Abstract

As the importance of Chinese financial schemes in maritime business increases, and many issues on the ownership of the assets under the current Law remain obscured for international investors, this work argues that a streamlining to international practice is required; therefore, the ownership of the trust property under the shipping fund in China should be transferred to the trustee from the client. The trustee shall possess, employ, benefit, and dispose the trust property in his/her own name, which links up with China’s current property legislation, ship registration, and ship arrest regulations. The trust property under the shipping fund in China is independent of the fixed property or other management property of the trustee, the beneficiary, and the custodian. This gives full play to functional advantages of the trust system of the shipping fund, contributes to the expansion of financing channels in the shipping industry in China, guarantees the specialization and flexibility of shipping investment activities and the diversity of the investment subject, promotes development of China’s policies about the shipping industry and financial innovation, and boosts the realization of “The Strategy of National Revitalization Based on Marine Industry Development” and “The Belt and Road Initiatives” and construction of Shanghai International Shipping Center and International Finance Center.

Keywords:

shipping trust fund; ship finance; one-belt-one-road; China; alternative finance; green finance JEL Classification:

N25; L91; L92; L98

1. Introduction

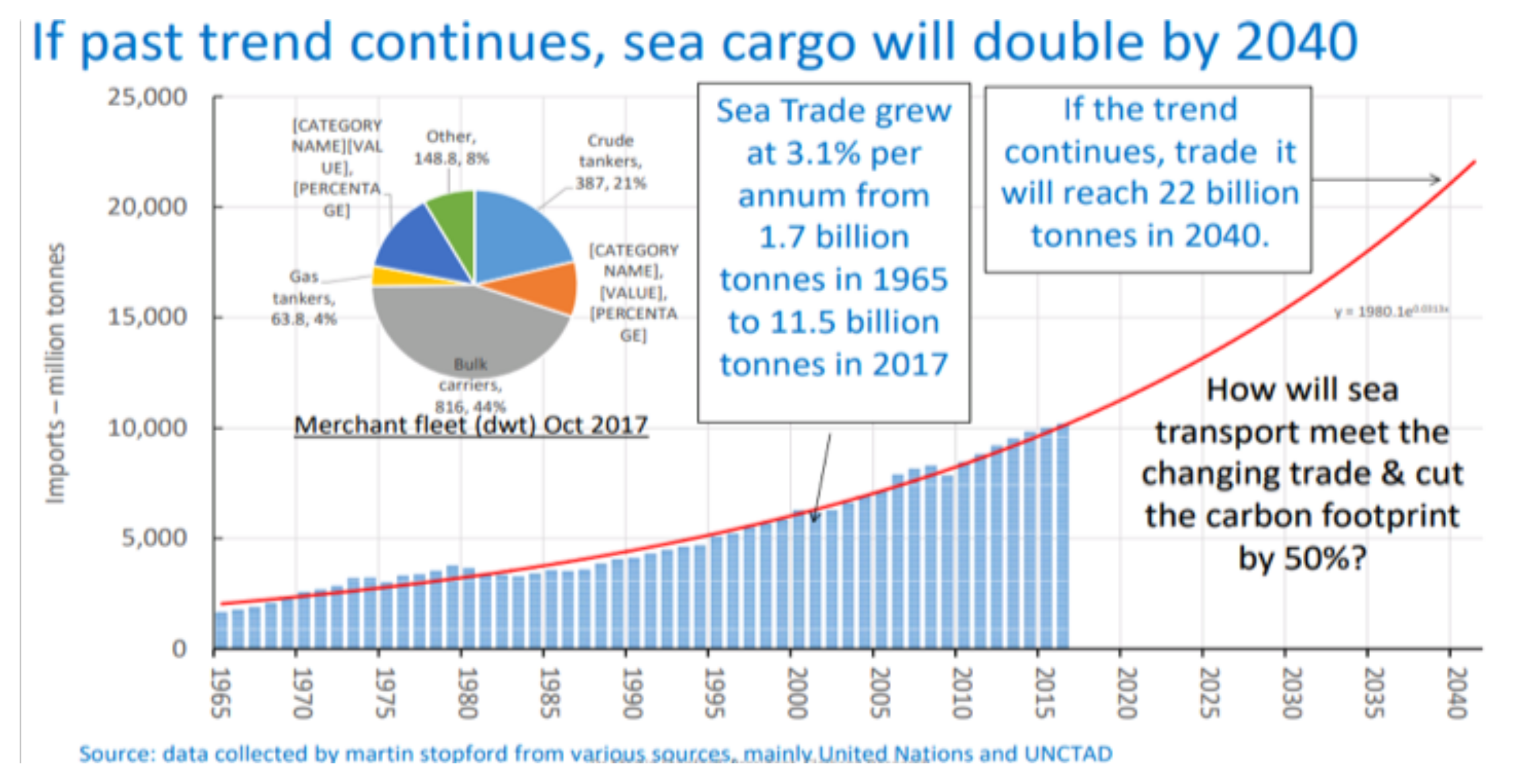

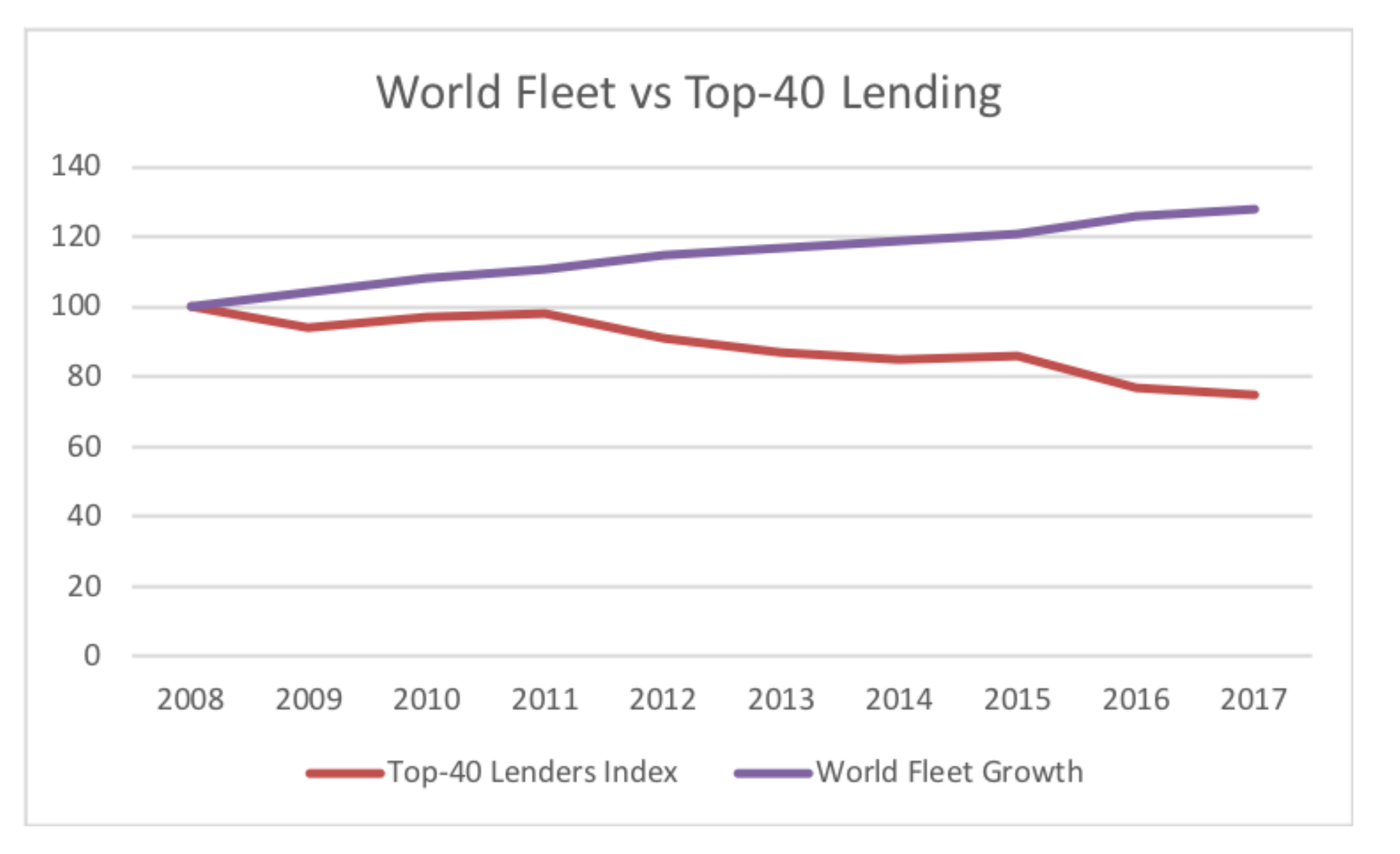

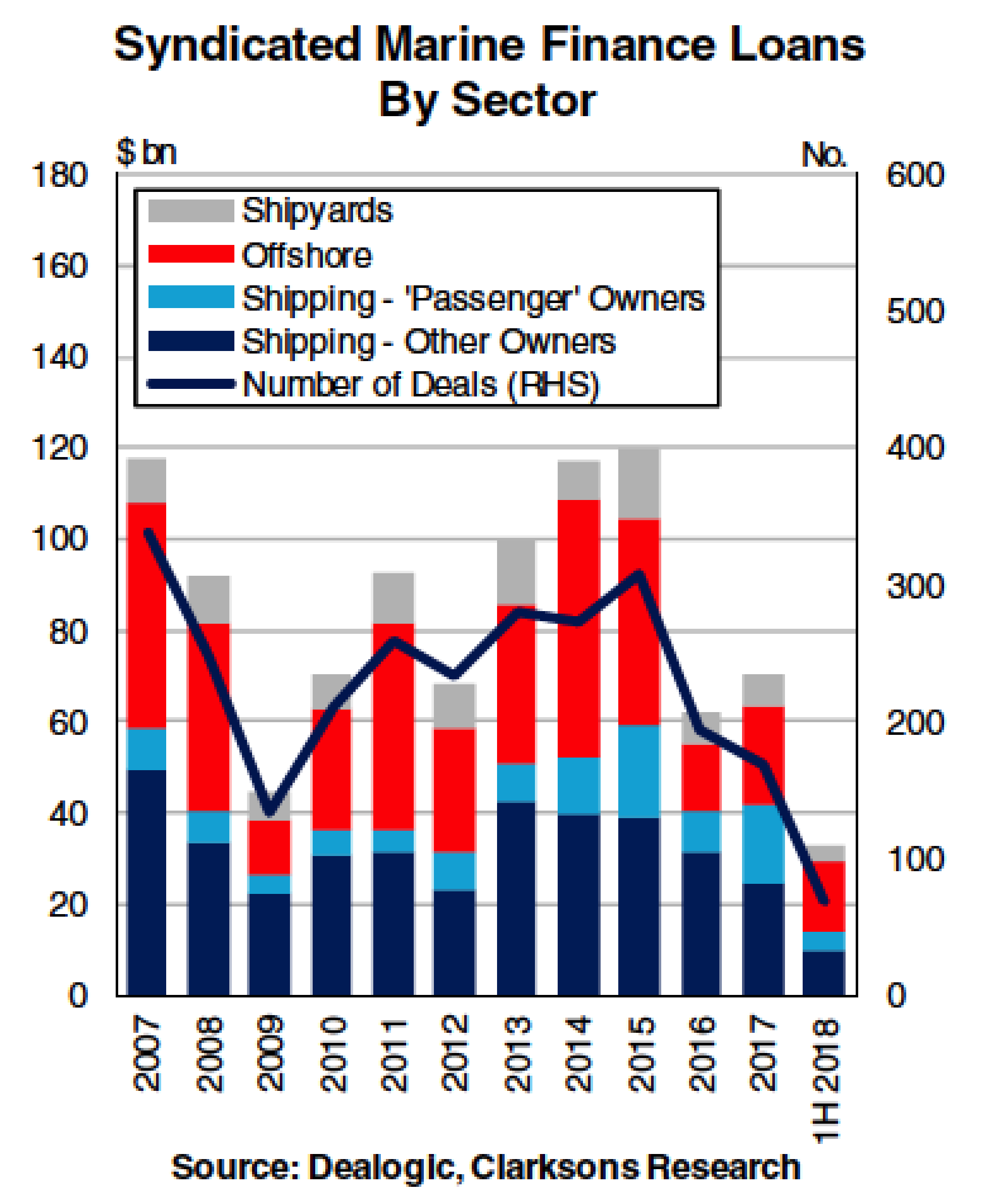

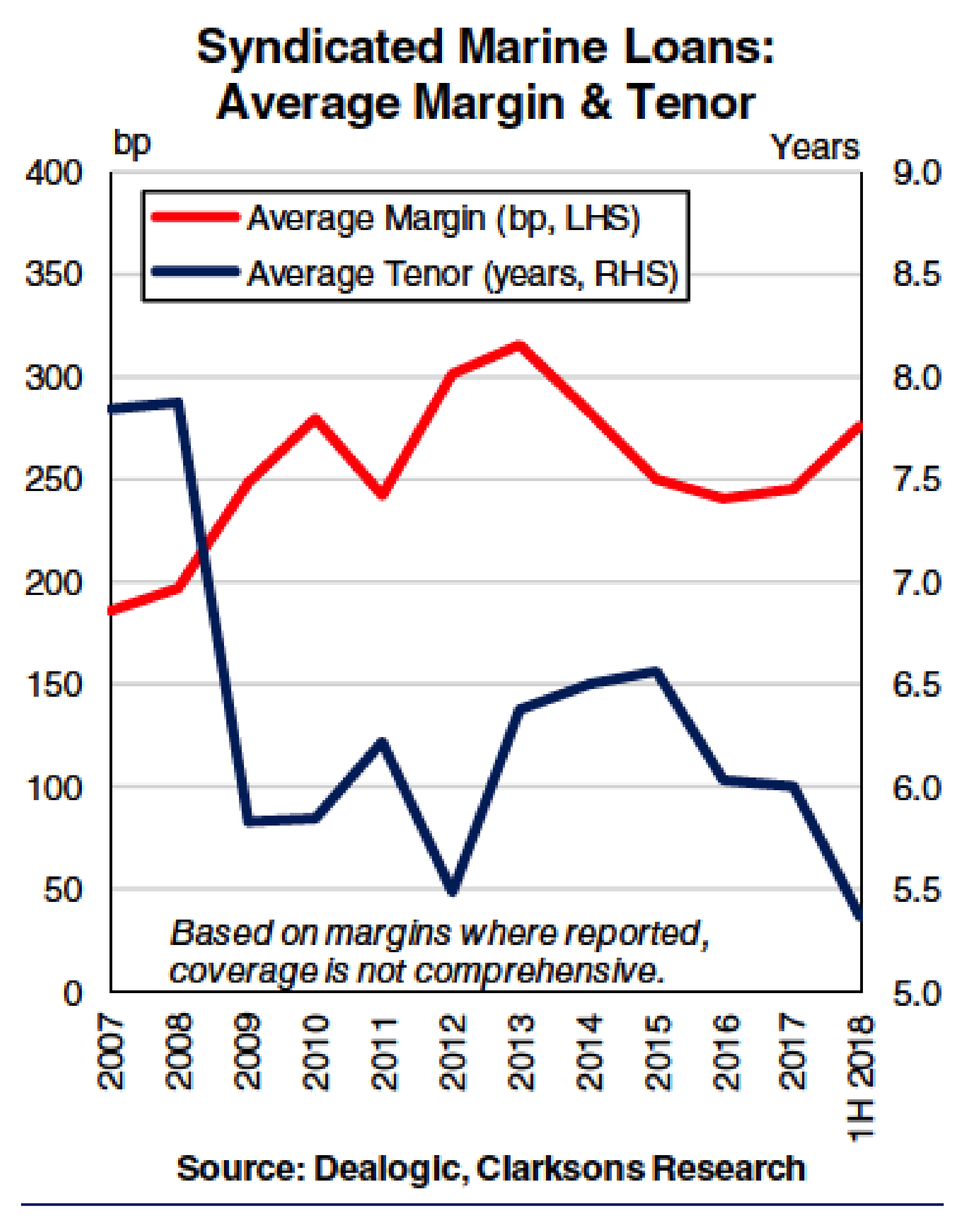

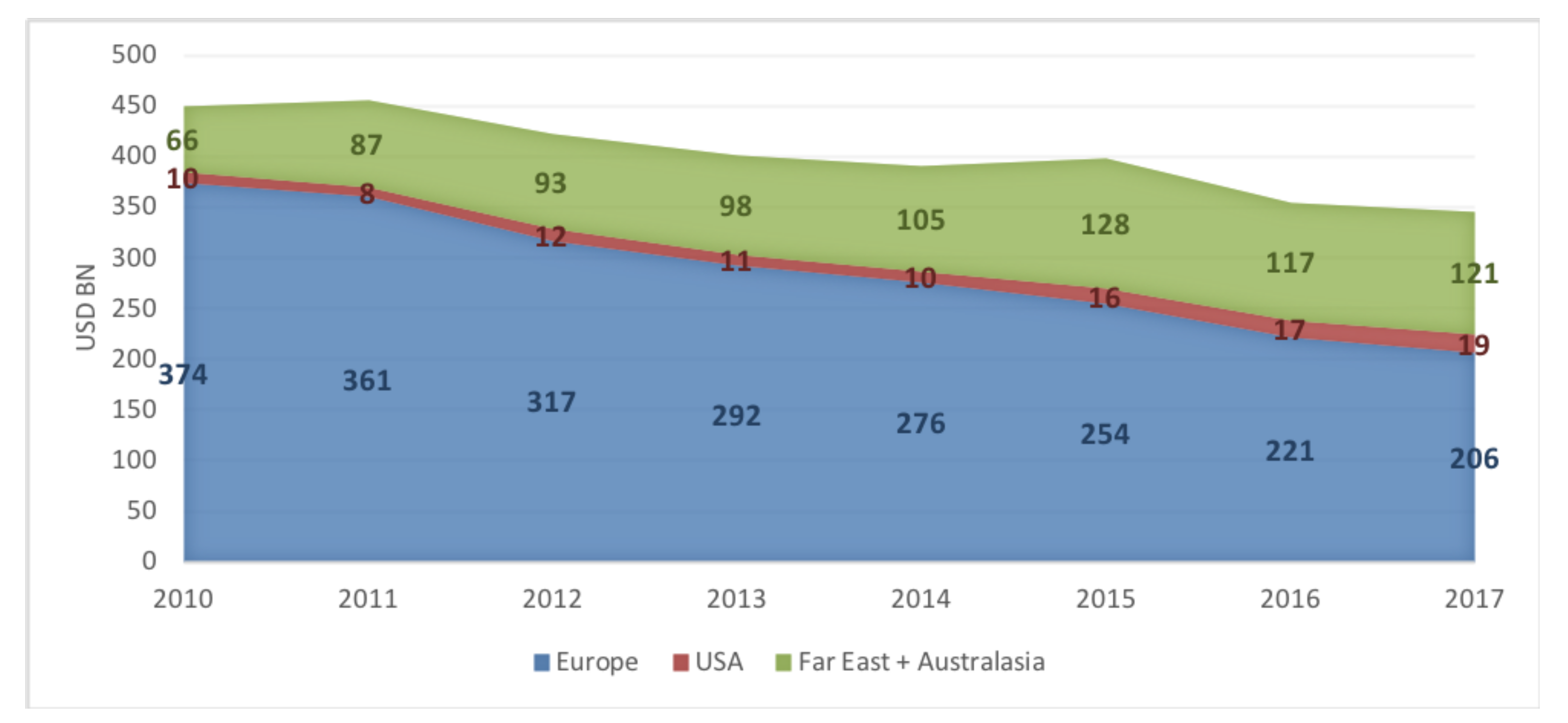

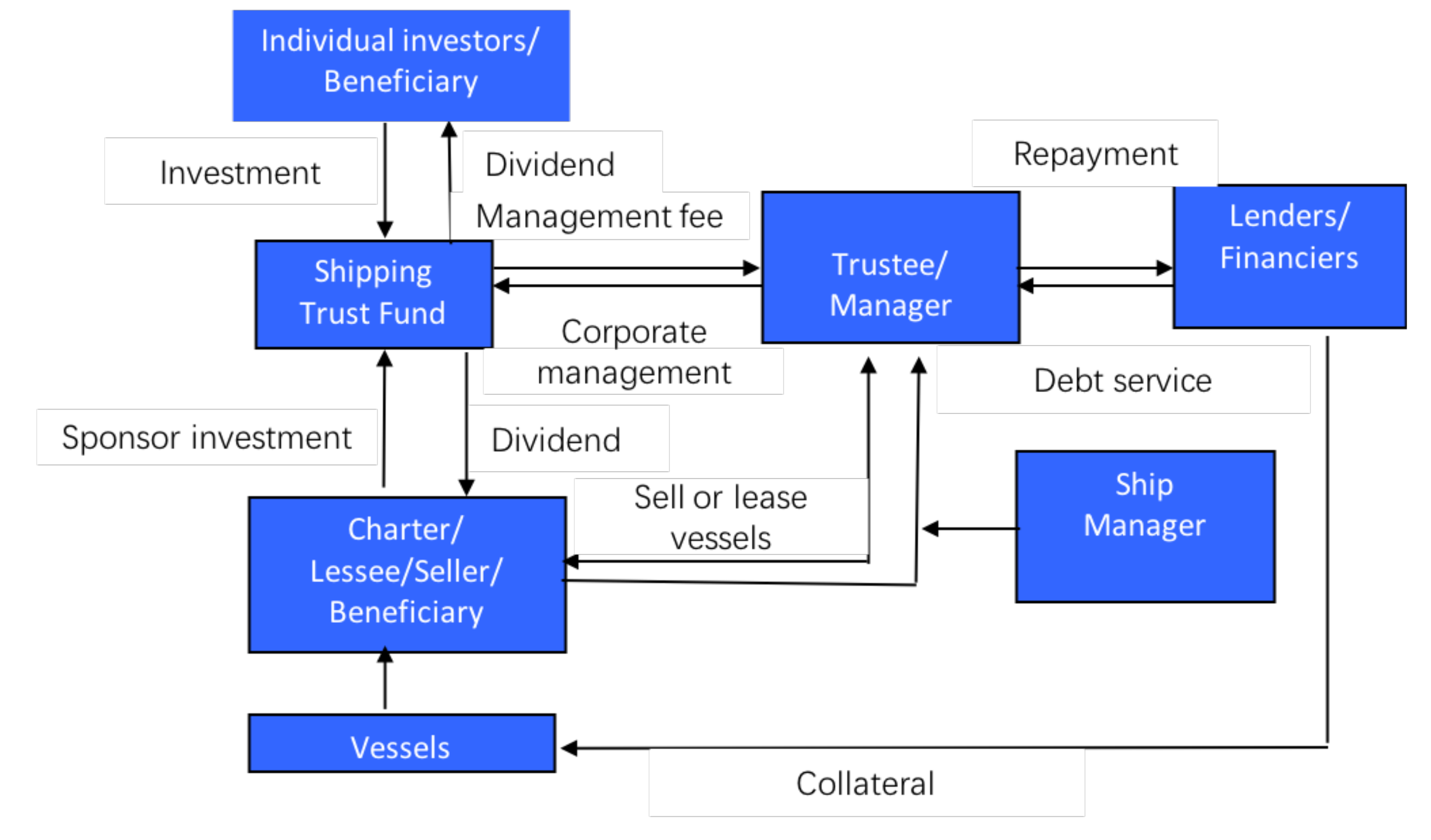

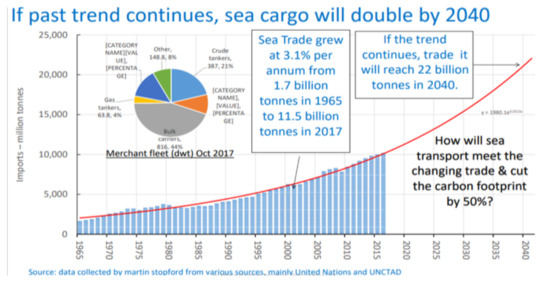

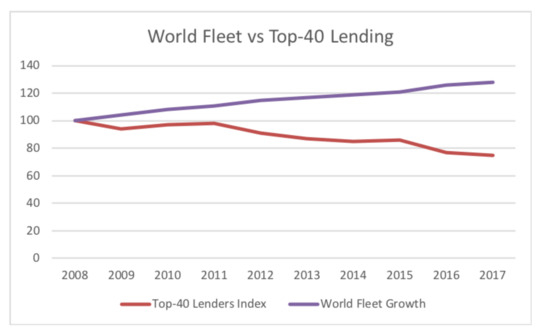

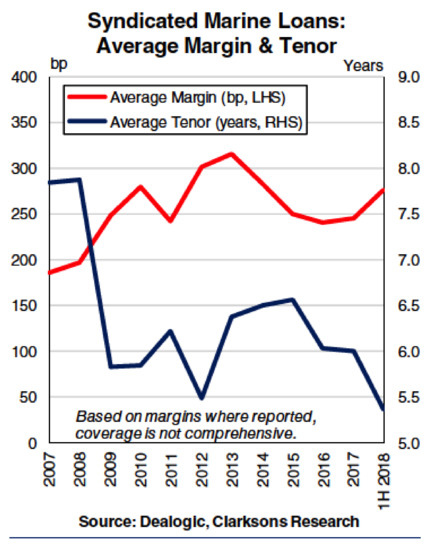

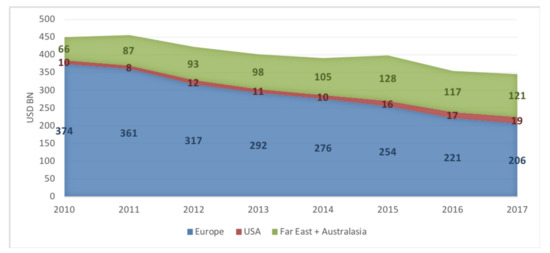

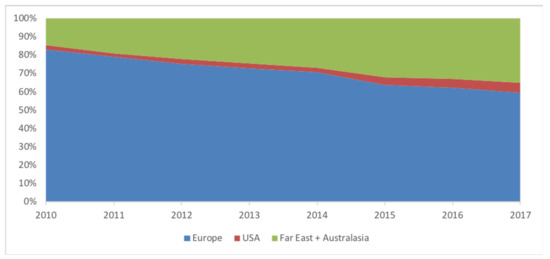

International seaborne trade is still growing (see Figure 1) and further development is also expected (UNCTAD 2019). However, in the aftermath of financial crisis of 2008, ship financing markets have been substantially affected; despite the growth of the fleet, ship finance banks do not support further international shipping (see Figure 2). In this regard, ship loans became scarce (Figure 3), more expensive and with shorter tenure (Figure 4). Due to national interests in the shipbuilding sector, this gap of in the financing is at large covered by Asian banks (see Figure 5 and Figure 6). European banks retreated; a reported sum of USD168bn reflects this decision. On the other hand, Asian banks increased their exposure by USD55bn. The original 85–15% split between European and non-European banks of 2010 is trimmed to 70–30% (Clarksons Research 2019).

Figure 1.

Evolution of SeaborneTrade.

Figure 2.

Indexed Bank Lending and Fleet Growth.

Figure 3.

Shipping Loans per Sector, Source: Clarksons.

Figure 4.

Pricing of Shipping Loans, Source: Clarksons.

Figure 5.

Breakdown per Region 1.

Figure 6.

Breakdown per Region 2.

The shipping industry plays a very important role in the development of global economy and trade and especially for China, due to the need of importing raw material and of exporting manufactured goods (Liu et al. 2008). China, the second largest economic entity and a major trading country in the world, has become a major country in the shipping industry and in terms of the manufacturing of ships and marine engineering equipment. But it is not yet a powerful shipping country and there is a big gap between China and advanced countries in terms of the shipping technology level and comprehensive strengths (Zhang 2014). Standing at a new starting point, China wants to become a powerful shipping country and build Shanghai into an international shipping center to realize the strategy of maritime silk road. It has to be noted, the one-belt-one-road initiative is not only a pivotal strategic decision of China but an investment magnifier, a leverage for local growth of trade and development of infrastructure. This initiative, and its various aspects, are widely discussed in the literature (see e.g., Ferdinand 2016; Haralambides 2017; Schinas and von Westarp 2017; Sheu and Kundu 2017; Zeng 2017). To this end, it must first realize aggregation and configuration of shipping resources such as ship and shipping companies, shipping capitals, shipping services, high-end shipping talents, etc., because the shipping industry is a capital-intensive industry and its development depends on the support of financial capital (Yang 2003). Considering the retreat of European banks that fuelled shipbuilding activity, China has to offer new, innovative financial structures, that serve both wider policy goals and business objectives of private interests.

