Abstract

This article describes the evolution of the regulation of agricultural trade and analyses key aspects of the negotiations of the Uruguay and Doha Rounds, in which the least developed countries managed to make the final outcome of the negotiations conditional on progress in the liberalisation of agricultural trade. Four Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Uruguay) participated in the lobbying groups set up in both Rounds with the aim of defending their interests against the agricultural and protectionist policies of developed countries. Using specialised databases on international trade, this paper describes the consequences of these negotiations for the foreign agricultural trade of the countries that actively participated in them, with particular reference to the evolution of European and Latin American trade balances. The results of the research show how Latin American countries have become one of the world’s main exporters of oilseeds and sugar, accounting for a third and a quarter of world exports, respectively. In contrast to the deterioration of the European trade balance, during the period analysed the aggregate trade surplus of Latin American countries increased from USD 4458.75 to 49,656.52 million.

1. Introduction

In order to understand the evolution of international agricultural trade, it is essential to bear in mind the pressures exerted by the least developed countries in favour of greater liberalisation. Although this is a demand widely shared by Latin American countries, the fact is that, of this group of countries, Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Uruguay are the only ones that—first in the Uruguay Round and then in the Doha Round—participated in the pressure groups created in both forums in favour of greater openness in agricultural trade and against the protectionism and agricultural policies applied by some of the more developed countries. As will be described, the demands of the countries advocating for the liberalisation of agricultural trade clashed with the opposition of the more developed countries; in particular, with those of a European Union (EU) whose agricultural policy was characterised, for much of the period analysed, by its double condition of being productivist and protectionist. In fact, various authors (Bonete 1994; Compés and García 2005; Flores 2006; Compés et al. 2007; García et al. 2008) have no hesitation in linking the reform of the Community Agricultural Policy (CAP) to the commitments that the European Community was obliged to assume in the course of these negotiations.

In their work on the regulation of international agricultural trade and its implications for the CAP, Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2021) examined the interrelationship between the two issues. Based on the conclusions obtained, this research aims to broaden the scope of this analysis, focusing on the consequences that the negotiations that took place during the Uruguay and Doha Rounds had for the four Latin American countries that actively participated in both forums. To this end, the aim is to analyse the historical evolution of this process of agricultural trade liberalisation, the factors that conditioned the negotiations held, the role of the pressure groups formed to benefit the interests of the least developed countries and the effects that the agreements reached had on the trade of all the countries that participated in these negotiations.

From a theoretical point of view, the Uruguay Round negotiations have been studied by a wide range of authors. Although this issue has also been analysed in countless empirical studies, many of them focus on static analyses of the impact that the trade agreements would have on the countries involved in the negotiations. Examples of this could be the research by Goldin and Van der Mensbrugghe (1995) when they measure the impact that tariff reduction commitments would have on the world’s least developed countries; Brandão and Martin’s (1993) or Sadoulet and De Janvry’s (1992) interest in the impact of the liberalisation of agricultural trade on this same group of countries; Hathaway and Ingco (1995) when they try to assess the impacts of agricultural trade liberalisation; and Ingco (1997) and Anderson and Neary (1994, 1996), who conclude that, for the least developed countries, the benefits derived from the trade agreements reached in the Uruguay Round will depend on how these types of countries are able to advance in the economic reforms that allow for the liberalisation of their trade flows.

Aksoy and Beghin (2005) and Koning and Pinstrup-Andersen (2007) maintain their interest in the impact that the liberalisation of agricultural trade would have on the least developed countries but extend the time horizon of their research to the negotiations held at the beginning of the Doha Round. However, despite the multitude of existing studies, empirically, there are fewer studies that attempt to analyse the consequences of the trade commitments adopted in these negotiating rounds from a long-term perspective in an attempt to assess whether the commitments assumed entail a structural reordering of international agricultural trade. The second part of this research is a modest contribution based on this latter perspective. In this endeavour, this work takes as a reference the studies of other authors who, specialising in the analysis of international agricultural trade, approach their work from a long-term perspective; this is the case, for example, in the research by Aparicio et al. (2009), Serrano and Pinilla (2010, 2014) or Baiardi et al. (2015), who studied the evolution of agricultural exports, as well as their conditioning factors, and predicted an increase in competition between emerging and developed countries for the export of this type of product.

Beyond the interest aroused by the impacts of the negotiations in these two important forums, there are many other issues related to international trade that are the subjects of analysis: sectoral analyses of international trade, the impact of trade on the environment and factors related to the demand for food are just some of the lines of research currently open on the subject.

From a sectoral point of view, international trade is an inexhaustible field of research that focuses on both products and geographical areas. Examples of this are the work of Parejo-Moruno et al. (2020) on the international trade of garlic; García et al. (2019) and De Pablo et al. (2016, 2017), who analyse the international competitiveness of cherries, almonds and olive oil; and Parejo and Rangel (2016), who are interested in the analysis of the world market for table olives, to give just a few examples concerning international agricultural trade.

The impact of trade on the environment is a controversial issue that has attracted the research interest of many authors. Many of those who approach this question try to analyse the impacts that such activity produces on the environment. Pendrill et al. (2019) and Henders et al. (2015) study the pressure of international trade on forest resources in less developed countries; Aichele and Felbermayr (2015) and Jiborn et al. (2018) are interested in analysing the impact of carbon emissions derived from international trade; in a similar vein, Xu et al. (2020) analyse the impacts of such activity on the sustainable development of the planet. Another interesting area of study related to this subject focuses on the analysis of the effects that trade agreements may have on the planet’s environment and on the natural resources of less developed countries (Frey 2016; Bastiaens and Postnikov 2017; Martínez-Zarzoso and Oueslati 2018; Brandi et al. 2020; Heyl et al. 2021; and Tang et al. 2022 are just some examples of this type of work).

