1. Introduction

Corporate tax planning has attracted unprecedented attention in recent years, with both academic researchers and financial media emphasizing cross-jurisdictional income and debt shifting as major drivers of corporate tax minimization. Broadly defined, tax planning encompasses the set of strategies multinational corporations (MNCs) employ to exploit differences and interactions within the international network of tax systems and regulatory frameworks in which they operate (

Beuselinck & Pierk, 2022).

The OECD in a report on “base erosion and profit-shifting” (BEPS) (

OECD, 2015) even argues that a failure to take action against profit-shifting by multinationals would put ”the integrity of the corporate income tax” at stake (

OECD, 2013;

Nielsen et al., 2014). While in OECD countries corporate tax is, relatively, not an important source of revenue, this is not true in developing countries, which have much more at stake in an effective international tax system because their development depends on it (

Oguttu, 2016).

Laudage (

2020) emphasized that corporate tax revenues and foreign direct investment are important sources of development finance in developing countries. Moreover, the nature and intensity of tax-planning concerns vary significantly between advanced and developing economies. Developing countries, in particular, face heightened challenges, as they are often more vulnerable to the erosion of their tax base, which undermines revenue mobilization and fiscal stability (

de Mooij et al., 2021). This imperative has become even more pronounced in the wake of the Ukrainian war and in particular of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has exacerbated existing fiscal vulnerabilities and placed additional pressure on developing country budgets (

OECD, 2021b).

It is well known that tax incentives are used for investment attractiveness and to signal ease of conducting business in a country, as they reduce barriers for investments and indicate the host nation’s level of acceptance of foreign players in markets where incentives are instituted (

UNCTAD, 2015). However, cross-country differences in corporate income tax lead multinationals to find strategies in order to diminish their tax liabilities. Many MNCs pay low or no corporation tax in high-tax countries because they shift taxable income (

Bilicka et al., 2024). In this regard, the mispricing of intracompany purchases of goods and services represents a common way to minimize the fiscal burden (

Azémar & Corcos, 2009;

Buettner et al., 2018;

Cools & Clive, 2006;

de Mooij et al., 2021;

Dharmapala, 2019).

Profit shifting by multinational corporations (MNCs) has been widely analysed as a key mechanism driving tax base erosion, particularly in the presence of corporate income tax (CIT) differentials across jurisdictions. Empirical research, notably by

Fuest and Riedel (

2010) and

Heckemeyer and Overesch (

2017), shows that MNCs strategically exploit cross-border tax differentials through transfer pricing and intra-group debt arrangements. These practices not only distort the allocation of taxable profits but also affect real investment decisions by altering the effective tax burden on capital across affiliates.

Heckemeyer and Overesch (

2017) find evidence that profit shifting is largely driven by non-financial intercompany transactions

1. Conducting a comprehensive meta-analysis of 27 empirical studies published over the past 25 years, the authors employ meta-regression techniques to quantify how MNCs respond to international differences in corporate tax rates. Their analysis reveals a substantial sensitivity of reported profits to tax-rate differentials across countries. The authors report an estimated tax semi-elasticity for earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) of 0.543. Overall, the paper’s findings may be cautiously interpreted as some sort of a “consensus” or typical estimate, reflecting the general scale of profit-shifting activity and its responsiveness to international corporate income tax differentials, based on all the available empirical evidence and adjusted for potential estimation and publication biases.

While extensive empirical research has examined profit-shifting behaviour in advanced economies, studies on profit-shifting in developing countries are scarce, and many existing studies on tax avoidance are difficult to interpret, mainly because the measurement concepts used have a number of drawbacks

2. It remains puzzling that most studies do not give attention to developing countries. One obvious reason for this lack of evidence is that developing countries largely show weak disclosure requirements and a persistent lack of reliable micro-level data, which constrain rigorous econometric investigation into MNCs’ profit-shifting practices (

Janský & Prats, 2015). Several studies (

Crivelli et al., 2016;

Fuest & Riedel, 2010;

Lohse & Riedel, 2013;

Trøsløv et al., 2018;

UNCTAD, 2015) have emphasized the need for deeper empirical inquiry into this underexplored search area. In recent years, a number of datasets have become available that may be suitable for this purpose (

Fuest & Riedel, 2010).

Crivelli et al. (

2016) performed an empirical analysis that quantifies the possible effects of BEPS in developing countries and suggests, quite strongly, that base erosion, profit-shifting, and international tax competition really matter for developing countries; moreover, they may well matter at least as much as for advanced economies. The authors estimate that developing economies lose between 1% and 2% of GDP annually due to base erosion and profit-shifting (BEPS), with profit relocations responding strongly to tax rate differentials. Similarly,

Beer et al. (

2020) quantify the semi-elasticity of declared profits to statutory tax rates at around −0.8, confirming that MNCs’ reporting behaviour remains highly sensitive to international tax differentials even under modern anti-avoidance regimes. At a regional level,

Janský and Prats (

2015) and

Janský and Miroslav (

2019) analyse developing and African economies, respectively, finding that profit-shifting is most pronounced in countries with weaker institutional capacity and high tax incentives. They show that MNCs in developing regions tend to under-report profits in higher-tax countries while over-reporting in tax-preferred jurisdictions, creating distortions in capital allocation and investment behaviour.

Crivelli et al. (

2016) further argue that tax competition among developing economies exacerbates profit-shifting, as governments often lower statutory rates or provide selective tax holidays to attract FDI, thereby eroding the domestic tax base. These findings align with

Fuest and Riedel (

2010), who emphasize that investment decisions by MNCs are not purely efficiency-driven but strategically influenced by the opportunity to reallocate taxable profits.

This study aims to address this empirical gap by examining tax-induced profit-shifting in Morocco. In this regard, Morocco provides a particularly insightful case for analyzing the tax behaviour of multinational corporations (MNCs). Over the past decades, the country has undertaken significant fiscal reforms and introduced a range of investment incentives aimed at attracting foreign capital and fostering economic growth. However, these same fiscal incentives may have unintended consequences, potentially facilitating profit-shifting practices through tax rate differentials and intra-firm pricing mechanisms. Despite significant global evidence, empirical analysis specific to North Africa, and Morocco in particular, remains limited. Policy-oriented studies by the

OECD (

2021a) and

IMF (

2022) suggest that Morocco’s tax regime displays structural asymmetries that may incentivize profit-shifting, notably through preferential regimes for export-oriented sectors and in part inconsistent enforcement of transfer pricing documentation. However, to the best of our knowledge, no prior empirical research has systematically quantified how MNCs’ reported profits in Morocco respond to CIT differentials using firm-level data.

This study has three main objectives. First, it aims to empirically assess the responsiveness of profit, proxied by earning before interest and taxes (EBIT), to the corporate income tax differential (CIT

Δ), which is indirect evidence of profit-shifting behaviour

3. Second, this paper investigates how the internal capital investment, proxied by shareholders’ funds, moderates the effect of CIT

Δ on EBIT; thereby we put the focus on potential investment distortions induced by corporate income tax. Third, this study assesses the impact of key macroeconomic factors, shocks, and institutional quality indicators on the profitability of MNC subsidiaries

4 in Morocco over the observation period, thus seeking a broader understanding of the effects on subsidiaries’ EBIT in a developing country context.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides an overview of Morocco’s economic and regulatory context, highlighting the relevance of the country as a case study for examining profit-shifting behaviour.

Section 3 outlines the research methodology adopted in this study.

Section 4 develops the conceptual framework that underpins the analysis and serves as the theoretical foundation for the research hypotheses.

Section 5 describes the constructed dataset used in the empirical investigation and summarizes its key descriptive statistics.

Section 6 details the empirical strategy and presents the estimation of the pseudo-ordinary least squares (POLS) regression model.

Section 7 reports the main empirical results along with a set of diagnostic tests and robustness checks.

Section 8 discusses the findings in relation to the existing literature, and

Section 9 concludes by outlining the main implications and suggesting avenues for future research.