In line with international practice, where export credit schemes are supporting national policies and goals, there is a need also to finance the greening of maritime operations; in this regard China has an interest to finance also ‘green’ ships, as ships of higher value yield also higher return to the financiers and the builders (Schinas 2018; Schinas et al. 2018). A Chinese shipping trust fund, an innovative financial instrument emerging in recent years, has been applied to the shipping field by flexibly integrating the fund system and the trust system and depending on the support of governmental shipping policies and the capital market. Breaking through the limitations of the traditional shipping financing mode and barriers of the traditional shipping fund in the two links—“entrance” and “exit”—at the time of capital raising, this financing channel is being recognized by more and more parties and is becoming a relatively mature mode of shipping financing. This promotes the expansion of the shipping financing channel, promotes the reform and development of China’s shipping and finance industries, enhances industrial upgrading of the shipping industry and integration of the shipping and finance industry chains, advances national industrial policies, safeguards national marine rights and interests, and plays an important and active role in realization of “The Belt and Road Initiatives” strategy, the free-trade zone strategy, and the construction of the Shanghai International Shipping Center and International Finance Center.

However, there is no legislation specific to the shipping financing field in China, much less for specific regulations on the shipping trust fund. The shipping trust fund can only be regulated with currently applicable general financing laws and regulations on trusts and funds. These laws do not consider the particularity of shipping assets, as ships are financial and technical assets that operate in an international and intra-jurisdictional framework. Specifically, China’s Trust Law, Securities Law, and other related laws and regulations have laid a legal foundation for the establishment and application of the shipping trust fund, but the lack of particular laws and regulations for shipping impedes the growth of a relevant shipping fund market. In addition, a series of law problems badly need to be addressed, such as the relations and the qualification of a ship as an object under the civic Law in the framework of a shipping trust fund.

