1. Introduction

The inspiration for this investigation started with the perception that an organization’s financial managers, regulatory authorities, investors, and speculators are concerned by credit ratings when making their investment and financing choices. An ideal capital structure is the best proportion of debt and equity of a firm that augments its value. The optimal capital structure of an organization is one that reduces the relative cost of capital by establishing a harmony between the perfect debt-to-equity ratio. Debt financing normally offers the smallest cost of capital because of its tax shield benefits. Deciding an ideal capital structure is a central necessity of any company’s corporate fund division. A couple of years ago organizations in Europe, Asia and around the globe altogether reinforced their capital structure by deleveraging and reducing liquidity risk due to the financial crisis (

Frank and Goyal 2003). Today, various outside variables including credit ratings and macroeconomic elements exist as impetuses for a correction of the financing and speculation choices of European, Asian and worldwide firms. The economy is gradually recuperating, credit spreads are still at verifiable lows, and organization balance sheets have been rebuilt. Firms are concentrating on refinancing risk by increasing cash flows to maintain a strategic distance from future emergencies and expanding securities exchange valuations. All these changes have increased the need for the credit rating to measure financial constraints.

The first formal theoretical, as well as an empirical study (

Kisgen 2006), maintained the implications of the model that determined the link between credit ratings and capital structure of the firm. The researcher developed a strong hypothesis, i.e., the “credit rating capital structure hypothesis (CR-CS)”. The hypothesis stated that credit ratings are related to the managerial decision for capital structure since CRs are linked to discrete costs (benefits) with different levels of ratings. The CR-CS hypothesis followed by empirical evidence (

Kisgen 2009) identified that credit rating decisions must not be considered useful only for a proxy of default to measure capital structure. Rather, they should be considered for attaining important information for discrete costs and benefits that are influential for the cost of capital of a company.

There are a growing number of empirical studies that scrutinize the effects of credit rating changes on the decisions of capital structure (

Naeem 2012;

Matthies 2013;

Wojewodzki et al. 2017). Credit rating agencies have access to various types of information, such as the business plan of firms, capital expenditure, and the dividend policy designed for future that is not provided to investors, etc. Therefore, credit ratings also help to reduce information asymmetry in the financial markets. Furthermore, bank regulation, insurance companies and broker’s investment in bonds are the main drivers for determining a firm’s rating in the bond market (

Duff and Einig 2009;

Gul and Goodwin 2010;

Chen et al. 2013). The interesting factor in these studies is the complete alleviation of the postulation that there could be differences in the capital structure of a firm due to rating levels. However, the rating level differences and leverage level variations can be explored in a detailed argument. To be specific, low-rated firms are more likely to have a low debt ratio because of having a low credit rating. Such firms establish even a higher cost of debt and more agreements in debt contracts. Another researcher (

Diamond 1991) also developed the argument that borrowers having low credit rating would have a high cost of capital when compared with highly rated firms.

Naeem (

2012) presents empirical findings that a low-rated firm can have some restricted agreements due to its incapable financial strength being shown in low ratings. Researchers have analytically proved that investors are also interested in credit ratings, as these ratings contained additional information, which can serve as a signal to the financial health of firms. Despite being the best-qualified group with respect to creditworthiness, many companies are not publicly rated. Still, financial intermediaries and investors can still allocate funds to these companies due to their internal credit risk assessment processes (

De Haan 2017).

Studies from numerous surveys revealed that in order to undertake financing decisions, CFOs of listed and privately-held companies consider credit ratings highly relevant, and this holds particularly for debt-based financing choices (

Graham and Harvey 1999;

Boot et al. 2006). This literature strand has been extended by various features such as the relationship between capital structure decisions and credit rating (

Naeem 2012;

Ntswane 2014;

Kedia et al. 2017), the relationship between ratings and the probability of default, rating transitions, bank internal credit rating systems, and numerous methodological approaches (

Anjum 2012;

Stepanyan 2014;

Angilella and Mazzù 2015;

Sanesh 2016).

The information caught by credit rating assessments can be recognized in corporate financing behavior in a few courses, e.g., through the level of credit ratings, changes in credit ratings or extra information related to ratings such as rating outlook or watch status. Moreover, the degree to which credit rating assessments influences capital structure choices can be evaluated directly or inserted into conventional capital structure theories (

Duff and Einig 2009;

Kisgen and Strahan 2010;

Wojewodzki et al. 2017).