2. Moroccan Context

Our empirical work focuses on MNCs’ controlled subsidiaries operating in Morocco for the following reason. The kingdom’s economic context is characterized by combining extremely highly diversified foreign economic partnerships through a range of free trade agreements, cooperation accords, and strategic initiatives (with 12 free trade agreements, Morocco offers market access to some 100 countries worldwide, representing almost 2.5 billion consumers) (

OECD, 2024). Furthermore, the country is strategically orientated toward developing an integrated economy within the global businesses. Morocco’s increasing ability to serve as a bridge between the West and China has earned it the nickname of “global connector” (

Bloomberg, 2024). Various international institutions recognize the model of integration of the Moroccan economy in the different global value chains as an effective model (

Amachraa & Quelin, 2022).

Morocco’s corporate tax system exhibits notable heterogeneity, with statutory CIT rates ranging from 10% to 35% depending on income brackets and sectoral regimes. Export-oriented firms enjoy preferential treatment under investment incentive codes, while recent BEPS-aligned reforms have tightened transfer pricing documentation and information exchange requirements. The World Bank’s Rule of Law Index for Morocco shows a score of −0.13 in 2023 on the −2.5 to +2.5 scale (where higher values indicate stronger rule of law) (

World Bank, 2023). According to the World Governance Indicators, Morocco’s regulatory quality percentile ranking remains below the global median, highlighting constraints in policy formulation and implementation (

CEIC Data, 2024). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Public Integrity Indicators country fact-sheet reports that Morocco meets 100% of the regulatory standards for political finance under OECD metrics and 78% of the criteria for public information transparency (

OECD, 2025). The World Justice Project Rule of Law Index ranks Morocco 91st out of 143 countries in 2025, with a score of 0.48 on their 0–1 scale (where higher is better) (

WJP, 2025). These measurable features describe Morocco’s institutional environment, highlighting the relevance of the country as a case study for examining profit-shifting behaviour.

The country is classified as a middle-income economy, with a gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of approximately USD 4240 in 2023

5. Morocco is the EU’s 18th biggest trade partner (1.2% of the EU’s total trade in goods with the world in 2024) among the southern neighbourhood countries. Total trade in goods between the EU and Morocco in 2024 amounted to EUR 60.6 billion. The EU is also the biggest foreign investor in Morocco

6. However, according to

UNCTAD (

2020) Morocco exhibited significant and increasing trade mispricing of USD 16.6 billion from 2013 to 2014. The total tax revenue as a percentage of GDP was

, slightly above the average for developing economies, which typically ranges between

and

. When narrowing the focus to CIT tax as a share of total tax revenue, Morocco’s CIT constituted

in 2022 and increased slightly to

in 2023. According to UNCTAD statistics

7, this remains just above the developing country average, which was estimated at

for the same period. In contrast, developed economies recorded a lower CIT share of total taxes, averaging around

, reflecting their broader and more diversified tax bases that rely more heavily on income and consumption taxes. In terms of tax policy performance, corporate tax receipts in Morocco accounted for approximately

of GDP in 2023, which is relatively aligned with the developing country average of

, as reported by the IMF Fiscal Monitor

8.

In November 2009, Morocco adhered to the OECD Declaration on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises following an initial Investment Policy Review. Morocco has since become an associate member of the OECD’s Investment Committee and participates actively in its work (

OECD, 2024). Recent initiatives, including the OECD’s base erosion and profit-shifting (BEPS) framework, have encouraged countries to strengthen their tax governance and transparency. However, the challenge for developing economies lies in aligning these global standards with domestic investment strategies. Understanding this balance between compliance and competitiveness is key to effective tax policy. Morocco has a general provision within its tax legislation, through Article 214 of the General Tax Code (Code Général des Impôts), requiring transactions between related parties to be at arm’s length

9. On 25 June 2019, Morocco signed the Multilateral Convention to implement tax treaty-related measures to prevent BEPS. The Convention is the first multilateral treaty of its kind, allowing jurisdictions to integrate results from the OECD/G20 BEPS Project into their existing networks of bilateral tax treaties. The Convention, negotiated by more than 100 countries and jurisdictions under a mandate from the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, is one of the most prominent results of the OECD/G20 BEPS project. It is the world’s leading instrument for updating bilateral tax treaties and reducing opportunities for tax avoidance by multinational enterprises

10. The Dahir implementing Law 75-19 ratifying this convention was adopted on 31 December 2020. By publishing it in the official bulletin of 18 January 2021, Morocco officially joined the countries that are part of the fight against tax evasion on a global scale.

After establishing the economic and regulatory context of Morocco, the following section presents the research methodology employed in this study.

3. Search Methodology

Theoretically, we first develop our conceptual framework with a representative MNC to formulate our hypotheses. Our starting point is a tax-savvy MNC in its ability to abuse transfer prices, which represent a predominant instrument to maximize the MNC’s overall after-tax profit. Since the distinctive feature of multinationals that allows them to avoid taxation is their ability to coordinate internal pricing and production decisions, it is not surprising that tax planning should be easier for some multinationals than for others (

Azémar & Corcos, 2009). Thus, our representative MNC exploits the CIT

Δ and optimally adjusts the transfer price to shift subsidiaries’ taxable income.

In principle, national tax laws and regulations require that transfer prices adhere to the arm’s length principle, meaning that intra-group transactions should be valued as if they were conducted between independent entities under comparable market conditions. In practice, however, information asymmetries between multinational corporations (MNCs) and tax authority enable firms to manipulate pricing structures—for instance, by setting artificially high or low transfer prices on transactions between affiliates located in high- and low-tax jurisdictions. Such practices allow MNCs to shift profits strategically across borders, thereby reducing their consolidated tax burden (

de Mooij & Liu, 2020). We formally demonstrate that the MNC optimally adjusts the transfer price based on the marginal benefit from the CIT

Δ and the marginal costs incurred due to mispricing of intra-firm sales. A tax-savvy MNC, when faced with exogenous foreign country CIT that differs from home country CIT, will optimize its transfer prices based on the CIT

Δ to maximize its worldwide after-tax profits.

In our conceptual framework (

Section 4), which builds upon the theoretical model developed by

de Mooij and Liu (

2020), the parent company determines the optimal level of internal capital investment in its foreign-controlled subsidiary. The existing literature consistently shows that corporate taxation raises the cost of capital faced by multinational enterprises, thereby discouraging or dampening investment activity (

Alvarez-Martines et al., 2022;

Beer et al., 2018;

Desai et al., 2004;

Devereux, 2007;

Hanappi et al., 2023). In this respect, our study investigates how internal capital investment, proxied by shareholders’ funds, moderates the effect of CIT

Δ on EBIT; thereby we put the focus on potential investment distortions induced by corporate income tax. This moderation effect is particularly relevant in the context of our study for two reasons. First, it is relevant because effective intra-group profit-shifting typically requires a substantial ownership stake that meets or exceeds a minimum shareholding threshold. Generally, the higher the level of ownership, the greater the degree of control exercised by the owner of equity shares. This increased control enables the MNC to influence and/or define strategic and operational decisions of its affiliates, especially in relation to transfer pricing policy. Second, since equity financing is not tax-deductible, in the presence of corporate taxation the parent will invest in its subsidiary up to the point where the after-tax marginal product of capital equals the gross cost of capital. Therefore, we argue that the impact of the CIT differential on profit is moderated by MNC capital investment, proxied by shareholders’ funds. However, according to investment distortion theory, elevated tax burdens increase the marginal cost of capital, thereby constraining MNCs’ investment in their controlled subsidiaries.

