Purchasing Power Parity in Transition Countries: Panel Stationary Test with Smooth and Sharp Breaks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Data

3. Methodology

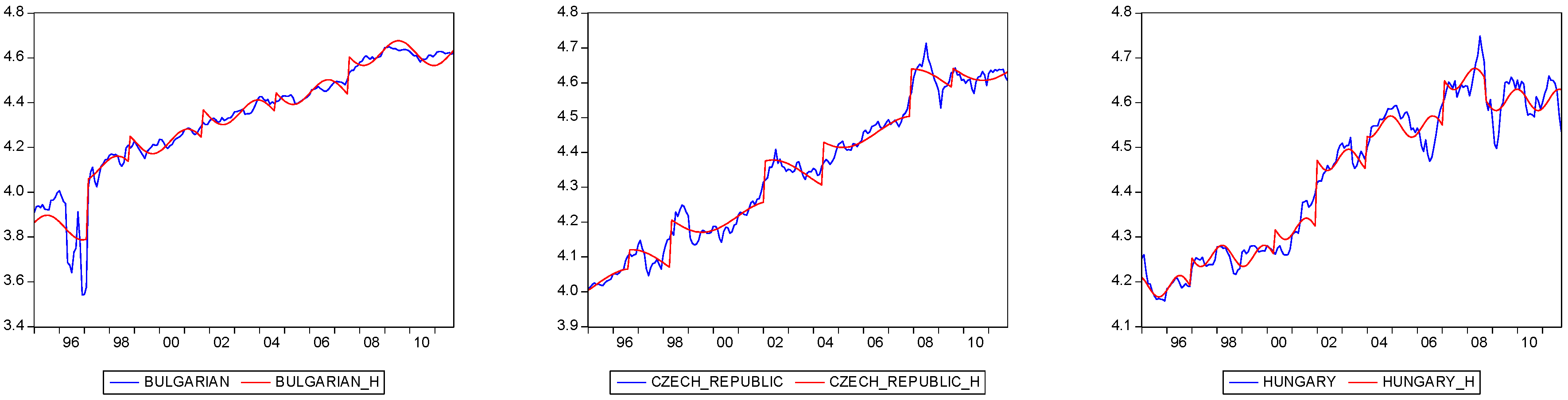

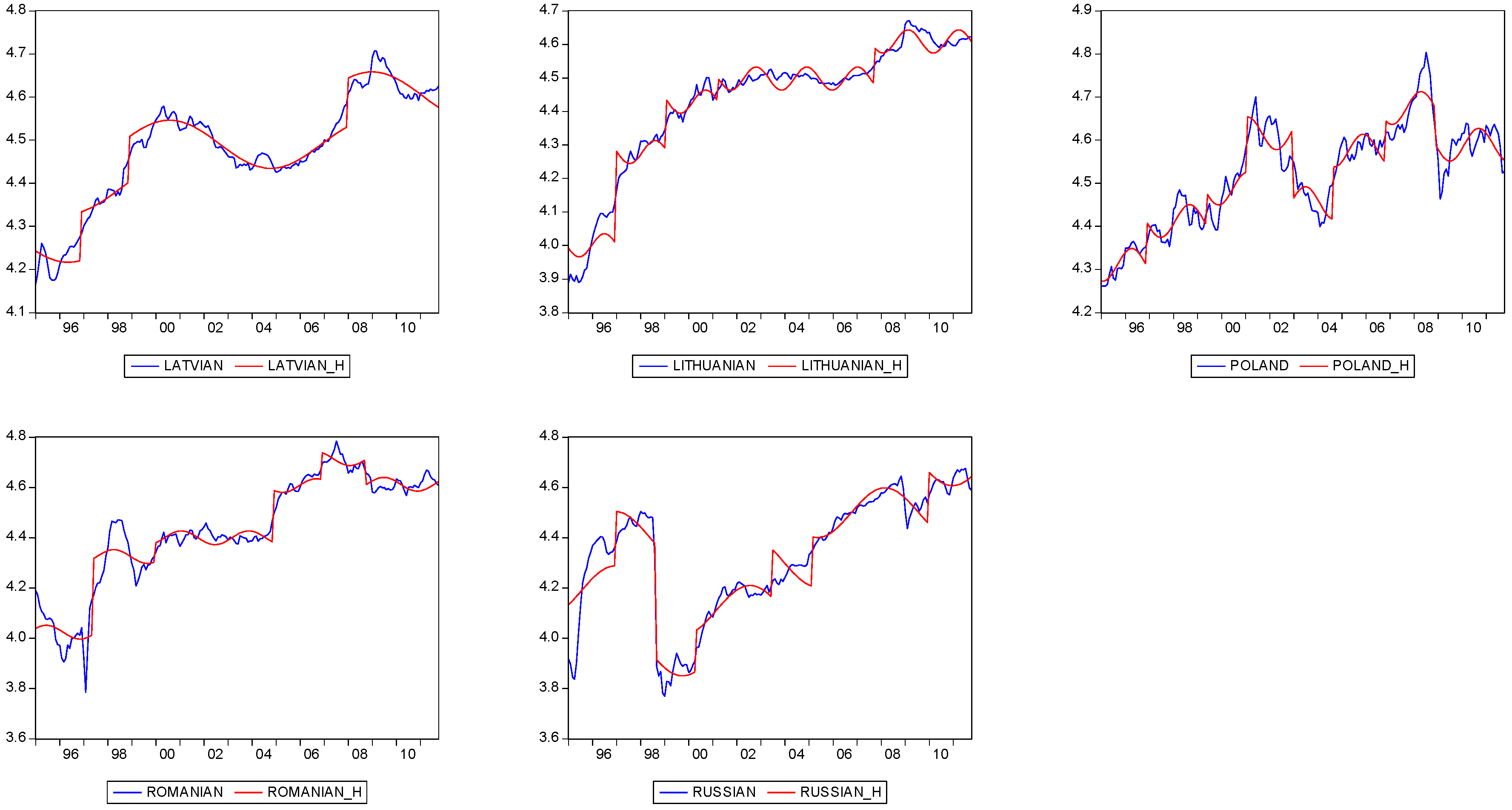

4. Empirical Results and Policy Implications

| Countries | Level | 1st Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADF | PP | KPSS | ADF | PP | KPSS | |

| Bulgarian | −0.884(4) | −2.406(4) | 1.597[11] *** | −10.11(1) *** | −41.03(4) *** | 0.095[3] |

| Czech Republic | −0.742(0) | −0.742(1) | 1.485[11] *** | −13.48(0) *** | −13.47(2) *** | 0.087[1] |

| Hungary | −0.902(0) | −0.856(2) | 1.366[11] *** | −14.10(0) *** | −14.12(2) *** | 0.146[3] |

| Latvian | −1.497(0) | −1.505(4) | 1.529[11] *** | −14.01(0) *** | −14.01(1) *** | 0.107[3] |

| Lithuanian | −2.3337(0) | −2.156(4) | 1.680[11] *** | −12.78(0) *** | −12.82(4) *** | 0.321[5] |

| Poland | −1.734(0) | −1.746(1) | 1.405[11] *** | −12.44(0) *** | −14.01(2) *** | 0.042[2] |

| Romanian | −1.421(3) | −1.344(7) | 1.467[11] *** | −6.11(2) *** | −10.73(5) *** | 0.205[7] |

| Russian | −1.198(0) | −1.550(7) | 0.875[11] *** | −11.25(0) *** | −11.46(6) *** | 0.077[7] |