The above-mentioned literature review shows that the focus is two-fold: in the first stream, the focus was on the importance of rating changes, which stated that organizations whose ratings are getting worse generally decrease their leverage. Inversely, firms with (possible) upgraded ratings generally choose to increase their debts due to the low cost of capital and better access to external financing.

However, in the second stream, credit assessments are categorized into investment and speculative grade. Firms in an investment-grade category receive benefits by bringing down the cost of capital due to high ratings. Firms in the speculative-grade category have a generally low level of leverage due to the high cost of debts (

Cantor 2004;

Bolton et al. 2012).

There are just a few examinations that question the importance of credit rating levels for capital structure choices. The relationship between credit rating and the financial constraint is also very important. The sole presence of credit ratings facilitates the access to outside financing. Besides, high credit ratings are required for many financial instruments, e.g., commercial papers. The cost of external financing significantly decreases with higher credit ratings due to the exponential distribution of probabilities of default with respect to different rating categories. Therefore, for optimal capital structure decision, credit rating is an important measure to be considered.

Past studies and examinations characterize firms as per the rated/non-rated or the investment grade/speculative grade criteria. They do not consider the ordinal idea of ratings or appraisals and, thus, do not categorize firms as indicated by various rating levels inside the investment and speculative grade criteria. Hence, some data might not be caught. Generally, past studies apply credit ratings to monetary instruments, e.g., bonds or commercial papers. These ratings may not represent the real reliability of the issuers (firms) of these financial instruments.

Previous literature has emphasized the relevance of credit ratings and capital structure in the US and European markets. The Asian market has not been considered much by previous researchers, which creates a gap in information collection. However, it is adequately demonstrated by a few researchers that the Asian market has a role in various monetary and regulatory changes in the capital markets of the region.

Therefore, this study is focused on analyzing the above-stated limitations of previous studies and efforts to scrutinize the effect of the corporate credit rating scale for capital structure optimization. Non-financial listed Asian corporations are selected throughout the period of 2000–2016. This study focuses on the most important Asian markets such as China, Japan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, India, Thailand, and Indonesia. From the last 20 years, the high speed of growth observed within these Asian financial sectors plays a crucial role in the development of those countries.

