Abstract

Sharing economy online labor platforms play a critical role in bringing together freelancers and potential employers. This research is one of the few studies to address how freelancers’ characteristics impact the likelihood of being hired by employers using the theory of person–environment fit as a broad framework. Using Freelancer data, this research investigates if country of residence (of a freelancer and the employer), amount earned, and time since registered on the platform, are associated with the employment decision. The results indicate that country of residence does matter. Freelancers who tend to be from the same country as the employers are more likely to be hired. Likewise, high-income freelancers are less likely to be hired. Further, being longer on the platform influences the association between income level and likelihood of being hired. Greater efforts should be made to eliminate the asymmetric information between freelancers and employers and to provide more opportunities for both parties. The operators of online labor platforms should be encouraged to display information about freelancers that relates to country of origin, along with reviews, ratings, and rates earned in the same skill category, which would have strategic implications for freelance entrepreneurs on how to leverage themselves on a shared-economy-based online labor platform.

1. Introduction

In the past decade, the rapid increase in self-employment has substantially changed the nature of global employment and has redefined the appearance of work (Alvarez De La Vega et al. 2021; Hong and Pavlou 2017; Lehdonvirta et al. 2019; Munoz et al. 2022; Poon 2019; Sutherland et al. 2020). Simultaneously, online labor platforms (OLPs) have recently experienced accelerated increases in their activities (Graham et al. 2017; Kokkodis and Ipeirotis 2016; Melián-González and Bulchand-Gidumal 2018; Pongratz 2018; Wagner et al. 2021; Zhou et al. 2022). These platforms enable transactions and task performance to be geographically dispersed. They also offer labor entry opportunities to a reservoir of jobs, resulting an increase in freelancers (Borchert et al. 2018; Lehdonvirta 2018; Mai 2021). OLPs alleviate some of the historical challenges of the traditional labor environment posed by location, cost, skill unavailability, lack of diversity, and constrained movement of workers. By surmounting some of these challenges, OLPs reduce the asymmetry that has arisen because of disparities and inequalities in the marketplace. The overall effect of OLP growth is positive, with upgraded economic conditions, alleviation of poverty, and quality of life improvements (Borchert et al. 2018; Cockayne 2016; Popiel 2017).

One distinct element of OLPs is that task execution is rendered completely online (Durlauf 2019; Horton 2010, 2017; Umair 2017), which facilitates remote task performance and a wide array of prospective employers (clients) and freelancers. The OLP environment is commonly characterized by a surplus of labor availability and jobs that are simple to execute and do not require advanced or specialized skills. These features make OLPs attractive to self-employed or independent workers, the so-called freelancers (Borchert et al. 2018; Aguinis and Lawal 2013; Baitenizov et al. 2019; Bögenhold and Klinglmair 2016; Bridge 2016; de Jager et al. 2016; Elstad 2015; Johal and Anastasi 2015; McKeown 2016; Syrett 2016).

This research is particularly interested in what dictates the success of the freelancer from a human capital perspective (Hong and Pavlou 2017; Lehdonvirta et al. 2019; Ayoobzadeh 2022; Chauradia and Galande 2015; Galperin and Greppi 2017; Huđek et al. 2021; Kathuria et al. 2021; Lo Presti et al. 2018; Nawaz et al. 2020; Scaraboto and Figueiredo 2022; Van den Born and Witteloostuijn 2013; Žunac et al. 2021). Understanding how a freelancer secures a contract has implications for both platform design and the hiring of freelancers, as well as for the composition of contemporary work forces (Alvarez De La Vega et al. 2021; Huđek et al. 2021; Osterman 2022; Rodgers et al. 2014). As mentioned, current studies have focused on project (job) and platform characteristics rather than those of the freelancer (e.g., Hong and Pavlou 2017; Barlage et al. 2019; Claussen et al. 2018). This study attempts to extend beyond merely identifying the drivers of project success to developing a theoretically grounded understanding of freelance hiring decisions (Kathuria et al. 2021; Lo Presti et al. 2018; van der Zwan et al. 2020).

In other words, while current studies have provided important groundwork on factors that determine the success of platform-based freelance projects (Sultana et al. 2019; Zadik et al. 2019), they have stopped short of conceptualizing freelancer traits, for example, (Wagner et al. 2021; Elstad 2015; Gupta et al. 2020a, 2020b; Norbäck and Styhre 2019). Furthermore, most studies have emphasized the employer and not the freelancer (Mai 2021; Galperin and Greppi 2017; Žunac et al. 2021; Zadik et al. 2019; Lustig et al. 2020; Nemkova et al. 2019; George and Ng 1997). This study addresses this gap by exploring the factors that lead to the successful hiring of a freelancer. Additionally, this study looks at this landscape via the theory of person–environment fit (P–E fit) (Umair 2017; de Jager et al. 2016; Claus et al. 2011; Schulze et al. 2012; Toth et al. 2020), which suggests that the better the fit of a person to an environment, the better the outcome for them in that environment (Caplan 1987; Caplan and Harrison 1993; Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Peters et al. 2020; Yu 2016).

This study explores relevant factors related to a freelancer obtaining a contract to perform a job. The factors such as the country of residence, the amount earned, and the length of time each freelancer is registered on the platform, along with the employment decision that is dependent on these factors, are all selected for the following reasons: (1) The country of residence of both the freelancer and employer impact the hiring decision, i.e., freelancers who are from the same country as the employers are more likely to be hired. (2) The income level of the freelancer plays a role in whether he or she is hired, i.e., high-income freelancers are less likely to be hired. (3) The associations between country match and likelihood of being hired, and income and probability of being hired, are likely to be impacted by the time the freelancer spent on the platform. These characteristics are considered to assess the fit between a freelancer and the environment (the employee and the platform combined) through the lens of the theory of P–E fit. Despite a variety of other factors that have previously been identified and researched (Melián-González and Bulchand-Gidumal 2018; Wagner et al. 2021; Popiel 2017; Galperin and Greppi 2017; Huđek et al. 2021; Nawaz et al. 2020; Sultana et al. 2019; Zadik et al. 2019; Gupta et al. 2020a, 2020b; Ke and Zhu 2021; Shevchuk et al. 2015), the country of residence, the amount earned, and the time spent on the platform by the freelancer as a subset that offers insights on the freelancer and their ability to obtain the contract or employment were selected grounded in the theory of P–E fit. Specifically, this theory is leveraged to argue that the factors mentioned function as predictors of the hiring decision (de Jager et al. 2016; Peters et al. 2020).

This research does not fail to note other factors or measures of hiring decisions. It merely highlights that the selected factors, i.e., the country of residence (of both employer and freelancer), the amount earned, and the time that a freelancer is registered on the platform can contribute to the prediction of successful hiring, in the context of a labor-based platform.

Because this research is data driven and an emerging area of research, this study provides a framework for integrating multiple perspectives on hiring decisions instead of being deeply grounded in this theory. To the best of our knowledge, this study is one of a relatively sparse number of studies in this emerging area to explore empirically and in an integrated way the context of multiple factors and theories rather than with an ad hoc approach.

The overarching research question is: What factors contribute to the hiring of a freelancer via an online labor platform?

The study was conducted using the Freelancer.com platform website because it is one of the oldest and more global labor-based platforms. According to the website, it is the “world’s largest freelancing and crowdsourcing marketplace”, and “has connected over 55,163,568 employers and freelancers globally from over 247 countries, regions and territories” (accessed website on 16 September 2021).

This research makes several noteworthy contributions. First, the results show that freelancer traits make a difference. Second, the study adds to the growing empirical literature on the human capital aspects and the understanding of nuances within the freelancing process. Third, this study contributes moderately to using the theory of P–E fit to explain various factors and relationships in freelancing that impact freelancers’ work environments. Prior literature has focused on project factors and overall freelancing quality of life (e.g., satisfaction with freelancing), drawing from the existing literature on entrepreneurship, self-employment, crowdsourcing, and human resources. This research has directed attention to the freelancers themselves. Fourth, this research adds to the literature on the nature and dimensions of freelancing, a demonstrable shift in the direction of research on freelancing in a labor-based platform. Fifth, the data-driven approach enhances the rigor of this study. Openly available data from Freelancer.com were crawled and prepared, thereby making the reproducibility of the research a priority.

