1. Introduction

Financial markets are fundamental institutions in any developed economy. They play a crucial role in promoting economic growth by facilitating the channeling of saving decisions into productive investment (

Gerlach and Peng 2005). A major concern for financial institutions is credit risk, because if not managed properly, it can lead to a banking collapse. In this respect, the sub-prime mortgage crisis that started in 2005 in the United States demonstrated the devastating effect that a housing market collapse can have on the real economy. Major financial innovation such as the securitization of subprime mortgages greatly increased the exposure to credit risk of financial institutions. From the late 1990s, there was a sharp increase in sub-prime mortgages fueled by low interest rates and lax lending standards. However, while the quality of banks’ loan portfolios was deteriorating due to the increase in lending to borrowers with little creditworthiness, the default rates remained artificially low due to rapid real estate appreciation. The collapse of the housing market caused a sharp increase in banks’ non-performing real estate loans, followed by a liquidity crisis in the banking system and a financial crisis that spread throughout the world bringing misery to millions of households.

If we are to learn enduring lessons from the sub-prime crisis, we need to understand the relationship between housing finance and credit risk. It is well known that in the decade prior to the recent financial crisis, there was an unprecedented expansion in the use of funded securitization and other methods of transferring credit risk, such as synthetic securitization and credit derivatives. In light of the 50% increase in delinquencies in the U.S. subprime housing market from 2005–2007 (

Stiglitz 2007) and the global financial crisis that followed, it is of crucial importance to shed light on the factors that contribute to potential loan defaults in order to avoid future banking crises.

In the literature, there is a general consensus that factors such as household indebtedness and credit availability, in addition to macroeconomic factors, play an important role in determining credit risk (see for example (

Pesola 2011), among others). However, most related literature focuses on one issue or the other, leaving little insight into how these risk factors interact. One lesson from the sub-prime crisis is that these factors do not act in isolation, but mutually reinforce each other (see

Matheson 2013;

Reinhart and Rogoff 2008;

Minshkin 2011; among others).

Against this background, in this paper we take a broader view of the issue and consider the relationships between housing, housing finance and credit risk. Using panel data from a large number of countries for the period 2001 to 2010, we first consider risk factors related to the demand side of the credit market such as household indebtedness, house prices and housing affordability. We then analyze risk factors related to the credit supply side and investigate how the evolution of financial liberalization and credit market regulations affect credit risk. Particular attention is given to the degree of financial liberalization of a country and the exposure to credit risk in relation to the housing market. The period under consideration is of particular interest as it allows us to include the effects of the recent financial crisis.

With respect to credit market demand, we first examine how factors relating to borrowing, such as housing affordability, affect credit risk by considering the performance of banks’ non-performing loans (

NPL). The questions we address in this article are: Is there a sizable effect of the cost of housing on credit risk? In other words, does a reduction of housing affordability lead to an increase in default rates? Also, the last few decades of economic growth have seen an enormous development in credit markets matched with a sharp increase in housing expenditure and household borrowing (see for example (

Rinaldi and Sanchis-Arellano 2006)). Accordingly, in this paper we investigate whether the increase of household indebtedness in the recent years has affected the exposure to credit risk of financial institutions. Credit risk is a major concern for the stability of the financial system, therefore it is not surprising that many empirical studies have considered this issue. However, most related literature considers the relationship between real estate prices and financial distress by arguing that a decrease in lending standards by financial institutions in good times may be blamed for an increase in credit risk (see for example (

Dell’Ariccia et al. 2012)). It seems to us that house prices are only one side of the coin, since owning or renting a property requires households to be able to afford it. According to

Andrews (

1998), an affordable house is one that costs no more than 30 per cent of the income of the household occupant, implying that buying or renting a house with acceptable standards at a cost should not overburden households’ incomes for each income class. This means that a deterioration of housing affordability due to house price increase may affect borrowers’ ability to pay their obligations, resulting in a higher probability of default. In light of this argument, housing affordability is a legitimate source of concern regarding a bank’s loan performance. Gaining a better understanding of this issue is crucial because in most cases, despite the existence of collateral and the lender’s legal protection, personal bankruptcy is costly for lenders. In this paper, we consider the issue of the relationship between the housing market and credit risk in a broader way using an indicator of housing affordability that includes the cost of renting as well as the cost of owning a property. In doing so, we are able to investigate the effect of housing affordability on credit risk from a larger perspective than most related empirical works.