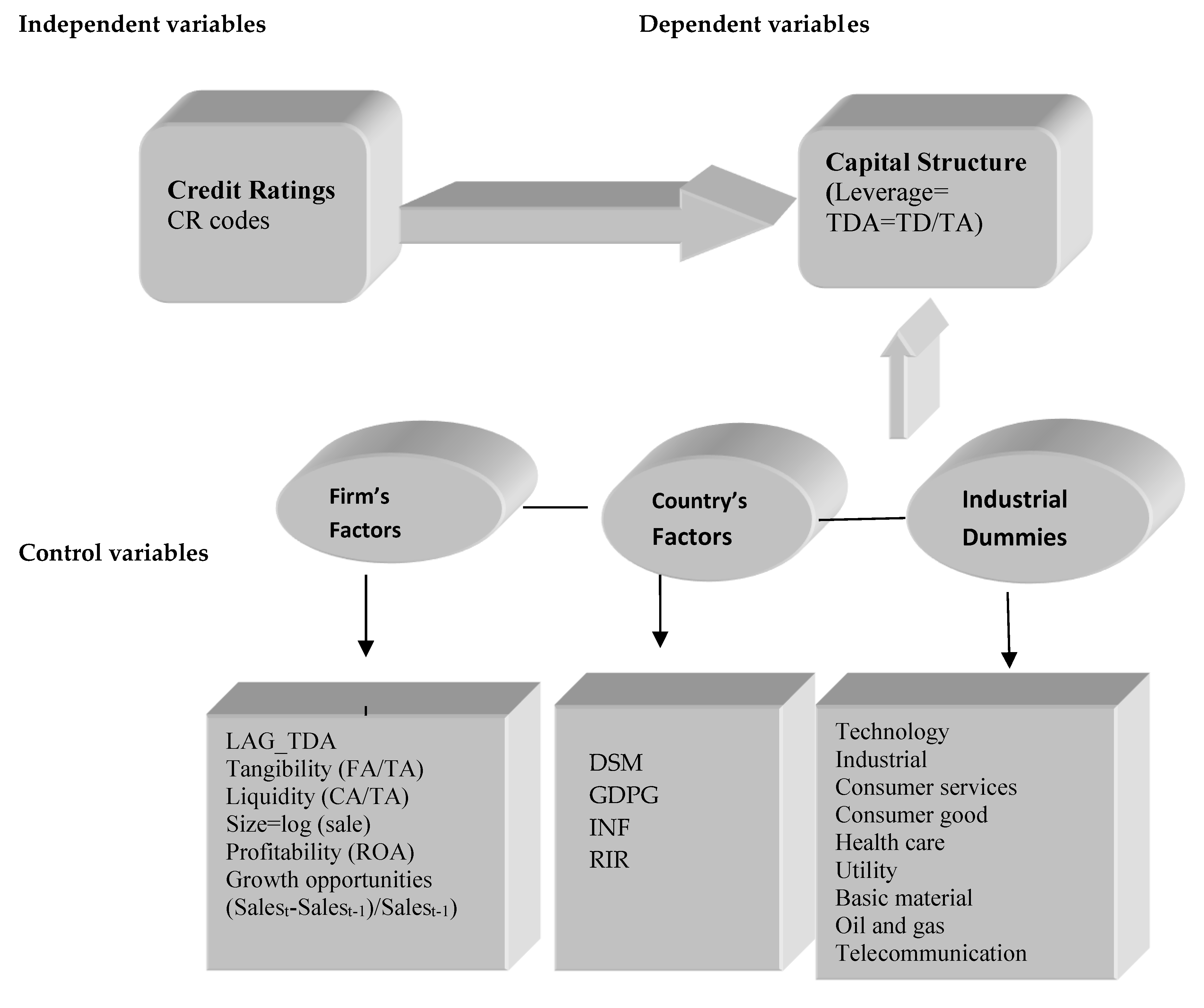

In this paper, we propose a theoretical framework for ideal capital structures considering the costs and benefits of each rating scale. Credit rating is a measure of financial constraint, particularly liquidity risk, and the productivity of firms to create more funds. First, we draw a connection between the corporate credit rating level and the amount of leverage. Next, we inspect the effect of various corporate factors and industry dummies on capital structure–credit rating association. Furthermore, macroeconomic rudiments are equally utilized as a catalyst to measure the genuine relationship of credit rating scales and optimal capital structure.

The key research question is: does a relationship exist between rating levels and optimal capital structure in Asian firms?

To inspect the research question of the study, the following hypothesis is defined:

H1. With other elements considered equal, it is expected that there is a non-monotonous inverted u-shaped relationship between credit rating scales and level of leverage.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The complete, descriptive statistics of the variables are conferred in this section together with the graphical presentation of the debt ratios of Asian corporations. In descriptive statistics, the focus is on the leverage ratio and credit ratings, as they are the main variables of interest of the study.

Table 2 shows that average leverage ratio is 25% in Asian companies, meaning that Asian companies avoided a large number of debts in their capital structure. The standard deviation of leverage is 0.177, which shows considerable variation in the sample. Growth opportunities (

GROPE) and the domestic stock market (

DSM) show huge variation, which can be due to companies from different developed and developing markets, such as Japan, China, India, Malaysia, etc.

Figure 2 shows the mean leverage ratios of Asian corporations during the sample years. It can be clearly seen that the average leverage ratio (

TDA) is comparatively reliable throughout the sample period with slight changes from year to year. From 2000 to 2003 the mean leverage ratio rose throughout the start of the sample years and remained at the 25th percentile (25%) until 2003. One of the reasons for the primary changes is often the decline in the inflation or interest rates throughout those years.

Another argument for marginally expanded statistics in the initial three years of the sample period might be the sample of companies from eight totally different economies. After 2004, there was a little decrease, however, the quantitative proportion stays stable for the succeeding four years (2004–2007). Mean TDA proportion is 21–28%. The most extreme adjustment in the leverage is one percentage point; from year to year that does not propose any primary deviation over the sample years.

