Does Death Anxiety Moderate the Adequacy of Retirement Savings? Empirical Evidence from 40-Plus Clients of Spanish Financial Advisory Firms

Abstract

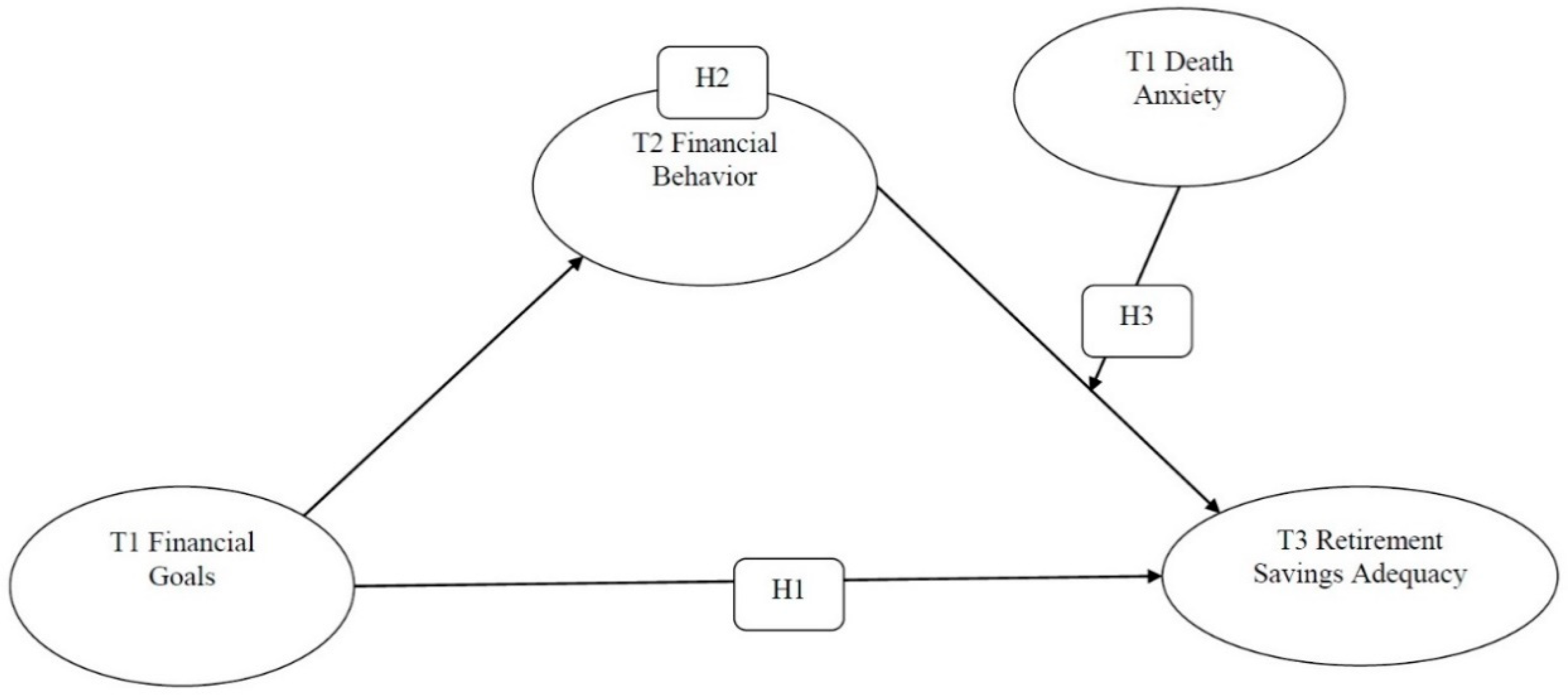

1. Introduction

1.1. Retirement Savings Adequacy

1.2. Financial Goals and Financial Behavior

1.3. Death Anxiety

2. Method

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

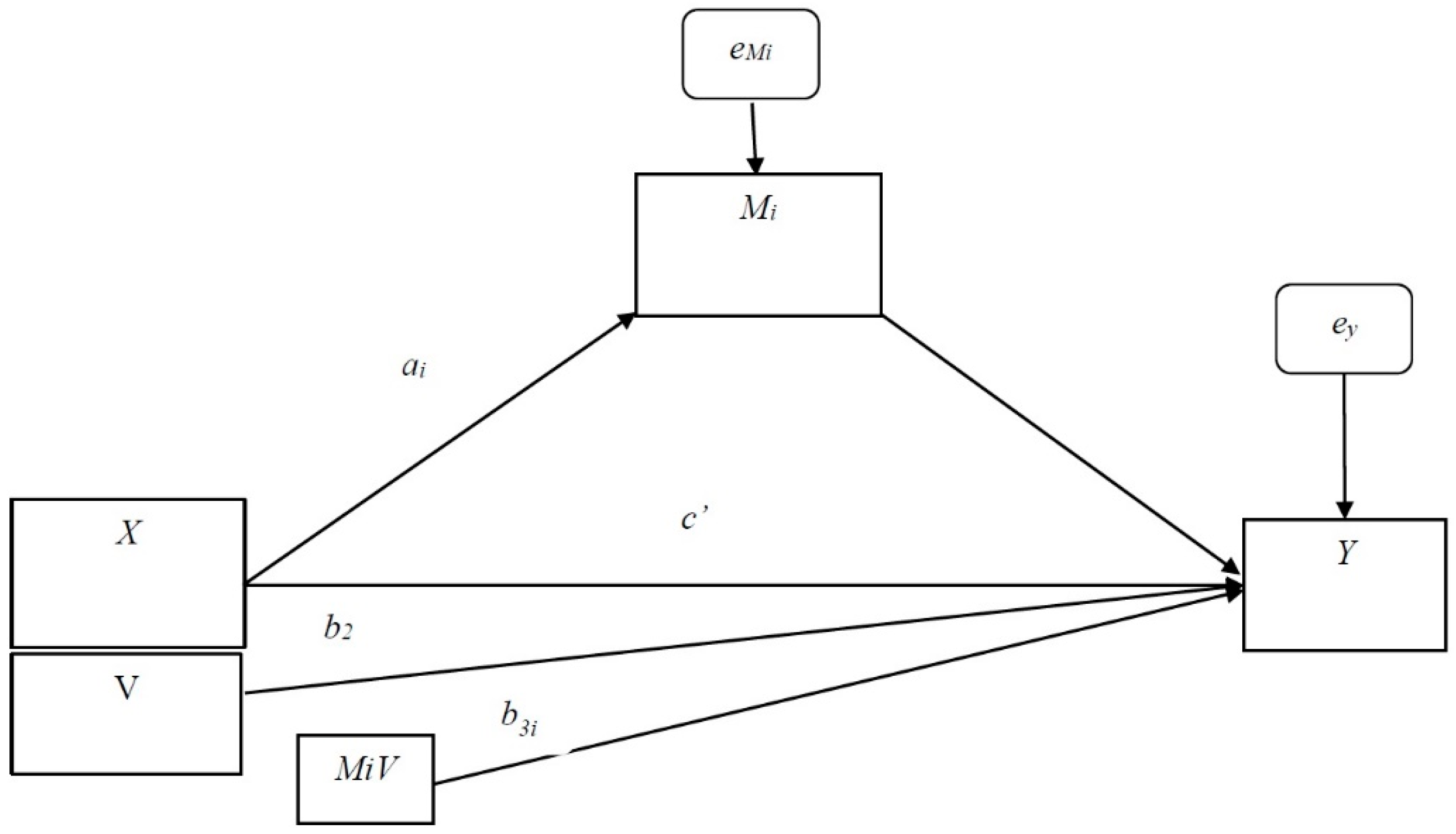

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Simple Mediation Analysis

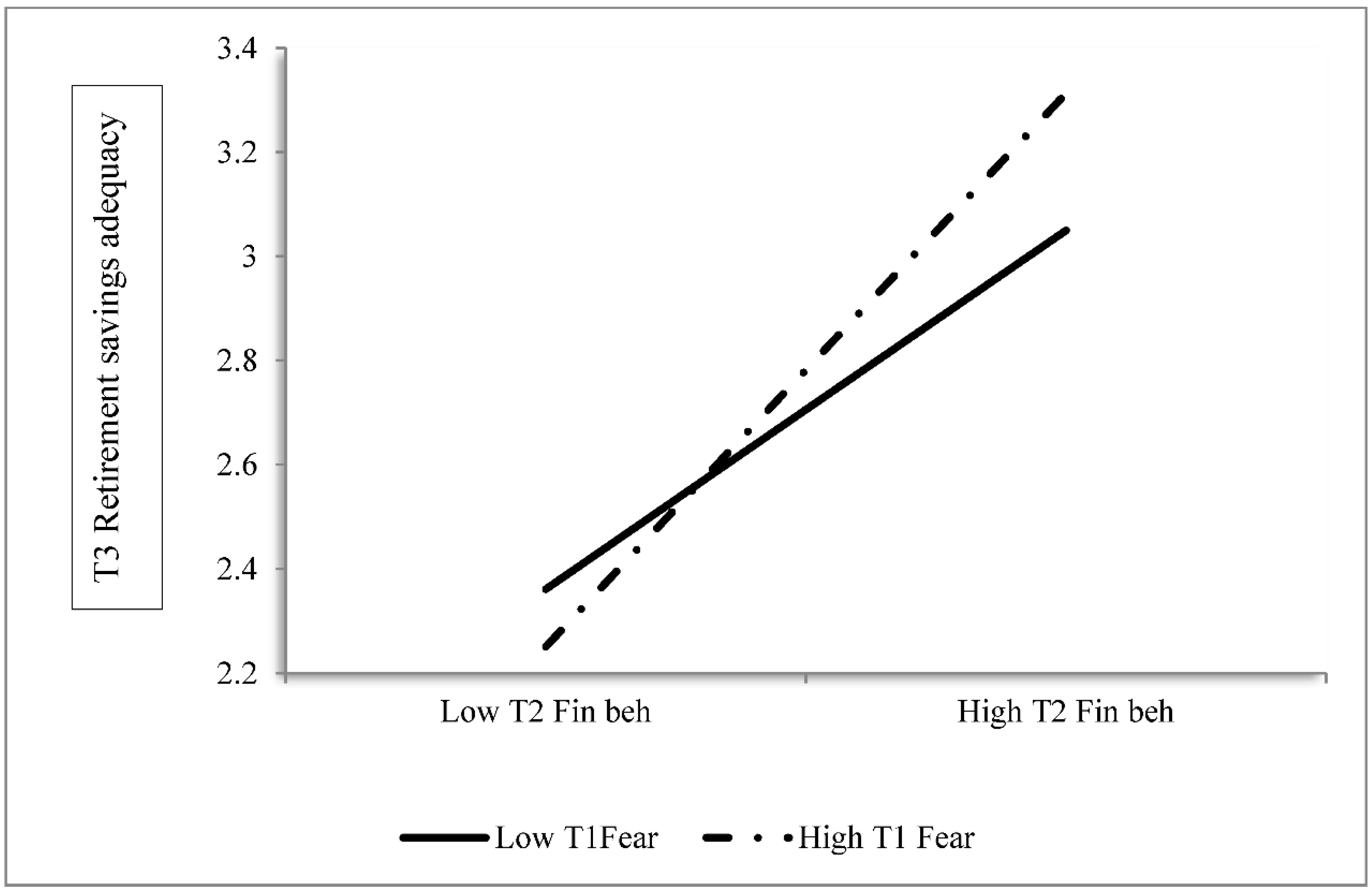

3.2. Moderation Analysis

3.3. Moderated Mediation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Annink, Anne, Marjan Gorgievski, and Laura DulkAnnink. 2016. Financial hardship and well-being: A cross-national comparison among the European self-employed. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 25: 645–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, Jamie, Jeff Greenberg, Jeff Schimel, Tom Pyszczynski, and Sheldon Solomon. 2002. To belong or not to belong, that is the question: Terror management and identification with gender and ethnicity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrowood, Robert, Cathy Cox, and Naomi Ekas. 2017. Mortality salience increases death-thought accessibility and worldview defense among high Broad Autism Phenotype (BAP) individuals. Personality and Individual Differences 113: 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, Ali Shah Syed, Tian Yezhuang, Adnan Muhammad Shah, Dilawar Khan Durrani, and Syed Jamal Shah. 2018. Fear of terror and psychological well-being: The moderating role of emotional intelligence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15: 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermejo, José Carlos, Marta Villacieros, and Invencion Fernandez-Quijano. 2016. Escala de mitos en duelo. relación con el estilo de afrontamiento evitativo y validación psicométrica [Scale of myths in duel relationship with avoidant coping style and psychometric validation]. Acción Psicológica 13: 129–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Iain, and Helene Cherrier. 2010. Anti-consumption as part of living a sustainable lifestyle: Daily practices, contextual motivations and subjective values. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 9: 437–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budowski, Monica, Sebastian Schief, and Rebekka Sieber. 