1. Introduction

The attainment of long-run economic growth remains a fundamental objective of every economy, and a critical vehicle of growth that many countries rely on to achieve this objective is foreign direct investment (FDI). This is due to the unique and essential role of FDI in driving industrialisation and boosting the manufacturing sector, which were identified as principal drivers of growth and development (

Akinlo 2004). Furthermore, globalisation has dramatically increased capital flexibility and mobility across the globe, with FDI regarded mainly as the safest and most advantageous form of capital flow. Empirically, studies identified the crucial role that FDI plays in boosting productivity and general macroeconomic performance through the promotion of technology transfer, managerial talent and financial capital, which would otherwise be unavailable or provided only at a much greater cost (

Akinlo 2003;

Khan 2007;

Ugwuegbe et al. 2014). This role of FDI could engender a “spill-over” effect on different aspects of the economy that are not direct beneficiaries of FDI, with a concomitant positive impact on the overall economy (

Rappaport 2000).

This corroborates the position of the neoclassical and endogenous growth theorists. They stressed the crucial role of innovation, technology transfer, knowledge spill-over, and managerial and technical skills that arise from capital flows in the economic growth process (

Grossman and Helpman 1991;

Mankiw et al. 1992). Since the early 1990s, when communism and the central planning system crumbled, the four Central European states, known as the Visegrád Four (V4), which comprise the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, have advanced several strategies aimed at enhancing FDI inflow as a way of driving sustained economic growth (

Chen et al. 2018;

Chidlow et al. 2009;

Qi and Li 2017). According to

UNCTAD (

2007), FDI inflow refers to the capital or finance provided for an enterprise in a host country by a foreign direct investor either directly or through other related enterprises.

According to

White and Fan (

2006), country risk can be sub-divided into economic, financial, cultural and political risks, while

Moosa (

2002) refers to it as exposure to a financial loss in international business activities that is brought on by circumstances in a certain nation that are, at least in part, under the government’s authority. Intuitively, country risk should rate high among the most important determinants of FDI considering that how external bodies relate to a country is highly influenced by its economic, financial and political environments. Moreover, investors are generally averse to systematic risks that are mainly external and out of their control. Since all the components of country risk are systematic, foreign investors are bound to be wary of them, which could ultimately influence FDI flows.

Root (

1987) opined that any foreign investment project must be assessed from the perspectives of its economic, social, political and cultural environments. Therefore, it is not surprising that multinational companies (MNCs) are often more favourably disposed to countries where they may encounter low risk and generate high returns on their investment in making their offshore investment decisions.

The focus on the V4 is essential because of certain peculiarities that pertain to this group of countries. First, following their emergence from communism, the V4 were deemed unattractive locations by foreign investors (

Gauselmann et al. 2011) and often labelled “catching-up” countries (

Tendera-Właszczuk and Szymański 2015). This prompted them to devise various strategies to attract FDI, after which they became prime targets of FDI, especially after exiting the transition recession and acceding to the European Union (EU). Some of the policy measures put in place to drive FDI inflow included lessening the obstacles to FDI (which, according to

Koyama and Golub (

2006), culminated in maintaining a very low regulatory restrictiveness index relative to the average index in the OECD countries) and developing and deepening financial markets (

