Abstract

The digital economy creates new opportunities for micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in Indonesia to enhance their competitiveness through the adoption of financial technology. This study examines how digital financial inclusion (DFI) mediates the effects of digital financial literacy (DFL) and government support (GS) on MSME performance. This mediating relationship remains underexplored in developing countries, offering new insights into how it drives business advancement. A quantitative approach was applied using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) based on survey data from 260 culinary MSME owners. The results indicate that knowledge-based resources and institutional support positively influence performance through DFI. DFI drives improvement by expanding market reach, increasing operational efficiency, facilitating transactions, optimizing the value of financial activities, and broadening access to financing. These findings underline the importance of policies that promote inclusive digital ecosystems and strengthen digital capability. Future research approaches should emphasize the integration of behavioral factors, institutional support, and business performance within the evolving MSME ecosystem and can be further developed through longitudinal or cross-sectoral studies to understand the sustainable dynamics of digital transformation.

1. Introduction

Micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) are pivotal drivers of inclusive economic growth, particularly in developing nations. These enterprises are instrumental in job creation and economic advancement, and serve as essential catalysts for sustainable development (Anthanasius Fomum & Opperman, 2023; Amoah et al., 2022). In Indonesia, MSMEs contribute to approximately 60% of the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employ nearly 97% of the workforce. Strengthening MSMEs through formalization and access to financial services aligns with the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Yang & Zhang, 2020). The performance of MSMEs in developing nations has attracted growing interest from researchers, policymakers, and the public owing to their crucial contribution to economic growth (Zulu-Chisanga et al., 2020). Despite its substantial contributions, MSMEs face persistent challenges such as limited digital adoption and inadequate financial literacy, which constrain their competitiveness and sustainability (Msomi & Kandolo, 2023).

To address these challenges, the Indonesian government launched the MSME “Level Up” program (Limanseto, 2022), focusing on digital training, financing, and mentoring to accelerate MSMEs’ integration into digital and global markets. The initiative reflects the government’s commitment to promoting digital transformation, which is expected to significantly strengthen their competitiveness and contribute to Indonesia’s digital economy projected to reach USD 146 billion by 2025. Digitalization improves business efficiency and productivity (Rachinger et al., 2019), thereby fostering the growth of the digital economy (OECD/EBRD, 2023). During the G20 Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion High-Level Symposium, the Minister of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia emphasized the critical role of digitalization in financial inclusion. Digitalization is a vital component of MSMEs in Indonesia to achieve their objectives, including access to financing, payments, bookkeeping, and digital marketing.

Through the National Council for Financial Inclusion, the Indonesian government is committed to increasing financial inclusion by continuously encouraging all government institutions to actively promote and enforce initiatives aimed at expanding access to financial services and increasing bank account ownership. This support has been intensively implemented through various financial education and literacy initiatives targeting priority groups, including MSMEs. Financial inclusion enhances access to financial resources for marginalized groups, enabling investment in education, healthcare, and small business development (Meniago, 2025). Along with technological advancements, the accessibility of financial services has shifted towards digitalization by leveraging technology (Widyastuti et al., 2024).

Digital financial inclusion (DFI) plays a crucial role in empowering MSMEs by providing access to financial services that were previously difficult to obtain (Johri et al., 2024). Empirical studies have consistently shown that DFI significantly impacts performance. Thathsarani and Jianguo (2022) demonstrated a positive relationship between financial inclusion and performance, mediated by digital finance within the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Frimpong et al. (2022) found that access to digital financial services (DFS) enhances business efficiency and market reach, while Febriansyah et al. (2024) emphasized that inclusive access to fast, reliable, and secure financial services is critical for improving MSME performance in Indonesia. Peter et al. (2025a) confirmed that financial inclusion mediates the relationship between digital financial literacy (DFL) and financial performance, emphasizing its essential role in enhancing business outcomes through improved access to financial services.

While several studies have primarily examined the immediate relationship between DFI and performance, research exploring its mediating role in the MSME remains relatively scarce and fragmented. Achieving effective DFI requires more than the availability of services, and also depends on adequate digital knowledge among users to ensure secure usage, informed decision-making, and optimal platform utilization. In addition, government support (GS) play a crucial role in supporting DFI by providing reliable infrastructure, accessible digital financing, secure payment systems, and supportive regulatory frameworks. These elements foster trust, bridge the digital divide and promote equitable access to financial opportunities. Building on these insights, this study highlights the relationship between DFL and GS through the lens of DFI, a context that remains underexplored in the literature, particularly regarding its implications for sustainable MSME performance.

DFL refers to the ability to use digital tools such as online banking, e-wallets, and investments to manage finances securely and effectively (Lyons & Kass-Hanna, 2021). DFL equips individuals with financial technology knowledge and enhances their awareness, enabling them to access and use DFS safely and effectively (Choung et al., 2023). Fintech innovation and digital infrastructure contribute to narrowing the financial divide. However, their effectiveness depends on adequate literacy levels (Ferilli et al., 2024). DFL is shaped by demographic and behavioral determinants, creating disparities that can limit the benefits of digital finance (Lal et al., 2025). This suggests that unequal levels of digital literacy can perpetuate disparities in financial inclusion, underscoring that DFI outcomes are deeply contingent on underlying inequalities in DFL across demographic and socioeconomic groups.

GS is essential for the sustainability of MSME operations, contingent on the alignment of support types with MSME needs (Najib et al., 2021). Governments across various nations now provide financial assistance to SMEs as well as non-monetary support, including business consulting services, training, and management mentoring. These programs, referred to as business diagnostics and support services, involve expert teams that conduct comprehensive evaluations of SMEs’ conditions and offer strategic recommendations to enhance their competitiveness and business success, thereby promoting their economic development (Park et al., 2019). Amid efforts to strengthen the MSME sector, the Indonesian government actively promoted DFL through technology-based inclusion and educational policy. Digital adoption positively and significantly impacts financial literacy, indicating that increased digital adoption among MSMEs corresponds to increased financial knowledge (Affandi et al., 2024). The government needs to actively encourage business actors to gain access to financial services at lower costs and through easier methods to improve financial inclusion (Yang & Zhang, 2020). Thus, the government plays an important role in strengthening DFI as a strategic instrument to accelerate the development and sustainability of these businesses.

Prior research has demonstrated that DFL, GS, and DFI are pivotal to MSME performance. However, limited attention has been paid to how these factors interact as complementary resources that jointly strengthen MSMEs’ competitive advantage and performance outcomes. This study draws on the Resource-Based View (RBV), which posits that a firm’s ability to manage and integrate internal and external resources determines its sustained competitive advantage. Within this framework, DFL and GS are viewed as enabling resources that can enhance MSME performance through the effective utilization of DFI as a strategic capability. This study offers a distinct contribution by adopting an integrative perspective that positions DFI as a bridging mechanism linking DFL and GS to MSME performance, an interaction that has received limited empirical attention in prior research. By addressing this gap, this study advances the application of the RBV framework in the digital finance context and provides policy-relevant insights for enhancing MSME competitiveness and sustainability in emerging economies.

The main objectives of this study are to examine the effects of DFL and GS on MSME performance in Indonesia and to assess whether DFI mediates these relationships. DFI is a critical factor bridging the digital transformation of MSMEs for sustainable performance enhancement. This engagement has the potential to fortify MSME resources, broaden market reach, and enhance operational efficiency, thereby contributing to improved performance. Consequently, the success of DFL initiatives and GS is contingent on the efficacy of DFI in driving MSME performance. This study contributes to the MSME performance literature.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 1 introduces this study, and Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review and formulates the research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the research methodology. Section 4 reports the findings, and Section 5 discusses the results. Section 6 provides conclusions and practical implications, Section 7 outlines the study’s limitations and suggests directions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Resource-Based View Theory

RBV emphasizes that companies achieve and sustain competitive advantage by managing and utilizing internal and external resources as strategic assets (Wernerfelt, 1984; Barney, 1991). These resources include physical assets, human capital, technology, and organizational processes that provide firms with a relative advantage over competitors. RBV asserts that firms will perform better when they effectively leverage resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN). The theory seeks to explain how resources and strategic assets contribute to long-term profitability and performance by creating a sustained competitive edge.