This paper is organized as follows: Following the Introduction, Section 2 discusses the freelancing phenomenon, as well as prior research; Section 3 describes the conceptual framework by discussing the theory of P–E fit and its relationship to freelancing; Section 4 describes the research methods; Section 5 discusses the results and provides the analysis; the implications for research and practice are enunciated in Section 6; while Section 7 provides conclusions and the scope and limitations of the research.

2. Research Background—Freelancing

There has been a relative surge in studies of freelancing (Alvarez De La Vega et al. 2021; Lehdonvirta et al. 2019; Mai 2021; Huđek et al. 2021; Kathuria et al. 2021; Žunac et al. 2021; van der Zwan et al. 2020; Sultana et al. 2019; Zadik et al. 2019; Gupta et al. 2020a; Ke and Zhu 2021), but there is still a lack of research on the subject (Poon 2019; Wagner et al. 2021; Baitenizov et al. 2019; McKeown 2016; Zadik et al. 2019; Barley et al. 2017; Fenwick 2006; Kitching and Smallbone 2012). Cohesive underlying theories to explain the dimensions and facets of freelancing are in the process of being applied or developed (Poon 2019; Wagner et al. 2021; Aguinis and Lawal 2013; Bögenhold and Klinglmair 2016; McKeown 2016; Syrett 2016). Existing studies have only focused on macro-level factors, linking freelancing to shifts in the labor force, global mobility, and access to knowledge and skills (Syrett 2016; Abreu et al. 2019; Annink 2017; Meager 2016; McKeown and Leighton 2016; Holtz et al. 2022; Nikolova 2019; Obschonka et al. 2014). These studies have been limited to a few narrow domains, including book publishing (George and Ng 1997), information technology and software development (Sultana et al. 2019; Gupta et al. 2020a, 2020b), fintech freelancers (Damian and Manea 2019), freelance jazz musicians (Elstad 2015), freelance journalists (Norbäck and Styhre 2019), and internet freelancers (Shevchuk et al. 2015).

Only a few studies have focused on the characteristics of freelancers and studied how these characteristics were associated with hiring success. Further, from a methodological perspective, most studies have used cases (Popiel 2017; Gupta et al. 2020a, 2020b; Gomez-Herrera et al. 2017), content analysis (Pongratz 2018), field experiments (Mai 2021), interviews (Lehdonvirta et al. 2019; Sutherland et al. 2020; Lehdonvirta 2018; Mai 2021; Lustig et al. 2020; Nemkova et al. 2019), or surveys (Huđek et al. 2021; Van den Born and Witteloostuijn 2013; Gupta et al. 2020b; Shevchuk et al. 2015), which has limited the scientific details that allow for generalization or the reproduction of results. While a few studies that have utilized different types of data have emerged (Lehdonvirta et al. 2019; Graham et al. 2017; Kokkodis and Ipeirotis 2016; Melián-González and Bulchand-Gidumal 2018; Borchert et al. 2018; Galperin and Greppi 2017; Hannák et al. 2017; Horton et al. 2018), until now, a general paucity of data has restricted research. Overall, the existing research is highly fragmented and eclectic and has yet to constitute a robust corpus of knowledge and theories built around the phenomenon of freelancing (Poon 2019; Mai 2021; Aguinis and Lawal 2013; Syrett 2016). This research attempts to fill some of the gaps. While there are various characterizations of freelancers, a contemporary report on freelancers has depicted them as “individuals who have engaged in supplemental, temporary, or project- or contract-based work” (Zadik et al. 2019, p. 39). Following (Zadik et al. 2019), this research accepts a more general definition of freelancing based on the work of (Kitching and Smallbone 2012, p. 77), i.e., these workers are “self-employed employees working on their own account, with a client base of organizational and personal clients, with contracts of any duration, working freelance in either primary or secondary work roles”. This definition considers that freelancers are not employees of a company or entity, but rather they are their own bosses and develop agreements with ”clients” or ”employers’ to execute specific tasks. Freelancers are awarded contracts on an ad hoc basis for one or more projects; further, there is no limitation on the number of jobs or clients they might have at a given time (Sultana et al. 2019; Zadik et al. 2019). Among the OLPs that have established themselves as leading enablers of freelancing are Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT), Freelancer.com, and Upwork (formerly Elance-oDesk) (Sultana et al. 2019; Zadik et al. 2019).

The rapid rise in freelancing and freelancers can be attributed to two factors: Advances in technology that have resulted in the development of labor and service-based online platforms that enable online contracts to be executed (Katz and Krueger 2017) and the COVID-19 pandemic that obviously has led to exponential growth in virtual work and freelancing (Dunn et al. 2020; Sawyer et al. 2020). In fact, the freelancing segment of the market is expected to increase from USD 14 billion in 2014 to USD 335 billion by 2025 (Yaraghi and Ravi 2017). Furthermore, there is an estimated 59 million Americans working as freelancers, and this number is projected to increase to over 90.1 million by 2028 (https://financesonline.com/number-of-freelancers-in-the-US/) (accessed 1 July 2022). Additionally, freelancers contributed to approximately USD 1.2 trillion in the U.S. economy during the pandemic alone and approximately 5% of the country’s GDP (https://99firms.com/blog/freelance-statistics/) (accessed 1 July 2022). Freelancer.com estimates it has a global workforce of 42 million freelancers (https://www.freelancer.com/enterprise) (accessed 1 July 2022). Indeed, the U.S. Freelancers Union forecasts that, in the next decade, most U.S. employees will be freelancing (https://www.freelancersunion.org) (accessed 1 July 2022). For example, information technology (IT) freelancing has been increasing in popularity, mainly because of the growth and reach of the Internet and an increase in online marketplaces (Hong and Pavlou 2017; Sultana et al. 2019; Gupta et al. 2020a, 2020b). This movement is also noticeable in various other regions of the globe, particularly in the European Union where approximately 30.6 million people, or an estimated 14% of the total European labor force, were classified as self-employed during 2016 (Eurostat 2017). Meanwhile, freelancing is growing in Asia and other parts of the world (https://financesonline.com/freelance-statistics/) (accessed 1 July 2022).

There is also an emerging interest in the freelancing profession among academicians (Hong and Pavlou 2017; Poon 2019; Lo Presti et al. 2018; Ke and Zhu 2021), although this information is somewhat overlooked in the research literature (Poon 2019; Wagner et al. 2021; Baitenizov et al. 2019; McKeown 2016; Barlage et al. 2019; Zadik et al. 2019; Fenwick 2006; Kitching and Smallbone 2012).

Given the popularity of the freelancing profession in different industries, attention has also been paid in recent research to an eclectic variety of issues in freelancing: skills (Sutherland et al. 2020; Kathuria et al. 2021), working conditions (Elstad 2015), relationships with clients using a variety of methodologies (Norbäck and Styhre 2019), platforms and design questions (Alvarez De La Vega et al. 2021; Galperin and Greppi 2017), freelancer survival methods (Lehdonvirta et al. 2019), human capital (Huđek et al. 2021; Shevchuk et al. 2015), contract structure, and profiles of clients and freelancers (Popiel 2017), to name a few. The evolution of the literature on freelance platforms suggests an amalgam of the current literature and directions for future research to collectively advance the understanding of the freelancing phenomenon (Wagner et al. 2021). Most of these studies have focused on the project and the platform rather than on the freelancers themselves. At the project level, Zadik et al. (2019) investigated the impetus of managers in recruiting freelancers and the environmental conditions that determined the selection of freelancers for various organizational jobs (Zadik et al. 2019). At the platform level, for instance, some scholars have put an emphasis on the ”bid amount” in addition to other factors, in response to auction mechanisms widely applied by online labor platforms. Specifically, Scholz and Haas (2011) investigated the transaction cost theory to explain the decision-making process beyond ”the bid amount” (Scholz and Haas 2011). Some scholars have also explored stereotypes in culture and geography as influential factors in final employment contracts. Specifically, Burtch et al. (2012) noted the presence of cultural biases in interpersonal economic exchange (Burtch et al. 2012). Their study identified and quantified the impacts of cultural differences in transactions between individuals on online labor platforms. Hong and Pavlou (2017) provided a novel perspective on the roles that platforms play in interactions between employers as consumers or buyers, and freelancers as service providers in virtual markets (Hong and Pavlou 2017).

