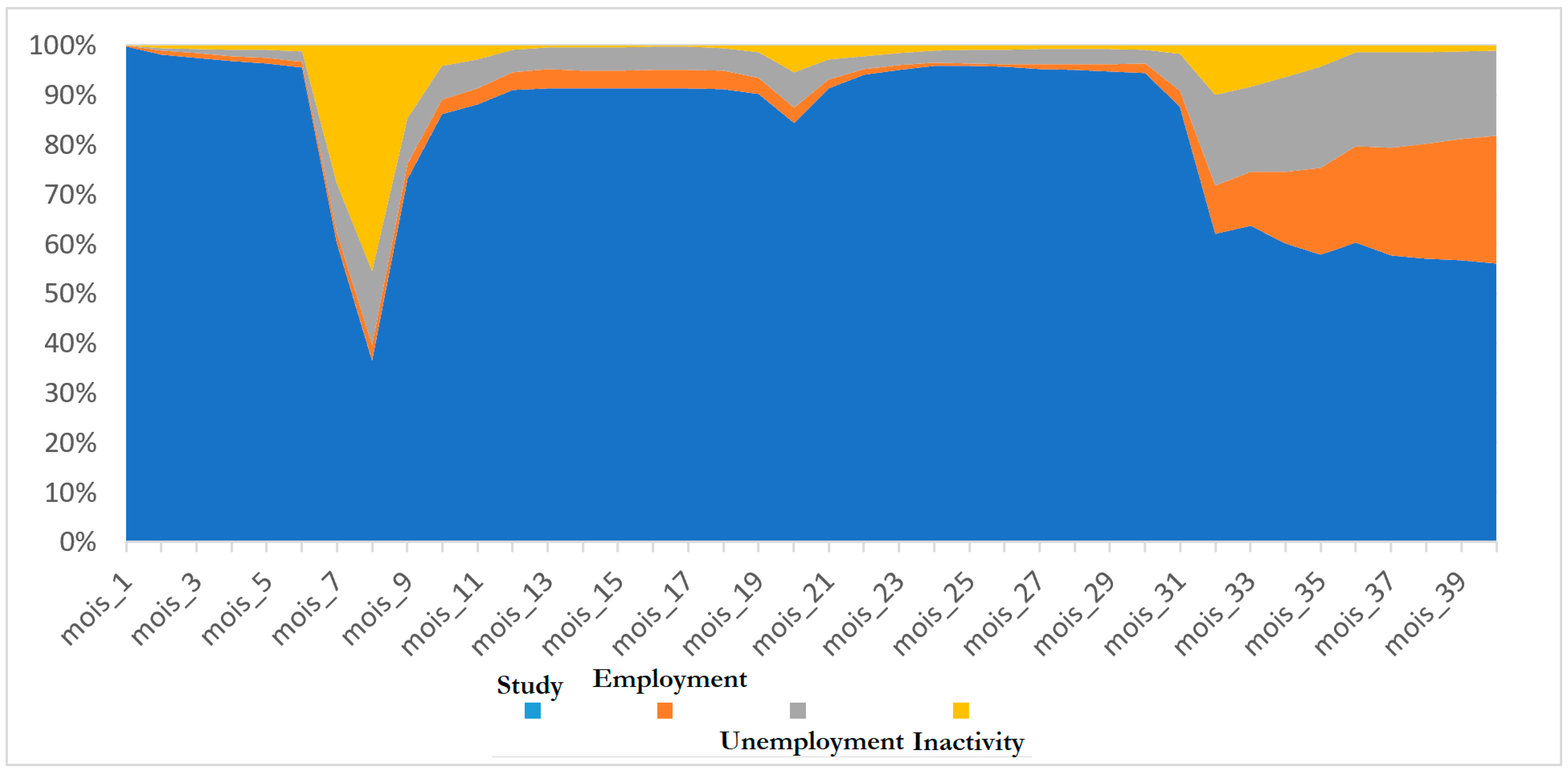

- Class 2: Ongoing studies

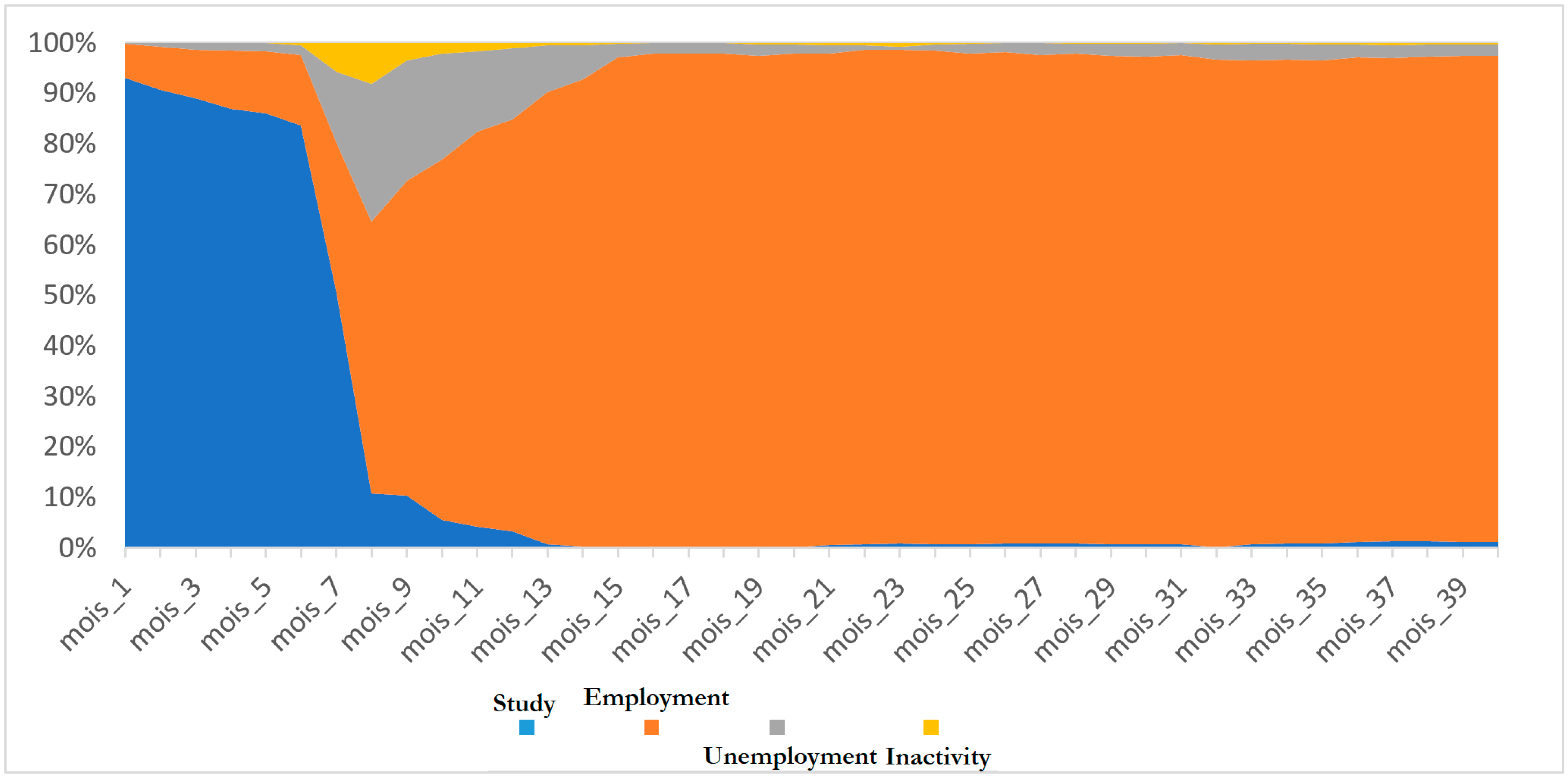

- Class 3: Rapid transitions to sustained employment

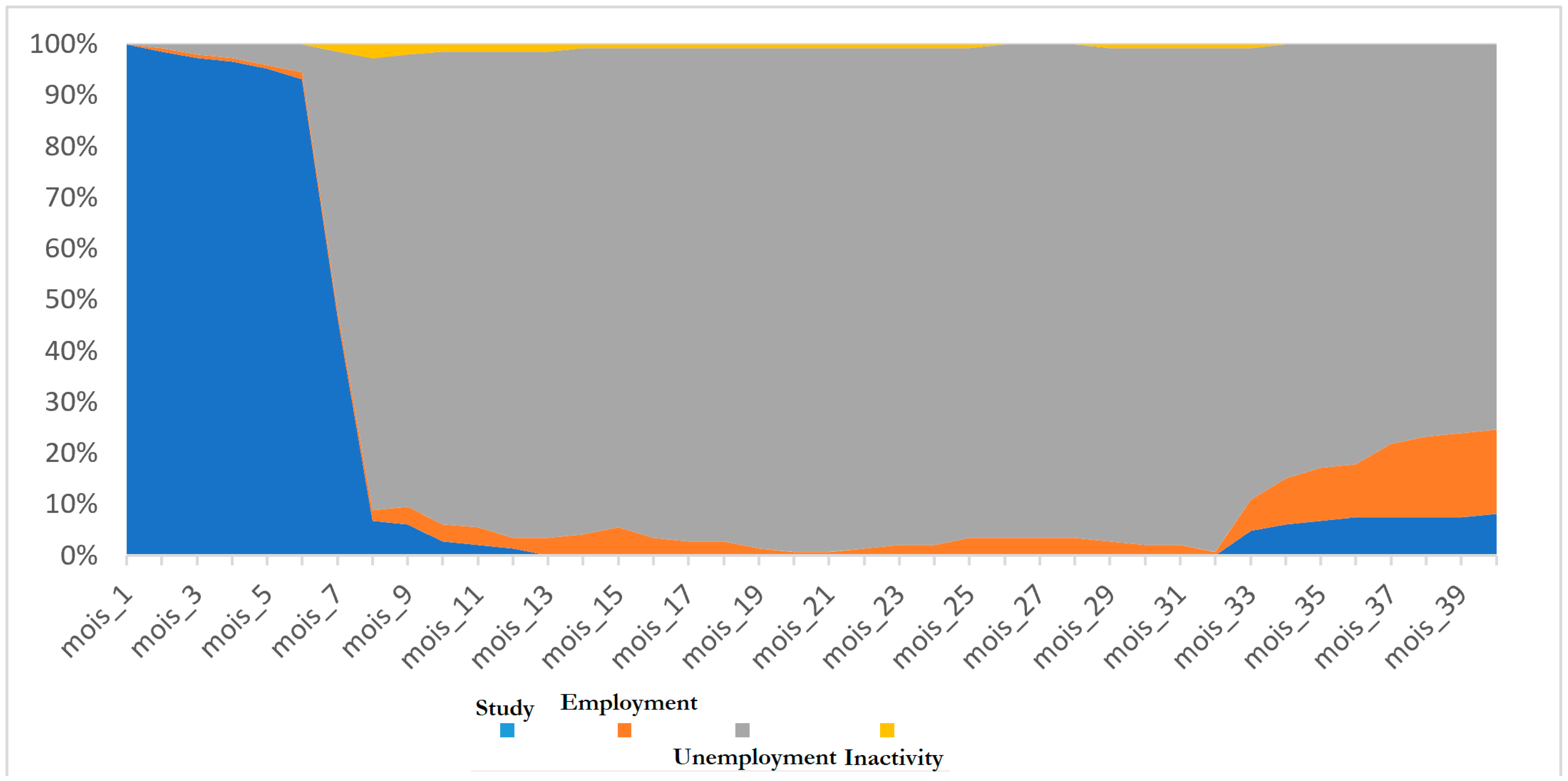

- Class 4: Prevailing Unemployment

- Class 5: Transitions to discouragement “inactivity” and back to school

- ⮚

- The majority of graduates (80% men and 74% women) are classified in the 2nd or 3rd typology.

- ⮚

- In relation to the type of institution, the analysis of the results shows that 57% of the graduates of the Faculties of Science are committed to continuing their studies and that 25% have been able to join the labor market on a permanent basis. The majority of graduates from the FSJES (38%) are engaged in sustainable work, and slightly less than a third (30%) are engaged in further studies. FLSH graduates are characterized by both a high rate of sustainable integration into the labor market (41%) and a high rate of unemployment (25%). This paradox can be explained in part by the fact that the FLSH contains heterogeneous disciplines (language disciplines in high demand on the labor market and humanities disciplines in low demand). Overall, graduates from the Faculty of Science prefer to continue their studies. On the other hand, graduates from other institutions prefer work.

- ⮚

- As expected, graduates from institutions with regulated access are more likely to be in permanent employment (40.37%) or in transition to employment (18.35%), with very low rates of unemployment and inactivity (3.12% and 1.47%, respectively). The trajectories of graduates from open-access institutions are characterized by the predominance of unemployment (11.99%) and continued study (37.64%).

- ⮚

- In relation to family situations, single students are more likely to study, while the others prefer to find a job.

- ⮚

- By type of degree, unemployment is very high among graduates (13.01%). On the other hand, 88% of the holders of a master’s degree from the FST and the ENCG have a permanent job. Doctorate holders are either engaged in sustainable employment (47%) or are in transition to employment.