| Panel A: Panel Stationary Test | |||||||

| Pesaran (2004) is cross-sectional dependence test | Test | p-Values | |||||

| 31.568 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Panel stationary test | Test | Critical values | |||||

| 90 | 95 | 97.5 | 99 | ||||

| Homogenous long-run variance | 2.648 | 1.386 | 2.212 | 2.993 | 4.084 | ||

| Heterogeneous long-run variance | 3.436 | 1.122 | 1.587 | 2.035 | 2.612 | ||

| Panel B: Univariate Stationary Test | |||||||

| Countries | Bartlett | 90% | 95% | 97.5% | 99% | ||

| Bulgarian | 0.0787 | 0.0741 | 0.0913 | 0.1073 | 0.1330 | ||

| Czech Rep. | 0.0421 | 0.0371 | 0.0425 | 0.0483 | 0.0545 | ||

| Hungary | 0.0481 | 0.0447 | 0.0516 | 0.0579 | 0.0698 | ||

| Latvian | 0.0471 | 0.0348 | 0.0401 | 0.0456 | 0.0534 | ||

| Lithuanian | 0.0471 | 0.0688 | 0.0836 | 0.0999 | 0.1160 | ||

| Poland | 0.0336 | 0.0339 | 0.0385 | 0.0436 | 0.0502 | ||

| Romanian | 0.0683 | 0.0349 | 0.0461 | 0.0540 | 0.0637 | ||

| Russian | 0.0486 | 0.0344 | 0.0387 | 0.0437 | 0.0491 | ||

| Panel A: The Results for Optimum Frequency and the F-Statistic and Its Critical Values | ||||||