Empirically we follow the micro-level data approach

11. The empirical analysis relies on a dataset of foreign-owned subsidiaries operating in Morocco. We construct a panel dataset in the period between 2014 and 2023. The full dataset comprises 2580 firm-year observations. We obtain firm-level financial data from the Bureau Van Dijk TP Catalyst database based on national accounting and tax filings. The dependent variable, subsidiaries’ earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT), measures the profitability reported in Morocco. The key explanatory variable is the corporate income tax (CIT) differential CIT

Δ, which is defined as the difference per annum between Morocco’ s CIT rate and that of the subsidiary ultimate owner’s country. To capture firm-level heterogeneity, we use shareholders’ funds as a proxy for internal capitalization and investment capacity. Additional controls encompass GDP (macroeconomic environment), BEPS implementation, COVID-19 shock, and institutional quality indicators. We express an estimate using the pseudo-ordinary least squares (POLS) regression model. The POLS estimator extends the traditional ordinary least squares (OLS) approach to pooled panel data, integrating both cross-sectional and time-series dimensions. This estimator is particularly appropriate when the primary objective is to capture overall relationships across firms and time. Unlike standard OLS, which captures only cross-sectional variation, POLS utilizes both temporal and cross-sectional information. The choice of a pseudo-ordinary least squares (POLS) estimator is motivated by the structure of our dataset. The dataset exhibits an unbalanced panel structure with uneven firm participation across years. Although fixed and random effects models were initially considered, the limited time span (2014 to 2023) and data imbalance across firms would eliminate much of the useful cross-sectional information and therefore reduce the model significant explanatory degree. The estimate links subsidiaries’ EBIT to the CIT differential between Morocco and that of the subsidiary foreign ultimate owner’s

12 country in the observation period 2014 to 2023, while accommodating the interaction between tax policy variables, capital structure, and institutional factors. In related studies examining the relationship between earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) and corporate income tax (CIT) differentials (see

Heckemeyer & Overesch, 2017), a significant correlation between the EBIT of MNCs’ controlled subsidiaries and the prevailing tax differential is interpreted as indirect evidence of profit-shifting behaviour. According to our MNC theoretical model (

Section 4), the incentive to misprice sales between related parties is exclusively driven by the CIT

Δ between jurisdictions. The MNC optimizes its transfer prices based on the CIT

Δ to maximize its worldwide after-tax profits. Further, we follow

Hanappi et al. (

2023) in assessing the moderating effect of shareholders’ funds as a theoretically grounded proxy for the parent capital investment in its subsidiary. Subsidiaries with greater capital at stake would typically exhibit stronger sensitivity to corporate income taxation. Our finding highlights the strategic role of capitalization in enabling profit-shifting through transfer pricing mechanisms. It underscores the importance of shareholders’ funds not only as a determinant of financial capacity but also as an enabling element of tax-motivated profit allocation.

To ensure the reliability of our estimates, several diagnostic checks were performed. In this regard, we follow

Osmari et al. (

2013) and

Warith et al. (

2016), using traditional ordinary least squares (OLS) diagnostics to ensure the statistical validity and robustness of the empirical findings derived from the POLS regression model. The literature shows that the pseudo-linear form, while nonlinear in variables, retains the required linearity in parameters for traditional OLS-based validation. To address heteroskedasticity, we employed the White tests, confirming constant error variance (see diagnostic tests and plots). The regression was therefore estimated using robust (Huber–White) standard errors. Sensitivity analyses and the Box–Cox transformation confirm that the sign and magnitude of coefficients remained stable. In summary, the pseudo-OLS estimation provides a reliable and interpretable framework for assessing how multinational subsidiaries in Morocco respond to corporate income tax differentials. The additional diagnostic and robustness procedures confirm the internal validity of the model and support the causal interpretation of tax-induced profit-shifting behaviour.

Our study is related to the growing body of literature (

Crivelli et al., 2016;

Dharmapala, 2019;

Fuest & Riedel, 2010;

Janský & Prats, 2015;

Trøsløv et al., 2018;

UNCTAD, 2015;

Wier, 2020) that investigates profit-shifting behaviour by MNCs, including reported profits in developing countries. The paper adds to the existing literature by proposing a conceptual framework that isolates the tax-induced incentives affecting profit, moderated by internal capitalization, and highlights the resulting investment distortions caused by corporate income taxation. Thereby, we adopt an integrated approach that combines theoretical modelling and empirical analysis to investigate the causal mechanism through which tax differentials influence transfer pricing behaviour and investment distortions in developing economies. The empirical analysis employs firm-level data and a pseudo-OLS framework to test the derived hypotheses.

This paper is also directly related to the larger literature on taxation and business investment (

Bilicka et al., 2024;

Buettner et al., 2018;

Galindo & Pombo, 2011;

Hanappi et al., 2023;

Laudage, 2020). In this context, this study integrates macroeconomic factors, shocks, and institutional quality indicators, offering a broader perspective on the effects on subsidiaries’ EBIT in a developing country context. A further contribution lies in integrating the profit-shifting cost function into our conceptual framework (see

Section 3), a function developed in our previous paper (

Rachidi & El Moudden, 2023). This approach ensures conceptual continuity, enhances the development of our conceptual framework, and further formulates our theory hypotheses. Finally, our findings hold significant relevance for regulators, academics, and policymakers, as they provide empirical evidence of tax-driven profit-shifting within the Moroccan context. To the best of our knowledge, our paper is the first attempt at assessing the link between the corporate income tax rate differential and multinational profit behaviour in Morocco.

The next section develops the conceptual framework of our study.

4. Conceptual Framework

This section outlines the conceptual framework underlying the empirical analysis and serves as the theoretical basis for formulating the study hypotheses. Following

Bernard et al. (

2006), we consider an explicit partial equilibrium approach to the problem of transfer pricing in that we take the location of firm activity as given

13. Consider a representative vertically integrated MNC composed of a parent firm

M in country

h and its controlled

14 subsidiary

a in country

s. The parent company determines the amount of capital

k to invest in its foreign subsidiary

a. For analytical simplicity, it is assumed that this investment is entirely equity-financed

15. The cost of capital

r is treated as exogenously determined in the global capital market, reflecting the assumption that both countries are small open economies with no influence over the world rate of return, which is identical across locations. We follow the standard OECD corporate income tax codes by considering that the costs of equity

r are not tax-deductible. Therefore, in line with

Loretz and Mokkas (

2015), through empirical search, we consider that the corporate income tax increases the cost of capital faced by MNCs. It is well known that higher tax burdens distort corporate investment. Subsidiaries with greater capital at stake would typically exhibit stronger sensitivity to corporate income tax rates (

de Mooij & Liu, 2020). In this regard,

Hanappi et al. (

2023) find that capital intensity modulates tax sensitivity. The authors use Orbis firm-level data to show heterogeneity in investment sensitivity to corporate income tax, where larger, more capital-intensive MNC subsidiaries show stronger negative investment responses to tax. Since equity financing is not tax-deductible, it implies that the foreign subsidiary must generate a gross return sufficient to satisfy the parent’s expectations.

The parent produces an intermediate input

x in country

h at constant marginal cost

q and transfers it free-on-board to its foreign subsidiary

a at a transfer price

. Alternatively, the parent could source the intermediate good

x from the market

16 at price

p. The foreign subsidiary uses the imported intermediate input good

x and capital

k to produce the final output

y, sold at a normalized price of 1. The subsidiary uses a standard neoclassical production function

, which features decreasing returns in each of the two inputs capital

k and intermediate input good

x. In the absence of taxes, the transfer price is simply an arbitrary accounting device for the MNC; for a given transfer price

, the parent and the subsidiary profits are, respectively, given by

and

. Clearly, the MNC´s global before-tax profits are equal to

, from which we can see that the transfer price

has no effect on the global profit of the MNC.