With regard to the analysis of the factors that condition international trade, the work of Coyle et al. (1998) and Rimmer and Powell (1996) on the factors that condition world food demand stands out, as does that of Baier and Bergstrand (2001, 2007) analysing the role that free trade agreements, or reductions in tariffs and transport costs, can have on the growth of international trade.

2. A Historical Overview of the Regulation of International Agricultural Trade

2.1. International Trade Regulation in the Post-War Period

Following the Second World War, the Trade and Employment Conference held in Havana in 1946 was a milestone in the definition of new international trade relations. Those who met in Havana were well-aware of the damage done to the international economy by the protectionist measures adopted by various countries during the 1930s. The aim of the conference was to define an agreement that would enable the participating countries to make progress in opening up international trade. It was in this context that the idea of creating an International Trade Organisation (ITO) was born, but it never came into existence as such. Instead, a year after the Havana Conference, 23 of the participating countries signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which was intended to fulfil part of the tasks assigned to the frustrated organisation.

Therefore, given the reticence towards the ITO on the part of some of the participants in the Havana Conference, it is necessary to understand the origin of the GATT as a transitory solution. Nevertheless, this agreement was key to the liberalisation of international trade between 1948 and 1995, to such an extent that some consider GATT to be the “largest trade agreement in history” (Prieto and Esteruelas 1989, p. 138). After the creation of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 1995, the GATT lost relevance but, before then, under the auspices of this Agreement, eight negotiating rounds were held. In contrast to the Uruguay Round (1986–1994), in which trade in agricultural products was the subject of intense negotiations, in the seven previous rounds, commitments in favour of trade liberalisation were basically focused on industrial products.

In the first seven GATT rounds, the influence of the developed countries managed to focus the negotiations on industrial products; on the other hand, it should not be forgotten that, after the Second World War, there was a major problem of food shortages, so the interests of agricultural exporters did not clash and the liberalisation of this type of trade was not a matter for discussion. As Sancho (1991) points out, during this long period, it was only when the agricultural policies promoted by different countries began to reverse the situation described above, and when the implementation of the CAP generated major misgivings among the main agricultural exporters, that a certain amount of debate on international agricultural trade began to take place. However, the discussions that took place hardly served to ratify the exceptional nature of agriculture and the peculiarities of this sector within international trade. This was also helped by the fact that the criticisms made by the US were undermined by its own actions in agricultural matters. US protectionism in agricultural trade dates back to 1955, when the US requested several agricultural exceptions (known in GATT jargon as “waivers”) within the GATT.

Years later, the concessions granted to the US would be used by other countries to justify the same course of action; in fact, it is likely that the productivist and protectionist orientation that characterised the CAP in its origins could not have been the same without the US precedent. At the end of the 1970s, the “infernal logic” (Moyano 1998) derived from an agricultural policy that offered European producers guaranteed prices regardless of the functioning of the markets led to large surpluses and a significant budgetary problem. The approval of export subsidies to eliminate these surpluses not only multiplied their economic cost but also generated intense criticism from those other countries whose agricultural exports on international markets were damaged by the existence of Community subsidies (Etxezarreta et al. 1995).

Despite the fact that, in the Dillon Round of the GATT (1960–1961), the USA and the EEC had agreed on the external aspect of the CAP, there were constant clashes between the two—and with the rest of the countries exporting agricultural products. These countries denounced the fact that European agricultural protectionism and export subsidies distorted the prices of agricultural products on international markets (causing them to collapse) and expelled from them other producers who, being more efficient than Europeans, did not have the subsidies and support of their respective national governments.

2.2. The Uruguay Round and the Issue of Agricultural Trade

In 1996, in Punta del Este (Uruguay), what was to be the last GATT negotiating round—and the most complex of all those that had been held to that date—got underway. For the first time, agricultural trade liberalisation was one of the key issues in the negotiations. Although, among the developed countries, those that formed part of the EEC were not the only ones to support their agriculture, in these negotiations the protectionism implicit in the CAP was the object of intense criticism from various quarters, including the USA and the CAIRNS group.

The US approach to the Uruguay Round could be described as hypocritical given that, as has been explained, the US had a long history of protection measures for its farmers; nevertheless, in these negotiations, the US had no difficulty in being very belligerent towards the CAP’s protectionist measures. Moreover, in these criticisms, the US was able to focus the debate on those European protection measures that least conditioned its own actions, such as border protection measures and export subsidies (San Juan 1991).

The emergence of the CAIRNS group and their ability to influence the negotiations was an important development in the Uruguay Round. The CAIRNS group is made up of a number of countries characterised by their competitiveness in international agricultural markets: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Hungary, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand and Uruguay. At a certain point in the negotiations, the position of these countries in favour of the liberalisation of international agricultural trade even led them to make progress on trade in services or intellectual property rights conditional on specific commitments by the EEC regarding agricultural products.

In order to understand the Uruguay Round negotiations, it is necessary to be aware that, in agricultural matters, protectionism can be implemented through various policies, such as (Gómez Torán 1991): (a) price support policies, which could include border protection, export subsidies and domestic price maintenance; (b) direct aid, which seeks to maintain farmers’ incomes without altering price formation in the markets; and (c) other support measures, including support for marketing, environmental incentives, agricultural insurance, tax benefits, etc.

In the Uruguay Round, participating countries agreed to define their support instruments and to classify them into three categories or “boxes”:

- The “Amber Box” would include agricultural support schemes that are prohibited due to their distorting effects on agricultural markets; such support would have to be reduced by the agreed percentages. This category would include domestic price support instruments; i.e., border protection, export subsidies and guaranteed prices;

- The “Blue Box” would include direct aid partially decoupled from production, as well as programmes aimed at limiting production. The creation of this “box” was a compromise solution to unblock the Uruguay Round negotiations; in fact, its existence was conceived as a temporary measure that would disappear in 2003;

- The “Green Box” would include aid permitted because it does not have distorting effects on international trade. This group would include aid for agricultural research, rural development, natural disasters and programmes aimed at environmental protection.

