Abstract

Starting in June 2014, the European Central Bank (ECB) stepped up its monetary accommodation in order to counter a too prolonged period of low inflation in the euro area. This article offers a narrative of the monetary policy measures taken up to December 2016 and a review of the effects of ultra-low interest rates. The exceptional monetary stimulus transmitted to the economy broadly as intended. Moreover, it enhanced the financial capacity of economic agents to bear risks. At the same time, the ECB and the European micro- and macro-prudential authorities remained watchful of the unintended side-effects of an extended period of very low or negative interest rates for financial intermediation, financial stability and market discipline and took preventive or corrective measures as appropriate. A joint plan of action carried out by the 19 member countries with the aim to speed up balance sheet repair, accelerate the economic recovery and achieve higher productivity growth could have contributed to a more effective euro area macroeconomic and financial policy mix.

JEL Classification:

E31; E5; G1; G2

1. Introduction

Market interest rates in all advanced economies have fallen to record-low levels in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008 affected by a variety of both global and domestic factors, including monetary policy. This article offers a narrative of the conduct and consequences of ECB monetary policy from June 2014 to December 2016 as the euro area crisis had subsided, but a prolonged period of low inflation put medium-term price stability at risk.1 The ECB responded to this new challenge with a substantial additional monetary stimulus using both standard and non-standard measures. These included reducing policy rates to levels around the zero lower bound, targeted longer term refinancing operations for banks and large-scale asset purchases equivalent to “quantitative easing”,2 confirming the earlier forward guidance that monetary policy was expected to remain accommodative for an extended period of time. The stated objective was to further relax bank funding costs and private borrowing constraints, address the frictions in monetary transmission and to provide a major stimulus for credit growth, domestic demand and job creation in order to secure a sustained return of inflation to a medium-term path just below 2%. The article finds that the ECB’s exceptional monetary stimulus eased financial conditions, revived credit growth and broadly transmitted to the economy as intended.

The ECB broke through the zero lower bound of nominal interest rates in June 2014. Setting its deposit facility rate modestly below zero represented unchartered territory as the ECB was the first major central bank to enter on this course, writing monetary history as it proceeded. Afterwards, the large-scale asset purchases shifted down and flattened the yield curve, leading to negative sovereign interest rates for several euro area countries over the first part of the term structure. Several authors warned about the possible adverse side-effects of a protracted period of ultra-low interest rates. A sustained highly accommodative monetary stance could feed bank disintermediation, fuel financial vulnerabilities and cause economic distortions.3 Examining the evidence up to end-2016, the article concludes that these were legitimate concerns and required the ECB and other policymakers to remain attentive of the unintended consequences of record-low interest rates going forward.

The European micro- and macro-prudential authorities, including the ECB, in this regard closely monitored the health of financial institutions and the potential systemic financial risks and intervened with preventive or corrective measures aimed at preserving financial soundness at the sectoral or national level. Micro-supervision was tightened where necessary to ensure the resilience of individual financial institutions, while macro-prudential tools were employed to deal with systemic financial risks.

The role that monetary policy could play in preserving financial stability is still debated. Some authors have argued that the central bank could take account of financial stability concerns when deciding on the optimal adjustment path for inflation (see (Smets 2014)). This preventive role for monetary policy was justified because the monetary stance affected the general attitude towards risk, the allocation of credit and the strength of the financial cycle, factors which in turn influenced the ability to maintain price stability. The ECB’s two-pillar monetary policy strategy in this respect already incorporated a detailed analysis of money, credit and financial conditions as a safeguard against a too narrow focus on macroeconomic factors determining the short-term inflation outlook (see (Fahr et al. 2013)). In addition, the ECB adjusted the composition and design of its monetary stimulus over time with the aim to support the incentives for financial intermediaries to originate credit and thereby to secure an effective monetary policy pass-through. The consequent improvement in economic prospects and net wealth enhanced the financial capacity of banks to lend and of households and firms to borrow, which also mitigated financial stability concerns going forward even though economic agents assumed more risk.

An appropriate macroeconomic and financial policy mix for the whole Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) also required that each of the 19 member countries contributed with sound complementary measures. A coordinated euro area policy stance could have speeded-up balance sheet repair, accelerated the economic recovery and promoted higher productivity growth, thereby supporting an earlier reversal of the ultra-low interest rates. However, the institutional architecture of EMU lacked effective tools to secure this preferred outcome.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 summarizes the ECB’s monetary policy measures and reviews the empirical evidence of their intended transmission to the economy. Section 3 reviews the unintended side-effects of the extended period of ultra-low interest rates. Section 4 considers the complementary role of non-monetary policies in dealing with the cyclical and structural challenges facing the Eurozone. Section 5 concludes that coordinated policy action by the member countries could have supported the ECB’s fight against low inflation, shortened the episode of ultra-low interest rates and mitigated their adverse side-effects.

2. The ECB’s Monetary Policy Response to Low Inflation

2.1. The Monetary Policy Environment after the Euro Area Crisis

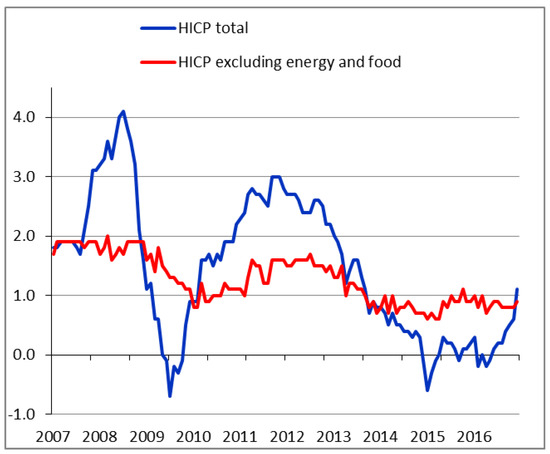

The euro area financial, economic and sovereign debt crisis was halted in mid-2012, and in subsequent months, financial market volatility gradually dissipated. The preceding turmoil cast a long shadow as the process of repairing balance sheets was slow and the heterogeneity of economic and financial conditions across euro area countries persisted. This situation created challenges for the ECB in ensuring the efficacy and singleness of its monetary policy, which is vital for its ability to provide a credible anchor of price stability. Moreover, the steady disinflation of euro area consumer prices to an annual rate far below 2%, weak underlying price pressures, the high degree of unutilized capacity and subdued monetary dynamics indicated an extended period of low inflation (Figure 1).4

Figure 1.

Consumer price inflation in the euro area (annual percentage changes). Source: Eurostat. Latest observation: December 2016. Note: HICP = Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices.

The monetary policy environment during this period was characterized by both credit supply restrictions and credit demand constraints that hampered the operation of the credit channel, especially in the vulnerable member countries. On the supply side, the banking sector was engaged in a drawn-out process of increasing liquidity and capital buffers in response to tighter regulation and reducing the crisis legacy of non-performing loans. Access to bank finance was most constrained in the crisis-affected countries where retail bank lending rates remained relatively high, especially for small and medium-sized firms (see (Darracq Pariès et al. 2014)). Moreover, households and non-financial firms facing a debt overhang needed considerable time to restore sound balance sheets (De Rougemont and Winkler 2014). Together with high unemployment rates and uncertainty over the economic outlook, this protracted debt deleveraging was holding back private sector demand for new credit.

At the same time, many euro area countries had embarked on fiscal consolidation in order to restore public debt sustainability and some pursued structural reforms to revive economic dynamism. Although necessary to strengthen confidence in the future, in the short run, these public sector policies contributed to the broad-based weakness of the euro area economy. Together with falling commodity prices and subdued global price pressures, this macroeconomic setting fueled expectations of secular stagnation, “lowflation”, or even deflation5, especially when the annual rate of consumer price inflation declined to 0.5% in spring 2014 (Figure 1).

The following two sub-sections summarize the monetary policy response to this low inflation environment and review the main empirical evidence of its intended transmission to financial conditions, credit growth and the economy.

