Abstract

Migrant labor market integration is vital for the resilience of the host country and the migrant population’s sustainable livelihood. Greece, which hosts thousands of new immigrants, could seize the private sector’s experience to offer effective and holistic labor market integration opportunities to its migrant labor force. This paper explored the challenge for Greece as examined using a system dynamics methodology of the effects of wage subsidies and vocational training products on the employability of both the native and migrant populations in a framework of public–private cooperation under different scenarios and external factors.

1. Introduction

The surge in the migrant population in the European member states after 2015 led to the revision of the Common European Asylum System and the Commission’s proposal for a New EU Pact on Migration and Asylum (European Commission 2020b). Migrant integration has been clearly considered as an important area to focus on toward achieving social cohesion and enhancing the resilience of the EU economy. In the EU Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion 2021–2027 (European Commission 2020a), migrant labor market integration has been recorded as a key area both for the EU Commission and for the member states to take the necessary actions and support the incoming third-country nationals as well as the EU population with a migrant background. Employment is a crucial parameter for the successful integration of all types of migrants (forced migrants, labor migrants, family reunions, etc.) in a host country (Sironi et al. 2019). Economic self-dependence is a necessary step toward sustainable livelihood and the migrants’ contributions in their host countries (Khoudour and Andersson 2017).

Greece has been in the frontline of the migration flows toward the European Union. According to UNHCR (2021) data, as of February 2021, 91,945 migrants were recognized as refugees by Greece and 80,784 were waiting for their asylum application to be examined. Asylum applicants can work six months after they have filed their asylum application if it remains under process, but they have immediate access to vocational training (Law 4636 of 2019). However, there is no targeted support to refugees due to either the scarce resources or the tight labor market (European Commission 2017). The aforementioned UNHCR factsheet for Greece states that the actual number of new immigrants present in the country is probably lower because recognized refugees might have moved to another European country. Nevertheless, their labor market integration is vital for the wellbeing of the community but is challenging because Greece’s economic crisis led to a worsening of the structural problems of its labor market (Koukiadaki and Kretsos 2012), and the migration inflows increased the labor force in the country.

Although there is no available statistical data on the exact share of refugees working the labor market, the latest labor force survey of the Hellenic Statistical Authority (2020) indicates that as of 2019 there were 369,400 people over the age of 15 with non-EU citizenship living in Greece of whom 195,000 were employed. This represents almost 5% of the employed population in the Greek labor market. The statutory minimum wage policy prevents migrant workers from being remunerated with lower wages than the native labor force, and they are all taxed on their income following the same taxation as all Greek residents. However, the economic recession and the measures taken to overcome it deepened the negative impact the crisis had in the Greek labor market by affecting the labor force and particularly the migrant population, which suffered from high unemployment rates and income losses (Ozdemir et al. 2016). As a consequence of austerity measures and low labor market demand, soon after the initial migrant inflows, opposition began to arise; a major share of the concerns focused on perceptions of increased competition over the limited available jobs (Connor 2020). The gradual recovery of the Greek economy was interrupted by another economic shock caused by the COVID-19 pandemic mobility restrictions, which affected important sectors of the Greek economy and labor market such as tourism.

The cooperation of the Greek public employment services with the private firms active in the field is considered an important tool to increase the long-term prospects of the Greek economy after the pandemic that can take advantage of the skills and experience of the migrant population present in the country (Bulman 2020). OECD’s report (OECD 2018) for migrant-integration policies implemented at the local level makes reference to the importance of multi-stakeholder partnerships with non-state actors and highlights the example of the city of Athens. The municipality of Athens collaborates with 70 stakeholders to map the needs and identify the gaps in the provision of services and define a comprehensive service-delivery system for migrant integration in Athens (OECD 2018).

Drawing upon the aforementioned situation of the Greek economy and labor market and the associated effect on social cohesion, the purpose of the current paper was to investigate the effects that specific types of public–private cooperation highlighted in the relevant literature could have on the employability of both the native and the migrant population under different scenarios and external factors. More specifically, in the context of the current paper, wage subsidies by the state to hire immigrants and the development of vocational training products that increase the productivity of the workforce (for both the native and migrant population) were examined to identify their effects on: (1) the finances of the state and businesses, (2) the unemployment rate of the native and migrant populations, and (3) the country’s social unrest and societal polarization. To answer the research question, a system dynamics methodology was used, and the results generated by the simulation model were analyzed with the help of machine learning algorithms.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The next section provides an overview of private-sector engagement in migrants’ employability. A literature review on how researchers assessed public–private cooperation along with the initiatives undertaken by the private sector in Greece follow. Furthermore, the rationale for using system dynamics is presented, and the structure of the simulation model is described. The section after that presents the results and their analysis to identify how they fared against the literature, while our conclusions and the implications for public policymaking are discussed in the last sector.

2. Private-Sector Engagement in Migrant Labor Market Integration

National, European, and international policy papers make reference to the contribution of the private sector’s engagement in the integration of migrants. In detail, the Greek National Strategy for Integration (Hellenic Ministry of Migration Policy 2018) makes extensive reference to the importance of the private sector’s participation in the efforts regarding social inclusion of the migrant population. In fact, it refers to the lack of cooperation between public authorities and private associations, which began after the negative effects of the global financial crisis on the labor market had occurred. The document sets the framework of cooperation in the field of skills and qualification mapping, increasing awareness of cultural diversity, providing employment opportunities, transferring knowledge, mentoring, consulting, training, and participating in co-funding schemes for entrepreneurial activities or sponsorship. The aim is on the one hand to adapt migration policies in addressing labor market gaps and on the other hand to motivate the private sector to act as a supplement to the governmental integration policies.

At the European level, the New EU Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion 2021–2027 (European Commission 2020a) engages several societal groups in the process of integration that include public authorities, civil society organizations, social and economic partners, and the private sector. In detail, member states are encouraged by the EC to motivate private stakeholders to engage in migrant integration through public–private cooperation by offering employment initiatives and developing new tools. The private sector is also mentioned in the field of support for entrepreneurial activities by migrants, who could benefit from the offering of mentoring or training projects, and in the field of funding opportunities. Moreover, in September 2020, the EU Commission ensured the participation of the economic and social partners in the field of labor market integration by renewing their partnership (European Commission 2020c, 7 September). The “Employers together for Integration” was another EU Commission initiative that was created in 2017 to drive the active participation of the private sector (https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/legal-migration/european-dialogue-skills-and-migration/integration-pact_en, accessed on 10 June 2021). In the European Migration Network Report (European Migration Network 2019) on labor market integration of third-country nationals, there were 12 identified good private-sector initiatives in the field of information and counseling measures, 11 in the area of training and qualification, and 9 for the enhancement of intercultural/civic relations.

At an international level, partnerships with the private sector for employment creation, vocational training, and the support of entrepreneurship were mentioned as actions that could reduce emigration from the country of origin at the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (United Nations 2019). Regular migration pathways could also be facilitated in cooperation with the private sector by using its information for effective skills matching. It was actually mentioned that partnerships for capacity building of both public and private agencies are important to effectively train workers to increase their employability. Online and on-the-job advanced training following labor market dynamics has also been stressed as an area in which the private sector could substantially assist (Dos Reis et al. 2017). Furthermore, in the UN Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development (United Nations General Assembly 2015), there is a reference to the contribution of the private sector in the achievement of the sustainable development goals. The target 17.17 pays attention to the cooperative schemes between the public and private sectors that could serve as a tool for the implementation of the Global Partnership for Development by integrating and employing their expertise.

OECD’s report (OECD 2018) on the local integration of migrants and refugees pointed to the funding the private sector could offer to the public initiatives for migrant integration, the outsourcing of services, and the development of strong networks that could bring migrants closer to the private sector. Through a series of regional dialogues, OECD and UNHCR (OECD/UNHCR 2018) identified 10 key areas to facilitate the labor market integration of refugees that highlighted the support the employers and their association could offer. The administrative framework, the duration of stay of refugees, the mapping of their skills, their training, job matching, anti-discrimination measures, the preparation of the working environment, long-term employability prospects, business cases for hiring refugees, and the coordination of various stakeholders are all actions in which the private sector could make a significant contribution to the employment of refugees.