Vojtovic 2019). As depicted in

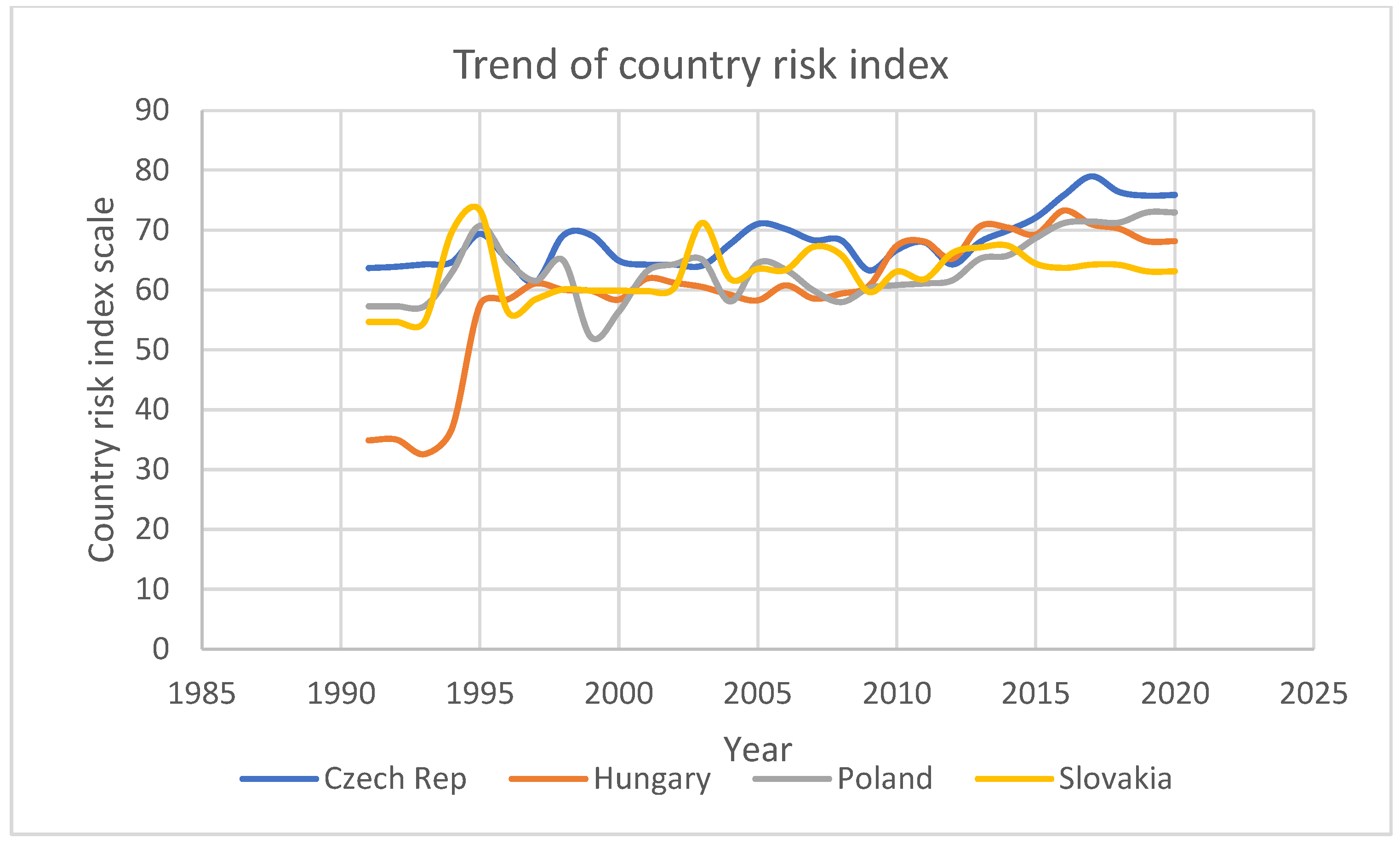

Figure 1, the country risk scores of the four countries have continually fluctuated since 1995 and have never reached the 80/100 mark (indicating a very low-risk status). Thus, there is a need to investigate how these country risk attributes influence FDI inflow.

The 2008–2009 financial crisis, which hit the V4 economies very hard because of their massive exposure to international business cycles, resulted in increased government intervention and measures that could lead to a decline in the share of foreign investment in specific sectors (

Hunya 2017;

Sallai and Schnyder 2018;

Sass 2017). More likely than not, this mixed bag of policy interventions has implications for various components of the country risks of the V4. Yet, to the best of our knowledge, no study has addressed the question of the growth impact of country risk on FDI inflows in the context of the V4 despite the impact that the policy measures and reversals could have on the country risk ratings and the extent to which country risk could impact the investment decision of foreign investors in an economy.

Second, the V4 have a lot of social and economic interaction/financial integration and share common historical roots and cultural traditions, having emerged from communism, which held sway in Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs) until 1989. Consequently, the process of FDI flows to the four countries has several shared characteristics: the first years of FDI inflows witnessed a predominance of brownfield investments, the following years saw more significant emphasis on greenfield investment, the period after the EU accession (especially, 2004–2007) experienced increased and dynamic FDI inflows, a disproportionately large percentage of FDI inflow to the V4 came from the EU and FDI inflow to the V4 has witnessed noticeable structural changes towards the services sector over the years (

Ambroziak 2013;

Zielińska-Głębocka 2013).

Despite these common features and consequent interdependence between the V4 countries, all existing panel studies on the determinants of FDI in the V4 assumed cross-sectional independence in the disturbances of their panel models, thereby failing to account for the likely cross-sectional dependence (CD) between the countries.