Another fundamental player in credit risk is household indebtedness. The sharp increase in housing expenditure and household borrowing in many developed countries has raised concerns about a parallel rise in household financial fragility that in turn may affect credit risk. Assuming a high correlation among real estate markets, household vulnerability and credit risk is reasonable in light of the following two considerations. First, loans to real estate markets comprise somewhere between one third and more than half of bank loan portfolios in most developed countries. Second, the prevailing use of properties for collateral-based loans forms an important channel between the two markets. Indeed, the collapse of several banks, the primary activity of which was real estate financing, raises the question of whether the stability of banks is connected to changes in real estate market conditions and suggests the need for more efforts to quantify the actual impact of the real estate markets on the quality of banks’ loan portfolios. Changes in indicators such as “debt to income” ratio or “mortgage to income” ratio are clearly linked with financial problems; an increase in the level of household indebtedness is a sign of an increased proportion of financially constrained households. Therefore, household indebtedness may be used to investigate the relationship between real estate price fluctuations and credit risk.

Coming now to credit supply, there is a wide consensus in the literature that the origin of an increase in indebtedness is related to the deregulation of financial markets that occurred in many countries during the first part of the 1980s (see for example (

Girouard and Blondal 2001)). On the one hand, the deregulation process boosted competition among financial institutions, prompting them to improve their efficiency. On the other hand, market imperfections may affect the risk-taking behavior of financial institutions. In an efficient world, bank lending rates should reflect the true default risk for the underlying assets and bank profitability; therefore a bank’s lending policy should be driven by its risk appetite. This, however, no longer holds when the attitude toward the risk of financial institutions changes over the cycle (see for example (

Hott 2011)), or when a bank faces distorted incentives in taking lending decisions. For instance, disaster myopia, herding behavior, perverse incentives and principal-agent problems may lead to mistakes in the bank credit policy in an expansionary phase. This, combined with the loose regulatory framework under which banks operate, may excessively increase borrower’s debt levels and result in an increase in problematic loans. Thus, in this paper we aim to investigate the relationship between financial market developments, the housing market and credit risk. Accordingly, the questions we address in this work are: Is there evidence that financial liberalization has affected the performance of banks’ loan portfolios? To what extent has the increase of ratio of credit provided to private sector affected the evolution of

NPL? Is it actually the case that the risk appetite of financial institutions changes over the real estate cycle? As a corollary to our investigation we consider the impact of the regulatory system on the risk of banks’ loan portfolios. Credit risk is, by definition, conditional on the regulatory framework under which banks operate. In this paper we distinguish between financial market regulations and the regulatory framework relating to the housing market. With respect to the former, a large body of literature asserts that financial institutes are more driven by risk-taking behavior in a less-regulated financial environment (see for example (

Favara and Imbs 2015)). With respect to the latter, regulations on property markets may constitute a legal impediment to collateral enforcement, therefore affecting the risk of loan portfolios. Finally, since different countries have different patterns of financial developments over time as well as different regulatory frameworks, after having estimated a number of dynamic panel models, we turn our attention to country idiosyncratic effects. By conducting an analysis by quantile, we are able to discriminate the impact of the risk factors by groups of countries in relation to their risk profile.

The main findings of this paper can be summarized as follows. In general, the recent rise of debt ratios in relation to the housing market has put the banking sector in a riskier financial position. Our analysis reveals that a greater household debt burden translates into a higher probability of credit default. Similarly, the deterioration in housing affordability associated with increased deregulation poses a severe risk to the financial system. In particular, it is found that countries which score high in terms of financial liberalization and low on the level of regulations also experience greater credit risk.

The outline of the paper is as follows.

Section 2 provides some theoretical background.

Section 3 introduces the models under consideration and the estimation procedure used in the empirical analysis.

Section 4 reports the estimation results of the main empirical analysis.

Section 5 provides some further analysis on the effects of financial liberalization and regulation on credit risk, and finally,

Section 6 concludes.

