Abstract

This study examines the notion of governance while corruption and polity act in a negotiated approach. It adopts a theory synthesis approach to design the research paradigm and brings renewed attention to governance from a national perspective. This study argues that corruption and polity collectively define the state of governance in a particular country, which might offer some new insights to the remaining parts of the world. The principal aim of the study is to bring relevant evidence from the literature to develop a solid foundation on governance from a macro perspective. Deploying a qualitative approach, this study highlights available literature on corruption, polity, and their connections to define the state of governance. From this specific target, we have initiated this study deploying a conceptual fashion in exploring governance which is shaped by the interplay between two loosely connected themes: polity and corruption. The outcome of this synthesis is to renew our understanding on governance to strengthen the governance mechanism whereby corruption could be checked through sound polity in action. The arguments presented in the paper are expected to be useful for regulators and policymakers as they prepare governance-related rules, acts, or directives in their respective countries.

JEL Classification:

D73; G18; G30; G38; K10

1. Introduction

Governance, as a term, offers a wider scope and is very broad and multifaceted as a concept (Al-Faryan and Shil 2022). It includes various goals (e.g., political, economic, and social) necessary for development. The concept of governance has been adopted and developed since the 1980s to denounce extravagancy and misuse in managing public funds (Al-Faryan and Shil 2022). Through governance mechanisms, public institutions run public affairs and manage public resources more efficiently to promote the rule of law and realize human rights (e.g., economic, political, civil, cultural, and social). It is the legitimate, accountable, and effective way of obtaining and using public resources and authority in the intertest of widely accepted social objectives and goals (Johnston and Kpundeh 2004). Good governance refers to every institutional form and structure that promote public legitimacy and desired substantive outcomes (Rose-Ackerman 2017). It is also connected with ethical universalism (Mungiu-Pippidi 2015), impartiality (Rothstein and Varraich 2009), and open-access orders (North et al. 2009).

While defining good governance, the World Bank considers the institutions and traditions by which authority or power in a country is exercised, including (a) the capacity of formulating and implementing sound government policies effectively; (b) the process of selecting, monitoring, and replacing governments; and (c) the respect (by the citizens and the state) for the institutions governing social and economic interactions among them (Kaufmann et al. 1999). It is strongly connected to the fight against corruption. As a result, some of the core principles of good governance resemble those of anti-corruption. The European Union Commission, for example, in its EU Anti-Corruption Report (European Commission 2014), states:

Corruption seriously harms the economy and society as a whole. Many countries around the world suffer from deep-rooted corruption that hampers economic development, undermines democracy, and damages social justice and the rule of law. It impinges on good governance, sound management of public money, and competitive markets. In extreme cases, it undermines the trust of citizens in democratic institutions and processes.

Good governance is also connected with the different principles of various political systems. Say, for example, that Rothstein and Teorell (2008) advocate eight principles of political systems, such as participatory, responsive, consistent with the rule of law, consensus-oriented, equitable and inclusive, effective and efficient, accountable, and transparent. Institutions might not be able to deliver public services and fulfill people’s needs if political systems fail to ensure each of these eight principles. However, understanding the extent of adherence to good governance principles by different countries is a complex and challenging task.

Governance, as an inclusive term, provides a wider scope across definition, measurement, and application. Thus, the applicability of governance mechanisms is contextual, and the absence of conceptual clarity may lead to operational difficulty. In general, good governance symbolizes a strong partnership between the state and society and among its citizens, linking transparency, the rule of law, and accountability. To measure the state of good governance, there are some popular indices, e.g., the Index of Public Integrity (IPI), the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) of the World Bank, and the Freedom in the World report of Freedom House. Some indices are also available with a regional focus, such as the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG). Each of these indices examines different aspects of governance and considers various indicators to measure good governance. For example, the WGI index of good governance measures the six aspects of governance (voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption) to calculate the index value in a range between −2.5 and +2.5. Similarly, the three-fold objectives of IPI are: (a) ensuring the spending of public resources without corruption, (b) assessing the corruption control capacity of a society, and (c) holding its government accountable (Mungiu-Pippidi et al. 2017). To achieve these objectives, the IPI considers various aspects, e.g., budget transparency, administrative burden, trade openness, judicial independence, citizenship, and freedom of the press. Based on surveys covering more than 120,000 households and 3800 experts, the Rule of Law Index of the World Justice Project measures how the rule of law is perceived and experienced by the public worldwide. On the other hand, the Values Survey provides a worldwide ranking of countries based on how citizens perceive the quality of governance in their own countries (Ivanyna and Shah 2014). Furthermore, localized studies also provide considerable insights on the measures and indicators of governance, though these are limited in their general applicability (see, e.g., Moore 1993; Olken and Pande 2012). Based on the above discussion, the current paper sets the following research questions:

- (a)

- Does good governance relate to the interplay between corruption and polity in a particular country?

- (b)

- How do the regulators/policy makers address the level of corruption and polity in devising country-specific governance guidelines/acts/directives?

Promotion of good governance in various aspects (for example, improving the efficiency and accountability of the public sector, ensuring the rule of law, tackling corruption, etc.) are essential elements for economies to prosper (IMF 2005). The paper contributes to the existing body of knowledge in two ways. It identifies a loose connectivity between ‘corruption’ and ‘polity’ in the existing literature and highlights the state of governance based on the governance–corruption–polity triad. It applies the tradition of a conceptual study with a theory synthesis paradigm, whereby selected key themes are presented to provide additional insights on governance.

Keeping the objectives and scope of the study in mind, the remaining part of the study is structured as follows. After the introduction presented in Section 1, relevant discussion on research methods is presented in Section 2, which also proposes a conceptual framework. Section 3 elaborates the key theme of the study, ‘corruption’. Another key theme of the study, ‘polity’, is discussed in Section 4. An overall discussion of the study is highlighted in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Research Method and Conceptual Framework

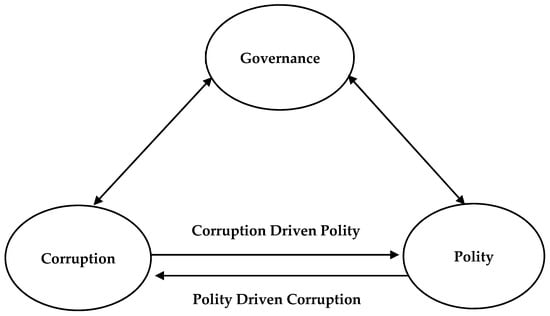

This study adopts a qualitative research paradigm, whereby the selected research question has been answered with the help of existing research. Based on the author’s experiences and understanding of the notion of ‘governance’, 2 important themes, say, corruption and polity, are identified. Later on, a conceptual framework has been developed (Figure 1) to bring new insights into the extant literature, whereby the interplay between corruption and polity provides renewed attention to governance from a national perspective. Polity and corruption regularly negotiate and renegotiate to set the tune of public services, which ultimately affect the state of governance. This study argues that the polity of a nation is being driven by different factors that ultimately impact corruption. The governance mechanism directly addresses the corruption attempts as an antidote, and thus, they are interlinked and connected in a cycle.

Figure 1.