DFL is conceptualized as a valuable and inimitable human capital resource that enhances entrepreneurs’ ability to understand and utilize DFS effectively (Hossain et al., 2020; Dura, 2022; Frimpong et al., 2022). GS is viewed as a rare and non-substitutable institutional resource, derived from public policies, regulations, and infrastructure that cannot be easily replicated by competitors. Furthermore, DFI can be interpreted as an organizational capability that transforms these resources into tangible performance outcomes. DFI operationalizes the dynamic linkage between resources and performance, consistent with the RBV’s premise that competitive advantage emerges from how firms strategically deploy and integrate their resources (David-West et al., 2018; Peter et al., 2025b).

In parallel, behavioral theories such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) have also been employed to explain digital financial adoption from a psychological perspective. TPB posits that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control influence individuals’ intentions to adopt new technologies. Empirical studies further highlight that behavioral factors such as risk attitude, future orientation, and behavioral intention significantly shape DFL and adoption (Lal et al., 2025). Thus, while TPB provides insights into the psychological and behavioral mechanisms driving adoption, RBV focuses on the strategic utilization of resources that enable sustained performance and outcomes. This study therefore employs RBV as the grand theoretical framework, positioning DFI as strategic resources that jointly enhance MSME competitiveness, while acknowledging behavioral perspectives such as TPB as complementary explanatory lenses.

2.2. MSME Performance

Digitalization entails incorporating digital technologies into various processes along the value chain, which boosts value for customers and other stakeholders and ultimately improves organizational performance (Mavlutova et al., 2022). The performance of MSMEs is demonstrated by their achievements in different areas, particularly financial ones, such as increased revenue, profitability, assets, and investments (Eller et al., 2020) and is significantly influenced by business actors’ abilities to effectively utilize resources, including human resources, capital, and technology. Numerous studies have demonstrated that business performance is contingent on access to finance (Frimpong et al., 2022; Thathsarani & Jianguo, 2022; Febriansyah et al., 2024). Research indicates that DFI enhances access to and availability of financial technology, supports entrepreneurial ventures, and helps overcome obstacles encountered in business. By offering access to DFS and solutions, these organizations may mitigate different challenges and improve their financial stability and growth (Johri et al., 2024).

2.3. Digital Financial Literacy

DFL is a multifaceted concept (Morgan et al., 2019). DFL integrates two pivotal concepts namely digital literacy and financial literacy. This can be described as financial literacy within the realm of digital technology. As an emerging field, DFL emphasizes the critical knowledge and competencies necessary to perform financial transactions on digital platforms (Choung et al., 2023). DFL is interconnected with a broader system that encompasses digital infrastructure, regulatory policies, and DFS (Manoj et al., 2024). The synergy of these elements can aid MSMEs in shifting from conventional practices to more innovative and scalable business models. Communities exhibiting elevated levels of financial literacy are more inclined to actively engage with and access the financial system (Widyastuti et al., 2024). Among female entrepreneurs, DFL can enhance the utilization of financial services, particularly in facilitating banking transactions (Hasan et al., 2022). MSMEs must acquire the requisite knowledge and skills to fully leverage the transformative potential of DFI.

2.4. Government Support

The government is crucial for promoting DFI by establishing supportive policies and infrastructure. This may involve the development of a robust digital payment ecosystem or the provision of incentives for financial institutions to cater to micro-enterprises (Johri et al., 2024). Governmental incentives for digital financial initiatives can empower movements that utilize readily available technology, thereby accelerating inclusion (Daud & Ahmad, 2022). Government involvement is essential for formulating effective policies and ensuring their efficient implementation, thereby providing equitable opportunities for MSMEs to gain competitive market advantages (Ganlin et al., 2021). Additionally, the government can make financial services more accessible and affordable for small and micro-enterprises, thereby enhancing the impact of DFI on their growth (Yang & Zhang, 2020). The government aim to improve the financial inclusion index by designing regulations that expand financial access through policies aimed at increasing financial inclusion, particularly for those in the lowest income groups (Widyastuti et al., 2024).

2.5. Digital Financial Inclusion

The transformation of DFI holds tremendous potential to facilitate the provision of efficient, affordable, convenient, and easily accessible financial products and services for small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as individuals with limited income (Xi & Wang, 2023). Digital finance has emerged as a pivotal instrument for mitigating social disparities and fostering economic growth (Liu et al., 2021). This represents an innovative financial model that integrates financial activities with cutting-edge technologies (Mavlutova et al., 2022). By leveraging digital technology, DFI enhances access to formal financial services (Naumenkova et al., 2019). This includes digital interactions between financial institutions and consumers, as well as the necessary infrastructure to support digital financial products. DFI has a positive effect on the 42 member countries of the One Belt and Road Initiative, including Indonesia (Ozturk & Ullah, 2022). Developing nations, particularly those in Asia, actively promote DFI to alleviate poverty (Tay et al., 2022). This underscores the importance of comprehending the advantages of DFS and implementing policies that enhance their accessibility of financial services.

2.6. Relationship Between Digital Financial Literacy and MSME Performance

DFL refers to the ability to use digital tools and platforms to make informed financial choices and effectively manage personal finances in the digital space (Abdallah et al., 2025). Managers must enhance their DFL competencies to improve the financial performance of MSMEs (Kusumawardhani et al., 2023). Prior studies demonstrate that financial literacy and the adoption of fintech improve MSME performance through enhanced access to finance, innovation, and operational efficiency (Kurniasari et al., 2023; Frimpong et al., 2022; Dura, 2022; Hossain et al., 2020). The ability of MSMEs to comprehend and employ financial technology facilitates efficient financial management and fosters innovation and business development. DFL plays a crucial role in enabling MSMEs to effectively leverage digital financial ecosystems, optimize operational processes, and sustain competitiveness. Strengthening DFL therefore represents not merely a cognitive enhancement, but a strategic effort to improve organizational performance and sustainability. Based on this analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 1.

Digital financial literacy has a positive impact on MSME performance.

2.7. Relationship Between Government Support and MSME Performance

GS plays a pivotal role in enhancing MSME performance by providing direct assistance such as financing and training and by indirectly fostering a supportive business environment that promotes innovation and competitiveness. Policymakers are urged to formulate policies that enhance financial inclusion and the advancement of DFS within their nations, thereby enhancing their performance (Frimpong et al., 2022). Prior studies demonstrate that GS enhances MSME performance by improving financial access, managerial capability, and technological adoption (Trieu et al., 2025; Zainuri et al., 2025; Gao et al., 2022; Park et al., 2019). However, empirical evidence remains inconclusive. Zulu-Chisanga et al. (2020) found that policy and financial support were not effectively translated into improved performance, while Hossain et al. (2020) reported that GS did not strengthen the link between financial literacy and SME growth. These mixed results indicate that the effectiveness of GS may depend on contextual and implementation factors, particularly in emerging digital economies. Moreover, the integration of financial, social, and institutional resources highlights the government’s essential role in enabling MSMEs to access and utilize resources that drive performance. Based on this analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 2.

Government support has a positive impact on MSME performance.

2.8. Mediating Effect of Digital Financial Inclusion on Digital Financial Literacy and MSME Performance

Improving DFL is crucial for boosting the comprehension of digital financial products and services among MSMEs. Greater financial literacy can lead to better financial inclusion and heightened consumer interest in financial products (Khan et al., 2022). The insufficiency of financial resources during business operations is a predominant factor contributing to SMEs’ global failure. The rise in mobile financial services has made it easier for customers to engage in convenient financial activities such as transferring money between individuals, paying bills for online purchases, and accessing other financial services (Shaikh et al., 2023). Digital finance, which encompasses Internet finance and FinTech, is instrumental in transforming financial services (Xia et al., 2022).

Recent empirical evidence from Peter et al. (2025a) confirms that DFI mediates the relationship between DFL and the performance of women entrepreneurs in India, suggesting that inclusion serves as a pathway linking literacy and business outcomes. This mechanism remains underexplored in emerging digital economies, particularly among MSMEs in Indonesia, where digital financial ecosystems are rapidly evolving. It introduces DFI as a strategic mechanism that converts digital financial literacy into measurable performance improvements, providing new insights into MSME competitiveness. Based on this analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 3.