Credit ratings and average leverage ratio are shown in

Table 3. The firms with top credit rating show lower average debt ratio. Moreover, the amendment in mean leverage ratio relies on the scale of credit rating. As shown in

Table 3, average debt ratio is 0.095 at AA+ and at every credit rating level, mean debt ratio changes; however, there are minor changes to the AA+–A+ group, the variation within the average debt ratio rising by 14% points, so more variation is 18% and 20% points to the BBB class and BB+. From BB+ (speculative grade), the average leverage begins to decrease. Therefore, the standard deviation of the speed of borrowing for firms at the primary level is incredibly low, which suggests that these firms not only need to maintain a low level of leverage but also must take care of the level of highest credit rating. As the credit rating decreases, especially for mid-rated companies, the debt ratio increases steadily. At the same time, the standard deviation is also increasing, which suggests that firms have an additional dispersion compared to the high-rated corporations in their capital structure.

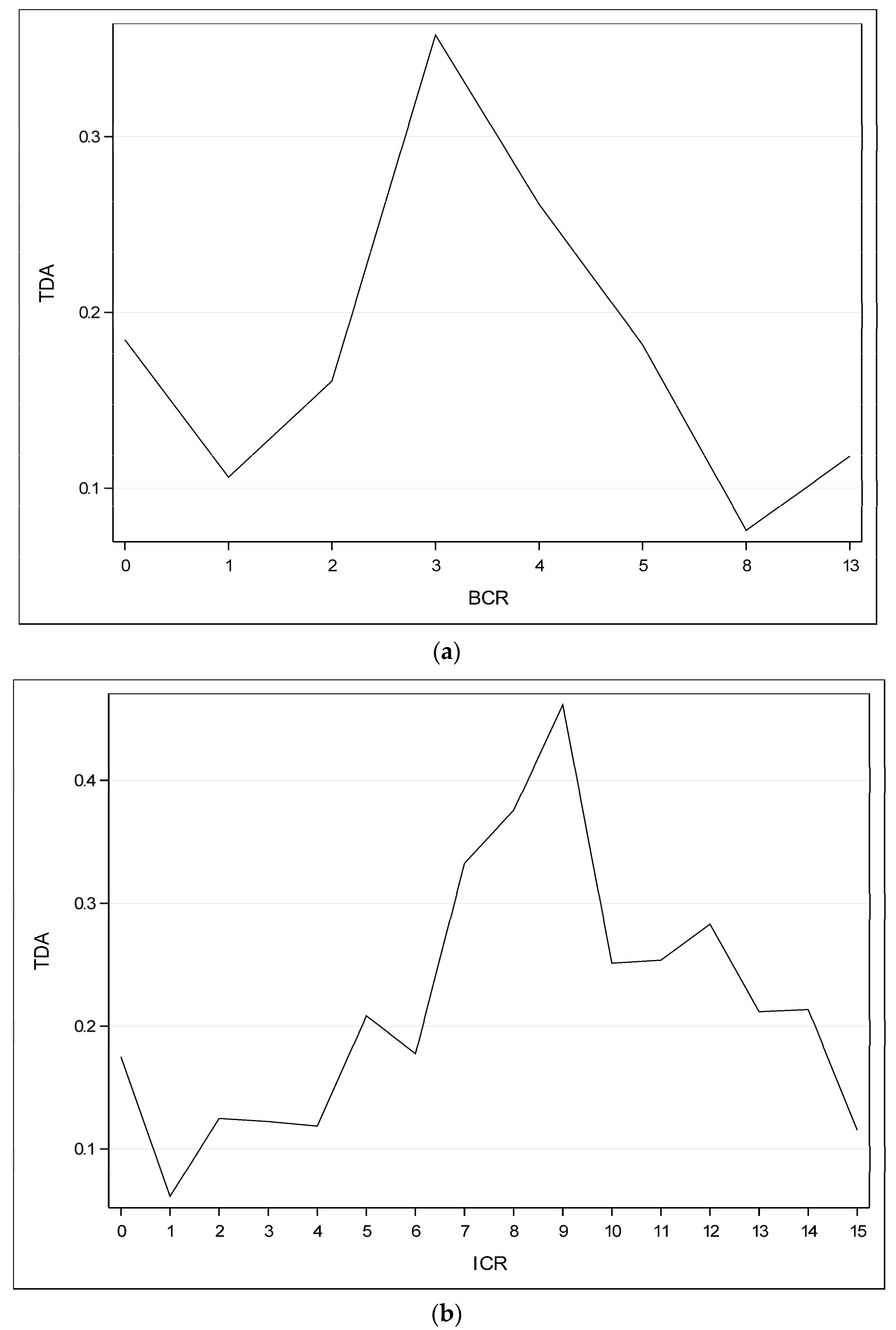

A graphical illustration of leverage ratios with reference to broad and individual credit ratings is presented in

Figure 3a,b.