- ⮚

- In relation to the type of baccalaureate, the studies suggest that 28% of literary baccalaureate holders are classified in the 4th class (literary graduates are more affected by long-term unemployment than others). One in five graduates do not master French and 14% of graduates with communication problems are at risk of long-term unemployment.

- ⮚

- It should also be noted that 16% of the laureates without an internship and 19% of the laureates without (practical) experience are classified in a typology characterized by long-term unemployment.

- ⮚

- The level of education of the parents has an impact on the career path of the laureates. Laureates whose fathers’ professions are not line management and executive and whose mothers are unemployed or inactive are more exposed to unemployment (13%). The survey data also suggest that 15% of the laureates whose fathers’ educational level is no level or primary are classified in the trajectory characterized by long-term unemployment.

- ⮚

- It should also be noted that 12% of the laureates whose mother’s educational level is without level or primary are classified in the trajectory characterized by long-term unemployment.

- ⮚

- A total of 15% of the laureates whose parents (father and mother) have no schooling or primary schooling are classified in the trajectory characterized by long-term unemployment.

- ⮚

- A total of 42% of the laureates whose father’s educational level is more than primary school prefer to continue their studies, while 41% of the other laureates whose father’s educational level is no level or primary school prefer to enter the labor market.

- ⮚

- Our analyses suggest that the career paths of women and men are different. Indeed, women are more exposed to long-term unemployment than men.

- ⮚

- Moreover, 12 percent of women’s career paths are characterized by long-term unemployment. Additionally, nearly two thirds (65%) of the laureates of the 4th typology are women. A total of 77% of these women are aged 26 and over and nearly three quarters of them are single. By type of institution, 88% of the women are from open access institutions. The results also suggest that 11% of female FLSH awardees are classified in typology 5 (Table 8).

4.3. Individual Determinants of Typical Trajectories

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The survey of insertion of graduates of higher education (ES), conducted in 2020 by the INE, covered a representative sample of 12,958 graduates of higher education, or 11.7% of all graduates of higher education for the year 2014. These graduates are from the twelve public universities of Morocco, Al Akhawayn University, and non-university institutions, particularly the five institutions providing technical and engineering training. |

References

- Ait Soudane, Jalila, Sanae Solhi, Meryem Chiadmi, and Karima Ghazouani. 2020. Les déterminants de l’accès a l’emploi chez les jeunes diplômes de l’enseignement supérieur au Maroc. Revue Française d’Economie et de Gestion 1: 123–51. [Google Scholar]

- Albandea, Inès, and Jean-François Giret. 2016. L’effet des soft-skills sur la rémunération des diplômés. Net.Doc, n°149, 31p. Available online: https://www.cereq.fr/leffet-des-soft-skills-sur-la-remuneration-des-diplomes (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Allport, G. W. 1935. Attitudes. In A Handbook of Social Psychology. Worcester: Clark University Press, pp. 798–844. [Google Scholar]

- Bauvet, Sébastien. 2019. Les enjex sociaux de la reconnaissance des compétences transversales. Available online: https://www.cairn.info/revue-education-permanente-2019-1-page-11.htm (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Benabid, Assia. 2017. Soft Skills: Effet De Mode, D’influence Ou Notion Incontournable? Revue de l’Entrepreneuriat et de l’Innovation 1: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, Peter T. van den, and Mandy E. G. van der Velde. 2005. Relationships of Functional Flexibility with Individual and Work Factors. Journal of Business and Psychology 20: 111–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougroum, Mohammed, and Aomar Ibourk. 2003. Les effets des dispositifs d’aide à la création d’emplois dans un pays en développement, le Maroc. Revue Internationale du Travail 142: 371–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougroum, Mohammed, Aomar Ibourk, and Ahmed Trachen. 2002. L’insertion des diplômés au Maroc: Trajectoires professionnelles et déterminants individuels. Available online: https://regionetdeveloppement.univ-tln.fr/wp-content/uploads/R15_Bougroum.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1980. Le capital social. Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 31: 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, Samuel, Herbert Gintis, and Melissa Osborne. 2001. The determinants of earnings: A behavioral approach. Journal of Economic Literature 39: 1137–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassard, Yves, and Amitié Henri Bosco. 1998. L’émergence du concept d’employabilité. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/L’%C3%A9mergence-du-concept-d’employabilit%C3%A9-Chassard-Bosco/4ce66fdeef63b3274dbebd06a0a2620b85a59fd2 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Coleman, James S. 1988. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology 94: S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grip, Andries, Jasper Van Loo, and Jos Sanders. 2004. The Industry Employability Index: Taking account of supply and demand characteristics. International Labour Review 143: 211–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deming, David J. 2017. The Growing Importance of Social Skills in the Labor Market. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132: 1593–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Vocational Education. 2017. Benchmark sur les compétences clés. Rabat: Maroc. [Google Scholar]