Governance, corruption, and polity triad (conceptual framework). Source: authors own compilation.

It is always a challenge for researchers to write articles based on non-empirical data. This study is also based on existing literature, which supports a new understanding of governance by connecting some key terms. As a result, it employs a literature review approach to gather relevant literature. After surveying scholarly articles, books, and any other sources pertinent to an issue, area of research, or theory, a literature review generates a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these materials in relation to the research problem being investigated (Fink 2014). Using the key terminologies of the study, i.e., governance, corruption, and polity, we have searched the Google Scholar database and selected relevant papers in line with our review protocol and exclusion and inclusion criteria. We studied the abstracts of selected papers to confirm our initial selection, which is further scrutinized after thorough reading of the articles. We have codified the selected articles to generate sub-themes under the major themes of the study, based on which the paper is structured. It adopts a theoretical review to examine the corpus of governance that has accumulated with regard to corruption and polity. This review helps to identify the theories that already exist, any relationships between them, and the extent to which the existing theories have been investigated (Baumeister and Leary 1997).

Out of 4 approaches (theory adaptation, theory synthesis, model, and typology) to writing conceptual articles (Jaakkola 2020), we have adopted theory synthesis in this study to support our research design. Research design addresses decisions about how to achieve research goals, link theories, set questions, and identify objectives with the deployment of appropriate resources and the selection of the right methods (Flick 2018). We have taken governance as a focal phenomenon in this study, which has not been sufficiently explored in existing research with reference to polity. It is important to know how polity leads to corruption and how corruption leads to polity, and this research considers these as conceptual ingredients of the selected phenomenon. We considered governance as a domain, as well as new relationships between various constructs such as governance, corruption, and polity. These constructs are literature streams, and we adopt theory synthesis to achieve conceptual integration (Jaakkola 2020). As part of a tradition of theory synthesis, we have summarized and integrated the extant knowledge of selected concepts. A theory synthesis paper focuses on conceptual rather than empirical work and puts together a collection of theories under a theoretical umbrella for further study. Our governance, corruption, and polity triad (Figure 1) represents a novel conceptual framework in which we attempted to integrate 3 phenomena in order to develop a better understanding of governance.

3. Corruption

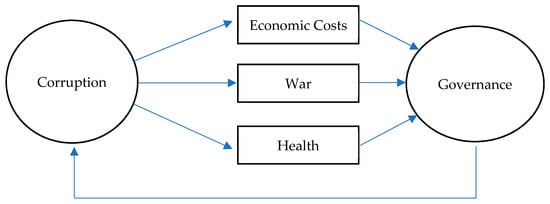

The nexus between corruption and governance examines the institutional bases of development, economic growth, and living conditions (Salihu 2022). Economic growth and development are affected by corruption (Al-Faryan 2022), which slows down the economic pace, generates losses, misuses people’s assets, causes budget damage, and widens the gap between the rich and the poor, thus increasing poverty (Dang et al. 2022). A “pure” definition of corruption is problematic because of ambiguities. It is likewise unclear whether the wasta as originally practiced was corrupt. Transparency International (2019) defines corruption as the misuse of power entrusted to someone for personal gain. This leaves open the question of what constitutes abuse of power. Transparency International adds that corruption hurts everyone who depends on the integrity of people who hold authoritative positions. This claim suggests that power is misused when people are hurt by an official’s actions if the official is acting for personal gain. Control of corruption reflects perceptions of the extent to which authoritative power is exercised for personal gain (both petty and grand forms of corruption), as well as, of the extent to which the state is captured by the elites and private interest holders (Ogundajo et al. 2022). Corruption and good governance maintain a two-way causality and feed off each other in a nasty circle. Corrupted practices are chosen and implemented as an opportunity in the absence of good governance principles and structures. On the other hand, corruption can prevent the application of good governance principles and structures. Corruption is closely associated with violations of the principles of accountability, transparency, and the rule of law. To draw specific attention, this study synthesizes the effects of corruption, linking them with governance as presented in Figure 2 below:

Figure 2.

Corruption and governance. Source: authors own compilation.

3.1. Measuring Corruption

3.1.1. Polity IV Project

The Polity IV Project (Marshall and Cole 2011) does not measure corruption directly. Instead, it provides various measures of governance. These comprise effectiveness, fragility, security effectiveness, legitimacy, security legitimacy, armed conflict, political legitimacy, political effectiveness, regime type (democracy or autocracy), economic effectiveness, economic legitimacy, oil production and consumption, social effectiveness, and social legitimacy. Some of these are based on relatively objective measures; the social effectiveness measure, for instance, is based on the United Nations (UN) Development Project’s Human Development (HDP) score, while the social legitimacy measure is based on the US Census Bureau’s Infant Mortality Rate. In other instances, they are based on manipulations of other indicators; the fragility measure, for instance, is a combination of the effectiveness score and the legitimacy score.

3.1.2. The Corruption Perceptions Index

The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), measured by Transparency International, is unlike the Polity IV Project in that it is not based on objective measures. Instead, it is based on people’s impressions of countries. These people may be inhabitants of a given country or visitors such as businessman, indeed, anyone who has regular or protracted contact with the country. Each country’s CPI score is then calculated from these impressions. As Hawthorne (2013) observes, it is essentially a “poll of polls” (p. 1). Thus, the CPI suffers from the flaw that people are not always objective and that, in any event, values change over time. Moreover, Transparency International’s precise methodology changes over time, which makes using it for time-series analyses problematic.

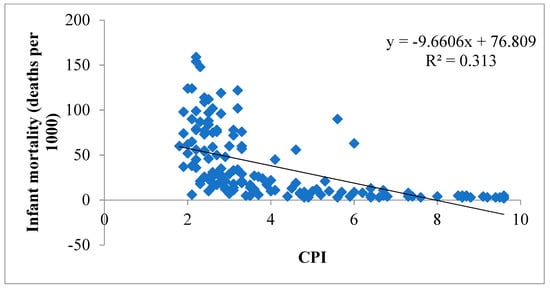

Despite such problems, the CPI is highly correlated with other measures. It correlates, for instance, with infant mortality (deaths per 1000 children aged under one year). Figure 3 plots the CPI against infant mortality for 152 nations in 2006 (data were excluded because they were absent for some countries). Data from 2006 were used because they were the latest easily available data from the World Health Organization (WHO). As can be seen, almost all the highly corrupt countries (for convenience, CPI < 4) have higher infant mortality than the honest countries (for convenience, CPI > 6). Indeed, the correlation between the two variables is moderately high (r = 0.56), explaining about 30% of the variance. This provides two things: (a) prima facie evidence that the CPI is measuring something, though not necessarily with perfect validity; and (b) evidence that corruption is associated with infant mortality. This in turn suggests that corruption possibly causes infant mortality; indeed, the World Bank (2013) reports that corruption causes 75% of infant mortality in poor countries. Thus, infant mortality is a very important parameter to understand the level of corruption embedded in a country, which is captured very aptly in calculating the CPI score.

Figure 3.

Correlation between CPI and infant mortality.