Let us assume that both countries impose taxes on the profits of firms operating within their respective jurisdictions, representing the sole policy instrument available to their governments, and that group taxation does not apply. According to the prevailing international standard of separate accounting, each entity within a MNC is treated as a distinct taxable unit, with profits assessed independently. This approach aligns with both countries applying the separate accounting method for taxing the profits of MNCs. Let

and

denote the CIT set by the parent and the controlled subsidiary tax authority, respectively. When the parent

M supplies

x to its subsidiary

a, it charges a transfer price

that deviates from the (arm’s length

17) market price

p. We do not take into consideration production allocation decision problems or any incentive of managers

18. For the sake of simplicity, our analysis concentrates exclusively on price distortions arising from intra-firm sales transactions. The transfer price

is typically not directly observable by tax authorities in country

h and in country

s. This information is not disclosed by firms. When the parent firm

M wilfully deviates the transfer price from the market price (the arm’s length price) to strategically reallocate profits across tax jurisdictions, it incurs a range of profit-shifting costs, e.g., concealment (transaction) costs or contingent costs, such as penalties, legal disputes, and reputational damage if the manipulation is detected by tax authorities or challenged in court. For simplification reasons, the profit-shifting costs are assumed to be non-tax-deductible. Following

Rachidi and El Moudden (

2023) we assume that total profit-shifting costs increase quadratically with the weighted deviation of the transfer price from the market price (arm’s length). The cost function is defined as

In the representative MNC model described above, the parent M earns direct income from the sale of the intermediate input good x, which is taxable at rate , and incurs the cost of financing k and the expected shifting costs of deviating the transfer price from the market price (arm’s length price).

The parent’s after-tax profit is given as follows:

and that of the subsidiary as

The total global after-tax profit is

4.1. MNCs’ Global Profit Maximization

Corporate income tax varies across countries. We assume that the exemption method is in place. This is a reasonable assumption since it is widely used in most OECD countries and it implies that repatriated profit income is exempt from taxation. Accordingly, the parent

M receives the profit from the affiliate

, which is taxable at rate

. The MNC maximizes its overall after-tax profit with respect to the capital, intermediate input good, and transfer price.

Taking the first derivative equal to zero and solving, we get the following first order conditions:

With reference to (

5), the first-order conditions for capital investment can be written as

Equation (

8) expresses the equality between the marginal product of capital

and its effective marginal cost, given by

. Because equity financing is not tax-deductible, the cost of capital reflects the gross return required by investors rather than a net return after tax. As a result, the required productivity of capital is higher than the market interest rate

r. This condition represents the standard neoclassical investment rule in the presence of corporate taxation: firms invest up to the point where the after-tax marginal product of capital equals the gross cost of capital. Importantly, transfer price mispricing does not directly affect the optimal capital allocation; its influence on

k is only indirect, through the input quantity

x that interacts with capital in production. An increase in the host country’s tax rate

raises the effective cost of capital, thereby reducing the attractiveness of investment unless the marginal capital productivity increases accordingly. This captures in our theory model the investment distortion induced by source-based corporate taxation. Since equity financing is not tax-deductible, firms must earn a gross return (before tax) high enough to satisfy the investor. Therefore, a higher corporate income tax differential (

) implies a higher cost of capital, and subsequently under-investment in country

a occurs.

With reference to (6), the first-order conditions for intermediate input good

x are given by

Equation (

9) determines the condition under which the marginal product of the intermediate input

equals its respective marginal cost. This perceived cost includes three components: (i) the market price

p, (ii) a fiscal distortion term reflecting the tax differential

, and (iii) the marginal cost of profit-shifting through transfer mispricing. Specifically, when

, the MNC has an incentive to increase the transfer price

, thereby raising the internal cost of the input for the subsidiary. This fiscal distortion inflates the perceived input cost and alters the optimal demand for

x. Consequently, the input allocation is no longer guided solely by production efficiency, but also by tax arbitrage considerations. This reveals a critical trade-off between productive efficiency and tax minimization. The condition also confirms the link between the transfer price and production through its effect on the subsidiary’s input decision.

With reference to (7), the first-order conditions with respect to the transfer price

yield

with

, which denotes the marginal cost of deviating the transfer price from the market price (arm’s length price).

Equation (

10) characterizes the optimal transfer price

as the point where the marginal benefit from tax saving equals the marginal cost incurred due to transfer mispricing, captured by

. This condition reveals that the incentive to misprice is exclusively driven by the corporate income tax (CIT) differential between the two jurisdictions. When, e.g., the subsidiary is located in a higher-tax jurisdiction than the parent (

), the tax-savvy MNC has an incentive to set the transfer price

above the market price

p. Through this overpricing of intra-firm transactions, the MNC shifts taxable profits from the high-tax subsidiary’s country to the low-tax parent’s country. Assuming a convex cost function, the marginal cost of mispricing increases with the magnitude of the deviation from the market price. This feature implies an upper bound on the extent of profit-shifting, as the marginal cost of mispricing rises rapidly with larger deviations. When both the parent and the controlled subsidiary are located in the same country or face identical CIT rates (

), no trade-off will take place. The right-hand side of Equation (

10) implies that no mispricing incentive exists, and thus the optimal transfer price equals the market price

. This result shows the key role of the

. The derived equation shows that the MNC optimally adjusts

as a function of the

. When

taxable profits are shifted from the high-tax country

a to the low-tax country

h. On the other hand, if CIT rates converge, the incentive to manipulate the transfer price disappears.

In summary, tax rate differentials across jurisdictions create an incentive for MNCs to shift taxable income from high-tax to low-tax affiliates. This is primarily achieved through transfer pricing, where internal prices for goods or services deviate from the market price (arm’s length price) values to reallocate profits. Such behaviour generates investment distortions, as MNCs may over-invest in low-tax jurisdictions to substantiate transfer pricing positions, while under-invest in high-tax locations despite potential productivity advantages. Consequently, tax policy influences both the spatial allocation of profits and capital investment.

4.2. Hypotheses

The conceptual MNC model presented above serves as the analytical basis for deriving our main hypotheses, which are formulated in conjunction with our country case Morocco as follows:

Hypothesis 1. A higher corporate income tax rate differential (CITΔ) between Morocco and the parent company’s country is associated with a decrease in the reported EBIT of MNC-controlled subsidiaries operating in Morocco.

This hypothesis isolates the tax-induced incentives on profit. If Morocco becomes less attractive from a tax perspective relative to the parent company’s country, MNCs are expected to shift profits toward lower-tax jurisdictions, thereby reducing subsidiaries’ reported EBIT through mispricing of intra-firm sales, which is indirect evidence of tax-motivated profit-shifting behaviour.

Hypothesis 2. The effect of CITΔ on EBIT varies with shareholders’ funds (SHFs). However, a higher increases the cost of capital, and thereby the MNC’s investment in its controlled subsidiary decreases.

In line with the literature (see

Galindo & Pombo, 2011;

Hanappi et al., 2023), we consider that when

19 increases, elevated tax burdens distort investment incentives by increasing the marginal cost of capital, thereby constraining corporate investment.

Hypothesis 3. A higher level of institutional quality indicators in Morocco is associated with higher subsidiary reported operating profits EBIT.

This hypothesis reflects that a more stable, clear, and predictable legal tax regulatory environment should positively influence investment decisions and therefore enhance subsidiaries’ profitability.

In this section we develop a simple representative MNC theory model to formulate our hypotheses. Now, we turn in the next

Section 5 to describe the full constructed dataset for the empirical analysis in

Section 6.