- Duru-Bellat, Marie. 2015. Les compétences non académiques en question. Formation Emploi 130: 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elayanoui, K., and A. Ibourk. 2018. Déterminants de l’insertion des diplômés universitaires: Une modélisation à l’aide des arbres de. Rabat: OCP Policy Center. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Francis, Steven McIntosh, and Anna Vignoles. 1999. Overeducation and Skills-Clarifying the Concepts (No. dp0435). London: Centre for Economic Performance, LSE. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman, Leslie Morrison, and Ingrid Schoon. 2013. The Impact of Non-Cognitive Skills on Outcomes for Young People. Education Endowment Foundation. Available online: http://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/uploads/pdf/Non-cognitive_skills_literature_review.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Han, Shin-Kap, and Phyllis Moen. 1999. Work and Family Over Time: A Life Course Approach. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 562: 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, James J., Jora Stixrud, and Sergio Urzua. 2006. The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market. Journal of Labor Economics 24: 411–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibourk, Aomar. 2014. Analyse des comportements des jeunes diplômés marocains en matière de recherche d’emploi. Une investigation empirique. Critique Economique 31: 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ibourk, Aomar. 2015. Le défi de l’employabilité des jeunes dans les pays arabes méditerranéens le rôle des programmes actifs du marché du travail. Turin: ETF-European Training Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Ibourk, Aomar, and Sergio Perelman. 2001. Frontière d’efficacité et processus d’appariement sur le marché du travail marocain. Economie et Prévision 150–51: 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ibourk, Aomar, and Zakaria Elouaourti. 2023. Revitalizing Women’s Labor Force Participation in North Africa: An Exploration of Novel Empowerment Pathways. International Economic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, Oliver P., and Sanjay Srivastava. 1999. The Big Five Trait Taxonomy: History, Measurement, and Theoretical Perspectives. Available online: https://personality-project.org/revelle/syllabi/classreadings/john.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Katz, Robert L. 1974. Skills of an Effective Administrator. Brighton: Harverd Business Review. [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist, Erik, and Roine Vestman. 2011. The Labor Market Returns to Cognitive and Noncognitive Ability: Evidence from the Swedish Enlistment. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3: 101–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Robert E., Jr. 1988. On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics 22: 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manach, Marlène, Catherine Archieri, and Jérôme Guérin. 2019. Définir et repérer la dimension sociale de la compétence. Education Permanente 2019: 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauléon, Fabrice, Julien Bouret, and Jérôme Hoarau. 2014. Le Réflexe Soft Skills. Paris: Dunod. [Google Scholar]

- Morlaix, Sophie, and Nesha Nohu. 2019. Compétences transversales et employabilité: De l’université au marché du travail. Education Permanente 1: 109–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretti, Jean-Marie. 2008. Dictionnaire des Ressources Humaines, 5ème ed. Gestion: Vuibert. [Google Scholar]

- Quintini, Glenda, and Thomas Manfredi. 2009. Going Separate Ways? School-to-Work Transitions in the United States and Europe. Documents de travail de l’OCDE sur les questions sociales, l’emploi et les migrations, n° 90, Éditions. Paris: OCDE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Germes, Eve. 2004. L’employabilité, une nouvelle dimension pour la GRH? Paper presented at Actes du XVe Congrès de l’AGRH, Montréal, QC, Canada, September 1–4; Available online: https://www.agrh.fr/assets/actes/2004saint-germes084.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Sauret, C., and D. Thierry. 1994. Vous avez dit employabilité? Le Monde, October 5. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy, Mitashree. 2020. Significance of Soft Skills in Career Development. In Career Development and Job Satisfaction. London: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam, Karen. 2004. Antecedents and consequences of employability orientation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 13: 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heijde, C. M., and B. I. J. M. Van Der Heijden. 2004. Indic@tor: A Cross-Cultural Study on the Measurement and Enhancement of Employability among ICT-Professionals WOrking in Small and Medium-Sized Companies. Deliverable 2.1 Report on Main Pilot Study. Available online: https://alba.acg.edu/faculty-research/about-applied-research-and-innovation/research-projects/employability/cross-cultural-study-measurement-enhancement-employability/ (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Weinberger, Catherine J. 2014. The Increasing Complementarity between Cognitive and Social Skills. The Review of Economics and Statistics 96: 849–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2014. Measuring Skills for Employment and Productivity: What Does It Mean to Be a Well-Educated Worker in the Modern Economy? Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/Feature%20Story/Education/STEP%20Snapshot%202014_Revised_June%2020%202014%20(final).pdf (accessed on 10 June 2022).