Sponsoring the resettlement of refugees has been one of the most influential roles of the private sector (Howden 2016). It is worth mentioning the comments of the CEO of the Emirates Foundation, who said that venture philanthropy is more appropriate to replace the role of corporate social responsibility for the engagement of private companies in offering sustainable solutions for refugees (Howden 2016). In 2016, U.S. President Barack Obama called private companies to assist in the refugee crisis with resources and expertise in three basic sectors that included employment (The White House 2016, 30 June). The call managed to attract 51 companies that subsequently committed to increasing the employment opportunities of 220,000 refugees through mentorship, training, internships, and job placements.

Apart from job creation, other solutions offered by the private sector include the sponsoring of the delivery of basic needs to migrants, lobbying for migrants’ rights, and the facilitation of their access to finance systems or innovative financing schemes such as crowdfunding, which is especially necessary for entrepreneurial activities (Bisong and Knoll 2020). Private training providers could also contribute to adult skill training (Bulman 2020). The International Finance Corporation (2019) cooperated with the Bridgespan Group in a study of 173 private-sector initiatives in the Middle East and Africa in order to map the alternative ways in which private companies engaged in offering sustainable long-term solutions to people in need of international protection. The five most common pathways they spotted included the sharing of capabilities, job training and entrepreneurship support, job creation (direct or through sourcing and subcontracting), the adoption of business models to sell goods and offer services to refugees, and even the creation of a business focused on this target group.

The International Finance Corporation Report (International Finance Corporation 2019) also focused on the motivations of private-sector engagement and concluded that the majority of actors desire a positive impact on the lives of refugees in order to keep up their efforts. There are certain criteria that facilitate private-sector engagement such as flexible financing, information investment, and cross-sector partnerships; there are also several barriers to overcome such as the national regulatory constraints, the lack of data, the social and economic contexts, and the geographic barriers.

Gradl et al. (2010) presented an indicative list of motivations for the engagement of the private sector in development and particularly in fulfilling the Millennium Development Goals. The increased pressure from advocacy groups as well as the search for reliable supplier relationships and new growth markets are common motives for multinational companies. Large domestic firms are more interested in their ties to the local community and the political stability of their country. Apart from their dependence on the established relationships with the local population, SMEs also need a competitive advantage that can be found through such an engagement.

Another interesting report with regard to the motivations for the involvement of the private sector in intersectoral partnerships to overcome market or government failures through active labor market policies was conducted by the Rand Corporation (Glick et al. 2015). Although the report refers particularly to youth employability, it is an indicative example that could be attributed to the case of the private-sector engagement in migrant integration as well. An enhanced brand value, the approval of the community, improvements in employee attachment and community development that could lead to increased demand, access to a skilled local workforce, improved supply chains and distribution networks, and the alignment of education and training with the labor market were stressed in the report. However, such motivations can easily be outweighed by the barriers that private companies usually face in their efforts to participate in development actions. Financial and time costs, externalities, limited technical capacity, imperfect information and uncertainty, reputational risks, or a lack of trust could hinder the involvement.

3. Findings from the Literature Review, Desk Research, and Field Research

As Hübschmann (2015) pointed out, market failures such as the inequalities in income, the lack of sufficient information regarding available services and employment, labor market performance and employment gaps between natives and migrants, negative externalities resulting from migrant economic underperformance, and need of social assistance make policy interventions in the field of migrant integration necessary. Additionally, the collaboration of the public with the private sector is essential to overcome potential government failures in the implementation of active labor market policies, which were designed to overcome the market failures due, for example, to a lack of accountability (Glick et al. 2015) and increase employment and job matching (European Commission 2016).

According to the OECD’s glossary (OECD 2001), “Active labour market programs includes all social expenditure (other than education) which is aimed at the improvement of the beneficiaries’ prospect of finding gainful employment or to otherwise increase their earnings capacity. This category includes spending on public employment services and administration, labour market training, special programs for youth when in transition from school to work, labour market programs to provide or promote employment for unemployed and other persons (excluding young and disabled persons) and special programs for the disabled”. Active labor market policies (ALMPs) usually incorporate language and introduction courses, job search assistance, training programs, and subsidized public and private-sector employment (Butschek and Walter 2014). Butschek and Walter performed a meta-analysis of 33 evaluation studies on ALMPs on immigrants and concluded that wage subsidies were more efficient for immigrant integration than public works and training programs. Subsidized private-sector employment is also considered beneficial to promoting employment for immigrants in the short run, which was seen in the case of the Nordic countries (Andersson 2019). Clausen et al. (2009) concluded that subsidized private-sector employment was the most efficient program for newly arrived immigrants in Denmark. Nekby (2008) also reviewed the literature on ALMPs in Nordic countries and concluded that the most beneficial measures particularly for immigrants were wage subsidies. Kluve (2010) used a meta-analysis of 137 programs to evaluate the effectiveness of four types of ALMPs that were implemented in 19 European countries without limiting the research on specific groups. Following the analysis, the private-sector incentive programs as well as the “Services and Sanctions” (all measures that increase job search efficiency) had a higher probability of positive post-program employment outcomes than training and direct employment programs. On the other hand, Card et al. (2010) focused on a meta-analysis of 199 programs from 97 studies conducted between 1995 and 2007 on ALMPs and found that classroom and on-the-job training had a higher impact than subsidized private-sector employment, while subsidized public sector employment was the least efficient measure. Lechner et al. (2004) analyzed different types of training programs in West Germany over a seven-year period and concluded that their impact was negative in the short run but became positive after a period of four years.

Wage subsidies for private-sector employment are among the active labor market policies that host countries use to facilitate the integration of immigrants. Subsidized employment refers to wage or hiring subsidies for temporary or permanent transfer to private firms or the creation of temporary jobs for specific groups of the labor force (Rinne 2012). Such measures cost relatively more than other programs, target specific groups, and provide employers with the opportunity to test prospective employees at a low cost (European Commission 2016). In fact, one-sixth of ALMP spending in Europe went to employment incentives (European Commission 2016). Job creation is one of the main contributions of the private sector in development as well. In particular, SMEs, which comprise 95% of all firms outside the agricultural sector, offer a major source of employment in developing and middle-income countries (Di Bella et al. 2013).

SMEs comprise 96% of all enterprises in the Greek labor market and employ 55% of the total labor force. The main features of the Greek labor market also include a low labor demand concentrated mostly in urban areas; labor demand for low-skilled workers particularly in the primary sector, manufacturing, and tourism; seasonal employment; and a lack of connection between training and labor market needs as well as between labor market integration policies and labor market needs. Before the economic crisis, Greece implemented active labor market policies such as subsidized employment; training programs and programs for social integration; and companies’ structural adaptation with several deficiencies in their design, implementation, and management. However, Greece reduced its expenditures on labor market training by 88% between 2009 and 2010 (Kennedy 2018). Moreover, the actions taken during the economic crisis lacked the necessary connection with the needs of the labor market (Galata and Chrysakis 2015). Wage subsidies for private-sector employment prevailed among the ALMPs implemented in the country between 2008 and 2014 (Kennedy 2018).