Therefore, there is a need to focus on the freelancers themselves and to examine how their characteristics can attract hiring. Accordingly, this study has both strong research and practical implications and provides suggestions to platforms that can support a better working experience (Alvarez De La Vega et al. 2021). That is, the eclectic and disparate streams of research leave a gaping hole in the understanding of how freelancer contracts are awarded based on the characteristics of freelancers. Additionally, very few studies have used empirical data (e.g., Lehdonvirta et al. 2019; Kokkodis and Ipeirotis 2016; Borchert et al. 2018; Mai 2021; Umair 2017; Galperin and Greppi 2017; Toth et al. 2020; Shevchuk et al. 2015; Horton and Chilton 2010). The limited data used provide limited generalizability and insight into the phenomenon of freelancing and warrants additional research to fill the gap, particularly, in the understanding of what drives freelancer success in a competitive online marketplace. This study hopes to fill some of this gap by shedding light on this association.

3. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

In an endeavor to fill the gaps identified in the current literature search, this research borrows from and applies the understanding of the existing literature on P–E Fit (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Dawis 1992; Dawis et al. 1964; Dawis and Lofquist 1984; Kennedy 2005; Kristof 1996; Schneider 1987) to obtain insights on the freelancing phenomenon. The P–E fit framework presents multiple types of fit that are utilized to examine the dynamics that involve a freelancer and an employer and elicit the key variables that influence the hiring process (de Jager et al. 2016; Caplan and Harrison 1993; Yu 2016; Kristof 1996).

The P–E fit has been applied widely to understand individual attitudes and behaviors in organizations (Caplan and Harrison 1993; Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Kristof 1996). The P–E fit generally refers to the “congruence, match, or similarity between the person and the environment” (Kristof 1996; Edwards et al. 1998). Most theoretical and empirical work in the P–E fit has been based on the widely held assumption that the P–E fit leads to positive outcomes such as a good fit between a person’s skills and the employer’s task requirements (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Chatman 1989; Edwards and Shipp 2007; O’Reilly et al. 1991). The strength of this framework lies in its ability to explain human behavior as a product of interactions between an individual and the environment (Yu 2016; Kristof 1996; Lewin 1935), and its adaptability to numerous situations (Jansen and Kristof-Brown 2005).

The framework theorizes about the extent to which a worker fits (or does not fit) into their environment: A worker (or employee) with a good fit is more likely to have a lasting and successful career while a worker who is a misfit is likely to change jobs, quit, get fired, and/or go back to school to begin the process of a career change. The quality of a worker’s fit with their work environment is contingent on the relative extent to which the worker’s traits, skills, aspirations, necessities, and values are consistent with and match the job requirements, the work ethic, inherent and acquired rewards, and the beliefs of the employer (client) (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Kennedy 2005; Kristof 1996; Schneider 1987; Holland 1985; Talbot and Billsberry 2010). However, the ”fit” is not static. It is in a dynamic state of flux, and both the worker (freelancer) and employer (client) will strive to reach an agreement. Ideally, both parties strive for a good fit to attain a common goal (de Jager et al. 2016; Schneider 1987; Holland 1985; Talbot and Billsberry 2010; Schneider et al. 1997). The prevailing understanding of the theory has delineated several types of P–E fit (Caplan and Harrison 1993; Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Dawis 1992; Kristof 1996; French et al. 1982; Muchinsky and Monahan 1987; Ostroff and Schulte 2007).

The P–E fit describes a complementary fitting relationship, where a person (e.g., freelancer) and the environment (e.g., the online platform, employer, etc.) each provide what the other needs (Muchinsky and Monahan 1987). Freelancing has the potential to address the challenges of work–life balance such that it is consistent with an individual’s aspirations and values; thus, freelancing can enable an optimal work environment (Umair 2017; de Jager et al. 2016). Naturally, the P–E fit framework is a legitimate approach to studying freelancing and freelancer interactions with the OLPs in the current research. In recent years, the P–E framework has evolved and expanded to include a variety of P–E fit measures, thereby making it a flexible framework to study the many different aspects and dimensions of the person–work environment (de Jager et al. 2016; Peters et al. 2020; Yu 2016; Verquer et al. 2003). However, while the framework of the theory has become more expansive and flexible, most of the research applying P–E fit has adopted a single measure (de Jager et al. 2016; Toth et al. 2020; Peters et al. 2020; Yu 2016). Recently, researchers have explored the use of multiple P–E fit measures to capture the complexity and multidimensional aspects of self-employment (Yu 2016; Kennedy 2005; Chuang et al. 2016; Edwards and Billsberry 2010; Sekiguchi 2004).

Consistent with these efforts, in this study, we use multiple P–E fit measures to explain the freelancer’s platform–employer interaction. However, it is noteworthy that, while prior research has suggested integrating multiple levels of P–E fit (Yu 2016; Kennedy 2005; Chuang et al. 2016; Edwards and Billsberry 2010; Sekiguchi 2004), very little research has actually been conducted quite this way.

Below, two key measures that are popular in the literature are discussed, namely the person–organization fit (P–O fit) and the person–job fit (P–J fit), with an emphasis on their relevance for this study. In terms of the P–O fit, Tom (1971) recommended that employees would be most successful in organizations that shared their personalities. Based on this, studies have focused on numerous characterizations of the P–O fit such as personality–climate congruence (e.g., Christiansen et al. 1997; Ryan and Schmit 1996), value congruence (Kristof 1996; Chatman 1989; O’Reilly et al. 1991; Verquer et al. 2003), and goal congruence (e.g., Vancouver and Schmitt 1991; Witt and Nye 1992). Whatever the type of congruence being analyzed, the underlying theme of the P–O fit is the fit between an individual and the organization (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005). This underlying theme of the P–O fit in the current research is utilized to help understand the relationship between a freelancer (individual) and the client/employer (organization), in terms of their mutual expectations and demands. Specifically, studies have discussed the fit in the context of needs versus supplies and culture congruence (Caplan 1987; Kristof 1996; Chatman 1989; O’Reilly et al. 1991; Cable and Judge 1996; Boon and Hartog 2011). The freelancer’s needs address the economic and psychological aspects (e.g., earning a competitive income, matching task with skill, etc.). On the one hand, freelancers supply their skills, personal traits, and experience. Employers, on the other hand, seek (need) particular skills, a certain number of workers, and minimum years of experience, and they compensate (supplies) freelancers with monetary benefits, stable wages, and the potential to develop a long-term relationship (de Jager et al. 2016). Insight into the specific needs and aspirations of freelancers can facilitate the understanding of employers (e.g., organizations) regarding what self-employment and freelancing mean and can influence them to take steps to make their relationships more harmonious (de Jager et al. 2016; Lustig et al. 2020; Nemkova et al. 2019; Peters et al. 2020). As mentioned earlier, one can also examine the cultural aspect, particularly as freelancing is a global phenomenon. Culture has been studied extensively in the literature on crowdfunding and online platforms (Ren et al. 2020). Based on previous research, culture congruence has been described as the convergence of values (e.g., ethics, etc.) between a worker and the employer (Hong and Pavlou 2017; Lehdonvirta 2018; Galperin and Greppi 2017; Kathuria et al. 2021; Edwards and Cable 2009; Meglino and Ravlin 1998; Rokeach 1973; Schwartz 1992). Here, culture congruence is applied to relate to the convergence of values between a freelancer (worker) and the client (employer). Conflict between the cultures that drives a freelancer towards a particular task/employer and vice versa may provide an answer to the perennial challenge of maintaining a viable long-term association between freelancers and employers (Hong and Pavlou 2017; Lehdonvirta 2018; Galperin and Greppi 2017; Kathuria et al. 2021; Hannák et al. 2017). The country of residence of a freelancer and the employer as an element that allows for convergence of values are used, thus contributing to the fit between the freelancer (person) and the employer (organization) (P–O fit).

The P–J (person–job) fit is the fit between an individual’s abilities and desires and the demands or attributes of a specific job (Edwards et al. 1998) and it is referred to as demands versus abilities (Kristof 1996). In this study, the P–J fit specifically addresses the relative fulfillment arising from a fit between the requirements (demands) of a particular job and the skills expected to perform the job, as well as the individual traits of the freelancer being considered (Umair 2017; Schulze et al. 2012; Toth et al. 2020). On a continuum of potential outcomes, the job requirements may either overpower the freelancer or not spark interest or excitement in the freelancer. Freelancers’ abilities are represented by their capabilities and skills in fulfilling the requirements of the job. Specifically, the income earned by the freelancer in the same skill category as the employer and the length of time the freelancer has been registered on the platform are used as variables that define the P–J fit. The rationale is that the skill level of the freelancer establishes their capability to match the job requirements. The experience and income level further denote their ability to perform the job efficiently. Therefore, taken together, all three attributes, i.e., the skill level, experience, and income level, facilitate a fit between a person and the job (P–J fit).