2.2. The ECB’s Monetary Easing Measures from June 2014 to December 2016

The Governing Council of the ECB initiated in June 2014 a comprehensive package of measures, which was expanded and recalibrated a few times over the period up to December 2016 (see the timeline in Table 1), to provide the additional monetary accommodation that would support a pick-up in both bank lending and market credit, assist the economic recovery and secure a sustained return of inflation to a medium-term level below, but close to, 2%.

Table 1.

Timeline of main ECB monetary policy decisions from June 2014 to December 2016.

First, the ECB cut its key interest rates in two small steps in June and September 2014, bringing the main refinancing rate down to 0.05%, the marginal refinancing rate to 0.30% and the deposit facility rate to −0.20% (Figure 2). Episodes of negative interest rates had been extremely rare in modern history (Ullersma 2002). Although the eventuality had been debated for advanced economies around the turn of the century (see (Yates 2004)), the ECB was the first major central bank to break through the zero lower bound.6 Therefore, it could not draw on previous experience with this highly unusual monetary policy action. The negative deposit facility rate was expected to fully transmit to market interest rates and to reduce the incentive for individual banks to place their excess liquidity in a safe account with the ECB, rather than in the money market or to use it for lending purposes.

Figure 2.

ECB key interest rates and the euro overnight interest rate (daily data, percentages per annum). Source: ECB, Thomson Reuters. ECB key interest rates at 31 December 2016: marginal lending rate = 0.25%; main refinancing rate = 0.0%; deposit facility rate = −0.4%.

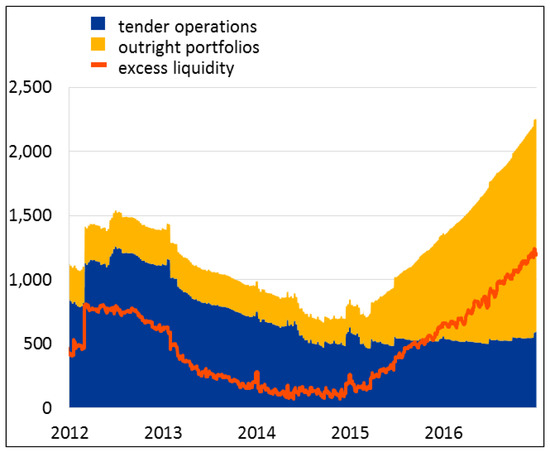

Second, the ECB continued to conduct its main refinancing operations as fixed-rate tenders with full allotment for as long as necessary to give more certainty about the ample availability of bank refinancing over a medium-term horizon. Moreover, it announced a series of targeted longer term refinancing operations (TLTRO I) at the prevailing main refinancing rate (MRO), to be conducted every quarter over a two-year window starting in September 2014 (Figure 3). The amount that banks could borrow was derived from the total amount of their loans to euro area non-financial firms and households (excluding for house purchases). Since these targeted refinancing operations would mature only in September 2018 (with an option of early repayment after two years), this conditional instrument provided built-in incentives for banks to increase lending to the private sector.

Figure 3.

ECB monetary policy operations and excess liquidity (billions of euro). Source: ECB. Latest observation: 31 December 2016. Note: Tender operations include main, longer term and targeted longer term refinancing operations against eligible collateral; outright portfolios include public and private sector asset purchases in the market.

Third, the ECB initiated a private sector asset purchase program (APP), which, together with the TLTROs, was foreseen to lead to a sizeable expansion of the Eurosystem balance sheet back to the large dimension it had in early 2012. The covered bond purchase program (CBPP3) of euro-denominated securities issued by euro area credit institutions was restarted in October 2014, targeted at making bank funding easier. The asset-backed securities purchase program (ABSPP) focused on building up a broad portfolio of simple and transparent instruments and was launched in November 2014. This addition sought to stimulate banks and other financial institutions to originate loans that subsequently could be securitized and sold to the ECB at market conditions in exchange for central bank money.

Finally, the Governing Council expressed its unanimous commitment to use additional unconventional instruments within its mandate should it become necessary to further address the risk of too prolonged a period of low inflation. This could in principle include government bond purchases in the secondary market provided that sufficient safeguards against monetary financing were made and the sovereign credit risks were not mutualized.7 This communication on non-standard measures was consistent with and strengthened the forward guidance given since July 2013 of keeping the ECB’s key interest rates at the prevailing low levels or even lower for an extended period of time.

At the end of 2014, euro area consumer price inflation fell just below zero, largely reflecting the sharp fall in oil prices (Figure 1). Market-based measures of inflation expectations over medium to longer term horizons started shifting down. These negative inflation surprises came at a point in time when the degree of economic slack remained sizeable and signaled the risk of second-round effects on wage and price formation. Furthermore, money and credit growth continued to be subdued.

Although some members were more positive on the inflation outlook over the medium term, the Governing Council made the choice in January 2015 to initiate a quantitatively large expansion of the Eurosystem balance sheet. Focusing on assets with a strong transmission potential and available in sufficient volumes to minimize market price distortions, it added public sector bonds issued by euro area central governments, recognized agencies, and European supranational institutions to the APP (see (ECB 2015)).8 Altogether, the Eurosystem set out to buy outright a monthly amount of €60 bn of public and private sector securities (Figure 3), starting in March 2015 and with the intention to continue until September 2016 and in any case until a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation was achieved back to a level below, but close to, 2% over the medium term. The public sector purchase program (PSPP) was restricted to marketable euro-denominated nominal and inflation-linked bonds of investment-grade quality, with a remaining maturity of between two and 30 years and with yields at the time of purchase at least standing above the ECB’s deposit facility rate. The cross-country allocation of the monthly net asset purchases was guided by the ECB's capital key.9 To preserve market functioning, counter monetary financing concerns and safeguard pari passu (equal) treatment with respect to private creditors, the total amount of public sector bond purchases was capped at 33% of any given issue (after an initial limit of 25%)10 and an aggregate holding limit of 33% per issuer.11 Moreover, the Eurosystem observed a black-out period (during which its secondary-market purchases were suspended, also for securities with neighboring maturities) to allow for market price discovery around the dates when new public sector bonds were issued in the primary market.

Towards the end of 2015, consumer price inflation in the euro area still stood only just above zero (Figure 1). Low inflation persisted because of the slack in the economy and the decline in energy prices weighing on domestic price formation. However, the fact that bank lending rates were declining and private sector borrowing gathered pace offered reassuring signs that the exceptional monetary easing was effective. The expected economic recovery, the pass-through of the past depreciation of the euro and the disappearing base effect from the earlier fall in oil prices also signaled a pick-up in the annual rate of future inflation. Since the inflation forecast nevertheless had to be lowered and downside risks to the inflation outlook prevailed, mostly due to volatility in global markets, a further monetary expansion was still warranted.

The ECB decided in December 2015 to cut the deposit facility rate to −0.3% while keeping constant the two other policy rates (Figure 2). In addition, it extended the period over which the APP would run from September 2016 to March 2017, or beyond if necessary, conditional on realizing a sustained reversal of inflation to a medium term level of just below 2%. Moreover, it decided to reinvest the principal repayments of all of the securities bought as those matured, for as long as necessary, to further extend the effective horizon of the APP and the corresponding favorable liquidity conditions. The range of eligible public sector bonds under the PSPP was thereby enlarged to include those issued by regional and local euro area governments.

During the first months of 2016, following turbulence in global financial markets, the outlook for euro area growth and inflation was again revised down. To reinforce the momentum of the economic recovery and accelerate the return of inflation to a level consistent with price stability, the ECB decided in March 2016 to provide another round of monetary stimulus. The marginal lending rate was reduced to 0.25%, the main refinancing rate put at zero and the deposit facility rate set at −0.4% (Figure 2). The Governing Council expected to maintain the ECB’s interest rates at these low or even lower levels well beyond the APP horizon. Moreover, it increased the size of its monthly net asset purchases to €80 bn while raising the issuer and issue share limits for the purchases of securities issued by European supranational institutions from 33% to 50% to gain additional flexibility in the implementation of the PSPP.