4. Data and Empirical Results

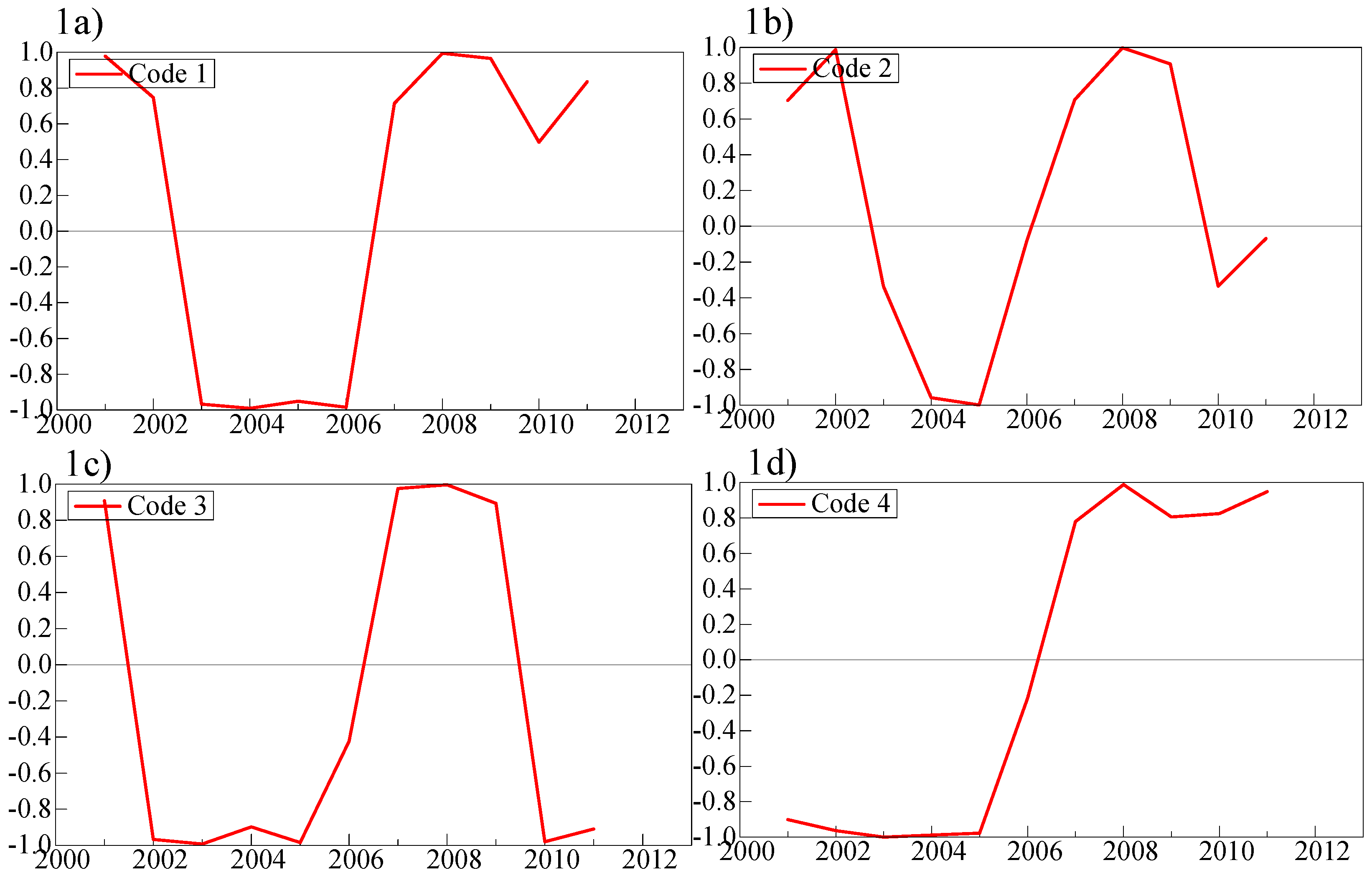

For the empirical investigation, we used a balanced panel dataset of 23 countries over the period of 2000–2012. The sample includes countries that suffered major housing market contractions during the recent financial crisis, but also reflects a broad spectrum of financial development patterns, heterogenous levels of financial vulnerability and different housing market structures. The countries included in the sample are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, the United States and the United Kingdom.

