Abstract

Credibility is the bedrock of any crisis stress test. The use of stress tests to manage systemic risk was introduced by the U.S. authorities in 2009 in the form of the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program. Since then, supervisory authorities in other jurisdictions have also conducted similar exercises. In some of those cases, the design and implementation of certain elements of the framework have been criticized for their lack of credibility. This paper proposes a set of guidelines for constructing an effective crisis stress test. It combines financial markets impact studies of previous exercises with relevant case study information gleaned from those experiences to identify the key elements and to formulate their appropriate design. Pertinent concepts, issues and nuances particular to crisis stress testing are also discussed. The findings may be useful for country authorities seeking to include stress tests in their crisis management arsenal, as well as for the design of crisis programs.

Keywords:

asset quality review; financial backstop; hurdle rates; restructuring; solvency; transparency; EBA; PCAR; SCAP “Investors don’t like uncertainty. When there’s uncertainty, they always think there’s another shoe to fall.”Kenneth Lay, then-CEO of Enron Corp.20 August 2001

1. Introduction

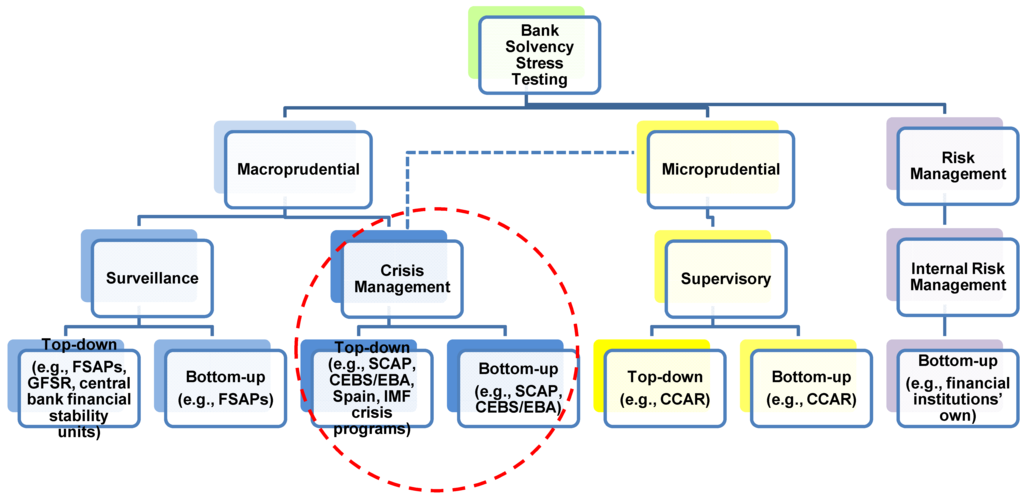

Stress tests have become the “new normal” in financial crisis management. They are increasingly being used by country authorities as an instrument for regaining the public’s trust in the banking system during the current global financial crisis. This new tool, known as a “crisis stress test,” is essentially a supervisory exercise accompanied by detailed public disclosure to remove widespread uncertainty about banks’ balance sheets and the authorities’ plans for those banks. Put another way, the crisis stress test is a microprudential exercise with macroprudential objectives (Figure 1). In this regard, transparency, and hence the quality of disclosure, is critical.

The concept of crisis stress testing was introduced by the U.S. authorities in early-2009 in the form of the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (SCAP). The solvency stress testing exercise took place during the darkest days of the sub-prime loans meltdown, following a sharp loss of confidence in U.S. banks and an unprecedented decimation of their market value. The announcement of the SCAP itself was initially met with trepidation and skepticism by markets, but official clarifications surrounding the event about the aim of the exercise, the availability of a financial backstop and the subsequent publication of the methodology and results appeared to reassure markets (see Peristiani et al. [1]).

The SCAP represented a high-profile adoption of forward-looking techniques of stress testing which assessed the preparedness of the banks (and authorities) to deal with low-probability, high-impact events. The subsequent findings revealed that the capital needs of the largest U.S. banks at the time would be manageable even if a more adverse scenario were to materialize (see Tarullo [2]). Investor sentiment rebounded and stabilized, and the assessed banks were able to add more than $200 billion in common equity in the following 12 months. The U.S. supervisors have since followed up on the SCAP with publicized supervisory stress tests in the form of the Comprehensive Capital Assessment Program (CCAR) and also under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (DFA) framework.

A crisis stress test conducted by supervisors should not be confused with a supervisory stress test undertaken during a crisis. Both types of stress tests may be used for similar purposes, i.e., to: (i) determine a needed capital buffer over current solvency levels; (ii) differentiate the soundness of banks in the system as part of triage analysis; and/or (iii) quantify potential fiscal costs, depending on the magnitude of the projected shortfalls and the urgency of any required recapitalization. However, supervisory stress tests in crisis situations may be different from crisis stress tests in that: (i) the focus of the former may be to assess the condition of individual banks solely for microprudential rather than for macroprudential or system-wide stability purposes (see IMF [3]) and (ii) the former typically do not have the same degree of (public) transparency and indeed, may have to be kept confidential to avoid potentially unleashing an unmanageable backlash if the key elements necessary for publication—which we will discuss in much of this paper—are not in place.

Clearly, crisis stress tests must be credible to be successful. As in the United States, supervisory authorities in Europe have also used crisis stress tests for systemic risk management but with varying degrees of effectiveness to date. This suggests that the design of such exercises matter significantly, notably:

- The governance of the tests (i.e., the stress tester and the overseer) must be perceived to be independent, with the requisite technical expertise.

- The stress tests themselves must be sufficiently stringent yet plausible. The scope, coverage, scenario design and methodology need to be considered sufficiently comprehensive and robust to capture key risks to the institutions and system.

- The stress tests should be simultaneous, consistent and comparable cross-firm assessments to enable a broader analysis of risks and an evaluation of estimates for individual institutions (Tarullo [2]). From a macroprudential perspective, they should allow for a better understanding of inter-relationships across institutions.

- The stress tests should usefully inform markets about the risks associated with the banks, and the results must be sufficiently granular such that there is clear differentiation among institutions in the first instance, to guide subsequent actions.

- Last but not least, the manner in which the stress test results will be backstopped or used must be clarified early on to guide depositors and investors.

Crisis stress tests should be seen as one element of an overall strategy to rebuild public confidence in a banking system. Ideally, such a strategy should include (i) containment; (ii) diagnostics (asset quality review (AQR), data integrity and verification (DIV), stress test); and (iii) restructuring or exit. Within the diagnostics component, the stress test itself is a forward-looking tool for determining a capital buffer against further deterioration in the real economy. As we discuss later in this paper, the preceding AQR and DIV of banks’ portfolios are critical for credibility as they help to ensure that the data used in the stress test are “clean”. However, the nature and extent of these exercises may differ depending on market perceptions of the reliability of the reported information and the design of the stress test.

In some cases, the restoration of the credibility of financial supervisors and regulators is another element in rebuilding public confidence. Indeed, this aspect of regaining the public’s trust in the financial system is at least as, if not more important than just shedding light on the conditions of banks themselves. In the ensuing discussion, we show how perceptions of the credibility of supervisory and regulatory authorities could influence the design of key aspects of a crisis stress test.

The assessment by the Turkish authorities of its banking sector following the 2001 crisis is an example of a public diagnostic exercise which helped to restore confidence in the banking sector and its supervisor and regulator. Although it did not include a forward-looking stress test component, its overall objective and design included the necessary attributes for a credible outcome. The financial status of all domestic banks was assessed using improved accounting standards and a three-stage audit procedure, the first two of which were by independent auditors. The capital adequacy of each bank was determined and banks that were undercapitalized were required to take capital action. A financial backstop through the State Recapitalization Scheme was made available to banks that were deemed solvent, but which were unable to raise the necessary capital. The objective, method and implementation details of the exercise were published (see Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency (BRSA) [4]), as were the findings and progress on actions taken (BRSA [5]).

This paper focuses on the design of crisis stress tests, leaving the comprehensive study of other aspects of a diagnostic to future research. Work on developing a comprehensive framework for an effective crisis stress test has been limited to date. Hirtle et al. [6] draw lessons from the SCAP in analyzing the complementarities between macroprudential and microprudential supervision. Schuermann [7] explores in some detail the design of stress scenarios and their application in terms of modeling losses, revenues and balance sheets—key elements in macro stress testing—in the U.S., EU and Republic of Ireland (“Ireland”) exercises. He also examines the disclosure strategies across the various exercises. Elsewhere, Langley [8] assesses more broadly the “anticipatory techniques” applied in the SCAP and their performative power vis-à-vis those applied in the European exercises. Other empirical and policy-related literature in this area has largely focused on the effectiveness of the SCAP (Bernanke [9]; Matsakh et al. [10]; Peristiani et al. [1]; Tarullo [2]), with some coverage of the European stress tests (Onado and Resti [11]).

The specific objective of this paper is to formulate guidelines for designing a crisis solvency stress test, based on lessons learned from previous experiences. Although a crisis stress testing exercise may cover either solvency or liquidity risk or both, we focus on the former in this paper. In this regard, our study complements the work done by Hirtle et al. [6] and Schuermann [7]. We employ various methodologies in our analysis:

- We first distinguish the effective crisis stress tests using financial market impact studies of recent exercises in the United States, the European Union, Ireland and Spain, including analyzing the statistical performance of the respective financials stock indices and sovereign credit default swap (CDS) spreads around the announcement of the stress test results.

- Next, we apply case study analysis to identify the key elements of a crisis stress test and to formulate the appropriate design of those elements, drawing on qualitative information from previous stress tests.

- Where relevant, we juxtapose our analysis against some of the relevant “best practice” principles presented in the literature (e.g., Basel Committee for Banking Supervision (BCBS) [12]; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve/Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation/Office of the Comptroller of the Currency [13]; IMF [3]), while highlighting concepts, issues and nuances that may be particular to crisis stress testing.

Our conclusions point to an immutable fact, which is that crisis stress tests are not for the half-hearted. Ideally, the stress test should take place sufficiently early to address any crisis of confidence in the banking system and have a clearly-specified objective. Moreover, lessons learned from past experiences show that country authorities must be fully committed if they are to undertake such an exercise, lest it backfires. The authorities must be prepared to conduct a thorough, honest and transparent examination of their banking system and resolve to take appropriate follow-up action(s) on the results with the necessary resources to back them, if the exercise is to serve its purpose. Supporting activities such as AQRs and possibly follow-up stress tests are necessary to ensure the credibility of crisis stress tests. However, political economy considerations could also play an important role in the design of crisis stress tests, given the potential implications of the results for public confidence and the fiscal purse. We suggest that our findings may be useful for authorities seeking to undertake stress tests for systemic risk management and for the design of financial crisis programs.