In addition, it further expanded the scope of the APP by adding corporate bonds denominated in euro and issued by non-bank corporations established in the euro area to the range of eligible instruments. The corporate sector purchase program (CSPP) started in June 2016 and was aimed at strengthening the pass-through of the asset purchases to corporate financing conditions and credit growth. The ECB bought the non-bank corporate bonds both in the primary and the secondary markets across the euro area countries conditional on yields at the time of purchase standing above its deposit facility rate. The program was diversified across the whole universe of eligible corporate securities covering a range of economic sectors outside banking, credit ratings of at least investment-grade and remaining maturities of between six months and 30 years. A black-out period was observed for public sector corporations when these issued new bonds in the primary market.

Alongside the CSPP, the ECB further enhanced its credit easing measures through a second series of targeted longer term refinancing operations (TLTRO II), each with a fixed interest rate of at most zero and a maturity of four years, to be conducted every quarter from June 2016 to March 2017. The conditions of this longer term funding were exceptionally favorable for banks that increased their lending to the private sector (excluding for house purchases) relative to a particular benchmark. While the negative interest rate applicable to the ECB’s deposit facility effectively constituted a tax on banks holding excess reserves, those that provided more credit to the economy were offered the opportunity to borrow from the central bank at a subsidized, negative interest rate, which could be as low as the deposit facility rate. This optimization of tools helped to avoid that the costs of monetary easing incurred by the banking industry would outweigh the benefits.

Facing a global rise in long-term interest rates and seeing evidence of a moderate, but firming economic recovery, the ECB again recalibrated its non-standard measures in December 2016. Since underlying inflationary pressures stayed subdued (Figure 1), the APP horizon was further extended from March to December 2017, or beyond if necessary. To mitigate a possible scarcity of eligible bonds, after the turn of the year, the PSPP would also include securities with a remaining maturity of one and up to two years. When necessary to reach the total PSPP volume for a country, the purchases could also comprise those with a yield to maturity below the floor of the ECB’s deposit facility rate, although this implied accepting some costs. As from April 2017, the monthly pace of net asset purchases would be scaled back from €80 bn to €60 bn alongside ongoing reinvestments of the principal repayments from maturing securities bought under the APP. This reduction was made contingent on further progress towards a sustained pick-up in inflation; in case financial conditions became inconsistent with this objective or the economic outlook less favorable, the Governing Council stood ready to increase the size and/or duration of the APP again. These decisions introduced more flexibility in the APP and a state-contingent implementation to guarantee a more sustained presence in the market and a more lasting monetary transmission.

2.3. The Intended Effects of the ECB’s Monetary Stimulus

The comprehensive monetary stimulus measures implemented during the 2½ years from June 2014 to December 2016 and the forward guidance of a continued accommodative monetary stance have been instrumental in preventing another economic downturn. The pass-through of monetary policy to the euro area economy operated as expected along three mutually-supportive transmission channels.

First, the very substantial monetary easing lowered interest rates and hence the price of credit. The supply of central bank liquidity to the banking system (both through tender operations and outright asset purchases) and the decline in money market and deposit rates compressed bank funding costs. This in turn created incentives for banks to supply new loans against lower lending rates and easier credit conditions as the creditworthiness of borrowers was improving. Empirical studies showed that the news of the non-standard monetary stimulus measures from June 2014 to December 2015 significantly lowered bank lending rates offered to non-financial firms, even more so in the vulnerable euro area countries (Figure 4) and for banks with less capital and more non-performing loans (see (Altavilla et al. 2016)).

Figure 4.

Composite bank interest rates for new loans to non-financial corporations (percentages per annum). Source: ECB. Latest observation: December 2016. Note: The composite cost of bank lending combines short- and long-term rates on new loans using a 24-month moving average of new business volumes as weights. The cross-country dispersion displays the minimum and maximum range over a fixed sample of 12 euro area countries.

The favorable monetary impact of this direct channel of transmission was also evidenced by the quarterly euro area bank lending surveys (see (Köhler-Ulbrich et al. 2016)). Most banks on balance reported that the negative deposit facility rate had supported a further decrease in their lending rates with a positive impact on lending volumes and that they expected the same impact over the period ahead. More favorable funding conditions in wholesale markets and the higher value of collateral posted by firms similarly translated into a lower price of credit offered by non-bank intermediaries. The steady decline in the cost of new borrowing as the economic outlook became brighter furthermore enhanced the demand for credit, whereas the falling servicing costs on outstanding variable-rate debt expanded disposable income for borrowers.

Second, the outright asset purchases targeted a reduction of risk spreads in interest rates. The prospect of the large-scale securities purchases over a long maturity spectrum, especially with regard to public sector bonds, made the eligible assets appear scarcer and had the immediate effect of removing a substantial amount of credit and duration risk from the economy,12 while the actual monthly purchases mostly took out liquidity risk. The selling counterparties (banks and non-banks) in exchange received safe and readily available central bank money in their deposit accounts, which translated into growing (excess) reserves held by the banking sector (Figure 3). The net risk extraction responded to the elevated market demand for safe and liquid assets and created incentives for bank and non-bank investors alike to shift into more risky assets of longer duration, including loans.13

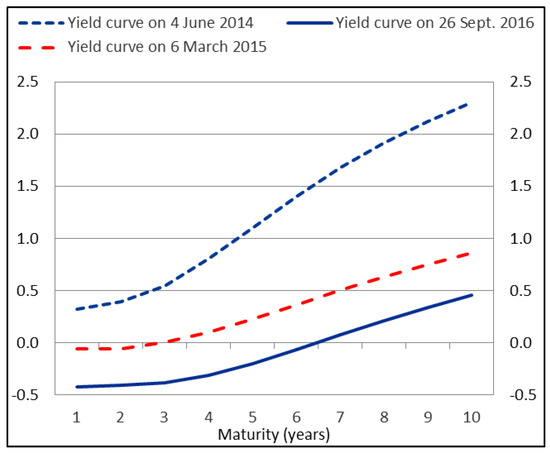

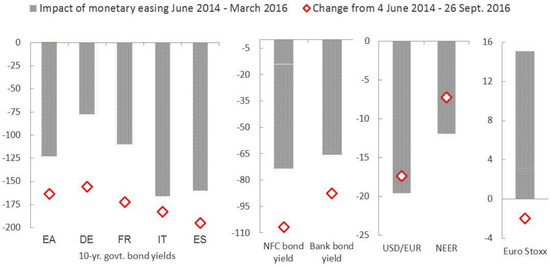

This process of portfolio rebalancing generated spill-over effects across many asset markets and was an indirect channel of transmission through which monetary policy lowered sovereign and corporate bond yields, as well as contributed to a deprecation of the euro exchange rate, a rise in stock prices and an increase in inflation swap rates (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Econometric event studies and news analyses suggest that the anticipation, announcement and subsequent start of the PSPP significantly reduced government bond rates, notably further along the yield curve and more for the vulnerable euro area countries (see (Altavilla et al. 2015; De Santis 2016)). On the day of the announcement of the CSPP, the yield spreads on eligible corporate bonds declined sharply and continued to decline in subsequent weeks. The prevailing low level of financial stress supported spill-overs to other, non-eligible securities, showing how investors used their improved risk-bearing capacity to integrate asset prices across targeted, as well as non-targeted market segments.

Figure 5.

Euro area average government bond yield curve (synthetic yields in percentages per annum and maturity in years). Source: Bloomberg, ECB.

Figure 6.

Asset price changes and the impact of ECB monetary easing (changes in basis points for bond yields, in percent for exchange rates and stock prices). Source: Bloomberg, ECB calculations. Note: The impact of monetary easing measures from June 2014 to March 2016 is estimated with econometric event studies, news analyses and model-based counterfactual exercises with a focus on announcement effects. See also (Altavilla et al. 2015) and (De Santis 2016). EA, DE, FR, IT and ES = Euro Area, Germany, France, Italy and Spain, respectively; NFC = non-financial corporations; USD/EUR = nominal euro exchange rate to the U.S. dollar; NEER = nominal effective exchange rate of the euro; Euro Stoxx = Dow Jones Euro Stoxx (broad) index.