Eberhardt and Teal (

2010) and

Pesaran (

2006) intensely faulted this assumption on the grounds that it could result in biased estimates, and consequently, inappropriate policy proposals. To this end, they propounded panel regressions with robust standard errors that can account for CD between the countries. The need to account for CD is key because a shock to an economy could be transmitted to other economies that are macroeconomically interdependent (

Olaoye and Aderajo 2020;

Olaoye et al. 2020). This is because common features and interdependence between economies can engender CD due to globalisation (

De Hoyos and Sarafidis 2006). As shown in

Figure 1, beyond 1995, the trend of country risk in all four Visegrád countries appeared to move in the same direction and around similar scores for each year. This reflects a tendency for CD between the four countries. Therefore, by using the

xtdcce2 programs provided by

Ditzen (

2018), which are designed to produce estimates for the dynamic common-correlated effects (DCCE) estimator proposed by

Chudik and Pesaran (

2015), this work departed from earlier research efforts by accounting for CD and heterogeneous slopes in the panel of the V4.

Third, while the preponderance of findings from studies on the determinants of FDI in the V4 has identified several variables that portray the size/growth and the cost competitiveness of the economies, few other studies stressed that other factors such as corruption, national risk, reforms in the banking sector, economic reforms, political risk and liberalisation influence the inflow of FDI in the V4 and the CEECs in general (

Avioutskii and Tensaout 2016;

Bevan and Estrin 2000;

Brada et al. 2006;

Cieślik 2020;

Su et al. 2018). Each of these factors is either a component of country risk or is somewhat connected to it. Meanwhile, it is noteworthy that none of the previous studies on the impact of country risk on FDI inflows (

Hammache and Chebini 2017;

Khan and Akbar 2013;

Nassour et al. 2020;

Rodríguez 2016;

Salem and Younis 2021;

Topal and Gul 2016) focussed on the V4. Thus, the V4 deserves a separate study to determine the impact of country risk and each of its components on the FDI inflows into their economies. This is crucial, as it tends to help the countries set a realistic target of country risk rating, which would potentially increase the V4’s appeal as a preferred FDI location.

The remaining segments of this paper focus on the following:

Section 2 contains a review of both the theoretical and empirical literature.

Section 3 discusses the methodology, while

Section 4 discusses the results of the tests and regressions.

Section 5 concludes the study.

5. Panel Regression Results

Table 6 presents the results of the DCCE regression conducted to determine long-run elasticity relationships. The table contains four models, with each displaying the estimates of an equation with each of the four country risk indexes as the country risk variable. Specifically, model 1, model 2, model 3 and model 4 represent the results of regressions for equations with the composite country risk index, economic risk index, financial risk index and political risk index, respectively, as the country risk variable. For model 1, the results from the DCCE regression indicated that the composite country risk index was positive and strongly significant at the 1% level. This indicated that country risk had a strong negative effect on FDI inflows into the Visegrád countries. Specifically, the result suggested that a 1% increase in composite country risk index score (which suggests a reduction in the overall country risk) led to an increase in FDI inflow by 0.835%, and vice versa.

This finding suggested that, when holding other factors constant, reducing country risk gave impetus to the inflow of FDI into the V4. The result could also suggest that FDI inflows into the V4 were influenced by the relationship between the levels of country risk in the FDI origin countries and those of the V4. It was argued by

Yasuda and Kotabe (

2021) that multinational companies set origin countries’ level of risk as the reference point and that they adjudge FDI host countries as investment opportunities (or threats) if their level of risk is lower than (or higher than) that of the origin country. Thus, this research output implied that to improve FDI inflows into the V4, the countries should work towards attaining higher country risk index scores by gaining improvement in the ICRG variables that indicate a reduction in country risk. The result is congruent with the position of extant studies on the FDI–country risk nexus (

Almahmoud 2014;

Bevan and Estrin 2000;

Brada et al. 2006;

Hammoudeh et al. 2011;

Salehnia et al. 2019;

Sissani and Belkacem 2014), which consider country risk as an important influencer of FDI inflows.

