The Influence of Different Leadership Styles on the Entrepreneurial Process: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Leadership and Its Different Styles

2.2. Entrepreneurial Process

2.3. The Influence of Leadership on the Entrepreneurial Process

3. Methodology

3.1. Type of Study and Case Selection

3.2. Data-Collecting Instrument

3.3. Data Analysis

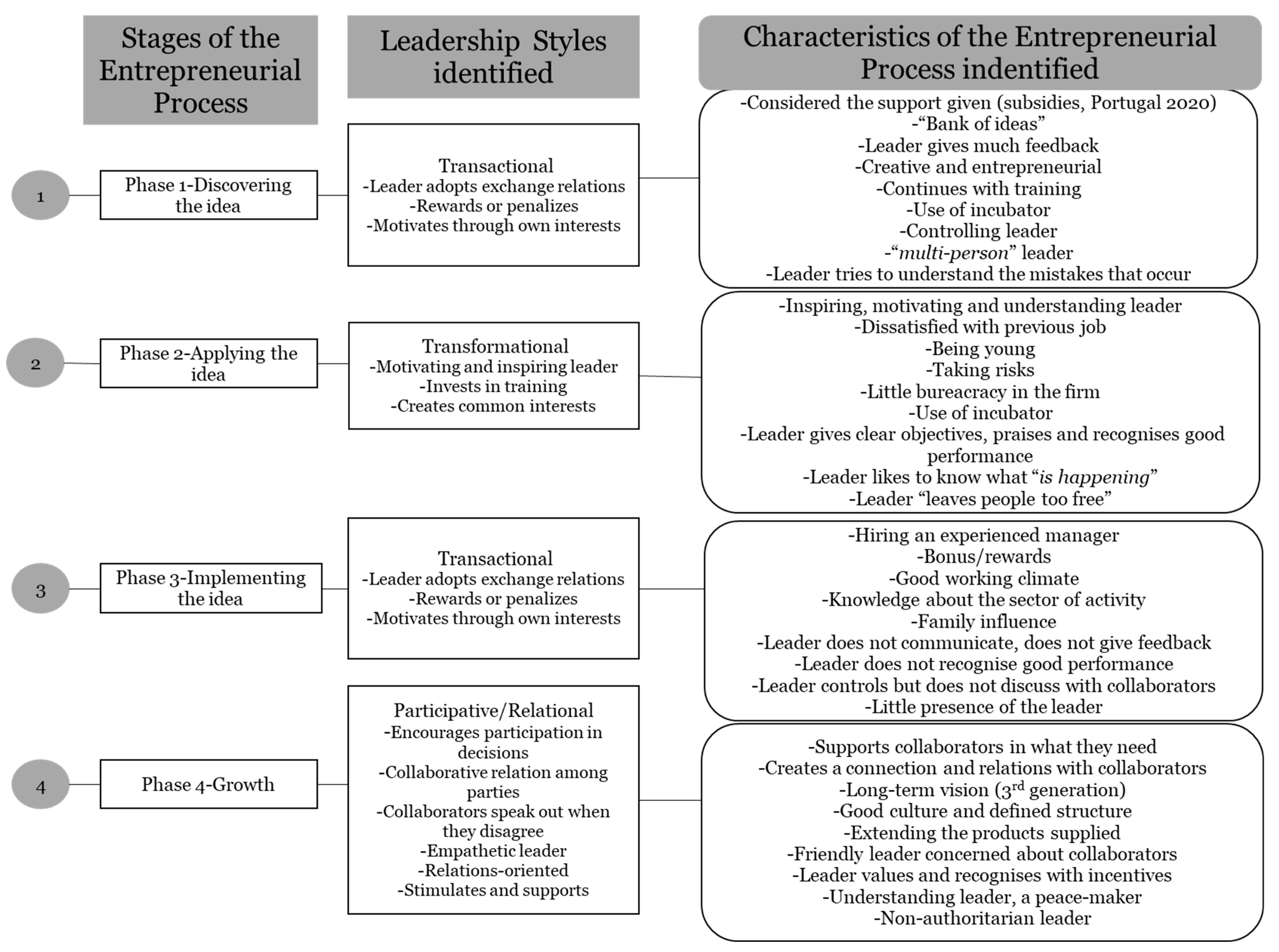

4. Presentation of the Cases and Their Discussion

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Script to Leaders

- (1)

- General characterisation of the SME and the leader:

- -Sector of activity -No. of Employees -Juridical Form -No. Partners

- -Localisation -Year of Creation -Initial Idea (year)

- -Gender -Age -Education -Position

- (2)

- SME in the different phases of the entrepreneurial process:

- How it came about and how the idea and opportunity in the market were identified. Was it something innovative? You didn’t think the idea was risky?

