Abstract

The purpose of this article is to study the tax sustainability of agricultural companies in Ukraine. This article developed the following working hypotheses, which were derived from the main purpose of the study. The methodology for the assessment of tax sustainability has been improved due to the development of indicators of tax sustainability at all levels of the tax hierarchy. Our study confirms the hypothesis that the tax sustainability of Ukraine is worse than that of OECD member countries. The hypothesis that the tax sustainability of agricultural companies in Ukraine is worse compared to other sectors of the economy was confirmed as well. The main reason for the instability in the tax system and taxation of the agricultural sector of Ukraine is changes in tax legislation. The issue linked to the instability of agricultural companies is the lack of a company tax strategy. The research results presented in the paper are of considerable importance for ensuring the tax sustainability of agricultural companies in Ukraine.

1. Introduction

The tax sustainability concept is based on sustainability in the sense of Brundtland’s report (Our Common Future 1987): “We consider the tax system to be sustainable if it meets the needs of the economy in present without compromising the future function ability of the economy”, where the tax system comprises tax tools and tax related to legislative measures (Janova et al. 2019).

Fiscal sustainability is the ability of a government to maintain public finances at a credible and serviceable position over the long term. Ensuring long-term fiscal sustainability requires that governments engage in continual strategic forecasting of future revenues and liabilities, environmental factors, and socio-economic trends to adapt financial planning accordingly (OECD 2013). It is not advisable to equate fiscal sustainability with tax sustainability, but it is advisable to adapt the main provisions of the concept of fiscal sustainability to tax sustainability.

Tax sustainability is the ability of a government to ensure tax administration and tax revenues at a credible and serviceable position over the long term. Ensuring long-term tax sustainability requires governments to forecast future revenues and liabilities constantly strategically and socio-economic trends to adapt financial planning. The government is interested in ensuring tax stability since taxes are the main source of filling the budget in Ukraine. Economic agents are interested in ensuring tax stability since the activities of enterprises take place with clear “rules of the game” (taxation), which makes effective financial planning possible.

Ma and Park discussed Corporate Tax Sustainability through the relationship between corporate sustainability management and sustainable tax strategies (Ma and Park 2021). Ma and Park believe that the focus of corporate sustainability management, including tax sustainability management, is shifting from the short-term perspective to supporting stable tax indicators in the long term.

McGuire et al. define sustainability as the dimension of a firm’s tax strategy that focuses on maintaining consistent tax avoidance outcomes over time (i.e., a narrow range of effective tax rates). Conceptually, sustainability represents a different dimension of a firm’s tax strategy than tax minimization because sustainability focuses on the consistency of a firm’s tax avoidance outcomes over time without regard to the level of avoidance (McGuire et al. 2013). We believe that the problem of tax sustainability is broader and goes beyond tax evasion, but companies should strive for a narrow range of effective tax rates.

Tax sustainability of Ukraine on an annual basis is declared in the Tax Code by the principle of sustainability: “sustainability—changes to any elements of taxes and fees cannot be made later than six months before the beginning of the new budget period, in which new rules and rates will apply. Taxes and fees, their rates, as well as tax benefits cannot be changed during the budget year” (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine 2010). However, changes to the tax legislation are made before the start of the new budget period, in which new rules and rates will apply. We provide proof of violation of tax sustainability as the following laws: Law of Ukraine on 28 December 2014, No. 71-VIII; Law of Ukraine on 23 December 2015, No. 903-VIII; Law of Ukraine on 24 December 2015, No. 909-VIII; Law of Ukraine on 20 December 2016, No. 1791-VIII; Law of Ukraine on 21 December 2016, No. 1797-VIII; Law of Ukraine on 7 December 2017, No. 2176-VIII; Law of Ukraine on 7 December 2017, No. 2245-VIII; Law of Ukraine on 23 November 2018, No. 2628-VIII; Law of Ukraine on 4 November 2020, No. 962-IX; Law of Ukraine on 17 December 2020, No. 1115-VIII; Law of Ukraine on 17 December 2020, No. 1117-IX; Law of Ukraine on 30 November 2021, No. 1914-IX et al.

Under the conditions of constant changes in tax legislation, it is difficult to ensure the achievement of long-term goals of social and economic development at the macroeconomic and microeconomic levels.

The purpose of this article is to study the tax sustainability of agricultural companies in Ukraine. This article developed working hypotheses, which were derived from the main purpose of the study. We set out the hypotheses as follows.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The tax sustainability in Ukraine is worse than in OECD member countries.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The tax sustainability of agricultural companies in Ukraine is worse than companies in other sectors.

Our paper is structured as follows: Section 2 develops a methodology for identifying tax sustainability according to the tax sustainability hierarchy. Section 3 reviews the data of the empirical estimation of tax sustainability. The results of the empirical estimation of tax system sustainability in Ukraine, sectoral tax sustainability, tax sustainability of agricultural companies in Ukraine, and tax legislation research are presented in Section 4. Section 5 concludes the discussion by laying out directions for further work. Section 6 contains conclusions.

2. Methodology

Tax sustainability is a category that determines the state of taxation at different levels. The tax sustainability hierarchy includes the tax system sustainability, sectoral tax sustainability, tax sustainability of a company (Figure 1). Methodological bases for the determination of tax sustainability differ significantly depending on the level in the tax sustainability hierarchy.

Figure 1.

Tax sustainability hierarchy. Source: compiled by the authors.

2.1. Tax System Sustainability

Janova and Nerudova et al. proposed to define the tax sustainability index (TSI) based on four pillars and fourteen policy areas for determining tax system sustainability. These are the economic pillar (smart growth potential, sustainable consumption, excessive indebtedness prevention, investment activity), social pillar (employment, social cohesion, demography, and population growth), environmental pillar (climate change, waste generation/recycling, renewable energy and energy saving, green innovation), and institutional pillar (effectiveness of tax collection, tax moral incentives, compliance costs of taxation) (Janova et al. 2019; Nerudova et al. 2019). The sustainability in the institutional pillar was determined as the basis of the tax system sustainability (Janova et al. 2019).

Abramov et al. equate tax system sustainability with the sustainability of tax revenues. Scientists believe that the sustainability of tax revenues is manifested in the ability of centralized accumulation of a sufficient amount of financial resources to society while maintaining and subsequently stimulating the reproductive process in the economy (Abramova et al. 2021). The sustainability of tax revenues was determined by studying the coefficient of variation (Formula (1)), the coefficient of sustainability (Formula (2)), and the coefficient of stabilization (Formula (3)).

CV = σ(TR)/TRaver

CV—the coefficient of variation of tax revenues, σ(TR)—standard deviation of tax revenues, TRaver—arithmetic mean of tax revenues.

CS(TR) = 100% − CV(TR)

CS—is the coefficient of sustainability of tax revenues, CV(TR)—is the coefficient of variation of tax revenues.

RSC = CV (TR − TRi) − CV (TR),

RSC—is the coefficient of stabilization of tax revenues, CV (TR − TRi)—is the coefficient of variation of tax revenues deducting the tax (TRi), whose stabilizing/destabilizing impact is being studied, CV(TR)—is the coefficient of variation of tax revenues.

The coefficient of variation (CV) is designed to demonstrate the relative deviation of tax revenues to the average level of their time series. The coefficient of stabilization makes it possible to quantify the role of a particular tax in ensuring the sustainability of tax revenues in total. (Abramova et al. 2021).

The methodology for the assessment of the tax system sustainability proposed by Abramova et al. is based on three coefficients that consider the absolute indicators of tax revenues. Our study explores tax sustainability in Ukraine, considering the recent state of macroeconomic indicators in Ukraine. Due to the annual inflation rate in Ukraine (2014—12.07%, 2015—48.70%, 2016—13.91%, 2017—14.44%, 2018—10.95%, 2019—7.89%, 2020—2.73% (The World Bank Group 2020)), we cannot determine tax sustainability coefficients based on the absolute indicators of tax revenues. We believe that to determine tax sustainability in Ukraine, it is necessary to use a relative indicator. This includes the ratio of actual (total) tax revenue to GDP (Bahl 1971; Leuthold 1991; Ghura 1998; Jacobs and Spengel 1999; Nicodeme 2001; Eltony 2002; Blechová and Barteczková 2008; Simbachawene 2018; Dalamagas et al. 2019; Celikay 2020; Paientko and Oparin 2020; Kéïta and Laurila 2021; Mahfoudh and Gmach 2021); the ratio of actual (total) tax revenue to GNP (Chelliah et al. 1975; Leuthold 1991); and the ratio of actual tax revenue to gross state domestic product (GSDP) of states or the gross national income of a country (Purohit 2006).

Our methodology for the analysis of tax system sustainability is based on the scientific views of Abramova et al. and the monetary instability of Ukraine. We propose to use such indicators for the analysis of tax system sustainability as:

- (1)

- The tax to GDP ratio (Formula (4))Tax to GDP ratio = TR/GDPTR—tax revenues of a country, GDP—the country’s gross domestic product,

- (2)

- The coefficients of variation (Formula (5))CV = σ(tax to GDP ratio)/Tax to GDP ratioaverCV—the coefficient of variation of the tax to GDP ratio, σ (tax to GDP ratio)—standard deviation of the tax to GDP ratio, Tax to GDP ratioaver—arithmetic mean of the tax to GDP ratio.