In the area of agricultural trade, the negotiations were marked by an intense confrontation between the position of the European countries participating in the integration process and most of the rest of the GATT signatory countries, represented especially by the belligerent attitude of the USA and the CAIRNS group. While the former ruled out the possibility of accepting any change in the regulation of international agricultural trade that would call into question their agricultural policy, the latter demanded the elimination, within a maximum period of ten years, of the aid included in the amber box; in other words, that which generated distorting effects on the formation of international agricultural prices (border protection and export subsidies) and which, paradoxically, had great relevance in the definition of the CAP (Millet 2005).

With regard to border protection, most of the GATT signatories demanded that the EEC tariffs be tariffed and progressively reduced. On the other hand, the existence of export subsidies had caused world prices for the most characteristic products of continental agriculture to reach lower levels than they would have been in the absence of these measures, thus harming agricultural exporters in the least developed countries. Tangermann (1987) quantifies this downward pressure on international prices for these products at 2–10%. Moreover, until the mid-1980s, the granting of these subsidies had allowed European producers to expel from international markets the agricultural exporters of other countries which, although more competitive than European producers, did not enjoy the same levels of protection and/or subsidies.

No country questioned the existence of domestic support (Marshall 1991) as long as it did not alter the formation of international agricultural prices or stimulate production. The importance that agricultural trade acquired in the Uruguay Round came as a surprise to a European Community whose agricultural policy was still characterised by its dual protectionist and productivist nature (García 1991). In order to unblock this situation, the EEC was forced to propose the first major reform of the CAP (European Commission 1991). Josling (1993) considers this reform to be the European response to the pressures exerted by the majority of the GATT signatory countries, and it implied the reduction of intervention prices in some of the main CMOs, which were precisely those linked to continental production. As a result of this reduction in intervention prices, Community prices would gradually come closer to international prices and this, in turn, led to a reduction in the much criticised export subsidies.

The changes introduced in the design of the CAP brought the Uruguay Round negotiations closer together. However, the consensus reached on agricultural trade by the EEC and the USA in November 1992 was fundamental to the finalisation of the negotiations; the commitments made would give shape to the so-called Blair House Agreement. Two years later, the signing of the so-called Marrakesh Agreement (1994) was the culmination of eight years of long negotiations.

It is true that, as far as export subsidies are concerned, the European concessions did have some relevance but, as far as border protection and agricultural support measures are concerned, the commitments from the Uruguay Round did not meet the initial expectations of the CAIRNS group. There was also the added problem that, after the end of the negotiations, the developed countries, in the fulfilment of these commitments, would employ tactics contrary to the spirit of the agreement, such as “dirty tariffication” or the fixing, as a basis for the commitments assumed, of years in which subsidies or tariffs had been higher. These practices were strongly denounced by agricultural exporters in the Doha Round.

However, Conde (2014), Rodrigo (2006) and García and Valdés (1997) agree that, apart from concrete results, the great achievement of the Uruguay Round was the complete incorporation of agricultural trade into the GATT negotiations, as well as the commitment made by the participating countries to consider the results of the found not as a point of arrival but as the starting point for future negotiations.

2.3. Liberalisation of Agricultural Trade in the Doha Round

In 2001, the WTO launched its first negotiating round, the so-called Doha Round. Faced with the criticisms that the globalisation process had aroused two years earlier at the Seattle Conference, the WTO sought to justify why new negotiations were necessary in order to make progress in the liberalisation of international trade. The argument chosen for this was the development of the poorest countries; hence, the objectives set out in its launching declaration were known as the “Development Agenda”; among these objectives, the one referring to the relevance that the liberalisation of agricultural trade should acquire in the negotiating process stood out.

In the same way that the CAIRNS group had a high profile in the Uruguay Round, in Doha, a group of less developed countries that were competitive in international markets but saw their production seriously damaged by developed countries formed a pressure group to define a common negotiating strategy (Mahía et al. 2005). This group of countries, which this research will refer to as the least developed agricultural exporters (LADEs), was composed of ten Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Guatemala, Mexico, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela), five African countries (Egypt, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania and Zimbabwe) and six Asian countries (China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Philippines and Thailand).

Created at the WTO Ministerial Conference held in Cancún (2003), the LDAEs assumed a relevance that “has changed the geopolitics of international agricultural negotiations” (Amorim 2006, p. 15), reducing the excessive influence that the two great agricultural superpowers—the US and the EU—had historically enjoyed. In fact, the origin of the LDAEs is linked to their confrontation with the strategy followed in Cancún by the Europeans and Americans who, in the early hours of the morning of the very day of the meeting’s closure (in an attempt to re-edit the Blair House Agreement that had brought them such good results in the Uruguay Round), announced that it had not been possible to reach an agreement on agricultural matters, but that there was a consensus between them that allowed negotiations to continue in another series of sectors that coincided with their interests. Led by Brazil, India and China, the LDAEs saw this announcement as an attempt by these two powers to make up for their mutual shortcomings in the area of agriculture, rejecting the aforementioned pact and the possibility of advancing in negotiations to liberalise trade in other sectors until an agricultural agreement was reached.

Despite the failure of Cancún and the fact that commitments to liberalise agricultural trade would not be made until the Hong Kong Conference (2005), the developed countries took advantage of this period to continue adapting their agricultural policies. In the case of Europe, the so-called Agenda 2000 (European Commission 1997) and Fischler Reform (European Commission 2002) deepened the process of adapting the CAP to the international context that began with the McSharry Reform (1992).

For Massot (2004), the Fischler Reform culminated in the evolution of the CAP from a policy of market intervention to an income policy based on direct aid whose decoupling and conditionality had an unequivocal intention: its imputation to the Green Box and the defence of the continuity of the Blue Box beyond 2003. In fact, for the EU, extending the existence of the Green Box and defending the multifunctionality of its agriculture as the fact that differentiates the European agricultural model from that of other countries in favour of greater liberalisation of agricultural markets (Massot 2000) were the main axes of its negotiating position in Cancún and Hong Kong.