Our paper is organized as follows. Section 2 details the relevant case studies of stress testing exercises conducted in the United States and Europe, as well as the market data used in the initial impact study. Section 3 discusses the metrics used for defining the effectiveness of those crisis stress tests and presents the empirical analysis. Section 4 draws on those findings and the qualitative information gleaned from the case studies to identify the key stress test elements and to formulate their design. A sidebar comparing the differences between bank restructuring costs and loss estimates from crisis stress tests is presented in Section 5. Section 6 concludes.

2. The Data

Our analysis draws on four case studies covering seven crisis stress tests. The tests were conducted in the United States, the European Union, Ireland and Spain between 2009 and 2012 (Table 1). The details of the individual exercises are sourced from the respective authorities, namely, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve (Fed), the European Banking Association (EBA) and its predecessor, the Committee of European Banking Supervisors (CEBS), the Central Bank of Ireland (CBI) and Banco de España (BdE).

The CEBS had noted that its stress tests contrasted with the crisis stress test nature of the SCAP. The EU authority had stated that the objective of its exercise was to “provide policy information for the assessment by individual Member States of the resilience of the EU banking sector as a whole and of the banks participating in the exercise”, compared to the SCAP, which was linked to “determining the individual capital needs of banks” (CEBS [14]); however, the CEBS’ overt efforts at transparency to reassure markets—including through the announcement of aggregate results in the 2009 exercise—have been consistent with the macroprudential application of crisis stress tests.

We first identify successful crisis exercises by analyzing the performance of market indicators, consistent with existing studies. Previous research had examined the behavior of stock prices of individual U.S. banks post-SCAP (Matsakh et al. [10]; Peristiani et al. [1]) as well as the sovereign CDS spreads (Peristiani et al. [1]; Schuermann [7]) to determine the effectiveness of the respective crisis stress tests. Here:

- We study the financials stock price indices for each jurisdiction as proxies for the market’s assessment of the soundness of the respective banking systems. Stock prices represent a bellwether indicator for market confidence in that shareholders are the “first loss” investors and the evidence shows that they respond very quickly to incorporate all relevant publicly available information in their pricing (Fama [15]).

- We also consider the behavior of sovereign CDS spreads around the stress testing exercises and related events. Sovereign CDS spreads provide an indication of the perceived creditworthiness of a country, which is considered closely linked to the health of its banking sector given the potential implications for the public purse if government support is required (Mody and Sandri [16]). In several banking systems, the high holdings of sovereign debt have focused market concerns on the bank-sovereign feedback loop (Acharya et al. [17]; Committee on the Global Financial System [18]; Angeloni and Wolff [19]; Darraq Paries et al. [20]).

All market data used in this study are sourced from Bloomberg (Table 2). It should also be noted that caveats apply to the use of financial markets indicators to define the effectiveness of the stress tests in that they may also be influenced by other concurrent events which we do not isolate in this study.

Figure 1.

Solvency Stress Testing Applications.

Table 1.

Case Studies: Crisis Stress Tests.

| Jurisdiction | Stress Testing Exercise | Stress Tester | Participating Authorities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Supervisory Capital Assessment and Program 2009 | Authorities | Federal Reserve (Fed), Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), Office of the Comptroller of Currency (OCC) | |||

| European Union | Committee of European Banking Supervisors (CEBS) 2009 | Authorities | National supervisory authorities, CEBS, European Commission (EC) and European Central Bank (ECB) | |||

| Committee of European Banking Supervisors 2010 | Authorities | National supervisory authorities, CEBS, EC and ECB | ||||

| European Banking Authority (EBA) 2011 | Authorities | National supervisory authorities, EBA, EC, ECB and European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) | ||||

| Ireland | Prudential Capital Assessment and Review (PCAR) 2011 | Authorities with loan loss inputs from BlackRock Solutions | Central Bank of Ireland (CBI) | |||

| Spain | Top-down (TD) 2012 | Oliver Wyman and Roland Berger | Banco de España (BdE), Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MEC), the Troika and representatives from two EU countries | |||

| "Bottom-up" (BU) 2012 | Oliver Wyman | BdE, MEC, the Troika and EBA | ||||

Sources: Fed; CBI; EBA; and BdE.

Table 2.

Market Data: Financials Stock Price Index and CDS Spreads.

| Jurisdiction | Stock Market | Credit Default Swaps | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proxy Index | Bloomberg Ticker | Proxy Index | Bloomberg Ticker | |||||

| United States | S&P 500 Financials Sector Index | S5FINL [Index] | United States EUR senior 5-year | ZCTO CDS EUR SR 5Y [Corp] | ||||

| European Union | STOXX Europe 600 Banks Price EUR | SX7P [Index] | iTraxx SovX Western Europe USD 5-year | SOVWE CDSI GENERIC 5Y [Corp] | ||||

| Ireland | Irish Stock Exchange Financial Index | ISEF [Index] | Ireland USD senior 5-year | IRELND CDS USD SR 5Y [Corp] | ||||

| Spain | MSCI Spain Financials Index | MSES0FN [Index] | Spain USD senior 5-year | SPAIN CDS USD SR 5Y [Corp] | ||||

Source: Bloomberg.

Table 3.

Crisis (and Follow-up) Stress Tests: Performance Statistics 1/.

| Indicator | Effectiveness of Stress Test | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Measure | United States | European Union | Ireland | Spain | ||||||||||||||||||

| Crisis | Supervisory | Crisis | Crisis | Surveillance | Crisis | ||||||||||||||||||

| SCAP 2009 | CCAR 2011 | CCAR 2012 | CCAR & DFA 2013 | CEBS 2009 | CEBS 2010 | EBA 2011 | PCAR 2011 + IMF 2/ | FSAP 2012 3/ | TD 2012 | BU 2012 | |||||||||||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| Financials stock index | Index return

(160-day, in percent) | −13.7 | 19.1 | 11.4 | −20.5 | 24.0 | 1.5 | 17.3 | 8.9 | 63.4 | −1.7 | −0.3 | 2.3 | −19.5 | −21.7 | −67.2 | 78.9 | −24.4 | 21.8 | −21.4 | 23.8 | −1.8 | −5.6 |

| Return volatility

(160-day, in percent) | 6.4 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 1.7 | |

| Credit default swap | Spread

(160-day, in basis points) | −6 | −7 | −4 | 8 | −19 | 4 | 2 | −14 | n.a. | 33 | 43 | 52 | 104 | 67 | 204 | −193 | 161 | −284 | 184 | −288 | −44 | −90 |

Sources: Bloomberg; and authors’ calculations; 1/ Relative to announcement of stress test results; 2/ The publication of the IMF’s Third Review in September 2011 indicating that the outcomes of the PCAR were being incorporated into banks’ recapitalization and restructuring plans helped provide credibility to the exercise; 3/ Included for completeness only—not intended as a crisis stress test; surveillance stress testing exercise was conducted in a crisis environment.

3. Identifying the Successful Crisis Stress Tests

We apply a simple event study-type methodology for determining the effectiveness of a crisis stress test. Given that our analytical framework is not strictly that of a formal event study, we shall refer to our assessment as an “impact study.” We classify a stress test as successful if it has been able to stabilize or improve investor sentiment towards the banking system for at least six months after the results are announced, providing sufficient time for follow-up action(s) to be taken. In other words, the stress test is considered to have achieved its objective if it has been able to establish a “floor” for the market during this period (Table 3), such that:

- The return on the financials stock index is relatively stable or rises in the six months following the announcement of the test results.

- The volatility of daily returns (calculated as the standard deviation over 130 days) stabilizes or declines in the six months following the announcement of the test results, relative to the preceding six months.

- The sovereign CDS spread stabilizes or narrows in the six months following the announcement of the test results.

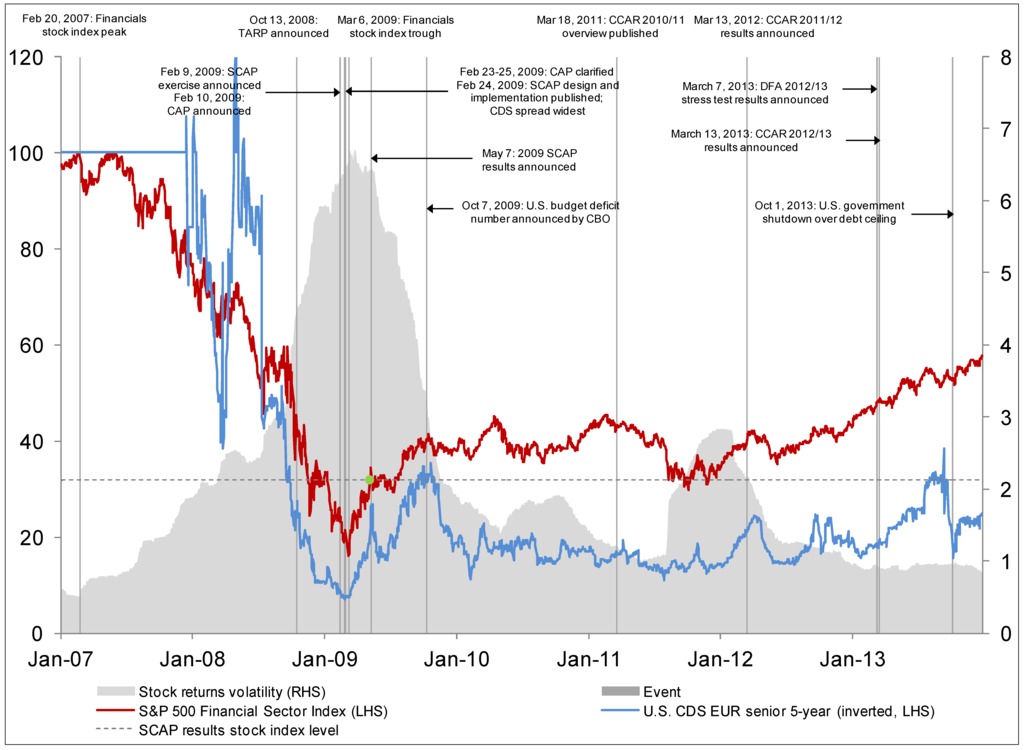

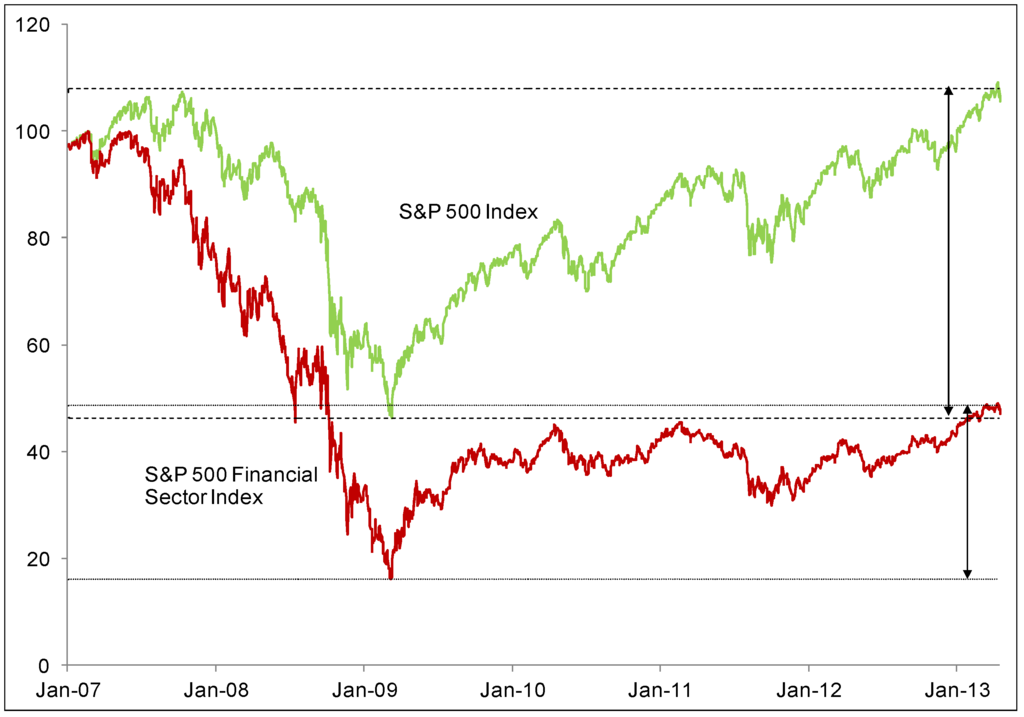

In this context, the empirical evidence from the U.S. SCAP shows that the exercise had been successful in achieving its aim (Figure 2):