- (3)

- The coefficient of sustainability of the tax-to-GDP ratio (Formula (6))CS (tax to GDP ratio) = 100% − CV(tax to GDP ratio)CS—the coefficient of sustainability of the tax-to-GDP ratio, CV (tax-to-GDP ratio)—the coefficient of variation of the tax-to-GDP ratio.

2.2. Sectoral Tax Sustainability

Researchers of the World Bank Group and other scientists conducted research on the taxation of individual sectors of the economy based on the quantitative marginal effective tax rate (Jacobs and Spengel 1999; The World Bank Group 2006) or absolute indicators of taxes paid (Boiko and Sytnyk 2018), and the differences between statutory and effective corporate income taxation (Nicodeme 2001; Carreras et al. 2017). There is not enough public statistical information to calculate the marginal effective tax rate. We continue the methodology of tax system sustainability analysis, and we propose to use the tax to gross value added by the sector ratio, the coefficient of variation of the tax to GVA by sector ratio, and the coefficient of sustainability of the tax-to-GDP ratio. The proposed indicators logically continue the indicators of tax system sustainability assessment, since the gross value added at basic prices (formerly GDP at factor cost) is derived as the sum of the value added in the agriculture, industry, and services sectors (The World Bank Group 2015).

We proposed to use the following indicators (Formulas (7)–(9)) for the analysis of sectoral tax sustainability:

- (1)

- The tax to gross value added (GVA) by sector ratio (Formula (7))Tax to GVA ratio = TRsector/GDPsectorTR sector—tax revenues by sector, GVAsector—gross value added by sector.

- (2)

- The coefficients of variation of the tax to GVA by sector ratio (Formula (8))CV = σ(tax to GVA ratio)/Tax to GVA ratioaverCV—the coefficient of variation of the tax to GVA by sector ratio, σ (tax to GVA ratio)—standard deviation of the tax to GVA by sector ratio, and Tax to GVA ratioaver—arithmetic mean of the tax to GVA by sector ratio.

- (3)

- The coefficient of sustainability of the tax to GVA by sector ratio (Formula (9))CS(tax to GVA ratio) = 100% − CV(tax to GVA ratio)CS—the coefficient of sustainability of the tax to GVA ratio, CV (tax to GVA ratio)—the coefficient of variation of the tax to GVA ratio.

2.3. Tax Sustainability of the Company

Minton, Schrand and Walther, McGuire, Neuman, Omer et al. measure the sustainability of a firm’s tax strategy using the coefficient of variation for annual cash effective tax rates (ETRs or Cash ETR) (Nicodeme 2001; Minton et al. 2002; McGuire et al. 2013; Ma 2018; Ma and Park 2021). Many modern scientists support the idea of calculation of the cash effective tax rate for the needs of tax analysis (Dyreng et al. 2008; Hanlon and Heitzman 2010; Tax Policy Briefing Book 2010; Hasan et al. 2014; Edwards et al. 2016; Bonsall et al. 2017; Guenther et al. 2017; Carreras et al. 2017; Salaudeen and Atoyebi 2018; Dyreng et al. 2019; Fernández-Rodríguez et al. 2019; Hutchens et al. 2020; Dhawan et al. 2020; Nurwati and Kalbuana 2021). Shin and Park define two relative indicators in their research: the cash effective tax rate and the effective tax rate (Shin and Park 2022).

The effective average tax rate (EATR) measures the effective tax burden of projects that earn more than the capital costs (i.e., projects generating economic rents) (Jacobs and Spengel 1999). Such an indicator has limitations in its use since taxes are paid by the agricultural companies of Ukraine both for profitable projects and unprofitable projects.

The discussion of the determination of the cash-effective tax rate lies in the comparison of various absolute indicators. The cash effective tax rate formula (Formula (10)) is based on cash taxes paid and the pre-tax income (Edwards et al. 2021).

Cash ETR—the cash effective tax rate, TXPD—the cash taxes paid, PI—the pre-tax income.

Cash ETR = TXPD/PI,

The effective average tax rate (EATR) measures the effective tax burden of projects that earn more than the capital costs (i.e., projects generating economic rents) (Jacobs and Spengel 1999). This indicator (EATR) has limitations in its use for agricultural companies in Ukraine since agricultural companies of Ukraine pay taxes both for profitable projects and for unprofitable projects. Often, agricultural companies in Ukraine choose to pay a single tax. The object of taxation of the single tax is not profit, but the object of taxation of the single tax is the size of the land.

Some scientists calculate the cash effective tax rate based on corporate income tax in the denominator of the formula (Gupta and Newberry 1997; Blechová and Barteczková 2008; Fernández-Rodríguez and Martínez-Arias 2014; Aksoy Hazır 2019; Mascagni and Mengistu 2019; Bubanić and Šimović 2021; Bachas et al. 2022) and net profit (Bachas et al. 2022), gross profit (Tax Policy Briefing Book 2010; Carreras et al. 2017; Mascagni and Mengistu 2019), profit before tax (Bubanić and Šimović 2021), gross income (Poltorak and Volosyuk 2016; Levkovets et al. 2023), and net income (Poltorak and Volosyuk 2016) in the numerator of the formula.

We believe that the limitation of the corporate income tax is inappropriate. In the example of Ukraine, there are eleven taxes in the tax system, so it is not advisable to limit to corporate income tax. Under such a limitation of the corporate income tax, it is not possible to determine the real total and corporate income taxation. The effective tax rates are measured as ratios of taxes paid by corporations on a measure of the tax base which can be the corporate gross operating surplus (gross operating profit) or the aggregate corporate profit (Nicodeme 2001). ETR is the ratio of tax expense over the financial accounting income of a company (Janssen and Buijink 2000).

The taxation of agricultural companies in Ukraine requires the adjustment of generally accepted approaches to the determination of the cash-effective tax rate. The modified cash effective tax rate (METR) is defined as the ratio of the cash taxes paid to gross revenue (Formula (11))/gross operating profit (Formula (12)).

METR1—the first modernized cash effective tax rate, TXPD—the cash taxes paid, and GR—gross revenue of the company.

METR2—the second modernized cash effective tax rate, TXPD—the cash taxes paid, and GOP—gross operating profit of the company.

METR1 = TXPD/GR

METR2 = TXPD/GOP

For the analysis of the tax sustainability of the company, taking into account the peculiarities of taxation of agricultural companies in Ukraine, we proposed to determine the coefficient of variation/the coefficient of sustainability of the first modernized cash effective tax rate and the second modernized cash effective tax rate.

The time interval is an important aspect of the analysis of tax sustainability. Ma studies tax sustainability by the 5-year coefficient of variation in cash ETR (Ma 2018; Ma and Park 2021). The 5 years is often used in scientific research: for example, for the study of the valuation of the tax avoidance measure on firm governance (Desai and Dharmapala 2009); for the study of volatility of cash tax rates (Hutchens et al. 2020); and for the study of the relationship between corporate sustainability management and sustainable tax strategies (Ma and Park 2021). To study the influence of ownership structure on the determinants of effective tax rates, Fernández-Rodríguez et al. used 3 years; 10 years is used in the scientific research of Bubanic and Simovic and Dyreng et al. (Bubanić and Šimović 2021; Dyreng et al. 2008). Edwards et al. used the 10 years for the study of the trend in U.S. Cash Effective Tax Rates (Edwards et al. 2021).

3. Data

We have chosen 5 years and 9 years for our empirical study of the tax sustainability of agricultural companies. Five years is used by the most common scientific practice of tax research. Nine years is used in accordance with available public information. The State Tax Service of Ukraine limits the periods for the publication of data on taxes paid.

For our empirical study of the tax sustainability of agricultural companies, we have chosen companies that operate in various sections of Section A according to NACE (01.11 Growing of cereals (except rice), leguminous crops and oil seeds—58%, 01.21 Growing of grapes—3%, 01.24 Growing of pome fruits and stone fruits—11%, 01.41 Raising of dairy cattle—3%, 01.46 Raising of swine/pigs—8%, 01.47 Raising of poultry—11%, 01.50 Mixed farming—3%, 03.22 Freshwater aquaculture—5%). The agricultural companies have different organizational and legal forms (private joint stock company (PrJSC)—81%, public joint stock company (PJSC)—16%, limited liability company (LLC)—3%). The agricultural companies operate in 64% of Ukraine’s regions (Vinnytsia region, Dnipropetrovsk region, Donetsk region, Zhytomyr region, Zaporizhzhya region, Kyiv region, Kirovohrad region, Mykolaiv region, Odesa region, Poltava region, Sumy region, Kharkiv region, Kherson region, Cherkasy region, Chernihiv region, Kyiv city). The companies from the sample must make a public disclosure of financial statements on the websites of the National Commission on Securities and the Stock Market of Ukraine. Our final sample consists of 342 firm-year observations (38 unique agricultural companies). The companies from the sample must make a public disclosure of financial statements on the websites of the National Commission on Securities and the Stock Market of Ukraine.