Digital financial inclusion mediates the relationship between digital financial literacy and MSME performance.

2.9. Mediating Effect of Digital Financial Inclusion on Government Support and MSME Performance

DFI offers a viable solution for Indonesian MSMEs to easily engage with financial institutions, thereby enabling them to secure the capital, financial products, and services essential for their operations and enhancing their financial performance (Mutamimah & Indriastuti, 2023). DFI serves as a critical conduit that link GS with enhanced performance. The government can significantly contribute to promoting DFI by implementing supportive policies and infrastructure. This may involve establishing a robust digital payment ecosystem or incentivizing financial institutions to cater to microenterprises (Johri et al., 2024).

The mediating role of DFI in the relationship between GS and MSME performance remains insufficiently examined, especially within emerging digital economies such as Indonesia. Previous studies have mainly focused on the direct effects of government support on firm outcomes, overlooking how inclusion channels these effects into measurable performance improvements. DFI is regarded as a mechanism to diminish barriers to financial access, potentially increasing innovation capacity, and fostering economic growth. Governments can facilitate micro-enterprises’ access to financial services at reduced costs and with greater ease, thereby enhancing the role of DFI in driving their development (Yang & Zhang, 2020). Consequently, DFI can mediate the relationship between GS and MSME performance. Based on this analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 4.

Digital financial inclusion mediates the relationship between government support and MSME performance.

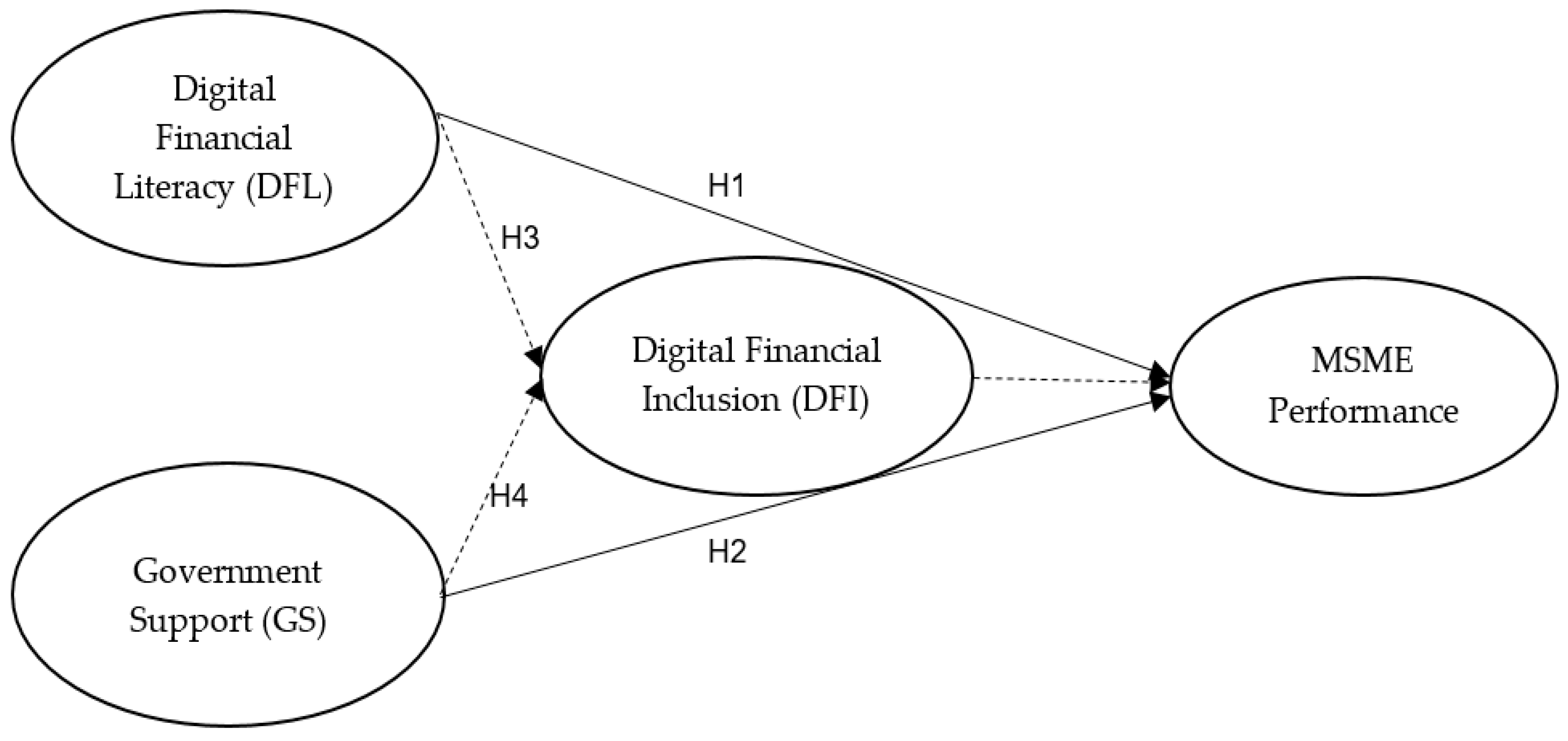

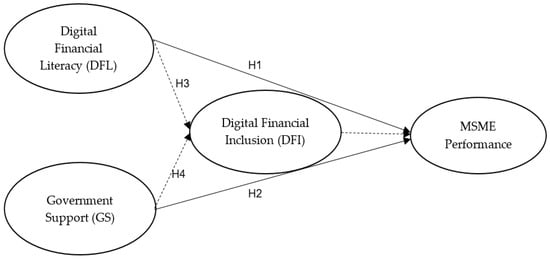

Drawing on the literature review and previously formulated hypotheses, this study introduces the conceptual framework depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study employed a quantitative methodology to examine the relationship between DFL, GS, DFI, and MSME performance. The selection of quantitative methods facilitates the statistical testing of hypothesized relationships and enables the generalization of findings from the sample to a broader MSME population. Data analysis was performed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS 4. The selection of PLS-SEM was informed by several methodological considerations. First, the research model is intricate and encompasses mediation relationships that depict causal connections between latent constructs. PLS-SEM is a suitable method for analyzing complex cause–effect relationship models, particularly in exploratory research (Hair et al., 2021). Second, PLS-SEM is proficient in explaining the variance of endogenous constructs and demonstrates strong predictive capabilities, especially with small to medium sample sizes and when the data do not adhere to a normal distribution. Third, this approach is oriented towards prediction and theory development rather than merely achieving model fit (Sarstedt et al., 2020b). Consequently, PLS-SEM is deemed most appropriate for thoroughly examining the relationships between DFL, GS, DFI, and MSME performance.

3.2. Sampling Method

A purposive sampling method was used to ensure the recruitment of participants who conformed to the specified research criteria. This method was chosen because it allows researchers to deliberately recruit participants who possess characteristics that are directly relevant to the research objectives, thereby increasing the accuracy and contextual relevance of the obtained data (Hair et al., 2021). The study population comprised 505 MSMEs in the culinary industry, all of which were supervised by the Incubator Team of the Cooperative and Small and Medium Enterprises Agency in Makassar City, Indonesia (Sirkhairulumam, 2025). The culinary sector was chosen for its significant consumer demand, sustainable market potential, and rapid adoption of DFS, making it an appropriate context for examining the impact of digital finance on business performance.

To reduce sampling bias, strict inclusion criteria required that respondents be owners or managers of MSMEs who had used at least one digital financial service, such as mobile banking, e-wallets, or online payment systems. Data collection was conducted online to ensure accessibility and equal participation opportunities. Although purposive sampling may limit external validity due to its non-random nature, this approach enhances representativeness by focusing on respondents with direct and relevant experience. Thus, while the findings may not be fully generalizable to all MSMEs, they provide contextually meaningful insights into the digital financial practices of culinary enterprises in Makassar. Based on these criteria, 260 valid responses were obtained, representing approximately 52% of the total population, ensuring methodological rigor and contextual reliability.