The agreements stemming from the Hong Kong Ministerial Conference (2005) would entail: a further reduction in and greater conditionality for domestic support to the primary sector; lower barriers to access to developed country markets; and a target date of 2013 for the total elimination of export subsidies.

Each of these commitments posed different challenges for the developed agricultural powers: the US would have to reform its domestic agricultural support policies to adapt them to WTO requirements; for the EU, the main challenge was to reduce market access barriers, given that, after the reforms carried out, Europe was in a position to assume new commitments in the rest of the areas under negotiation (Rubio 2009). However, this did not prevent the European Commission from approving a new Communication, “Preparing for the Health Check of the CAP reform” (European Commission 2007), which laid the foundations for what, two years later, would be a new reform of the CAP that would be the culmination of the reforms begun in 1992.

After the Hong Kong Conference, the negotiations in the Doha Round came to a standstill, so that the only new developments in agricultural trade took place at the Conferences in Bali (2013) and Nairobi (2015), without the agreements reached in either of them representing substantial changes to the regulation of trade in agricultural products.

3. Research Methodology

The process of liberalisation of agricultural trade has been described above, and it remains to analyse the consequences of this process for the foreign agricultural trade of the countries, or groups of countries, that took part in it. To this end, we examine: (a) the participation of these countries in world exports of agricultural products, differentiating the Latin American countries under study, which are referred to in this part of the research as Latin America; and (b) the evolution of the European and Latin American trade balances.

In the previous section, the heterogeneity of the countries that made up the lobbies that played a leading role in the Uruguay and Doha Rounds was studied. The CAIRNS group was made up of agricultural exporting powers, within which there were highly developed countries and others that were not so developed; in the Doha Round, geographical and economic differences also existed between the countries that defended the position of the LDAEs. As stated in the introduction, the Latin American countries selected as the object of study are the only ones belonging to that geographical area that actively participated in both lobbies. Although this is a simplification, the comparison between the European and Latin American cases is a good example of the negotiating tensions that pitted the interests of developed countries against those of other less favoured countries in both rounds, and it may be a paradigmatic example of the restructuring of agricultural markets that has taken place with regard to continental products.

The methodological approach in this research takes as a reference that used by Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2021) in their analysis of the influence of the CAP reform process on the regulation of international agricultural trade. The aforementioned authors indicated that, in order to analyse the effects of the liberalisation of agricultural trade, it was necessary to take as a reference point those products that were most sensitive to the growing opening up of trade; in other words, those that benefited most from the subsidy and protection systems of developed countries. This is the case for continental products: arable crops (cereals, oilseeds and protein crops), beef, sugar and milk and its derivatives. Historically, these products have enjoyed greater protection from the founding countries of the European Economic Community (EEC). This is shown in Table 1, the data of which refer to the year prior to the launch of the Uruguay Round.

Table 1.

Community aid according to production in 1985 (millions of ECUs).

As a consequence of their greater international competitiveness, the export refunds from which Mediterranean products benefit are an “anecdote” compared to those received by continental products. As analysed above, the elimination of export subsidies was one of the great hobbyhorses of those who criticised the protectionist bias of the CAP. Therefore, continental productions were the most affected by the reduction in protection measures and represent a paradigmatic example of the consequences for European agriculture of taking on the challenge of the progressive liberalisation of its agricultural foreign trade.

Taking the European level as one of the variables in the analysis requires that the basis of the study refers to the same group of countries. After its third enlargement, the European integration process involved twelve partners (EU-12). However, using this group of countries as a reference is only partially compatible with the statistical series available from Eurostat. From 1995 onwards, after the integration of Austria, Finland and Sweden, the abovementioned database does not provide aggregated information for the EU-12. Therefore, data for the EU-12 are used for the period 1988–1994 and, from 1995 onwards, the scope of analysis focuses on the EU-15, for which Eurostat does offer aggregated data. The analysis of the effects that the agreements reached had on international agricultural trade requires the use of different statistical sources:

- (a)

- In order to analyse the world market share of the agricultural exports of the countries (or groups of countries) involved in the negotiations of the Uruguay and Doha Rounds, the trade statistics of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (https://comtrade.un.org/data/ (10 December 2021)) are used. Unlike other databases, this statistical base makes it possible to obtain, within the same search, the exports of all the countries under analysis (reporters) for the world market as a whole (partners). However, it also has some limitations: (1) it does not provide information aggregated by groups of countries (for example, the EU-15); and (2) it does not differentiate between intra- and extra-EU trade;

- (b)

- With regard to the analysis of the evolution of the trade balance, a distinction must be made between the study of this variable in the European case and in the case of the selected Latin American countries. For the latter, the same statistical source is used as in the previous point. However, in the analysis of the European balance, the Eurostat database (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (10 January 2020)) is used. This tool allows the creation of aggregates for the joint consultation of a group of countries; hence, it is very useful for the simultaneous analysis of the EU-15. Another interesting feature of this statistical database is that it differentiates between intra- and extra-EU trade (the data for the latter are used).

4. Interpretation and Discussion of the Research Results

Having outlined the process of liberalisation of international agricultural trade and defined the factors that conditioned the negotiations held for this purpose, it is now time to analyse their consequences in the evolution of the foreign agricultural trade of the countries, or groups of countries, that took part in these negotiations. As indicated in the introduction, in addition to the EU, the US, the CAIRNS group and the LDAEs, the proposed analysis includes a fifth aggregate comprising Chile, Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, the four Latin American countries that, both in the Uruguay Round and in the Doha Round, were active members of these two pressure groups in favour of greater openness in international agricultural trade.

