1. Introduction

In an increasingly globalized environment, exportation plays a vital role in the strategies embraced by Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) (

Golovko and Valentini 2011). The decision to export is a simple form of internationalization that fits into international marketing strategies, widely adopted by SMEs (

Morgan et al. 2012). However, several barriers discourage SMEs from entering or expanding their export activities in international markets, especially when firms are located in emerging markets (

Safari and Saleh 2020). In order to achieve competitiveness in international contexts, SMEs need to develop, on one hand, specific and unique assets that arise from distinctive resources and capabilities (a strategy rooted in a resource-based paradigm, which views firms as unique and heterogeneous collections of tangible and intangible resources) (

Barney 1991); on the other hand, with those resources, firms must manage to craft competitive strategies that enable them to cope with competitive markets, taking advantage of profits and a sustainable market strategy, in order to increase their export performance (

Aulakh et al. 2000;

Martin et al. 2017;

Morgan et al. 2004;

Porter 1985;

Zehir et al. 2015).

In competitive markets, positional advantage reflects the firm’s positioning in providing competitive products and services vis-à-vis its competitors (

Porter 1985). However, the firm’s positional advantage is the result of the implementation of competitive strategic plans that have an impact on export performance. Moreover, competitive strategies impact export performance through the firm’s positional advantage (

Keskin et al. 2021;

Lado et al. 2004;

Martin et al. 2017;

Morgan et al. 2004).

The literature suggests that export performance is strongly related to firms’ strategic competitive or positional market choices (

Morgan et al. 2004). Moreover, it is the firm and industry characteristics, and the firm’s adopted strategies that help explain the firm’s export performance in emerging markets, i.e., competitive strategies positively affect the firms’ export performance (

Aulakh et al. 2000;

Lado et al. 2004).

Although there are several studies in the literature that investigate the relationship between the differentiation strategy and export performance (

Aulakh et al. 2000;

Crespo et al. 2020;

Furrer et al. 2008;

Morgan et al. 2004), this study is original; it highlights, on one hand, the effect of differentiation strategies on the export performance of SMEs and, on the other hand, determines the role of the mediating effect of positional advantage on this relationship (differentiation strategy–export performance) in the context of emerging countries, more particularly in Mozambique.

Although the study of competitive strategies is not new (

Crespo et al. 2020;

Furrer et al. 2008;

Morgan et al. 2004), its application in emerging countries, where SMEs have few resources and the competitive context is very peculiar, is little studied (

Aulakh et al. 2000). For example, although the SMEs located in the sub-Saharan region, particularly in Mozambique, contribute to the increase in employment and Gross Domestic Product (GDP), they are affected by several obstacles; these include as poor financing, low technological intensity, the low qualification of human resources, resources, regulatory barriers, the tax burden, the high cost of procedures, and poor market access. These obstacles weaken these companies in building up their competitiveness and their performance indicators, exposing them to weaknesses in highly competitive markets. Moreover, a weak adoption of competitive strategies to increase their performance is noted (

Ministério da Indústria e Comércio 2016;

Safari and Saleh 2020).

Taking into account the characteristics of Mozambique, an emerging country with SMEs looking to expand their markets abroad, but suffering from a lack of resources and contextual obstacles, this paper aims to study how differentiation strategies support the export performance of Mozambican SMEs using the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm as a core basis.

The following differentiation strategies are going to be used in this paper as they are very important to Mozambican SMEs: (a) can hardly take full advantage of economies of scale (

Borch et al. 1999); and (b) can tailor their products and services to provide unique offerings and take full advantage of their positional advantages in international markets (

Zehir et al. 2015). As such, differentiation strategies that rest on valuable unique resources are not easily imitated by their competitors (

Banker et al. 2014). Furthermore, Mozambican SMEs are encouraged to use their potential to promote export activities (

Kaufmann 2020), and efforts to improve their Export Performance (EP) have thus become prominent in the area of export-related research (

Safari and Saleh 2020). We also argue that differentiation strategies provide important competitive advantages to internationalizing SMEs (

Knight et al. 2020), and that positional advantages directly affect export venture performance; this is because the relative superiority of a venture’s value offering determines the buying behavior of the target customers and the outcomes of this behavior for the firm in its foreign market (

Morgan et al. 2004). In this sense, this paper focuses on analyzing the following in a particular case of an emerging market in Mozambique: (a) the importance of differentiation strategies on export performance; (b) the importance of positional advantage on export performance; and (c) how the positional advantage mediates the relationship between competitive differentiation strategies and the export performance of SMEs.