| University | Hassan I University Settat | 23.8% |

| Hassan II University Casablanca | 45.4% | |

| Mohamed V Agdal University | 30.8% | |

| Gender | Men | 51% |

| Female | 49% | |

| Family status | 1. Married | 21.4% |

| 2. Single | 78.6% |

| Open access establishment | Faculty of Sciences (FS). | 23.9% |

| Faculty of Legal, Economic and Social Sciences (FSJES). | 31.5% | |

| Faculty of Humanities (FLSH). | 11% | |

| Polydisciplinary Faculty of Khouribga (FPK) | 2.8% | |

| Regulated access establishment | National Superior School of Electricity and Mechanics (ENSEM). | 2% |

| Higher School of Technology (EST) | 9% | |

| Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy (FMP). | 2.3% | |

| Faculty of Dental Medicine (FMD). | 1.8% | |

| Mohamadia School of Engineering (EMI). | 3.3% | |

| Faculty of Science and Technology (FST). | 8.6% | |

| National School of Commerce and Management (ENCG). | 3.8% |

| Degree | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Bac + 2 | University Technological Diploma (DUT), Brevet Technicien Supérieur (BTS). | 9 |

| Bac +3 | Fundamental License (LF) | 48.3 |

| Professional License (LP) | 4.8 | |

| Bac + 4 | Master’s degree FST | 3.8 |

| Bac + 5 | National School of Commerce and Management (ENCG). | 3 |

| Engineer | 4.8 | |

| Research Master (MR) | 10.7 | |

| Specialized Master (MS) | 9.9 | |

| Bac + 6 | Diploma of Advanced Studies (DESA). | 0.8 |

| Bac + 8 | Doctorate | 1 |

| Doctorate in Medicine | 4.1 |

| Variables | Modalities | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 827 | 51% |

| Female | 794 | 49% | |

| Grand total | 1621 | 100% | |

| Family situation | Single | 1263 | 78% |

| Other situations | 358 | 22% | |

| Grand Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| Age in years | Under 26 years old | 611 | 38% |

| Between 26 and 29 years old | 763 | 47% | |

| 30 years and older | 247 | 15% | |

| Grand total | 1621 | 100% |

| Variables | Modalities | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Father’s occupation | Supervisor and manager | 341 | 21% |

| Employee or government employee | 660 | 41% | |

| Shopkeeper, farmer, craftsman, worker and laborer | 427 | 26% | |

| Unemployed and Inactive | 193 | 12% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| Mother’s occupation | Employed | 329 | 20% |

| Unemployed or Inactive | 1292 | 80% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| Father’s education level | None or Primary | 529 | 33% |

| Middle or High School | 571 | 35% | |

| Higher education | 521 | 32% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| Mother’s education level | None or Primary | 929 | 57% |

| Middle or High School | 429 | 26% | |

| Higher education | 263 | 16% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| Number of working siblings | 0 persons | 454 | 28% |

| Between 1 and 2 people | 773 | 48% | |

| 3 persons and more | 394 | 24% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% |

| Variables | Modalities | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did you repeat a year in high school? | Yes | 104 | 6% |

| No | 1517 | 94% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| What series of the baccalaureate | Scientific | 1133 | 70% |

| Economics and management | 136 | 8% | |

| Letter | 334 | 21% | |

| (empty) | 18 | 1% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| Did you repeat a year in high school | Yes | 216 | 13% |

| No | 1405 | 87% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| School | FS | 387 | 24% |

| FSJES | 511 | 32% | |

| FLSH | 178 | 11% | |

| Other | 545 | 34% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| What was the type of diploma | DEUG | 146 | 9% |

| Licence | 861 | 53% | |

| Master | 407 | 25% | |

| Master FST, ENCG and Engineer | 125 | 8% | |

| Doctorate Medicine and National Doctorate | 82 | 5% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% |

| Variables | Modalities | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| French language proficiency | Excellent | 470 | 29% |