- Have you had any experience and/or training in this business area?

- Did the idea come about as a form of personal fulfilment, or because you already knew someone who works in this area?

- Did you already have and/or knew any model of success that inspired you? (friend or family)?

- Did you just have an idea of what you wanted to do/create, or did several ideas come up? From this group, did you choose the one that was most successful, or the one you liked the most? Did you apply them in practice?

- Did you present the idea to potential consumers to observe their reaction? And did you even share with friends or family?

- Was your idea based on existing policies and support?

- Did you compare your idea with competing companies?

- Did the idea come about only by you, or was it discussed with friends/family?

- Do you want to communicate business objectives to your workers?

- Do you plan to tailor each employee to their job?

- Do you think about taking into account the suggestions for improvement given by workers for the performance of their tasks?

- How is characterised as a leader (confident, optimistic, absent, controlling, attentive, motivating, pessimistic, concerned)?

- What do you consider more important: employee satisfaction or the achievement of the company’s objectives? Why?

- How do you plan to motivate your workers? (rewards, …) And how will it act in a situation, when the worker has a lower than expected level of performance (supports, penalises, is not interested)?

- Would you like your workers to mention when they are in the organisation’s mistakes? And if the errors are directed to the direction, how do you act?

Appendix B. Interview Script to Followers

- (1)

- General Characterisation of the Followers:

- -Gender -Age -Education -Position -Year of entry into the company

- (2)

- General Questions:

- Tell me a little about your history in this company.

- Did your leader accept your suggestions when the company was created? And these days?

- How would you describe your leader? (confident, motivating, controlling, pessimistic, attentive, concerned, absent, optimistic)

- Does the leader communicate the objectives and give freedom to achieve these or is he controlling?

- Do you participate in the decision-making process in the company?

- Do you feel recognised/appreciated for the work you do?

- What is the reaction of the leader when his performance is excellent? And when you make a mistake, what’s his reaction?

- Does the leader reward you or penalise you according to your performance?

- Do you consider your leader a close person (friend) or just your boss?

- Do you feel motivated and inspired by your leader?

- Does the support that your leader give you, encourage you to perform your duties better?

- How do you feel that your leader fails the workers?

- Does the leader give you a chance to participate in training in order to improve your performance and curriculum?

- Do you feel that you can comment, when you look at any mistakes in the company, or are you afraid of the consequences?

- Feel that you can share with your leader your own ideas, regarding new products and services or changes in the company

References

- Antonakis, John, and Erkko Autio. 2007. Entrepreneurship and Leadership. The Psychology of Entrepreneurship. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, Rute Maria Fernandes. 2008. A criação de empresas industriais: Organismos de apoio à atividade empreendedora no concelho da Covilhã. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Universidade da Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, Luiz Fernando Gonçalves da Silva, Kátya Alexandrina Matos Barreto Motta, Ivone Felix de Souza, and António Augusto Teixeira da Costa. 2019. Perfil de Liderança: Estilo transformacional, transacional e laissez-faire. R-LEGO-Revista Lusófona de Economia e Gestão das Organizações 9: 45–73. [Google Scholar]

- Armond, Álvaro Cardoso, and Vânia Maria Jorge Nassif. 2009. The leadership as element of the entrepreneurial behavior: An exploratory study. RAM-Revista de Administração Mackenzie 10: 77–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, Bruce J., and B. M. Bass. 2004. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire, 3rd ed. Palo Alto: Mind Garden, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, Bruce J., Bernard M. Bass, and Dong I. Jung. 1999. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 72: 441–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barañano, A. M. 2008. Métodos e Técnicas de Investigação em Gestão, 1st ed. Lisboa: Edições Sílabo. [Google Scholar]