In theoretical terms, this study contributes to the development of International Marketing theory, with emphasis on the importance of positional advantage in exporting SMEs in emerging countries. In practical terms, this study reinforces the urgency in the adoption of competitive strategies by SMEs as a way to survive in increasingly competitive markets.

After this introduction, this paper begins by presenting the theoretical development, based on the existing literature, and develops the research hypotheses. Second, the research methodology is identified, specifying the variables measured and the procedures adopted in data collection. The third section discusses the results, as well as their implications. Finally, the last section contains the conclusions, limitations, and future research.

2. Theory and Hypotheses Development

Competitive strategies play a vital role in competing successfully in the market, as they enable firms to search for a beneficial competitive position, and ensure profit and business sustainability in a particular industry (

Porter 1985). A firm’s ability to make rapid and adequate progress is based on a competitive strategy that underpins the firm’s strategic moves in achieving superior competitiveness and export performance (

Furrer et al. 2008).

The RBV is one of the theoretical foundations of strategic management as it is widely used in the strategic management literature (

Barney 1991;

Brouthers and Xu 2002;

Yeniaras et al. 2017). According to

Barney (

1991), resources are a set of assets and capabilities controlled by firms that enable them to implement unique strategies. Based on the RBV, companies’ resources and capabilities are the sources of sustained competitive advantage (

Barney 1991); they enable firms to combine unique resources and capabilities to tailor their products and services to the needs of the customers in order to anticipate contextual changes and to achieve superior performance (

Brouthers et al. 2015). The RBV is of added value to this paper as it characterizes a company as a collection of resources and capabilities that enable firms to generate firm-specific differentiation strategies that are hard to imitate. Moreover, those unique resources and capabilities support firms when deploying their unique positional advantages, giving them an edge over competitors, and thus supporting competitive advantages and firm and export performance (

Yeniaras et al. 2017).

Companies located in developing countries are faced simultaneously with two challenges: on one hand, to overcome the obstacles they encounter in placing their products and services in the domestic market and, on the other hand, even more challenging, to export these products and services to foreign markets (

Aulakh et al. 2000). Therefore, the adoption of competitive strategies allows firms operating in emerging contexts to position and increase their export performance. The literature refers to three generic strategies (

Porter 1985): (a) cost leadership; (b) product and service differentiation; and (c) focus strategy. Each of them involves a fundamentally different path that converges on the chosen competitive advantage (

Porter 1985).

Cost leadership and differentiation strategies seek competitive advantage across a broad range of industry segments, while focus strategies aim for cost advantage (cost focus) or differentiation (differentiation focus) in a narrow segment. In the particular case of the differentiation strategy, companies seek to be unique in their industry in some dimensions that are widely valued by the market, i.e., they select one or more attributes considered important in their core business and position themselves to meet those market needs. The logic of the differentiation strategy requires firms to select attributes that are different and unique from their rival’s characteristics (

Porter 1985).

Export performance is a multifaceted concept and uses multiple indicators for its measurement (

Chen et al. 2016;

Ribau et al. 2017;

Sousa 2004). There has been a growing interest in export performance measurement scales, among which it is possible to highlight the inclusion of objective and subjective indicators, and the distinction between economic and strategic indicators.

Table 1 presents the distinction between objective and subjective indicators. Objective indicators concern financial ratios and economic and non-economic measures of export markets. Subjective indicators encompass management decisions and export expansion strategies, such as market indicators, competitiveness and technology intensity, performance objectives, and subjective generic measures (

Ribau et al. 2017). In this context, the approach of

Zou and Stan (

1998) is notable for its use of objective indicators, such as financial ratios, and subjective indicators, such as technological intensity and performance objectives that include export and consumer performance. Although

Aulakh et al. (

2000) do not distinguish indicators into objective and subjective, they consider sales growth, market share, competitive position, and profit as metrics of export performance.