Unfavorable economic conditions deeply affected the migrant population already residing in Greece and made the Greek labor market undesirable for newcomers. During the period of 2007–2013, the unemployment rate of foreigners increased by more than five times (from 7.6% to 39.3%) (Blouchoutzi 2019). The number of immigrants working in manufacturing and households dropped by 50%, while a greater decline occurred in the number of construction workers, which dropped by 78% (Blouchoutzi 2019). According to the interviews implemented in the framework of the Horizon 2020 (GA 822806) MAGYC project (https://www.magyc.uliege.be, accessed on 23 January 2023), the most important barrier for private companies to employ the newcoming migrant population, refugees and asylum seekers has been their desire to leave Greece. “Migrant integration is a contradictory concept for Greece taking into consideration that migrants do not wish to remain in Greece“ (DRC, NGO 2 January 2020). “Unemployment in Greece pushes refugees towards other European Member States” (Omnes, NGO 30 September 2020). Migrant workers used to be concentrated on the construction and household sector before the economic crisis, but had to move toward the commerce, the food and the hospitality industries afterward (Blouchoutzi and Nikas 2018). These economic sectors are all characterized by increased shares of undeclared work (International Labour Organization 2016). Moreover, the polarization and fragmentation of migrant labor market integration policies failed to address the challenges the newcomers face, which also pushed them in the underground economy (Bagavos et al. 2019). There is no single or central body responsible for combatting or coordinating efforts to prevent undeclared work; the institutional framework is quite fragmented, and responsibilities are shared by different authorities such as the Hellenic Labour Inspectorate, the Ministry of Finance, and the United Body of Social Insurance. Strict fines, reductions in non-wage costs, and the simplification of administrative procedures have been among the most usual measures implemented by the Greek state to reduce undeclared work (International Labour Organization 2016).

The allocation policies of the refugee population in camps and other accommodation schemes present extra difficulties because they are not close to the urban areas where most of the available job positions are offered. According to the interviewees of the MAGYC project, the first prerequisite for the recruitment is the knowledge of the Greek language and a basic vocational training in order to be able to respond effectively to the job requirements. The mapping of their skills is also necessary, and the non-ratification of the Lisbon Convention on Recognition of University Qualifications on behalf of the Greek state poses extra problems (Bulman 2020). Interviewees also mentioned the lack of targeted wage subsidies for employers in Greece to hire refugees (Directorate of Social Protection, Education and Culture and Community Center/Municipality of Karditsa 16 July 2020).

The integration project HELIOS that is currently running in Greece contributes to the employability of the refugee population through language courses and job counseling sessions (https://greece.iom.int/en/hellenic-integration-support-beneficiaries-international-protection-helios, accessed on 10 June 2021), but there is no exclusive body in Greece that is dedicated to controlling private initiatives to employ migrants and their compliance with the ethical standards. Following the legally non-binding National Integration Strategy, which included a provision for the employment of refugees in the agricultural and manufacturing economic sectors as well as for vocational training courses and certification of qualifications on specific professions, the Ministry of Migration and Asylum signed a memorandum of cooperation with the Agricultural University of Athens for the fast-track one-month vocational training of refugees and migrants to become land workers (Agrotypos 2021, 10 March).

However, there have not been any systematic official job-matching projects for the newcomers so far. The majority of the initiatives have been introduced by civil society organizations or on an ad hoc EU-funded project basis. One of the most prominent initiatives for a multi-stakeholder partnership that has been implemented in Greece is a pilot activity in the framework of the Labour-Int project (http://www.labour-int.eu, accessed on 23 January 2023) run by the Vocational Training Centre of the Hellenic Confederation of Professionals, Craftsmen, and Merchants (KEK GSEVEE) and the Center of Athens Labor Unions entitled “Bridging the gap from reception to integration. A holistic approach to the labour market integration through a multi-stakeholder cooperation in Athens, Greece”. The action, which includes integration training seminars and a pilot testing of the EU Skills Profile Tool, has as its objective the inclusion of asylum seekers and refugees in the labor market by focusing on enhancing their skills and qualifications. The Institute of Labour of the General Confederation of Greek Workers (INE/GSEE) and the Small Enterprise’s Institute of the Hellenic Confederation of Professional Craftsmen AE (IME/GSEVEE) participate in the MigrAID Erasmus+ project (https://migraid.eu, accessed on 23 January 2023) with the objective to help the representatives of employers and trade unions to manage ethnic diversity and promote migrant integration in European SMEs. Another project that brings together the public and private sectors to improve migrants’ labor market integration is the MILE project funded by AMIF (https://projectmile.eu, accessed on 23 January 2023). In detail, the project aims to enhance the competences of the multiple stakeholders in the field of labor market integration of migrants and develop a methodological scheme toward this purpose with the involvement of employers. The Regional Department of Central and Western Thessaly of the Technical Chamber of Greece also cooperates with the municipality of Larissa in a multi-stakeholder partnership with partners from the public and private sectors to facilitate the Integration of Third-Country Nationals in the Construction Sector project (https://www.in2c.eu/en, accessed on 23 January 2023). Entrepreneurial activities could be an alternative way out of unemployment for third-country nationals and a field in which the private sector could offer valuable insights, experience, and funding. The “TREND—Training Refugees in Entrepreneurial skills using digital devices” Erasmus+ project aims to foster the entrepreneurial skills of refugees (https://akep.eu/trend-project-news-may-2020, accessed on 23 January 2023). Social entrepreneurship and social cooperative enterprises could also promote the employability of migrants and refugees and have a considerable social impact. The Social Fashion Factory (https://soffa.gr, accessed on 23 January 2023) is such an example; it creates sustainable fashion garments in a cooperative of fashion designers. STARAMAKI (https://www.staramaki.gr, accessed on 23 January 2023) is another successful social cooperative enterprise that offers labor-inclusive opportunities for vulnerable groups of people to produce alternatives to plastic straws made from natural wheat stems. However, social cooperative enterprises that employ migrants in Greece number just a few for the time being.

Due to the lack of necessary policies, their poor implementation, the structural weaknesses of the Greek labor market, the economic recession, and the migrant influx, societal polarization and social unrest emerged. Societal polarization usually refers to the social impact of economic restructuring or the economic changes that expand occupational and income structures and increase inequalities between the top and the bottom ends of the distribution (Sassen 1991). However, in the context of the current paper, the term is used interchangeably with “Social unrest”, and they are meant to represent the same processes. During the first wave of mass migration toward Greece in the 1990s, immigrants’ skills used to be complementary to the native workers’ skills. After the economic crisis, immigrants began competing with the natives for the same jobs (Blouchoutzi 2019). As a consequence, Greeks have been in favor of humanitarian response toward the asylum seekers, but they are opposed to the permanent presence of refugees in their country (Dimitriadi and Sarantaki 2018).

To summarize the results of the literature review and our desk and field research, the authors concluded that the private sector could play a crucial role in increasing employability. Greece continues to face the challenge of migrant labor market integration no matter how vital it is for social cohesion, wage subsidies are an important but costly parameter for increasing employability, and vocational training has been considered a prerequisite by Greek employers to hire low-skilled workers. Following the inter-relationship of the above-mentioned parameters and their significance in the case of Greece as argued above, we identified a research gap in estimating the impact that wage subsidies and vocational training could have on the finances of the public and private sectors, the unemployment rates of both the native and the immigrant population, and social unrest in Greece, so we proceeded with an exploratory analysis to address this issue. Since wage subsidies were previously implemented in Greece to increase employability, it was important to examine the viability of this policy measure as regards its effect on the public finances of a country that recently recovered from a recession. Moreover, given that one of the main concerns of the private sector in engaging in a migrant labor market integration process is its cost, the impact of such a measure was a necessary parameter to be explored in terms of sustainable relevant policy proposals. Unemployment of the immigrant population was operationalized to identify the central focus of this study, which was the effect of public–private cooperation on migrant labor market integration. The impact on the unemployment of the native population was also tested to identify whether there were different effects of such ALMPs on the native and the migrant populations and to identify its consequent effects on social unrest, which are also factors considered by private companies to engage in the integration of migrants.

4. Methodology

4.1. System Dynamics

As highlighted above, migration inflows have been one of the major issues that EU countries constantly face. The issue can be characterized as a crisis because some of its features are deep uncertainty, unpredictability, a limited time to make decisions, and of course different perspectives on how to approach it (Boin et al. 2005). Thus, any attempt to solve the issue must be based on policies that are supported by evidence, tested if possible, and agreed upon by the stakeholders, who have different and even conflicting objectives (Estrada 2011).