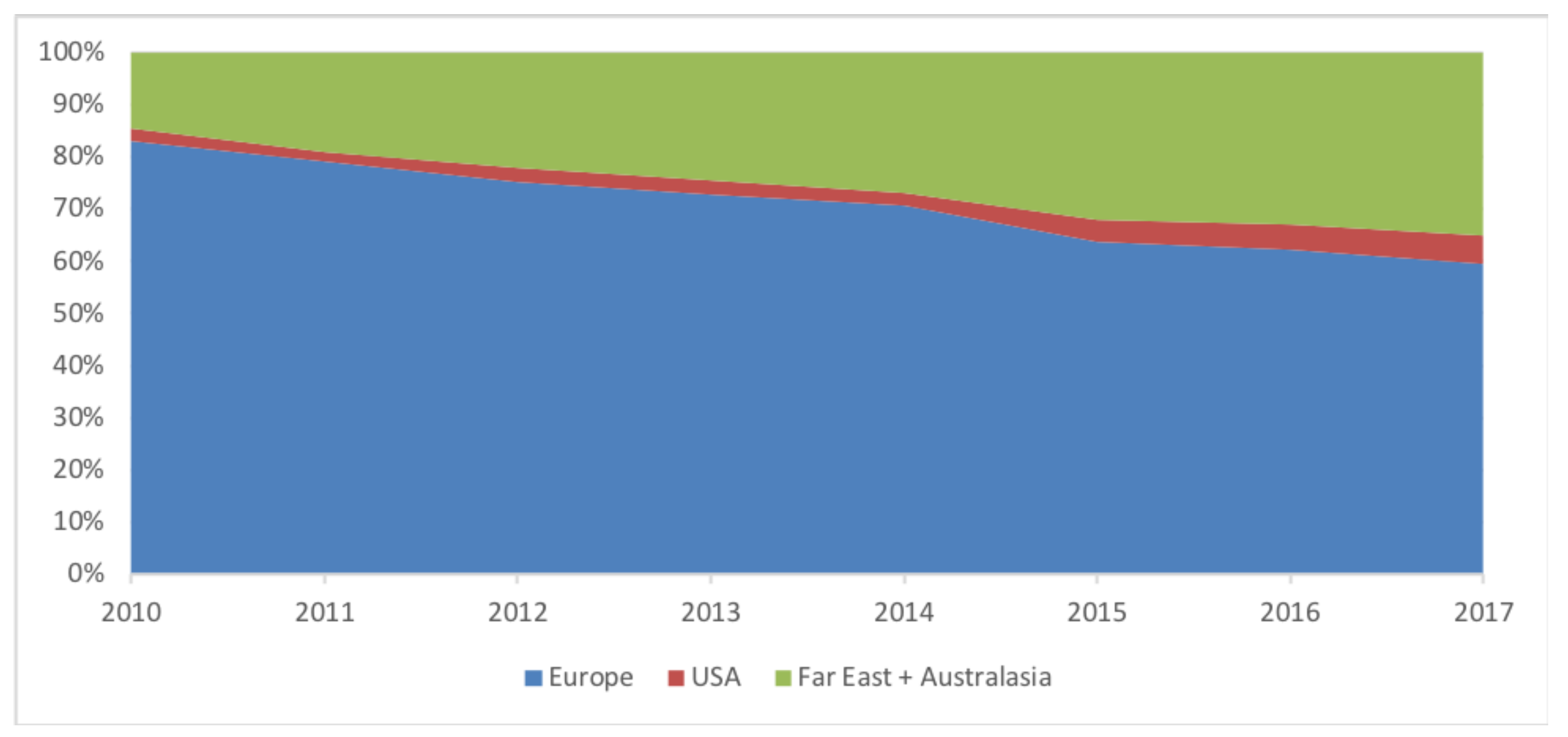

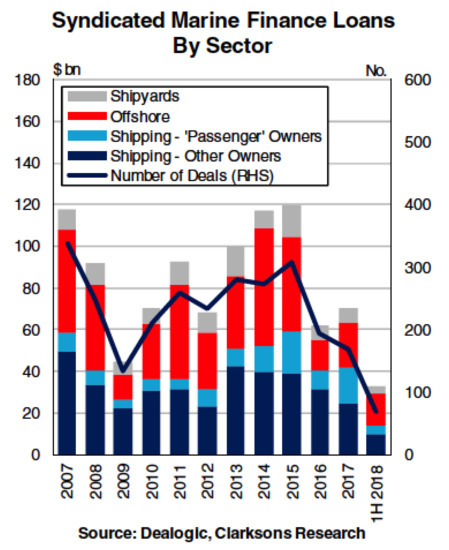

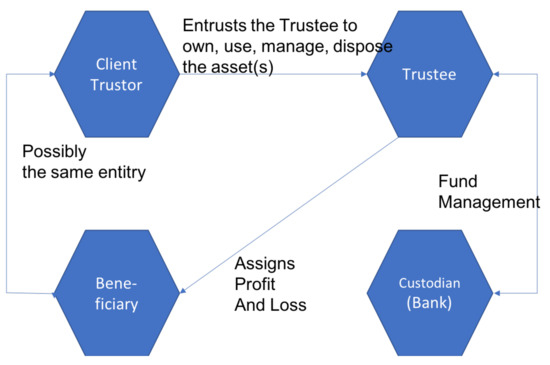

In this paper, the trust property will be used as an illustration against generic property provisos under the Chinese law. It is advocated that the transfer of ships as the trust property under the shipping trust fund should comply with the international ship registration framework In most cases, these shipping funds are based on structures, as of Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Basic Structure of Relationships.

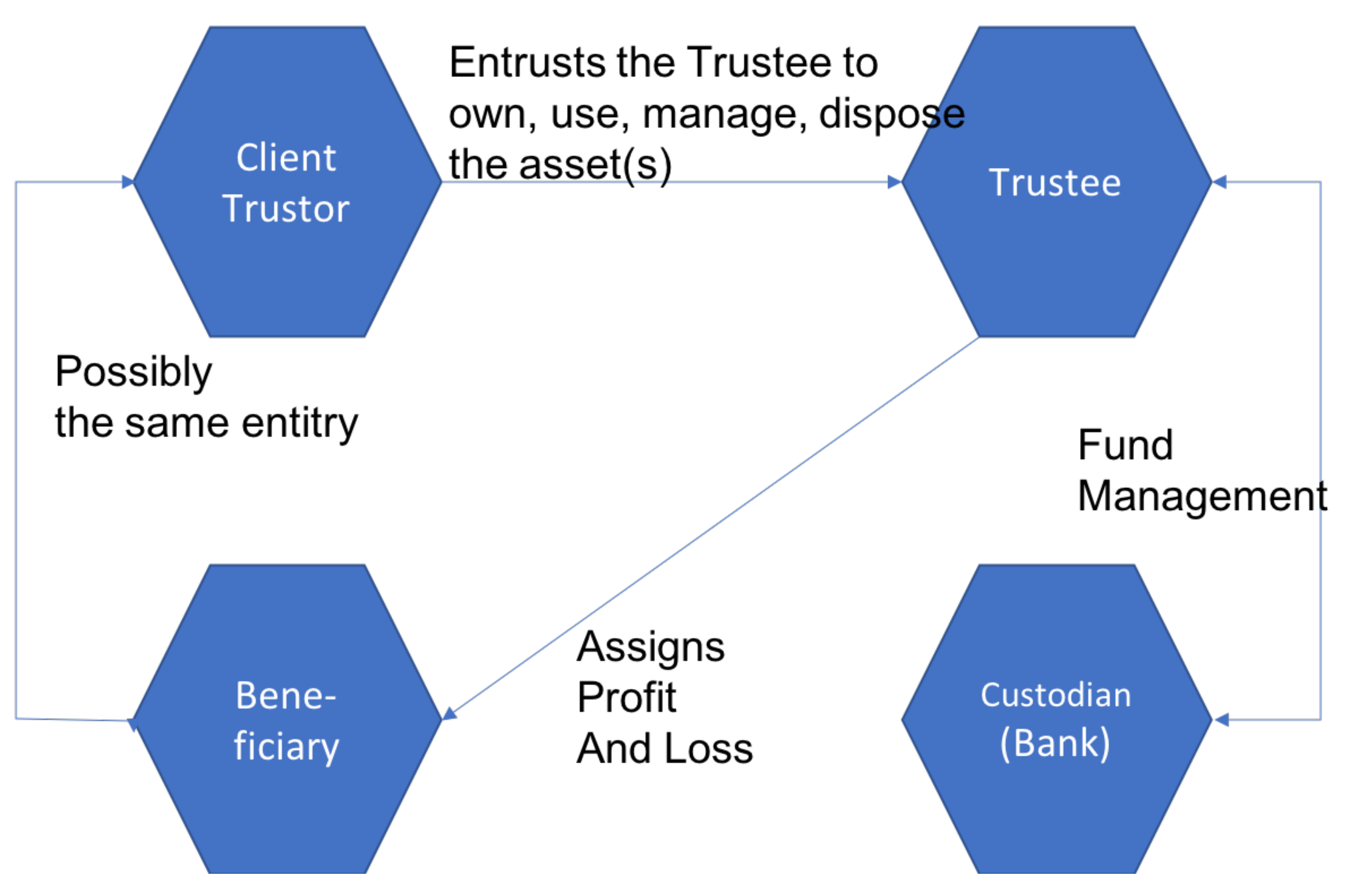

The novelty of the current work is summarised in the effort of streamlining business practices in China with those of mature shipping clusters. Even though the business and the legal practice of shipping trust fund is relatively mature in Singapore and Germany, no relevant specialised legislation and business activities have been made in China yet. Besides the theoretical value of this work there is a keen interest from the industry as the maritime sector is still at an initial stage of evolution compared to the total business volume of trusts in China, valued in trillions of US dollar. Therefore, it is necessary to learn from the advancing practice in other foreign countries and then to ‘localise’ according to China’s domestic legal framework and business practice. Considering the international character of the industry, as well as the fact that a ship as legal asset, is subject to various jurisdictions, this work argues that the ownership of the asset, i.e., the property of a Chinese trust fund should be transferred from the client to the trustee, replicating international experience, as in the case of the German KG and Norwegian KS schemes (Clausius 2015; Johns and Sturm 2015; Mayr 2015; von Oldershausen 2015). The international experience as illustrated in the literature is encapsulated in Figure 8. These schemes enable financial investors to provide capital, mainly equity, that is further leveraged, for the acquisition of ships (tonnage). Equity investors are usually enjoying high yields, as in the case of financial troubles and insolvency they are at the end of the chain. In many cases, the ships belong to a specialised legal conduit, and are offered under bareboat agreement to the beneficiary, i.e., an owner or a manager, who will run the ship and generate returns.

Figure 8.

Common International Schemes.