| Countries | Optimum Frequency | F stat | 90% | 95% | 97.50% | 99% |

| Bulgarian | 5 | 23.805 | 2.005 | 2,797 | 2.999 | 3.031 |

| Czech Rep. | 8 | 22.203 | 2.196 | 2.598 | 2.995 | 3.442 |

| Hungary | 10 | 36.323 | 2.488 | 3.245 | 3.714 | 4.091 |

| Latvian | 4 | 33.934 | 1.941 | 2.693 | 3.716 | 3.951 |

| Lithuanian | 9 | 18.421 | 1.744 | 2.202 | 3.025 | 8.811 |

| Poland | 1 | 72.492 | 3.084 | 4.617 | 4.800 | 5.245 |

| Romanian | 8 | 35.406 | 2.300 | 2.540 | 3.215 | 3.407 |

| Russian | 6 | 62.527 | 2.135 | 2.375 | 3.374 | 4.601 |

| Panel B: The Results for Sharp Drift Dates in Equation (3) | ||||||

| Countries | Break Dates | |||||

| Bulgarian | 02-1997 | 11-2001 | 10-2005 | |||

| Czech Rep. | 02-1997 | 03-1999 | 01-2002 | 10-2003 | 04-2006 | 01-2008 |

| Hungary | 06-1997 | 06-1999 | 04-2001 | 10-2002 | 03-2004 | |

| Latvian | 09-1996 | 10-1996 | 06-2001 | 12-2002 | 02-2004 | 10-2005 |

| Lithuanian | 09-1996 | 06-2001 | 02-2002 | 10-2004 | ||

| Poland | 01-2000 | 08-2001 | 10-2002 | 03-2004 | 11-2005 | |

| Romanian | 12-1996 | 12-1998 | 08-1999 | 04-2000 | 05-2004 | 11-2006 |

| Russian | 12-1996 | 06-1998 | 06-1999 | 02-2001 | 12-2003 | 03-2005 |

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Bahmani-Oskooee, and S. Hegerty. “Purchasing power parity in less-developed and transition economies: A review article.” J. Econ. Surv. 23 (2009): 617–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K.S. Im, M.H. Pesaran, and Y. Shin. “Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels.” J. Econom. 115 (2005): 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Enders, and J. Lee. “A unit root test using a Fourier series to approximate smooth breaks.” Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 74 (2012): 574–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Bahmani-Oskooee, T. Chang, and T. Wu. “Revisiting purchasing power parity in African countries: Panel stationary test with sharp and smooth breaks.” Appl. Financ. Econ. 24 (2014): 1429–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Enders, and M.T. Holt. “Sharp breaks or smooth shifts? An investigation of the evolution of primary commodity prices.” Am. J. Agric. Econ. 94 (2012): 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Bai, and P. Perron. “Estimating and testing linear models with multiple structural changes.” Econometrica 66 (1998): 47–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.L. Carrión-i-Silvestre, and A. Sansó. “A guide to the computation of stationarity tests.” Empir. Econ. 31 (2006): 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Kwiatkowski, P.C.B. Phillips, P. Schmidt, and Y. Shin. “Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root: How sure are we that economic time series have a unit root? ” J. Econom. 54 (1992): 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.E. Rapach, and M.E. Wohar. “Testing the monetary model of exchange rate determination: A closer look at panels.” J. Int. Money Financ. 23 (2004): 867–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Beko, and D. Borsic. “Purchasing power parit y in transition economics.” Post-Communist Econ. 19 (2007): 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.Z. Baharumshah, and D. Borsic. “Purchasing power parity in Central and Eastern European countries.” Econ. Bull. 6 (2008): 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- P. Perron. “The great crash, the oil price shock, and the unit root hypothesis.” Econometrica 55 (1989): 277–302. [Google Scholar]