We used correlation analysis to determine the degree of connection between the dynamics of tax system sustainability and the tax sustainability of agricultural companies of Ukraine, and we used cluster analysis to form clusters by the level of the tax burden by sector.

4. Empirical Results

In Section 4, we provide an empirical analysis of tax sustainability according to all levels in the tax sustainability hierarchy. This is the tax system sustainability (Section 4.1), sectoral tax sustainability (Section 4.2), and tax sustainability of a company (Section 4.3). In the rest of Section 4, we provide information on the sustainability of the tax legislation and taxation system of Ukraine.

4.1. Tax System Sustainability

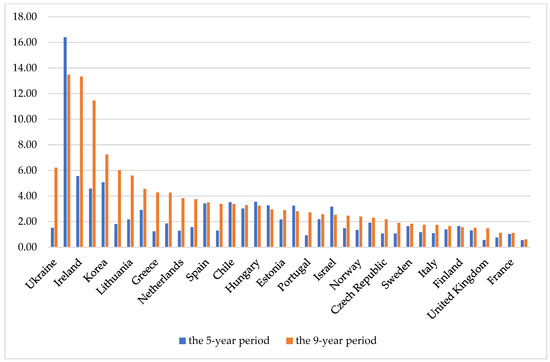

The system sustainability of Ukraine forms the basis for the tax sustainability of agricultural companies. The tax-to-GDP ratio in Ukraine ranged from 23.16% to 27.78% (2012—25.67%, 2013—24.16%, 2014—23.16%, 2015—25.53%, 2016—27.28%, 2017—27.78%, 2018—27.70%, 2019—26.91%, 2020—26.92% (The State Statistics Service of Ukraine 2020; Ministry of Finance of Ukraine 2020)). The tax-to-GDP ratio in Ukraine is as close as possible to the corresponding indicator in Korea, Lithuania, Turkey, USA, Switzerland, etc. (Table A1). The disadvantage of the tax system of Ukraine is the high level of the coefficients of variation of the tax-to-GDP ratio. In 2012–2020, the coefficient of the tax variation tax-to-GDP ratio was 6.2%. The coefficient of the tax variation tax-to-GDP ratio in Ukraine was lower only in Iceland, Ireland, Mexico, and Korea (Figure 2). Ukraine has chosen the vector of European integration, and the tax system sustainability does not correspond to European practices and trends (Netherlands, Spain, Latvia, Hungary, Luxembourg, Estonia, Portugal, Denmark—2 times, Switzerland, Norway, Czech Republic, Germany, Sweden—3 times, Belgium, Italy, Finland, United Kingdom—4 times, France—6 times и et al. (OECD Data 2020)). Over the past 9 years, the main signs of the instability of the tax system of Ukraine have been a change in the number of taxes (the number of state taxes was reduced from 18 to seven, and the number of local taxes was reduced from five to four in 2014), a change in the procedure for the administration of certain taxes, a change in state tax bodies (Ministry of Revenue and Duties of Ukraine, State Fiscal Service of Ukraine, State Tax Service of Ukraine), the accumulation of deficits and the continuous growth of the public debt of Ukraine. Ukraine has a deficit in the consolidated budget from 2003 to 2021. The budget deficit in Ukraine ranged from 1.4% to 5.3% (2012—3.6%, 2013—4.3%, 2014—4.5%, 2015—1.6%, 2016—2.3%, 2017—1.4%, 2018—1.9%, 2019—2.2%, 2020—5.3% (Ministry of Finance of Ukraine 2020)). The accumulation of budget led to an increase in the nominal and real government debt. The dynamics of the tax-to GDP ratio in Ukraine correlate with the dynamics of the budget deficit and dynamics of the central government debt in 2016, 2019, and 2020.

Figure 2.

The coefficients of the variation tax-to-GDP ratio.

In 2016–2020, the coefficient of variation of the tax-to-GDP ratio was 1.5% in Ukraine. The achievement of such a level of the coefficient of variation of the tax-to-GDP ratio can be considered a positive phenomenon for the economy and the society of Ukraine. This indicates the beginning of the period of tax system sustainability in Ukraine.

4.2. Sectoral Tax Sustainability

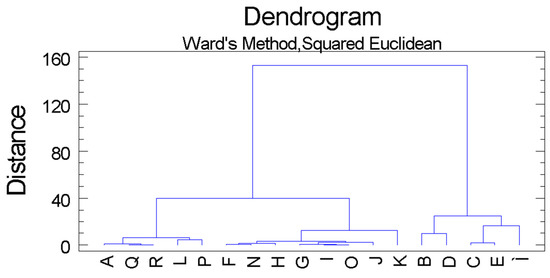

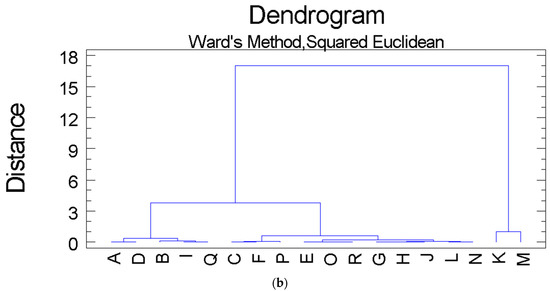

The indicators of the tax burden of taxpayers by sector in Ukraine (Table A2) confirm the unevenness of the tax burden and the possibility of forming three clusters (Table 1, Figure 3).

Table 1.

Sectoral tax sustainability in Ukraine, our calculation.

Figure 3.

Dendogram of the tax to GVA ratio by sectors in 2012–2020 in Ukraine.

Sectors with a low tax to GVA ratio belong to the first cluster. These are agriculture, forestry and fishing, human health and social work activities, arts, entertainment and recreation, real estate activities, and education. Sectors with an average level of tax to GVA ratio belong to the second cluster. These are construction, administrative and support service activities, transportation and storage, wholesale, and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles, accommodation and food service activities, public administration, and defense; compulsory social security, information and communication, financial and insurance activities. Sectors with a high level of tax to GVA ratio belong to the third cluster. These are mining and quarrying, electricity, gas, manufacturing and water supply, sewerage, professional, scientific and technical activities.

Another argument for confirmation of the unevenness of the tax burden is the ratio of the minimum and maximum tax to GVA ratio (2012 and 2015—11 times, 2013—10 times, 2014—9 times, 2016–2017—7 times, 2018—6 times, 2019—5 times). Thus, a sign of tax sustainability in Ukraine, along with a decrease in the coefficient of variation of tax-to-GDP ratio, was a decrease in the ratio of the minimum and maximum tax to GVA ratio.

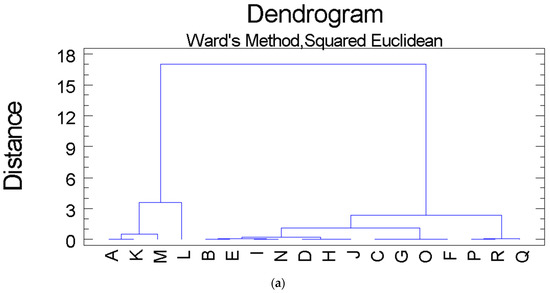

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the tax to GVA ratio by sectors in 2012–2020 in Ukraine. In Ukraine, the coefficient of variation of the tax to GVA ratio by sectors in 9 years indicates a high level of tax sustainability in manufacturing, construction, public administration and defense, wholesale, and retail trade. Figure 4a shows the application of cluster analysis and complements the cluster of a high level of tax sustainability in mining and quarrying; water supply; sewerage; accommodation and food service activities; administrative and support service activities; electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply; transportation and storage; information and communication. Among the sectors which for 9 years had a violation of tax unsustainability confirmed by calculations are agriculture, forestry, and fishing; financial and insurance activities; real estate activities; and professional, scientific and technical activities. Thus, agriculture, forestry and fishing had the second largest coefficient of variation of the tax to GVA ratio after real estate activities. Other sectors of the economy operated in the conditions of a lower level of the coefficient of variation of the tax to GVA ratio and had greater opportunities for sustainability and development.

Figure 4.

Dendogram of the coefficient of variation of the tax to GVA ratio by sectors in 2012–2020 in Ukraine (a) over 9 years; (b) over 5 years.

Over 5 years, the sectoral tax sustainability in Ukraine has changed compared to 9 years. The improvement of the level of sectoral tax sustainability and the reduction in the coefficient of variation of the tax-to-GVA ratio occurred in all sectors except construction (6.74% in 5 years versus 6.84% in 9 years). Different dynamics of the coefficient of variation of the tax to GVA ratio led to structural changes in sectoral tax sustainability (Figure 4b).

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing in Ukraine increased the level of tax sustainability and reduced the coefficient of variation of the tax to GVA ratio by 3.2 times (43.15% over 9 years versus 13.57% over 5 years). However, agriculture, forestry and fishing over 9 years continue to be in the cluster with a high level of the coefficient of variation of the tax to GVA ratio. Mining and quarrying, electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply; accommodation and food service activities; and human health and social work activities complement the cluster of sectors with a high level of the coefficient of variation of the tax to GVA ratio. If over 9 years agriculture, forestry and fishing was inferior to one sector in terms of tax instability, then over 5 years, the leaders were financial and insurance activities: professional, scientific, and technical activities.