The Chinese shipping trusts are structured similarly to European models, yet the underlying legal relationships are not fully clarified:

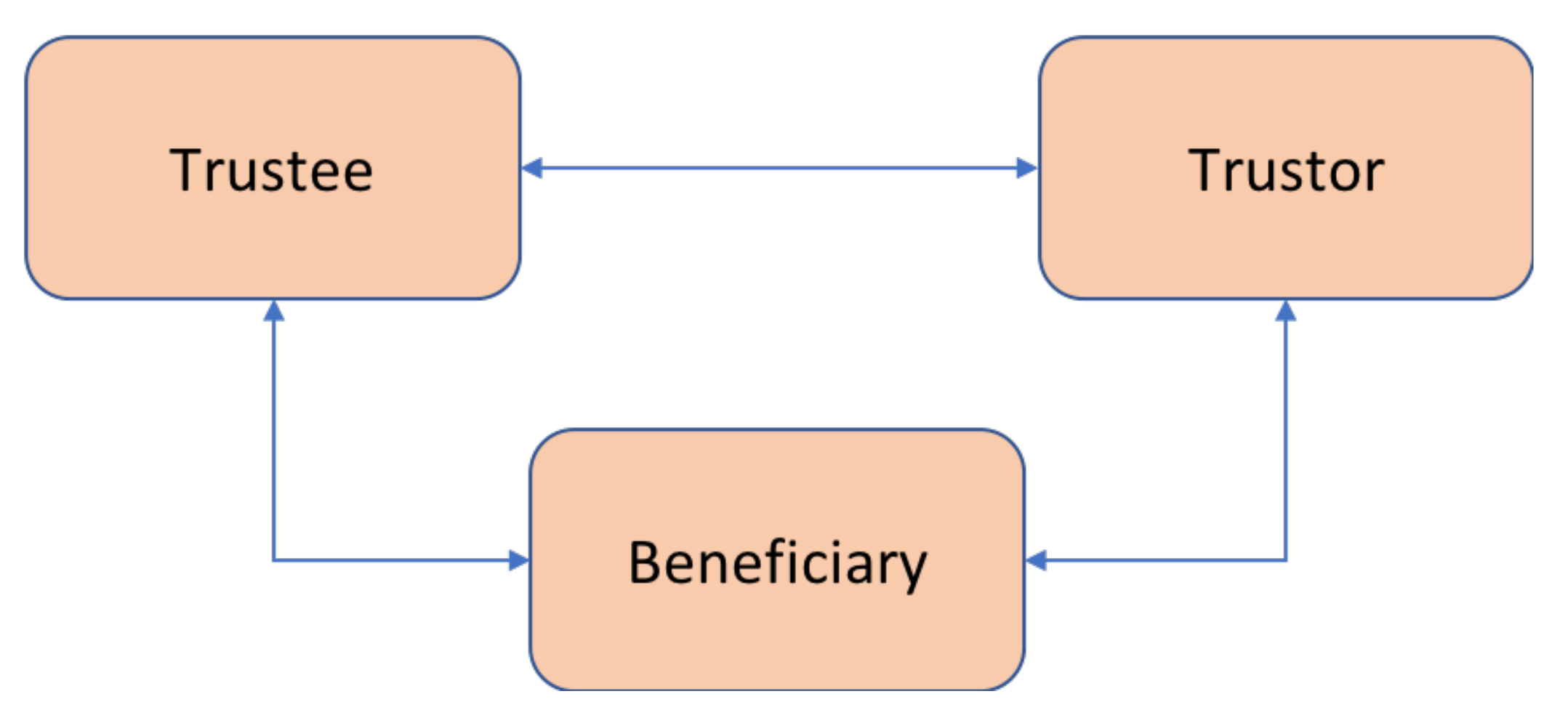

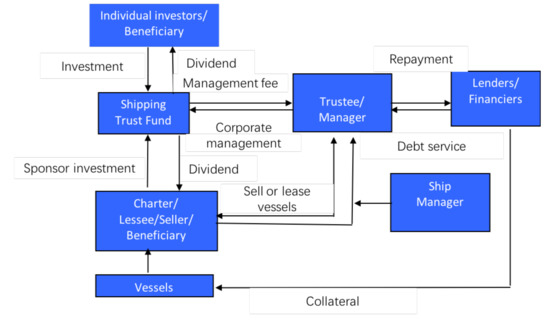

The mechanism of Chinese Shipping Trust Fund (Figure 9) can be compared to the German KG Fund (Figure 8), which is a closed-end fund. Once the shares of the limited partnership shareholder are subscribed, the KG fund will no longer be open for new investors to join. In addition, the fund can also obtain the participation of bank capital through leverage, which is used to purchase ships and then engage in leasing or bareboat schemes. The sponsor of the KG fund is the general partner of the fund, most commonly an owner or an operator, i.e., a strategic investor. The general partner generally invests a small amount of own funds, and then raises funds from the limited liability partners in the open market. The fund then borrows from the bank a sum with the acquired (or contracted) vessels as a collateral guarantee. Once the bank loan is fully repaid, the income from the lease or bareboat is allocated according to the investment share. In contrast to alternative financing sources, in the KG schemes both the general partner and the beneficiary are the same, while the KG fund’s ownership and management rights are separate.

Figure 9.

Common Scheme for a Chinese Shipping Trust Fund.

Although the KG fund is a limited partnership company in nature and different from the Chinese shipping trust that fully adopts the property trust nature, the KG fund helps to reduce the corporate debt ratio and avoid double or other taxation burdens. The KG fund system is still of great reference and value for China. For example, the operation mode of special purpose vehicle in KG fund and its leveraged financing method are worthy of reference for Chinese shipping trust tund when it comes to design the fund exit mechanism and conduct financing in open market.

The fact that shipping trusts are at early stage of development in China as well as the increased significance of China in the global maritime business and ship finance markets in particular, triggered further this research effort. Shipping trust funds in China, as one of the innovative types of shipping finance globally, will contribute to the expansion of financing sources in the Chinese and international shipping industry, promoting and upgrading Chinese maritime and marine clusters. Hence, the political goals of China for supremacy in the maritime business and markets are fuelled further, as the available financial tools may support the integration of industrial chains, improve national and regional policies in shipping, following the example of other States in the past.

The structure of this document is as follows: in Section 2 the problem of ownership is analyzed, aiming at introducing the reader in the complexity and interdisciplinary nature of this issue. Then, in Section 3 the argumentation for transferring the property to the trustee is developed, considering contract law (Section 3.1) and registration aspects (Section 3.1). It should be noted that the analysis considers predominately the Chinese legal provisos, as the German and the Norwegian are widely examined in the literature (e.g., in Clausius 2015; Johns and Sturm 2015; Mayr 2015; von Oldershausen 2015). This is analysis offers a new perspective and bridges this gap in the relevant literature. Section 4 concludes the analysis and the argumentation.

2. The Issue of Ownership in a Chinese Shipping Fund

2.1. Introduction to Shipping Trusts in China

Shipping trust fund means a collective investment plan where capitals are raised (without targeted investors) by establishing trust fund contracts and issuing the fund share to constitute the trust fund to be invested in the shipping industry. In practice, the shipping trust fund, as a trust-type fund, operates on the basis of trust laws. Specifically, the investor (client) participates in the fund plan by subscribing fund shares (the trust unit) to appoint himself/herself or others as the beneficiary, while the trustee (the trust company) issues the unit fund share certificate to the investor depending on the trust fund contract, nominally possesses the fund asset (trust property), acts as a fund management organization to manage and operate the fund or chooses other professional investment managers to manage the fund, and entrusts commercial banks with certain qualifications to safeguard the fund. Meanwhile, the trust property is independent of the fixed property of the client, trustee, and custodian and is separate from other property of the trustee and the custodian. Generally, the shipping trust fund is launched by one sponsor and established by the shareholders (usually the main investor of the fund) and is then sold on the capital market (no targeted objects) to raise the unit trust fund. After the raising of the fund, the manager of the shipping trust fund purchases ships with the fund capital and leases the ships to the lessee by the way of long-term lease to obtain stable rental incomes. The trustee manages the fund on behalf of the unit trust holder (i.e., the client) based on stipulations of the trust contract and charges management fees as agreed. The trustee is entitled to choose a ship management company to sign a ship management agreement with the ship management company to let it manage and operate the ship purchased with the fund (generally, the ship management company is established by the fund sponsor).

The above explains at large the structure of Figure 7, and illustrates the legal relationship of both parties of the shipping trust fund, as usually considered in the trust fund contract. Hence, the shipping trust fund is a trust fund in nature and should abide by the basic principles of trust laws. In practice, there are two operation modes of the trust fund:

- The trust company and the fund management team are responsible for the work in which they are individually specialized—i.e., the trust company is only responsible for raising the trust fund capital from investors and plays a role of the trustee, while the fund management team as the manager of the trust fund is responsible for the specific operation and investment decision-making of the fund.

- The fund is dominated by the trust company—i.e., the trust company is responsible for the raising and management of the whole trust fund but usually recruits a fund management team as the external investment counselor to provide it with legal consultation services. However, Article 26 of China’s Regulations on Administration of Trust Companies stipulates: “The trust company should manage the trust affairs personally.” Therefore, under the Chinese law, the shipping trust fund should be operated in the mode of proprietary trading. However, trust companies are at the stage of conversion from the financing function to the management function; thus, they can recruit professional investment advisors to provide advices or guides for their investment decision-making in terms of assets, business, and technology to manage and operate the trust fund property. This not only guarantees that the trust company independently manages the trust property under the shipping trust fund, but also helps in the professional management of the trust property and gives full play to the financing and investment functions of the shipping trust fund in the shipping and finance fields.

It is worth noting that the trust law system stems from Britain and is developed based on the Ownership Segmentation Theory—the trustee has the ownership of the trust property under ordinary laws, while the beneficiary has the ownership of the trust property under the law of equity (the object of property ownership in Britain is not the object but the right) (Penner 2014). This does not coincide with the inherent philosophy of a single subject in the continental law system and creates lots of trouble for the continental law countries in the process of transplanting the trust law system (Li 2009; Sun and Zheng 2009). Hence, the continental law countries have carried out reform and development in terms of the adaptability of the trust system in the process of transplanting the trust law system in combination with their own traditional laws to strengthen the rights and supervision of the client on the premise of inheriting the basic legal principles of trust laws (i.e., the ownership of the trust property separating from the interests, independence of the trust property, limited liability, and the continuity of trust management) (Scott and Fratcher 2006; Zhai and Yang 2008; Zhou 1996). China can also be expected to face some problems of important basic theories when introducing the trust law system, especially the ownership of the trust property. This will affect and decide the establishment, operation, supervision, and exit mechanisms of the shipping trust fund. The shipping trust fund capital is raised by establishing trust fund contracts, thus, its operation should abide by stipulations of the trust law. In other words, the stipulations on the establishment of the trust, the ownership and the beneficial right of the trust property, and the rights and obligations of the concerned parties of the trust in the trust law are general stipulations and hence applicable to all the trust activities within the Chinese territory.