- Barracho, Carlos. 2012. Liderança em Contexto Organizacional. Lisboa: Escolar Editora. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, Bernard M. 1999a. On the taming of charisma: A reply to Janice Beyer. Leadership Quaterly 10: 541–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, Bernard M. 1999b. Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 8: 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, Bernard M., and Ralph Melvin Stogdill. 1990. Bass & Stogdill Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research and Managerial Applications, 3rd ed. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, Bernard M., and Ruth Bass. 2008. The Bass Handbook of Leadership. Theory, Research and Managerial Applications, 4th ed. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis, Warren. 2007. The challenges of leadership in the modern world. American Psychologist 62: 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamini, Cecília Whitaker, and Rafel Tassinari. 2008. Psicopatologia do Comportamento Organizacional: Organizações Desorganizadas, Mas Produtivas. São Paulo: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, Nadeem, Ghulam Murta Maitlo, Naveed Shaikh, Muhammad Aamir Hashmi, and Faiz M. Shaikh. 2012. The impact of Autocratic and Democratic Leadership Style on Job satisfaction. International Business Research 5: 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhave, Mahesh P. 1994. A process model of entrepreneurial venture creation. Journal of Business Venturing 9: 223–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, Barbara. 1988. Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. The Academy of Management Review 13: 442–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, Isabel, Eva Martínez, and Jorge Matute. 2019. Transformational leadership and employee performance: The role of identification, engagement and proactive personality. International Journal of Hospitality Management 77: 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calaça, Pedro Alessandro, and Fabio Vizeu. 2015. Revisitando a perspetiva de James MacGregor Burns: Qual é a ideia por trás do conceito de liderança transformacional? Cadernos EBAPE 13: 121–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canda, António Pedro Boas. 2013. O processo de empreendedorismo em empresas de base tecnológica: Uma abordagem suportada em estudo de caso. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias, Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, Luísa, and Teresa Costa. 2015. Empreendedorismo-Uma Visão Global e Integradora, 1st ed. Lisboa: Edições Sílabo, Lda. [Google Scholar]

- Chammas, Cristiane Benedetti, and José Mauro da Costa Hernandez. 2019. Comparing transformational and instrumental leadership: The influence of different leadership styles on individual employee and financial performance in Brazilian startups. Innovation & Management Review 16: 143–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Simon C. H. 2019. Participative leadership and job satisfaction: The mediating role of work engagement and the moderating role of fun experienced at work. Leadership Organization Development Journal 40: 319–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., and I. Chen. 2007. The Relationships between personal traits, leadership styles and innovative operation. Paper presented at the 13th Asia Pacific Management Conference, Melbourne, Australia, November 18–20; pp. 420–25. [Google Scholar]

- Comeche, Jose M., and Joaquín Loras. 2010. The Influence of Variables Attitude on Collective Entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 6: 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, Miguel Pina, Arménio Rego, Rita Campos Cunha, Carlos Cabral-Cardoso, and Pedro Neves. 2007. Manual de Comportamento Organizacional e Gestão, 6th ed. Lisboa: Editora RH. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Barreto, Leilianne Michelle Trindade, Angeli Kishore, Germano Glufke Reis, Luciene Lopes Baptista, and Carlos Alberto Freire Medeiros. 2013. Cultura Organizacional e liderança: Uma relação possível? Revista Administração 48: 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, David V., and Michelle M. Harrison. 2007. A multilevel identity-based approach to leadership development. Human Resource Management Review 17: 360–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Sant’Anna, Anderson, Luccas Santin Padilha, Matias Trevisol, Eliane Salete Filippim, and Fernando Fantoni Bencke. 2017. Liderança e Sustentabilidade: Contribuições de estudos sobre dinâmicas socio espaciais de reconversão e requalificação de Funções Económicas. RACE: Revista de Administração, Contabilidade e Economia 16: 1133–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRue, D. Scott, and Susan J. Ashford. 2010. Who will lead and who will follow? A social process of leadership identity construction in organizations. Academy of Management Review 35: 627–47. [Google Scholar]