3.3. Data Collection

The data collection process was conducted online to enhance accessibility and was disseminated through announcement messages in digital platform groups specifically formed for MSMEs under the supervision of the Incubator Supervision Team at the Cooperative and Small and Medium Enterprises Agency of Makassar. This method ensures direct engagement with the target audience and guarantees equal participation opportunities for all the members. The questionnaire was structured into two primary sections. The initial section collected demographic information, including gender, age, educational background, and monthly income. The subsequent section comprises a series of measurement items pertinent to the research variables, which were adapted from instruments validated in the extant literature.

Table 1 presents the results of data collection, highlighting the key data and sample characteristics. The majority of respondents were female, comprising 213 individuals (82%). The age distribution of the respondents was predominantly over 42 years, with 120 individuals (46%), followed by the 34–41 years age group, which included 79 individuals (30%). Regarding educational attainment, most respondents were high school graduates (42%) and bachelor’s (40%). In terms of monthly income, the majority of respondents (56%) earned less than 5 million rupiah, while 31% earned an income within the 5–10 million rupiah range. These characteristics suggest a predominance of female respondents, who are generally older, with a relatively moderate level of education and modest income. This demographic profile implies that most respondents were likely housewives or adult women who engaged in small business activities as an additional source of income to support household needs. These findings also reflect the typical characteristics of MSME entities in the culinary sector, which are frequently managed by women to contribute to the family economy.

Table 1.

The respondent profiles.

3.4. Measurement Items

All constructs in the questionnaire were measured using multi-item scales adapted and contextually modified from previously validated instruments. Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). The measurement items for DFL, GS, DFI, and MSME performance were adapted and refined from prior studies.

Although DFL has been widely conceptualized as a multidimensional construct encompassing cognitive, behavioral, and awareness domains (Lyons & Kass-Hanna, 2021; OECD, 2024), this study operationalized DFL as an integrated construct that captures the essential digital financial competencies most relevant to MSME owners in Indonesia. The five indicators used in this study reflect core aspects of financial knowledge, digital knowledge, awareness, and the practical use of DFS (Choung et al., 2023).

GS construct measures the perceived effectiveness of government policies, programs, and initiatives in supporting MSME growth and digital adoption (Hossain et al., 2020). DFI construct reflects MSMEs’ access to, usage of, and perceived benefits from DFS, following the access, usage, and quality framework proposed by the Alliance for FInancial Inclusion (2019). Meanwhile, MSME performance was assessed using both financial and non-financial indicators, such as revenue growth, profit stability, and customer satisfaction and loyalty, consistent with Eller et al. (2020).

Each construct’s items were carefully modified in wording and contextual references to ensure clarity and relevance for Indonesian MSME respondents. Prior to the main data collection, a pilot test involving 30 respondents, comprising university students and MSME representatives, was conducted to assess item clarity, comprehensibility, and contextual suitability. In addition, the questionnaire was reviewed by a practitioner from the local Cooperative and SME Agency to ensure its content validity and linguistic appropriateness.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

To evaluate the measurement model, indicator reliability was assessed through external loadings. Hair et al. (2021) stated that an external loading above 0.70 is considered acceptable, indicating that the observed variables explain a substantial proportion of the variance in their respective constructs. Table A1 Appendix A, all indicators demonstrate satisfactory loading values above the 0.70 threshold. Strong loadings across constructs confirmed that the indicators adequately represented their respective latent variables, and no items fell below the minimum acceptable threshold. Therefore, all the indicators were retained for further analysis.

The measurement model was assessed to ensure reliability and validity of the constructs. This process involved evaluating internal consistency, reliability, and convergent validity using three primary metrics: Cronbach’s alpha (α), Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE).

Table 2 presents the convergent validity results. The constructs exhibited robust internal consistency, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha values between 0.840 and 0.914, surpassing the established minimum threshold of 0.70. Similarly, Composite Reliability values, ranging from 0.876 to 0.936, confirmed adequate internal consistency reliability, as CR values above 0.70 are considered acceptable (Hair et al., 2021).

Table 2.

Convergent Validity.

Convergent validity was assessed using AVE, with all constructs achieving AVE values above the recommended threshold of 0.50. This indicates that each construct explained more than half of the variance in its indicators, with AVE values ranging from 0.669 to 0.758, further supporting the indicators’ convergence in representing their respective latent variables. The results indicated that the measurement model met the psychometric standards required to establish reliability and construct validity. Consequently, this model was considered appropriate for additional examinations to assess the structural relationships between the variables in this study.

Discriminant validity assesses how distinctly a construct can be identified from other constructs present in the model. The Fornell–Larcker criterion was used to evaluate discriminant validity, indicating that the square root of the AVE for each construct should exceed its correlation with the other constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

In Table 3, all diagonal elements represent the square root of AVE, and these values exceed the correlations between the constructs outside the diagonal. For instance, the square root of the AVE for DFL (0.818) was greater than its correlation with GS (0.431), DFI (0.739), and MSME Performance (0.561). A similar pattern was observed for other constructs. These results affirm that each latent variable shares greater variance with its indicators than with the other constructs, thereby supporting discriminant validity among all constructs.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

Path coefficient analysis was performed using a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 subsamples to evaluate the structural relationships between constructs. The results in Table 4 show that both DFL and GS play significant roles in improving MSME performance, both directly and indirectly through DFI, with their patterns of influence revealing interesting dynamics.

Table 4.

Hypothesis testing.

DFL has a significant impact on MSME performance (β = 0.200; t = 3.016; p = 0.003). This finding indicates that the higher an entrepreneur’s ability to understand, manage, and use DFS, the better the business performance. Although significant, the direct influence of DFL on performance is relatively smaller than GS. GS has a stronger effect on MSME performance (β = 0.536; t = 8.192; p < 0.001). This reflects the importance of government policies and programs, such as training, incentives, capital assistance, and the provision of digital infrastructure, which directly enhance the capacity and productivity of MSME actors.

Incorporating DFI as a mediating variable reveals a more complex relationship. DFL not only directly influences performance but also plays an indirect role in enhancing DFI (β = 0.104; t = 2.172; p = 0.030). DFL functions as a strategic resource that enables entrepreneurs to understand financial technology and use it effectively to access financing, conduct transactions, and manage finances. Interestingly, when the same pathway is tested for GS, the mediation effect of DFI remains significant (β = 0.059; t = 2.116; p = 0.034) but to a lesser extent than the DFL pathway. Even though government programs have succeeded in expanding access to digital services, the ultimate impact on performance will be more optimal when MSME actors possess sufficient capacity to take full advantage of the various available opportunities.

These findings underscore the crucial role of DFI as a mediator between strategic resources and external support in driving the business performance. MSME actors with good DFL can access and utilize DFS effectively, ranging from online payments and digital wallets to technology-based financing, which in turn increases their business efficiency and productivity. DFI acts as an amplifier, magnifying the impact of DFL on the business performance. While GS remains important as an external factor that provides a supportive ecosystem and access to digital services, its impact becomes far more optimal when MSME actors have adequate digital capabilities. Therefore, enhancing knowledge is not just a supplementary factor but is also key to ensuring the effectiveness of government policies and programs in promoting sustainable MSME performance.

4.3. Robustness Test

To evaluate the robustness and generalizability of the structural model, a Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) was conducted following Cheah et al. (2020). The analysis was performed across three theoretically relevant and demographically balanced groups namely age, education, and revenue, to validate the stability of the structural model across key respondent characteristics. The gender variable was excluded because of an unequal sample distribution (male = 47; female = 213).

For the robustness assessment, the education variable was divided into two categories: high school and below (n = 116) and higher education, namely, associate, bachelor, master, or doctoral degrees (n = 144). The revenue variable was split into less than IDR 5 million (n = 145) and more than IDR 5 million (n = 115), while age was grouped into below 42 years (n = 140), and 42 years or older (n = 120). This two-segment classification was applied to balance subgroup proportions and simplify comparisons (Cheah et al., 2020).

Prior to the MGA, the Measurement Invariance of Composite Models (MICOM) procedure confirmed partial measurement invariance across all groups (p > 0.05), indicating that the comparisons were valid. The MGA test results in Table 5 indicate that the research model is stable and consistent across the education and revenue groups (p > 0.05). However, a significant difference was found based on age in the effect of DFL on PER (p = 0.044), where the impact of DFL on performance was stronger among younger MSME actors (<42 years old). Thus, this model can be considered quite robust and stable for most groups, although there is variation in the effect based on age.