The CPI has also been tested against other measures of corruption. Wilhelm (2022), for instance, tested it against two measures: black market activity and an overabundance of regulation (or unnecessary regulation of business activity). The study found high correlations between all three measures. The same study also tested the measures against real per capita GDP. Again, there were high correlations, with the highest being for the CPI; the CPI explained over 75% of the variance in per capita GDP, with the most corrupt countries being the poorest. The CPI has also been tested, for member countries of the EU, against the EU’s Special Eurobarometer (face-to-face interviews with between 500 and 1000 individuals in each of the EU’s member states) and the EU’s Flash Barometer (phone interviews with representatives of businesses in Europe’s energy, construction, healthcare, telecommunications, manufacturing, and financial sectors) (European Commission 2014). Again, correlations between the three measures were high.

Finally, Hawthorne (2013) observes that the CPI is, by most measures, the most cited measure of corruption used in research (Al-Faryan 2022), which suggests that researchers have confidence in it (though, of course, the researchers may be mistaken) and that, for a variety of reasons, it is probably the least flawed measure of corruption. In any event, even if the CPI is flawed, as Hawthorne comments, “a poor measure of corruption is probably still better than none at all” (p. 28). Based on this proven insight in literature, this study also considers the CPI as one of the indices to understand the state of corruption.

3.1.3. Worldwide Governance Indicators

The quality of government seriously affects economic growth (Rothstein and Teorell 2008). Examining the causal relationships between tax revenue, government expenditure, institutional quality, and economic growth, Arvin et al. (2021) conclude that stronger institutions would spur economic growth, enabling more effective macroeconomic policy formulation. The Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) are very popular for understanding the level of corruption that exists in an economy. To measure the quality of government, the WGI considers six different dimensions of governance, including voice and accountability, political stability and the absence of violence/terrorism, regulatory quality, government effectiveness, corruption control, and the rule of law (Kaufmann et al. 2010). These indicators are used as explanatory variables in different studies (Das and Andriamananjara 2006; Neumayer 2002; Kurtz and Schrank 2007). In a study, Kaufmann and Kraay (2002) examined the relationship between the WGI and income per capita. The study discovered a positive relationship between per capita income and governance quality in all participating countries. Studying the relationship between governance and economic growth in developing countries, Chauvet and Collier (2004) found that poor governance leads to unsatisfactory economic growth. The presence of some fundamental institutions (North 1991; Rodrick and Subramanian 2003), such as unbiased contract enforcement, well-defined property rights, low information gaps between buyers and sellers, and stable macroeconomic conditions, is very important to ensure economic growth. The WGI index encompasses all these parameters to measure the level of corruption and reports individual and aggregate governance indicators for over 200 countries and territories.

3.2. Effects of Corruption

Transparency International (2019) lists many problems associated with national corruption. These are broadly the same as those outlined by the European Commission (2014) and include deleterious effects on poor people’s health, both because corruption raises medical costs and because corruption diverts aid. Transparency International states that corruption also raises the prices of virtually all goods and services and helps ensure that government services are sub-optimal; it further ensures that people are not treated fairly by the police and courts, that criminals go unpunished, and that the chance of war is increased.

3.2.1. Economic Costs

The European Commission (2014) reports that corruption within EU member states alone costs €120 billion each year. This is almost certainly an underestimate. The commission, in its report, mentions neither the Common Agricultural Policy nor the Common Fisheries Policy, each of which is widely regarded as being riddled with corruption (e.g., Booker and North 2005; Craig and Elliot 2009). Much gray literature also suggests that corruption is endemic among EU politicians and bureaucrats (e.g., Craig and Elliot 2009). Indeed, the EU appears so corrupt that as soon as the European Commission’s (2014) report was published, the English MEP Daniel Hannan stated, “For the EU to lecture the member states about corruption is rather like Al Capone lecturing the cops about corruption: the charge may have an element of truth, but it’s the chutzpah that draws the eye.” Hannan’s claim is plausible. If, as the European Commission claims, corruption is present in all EU member states, it would be surprising if it were not present among EU politicians and bureaucrats.

Europe is not alone. The World Bank (2013) reports that, in 2004, worldwide an estimated US$1 trillion was paid in bribes. Given that the world economy at the time was just over US$30 trillion, this represented over 3% of economic costs. The World Bank notes that the bribes did not include embezzled public funds. Nobody knows the size of this cost, but it is plausibly enormous. The World Bank cites Transparency International’s estimate that the Indonesian leader Suharto embezzled something in the range US $15–35 billion and that Presidents Marcos (Philippines), Seko (Zaire), and Abacha (Nigeria) each embezzled up to US $5 billion. These are not the only examples of kleptocracy. In 2010, the French Supreme Court deemed admissible an investigation into the finances of leaders of the heads of state of Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon, and Equatorial Guinea. This led, eventually “to the freezing and seizure of huge assets of President Teodoro Obiang’s family from Equatorial Guinea” (Hardoon and Heinrich 2013). Moyo (2010) also reports of widespread embezzlement by African leaders, first to enrich themselves and second to finance war. The World Bank President, Jim Yong Kim, in 2013 declared corruption the greatest threat to developing countries (World Bank 2013). In a hearing before the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in May 2004; Jeffrey Winters, a professor at Northwestern University, argued that the World Bank had participated in the corruption of roughly $100 billion of its loan funds intended for development.

Moyo (2009) also speaks of the scale of corruption. In this regard, the World Bank (2013) estimates that the long-term gain of tackling corruption and improving the rule of law in poor countries leads to a fourfold increase in wealth. Again, this is plausible. Blundo et al. (2006) report that corruption is so endemic in Africa that it subverts the ability of the continent’s nation states to pay employees properly and the ability of the states to deliver effective services. Olivier de Sardan (1999) also reports that corruption in Africa is not only endemic but exists regardless of regime type or the existence (or non-existence) of sanctions against it, it is simply a way of life in sub-Saharan Africa.

3.2.2. War

The idea that corruption finances war is highly credible. The BBC (2010) reports that some of the aid generated by the 1984 Band Aid charity was systematically diverted to buy arms for the TPLF rebel movement in Ethiopia. Similarly, Nunn and Qian (2012) provide evidence that US food aid facilitates civil war in recipient countries, in part because such aid provides opportunities for corruption. Le Billon (2003) argues that corruption is a major factor in armed conflict. In like manner, Gberie (2005) argues that the Revolutionary United Front’s (RUF) corruption in Sierra Leone facilitated their atrocities in the 1991–2002 conflict with Liberia. Moreover, Gberie (2005) argues, a major tragedy of the conflict was that world leaders failed to appreciate that the RUF was so corrupt, ill-educated, and illiterate that it could not function as a serious political party. Therefore, the world leaders, by treating it as genuinely representing the people, merely prolonged the misery.

Besley and Persson (2011) present evidence that political violence, whether in the form of warfare or terrorism, is only associated with poor governance; that is, if there is good governance (and, by implication, a lack of corruption), there is little to no chance of political violence of any sort. In this regard, Chevigny (1995) notes that police violence, including use of torture, in the Americas is correlated with corruption; moreover, he states that when ordinary people have little confidence in the rule of law, they may, on the one hand, take to violence themselves (by becoming vigilantes) or, on the other hand, tolerate police violence because they see it as the only way of preventing crime.