In that aspect, policy modeling has emerged as a scientific field that aims to help policymakers to design, justify, implement, and monitor policies (Tsoukias et al. 2013). One of the methods that is used in policy modeling is system dynamics (Forrester 1997), which is a computer-based methodology that assists policymakers in understanding the behavior of complex systems over time (Sterman 2000). The methodology is focused on understanding how a system’s structure can affect its behavior (Schwaninger and Rios 2008) by using a top-down, holistic approach and a generic representation of the system under study (Tsaples and Armenia 2016). It uses stocks and flows to represent the system while at the same time non-linearities and time delays are integral parts of the modeling process (Armenia and Tsaples 2018). Finally, system dynamics allows the experimentation with different policies, which offers the possibility to investigate their consequences in a safe environment (Armenia et al. 2018).

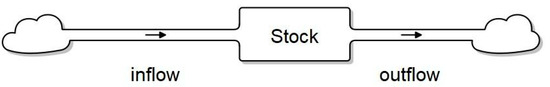

Figure 1 below illustrates a typical stock-and-flow structure, the mathematical formulation for which is:

Figure 1.

Stock and flow structure of a system dynamics model.

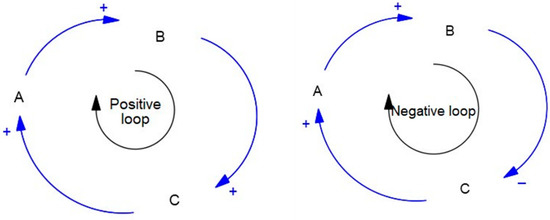

Moreover, system dynamics has a qualitative dimension with which the structure of a system under study can be illustrated and studied called a causal loop diagram (CLD), which is a causal map of the most important elements/variables of the system and how they are causally linked. Figure 2 below illustrates the primal CLDs of feedback loops, which are some of the most important elements of system dynamics.

Figure 2.

Positive feedback loop (left) and negative feedback loop (right).

The plus and minus signs in the figure indicate the polarity of the causal link: a positive (+) polarity means that an increase (decrease) in one variable will result in an increase (decrease) in the other variable. On the other hand, a negative (−) polarity means that an increase (decrease) in one variable will result in a decrease (increase) in the other variable. These simple structures form feedback loops that give rise to the system’s behavior. For example, Figure 2 (left) illustrates a typical positive feedback loop: an increase in the value of variable A will result in an increase in the value of variable B, which will increase the value of variable C. However, variable C affects variable A, hence its increase will result in a further increase in variable A. Thus, a positive feedback loop causes an exponential increase (or decrease) in a system. On the other hand, a negative feedback loop brings the system to a balance.

These simple structures assisted researchers and policymakers in analyzing and investigating various complex systems; as a result, migration structures became an integral part of system dynamics models. For example, Auping et al. (2015) studied societal ageing in the Netherlands and included the effects on and needs of migrants. Moreover, some researchers focused solely on the migration issue. Naugle et al. (2019) developed a model of migration that included the environment and the climate crisis as a part of the choice to migrate. Kozlovskyi et al. (2020) investigated how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the policies on migrant labor and the economic growth of countries. The labor of both native and migrant populations was also the focus of works by Harding and Neamţu (2018) and Chávez et al. (2011). Finally, migration dynamics among several countries was the focus of a thesis by Wigman (2018). While the list of works we have described is not exhaustive, to the best of our knowledge there have been limited efforts to combine economic structures with societal polarization and investigate what effect public–private policies could have in such a context.

4.2. Model Structure

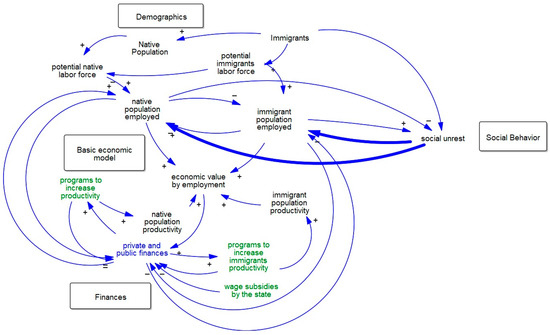

For the current paper, the CLD is depicted in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

CLD of the immigration system.

As can be observed, the complexity of the system is represented by the number of causal links among the variables and the formation of various feedback loops. In its basic form, the model had a population sector that included the native and the immigrant population without distinguishing between different types of migrants. The native population increased with births and decreased with deaths. Moreover, the immigrant population increased with the inflow of immigrants and decreased with their naturalization (which increased the native population) and with secondary movements of the immigrants to other countries.

The other sector of the model was a generic economic model. Both the native and immigrant population increased the demand for products, which increased the labor demand of businesses. These businesses could find labor in either the native or the immigrant population and create value for the entire country. The employees generated products through their productivity and were paid through wages. The generated products were those that satisfied the aggregate demand. Consequently, the economic sector of the submodel did not explicitly take into account employees’ mobility (the shift in labor according to skills), and it was assumed that natives and immigrants were doing the same jobs. Further assumptions included the fact that no other sector of the economy was modeled, thus any employment/unemployment in the simulated country originated only from private businesses that produced a generic product. Finally, the demand for that product was not affected by external factors such as market dynamics, energy dependencies, etc.

Such an economic structure might be simple but is not simplistic, and the analysis could hold for several economic sectors. Even with all the above assumptions, the simulation could reveal insights into the dynamics of private labor in a situation such as the effects of migrant flows, in which the levels of complexity are extreme; evident in numerous sections of the economic and social structures of a country; and finally are driven by human prejudices, ideologies, and behaviors that cannot be depicted accurately in any type of mathematical model.

Another section of the model focused on the finances of the businesses and the state. Since one of the main concerns in the implementation of active labor market policies and the private-sector engagement in labor market integration is the relevant costs, the effect of the proposed measures on the finances of the involved stakeholders was a crucial aspect to be explored. For businesses, the revenues increased with the number of products and services required by the increasing demand, while the cost included the wages for their labor. For the public finances, additional expenses came from an increase in public spending due to an increased cost of social benefits. The public–private cooperation acted in this part of the simulation model. The wages for the employees were paid by the businesses, but the state could subsidize part of that wage (policy 1), while vocational programs that were used to increase the productivity of employees could be paid either by the private stakeholders (businesses) or once again the state could contribute a percentage and share the cost (policy 2).

The final section of the model attempted to represent the social unrest that might be created by the presence of immigrants and their effects on the employment or not of the native population. This entire phenomenon is called societal polarization because it attempts to capture and represent processes that may not be always visible. Examples include the increased use of “anti-immigrant rhetoric”, unrest in the form of protests, violent episodes, etc. In order to capture all these social phenomena, the term “Societal Polarization” was preferred, but in the context of the current paper, the term was used interchangeably with “Social unrest”; they were both meant to represent the same processes. Social unrest is a variable that took values between 0 and 1; a higher number meant that the country faced violent incidents and widespread polarization, and lower numbers indicated a relative peace. This part of the model was inspired by the model developed by Bossel (2007) in which social unrest acts directly on the decision of the businesses on how many immigrants they would hire instead of native labor because, as mentioned above, private companies are interested in their reputation and the approval of the community.

These policy variables (programs to increase the productivity of native and/or immigrant population and a wage subsidy by the state that would incentivize private businesses to hire more immigrants), which were the only public–private cooperation policies that were studied in the current paper, increased the financial cost for the state and businesses depending on which one was activated and at which level.