- Derue, D. Scott, Jennifer D. Nahrgang, Ned ED Wellman, and Stephen E. Humphrey. 2011. Trait and behavioural theories of leadership: An integration meta and analytic test of their relative validity. Personnel Psychology 64: 7–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Maria Aparecida Muniz Jorge, and Renata Simões Guimarães Borges. 2015. Estilos de liderança e desempenho de equipes no setor público. READ-Revista Eletrônica de Administração 80: 200–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornelas, José. 2008. Empreendedorismo: Transformando ideias em negócios, 3rd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, Peter. 1998. Inovação e Espírito Empreendedor. São Paulo: Pioneira. [Google Scholar]

- Dubrin, Andrew J. 2001. Leadership: Research Findings, Practice, Skills, 3rd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Felix, Claudia, Sebastian Aparicio, and David Urbano. 2018. Leadership as a driver of entrepreneruship: An international exploratory study. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 26: 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, Mario, and Heiko Haase. 2017. Collective entrepreneurship: Employees’ perceptions of the influence of leadership styles. Journal of Management & Organization 23: 241–57. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, Mário, and Pedro Gonçalo Matos. 2015. Leadership styles in SMEs: A mixed-method approach. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 11: 425–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, Franco. 2016. Fundamentals of Leadership Development. Master’s thesis, Executive master’s in leadership presentation. Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfi, Franco, and Seth Stone. 2018. Leadership, Leadership Styles, and Servant Leadership. Journal of Management Research 18: 261–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gieure, Clara, Maria del Mar Benavides-Espinosa, and Salvador Roig-Dobón. 2020. The entrepreneurial process: The link between intentions and behavior. Journal of Business Research 112: 541–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, Daniel, Richard Boyatzis, Annie McKEE, and Edgar Rocha. 2002. Os novos líderes—A inteligência emocional nas organizações. Lisboa: Gradiva. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, Heiko, and Mário Franco. 2020. Leadership and collective entrepreneurship: Evidence from the health care sector. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 33: 368–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisrich, R., and M. Peters. 1998. Entrepreneurship: Starting, Developing and Managing a New Enterprise, 4th ed. Chicago: Irwin. [Google Scholar]

- Hmieleski, Keith M., Michael S. Cole, and Robert A. Baron. 2012. Shared authentic leadership and new venture performance. Journal of Management 38: 1476–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, Robert J. 1971. A path goal theory of leader effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly 16: 321–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Stanley Y. B., Ming-Way Li, and Tai-Wei Chang. 2021. Transformational leadership, ethical leadership, and participative leadership in predicting counterproductive work behaviors: Evidence from financial technology firms. Frontiers in Psycholology 12: 658727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxtable-Thomas, Louisa A., Paul D. Hannon, and Steffan W. Thomas. 2016. An investigation into the role of emotion in Leadership Development for Entrepreneurs: A four-interface model. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 22: 510–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, R. Duane, and Michael A. Hitt. 1999. Achieving and maintaining strategic competitiveness in the 21st century: The role of strategic leadership. Academy of Management Executive 72: 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Susan M., and Fred Luthans. 2006. Relationship between entrepreneurs’ psychological capital and their authentic leadership. Journal of Managerial Issues 18: 254–73. [Google Scholar]