Table 5.

Multi-group analysis (MGA) results.

4.4. Endogeneity Test

To ensure a deeper robustness of the structural model, an endogeneity test was conducted using the Gaussian Copula approach (Sarstedt et al., 2020a). This procedure detects potential reverse causality between the predictor and dependent constructs, which may lead to correlations between the independent variables and the error term. The results in Table 6 indicate that the direct relationships between DFL, GS, and MSME performance did not exhibit endogeneity (p = 0.085 and p = 0.125). In contrast, the indirect relationships mediated by DFI showed significant endogeneity effects, particularly in the pathways from DFL to MSME performance (p = 0.027) and GS to MSME performance (p = 0.017).

Table 6.

Gaussian copula endogeneity test.

These findings suggest that the interactions among DFL, GS, and MSME performance through DFI are mutually reinforcing. MSMEs with better performance tend to be more active in adopting DFS and may consequently attract greater government attention and assistance. Because the direct relationships among the key variables remain exogenous, the overall structural model can be considered stable, robust, and free from substantial bias.

5. Discussion

Drawing on the Resource-Based View (RBV), this study interprets how DFL and GS operate as strategic resources that enhance MSME performance, while DFI functions as a capability that transforms these resources into measurable outcomes. First, the findings indicate that DFL significantly affects MSME performance, underscoring the critical role of knowledge-based resources in the digital age. This study consistent with Kurniasari et al. (2023), Frimpong et al. (2022), Dura (2022), and Hossain et al. (2020), who showing that financial literacy and the adoption of fintech improve MSME performance through enhanced access to finance, innovation, and operational efficiency. DFL is a key element of an organization’s capabilities. By mastering digital payment platforms, online banking systems, and financial management applications, business owners can streamline transactions, speed up customer payment processes, and access funding avenues that may be difficult to reach. The integration of techno-financial literacy through the evaluation of new mechanisms can enhance MSME performance (Kulathunga et al., 2020). When MSMEs embrace DFL, they demonstrate behaviors such as effective financial planning, optimal budgeting, and informed financial management, all of which directly enhance their financial well-being (Gosal & Nainggolan, 2023). It is imperative for MSME owners to comprehend and implement digital payment methods to promote the use of digital transactions, thereby increasing customer satisfaction and sales potential and ultimately leading to an increase in MSME revenue and financial performance (Frimpong et al., 2022).

Second, the findings indicate that GS positively affects MSME performance. This study is consistent with Trieu et al. (2025), Zainuri et al. (2025), Gao et al. (2022), and Park et al. (2019). Government interventions, including policy regulations, digital training, financial assistance, and the provision of digital service information, serve as enablers to enhance MSMEs internal resource capabilities. Local governments are proactive in implementing initiatives to improve the sustainability performance. These efforts include training and guidance in areas such as marketing, digital strategies, and business licensing certification, all of which are designed to expand the market access for MSMEs and streamline administrative tasks. These targeted actions have resulted in tangible improvements, particularly in operational efficiency and overall business performance. The direct correlation between GS and performance through resource provision further substantiates the assertion that government assistance directly affects firm performance (Prasannath et al., 2024). Government policies targeting MSMEs should prioritize technology adaptation and promote the adoption of e-commerce banking (Ganlin et al., 2021) to ensure the sustainability of MSMEs. Firms that receive GS exhibit greater efficiency than those that do not (Vu & Tran, 2021). Financial and technical assistance should be directed towards bolstering marketing and innovation, such as through training in digital marketing, creativity, and problem-solving (Najib et al., 2021).

Third, the mediation analysis reveals that DFI plays a significant role in linking DFL to MSME performance. This study is consistent with Peter et al. (2025a), which demonstrate that DFL facilitates the utilization of digital-based financial services on women entrepreneur, such as mobile banking and electronic payments. This enhances access to financing and improves the business performance. Lal et al. (2025) asserted that sociodemographic, economic, and psychological factors influence an individual’s capacity to acquire DFL. Businesses with a high DFL are more capable of grasping the advantages and operational processes of DFS. DFL is pivotal in promoting the adoption of fintech behaviors (Zaimovic et al., 2025). This understanding facilitates easier access to these services, thereby enhancing business operations. DFL encourages women entrepreneurs to actively use formal banking channels which enhances financial inclusion expands access to financing and enables more effective management of capital and investment to improve business performance (Hasan et al., 2022). Furthermore, Widyastuti et al. (2024) asserted that individuals with higher financial literacy are more active in utilizing and accessing financial systems. The accessibility, ease of use, and benefits of DFS, such as digital wallets, digital credit, online payment platforms, and mobile banking, have become essential components in the operation of MSMEs, thereby impacting their performance. The adoption of technology in the financial sector directly contributes to company performance, particularly in the long term because of the complexity of technology implementation.

Fourth, this study provides new empirical evidence that DFI mediates the relationship between GS and MSME performance. The findings indicate that government initiatives aimed at expanding digital financial access not only have a direct impact on business performance but also enhance financial inclusion. DFI acts as a conduit that transforms policy interventions into tangible performance outcomes for MSMEs. GS facilitates the provision of infrastructure, policies, and access to various initiatives to eliminate barriers to entry the digital financial systems. The government assumes several crucial responsibilities in advancing the digital economy, such as crafting policies, investing in both human and organizational resources, fostering research and development along with innovation, and improving telecommunications and Internet infrastructure to ensure that the digital economy is inclusive (Aminullah et al., 2022). Strong regulatory support enhances user confidence and willingness to continue using Fintech services. Government incentives for digital financial initiatives can empower movements that leverage available technology and expedite inclusion (Daud & Ahmad, 2022). By enabling access to DFS and tools, businesses can address a range of obstacles and bolster their financial stability and growth potential (Johri et al., 2024). The relationship between DFI and institutional quality reveals that strong institutions greatly enhance the effect of DFI on economic growth (Meniago, 2025). This finding highlights the crucial role of robust institutions in fully leveraging DFS to promote sustainable economic progress.

Beyond the national context, this study extends the discussion to a regional comparative perspective in Asia. Cross-country evidence reveals that both DFL and GS play pivotal roles in advancing DFI and MSME performance, although their effects vary across economies. Ozili (2024) emphasized that DFI development in Asia remains uneven due to differences in digital infrastructure, regulatory capacity, and socioeconomic readiness. In India, Peter et al. (2025a) demonstrated that DFL fosters inclusion and business performance through mobile banking and e-payment usage, whereas Amnas et al. (2024) highlighted the importance of strong regulatory support in strengthening user trust in FinTech services. In Indonesia, Al-shami et al. (2024) found that DFL enhance MSME access to financial services and business stability, whereas Febriansyah et al. (2024) showed that fast and secure digital transactions improve operational efficiency. In Malaysia, Reza et al. (2024) underscored the significance of behavioral readiness in sustaining e-wallet adoption, while Nguyen (2024) in Vietnam demonstrated that DFL and infrastructural support accelerate fintech adoption and business innovation. Findings from Sri Lanka (Thathsarani & Jianguo, 2022) further confirm that DFI enhances both financial and non-financial performance through improved efficiency and broader access.

Additionally, the research findings offer further insights into the differences between the strengths of direct and indirect influences. GS exerts a stronger direct impact on MSME performance than DFL. The effectiveness of DFL in improving business performance does not depend solely on individual knowledge but also on contextual factors such as technological readiness, demographic characteristics, and socioeconomic conditions (Lal et al., 2025). Younger MSME owners tend to be more adaptive and confident in using DFS. In contrast, older entrepreneurs often exhibit greater caution toward digital tools, leading to lower levels of DFL and slower FinTech adoption. As a result, they may struggle to translate their financial knowledge into tangible performance outcomes. Consequently, the direct contribution of DFL to performance tends to be smaller than GS, which exerts a more structural and immediate influence through policy implementation, infrastructure provision, and financial assistance.