The broad-based asset price increases furthermore strengthened the capital position of credit intermediaries, reduced their leverage constraints and increased their ability to lend, whereas the higher collateral values enlarged the capacity of their customers to borrow and lowered the cost of capital in general. An important advantage of the steady narrowing of risk spreads was also that the earlier cross-country differences in terms of access to credit and cost of capital and hence the financial fragmentation of the Eurozone diminished considerably (Figure 4). The macroeconomic impact of this quantitative monetary easing was estimated to be broadly similar to that of a standard reduction of the policy rate by at least one percentage point (see (Andrade et al. 2016)).

Third, two types of forward guidance signaled that the monetary stance would remain accommodative for as long as necessary to deliver price stability. The Governing Council signaled that the ECB’s key interest rates would remain low or could be even lower for an extended period of time, well past the APP horizon. In addition, it made the intended net asset purchases under the APP conditional on realizing a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation, later adding that it could increase their size and/or duration if the economic outlook became less favorable or financial conditions tightened again.

This signaling channel anchored longer term inflation expectations, which otherwise could have drifted further below the level consistent with the ECB’s definition of price stability, as shown by counterfactual model simulations (Coenen and Schmidt 2016). Evidence from private sector surveys confirmed that the expansion of the APP with public sector bonds was perceived as a sign of easier monetary policy and generated expectations of higher output growth and inflation up to two years ahead. The improved short-term inflation outlook also contributed to a re-anchoring of longer term inflation expectations (Andrade et al. 2016). More generally, by signaling higher expected inflation, the ECB promoted a reduction in the level of real interest rates, which eased financial conditions and supported asset valuations. The strengthening of business sentiment and household confidence in this context increased private incentives to spend rather than save while weathering a number of adverse global shocks from seriously hurting the euro area economy.

Overall, the transmission of the monetary easing measures worked broadly as intended. The monetary stimulus helped to spur a turnaround in the volume of bank lending to the non-financial private sector from a contraction at an annual rate of 1.75% in early 2014 to a modest expansion at an annual rate of about 2.0% in late 2016. The recovery of bank borrowing was broad-based, covering both households and non-financial firms (Figure 7) and extended to all euro area countries. The access to bank loans at more favorable borrowing conditions moreover improved for large, as well as for small- and medium-sized firms, as also confirmed by the half-yearly euro area survey on access to finance for enterprises. Meanwhile, supported by the monetary impact of the central bank liquidity injections, the annual growth rate of the broad monetary aggregate M3 rose steadily and stabilized between 4.5% and 5% (Figure 7), offering ample scope for output growth and inflation rates to rise to more satisfactory longer term levels without stoking exuberant asset price increases.

Figure 7.

Broad monetary aggregate M3 and bank lending to the non-financial private sector (annual percentage changes). Source: ECB. Latest observation: December 2016. Note: Bank loans are adjusted for loan sales, securitization and notional cash pooling.

According to macroeconomic model calculations undertaken by Eurosystem staff, the total monetary stimulus provided up to mid-2016 was projected to add some 1.5 percentage points to real GDP growth in the euro area when cumulated over the period 2015 to 2018. The decline in consumer price inflation to below zero was halted in 2015, and the annual rate of inflation was forecast to be on average at least 0.5 percentage point higher in both 2016 and 2017 than without the monetary easing. These empirical estimates indicated a significant monetary boost to the euro area economy. Market information confirmed that by end-2016, the risk of deflation had largely disappeared. This translated in a steepening of the sovereign yield curve, also under the influence of global trends and the adjustments made to the APP in December 2016.

3. Unintended Side-Effects of a Protracted Period of Ultra-Low Interest Rates

3.1. Worries about Financial Intermediation, Financial Stability and Market Discipline

To provide a meaningful monetary impulse, several central banks including the ECB have resorted to negative policy rates and quantitative easing in order to push down the sovereign yield curve to ultra-low levels and even into negative territory at short- to medium-term horizons. This extraordinary constellation of interest rates gave rise to a number of concerns about the potential adverse side-effects of these unconventional monetary policies, in particular for financial intermediation, financial stability and market discipline.

First, as stressed by McAndrews (2015), there are questions about the central banks’ ability to push and sustain the policy rate below zero, since this unusual move may hamper the functioning of financial markets, compress the earnings of financial intermediaries, constrain monetary transmission and dampen the ultimate economic impact of monetary easing. The impact of a monetary stimulus of this kind could even reverse into a contraction, suggesting that there is an economic lower bound for negative interest rates (Cœuré 2016).

A second concern for central banks is associated with what Cecchetti (2016, p. 160) calls “the dark side” of monetary policy accommodation. The injection of central bank liquidity to engineer a very low nominal and real cost of borrowing encourages financial intermediaries to search for yield in more risky markets. An abundant supply of cheap credit and a reduced screening of borrowers could enable economic agents to accumulate an unsustainable stock of debt, which could fuel excess consumption and low-return investments. Although the easing of financial conditions overcomes credit rationing and is the key to lifting output growth and inflation, the risks from overextended private sector leverage for financial stability and the adverse effects of misallocated credit for productivity growth weigh more heavily the longer the central bank maintains its ultra-easy monetary stance (see also (Adrian and Liang 2014; Borio and Zabai 2016; White, 2016)).

Third, central bank purchases of government bonds interfere with public debt management and raise complicated coordination issues with fiscal policy (Hoogduin and Wierts 2012). The concern is that quantitative easing distorts price signals along the entire sovereign yield curve and weakens market incentives for governments to pursue sound public finances and progress with structural reforms. Although the favorable net wealth effects of the broad-based repricing of assets support private spending, the distributional implications of unconventional monetary policies are significant and may undermine public support for central bank independence (see (De Haan and Eijffinger 2016)).

The following sub-sections review the euro area relevance of these unintended side-effects focusing on six issues: the functioning of financial markets, the income and wealth position of households, the profitability of the banking industry, the challenge for institutional investors, the private sector’s attitude towards risk and the incentives for governments to maintain fiscal discipline.

3.2. The Functioning of Financial Markets

The first question that comes up when a central bank policy rate reaches the zero bound is whether and how this low level will transmit to financial markets. Lack of experience made the monetary authorities hesitant to touch zero, let alone to pursue a negative interest rate as a feasible policy option (McAndrews 2015). Money market funds that promise a constant rather than variable net asset value are subject to contractual obligations that assume a positive return. When they cannot deliver these returns, their clients will run away, and their existence is endangered. Their operational difficulties in turn could hamper a proper functioning of money markets. Furthermore, financial contracts may have to be amended to allow for the unusual situation of creditors making interest payments to debtors rather than the other way round. In addition, market infrastructures and computer systems may have to be adapted to allow for it. Even when transient, legal and technical costs put up a barrier. As a result, the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates was traditionally perceived as the absolute floor for central banks. With short-term interest rate expectations truncated at zero, markets could only expect policy rates to go up, and this translated into an upward sloping forward yield curve.

The ECB broke through the zero line with its deposit facility rate and was able to steer the euro overnight interest rate towards a mildly negative level (Figure 2). The anchoring of short-term interest rate expectations below zero not only drove down the forward yield curve, but also triggered a flattening. Rostagno et al. (2016) point out that removing the non-negativity constraint on future expected short-term rates rehabilitated the standard ability of monetary policy and forward guidance to influence the term structure in a low interest rate world, at least up to the point of the effective lower bound, the exact position of which was left open. Since markets will try to guess how much further down the central bank may want to go, the lower bound itself could be interpreted as a monetary policy parameter (see (Lemke and Vladu 2016)).

As reported by Bech and Malkhozov (2016), the negative interest rate on the ECB’s deposit facility smoothly transmitted to the money market and was accompanied by receding cross-country spreads in overnight rates. Money market functioning was affected in different ways. Trading activity was reduced somewhat as market participants tried to avoid the negative interest rate by moving into instruments with longer maturities, also driven by growing excess reserves and regulatory demands placed on banks. Money market funds found a contractual solution to deal with the falling return on their net assets and experienced net inflows, for example from large corporates that faced negative rates on their overnight bank deposits. Banks offering variable-rate mortgages (calculated as a small surcharge on the money market rate) were in a few cases forced to apply the contractual terms and had to pay their borrowers the negative interest rate. From an operational point of view, however, there were no major obstacles to applying a negative deposit facility rate.