This study focuses on the online labor market and considers one of the largest platforms, i.e., Freelancer.com, for the dataset. With this rich dataset, this study explores factors that affect how employers decide which freelance workers to select when they use an online labor platform. The study analyzes the association between the potential employee’s status, such as matching the freelancer’s country with that of the employer (P–O fit, e.g., culture), the income earned by the freelancer in the same skill category as the employer, and the length of time that the self-employed freelancer has been registered on the platform (P–J fit, e.g., skill level, experience, and income level). The employer’s ultimate hiring decision is alos analyzed, while controlling for the utility-based cues discussed in the prior literature. That is, it is hypothesized that, in addition to such common factors as payment and review information, an employer’s decision to hire a freelancer also depends on whether the freelancer resides in the same country as the employer (P–O fit of culture) and what hourly wage they have earned in the past for the skill category under consideration (P–J fit). Additionally, the length of time the freelancer has been registered on the platform (P–J fit) is considered.

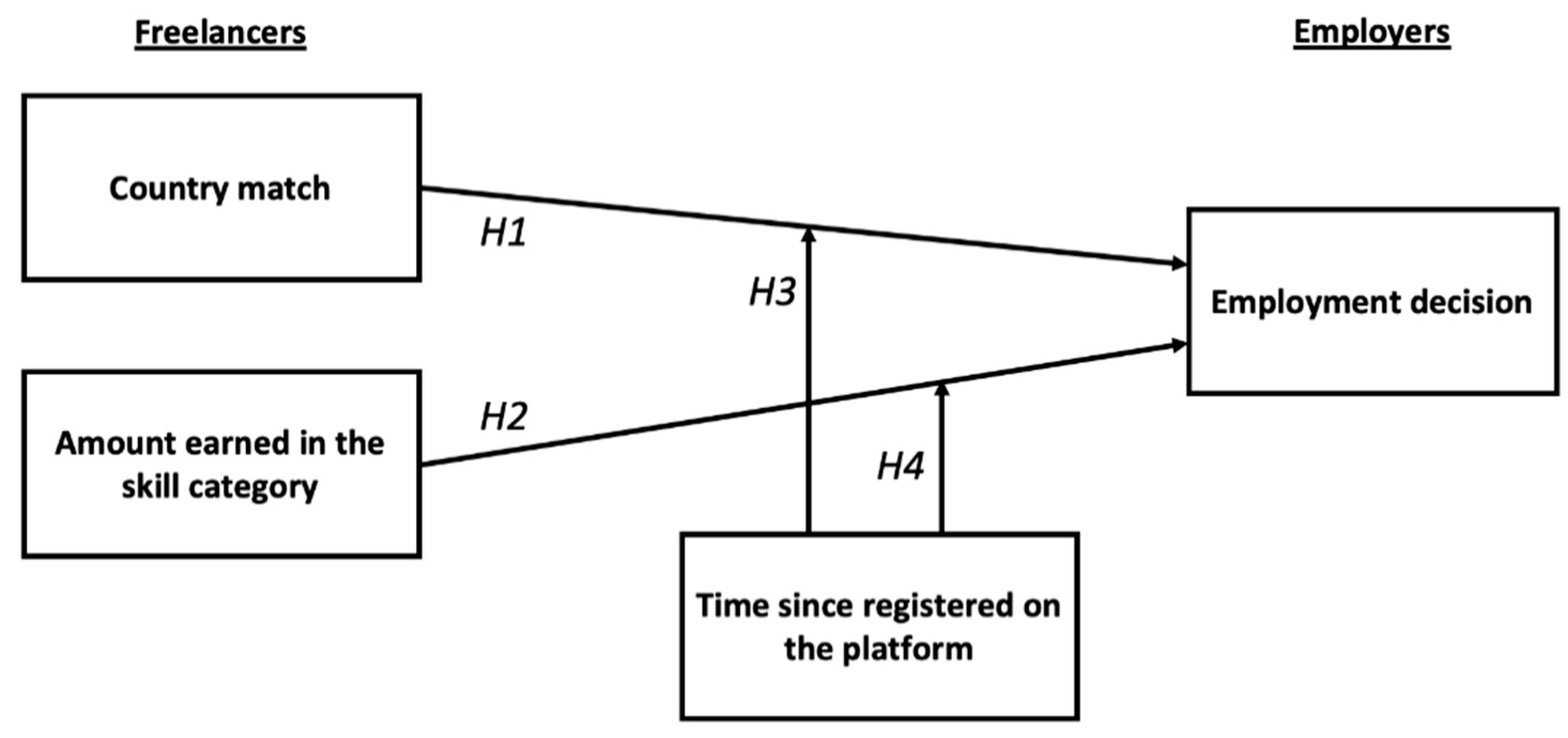

Effective communication almost always leads to greater efficiency and productivity in the workplace. Since online labor platform employers and prospective freelancers have less or no probability of experiencing face-to-face interactions, effective and open communication becomes critical. In employer–freelancer communications, there are advantages to speaking the same language and coming from similar backgrounds. Therefore, it is argued in hypothesis one (H1) that, for greater work efficiency, employers tend to hire freelancers who come from the same country as themselves. This is consistent with the P–O fit of culture. Employer intuition may be that a freelancer who overcharges for their labor may be less trustworthy or that a freelancer who relies too heavily on experience rather than utilizing contemporary knowledge and skills is less competent. Therefore, it is argued in hypothesis two (H2) that the income a freelancer has earned in the past has a negative association with the possibility of their being hired (P–J fit). It is further proposed that the newness of the freelancer to the platform moderates hypotheses one and two. Therefore, in hypothesis three (H3), if a freelancer is a long-time/experienced user of the platform and has a similar background to that of the employer, they may be more appealing to the employer (P–J fit). In hypothesis four (H4), if a freelancer is new to the platform and has made significant money, employers may think that this person has charged too much and is less trustworthy. Therefore, the likelihood of hiring them decreases. Figure 1 shows the overall research model.

Figure 1.

The research model.

To summarize, to investigate the factors influencing the decisions made by employers on whether to hire a freelancer through an online labor market platform, the following four hypotheses are developed:

H1 (Country match -> employment).

Freelancers who are from the same country as the employers are more likely to be hired.

H2 (Income -> employment).

High-income freelancers are less likely to be hired.

H3.

The positive association between country match and employment is stronger when the freelancers have been on the platform for longer duration.

H4.

The negative association between income and employment is stronger when freelancers are new to the platform.

4. Data and Method

The main source of data for the current study is an online labor platform website, i.e., Freelancer.com. This platform is one of the world’s largest marketplaces for fulfilling freelance opportunities. It is an Australia-based firm that provides the technology to connect “over thirty-four million employers and freelancers globally, from over two hundred countries, regions, and territories” (Freelancer.com). On this platform, there are 13 project categories, including websites, IT and software, mobile phones and computing, writing and content, design, media and architecture, data entry, and administration. Freelancer.com provides a representative sample of freelancers and prospective employers and provides different characteristics of freelancers. This allows one to study how the characteristics of freelancers affect hiring success in the context of a global marketplace, thus offering a rich research environment for gathering insights. Each observation in the dataset is the pairing of a bid by a freelancer in response to a project posted by an employer. Additionally, it is noted whether or not the freelancer was awarded the contract. More than thirty-five thousand records of employer–freelancer pairs related to more than 4500 posted projects were retrieved. After filtering, approximately ten thousand closed projects were chosen for the study. In the analyzed dataset, an average of 9.41 freelancers bid for each project, and one freelancer was selected for each project. The dataset drilled down to the individual (freelancer) level and can be drilled up to the project level, with each project having a set of freelancers bidding for it. The original dataset contained numerous variables, which were processed and normalized to create a new set for further analysis. To summarize, this research examined the associations between a freelancer’s characteristics and an employer’s decision to hire that freelancer. Three fixed-effects logit regression models were applied to examine the associations between the characteristics of freelancers and the hiring decisions made by employers.