3.2.3. Health

Corruption, as a topic of interest, has received significant attention in the health sector (Chevigny 1995). Recently, a renewed focus on weak governance and the adverse effects of corruption on the provision of health services was observed (Rispel et al. 2016). The vulnerability of the health sector to corruption arises from the asymmetry of information which is characterized by the patient and service provider relationship, the multiplicity of actors and service provisions of illness care, the uncertainty surrounding the illness experience, and the challenges of ensuring accountability in complex healthcare systems. An estimation reports that 60 billion US dollars are lost due to corruption every year in the US health sector which equals around 3% of total annual US health expenditure (Iglehart 2009). As indicated, the World Bank (2013) cites corruption as a major factor in infant mortality. Others concur, Montgomery and Elimelech (2007), for example, listing corruption as a major facilitator of poor water quality. Poor water quality, in that it facilitates gastrointestinal and other diseases, is, along with poor air quality, a major killer of poor people throughout the world (e.g., Lomborg 2001). Indeed, diarrheal diseases alone are the second most important cause of deaths in children aged under five worldwide, killing approximately 525,000 children each year (World Health Organization 2017). In this regard, Rothstein (2011) speaks of the cholera epidemic in Luanda, Angola, of 2006, which affected some 43,000 people and killed over 1600. Rothstein attributes the epidemic, which was caused by poor people having no option other than to drink polluted water and the government’s inability to deal with it, to the civil war of 2002 (which led to a huge influx of people to the city) and “the high level of corruption” (p. 2) in Angola.

There is evidence that corruption is linked to poor air quality. Bernauer and Koubi (2009), in a study of 107 cities from 42 countries, found atmospheric sulfur dioxide pollution was greater in countries with poor governance than in democracies. However, the major air pollutant that kills people is smoke from fires in homes with poor ventilation (Lomborg 2001). In this regard, Jayachandran (2009) provides evidence that the wildfires that swept Indonesia in 1997 were associated with the disappearance of 15,600 children. Although corruption was not factored into the study, the results indicated that children in poor areas were most affected, and corruption is associated with poverty. Morse (2006), for example, in a study using all countries for which data were available, found a strong association between poverty, as measured by per capita GDP (purchasing power parity), and corruption, as measured by the CPI. The same study found an association between corruption and environmental sustainability, as measured by the Environmental Sustainability Index (ESI), with the most corrupt countries having the worst environments. The ESI is a composite measure that includes air pollution as a factor. Similar results were obtained by Damania et al. (2003), who found that corruption was associated with poor implementation of environmental policies.

Some researchers point to the so-called Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) (e.g., Shafik 1994). A Kuznets curve is an inverted U and was first used in the context of income inequality. As countries develop economically, income inequality first goes up; this because a few rich people (the Vanderbilts, the Carnegies, the Rockefellers, etc.) are able to become super-rich by paying subsistence wages to workers. However, after a point, income inequality falls because industries have to compete for workers and so pay workers higher wages.

The EKC is said to work in a similar way. As economies develop, environmental indicators (e.g., the ESI) suggest that the environment deteriorates—this is because, when people are poor, their major concern is becoming rich, not helping the environment. Once they are rich, however, they want clean air, clean water, pleasant gardens, and so forth. Moreover, because they are rich, they can afford these things. Indeed, this is the argument put forward by Lomborg (2001). He argues that most environmental legislation follows existing trends. London’s air, for example, was becoming cleaner before the UK’s Clean Air Act (1956). If the EKC holds true, then one might expect more people to die from poor environments as their economies grow richer. However, this would be at variance with evidence that corruption is most associated with poor countries (e.g., Morse 2006). The way out of this paradox is to see that the major killers worldwide are not the things that bother environmentalists—pesticides, greenhouse gases, a lack of biodiversity, and so on—as indicated, they are simply poor water and indoor smoke (Lomborg 2001). Furthermore, as indicated, corruption plausibly hinders access to clean water and better home ventilation.

4. Polity

Types of national governance vary. At one end of the scale, there are liberal democracies; at the other end, there are despotisms. In between, there are monarchies (absolute or constitutional) and theocracies. What countries say about themselves, however, is often misleading. Officially, North Korea, for example, is named the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. However, in practice, the country is a one-man communist dictatorship. Similarly, Iran enjoys universal suffrage for people aged 18 or older, so it could be viewed as a democratic republic; in reality, however, it is a theocracy. Sweden is technically a constitutional monarchy but has more in common with a liberal democracy than a monarchy. The important consideration is therefore not what countries call themselves or even what they technically are; it is how they are governed. Democracy as a political system is governed to the satisfaction of its citizens, at least theoretically, which should act as a check against corruption (Claassen and Magalhães 2022). However, the empirical evidence tells us a different story.

Democracy, as a governance system, remains at the apex across European countries in terms of public support (Claassen 2019). Still, some worrying signs are available across the EU in terms of the actual performance of democracy (Sitter and Elisabeth 2019). Across central and eastern Europe (CEE), these signs are also straightforward, and an increasing number of member states are moving towards a democratic recession (Cianetti et al. 2018; Dawson and Hanley 2016; Matthes 2016; Stanley 2019). Even satisfaction with the democratic system has declined rapidly in Australia, reaching the lowest level recorded in 2019 since the 1970s. There is now evidence of widespread dissatisfaction among Australian citizens, who used to be the most satisfied supporters of democracy in the world (Cameron 2020).

Hungary, as another noteworthy example, became the first EU Member State in 2020 to have an electorally authoritarian regime, according to the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset (Lührmann et al. 2020). In 2015, Poland “embarked on a program of illiberal reforms that rivaled Fidesz for ambition and led to a decline in the quality of democracy swifter and steeper than that observed in Hungary” after the Law and Justice Party (PiS) returned to power (Stanley 2019, p. 349). Hence, both countries are now more or less perceived as cases of “intentional subversion and capture of liberal democratic institutions” (Stanley 2019, p. 351). Hanley and Vachudova (2018) further suggest that the Czech Republic is slowly turning into what they refer to as a populist democracy with a government coalition led by ANO and Prime Minister Andrej Babiš. This is a remarkable failure of democracy in a region previously considered as constituting a democratic success story (Cianetti et al. 2018). Across several central and eastern European Member States of the European Union, the democratic performance is also declining (Karv 2022). These empirical testimonies encourage us to connect polity and governance directly through corruption. To make the discussion more focused, we provide some details on different elements of polity and culture below, which, to our belief, maintain a connection with the governance system of a country.

4.1. Elements of Polity

There are three main elements of polity, e.g., separation of powers, rule of law, and democracy versus statism.

4.1.1. Separation of Powers

The notion of separation of powers holds that no single body can control a nation. It is mostly associated with the French philosopher Baron de Montesquieu (1689–1755). In Montesquieu’s version, government was separated into the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary. The legislature makes laws, the executive is the leadership that suggests them, and the judiciary enforces them. Each of these bodies is independent and therefore cannot interfere with the day-to-day working of the other. Thus, for instance, although the legislature makes laws, it cannot interfere with the workings of any court case; that is the job of the judiciary alone. Montesquieu’s works were particularly influential in the USA, where the principle of the separation of powers was written into the constitution. By contrast, countries in which there is no separation of powers tend to be despotisms—Zimbabwe, for instance, or North Korea.