4.3. Tax Sustainability of Agricultural Companies

We will begin the study of the tax sustainability of agricultural companies (38 agricultural companies) with the definition of the first modernized cash effective tax rate, which shows the tax burden on the income of agricultural companies (Table A3).

The coefficient of variation of the first modernized cash effective tax rate indicates the presence of problems of tax sustainability of agricultural companies. We proved the existence of the instability of the tax system of Ukraine and agricultural taxation. However, there are other reasons.

For example, some agricultural companies changed from a general taxation system to a simplified taxation system and vice versa. These are PrJSC “Agro-industrial association” “Krasnyi Chaban”, PrJSC “Zernoprodukt MKHP”, PrJSC “Khmelnytskyi Vyrobnyche Silskohospodarsko-Rybovodne Pidpryiemstvo”, PrJSC “Ukrzernoimpeks”, and PrJSC “Zelenyi hai” (Table 2). The changes negatively affected the tax sustainability of agricultural companies and contributed to high values of the coefficient of variation of the first modernized cash effective tax rate: PrJSC “Agroindustrial association” “Krasnyi Chaban” (in 9 years, this was 69.41%; in 5 years, this was 63.31%), PrJSC “Zernoprodukt MKHP” (in 9 years, this was 60.15%; in 5 years, this was 49.77%), PrJSC “Khmelnytskyi Vyrobnyche Silskohospodarsko-Rybovodne Pidpryiemstvo” (in 9 years, this was 127.45%; in 5 years, this was 88.17%), PrJSC “Ukrzernoimpeks” (in 9 years, this was 45.62%; in 5 years, this was 22.85%), PrJSC “Zelenyi hai” (in 9 years, this was 192.25%; in 5 years, this was 145.34%). Thus, 13% of agricultural companies of Ukraine from the sample had a manifestation of tax instability associated with changes in the taxation system at the initiative of the company’s management.

Table 2.

Tax sustainability of agricultural companies of Ukraine, our own calculation.

We proved an increase in the level of tax sustainability in the agricultural sector of Ukraine in a 5-year period against a 9-year period. Ninety-two percent of the sample of agricultural companies comply with the trends of the agricultural sector of Ukraine and increased the level of tax sustainability. Exceptions are PrJSC “Ahrofort”, PrJSC “Agricultural company” “Slobozhanskyi”, and PrJSC “Agricultural company” “Chornomorska perlyna”.

4.4. Unsustainability of Tax Legislation and Taxation System of Ukraine

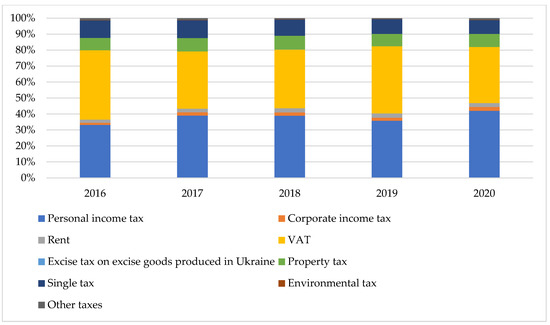

According to the Tax Code of Ukraine, agricultural companies of Ukraine can choose a general taxation system or a simplified taxation system (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine 2010). Figure 5 shows that the main tax burden of agricultural companies is the value added tax (VAT), personal income tax, and single tax. A comparison of the amounts of paid single tax and corporate income tax indicates that agricultural companies prefer paying a single tax.

Figure 5.

The structure of taxes paid by agricultural companies over 5 years.

The general system of taxation of agricultural companies is based on the corporate income tax as well as personal income tax, value-added tax, rent for the special use of water, property tax (land tax, real estate tax, etc.), and environmental tax.

The simplified system of taxation of agricultural companies is based on a single tax of the fourth group. Agricultural companies which belong to the single taxpayers of the fourth group are exempted from the obligation to pay such taxes as:

- (1)

- Corporate income tax.

- (2)

- Personal income tax in the part of taxation of incomes received as a result of economic activity.

- (3)

- Property tax in the part of land tax for land plots used by payers for agricultural production.

- (4)

- Rent payment for special use of water.

Therefore, the formation of a violation of the tax sustainability of companies occurs due to the changes in tax legislation related to the chosen taxation system. The main changes in the tax legislation on corporate income tax for agricultural companies (Table 3) are associated with a change in the procedure for the determination of the object of taxation, a change in the list of differences for adjustment of the financial result before taxation, and a change in the procedure for calculation of the tax on the profit of agricultural companies, considering the minimum tax liability for land plots classified as agricultural land.

Table 3.

The main changes in the corporate income tax of agricultural companies.

Agricultural companies of Ukraine, which are on the general system, pay rent for the special use of water for agricultural production. The rent for the special use of water has both quantitative and qualitative significant changes. Over the past 7 years, rental rates for the special use of water have been increased four times. However, tax instability was more caused by the changed object of taxation of the rent for the special use of water and changed approaches to setting of the rates of rent for the special use of underground water (Table 4).

Table 4.

The main changes in the rent for the special use of water of agricultural companies.

Payment for land rent is a mandatory payment that is a part of the property tax and is paid in the form of land tax or rent for land plots of state and communal property (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine 2010). Regarding the land tax, in 2014, the approach to setting of the land tax rates was changed; the list of land plots, which are subjects and are not subjects of taxation, was changed (Table 5). In 2015–2018, there was a partial change in the amount of the land tax, which increased the burden on agricultural enterprises but did not change the land tax administration process. Regarding the rent, in 2014, the procedure for calculation and payment of the rent was changed, and in the following years, there was a change in the rental rates.

Table 5.

The main changes in the payment for land of agricultural companies.

Agricultural companies of Ukraine, which are on a general taxation system or a simplified taxation system, pay value-added tax, which is the main budget-forming tax in Ukraine. Exactly this tax causes the greatest difficulties in administration and constitutes a significant threat to the tax stability. In 2014, the amount of the total number from transactions for the supply of goods/services was increased from UAH 300,000 to UAH 1 million. In 2015, the Unified Register of Tax Invoices was introduced to control tax liabilities and tax credits among enterprises, including agricultural ones (Table 6). In 2019, the procedure for stopping the registration of tax invoices in the Unified Register of Tax Invoices was approved, and a positive tax history in agricultural enterprises with at least 200 hectares of land is being formed. Thus, the threat of deterioration of business activity arose in small agricultural companies.

Table 6.

The main changes in the value added tax of agricultural companies.

The manifestations of the threat to the tax sustainability of agricultural companies were changes in the VAT rate for certain types of agricultural products. In 2020, a preferential rate of 14% for cattle, swine, sheep, whole milk, wheat and a mixture of wheat and rye (meslin), rye, barley, oats, corn, soybeans, flax seed, rapeseed, sunflower seed, seed and fruits of other oil crops, sugar beets, was introduced, and in 2021, the preferential rate was canceled for most of these agricultural products.

Regardless of the chosen taxation system, the agricultural companies of Ukraine act as tax agents for personal income tax when concluding lease agreements for agricultural land plots. Examples of violation of tax sustainability for personal income tax are:

- (1)

- Cooperative payments to the member of the agricultural cooperative, the amount of the share returned to the member of the agricultural cooperative was added to the incomes that are not subject to personal income tax; in accordance with the Law of Ukraine on 10 July 2018 No. 2497-IX agricultural companies were defined as tax agents in relation to income from the lease of agricultural land, land share (share).

- (2)

- Individuals, individuals–residents who own and/or use land plots classified as agricultural land were added to the payers of tax on income in terms of the minimum tax liability; in accordance with the Law of Ukraine on 30 November 2021 No. 1914-IX, the concept for the determination of minimum tax liability for taxpayers, individuals who own, rent or use on other terms (including on the terms of emphyteusis) land plots classified as agricultural land was defined.

The changes of 2021 created an additional tax burden on agricultural companies, which must not be less than the minimum tax liability determined by the Tax Code of Ukraine.

Until 2015, the simplified system of taxation of agricultural enterprises provided the calculation and payment of a fixed agricultural tax, but this tax was removed from the tax system of Ukraine. Since 2015, agricultural enterprises have been able to pay a single tax of the fourth group. Despite the propensity of agricultural enterprises of Ukraine to pay this tax and its simplicity in calculation and payment, the single tax of the fourth group should be classified as taxes with a high level of legislative instability.

In 2014–2021, the tax base for the single tax of the fourth group was changed, the procedure for the transition of agricultural companies to a simplified taxation system was changed, and the requirements for agricultural enterprises were changed; single tax rates of the fourth group have been changed several times (Table 7).

Table 7.

The main changes in the single tax of agricultural companies.