Our balanced panel data were compiled from several sources. The World Development Indicators from the UK Data Service (UKDS) and the Financial Soundness Indicators from the IMF and World Bank supply data of the NPL ratio on annual frequency, but for different time periods. Therefore, the data were retrieved primarily from the UKDS and extended from the other two sources. The probable differences in methodology between the three sources were accounted for by matching values of NPL over the overlapping periods. Real residential property prices were obtained from different national statistical offices. Data for real interest rates, ratio of household debt to disposable income, consumption to disposable income and housing affordability were accessed from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Finally, data on financial liberalization were obtained from the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World database.

Table 1 reports the variables with the expected signs and reports the descriptive statistics. Before presenting the models below, we briefly summarize the expected signs of the different risk factors included in the empirical estimation.

4.1. Dynamic Panel Data Estimations

4.1.1. Models with Household Credit Risk Factors

Table 2 reports the estimated coefficients of Equation (1) along with statistical significance. For ease of interpretation asterisks, indicate the level of statistical significance of the estimated coefficients. Robust standard errors are reported in parenthesis.

Turning to the results, column 1 in

Table 2, reports the estimated parameters of a baseline model, referred to as Model 1. This model with only macroeconomic fundamentals is used as a benchmark; then the other risk factors in Equation (1) were added sequentially and the estimation results reported in columns (3)–(5). Starting with

, the coefficient of the lagged dependent variable was highly significant, thus suggesting high persistence in

NPL growth ratios. Also, the implication of the negative sign for the estimated coefficient of

is that the

NPL growth decreases when high ratios of

NPL are observed in the previous year. This result may be attributed to write-offs. From

Table 2 it appears that

and

show high statistical significance and carry a negative sign. This finding indicates that an increase in

contributes to a decrease in

NPL growth ratio, implying that an economy that is enjoying a stable rate of growth also increases a borrower’s ability to service their debts. Looking now at

and

, the estimated coefficients carry a positive sign and are statistically significant, thus indicating a positive association between

NPL and unemployment rate. The explanation of positive relationship relies on the fact that an increase in the unemployment rate negatively impacts borrowers’ income and undermines their ability to pay back their contracted debts, or at least may provide an incentive to terminate their payments. From

Table 2 it appears that

is significant (although at 10%) and carries the correct sign. An increase of interest rate is likely to increase impaired loans by forcing borrowers to incur higher costs on the debts. This is turn might encourage them to default if these costs become unaffordable. Overall, the results in Model 1 are consistent with the consensus in the literature, which suggests that the contractionary phases of the business cycle are often accompanied by a greater credit risk (see

Louzis et al. 2012; or

Salas and Saurina 2002).

Considering now Model 2, the estimated coefficients

and

are significantly different from zero and carry a negative sign. The estimated sign suggests that the collateral value hypothesis (see

Daglish 2009) held for the data at hand. As seen in

Section 2, the collateral value theory argues that rising house prices reduces the credit risk of the banks’ loan portfolios by increasing the value of the houses owned by financial institutions and the value of the collateral pledged by borrowers. Thus, it suggests a negative relationship between house price changes and bank

NPL. Note that, the covariate

has been dropped from this and the remaining models as it was found to be not significantly different from zero.

In Model 3, the estimated coefficient for the covariates

and

was statistically significant and carried positive and negative signs for the contemporaneous and lagged estimated coefficients, respectively. These findings are in line with the theoretical model in

Lawrance (

1995), briefly mentioned in

Section 2, and confirm that liquidity constraints can explain the default decisions of consumers (see also

Rinaldi and Sanchis-Arellano 2006). In particular, the results indicate that high household indebtedness burdens borrowers and undermines their ability to settle their scheduled obligations in the short term. Indeed, the greater the household indebtedness burden, the higher the default probability due to potential difficulty in fulfilling their committed debts. Consequently, banks’ loan portfolios are more likely to witness a higher volume of

NPL growth. This can explain the positive sign of both

and

. However, over time, greater household indebtedness might warn lenders of the higher level of fragility of their borrowers and prompt more cautious lending standards to mitigate risky loans by adopting tighter lending terms on loans to households with high debts. Consequently, more constrained access to loans helps to reduce the amount of

NPL. This explains the negative sign for the estimated coefficient of

and

. The implication of these results is that financial institutions take time to react to borrowers’ negative financial shocks.