Considering capital markets, the PSPP compressed sovereign bond yields to ultra-low levels such that for short- to medium-term maturities, they fell below zero (Figure 5). High-rated sovereign bonds even recorded negative yields on long-term bonds as term premia became negative.14 Since all investment-grade public sector bonds of member countries were eligible, the start of the PSPP reduced sovereign credit risk and contributed to a significant narrowing of interest rate spreads relative to the German bund notably for longer durations (see (Altavilla et al. 2015; De Santis 2016)). The continuous presence of the Eurosystem as a buyer in the secondary market also compressed the liquidity risk premia in sovereign bond yields. Other than that, the Eurosystem tried to preserve market functioning and smooth price discovery by mostly carrying out a large number of small-scale purchases on a daily basis, acting as a marginal buyer and taking account of trading liquidity and market activity.

Later on, a growing number of market actors had difficulty raising secured short-term funds because the steady flow of PSPP purchases, as well as regulatory requirements favoring high-quality liquid assets reduced the remaining pool of sovereign bonds traditionally used as collateral in repurchase agreements. Towards the end of 2016, some short-term government bond yields dropped well below the ECB’s deposit facility rate in response to this growing scarcity. The ECB and some national central banks therefore made their acquired government bonds available to interested counterparties for securities lending, also accepting cash as collateral, in order to support bond and repo market liquidity and collateral availability. Also the private sector securities bought under the CBPP3 and the CSPP were made available for securities lending.

3.3. The Income and Wealth Position of Households

Borio and Zabai (2016) observe that positive interest rates are deeply rooted in society reflecting the fundamental role of money as an unremunerated benchmark asset that serves as the unit of account in the economy. Given their positive time preference, households expect to receive a positive interest rate on their saving deposits as compensation for postponing consumption from the present to the future. A zero interest rate on saving deposits is regarded as unnatural and negative rates are seen as an unfair tax; even when corrected for low (expected) inflation, the negative real return they get may be well within normal boundaries given the state of the economy. Moreover, ultra-low interest rates and the attendant capital gains on financial assets are generally perceived as leading to a redistribution of income and wealth from savers to borrowers or from the poor to the rich without democratic legitimation.

The main line of defense available to households to avoid a punitive negative interest rate on their registered saving accounts is to convert them into cash, a bearer instrument, which offers not only the convenience of immediate payment services, but also of anonymity. Given the costs of transport, storage and insurance related to hoarding a substantial amount of currency and the time savers have to invest in order to handle the cash, the effective lower borderline for deposit rates may be slightly below zero before they would contemplate such a move (see (Cœuré 2016)). Given the even larger amounts involved, the threshold would be somewhat lower for large firms that want to protect the cash flow on their bank accounts. An even lower limit likely applies to countries where the dominant role of currency in retail payments has already been overtaken by automated systems, as in Sweden. However, the accumulated negative returns of a prolonged period of below-zero interest rates may just tip the balance between costs and benefits toward holding more cash than deposits. Furthermore, banks might then keep part of their reserves in the form of vault cash to directly settle their money market transactions with other banks instead of using a central bank account. Over time, the market might develop the necessary banknote warehousing services.

A surge in the demand for banknotes to escape the (risk of) negative bank deposit rates was at least up to end-2016 not visible in the Eurozone. Yet, member countries placing a legal limit on the amount of cash that their citizens can carry, in order to prevent tax evasion, met with criticism. Similarly, the ECB received some negative reactions on its decision to discontinue the production of the 500 euro banknote and to stop its issuance around the end of 2018, although it will always remain legal tender. The decision addressed concerns that this euro banknote with the highest denomination could facilitate illicit activities. There was however no intention to impose a carry tax on cash, abolish currency or to introduce a depreciating exchange rate of banknotes relative to electronic money in bank accounts, as has been suggested in the academic literature as a way to overcome the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates (see for example (Buiter 2009; Kimball 2015)).

The distributional effects of monetary policy are wide-ranging and work through both financial and macroeconomic channels (see (Deutsche Bundesbank 2016) and (Draghi 2016)). Savers are affected in their position as retail deposit holders, as owners of bonds, shares and residential property, as well as in their function as employee and taxpayer. Concerning financial income, euro area households on balance have seen their interest earnings (as a share of their disposable income) decline markedly since 2008 (see (Rostagno et al. 2016)). While this triggered a debate on the apparent “expropriation of the saver” (Bindseil et al. 2015), on average, the interest income of households remained positive and continued to exceed debt interest payments, although the balance between the two was negative for euro area countries where mortgage debt was particularly high. Estimates suggest that the additional monetary easing since June 2014 on average created positive net wealth effects for all wealth groups, since both bond prices and house prices rose until mid-2016, while equity values fell somewhat. The net benefits were nevertheless larger for the richer households than for families without savings in the form of security holdings.

The distributional effects of ultra-low interest rates can also be found on the macroeconomic side. The monetary expansion helped to improve corporate profitability and supported job creation. The brighter labor market situation reduced the risk of unemployment above all for low-skilled, poorer households and supported their future income. These were also the liquidity-constrained households with a relatively high marginal propensity to consume. Finally, the fight against too low inflation countered an arbitrary redistribution of wealth between generations, since unexpected deflation would raise the real value of debt and the young were net debtors, whereas the old were net creditors.

3.4. The Profitability of the Banking Industry

A key concern with a negative interest rate policy and quantitative easing is that it could hurt the health of the banking sector with adverse consequences for monetary transmission. The flattening of the yield curve implies a narrowing spread between (short-term) borrowing and (longer term) lending rates and hence reduces the financial income from maturity transformation. At the zero lower bound, banks are constrained in further lowering the cost of deposit funding, whereas fierce competition forces them to follow markets in reducing rather than raising lending rates in an effort to offset lower net interest rate margins by larger loan volumes. A negative rate of remuneration on excess reserves held by the banking sector and attractive low corporate bond market rates engineered by the central bank could also move credit business for large firms away from banks towards non-banks especially when the latter are subject to less tight regulation. Moreover, outright purchases of public sector securities could be subject to diminishing returns, making the boost to the value of bank asset holdings dissipate over time.

As expected, the banking industry was reluctant to pass on negative money market rates into retail deposit rates (apart from some isolated cases; see Figure 8). Especially banks with a deposit-based funding structure could not afford hurting the relationship with their clients; although larger companies and institutional investors were confronted with slightly negative rates on their bank accounts and retail clients with higher transaction fees. Moreover, the APP increased the amount of excess reserves charged with a negative deposit facility rate, which the banking sector as a whole had to hold, and also lowered bond yields and tilted the term structure down. In addition, the conditional nature of the TLTRO operations spurred competition in bank lending. These circumstances weighed on bank profit margins and the incentives for originating new loans.15

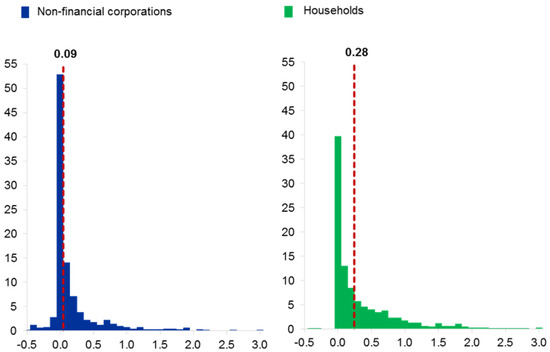

Figure 8.

Distribution of deposit rates for non-financial corporations and households across euro area banks (x-axis: deposit rates in percentages per annum; y-axis: frequencies in percentages). Source: ECB. Observations refer to October 2016. Note: Deposit rates on new business as reported by individual banks. The dotted lines show the weighted averages of deposit rates.