- Jesuíno, J. 2005. Processos de Liderança, 4th ed. Lisboa: Livros Horizonte. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Jerome, and William B. Gartner. 1988. Properties of emerging organizations. Academy of Management Review 13: 429–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Patrick J. 1999. Franchising and the choice of self-employment. Journal of Business Venturing 14: 345–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Simon. 2014. Towards a negative ontology of leadership. Human Relations 67: 905–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalique, Muhammad, Nick Bontis, Jamal Abdul Nassir Bin Shaari, and Abu Hassan Md Isa. 2015. Intellectual capital in small and medium enterprises in Pakistan. Journal of Intellectual Capital 16: 224–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinder, Tony, Jari Stenvall, Frédérique Six, and Ally Memon. 2021. Relational leadership in collaborative governance ecosystems. Public Management Review 23: 1612–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, Norris F. 2009. Entrepreneurial Intentions are dead: Long live entrepreneurial intentions. In Understanding the Entrepreneurial Mind, International Studies in Entrepreneurship. Edited by Alan L. Carsrud and Malin Bränback. New York: Springer, pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Soo Hoon, and Poh Kam Wong. 2004. An study of technopreneurial intentions: A career anchor perspective. Journal of Business Venturing 19: 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, Claire M., and Thierry Volery. 2017. Entrepreneurial leadership: Insights and directions. International Small Business Journal 35: 147–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, Robert G., David V. Day, Stephen J. Zaccaro, Bruce J. Avolio, and Alice H. Eagly. 2017. Leadership in Applied Psychology: Three Waves of Theory and Research. Journal of Applied Psychology 102: 434–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, Murray B., and Ian C. MacMillan. 1988. Entrepreneurship: Past Research and future challenges. Journal of Management 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lück, H. 2014. Liderança em Gestão Escolar. Petropólis: Vozes. [Google Scholar]

- Maçães, Manuel Alberto Ramos. 2017. Empreendedorismo, Inovação e Mudança Organizacional. Lisboa: Conjuntura Actual Editora, vol. III. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, Hilka Pelizza Vier, and Vânia Maria Jorge Nassif. 2014. Réplica-Empreendedores: Reflexões sobre conceções históricas e contemporâneas. Revista de Administração Contemporânea 18: 892–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamabolo, Anastacia, and Kerrin Myres. 2020. A systematic literature review of skills required in the different phases of the entrepreneurial process. Small Enterprise Research 27: 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximiano, Antônio César Amaru. 2007. Teoria Geral da administração: Da revolução urbana à revolução digital, 6th ed. São Paulo: Atlas. [Google Scholar]

- Mets, Tõnis. 2020. Exploring the Model of the Entrepreneurial Process. Adelaide: Apresentado em Australian Centre for Entrepreneurship Research Exchange, pp. 709–23. [Google Scholar]

- Moroz, Peter W., and Kevin Hindle. 2012. Entrepreneurship as a Process: Toward Harmonizing Multiple Perspectives. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36: 781–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, Z. A. K. D. A., and I. Khan. 2016. Leadership theories and styles: A literature review. Journal of Resources Development and Management 16: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ndiga, B., C. Mumuikha, F. Flora, M. Ngugi, and S. Mwalwa. 2014. Principals’ Transformational Leadership Skills in Public Secondary Schools: A Case of Teachers’ and Students’ Perceptions and Academic Achievement in Nairobi County, Kenya. American Journal of Educational Research 2: 801–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Alexander, Cristina Neesham, Graham Manville, and Herman H. M. Tse. 2018. Examining the influence of servant and entrepreneurial leadership on the work outcomes of employees in social enterprises. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 29: 2905–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna, Emmanuel, and Lloyd C. Harris. 2000. Leadership Style, Organizational Culture and Performance: Empirical Evidence from UK companies. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 11: 766–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omolayo, Bunmi. 2007. Effect of Leadership Style on job-related tension and psychological sense of community in work organizations: A case study of four organizations in Lagos state, Nigeria. Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology 4: 31780554. [Google Scholar]

- O’Regan, Nicholas, Abby Ghobadian, and Martin Sims. 2005. The link between leadership, strategy, and performance in manufacturing. Journal of Small Business Strategy 15: 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 1990. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pedraja-Rejas, Liliana, Emilio Rodríguez-Ponce, and Juan Rodríguez-Ponce. 2006. Leadership Styles and effectiveness: A study of small firms in Chile. Interciencia 31: 500–4. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, Angela. 2020. Leadership Rebooted: Cultivating Trust with the Brain in Mind. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance 44: 127–43. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, F. L., and M. J. Silva. 2012. Príncipios de Gestão, 1st ed. Lisboa: Edições Sílabo. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, Stephen P. 2007. Comportamento Organizacional. São Paulo: Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, Stephen P., Tim Judge, and Filipe Sobral. 2010. Comportamento Organizacional: Teoria e prática no contexto brasileiro, 14th ed. São Paulo: Pearson Prentice. [Google Scholar]