7. Empirical Results

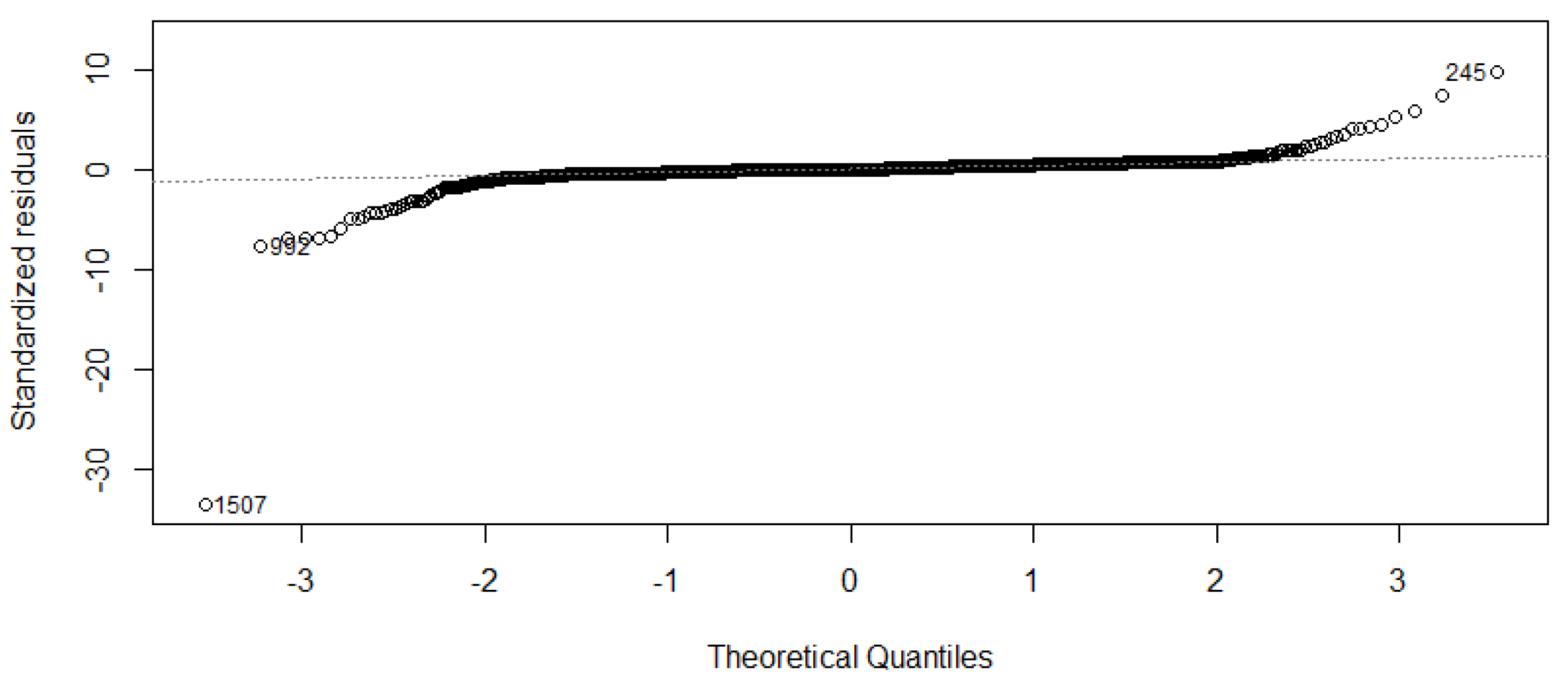

The section presents the empirical results of our study, including validation tests and robustness checks. All statistical analyses and tests were conducted using RStudio (Version 2024.09.1+496). We begin by reporting the estimate results and the POLS regression model overall fit. We then present the estimated coefficient results and analyse the magnitude, direction, and statistical significance of each, along with diagnostic plots (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) and economic interpretability.

7.1. Estimation Specification Results

Table 2 summarizes the estimate results of the POLS regression model based on Equation (

11). The table shows the estimated coefficients of the explanatory variables along with the corresponding standard errors and the significance levels.

The number of observations is 2440, confirming that the empirical results are based on a large and robust sample size. The POLS regression model is highly significant overall, as evidenced by the Fisher statistic (, ), indicating a significant explanatory degree. The adjusted coefficient of determination shows that the model explains approximately of the variation of the dependent variable EBIT, reflecting a very good fit. All coefficients are significant, confirming their individual explanatory contribution to the model accuracy.

Table 3 summarizes the magnitude, direction, and statistical significance of each variable effect, allowing for a consistent interpretation of the statistical and economic relevance of each predictor. All coefficients are statistically significant at the

level, reinforcing the model’s robustness. In the following, we present the economic interpretation of the estimated coefficient results.

Corporate income tax differential (): The coefficient shows a negative and highly significant effect on EBIT. A one-unit increase in the corporate income tax differential is associated with a EUR 85,448 decrease in EBIT. This aligns with our theoretical expectation (Hypothesis 1) that a higher CIT differential leads to EBIT decreases and thereby shifting of taxable income. For a median-sized subsidiary, this represents approximately 2.4% of annual earnings.

Shareholders’ funds (SHFs): The coefficient is positive and significant, indicating that higher shareholder funds (proxy for the parent capital investment) are positively associated with EBIT. Each additional euro of SHF increases EBIT by , highlighting the capacity of well-capitalized firms to generate profit. This aligns with conventional financial theory: better-capitalized firms exhibit higher operational performance, possibly due to greater financial flexibility and a reduced need for external financing.

Interaction term (× SHF): The interaction term between the CIT differential and shareholder’ funds is significantly positive at ; the effect of on EBIT varies with shareholder fund intensity. However, contrary to expectation (Hypothesis 2), based on investment distortion theory, well-capitalized subsidiaries, although they are responsive to fiscal asymmetries, do not reduce their investment in response to higher capital costs. Instead, they appear to offset such fiscal asymmetries, possibly because marginal capital productivity increases sufficiently to compensate the higher cost, along with more advanced tax planning.

Gross domestic product (GDP): The positive coefficient (∼MAD 75.9 million per unit increase in GDP) indicates that overall economic growth in Morocco is associated with improved business performance and higher reported EBIT among subsidiaries.

BEPS legislation (BEPS): The implementation of the anti-avoidance measures (BEPS) in 2019 correlates with a significant reduction in EBIT. The large significantly negative effect (∼−EUR 8.2 million) implies that the BEPS framework has been effective in curbing aggressive profit-shifting behaviour among MNCs operating in Morocco.

COVID-19 crisis (COV): The large significant negative effect (∼−EUR 5.8 million) highlights the strong economic impact of the pandemic. This result reflects disruptions in operations, supply chains, and demand, all contributing to a higher drop in subsidiaries’ profitability.

Institutional quality: Rule of law (WGIRL): The positive effect (∼EUR 577,000) indicates that stronger enforcement of legal norms, such as contract enforcement and property rights, enhances firm performance. A predictable legal environment reduces investment risk and improves corporate governance.

Regulatory quality (WGIRQ): The higher positive effect (∼EUR 1.08 million) suggests that regulatory clarity and stability substantially support operational efficiency and investment confidence. Subsidiaries operating under well-designed and consistently applied regulations are better able to perform. Both institutional variables rule of law and regulatory quality have positive and statistically significant effects. This aligns with our theoretical (Hypothesis 3) expectation.

The following subsection presents the conducted diagnostic tests along with the respective results and a summary synthesis.

7.2. Diagnostic Tests

To test the statistical validity of the obtained empirical results, we follow

Osmari et al. (

2013) and

Warith et al. (

2016), using traditional ordinary least squares diagnostics tests, which are presented in this section

32. In this regard, we applied the White test for heteroskedasticity, the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality of residuals, the Durbin–Watson test for autocorrelation, and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to assess multicollinearity. These tests collectively evaluate the extent to which the classical assumptions of linear regression are satisfied. Together, the diagnostic plots (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) evaluate the normality assumption of residuals. A summary synthesis consolidates the test results.

The White Test: The result of the White test shows a Breusch–Pagan statistic (BP) of 1.5972 with two degrees of freedom and a corresponding p-value of 0.45. Given that the p-value exceeds conventional significance levels (e.g., 0.05), we do not reject the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity. This outcome suggests that there is no statistically significant evidence of heteroskedasticity in the POLS regression model, thereby supporting the assumption of constant error variance.

The Shapiro–Wilk Test: The test shows a W statistic of 0.38456 with a p-value less than 2.2 , indicating a rejection of the null hypothesis of normally distributed residuals. The test clearly indicates that the residuals deviate substantially from a normal distribution. However, this does not invalidate the regression itself as long as the sample size is sufficiently large. According to the central limit theorem, coefficient estimates remain approximately normally distributed in large samples, and hypothesis test results can still be valid, particularly if robust standard errors are used.