The ECB modulated the composition and design of the monetary easing measures over time, inter alia to avoid that the negative interest rate would turn from a tax on hoarding excess reserves into a tax on financial intermediation (Rostagno et al. 2016). The exceptional monetary easing reduced the cost of bank funding in wholesale markets (especially in the previous crisis-hit countries), and the ECB offered conditional four-year liquidity in its second program of longer term refinancing operations (TLTRO II) at a zero interest rate or with a subsidy for banks exceeding their credit growth benchmarks. As evidenced by the euro area bank lending survey of July 2016, most banks acknowledged that the TLTRO II (as implemented from June 2016) offered a significant boost to their profitability (see (Köhler-Ulbrich et al. 2016)). The steepening of the yield curve in late 2016 also relieved some of the strains on bank interest margins.

Those banks that took the opportunity of the APP to sell their eligible public sector assets to the Eurosystem also enjoyed significant capital gains. The subsequent decline in longer term interest rates and the general rise in asset prices as investors rearranged their portfolios provided further capital relief, especially to banks holding a large portfolio of government bonds, as reported by Andrade et al. (2016). The expansion of the range of eligible public sector bonds and the inclusion of corporate bonds created additional positive valuation effects due to the APP and further strengthened the capital position of banks owning these assets.

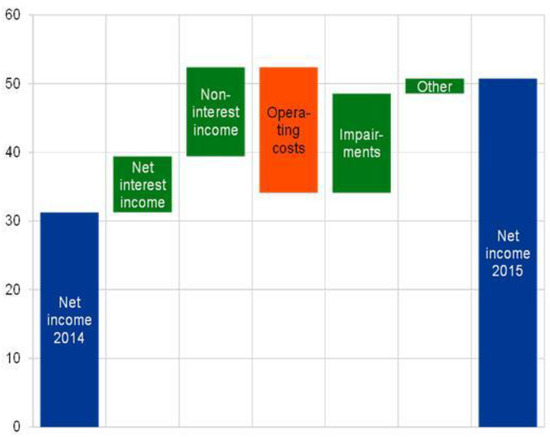

Furthermore, the general easing of financing conditions and the favorable net wealth effects from higher asset prices improved the economic outlook and the demand for loans from the private sector, enabling the banking sector to expand its credit business. Moreover, higher collateral values improved the debt affordability of borrowers and allowed many banks to reduce provisions for non-performing loans. Even when bank lending rates declined and intermediation margins narrowed, there was thus ample scope for banks to increase their total profits. On aggregate, the euro area banking industry was still able to improve its profitability in 2015 (Figure 9), although data for the first part of 2016 were mixed. As markets assessed the near-term outlook for the banking industry to be less benign, also because of non-performing loans and structural overcapacity, bank equity prices underperformed in the first half of 2016. Later in the year, when the economic outlook became brighter, bank share prices staged a relatively strong recovery.

Figure 9.

Change in net income of euro area significant banking groups (decomposition of change in net income between 2014 and 2015 in billions of euro). Source: SNL Financial and ECB calculations. Note: Based on data for a sample of 83 euro area significant banking groups.

3.5. The Challenge for Institutional Investors

Not only banks, but also institutional investors face difficulties in an ultra-low interest rate environment. Life insurance companies and pension funds will see the value of their liabilities rise when they have to discount them at a low, market-related interest rate, whereas the valuation gains on their assets are dependent on the type of instrument. Life insurers with a legacy of liabilities offering a relatively high long-term guaranteed return require a steady positive income flow on their investments. Yet, the return on their maturing fixed-income instruments will decline as these get rolled over at much lower coupons. A prolonged period of much lower than expected yields could mean increasing funding shortfalls and constitute a growing solvency threat. Pension funds with defined benefit schemes face a similar funding challenge, in particular those with a maturity mismatch between (medium-term) assets and (long-term) liabilities. While equity returns and capital gains should offer some compensation, this may not be enough to provide for the promised future pension and insurance pay-outs when these are fixed in nominal terms (see (McAndrews 2015)).

Supervisors concerned with the solvency implications of ultra-low interest rates will exercise pressure on less capitalized institutional investors to raise pension contribution rates paid by employers and employees, collect higher insurance premiums from their clients or cut future entitlements so as to cover the gap between assets and discounted liabilities. In addition, they will urge those institutional investors offering guaranteed products to transfer a larger share of the investment risks to the pension plan members and insurance policy holders. The subsequent increase in mandatory or personal retirement savings following this supervisory pressure shows that for some parts of the population, protracted low interest rates can also have the opposite effect of stimulating domestic demand.

Given the growing importance of institutional investors for capital market financing in the euro area, their response to changes in the economic and financial environment is of increasing relevance when analyzing the propagation of monetary impulses (ECB 2016a). On the one hand, the decline to very low interest rates raised the demand for higher-yielding products offered by insurance corporations and pension funds. This has allowed them to play a greater role as financial intermediaries in providing household mortgages or in funding firms that were returning to capital markets. On the other hand, national supervisors urged institutional investors in their jurisdiction to address their regulatory asset shortages or improve their long-term profitability. Several occupational pension funds raised pension contribution rates so as to avoid having to cut nominal pension entitlements (after having suspended the inflation correction already for several years). Governments lowered the guaranteed rate of return on new life insurance policies. Life insurers also increasingly aimed at selling more unit-linked products, the return on which is directly linked to the performance of financial markets (see (ECB 2016b; ESRB 2016a)). Meanwhile, the steepening of the yield curve in late 2016 reduced some of the pressure on institutional investors.

3.6. The Private Sector’s Attitude towards Risk

Persistently negative nominal and/or real interest rates could encourage the private sector to build-up excess leverage and reach for higher returns in more risky and less liquid assets. This endogenous risk assumption exposes private agents to abrupt asset repricing and higher market volatility which, if their risk-bearing capacity is weak, constitutes a danger for financial stability (ESRB 2016a). Low or negative yield levels also hamper the ability of market participants to accurately price risk since they make standard net present value calculations less informative. This could lead to distortions in investment decisions and a misallocation of savings (ECB 2016b).

A decline in the return on their assets could push banks, in particular those that are weakly capitalized, towards expanding their balance sheets while accepting excessive risk exposures. On the liabilities side, they could increase the share of more volatile short-term market funding relative to stable deposits. On the assets side, growing competition from within the banking industry, as well as from non-banks may spur undercapitalized banks to offer overly generous interest rate conditions and repayment terms in order to attract more lending business. ”Betting for resurrection”, they might shift their credit portfolio especially towards low-quality borrowers who would normally not pass the screening process.

The low interest rate environment may also prompt institutional investors and asset managers to take on more leverage and to adjust the composition of their portfolios towards higher yielding, but more speculative categories of investment, with possible negative consequences for financial stability. Non-financial corporations could use the opportunity of the very low cost of capital to acquire cheap funds for high-risk investment projects, which otherwise would not have passed the hurdle rate of return. Although retail savers tend to be rather conservative investors, a prolonged squeeze of their (after-tax) interest income could motivate them to shift their saving deposits towards potentially more lucrative destinations.

The general risk-on attitude could trigger a boom in the demand for housing, commercial real estate, low-quality capital goods, high-yield bonds, sub-prime equity and exotic securities, and drive up a wide array of asset prices to unsustainable levels. The overall effect, if not countered by tighter monetary policy and/or supervisory intervention, might be a more risk-prone financial structure and a less productive capital stock, waiting for a sudden shift in market sentiment or disappointing profits to trigger a bust in asset prices.

Considering the euro area, many financial institutions have assumed more credit and duration risk and bought less liquid assets as they searched for more attractive returns in an environment of very low interest rates. The securities holdings statistics for the euro area show that investment funds in particular increased the duration of their portfolios. Euro area insurers and to a lesser extent pension funds shifted their assets more towards non-euro area government bonds, corporate bonds with lower credit ratings and illiquid assets, such as property and infrastructure (see (ECB 2016b)).