4.1. World Market Shares of Agricultural Exports of the Countries Involved in the Negotiations

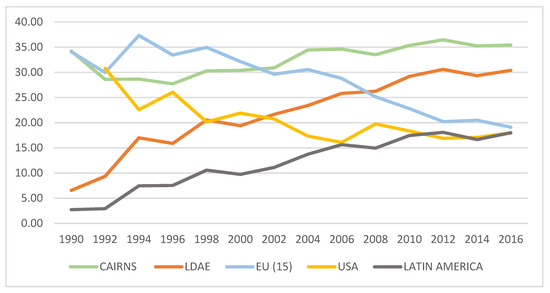

Figure 1 shows the export shares of the countries analysed in the international market. Several conclusions can be drawn from it:

Figure 1.

Country shares for world exports of continental products. Source: authors’ elaboration based on data obtained from UN Comtrade Database.

- (a)

- In the year in which the Uruguay Round ended (1994), European exports achieved their highest share of international markets (37.31%). Since then, their relative importance has declined inexorably to 19.10% in 2016. Europe’s “condescension” with the liberalisation of agricultural trade and the decrease in its share of world exports was not a process without its critics. These became more evident as the Doha Round progressed and CAP reforms were implemented in the 2000s. Thus, for example, Lamo de Espinosa (2008, p. 11) rhetorically asks: “Are we aware that (...) to anchor the CAP in food security, to cry out against the quadruple environmental, social, fiscal and monetary dumping, is to break with all the principles on which the WTO has been based and on which we are being expelled from the global market in favour of others?”;

- (b)

- A very similar trend to that of Europe was followed by US exports, which went from representing 30.8% of world exports in 1992 to almost 18% in 2016;

- (c)

- The declining importance of European and US exports contrasts with the growing importance of exports from developing countries. They have grown from a mere 6.5% of world exports in 1990 to just over 30% in 2016. Figure 1 shows that this group of countries has benefited most from the process of agricultural trade liberalisation;

- (d)

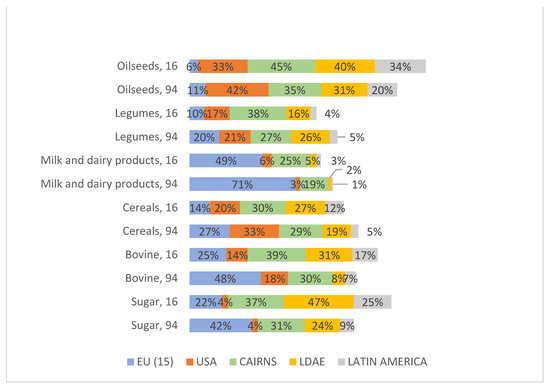

- The trend shown by the exports of the four Latin American countries analysed is unmistakable. From representing barely 3% of world exports at the beginning of the 1990s, they had practically the same market share as the US and the EU by the end of the series analysed. However, as Figure 2 shows, by product, there are significant differences in the relevance that countries hold in world exports. Among these differences, it is worth noting the cases of oilseeds and sugar and its derivatives, where exports from Latin American countries account, respectively, for a third and a quarter of world exports. In contrast, at the end of the series analysed, European dairy exports still accounted for almost half of world exports; in the same year, a third of oilseed exports still came from the USA.

Figure 2. Evolution by country of shares of world exports. Source: authors’ elaboration based on data obtained from UN Comtrade Database.

Figure 2. Evolution by country of shares of world exports. Source: authors’ elaboration based on data obtained from UN Comtrade Database.

4.2. Evolution of Latin American and European Agricultural Foreign Trade

This section compares the evolution of agricultural foreign trade in Latin American countries with the trend followed by European foreign trade (a paradigmatic example of the logic used by developed countries in agricultural stimulus policies). With respect to European evolution, this research starts from the results obtained by Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2021) in their analysis of the implications that the regulation of international agricultural trade has on CAP reforms.

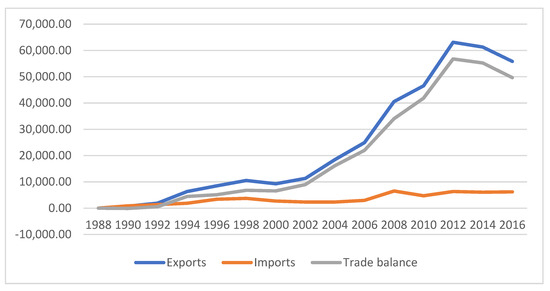

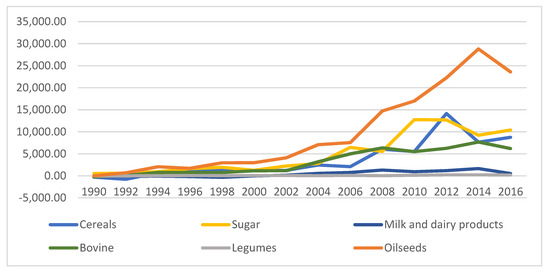

Figure 3 shows the trend in the aggregate foreign trade of the four Latin American countries, in which two periods can be distinguished: a first stage, covering the 1990s, in which, after the conclusion of the Uruguay Round, there was a timid increase in the trade surplus; and a second period, after the launch of the Doha Round, in which the exports of this group of countries soared and, with them, the surplus in their trade balance.

Figure 3.

Evolution of Latin America’s agricultural foreign trade in continental products (millions of USD, current prices). Source: authors’ elaboration based on data obtained from UN Comtrade Database.