Dependent variables, independent variables, and moderator and control variables were chosen to build the models.

Freelancer awarded or not is defined as the dependent variable to measure the decisions made by the employers. In terms of coding, 1 stands for the Freelancer hired by the employer, while 0 stands for the Freelancer was not hired by the employer.

As mentioned in the prior literature, many studies have proven that reputation could influence the decisions of employers. In the platforms, employers take advantage of unique measures generated by online platforms, for example, the overall rating of and number of reviews for a freelancer, to infer prospective employees’ capabilities. The impact of hourly payment and online reviews on hiring decisions were central to earlier studies; these are regarded as emotional triggers influencing employers to make decisions, and so hourly payment, overall rating, and number of reviews were included as control variables in the models.

Independent variables were chosen for H1 and H2: The country match variable measures whether or not the country of origin of the freelancer is the same as the employer (H1), and the amount earned in this skill category variable measures the freelancer’s income earned in the skill category of the bid (H2). The moderator variable, time since registered on Freelancer.com, concerns H3 and H4 and is examined. This variable measured the length of time the freelancer had been on the platform prior to the study.

Below, the variables are summarized.

Dependent variable The freelancer awarded or not variable is a binary variable.

Control variables (1) The hourly payment variable controls for the hourly payment required by the freelancer; (2) the overall rating variable is the overall rating of the freelancer; (3) the number of reviews variable is the total number of reviews received by the freelancer.

Independent Variables (1) Country match is a binary variable where 1 means the freelancer and employer are in the same country and 0 means they are in different countries and (2) the amount earned in this skill category variable measures the potential of the freelancer to earn income.

Moderator variable The time since registered on Freelancer.com variable is the number of months the freelancer had been on the platform until September 2018, when the data were collected.

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for all the variables. Table 1 shows the minimum, median, mean, and maximum values as well as the first quartile and the third quartile for all the variables. The variables were normalized to make sure that they follow normal distributions.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 2 shows the correlations among all continuous variables and it can be observed that the correlations among most of the variables are low.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix.

5. Results and Analysis

To test the hypotheses, this study used fixed-effects logit regression models at the project level. The results appear in Table 3, which shows the coefficient of each variable in each model. The first model focuses on the control variables limited to the freelancer—preferred hourly payment measured in U.S. dollars, overall rating, and the number of reviews. Among these variables, the coefficient for the rating of the freelancer is positive and at a significance level of 0.001. The other two variables are not as significant.

Table 3.

Findings of the fixed-effects logit models.

The second model considers the two independent variables, i.e., the amount earned by the freelancer and whether the countries match, along with the moderator variable, i.e., the freelancer’s experience and time since registered on the platform. The freelancer rating is a very significant predictor with a positive coefficient and a p-value at a significance level of 0.001, while other variables were added to the list. The number of reviews, at a significance level of 0.05, is significant and has a positive effect. The country match is a significant predictor, with a positive effect. Freelancers from the same country as the employer appear to be preferred. Therefore, H1 is supported. This is consistent with the P–O fit, wherein culture similarity matters. The amount earned, which is one of the freelancer indicators calculated by the platform, is expected to be a negative indicator. It is notable at a significance level of 0.05. Therefore, H2 is supported as well. This is consistent with the P–J fit. The third model includes two additional interaction effects: one interaction effect between the country match and the freelancer experience, and the other interaction effect between the amount earned and the freelancer experience. The interaction between the freelancer experience and the country match variable is not significant, indicating that H3 is not supported. The positive significant interaction between the amount earned and the freelancer experience shows that the negative association between amount earned in the same skill category and employment is stronger when the workers are new to freelancing compared to when they are experienced. Therefore, H4 is supported.

6. Implications for Research and Practice

Overall, this research identifies the characteristics of freelancers that influence employers’ hiring decisions. It contributes useful insight for multiple parties, including the freelancers and employers who use the online labor market platform, as well as policymakers and scholars, by providing a better understanding of the relationships and interactions between freelancers and employers. Thus, this study offers significant contributions to both research and practice.

First, it contributes to the freelancing literature that focuses on platforms and the employers in hiring freelancers. This study shifts the focus to individual freelancers and examines how their characteristics affect hiring success. Specifically, the results of this study enrich the stream of literature that focuses on individual freelancers. For example, some scholars have studied freelancers’ listed payments in relation to the agreements between employers and employees (Huđek et al. 2021; Lustig et al. 2020). Many studies have measured how wages influenced freelancers’ decisions to accept a task, as well as the freelancers’ price sensitivity (Popiel 2017; Gomez-Herrera et al. 2017). Horton and Chilton (2010) introduced a way to calculate the value of the basic pay (a primary variable in the labor market) that a freelancer would agree to for a given task (Horton and Chilton 2010). Then, Horton (2017) implemented a minimum wage experiment to discover whether or not wages of hired workers paid by employers in the platforms would rise substantially if a higher minimum wage was imposed (Horton 2017; Garin et al. 2020; Dellarocas 2003). This research studied characteristics of freelancers that were beyond just the payment factor and systematically tapped into the characteristics including cultural background, tenure, and payment. As a result, this research contributes to an understanding of how the sharing economy works in the context of entrepreneurship, that is, the entrepreneurial role freelancers/independent workers play in having control over their work and overall goals. Sultana et al. (2019) applyed the theory of planned behavior and utilized data from oDesk.com (now Upwork.com) (accessed on 1 July 2022) to identify the entrepreneurial behavior of IT freelancers and concluded that both IT self-efficacy and social capital obtained through social media interactions contributed to IT freelancers’ entrepreneurial behaviors (Sultana et al. 2019). In contrast, this paper focuses on the inherent characteristics of the freelancers and links how these characteristics, instead of the social capital of the freelancers, affect the success of their entrepreneurial behaviors.

Second, this paper contributes to the literature that applies the P–E fit model. Prior research has adopted this model in the traditional work environment where full-time employees work for an employer for a long period of time, rather than for different employers on a project-by-project basis. In the traditional work context, these studies have focused on workers’ traits, skills, aspirations, necessities, and values that are consistent with and match the job requirements, the work ethic, inherent and acquired rewards, and the beliefs of the employer (client) (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Kennedy 2005; Kristof 1996; Schneider 1987; Holland 1985; Talbot and Billsberry 2010). This research, in contrast, argues that the characteristics of freelancers can function as the cues to indicate the fit between freelancers and employers. For example, it is argued that a freelancer’s country of origin can indicate the culture he or she is from, and thus can represent the P–O fit (person–organization fit). In addition, a freelancer’s cumulative income and tenure on a platform indicate the P–J fit (person–job fit). Thus, the P–E fit model in freelancing research clarifies the contemporary view of freelancing and adds structure to this emerging field by providing a framework to facilitate future research. A comprehensive P–E fit framework with its multiple components can enable panel studies that shed light on why particular workers may opt to be freelancers and whether or not they are likely to continue as freelancers.

Third, this paper has strong implications for different players such as the employers, freelancers, and the platforms. Specifically, models were constructed to explore associations between the characteristics of the freelancers and the decisions made by the employers. The statistical analysis performed in this study identifies key factors and characteristics of freelancers that significantly influence employers’ hiring decisions, which helps to better understand the supply–demand relationship in the platform. To promote dynamic transactions between service providers and consumers, the management of platforms and policymakers should make greater efforts to eliminate the asymmetric information between freelancers and employers and to provide more opportunities for both parties to know more about each other in order to make effective decisions and to protect both parties’ interests. Considering the geographical impact on the platforms uncovered in earlier studies (Hong and Pavlou 2017; Lehdonvirta 2018; Galperin and Greppi 2017; Kathuria et al. 2021), the findings of this study suggest that the operators of online labor platforms should display information about freelancers that relates to country of origin, along with reviews, ratings, and rates earned in the same skill category. Therefore, to address the uncertainty of the quality of freelancer services, a key solution would be to build trust in digital markets through displaying the different characteristics of freelancers, to examine the past performance of freelancers (Dellarocas 2003). An online referencing system with such information is also an effective way to mitigate risks arising from the expansion of informal practices globally (Kovács et al. 2017). This action would benefit freelancers, especially in developing countries, and would help employers to identify freelancers who would be the most suitable for specific tasks or projects. Moreover, this adjustment could help freelancers who are new to the platforms present their skills in a context that lowers the ”first-job barrier” and enhances their competitiveness with experienced users of the platform. In addition, it is suggested that platforms publish data on wages, and then fair rates could be arbitrated. Publishing wage data would also permit comparisons by employers internally as well with others, or against a benchmarked rate (Lustig et al. 2020). Online labor platforms employ algorithms that move work opportunities away from workers with unsatisfactory ratings, which makes staying on the platform a less feasible route to earning money. Algorithmic control is essential to the business of online labor platforms (Durlauf 2019).