- Sant’anna, Anderson de Souza, Marly Sorel Campos, and Samir Lotfi. 2012. Liderança: O que pensam os executivos brasileiros sobre o tema? RAM-Revista de Administração Mackenzie 13: 48–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’anna, Anderson de Souza, Reed Eliot NELSON, and Antônio Moreira CARVALHO NETO. 2015. Fundamentos e dimensões da Liderança Relacional. DOM 9: 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk, Charles R., and Charles B. Shrader. 1993. The effects of formal strategic planning on financial performance in small firms: A meta analysis. Entrepreneurship in Theory and Practice 17: 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Tyler. 2015. Does collaboration make any difference? Linking Collaborative Governance to Environmental Outcomes. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 34: 537–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, Scott, and Sankaran Venkataraman. 2000. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review 25: 217–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shook, Christopher L., Richard L. Priem, and Jeffrey E. McGee. 2003. Venture creation and the enterprisingindividual: A review and synthesis. Journal of Management 29: 379–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Rodrigo, Joel Dutra, Elza Fátima Rosa Veloso, and Leonardo Trevisan. 2020. Leadership and performance of Millennial generation in Brazilian companies. Management Research. ahead-of-prin. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, Cynthia Mignonne, and Lonnie R. Morris. 2018. Are women business owners authentic servant leaders? Gender in Management: An International Journal 33: 405–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohmen, Victor S. 2013. Leadership and teamwork: Two sides of the same coin. Journal of IT and Economic Development 4: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Yang, Leo Paul Dana, and Ron Berger. 2021. The entrepreneurial process and online social networks: Forecasting survival rate. Small Business Economics 56: 1171–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, Bahadur Ali, Naimatullah Shah, and Shahnawaz Mangi. 2019. Factors affecting the entrepreneurial leadership in small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) of Pakistan: An empirical evidence. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 15: 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, Ritch L. 2000. The contribution of leadership styles and practices to family and business success. Family Business Review 8: 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, Domingo Ribeiro, and José Manuel Comeche Martínez. 2007. Transmitting the entrepreneurial spirit to the work team in SMEs: The importance of leadership. Management Decision 45: 1102–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, John, Jean Hartley, Jean-Louis Denis, and David Ulrich, eds. 2017. The Routledge Companion to Leadership. New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Taipale-Erävala, Kyllikki, Hannele Lampela, and Pia Heilmann. 2015. Surviving skills in SMEs-Continuous Competence Renewing and Opportunity Scanning. Journal of East-West Business 21: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, Jeffry A. 1999. New Venture Creation, 5th ed. Singapore: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Torikka, Jenni. 2011. Exploring Various Entrepreneurial Processes of the Franchise Training Program Graduates: Empirical Evidence from a Longitudinal Study. Paper presented at the Fifth International Conference on Economics and Management of Networks, Limassol, Cyprus, December 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, Hafiz, B. Shah, F. S. Hassan, and T. Zaman. 2011. The impact of owner psychological factors on entrepreneurial orientation: Evidence from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa-Pakistan. International Journal of Education and Social Sciences 1: 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Van Praag, C. Mirjam. 2003. Business survival and sucess of young small business owners. Small Business Economics 21: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veciana, José Maria. 1988. Empresário y Proceso de Creación de Empresas. Revista Económica de Catalunya 8. [Google Scholar]