The Durbin–Watson Test: The result of the Durbin–Watson test indicates a statistically significant presence of positive autocorrelation in the residuals, as shown by a p-value of 7.349 . The test statistic, DW = 1.7597, which is below the benchmark value of 2, confirms this.

The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) Test: The results of the VIF test show that all VIF values remain below the commonly accepted critical threshold of 10, suggesting the absence of severe multicollinearity among the explanatory variables. The highest observed VIF values relate to SHF (7.50) and GDP (6.90), indicating moderate multicollinearity. While this does not undermine the overall stability of the estimate, it suggests that these explanatory variables should be monitored when interpreting their individual coefficient effects.

Figure 1 illustrates the standardized residuals from the POLS regression model plotted against the theoretical quantiles of a normal distribution. This diagnostic plot is used to assess whether the residuals approximately follow a normal distribution. The plot indicates that the residuals are approximately normally distributed, as most points align closely with the theoretical quantile line. Minor deviations in the tails suggest the presence of outliers.

Figure 2.

Histogram residuals.

Figure 2.

Histogram residuals.

Figure 2 displays the distribution of residuals from the POLS regression model. This diagnostic plot is useful for evaluating the normality assumption of the residuals. The histogram of residuals indicates that the majority of residuals are concentrated around zero, consistent with an unbiased model fit. However, the presence of extreme residuals introduces asymmetry in the distribution.

7.3. Outlier and Influential Observation Analysis

The diagnostic assessment of outliers and influential observations shows several important characteristics of the dataset that must be considered when interpreting the empirical results. This diagnostic step is essential to identify atypical observations.

Outliers: Studentized residuals beyond standard deviations indicate significant deviations from the estimate’s predicted values. In our sample, several observations exceed this threshold, with observation 1507 showing a particularly extreme residual of . Such residuals suggest that the estimate fails to accurately capture the behaviour of these subsidiaries. This may stem from specific contextual factors, e.g., unique financial structures or operational anomalies that deviate from the broader sample characteristics.

Influential Observations (Cook’s Distance): Observations such as 16, 260, and 1968 exhibit high Cook’s distances, indicating that their combined leverage and residual magnitude significantly affect model estimation. The identification of over 30 influential observations suggests that a portion of the data exerts an outsized influence on the results.

Summary synthesis: The diagnostic tests conducted yield several important insights into the extent to which the classical assumptions of linear regression are satisfied. The White test indicates no statistical evidence of heteroskedasticity (), suggesting that the variance of residuals is generally stable across fitted values. However, the Shapiro–Wilk test rejects the null hypothesis of normality (, ), suggesting significant deviations from a normal distribution of residuals. The Durbin–Watson test further shows substantial positive autocorrelation (, ), indicating dependence among residuals over time. The assessment of multicollinearity via the VIF test shows that all values fall below the conventional threshold of 10, suggesting that severe multicollinearity is not present. Nonetheless, moderate collinearity exists, namely for the variables SHF and GDP, which need attention in the interpretation of coefficient estimates. The analysis of outliers and influential observations reveals a number of data points with extreme studentized residuals, high leverage, and elevated Cook’s distances. While such cases are common in firm-level panel data involving heterogeneous entities and complex operational, macroeconomic, and tax and legal environments, they can exert a disproportionate influence on the estimate. Despite this, the overall integrity of the estimate results is not compromised. This is due to the asymptotic properties of the estimate: in sufficiently large samples, the estimate remains both consistent and asymptotically normal, even when some classical OLS assumptions, such as strict normality, are not fully met.

In addition to the asymptotic properties of the estimate, in general the non-normality observed in financial data can also be understood as an inherent feature of arbitraged and competitive markets. In well-arbitraged financial markets, asset prices, firm-level performance indicators, and related financial variables tend to reflect the aggregation of heterogeneous information, rapid adjustments to news, and strategic responses by market participants. This process generates return distributions with skewness and volatility clustering, all of which deviate from the Gaussian assumption without necessarily implying model misspecification (

Cont, 2001;

Fama, 1970). These empirical regularities, often referred to as “stylized facts” of financial time series, are well documented and stem from discontinuous price jumps, asymmetric information, and occasional systemic shocks (

Campbell et al., 1997;

Mandelbrot, 1963). From an econometric perspective, these distributional characteristics do not inherently bias coefficient estimates, provided the other Gauss–Markov assumptions (linearity in parameters, exogeneity, and no perfect multicollinearity) are met. Instead, they primarily affect inference, narrowing or widening the accuracy of standard errors, an issue that can be effectively addressed through robust covariance estimators (e.g., White’s heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors). Therefore, in the context of financial data generated under arbitrage conditions, non-normality of residuals is not an anomaly but an expected property of the data generating process. Hence, the core empirical findings remain valid, supported by methodological rigor and the robustness of the estimation approach, despite deviations from strict normality. The empirical results are further validated by robustness checks, which are presented in the following subsection.

7.4. Robustness Tests

By applying robustness tests, the aim is to ensure that the empirical results are not artifacts of misspecified residual assumptions or sensitivity to specific data points. We apply robust standard errors (White’s HC0 Estimator) and the Box–Cox transformation. This is especially prudent given the non-normality and the outliers identified. The outcomes of the robustness test are presented in the following.

Robust Standard Errors:

Table 4 presents the standard robustness (HC0) test.

The application of White’s heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors (HC0) provides a robustness check on the significance of the estimated coefficients with the POLS regression model. All variables remain statistically significant at the level (), which indicates robustness of the empirical findings.

Box–Cox transformation: The Box–Cox transformation was applied to the dependent variable EBIT in order to address the non-normality of residuals. The transformed variable is defined as follows:

This transformation yields and was chosen based on standard Box–Cox diagnostic procedures. Following transformation, the estimate results remain robust: all coefficients retain statistical significance, and the adjusted of still indicates a very good fit. Diagnostic tests confirm improvements in residual behaviour. The Breusch–Pagan test fails to reject the null hypothesis (, , p-value ), suggesting variance stability across fitted values. The Durbin–Watson test (, ) indicates a reduction in positive autocorrelation relative to the initial estimate. Despite the improvements in variance properties, normality remains a limitation, as shown by the Shapiro–Wilk test (, ).

Despite non-normality, the combination of robust standard errors and the Box–Cox transformation strengthens the asymptotic validity of the inference in the estimate of the POLS regression model. Consequently, the estimate achieves both improved robustness and reliable statistical inference in a large-sample context.

The next section turns to discuss the empirical findings in connection to this study’s theoretical expectations in the broader context of the existing literature.

8. Results Discussion

First, our findings provide robust evidence for Hypothesis 1, which predicts that an increase in the corporate income tax differential is associated with a decrease in the reported EBIT of MNC-controlled subsidiaries operating in Morocco. This finding accords with prior studies showing that larger corporate income tax differentials encourage multinational firms to shift profits across jurisdictions. In other words, when Morocco becomes less attractive from a tax perspective, either due to an increase in its CIT rate or a reduction in the CIT rate of the subsidiary’s parent country, and following our theory model, MNCs appear to optimally adjust the transfer price to shift subsidiaries’ taxable income toward low-tax jurisdictions. In the same vein, the descriptive statistics show a significant tax arbitrage potential in Morocco. The values of the corporate income tax differential indicate that, over the sample period, Morocco’s CIT rate tends to exceed that of MNCs’ parent jurisdictions. This observation is consistent with the theoretical incentive for profit-shifting. The observed range of the CIT differential, from −17.92% to 32%, also reflects considerable heterogeneity in the fiscal environment, further reinforcing the importance of CIT differential-based incentives in MNCs’ profit allocation strategies. Our findings highlight both the vulnerability of Morocco to tax base erosion, despite BEPS implementation in 2019, and the urgent need for strengthening enforcement of transfer pricing regulations that may help curtail profit-shifting and enhance fiscal revenues. Overall, the results of our study speak to the broader debate underscoring developing countries’ concerns that they suffer by seeing their tax base eroded. In fact, as recognized by the OECD, the current global tax framework is shaped more by tax competition than by cooperative policy alignment (

Janský & Prats, 2015). This competitive dynamic places significant pressure on national tax authorities, particularly in developing countries. Evidence increasingly suggests that tax competition generates negative fiscal externalities, so-called spillover effects, which are more pronounced in developing economies (

de Mooij et al., 2021). Naturally, cross-country fiscal spillovers have the potential to intensify tax competition among national governments. In the absence of effective international coordination, this dynamic can encourage jurisdictions to adopt overly lenient transfer pricing regulations, thereby exacerbating profit-shifting incentives and undermining collective tax enforcement efforts (

de Mooij and Liu (

2020); see also

Lohse and Riedel (

2013) and

Marques and Pinho (

2016)).