The theory of parliamentary government in Britain and France is characterized by harmony between the legislature and government. The demand for establishing this harmony, combined with the progressive movement in the United States, was accompanied by a new “separation of powers” with the meaning that the political branches of government should be independent of the bureaucracy. In an age stressed by unity and cohesion, the difference between politics and administration was paradoxically driven by introducing a new chapter in the establishment of semi-autonomous branches of government. The extreme forms of the doctrine of the separation of powers as characterized in the Constitution of France in 1791 or in the Constitution of Pennsylvania in 1776 (Vile 1998) have already lost their credibility and were further undermined by the new approaches to the study of politics that characterized the twentieth century.

4.1.2. Rule of Law

The phrase rule of law pertains to the principle that all people within a nation are subject to the same laws. It addresses the exercise of power by public servants and the relationship between citizens and the state. Rule of law is non-arbitrary governance as opposed to one based on the power and whim of an absolute ruler (United Nations 2013). This is in contrast to nations in which some people (aristocrats) are not subject to them. Lack of rule of law thus tends to be associated with despotism. Rule of law, by contrast, is associated with liberal democracies. Measures of democracy frequently incorporate elements of both the rule of law and corruption (Bollen 1993). For instance, in calculating its political rights index, one of the 10 questions Freedom House uses is whether the government is free from pervasive corruption, while another question asks about the accountability of the government to the electorate between elections and whether it acts with transparency and openness. In fact, this index even incorporates the Corruption Perception Index of Transparency International. In a similar manner, the Polity IV scale of democracy includes the existence of institutionalized constraints on the exercise of power by the executive in addition to its other components (Marshall 2014). Boix et al. (2012) incorporate electoral fraud (a form of corruption) as a measure of democracy, while Welzel and Inglehart (2006) and Tamanaha (2004) propose to use either the Corruption Perception Index of Transparency International or the Control of Corruption index of WGI. Understandably, the latter employs corruption as a proxy measure for the rule of law (Knutsen 2010).

The World Justice Project (2021) states four pillars for the rule of law in a democratic state. The law should be clear and without ambiguity. It has to be published, and citizens should be informed about its adoption by the parliament. The law should be stable and applied without any discrimination. Corruption can distort the nature of the law so that the law becomes an effective tool for protecting authoritarianism and enriches a dictatorship so it can exercise arbitrary power. The extreme version of the situation is called the rule by law instead of the rule of law (Tamanaha 2004). Rule by law is a reflection of the debasement of the doctrine of legality. For example, some Asian countries classified as authoritarian regimes have not yet prohibited capital punishment, and the cruel punishment is still carried out in accordance with the law. Children who committed a serious crime under 18 years old were convicted of execution, and waited for capital punishment when they reached 18 based on the law (Death Penalty Information Center 2021). As far as Asian countries are concerned, the World Justice Project on Rule of Law survey conducted in 2012 has shown that the majority of Asia and Pacific countries are in the below 20 categories for rule of law practices, except for countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, and Singapore (World Justice Project 2021).

The situation is vague in some cases. In the late 18th century, the USA, for example, could be viewed as lacking rule of law, for black people and Native Americans were treated in different ways from those of white people. Black people could be kept as slaves in many states, and Native Americans could be forced to live on reservations. The rule of law in the USA applied only to white people. The rule of law, technically, does not mention what the laws are. Thus, in a technical sense, nations with cruel laws could still abide by the rule of law. For this reason, the notion of rule of law is sometimes expanded to include notions of human rights, including freedom from slavery, for example.

4.1.3. Democracy versus Statism

Democracies are characterized by two main features: they allow freedom of speech, and ordinary people can get rid of their rulers peacefully by voting them out of office at an election. These features were discussed at length by the 20th century philosopher Karl Popper in The Open Society and its Enemies.

Although many people view the function of elections as forcing politicians to obey the will of the people, Popper’s point was that this is not their primary function; instead, it is to provide the only viable means of peacefully keeping politicians in check. Notice that if one is to hold elections, it is vital to allow people to freely express their views. In practice, however, there are limitations to freedom of speech; democracies do not allow people to incite murder or other crimes, for instance.

Statism, in contrast to democracy, allows the government to control the people entirely. In China during the rule of Mao Zedong, for instance, the government told ordinary people where they should live, what work they should do, what food they should eat, and even what clothes they should wear, and if the people refused, they were severely punished (see, e.g., Chang and Halliday 2005).

When Popper was writing The Open Society and its Enemies (the 1940s) and through 1980, it was plausible that statism was entirely “bad”—there were the examples of Hitler’s Germany, Stalin’s Soviet Union, Pol Pot’s Cambodia, Mao Zedong’s China, and so forth. However, the situation today is unclear. China today is essentially a state-led enterprise, in which it is often impossible to determine whether a company is state owned or privately owned, and, even if privately owned, whether its owners are only following the diktats of the state (Moyo 2012). Yet China is fast becoming the richest country in the world (in terms of GDP) and has made enormous strides in improving the wealth of her people (e.g., Moyo 2012). Moreover, China’s statism, in that she is now a neo-colonial power, appears to be helping poor countries, particularly those in Africa (Moyo 2010, 2012), through foreign direct investment. Furthermore, as Moyo (2012) observes, China appears much better prepared to face future global shortages in commodities and is, indeed, unlike countries in the West, planning for them effectively. In doing this, as Moyo also observes, China is “breaking the rules” of ordinary commerce; she often, for example, pays far more than the fair price for a given commodity or resource. China is also highly corrupt (2012 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI): 3.9 which in 2019 is 4.1). Statism and corruption may work “for the good” (cf. the wasta, below). Present day China has an antecedent in, ironically, 19th century USA After the Civil War the country was ruled in effect by the Robber Barons—most notably by Cornelius Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Mellon. These men built the USA’s infrastructure and ruled ruthlessly by diktat (e.g., Galbraith 1979). For poor countries wishing to become rich, it is possible that benevolent dictatorships are more important than rule of law, separation of powers, and democracy. Democracy may be a luxury of the rich.

Democracy is also associated with two mutually exclusive concepts, egalitarianism and libertarianism. Egalitarianism is associated with the view that all people are equal and should therefore be treated the same; libertarianism is associated with the view that people should be allowed to say and do what they please, provided they do not harm other people. The key to libertarianism (and democracy) is the right to private property (e.g., Moyo 2012; Friedman and Friedman 1980). Libertarianism is most associated with the works of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman.

A problem is that a high degree of libertarianism allows for great inequality—some people will inevitably become richer than others, for instance. Thus, in the USA during the 19th century, John D. Rockefeller amassed a personal fortune of over US $300 billion (2007 value) at a time when most US citizens lived in poverty. As a result of such problems, liberal democracies today tend to combine a degree of egalitarianism with a degree of libertarianism. How much emphasis they place on each, however, varies. Related to this, egalitarianism implies transparency—the idea that neither governments nor corporations should have secrets. That some secrets should be kept secret is undeniable—when at war, for example, countries should not divulge their plans to their enemies, and it would likewise be insane for corporations to inform their rivals of potential new products. The question at hand concerns how transparent a country or corporation should be. Too little transparency may foster corruption; too much may foster chaos.