Aulakh et al. (

2000) examine how firms’ export strategies (differentiation, cost leadership, marketing standardization, and export diversification) in emerging economies affect their export performance; this is measured using a four-item scale, assessing the overall role of exports in firms’ sales growth, market shares and competitive positions, and the profitability of export sales. The results suggest that the cost leadership strategy has a positive effect on export performance in developed country markets and the differentiation strategy is positively related to export performance in developing country markets.

Zou and Stan (

1998) analyze the determinants of export performance and conclude that export performance measures are grouped into seven categories, representing financial, non-financial, and composite scales. The ‘sales’ category includes measures of the absolute volume of export sales or export intensity. The ‘profit’ category consists of absolute measures of the overall export profitability and relative measures, such as export profit divided by total profit or domestic market profit. While performance measures in the ‘sales’ and ‘profit’ categories are static, the ‘growth’ measures refer to changes in export sales or profits over a period of time. In comparison to financial measures, which are more objective, non-financial measures of export performance are more subjective. The ‘success’ category comprises measures that include a manager’s belief that exporting contributes to a firm’s profit and overall reputation; ‘Satisfaction’ refers to a manager’s overall satisfaction with the firm’s export performance; and ‘goal achievement’ refers to a manager’s assessment of performance against set goals. Finally, ‘composite scales’ refer to measures based on the overall scores of several performance measures. This study concludes that export sales, profit, and composite scales are the most frequently used measures when aiming to measure export performance.

Sousa (

2004) analyzes the metrics used in export performance. He concludes that, although the number of different measures used in export performance is large, only a few are used frequently, such as export intensity (export to total sales ratio), export sales growth, export profit, export market share, satisfaction with overall export performance, and perceived export success. The indicators of export performance were classified into objective and subjective measures. Indicators that are mainly based on absolute values, such as export intensity, export sales volume, and export market share, among others, are referred to as objective measures. On the other hand, indicators that measure perceptual performance or attitude, such as perceived export success and satisfaction with export sales, are considered subjective performance measures.

According to

Verreynne and Meyer (

2011), the differentiation strategy is often associated with a high level of performance in SMEs and/or new ventures. On the other hand, innovative differentiation is significantly associated with performance, especially for firms operating in dynamic environments. Marketing differentiation has a positive relationship with performance in the case of firms operating in low-dynamic environments; this means that, for firms operating in less dynamic environments, there is only an indirect relationship between innovative differentiation and performance, which is mediated by marketing differentiation. In parallel, and although the effect of organic structures on innovative differentiation is significant in both low- and high-dynamic environments, it is only in dynamic environments that younger firms have a significant advantage in innovative differentiation.

For

Aulakh et al. (

2000), the differentiation strategy has strong effects on export performance in emerging country markets. Furthermore, a differentiation strategy is more effective for firms embedded in emerging economies within a group of countries that are at similar stages of economic development.

Felzensztein and Gimmon (

2014) analyze how firms operating in international food markets can improve their competitiveness and long-term profit under financial pressure. Although the results show that managers prefer to adopt a cost reduction competitive strategy rather than a differentiation strategy, the authors recommend adopting a differentiation strategy with special attention to emerging environmental attributes.

Crespo et al. (

2020) analyze the impact of differentiation and cost-based leadership strategies on internationalization performance, considering the contingency perspective (i.e., the duration and preparation for the internationalization of new ventures in Portugal). The results indicate that the differentiation strategy has a positive impact on the international performance of these firms. When examining the impact of firms’ cost-based leadership and differentiation strategies in Thailand,

Mongkol (

2021) concludes that the two strategies combined produce a superior positive impact on firm performance.

Hypothesis 1. Differentiation strategies have a direct positive effect on SMEs’ export performance.

Competitive advantage refers to the firm’s positional superiority in the market segment in which it operates. This superiority is based on delivering superior customer value and/or achieving lower costs compared to competitors (

Hooley and Greenley 2005). For

Martin et al. (

2017), a firm’s positional advantage is the result of the effort of competitive strategies based on product or service differentiation and cost leadership. According to

Porter (

1985), the cost of achieving a positional advantage can be affected by the competitive intensity of the context where the firm is located. On the other hand, in

Cavusgil and Zou’s (

1994) approach, the positional advantage of an exporting firm is related to the positions of its rivals and is directly and negatively impacted by the competitive intensity of the environment in which it operates.

By decomposing competitive advantage into cost-based leadership, differentiation strategies and positional advantage,

Martin et al. (

2017) argue that firms should focus on building marketing competencies that match the adopted cost-based leadership, their differentiation strategy, or their positional advantage, rather than focusing solely on marketing competencies. These firms need positional advantages to improve their export performance, which they only achieve by combining marketing competencies with a competitive strategy to generate a positional advantage.

Morgan et al. (

2004) argue that the performance of exporting firms is strongly related to their positional advantage in the market. Positional advantage, in turn, is directly related to the availability of resources and core competencies, and to cost-based leadership and differentiation strategic choices. Differentiation strategies are very important for SMEs as they can rarely take full advantage of economies of scale (

Borch et al. 1999). Moreover, differentiation strategies are normally based on the positional strategies of products and services, in order to provide unique offers and to serve the market more properly (

Zehir et al. 2015). It is the availability of resources that supports SMEs in their deployment of unique positional advantages, based on differentiation strategies, as SMEs are normally technology and capital-constrained (

Ju et al. 2017). As such, positional advantages are important for SMEs so that they avoid being dependent on low-cost strategies that limit their profit margins (

Ju et al. 2017). Differentiation strategies support companies to invest in deploying unique positional advantages that support product and service customization, and that are not easily imitated by their competitors (

Banker et al. 2014). Moreover, these positional advantages rest on valuable resources that lead to long-term competitive advantages and an enhanced performance (

Banker et al. 2014).

Based on firms’ competitive advantages,

Martin et al. (

2017) examine the interaction between firms’ marketing competencies, cost-based leadership and differentiation strategies, positional advantage, ambidextrous innovation, and export risk performance. One of the results their study found suggests that positional advantage mediates the relationship between the differentiation strategy and export performance.

Keskin et al. (

2021) suggest that cost-based leadership and differentiation strategies can achieve higher export performance in foreign markets through competitive advantage. Export intensity and the level of internationalization increases as a result of positional advantages, supported by differentiation-based strategies (

Lado et al. 2004). Based on the unique positional advantages that are needed to deploy differentiation strategies, it is expected that the direct relationship between the differentiation strategy and export performance could be complemented by the positional advantages SMEs have (

Aguinis et al. 2017). Therefore, we consider the following research hypotheses in this study:

Hypothesis 2. Differentiation strategy has a positive impact on the positional advantage of SMEs.

Hypothesis 3. Positional advantage has a positive impact on the export performance of SMEs.

Hypothesis 4. Positional advantage positively mediates the relationship between the differentiation strategy and the SMEs’ export performance.

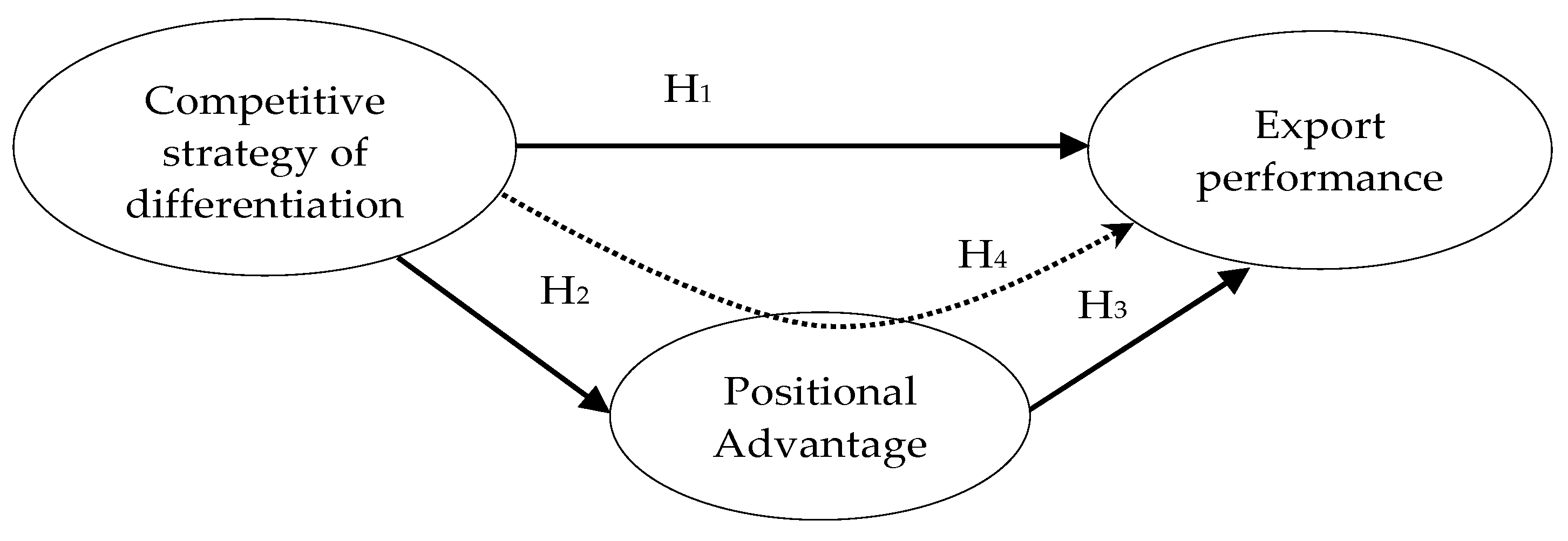

Conceptual Model

The proposed conceptual model is presented in

Figure 1. This model suggests that the differentiation strategy has a direct positive relationship with the export performance of SMEs. Furthermore, the positional advantage mediates the relationship between differentiation competitive strategies and export performance, which means that consolidating the positional advantage of exporting firms enables them to increase their export performance.

4. Results and Discussion

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 present the loadings of the items obtained through bootstrapping with 5000 replications. Items EP3, SD1, SD5, APRD3, ASERV1 and ASERV3 were removed because they presented factor loadings below the minimum threshold value required. All other items presented loadings equal to or higher than the minimum recommended threshold of 0.7 (

Götz et al. 2010).

Before analyzing the hypotheses presented in

Figure 1, the industrial sector, firm size (number of employees) and firm age were tested as control variables. The results are shown in

Table 5. As such, it is possible to conclude that there are no statistically significant differences for the variables analyzed. Therefore, the resources of larger firms are not very different from the resources of smaller firms, older firms do not possess better resources or capabilities than smaller firms, and the different sectors do not perform differently.

Table 6 presents the analysis of the internal consistency and reliability of the scales of the three constructs used, based on Cronbach’s alpha, Rho-A, and the composite reliability (CR). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.924 for the differentiation strategy, 0.938 for the export performance, and 0.830 for the positional advantage, all above the recommended value of 0.70 (

Hair et al. 2016). The Rho-A coefficients were 0.925 for the differentiation strategy, 0.947 for the export performance, and 0.880 for the positional advantage, all above the recommended value of 0.70 (

Dijkstra and Henseler 2015). The CR indicators ranged from 0.880 and 0.938, and are above the recommended value of 0.7 (

Hair et al. 2016). Finally, the convergent validity is assured, as the values of AVE are larger than the recommended value of 0.5 (

Fornell and Larcker 1981;

Götz et al. 2010); this means that all items converge when measuring the underlying constructs under assessment.

Discriminant validity seeks to demonstrate that a certain construct explains the variance of its own indicators better than the variance of other latent constructs (

Henseler et al. 2015). Therefore, the discriminant validity was assessed using two perspectives: the Fornell–Larcker and the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) criteria. The results are presented in

Table 7. While the Fornell–Larcker method compares the square root of the AVE with the correlation of all latent constructs (

Hair et al. 2019), the HTMT criterion indicates the need to compare a predefined threshold that ranges from 0.85 (

Kline 2011) to 0.9 (

Gold et al. 2001) to the actual result for each construct. When using the HTMT criteria, if the result is lower than this threshold—0.85 (

Kline 2011) or 0.9 (

Gold et al. 2001)—it is possible to claim that there is discriminant validity among the constructs (

Henseler et al. 2015).

Table 7 shows that the Fornell–Larcker and the HTMT criteria show discriminant validity.

4.1. Hypothesis Testing

The model shown in

Figure 1 was tested based on the sign, magnitude, and statistical significance of the parameters of the relationships tested, as supported by

Götz et al. (

2010). The coefficient of determination (R

2) of the endogenous variables was also analyzed.

Linear regression coefficients were used to test hypothesis H

1, H

2 and H

3. A hierarchical regression analysis (

Aguinis and Gottfredson 2010;

Arnold 1982;

Sharma et al. 1981) was used to test H

4. The variable ‘differentiation strategy’ was used as the independent variable. Finally, the effect of the variable ‘positional advantage’ was analyzed with the inclusion of the two relationships to be tested: differentiation strategy x positional advantage.

When testing for the mediation effects (

Hair et al. 2016), firstly, the significant direct effect between the independent and dependent variable should be established when the mediating variable is excluded. Secondly, the indirect effect of the mediating variable should be significant when the mediating variable is included in the model. Finally, the relationship between the independent and dependent variables should be significantly reduced when the mediator is added. These three steps were carried out in this study using PLS-SEM.

Table 8 and

Figure 2 present the results of the effects of the variables and the confirmation of the hypotheses. It is possible to conclude that all the structural relationships tested have positive signs and parameters, which is in accordance with the assumptions made. According to the results, the differentiation strategy has a positive effect on export performance, i.e., the results obtained support and validate hypothesis H1 (β = 0.462;

p < 0.001); therefore, the differentiation strategy positively affects the export performance. The model tested the relationship between the differentiation strategy and the positional advantage, indicating that the differentiation strategy has a positive effect on the positional advantage, validating hypothesis H2 (β = 0.622;

p < 0.001). The results confirm H3 (β = 0.221;

p < 0.001), since the positional advantage has a positive impact on the export performance. Finally, the data confirm and validate hypothesis H4, whereby the positional advantage has a positive mediating effect on the relationship between the differentiation strategy and the export performance (β = 0.138;

p < 0.001).

Figure 2 shows that the determination coefficient (R

2) of the export performance is 0.390, i.e., both the differentiation strategy and the positional advantage explain 39% of the variance in the export performance. Moreover, the differentiation strategy alone explains 38.7% of the variability in the positional advantage of exporting Mozambican firms, giving a clear importance to the differentiation strategies the Mozambican firms manage to deploy.

When assessing the effect size, as shown in

Table 8, it is possible to claim that, based on

Cohen (

1988), the differentiation strategy has a medium effect (f

2 = 0.215) on the export performance, the positional advantage has a weak effect (f

2 = 0.049) on the expert performance, and the differentiation strategy has a strong effect (f

2 = 0.631) on the positional advantage. These results corroborate the explanatory power of the differentiation strategy when explaining the R

2 obtained for the positional advantage and export performance.

Table 8 shows that the direct effect of differentiation strategy on export performance (β = 0.462) is larger than the indirect effect (β = 0.138). To complement this analysis, and to assess the strength of the mediation effect,

Zhao et al.’s (

2010) three-factor approach was used, in which it is possible to assess how the indirect effect absorbs the direct effect.

Given the values presented in

Table 8 and

Figure 2, the proportion of the indirect effect versus the total effect is 0.23 − (0.138)/(0.138 + 0.462) = 0.23 –, which indicates that the positional advantage partially mediates the relationship between the differentiation strategy and the export performance. These results also corroborate the results obtained when assessing R

2 and f

2: competitive strategy plays a more important role in explaining the export performance than the positional advantage does.

The results for the sample of 250 firms show that the cut-off value for the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) is 0.044, which is lower than the threshold value of the SRMR = 0.06 for samples with N > 500, and lower than the recommended value of the SRMR = 0.091 for samples with 200 respondents (

Cho et al. 2022). As such, the model fit is assured.

4.2. Discussion and Implications

The conceptual model proposed in this paper integrates the differentiation strategy, positional advantage, and export performance. The results confirm that the differentiation strategy has a positive effect on the export performance of Mozambican SMEs, corroborating with the literature on this matter (

Aulakh et al. 2000;

Crespo et al. 2020;

Morgan et al. 2004;

Keskin et al. 2021). The following can be argued: first, that the differentiation strategy, related to the use of unique attributes vis-à-vis competitors (

Porter 1985), is successfully used by Mozambican SMEs to increase their export performance; second, the role of economic blocs in emerging economies have allowed firms to have privileges in exporting their products to developed markets (

Aulakh et al. 2000;

Ministério da Indústria e Comércio 2016); and, third, the adoption of differentiation strategies is an important option for entrepreneurial firms and SMEs when competing in international markets (

Knight and Cavusgil 2004;

Martin et al. 2017). This confirms previous studies, as Mozambican SMEs show that the unique resources they possess are important to tailoring their products and services; this means that they are not easily imitated by their domestic competitors, and so that they take full advantage of their resources in international markets (

Banker et al. 2014;

Knight et al. 2020;

Zehir et al. 2015).

The results also suggest that the positional advantage mediates the relationship between the differentiation strategy and the export performance of Mozambican SMEs, because as firms gain positional advantage as a result of competitive differentiation strategies, their export performance increases. This confirms the results presented by

Martin et al. (

2017). This result can be substantiated by the fact that firms’ differentiation strategies are effective in achieving a differentiation-based competitive advantage, supporting firms’ export performance (

Keskin et al. 2021). Firms achieve a higher export performance through the sustainability of positional advantages as a result of the efficient and effective execution of the differentiation strategic advantage (

Morgan et al. 2004;

Porter 1985). Despite providing important drivers of competitive advantage and directly affecting the export performance of Mozambican SMEs, positional advantages mildly moderate the direct effect of the differentiation strategy; this may indicate that Mozambican SMEs are not properly taking advantage of their positional advantage, i.e., the added value generated by the positional advantage is still relatively low, perhaps as a result of the low differentiation that Mozambican SMEs still experience in international markets. As such, if differentiation strategies help Mozambican SMEs to make products and provide services that are different to their competitors and that are supported in their competitive advantages, they still have to invest in their positional advantages in international markets to overcome fierce international competitors.

This research presents implications at the level of the literature focusing on the development of theory in international marketing and internationalization; it also adds to the body of empirical studies that prove that, in the context of SMEs in emerging economies, differentiation strategies play an important role in supporting the internationalization path (

Aulakh et al. 2000). In parallel, the positional advantage plays an important mediating role in the relationship between the differentiation strategy and the export performance, indicating that the positional advantages may further sustain competitive strategies and improve firm performance (

Martin et al. 2017).

Regarding management implications, the study concludes that SME managers should, on one hand, value competitive differentiation strategies and, on the other hand, make SMEs assume positional advantages in their sectors of activity, in order to increase their export performance in international markets. If the RBV of the firm supports companies to achieve their competitive advantage, Mozambican SMEs would need to invest more resources to develop their product and the positional advantages of their services, in order to gain international credibility and to support their differentiation strategies. As resources can rarely be easily purchased or transferred, if Mozambican SMEs are to develop their competences and resources over time, public policies are needed to support the development of internal competitive advantages and to develop a proper organizational climate; this is so that Mozambican SMEs can manage difficult-to-imitate products and services and develop proper international appealing positional advantages.

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Perspective

This article aims to measure the impact of differentiation strategies on the performance of exporting firms and to determine the mediating effect of the positional advantage in this relationship. The results show that the differentiation strategies have a direct positive effect on export performance, which leads us to conclude that Mozambican SMEs, by adopting a product and service-based differentiation strategy, can increase their competitiveness and ability to access international markets, as well as increase their export performance. The results also indicate that positional advantage has a positive mediating effect upon competitive strategies and export performance; therefore, SMEs that have solidified their positional advantage, as a result of differentiation strategies, increase their export performance. This result is very important for an emerging economy, as it is possible to conclude that small ventures and SMEs from emerging countries can benefit from differentiation strategies and positional advantages in their international path. However, Mozambican SMEs, as well as most SMEs in emerging markets, still have to invest in unique resources and capabilities if they want to achieve different, unique competitive advantages and develop a strong international positional advantage.

This research presents limitations. The first limitation is the fact that it is a cross-sectional study. Future research should aim to generate longitudinal data to obtain the dynamic influences. Second, although the use of single respondents is not advisable, despite all the efforts to mitigate CMB, circumventing single response bias was impossible to achieve in the Mozambican context. In this case, future research should increase the number of respondents from each company. For future research, we also integrated the mediating effect of the international experience of SMEs in this conceptual model, since it would be important to know the role of the international experience in the relationship between differentiation strategies and the export performance of these firms, particularly in the context of developing countries. Future studies, method wise, could test similar models in emerging contexts using consistent PLS-SEM or CB-SEM.