Second, this paper’s results show that institutional quality plays a crucial role in shaping subsidiaries’ reported profitability. Both the rule of law and regulatory quality have a positive effect, respectively, ∼EUR 577,000 and ∼EUR 1.08 million, on subsidiaries’ EBIT. This indicates that a more transparent, predictable, and well-enforced legal and regulatory environment in Morocco supports operational performance. These results confirm Hypothesis 3, suggesting that beyond tax incentives, institutional factors significantly impact MNC subsidiaries’ profitability in Morocco. This likely reflects a more predictable fiscal environment, with simple and clear tax laws and regulations based on objective criteria, leaving less room for inconsistency and tax loopholes, reducing tax uncertainty, and providing conditions more favourable to investment and firm performance.

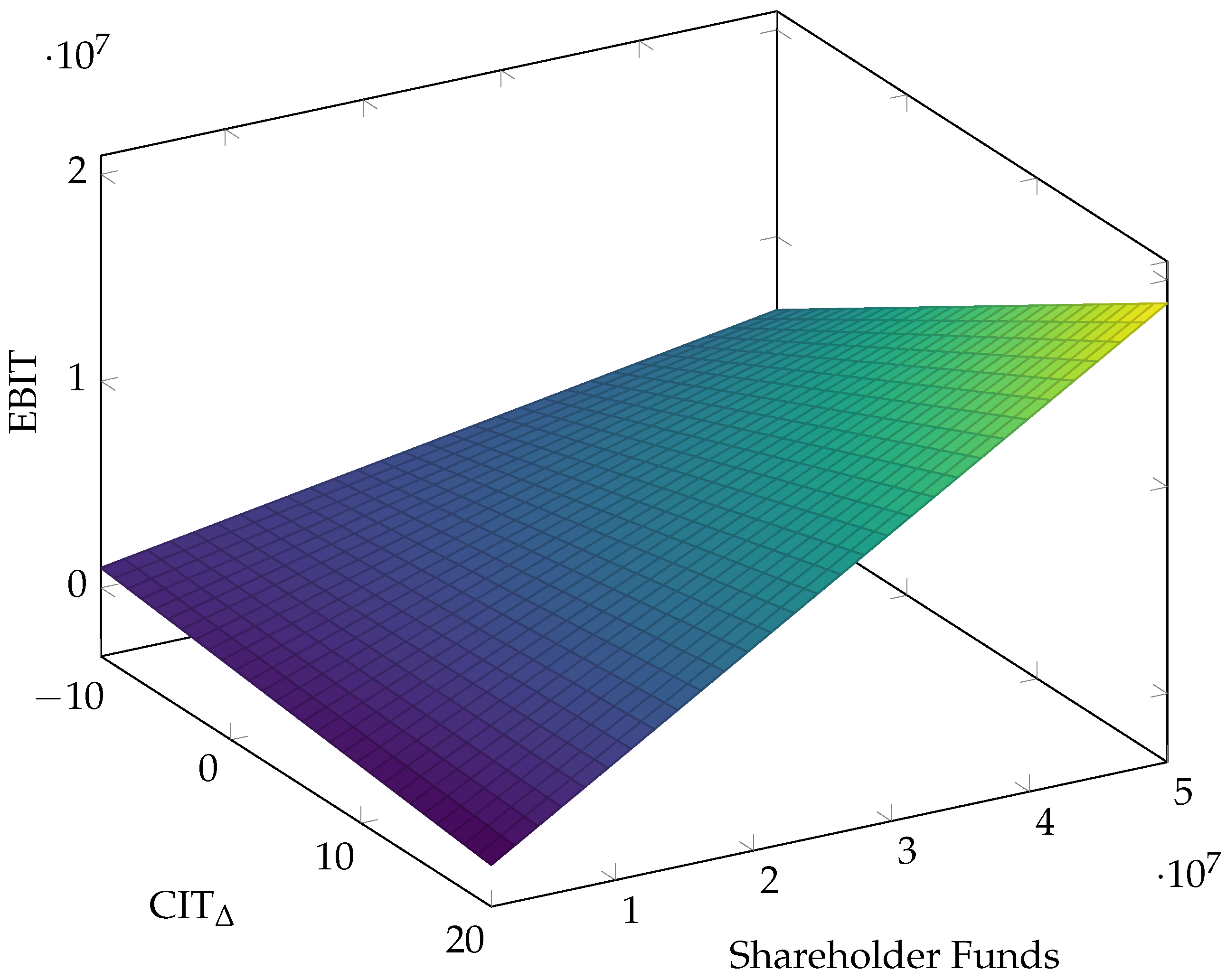

Third, the interaction term between the CIT differential and shareholder’ funds is positive and statistically significant. We plot a 3D surface to visualize the moderation effect. The plot (

Figure 3) illustrates how the effect of

on

varies depending on the level of shareholder’ funds (SHFs). The surface represents the response values on the

z axis EBIT. The interaction term is expressed as follows:

Figure 3 illustrates the marginal effects of CIT differentials across different levels of shareholders’ funds. The slope becomes flatter as capitalization increases, indicating that financially stronger subsidiaries are better able to mitigate the impact of fiscal asymmetries. The interaction effect suggests that better-capitalized firms adjust EBIT more closely to

. E.g., if Morocco’s CIT tax is 2% higher than that of the subsidiary’s parent country (

= +2), an MNC-controlled subsidiary with 150,000 million in shareholder’ funds might see a substantial EBIT decrease of

136,000, with minimal offset from the interaction term due to low SHF. However, a larger firm with

million in shareholder’ funds exhibits a 988,604 EBIT. As shareholder’ funds increase, the negative effect of a higher

on EBIT becomes smaller or may even reverse direction. Those subsidiaries seem to be better capitalized to absorb the higher cost of capital and exhibit an increase in reported EBIT.

This result contradicts the prediction of Hypothesis 2. Contrary to expectations based on investment distortion theory, these MNC subsidiaries do not reduce investment in response to a higher cost of capital. Instead, they appear to offset such fiscal asymmetries. This likely occurs because marginal capital productivity increases sufficiently to compensate the higher cost, possibly also through more advanced tax planning. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is not empirically supported.