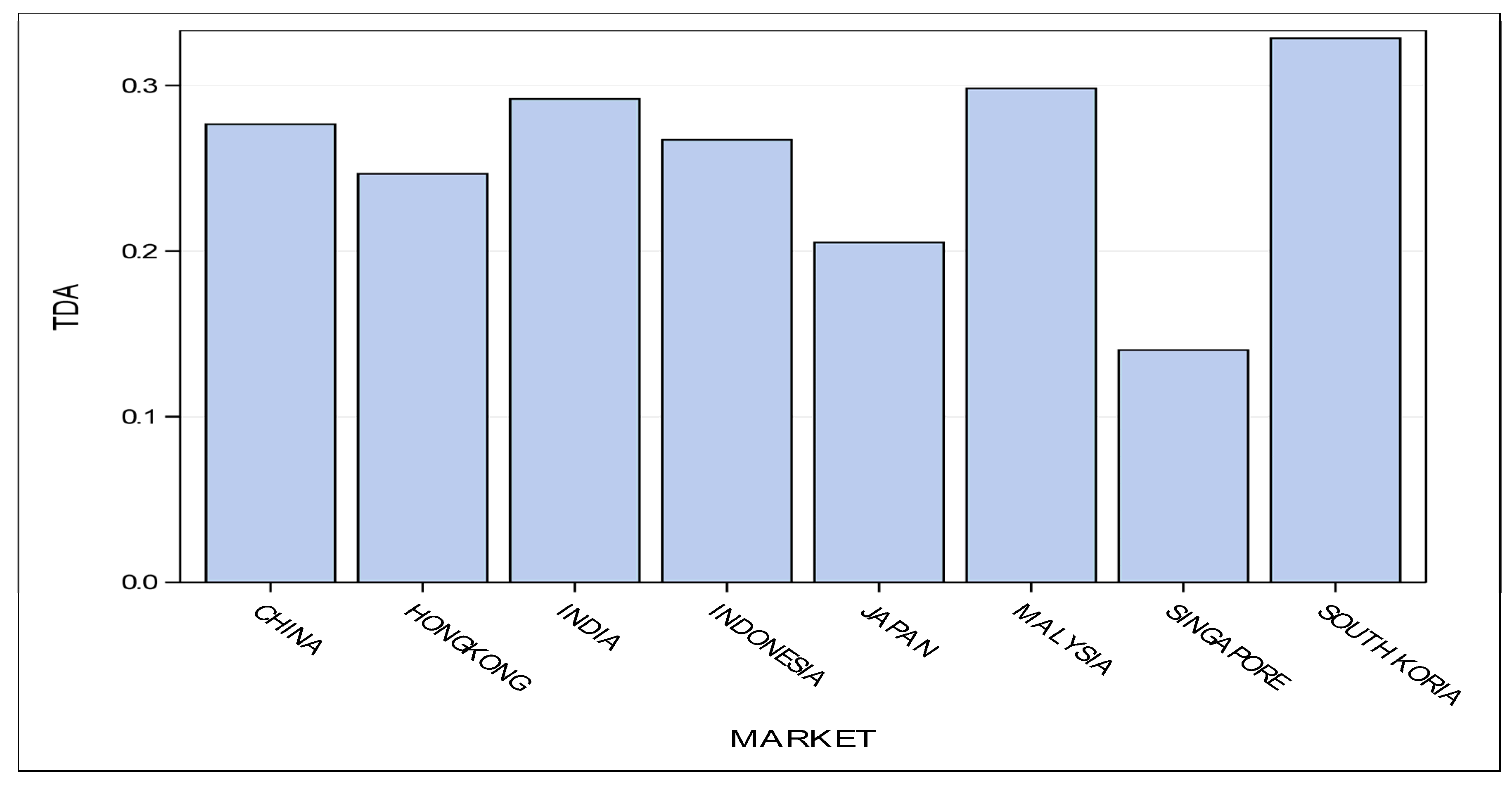

Figure 4 is a bar chart that presents the mean leverage ratios of the Asian companies with reference to the Asian market over the sample years.