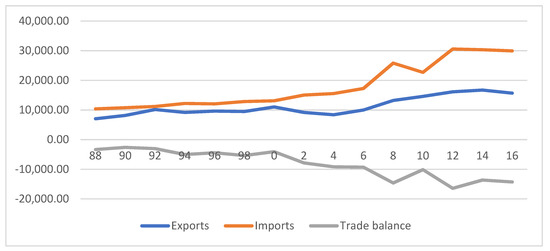

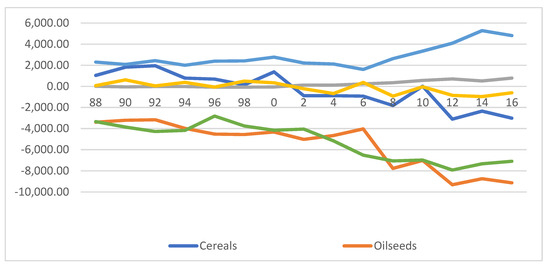

Despite showing a different trend, Figure 4 shows that, the two stages mentioned can also be distinguished in the evolution of European trade: a first period in which there were no changes in the evolution of the trade balance; and a second stage in which the trade deficit increased notably. Three factors can be highlighted to explain this evolution: (1) stagnation of European agricultural production—even valued at current prices, European production of continental products in 2010 was lower than in 1996; (2) reduction in exports—exports in 2004 were lower than in 1994; and (3) the harsh criticism made by less developed agricultural exporters at the launch of the Doha Round regarding the failure of developed countries to meet the commitments made in the Marrakesh Agreement to reduce entry barriers for primary products.

Figure 4.

Evolution of European agricultural foreign trade in continental products (millions of EUR, current prices). Source: Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2021).

As Figure 5 shows, in the case of the Latin American countries analysed, there were notable differences in the evolution of trade in the different products analysed. Above all, the trade surplus achieved in oilseeds stands out: in 2016, this type of crop accounted for almost half of the trade surplus of this group of countries. At the other end of the spectrum are pulses and dairy products, which, although not in deficit, made practically no contribution to the aggregate surplus.

Figure 5.

Latin American foreign trade balance for continental products (millions of USD, current prices). Source: authors’ elaboration based on data obtained from UN Comtrade Database.

In any case, regardless of the type of product and/or crop in question, Figure 5 seems to show that the launch of the Doha Round represents a change in the trend for the agricultural foreign trade of this group of Latin American countries. Valued at current prices, from the end of the Uruguay Round to the last year of the series analysed, their aggregate trade surplus increased from USD 4458.75 million to a total of USD 49,656.52 million.

The evolution of Latin American agricultural foreign trade contrasts with the European deficit. This export capacity of Latin American countries makes it possible to understand their incorporation into the lobbies for the liberalisation of agricultural trade in the Uruguay and Doha Rounds.

Finally, with regard to the trends in European foreign trade that characterise the products analysed, Figure 6 allows us to differentiate between the surplus in dairy products and their derivatives, the deficit in oilseeds and cattle and the unfavourable trend in cereals. In the period (1988–2016), in absolute terms and at current prices, the aggregate trade deficit in continental products was multiplied by four.

Figure 6.

Foreign trade balance for continental products (millions of EUR, current prices). Source: Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2021).

5. Conclusions

In the Uruguay Round, the liberalisation of agricultural trade took on an unexpected relevance and two positions confronted each other: on the one hand, the EU, whose agricultural and trade policies had a double protectionist and productivist bias; on the other hand, those countries, competitive agricultural exporters, whose growth in the international agricultural market was hampered by the policies applied by the former.

In the Uruguay Round, US support for the postulates of the CAIRNS group made it possible to reach an agreement that marked the beginning of a long process in favour of agricultural trade liberalisation that would no longer be reversed and which would again be the cause of friction at the first Ministerial Conferences of the Doha Round; it was at one of these meetings (Cancún 2003) that, given the reluctance of the developed countries to fulfil the commitments acquired in the area of agricultural trade, a pressure group made up of the least developed agricultural exporting countries (LDCs) emerged.

This long negotiation process had obvious consequences for the evolution of international agricultural trade. Although timidly in the second half of the 1990s and more intensely as the 2000s progressed, this research shows how the countries that make up the two aforementioned lobbies are increasing their share of the world market to the detriment of the EU and the US. At the end of the series analysed, the four Latin American countries accounted for 18.01% of world exports of continental products compared to 17.95% in the US and 19.10% in Europe. These figures are even more significant if one takes into account that, in 1992, the US and the EU each accounted for 30% of world exports of this type of product compared to just 2.5% for Latin American countries. However, within this general trend, as the research shows, there are notable differences between the different continental productions analysed.

Another consequence of the liberalisation of agricultural trade is the evolution of the trade balance between countries. The evolution of agricultural exports from Latin American countries shows that this is a group of countries with a remarkable capacity to compete in the global market. During the period under study, the aggregate trade surplus of this group of countries increased from USD 4458.75 million to a total of USD 49,656.52 million. It is true, however, that there are also differences by product, with their export capacity for oilseeds standing out.

In this comparative exercise, the European trade balance represents the other side of the coin. Although, in absolute terms, throughout the series analysed, the European trade deficit quadrupled, the differences between some productions and others are more marked: the trade surplus that characterised dairy products and their derivatives contrasted with the deficit in oilseeds and cattle.

Finally, with regard to the limitations of the research, it should be noted that the results of this study must always be interpreted in relation to the type of production analysed. In other words, it is not (necessarily) a trend that can be generalised to all products, but rather, given the objective of the research, a series of products that are particularly protected by European agricultural policies and, therefore, particularly susceptible to the effects of a process of trade liberalisation have been taken as a reference. It is very likely that the results of the research would not be the same if the object of analysis were Mediterranean products.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The dissemination of this work was possible thanks to the funding granted by the Ministry of Economy, Science and Digital Agenda of the Junta de Extremadura and the European Fund for Regional Development (ERDF) of the European Union to the DESOSTE research group with reference GR21164.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aichele, Rahel, and Gabriel Felbermayr. 2015. Kyoto and Carbon Leakage: An Empirical Analysis of the Carbon Content of Bilateral Trade. Review of Economics and Statistics 97: 104–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, M. Ataman, and John C. Beghin, eds. 2005. Global Agricultural Trade and Developing Countries. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim, Celso. 2006. El G-20 en la Ronda Doha. Economía Exterior 37: 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, James E., and J. Peter Neary. 1994. Measuring the Trade Restrictiveness of Trade Policy. World Bank Economic Review 8: 151–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Anderson, James E., and J. Peter Neary. 1996. A New Approach to Evaluating Trade Policy. Review Economic Studies 64: 107–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, Gema, Vicente Pinilla, and Raúl Serrano. 2009. Europe and the international trade in agricultural and food products, 1870–2000. In Agriculture and Economic Development in Europe since 1870. Edited by Pedro Lains and Vicente Pinilla. London: Routledge, pp. 52–75. [Google Scholar]