2.2. Explaining the Current Framework

A shipping trust fund in China is a pool of capital provided by many investors; these investors might be legal or natural persons. The trust company, acting as the trustee, manages the fund through its own brand (self-management) and operates the asset under the fund. The legal status of the fund is a mix of a business and of a self-benefit scheme. The fund itself has no independent capacity as a subject of law. Instead it is the pool of capital raised by the trustee through collective schemes. The ownership of the trust assets under the fund is transferred to the trustee. The trustee possesses, uses, makes profit and disposes the trust assets on his own account and brand name. Should the trustee obtain, transfer or eliminate the asset then relevant registration and proof of compliance with the relevant laws and administrative regulations is expected; this is a critical issue considering the complexity of procedures.

The shipping industry is a capital-intensive industry, and its growth is inextricably linked to the availability of capital, in terms of equity, debt or leasing. As shipping companies need to constantly renew or expand their fleets, the demand for funds is increasing, as shown in Figure 2. Most commonly, retained earning and profits from asset play do not suffice for their renewal or expansion needs. Therefore, ship finance has become an indispensable part of the development, growth and evolution of the shipping industry. However, ship finance is a relatively conservative industry, and ordinary plain-vanilla financing, i.e., mortgaged loans provided by a bank along with an equity contribution from the owners, remains popular and common, if only the funds are available and the banks able to provide capital. Nevertheless, this is not the case as shown in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5. The increase in ship finance demand resulted in alternative shipping finance methods such as mezzanine financing, tax-based leasing, shipping funds and trusts that are constantly emerging in business ventures and will be further developed as the business practice matures. In the near future, the tools for ship finance will be more diversified and structured; more off-balance sheet financing methods are expected to dominate the market. From a policy point of view, the German KG Fund, Singapore Maritime Trust Fund, Norwegian KS Fund, South Korea SIC Fund and other shipping fund schemes, are used as models, due to the innovation they introduced in the past, as well as by illustrating their limitations. Hybrid schemes based on these models gradually become a trend in ship finance.

In this regard, the Chinese model, i.e., a Shipping Trust Fund in China flexibly combines the concepts of ‘fund’ and of the ‘trust’, which is beneficial for the protection of the specialized investment activities and of the effective diversification of assets. Under this scheme, it is possible to make full use of foreign investment, say of foreign shipping funds that raise funds from many investors, where also Chinese can invest, combined with Chinese private capital; the total sum can be further leveraged by usual asset securitization thus combining capital contributions from financial investors and shipping related ones. Apparently, the goal is no other than to provide yields and security to financial investors, and organic growth and in-sector allocation of funds for the industrial investors. The funds are managed by professionals, invest in the purchase and construction of physical and highly liquid assets, such as sea-going vessels, operated under a transfer, such as a bareboat, or a lease or a trust, return income from the hire of the vessels to investors. This way, financial and operational knowhow is transferred via Chinese financial schemes to the local markets that will eventually enhance China’s competitiveness in the international shipping industry.

In addition, the dynamism of the Chinese economy generates the necessary surplus for investment in ship finance, both globally and locally. Considering ship finance as the osmosis point of the maritime and of the financial markets it is of fundamental importance to keep this relation healthy and independent from peculiarities of the local regulatory framework. At present, China’s ship financial services seem relatively outdated, that seriously restrict the sustainable development of China’s shipping and financial industries as argued above. Although the “Company Law of the People’s Republic of China” (hereinafter referred to as “Company Law”), “The Partnership Enterprise Law of the People’s Republic of China” (hereinafter referred to as “Partnership Enterprise Law”), “The Trust Law of the People’s Republic of China” (hereinafter referred to as the “Trust Law”) have dedicated provisos for the establishment of shipping funds, there is still a need for further development that fosters the generation of a market with global visibility and importance. The above Laws need further clarification in order to support more business ventures.

Trust funds for shipping in China are the product of the evolution of the interaction of marine with the financial industries. In China, the set-up, issuance, operation and supervision of a Shipping Trust Fund will have a direct impact on many existing laws and regulations, such as the above mentioned, trust law, company law, property law, contract law, financial law, tax law, among others; this impact dictates the need to rethink the fundamentals and devise solutions for foreseeable issues. As an example, the definition of the concept of a shipping trust fund, its set-up and its relation to the current international practice of ship and mortgage registration should be clarified.In this regard, the protection of rights as well as implied obligations among all parties involved should be further clarified, including tax and foreign investment treatment. These fundamental questions raise many theoretical, methodological and practical challenges.

In order to address some of these challenges, this paper will consider first the protection of the beneficiary rights in a Shipping Trust Fund as the starting point and core, focussing on the legal status and the legal relationship of the trustee and of the investors. Currently there is no available literature, neither in Chinese nor in English, hence this work offers the very first foundation for academic research. The goal of research should be not to only to analyse the current framework but also to propose solutions, based on the international experience. Last but not least, as shipping markets are truly international, any improvement in the local framework, in this case of the Chinese particularly, will have a global impact and therefore will spark interest for further research by academics and contributions by professionals.

In essence, the analysis has to begin with the Article 2 of of China’s Trust Law, that stipulates: “Trust refers to the act in which the client, on the basis of confidence on the trustee, entrusts certain property rights it owns to the trustee and the trustee manages or disposes of the property rights in its own name in accordance with the intentions of the client and for the benefit of the beneficiary or for specific purposes.” This Article follows the principle of separation of the ownership and interests of the trust property but does not specify the owner of the trust property—i.e., whether or not the ownership of the trust property is transferred to the trustee from the client because of the establishment of the trust relationship. In fact, the legislators of the China’s Trust Law avoid the term “transfer of the trust property” in definitions, but the wording “entrusted to” is likely to lead to more misunderstandings. The word “to” can be understood as containing the meaning of “transfer”, but the wording “entrusted” is likely to confuse the relation between the “trust” and the “entrust”. The stipulations on the transfer of the ownership of the trust property in the trust law of China are vague, weakening the independence of the trust property and negatively affecting the trust system. First of all, it is not conducive to the establishment of the legal status of the trustee. If the trust property is not transferred, the trustee can independently dispose of it in his/her own name. Trust is different from entrusting. Under the entrusting (including indirect agency) system, the trustee should manage and dispose the property within the authorization scope of the client, which is not in conformity with the independent status of the trustee in the trust system. Therefore, it is likely to replace the trust system with the entrusting system. Second, it does not help to guarantee the rights and interests of the beneficiary and provides people outside the trust relationship with opportunities of claiming the trust property.

Most scholars claim that the trustee should only have the operation management right of the trust property rather than ownership, in accordance with the stipulation of Article 2 of China’s Trust Law. In addition, Paragraph 1, Article 13 of China’s Ship Registration Regulation stipulates that no person other than the ship-owner should be registered as the ship-owner; thus, the legal identity of the ship-owner should be verified at the time of registration. The ownership of the trust property should still belong to the client, even though the client has put his/her property under the trust, becoming an integral—the trust fund—for the purpose of the trust. In addition, Paragraph 2, Article 14 of the Trust Law introduces the object substitution principle with regard to the trust property in the British law of equity, so property generated by the trustee from management operation, disposal or in other situations in his/her own name in accordance with Article 2 of the Trust Law should be classified into the trust property. Hence, the client should also be registered as the owner of the ship purchased with the shipping trust fund. Theoretically, the shipping trust fund can refer to regulations on the co-ownership of ships in Article 8 of China’s Maritime Commerce Law in combination with the fund principle to specify that clients of ships, as the trust property under the shipping trust fund, can be registered as the share-based co-owner of the ship in accordance with the investment shares of each client. Co-ownership of ships under the shipping trust fund in China is not exactly the same as that stipulated in Article 8 (wherein ships should be registered under the name of the manager), but if the ownership of the trust property is not transferred to the trustee from the client, the establishment, operation, supervision, and exit of the shipping trust fund will faces impediment in terms of legislation or legal conflicts will be caused (Jia 2005).

- According to the regulation of Article 97 of China’s current Property Law and Article 16 of Maritime Commerce Law, the disposal of property in common should be approved by more than 2/3rd of the co-owners; thus, the disposal of the ship by the trustee of the shipping trust fund should be approved by co-owners of the ship, which conflicts with the professional management and independent operation of the trustee and does not help to reduce investment costs of the trust property.

- If the client under the shipping trust fund places the cash under the trust fund of the trustee, the ownership of the cash should be transferred to the trustee when it is delivered to the trustee, because cash belongs to the generic good. But a practical problem is: If the trustee purchases ships with the capital, is the owner of the ship the client or the trustee? If the trustee is registered as the owner, does it conflict with the regulation of the current trust law, which specifies that that the client still enjoys the ownership?

- If the ownership of the trust property is not transferred, it will not help in the establishment of the independent legal status of the trustee or guarantee the rights and interests of the beneficiary (Chen 2011). If the ownership of the trust property is not transferred, it will not be confirmed effectively whether the client has mortgaged the trust property to others or will not free assets from the effect of ownership claim effect. As a result, the non-client beneficiary trust under the current trust law exists in name only and significantly affects the execution scope of the right of revocation of the beneficiary, since the usufruct (the exclusive rights of the non-owner for including possessing, employing, and benefiting from others’ objects) of the beneficiary is not specified and both the client and the beneficiary have the right to revoke the trust (Article 22 and Article 49 of the Trust Law). This is likely to give rise to conflicts between their respective rights of revocation in the non-beneficiary trust (Edwards and Stockwell 2005).

In addition, some scholars claim that the legislation mode of the ownership of the trust property enjoyed by the client has significant defects:

- The trustee’s disposal of the trust property lacks basis. In the period during which the trust is in force, the trustee needs to dispose the trust property in his/her own name in order to realize the objectives of the trust, which requires the trustee to either possess the ownership of the trust property or obtain the authorization of the client. However, there is a large degree of contact with other units in the trust affairs and the counterparty changes frequently, making it impractical for the trustee to ask for the authorization of the client with respect to any a matter.

- In the case of the testamentary trust, the ownership of the trust property cannot be specified. According to the regulation of Paragraph 2, Article 8 of the Trust Law, the testamentary trust comes into effect after the client is dead, and a dead client will certainly not possess the ownership of the trust property, as stipulated in the General Principles of Civil Law. Hence, it conflicts with the regulation that the ownership of the trust property belongs to the client.