2016. Precariousness and Quality of Life—A Qualitative Perspective on Quality of Life of Households in Precarious Prosperity in Switzerland and Spain. Applied Research in Quality of Life 11: 1035–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Kaileigh A., and Darrell Worthy. 2016. Toward a mechanistic account of gender differences in reward-based decision-making. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics 9: 157–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Wei, Yung-Lung Tang, Sung Wu, and Hong Li. 2017. Scale of Death Anxiety (SDA): Development and Validation. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canepa, Alessandra, and Fawaz Khaled. 2018. Housing, Housing Finance, and Credit Risk. International Journal of Financial Studies 6: 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudelin, Anna, Sini Järvelä, Ville Uusitalo, Maija Leino, and Lassi Linnanen. 2018. The Economic Potential to Support Sustainability through Household Consumption Choices. Sustainability 10: 3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, Yener, Burak Atasoy, Giacomo Morri, and Esra Alp. 2018. Wealth Effects on Household Final Consumption: Stock and Housing Market Channels. International Journal of Financial Studies 6: 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danes, Sharon, and Heather Haberman. 2007. Teen financial knowledge, self-efficacy, and behavior: A gendered view. Financial Counseling and Planning Education 18: 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Fangyuan, Nick Halen, Kristen Moore, and Quinglai Zeng. 2019. Efficient retirement portfolios: using life insurance to meet income and bequest goals in retirement. Risks 7: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, Daniel, Miriam Erez, Uwe Kleinbeck, and Henk Thierry. 2001. Work Motivation in the Context of a Globalizing Economy. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann, Jan, and Marianna Pogosyan. 2013. Emotion perception across cultures: The role of cognitive mechanisms. Frontiers in Psychology 4: 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gennaioli, Nicola, and Andrei Shleifer. 2018. A Crisis of Beliefs: Investor Psychology and Financial Fragility. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gire, James. 2014. How death imitates life: Cultural influences on conceptions of death and dying. Online Reading in Psychology and Culture 6: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, Gabriele, Mindy Shoss, and José María Leon-Perez. 2015. Going beyond workplace stressors: Economic crisis and perceived employability in relation to psychological distress and job dissatisfaction. International Journal of Stress Management 22: 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, Daniel, Eric Johnson, and William Sharpe. 2008. Choosing outcomes versus choosing products: Consumer-focused retirement investment advice. Journal of Consumer Research 35: 440–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, Helen. C., and Douglas Hershey. 2013. Impact of retirement worry on information processing. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics 6: 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Han, Duke, Patricia A. Boyle, Brian D. James, Lei Yu, and David Bennett. 2015. Poorer financial and health literacy among community-dwelling older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Aging and Health 27: 1105–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkin, Ben. 2017. Improving Financial Management via Contemplation: Novel Interventions and Findings in Laboratory and Applied Settings. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hershey, Douglas A., and John. C. Mowen. 2000. Psychological determinants of financial preparedness for retirement. The Gerontologist 40: 687–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershey, Douglas A., Joy M. Jacobs-Lawson, and James T. Austin. 2013. Effective Financial Planning for Retirement. In The Oxford Handbook of Retirement. Edited by Mo Wang. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 402–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hershey, Douglas A., Joy M. Jacobs-Lawson, John McArdle, and Fumiaki Hamagami. 2007. Psychological foundations of financial planning for retirement. Journal of Adult Development 14: 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, Sandra J. 2010. Measuring financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs 44: 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalwij, Adriaan, and Arthut van Soest. 