- The release of the SCAP results effectively halted and then reversed the 2-year slide in investor confidence towards the country’s banks. The financials index rose by almost 20 percent in the following six months. At the same time, market volatility—which had peaked just prior to the exercise—declined sharply over this period. Since then, the S&P 500 Financial Sector Index has largely remained above the level established by the SCAP results, although it flirted with that floor during the more volatile period in 2012 Q3.

- U.S. firms have substantially increased their capital since the SCAP. The weighted Tier 1 (T1) Common Equity ratio of the 18 bank holding companies that were in the SCAP sample has more than doubled from an average 5.6 percent at the end of 2008 to 11.3 percent in 2012 Q4, reflecting an increase in T1 Common Equity from $393 billion to $792 billion during the same period.

- U.S. CDS spreads narrowed in tandem with the improvement in the financials index during the SCAP period. However, they subsequently dissociated from developments in the banking sector in September 2011 as markets turned their attention to the fiscal deficit after the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) announced that the U.S. budget deficit had reached its widest as a percentage of GDP since 1945.

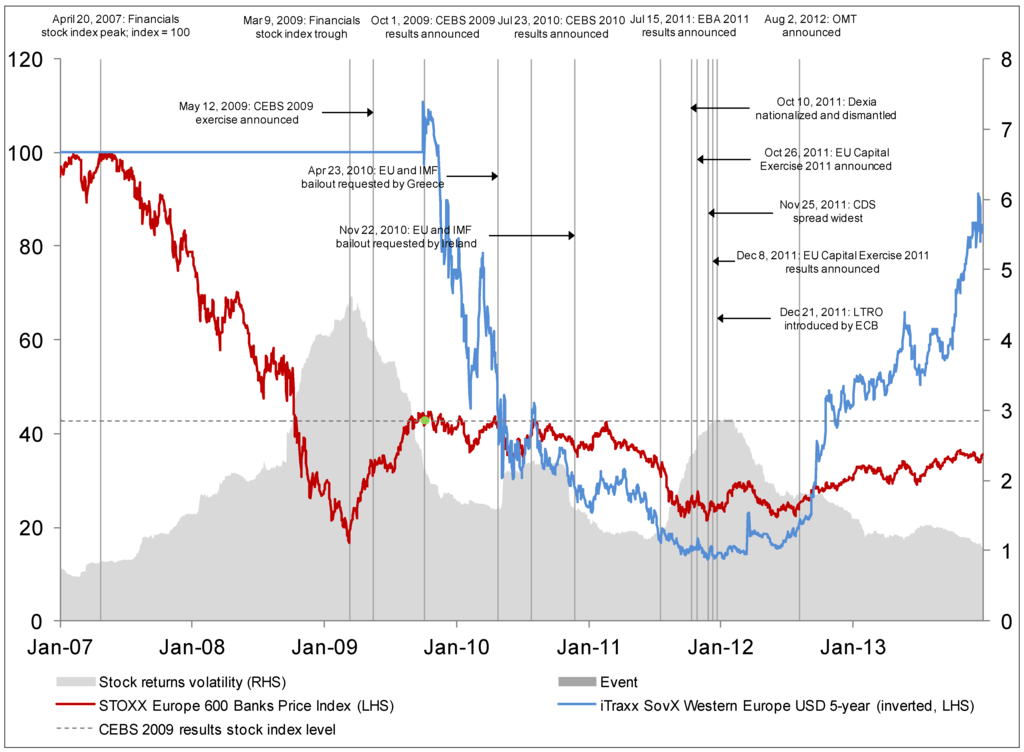

The turnaround in confidence in U.S. banks from the SCAP buoyed sentiment towards banks elsewhere, at least temporarily. EU banks’ stock prices benefitted from the rebound and volatility fell; however, they were unable to sustain the gains over the medium term, with some countries having to conduct separate tests subsequently:

- The stress tests of EU banking systems were less convincing. Although stock prices remained relatively stable following the announcements of the CEBS 2009 and 2010 results, the sovereign CDS spreads continued to widen (Figure 3):

- ➢

- The CEBS 2010 exercise subsequently suffered the ignominy of having Ireland request a bailout from the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the IMF (“the Troika”) weeks after the stress tests indicated that EU banks would remain sufficiently capitalized and resilient under adverse scenarios (CEBS [23]; CEBS [24]). The financials stock index followed a downward trend and despite a turnaround, it has not to this day returned to the levels recorded around the time of the CEBS 2009 stress test.

- ➢

- Similarly, systemic banks Dexia (Belgium) and Bankia (Spain) passed the EBA 2011 stress test (EBA [25]) only to require significant restructuring within a few months. These events were accompanied by sharp jumps in the volatility of stock market returns.

- ➢

- The EU Capital Exercise was subsequently announced in October 2011 in response to a rapidly evolving crisis. The disclosure of its results in December 2011, followed by the introduction of the ECB’s Long-term Refinancing Operation (LTRO) facility for financing eurozone banks later that month, halted the deterioration in confidence towards EU sovereigns as evidenced by their narrowing CDS spreads. In the former, the EBA reviewed banks’ actual capital positions as at end-June 2011 and their sovereign exposures in light of the worsening of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe, and requested that they set aside additional capital buffers by June 2012 based on September 2011 sovereign exposure figures and capital positions (EBA [26]). The announcement of the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) by the ECB in August 2012 further improved market confidence in the region as a whole.

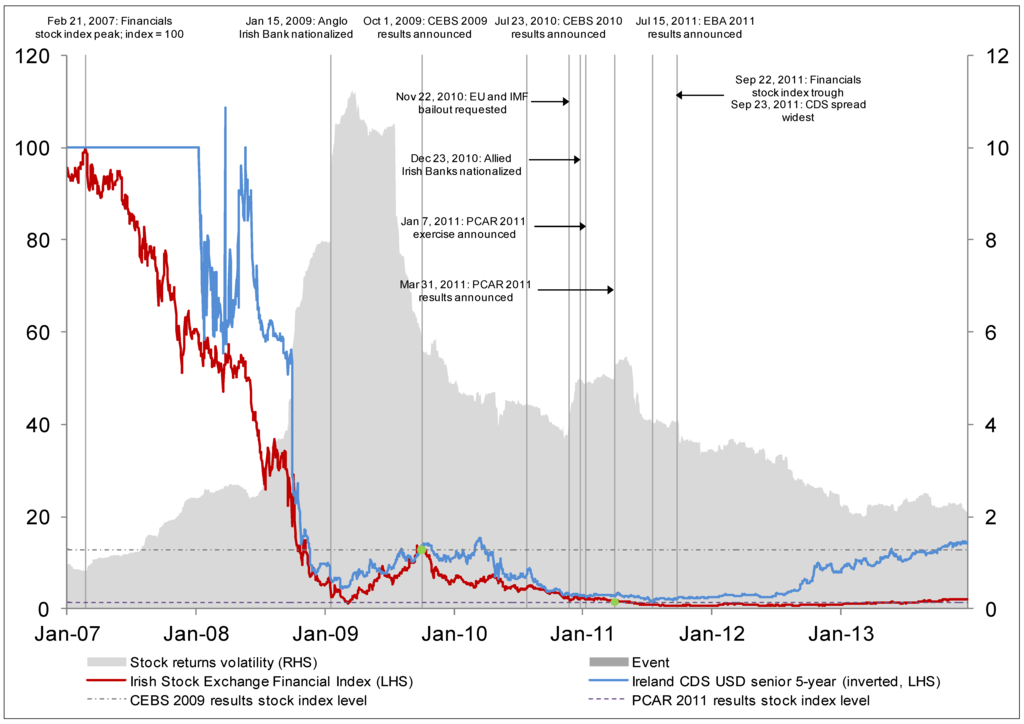

- In Ireland, the Prudential Capital Assessment and Review (PCAR) 2011 exercise contributed to stabilizing market sentiment. However, it was not until the publication of the IMF’s Third Review in September 2011—six months after the release of the PCAR results—indicating that the program’s structural benchmarks had largely been met and that the outcomes of the PCAR were being incorporated into banks’ recapitalization and restructuring plans (IMF [27]), that the exercise gained credibility. In the following six months, the financials stock price index rose by almost 80 percent—albeit from a very low base—the volatility of returns fell and the sovereign CDS spreads tightened by more than 190 basis points (Figure 4).