For model 2, the DCCE regression results showed that the economic risk index had a positive and strongly significant coefficient at the 1% level. This indicated that the economic risk negatively affected the FDI inflows. In particular, the result suggested that a 1% increase in the economic risk index score (which implies a decrease in economic risk) enhanced the FDI inflows by 0.919%, and vice versa. This result corroborated previous findings by

Salehnia et al. (

2019) and

Salem and Younis (

2021), which showed that economic risk has a powerful effect on FDI inflows. The result further stressed the importance of maintaining high GDP levels, as well as optimal levels of the inflation rate, budget balance and current account for investment inflows to be enhanced in the V4. Turning to model 3, the coefficient of financial risk was positive and significant at the 10% level. This suggested that although financial risk negatively affected the FDI inflows, the effect was somewhat weak. As shown in

Table 1, the average financial risk rating score for the V4 over the study period was 15.25/50, while the lowest score was −26.49/50. This below-par performance of the V4 regarding the financial risk rating did not inhibit the growth of the FDI inflows over the years examined. Therefore, compared with the economic and political risk components, the financial risk appeared to be less important in influencing the FDI inflows into the Visegrád countries.

The result for political risk was captured by model 4, and the DCCE regression revealed that it exerted a negative impact on the FDI inflows, as the coefficient of the political risk index was positive and significant at the 5% level. This implied that improvement in the political risk index score (which indicates a decline in political risk) engendered rising FDI inflows. Specifically, holding other variables constant, a 1% increase in the political risk index score (or a 1% decrease in political risk) accounted for a 0.307% increase in the FDI inflows into the V4. This research outcome was in line with a preponderance of extant studies (

Avioutskii and Tensaout 2016;

Cieślik and Goczek 2018;

Hayakawa et al. 2013;

Rafat and Farahani 2019;

Salehnia et al. 2019;

Bouyahiaoui and Hammache 2017;

Su et al. 2018), which established political risk as a major influencer of the FDI inflows. As indicated in

Table 1, the average political risk index score for the V4 over the study period was 77.63, while the lowest score was 70.58. Both scores fell within the ICRG score classification of low risk, which implied that all the countries were doing very well in this regard. Therefore, this finding indicated the need for the Visegrád countries to continue to maintain their high political risk rating, which was found to be important for attracting FDI.

For the covariates in all four models, the DCCE results demonstrated that real GDP, which represents the market size, was a strong determinant of the FDI inflows, as the coefficient of GDP was positive and strongly significant across the four models. The magnitudes of real GDP in the models suggested that it exerted a strong positive elastic impact on FDI in the V4. This research outcome is consistent with several studies that identified market size as a strong driver of FDI (

Demirhan and Masca 2008;

Khan and Akbar 2013;

Meyer and Habanabakize 2018;

Salem and Younis 2021;

Wach and Wojciechowski 2016). The coefficient of natural resources was insignificant across the four models. This result suggested that natural resource availability did not influence the inflow of FDI into the V4. For infrastructure, the coefficient was positive and significant throughout. This implied that improvement in the level of infrastructure was associated with an increase in FDI inflow. This result is consistent with the findings of

Demirhan and Masca (

2008) for 38 developing countries and

Gorbunova et al. (

2012) for 26 transition countries, which included the V4, who stated that infrastructure in the host country positively influences FDI inflows. The DCCE results further showed that the coefficient of trade openness was positive and significant in all four models, which suggested that increased openness to international trade enhanced the FDI inflows into the V4. This result supports findings by

Anyanwu (

2012) and

Liargovas and Skandalis (

2012), who concluded that trade openness is positively linked to FDI.

The long-run elasticity results of the V4 panel were already presented and discussed. However, in order to facilitate more robust policy formulation, there is a need to also explore the linkage between the FDI inflow, country risk, real GDP, natural resources, infrastructure and trade openness on a country-wise basis. To this end, FMOLS regressions were conducted for each of the Visegrád countries, and the results are presented in

Table 7. The table contains four compartments, with each consisting of an equation with each of the country risk variables. As such, for each of the four countries, models 1–4 represent the results of regressions for the composite country risk, economic risk, financial risk and political risk, respectively, as the country risk variable. The model 1 results revealed that the composite country risk had a negative and significant impact on the FDI inflows into the Visegrád countries. Specifically, a 1% increase in the country risk index score (which implies a decline in country risk) led to an increase in the FDI inflows in the case of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia by 0.25%, 0.17%, 0.77% and 0.52%, respectively, though the impact was rather weak with a 10% significance in the case of Hungary. Generally, a healthier country risk rating raises the confidence of overseas investors regarding the safety of their investment in the host country, which, in turn, enhances their tendency to bring in their investment. These results are in line with the findings of

Almahmoud (

2014) and

Sissani and Belkacem (

2014) for Saudi Arabia and Algeria, respectively.