2005. Item Non-Response and Alternative Imputation Procedures. In The Survey of Health, Aging, and Retirement in Europe—Methodology. Edited by Axel Börsch-Supan and Hendrik Jürges. Mannheim: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging (MEA), pp. 128–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kawano, Satsuki. 2010. A sociocultural analysis of death anxiety among older Japanese urbanites in a citizens’ movement. OMEGA—Journal of Death and Dying 62: 369–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leder, Johannes, Leonhard Schilbach, and Aandreas Mojzisch. 2016. Strategic decision-making and social skills: Integrating behavioral economics and social cognition research. International Journal of Financial Studies 4: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindset, Snorre, and Knut A. Mork. 2019. Risk Taking and Fiscal Smoothing with Sovereign Wealth Funds in Advanced Economies. International Journal of Financial Studies 7: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, Rochelle J., William J. Whelton, Jeff Schimel, and Donald Sharpe. 2016. Older Adults and the Fear of Death: The Protective Function of Generativity. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement 35: 261–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, Naomi, and Steven. J. Heine. 1999. Terror management and marketing: He who dies with the most toys wins. Advances in Consumer Research 26: 527–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nepomuceno, Marcelo Vinhal, and Michel Laroche. 2016. Do I Fear Death? The Effects of Mortality Salience on Anti-Consumption Lifestyles. Journal of Consumer Affairs 50: 124–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, Jason W. 2016. An Existential Perspective on Death Anxiety, Retirement, and Related Research Problems. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement 36: 246–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Sojung, Eunsun Kwon, and Hyunjoo Lee. 2017. Life Course Trajectories of Later-Life Cognitive Functions: Does Social Engagement in Old Age Matter? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14: 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, Nancy M., and Thomas Garman. 1993. Testing a conceptual model of financial well-being. Financial Counseling and Planning 4: 135–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, Sonia, Nathan C. Hall, and Timothy A. Pychyl. 