- There will be difficulties in the actual execution if the trust property belongs to the client. The trustee possesses only the rights of management and disposal and not the ownership; thus, the trustee cannot independently dispose the real estate in his/her own name, because the disposal of the real estate must happen on the basis of publicity of the property right registered.

Hence, from the perspective of the trust law theories, the “trust” established on the basis of entrusting does not have the legal essence required and can hardly give play to special functions of the trust law system (Zhang 2004).

3. Transferring the Asset; a Justification

3.1. A Chinese Contract Law Perspective

Under Anglo-American laws, trust law is independent of contract law, and the rules of contract laws are not applicable to trusts. Once the client establishes a valid trust, he/she is independent of the trust relationship. In other words, once the trust is established and becomes valid, there is only the ownership of the trust property possessed by the trustee under common laws and the ownership possessed by the beneficiary under the law of equity. The client does not possess any rights to the trust property and cannot change stipulations of the trust or revoke the trust (unless otherwise specified in the trust document). This is obviously embodied in the legislation of many countries. For example, Restatement of the American Law of Trusts uses a large space to stipulate in details the rights and obligations of the trustee, responsibilities which should be borne by the trustee due to contracts or the tort, compensation of the trustee, remedy of the beneficiary, and remedy of the beneficiary for the third party, while neither the status nor the right of claim of the client is stipulated. The trust law in Britain is similar.

On the contrary, the continental law countries have had sound contract law systems or concepts since the time that trust was introduced; thus, their trusts are usually established in the form of a contract. According to the basic principles of contract laws, the client—one party to the contract concerned about the establishment of the trust—should have the corresponding legal status and rights. Considering this case, usually there are stipulations about the status and rights of the client in the trust relationship after the trust is established in the trust law of continental law countries or regions, such as Japan, South Korea, China Taiwan, etc. Stipulations on rights of the client in China’s Trust Law are more detailed. In Articles 19–23, there are stipulations regarding the client’s right to be informed, the right of requiring adjustment of the trust property management method, the right to revoke the trustee’s disposal of the trust property, the right of claim, the right to dismiss the trustee, etc. Contracts regarding trust establishment in the continental law countries are, in nature, contracts involving third parties, where rights of the third party (beneficiary) are stipulated.

Theoretically, the beneficiary of the shipping trust fund usually only has rights, and the expenditure incurred by the trustee in handling trust affairs and debts owed to a third party should only be compensated within the limits of the trust property. Hence, the beneficiary does not bear unfavorable obligations or responsibilities based on the trust fund contract. In addition, the trust fund contract is a result reflecting the consensus of both parties concerned. The client and the trustee should fulfill their respective obligations based on the concluded trust fund contract. The trustee has the right to dispose the trust property within the scope of the contract and the client cannot interfere in such disposal at will. This shows that under the shipping trust fund and after the client and the trust company reach a trust fund contract, the client’s rights are bound by laws (e.g., Trust Law) and by the trust fund contract. From the perspective of legislation of countries where the Anglo-American law system is applied, rights of the client and execution of the beneficiary can totally be stipulated in the trust fund contract, which helps in the transfer of the trust property from the client to the beneficiary and to distinguish the self-beneficiary and non-beneficiary trusts. Therefore, the status of the client could be weakened, and the rights and obligations of the client should be simplified. It should be stipulated that the client cannot interfere in the trustee’s disposal of the trust property and the ownership of the trust property should be transferred to the trustee to comply with the weakened status of the client in establishing the shipping trust fund or in preparing laws and regulations relating to shipping trust funds (Li 2012).

3.2. Effects of the Registration System and Solutions

According to Article 10 of China’s Trust Law and the Maritime Commerce Law, transfer of the ownership of ships should comply with the “registration antagonism” —i.e., the delivery of ships will have the effect on the transfer of the ownership between the buyer and the seller while cannot be against a third party. First, the “antagonism effect” of the registration is mainly embodied as follows: As for the third parties who do not have a good understanding of the actual change situation of the ownership of ships and take legal actions at goodwill, the ownership of ships can be confirmed based on the registration, and unregistered ship-owners cannot antagonize the third party based on the actual ownership possessed by them. Second, the probative effect (publicity effect) of the registration is mainly embodied as follows: Registered ship-owners can prove their ownership with the registration or the registration certificate. It cannot be denied that the registered owner is the obligee if the third party cannot provide contrary evidences. The registered ownership can be denied if the unregistered ship-owner can provide sufficient evidences to prove his/her ownership, so that the unregistered ship-owner can claim his/her ownership and the right of claim (Huang 2007). Therefore, under the shipping trust fund, the publicity should be registered after the trustee obtains the ship’s ownership in the mode of publicity of the ship delivered; otherwise, antagonism against a third party will be invalid.

3.3. The Justification of the Transfer

In terms of China’s shipping trust funds, if the ownership of a ship, as the trust property, is not transferred to the trustee, it is unfair for concerned parties in the ship relations and the transport relations under some cases. For example, the implementation of the Trust Law may not enable the maritime request obligee to fairly retain or auction concerned ships trusted by the ship-owner and responsible for the maritime request. Specifically speaking, if ships have been trusted to the trustee for management and operation and then the original ship-owner rents out (especially in the case of only bareboat charter) the ship, after damage or shortage of the cargo occurs, the cargo owner cannot retain the concerned ship legally, even though the person responsible for the maritime request is right the ship-owner, because there are strict limitations about compulsory execution of trust property in Article 9 of the Trust Law, which state that the trust property can be disposed compulsorily only when the creditor has the right of priority compensation of the trust property before establishing the trust and the creditor has to pay off debts incurred in the trustee’s handling with trust affairs and taxes under the trust property. It is unfair to the cargo owner, since the client is responsible for the maritime request, as well as being the ship-owner and the beneficiary of the trust property. However, according to stipulations of Article 23 of the Special Maritime Procedure Law, if the ship-owner or the bareboat lessee is responsible for the maritime request, the maritime request obligee can retain and action all ships or the concerned bareboat rented by the client. Hence, if the concerned ships become trust property, unless the creditor has the right of priority compensation of the trust property before establishing the trust (the responsible person is the trustee in the second situation, where the trust property can be disposed compulsorily as stipulated in Article 17 of the Trust Law, while the third situation is unrelated to the general creditor), the maritime request obligee cannot retain or auction all ships or the concerned bareboat rented by the client, even though the client—as the ship-owner or the bareboat lessee—is responsible for the maritime request (Yan 2004).

Besides, according to Article 17 and Article 37 of the Trust Law, if the trust property is the ship and the trustee is responsible to the maritime request obligee for operating the trust ship (handling trust affairs), the general maritime request obligee (not referring to the maritime request obligee in several cases stipulated in Paragraph 1, Article 23 of Special Maritime Procedure Law) can retain and action the trust ship, even though the ship-owner or the bareboat lessee is not responsible for the maritime request. Moreover, the principle of limited liabilities of the trustee is adopted in the Trust Law. However, according to Article 22 and paragraph 1 of Article 23 in Special Maritime Procedure Law, the maritime request obligee should not retain or auction concerned ships not owned by but operated by the operator responsible for the maritime request. Therefore, when a ship as trust property is managed and operated by the trustee, who does not have the ownership of the ship (the ownership is not transferred and still be possessed by the client), the trustee operates the trust ship and owes debts to a third party. Even though the trustee is responsible for the maritime request, the maritime request obligee cannot retain or auction the concerned ship. This shows that according the Special Maritime Procedure Law, the maritime request obligee cannot apply for retaining or auctioning the trust ship managed by the trustee, while this is contrary to the stipulations of the Trust Law.

Hence, if ships serve as the trust property of the shipping trust fund in China, and their property ownership is not transferred to the trustee and the client is also the bareboat lessee of the ship and assumes legal liabilities thereof, or legal liabilities are incurred for the trustee’s operating and managing of the ship, the maritime request obligee cannot retain the ship fairly and legally. It means that there are contradictions and conflicts between the contents of China’s current Special Maritime Procedure Law and those of the Trust Law. The alignment of China’s maritime legislation and trust law system has not been taken into consideration. On the contrary, if ships become trust property and their ownership is totally transferred to the trustee, the maritime request obligee can apply for retaining the ship in accordance with the second case stipulated in Article 17 of the Trust Law, if legal liabilities are generated when the trustee operates and manages ships, and if it complies with the stipulations of Item 1, Paragraph 1, Article 23 of the Special Maritime Procedure Law. Meanwhile, when the client rents the bareboat and actually operates the trust ship, if the client is responsible for the maritime request, the maritime request obligee can apply for detaining the ship without violating the independence of the trust property in accordance with the third case—“other cases as prescribed in laws”—as stipulated in Article 17 of the Trust Law and the Item 2, Paragraph 1 of Article 23 in Special Maritime Procedure Law. However, if the client is not the bareboat lessee of the ship, the maritime request obligee cannot apply for detaining the ship, which has become the trust property for the sake of responsibility of the client, because the ownership of the ship has been transferred to the trustee and the client is neither the owner of the ship nor the bareboat lessee.

In addition, according to stipulations of Paragraph 2, Article 23 of Special Maritime Procedure Law, the maritime request obligee can apply for retaining and auctioning all other ships of the ship-owner, bareboat lessee, time charter lessee, or voyage lessee responsible for the maritime request. However, if the ownership of the ship, as the trust property, is not transferred to the trustee, although the ship-owner and the bareboat lessee are responsible for the maritime request, the maritime request obligee cannot retain or auction any of their other ships, because the maritime request obligee cannot retain or auction trust ships, even though the ship-owner, bareboat lessee, time charter lessee, or voyage lessee is just the owner or the beneficiary of the ship, except in the three cases stipulated in the Trust Law. In fact, the three cases where the trust property (ship) can be disposed compulsorily as stipulated in the Trust Law are limited to the maritime request arising from the target ship, so it is out of the question that the maritime request obligee retains the ship-owner’s non-concerned trust ships for the maritime request regarding other ships or unrelated to the trust ship (Yan 2004). Therefore, if the ownership of the ship as the trust property is transferred to the trustee, and the client should assume responsibilities for the maritime request regarding other ships or unrelated with the trust ship, the maritime request obligee does not have the right to apply for retaining the trust ship in accordance with either the Trust Law or the Special Maritime Procedure Law. Thereby, conflicts in this matter between the Trust Law and the Special Maritime Procedure Law can be avoided.