5. Discussion

The sectoral analysis of diversification of the tax burden is carried out as a component of the analysis of tax systems and tax reforms (Jacobs and Spengel 1999; Nicodeme 2001; The World Bank Group 2006; Sybiryanka and Pyslytsya 2016; Carreras et al. 2017; Boiko and Sytnyk 2018; Salaudeen and Atoyebi 2018; Boiko et al. 2019; Bhattarai et al. 2019). In Vietnam, the corporation income tax rate is highest in refined petroleum products (41.93%), followed by the agriculture sector (18.46%), health and social work (14.59%), and hotels and restaurants (12.32%) (Bhattarai et al. 2019). In Vietnam, the value-added tax (VAT) rate is applied to the renting of machinery and equipment (9.14%), followed by R&D (5.36%), real estate activities (5.09%), and wholesale and retail trade (3.48%) (Bhattarai et al. 2019). In Ukraine, a high level of tax burden is typical for the extractive industry, processing industry, electricity and water supply, and professional, scientific, and technical activities; a low tax burden is typical for agriculture, real estate transactions, education, health care and social assistance, arts, sport, entertainment, and recreation (Boiko and Sytnyk 2018). In South Africa, companies in the finance and mining sectors face the highest effective tax rate (Carreras et al. 2017).

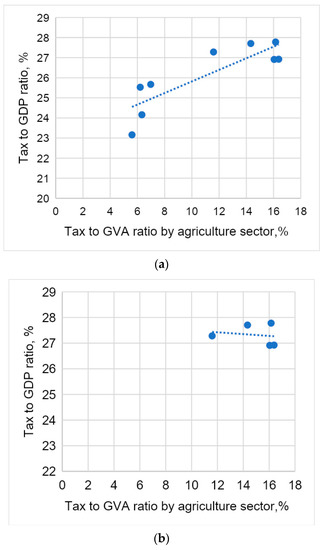

Based on the results of the analysis of tax sustainability in agriculture, forestry, and fishing (hereinafter referred to as the agricultural sector), we made the following conclusions: the tax sustainability in the agricultural sector of Ukraine is the worst tax sustainability in Ukraine. The coefficient of determination of the tax to GVA ratio and the tax-to-GDP ratio was 0.72, the coefficient of correlation of the tax to GVA ratio by the agriculture sector and the tax-to-GDP ratio was 0.85 (Figure 6a). The tax to GVA ratio increases at a faster pace than the tax-to-GDP ratio over 9 years. The indicator of the tax to GVA ratio is higher than the tax-to-GDP ratio over 9 years. Over 5 years, the coefficient of determination of the tax to GVA ratio and the tax-to-GDP ratio was 0.03, the coefficient of correlation of the tax to GVA ratio by the agriculture sector and the tax-to-GDP ratio was −0.17 (Figure 6b). We proved that there is no connection between the dynamics of the tax to GVA ratio and the tax-to-GDP ratio.

Figure 6.

The agriculture sector and the tax-to-GDP ratio in Ukraine (a) over 9 years; (b) over 5 years.

The tax sustainability in the agricultural sector of Ukraine is the worst in comparison with other sectors, which confirms the value of the coefficient of variation of tax to GVA ratio. The tax sustainability in the agricultural sector of Ukraine is disturbed due to the tax to GVA ratio and the positive dynamics of the tax to GVA ratio. In 2012–2015, the average of the tax to GVA ratio was 6.2% (CV (tax to GVA ratio) was 9.0%); however, in 2016, there was an increase in the tax to GVA ratio. The upward trend in the tax to GVA ratio was in the following years, which indicates the formation of an additional tax burden on agricultural companies.

The main reason for tax instability in the agricultural sector of Ukraine is changes in tax legislation. The problem of constant changes in the tax legislation of Ukraine has been studied by scientists, and its negative impact on economic activity and economic freedom in Ukraine has been proved (Kolomiiets 2018; Kasianenko et al. 2019; Abuselidze and Surmanidze 2020; Paientko and Oparin 2020), as well as the activities of agricultural companies (Boiko and Drahan 2017; Kostornoi et al. 2021). The directions for ensuring the tax stability of agricultural enterprises should be ensuring the stability of tax legislation and introducing a moratorium on changes to tax legislation.

Tax unsustainability in the agricultural sector of Ukraine is supplemented by variations in state support from the budget (grants, subsidies). The net income of the budget from the agricultural sector increased nominally (2012—UAH 172 million, 2013—UAH 442 million, 2014—UAH 3160 million, 2015—UAH 8818 million, 2016—UAH 26638 million, 2017—UAH 36061 million, 2018—UAH 37610 million, 2019—UAH 43108 million, 2020—UAH 50274 million), taking into account inflation. In 2015, the share of subsidies and grants to agricultural enterprises accounted for about half of tax revenues and will decrease in the following years. In 2016, the state refused to finance many programs supporting agricultural enterprises, which indicates instability in the direction of subsidies to agricultural enterprises in Ukraine.

6. Conclusions

The purpose of this article is the study of the tax sustainability of agricultural companies in Ukraine. This article developed the following working hypotheses.

In this paper, we conducted a study of the tax sustainability of agricultural companies in Ukraine in 2012–2020. The methodology for the assessment of tax sustainability has been improved due to the development of indicators of tax sustainability at all levels of the tax hierarchy. These are tax system sustainability (the coefficient of variation of the tax-to-GDP ratio, the coefficient of sustainability of the tax-to-GDP ratio), sectoral tax sustainability (the coefficients of variation of the tax to GVA by sector ratio, the coefficient of sustainability of the tax to GVA by sector ratio), and tax sustainability of the agricultural company (the coefficients of variation of the cash effective tax rate, the coefficient of sustainability of the cash effective tax rate). The definition of tax stability indicators is based on relative indicators, which contradicts the main developments in financial science. The reason for such a scientific position is monetary instability in Ukraine.

Our study confirms the hypothesis that the tax sustainability of Ukraine is worse than it is in OECD member countries. In 2012–2020, the coefficient of the tax variation tax-to-GDP ratio in Ukraine was 6.2%, while the coefficient of the tax variation tax-to-GDP ratio in OECD member countries was 1.2%. In 2016–2020, the coefficient of variation of the tax-to-GDP ratio in Ukraine was 1.5%, while the coefficient of the tax variation tax-to-GDP ratio in OECD member countries was. 0.3%. The achievement of such a level of the coefficient of variation of the tax-to-GDP ratio in Ukraine can be considered as a positive phenomenon for the economy and the society.

The hypothesis that the tax sustainability of agricultural companies in Ukraine is worse than it is in companies of other sectors was confirmed as well. The agricultural sector of Ukraine had the second largest coefficient of variation of the tax-to-GVA ratio after real estate activities. Other sectors of the economy operated in the conditions of a lower level of the coefficient of variation of the tax-to-GVA ratio and had greater opportunities for sustainability and development. The main reason of tax instability in the agricultural sector of Ukraine is changes in the tax legislation of corporate income tax; personal income tax; property tax; single tax of the fourth group; and rent payment for special use of water. We identified other reasons for the violation of the tax sustainability of agricultural companies in Ukraine. These are the lack of the company tax strategy, a change from general taxation system to simplified taxation system and vice versa.

The research results presented in the paper are of considerable importance for ensuring the tax sustainability of agricultural companies in Ukraine.

The directions for ensuring the tax stability of agricultural enterprises should be ensuring the stability of tax legislation and introducing a moratorium on changes to tax legislation, the simplification and comprehensibility of tax administration, monitoring tax risks and implementing risk-oriented corporate tax management. The perspective for future investigation is the study of influencing factors on the tax strategy and tax tactics of agricultural companies in Ukraine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B., M.N., N.D. and V.K.; methodology, S.B. and V.K.; writing—review and editing, S.B., M.N., N.D. and V.K.; visualization, M.N.; supervision, N.D.; project administration, N.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The tax-to-GDP ratio (OECD Data 2020).

Table A1.

The tax-to-GDP ratio (OECD Data 2020).

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 41.77 | 42.63 | 42.7 | 43.13 | 41.75 | 41.87 | 42.25 | 42.56 | 42.13 |

| Belgium | 44.33 | 45.04 | 44.76 | 44.13 | 43.32 | 43.85 | 43.87 | 42.7 | 43.07 |

| Canada | 31.18 | 31.13 | 31.27 | 32.82 | 33.26 | 33.04 | 33.51 | 33.81 | 34.39 |

| Chile | 21.33 | 19.86 | 19.61 | 20.39 | 20.13 | 20.17 | 21.13 | 20.89 | 19.32 |

| Colombia | 19.72 | 20.02 | 19.55 | 19.9 | 19.08 | 18.98 | 19.27 | 19.7 | 18.72 |

| Costa Rica | 22.57 | 22.98 | 22.61 | 22.95 | 23.49 | 22.98 | 23.19 | 23.58 | 22.89 |

| Czech Republic | 33.44 | 33.71 | 32.85 | 33.13 | 34.03 | 34.44 | 34.98 | 34.78 | 34.38 |

| Denmark | 45.51 | 45.89 | 48.53 | 46.06 | 45.49 | 45.48 | 44.17 | 46.6 | 46.54 |

| Estonia | 31.7 | 31.67 | 32.13 | 33.32 | 33.52 | 32.55 | 33.05 | 33.53 | 34.51 |