7. Conclusions

This research focuses on how employers decide which freelancers to hire. Three characteristic variables of freelancers are considered, i.e., country background, amount earned, and active duration time on the platform. Four hypotheses are tested, three of which are supported, confirming some of the characteristics influencing employer hiring decisions. Based on these supported hypotheses, several conclusions can be drawn. First, employers prefer freelancers who come from the same country and cultural background as they do. This may be because freelancers are more comfortable with cultures they are familiar with and, for the practical reason, communications are easier when the parties involved speak the same language. Second, employers are more likely to select new workers than experienced workers. Their reasoning may be that new freelancers are more likely to know and possess the latest techniques and skill sets and are willing to accept a lower wage than experienced freelancers. Third, an experienced freelancer (measured by income earned) is less likely to be awarded a project than the new freelancer. This result indicates that employers prefer newcomers with lower bids and, given they have less prior experience, are unlikely to attempt to negotiate wages. This indicates that employers are more concerned about cost (wage) versus experience in getting the job done.

This study is not without limitations. The first limitation is regarding the dataset. Data used in this research were only collected from Freelancer.com, one of the online labor platforms whose data are readily available. Therefore, the research results may only be valid for this one platform and could easily vary platform to platform. Each platform has unique features that distinguish it from other platforms, thus providing different characteristics of its users. Secondly, this research explores several associations with select but limited independent variables and dependent variables. There may be other factors that influence the decision of employers in addition to the variables included in this study. For example, such variables as age, gender, and educational background are not included in this research. Moreover, only structured data are applied in this research, while textual unstructured data, such as a description of each user, have not been included. It would be interesting to consider such unstructured data to test how users introduce themselves impacts employer decisions. Thirdly, the results of this research may be biased in favor of new users given that online labor platforms are relatively young; thus, new users outnumber old users by a significant margin and that the difference may have a discriminative power when applying the analysis. Nevertheless, the results are conclusive. Fourth, the P–E fit framework is applied in an exploratory way in this research. Examining the additional components and dimensions of the multifaceted P–E fit model may reveal additional insights into freelancing both at the national and the global level, for example, comparing countries and regions.

While this research highlights a few of the freelancers’ characteristics, future research could include more characteristics for freelancers. Future studies could also obtain and analyze data from multiple platforms to verify the hypotheses and to explore the associations between relevant factors of freelancers and the decisions made by employers. In addition, while the current research focuses on an online labor-based platform, there is value in investigating factors relating to the decisions of clients who use asset-based platforms. Research on freelancing in online labor platforms is at a nascent stage, and therefore, there is great potential for research opportunities that would accelerate the understanding of this field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R., V.R. and W.R.; Methodology, J.R., V.R. and W.R; Software, J.R., V.R. and W.R; Validation, J.R., V.R. and W.R; Formal analysis, J.R., V.R. and W.R; Investigation, J.R., V.R. and W.R; Resources, J.R., V.R. and W.R; Data curation, J.R., V.R. and W.R; Writing—original draft, J.R., V.R. and W.R; Writing—review & editing, J.R., V.R. and W.R; Visualization, J.R., V.R. and W.R; Supervision, J.R., V.R. and W.R; Project administration, J.R., V.R. and W.R. All authors contributed equally to the preparation and submission of this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abreu, Maria, Ozge Oner, Aleid Brouwer, and Eveline van Leeuwen. 2019. Well-being effects of self-employment: A spatial inquiry. Journal of Business Venturing 34: 589–607. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, Herman, and Sola O. Lawal. 2013. eLancing: A review and research agenda for bridging the science–practice gap. Human Resource Management Review 23: 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez De La Vega, Juan, Marta Cecchinato, and John Rooksby. 2021. “Why lose control?” A Study of Freelancers’ Experiences with Gig Economy Platforms. Paper presented at the CHI ‘21: Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, May 8–13; p. 455. [Google Scholar]

- Annink, Anne. 2017. From social support to capabilities for the work–life balance of independent professionals. Journal of Management & Organization 23: 258–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoobzadeh, Mostafa. 2022. Freelance job search during times of uncertainty: Protean career orientation, career competencies and job search. Personnel Review 51: 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baitenizov, Daniyar T., Igor N. Dubina, David F. J. Campbell, Elias G. Carayannis, and Tolkyn A. Azatbek. 2019. Freelance as a creative mode of self-employment in a new economy (a literature review). Journal of the Knowledge Economy 10: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Barlage, Melody, Arjan van den Born, and Arjen van Witteloostuijn. 2019. The needs of freelancers and the characteristics of ‘gigs’: Creating beneficial relations between freelancers and their hiring organizations. Emerald Open Research 1: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barley, Stephen R., Beth A. Bechky, and Frances J. Milliken. 2017. The changing nature of work: Careers, identities, and work lives in the 21st century. Academy of Management Discoveries 3: 111–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögenhold, Dieter, and Andrea Klinglmair. 2016. Independent work, modern organizations and entrepreneurial labor: Diversity and hybridity of freelancers and self-employment. Journal of Management & Organization 22: 843–58. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, Corine, and Deanne N. Den Hartog. 2011. Human resource management, Person-Environment Fit, and trust. In Trust and Human Resource Management. Edited by Rosalind Searle and Denise Skinner. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, pp. 109–21. [Google Scholar]

- Borchert, Kathrin, Matthias Hirth, Michael E. Kummer, Ulrich Laitenberger, Olga Slivko, and Steffen Viete. 2018. Unemployment and Online Labor. Discussion Paper (18-023). Mannheim: ZEW-Centre for European Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, Simon. 2016. Self-employment: Deviation or the norm? Journal of Management & Organization 22: 764–78. [Google Scholar]

- Burtch, Gordon, Anindya Ghose, and Sunil Wattal. 2012. An empirical examination of cultural biases in interpersonal economic exchange. International Conference on Interaction Sciences 2012: 4. [Google Scholar]

- Cable, Daniel M., and Timothy A. Judge. 1996. Person-Organization Fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 67: 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, Robert D. 1987. Person-environment Fit theory and organizations: Commensurate dimensions, time perspectives, and mechanisms. Journal of Vocational Behavior 31: 248–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, Robert D., and R. Van Harrison. 1993. Person-environment Fit theory: Some history, recent developments, and future directions. Journal of Social Issues 49: 253–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, Jennifer A. 1989. Improving interactional organizational research: A model of Person-Organization Fit. Academy of Management Review 14: 333–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauradia, Amit J., and Ruchi A. Galande. 2015. Freelance Human Capital: A Firm-Level Perspective. Dublin: Senate Hall Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, Neil, Peter Villanova, and Shawn Mikulay. 1997. Political influence compatibility: Fitting the person to the climate. Journal of Organizational Behavior 18: 709–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Aichia, Chi-Tai Shen, and Timothy A. Judge. 2016. Development of a multidimensional instrument of PersonEnvironment Fit: The Perceived Person-Environment Fit Scale (PPEFS). Applied Psychology 65: 66–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claus, Lisbeth, Adelaida Patrasc Lungu, and Sutapa Bhattacharjee. 2011. The effects of individual, organizational and societal variables on the job performance of expatriate managers. International Journal of Management 28: 249. [Google Scholar]

- Claussen, Jörg, Pooyan Khashabi, Tobias Kretschmer, and Mareike Seifried. 2018. Knowledge Work in the Sharing Economy: What Drives Project Success in Online Labor Markets? (October 2018). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3102865 (accessed on 1 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Cockayne, Daniel G. 2016. Sharing and neoliberal discourse: The economic function of sharing in the digital on-demand economy. Geoforum 77: 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Damian, Daniela, and Ciprian Manea. 2019. Causal recipes for turning fin-tech freelancers into smart entrepreneurs. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 4: 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Dawis, Rene V. 1992. Person-Environment Fit and job satisfaction. In Job Satisfaction. Edited by C. J. Cranny, Patricia Caine Smith and Eugene F. Stone. New York: Lexington, pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Dawis, Rene V., and L. H. Lofquist. 1984. A psychological theory of work adjustment. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dawis, Rene V., George W. England, and Lloyd H. Lofquist. 1964. A Theory of Work Adjustment, Minnesota Studies in Vocational Rehabilitation, XV. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, Industrial Relations Center, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- de Jager, Ward, Clare Kelliher, Pascale Peters, Rob Blomme, and Yuka Sakamoto. 2016. Fit for self-employment? An extended Person–Environment Fit approach to understand the work–life interface of self-employed workers. Journal of Management & Organization 22: 797–816. [Google Scholar]