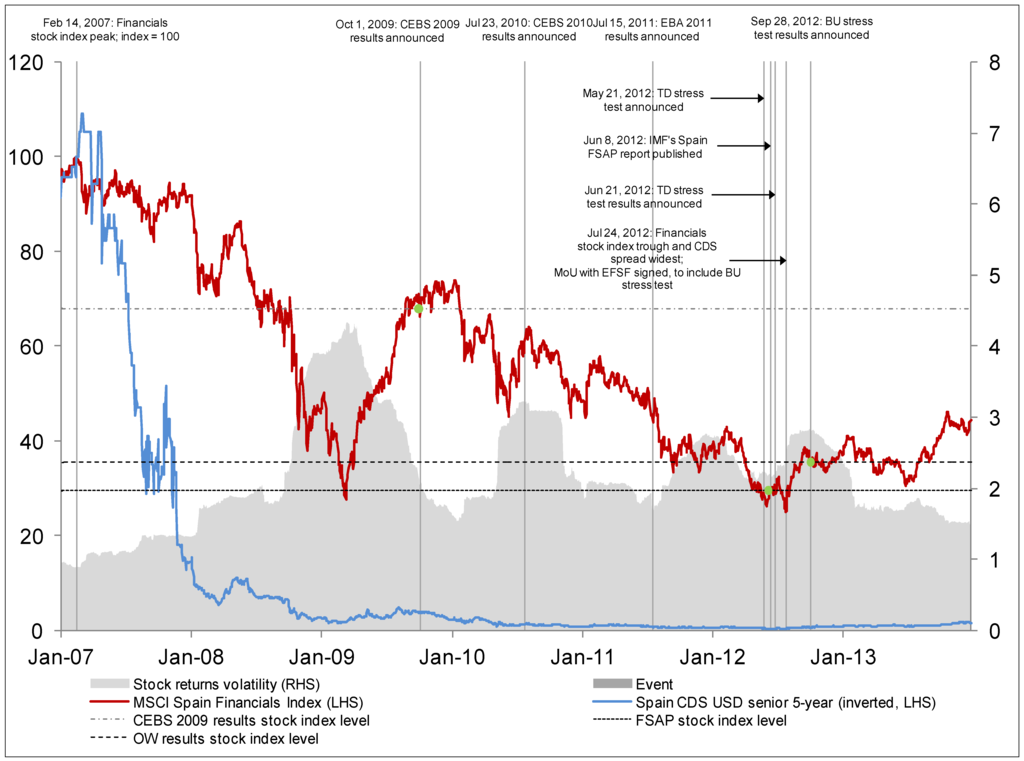

- In Spain, the third-party BU stress test and corresponding revelation of a comprehensive strategy to identify and deal with problem banks stabilized market sentiment. The announcement of the IMF FSAP and third-party TD stress test results coincided with increased volatility in stock price returns, but also signaled that the authorities were closer to taking concerted action to restructure the banking sector (IMF [28]; Roland Berger [29]; Oliver Wyman [30]). The subsequent publication of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Eurogroup in July 2012, which incorporated comprehensive diagnostics of banks’ balance sheets and the details of a financial backstop, reassured investors. Stock price volatility declined sharply and sovereign CDS spreads narrowed by 90 basis points in the 6-month period following the release of the BU results (Figure 5).

A summary of the effectiveness of the respective crisis stress tests is presented in Table 4.

Figure 2.

United States: The Sentiment after the SCAP (Indexed to 100 on 20 February 2007).

Figure 3.

European Union: The Ebb from the EBA (Indexed to 100 on 20 April 2007).

Figure 4.

Ireland: The Pain before the PCAR (Indexed to 100 on 21 February 2007).

Figure 5.

Spain: The “Floor” under the FSAP (Indexed to 100 on 14 February 2007).

Table 4.

Crisis (and Follow-up) Stress Tests: Effectiveness Scorecard.

| Indicator | Effectiveness of Stress Test | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Measure | Desired Change | United States | European Union | Ireland | Spain | |||||||

| Crisis | Supervisory | Crisis | Crisis | Surveillance | Crisis | ||||||||

| SCAP 2009 | CCAR 2011 | CCAR 2012 | CCAR & DFA 2013 | CEBS 2009 | CEBS 2010 | EBA 2011 | PCAR 2011 + IMF | FSAP 2012

1/ | TD 2012 | BU 2012 | |||

| Financials stock index | Index return | Approximately stable or rises | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Return volatility | Falls | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

| Credit default swap | Spread | Approximately stable or narrows | ✔ | 2/ | 2/ | 2/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Effectiveness | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||

Source: Authors; 1/ Included for completeness only—not intended as a crisis stress test; surveillance stress testing exercise was conducted in a crisis environment; 2/ Driven by U.S. fiscal deficit and debt ceiling concerns.

Table 5.

Crisis Stress Tests: Design Scorecard.

| Framework | Application to Stress Test | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Element | Design | United States | European Union | Ireland | Spain | |||||||||||||||

| Feature | Importance for Success | SCAP 2009 | CEBS 2009 | CEBS 2010 | EBA 2011 | PCAR 2011 | FSAP 2012 1/ | TD 2012 | BU 2012 | ||||||||||||

| Effectiveness | … | Financials stock index stabilizes/improves and returns volatility falls | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Not applicable | ✔ | 2/ | |||||||||||||

| Timing of exercise | … | Stress test is conducted sufficiently early to arrest the decline in confidence | ✔ | 3/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Not applicable | |||||||||||||

| Governance | Oversight | Oversight is provided by a third party | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Not applicable | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

| Stress tester(s) | Stress test is conducted by third party | ✘ | 4/ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||

| Scope | Approach | Stress test approach is bottom-up (BU) | ✘ | 5/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

| Coverage | Stress test covers at least the systemically important banks and the majority of banking system assets | ✔ | 6/ | ✔ | ✔ | 7/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||

| Scenario design | Scenarios | Stress test applies large scenario shocks (2 std. devn. or larger) | ✘ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Risk factors | Stress test applies shocks to key risk factors | ✔ | ✔ | 8/ | 8/ | 8/ | ✔ | ✔ | 9/ | ✔ | 9/ | ✔ | 9/ | ||||||||

| Assumptions | Scenarios are standardized across banks | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Behavioral assumptions are standardized across banks | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Capital standards | Hurdle rate(s) | Stress test applies very high hurdle rate(s) (CET > 6 percent) | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Transparency | Objective and action plan | Objective | Stress test is associated with a clear and resolute objective | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

| Follow-up action(s) | Stress test is associated with clear follow up action(s) by management/ authorities to address findings as necessary | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Financing backstop | Stress test is provided with an explicit financial backstop to support the necessary follow-up action(s) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 10/ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Disclosure of technical details | Design, methodology and implementation | Stress test discloses Information | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Model(s) | Stress test discloses Information | ✘ | 11/ | ✔ | ✔ | 12/ | |||||||||||||||

| Details of assumptions | Stress test discloses Information | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

| Bank-by-bank results | Stress test discloses Information | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Asset quality review (AQR) | … | AQR is undertaken as input into stress test | ✔ | 13/ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Follow-up stress tests | … | Stress test assumptions on factors that management control are standardized across banks | ✔ | 14/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 15/ | 15/ | Not applicable | ✔ | 15/ | |||||||||

| Liquidity stress test | … | Liquidity stress test accompanies solvency stress test | ✘ | 16/ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

Sources: Table 3 and Table 4; Appendix I; and authors; 1/ Included for completeness only—not intended as a crisis stress test; 2/ Medium-term sustainability of market confidence remains to be seen; 3/ Delay may impose significant additional costs in order to be effective; 4/ Forecast losses provided by third party; 5/ Not necessary if top-down is conducted on individual banks; 6/ Delay may result in wider coverage of banks to allay increased doubts; 7/ Large cross-border banks; domestic systemically important banks making up at least 60 percent of national banking assets; 8/ Stress test did not include haircuts to sovereign debt holdings in the banking book; 9/ Takes into account the ECB’s LTRO support facility; 10/ Crisis program with the Troika; 11/ Not critical only if independent cross-checks/validation conducted; 12/ Not critical only if independent cross-checks/validation conducted; 13/ Lower-intensity, quantitative substitute for AQR; 14/ Assumptions must be sufficiently stringent and must be disclosed; 15/ Timing will take into account the AQR in the context of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and for Spain and Ireland, the EBA 2014 exercise; 16/ The EBA conducted a confidential thematic review of liquidity funding risks.

4. Designing an Effective Crisis Stress Test

Crisis stress tests require additional considerations which may not be required of supervisory stress tests during normal times. In particular, the design of certain elements may necessarily be different from what is typically done in the latter (e.g., the timing of the test, its governance, the transparency requirements, the objective, action plan and financial backstop). Other aspects have to be constructed to withstand intense public scrutiny (e.g., the scope and scenario design). While no one particular element can alone ensure the success of a crisis stress test, each one plays a crucial part in the credibility of the exercise as a whole.

There are also additional activities that provide integral support for or complement crisis (solvency) stress tests. These include AQRs, separate liquidity stress tests and/or follow-up solvency stress tests, some or all of which may be crucial for the credibility of the original exercise itself. Our overall findings are summarized in Table 5 in a design “scorecard” comparing the features of various elements across crisis stress tests, with the associated details presented in Appendix I.

4.1. Key Elements

4.1.1. Timing

The timing of a crisis stress test is crucial. Steps to reduce uncertainty through information provision should be taken as soon as possible during a crisis. Borio et al. [31] posit that early recognition and intervention would avoid hidden deterioration in conditions that could magnify the costs of the eventual resolution. Pritsker [32] argues that while central bank actions such as broadening the range of acceptable collateral, loan guarantees and government-sponsored capital injections may increase bank lending during a crisis, it also increases the central bank’s exposure to credit and market risk. Such efforts would be less costly and more effective under conditions of less uncertainty, i.e., it would be easier to convince potential lenders of a bank’s solvency if they have better information about the scope of the problem early on.

Experience confirms that delay by country authorities in taking resolute action in a timely manner has eventually required the incurrence of significant additional costs. First, there is the destruction of the banks’ asset values which could take a long time to recover, if at all. Second, the reputational risk to supervisory authorities also grows when a crisis is allowed to fester and deepen. Third, any loss in market, depositor and creditor confidence could potentially place significant burden on the fiscal purse and consequently, the creditworthiness of the sovereign if government support becomes necessary. Combined, these factors could give rise to greater demands when the authorities finally decide to take action, notably:

- The damage to the credibility of the authorities may be too deep-seated to overcome following a lengthy crisis. A consequence could be that they may have to contract third party stress testers and seek independent overseers to enhance the credibility of the exercise.

- Heightened uncertainty about banks’ asset quality and concerns over increasing lender forbearance could mean a more complex, resource-intensive and protracted exercise. The stress test may have to cover a much broader sample of banks than would otherwise be necessary and possibly require additional steps, such as an AQR comprising audits and third-party expert valuations of banks’ portfolios and a DIV exercise.

- Markets are likely to impose higher standards on institutions that are already under extreme pressure if they have lost all trust in the quality of assets (e.g., through expectations of higher loan loss projections and larger capital buffers).

That said, the decision as to what constitutes an “optimal” moment for introducing a crisis stress test is not clear-cut and remains largely an issue of judgment and, possibly, serendipity. As an extension of the principle espoused in IMF [3] that market views should be taken into account in designing stress tests, indicators such as stock prices, their corresponding price-to-book (PB) ratios, as well as sovereign CDS spreads could potentially be used as triggers in deciding on the timing of a crisis stress test (Table 6). However, the evidence to date is inconclusive:

- The United States was first off the rank with the SCAP following two years of decline from the February 2007 historical peak of the S&P 500 Financial Sector Index. The EU CEBS 2009 stress test was also introduced almost 2 years after the STOXX Europe 600 Banks Price Index peaked but has been less effective by comparison. The Ireland and Spain crisis stress tests took place 4 and 5½ years after the apex of their respective financials stock prices. Assuming that the decisions to stress test were made around the end of the year prior to each crisis stress test, the U.S. and European indices would have dropped by anywhere between 65–75 percent by that stage. The long-term (5-, 10- and 15-year) average index levels also do not provide any clear guide to the decision-making process by the authorities as they do not appear to have been used as trigger points. Ireland and Spain conducted their stress tests following their engagement with the Troika for financial support. By that stage, Ireland’s banks had lost almost all their market value, while the equity values of Spanish banks were down by more than 60 percent.