2016. Attributions of Responsibility and Blame for Procrastination Behavior. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Ledesma, Armando, and María Montero-López. 2010. Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de ansiedad ante la Muerte de Templer en sujetos Mexicanos. [Templer’s death anxiety scale: Mexican psychometric properties]. Diversitas 6: 135–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawski, Robert S., Douglas A. Hershey, and Joy M. Jacobs-Lawson. 2007. Goal clarity and financial planning activities as determinants of retirement savings contributions. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 64: 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Templer, Donald. 1970. The construction and validation of a Death Anxiety Scale. Journal of General Psychology 82: 165–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás, Joaquín, and Juana Gómez. 2002. Psychometric properties of the Spanish form of Templer’s death anxiety scale. Psychological Reports 91: 1116–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topa, Gabriela, and Teresa Herrador-Alcaide. 2016. Procrastination and financial planning for retirement: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics 9: 169–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waegeman, Anja, Carolyn H. Declerck, Christophe Boone, Wim Van Hecke, and Paul M. Parizel. 2014. Individual differences in self-control in a time discounting task: An fMRI study. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics 7: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Ping, Claudia González-Vallejo, and Zhe H. Xiong. 2016. State anxiety reduces procrastinating behavior. Motivation and Emotion 40: 625–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Zonghuo, and Li Chen. 2016. Income and Well-Being: Relative Income and Absolute Income Weaken Negative Emotion, but only Relative Income Improves Positive Emotion. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Shihong, Xinwei Zhang, Xiaowei Wang, and Guowang Zeng. 2019. Population Aging, Household Savings and Asset Prices: A Study Based on Urban Commercial Housing Prices. Sustainability 11: 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age (years) | 54.52 | 4.50 | n.a. | ||||||