Turning now to Model 4, from

Table 2 it appears that the estimated coefficient for

is statistically significant with a negative sign, whereas the lagged coefficient has negative sign. Therefore, an increase in housing affordability was found to reduce credit risk. In principle, housing becomes more affordable when either house prices (or rents) decrease or incomes increase; either case improves households’ debt servicing ability, therefore reducing the credit risk. The positive sign of the estimated coefficient for

may be explained by theoretical models that suggest myopic behavior of banks or other types of irrational expectation models (see

Hott 2011). According to this literature, when default rates on loans decrease, financial institutions are more optimistic about the creditworthiness of their customers. This leads to higher loan approval, which in turn leads to higher real estate prices and, according to the collateral value hypothesis, to lower default rates. However, when the rate of change of house prices gets too small to justify the high real estate price level, default rates start to increase again. Now the process is reversed and banks change their expectations, becoming more pessimistic about the risk to their loan portfolios. As a result, lending institutions impose tighter conditions on loans for households, pushing house prices down and leading to a higher volume of negative equity held by banks, which in turn causes higher

NPL growth ratios. Similarly to the impact of household vulnerability, this implies that lenders take time to recognize the decline in housing affordability and adjust their lending policy by tightening lending terms to households with fragile financial health.

4.1.2. Models with Credit Supply Risk Factors

Moving to the estimation of Equation (2), Model 1 in

Table 3 reports the estimated coefficients for the benchmark model as well as the proxy variables for financial developments. Note that the house price variable has been added to the baseline model. This is because sharp cyclical variations in real estate prices are expected to increase credit risk. Omitting this covariate from the model estimation procedure would induce an omitted-variable problem, leading to estimators that are biased. From Model 1, it appears that financial developments and banks’ lending behavior have an important effect on the performance of loan portfolios, as the estimated coefficients of the proxy for financial developments are highly significant. However, the estimated coefficients of this covariate have a negative sign in the contemporaneous effect and a positive sign in the lagged effect. The implication of the positive sign for

is that the transmission mechanism of an increase in loans and mortgages on

NPL is quite slow as it is binding only over time. Given the fact that mortgage contracts are usually issued over a long term, the negative consequences of excessive mortgage lending are supposed to appear with time delay. Note that the indicator for financial developments is a composite measure that includes the ratio of mortgages to GDP. This ensures that the proxy for financial liberalization takes into consideration the developments in the housing finance market.

All in all, the positive estimated coefficient of

supports the “competition-fragility” hypothesis rather than the “competition-stability” hypothesis (see

Section 2) thus suggesting that higher bank competition following liberalization increases banks’ opportunities to take risks.

Coming now to Model 2 in

Table 3, the estimated coefficients for

CRM are statistically significant and carry a negative sign, demonstrating that underregulated financial systems are more prone to credit risk and banking sector instability. Similarly, the estimated signs for

RPS are negative and significant. This result suggests that the regulatory frameworks relating the real estate market influence the banks’ ability to reduce

NPL. This may be due to the fact that legal or judicial impediments to collateral enforcement may influence a bank’s ability to commence legal proceedings against borrowers or to receive assets in payment of debt and might also affect collateral execution costs in loan loss provisioning estimations.

In Model 3, we investigate the joint effect of credit market regulations and restrictions on property sales on the growth of impaired loans by augmenting Model 2 with the interaction variable denoted as

. Similarly, Model 4 investigates the joint effect of credit market regulations and financial developments on

NPL by constructing another interaction variable that captures the joint effect of the two risk factors. This is denoted as

. From

Table 3 it appears that in both Model 3 and 4 the estimated coefficients are highly statistically significant, with a dominance of negative signs. The negative estimated signs in Model 3 indicate that imposing tighter regulations contributes to lower ratios of bad loans in the banks’ loan portfolios, and hence more sustainable banking performance and financial system. Similarly, the negative estimated signs in Model 4 indicate that market liberalization can happen without an increase in credit risk provided that the credit markets are highly regulated. More importantly, the estimation outcomes of the last two models have important policy implications, suggesting that financial development policies, credit markets and housing market regulations do not have to offset each other. In contrast, each policy may overcome the shortcomings of the other. Therefore, our findings suggest that the regulation of financial markets and real estate markets should be designed in a wider policy framework, with tight cooperation between policymakers in the real estate market and the banking industry, in order to ensure a sustainable and sound banking system.