However, the opposite pattern emerges in the indirect effect of DFI, where DFL demonstrates a greater contribution to improved performance through DFI. From RBV perspective, these findings affirm that knowledge-based capabilities, such as DFI, require supporting conditions to produce real performance improvements. DFI serves as a mechanism that converts digital knowledge into actual financial participation. The adoption of DFS enables MSME actors to apply their DFL in practical financial activities. This mechanism aligns with Hasan et al. (2022), Al-shami et al. (2024), and Johri et al. (2024), who regard financial inclusion as a behavioral pathway transforming digital competence into financial empowerment. Higher DFL enhances financial decision-making, transaction efficiency, and MSME agility through greater engagement with digital services. Furthermore, GS remains a decisive factor in strengthening the digital environment that enables the optimal functioning of this mediation effect. The government plays a crucial role in building equitable digital infrastructure, providing affordable connectivity, and implementing policies that promote the widespread adoption of financial technology. Efforts such as improving national digital literacy, providing technology-based training, and developing a secure digital financial ecosystem will strengthen MSME capabilities in effectively utilizing DFS. Therefore, collaboration between government policies and the strengthening of digital literacy not only broadens financial inclusion but also ensures the sustainability of the digital transformation in the MSME sector.

6. Conclusions and Practical Implications

This study aimed to analyze the factors influencing MSME performance through DFI mediation. The findings reveal that DFI supports transaction efficiency and business growth by linking the effects of DFL and GS to the performance. DFL equips MSME with the basic knowledge and technological skills needed to access and manage DFS optimally. Concurrently, GS enhances institutional capacity through policies, training, and the provision of adequate digital infrastructure. However, mere access to these resources does not inherently ensure improved performance unless implemented through inclusive and relevant digital financial practices. DFI enables MSMEs to conduct transactions efficiently, access digital financing, expand their market reach, and maintain secure digital payment processes. The adoption of mobile banking and e-wallet platforms such as OVO, DANA, and GoPay demonstrates how DFS streamline financial management, accelerate cash flows, and improve customer experiences. These digital practices contribute directly to higher profitability, better operational performance and sustainable growth. This study offers new insights into the literature on DFI and MSME performance.

This study focuses on Indonesia’s culinary MSMEs, a dynamic and competitive sector that plays an essential role in employment creation and local economic growth. The sector’s adaptability to DFS reflects the increasing demand for transparent and efficient financial management. Digital finance provides accessible services that enhance operational efficiency, enabling firms to sustain their businesses for an extended period. Within the RBV framework, DFI functions as a capability that transforms DFL and GS, which represent internal and external resources, into competitive advantages and measurable performance outcomes. Practically, the results provide policy guidance for expanding DFL programs, improving digital infrastructure, and strengthening collaboration among government agencies, financial institutions and technology providers. Enhancing digital financial literacy across different demographic groups will ensure that all MSME actors can fully benefit from the digital transformation. Building an inclusive and adaptive digital financial ecosystem remains a shared priority for promoting equitable and sustainable economic development.

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study had several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, data were collected entirely through an online survey, which may have limited the participation of MSME owners who were less engaged with digital platforms. The reliance on self-reported responses also restricts the ability to verify data accuracy, despite the screening procedures applied during data collection. Second, the sample was predominantly women and older respondents, which may have affected representativeness. Robustness checks across several demographic groups were performed to ensure result consistency; however, these tests were limited in scope and should be expanded in future studies. Third, omitted demographic and socioeconomic factors, such as education, marital status, and household assets, were not included in the analysis because they were not part of the survey instrument. The omission of these variables may introduce potential omitted variable bias, which should be addressed in future research designs.

Fourth, the cross-sectional design restricts causal inference because relationships were observed at a single point in time. The study’s sectoral and regional focus limits its generalizability to other contexts. Although robustness analyses, including measurement invariance, multi-group, and endogeneity testing, confirmed model stability, minor endogeneity indications suggest possible reciprocal relationships, wherein higher-performing MSMEs tend to utilize digital financial services more actively and receive more institutional support. Therefore, future research should employ longitudinal designs, instrumental variable approaches, or panel data models to minimize endogeneity bias and strengthen the causal validity of the relationships examined.

Combining online and offline data collection methods in future studies may enhance respondent diversity and broaden participation. Such an approach could also improve data verification accuracy, making the results more representative of the realities faced by MSMEs in different regions. Furthermore, future research could expand the conceptual model by incorporating additional supporting variables, such as behavioral intention and usage behavior, within the context of digital technology adoption to deepen the understanding of the digital financial service transformation. Behavioral and usage intentions may help explain how digitalization translates into effective business practice. Finally, comparative and longitudinal studies across different sectors, regions, and economic contexts are important for evaluating the generalizability and causal direction of the relationships identified.

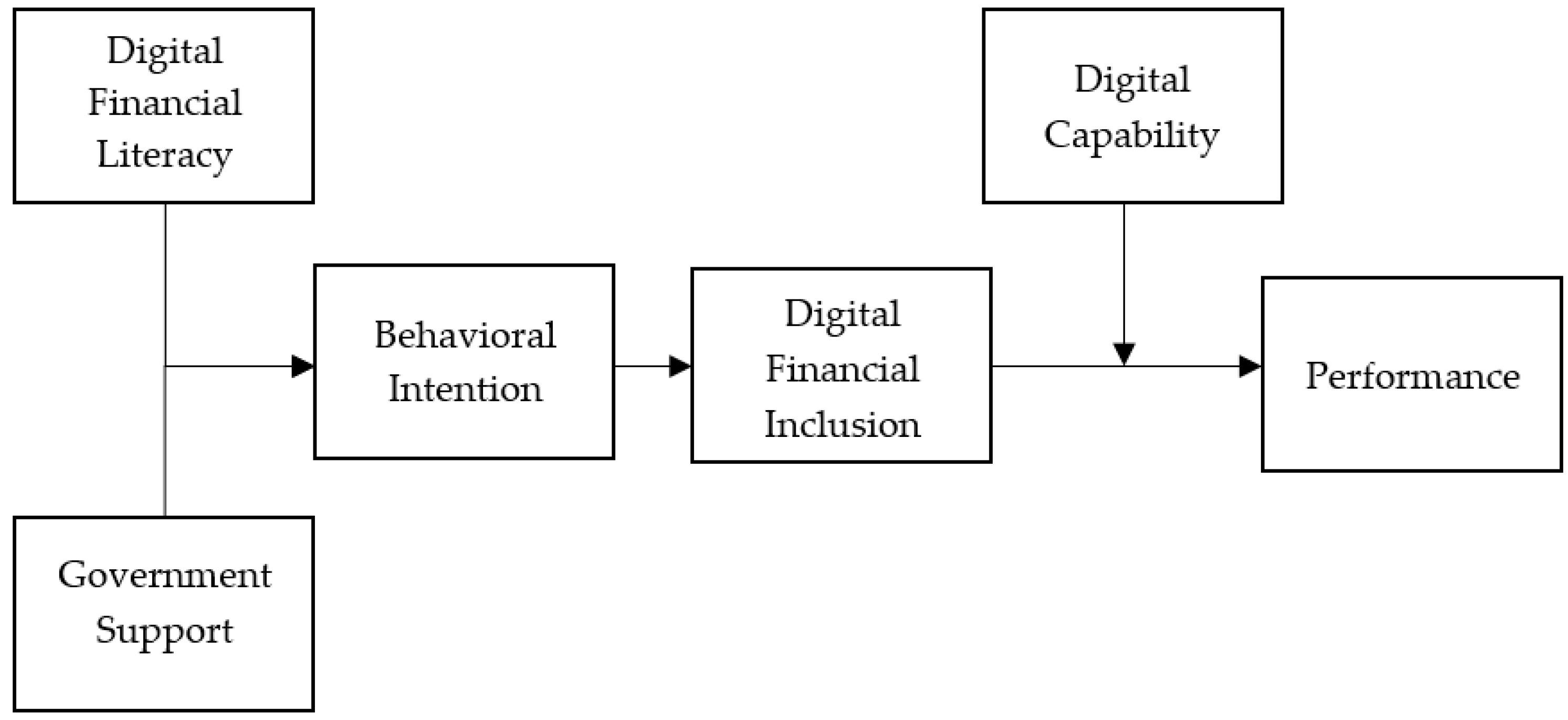

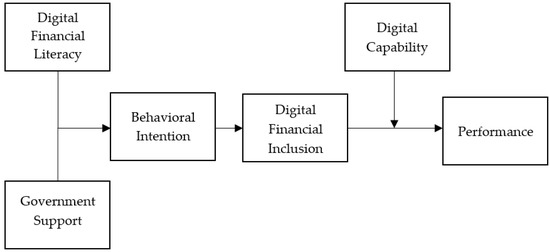

To guide future research, a conceptual diagram is proposed in Figure 2 to illustrate an extended model that integrates behavioral intention as a mediating variable and digital capability as a moderating variable, highlighting the dynamic pathways through which DFL and GS may influence performance through DFI.