- The PB ratio, which is typically used to assess bank valuations, may yield some hints on the timing of the crisis stress tests. These ratios were richest in late-1990s to early-2000s period for the sample jurisdictions, reaching 3.5 times for the U.S. financials and exceeding 4 times in Ireland and Spain. Long-term averages ranged from 1.8–2.2. The decision to conduct the SCAP would have been made when the PB ratio fell to unity, which could perhaps be considered a “line in the sand” for future reference. The other jurisdictions waited until their respective PB ratios had declined to well below unity, while Ireland’s PCAR would have been contemplated around the time when banks’ average PB ratio had dropped to below 0.3 times.

- Sovereign CDS spreads are an indicator of the market's current perception of sovereign risk. Given the systemic importance of the banking sector for economic activity, market concerns that the government may have to bail out institutions that are too big to fail, and the resulting burden on the fiscal balance, are likely to be reflected in the CDS spreads. In Europe, the sovereign-bank feedback loop from banks’ large holdings of sovereign debt increased the likelihood of losses. Here, any rule-of-thumb that may have been used is less clear—spreads had ballooned to unprecedented levels across the board by the time any decision would have been taken on running the tests.

Table 6.

Crisis Stress Test Jurisdictions: Financial Markets Statistics.

| Indicator | Statistic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Measure | Timing | United States | Europe | Ireland | Spain |

| Financials stock index | Level | Historical peak | 509.6 | 538.8 | 17,951.5 | 158.8 |

| (20 February 2007) | (20 April 2007) | (21 February 2007) | (14 February 2007) | |||

| End of year prior to first crisis stress test | 168.8 | 151.1 | 414.3 | 62.1 | ||

| (31 December 2008) | (31 December 2008) | (31 December 2010) | (31 December 2011) | |||

| Change from peak (percent) | −67.9 | −72.0 | −97.7 | −60.9 | ||

| Average level to end-year prior to stress test | 5-year | 398.7 | 393.5 | 7,528.5 | 101.8 | |

| (2004–2008) | (2004–2008) | (2006–2010) | (2007–2010) | |||

| 10-year | 368.5 | 365.5 | 8,427.3 | 100.4 | ||

| (1999–2008) | (1999–2008) | (2001–2010) | (2002–2010) | |||

| 15-year | 309.0 | 306.5 | 7,434.5 | 91.7 | ||

| (1994–2008) | (1994–2008) | (1996–2010) | (1995–2010) | |||

| Price-to-book ratio of financials stock index | Ratio | Historical peak | 3.50 | 2.21 | 4.16 | 4.74 |

| (12 September 2000) | (15 May 2002) | (1 January 1999) | (17 July 1998) | |||

| End of year prior to first crisis stress test | 0.99 | 0.73 | 0.26 | 0.72 | ||

| (31 December 2008) | (31 December 2008) | (31 December 2010) | (31 December 2011) | |||

| Change (percent) | −71.7 | −67.0 | −93.8 | −84.8 | ||

| Average ratio to end of year prior to stress test | 5-year | 1.84 | 1.75 | 1.25 | 1.36 | |

| (2004–2008) | (2004–2008) | (2006–2010) | (2007–2010) | |||

| 10-year | 2.24 | … | 1.83 | 1.71 | ||

| (1999–2008) | (2001–2010) | (2002–2010) | ||||

| 15-year | 2.21 | … | … | … | ||

| (1994–2008) | ||||||

| Credit default swap | Spread (basis points) | Historical narrowest (based on data availability) | 5.8 | 46.0 | 16.1 | 1.5 |

| (29 April 2008) | (29 September 2009) | (24 March 2008) | (20 June 2005) | |||

| End of year prior to first crisis stress test | 67.4 | … | 608.7 | 380.4 | ||

| (31 December 2008) | (31 December 2008) | (31 December 2010) | (31 December 2011) | |||

| Change from narrowest | +61.6 | … | +592.6 | +378.9 | ||

| Change from narrowest (percent) | +1,062.1 | … | +3,780.7 | +25,260.0 | ||

Sources: Bloomberg; and authors’ calculations.

Ideally, a crisis stress test should be conducted before the crisis of confidence in the banking system becomes entrenched. However, the successful exercises to date reveal little in terms of whether they had been appropriately timed given that counterfactuals are difficult to prove:

- By all measures, the “intervention” by the U.S. authorities did halt and turn around the sharp slide in market confidence. That said, the rebound from the 80 percent loss in banks’ market value has been sluggish compared to the overall market, which has recovered all its losses from the crisis (Figure 6). The question then is whether the rise in the financials index would have been quicker and stronger had the supervisors stepped in earlier. Although bank stocks may have arguably been overvalued prior to the crisis, their PB ratio is currently well below the 15-year average.

- The eventual outcomes from the Ireland and Spain stress tests have also been positive but these achievements were almost pyrrhic. The supervisors were perceived to have lost significant credibility with markets by that stage (e.g., The Irish Times [33]; Garicano [34]). External consultants had to be employed to conduct comprehensive AQRs and in the case of Spain, to run the stress tests in order to reassure investors (third-party consultants provided forecast losses for the Ireland stress test). Moreover, the fiscal cost of supporting their respective banking systems had become so onerous that both countries had to eventually request external financial aid.

Irrespective of the timing of a crisis stress test, recognition of the problem alone is insufficient. It should be linked to restructuring if a bank’s profitability is to eventually be restored. In other words, the decision to conduct a crisis stress test should also take into account the potential implications for the public purse, i.e., it must be tied to the capacity of the authorities to adequately backstop and address the findings. The evidence suggests that while the timing of crisis stress tests may be important, it is insufficient in the absence of other key elements, as elaborated throughout the rest of this section.

Figure 6.

United States: S&P 500 Stock Market and Financial Sector Indices (Indexed to 100 on February 20, 2007).

4.1.2. Governance

There is no hard and fast rule as to who should oversee and/or conduct the crisis stress test. The overriding requirement is that the protagonists are considered credible. In some cases, issues such as expertise, sufficiency of resources and/or political economy considerations play equally important roles in determining who they should be:

- In the United States, the oversight and execution of the SCAP relied on collaboration across supervisory agencies—the Fed, the FDIC and the OCC; supervisors of individual banks were consulted but not involved in the actual stress test analyses.

- The EU-wide stress tests were conducted by national supervisory authorities, overseen and coordinated by the EBA (which did not have direct interaction with the banks prior to or during the exercise) in cooperation with the EC and the ECB/European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB). However, the EBA had argued that it needed more legal powers over the exercise to ensure the reliability of the input data, and hence the results (see Brunsden [35]).

- In contrast, the authorities in Ireland and Spain appointed third-party contractors in their efforts to strengthen perceptions of independence and objectivity in the process. The reputation of the supervisors had been dented after their banks passed the CEBS/EBA stress tests only to require significant restructuring not long afterwards. In the case of Spain, the authorities, the Troika, the EBA and counterparts from two other European central banks were involved in the oversight of the stress testing exercises.

4.1.3. Scope

There is some flexibility to the stress testing approach taken in a crisis exercise. Ideally, a bottom-up (BU) test, cross-validated by a top-down (TD) exercise, would be the superior approach (IMF [3]; Jobst et al. [21]), but this may not be possible in a crisis situation where the timeframe is compressed (see Figure 1, Note 1 for IMF staff’s definitions of BU and TD stress tests). Both BU and/or TD approaches have been used effectively in crisis stress tests. However, if only a TD stress test can be undertaken, it should be conducted on a bank-by-bank rather than aggregated basis, which is consistent with the need for transparency at the disclosure stage, as we discuss below. Additionally, the stress tests should be supported by inputs from AQRs (and preferably DIVs) which we cover later in this paper:

- The U.S. SCAP consisted of a BU and TD mix, with what we would deem a lower-intensity, quantitative substitute for an AQR. The supervisors applied independent quantitative methods using firm-specific data to support their assessments of banks’ submissions (Fed [36]).

- The EU CEBS 2010 and the EBA 2011 exercises comprised BU tests by cross-border banking groups and simplified stress tests, based on national supervisors and reference parameters provided by the ECB, for less complex institutions. The CEBS 2010 stress test included a peer review of the results and a challenging process, as well as extensive cross-checks by the CEBS (CEBS [14]); the process evolved for the EBA 2011 exercise to incorporate consistency checks by the EBA, a multilateral review and TD analysis by the EBA and the ESRB with ECB assistance (EBA [37]).

- Ireland’s PCAR 2011 was a BU exercise supported by an AQR. Banks were required to model the impact of certain assumptions on their balance sheets and profit and loss accounts (revenues and losses) based on a third party’s assessment of forecast losses (CBI [38]). The stress test was perceived to be particularly credible in that it explicitly compared the loan loss estimates of the CBI with those of the third party as a cross-check of the results, which were subsequently published by the CBI.

- In Spain, two sets of crisis stress tests were conducted in 2012 and the results were published by the third party-consultants who conducted the exercises:

- ➢

- The first exercise was a TD stress test. Two consultants separately considered the historical performance and asset mix for each institution at aggregate levels to generate forward-looking projections. The consultants applied their own models, expert experiences and benchmarks (Roland Berger [29]; Oliver Wyman [30]).

- ➢

- The second stress test was conducted by one consultant, using detailed data from banks and inputs from a comprehensive AQR exercise. Specifically, the test drew on information derived from external reviews by independent auditors and real estate appraisers and from BdE central databases, to estimate individual banks’ capital needs under a baseline and an adverse scenario (Oliver Wyman [39]). Structural analysis of individual banks’ financial statements and business plans were undertaken. Given that the banks only ran their own models on the baseline scenario to generate net revenues, it was essentially another TD exercise—albeit at a much more granular level—but is widely referred to as a bottom-up (BU) exercise. (For differentiation purposes, we refer to the first as the TD test and the second as the BU test).

The coverage of banks should capture at least the systemically important institutions, given the macroprudential nature of the stress test (see IMF [3]; Jobst et al. [21]). In this respect, guidance has been provided by the FSB on what constitutes global and domestic systemically important banks (BCBS [40,41]). However, the sample may have to be expanded depending on the environment at the time of implementation. While some banks are of obvious systemic importance and their selection is indisputable, the difficulty has been in identifying those that are systemic at the margins, e.g., some of the smaller institutions which may have the potential to become or have become systemic under certain conditions (IMF/BIS/FSB [42]). In cases where there has been a total loss of confidence in the entire banking system and uncertainty about the soundness of individual banks is very high, the coverage may have to include even the smaller, non-systemic banks to forestall a “witch hunt” for failed and failing banks. Coverage has differed across the various crisis stress tests to date (including whether the tests were run on consolidated or domestic business data), but each exercise has captured at least 60 percent of domestic banking system assets:

- The U.S. SCAP included the 19 largest bank holding companies (BHCs), each with total assets greater than $100 billion. They represented two-thirds of banking system assets.