| High | 843 | 52% | |

| Average | 306 | 19% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| Practical knowledge | Low | 1340 | 83% |

| Good | 281 | 17% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| Knowledge in computer science | Poor | 1338 | 83% |

| good | 283 | 17% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| Communication skills | Poor | 1251 | 77% |

| Good | 370 | 23% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| Communication skills in English | Poor to average | 1327 | 82% |

| More than average | 294 | 18% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% | |

| Have you done any internships while working on this degree | Yes | 979 | 60% |

| No | 642 | 40% | |

| Total | 1621 | 100% |

| Variable | Modality | Transitions to Employment | Permanent Studies | Sustained Employment | Dominant Unemployment | Inactivity | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Establishment | FS | 10.59% | 57.36% | 25.84% | 4.13% | 2.07% | 100.00% |

| FSJES | 15.85% | 30.33% | 38.94% | 13.11% | 1.76% | 100.00% | |

| FLSH | 11.24% | 15.73% | 41.01% | 25.84% | 6.18% | 100.00% | |

| Other | 18.35% | 36.70% | 40.37% | 3.12% | 1.47% | 100.00% | |

| Total | 14.93% | 37.32% | 36.52% | 9.01% | 2.22% | 100.00% | |

| Type of access institution | Open access | 13.20% | 37.64% | 34.57% | 11.99% | 2.60% | 100.00% |

| Regulated access | 18.35% | 36.70% | 40.37% | 3.12% | 1.47% | 100.00% | |

| Total | 14.93% | 37.32% | 36.52% | 9.01% | 2.22% | 100.00% | |

| Study level | DEUG | 23.97% | 61.64% | 10.96% | 0.68% | 2.74% | 100.00% |

| Licence | 10.69% | 47.85% | 25.90% | 13.01% | 2.56% | 100.00% | |

| Master | 17.20% | 23.34% | 49.88% | 7.62% | 1.97% | 100.00% | |

| Master FST, ENCG and Engineer | 8.00% | 1.60% | 88.80% | 0.80% | 0.80% | 100.00% | |

| Doctorate Medicine and National Doctorate | 42.68% | 7.32% | 47.56% | 1.22% | 1.22% | 100.00% | |

| Total | 14.93% | 37.32% | 36.52% | 9.01% | 2.22% | 100.00% | |

| Series of baccalaureate | Scientific | 14.92% | 41.31% | 37.78% | 4.15% | 1.85% | 100.00% |

| Economy and management | 17.65% | 34.56% | 44.12% | 3.68% | 0.00% | 100.00% | |

| Letter | 14.37% | 23.95% | 29.94% | 27.54% | 4.19% | 100.00% | |

| (empty) | 5.56% | 55.56% | 22.22% | 11.11% | 5.56% | 100.00% | |

| Total | 14.93% | 37.32% | 36.52% | 9.01% | 2.22% | 100.00% | |

| Gender | Male | 13.18% | 36.64% | 42.56% | 6.17% | 1.45% | 100.00% |

| Female | 16.75% | 38.04% | 30.23% | 11.96 | 3.02% | 100.00% | |

| Total | 14.93% | 37.32% | 36.52% | 9.01% | 2.22% | 100.00% |

| Variables | Modalities | C5: Inactivity | C1: Transition to Employment | C2: Education Permanent | C3: Sustainable Employment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Father’s occupation | Supervisor and manager | Réf | |||

| Employee or government employee | −1.355 ** | −0.569 | −0.292 | −0.506 | |

| (0.659) | (0.384) | (0.361) | (0.361) | ||

| Shopkeeper, farmer, craftsman, worker and laborer | −0.610 | 0.435 | 0.422 | 0.494 | |