Figure 2.

Proposed conceptual model for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.T., G.T.P., D.D., A.I.; methodology, C.T., G.T.P., D.D., A.I.; software, C.T.; validation, C.T., G.T.P., D.D., A.I.; formal analysis, C.T., G.T.P., D.D., A.I.; investigation, C.T., G.T.P., D.D., A.I.; resources, C.T., G.T.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.T., G.T.P.; writing—review and editing, C.T., G.T.P., D.D., A.I.; visualization, C.T.; supervision, G.T.P.; funding acquisition, C.T., G.T.P., D.D., A.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP RI), grant number 202401110400041.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it did not involve any sensitive personal data and/or invasive procedures. This research was conducted in accordance with the regulations of the Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Business, Hasanuddin University. The specific approval details are maintained by the department.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the blind peer reviewers and the handling editor for their constructive feedback, which greatly improved this work. We also appreciate the professors and lecturers of the Master of Accounting Study Program at Hasanuddin University, as well as the Incubator Supervision Team of the Makassar City Government Office, for their support in questionnaire distribution and data collection. This research was made possible through the support of the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5, 2025 version) to assist with language clarity improvement and text refinement. The authors reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement constructs and indicators.

Table A1.

Measurement constructs and indicators.

| Construct and Items | Loading Factors |

|---|---|

| Digital Financial Literacy (DFL) | |

| DFL1: I have knowledge in recording business financial transactions regularly | 0.715 |

| DFL2: I have good knowledge of digital payments | 0.827 |

| DFL3: I am aware of the various digital financial services available | 0.874 |

| DFL4: I am aware of the benefits of using digital financial services | 0.800 |

| DFL5: I have practical knowledge of using digital financial products and services | 0.864 |

| Government Support (GS) | |

| GS1: I feel the benefits of government policies in providing convenience and support for business growth | 0.836 |

| GS2: I have participated in government-organized programs or training to improve digital skills in business | 0.871 |

| GS3: the government is active in disseminating knowledge about how to access digital services that can help my business grow | 0.904 |

| Digital Financial Inclusion (DFI) | |

| DFI1: I can easily access digital financial services to support my business | 0.774 |

| DFI2: I have no difficulty opening an account or registering for a mobile banking account for my business | 0.780 |

| DFI3: I find digital financial services very helpful in conducting business transactions | 0.863 |

| DFI4: I believe that digital financial services can improve the growth and sustainability of my business | 0.851 |

| DFI5: I feel that digital financial services have a comprehensive interface and are tailored to my business needs | 0.823 |

| MSME Performance (PER) | |

| PER1: I regularly evaluate my financial performance to ensure I have achieved my goals | 0.832 |

| PER2: this business’s revenue has increased consistently | 0.883 |

| PER3: this business’s profits are stable and healthy | 0.889 |

| PER4: the capital I use has generated steadily increasing revenue | 0.895 |

| PER5: and my business has a loyal customer base that is satisfied with its products and services | 0.813 |