- Dellarocas, Chrysanthos. 2003. The digitization of word of mouth: Promise and challenges of online feedback mechanisms. Management Science 49: 1407–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, Michael, Fabian Stephany, Steven Sawyer, Isabel Munoz, Raghav Raheja, Gabrielle Vaccaro, and Vili Lehdonvirta. 2020. When Motivation Becomes Desperation: Online Freelancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/67ptf/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Durlauf, Maria. 2019. The Commodification of Digital Labor in the Gig Economy: Online Outsourcing, Insecure Employment, and Platform-based Rating and Ranking Systems. Psychosociological Issues in Human Resource Management 7: 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Jeffrey R., and Abbie J. Shipp. 2007. The relationship between person-environment Fit and outcomes: An integrative theoretical framework. In Perspectives on Organizational Fit. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 209–58. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Jeffrey R., and Daniel M. Cable. 2009. The value of value congruence. Journal of Applied Psychology 94: 654–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Jeffrey R., Robert D. Caplan, and R. Van Harrison. 1998. Person-environment Fit theory. Theories of Organizational Stress 28: 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Julian A., and Jon Billsberry. 2010. Testing a multidimensional theory of Person-Environment Fit. Journal of Managerial Issues 22: 476–93. [Google Scholar]

- Elstad, Beate. 2015. Freelancing: Cool jobs or bad jobs? Nordisk Kulturpolitisk Tidsskrift 18: 101–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. 2017. Taking a Look at Self-Employed in the EU. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20170906-1 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Fenwick, Tara J. 2006. Contradictions in portfolio careers: Work design and client relations. Career Development International 11: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, John R. P., Robert D. Caplan, and R. Van Harrison. 1982. The Mechanisms of Job Stress and Strain. London: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Galperin, Hernan, and Catrihel Greppi. 2017. Geographical Discrimination in Digital Labor Platforms. February 23. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2922874 (accessed on 1 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Garin, Andrew, Emilie Jackson, Dmitri K. Koustas, and Carl McPherson. 2020. Is New Platform Work Different from Other Freelancing? AEA Papers and Proceedings 110: 157–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Elizabeth, and Carmen Kaman Ng. 1997. Managing an externalized workforce: Freelance labor-use in the UK book publishing industry. Industrial Relations Journal 28: 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Herrera, Estrella, Bertin Martens, and Frank Mueller-Langer. 2017. Trade, Competition and Welfare in Global Online Labour Markets: A ‘Gig Economy’ Case Study. December 20. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3090929 (accessed on 1 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Graham, Mark, Isis Hjorth, and Vili Lehdonvirta. 2017. Digital labor and development: Impacts of global digital labor platforms and the gig economy on worker livelihoods. Transfer: European Review of Labor and Research 23: 135–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Varun, Jose Maria Fernandez-Crehuet, Chetna Gupta, and Thomas Hanne. 2020a. Freelancing models for fostering innovation and problem solving in software startups: An empirical comparative study. Sustainability 12: 10106. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Varun, Jose Maria Fernandez-Crehuet, Thomas Hanne, and Rainer Telesko. 2020b. Fostering product innovations in software startups through freelancer supported requirement engineering. Results in Engineering 8: 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannák, Anikó, Claudia Wagner, David Garcia, Alan Mislove, Markus Strohmaier, and Christo Wilson. 2017. Bias in online freelance marketplaces: Evidence from taskrabbit and fiverr. Paper presented at the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Portland, OR, USA, February 25–March 1; pp. 1914–33. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, John L. 1985. Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of Careers. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Holtz, David M., Liane Scult, and Siddharth Suri. 2022. How Much Do Platform Workers Value Reviews? An Experimental Method. Paper presented at the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, April 29–May 5; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Yili, and Paul A. Pavlou. 2017. On buyer selection of service providers in online outsourcing platforms for IT services. Information Systems Research 28: 547–62. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, John J. 2010. Online labor markets. In International Workshop on Internet and Network Economics. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 515–22. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, John J. 2017. Price Floors and Employer Preferences: Evidence from a Minimum Wage Experiment. January 13. Available online: https://ssrn.com/astract=2898827 (accessed on 1 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Horton, John Joseph, and Lydia B. Chilton. 2010. The labor economics of paid crowdsourcing. Paper presented at the 11th ACM Conference on Electronic Commerce, Cambridge, MA, USA, June 7–11; pp. 209–18. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, John, William R. Kerr, and Christopher Stanton. 2018. 3. Digital Labor Markets and Global Talent Flows. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 71–108. [Google Scholar]

- Huđek, Ivona, Polona Tominc, and Karin Širec. 2021. The Human Capital of the Freelancers and Their Satisfaction with the Quality of Life. Sustainability 13: 11490. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, Karen J., and Amy L. Kristof-Brown. 2005. Marching to the beat of a different drummer: Examining the impact of pacing congruence. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 97: 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Johal, Suneeta, and George Anastasi. 2015. From professional contractor to independent professional: The evolution of freelancing in the UK. Small Enterprise Research 22: 159–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathuria, Abhishek, Terence Saldanha, Jiban Khuntia, Mariana Andrade Rojas, Sunil Mithas, and Hyeyoung Hah. 2021. Inferring Supplier Quality in the Gig Economy: The Effectiveness of Signals in Freelance Job Markets. Paper presented at the 54th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, HI, USA, January 5; p. 6583. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Lawrence F., and Alan B. Krueger. 2017. The role of unemployment in the rise in alternative work arrangements. American Economic Review 107: 388–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, T. Tony, and Yuting Zhu. 2021. Cheap Talk on Freelance Platforms. Management Science 67: 5901–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Michael. 2005. An Integrative Investigation of Person-Vocation Fit, Person-Organization Fit, and Person-Job Fit Perceptions. Doctoral dissertation, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA. Available online: http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc4768/m2/1/high_res_d/dissertation.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Kitching, John, and David Smallbone. 2012. Are freelancers a neglected form of small business? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 19: 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkodis, Marios, and Panagiotis G. Ipeirotis. 2016. Reputation transferability in online labor markets. Management Science 62: 1687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Borbála, Jeremy Morris, Abel Polese, and Drini Imami. 2017. Looking at the ‘sharing ‘economies concept through the prism. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 10: 365–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, Amy L. 1996. Person–Organization Fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Personnel Psychology 49: 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, Amy L., Ryan D. Zimmerman, and Erin C. Johnson. 2005. Consequences of individuals’ Fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and Person–Supervisor Fit. Personnel Psychology 58: 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehdonvirta, Vili. 2018. Flexibility in the gig economy: Managing time on three online piecework platforms. New Technology, Work and Employment 33: 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehdonvirta, Vili, Otto Kässi, Isis Hjorth, Helena Barnard, and Mark Graham. 2019. The global platform economy: A new offshoring institution enabling emerging-economy micro providers. Journal of Management 45: 567–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, Kurt. 1935. Dynamic Theory of Personality. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Presti, Alessandro, Sara Pluviano, and Jon P. Briscoe. 2018. Are freelancers a breed apart? The role of protean and boundaryless career attitudes in employability and career success. Human Resource Management Journal 28: 427–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustig, Caitlin, Sean Rintel, Liane Scult, and Siddharth Suri. 2020. Stuck in the middle with you: The transaction costs of corporate employees hiring freelancers. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 4: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Quan D. 2021. Unclear signals, uncertain prospects: The labor market consequences of freelancing in the new economy. Social Forces 99: 895–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, Tui. 2016. A consilience framework: Revealing hidden features of the independent contractor. Journal of Management & Organization 22: 779–96. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown, Tui, and Patricia Leighton. 2016. Working as a self-employed professional, freelancer, contractor, consultant… issues, questions… and solutions? Journal of Management & Organization 22: 751–55. [Google Scholar]