Regarding the data requirements, values for the case of Greece were used in particular for the demographic characteristics. Regarding the economic variables, what was used in the model did not strictly correspond to real-life case studies because the chosen variables represented proxies of actual values. For example, wages were not represented in euros (or any currency) but were modeled as a factor that took values from 0 to 1 (the higher the value, the higher the wage). This increased the communication capabilities of the model and allowed the focus to be on the medium- and long-term effects of the policies because in the context of the current paper, the focus was on the behavior of the economic elements and not on making accurate predictions. This assumption, when combined with the knowledge that it is not possible to know how migration flows will occur in the future, how societal pressure can affect economic decisions, what could be the consequences of those decisions, and which economic model most accurately describes the economy of a country—all while not resorting to an extremely complicated mathematical model (that would also be detrimental to its communication capabilities)—led us to focusing the current paper on the exploration of the need to test whether public–private cooperation on the migration issue is real and should be robust despite the deep levels of uncertainty that surround the issue and the challenges that arise for host countries such as Greece. Moreover, the model structure that was presented above originated from insights from the literature, interviews with experts, and our perceptions regarding the issue. Furthermore, trade-offs were necessary: the overall system was very complex and involved data that might not be available and variables that might not be easily quantifiable. Moreover, no claim was made that the model was the only “appropriate one” to represent such a system and test various policies; there were other perceptions that could be included along with different relationships, variables, etc. Thus, this model was only one of the many that could be used to study the effects on migrants’ employability.

However, even such a model with deep uncertainties could offer valuable insights into potential policies and their consequences in the medium- and long-term horizons. Nonetheless, in order for these insights to be robust, the uncertainties and limitations of the model were not hidden and were specifically used in the analysis. To do so, a computational framework was developed in the context of the current paper that attempted to test the robustness of such policies. Such an approach fell under the umbrella term of exploratory modeling and analysis (EMA). EMA (Bankes et al. 2013) is a framework that favors the use of quantitative methods under different methodological assumptions and variable values in an effort to counteract methodological limitations, biases, and different perceptions. As a result, it relies on computational experiments to explore conjectures, models (Kwakkel and Pruyt 2013; Tsaples et al. 2017), and datasets (Fraedrich et al. 2009).

In the context of the current paper, the system dynamics model was used to generate different scenarios, and machine learning algorithms were employed to gain insights from the generated data and investigate which levels of the policies performed in a satisfactory way under all conditions. In more detail, the system dynamics model simulated different combinations of several variables for a simulation time of 40 years. These variables were external (a hypothetical policymaker did not have control over them), policy variables (the policies that a hypothetical policymaker wished to test), and target variables (the variables in which the hypothetical policymaker wished to see the effects of the policies). The different value combinations of the variables resulted in 600 different simulation runs (or different scenarios), which in essence were different potential futures of the system under study. However, gaining insights from that many time series might be challenging; hence, to test which of the policy variables affected the target ones, boosting regression (Duffy and Helmbold 2002) was applied; while to obtain specific details on how they affected the target variables, classification and regression trees (CARTs) (Loh 2008) were employed.

Finally, the model was built using vensim (https://vensim.com, accessed on 23 January 2023); a full list of the variables and their relationships can be found in Appendix A.

5. Results

Table 1 below summarizes the variables, their meanings, whether they were considered external or policy variables, and the ranges of their values that were used to generate the different scenarios.

Table 1.

Variables that were used for the computational experimentation.

The “Range of Values” column indicates the range from which each variable sampled a value for each different combination/scenario. This range was determined by the basic value, which was taken from the World Bank. For example, for the variable “birth rate”, the basic value was ~0.008 [https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.CBRT.IN?locations=GR (accessed on 29 November 2021)] thus, we determined the range around that value.

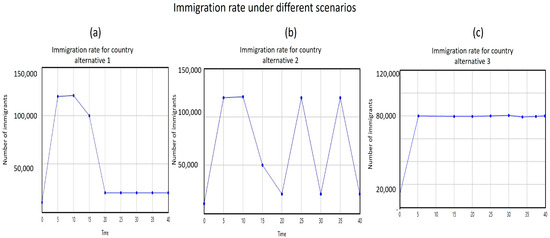

Regarding the “immigration rate for country” variable, it was represented as a time series variable with the purpose of depicting different scenarios for the inflow of immigrants. Figure 4 below illustrates the shape of these series. Figure 4a is meant to represent an initial surge of immigrants for a certain period and a subsequent decrease to “normal values”, Figure 4b represents different surges at different points in the simulation time, and Figure 4c represents a constant inflow of a high number of immigrants for the majority of the simulation time.

Figure 4.

Different migration rates for the computational experiments. (a) for the first scenario, the migration rate increases more than 100,000 people in the first years of the simulation time, followed by a decrease and after year 20 of the simulation time the rate remains constant (b) the migration rate increases for the first 5 years of the simulation time, it remains constant and high for the next 5 years and then falls (c) for the third scenario, the migration rate increases during the first 5 years of the simulation time and then remains constant. However, the rate follows an oscillatory behavior with high peaks and deep lows until the end of the simulation time.

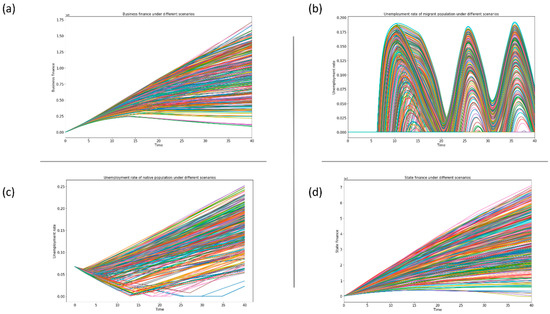

The results for the business finances, unemployment rate of the immigrant population, unemployment rate of the native population, and state finances of the different scenarios are illustrated in Figure 5a–d, respectively.

Figure 5.

Plots for the target variables under the simulated scenarios. (a) The figure illustrates the results for Business Finances under the different scenarios. (b) The figure illustrates the unemployment rate for the migrant population throughout the simulation time (c) The figure illustrates the unemployment rate for the native population under the different scenarios (d) The figure illustrates the state finance under all the different scenarios for the simulation time.

In Figure 5, the x-axes depict the simulation time, which lasted for 40 years, while the y-axes depict the variables that were mentioned above. As can be observed, the scenarios generated diverse time series/behaviors; nonetheless, some general conclusions could be drawn. For example, Figure 5a, which illustrates the business finances, shows that regardless of the policy applied, business seemed not to be affected negatively whether they employed native or migrant workers and even if it was assumed that migrants were remunerated slightly less than the natives. This occurred because the increased overall population (natives and immigrants) created an expanded market that increased the demand for the business products. Furthermore, the expanded potential workforce allowed businesses to obtain available labor, and thus no delays occurred in their production. However, as was mentioned above, the economic model was generic, and hence no internal processes were represented in the model, which could worsen the business outlook. However, the current model did indicate that public–private collaborations on the workforce (both for native and migrant populations) did not seem to be the cause of business failures.

The situation was similar for the state finances (Figure 5d). Only a handful of the scenarios forced the state finances to reach levels of 0 or negative values. This could be attributed to the increased population, which constituted a larger taxation base for the state, in combination with the increased production value, which also generated income for the state through taxation. For the state finances, the same assumptions applied as those of the businesses, meaning that the model was generic and lacked representation of the processes, complexities, and nuances that exist in state management. However, and again similar to the business case, the model indicated that when properly designed and applied in combination with a robust taxation system, public–private cooperation did not seem to be the cause of a financial burden for the state.

Regarding the unemployment rate of the native population (Figure 5c), there were a few scenarios in which it has low values, while in the majority of the scenarios, the unemployment rate of the native population increased throughout the simulation time. Consequently, policies that attempted to increase the employability of immigrants were to the detriment of the native population, which was not unexpected because an increased productivity by migrants was more attractive to businesses because they could produce the same products at lower wages (assuming that wages for migrants were slightly lower than those of the native population). However, the simulation indicated that there were situations in which this did not apply.

Finally, the unemployment rate of the immigrant population had a behavior that was driven by the inflows during the simulation time (Figure 5b). Thus, when waves of immigrants entered the country, time delays increased their unemployment because they could not enter the workforce instantaneously. However, the duration of this rate increase depended on the application of the policies, and there were scenarios in which it reached 0.