References

- Abdallah, W., Tfaily, F., & Harraf, A. (2025). The impact of digital financial literacy on financial behavior: Customers’ perspective. Competitiveness Review, 35(2), 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affandi, Y., Ridhwan, M. M., Trinugroho, I., & Hermawan Adiwibowo, D. (2024). Digital adoption, business performance, and financial literacy in ultra-micro, micro, and small enterprises in Indonesia. Research in International Business and Finance, 70(PB), 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliance for FInancial Inclusion. (2019). Alliance for financial inclusion policy model: AFi core set of financial inclusion indicators. Bringing Smart Policies To Life, 1–26. Available online: www.afi-global.org (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Al-shami, S. A., Damayanti, R., Adil, H., Farhi, F., & Al mamun, A. (2024). Financial and digital financial literacy through social media use towards financial inclusion among batik small enterprises in Indonesia. Heliyon, 10(15), e34902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminullah, E., Fizzanty, T., Nawawi, N., Suryanto, J., Pranata, N., Maulana, I., Ariyani, L., Wicaksono, A., Suardi, I., Azis, N. L. L., & Budiatri, A. P. (2022). Interactive components of digital MSMEs ecosystem for inclusive digital economy in Indonesia. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15(1), 487–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnas, M. B., Selvam, M., & Parayitam, S. (2024). Fintech and financial inclusion: Exploring the mediating role of digital financial literacy and the moderating influence of perceived regulatory support. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(3), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, J., Belas, J., Dziwornu, R., & Khan, K. A. (2022). Enhancing SME contribution to economic development: A perspective from an emerging economy. Journal of International Studies, 15(2), 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthanasius Fomum, T., & Opperman, P. (2023). Financial inclusion and performance of MSMEs in Eswatini. International Journal of Social Economics, 50(11), 1551–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm reources ad sustained competitive advantege. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J. H., Thurasamy, R., Memon, M. A., Chuah, F., & Ting, H. (2020). Multigroup analysis using smartpls: Step-by-step guidelines for business research. Asian Journal of Business Research, 10(3), I–XIX. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choung, Y., Chatterjee, S., & Pak, T. Y. (2023). Digital financial literacy and financial well-being. Finance Research Letters, 58(PB), 104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, S. N. M., & Ahmad, A. H. (2022). Financial inclusion, economic growth and the role of digital technology. Finance Research Letters, 53(2023), 103602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David-West, O., Iheanachor, N., & Kelikume, I. (2018). A resource-based view of digital financial services (DFS): An exploratory study of Nigerian providers. Journal of Business Research, 88, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dura, J. (2022). Determinants of financial literacy and digital literacy on financial performance in driving post-pandemic economic recovery. Journal of Contemporary Eastern Asia, 21(2), 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, R., Alford, P., Kallmünzer, A., & Peters, M. (2020). Antecedents, consequences, and challenges of small and medium-sized enterprise digitalization. Journal of Business Research, 112(2020), 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febriansyah, A., Syafei, M. Y., Narimawati, U., Chochole, T., & Stakic, A. J. (2024). How important is financial inclusion for the performance of MSMEs? Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 18(5), 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferilli, G. B., Palmieri, E., Miani, S., & Stefanelli, V. (2024). The impact of FinTech innovation on digital financial literacy in Europe: Insights from the banking industry. Research in International Business and Finance, 69(2024), 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research This, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, S. E., Agyapong, G., & Agyapong, D. (2022). Financial literacy, access to digital finance and performance of SMEs: Evidence From Central region of Ghana. Cogent Economics and Finance, 10(1), 2121356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganlin, P., Qamruzzaman, M. D., Mehta, A. M., Naqvi, F. N., & Karim, S. (2021). Innovative finance, technological adaptation and smes sustainability: The mediating role of government support during COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(16), 9218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Yang, X., & Li, S. (2022). Government supports, digital capability, and organizational resilience capacity during COVID-19: The moderation role of organizational unlearning. Sustainability, 14(15), 9520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosal, G. G., & Nainggolan, R. (2023). The influence of digital financial literacy on Indonesian SMEs’ financial behavior and financial well-being. International Journal of Professional Business Review, 8(12), e04164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of market research. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R., Ashfaq, M., Parveen, T., & Gunardi, A. (2022). Financial inclusion—Does digital financial literacy matter for women entrepreneurs? International Journal of Social Economics, 50(8), 1085–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. M., Ibrahim, Y., & Uddin, M. M. (2020). Finance, financial literacy and small firm financial growth in Bangladesh: The effectiveness of government support. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 35(3), 336–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johri, A., Asif, M., Tarkar, P., Khan, W., Rahisha, & Wasiq, M. (2024). Digital financial inclusion in micro enterprises: Understanding the determinants and impact on ease of doing business from World Bank survey. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I., Zakari, A., Dagar, V., & Singh, S. (2022). World energy trilemma and transformative energy developments as determinants of economic growth amid environmental sustainability. Energy Economics, 108(2022), 105884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulathunga, K. M. M. C. B., Ye, J., Sharma, S., & Weerathunga, P. R. (2020). How does technological and financial literacy influence SME performance: Mediating role of ERM practices. Information, 11(6), 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniasari, F., Lestari, E. D., & Tannady, H. (2023). Pursuing long-term business performance: Investigating the effects of financial and technological factors on digital adoption to leverage SME performance and business sustainability—Evidence from Indonesian SMEs in the traditional market. Sustainability, 15(16), 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawardhani, R., Ningrum, N. K., & Rinofah, R. (2023). Investigating digital financial literacy and its impact on SMEs’ performance: Evidence from Indonesia. International Journal of Professional Business Review, 8(12), e04097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, S., Bawalle, A. A., Khan, M. S. R., & Kadoya, Y. (2025). What determines digital financial literacy? Evidence from a large-scale investor study in Japan. Risks, 13(8), 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limanseto, H. (2022). Dukung UMKM naik kelas, pemerintah dorong transformasi ekonomi berbasis digital dan tingkatkan dukungan pembiayaan—Kementerian koordinator bidang perekonomian Republik Indonesia. Siaran Pers Kementrian Koordinator Bidang Perekonomian Republik Indonesia, 1–5. Available online: https://www.ekon.go.id/publikasi/detail/3902/dukung-umkm-naik-kelas-pemerintah-dorong-transformasi-ekonomi-berbasis-digital-dan-tingkatkan-dukungan-pembiayaan (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Liu, S., Gao, L., Latif, K., Dar, A. A., Zia-UR-Rehman, M., & Baig, S. A. (2021). The behavioral role of digital economy adaptation in sustainable financial literacy and financial inclusion. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(2021), 742118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A., & Kass-Hanna, J. (2021). A methodological overview to defining and measuring “digital” financial literacy. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1(217), e1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, K., Almuraqab, N., Moonesar, I. A., Braendle, U. C., & Rao, A. (2024). How critical is SME financial literacy and digital financial access for financial and economic development in the expanded BRICS block? Frontiers in Big Data, 7, 1448571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlutova, I., Spilbergs, A., Verdenhofs, A., Natrins, A., Arefjevs, I., & Volkova, T. (2022). Digital transformation as a driver of the financial sector sustainable development: An impact on financial inclusion and operational efficiency. Sustainability, 15(1), 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meniago, C. (2025). Digital financial inclusion and economic growth: The moderating role of institutions in SADC countries. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P. J., Huang, B., & L, T. (2019). The Need to Promote Digital Financial Literacy for the Digital Age. Asian Development Bank Institute, 1–9. Available online: https://www.global-solutions-initiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/t20-japan-tf7-3-need-promote-digital-financial-literacy.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Msomi, T. S., & Kandolo, K. M. (2023). Sustaining small and medium-sized enterprises through financial awareness, access to digital finance in South Africa. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 20(1), 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutamimah, M., & Indriastuti, M. (2023). Fintech, financial literacy, and financial inclusion in Indonesian SMEs. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 27(1/2), 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najib, M., Rahman, A. A. A., & Fahma, F. (2021). Business survival of small and medium-sized restaurants through a crisis: The role of government support and innovation. Sustainability, 13(19), 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumenkova, S., Mishchenko, S., & Dorofeiev, D. (2019). Digital financial inclusion: Evidence from Ukraine. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 16(3), 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. (2024, November). Improving vietnam’s financial inclusion and FinTech’s role in collaboration with credit institutions. Ey. Available online: https://www.ey.com/en_vn/improving-vietnam-s-financial-inclusion-and-fintech-s-role-in-collaboration-with-credit-institutions (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- OECD. (2024). OECD/INFE survey instrument to measure digital financial literacy. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD/EBRD. (2023). SME policy index: Eastern partner countries 2024 – Digital economy for SMEs (pp. 80–100). OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/sme-policy-index-eastern-partner-countries-2024_3197420e-en.html (accessed on 25 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K. (2024). Digital financial inclusion research and developments around the world. SSRN Electronic Journal, 4(2024), 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, I., & Ullah, S. (2022). Does digital financial inclusion matter for economic growth and environmental sustainability in OBRI economies? An empirical analysis. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 185(2022), 106489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S., Lee, I. H., & Kim, J. (2019). Government support and small- and medium-sized enterprise (SME) performance: The moderating effects of diagnostic and support services. Asian Business & Management, 19, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S., Elangovan, G., & Gupta, A. (2025a). Digital engagement in financial inclusion for bridging the gendered entrepreneurial financial gap: Evidence from India. Cogent Business and Management, 12(1), 2518492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S., Elangovan, G., & Vidya Bai, G. (2025b). Unveiling the nexus: Financial inclusion, financial literacy, and financial performance as catalyst for women-owned enterprises in India. Journal of the International Council for Small Business, 6(4), 721–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasannath, V., Adhikari, R. P., Gronum, S., & Miles, M. P. (2024). Impact of government support policies on entrepreneurial orientation and SME performance. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 20(3), 1533–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachinger, M., Rauter, R., Müller, C., Vorraber, W., & Schirgi, E. (2019). Digitalization and its influence on business model innovation. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 30(8), 1143–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, M. D. S. binti M., Tan, S. H., Chong, L. L., & Ong, H. B. (2024). Continuance usage intention of e-wallets: Insights from merchants. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 4(2), 100254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Cheah, J. H., Ting, H., Moisescu, O. I., & Radomir, L. (2020a). Structural model robustness checks in PLS-SEM. Tourism Economics, 26(4), 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2020b). Handbook of market research. In Handbook of market research (Issue September). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A. A., Alamoudi, H., Alharthi, M., & Glavee-Geo, R. (2023). Advances in mobile financial services: A review of the literature and future research directions. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 41(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirkhairulumam. (2025). Inkubator UMKM kota makassar. Available online: https://www.sirkhairulumam.com/project/inkubator-umkm-kota-makassar/ (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Tay, L. Y., Tai, H. T., & Tan, G. S. (2022). Digital financial inclusion: A gateway to sustainable development. Heliyon, 8(6), e09766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thathsarani, U. S., & Jianguo, W. (2022). Do digital finance and the technology acceptance model strengthen financial inclusion and SME performance? Information, 13(8), 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trieu, H. D., Van Nguyen, P., & Vrontis, D. (2025). The interplay of IT adoption, government support and firm performance: Mediating roles of innovation and resilience in Vietnamese SMEs. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 19(4), 935–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, Q., & Tran, T. Q. (2021). Government financial support and firm productivity in vietnam. Finance Research Letters, 40(2021), 101667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(1), 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyastuti, U., Respati, D. K., Dewi, V. I., & Soma, A. M. (2024). The nexus of digital financial inclusion, digital financial literacy and demographic factors: Lesson from Indonesia. Cogent Business and Management, 11(1), 2322778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W., & Wang, Y. (2023). Digital financial inclusion and quality of economic growth. Heliyon, 9(9), e19731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y., Qiao, Z., & Xie, G. (2022). Corporate resilience to the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of digital finance. Pacific Basin Finance Journal, 74(2022), 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Digital financial inclusion and sustainable growth of small and micro enterprises-evidence based on China’s new third board market listed companies. Sustainability, 12(9), 3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaimovic, A., Omanovic, A., Dedovic, L., & Zaimovic, T. (2025). The effect of business experience on fintech behavioural adoption among MSME managers: The mediating role of digital financial literacy and its components. Future Business Journal, 11(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuri, Z., Yasin, M. Z., Amijaya, R. N. F., Wilantari, R. N., & Vipindrartin, S. (2025). The role of government policy on the performance of MSMEs in the creative industry: Evidence from Jember Regency, East Java, Indonesia. Cogent Economics and Finance, 13(1), 2446657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulu-Chisanga, S., Chabala, M., & Mandawa-Bray, B. (2020). The differential effects of government support, inter-firm collaboration and firm resources on SME performance in a developing economy. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 13(2), 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).