4.2. Culture

A nation’s culture affects how it is ruled. In the Arab Gulf states, for instance, the majority of people are Muslim; therefore, national laws within the states are biased towards Islam. Indeed, the constitutions of all six states demand that the rulers encourage Islamic practice—caring for the elderly, for instance, and providing religious solace for those in hospitals.

There are cultural differences between nations other than religion. Most people in the Middle East and North Africa, for example, are aware of the wasta. The wasta goes back to times when societies were tribal and family loyalties were strong. This translated to helping family and friends in times of trouble and repaying favors. Today, however, wasta often translates to bribing people for jobs and other advantages in life. It has thus outlived its usefulness and can be viewed as corruption (Cunningham and Sarayrah 1993).

Another example concerns US gun laws. The USA, unlike most developed countries, allows private citizens to carry guns. As a result, many believe, the intentional homicide in the country is high (4.7 per 100,000 people). For comparison, in developed countries where there is no gun culture, the murder rates tend to be low (in Hong Kong, for instance, it is a mere 0.2 per 100,000 people); even in the UK, which has higher overall crime rates than the USA (Civitas 2012), the murder rate is less than half that of the USA. The UK, the USA, and Hong Kong, incidentally, are ranked as approximately the same in terms of corruption (respective CPIs, 2012: 7.4., 7.3., and 7.7, which is in CPIs, 2019 For UK, USA and Hong Kong: 7.7, 6.9 and 7.6). So, crime, although linked with corruption, may also depend on cultural factors.

5. Discussion

Corruption affects almost every aspect of national life. It makes people poorer; it makes goods and services more expensive and of lower quality; it leads to violence, including war; and it makes people less healthy. It may be the number one problem in poor countries. Corruption is a very common result of poor governance, which is characterized by a lack of accountability, transparency, efficiency, and citizen participation (Ciccone et al. 2014). Various causes of corruption have been identified in studies (e.g., Enste and Heldman 2017), including democracy and the political system, the size and structure of governments, economic freedom and openness of the economy, the quality of institutions, press freedom, the judiciary, civil service salaries, the percentage of women in the labor force and in parliament, cultural determinants, colonial heritage, and natural resource endowment. Enste and Heldman (2017) also identify the impact of corruption on investments in general, foreign direct investments and capital inflows, official growth, foreign trade and aid, government expenditure and services, inequality, the shadow economy, and crime.

Monopoly power plus discretion by officials minus accountability equals corruption (Klitgaard et al. 2000). It weakens trust in institutions (both public and private) and accelerates tolerance for offering and accepting bribes in public institutions (Habibov et al. 2017). People use corruption as one of the most important aspects of government performance “to judge political institutions” (Anderson and Tverdova 2003, p. 104). The negative impacts of corruption diminish for both local and national governments as political situations improve (Habibov et al. 2019). Corruption and the corrupt are both evil; the good acts make good polity possible. Corruption is legibly linked to lessening government support in well-established democracies (Bailey and Paras 2006; Wagner et al. 2009). Evidence shows that incidents of corruption have led to the failure of governments in several established democracies (Holmes 2006). We find that corruption and polity affect governance in a particular regime, irrespective of the political systems, which require added attention to deal with the governance system effectively.

There is enough empirical evidence reporting the kinds of governments and the kinds of institutions (public, private, or non-profit) susceptible to corruption. Corruption can be reduced by separating powers, ensuring transparency, establishing checks and balances, implementing a good justice system, and clearly defining roles, responsibilities, rules, and limits. Corruption should be welcomed to the extent it provides a useful way of lessening the distortions produced by ineffective bureaucratic procedures (Habibov et al. 2017). Good governance is associated with the rule of law, separation of powers, and democracy. Although no country is perfect and legislatures must decide the trade-off between libertarianism and egalitarianism, it is common sense and common knowledge that countries vary vastly in how good their governance is. Cultural factors may also be relevant, and culture can sometimes be difficult to change. A summary of the issues we covered in this study is highlighted in Table 1 below. It reflects a lack of research evidence in the field of polity and its impact on governance, along with the interplay between corruption and polity. Finding this to be a potential gap in the literature, we attempt to draw a link between corruption and governance, polity and governance, and an interaction between corruption and polity to strengthen governance thinking. More empirical studies are warranted to address the unaddressed issues in the existing literature, which may generate new dimensions and knowledge in understanding governance. Considering there are so many studies on corporate governance, we are focusing on governance at the national level.

Table 1.

Summary of the study.

This study adds to the knowledge of regulators and policymakers, who can use it to develop laws, guidelines, and directives at the macro level and to develop various guidelines, directives, rules, and regulations for firms in their countries. The way regulators follow this is still under debate and requires overhaul (Nguyen and Dang 2022). They failed to create a favorable environment for these firms as they paid very little attention to enhancing the quality of various institutions responsible for maintaining good governance. The policy implications of our research show that regulators need to focus on improving the quality of the country’s institutions and should pay more attention to this area.

6. Conclusions

Good governance is associated with less corruption, and poor governance is associated with more corruption. Poor governance is defined by poor rule of law, lack of freedom of speech, limited to non-existent press freedom, a subverted judiciary, rigged or non-existent general elections, and ruling elites unaccountable to the people. Corruption appears to both facilitate and be caused by poor governance. The scale of corruption worldwide is enormous, though it appears to be largest in poor countries. Its effects include the impoverishment of people, warfare and other forms of violence, and poorer health services. Corruption may also directly or indirectly damage the environment. Polity also has some contribution in defining corruption and governance.

This study employs a qualitative investigation into the possible relationship between corruption, politics, and good governance. At the same time, it also highlights the collective impact of corruption and polity on governance. The study uses a theory synthesis approach based on selective literature to bring new debate to the governance–corruption–polity triad. The study concludes that corruption and polity impact governance individually and collectively. As the paper is conceptual, it is driven by the core tenet of joining selected key themes. The quantitative validity is left for further exploration. Corruption may be tailored with reference to measurement items based on the polity in a selected country. Polity may also moderate the relationship between corruption and governance. Further research may also take the form of a qualitative inquiry based on an in-depth interview or any other data collection methods under the qualitative research paradigm.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.S.A.-F.; methodology, M.A.S.A.-F. and N.C.S.; software, M.A.S.A.-F.; validation, M.A.S.A.-F. and N.C.S.; formal analysis, M.A.S.A.-F.; investigation, M.A.S.A.-F.; resources, M.A.S.A.-F. and N.C.S.; data curation, M.A.S.A.-F.; writing—original draft, M.A.S.A.-F.; writing—review and editing, M.A.S.A.-F. and N.C.S.; visualization, M.A.S.A.-F. and N.C.S.; supervision, M.A.S.A.-F.; project administration, M.A.S.A.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

In this study, no new data were created or analyzed. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor and the reviewers for the helpful comments and suggestions that significantly enhanced this work. The usual disclaimer applies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Faryan, Mamdouh Abdulaziz Saleh, and Nikhil Chandra Shil. 2022. Nexus between Governance and Economic Growth: Learning from Saudi Arabia. Cogent Business & Management 9: 2130157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Faryan, Mamdouh Abdulaziz Saleh. 2022. Nexus between corruption, market capitalization, exports, FDI, and country’s wealth: A pre-global financial crisis study. Problems and Perspectives in Management 20: 224–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Christopher J., and Yuliya V. Tverdova. 2003. Corruption, Political Allegiances, and Attitudes toward Government in Contemporary Democracies. American Journal of Political Science 47: 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvin, Mark B., Rudra P. Pradhan, and Mahendhiran S. Nair. 2021. Are there links between institutional quality, government expenditure, tax revenue and economic growth? Evidence from low-income and lower middle-income countries. Economic Analysis and Policy 70: 468–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, John, and Pablo Paras. 2006. Perceptions and Attitudes about Corruption and Democracy in Mexico. Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 22: 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, Roy F., and Mark R. Leary. 1997. Writing narrative literature reviews. Review of General Psychology 1: 311–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. 2010. Bob, Band Aid and How the Rebels Bought Their Arms, World Service. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/theeditors/2010/03/ethiopia.html (accessed on 23 January 2018).

- Bernauer, Thomas, and Vally Koubi. 2009. Effects of political institutions on air quality. Ecological Economics 68: 1355–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, Timothy, and Torsten Persson. 2011. The logic of political violence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126: 1411–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundo, Giorgio, Jean-Pierre Olivier de Sardan, N. Bako Arifari, and M. Tidjani Alou. 2006. Everyday Corruption and the State: Citizens and Public Officials in Africa. London: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Boix, Carles, Michael Miller, and Sebastian Rosato. 2012. A Complete Data Set of Political Regimes, 1800–2007. Comparative Political Studies 46: 1523–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, Kenneth. 1993. Liberal Democracy: Validity and Method Factors in Cross-National Measures. American Journal of Political Science 37: 1207–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, Christopher, and Richard North. 2005. The Great Deception: Can the European Union Survive? London: Continuum International Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Sarah. 2020. Government performance and dissatisfaction with democracy in Australia. Australian Journal of Political Science 55: 170–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Jung, and Jon Halliday. 2005. Mao: The Unknown Story. London: Jonathan Cape. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet, Lisa, and Paul Collier. 2004. Development Effectiveness in Fragile States: Spillovers and Turnarounds. Oxford: Centre for the Study of African Economies, Department of Economics, Oxford University (Mimeo). [Google Scholar]

- Chevigny, Paul. 1995. Edge of the Knife: Police Violence in the Americas. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cianetti, Licia, James Dawson, and Sean Hanley. 2018. Rethinking “Democratic Backsliding” in Central and Eastern Europe—Looking Beyond Hungary and Poland. East European Politics 34: 243–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccone, Dana Karen, Taryn Vian, Lydia Maurer, and Elizabeth H Bradley. 2014. Linking governance mechanisms to health outcomes: A review of the literature in low-and middle-income countries. Social Science & Medicine 1: 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Civitas. 2012. Comparisons of Crime in OECD Countries. Available online: http://www.civitas.org.uk/archive/crime/crime_stats_oecdjan2012.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2018).

- Claassen, Christopher. 2019. Does Public Support Help Democracy Survive? American Journal of Political Science 64: 118–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassen, Christopher, and Pedro C. Magalhães. 2022. Effective Government and Evaluations of Democracy. Comparative Political Studies 55: 869–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, David, and Matthew Elliot. 2009. The Great European Rip-Off: How the Corrupt, Wasteful EU Is Taking Control of Our Lives. London: Arrow. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, Robert B., and Yasin K. Sarayrah. 1993. Wasta: The Hidden Force in Middle Eastern Society. Westport: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Damania, Richard, Per G. Fredriksson, and John A. List. 2003. Trade liberalization, corruption, and environmental policy formation: Theory and evidence. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 46: 490–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Van Cuong, Quang Khai Nguyen, and Xuan Hang Tran. 2022. Corruption, institutional quality and shadow economy in Asian countries. Applied Economics Letters, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, Gouranga Gopal, and Soamiely Andriamananjara. 2006. Hub-and-spokes free trade agreements in the presence of technology spillovers: An application to the western hemisphere. Review of World Economics 142: 33–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, James, and Sean Hanley. 2016. What’s Wrong with East-Central Europe? The Fading Mirage of the ‘Liberal Consensus’. Journal of Democracy 27: 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Death Penalty Information Center. 2021. Executions Around the World. 2021. Available online: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/policy-issues/international/executions-around-the-world (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Enste, Dominik H., and Christina Heldman. 2017. Causes and Consequences of Corruption: An Overview of Empirical Results. IW-Report, No. 2/2017. Köln: Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft (IW). Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/157204 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- European Commission. 2014. Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament: EU anti-Corruption Report, 2014, p. 3. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/e-library/documents/policies/organized-crime-and-human-trafficking/corruption/docs/acr_2014_en.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- Fink, Arlene. 2014. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, Uwe. 2018. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Milton, and Rose Friedman. 1980. Free to Choose: A Personal Statement. Penguin: Harmondsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, John Kenneth. 1979. The Age of Uncertainty. A History of Economic Ideas and Their Consequences. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Gberie, Lansana. 2005. A Dirty War in West Africa: The RUF and the Destruction of Sierra Leone. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Habibov, Nazim, Elvin Afandi, and Alex Cheung. 2017. Sand or Grease? Corruption–Institutional Trust Nexus in post-Soviet Countries. Journal of Eurasian Studies 8: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibov, Nazim, Lida Fan, and Alena Auchynnikava. 2019. The Effects of Corruption on Satisfaction with Local and National Governments. Does Corruption ‘Grease the Wheels’? Europe-Asia Studies 71: 736–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, Sean, and Milada Anna Vachudova. 2018. Understanding the Illiberal Turn: Democratic Backsliding in the Czech Republic. East European Politics 34: 276–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoon, D., and F. Heinrich. 2013. Global Corruption Barometer. London: Transparency International UK. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/gcb2013 (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Hawthorne, O. E. 2013. Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index: Best Flawed Measure on Corruption? Paper presented at the 3rd Global Conference on Transparency Research, HEC Paris, Paris, France, October 24–26; Available online: http://campus.hec.fr/global-transparency/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Hawthorne-HEC.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2014).

- Holmes, Leslie. 2006. Rotten States? Corruption, Post-Communism, and Neoliberalism. Durham: Duke University Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- Iglehart, John K. 2009. Finding money for health care reform—Rooting out waste, fraud, and abuse. The New England Journal of Medicine 361: 229–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IMF. 2005. The IMF’s Approach to Promoting Good Governance and Combatting Corruption: A Guide. Available online: www.imf.org/external/np/gov/guide/eng/index.htm (accessed on 15 November 2017).