Euro area banks with a deposit-based funding structure faced downward pressure on their net worth, because they were reluctant to pass the negative market interest rates on to their depositors and still lowered their lending rates. Especially those with a smaller equity buffer responded by concentrating their lending business on new risky borrowers, who used this credit to increase investment (see (Heider et al. 2017)). These high-deposit banks, compared to low-deposit banks, extended more syndicated loans (which represent only a small fraction of total bank lending) to credit-constrained risky firms without charging higher loan spreads, demanding more collateral or setting stricter loan conditions to offset the attendant extra credit risks. Accordingly, the average quality of their syndicated loan portfolios deteriorated. By contrast, banks relying more on market funding and less on deposits gave more syndicated loans to safer borrowers. Poorly capitalized banks might also be willing to roll-over non-performing loans at very low interest rates and relatively favorable terms and conditions so as to avoid having to record losses. Acharya et al. (2016) find evidence for this ever-greening of non-productive companies in the euro area, which implied a misallocation of credit to the detriment of more productive high-quality borrowers.

After the onset of the CSPP, non-bank corporations issuing eligible investment-grade bonds saw a strong decline in yield spreads and took the opportunity to issue more debt securities. A broadly similar spread contraction relative to the starting level was observed for bank bonds and “junk” bonds, even though these were ineligible for the CSPP, indicating the impact of portfolio substitution. Accordingly, a wide range of firms benefited from the lower costs of capital market funding. Yet, this finding also indicated that more risky firms gained access to market credit at lower costs than otherwise. Their relatively strong debt issuance as bond yields declined over the past few years suggested that less productive companies may have been able to survive in contested markets, despite realizing a lower return on their assets than their more profitable competitors.

As regards asset price inflation in the euro area, share prices (except for banks) and especially bond prices broke earlier record levels in the wake of the ECB’s reinforced monetary easing (Figure 6). Housing and commercial property markets in some euro area countries showed relatively strong upward price dynamics in specific regions and segments (also reflecting local factors), which could yet quickly spread out to other areas. The positive net wealth effects from higher asset prices could evaporate once interest rates reversed course. This exposure to rising interest rates entailed risks for financial stability (see (ECB 2016b; ESRB 2016a)). These concerns were mitigated by the ongoing gradual decrease in the ratio of household debt to disposable income since 2013 while the leverage ratio of non-financial corporations already recorded a decline between 2009 and 2014 and has since been fairly constant. The more resilient balance sheets of households and firms underpinned the sustainability of private consumption and investment as the main drivers of the economic expansion in the euro area.

3.7. Public Debt and Fiscal Discipline

Monetary policy interventions aimed at keeping interest rates low for a prolonged period stimulate not only debt-financed private demand, but also borrowing for public spending despite already high public debt-to-GDP ratios. Large-scale central bank purchases of public sector bonds coincide with a strong private sector interest in keeping them as safe and liquid assets, also for regulatory purposes. With many price-insensitive buyers in sovereign bond markets, who together push the yields down, governments generally face less market discipline and in fact are given an incentive to accumulate more debt and postpone structural reforms of their economies. Moreover, a part of the interest payments is accrued by the central bank and will return to the state in the form of seigniorage payments (unless these profits are added to the reserves). The lower debt service costs and higher seigniorage income that governments enjoy, give a flattering picture of public debt sustainability (Hannoun 2015).

When monetary policy goes into reverse, governments will have to refinance a larger stock of public debt at higher interest rates. The central bank incurs valuation losses on its government bond portfolio, and it may have to cut back its seigniorage payments (depending on the applicable accounting and provisioning rules). Financial institutions are also confronted with a rapid decline in the value of their government bond holdings and thus a lower net worth, which could scare off investors and precipitate a fall in their bond and share prices. The government may even be obliged to inject capital into troubled banks. Under these circumstances, the central bank could come under pressure from politicians to prolong its public sector bond purchases and/or to cap the rise in capital market rates, making it increasingly difficult to arrange an exit from unconventional monetary policy (Borio 2014). Having to maintain an outsized balance sheet would expose the central bank to financial risks and threaten its credibility as an independent institution (De Haan and Eijffinger 2016).

Forward-looking public debt managers will aim to reduce roll-over risk by issuing relatively more long-term bonds at the exceptionally low interest rates. This additional supply directly counters the objective of the central bank’s outright purchases to flatten the sovereign yield curve, showing how monetary policy and public debt management become intertwined (Hoogduin and Wierts 2012). To deal with this situation, Greenwood et al. (2014) argue that monetary and fiscal authorities should coordinate their bond market operations or that governments should abandon traditional principles of prudent financing and issue more short-term treasury bills.

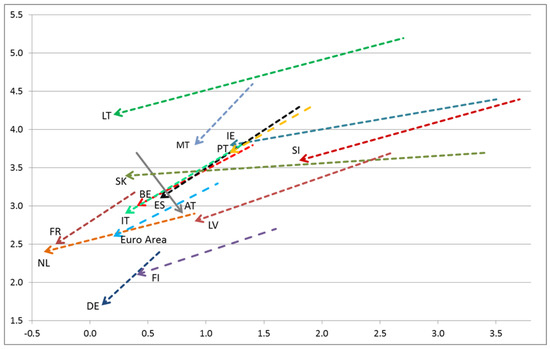

Euro area governments have enjoyed a rapid decline in the marginal cost of capital market funding since mid-2012 and in particular since the onset of the PSPP. Most governments were able to issue debt at negative market rates for maturities up to five years, and for core countries, the negative bond yields covered horizons of at least up to ten years (see also Figure 5). The significance of this fiscal space was visible in a steadily declining euro area average nominal interest rate paid over the outstanding stock of debt securities (from 3.3% in May 2014 to 2.6% in December 2016), as well as for new issuance over the most recent 12 months (from 1.1% in May 2014 to 0.2% in December 2016, with Germany, France and the Netherlands reaching yields on newly-issued debt securities of close to 0% or below; see Figure 10). Moreover, the Eurosystem received interest on its growing stock of public and private sector bonds, which allowed extra seigniorage payments by national central banks to their governments unless these profits were added to the reserves. More generally, the monetary stimulus supported nominal GDP growth and reduced unemployment rates, which further improved public finances by lowering primary expenditure and boosting tax revenues.

Figure 10.

Government debt securities issued by euro area governments, average yield (x-axis: yield on debt securities issued over the last 12 months in December 2016 compared to May 2014; y-axis: yield on the stock of debt securities in December 2016 compared to May 2014; percentages per annum). Source: ECB. Note: National data exclude Greece, Cyprus, Estonia and Luxembourg. The deviating pattern for Austria may be related to the downgrade of its credit rating from AAA to AA and its issuance of two relatively expensive bonds with an ultra-long maturity of 30 and 70 years.

The EU fiscal rules of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) focus on the structural budget balance, and the steadily falling interest bill for euro area countries thus in principle facilitated a faster reduction of structural overall deficit and public debt-to-GDP ratios. The SGP also constrains government spending growth in excess of trend GDP growth, that is without taking changes in interest payments and cyclical unemployment benefits into consideration. The euro area countries that still had to meet their objective of a broadly balanced budget over the medium-term could therefore not use the savings from lower interest costs and falling unemployment rates as an argument for stepping up public spending. Several fiscal policymakers nevertheless decided to slow down or reverse the pace of deficit reduction. The steady demand from their national central bank for national sovereign bonds facilitated public debt issuance and may have weakened fiscal discipline. Ensuring compliance with EU fiscal rules is of paramount importance to guarantee sound public finances in EMU, but gains even more significance when the national central banks assume a large quantity of credit risk related to their own governments on their balance sheets as part of quantitative easing operations that aim to safeguard price stability.

Meanwhile, national public debt managers took the chance to frontload their borrowing programs and to lengthen the average maturity of outstanding debt so as to entrench the historically low long-term interest rates. Profiting from a large investor demand, several euro area countries were able to issue or place 50-year bonds (Belgium, France, Italy and Spain), 70-year bonds (Austria) or even century bonds (Belgium, Ireland) in 2015 to 2016. For all euro area countries together, the average residual maturity of the outstanding amount of government debt securities increased from 6.4 years in May 2014 to 6.9 years in December 2016. As a consequence, public debt management strategies increased the supply of duration risk for investors at a time when the ECB sought to extract it through its PSPP. Andrade et al. (2016) examine the changing debt maturity structure during 2015 and conclude that despite the rising average maturity of newly-issued public debt (net of redemptions), the PSPP on balance still managed to extract a significant amount of duration risk from the economy. Given the institutional setup of the EMU, explicit coordination of national public debt managers with the ECB could not take place.