- Baiardi, Donatella, Carluccio Bianchi, and Eleonora Lorenzini. 2015. Food competition in world markets: Some evidence from a panel data analysis of top exporting countries. Journal of Agricultural Economics 66: 358–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, Scott L., and Jeffrey H. Bergstrand. 2001. The growth of world trade: Tariffs, transport costs and income similarity. Journal of International Economics 53: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, Scott L., and Jeffrey H. Bergstrand. 2007. Do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade? Journal of International Economics 71: 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaens, Ida, and Evgeny Postnikov. 2017. Greening up: The Effects of Environmental Standards in EU and US Trade Agreements. Environmental Politics 26: 847–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonete, Rafael. 1994. Condicionamientos internos y externos de la PAC. Madrid: MAPA. [Google Scholar]

- Brandão, Antônio Salazar P., and Will J. Martin. 1993. Implications of agricultural trade liberalization for the developing countries. Agricultural Economics 8: 313–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, Clara, Jakob Schwab, Axel Berger, and Jean-Frédéric Morin. 2020. Do environmental provisions in trade agreements make exports from developing countries greener? World Development 129: 104899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano-Álvarez, Francisco J., Francisco M. Parejo-Moruno, J. Francisco Rangel-Preciado, and Esteban Cruz-Hidalgo. 2021. Regulation of Agricultural Trade and Its Implications in the Reform of the CAP. The Continental Products Case Study. Agriculture 11: 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, Eugenio. 2000. Los desequilibrios territoriales de la PAC. Cuadernos Geográficos 30: 143–63. [Google Scholar]

- Compés, Raúl, and José María García. 2005. Las reformas de la política agrícola común en la Unión Europea ampliada. Implicaciones económicas para España. Papeles de Economía Española 103: 230–44. [Google Scholar]

- Compés, Raúl, José María García Álvarez-Coque, and Amparo Baviera Puig. 2007. La reforma de la OCM de frutas y hortalizas. Evaluación de la propuesta de la Comisión. ICE 2910: 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Conde, Ángela Andrea Caviedes. 2014. La ordenación del comercio internacional de productos agropecuarios en la OMC. ICE 3056: 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, William, Mark Gehlhar, Thomas W. Hertel, Zhi Wang, and Wusheng Yu. 1998. Understanding the determinants of structural change in world food markets. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 80: 1051–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pablo, Jaime, Tomás García Azcárate, and Miguel Angel Giacinti Battistuzzi. 2016. Comercio internacional de almendras. Revista de Fruticultura 49: 190–219. [Google Scholar]

- De Pablo, Jaime, Tomás García Azcárate, Miguel Ángel Giacinti, and N. S. Giacinti. 2017. Competitividad internacional del aceite de oliva. Revista de Fruticultura 56: 142–69. [Google Scholar]

- Etxezarreta, Miren, Josefina Cruz, Mario García Morilla, and Lourdes Viladomiu Canela. 1995. La agricultura familiar, ante las nuevas políticas agrarias comunitarias. Serie Estudios; Madrid: MAPA. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 1991. Evolución y futuro de la Política Agraria Común. COM (91) 100. Suplemento 5/91 del Boletín de las Comunidades Europeas. Luxemburg: Oficina de Publicaciones Oficiales de las Comunidades Europeas. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 1997. Agenda 2000. Por una Unión más fuerte y más amplia. COM (97) 2000 Final. Suplemento 5/97 del Boletín de la UE. Luxemburg: Oficina de Publicaciones Oficiales. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2002. Revisión Intermedia de la Política Agrícola Común. Comunicación de la Comisión al Consejo y al Parlamento Europeo (COM (2002) 394). Luxemburg: Oficina de Publicaciones Oficiales. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2007. Preparándose para el chequeo de la reforma de la PAC. Comunicación al Parlamento Europeo y al Consejo, de 20 de noviembre 2007. (COM (2007) 722 Final). Luxemburg: Oficina de Publicaciones Oficiales. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Joaquín. 2006. Las reformas de la Política Agraria Común y la Ronda Doha. Economía Mundial 15: 155–77. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, Christopher. 2016. Tackling Climate Change through the Elimination of Trade Barriers for Low-Carbon Goods: Multilateral, Plurilateral and Regional Approaches. In Legal Aspects of Sustainable Development: Horizontal and Sectorial Policy Issues. Edited by Volker Mauerhofer. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 449–68. [Google Scholar]

- García, José María, and Alberto Valdés. 1997. Las tendencias recientes del comercio mundial de productos agrarios. Interdependencia entre flujos y políticas. Economía Agraria 181: 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- García, José María, Josep María Jordán, and Víctor David Martínez. 2008. El modelo europeo de agricultura y los acuerdos internacionales. Papeles de Economía Española, nº 117. Madrid: FUNCAS, pp. 227–42. [Google Scholar]