These findings also suggest that CIT differentials encourage MNCs not only to engage in profit-shifting activities but also to allocate greater capital to their well-capitalized controlled subsidiaries. In this regard,

Bilicka et al. (

2024) find that larger and more capable subsidiaries, proxied by organizational capacity and firm size, are more effective at shifting profits to low-tax jurisdictions. Supported by the literature, we argue that MNC-controlled subsidiaries with more capital (higher shareholder funds) exhibit stronger fiscal responsiveness, meaning they mitigate the negative impact of tax differentials by engaging in more sophisticated profit-shifting strategies. Furthermore,

Serena (

2013) provides empirical evidence that variations in asset taxation induce systematic distortions in firms’ capital allocation, characterized by under-investment in less tax-favoured assets and over-investment in tax-preferred ones. In this context, our results emphasize the pivotal role of capitalization in supporting profit-shifting strategies via transfer pricing channels. It underscores the importance of shareholders’ funds not only as a determinant of financial capacity but also as an enabling element of tax-motivated profit allocation, highlighting more targeted regulatory oversight of MNCs with substantial equity bases. In Morocco’s context, characterized by extensive free trade agreements, diversified investment partnerships, and evolving BEPS-based anti-avoidance frameworks, the government needs to balance the complex trade-off when setting corporate tax policy, namely protecting taxable income and maintaining investment attractiveness, while simultaneously ensuring robust anti-avoidance measures, such as BEPS rules and transfer pricing regulations. Is the corporate income tax rate low enough to remain competitive and keep MNCs operating locally, high enough to generate revenue and prevent excessive profit-shifting, and supported by strong institutional quality to reduce compliance costs and enforce regulations effectively? A body of literature suggests that to optimize this trade-off, countries benefit from combining moderate CIT rates with robust anti-avoidance measures such as BEPS rules and transfer pricing regulations policies. In this context,

Bilicka et al. (

2024) model the government’s objective to combat profit-shifting while encouraging corporate investment. The paper formulates an optimization framework where the state chooses tax parameters to maximize welfare under revenue and economic growth constraints. The authors quantify the trade-off between combating tax avoidance and increasing the cost of capital for MNEs that engage in tax avoidance. Furthermore, the study shows that tightening anti-avoidance rules (e.g., BEPS) and strategically setting CIT rates involves a complex balance, raising revenue integrity without deterring investment. Future work could further analyse these topics in Morocco’s context.

The results carry several important policy implications. First, the significant responsiveness of reported profits to CIT differentials suggests the need for Morocco to refine transfer pricing regulations and enhance audit capabilities, particularly for large capitalized subsidiaries that appear more capable of tax optimization. Second, BEPS implementation should be accompanied by simplified compliance procedures to reduce administrative burdens while maintaining enforcement strength. Third, promoting institutional quality, through improved regulatory transparency and legal enforcement, can indirectly enhance tax compliance and subsidiary profitability. Despite these implications, this study has several limitations. The analysis focuses on non-financial profit-shifting and does not fully capture debt-based tax avoidance channels. Our study puts the main emphasis on mispricing of intra-firm sales as a primary channel of profit-shifting activities. If this assumption is relaxed, profit measures including financial profit and losses, most notably interest deductions, are likely to be more responsive to tax rates changes, indicating that profit-shifting is also significantly undertaken through debt shifting (

Loretz & Mokkas, 2015). However, although debt shifting may affect investment behaviour, it does not alter the general conclusions of our analysis. Additionally, unobserved firm heterogeneity may still bias results to some extent. Future research should extend the analysis to include hybrid mismatches and multinational network effects and explore dynamic adjustments in developing economies’ tax regimes.

9. Conclusions

In this paper, we use a pseudo-ordinary least squares (POLS) framework to examine the responsiveness of profit to the corporate income tax differential by MNCs operating in Morocco, thereby providing empirical evidence of corporate profit-shifting behaviour. We focus on MNCs operating in Morocco due to the underexplored context of profit-shifting practice and the presence of significant tax arbitrage potential. To the best of our knowledge, our paper is the first to empirically investigate the nexus between the CIT differential and MNCs’ profit-shifting behaviour in Morocco.

We develop our conceptual framework and formulate our hypotheses. Our theoretical model of a representative MNC demonstrates that the incentive to engage in mispricing of intra-firm sales is exclusively driven by the CIT differential. Furthermore, supported by the standard investment theory, we argue that the impact of the CIT differential on profit is moderated by MNC capital investment, proxied by shareholders’ funds. However, elevated tax burdens increase the marginal cost of capital, thereby constraining MNCs’ investment in their controlled subsidiaries. Finally, we support the hypothesis that macroeconomic factors and institutional quality indicators in Morocco positively influence subsidiaries’ profitability.

Our empirical analysis is based on micro-level data. We construct a panel dataset of foreign-owned subsidiaries operating in Morocco in the period between 2014 and 2023. The dataset comprises 2440 observations. We express an estimate using the POLS regression model to assess the effect of the CIT differential on subsidiaries’ earning before interest and taxes (EBIT). The model includes an interaction term to capture the moderating role of internal capital investment, proxied by shareholders’ funds. In addition, the estimate incorporates the key explanatory variables GDP, the OECD’s base erosion and profit-shifting (BEPS) implementation, the effect of the COVID-19 crisis, and institutional quality indicators (regulatory quality and rule of law), providing broader contextual dynamics that may affect reported EBIT independently of tax incentives.

Our findings indicate that the CIT differential significantly negatively correlates with subsidiaries’ EBIT. The estimate suggests that, on average, a one-percentage-point increase in the CIT differential is associated with a EUR 85,448 decline in reported subsidiaries’ EBIT. Our results further reveal that the effect of the CIT differential on EBIT increases significantly with shareholders’ funds. Yet, in contrast to investment distortion theory, subsidiaries do not appear to curtail investment when facing higher effective capital costs. Rather, they seem capable of mitigating these fiscal asymmetries, likely through enhanced marginal capital productivity and the use of more advanced tax planning practices. This interpretation is consistent with the literature suggesting that CIT differential not only incentivize MNCs to engage in profit-shift, but also encourages greater capital allocation toward well-capitalized subsidiaries. Our finding emphasize the strategic role of capitalization in facilitating profit-shifting through transfer pricing mechanisms. They further underscore the importance of shareholders’ funds not only as a determinant of financial capacity but also as an enabling factor in tax-motivated profit allocation, thereby calling for more targeted regulatory oversight of MNCs with substantial equity bases. Moreover, the empirical findings presented in this study reveal that the implementation of BEPS in Morocco led to a EUR 8.2 million decrease and the COVID-19 crisis caused a EUR 5.8 million decrease in subsidiaries’ reported profits. Institutional quality indicators, rule of law and regulatory quality, positively impact subsidiaries’ EBIT, suggesting that stronger legal frameworks and regulatory environments enhance operational performance. Our results remain robust across multiple diagnostic tests that are validated by robustness checks.

Our findings are consistent with the empirical profit-shifting literature. The estimated negative relationship between CIT differentials and reported profits aligns with results obtained by

Heckemeyer and Overesch (

2017) and

Beer et al. (

2020). However, the magnitude of the estimated effect observed in Morocco is larger than the benchmark estimates reported by

Heckemeyer and Overesch (

2017). For a median-sized subsidiary, this effect represents about 2.4% of annual earnings, exceeding the consensus semi-elasticity of 0.54% for EBIT documented in their meta-analysis. This discrepancy may reflect context-specific factors, including variations in enforcement intensity, institutional capacity, data composition, or the scale of firms’ operations, all of which can influence the observed responsiveness of profits to CIT differentials. In contrast to

Janský and Miroslav (

2019), who emphasize the limited responsiveness of African subsidiaries to tax incentives, our results indicate that capitalization significantly moderates profit-shifting, suggesting that better-capitalized subsidiaries are more active in exploiting CIT differentials. These differences underline the importance of firm-level heterogeneity and country-specific regulatory environments in shaping the extent of profit-shifting.

Overall, we acknowledge that our approach and analysis are only a step toward a deep understanding of the complex link between international tax competition, corporate investment, and anti-avoidance measures (e.g., BEPS) in the context of developing countries. Thus, this study’s results contribute to the ongoing debate on profit-shifting in these economies and highlight the specific challenges faced by Morocco. Our findings provide important policy implications. However, addressing these issues requires a balanced policy framework that combines moderate tax rates, robust enforcement of anti-avoidance measures, and institutional quality. Clearly, more research is needed to analyse the optimization framework underlying tax policy, in particular by the strategic setting of CIT rates. Future work should address how to balance the complex trade-off between protecting revenue integrity and maintaining investment attractiveness, while simultaneously ensuring robust anti-avoidance measures, such as BEPS rules and transfer pricing regulations. Moreover, this study has not considered the potential welfare effects of transfer pricing practices and anti-avoidance regulations. These issues are left for further research.