- The EU CEBS 2009 stress test captured 22 large cross-border banks with 60 percent of EU banking assets; the number of banks increased to 91 in subsequent exercises, covering 21 countries and at least 50 percent of each banking sector, for an additional 5 percentage points coverage of EU banking assets. However, the flexibility for country authorities to choose which banks to include in the stress tests was perceived to have reduced the legitimacy of the exercises (Ahmed et al. [43]).

- Ireland’s PCAR 2011 stress tested four financial institutions which accounted for 80 percent of banking system assets.

- In Spain, the TD and BU stress tests covered banks accounting for around 90 percent of total system assets. Initial concerns had been with some medium-sized and smaller banks rather than the largest, most systemic banks. However the slow deterioration in sentiment over a prolonged period and constant revelations of new problems eventually affected perceptions of the entire banking system. In the end, the inclusion of both the largest banks and the smaller problem ones in both stress tests became necessary in order to differentiate the strong institutions from the weak ones.

4.1.4. Scenario Design

The selection of adverse macroeconomic scenarios in crisis stress tests represents a delicate balance between the need to be credible yet constructive. As a principle, stress scenarios should capture extreme but plausible shocks, i.e., the tail risks for the financial system (BCBS [12]; IMF [3]). However, while this principle should always be applied in stress tests for surveillance purposes to support discussions on supervisory actions and crisis preparedness (Jobst et al. [21]) and in regular supervisory stress tests, it needs to be more nuanced in a crisis situation.

In a crisis stress test, the adverse scenario should reflect the uncertainty around the baseline. Crises are typically already tail risk events in themselves. In some cases, they may even be labeled “black swan” events at the outset, as some have argued is the case of the current global financial crisis (e.g., Helmore [44]; Skidmore [45]), although the prolonged accumulation of economic and financial imbalances may be obvious in hindsight. In such an environment, banks may already be under severe stress. In other words, the point of the cycle at which the shock is applied matters. Consequently, any implementation of further “tail of the tail” shock scenarios that would hypothetically obliterate an entire banking system would obviate any constructive planning of needed follow-up action(s) by the authorities and the banks themselves. Borio et al. [46] argue that it is easier to identify relevant scenarios for stress testing purposes after a crisis has erupted as the system “does not need to be shaken so hard to reveal weaknesses.” Rather, a key consideration in the scenario design at that stage is that the crisis stress test should be able to differentiate across institutions, as a first step towards determining whether capital injection, some other form of balance sheet restructuring or resolution is required.

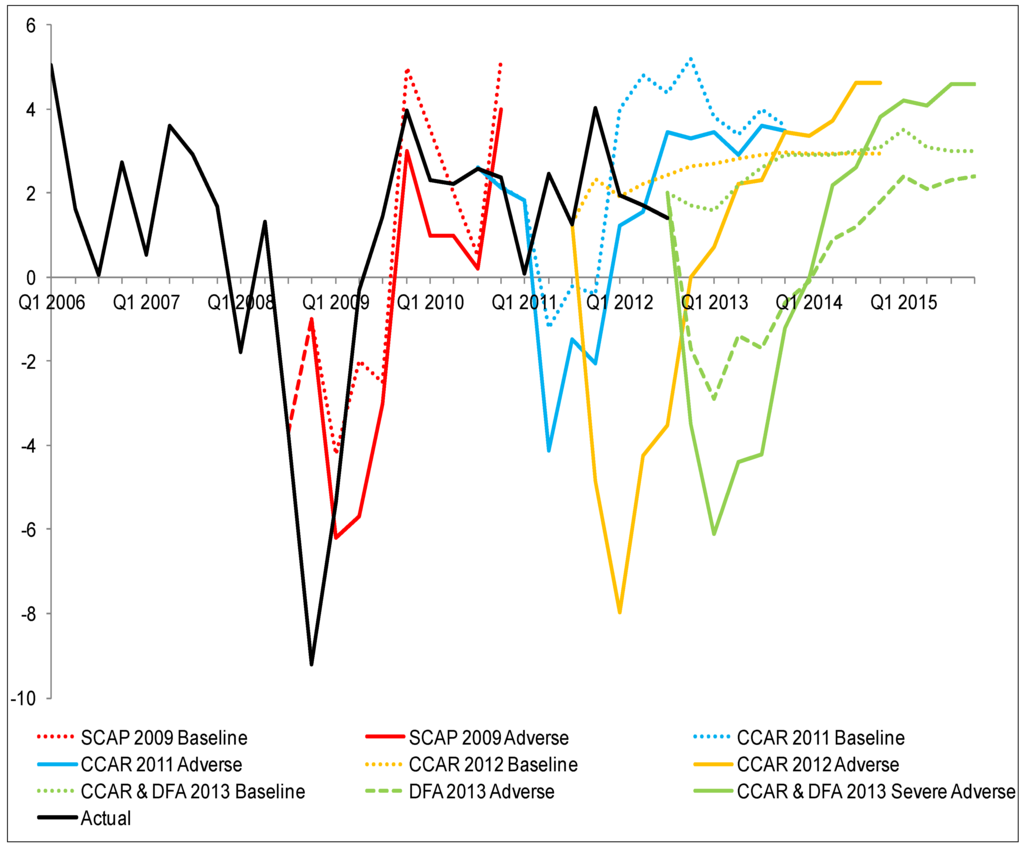

The evidence from the crisis case studies suggests that the magnitudes of the macroeconomic shock scenarios per se are not an overriding element for success. The CEBS/EBA stress tests have been derided for the apparent mildness of their adverse growth stress scenarios, among other things, contributing in part for their lack of acceptance (e.g., Ahmed et al. [43]; Campbell [47]; Jenkins [48]; Steinhauser [49]; IMF [50]). However, a closer examination of the other crisis stress tests suggests that this argument may be flawed:

- The CEBS 2009 and 2010 and the EBA 2011 exercises applied cumulative growth shocks averaging 1.9, 1.3 and 1.5 standard deviations from their respective baseline growth scenarios (Box 1), with attendant shocks to other macroeconomic variables. However, the test results did not gain wide acceptance.

- What is not commonly known is that the adverse growth scenario used in the SCAP was even less stressful than any of the CEBS/EBA shocks. It was equivalent to a cumulative one standard deviation from the baseline over the two-year risk horizon, determined well before the contraction had bottomed out (Figure 7). Indeed, the SCAP stress scenario was criticized by some at the time the results were announced for likely being closer to the actual baseline itself (e.g., Fox [51]). Yet, the SCAP was effective in regaining market confidence.

- Similarly, the growth shocks applied to both the Spain TD and BU stress tests were equivalent to one standard deviation from the projected baseline, while Ireland’s PCAR 2011 used the EBA scenarios.

Figure 7.

United States: Baseline and Adverse Growth Scenarios for Crisis and Supervisory Stress Tests (In percent, quarter-on-quarter annualized).

The selection of macroeconomic parameters in the scenario design does not appear to significantly influence the credibility of a crisis stress test either. The SCAP was parsimonious, with three (real GDP growth, the unemployment rate and house prices), while the Ireland and Spain stress tests employed more than a dozen different ones (Table 7). Unlike the growth scenarios, and outside of some coverage of the real estate and employment variables, the projections for most of the other variables were generally less scrutinized.

Table 7.

Crisis Stress Tests: Macro-financial Parameters Scorecard.

| Parameter | Application to Stress Test | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Indicator | United States | European Union | Ireland | Spain | ||||

| SCAP 2009 | CEBS 2009 | CEBS 2010 | EBA 2011 | PCAR 2011 | FSAP 2012 1/ | TD 2012 | BU 2012 | ||

| Growth | Real GDP | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Real GNP | ✔ | ||||||||

| Nominal GDP | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Employment | Unemployment rate | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Employment | ✔ | ||||||||

| Price evolution | CPI | 2/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| HICP | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| GDP deflator | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Consumption | Private | ✔ | |||||||

| Government | ✔ | ||||||||

| Trade | Exports | ✔ | |||||||

| Imports | ✔ | ||||||||

| Balance of payments | ✔ | ||||||||

| Income and investment | Investment | ✔ | |||||||

| Personal disposable income | ✔ | ||||||||

| Real estate | Real estate prices | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Commercial property | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

| Residential property | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Land | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Interest rates | Short-term interest rate (12 months or less) | 2/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Medium-term interest rate (up to 5 years) | 2/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

| Long-term interest rate (more than 5 years) | 2/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| Exchange rate | Relative to U.S. dollar | 2/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Stock market | Stock price index | 2/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Credit to other resident sectors | Households | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

| Non-financial corporate | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

Sources: CBI; EBA; Fed; IMF; Oliver Wyman; and Roland Berger; Note: Even though some variables (e.g., commodities, CDS, securitized assets) were not provided as part of the general macro scenarios, they were used in the determination of key market risk drivers; 1/ Included for completeness only—not intended as a crisis stress test; surveillance stress testing exercise was conducted in a crisis environment; 2/ Information not disclosed.

Consistent with best practice, comprehensive coverage of material risk factors in crisis stress tests appears to be much more relevant for the reliability of the results (BCBS [12]; Fed/FDIC/OCC [13]; IMF [3]). The global financial crisis has brought to the fore risks which had previously been in the periphery or which had not been considered, such as exposures to sovereign and other previously low-default assets, their accounting in the banking or trading book, funding costs and cross-border exposures, among others (Jobst et al. [21]). The U.S. stress test covered banks’ entire balance sheets (including their international exposures) while the European stress tests focused on banks’ domestic loan books (Table 8), which were the main concern of investors. However, the exclusion of some important risk factors affected the credibility of some of these exercises:

- The EU stress tests have been vociferously criticized for their inadequate capture of important risk factors, owing in part to political economy constraints (see Wilson [52]; Wishart [53]). The failure to properly stress banks’ sovereign exposures was considered particularly egregious in light of the debt crisis and concerns about the bank-sovereign feedback loop (e.g., Ahmed et al. [43]; Das [54]; Steinhauser [49]). Specifically, the haircuts imposed on banks’ sovereign portfolios in the trading book during the EBA 2011 exercise were seen to have been too lenient as they only applied a market value adjustment rather than possible defaults, while the omission of any stress test of the banking book—where the majority of banks’ sovereign exposures resided—meant that the main risk factor at the time had not been adequately captured.

- In Spain, concerns about lender forbearance and possible misclassifications in banks’ loan books were addressed in the BU exercise. Auditors and real estate appraisers were appointed to verify the quality of the input data. The issue of sovereign risk was omitted but was considered less of an issue owing to the availability of the LTRO facility from the ECB by the time of the stress tests. The liquidity support allayed market concerns about banks’ funding costs and possible deep haircuts to their sovereign debt portfolio as the pressure for banks to liquidate their holdings in the hold-to-maturity (HtM) banking book and realize the losses abated.