Concerning the coefficient of the economic risk index, as shown in model 2, it had a significantly positive coefficient, which suggested that the economic risk negatively affected the FDI inflows into the Visegrád countries. In particular, a 1% increase in the economic risk index score (which implies a reduction in economic risk) enhanced the FDI inflows by 0.62%, 0.46%, 0.37% and 0.59% into the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, respectively. The strong significance and high coefficients of economic risk in all the countries suggested the cruciality of economic risk in driving the FDI inflows into the V4. Therefore, this research outcome indicated the need for both monetary and fiscal authorities in the Visegrád countries to put appropriate policies in place towards maintaining optimal levels of the inflation rate, GDP growth, budget and current account.

The estimates of financial risk that are displayed for model 3 show that financial risk had mixed impacts on the FDI inflows across the Visegrád economies. It had a negative and strongly significant impact on the FDI inflows into Hungary. According to the estimates, a 1% increase in the financial risk index score (which suggests a reduction in financial risk) led to an increase in the FDI inflows by 0.31% into Hungary. However, the impacts of financial risk on the FDI inflows into the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia were also negative but weak, as the coefficients of the financial risk index score were only significant at the 10% level for these three countries. This mixed country-wise result of the financial risk variable was congruent with the overall panel finding of the weak impact of financial risk on the FDI inflows into the V4. In the case of Hungary with a strong negative impact of financial risk on the FDI inflows, it suggested a consequence of injudicious fiscal policies of the country’s socialist administration in the 2000s, which led to a budget deficit that far exceeded the EU criteria

1. This led to increased foreign debt at levels far above their V4 counterparts over the years (see

Appendix A), which increased the economy’s financial risk and in turn led to fluctuations in the FDI inflows. Therefore, the case of Hungary suggested that for individual V4 countries, financial risk can be a key influencer of FDI inflow, depending on how it is managed. Regarding the coefficient of the political risk index displayed for model 4, it was positive and strongly significant across the four countries. This implied that political risk had a negative effect on the FDI inflow. Particularly, a 1% increase in the political risk index score (which suggests a decrease in political risk) enhanced the FDI inflows by 0.26%, 0.54%, 0.17% and 0.48% into the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, respectively.

Finally, the estimates of the covariates in all four models for the four countries were generally consistent with those of the overall panel discussed earlier with only a few exceptions. The trio of market size, infrastructure and trade openness bore positive and strongly significant coefficients throughout. This implied that the three variables positively influenced the FDI inflows into each of the Visegrád countries. However, while natural resources were found to be insignificant for the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia, it was weakly significant in the case of Poland in all the models, which implied that natural resource availability somewhat influenced the inflows of FDI to Poland.

6. Conclusions

Investigation of FDI determinants has grown significantly over the years due to the vital role that FDI plays in the economic growth process across countries. While several variables were identified as determinants of FDI in different regions of the world, vigorous debate continues as research results have remained predominantly mixed and inconclusive. Meanwhile, studies that considered the peculiarities and heterogeneities of the V4 group in the investigation of country risk as a determinant of FDI inflows are scarce. Hence, this study filled the literature gap by examining whether country risk influenced foreign investors’ decision to invest in the V4. To achieve this objective, this study employed the DCCE estimator, which accounts for CD, structural breaks and heterogenous slopes in panel data estimation. A survey of literature on the subject showed that no previous study accounted for CD despite the increased predominance of globalisation interdependence between countries. To ensure the robustness of results and explore how the coefficients varied across the countries, country-wise FMOLS regressions were also conducted on annual data for the V4 over the period 1991–2020.

The empirical results showed that country risk mattered for the FDI inflows, as it negatively impacted the FDI inflows. It was also found that economic and political risks were essential determinants of the FDI inflows, as both had negative effects on the FDI. However, it was found that changes in financial risk had weak and mixed impacts on the FDI inflows in the overall panel and country-wise regressions, respectively. The research outcome also demonstrated that market size, infrastructure and trade openness positively influenced the FDI, while natural resource availability had no impact and a mixed impact in the overall panel and country-wise regressions, respectively.

Based on these research outcomes, there is a need for the appropriate macroeconomic and government authorities in the V4 to enhance the market potentials of their economies by improving and upholding the corporate and macroeconomic structures in order to enhance their country risk attributes. Furthermore, appropriate policy should be formulated by the governments in these countries towards increasing the market potential, quality of infrastructure and optimal environment for FDI-inflow-enabling trade.