| Finland | 42.41 | 43.41 | 43.51 | 43.52 | 43.73 | 42.86 | 42.39 | 42.25 | 41.91 |

| France | 44.36 | 45.37 | 45.45 | 45.28 | 45.37 | 46.07 | 45.88 | 44.88 | 45.43 |

| Germany | 36.82 | 36.95 | 36.81 | 37.26 | 37.75 | 37.73 | 38.43 | 38.62 | 38.34 |

| Greece | 36.34 | 35.94 | 36.3 | 36.63 | 38.91 | 39.29 | 40.00 | 39.48 | 38.78 |

| Hungary | 39.00 | 38.52 | 38.44 | 38.7 | 39.08 | 37.86 | 36.82 | 36.47 | 35.68 |

| Iceland | 33.95 | 34.32 | 37.11 | 35.14 | 50.29 | 37.13 | 36.45 | 34.84 | 36.09 |

| Ireland | 28.11 | 28.67 | 28.73 | 23.17 | 23.55 | 22.58 | 22.35 | 21.9 | 20.20 |

| Israel | 29.89 | 30.62 | 30.88 | 31.22 | 31.13 | 32.29 | 30.8 | 30.21 | 29.73 |

| Italy | 43.62 | 43.83 | 43.33 | 42.96 | 42.24 | 41.91 | 41.73 | 42.41 | 42.91 |

| Japan | 27.95 | 28.56 | 29.97 | 30.24 | 30.28 | 30.92 | 31.55 | 31.41 | |

| Korea | 23.70 | 23.14 | 23.38 | 23.74 | 24.75 | 25.36 | 26.69 | 27.3 | 27.98 |

| Latvia | 28.95 | 29.21 | 29.77 | 29.86 | 30.8 | 31.2 | 31.14 | 31.24 | 31.91 |

| Lithuania | 26.92 | 26.71 | 27.48 | 28.68 | 29.66 | 29.64 | 30.23 | 30.28 | 31.25 |

| Luxembourg | 38.4 | 38.2 | 37.5 | 36.16 | 36.33 | 37.45 | 39.47 | 38.95 | 38.27 |

| Mexico | 12.65 | 13.3 | 13.69 | 15.9 | 16.61 | 16.08 | 16.14 | 16.35 | 17.93 |

| Netherlands | 35.59 | 36.11 | 37.05 | 37.01 | 38.41 | 38.7 | 38.8 | 39.26 | 39.68 |

| New Zealand | 31.64 | 30.46 | 31.2 | 31.5 | 31.38 | 31.3 | 32.17 | 31.46 | 32.18 |

| Norway | 41.41 | 39.82 | 38.75 | 38.42 | 38.88 | 38.78 | 39.37 | 39.91 | 38.61 |

| OECD—Average | 32.41 | 32.67 | 32.89 | 32.94 | 33.59 | 33.37 | 33.49 | 33.42 | 33.51 |

| Poland | 32.16 | 32.07 | 32.07 | 32.43 | 33.37 | 34.12 | 35.14 | 35.11 | 35.98 |

| Portugal | 31.67 | 33.97 | 34.18 | 34.38 | 34.05 | 34.11 | 34.66 | 34.5 | 34.75 |

| Slovak Republic | 28.74 | 31 | 31.9 | 32.66 | 33.16 | 34.04 | 34.2 | 34.57 | 34.75 |

| Slovenia | 37.68 | 37.24 | 37.18 | 37.31 | 37.38 | 37.08 | 37.27 | 37.17 | 36.85 |

| Spain | 32.37 | 33.12 | 33.89 | 33.84 | 33.6 | 33.87 | 34.66 | 34.68 | 36.62 |

| Sweden | 42.13 | 42.5 | 42.18 | 42.63 | 44.09 | 44.09 | 43.77 | 42.83 | 42.6 |

| Switzerland | 25.88 | 26.01 | 25.91 | 26.65 | 26.64 | 27.35 | 26.81 | 27.36 | 27.59 |

| Türkiye | 24.76 | 25.16 | 24.46 | 24.96 | 25.13 | 24.68 | 23.98 | 23.1 | 23.86 |

| United Kingdom | 32.12 | 31.95 | 31.66 | 31.84 | 32.43 | 32.87 | 32.89 | 32.72 | 32.77 |

| United States | 23.92 | 25.48 | 25.88 | 26.22 | 25.88 | 26.79 | 24.89 | 24.97 | 25.54 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

The tax to GVA ratio (The State Statistics Service of Ukraine 2020 and our own calculation).

Table A2.

The tax to GVA ratio (The State Statistics Service of Ukraine 2020 and our own calculation).

| NACE Code | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | A | 6.98 | 6.33 | 5.60 | 6.21 | 11.59 | 16.15 | 14.33 | 16.05 | 16.38 |

| Mining and quarrying | B | 44.12 | 40.83 | 46.62 | 61.58 | 54.14 | 52.27 | 47.55 | 46.81 | 58.08 |

| Manufacturing | C | 39.45 | 42.95 | 34.14 | 34.20 | 38.56 | 37.34 | 38.69 | 39.41 | 43.75 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | D | 62.64 | 55.80 | 46.91 | 43.59 | 48.40 | 51.51 | 36.48 | 45.18 | 43.48 |

| Water supply, sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | E | 27.92 | 38.14 | 31.67 | 34.28 | 39.51 | 41.62 | 42.48 | 42.07 | 43.22 |

| Construction | F | 22.56 | 25.40 | 21.59 | 23.98 | 26.10 | 24.88 | 24.71 | 23.40 | 21.76 |

| Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | G | 20.72 | 21.22 | 17.87 | 20.14 | 22.73 | 20.06 | 21.59 | 23.19 | 22.39 |

| Transportation and storage | H | 23.23 | 17.29 | 17.32 | 19.64 | 27.54 | 26.02 | 23.87 | 25.27 | 27.22 |

| Accommodation and food service activities | I | 21.02 | 21.44 | 16.94 | 17.37 | 19.76 | 24.32 | 22.78 | 19.97 | 18.57 |

| Information and communication | J | 14.35 | 25.30 | 23.04 | 18.29 | 18.76 | 19.20 | 19.05 | 17.69 | 16.97 |

| Financial and insurance activities | K | 11.40 | 13.70 | 16.19 | 25.14 | 29.33 | 21.86 | 21.38 | 33.86 | 41.92 |

| Real estate activities | L | 26.91 | 8.09 | 7.52 | 8.00 | 9.63 | 9.17 | 9.04 | 9.00 | 8.41 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | М | 13.32 | 40.63 | 41.05 | 52.24 | 47.16 | 36.14 | 46.81 | 44.49 | 66.49 |

| Administrative and support service activities | N | 16.61 | 21.98 | 22.29 | 21.23 | 22.41 | 25.02 | 23.41 | 23.27 | 24.85 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | O | 19.59 | 17.79 | 16.19 | 18.00 | 19.90 | 20.97 | 20.16 | 19.34 | 19.02 |

| Education | P | 5.58 | 5.49 | 5.49 | 5.85 | 7.83 | 7.84 | 8.01 | 8.77 | 9.26 |

| Human health and social work activities | Q | 10.58 | 11.34 | 11.10 | 11.59 | 14.52 | 16.51 | 19.19 | 18.31 | 18.28 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | R | 7.80 | 10.14 | 10.37 | 12.43 | 14.21 | 15.16 | 15.50 | 14.87 | 14.37 |

Appendix C

Table A3.

The first modernized cash effective tax rate of agricultural companies: our own calculation.

Table A3.

The first modernized cash effective tax rate of agricultural companies: our own calculation.

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01.11 Growing of cereals (except rice), leguminous crops and oil seeds | |||||||||

| PrJSC “Agricultural company” “Verbivske” | 4.20 | 9.85 | 2.43 | 5.05 | 4.50 | 6.66 | 7.66 | 8.16 | 10.91 |

| PJSC “Agricultural company” “8 Bereznia” | 3.18 | 4.08 | 3.20 | 3.18 | 6.11 | 7.25 | 9.22 | 9.71 | 11.23 |

| PrJSC “Agricultural company named after H.S. Skovoroda” | 3.17 | 4.33 | 4.46 | 0.83 | 7.87 | 5.35 | 6.94 | 8.07 | 9.51 |

| PrJSC “Ahrofort” | 20.70 | 12.55 | 20.13 | 19.35 | 18.49 | 6.30 | 6.11 | 12.70 | 4.64 |

| PJSC “Blok Ahrosvit” | 9.24 | 3.79 | 8.11 | 2.50 | 4.08 | 3.06 | 4.80 | 9.34 | 26.56 |

| PrJSC “Iuh-Ahro” | 7.78 | 10.68 | 7.64 | 8.67 | 5.32 | 15.20 | 15.73 | 14.36 | 14.65 |

| PrJSC “Agro-industrial association” “Krasnyi Chaban” | 4.96 | 9.59 | 26.16 | 34.56 | 21.73 | 69.33 | 24.16 | 22.81 | 24.67 |

| PrJSC “Ahro-Soiuz” | 0.09 | 1.84 | 1.18 | 2.23 | 5.50 | 5.31 | 7.69 | 7.12 | 6.99 |