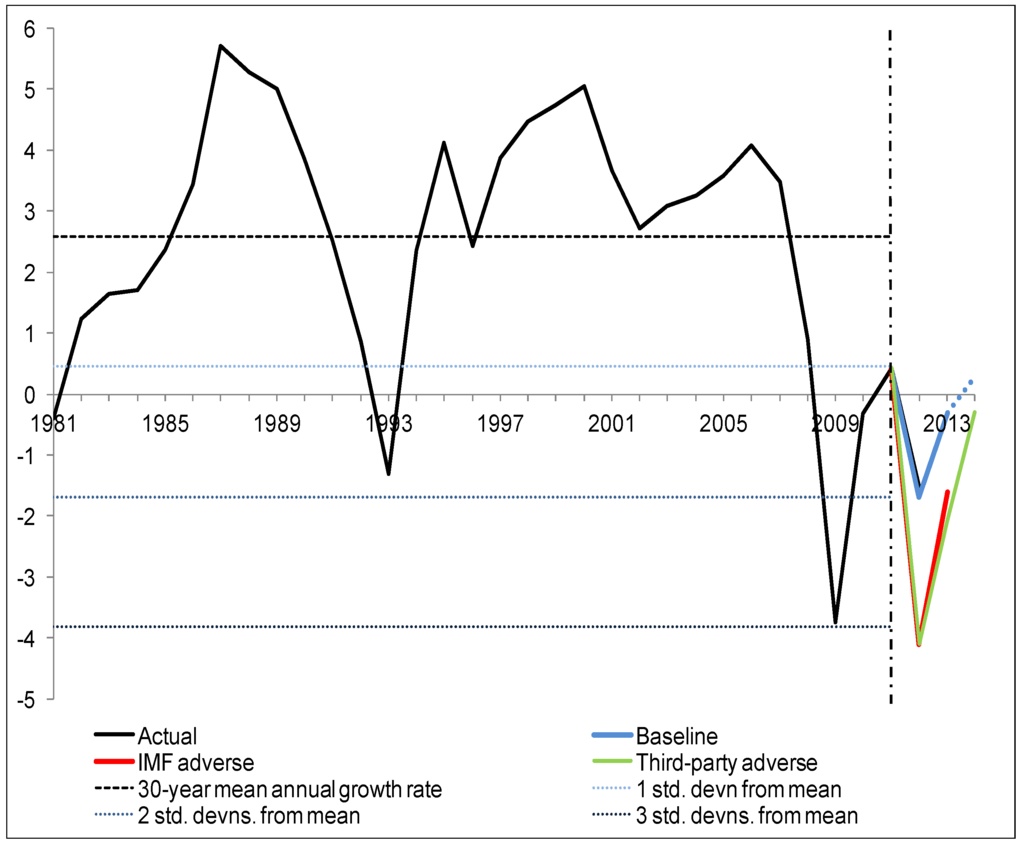

Box 1. Designing Crisis Stress Test Growth Scenarios.

The CEBS stress tests popularized the notion of calibrating growth shocks in terms of the number of standard deviations from the baseline. This metric allows for a more standardized comparison across stress tests at a point in time and over time. For instance, the application of a large growth shock scenario to an economy that typically experiences large and volatile growth rates may be a less significant event than to one which consistently posts more moderate and stable growth. The CEBS method for determining adverse growth scenarios consists of the following steps:

- Calculate the 2 year growth rates over the preceding 30 years.

- Calculate the standard deviation of the 2-year growth rates over the 30 year period.

- Calculate the desired number of standard deviations of the 2-year growth rate.

- Apportion the standard deviation(s) growth over the 2-year horizon and subtract from each year of the baseline forecast to derive the stressed scenario.

The rule of thumb in the IMF’s Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) scenario stress tests has generally been to apply two standard deviation shocks to growth (IMF [3]; Jobst et al. [21]), but calibrations have been necessary in crisis situations. For example, the Spain FSAP stress test imposed a “severe adverse” scenario of one standard deviation from the baseline GDP growth trend over a two-year risk horizon (IMF [28]). The shock came on top of a downward adjustment to the World Economic Outlook baseline forecast to incorporate downside risks to growth from the crisis plus a projected fiscal adjustment. In this scenario, most of the shock to the baseline growth (about two-thirds) was assumed to occur in the first year, attributable to a sharp decline in output, further declines in house prices and rising unemployment.

Viewed from another angle, the 2-year cumulative GDP shock for Spain under the severe adverse scenario was considered extreme by historical standards, as the actual outcome proved. The GDP drop in the first year of the risk horizon approximated the largest decline in economic activity since 1945 but represented a plausible “tail of the tail” risk under the circumstances (Box Figure 1). The third-party crisis stress tests subsequently increased the second-year stress and extended both scenarios to a third year. As it turned out, the growth in 2012—the first year of the risk horizon—approximated the projected baseline.

A corroborating method to gauge the extremity of a proposed shock scenario is to determine its deviation from the long-term historical average, in standard deviation terms. In the Spain example, the adverse shock scenario extended beyond 3 standard deviations of the mean annual growth rate of the past 30 years; it exceeded even the sharp contraction experienced in 2009 and was designed to be more protracted.

Box Figure 1.

Spain: 30-year Average Annual Growth Rate and Stress Test Scenarios (In percent).

Table 8.

Crisis Stress Tests: Risk Factors Scorecard.

| Risk Factor | Application to Stress Test | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Type | Nature of Accounting | Exposure | United States | European Union | Ireland | Spain | ||||

| SCAP 2009 | CEBS 2009 | CEBS 2010 | EBA 2011 | PCAR 2011 | FSAP 2012 1/ | TD 2012 | BU 2012 | |||

| Credit risk | … | Residential mortgages | ✔ | 4/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| First lien | ✔ | |||||||||

| Second lien | ✔ | |||||||||

| Commercial and industrial loans 2/ | ✔ | |||||||||

| Corporate loans | 3/ | 4/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| RE developers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| SME loans | 3/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

| CRE loans | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Financial institutions loans | ✔ | 4/ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Consumer loans (including credit card) | ✔ | 4/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Revolving loans | 3/ | ✔ | ||||||||

| Public works | 3/ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Sovereign exposure in available-for-sale (AfS) banking book | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||

| Other loans | ✔ | |||||||||

| Market risk | Trading book | Sovereign portfolio | ✔ | 4/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Financial institutions portfolio | ✔ | 4/ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| Other securities (incl. MBS and other ABS) | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||

| Private equity holdings | ✔ | |||||||||

| Counterparty credit exposures to OTC derivatives | ✔ | |||||||||

| Banking book (AfS) | Sovereign portfolio | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Financial institutions portfolio | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||

| Other securities (incl. MBS and other ABS) | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||

| Banking book (HtM) | Sovereign portfolio | ✔ | ||||||||

| Financial institutions portfolio | ✔ | |||||||||

| Other securities (incl. MBS and other ABS) | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||

| Operational risk | … | … | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Separate liquidity risk test | … | … | 5/ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

Sources: CBI; EBA; Fed; IMF; Oliver Wyman; and Roland Berger; 1/ Included for completeness only—not intended as a crisis stress test; surveillance stress testing exercise was conducted in a crisis environment; 2/ Includes corporate, SME, revolving and public works loans; 3/ Included under “Commercial and industrial loans”; 4/ Information not disclosed; 5/ The EBA conducted a confidential thematic review of liquidity funding risks.

Another aspect of crisis stress testing is the standardization of assumptions and not just the assumptions themselves. Crisis stress tests tend to be more constrained in the assumptions that are employed, in order to facilitate comparisons. That said, absolute standardization is not necessary for credibility. To date, all crisis stress tests have imposed consistent macro scenario(s) on all banks within a particular jurisdiction, but behavioral assumptions (i.e., assumptions with regard to factors that management control) have been allowed to vary, typically with cross-checks by another party to ensure their reasonableness. Ultimately, what has been more important is the publication of information relating to those assumptions so that market participants are able to replicate the results to their own satisfaction (see discussion below on communication):

- In the SCAP, the U.S. supervisors provided assumptions for the macroeconomic scenarios. Banks were asked to adapt the assumptions to reflect their specific business activities when projecting their potential losses and resources for absorbing those losses; supervisors then reviewed and assessed the firms’ submissions and the quantitative methods that were used to project those losses and resources, as well as the key assumptions (Fed [36,55]). To facilitate horizontal comparisons across firms, supervisors applied their own independent quantitative methods to firm-specific data.

- The EU CEBS/EBA stress tests applied macroeconomic and sovereign shock scenarios and parameters developed by the ECB. Very detailed and prescriptive guidance on assumptions and methodologies were provided for the EBA 2011 exercise (EBA [37]). Banks’ calculations were reviewed and challenged by the respective national supervisors, then analyzed by the EBA, which conducted in-depth consistency checks and challenges with national supervisors.

- Ireland’s PCAR 2011 incorporated many of the parameters used for the EBA 2011 stress test. A private consultancy firm was contracted by the CBI to provide oversight and to challenge the work of the third-party stress tester and to ensure consistency across institutions and portfolios (CBI [38]).

- The Spanish stress tests used the growth scenarios and guidelines provided by a Steering Committee comprising the authorities, the Troika and counterparts from two European central banks. The process and methodology for the BU exercise were closely monitored and agreed upon with an Expert Coordination Committee from the Troika, the EBA and the authorities (Oliver Wyman [39]).

The crisis brought forward-looking techniques to the front and center of stress testing. Eschewing in part the backward-looking probabilistic calculations based on historical periods of stress, the scenario-based stress testing framework incorporates quantitative forecasts for a wide range of macroeconomic variables to generate a wide range of plausible outcomes. It facilitates the identification of risk concentrations in the banking system and consequently, preparedness for dealing with the dangers of an uncertain future. Langley [8] argues that the “practical usefulness” of the SCAP’s results which made it possible for the authorities and the banks to act on an anticipated financial future—rather than the actual results themselves (which in fact showed that the major banks needed to raise significant additional capital) or their accuracy (which cannot be proven ex ante)—underpinned its success.

In a similar context, crisis stress testing has also placed the spotlight on the modeling of revenues and losses. While stress testing for losses has typically been to map macro-factors onto the various risk factors that drive the impairment parameters, the crisis has underscored the importance of adequately modeling losses for different categories of credit risk (e.g., various types of real estate, corporate sector, credit cards), geographic heterogeneity and a rapidly evolving macro-financial environment for which there has been no precedent. Separately, stress testing revenues—especially for stressed conditions—is largely seen to be a “black box” (Schuermann [7]). Given the importance of projected pre-provision profits in determining banks’ loss absorption capacity in stress scenarios, the credibility of these estimates are key in the overall perception of any stress testing exercise.