- García, José María. 1991. Las propuestas de liberalización del comercio mundial agropecuario. Una aproximación cualitativa. Revista de Estudios Agro-Sociales 155: 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- García, Tomás, J. De Pablo, and M. A. Giacinti. 2019. Competitividad internacional de la cereza. Revista de fruticultura 70: 108–25. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, Ian, and Dominique Van der Mensbrugghe. 1995. The Uruguay Round: An Assessment of Economywide and Agricultural Reforms. In The Uruguay Round and the Developing Economies. Edited by Will Martin and Alan Winters. Washington, DC: World Bank, pp. 25–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Torán, Primitivo. 1991. Políticas de ayuda y protección a la agricultura: Su tratamiento en el GATT. Revista de Estudios Agro-Sociales 155: 105–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway, Dale E., and Merlinda D. Ingco. 1995. Agricultural Liberalization in the Uruguay Round. In The Uruguay Round and the Developing Economies. Edited by Will Martin and Alan Winters. Washington, DC: World Bank, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Henders, Sabine, U. Martin Persson, and Thomas Kastner. 2015. Trading forests: Land-use change and carbon emissions embodied in production and exports of forest-risk commodities. Environmental Research Letters 10: 125012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyl, Katharine, Felix Ekardt, Paula Roos, Jessica Stubenrauch, and Beatrice Garske. 2021. Free Trade, Environment, Agriculture, and Plurilateral Treaties: The Example of Mercosur, CETA, and the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement. Sustainability 13: 3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingco, Merlinda D. 1997. Has Agricultural Trade Liberation Improved Welfare in the Least-Developed Countries? Yes. Policy Research Working Paper, nº 1748. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Jiborn, Magnus, Astrid Kander, Viktoras Kulionis, Hana Nielsen, and Daniel D. Moran. 2018. Decoupling or Delusion? Measuring Emissions Displacement in Foreign Trade. Global Environmental Change 49: 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josling, Tim. 1993. La PAC reformada y el mundo industrializado. Revista de Estudios Agro-sociales 165: 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Koning, Niek, and Per Pinstrup-Andersen, eds. 2007. Agricultural Trade Liberalization and the Least Developed Countries. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lamo de Espinosa, Jaime. 2008. La agricultura española en perspectiva. Papeles de Economía Española, nº 117. Madrid: FUNCAS, pp. 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mahía, Ramón, Rafael de Arce, and Gonzalo Escribano. 2005. La protección arancelaria al comercio agrícola mundial diez años después del acuerdo sobre agricultura de la Ronda Uruguay. ICE 820: 223–33. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A. Martin. 1991. La agricultura de Estados Unidos frente a la europea en la liberalización del comercio agrario. Revista de Estudios Agro-Sociales 155: 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Zarzoso, Inmaculada, and Walid Oueslati. 2018. Do Deep and Comprehensive Regional Trade Agreements Help in Reducing Air Pollution? International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 18: 743–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massot, Albert. 2000. La PAC, entre la Agenda 2000 y la Ronda del Milenio: ¿A la búsqueda de una política en defensa de la multifuncionalidad agraria? Revista de Estudios Agro-Sociales 188: 9–66. [Google Scholar]

- Massot, Albert. 2004. La reforma de la Política Agraria Común de junio de 2003. Resultados y retos para el futuro. ICE 2817: 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Millet, Montserrat. 2005. La PAC y las negociaciones comerciales internacionales. In Política agraria común: Balance y perspectivas. Directed by José Luis García Delgado and María José García Grande. nº 34. Barcelona: Colección de Estudios Económicos de La Caixa, pp. 154–81. [Google Scholar]

- Moyano, Eduardo. 1998. La política agraria en el proceso de integración europea. Revista de Fomento Social 53: 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parejo, Francisco M., and José Fco Rangel. 2016. El mercado mundial de aceituna de mesa (1990–2015). Regional and Sectorial Economic Studies 16: 127–46. [Google Scholar]

- Parejo-Moruno, Francisco M., José F. Rangel-Preciado, and Esteban Cruz-Hidalgo. 2020. La inserción de China en el mercado internacional del ajo: Un análisis descriptivo, 1960–2014. Economía agraria y recursos naturales 20: 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendrill, Florence, U. Martin Persson, Javier Godar, and Thomas Kastner. 2019. Deforestation displaced: Trade in forest-risk commodities and the prospects for a global forest transition. Environmental Research Letters 14: 055003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, José Ramón, and Luis Esteruelas. 1989. El GATT y el comercio internacional de productos agrarios. Revista de Estudios Agro-Sociales 148: 137–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rimmer, Maureen T., and Alan Powell. 1996. An implicitly directly additive demand system. Applied Economics 28: 1613–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, Fernando. 2006. Para entender la OMC y la Ronda Doha. Economía Exterior 37: 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, Mª Rosario. 2009. La liberalización del comercio agrícola internacional. ICE 2975: 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sadoulet, Elisabeth, and Alain De Janvry. 1992. Agricultural trade liberalization for the low-income countries: A general equilibrium-multimarket approach. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 74: 268–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Juan, Carlos. 1991. La Ronda Uruguay del GATT. La dimensión internacional. Revista de Estudios Agro-Sociales 155: 193–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sancho, Roberto. 1991. El GATT y la reforma estructural de la CEE. Revista de Estudios Agro-Sociales 155: 131–43. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, Raúl, and Vicente Pinilla. 2010. Causes of world trade growth in agricultural and food products, 1951–2000: A demand function approach. Applied Economics 42: 3503–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, Raúl, and Vicente Pinilla. 2014. New directions of trade for the agri-food industry: A disaggregated approach for different income countries, 1963–2000. Latin American Economic Review 23: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tang, Chang, Muhammad Irfan, Asif Razzaq, and Vishal Dagar. 2022. Natural resources and financial development: Role of business regulations in testing the resource-curse hypothesis in ASEAN countries. Resources Policy 76: 102612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangermann, Stefan. 1987. La influencia de terceros países sobre la política agrícola común. Revista de Estudios Agro-Sociales 140: 109–31. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Zhenci, Yingjie Li, Sophia N. Chau, Thomas Dietz, Canbing Li, Luwen Wan, Jindong Zhang, Liwei Zhang, Yunkai Li, Min Gon Chung, and et al. 2020. Impacts of international trade on global sustainable development. Nature Sustainability 3: 964–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).