| PrJSC “Zernoprodukt MKHP” | 7.14 | 3.78 | 1.58 | 2.82 | 13.13 | 6.66 | 4.74 | 7.73 | 3.99 |

| PrJSC “Ekoprod” | 5.76 | 6.06 | 3.79 | 5.15 | 7.09 | 9.62 | 13.23 | 25.61 | 23.58 |

| PrJSC “Nyva-Plius” | 3.29 | 3.72 | 3.72 | 2.92 | 7.49 | 13.44 | 11.33 | 6.73 | 6.06 |

| PrJSC “Agricultural company named after Shevchenko” | 1.31 | 2.02 | 1.43 | 6.70 | 15.62 | 160.13 | 3.29 | 5.42 | 1.56 |

| PJSC “Andrushivske” | 1.24 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 0.97 | 9.48 | 16.81 | 11.55 | 6.36 | 6.11 |

| PrJSC “Sad” | 4.78 | 3.69 | 2.37 | 2.66 | 3.53 | 5.90 | 8.88 | 8.43 | 7.76 |

| PJSC “Radsad” | 5.87 | 7.61 | 6.07 | 5.83 | 9.45 | 6.74 | 14.72 | 12.64 | 16.46 |

| PrJSC “Ielyzavetivske” | 4.3 | 6.5 | 4.1 | 6.9 | 8.5 | 10.5 | 18.6 | 18.7 | 13.1 |

| PrJSC “SH Nadiia Nova” | 1.34 | 2.08 | 2.58 | 3.32 | 8.99 | 13.24 | 2.44 | 0.87 | 1.06 |

| PrJSC “APK-Invest” | −5.97 | −1.22 | 1.65 | 1.50 | 5.53 | 9.72 | 8.43 | 9.65 | 9.48 |

| PrJSC “Ukrzernoimpeks” | 7.29 | 7.00 | 5.77 | 7.77 | 10.73 | 16.60 | 20.31 | 14.48 | 18.22 |

| PrJSC “Food company” “Podillia” | 6.45 | 2.40 | 1.95 | 2.25 | 9.62 | −1.11 | −0.87 | 1.14 | 3.95 |

| LLC “Burat-Ahro” | 3.08 | 4.06 | 2.85 | 2.10 | 4.86 | 4.82 | 8.82 | 5.94 | 5.81 |

| PJSC “Sad” | 1.41 | 3.34 | 2.31 | 4.44 | 11.60 | 9.65 | 8.81 | 9.04 | 5.86 |

| 01.21 Growing of grapes | |||||||||

| PrJSC “Peremoha” | 0.19 | 0.19 | 4.33 | 2.07 | 5.67 | 5.10 | 4.85 | 3.67 | 10.12 |

| 01.24 Growing of pome fruits and stone fruits | |||||||||

| PrJSC “Druzhba-VM” | 2.77 | 2.90 | 1.54 | 1.34 | 4.54 | 6.13 | 7.03 | 9.65 | 4.22 |

| PrJSC “Sad Ukrainy” | 5.21 | 7.46 | 8.43 | 6.91 | 20.25 | 18.26 | 23.50 | 26.35 | 25.43 |

| PrJSC “Sad Podillia” | 13.10 | 6.49 | 10.26 | 5.39 | 3.63 | 15.44 | 20.53 | 10.23 | 23.10 |

| PrJSC “Zelenyi hai” | 17.83 | 0.43 | 1.11 | 0.41 | 0.89 | 1.30 | 2.07 | 98.52 | 194.49 |

| 01.41 Raising of dairy cattle | |||||||||

| PrJSC “Breeding factory” “Litynskyi” | 2.98 | 2.06 | 1.80 | 0.67 | 4.66 | 9.00 | 3.95 | 7.11 | 4.17 |

| 01.46 Raising of swine/pigs | |||||||||

| PJSC “Agricultural combine” “Kalyta” | 1.68 | 1.40 | 11.78 | 1.82 | 5.56 | 5.48 | 6.48 | 1.72 | 2.29 |

| PrJSC “Agricultural company” “Slobozhanskyi” | 7.60 | 4.23 | 1.46 | 1.43 | 1.96 | 13.25 | 3.65 | 4.38 | 4.54 |

| PrJSC “Bakhmutskyi ahrarnyi soiuz” | 7.14 | 3.78 | 2.21 | 1.97 | 2.09 | 3.32 | 4.97 | 5.73 | 4.84 |

| 01.47 Raising of poultry | |||||||||

| PrJSC “Agricultural company” “Berezanska ptakhofabryka” | 0.04 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 0.65 | −3.21 | 4.78 | - | 5.79 | 20.78 |

| PrJSC “Myronivska ptakhofabryka” | 0.95 | 1.41 | 0.64 | 0.77 | 3.78 | 5.08 | - | 2.31 | 1.66 |

| PrJSC “Dianivska ptakhofabryka” | 1.45 | 1.04 | 1.29 | 1.84 | 3.55 | 5.45 | 5.23 | 5.30 | 4.63 |

| PrJSC “Oril-Lider” | 1.18 | 0.67 | 0.82 | 1.35 | 3.41 | 1.90 | 1.39 | 4.34 | 3.93 |

| 01.50 Mixed farming | |||||||||

| PrJSC “Agricultural company” “Chornomorska perlyna” | 5.94 | 5.33 | 3.73 | 1.87 | 3.94 | 4.07 | 4.29 | 2.98 | 3.33 |

| 03.22 Freshwater aquaculture | |||||||||

| PrJSC “Khmelnytskyi Vyrobnyche Silskohospodarsko-Rybovodne Pidpryiemstvo” | 24.16 | 19.19 | 43.73 | 39.58 | 224.51 | 104.48 | 627.87 | 303.40 | 41.03 |

| PrJSC “Kryvyi Rih rybovodne silskohospodarske Pidpryiemstvo” | 28.63 | 5.31 | 9.31 | 9.96 | 22.20 | 35.26 | 58.37 | 56.00 | 38.66 |

References

- Abramova, Alla, Anton Chub, Dmytro Kotelevets, Oleksandr Lozychenko, Kateryna Zaichenko, and Olga Kupchyshyna. 2021. Regulatory policy on ensuring sustainability of tax revenues of EU-28 countries. Laplage em Revista (International) 7: 447–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuselidze, George, and Mamuka Surmanidze. 2020. Analysis of Performance Efficiency of Legal Entities of Public Law and Non-Profit Legal Entities under the Central and Local Government Bodies: In Terms of the Transformation of Georgia with the EU. Paper presented at 5th International Conference on European Integration, Ostrava, Czech Republic, November 3–4; pp. 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy Hazır, Ç. 2019. Determinants of Effective Tax Rates in Turkey. Journal of Research in Business 4: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachas, Pierre, Anne Brockmeye, Roel Dom, and Camille Semelet. 2022. Effective Tax Rates and Firm Size: The Case of Ethiopia. World Bank: Development Research Group. Available online: https://www.taxdev.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/TaxDev_Effective_Tax_Rates_Ethiopia_0.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Bahl, Roy W. 1971. A Regression Approach to Tax Effort and Tax Ratio Analysis. IMF Economic Review 18: 570–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, Keshab, Dung Thi Kim Nguyen, and Chan Van Nguyen. 2019. Impacts of Direct and Indirect Tax Reforms in Vietnam: A CGE Analysis. Economies 7: 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blechová, Beata, and Ivana Barteczková. 2008. Comparison of the Methodologies for Assessing Effective Tax Burden of Corporate Income Used in European Union. Slezska Univerzita-Obchodne Podnikatelska Fakulta University of Silesia-School of Business Administration. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/17822/ (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Boiko, Svitlana, and Inna Sytnyk. 2018. Differentiation of tax burden in Ukraine by types of economic activity. Evropský Časopis Ekonomiky a Management 4: 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Boiko, Svitlana, and Oksana Drahan. 2017. Decomposition of Macrofinancial risks of Agricultural Enterprises. Odessa National University Herald. Economy 22: 111–15. [Google Scholar]