4.1.5. Capital Standards

The capital standards applied to crisis stress tests play a crucial role in their legitimacy, but evidence from the case studies suggests that some variability is acceptable. Countries would typically apply their existing capital frameworks. In this context, the differences in regulatory frameworks and thus difficulty in comparing stress test results across jurisdictions do not appear to be an overriding concern for markets, as long as the definition of capital is made clear in each case. Bernanke [9] notes the importance of focusing not just on the levels of capital but also on the composition of capital (which is also consistent with Basel III) in a crisis stress test:

- The U.S. authorities applied their existing capital framework. Banks were required to meet the T1 capital hurdle of 6 percent post-stress and the higher quality T1 Common Equity ratio of 4 percent post-stress. Basel I risk weights were used to calculate risk-weighted assets (RWA), providing transparency in this aspect of the stress test. Nonetheless, the authorities acknowledged in designing the SCAP that “no single measure of capital adequacy is universally accepted or would guarantee a return of market confidence” (Bernanke [56]).

- The EU, Ireland and Spain stress tests applied the existing Capital Requirement Directive (CRD) at the time (i.e., CRD II) to the calculation of capital. The Basel II risk weights–which are more opaque—were used to calculate RWA. That said, the capital definition deviated from that of the regulatory directive.

- ➢

- The CEBS 2009 and 2010 stress tests applied a T1 hurdle rate of 6 percent. The EBA 2011 stress test evolved in line with Basel III developments—it implemented a commonly-agreed upon definition of common equity capital (“EBA Core Tier 1 (CT1)”) and applied a post-stress hurdle rate of 5 percent, noting that a higher threshold than the legal minimum was “necessary in assessing the resilience of banks in adverse circumstances if credibility and confidence in the banking sector is to be restored” (EBA [57]).

- ➢

- Ireland imposed a hurdle rate of 10.5 percent for the baseline scenario and 6 percent EBA CT1 under stress (up from the 4 percent required minimum), plus an additional protective buffer.

- ➢

- The Spain TD and BU stress tests applied an EBA CT1 hurdle rate of 9 percent under the baseline scenario and 6 percent for the adverse scenario.

In a crisis situation, tensions may arise between microprudential and macroprudential objectives in determining the adequacy of capital buffers (IMF [58]). While concerns such as lender forbearance and loan misclassification should be taken into account, especially in instances where AQRs are not undertaken, requiring banks to hold very high post-stress test capital ratios (microprudential) to meet—sometimes unreasonable—market expectations (see Box 2) could lead to excessive deleveraging, forestall the issuance of new credit to the economy and exacerbate the economic downturn (macroprudential). The result could be a vicious circle of further deterioration in the asset quality of banks and consequently, further destruction of capital.

Instead, banks should build strong prudential buffers during good times so that they are in a position to reduce them during bad times in a manner that respects microprudential objectives. The design of the capital standards for the Ireland and Spain crisis stress tests applied this philosophy—banks were expected to maintain a high level of CT1 capital adequacy (which incorporated a buffer) under a central (baseline) case scenario, but were assumed to be able to draw on the buffer in the event that an extreme stress scenario were to materialize. During bad times, encouraging increases in capital levels rather than ratios could align both microprudential and macroprudential objectives.

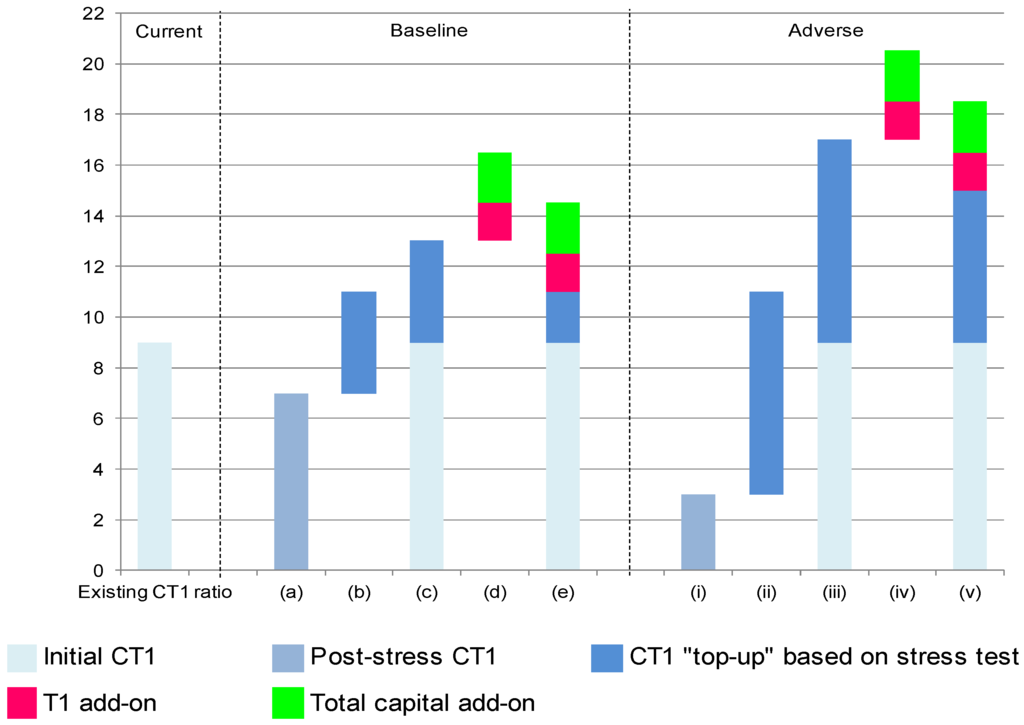

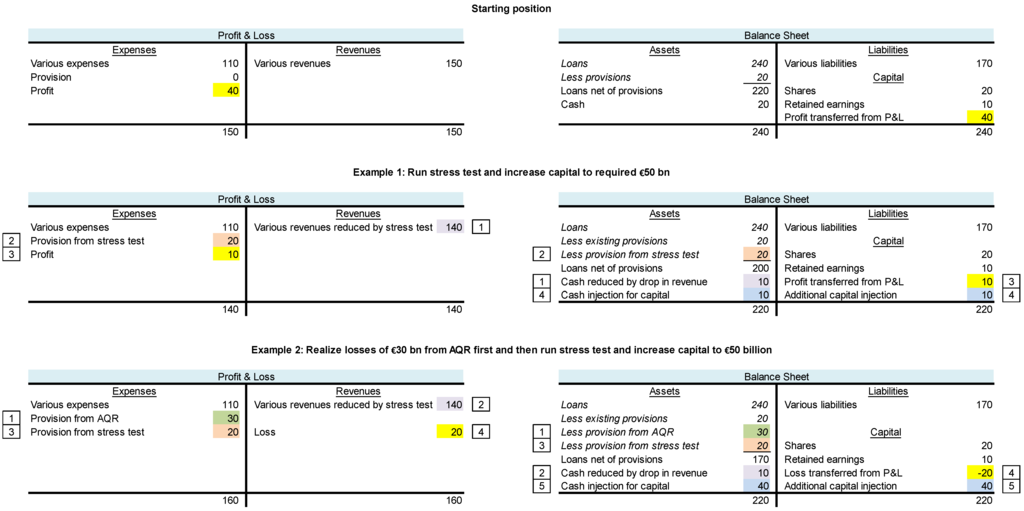

Box 2. The Potential Impact of Capital Hurdle Rates for Crisis Stress Tests.

In a crisis stress test, where the results may require follow-up capital action, the setting of capital hurdle rates is of significant import. Combined with the magnitude(s) of the applied shock(s), hurdle rates play a potentially crucial role in estimating any required recapitalization and consequently, in any decision to restructure or exit banks from the system. These could have far-reaching implications for capital raising and possibly the fiscal budget.

The recapitalization of banks based on stress test outcomes could affect their lending capacity if the hurdle rates are set too high. As a simple example (Box Figure 2), let us assume that a bank has (i) a pre-shock CT1 ratio of 9 percent; (ii) constant RWA; and (iii) to meet a required CT1 capital adequacy hurdle rate of 11 percent post-stress, which includes a buffer. Next, consider two stress test scenarios—a baseline and an adverse:

- Baseline (central case)

- (a)

- Assume that under the baseline scenario, the bank’s CT1 ratio is reduced by 2 percentage points to 7 percent.

- (b)

- The bank is expected to take capital action that would return the CT1 ratio up to 11 percent, i.e., an increase of 4 percentage points.

- (c)

- In other words, the bank would have to “top up” its existing 9 percent CT1 ratio with another 4 percentage points up to 13 percent, in anticipation of the baseline scenario materializing.

- (d)

- This means that the bank would have to hold a total capital adequacy ratio of more than 16 percent, once additional requirements to make up T1 and total capital are included, and even before taking into account possible items such as D-SIB or G-SIB surcharges.

- (e)

- If the central case growth forecast is accurate and the bank’s CT1 ratio is indeed reduced by 2 percentage points, the bank would have a CT1 ratio of the targeted 11 percent.

- Adverse

- (i)

- Assume that under a severe adverse scenario, the tail shock sharply increases the bank’s projected losses and reduces its CT1 ratio by 6 percentage points to 3 percent.

- (ii)

- The bank is expected to take capital action that would return the CT1 ratio back up to 11 percent, i.e., an increase of 8 percentage points.

- (iii)

- In other words, the bank would essentially have to have a CT1 ratio of 17 percent (i.e., the existing 9 percent plus another 8 percentage points).

- (iv)

- This means that the bank would have to hold a total capital adequacy ratio of more than 20 percent, once additional requirements to make up T1 and total capital are included, and even before taking into account possible items such as D-SIB or G-SIB surcharges.

- (v)

- If the baseline scenario were to materialize, the bank would be carrying a CT1 ratio of 15 percent (i.e., 17 percent less the 2 percentage points impact).

Private sector stress tests of the Spanish banking sector in 2011–2012 applied similarly stringent assumptions. Their huge estimates of the recapitalization needs of the banks were presaged on projected losses of up to half, CT1 thresholds of up to 11 percent and a capital hole of up to €120 billion (Box Table 1). As it turned out, the baseline growth scenario for 2012 eventually became the actual outcome (Box 1).

Box Figure 2.

Hypothetical Recapitalization Estimations (In percentage points) 1/.

Box Table 1.

Spain: Market Estimates of Bank Recapitalization Needs with Associated Hurdle Rates.

| Study | Expected

Losses 1/ | CT1

Threshold | Recapitalization Needs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (In percent) | (In percent) | (In billions of euro) | ||||

| 1 | 14 | 10–11 | 79–86 | |||

| 2 | 11–14 | current level | 65 | |||

| 3 | 9 | … | 80 | |||

| 4 | 14 | 10 | 45–55 | |||

| 5 | 16 | 10 | 33–57 | |||

| 6 | 16 | 9 | 90 | |||

| 7 | … | 11 | 68 | |||

| 8 | … | current level | 54–97 | |||

| 9 | 51 | … | 58 | |||

| 10 | 11–19 | RDL 2/2011 | 45–119 |

Source: IMF [28].

4.1.6. Transparency

4.1.6.1. Objective, Action Plan and Financial Backstop