Some scholars think that “transfer of the property right” is a necessary element of the trust’s coming into effect in the Trust Law. Specific stipulations on the transfer of the ownership of trust property in the Trust Law are embodied in many aspects of the Law. If the ownership of the property is not transferred, there will not be the stipulation that the trustee “obtains” the trust property for his/her promise of trust, as stipulated in Article 14 of Trust Law or the stipulation: “The trustee should hand over the trust property to a new trustee after termination of responsibilities of the trustee,” as stipulated in Article 41 of the Trust Law. In particular, it is stipulated in Article 16 of the Trust Law that the trust property should be independent of the fixed assets of the trustee. If the trust property still belongs to the client, it is unnecessary to stipulate that the trust property should be independent of the fixed property of the trustee or trust property of other clients. There are many such similar clauses (Sheng 2003). Since the ownership of the trust property is not specified in the Trust Law, it cannot be determined based on the aforementioned clauses whether the ownership of trust property is transferred or not. Thus, transfer of trust property should be clearly specified in laws in case of ambiguity theoretically and in judicial practices. In fact, the client under the trust does not only transfer the property to the trustee; the transfer of right (i.e., direct change of the property right) takes place instead of the general transfer behavior. This is the most significant characteristic that distinguishes the trust from agency and entrusting (Liu 2011) Transfer of property is a necessary condition of the trust’s coming into effect. Once property is transferred, the trust property becomes independent trust property (Articles 15 and 16 as well as stipulations regarding the beneficiary in the Trust Law), and all independent trust property of the trustee is the hub and basis of obtaining all principles of the Trust Law. It also means that the trustee cannot manage all properties of others and that the trust property can only be possessed by the trustee (Zhang 2002).

However, it is worth noting that after the ownership of the trust property is transferred to the trustee, other problems may arise, such as the capital source of the shipping trust fund. With regard to the problem that the trustee should be registered as the ownership of the ship, in combination with stipulations of Paragraph 1, Article 4 of China’s Maritime Commerce Law and Article 2 of the Regulations on Ship Registration, the right of coastal transportation in China is designed only for the Chinese ships of Chinese citizens or legal persons (as regards legal persons whose registered capital contains investment from foreign investors, the proportion of the contribution amount of the Chinese investor should be at least 50%) who have a domicile or place of business in China, unless otherwise stipulated in laws and administrative regulations. Therefore, foreign citizens and legal persons should be able to obtain the right of coastal transportation operation in China by purchasing China’s shipping trust fund beneficiary certificates; thus, some systems such as the right of coastal transportation in China. cannot play their role as expected (Yan 2004). Therefore, the proportion of the capital source of the shipping trust fund should be specified and restricted (e.g., proportion of the contribution amount of the domestic capital is at least 50%), so that systems such as the right of coastal transportation can be implemented practically and China’s shipping safety and national defense security can be maintained, unless the shipping trust fund is registered in the established Shanghai Free Trade Zone, since restrictions about the proportion of foreign shares in international shipping enterprises based on Sino-foreign joint venture or Sino-foreign cooperation in Shanghai Free Trade Zone will be loosened. Some trial regulations on administration can be prepared by the competent department of transportation under the State Council.

This shows that it is necessary to specify in the laws that the ownership of the trust property after establishment of the trust should be transferred to the trustee to give full play to the advantages and functional advantages of trusts, especially in the case where ships serve as the trust property under the shipping fund. Only if the ownership of the trust property is transferred to the trustee can the independence of the trust property be established so that the trust objective can be realized and the rights and interests of the beneficiary can be guaranteed. Referring to legal stipulations such as Article 1 of Japan’s Trust Law, Paragraph 2, Article 1 of South Korea’s Trust Law, and Article 31 of Restatement of the American Law of Trusts, all of them stipulate the transfer of the ownership of trust property and do not adopt the legislation mode of China’s Trust Law, wherein the ownership of trust property is absolutely avoided. In fact, the ownership belongs to the trustee after the trust property is transferred to the trustee, but is independent of the fixed property of the trustee and has an independent legal status. The rights and interests of the beneficiary are better protected and the trust property remains free from recourse.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion and considering the limitations of capital availability in the global markets (see Section 1), Chinese schemes offering fresh capital in shipping serve both international shipping and Chinese national goals. The shipping trusts can support the growth and renewal of the fleet, and enable further innovation and financial engineering. In respect of the promotion of national policy, shipping trusts can also support the growth of local and related industries, such as of marine equipment and of shipyards, as most of these projects will be materialised in China. Therefore, more stability in the global ship finance markets is expected, along with a strengthening of China’s international shipping and international financial clusters.

Specifically, relevant research on Chinese Shipping Trusts is expected in the following fields, as there is no relevant work available in the literature:

- Financial structures and compatibility of Chinese trusts for intra-jurisdictional projects;

- Use of securities, capital as well as consideration of risk and yield issues;

- Promotion of national shipping and relevant objectives through capital availability provided by shipping trusts;

- Evolution of the Chinese financial and shipping legal framework; and last but not least

- Understanding better China’s maritime strategy that impacts all relevant international markets.

As a new investment and financing mode in the shipping finance field, the shipping trust fund will give full play to functional advantages of the trust schemes, expand the financing channels of China’s shipping industry, guarantee the professionalization and flexibility of shipping investment activities and the diversity of the investment subject, promote upgrading of the shipping industry and integration of industrial chains, promote policy development and financial innovation of national shipping industry, and realise effective linkage of the shipping industry to the finance industry in order to promote the construction of Shanghai International Shipping Center and Shanghai International Shipping Center and contribute to the realization of “The Strategy of National Revitalization Based on Marine Industry Development” and “The Belt and Road Initiatives”. Therefore, it should be specified that the ownership of the trust property under the shipping fund should be transferred from the client to the trustee by introducing foreign practical experience and legislation, in combination with China’s current laws and the specialty and practical demands of the shipping industry.

Author Contributions

H.J. devised the project, the main conceptual ideas and proof outline. Moreover he contributed in the implementation of the research. O.S. aided in interpreting the results and contributed the European perspective. Both authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| KG | Kommanditgesellschaft (in German)—a limited partnership business entity in Germany |

| KS | Kommandittselskap (in Norwegian)—a limited partnership business entity in Germany |

References

- Chen, Xueping. 2011. Nature of rights of the beneficiary of trusts: Human rights or object-based rights. Studies in Law and Business 1: 78. [Google Scholar]

- Clarksons Research. 2019. Shipping Intelligence Network. Available online: https://sin.clarksons.net (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- Clausius, Philip. 2015. Ship Leasing Philip Clausius. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 245–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Richard, and Nigel Stockwell. 2005. Trust and Equity. Harlow: Pearson Education, vol. 1, p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdinand, Peter. 2016. Westward ho—The china dream and ‘one belt, one road’: Chinese foreign policy under xi jinping. International Affairs 92: 941–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralambides, Hercules. 2017. One-belt-one-road (obor), china-eu trade relations, and (geo)political positioning statements. Paper presented at the Intermodal Asia 2017, Shanghai, China, March 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Yongshen. 2007. Change of Property Right and Registration of Ship Ownership. Available online: http://www.simic.net.cn/news_show.php?id=5370 (accessed on 25 March 2015).

- Jia, Linqing. 2005. Personal opinions on the legal nature and structure of trust property rights. Jurist 1: 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, Max, and Christoph Sturm. 2015. The German KG System. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Peifeng. 2009. The primary causes of difficult integration of anglo-american trust property ownership with the continental law property ownership system. Global Law Review 1: 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yu. 2012. The legal status of the client in commerce trusts. Legal Forum 1: 121–27. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Wei, Jingtao Bai, and Hongbin Chen. 2008. Investment and Financing of Water Transportation. Beijing: China Communications Press, vol. 1, pp. 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yingshuang. 2011. Discussion about the nature of trusts—Theory of alienation of trusts. Law Review 1: 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, Daniel. 2015. Valuing Vessels. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 141–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, James E. 2014. The law of trusts. Botterworths 1: 42. [Google Scholar]

- Schinas, Orestis. 2018. Chapter 8—Financing ships of innovative technology. In Finance and Risk Management for International Logistics and the Supply Chain. Edited by Stephen Gong and Kevin Cullinane. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 167–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinas, Orestis, Harm Hauke Ross, and Tobias Daniel Rossol. 2018. Financing green ships through export credit schemes. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 65: 300–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinas, Orestis, and Arnd Graf von Westarp. 2017. Assessing the impact of the maritime silk road. Journal of Ocean Engineering and Science 2: 186–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Austin W., and William Franklin Fratcher. 2006. Scott on trusts. Aspen Law and Business 1: 135. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Xuejun. 2003. Defects of china’s trust legislation and its removal effect on functions of trusts. Modern Law Science 1: 139–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sheu, Jiuh Biing, and Tanmoy Kundu. 2017. Forecasting time-varying logistics distribution flows in the one belt-one road strategic context. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 117: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Yigang, and Yu Zheng. 2009. On the Dissimilation of China’s Trust Institution: Some Comments on Legal Structure of China’s Present Trust Products. Journal of Northwest University of Politics Science and Law 4: 146–53. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. 2019. Review of Maritime Transport 2018. Technical Report UNCTAD/RMT/2018. New York: UNCTAD. [Google Scholar]

- von Oldershausen, Christian. 2015. Other Equity Markets for Shipping. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Yang. 2004. The trust law of the people’s republic of china and china’s shipping law system. Technology and Economy Information of Shipbuilding Industry 1: 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Liangyi. 2003. Ship Financing and Mortgage. Dalian: Dalian Maritime University Press, pp. 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Jinghan. 2017. Does europe matter? the role of europe in chinese narratives of ‘one belt one road’ and ‘new type of great power relations’. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 55: 1162–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Lihong, and Linfeng Yang. 2008. Development Innovation of Trust Products. Beijing: China Financial and Economic Publishing House, vol. 1, p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Tianmin. 2002. Trusts without the Support of the Law of Equity. Ph.D. thesis, China University of Political Science and Law China CNKI, Beijing, China; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Tianmin. 2004. Trusts without the Support of the Law of Equity. Beijing: China CITIC Press, vol. 1, p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xiang. 2014. China Is a Major Country of the Shipping Industry while not a Powerful Shipping Country. Available online: http://finance.ifeng.com/news/special/1stjjnh/20100117/1718843.shtml (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- Zhou, Xiaoming. 1996. Comparative Laws of the Trust System. Beijing: Law Press China, vol. 1, pp. 12–18. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).