In

Figure 3a,b, there is clearly a non-monotonic, inverted U-shaped pattern of leverage ratio with reference to the credit ratings. It is evident that corporations with low rating scales have a low level of gearing ratio compared with any medium-rated corporation. It indicates that these corporations have restrictive entry into debt markets compared to medium-rated corporations, or such corporations must be compelled to face the high price of debt because of lower credit ratings. Intermediate-rated corporations have a high level of leverage because they enjoyed the low price of debt. High- or top-rated companies have an additional low level of leverage that indicates the preference of the high-rated firm is to take advantage of the high level of credit ratings to grasp additional edges into the money and capital markets. Furthermore, to have a low level of leverage in highest-rated corporations indicates alternative motives for getting highest credit ratings, apart from when entering into debt markets.

Moreover, corporations of Singapore, Japan, and Hong Kong show low leverage ratios as compared to alternative Asian markets in the capital structure of firms. Corporations of South Korea show the highest leverage in their capital structure (see

Figure 4).

3.2. Pooled OLS Fixed Effect and GMM

This section presents the pooled OLS, fixed effect, and GMM results. Column 1 in

Table 4 is the name of variables. Column 2 presents the results of pooled OLS. Column 3 presents the results of fixed effect model. Column 4 shows the result of GMM model, and column 5 presents the heteroskedasticity white consistent variance for best model fit.

Column 2 shows that R2 is 75%. All variables jointly explain 75% of the variation within the capital structure of rated companies by pooled OLS. The estimate 0.0194 of ICR is positively and significantly related to leverage. However, the estimate −0.0014 of ICR2 is negatively and significantly related to leverage. It indicates a non-linear inverted U-shaped association between the credit ratings and leverage ratio of Asian companies.

After employing the fixed-effect model (FE), R2 increased from 75 to 82%. Findings show that all variables explain 82% variation in capital structure decision. R2 in the fixed effect (FE) model is improved. Each credit rating scale (ICR) shows a positive and significant relationship with a leverage ratio and each rating square (ICR2) shows a negative and significant effect on capital structure. T-values have also increased under the fixed effect model as compared to pooled OLS.

After utilizing heteroskedasticity white consistent variance, R2 increased from 75 to 76% in OLS regression. Credit rating scales show a significant and positive impact on capital structure decision and credit rating square shows a negative and significant relationship with leverage ratio. T-value decreased for ICR and ICR2 after employing HWC variance.

Column 4 in

Table 4 presents the results of GMM. The number of the cross-section is 137; time-series length is 17 years.

GROPE and

DSM are used as instruments. The Sargan test statistic 43.13 (PR = 0.423) shows that the selected instrumental variables are valid and does not show any over-identification problem. Findings from GMM2 show high coefficient values of

ICR = 0.08866 and

ICR2 = −0.0048 as compared to the results of other estimation techniques. Evidence also shows that each credit rating scale (

ICR) has a positive and significant influence on the capital structure and

ICR2 also shows negative and significant associations with capital structure.

It is evident from all econometric models that each credit rating scale shows a substantial effect on the capital structure decision of Asian companies. If companies are concerned about each rating scale, their behavior toward capital structure decision will be correlated. All models confirm the non-linear inverted U-shaped pattern between credit ratings and capital structure decision.

The non-linear association between the credit rating and capital structure of firms shows that previous studies by

Faulkender and Petersen (

2006), and by

Bancel and Mittoo (

2004) cannot completely explore the advanced association of credit ratings and capital structure of firms. As an example, they empirically proved a negative association of credit ratings with gearing, and they both notice that low-rated companies have high leverage ratios. However, contradictorily with previous studies, the results of the current study recommend that, as with high rated firms, lowest-rated companies even have comparatively low degrees of leverage. Low-rated companies apparently have a greater problem with the expenses implemented by their exacerbated credit ratings. Rating reductions can have comparatively much more serious results on low-rated companies than on top-rated and medium-rated companies. The result shows that low-rated firms favor the low leverage ratio. Another reason may be due to the less developed bond market in Asia.