- Ivanyna, Maksym, and Anwar Shah. 2014. How Close is Your Government to Its People? Worldwide Indicators on Localization and Decentralization. Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal 8: 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, Elina. 2020. Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. AMS Review 10: 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, Seema. 2009. Air quality and early-life mortality: Evidence from Indonesia’s wildfires. The Journal of Human Resources 44: 916–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, Michael, and Sahr J. Kpundeh. 2004. Building a Clean Machine: Anti-Corruption Coalitions and Sustainable Reforms. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3466: 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Karv, Thomas. 2022. Does the democratic performance really matter for regime support? Evidence from the post-communist Member States of the European Union. East European Politics 38: 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Pablo Zoido-Lobatan. 1999. Governance Matters. Policy Research Working Paper No. 2196. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2010. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues. Draft Policy Research Working Paper. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, and Aart Kraay. 2002. Growth Without Governance. Policy Research Working Paper No. 2928. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Klitgaard, Robert E., Ronald MacLean-Abaroa, and H. Lindsey Parris. 2000. Corrupt Cities: A Practical Guide to Cure and Prevention. Oakland: ICS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knutsen, Carl Henrik. 2010. Measuring Effective Democracy. International Political Science Review 31: 109–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, Marcus J., and Andrew Schrank. 2007. Growth and governance: Models, measures and mechanisms. Journal of Politics 69: 538–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Billon, Philippe. 2003. Buying peace or fuelling war: The role of corruption in armed conflicts. Journal of International Development 15: 413–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomborg, Bjorn. 2001. The Skeptical Environmentalist: Measuring the Real State of the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lührmann, Anna, Seraphine F. Maerz, Sandra Grahn, Nazifa Alizada, Lisa Gastaldi, Sebastian Hellmeier, Garry Hindle, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2020. Autocratization Surges—Resistance Grows, Democracy Report 2020. Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem), University of Gothenburg. Available online: https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/51/43/51434648-2383-4569-84d0-e02fbd834b3e/v-dem_democracyreport2020_20-03-18_final_lowres.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2022).

- Marshall, Monty G. 2014. Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800–2013. Available online: https://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Marshall, Monty G., and Benjamin R. Cole. 2011. Conflict, Governance, and State Fragility. Vienna: Center for Systemic Peace. Available online: http://www.systemicpeace.org/vlibrary/GlobalReport2011.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2017).

- Matthes, Claudia-Yvette. 2016. Comparative Assessments of the State of Democracy in East-Central Europe and its Anchoring in Society. Problems of Post-Communism 63: 323–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, Maggie A., and Menachem Elimelech. 2007. Water and sanitation in developing countries: Including health in the equation. Environmental Science & Technology 41: 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Mick. 1993. Declining to Learn from the East? The World Bank on Governance and Development. IDS Bulletin 24: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, Stephen. 2006. Is corruption bad for environmental sustainability? A cross-national analysis. Ecology and Society 11: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, Dambisa. 2009. Why foreign aid is hurting Africa. The Wall Street Journal. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB123758895999200083 (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Moyo, Dambisa. 2010. Dead Aid: Why Aid is not Working and How There is Another Way for Africa. Penguin: Harmondsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, Dambisa. 2012. Winner Take All: China’s Race for Resources and What it Means for the World. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mungiu-Pippidi, A. 2015. The Quest for Good Governance: How Societies Develop Control of Corruption. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina, Ramin Dadasov, Martinez B. Roberto, K. Natalia Alvarado, Victoria Dykes, Niklas Kossow, and Aram Khaghaghordyan. 2017. Index of Public Integrity. European Research Centre for Anti-Corruption and State-Building. Available online: http://www.integrity-index.org (accessed on 19 May 2019).

- Neumayer, Eric. 2002. Do democracies exhibit stronger international environmental commitment? A cross-country analysis. Journal of Peace Research 39: 139–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Quang Khai, and Van Cuong Dang. 2022. Does the country’s institutional quality enhance the role of risk governance in preventing bank risk? Applied Economics Letters, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, Douglass C. 1991. Institutions. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 5: 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, Douglass C., John Joseph Wallis, and Barry R. Weingast. 2009. Violence and the Rise of Open-Access Orders. Journal of Democracy 20: 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, Nathan, and Nancy Qian. 2012. Aiding Conflict: The Impact of U.S. Food aid on Civil War. NBER Working Paper No. 17794. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w17794 (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Ogundajo, Grace Oyeyemi, Rufus Ishola Akintoye, Oluwatobi Abiola, Ayodeji Ajibade, Moses Ifayemi Olayinka, and Abolade Akintola. 2022. Influence of country governance factors and national culture on corporate sustainability practice: An inter-Country study. Cogent Business & Management 9: 2130149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier de Sardan, J. P. 1999. A moral economy of corruption in Africa? The Journal of Modern African Studies 37: 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olken, Benjamin A., and Rohini Pande. 2012. Corruption in Developing Countries. Annual Review of Economics 4: 479–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispel, Laetitia C., Pieter de Jager, and Sharon Fonn. 2016. Exploring corruption in the South African health sector. Health Policy and Planning 31: 239–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrick, Dani, and Arvind Subramanian. 2003. The primacy of institutions (and what this does and does not mean). Finance and Development 40: 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Ackerman, Susan. 2017. What Does ‘Governance’ Mean? Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions 30: 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, Bo. 2011. The Quality of Government: Corruption, Social Trust, and Inequality in International Perspective. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, Bo, and Aiysha Varraich. 2009. Making Sense of Corruption. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, Bo, and Jan Teorell. 2008. What is Quality of Government: A Theory of Impartial Political Institutions. Governance: An International Journal of Policy and Administration, and Institutions 21: 165–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihu, Habeeb Abdulrauf. 2022. Corruption: An impediment to good governance. Journal of Financial Crime 29: 101–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafik, Nemat. 1994. Economic development and environmental quality: An econometric analysis. Oxford Economic Papers 46: 757–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitter, Nick, and Bakke Elisabeth. 2019. Democratic Backsliding in the European Union. Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Politics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, Ben. 2019. Backsliding Away? The Quality of Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Contemporary European Research 15: 343–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamanaha, Brian Z. 2004. On the Rule of Law—History, Politics, Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Transparency International. 2019. What Is Corruption? Available online: https://www.transparency.org/what-is-corruption (accessed on 25 May 2017).

- United Nations. 2013. What Is ‘Rule of Law’. Available online: http://www.unrol.org/article.aspx?article_id=3 (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Vile, Maurice John Crawley. 1998. Constitutionalism and the Separation of Powers, 2nd ed. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Alexander F., Friedrich Schneider, and Martin Halla. 2009. The Quality of Institutions and Satisfaction with Democracy in Western Europe―A Panel Analysis. European Journal of Political Economy 25: 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welzel, Christian, and Ronald Inglehart. 2006. Emancipative Values and Democracy: Response to Hadenius and Teorell. Studies in Comparative International Development 41: 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, Paul G. 2022. International validation of the Corruption Perceptions Index: Implications for business ethics and entrepreneurship education. Journal of Business Ethics 35: 177–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2013. The Costs of Corruption. Available online: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/NEWS/0,,contentMDK:20190187~menuPK:34457~pagePK:34370~piPK:34424~theSitePK:4607,00.html (accessed on 23 January 2015).

- World Health Organization. 2017. Diarrhoeal Disease. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs330/en (accessed on 25 May 2019).

- World Justice Project. 2021. What Is the Rule of Law? Available online: https://worldjusticeproject.org/about-us/overview/what-rule-law (accessed on 28 January 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).