- Veciana, José Maria. 2005. La creación de Empresas- Un enfoque gerencial. Colección Estudio Económicos. Barcelo: Caja de Ahorros y Pensiones de Barcelona “La Caixa”. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, Pratima, and Vimal Kumar. 2022. Developing leadership styles and green entrepreneurial orientation to measure organization growth: A study on Indian green organizations. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 14: 1299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, Victor H., and Arthur G. Jago. 1988. The New Leadership: Managing Participation in Organizations. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xi, Huihui Yang, Helin Han, Yanling Huang, and Xixi Wu. 2022. Explore the entrepreneurial process of AI start-ups from the perspective of opportunity. Systems Research & Behavioural Science 39: 569–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya, Rusliza, and Fawzy Ebrahim. 2016. Leadership styles and organizational commitment: Literature review. Journal of Management Development 35: 190–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Jun, and Li Yan. 2016. Individual Entrepreneurship, Collective Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Small Business: An Empirical Study. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 12: 1053–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Jun, and Ritch L. Sorenson. 2003. Collective Entrepreneurship in Family Firms: The Influence of Leader Attitudes and Behaviors. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship 6: 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert K. 1989. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. California: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Yufeng, S. U., W. U. Nengquan, and Xiang Zhou. 2019. An entrepreneurial process model from an institutional perspective: A multiple case study based on the grounded theory. Nankai Business Review International 10: 277–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. 2006. Leadership in Organizations, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. 2012. Leadership in Organizations, 8th ed. Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Fan-qi, Xiang-zhi Bu, and Li Su. 2011. Study on entrepreneurial process model for SIFE student team based on Timmons model. Journal of Chinese Entrepreneurship 3: 204–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Weichun, Irene K. H. Chew, and William D. Spangler. 2005. CEO Transformational Leadership and Organizational outcomes: The mediating role of human-capital-enhancing human resource management. The Leadership Quarterly 16: 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Firm 1 | Firm 2 | Firm 3 | Firm 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legal Status | Sole proprietorship | Private limited company | Sole proprietorship | Private limited company |

| N° of Partners | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Sector of Activity | Business development and consultancy | Retail by correspondence or internet | Manufacture of articles in granite and stone | Sale of do-it-yourself and construction material |

| CAE | 70,220 | 47,910 | 23,703 | 47,523 |

| Start of Activity | May 2020 | March 2020 | 2015 | 1987 |

| N° Collaborators | 1 | 12 | 14 | 13 |

| Gender | Age | Qualifications | Post | Experience in the Firm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leader 1 | Male | 48 | Degree in Tourism, Post-Graduate in Hotel and Catering, and Master in Production Engineering | Manager | 2020 |

| Collaborator 1A | Female | 47 | Degree in Company Administration, Master in Entrepreneurship and Firm Creation (to be completed) | Consultant | 2020 |

| Leader 2 | Male | 24 | Degree in Management (to be completed) | Managing Director/Partner | 2020 |

| Collaborator 2A | Female | 27 | Diploma in Civil Engineering, MBAs (Civil Engineering, Development, and Management of BIM Projects) | Media Buyer | 2020 |

| Collaborator 2B | Male | 27 | Master in Physical Education (to be completed) | Commercial Manager | 2020 |

| Leader 3 | Male | 29 | Master in Economics and Finance | Economist | 2015 |

| Collaborator 3A | Female | 44 | Diploma in Accountancy | Administration | 2015 |

| Collaborator 3B | Female | 51 | Degree in Management | Clerk | 2015 |

| Leader 4 | Male | 44 | Ninth year | Manager | 1993 |

| Collaborator 4A | Female | 44 | Twelfth year | Administration | 2004 |

| Collaborator 4B | Male | 38 | Course specialised in technology | Clerical Assistant | 2015 |

| Type of Leadership Identified | Firm 1 (Phase 1: Discovering the Idea) | Firm 2 (Phase 2: Applying the Idea) | Firm 3 (Phase 3: Implementation) | Firm 4 (Phase 4: Growth) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| According to the leader | Transactional leadership | Transformational leadership | Transactional leadership | Participative leadership |

| According to the followers | Transactional leadership | Transformational leadership | Transactional leadership | Relational leadership |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baltazar, J.; Franco, M. The Influence of Different Leadership Styles on the Entrepreneurial Process: A Qualitative Study. Economies 2023, 11, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11020036

Baltazar J, Franco M. The Influence of Different Leadership Styles on the Entrepreneurial Process: A Qualitative Study. Economies. 2023; 11(2):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11020036

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaltazar, Juliana, and Mário Franco. 2023. "The Influence of Different Leadership Styles on the Entrepreneurial Process: A Qualitative Study" Economies 11, no. 2: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11020036

APA StyleBaltazar, J., & Franco, M. (2023). The Influence of Different Leadership Styles on the Entrepreneurial Process: A Qualitative Study. Economies, 11(2), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11020036