- W. Newey, and K. West. “Automatic lag selection in covariance matrix estimation.” Rev. Econ. Stud. 61 (1994): 631–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F.W. Ahking. “Testing long-run purchasing power parity with a Bayesian unit root approach: The experience of Canada in the 1950s.” Appl. Econ. 29 (1997): 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Apergis. “Budget deficits and exchange rates: Further evidence from cointegration and causality Tests.” J. Econ. Stud. 25 (1998): 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.C. Arize, J. Malindretos, and S. Christoffersen. “Monetary dynamics, exchange rates and Parameter Instability: An empirical investigation.” J. Econ. Stud. 30 (2002): 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Baffoe-Bonnie. “Dynamic modelling of faiscal and exchange rates policy effects in a developing country: A non-structural approach.” J. Econ. Stud. 31 (2004): 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.D. Beach, N.C. Kruse, and N.D. Uri. “The doctrine of relative purchasing power parity re-examined.” J. Econ. Stud. 20 (1993): 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Bleaney. “Does Long-run purchasing-power parity hold within the European Monetary System? ” J. Econ. Stud. 19 (1992): 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Bwo-Nung. “Long-run purchasing power parity revisited: A Monte Carlo simulation.” Appl. Econ. 28 (1996): 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.I. Carrion-I-Silvestre, T. del Barrio, and E. Lopez-Bazo. “Evidence on the purchasing power parity in a panel of cities.” Appl. Econ. 36 (2004): 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Enders, and K. Chumrusphonlert. “Threshold Cointegration and Purchasing Power Parity in the Pacific Nations.” Appl. Econ. 36 (2004): 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.E. Hojman. “Fundamental equilibrium exchange rates under contractionary devaluation: A peruvian model.” J. Econ. Stud. 16 (1989): 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.J. Holmes. “Exchange rate regimes and economic convergence in the European Union.” J. Econ. Stud. 29 (2002): 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Horne. “Eight conjectures about exchange rates.” J. Econ. Stud. 31 (2004): 524–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.A. Jenkins. “Purchasing power parity and the role of traded goods: Evidence from EU States.” Appl. Econ. 36 (2004): 1371–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Jung. “Forecasting of foreign exchange rate by normal mixture models.” J. Econ. Stud. 22 (1995): 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Macdonals. “Purchasing power parity-evidence from a new panel test.” Appl. Econ. 34 (2002): 1319–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I.A. Moosa. “Testing proportionality, symmetry and exclusiveness in long-run PPP.” J. Econ. Stud. 21 (1994): 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.M. Nachane. “Purchasing power parity: An analysis based on the evolutionary spectrum.” Appl. Econ. 29 (1997): 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P.K. Narayan. “New evidence on purchasing power parity from 17 OECD countries.” Appl. Econ. 37 (2005): 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.A. Peel, and I.A. Venetis. “Purchasing power parity over two centuries: Trends and nonlinearity.” Appl. Econ. 35 (2003): 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Sjolander. “Unreal exchange rates: A simulation based approach to adjust misleading PPP estimates.” J. Econ. Stud. 34 (2007): 256–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.P. Taylor. “An empirical examination of long-run purchasing power parity using cointegration technique.” Appl. Econ. 20 (1988): 1369–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.P. Taylor, D.A. Peel, and L. Sarno. “Nonlinear mean-reversion in real exchange rates: Toward a solution to the purchasing power parity puzzles.” Int. Econ. Rev. 42 (2001): 1015–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1Enders and Holt [5] is the first study that discusses sharp breaks or smooth shifts in investigating the evolution of primary commodity prices.

- 2The null hypothesis is that data are stationary, and the alternative hypothesis is that data are non-stationary.

- 3Following Rapach and Wohar [9], we calculate the half-life of a shock for each country, and it is based on using the cumulative impulse response function. We classify transition countries according to their half-lives into two groups; countries with a half-life less than one year (first group) and countries with a half-life less than two years (second group). The results of the half-life show that a shock to the real exchange rate of Bulgaria will dissipate by one-half in about 7.89 months. A shock to real exchange rates of the rest of the seven countries (i.e., Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Russia) require a time period of 20 months for dissipating by one-half. Calculation of confidence intervals for the half-life shows that the confidence intervals are very wide for the half-life of all eight countries. The results show a high degree of persistence in the real exchange rate series.

- 4Maximum number of breaks and frequencies are fixed at 10 for each country. The optimum frequency and drift dates are reported in Table 3.

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bahmani-Oskooee, M.; Chang, T.; Wu, T.-P. Purchasing Power Parity in Transition Countries: Panel Stationary Test with Smooth and Sharp Breaks. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2015, 3, 153-161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs3020153

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Chang T, Wu T-P. Purchasing Power Parity in Transition Countries: Panel Stationary Test with Smooth and Sharp Breaks. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2015; 3(2):153-161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs3020153

Chicago/Turabian StyleBahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, Tsangyao Chang, and Tsung-Pao Wu. 2015. "Purchasing Power Parity in Transition Countries: Panel Stationary Test with Smooth and Sharp Breaks" International Journal of Financial Studies 3, no. 2: 153-161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs3020153

APA StyleBahmani-Oskooee, M., Chang, T., & Wu, T.-P. (2015). Purchasing Power Parity in Transition Countries: Panel Stationary Test with Smooth and Sharp Breaks. International Journal of Financial Studies, 3(2), 153-161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs3020153