- Boiko, Svitlana, Olha Varchenko, and Oksana Drahan. 2019. Structural asymmetry of tax revenues of the Consolidated budget Ukraine for KTEA 009: 2010. Financial and Credit Activity Problems of Theory and Practice 1: 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsall, Samuel B., Kevin Koharki, and Luke Watson. 2017. Deciphering Tax Avoidance: Evidence from Credit Rating Disagreements. Contemporary Accounting Research 34: 818–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubanić, Marijana, and Hrvoje Šimović. 2021. Determinants of the effective tax burden of companies in the Telecommunications activities in the Republic of Croatia. Zagreb International Review of Economics & Business 24: 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras, Marco, Chandu Dachapalli, and Giulia Mascagni. 2017. Effective Corporate Tax Burden and Firm Size in South Africa: A Firm-Level Analysis. WIDER Working Paper 2017/162. Available online: https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/Publications/Working-paper/PDF/wp2017-162.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Celikay, Ferdi. 2020. Dimensions of Tax Burden: A Review on OECD Countries. Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science 25: 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelliah, Raja J., Hessel Baas, and Margaret R. Kelly. 1975. Tax Ratios and Tax Effort in Developing Countries, 1969–1971. IMF Economic Review 22: 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalamagas, Basil, Panagiotis Palaios, and Stefanos Tantos. 2019. A New Approach to Measuring Tax Effort. Economies 7: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, Mihir, and Dhammika Dharmapala. 2009. Corporate Tax Avoidance and Firm Value. The Review of Economics and Statistics 91: 537–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, Anirudh, Liangbo Ma, and Maria H. Kim. 2020. Effect of Corporate Tax Avoidance Activities on Firm Bankruptcy Risk. Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics 16: 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyreng, Scott D., Michelle Hanlon, and Edward L. Maydew. 2008. Long-run corporate tax avoidance. The Accounting Review 83: 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyreng, Scott D., Michelle Hanlon, and Edward L. Maydew. 2019. When does tax avoidance result in tax uncertainty? The Accounting Review 94: 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Alexander, Adrian Kubata, and Terry Shevlin. 2021. The Decreasing Trend in U.S. Cash Effective Tax Rates: The Role of Growth in Pre-Tax Income. The Accounting Review 96: 231–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Alexander, Casey M. Schwab, and Terry Shevlin. 2016. Financial Constraints and Cash Tax Savings. The Accounting Review 91: 859–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltony, Nagy M. 2002. Measuring Tax Effort in Arab Countries. Economic Research Forum Working Papers No. 0229. Available online: https://erf.org.eg/app/uploads/2017/05/0229-ElTony.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Fernández-Rodríguez, Elena, and Antonio Martínez-Arias. 2014. Determinants of the Effective Tax Rate in the BRIC Countries. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 50: 214–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Rodríguez, Elena, Roberto García-Fernández, and Antonio Martínez-Arias. 2019. Influence of Ownership Structure on the Determinants of Effective Tax Rates of Spanish Companies. Sustainability 11: 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghura, Dhaneshwar. 1998. Tax Revenue in Sub-Saharan Africa: Effects of Economic Policies and Corruption. IMF Working Paper, WP/98/135. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/wp98135.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Guenther, David A., Steven R. Matsunaga, and Brian M. Williams. 2017. Is Tax Avoidance Related to Firm Risk? The Accounting Review 92: 115–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Sanjay, and Kaye Newberry. 1997. Determinants of the variability in corporate effective tax rates: Evidence from longitudinal data. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 16: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, Michelle, and Shane Heitzman. 2010. A review of tax research. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50: 127–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Iftekhar, Chun Keung Hoi (Stan), Qiang Wu, and Hao Zhang. 2014. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder: The effect of corporate tax avoidance on the cost of bank loans. Journal of Financial Economics 113: 109–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchens, Michelle, Sonja O. Rego, and Williams Brian. 2020. Tax Avoidance, Uncertainty, and Firm Risk. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Otto H., and Christoph Spengel. 1999. The Effective Average Tax Burden in the European Union and the USA: A Computer-Based Calculation and Comparison with the Model of the European Tax Analyzer. Zew Discussion Paper No. 99-54. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=376221 (accessed on 15 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Janova, Jitka, David Hampel, and Danuše Nerudova. 2019. Design and validation of a tax sustainability index. European Journal of Operational Research 278: 916–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, Boudewijn, and Willem Buijink. 2000. Determinants of the Variability of Corporate Effective Tax Rates (ETRs): Evidence for the Netherlands. Research Memorandum 046. Maastricht: Maastricht Research School of Economics of Technology and Organization, Maastricht University. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasianenko, Liubov M., Nataliа I. Atamanchuk, Oksana O. Slastonenko, Tetiana B. Sholkova, and Yuliia O. Fomenko. 2019. Legal Regulation of Value Added Tax Payers in Ukraine. Journal of Advanced Research in Law and Economics 5: 1459–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kéïta, Kouramoudou, and Hannu Laurila. 2021. Corruption and Tax Burden: What Is the Joint Effect on Total Factor Productivity? Economies 9: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolomiiets, Pavlo V. 2018. The Current State of Tax Administration in Ukraine: An Analytical Review of Terminology. Journal of Advanced Research in Law and Economics 8: 2448–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostornoi, Serhii, Olena Yatsukh, Volodymyr Tsap, Ivan Demchenko, Natalia Zakharova, Maksym Klymenko, Oleksandr Labenko, Victoriya Baranovska, Zbigniew Daniel, and Wioletta Tomaszewska-Górecka. 2021. Tax burden of agricultural enterprises in Ukraine. Agricultural Engineering 25: 157–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuthold, Jane H. 1991. Tax Shares in Developing Economies: A Panel Study. Journal of Development Economics 25: 173–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkovets, Nataliia, Victoria Ilchenko, Svitlana Boiko, Viktoriia Masalitina, and Nataliia Tesliuk. 2023. Risk-Oriented Approach to Financial Security of Motor Transport Enterprises. In Explore Business, Technology Opportunities and Challenges after the Covid-19 Pandemic. Edited by B. Alareeni and A. Hamdan. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. Cham: Springer, vol. 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Hee Young. 2018. The Effects of Sustainable Tax Strategies on Value Relevance. The Institute of Management and Economy Research 9: 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Hee Young, and Sung Jong Park. 2021. Relationship between Corporate Sustainability Management and Sustainable Tax Strategies. Sustainability 13: 7429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfoudh, Naoufel, and Imen Gmach. 2021. The Effects of Fiscal Effort in Tunisia: An Evidence from the ARDL Bound Testing Approach. Economies 9: 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascagni, Giulia, and Andualem Mengistu. 2019. Effective tax rates and firm size in Ethiopia. Development Policy Review 37: 248–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, Sean T., Stevanie S. Neuman, and Thomas C. Omer. 2013. Sustainable Tax Strategies and Earnings Persistence (Working Paper SSRN). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1950378 (accessed on 25 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Finance of Ukraine. 2020. Statistical Yearbook “Budget of Ukraine”. Available online: https://www.mof.gov.ua/uk/statistichnij-zbirnik (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Minton, Bernadette, Catherine M. Schrand, and Beverly R. Walther. 2002. The role of volatility on forecasting. Review of Accounting Studies 7: 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerudova, Danuse, Jitka Janova, David Hampel, Marian Dobranschi, and Petr Rozmahel. 2019. Sustainability of the Taxation Systems in the EU: A Proposal of an Evaluation Model. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5c1f6e730&appId=PPGMS (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Nicodeme, G. 2001. Computing Effective Corporate Tax Rates: Comparisons and Results European Economy. Economic Papers 153. Brussels: European Commission, Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs, June. [Google Scholar]

- Nurwati, P., and Nawang Kalbuana. 2021. Influence of firms size, exchange rate, profitability and tax burden on transfer pricing. International Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting Research (IJEBAR) 5: 967–80. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2013. Fiscal sustainability. In Government at a Glance 2013; Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2013-11-en (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- OECD Data. 2020. Tax Revenue. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/tax/tax-revenue.htm (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Our Common Future. 1987. World Commissionon Environment and Development. Technical Report. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Paientko, Tetiana, and Valeriy Oparin. 2020. Reducing the Tax Burden in Ukraine: Changing Priorities. Central European Management Journal 28: 98–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poltorak, Anastasiya, and Yuriy Volosyuk. 2016. Tax risks estimation in the system of enterprises economic security. Economic Annals 158: 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, Mahesh C. 2006. Tax Efforts and Taxable Capacity of Central and State Government. Economic and Political Weekly 25: 747–55. [Google Scholar]

- Salaudeen, Yinka Mashood, and Tayibat A. Atoyebi. 2018. Tax Burden Implication of Tax Reform. Open Journal of Business and Management 6: 761–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Yoojin, and Jungmi Park. 2022. Differences in Tax Avoidance According to Corporate Sustainability with a Focus on Delisted Firms. Sustainability 14: 6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbachawene, Method S. 2018. Improving Tax Revenue Performance in Tanzania: Does Potential Tax Determinants Matters? Journal of Finance and Economics 6: 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sybiryanka, Yuliia, and Anna Pyslytsya. 2016. Peculiarities of territorial and sectoral localization of large taxpayers in Ukraine. Scientific Works of NDFI 3: 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tax Policy Briefing Book. 2010. Washington, DC: Urban Institute and Brookings Institution.

- The State Statistics Service of Ukraine. 2020. Statistical Yearbook of Ukraine. Available online: https://ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/Arhiv_u/01/Arch_zor_zb.htm (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- The World Bank Group. 2006. Sector Study of the Effective Tax Burden. FIAS. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/297601468104634538/Sector-study-of-the-effective-tax-burden (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- The World Bank Group. 2015. Metadata Glossary. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/world-development-indicators/series/NY.GDP.FCST.KD (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- The World Bank Group. 2020. Inflation, Consumer Prices (Annual %)—Ukraine. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FP.CPI.TOTL.ZG?end=2020&locations=UA&start=1993&view=chart (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. 2010. Tax Code of Ukraine on December 2. No. 2755-VI. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2755-17?sp=:max50:nav7:font2&lang=en#Text (accessed on 13 October 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).