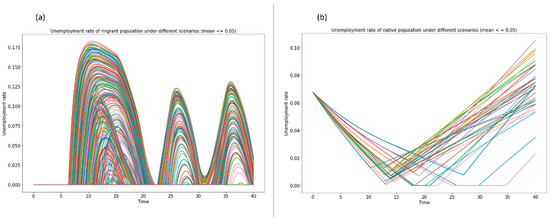

To obtain better insights into how the unemployment rates of both the native and immigrant populations behaved during the simulation time, the scenarios were sampled and only those in which the unemployment rates had a mean lower than 0.05 for the simulation time were kept. The simulated results, which are shown in Figure 6, indicated that there were far fewer scenarios in which the unemployment rate of the native population was at lower levels than those of the rate of the immigrant population.

Figure 6.

Unemployment rates for the immigrant (a) and native (b) populations with a mean value lower than 0.05.

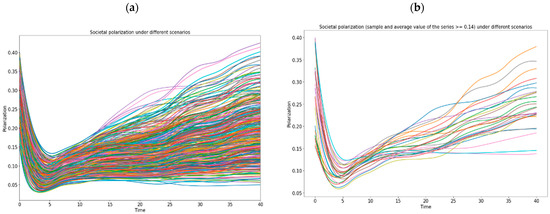

The last target variable to be studied was the one that depicted societal polarization. Figure 7a below illustrates the behavior of the variable in all scenarios, while Figure 7b only represents those scenarios in which the series had a mean value of higher than 0.14 (the mean for all scenarios).

Figure 7.

Societal polarization: (a) all scenarios; (b) scenarios with a mean series value above 0.14.

In general, the variable had different behaviors: regardless of its initial value, the variable dropped to its lowest levels for all scenarios just before year 5 of the simulation time, which was attributed to the initiation of the inflow of immigrants to the country. Further, there were scenarios in which it remained almost constant, scenarios in which it increases slightly, and scenarios in which the value at the end of the simulation time surpassed the initial level. Figure 6b illustrates those scenarios in which the mean of the series was above 0.14. As can be observed, this included scenarios in which the variable’s values dropped to a low value and then increased dramatically and others in which the values were almost constant around the mean. Consequently, to gain further insights, more analyses were required.

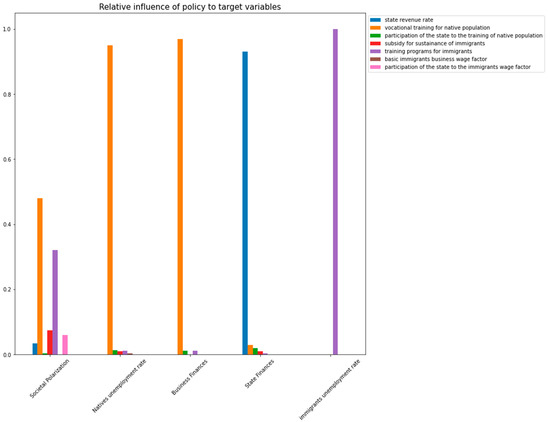

For that reason, machine learning algorithms (boosting regression and CART) were deployed to analyze the behavior of the target variables at the halfway point of the simulation time (year 20) because at that point there was already an inflow of immigrants and the model had generated results that depended more on its structure and less on the initial values of the variables. Both machine learning methods were developed with the help of the scikit-learn module (Pedregosa et al. 2011) of Python.

The results of the boosting regression algorithm are depicted in Figure 8. For societal polarization, the most influential variables were the “vocational training for native population” and “training programs for immigrants”, while there was only a small influence by all the other policy variables. On the contrary, all other target variables were influenced for the largest part by one variable: “vocational training for native population”. This was not unexpected because extra vocational training resulted in higher productivity, thus there were more opportunities for employment for the native population and more opportunities for revenues for the businesses. “State finances” were influenced by the “State revenue rate”, which was not unexpected; however, this revealed an important insight into any potential public–private cooperation: it will have no discernible effect on the state finances as long as there is a robust taxation regime. Finally, the “immigrants’ unemployment rate” was influenced by the “training programs for immigrants”, which indicated that any path toward integration must pass through training and vocational programs in order to increase the productivity and employability perspectives of the immigrant population.

Figure 8.

Relative influence of the policy variable on the target variables.

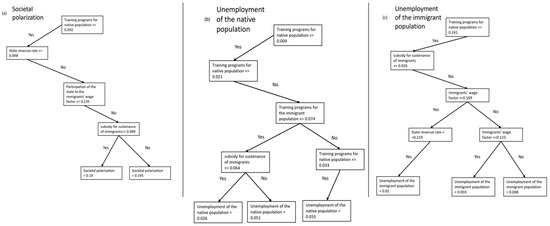

The boosting regression algorithm generated the relative influence of the policy variables; however, to understand how this influence affected the target variables, CART trees were generated. Figure 9a–c below illustrates the branches of the resulting trees for three target variables: societal polarization, the unemployment rate for the native population, and the unemployment rate for the immigrant population, respectively.

Figure 9.

Branches from the CART trees for (a) societal polarization, (b) unemployment rate for the native population, and (c) unemployment rate for the immigrant population.

For the variable “Societal polarization”, the branch had the following structure: if the value of the “Training programs for native population” was lower than 0.092 and the “State revenue rate” was not lower than 0.098, the branch arrived at the node “Participation of the state to the immigrants’ wage factor”. From there, if the value was not lower than 0.23 and the “subsidy for sustenance of immigrants” was lower than 0.089, then the value of “Societal polarization” was equal to 0.19. On the other hand, if the “subsidy for sustenance of immigrants” was larger than 0.089, then “Societal polarization” was equal to 0.195. Consequently, a combination of an insufficient number of training programs for the native population with relatively high taxation and participation of the state in the wages and sustenance for immigrants increased the societal polarization.

For the unemployment rate of the native population (Figure 9b), the variable that dominated the branch was the “training programs for native population”, which corroborated the results from the boosting regression algorithm. On the other hand, for the variable of “unemployment of the immigrant population”, an increased participation of the state in the sustenance of the unemployed immigrants in combination with low taxation led to the lowest percentage of unemployment (equal to 0.02) despite the fact that the participation of the state in the wages of the immigrants was low. Hence, to obtain low unemployment rates for immigrants did not solely depend on direct policies but also on how the state supported the surrounding community of unemployed immigrants (either through provisions or through lower taxation) to allow employed immigrants to support their community.

6. Discussion

Table 2 below summarizes the results of the exploratory analysis of the current paper and makes comparisons with the indicative results from the literature regarding how the proposed policies performed.

Table 2.

Conclusions and comparisons with the results from the literature.

Greece endured three crises during a decade. The financial crisis, the migrant crisis, and the pandemic crisis have all had an impact on the country’s labor market and the status of its labor force (for both native and migrant backgrounds). Societal polarization and social unrest have been obvious consequences of the aforementioned crisis. In particular, migrant employees had to change their sector of employment during and after the recession (Blouchoutzi 2019, p. 143). In addition, the migrant labor force has been more vulnerable to losing job placements and their repossession (Blouchoutzi 2019). However, intersectoral mobility probably will not be an alternative for the time being for the migrant population in the country. Labor market transitions in the COVID-19 era have included increased labor demand for high-skilled professions, which are not a match for the newcomers either because they are low-skilled or because they usually lack the necessary documentation to prove their qualifications.

The contribution of the private sector could facilitate the current public efforts to integrate the migrant population in the Greek labor market. Following the example of private-sector engagement in other countries and humanitarian crises, private-sector companies could offer their expertise, funding sources, or employment strategies to build a win–win business case. The public authorities should enhance and motivate the commitment of the private sector either in a cooperative public–private scheme or on an autonomous basis. Following an exploratory systems dynamics study, this paper outlined the importance of vocational training for migrant labor market integration, the necessity for concurrent training programs for the native population, the precondition of a robust taxation system for public–private cooperation without negative effects on state finances, and the indirect support of migrant communities. This work can serve as a basis for future research works.

In this context, there are alternative methods to contribute to migrant labor market integration apart from employment creation. Employment opportunities increase with innovative methods and digital tools for skill assessment, job matching, training, and educational or employability courses. Seizing on the private sector’s experience and understanding the local labor market needs in this direction could play a crucial role in migrant integration. Last but not least, social cooperatives have been successful, but not wide-ranging examples implemented in Greece that offered employment to the migrant population.

Furthermore, there are other factors that explain and cause societal polarization. However, we based our model on the model by Bossel (2007), which we believe captured the essence and dynamic behavior of such a qualitative phenomenon without having to rely on extensive data sources and fuzzy values.

Future directions of this research include the development of a more elaborate economic model and the inclusion of different countries, as well as the determination of how population movements can occur among those countries and how that movement could affect potential policies. Furthermore, the inclusion of additional countries and the design of additional policies and a more elaborate economic model could assist in using more concrete data from appropriate sources and comparing the results with those of the current paper. In addition, the generic substructures (for example, the one that explains societal polarization) could be expanded with additional variables. Moreover, apart from the generation of scenarios with different values of the variables that were presented in Table 1, the model could be expanded with different structures and different combinations of causal relationships. Despite the computational intensity that will result from such an inclusion, this addition could further test the validity and robustness of the current results. Finally, the development of a graphical user interface could assist policymakers and researchers in adapting and assessing different scenarios and policies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and D.M.; Data curation, G.T.; Formal analysis, A.B. and G.T.; Funding acquisition, D.M. and J.P.; Investigation, A.B. and D.M.; Methodology, G.T. and J.P.; Project administration, A.B.; Resources, A.B. and D.M.; Software, J.P.; Supervision, J.P.; Validation, A.B., G.T., D.M. and J.P.; Visualization, G.T. and J.P.; Roles/Writing—original draft, A.B. and G.T.; Writing—review & editing, D.M. and J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the H2020 project “MigrAtion Governance and AsYlum Crises—MAGYC”, grant number 822806.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Macedonia (Decision No. 7/7-1-2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated from the interviews during the current study are not publicly available following the General Data Protection Regulation but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data from the results of the simulation model are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The full list of variables and their functions is presented below.

(1) Basic immigrants business wage factor = 0.2

(2) Birth rate = 0.00865

(3) Births = Population × birth rate

(4) Business debt = INTEG (business debt increase, 0)

(5) Business debt increase = IF THEN ELSE (Business Finances < 0, − Business Finances/time unit, 0)

(6) Business expenses = business wages + business expenses for training of native population + business expenses for training of immigrants

(7) Business expenses for training of immigrants = immigrant employment in production × immigrants wage index × training programs for immigrants × (1 − participation of the state to the training of immigrants)

(8) Business expenses for training of native population = Native employment in production × general wage index × vocational training for native population − (1 − participation of the state to the training of native population)

(9) Business Finances = INTEG (business revenue income-business expenses, 0)

(10) Business revenue income = sales value + business debt increase

(11) Business wages = (general wage index × Native employment in production × natives business wage factor) +( immigrant employment in production × immigrants wage index × immigrants business wage factor)

(12) Death rate = 0.00875

(13) Deaths = Population × death rate

(14) Demand value = IF THEN ELSE (total population ≥ 11,000,000, total population × 0.55, total population × 0.45)

(15) Effect of immigrants on the increase of polarization = WITH LOOKUP (immigrants in the country, ([(0;0)–(10;10)], (0;0.1), (100,000;0.1), (200,000;0.2), (500,000;0.45), (750,000;0.5), (1,000,000;0.65))

(16) Effect of societal polarization on choice of employees = WITH LOOKUP (Societal polarization, ([(0;0)–(10;10)], (0;0.5), (0.1;0.6), (0.2;0.65), (0.3;0.75), (0.4;0.75), (0.5;0.8))

(17) Effect of unemployment on societal polarization = WITH LOOKUP (natives unemployment rate, ([(0;0)–(10;10)], (0;0.1), (0.1;0.15), (0.2;0.35), (0.3;0.5), (0.5;0.75))

(18) FINAL TIME = 40 [The final time for the simulation].

(19) Forward immigration rate = WITH LOOKUP (immigrants unemployment rate, ([(0;0)–(10;10)], (0;0.05), (0.1;0.1), (0.2;0.2), (0.3;0.35), (0.4;0.6), (0.5;0.7))

(20) General wage index = Productivity

(21) Immigrant employment in production = INTEG (−immigrant jobs reduction, 250,000)

(22) Immigrant jobs reduction = IF THEN ELSE(relative production surplus < 0.1, (1 − effect of societal polarization on choice of employees) × natives job reduction rate × relative production surplus × max(potential immigrant labor force-immigrant employment in production,0), (1 − effect of societal polarization on choice of employees) × 0.1 × natives job reduction rate × immigrant employment in production)

(23) Immigrants becoming citizens = total naturalizations

(24) Immigrants business wage factor = basic immigrants business wage factor × (1 − participation of the state to the immigrants wage factor)

(25) Immigrants coming in the country = immigration rate for country (Time)

(26) Immigrants in need of assistance = max(0, immigrants in the country − immigrant employment in production)

(27) Immigrants in the country = INTEG (immigrants coming in the country − immigrants leaving the country − naturalizations, 120,000)

(28) Immigrants leaving the country = immigrants in the country × forward immigration rate

(29) Immigrants productivity = INTEG (immigrants productivity increase, 0.5)

(30) Immigrants productivity increase = immigrants productivity increase rate × Immigrants productivity × (1 − Immigrants productivity/productivity limit)

(31) Immigrants productivity increase rate = WITH LOOKUP (1 + training programs for immigrants, ([(0;0)–(10;10)], (1;0.05), (1.05;0.1), (1.1;0.2), (1.2;0.25), (1.3;0.3), (1.4;0.37), (1.5;0.4))

(32) Immigrants unemployment rate = max(0,(potential immigrant labor force-immigrant employment in production)/potential immigrant labor force)

(33) Immigrants wage index = Immigrants productivity

(34) Immigration rate for country a([(0;0)–(1010)], (0;10,000), (5;120,000), (10;120,000), (15;100,000), (20;20,000), (25;20,000), (30;20,000), (35;20,000), (40;20,000))

(35) Immigration rate for country b([(0;0)–(10;10)], (0;10,000), (5;120,000), (10;120,000), (15;50,000), (20;20,000), (25;120,000), (30;20,000), (35;120,000), (40;20,000))

(36) Immigration rate for country c[(0;0)-(10,;0)],(0;10,000),(5;80,000),(10;80,000),(15;80,000),(20;80,000),(25;80,000),(30;80,000),(35;80,000),(40;80,000)

(37) Initial societal polarization = 0.3

(38) INITIAL TIME = 0 The initial time for the simulation.

(39) Max societal polarization = 1

(40) Migration rate = 0.004

(41) Native employment in production = INTEG (−native jobs reduction, 3,000,000)

(42) Native jobs reduction = IF THEN ELSE (relative production surplus < 0, effect of societal polarization on choice of employees × natives job reduction rate × max(potential native labor force-Native employment in production, 0) × relative production surplus, effect of societal polarization on choice of employees × 0.1 × natives job reduction rate × Native employment in production)

(43) Native population becoming immigrants = Population × migration rate

(44) Natives business wage factor = 0.25

(45) Natives job reduction rate = 0.11

(46) Natives unemployment rate = max(0, (potential native labor force-Native employment in production)/potential native labor force)

(47) Naturalization rate = 0.01

(48) Naturalizations = immigrants in the country × naturalization rate

(49) Participation of the state to the immigrants wage factor = 0

(50) Participation of the state to the training of immigrants = 0

(51) Participation of the state to the training of native population = 0

(52) Pct Percentage of immigrants in working age = 0.4

(53) ) Pct Percentage of native adult population that can work = 0.45

(54) ) Pct Percentage of native population not working in public sector = 0.65

(55) Polarization decrease = Societal polarization/time to overcome fear of immigrants

(56) Polarization increase = effect of immigrants on the increase of polarization × effect of unemployment on societal polarization × (1 − Societal polarization/max societal polarization)

(57) Population = INTEG (births + immigrants becoming citizens − deaths-native population becoming immigrants) 11,000,000

(58) Potential immigrant labor force = immigrants in the country × pct of immigrants in working age

(59) Potential native labor force = Population × pct of native adult population that can work × pct of native population not working in public sector

(60) Product value = Native employment in production × Productivity + Immigrants productivity × immigrant employment in production

(61) Productivity = INTEG (productivity increase, 1.5)

(62) Productivity increase = productivity increase rate × Productivity × (1 − Productivity/productivity limit)

Productivity Increase Rate × productivity × (1 − productivity/Productivity Limit

(63) Productivity increase rate = WITH LOOKUP (vocational training for native population, ([(0;0)–(10;10)], (0;0.01), (0.1;0.1), (0.2;0.22), (0.25;0.25), (0.3;0.33), (0.35;0.4), (0.4;0.425), (0.5;0.5))

(64) Productivity limit = 4

(65) Relative production surplus = (product value − demand value)/demand value

(66) Sales value = IF THEN ELSE (demand value > product value, product value, demand value)

(67) Societal polarization = INTEG (polarization increase − polarization decrease, initial societal polarization)

(68) State debt = INTEG (state debt increase, 0)

(69) State debt increase = IF THEN ELSE (State finances < 0, − State finances/time unit, 0)

(70) State expenses = state expenses for immigrants sustenance + state subsidies for immigrant wages + state expenses for training of native population + state expenses for training of immigrants

(71) State expenses for immigrants sustenance = immigrants in need of assistance × immigrants wage index × subsidy for sustenace of immigrants

(72) State expenses for training of immigrants = immigrant employment in production × immigrants wage index × training programs for immigrants × participation of the state to the training of immigrants

(73) State expenses for training of native population = Native employment in production × wage index × vocational training for native population × participation of the state to the training of native population

(74) State finances = INTEG (state revenue income − state expenses, 0)

(75) State revenue income = business revenue income × state revenue rate + state debt increase

(76) State revenue rate = 0.24

(77) State subsidies for immigrant wages = immigrant employment in production × basic immigrants business wage factor × participation of the state to the immigrants wage factor × immigrants wage index

(78) Subsidy for sustenance of immigrants = 0.15

(79) TIME STEP = 0.125 Units: Year [0,?] The time step for the simulation.

(80) Time to overcome fear of immigrants = 1

(81) Total naturalizations = naturalizations

(82) Total population = Population + immigrants in the country

(83) Training programs for immigrants = 0

(84) Vocational training for native population = 0

References

- Agrotypos. 2021. Refugee and Migrant Workers Trained by the AUA Go To the Fields. March 10. Available online: https://www.agrotypos.gr/thesmoi/ekpaidefsi-erevna/sta-chorafia-pane-ergates-prosfyges-kai-metanastes-ekpaidevmenoi-apo-to (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Andersson, Joona P. 2019. Labour Market Policies: What Works for Newly Arrived Immigrants? In Integrating Immigrants into the Nordic Labour Markets. Edited by Lars Calmfors and Nora Sánchez Gassen. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers. [Google Scholar]

- Armenia, Stefano, and Georgios Tsaples. 2018. Individual Behavior as a Defense in the “War on Cyberterror”: A System Dynamics Approach. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 41: 109–32. [Google Scholar]

- Armenia Stefano, Georgios Tsaples, and Camillo Carlini. 2018. Critical Events and Critical Infrastructures: A System Dynamics Approach. In International Conference on Decision Support System Technology. Cham: Springer, pp. 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Auping, L. Willem, Erik Pruyt, and Jan H. Kwakkel. 2015. Societal ageing in the Netherlands: A robust system dynamics approach. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 32: 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagavos, Christos, Nikos Kourachanis, Konstantina Lagoudakou, Katerina Xatzigiannakou, and Paraskevi Touri. 2019. Greece. In Integration of Migrants, Refugees and Asylum Seekers: Policy Barriers and Enablers SIRIUS WP3 Integrated Report. Edited by Ilona Bontenbal and Nathan Lillie. SIRIUS [D3.2]. Available online: https://www.sirius-project.eu/ (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Bankes, Steve, Warren E. Walker, and Jan H. Kwakkel. 2013. Exploratory modeling and analysis. In Encyclopedia of operations Research and Management Science. Boston: Springer, pp. 532–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bisong, Amanda, and Anna Knoll. 2020. Mapping Private Sector Engagement along the Migration Cycle. Maastricht: The European Centre for Development Policy Management. [Google Scholar]

- Blouchoutzi, Anastasia. 2019. Essays on the Macroeconomic Implications of International Migration. Ph.D. thesis, University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Blouchoutzi, Anastasia, and Christos Nikas. 2018. Unemployment of native Greeks and migrants in a country in deep recession: The case of Greece. In International Conference on International Business 2017 & 2018 Proceedings. Edited by Aristeidis Bitzenis and Kontakos Panagiotis. Thessaloniki: University of Macedonia, pp. 445–66. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, Arjen, Paul ’t Hart, Eric Stern, and Bengt Sundelius. 2005. The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership Under Pressure. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bossel, Hartmut. 2007. System Zoo 3 Simulation Models: Economy, Society, Development. Schleswig-Holstein: BoD–Books on Demand, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Bulman, Tim. 2020. Rejuvenating Greece’s Labour Market to Generate more and Higher-Quality Jobs. Economics Department Working Papers No. 1622. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Butschek, Sebastian, and Thomas Walter. 2014. What active labour market programs work for immigrants in Europe? A meta-analysis of the evaluation literature. IZA Journal of Migration 3: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, David, Jochen Kluve, and Andrea Weber. 2010. Active labour market policy evaluations: A meta-analysis. The Economic Journal 120: F452–F477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, José César Lenin Navarro, José Carlos Rodríguez, and James W. Wilkie. 2011. A System Dynamics Model of Employment and Migration for Mochoacán. PROFMEX Journal Mexico and the World 17: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, Jens, Eskil Heinesen, Hans Hummelgaard, Leif Husted, and Michael Rosholm. 2009. The effect of integration policies on the time until regular employment of newly arrived immigrants: Evidence from Denmark. Labour Economics 16: 409–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, Phillip. 2020. Fast Facts on How Greeks See Migrants as Greece-Turkey Border Crisis Deepens. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/10/fast-facts-on-how-greeks-see-migrants-as-greece-turkey-border-crisis-deepens/ (accessed on 28 March 2020).

- Di Bella, Jose, Alicia Grant, Shannon Kindornay, and Stephanie Tissot. 2013. Mapping Private Sector Engagements in Development Cooperation. Ottawa: The North South Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriadi, Angeliki, and Antonia-Maria Sarantaki. 2018. The Refugee ‘Crisis’ in Greece: Politicisation and Polarisation Amidst Multiple Crises. Ceaseval Research on the Common European Asylum System (11). Available online: http://ceaseval.eu/publications (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Dos Reis, Andre Alves, Khalid Koser, and Mariah Levin. 2017. Private Sector Engagement in the Global Compact on Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration. In Ideas to Inform International Cooperation on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration. Edited by Maries McAuliffe and Michele Klein Solomon (Conveners). Geneva: IOM. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, Nigel, and David Helmbold. 2002. Boosting methods for regression. Machine Learning 47: 153–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, Mario Arturo Ruiz. 2011. Policy modeling: Definition, classification and evaluation. Journal of Policy Modeling 33: 523–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2016. European Semester: Thematic Factsheet—Active Labour Market Policies—2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/european-semester_thematic-factsheet_active-labour-market-policies_en_0.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- European Commission. 2017. Public Employment Services (PES) Initiatives around Skills, Competences and Qualifications of Refugees and Asylum Seekers. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]