| 2. Education | n.a. | n.a. | −0.12 | n.a. | |||||

| 3. Professional status | n.a. | n.a. | −0.11 | 0.08 | n.a. | ||||

| 4. T1 Financial Goals | 3.26 | 0.81 | 0.18 ** | 0.05 | 0.12 * | 0.87 | |||

| 5. T2 Financial Behavior | 2.76 | 0.84 | 0.15 * | 0.15 * | 0.18 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.90 | ||

| 6. T3 Retirement Savings adequacy | 2.75 | 0.93 | −0.08 | 0.14 * | 0.16 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.83 | |

| 7. T1 Death Anxiety | 2.80 | 0.79 | 0.11 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.82 |

| Outcome Variable: T3 Retirement Savings Adequacy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B Coefficient | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |||

| Constant | 0.0568 | 0.5486 | 3.7495 | 0.0002 | 0.9769 | 3.1368 | ||

| T1 Financial Goals | 0.2986 | 0.0606 | 4.9241 | 0.0000 | 0.1792 | 0.4180 | ||

| T2 Financial Behavior | 0.4758 | 0.0592 | 8.0381 | 0.0000 | 0.3593 | 0.5923 | ||

| T1 Age | 0.0212 | 0.0110 | −1.9174 | 0.0562 | −0.0429 | 0.0006 | ||

| T1 Education level | 0.0375 | 0.0447 | 0.8402 | 0.4015 | −0.0504 | 0.1255 | ||

| T1 Professional category | 0.0332 | 0.0581 | 0.5708 | 0.5686 | −0.0812 | 0.1475 | ||

| Indirect effects | ||||||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |||||

| T1 Financial Goals on T3 Retirement Savings Adequacy through T2 Financial Behavior | 0.0666 | 0.0345 | 0.0060 | 0.1438 | ||||

| Model Summary | ||||||||

| R | R-squared | MSE | F | df1 | df2 | p | ||

| 0.5502 | 0.3028 | 0.6249 | 23.7964 | 5.0000 | 274.0000 | 0.0000 | ||

| Outcome Variable: T3 Retirement Savings Adequacy | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B Coefficient | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |||||||

| Constant | 3.4204 | 0.7596 | 4.5031 | 0.0000 | 1.9251 | 4.9157 | ||||||

| T1 Death Anxiety | −0.3402 | 0.1833 | −1.8562 | 0.0645 | −0.7011 | 0.0206 | ||||||

| T2 Financial Behavior | 0.1264 | 0.1837 | 0.6881 | 0.4920 | −0.2352 | 0.4880 | ||||||

| Interaction term T1 Death Anxiety x T2 Financial Behavior | 0.1408 | 0.0626 | 2.2499 | 0.0253 | 0.0176 | 0.2640 | ||||||

| T1 Age | 0.0212 | 0.0110 | −1.9174 | 0.0562 | −0.0429 | 0.0006 | ||||||

| T1 Education level | 0.0520 | 0.0462 | 1.1242 | 0.2619 | −0.0390 | 0.1430 | ||||||

| T1 Professional category | 0.0562 | 0.0599 | 0.9388 | 0.3487 | −0.0617 | 0.1741 | ||||||

| Model Summary | ||||||||||||

| R | R-squared | SE | F | df1 | df2 | p | ||||||

| 0.5064 | 0.2564 | 0.6689 | 15.6901 | 6.0000 | 273.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||||

| R-square increase due to interaction (T1 Death Anxiety x T2 Financial Behavior): | ||||||||||||

| R2-change | F | df1 | df2 | p | ||||||||

| 0.0138 | 5.0622 | 1.0000 | 273.0000 | 0.0253 | ||||||||

| Conditional effect of T2 Financial Behavior on T3 Retirement Savings Adequacy at values of the moderator (T1 Death Anxiety) | ||||||||||||

| T1 Death Anxiety | Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | ||||||

| 2.0040 | 0.4086 | 0.0774 | 5.2814 | 0.0000 | 0.2563 | 0.5608 | ||||||

| 2.7917 | 0.5195 | 0.0607 | 8.5589 | 0.0000 | 0.4000 | 0.6389 | ||||||

| 3.5794 | 0.6304 | 0.0790 | 7.9784 | 0.0000 | 0.4748 | 0.7859 | ||||||

| T1 Death Anxiety | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0040 | 0.0514 | 0.0300 | 0.0045 | 0.1210 |

| 2.7917 | 0.0671 | 0.0342 | 0.0049 | 0.1382 |

| 3.5794 | 0.0829 | 0.0404 | 0.0076 | 0.1663 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garmendia, P.; Topa, G.; Herrador, T.; Hernández, M. Does Death Anxiety Moderate the Adequacy of Retirement Savings? Empirical Evidence from 40-Plus Clients of Spanish Financial Advisory Firms. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2019, 7, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs7030038

Garmendia P, Topa G, Herrador T, Hernández M. Does Death Anxiety Moderate the Adequacy of Retirement Savings? Empirical Evidence from 40-Plus Clients of Spanish Financial Advisory Firms. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2019; 7(3):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs7030038

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarmendia, Pablo, Gabriela Topa, Teresa Herrador, and Montserrat Hernández. 2019. "Does Death Anxiety Moderate the Adequacy of Retirement Savings? Empirical Evidence from 40-Plus Clients of Spanish Financial Advisory Firms" International Journal of Financial Studies 7, no. 3: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs7030038

APA StyleGarmendia, P., Topa, G., Herrador, T., & Hernández, M. (2019). Does Death Anxiety Moderate the Adequacy of Retirement Savings? Empirical Evidence from 40-Plus Clients of Spanish Financial Advisory Firms. International Journal of Financial Studies, 7(3), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs7030038