The institutional and regulative settings of major Asian markets may raise the issues over low ratings e.g., Singapore, Korea, and Malaysia. This kind of finding conflicts with

Lemmon et al. (

2008) and

Al-Najjar and Elgammal (

2013), who contend that the rating organizations, regardless of investment grade or in speculative-grade, can have higher access to the debt market and have high amounts of leverage.

High credit rating firms arguably have easier access to the financial market, low cost of capital, favorable conditions in the money market, favorable debt contracts, and access to alternate sources of funding. High-rated firms can even relish the non-financial benefits e.g., reasonable management control in the labor market, worker commitment, and strong client and supplier relationships. Given that highly rated companies, throughout the time of crisis, have gained credibility for being productive and extremely reliable companies, they must maintain their credit rating high as compared to other rated companies.

It ought to be considered that the inclusion of credit ratings in capital structure determinants dissent from ancient trade-off theory. The trade-off theory, which predicts a negative connection between risk and debts, communicated that best credit-rated firms have low probabilities of default, and have high debts. However, the consideration of credit rating costs and benefits are distinct from trade-off theory and proposes that the concern for high-rated benefits will lead toward the low level of leverage in the top-rated companies.

Companies with intermediate credit rating level show sturdy support toward high leverage ratios. This is possible because these firms have higher credit rating levels than low-rated firms; they need less restriction to enter the debt market than low-rated companies. Additionally, middle-rated firms show that they are stable firms with a low probability of default. Overall, the results of this study advocate and confirm the hypothesis that credit ratings have non-monotonic and inverted U-shaped relationship with the capital structures of corporations.

Other proxy measures, including lag of dependent variable, show positive and highly significant association with capital structure decision by all econometric estimations. It is evident that high leverage in previous years can increase leverage in capital structure decisions. Tangibility (TANG) shows negative and significant associations with the leverage ratio. Pooled OLS results show that tangibility is less significant and after employing heteroskedastic consistent variance, tangibility shows an insignificant relationship with leverage. GMM results also show that tangibility is insignificantly related to leverage ratio. Liquidity (LQDT) shows the negative and significant impact on leverage ratio by all econometric estimations. It is evident that high liquidity leads to low level of leverage. Companies prefer low debts when they are highly liquid. Profitability (ROA) shows a negative and significant relationship with leverage ratio in the results of all estimation techniques. It indicates that Asian firms follow a pecking order theory in their capital structure decision. Size (SIZ) shows a significant and positive relationship with leverage ratio in the GMM model and in OLS after utilizing heteroskedastic consistent variance. Pooled OLS and fixed-effect results reveal that size is insignificantly related to leverage ratio. Growth opportunities in the present study show a constant or no relationship with the leverage ratio of Asian companies. This could be due to the different companies from different markets and institutional settings where growth opportunities can fluctuate.

In the present study industrial dummies, including basic material and consumer goods, show a weak significant relationship with leverage in OLS. Meanwhile, utility shows a significant relationship in the fixed effect model and after correcting the heteroskedastic issue in OLS respectively. All other industry dummies show an insignificant relationship with leverage by all econometric estimations.

Gross domestic product (GDP) demonstrates an insignificant association with leverage or capital structure, which can be due to various GDP rates in several countries; organizations in each country behave according to their own environment. The domestic stock market (DSM) demonstrates a negative and significant relationship with leverage in the fixed effect model. Inflation (INF) shows a weak relationship with leverage in the GMM model. Real interest rate (RIR) shows a constant insignificant relationship with leverage in all econometric estimations.

Generally, the results of the present examination give strong support to acknowledge the proposed hypothesis, that the importance of credit ratings costs and benefits create a non-linear inverted U-shaped pattern between credit ratings and capital structures of Asian firms. With respect to the determinants proposed by conventional theories for capital structure, credit ratings appear to have a higher explanatory power for establishing the optimal capital structure of firms. The findings of the control variables reveal that rated organizations can have an alternate capital composition but similar firm factors and country factors.