| (0.722) | (0.436) | (0.412) | (0.410) | ||

| Unemployed and Inactive | 0.849 | −0.551 | 0.0570 | 0.279 | |

| (0.515) | (0.515) | (0.456) | (0.448) | ||

| Mother’s occupation | Employed | Réf | |||

| Unemployed or Inactive | −0.217 | −0.371 | −0.437 | −0.508 | |

| (0.839) | (0.466) | (0.435) | (0.437) | ||

| Father’s level of education | None or Primary | Réf | |||

| Secondary school or High school | 0.472 | 0.876 *** | 0.795 *** | 0.398 | |

| (0.524) | (0.305) | (0.277) | (0.275) | ||

| Higher education | −0.0294 | 0.666 | 0.950 ** | 0.684 * | |

| (0.791) | (0.429) | (0.387) | (0.386) | ||

| Mother’s level of education | None or Primary | Réf | |||

| Middle or High School | −0.632 | −0.153 | 0.0586 | −0.0107 | |

| (0.671) | (0.336) | (0.303) | (0.308) | ||

| Higher education | 1.650 * | 1.055 | 0.575 | 0.664 | |

| (0.979) | (0.645) | (0.611) | (0.614) | ||

| Gender | Male | Réf | |||

| Female | −0.406 | −0.728 *** | −1.025 *** | −1.376 *** | |

| (0.442) | (0.243) | (0.224) | (0.222) | ||

| Working siblings | 0 persons | Réf | |||

| Between 1 and 2 persons | −0.182 | 0.0105 | 0.133 | 0.331 | |

| (0.463) | (0.277) | (0.251) | (0.254) | ||

| 3 persons and more | −0.273 | 0.334 | 0.163 | 0.401 | |

| (0.567) | (0.316) | (0.293) | (0.290) | ||

| Family situation | Single | Réf | |||

| Other situation | 1.268 *** | 0.106 | −0.665 ** | 0.585 ** | |

| (0.456) | (0.286) | (0.281) | (0.255) | ||

| Have you repeated a grade in middle school | Yes | Réf | |||

| No | 0.470 | 0.963 ** | 0.564 * | 0.823 ** | |

| (0.652) | (0.407) | (0.336) | (0.323) | ||

| Have you repeated a year in high school | Yes | Réf | |||

| No | −0.0576 | 0.194 | 0.388 | 0.400 | |

| (0.526) | (0.293) | (0.269) | (0.260) | ||

| Training institution | Open access | Réf | |||

| Regulated access | 0.954 | 0.664 * | 0.0453 | 0.439 | |

| (0.625) | (0.344) | (0.327) | (0.324) | ||

| Internships while preparing for this degree | Yes | Réf | |||

| No | 0.810 | −0.699 ** | −0.928 *** | −0.811 *** | |

| (0.527) | (0.271) | (0.246) | (0.245) | ||

| Knowledge of French | Excellent | Réf | |||

| High | 0.0380 | −0.505 | −0.195 | −0.526 * | |

| (0.590) | (0.316) | (0.297) | (0.291) | ||

| Average | 0.399 | −0.830 ** | −0.969 *** | −1.505 *** | |

| (0.662) | (0.360) | (0.336) | (0.329) | ||

| Age in years | Under 26 years | Réf | |||

| [26–29] | −0.942 ** | −0.747 ** | −1.681 *** | −0.239 | |

| (0.467) | (0.295) | (0.269) | (0.278) | ||

| 30 years and older | −1.976 ** | −0.369 | −1.883 *** | 0.127 | |

| (0.800) | (0.408) | (0.392) | (0.372) | ||

| Practical knowledge | Above average | Réf | |||

| Low to medium | −0.898 | −0.475 | −0.250 | −0.660 ** | |

| (0.637) | (0.301) | (0.264) | (0.265) | ||

| Computer skills | Above average | Réf | |||

| Low to moderate | −1.215 * | 0.133 | −0.0621 | 0.0114 | |

| (0.738) | (0.303) | (0.276) | (0.270) | ||

| Communication skills | Above average | Réf | |||

| Low to average | −0.653 | −0.603 ** | −0.379 | −0.193 | |

| (0.540) | (0.282) | (0.248) | (0.244) | ||

| English language skills | Low to moderate | Réf | |||

| Above average | 0.772 | 0.578** | 0.295 | 0.461 * | |

| (0.479) | (0.293) | (0.269) | (0.265) | ||

| Constant | −1.087 | 1.105 | 3.067 *** | 2.019 ** | |

| (1.509) | (0.890) | (0.811) | (0.806) | ||

| Observations | 1621 | 1621 | 1621 | 1621 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ibourk, A.; El Aynaoui, K. Career Trajectories of Higher Education Graduates: Impact of Soft Skills. Economies 2023, 11, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11070198

Ibourk A, El Aynaoui K. Career Trajectories of Higher Education Graduates: Impact of Soft Skills. Economies. 2023; 11(7):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11070198

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbourk, Aomar, and Karim El Aynaoui. 2023. "Career Trajectories of Higher Education Graduates: Impact of Soft Skills" Economies 11, no. 7: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11070198

APA StyleIbourk, A., & El Aynaoui, K. (2023). Career Trajectories of Higher Education Graduates: Impact of Soft Skills. Economies, 11(7), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11070198