4. The Complementary Role of Non-Monetary Policies

4.1. The Advantages and Limitations of the Two-Pillar Monetary Policy Strategy

The challenge facing the ECB from 2014 to 2016 was to monitor, manage and, where possible, to minimize potential negative side-effects of a prolonged monetary stimulus that was calibrated to ensure medium-term price stability (Draghi 2015). The two-pillar monetary policy strategy in this respect entailed a detailed forward-looking analysis of economic, as well as monetary conditions in the euro area, as impacted by the exceptionally favorable interest rates. The macroeconomic implications for the short-term inflation outlook were always cross-checked with the medium-term inflation trend associated with money and credit growth.

Giavazzi and Wyplosz (2015) take a critical view of the usefulness of a cross-check with monetary information, arguing that it unnecessarily clouds the analysis and confuses communication. Yet, the impact of ultra-low interest rates was visible in particular in easier financial conditions and a rebound in money and credit, which signaled a pending revival of output growth and inflation. Furthermore, as the economy recovered and money and credit growth gathered pace, the ECB’s cross-checking of inflation prospects would naturally lead to a tightening of the monetary stance when the risks for financial stability became more prominent (see (Fahr et al. 2013)). The monitoring of euro area monetary and credit aggregates would in this regard need to be complemented with a detailed flow-of-funds analysis in order to fully capture possible divergences in financial conditions across countries and sectors. Any adverse consequences of monetary easing for financial stability in local markets required appropriately targeted preventive and corrective policies in the domain of other policymakers.

4.2. Safeguards for the European Financial System

Following the global financial crisis, a new prudential financial architecture was established at the European level to enhance the resilience of financial intermediaries, reduce the risk of volatile financial markets, secure the stability of financial infrastructures and promote a well-functioning integrated euro area financial system. The reinforced regulatory and supervisory framework for financial stability in Europe seeks inter alia to more effectively counter excessive leverage and a mispricing of risk. Although not set up for that purpose, it thus also has the capacity to contain the systemic financial risks from a long-lasting monetary expansion and an ample supply of low-cost credit (see (Van Riet 2017)).

The European Banking Authority (EBA), the European Insurance and Pensions Authority (EIOPA) and the European Securities Markets Authority (ESMA) have functioned since 2011 as coordinators of national micro-supervisory activities for banks, institutional investors and securities markets, respectively. As from November 2014, the ECB was put in charge of the Single Supervisory Mechanism with the objective to protect the safety and soundness of euro area banks and the banking system. This new micro-prudential supervision function was legally separated from its monetary policy function in order to prevent conflicts of interest. Under its new capacity, the ECB actively cooperates with the EBA and the national banking supervisors in promoting the banking sector’s resilience to shocks.

Many euro area banks were struggling with new regulatory requirements, a crisis legacy of non-performing loans and competitive pressures, both from other banks and non-banks, while the sluggish economy held back the demand for loans and income growth. The euro area banking industry was therefore called upon to remove excess capacity, strengthen its equity base, tackle the legacy of bad loans, achieve greater cost efficiency and make its business model viable in the new steady-state of tighter regulation, more subdued output growth and lower interest rates. For example, following macro-financial stress tests in 2014 and 2016, the Supervisory Board of the ECB urged a few large credit institutions to strengthen their balance sheets by raising capital buffers.

The profitability and solvency of institutional investors were equally challenged by ultra-low interest rates. Already in 2013, EIOPA therefore issued recommendations to national micro-prudential authorities to strengthen their oversight of the industry. Among other factors, regular stress tests considered the impact of sustained low interest rates on the balance sheet of occupational pension funds and insurance companies (Bernardino 2016). National regulators specified the remedial actions to be taken, but also allowed some flexibility with regard to the discount rate to be used for valuing liabilities and extended the usual deadlines for redressing a shortfall compared to available assets.

Beyond banking supervision, the ECB contributes to the work of the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), an independent body tasked with the macro-prudential oversight of the EU financial system. The ESRB is a forum for cooperation among institutions that contribute to preserving financial stability across Europe and carries out a regular forward-looking analysis of system-wide risks, including those arising from low interest rates (see (ESRB 2016a)). In November 2016, the ESRB issued official warnings to the governments of Austria, Belgium, Finland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands (and three EU countries outside the euro area) pointing to vulnerabilities in their residential real estate sectors that could disrupt financial stability over the medium term with negative economic repercussions (ESRB 2016b). The national competent authorities dispose of a new suite of macro-prudential tools to contain the financial stability risks arising in the banking sector16; and the ECB can top them up if warranted.

4.3. The Contribution of National Fiscal and Structural Policies

Finally, to relieve the burden on the single monetary policy, the ECB repeatedly urged for the 19 euro area governments to put in place an aggregate macroeconomic policy mix that was more appropriately attuned to the cyclical and structural needs of EMU (Draghi 2014). Member countries with fiscal space could add a budgetary expansion to the central bank’s monetary stimulus so as to more effectively remove the slack in the euro area economy, while those without budgetary room for maneuver should first restore sustainable public finances in line with the requirements of the SGP. The euro area fiscal stance turned expansionary in 2015 to 2016 and was more aligned with the orientation of monetary policy. However, the composition across countries was suboptimal; some contributed less to euro area stabilization then was feasible, whereas others lacked the fiscal space and still postponed consolidation. A euro area fiscal capacity would have been more conducive to achieving fiscal policy goals at the euro area level.

Governments could also facilitate the task of the central bank by raising the quality of public finances (focusing more on public investment and tax efficiency) and facilitating public-private financing of EU investment projects. In addition, they could initiate more decisive structural reforms in labor, product and housing markets and a faster resolution of non-performing bank loans and corporate insolvencies to enhance flexibility, competitiveness, deleveraging and the business environment. Although some of these structural measures could involve fiscal costs and dampen domestic demand in the short run, they were vital to reverse the euro area’s declining trend of productivity growth and raise the longer term return on capital (see also (Bindseil et al. 2015)). Such structural policy actions could also improve the operation of the monetary transmission mechanism and enhance the efficacy of monetary policy (Van Riet 2006).

These national contributions to the euro area macroeconomic policy mix would support the ECB in meeting its price stability objective and thereby reduce the need for prolonging or adding ”experimental” monetary policy measures in unknown territory. Although the institutional architecture of EMU does not foresee explicit monetary-fiscal-structural policy coordination, the national governments have a shared responsibility to support the ECB’s fight against low inflation.

5. Conclusions

After the euro area crisis had subsided, the Governing Council of the ECB still faced a series of complex and evolving monetary policy challenges. As market volatility abated, but deflationary pressures emerged, the main task as from June 2014 became to design a sufficiently strong monetary stimulus that could reach market segments that were deprived of credit at reasonable costs and to counter the risk of a too prolonged period of low inflation.

Looking back over the 2½ years since June 2014, the ECB exploited the narrow room to maneuver for standard interest rate policy by bringing the main refinancing rate down to zero and applying a mildly negative interest rate on its deposit facility. At the same time, it took non-standard monetary stimulus measures in the form of targeted longer term refinancing operations and large-scale asset purchases. Alongside these concrete actions, the ECB consistently signaled its intention to maintain an expansionary monetary stance for as long as necessary.

As a result, the sovereign yield curve was brought down, even reaching negative territory up to medium-term tenors, with significant spill-over effects to other asset markets. Following the widespread relaxation of financing conditions, the flow of bank-based and market-based credit to the euro area economy turned positive again while broad money growth stabilized at a more appropriate higher level. This substantial monetary easing was instrumental in preventing deflationary forces from taking hold and generating a moderate, but firming recovery of output growth and inflation.