The bottom panel of

Table 2 and

Table 3 report the model specification tests discussed in

Section 3. The results show that all the estimated GMM models pass the misspecification tests as the null hypothesis AR(1) test is rejected (although at 10%) and the AR(2) null hypothesis in not rejected. Furthermore, the null hypotheses of the Hansen test and the Sargan test for the joint validity of the instrument set and overidentification restrictions are not rejected, confirming that the instruments are exogenous and not correlated with the error term. Overall, the misspecification tests in

Table 2 and

Table 3 support to the validity of the instruments used in the estimation and suggest that the models are well specified.

Summarizing the results above, our analysis indicates that credit market developments can be important in explaining credit risk. In particular, larger credit availability due to increased credit supply can lead to an increase in external financial resources and hence to an increase in current consumption and greater level of household indebtedness. A higher debt ratio in turn amplifies the impact of macroeconomic shocks on household balance sheets and affects their ability of debt servicing. Since the large increase of debt can be attributed to an increase in mortgage finance in the context of dynamic housing markets, such amplifying effects can also emerge as a result of pronounced changes in house prices via the increase in the value of collateral. In this context, a higher level of debt implies a greater risk that households will face problems in servicing their debt and as a result a higher non-performing ratio. Our estimation results suggest that market regulations also play an important role in determining credit risk.

6. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we investigated the determinants of non-performing loans. Particular attention was given to the housing markets and the effects of housing affordability on credit risk. Given the expansion of credit to the private sector in most developed countries, the effect of household indebtedness was also considered. Finally, the characteristic of the financial systems and regulations in which financial institutions operate were included in the analysis.

In line with the literature (see for example (

Louzis et al. 2012;

Salas and Saurina 2002)), it was found that macroeconomic conditions have a non-negligible impact on credit risk. The quality of lending for households varies inversely with

GDP and house prices, and positively with the unemployment rate and interest rate. Evidence from analyzing a large panel of data also suggest that household affordability is positively correlated with credit risk. Similarly, an increase in household indebtedness positively effects credit risk.

From our analysis, it emerged that loose credit market regulations and restrictions to property markets play an important role in the determination the risk of loan portfolios. It was found that financial institutions in countries that are at the bottom quantile in terms of credit market liberalization and in the top quantile in terms of property market regulations,

ceteris paribus, also experience lower credit risk. This result corroborates the findings of several empirical works. For example,

Dell’Ariccia et al. (

2012) found that innovations such as mortgage securitization contributed to a deterioration in underwriting standards in countries such as the United States in the recent financial crisis, whereas covered bonds contributed to safer mortgages in Europe.

Our findings have several implications in terms of financial regulations and housing policy. Specifically, there is evidence that household financial fragility interacts with the regulations in which financial institutions operate via the credit channel. Widespread imperfections in the credit market, such as asymmetric information or imperfect contract enforceability, result in suboptimal credit policy. In turn, the credit channel affects financial stability and the wider economy. This suggests that regulatory authorities should closely monitor the mortgage market and enforce the measure of risk management on financial institutions. Relying on banks’ voluntary efforts to manage bad loans may not be enough. Regulatory authorities may want to guide banks as to the optimal use of their capital buffers and determine target loan loss provisions. On their side, financial institutions may review the range of risk strategies available and their respective financial impact. In this respect, stress testing exercises may be used to evaluate the risk exposure of bank’s portfolio to macroeconomic conditions.

Another implication of our empirical study is that housing finance systems deeply affect household financial fragility, and therefore credit risk. In this respect, regulators may impose lower loan-to-value (LTV) ceilings to mitigate the impact of the financial accelerator mechanism by reducing the transmission from increases in income to increases in house prices. A growing literature shows that the LTV policy is a promising road to greater financial stability (see for example (

Crowe et al. 2011; or

Claessens et al. 2012)).