- Meager, Nigel. 2016. Foreword: JMO special issue on self-employment/freelancing. Journal of Management & Organization 22: 756–63. [Google Scholar]

- Meglino, Bruce M., and Elizabeth C. Ravlin. 1998. Individual values in organizations: Concepts, controversies, and research. Journal of Management 24: 351–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melián-González, Santiago, and Jacques Bulchand-Gidumal. 2018. What type of labor lies behind the on-demand economy? New research based on workers’ data. Journal of Management & Organization, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Muchinsky, Paul M., and Carlyn J. Monahan. 1987. What is person-environment congruence? Supplementary versus complementary models of fit. Journal of Vocational Behavior 31: 268–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, Isabel, Michael Dunn, Steve Sawyer, and Emily Michaels. 2022. Platform-mediated Markets, Online Freelance Workers and Deconstructed Identities. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 6: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, Zubair, Jing Zhang, Rafiq Mansoor, Saba Hafeez, and Aboobucker Ilmudeen. 2020. Freelancers as part-time employees: Dimensions of FVP and FJS in E-lancing platforms. South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management 7: 34–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemkova, Ekaterina, Pelin Demirel, and Linda Baines. 2019. In search of meaningful work on digital freelancing platforms: The case of design professionals. New Technology, Work and Employment 34: 226–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, Milena. 2019. Switching to self-employment can be good for your health. Journal of Business Venturing 34: 664–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norbäck, Maria, and Alexander Styhre. 2019. Making it work in free agent work: The coping practices of Swedish freelance journalists. Scandinavian Journal of Management 35: 101076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obschonka, Martin, Eva Schmitt-Rodermund, and Antonio Terracciano. 2014. Personality and the gender gap in self-employment: A multi-nation study. PLoS ONE 9: e103805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, Charles A., III, Jennifer Chatman, and David F. Caldwell. 1991. People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing Person-Organization Fit. Academy of Management Journal 34: 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterman, Paul. 2022. How American adults obtain work skills: Results of a new national survey. ILR Review 75: 578–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, Cheri, and Mathis Schulte. 2007. Multiple perspectives of Fit in organizations across levels of analysis. In Perspectives on Organizational Fit. Edited by Cheri Ostroff and Timothy A. Judge. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 287–315. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Pascale, Rob Blomme, Ward De Jager, and Beatrice Van Der Heijden. 2020. The impact of work-related values and work control on the career satisfaction of female freelancers. Small Business Economics 55: 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongratz, Hans J. 2018. Of crowds and talents: Discursive constructions of global online labor. New Technology, Work and Employment 33: 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, Teresa Shuk-Ching. 2019. Independent workers: Growth trends, categories, and employee relations implications in the emerging gig economy. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 31: 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popiel, Pawel. 2017. “Boundaryless” in the creative economy: Assessing freelancing on Upwork. Critical Studies in Media Communication 34: 220–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Jie, Viju Raghupathi, and Wullianallur Raghupathi. 2020. Determinants of Startup Funding: The Interaction between Web Attention and Culture. Journal of International Technology and Information Management 29: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, William M., III, Sara Horowitz, and Gabrielle Wuolo. 2014. The impact of client nonpayment on the income of contingent workers: Evidence from the freelancers union independent worker survey. ILR Review 67: 702–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokeach, Milton. 1973. The Nature of Human Values. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Ann Marie, and Mark J. Schmit. 1996. An assessment of organizational climate and P-E fit: A tool for organizational change. The International Journal of Organizational Analysis 4: 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S., M. Dunn, I. Munoz, F. Stephany, R. Raheja, G. Vaccaro, and V. Lehdonvirta. 2020. Freelancing Online during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/uploads/prod/2020/07/NFW-Sawyer-etal-Freelancing-COVID19.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Scaraboto, Daiane, and Bernardo Figueiredo. 2022. How consumer orchestration work creates value in the sharing economy. Journal of Marketing 86: 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B., A. L. Kristof-Brown, H. W. Goldstein, and B. D. Smith. 1997. What is this thing called fit? In International Handbook of Selection and Assessment. Edited by N. Anderson and P. Herriot. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 393–412. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Benjamin. 1987. The people make the place. Personnel Psychology 40: 437–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, Michael, and Nicolas Haas. 2011. Determinants of reverse auction results: An empirical examination of Freelancer.com. Paper presented at the European Conference on Information Systems 2011. ECIS 2011 Proceedings; p. 89. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2011/89 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Schulze, Thimo, Simone Krug, and Martin Schader. 2012. Workers’ task choice in crowdsourcing and human computation markets. Paper presented at the Thirty Third International Conference on Information Systems, Orlando, FL, USA, December 16–19; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 1992. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 25: 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi, Tomoki. 2004. Person-organization fit and person-job fit in employee selection: A review of the literature. Osaka Keidai Ronshu 54: 179–96. [Google Scholar]

- Shevchuk, Andrey, Denis Strebkov, and Shannon N. Davis. 2015. Educational mismatch, gender, and satisfaction in self-employment: The case of Russian-language internet freelancers. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 40: 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, Rabeya, Il Im, and Kun Shin Im. 2019. Do IT freelancers increase their entrepreneurial behavior and performance by using IT self-efficacy and social capital? Evidence from Bangladesh. Information & Management 56: 103133. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, Will, Mohammad Hossein Jarrahi, Michael Dunn, and Sarah Beth Nelson. 2020. Work precarity and gig literacies in online freelancing. Work, Employment and Society 34: 457–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrett, Michel. 2016. Independent professionals (IPros) and well-being: An emerging focus for research? Journal of Management & Organization 22: 817–25. [Google Scholar]

- Talbot, Danielle L., and Jon Billsberry. 2010. Comparing and contrasting person-environment Fit and misfit. Paper presented at the 4th Global e-Conference on Fit, Coventry, UK, December 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tom, Victor R. 1971. The role of personality and organizational images in the recruiting process. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 6: 573–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, Ilona, Sanna Heinänen, and Kirsimarja Blomqvist. 2020. Freelancing on digital work platforms–roles of virtual community trust and work engagement on person–job fit. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems 50: 553–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, Azka. 2017. Individual Work Behavior in Online Labor Markets: Temporality and Job Satisfaction. Paper presented at the 13th International Symposium on Open Collaboration Companion, Galway, Ireland, August 23–25; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Born, Arjan, and Arjen Van Witteloostuijn. 2013. Drivers of freelance career success. Journal of Organizational Behavior 34: 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zwan, Peter, Jolanda Hessels, and Martijn Burger. 2020. Happy Free Willies? Investigating the relationship between freelancing and subjective well-being. Small Bus Econ 55: 475–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancouver, Jeffrey B., and Neal W. Schmitt. 1991. An exploratory examination of person–organization fit: Organizational goal congruence. Personnel Psychology 44: 333–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verquer, Michelle L., Terry A. Beehr, and Stephen H. Wagner. 2003. A meta-analysis of relations between person– organization Fit and work attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior 63: 473–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, Gerit, Julian Prester, and Guy Paré. 2021. Exploring the boundaries and processes of digital platforms for knowledge work: A review of information systems research. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 30: 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, L. Alan, and Lendell G. Nye. 1992. Organizational Goal Congruence and Job Attitudes Revisited. Oklahoma City: FAA Civil Aeromedical Inst. [Google Scholar]

- Yaraghi, Niam, and Shamika Ravi. 2017. The Current and Future State of the Sharing Economy. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/sharingeconomy_032017final.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Yu, Kang Yang Trevor. 2016. Inter-Relationships among different types of Person-Environment Fit and job satisfaction. Applied Psychology 65: 38–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadik, Yair, Liad Bareket-Bojmel, Aharon Tziner, and Or Shloker. 2019. Freelancers: A Manager’s Perspective on the Phenomenon. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 35: 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Qiang, B. J. Allen, Richard T. Gretz, and Mark B. Houston. 2022. Platform exploitation: When service agents defect with customers from online service platforms. Journal of Marketing 86: 105–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žunac, Ana Globočnik, Sanja Zlatić, and Krešimir Buntak. 2021. Freelancing in Croatia: Differences among Regions, Company Sizes, Industries and Markets. Business Systems Research: International Journal of the Society for Advancing Innovation and Research in Economy 12: 109–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |