Abstract

Financial institutions, researchers, and policymakers are taking steps to promote financial inclusion, a crucial aspect for social and economic development. This study explores the extent of financial inclusion (FI) in Zimbabwe’s commercial banks. This study employed a mixed-methods approach. A relationship mapping was conducted on the bank customers’ survey, and a thematic analysis was performed on bank executives to evaluate bank challenges and strategies. The findings confirmed positive strides towards achieving financial inclusion. Gaps in financial inclusion were identified in the high rate of people using informal channels and the limited policies in creating a conducive environment for financial inclusion. The study contributes to the ongoing debate by the World Bank in support of financial inclusion as an effective solution for countries like Zimbabwe, which is experiencing a severe macro crisis. The study adds to the emerging financial inclusion literature, proposing solutions to reduce financial exclusion in developing economies. Based on the study findings, policymakers should create a conducive environment for commercial banks and consumers of financial products and services in Zimbabwe.

1. Introduction

Financial inclusion is access to financial services and products for all population members, particularly the economically and socially marginalised (Ozili, 2018). The World Bank’s (2024) definition of financial inclusion emphasises accessing and using financial products and services. This is when “individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs—transactions, payments, savings, credit, and insurance—delivered responsibly and sustainably”. Winful et al. (2022) concur that financial inclusion is a sustainable development goal (SDG) whereby policymakers improve people’s livelihoods, reduce poverty, and advance economic development. The common emphasis on the definitions is that each member of the population should have access to available financial services. It was, therefore, important to measure the current status of financial inclusion in Zimbabwean commercial banks. This would determine the extent of financial inclusion in the country. The purpose of the study was to contribute to social and economic development through financial inclusion in Zimbabwe. Financial inclusion has been identified as an enabler for seven (7) of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). According to a report by the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF, 2025), financial inclusion is encompassed in SDG1 on eradicating poverty; SDG2 on ending hunger; achieving food security and promoting sustainable agriculture; SDG3 on profiting health and well-being; SDG5 on achieving gender equality and economic empowerment of women; SDG8 on fostering economic growth and jobs; SDG9 on supporting industry, innovation, and infrastructure; and SDG10 on reducing inequality.

1.1. Global Perspective on Financial Inclusion

There has been a global commitment to advancing financial inclusion as a key enabler for promoting equal opportunity and reducing poverty. The World Bank’s global database, which tracks financial inclusion, shows significant progress in financial inclusion between 2011 and 2017 (World Bank Group, 2021). Seventy-six percent (76%) of the world’s adult population has access to an account with a financial institution or mobile money provider, up from 51% in 2011. According to the World Bank Group (2021), COVID-19 played a significant role in the progress of financial inclusion. The pandemic led to increased digital merchant transactions in developing economies, rising to 37% of adults who made digital payments to retail businesses. Nearly one (1) in four (4) of these adults did so for the first time during the pandemic. However, financial inclusion remains a key challenge in the developing regions. Demirguc-Kunt et al. (2018) reported that 33% of the population owns a bank account at a formal financial institution in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). This was less than in any other region in the world (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2018). The disparity was attributed to the benefits of the digital age, which were not being shared equally, access gaps between men and women, poorer and richer households, and rural and urban populations (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2018). Ozili (2020) attributes the reasons for the large margins of the unbanked in developing countries to institutional racial profiling, high account maintenance fees, multiple taxation, and excessive bank charges. There was, therefore, a need for ongoing reflections on the state of financial inclusion in countries such as Zimbabwe, which have significant economic and development challenges.

1.2. Financial Inclusion in the Zimbabwean Context

Zimbabwe’s commercial banks have faced a prolonged macro crisis stemming from a malfunctioning economy (Chivasa & Simbanegavi, 2016). Obstacles to financial inclusion in Zimbabwe include a lack of trust in the banking system and high transaction costs for financial services (Barugahara, 2021).

Strides have been made toward financial inclusion in Zimbabwe. The government of Zimbabwe, through the Central Bank, is the driver for implementing and monitoring financial inclusion policies. A four (4) year National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFISI) was implemented in 2016. The goal was to improve access to financial services for women, youth, and disabled people from 69% to 90% by 2020. According to Chikweche et al. (2023), there have been notable successes in increasing the proportion of banked adults. Access to and the affordability of appropriate financial services increased to 90%. This was attributed to mobile money penetration (Chitimira & Torerai, 2021). Gaps after the National Financial Inclusion Strategy one (1) (NFIS 1) were limited access to mobile networks in some areas, high cost of mobile data, poor digital literacy, and prohibitive taxes associated with mobile money transactions (Chikweche et al., 2023).

Shortfalls in NFIS1 gave birth to National Financial Inclusion II (NFISII). The NFISII strategic vision for Zimbabwe aimed to empower Zimbabweans by building resilient and sustainable livelihoods. This was to be achieved by accessing and using appropriate, affordable, sustainable, and quality formal financial services in line with the national development aspirations (Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, 2022).

2. Literature Review

The literature review explored the theoretical underpinnings, conceptual framework, and the extent of financial inclusion in different countries and regions. The review analysed ways of achieving financial inclusion, barriers that inhibit financial inclusion, and the role of digitalisation in achieving financial inclusion.

2.1. Theoretical Underpinnings

According to the researchers, there is limited literature explaining the theories underlying the concept of financial inclusion. This study adopts systems theory, which explains the subsystems that interact with each other to achieve financial inclusion (Ozili, 2024). Harney (2024) describes systems theory as the relations and interdependencies that shape how work is conducted and managed. For this study, systems theory was classified into three sections: the government and the Central Bank, the banking sector, and bank customers. These three are the subsystems. The challenges and responses to a crisis within these subsystems are linked. This implies that any effect on one part of the system impacts the whole system. The process requires efforts from the government, the Central Bank, and banks to resolve the challenges. The outcome of the theory would be successful financial inclusion.

2.2. Conceptual Framework

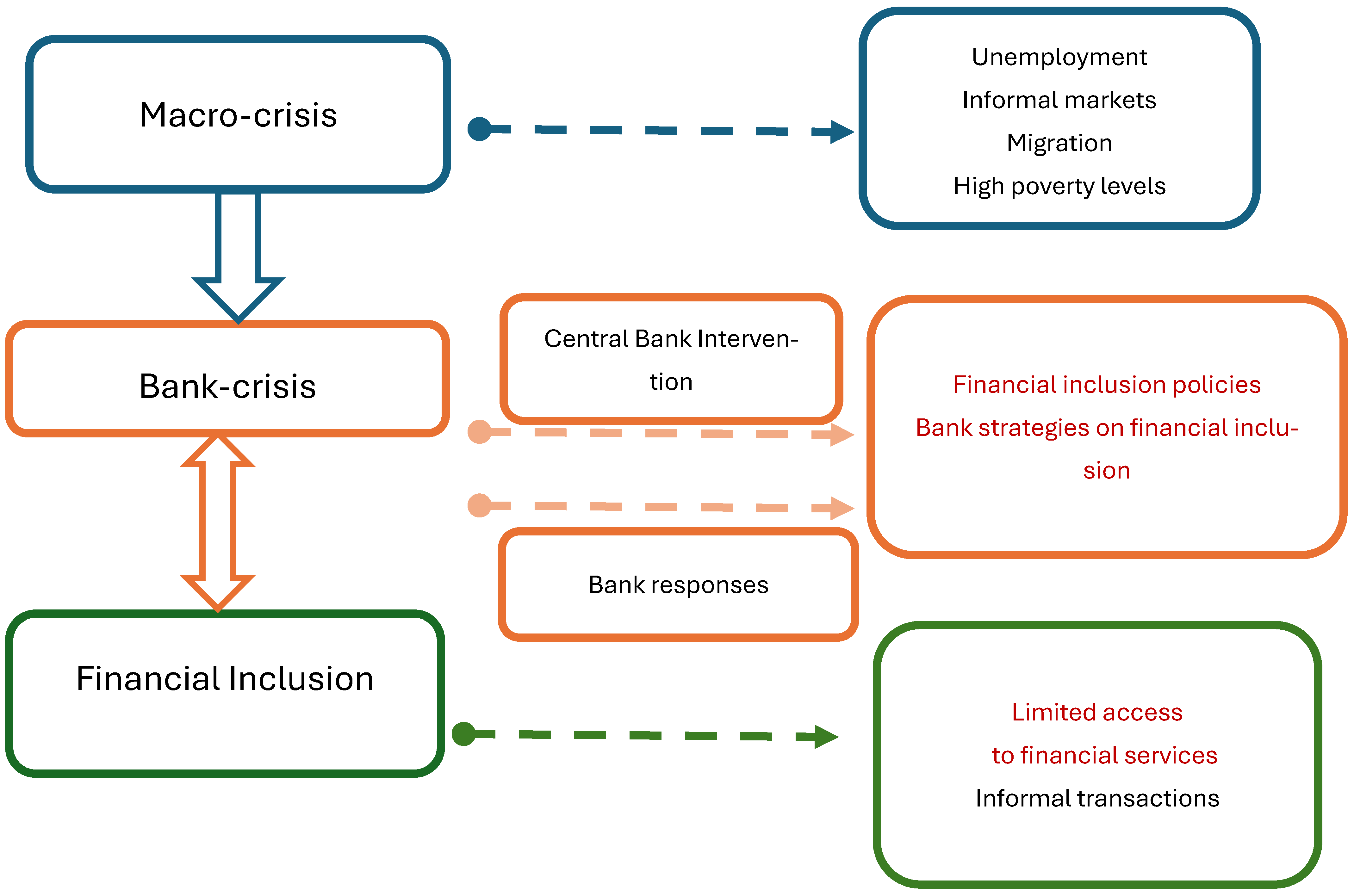

The effects of a financial crisis within the economy are passed down to the Central bank, banks, and customers. This creates challenges in achieving financial inclusion, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework. Source: Own formulation.

The conceptual framework shows how challenges in the macro environment are passed down to banks. The bank crisis causes challenges in availing financial services and products to the market. These develop into gaps that hinder financial inclusion. Policymakers intervene to curb the financial inclusion challenges. On the other hand, banks are liable to Central Bank policies and regulations on financial inclusion. Banks implement strategies to comply with financial inclusion policies. The conceptual framework, therefore, explores the extent of financial inclusion in Zimbabwe’s commercial banks. The broader conceptualisation of financial inclusion adopted in this study aligns with the updated Financial Action Task Force (FATF) definition (June 2025), which views financial inclusion as a key component of international financial integrity. According to FATF, financial inclusion enhances the transparency of financial systems, reduces the risk of illicit financial flows, and promotes economic stability by ensuring that individuals and businesses can engage with formal financial systems securely and equitably. Thus, while informal mechanisms like savings clubs and mobile money offer alternative access points, this study adheres to a formal understanding of financial inclusion, emphasising sustained, regulated access to mainstream financial products and services, rather than informal or transitional forms of participation”. Bank customers’ demographics and responses to bank strategies were compared with bank executive interview findings. This was done by assessing bank challenges and responses to financial inclusion.

2.3. Ways of Achieving Financial Inclusion

Varghese and Viswanathan (2018) emphasise that financial inclusion is a gradual initiative. The study showed the importance of time and steps to make secure and safe saving practices and facilitate improved financial services. Therefore, it was important to note the shortcomings in implementing financial inclusion to accelerate the process and achieve lasting progress. Policymakers were urged to develop policies based on a sustainable banking services delivery model and need-based products for rural and urban consumers. Ozili’s (2020) study explored conducive policy options that could be adopted to achieve financial inclusion. The study used a discursive approach and steps for achieving financial inclusion. Study findings were policies on reducing interest rates, introducing conditional low-interest rates, supporting monetary policies with social security payments, reducing taxes, using targeted government spending, supporting fiscal policies with conditional tax rebate and tax exemptions, financial inclusion, environment decoupling, de-risking the economic system, and ring-fencing banking for the poor. This implies the importance of cooperative efforts by the government, Central Banks, bank organisations, and banks to achieve financial inclusion.

2.4. Barriers to Financial Inclusion

Literature confirms factors that inhibit the progress of financial inclusion. Some of these factors were analysed by Yadav and Reddy (2021). The study examined the reasons for India’s low utilisation of banking facilities. The study was based on financial inclusion insights data for the Indian population. A truncated probit model was used to measure the incidence of under-banking. Findings showed a negative association between supply-side constraints and usage of banking services. This implied a low access to financial services in time and space, which hinders financial inclusion. Findings confirmed an uneven distribution of financial inclusion processes. The study recommended addressing financial literacy, micro incentives, and supply-side constraints to economic agents.

A similar study to assess barriers to financial inclusion was conducted by Mossie (2023). The study examined the drivers, barriers, and motivations associated with financial inclusion in Ethiopia. The result of the study showed that the determinants, barriers, and saving and credit motivations are different across individual characteristics. Distance to financial services, lack of documentation, and funds were significant barriers to formal account ownership. There was a need to ease bank account ownership requirements for accessibility and the usage of financial services.

2.5. The Role of Digitization in Achieving Financial Inclusion

Digitisation has played a pivotal role in financial inclusion. Literature confirms the digital role in achieving financial inclusion (Singh & Pushkar, 2019). The study was descriptive and used secondary data. The study found that digital technologies offer affordable and convenient ways for individuals, households, and businesses to save, make payments, access credit, and obtain insurance. Some segments of the nation were, however, not reached by the financial inclusion initiatives and programs. A positive outcome was that financial inclusion initiatives were in a progressive stage. Developing technology plays a vital role in bridging the financial inclusion divide in a nation.

According to Mutale and Shumba (2024), there has been notable progress in financial inclusion due to the introduction of digital technology in Zimbabwe. The study analysed ways of achieving financial inclusion in Zimbabwe through digital finance. This was done through a quantitative research design utilising econometric modelling. Study findings indicated a unit increase in digital financial innovation corresponding to approximately a 3.116906 unit increase in financial inclusion. There was a difference in the contribution to the traditional and digital innovation methods of achieving financial inclusion. Innovative digital technologies were recommended for the success of financial inclusion.

3. Methodology

To evaluate the extent of financial inclusion in Zimbabwe, 17 commercial bank executives were purposively identified as possible respondents. Participants were selected because of their designations and experience in the industry. The aim was to extract richly textured and relevant information for the study (Vasileiou et al., 2018). The actual participants comprised 11 former and current bank executives and one (1) representative from the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) and one (1) from the Deposit Protection Corporation (DPC). The other 4 potential respondents were not interviewed because data saturation was reached with 13 participants.

Bank customers’ demographics and responses from bank customers were extracted from the survey. These were stratified into three (3) categories: corporate, individual, and exited bank customers. 218 study participants responded to the survey. This resulted in a response rate of 86.8%. According to Howitt and Cramer (2017), response rates for self-administered surveys should be greater than 60%, and since the response rate for this study was 86.8%, it can be confirmed that it was acceptable. A mixed methodology was adopted for this study. The data sources and analysis included bank customers’ responses, customer surveys, and relationship mapping analysis. This study was mainly based on interviews with bank executives and customer survey data. The demographics and customers’ responses on financial inclusion initiatives were compared with findings from the bank executive interviews. Bank executives’ interviews were analysed using thematic analysis. The analysis covered the challenges and strategies of financial inclusion.

Thematic codes in this study were derived through an inductive analysis of qualitative data collected from interviews with 13 bank executives and regulatory stakeholders. Each participant’s insights were coded based on recurring themes aligned with this study’s objectives. The process involved open coding of the interview transcripts, where participant identifiers such as BE10, BE07, and BE13 were used to track sources of key themes. For example, the theme “digitalisation, access and inefficiency” emerged from statements like BE09’s observation that remote areas lack internet connectivity and digital infrastructure, and BE13’s remark that “our technology is not up to standard,” highlighting systemic barriers to digital financial inclusion. The theme “unemployment and the rise of the informal economy” was derived from BE13’s note on business closures pushing activity into informal markets, and BE07’s comment on how formal channels were “disintermediated massively.” Similarly, “high poverty levels” was coded from BE13’s assertion that many people are “living below the poverty datum line,” and BE06’s explanation that customers “couldn’t afford to save money to put in the bank.” The code “encouraging deposits from the informal market” was captured through BE10’s suggestion to “find a way of getting money and deposits” from the informal sector. Lastly, the theme “collaboration for financial inclusion” was grounded in BE10’s recognition of the importance of partnerships between banks and mobile money operators, and BE07’s account of setting up outreach units in excluded communities. These thematic codes were then systematically applied to analyse strategic responses and barriers to financial inclusion in Zimbabwe’s banking sector.

Bank Customer Demographics on Financial Inclusion

Bank interviews were compared with customers’ demographics and relationship mapping responses. Relevant demographic information was selected from the bank customers’ survey. Table 1 shows the demographics for comparison with bank interviews.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of respondents (N = 205).

The respondents were asked to indicate the years/duration they have had their bank accounts. The majority of participants indicated that they have had their bank accounts for a period ranging between 10 and 15 years. This was followed by those who had owned their bank accounts for 15–20 years.

Bank customers were asked how often they used their bank accounts, of which about 33.5% of the respondents used their bank accounts once a month. This was attributed to the participants’ reliance on formal employment, whose salaries were processed through the banks only once a month.

4. Relationship Mapping Findings

Relationship mapping in this study examined and made it possible to understand linkages between variables. Relationship mapping was conducted on bank account statuses, customers’ responses to other forms of transacting, and the effects of bank strategies on customers’ accounts.

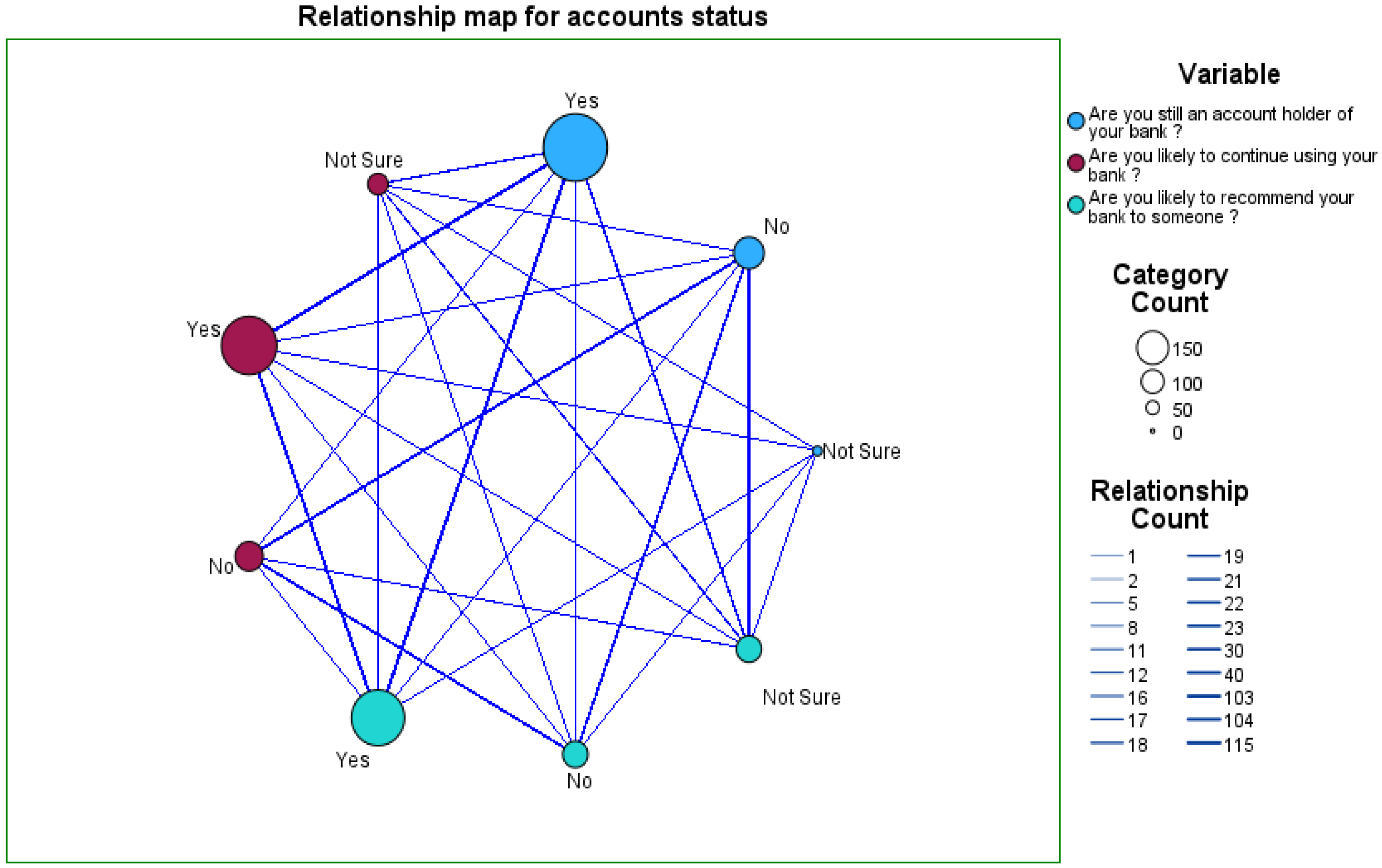

4.1. Relationship Mapping of Bank Account Status

The first analysis on relationship mapping was conducted on bank account statuses. This comprised responses on customers who wanted to hold on to their accounts, who wanted to continue using bank accounts, and those who would recommend their banks to others. The output of the relationship mapping is shown in Figure 2 below:

Figure 2.

Analysis of the relationship mapping on bank account status. Source: Field data (N = 205).

Figure 2 shows the results on the account statuses of study participants. Most study participants indicated they had bank accounts. This was followed by participants who were likely to continue using their bank accounts. The connection between participants who had bank accounts and were likely to continue using them showed a strong link. This was represented by the thick connection line between the two 2 variables. This implies that study participants who indicated owning a bank account were likely to continue using it. This can be described as stagnant progress towards achieving financial inclusion. This is because participants who had bank accounts indicated that they would not recommend their banks to others. There was a weak link between the two 2 variables. This may imply that participants with bank accounts were for convenience purposes and that they were unwilling to recommend their banks to others. Participants probably used their bank accounts for salary purposes or other regular transactions. The implication is a stagnant drawback to financial inclusion.

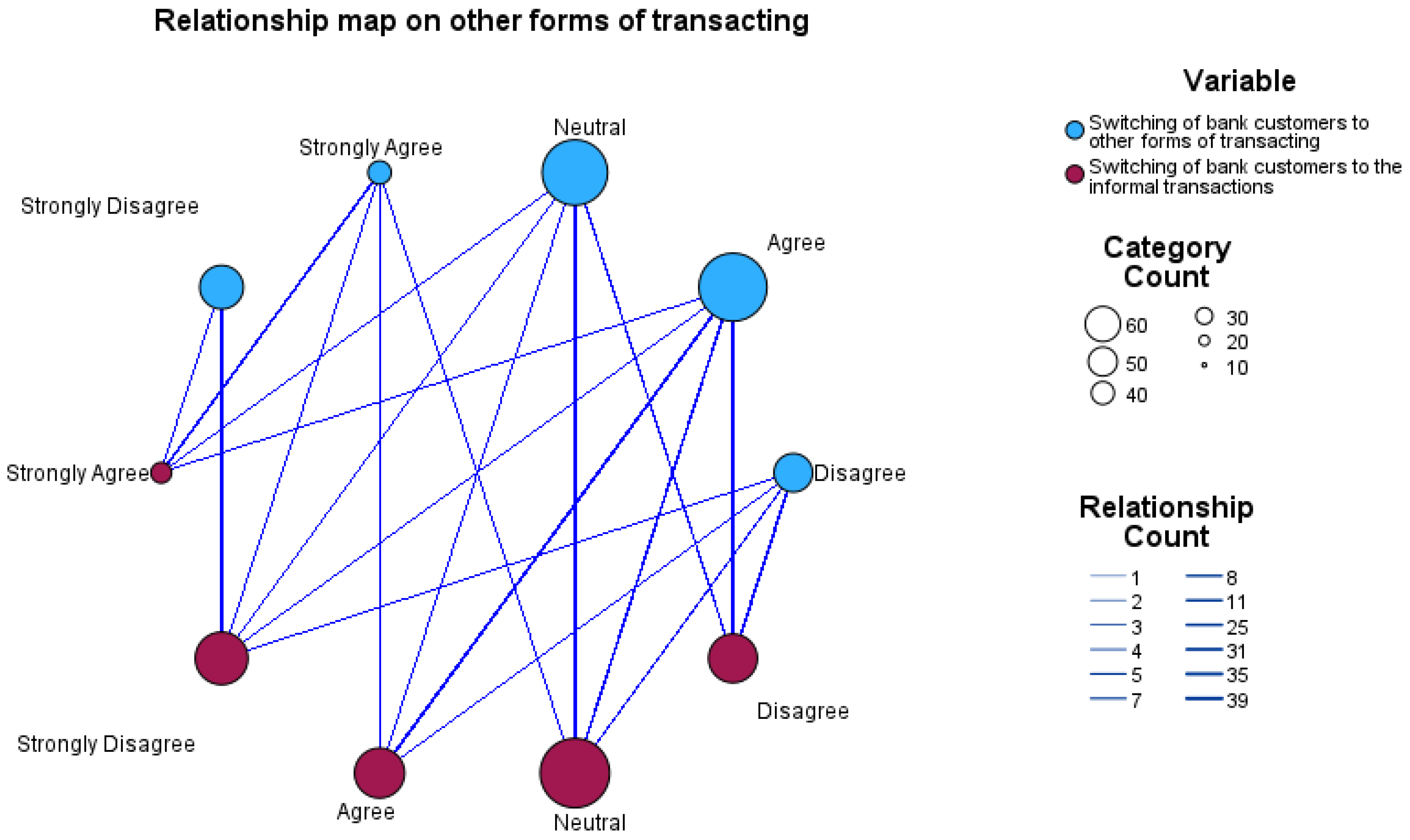

4.2. Relationship Map Analysis on Customers’ Responses to Other Forms of Transaction

Relationship mapping analysis was conducted to assess the bank customers who had switched to other forms of transacting. In the study, other forms of transacting are Mobile Network Operators (MNOs), Financial Technologies (FinTechs), microfinance institutions, and social savings clubs. Relationship mapping determined if there were any links between customers switching to other forms of transacting and informal transacting. Figure 3 shows the relationship between bank customers switching to other forms of transacting and informal transacting.

Figure 3.

Relationship map analysis on other forms of transacting. Source: Field data (N = 205).

Figure 3 shows a positive relationship between bank customers switching to other forms of transacting and informal transacting. Both had a ‘neutral’ response. This implies that most bank customers were ‘neutral’ on switching to other forms of transacting and informal transacting. The ‘neutral’ response on both variables may indicate that bank customers were using all forms of transacting available to them. This implies that financial inclusion can be achieved both formally and informally. Customers may not be included in the formal banking channels but use the informal market to transact and access loans. Some bank customers may also be making use of the digital channels. This means financial inclusion is taking place, but on different platforms. Ugochukwu (2024) stated that informal ways of accessing banking services, such as savings clubs, facilitate financial inclusion. Banks should take advantage of customers using informal channels by implementing appropriate strategies.

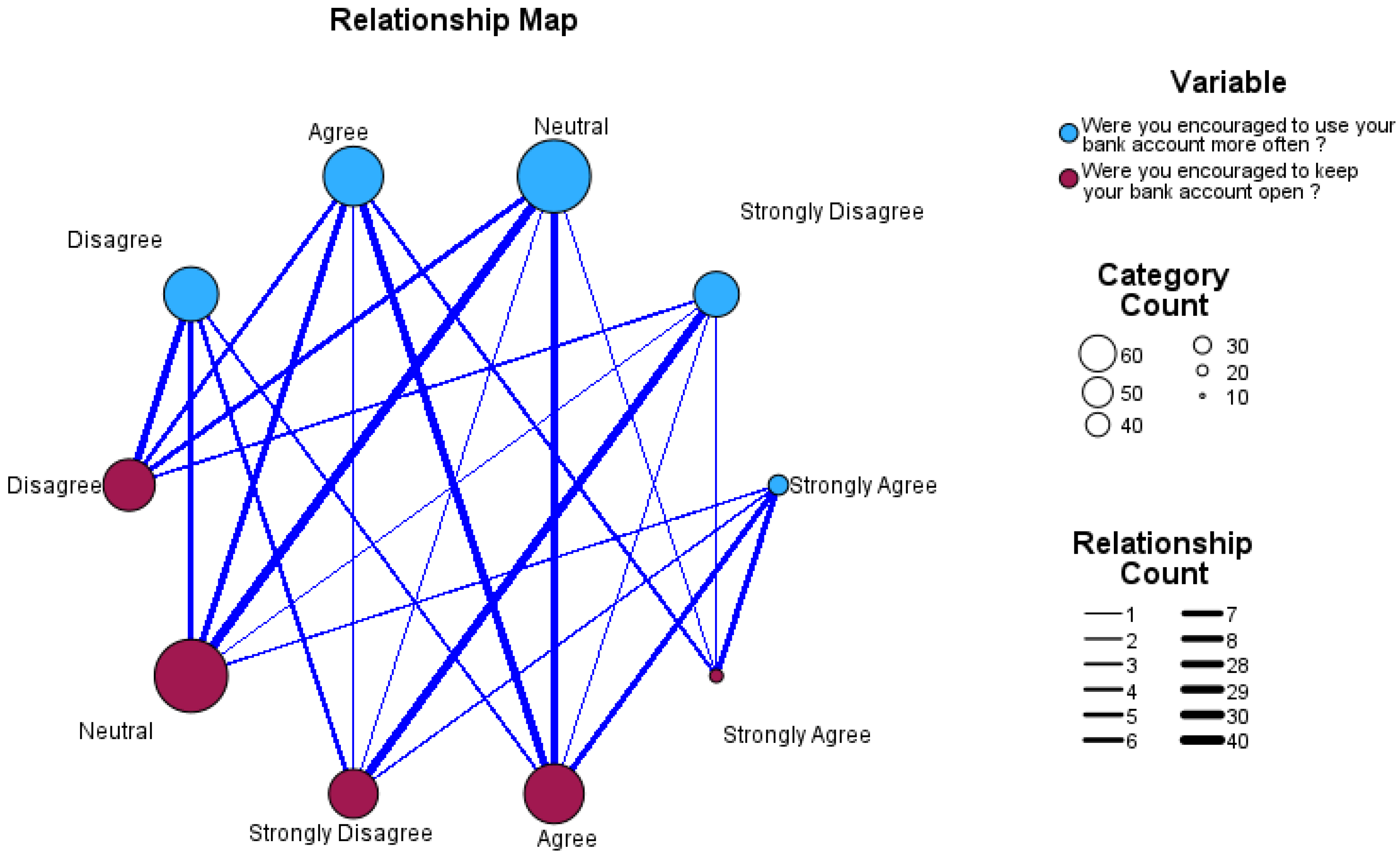

4.3. Effects of Banking Initiatives on the Status of Bank Accounts

The last category of the relationship mapping assessed whether banks had adequately addressed the issues of dormant accounts and the closing of bank accounts. Dormant accounts were those not often used by customers or for transient depositing. Closing bank accounts implies a situation where bank customers opt to close their accounts and exit the banking system. In this context, bank customers were asked the following questions: ‘Were you encouraged to use your bank account more often?, Were you encouraged to keep your account open?’ The relationship analysis is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Customer responses to account statuses. Source: Field data (N = 205).

There was a positive response from customers who stated that banks had encouraged them to use their bank accounts often and to keep their accounts open. The highest responses were on ‘neutral’ for the use of accounts regularly and the retention of bank accounts. The weakest link of the two (2) variables was when customers ‘strongly agreed’ that banks had encouraged them to keep their accounts open. On the other hand, there was a ‘neutral’ response from bank customers’ frequent use of accounts. Relationship map analysis on these two (2) variables indicates a gap that banks need to address. The weakest link of the two (2 variables confirms this gap. This was where there was a ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’ response. This implies that banks have not adequately addressed the financial inclusion gap. This can be explained by the banks not reaching out to bank customers who had migrated and those who had opted for informal transacting or digitalised transactions. There was a need to tailor-make strategies that catered to the excluded population.

5. Bank Challenges in Achieving Financial Inclusion

Financial institutions, particularly banks, play a pivotal role in promoting economic growth and stability by ensuring access to essential financial services for all segments of society. However, understanding the challenges banks face in pursuit of financial inclusion is crucial for developing effective policies and strategies that bridge existing gaps. By thoroughly analysing these obstacles, from technological barriers and competing informal markets to socioeconomic factors such as poverty, policymakers, regulators, and financial institutions can design more targeted interventions that address the root causes of financial exclusion. This analytical approach enhances the efficacy of inclusion initiatives, contributes to creating more resilient financial systems that support sustainable economic development, and reduces inequality across diverse populations and regions.

5.1. Digitalisation, Access and Inefficiency

Zimbabwe is lagging in including remote communities digitally. Disparities attributed to the inclusion of remote communities are a lack of stable electricity supply and poor or limited infrastructure required to access digital products. According to Chitokwindo et al. (2014), 65% of the Zimbabwe population in rural areas form the majority of the unbanked. BE09 said, “Surely it becomes tricky for you to expect somebody in a remote area to be doing a lot more internet banking because they perhaps do not have a gadget connected to the internet. Sometimes the connectivity is so poor. There is no Wi-Fi connectivity. Even the mobile network operators have a few network infrastructures, like towers/boosters here there is little service.” Additionally, the technology standards in Zimbabwe were said to be low and inefficient. BE13 said, “What I can say here in Zimbabwe is that our technology is not up to standard. If you have up-to-date technology, you can drive efficiency.” The low standards are caused by factors such as a shortage of foreign currency to acquire infrastructure, high inflation rates that erode the disposable income of users, lack of knowledge and high levels of brain drain, load shading, and lack of infrastructure in rural areas. This means that macro crisis effects in the country are linked to the challenges faced by banks in achieving financial inclusion. There is a need for creating an enabling environment, politically, technologically, and economically, for banks to implement effective financial inclusion strategies.

5.2. Unemployment and the Rise of the Informal Economy

The closing of companies due to the macro crisis resulted in an informal economy. This resulted in a significant chunk of money being circulated outside formal circles through vending or transacting. Despite the informal sector being a major part of the economy in most African countries and providing income and employment for those marginalised from the formal economy, it has been forgotten by policymakers and is often financially excluded. BE13 confirms that, “I spoke about companies closing. What it has then done is push the activity into the informal sector.” The resultant effect of the informal economy is the replacement of bank roles. The bank’s intermediary role of accepting deposits and availing loans was taken up by the informal economy. BE07 said, “Because most transactions would happen outside the formal banking system, the official channels got disintermediated massively.” Relationship mapping on bank customers resorting to informal transacting showed a ‘neutral’ response. This indicates a gap that is prevalent in addressing financial inclusion. The gravity of the informal market in Zimbabwe was confirmed in an Economic Government Watch (2022) paper and is estimated to have caused a loss of over US$32 billion in financial flows between 2000 and 2020. In 2019 alone, according to the chairperson of the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission, Zimbabwe lost an estimated US$3 billion through informal as well as illegal outflows.

The challenges show how the macro crisis affects banks and slows down the financial inclusion strategies. This can be shown by the high rates of unemployment, which gave rise to the informal market. This pushed bank customers away from the banking sector, creating a gap between the two. The implication is a gap that calls for banks and policymakers to implement strategies that retain the market and help the economy.

5.3. High Poverty Levels

Zimbabwe’s poverty levels are significantly high. According to an African Development Bank report (2023), poverty was estimated at 38.7% in 2023. Poverty is considered high at a rate of 20% or more. The poverty levels challenge was mentioned by BE13 when stating, “a few major ones are the rising poverty levels, I think from my bank or financial institution perspective, it becomes critical and I’ve seen some or a lot more people sliding into poverty, living below the poverty datum line in Zimbabwe”. Poverty levels contribute to discouraging bank customers from saving and investing. This affects the bank’s viability as customers resort to transient deposits, unpaid loans, or not using the banking system. Relationship map analysis from bank customer surveys confirms that banks have been unable to resolve the challenges of depletion and closure of bank accounts. The repercussions are the financial exclusion of the majority of people. BE06 commented on the effects of poverty on banks and said, “The salaries were not able to give a livelihood to a customer. He couldn’t afford to save money to put in the bank. He couldn’t afford to pay school fees for his children, buy groceries, let alone find money to pay the loan from the bank.”

BE10 mentioned migration as one of the effects of high poverty levels in the country. The interviewee said, “We also look at the migration that also took place, the unemployment rate that also played havoc in terms of having to let go, close some accounts, there were job losses, retrenchments that also affected bank employees, bank customers, government, and stuff.” The findings confirm the many facets of poverty and its effects on financial inclusion. It also implies the gravity of repercussions caused by declining poverty levels in a macro crisis. Policymakers and banks should work amicably to achieve financial inclusion in a macro crisis. This could be achieved by tailoring products that cater to the financially excluded.

6. Financial Inclusion Strategies

Bank executives were interviewed to evaluate the extent of financial inclusion initiatives in the market. Themes that emerged from the bank strategies on financial inclusion were encouraging deposits from the informal market, collaboration, and policy initiatives.

6.1. Encouraging Deposits from the Informal Market

The informal market arose due to the high unemployment rate in the country. This sector has been excluded from the formal banking channels because of its characteristics, including a lack of trust in the banks (Njaya, 2014). The informal market resorted to informal transactions or putting their money under the pillow for safekeeping. The informal channels of transacting effects are two-fold. It resulted in the loss of business for banks to informal channels and access to credit facilities in the market. However, the relationship map analysis on the bank customers’ survey indicates a ‘neutral’ response to switching to other forms of transacting. This implies an inclination towards achieving financial inclusion. Bank customers’ demographics (85.7%) indicate a positive response to achieving financial inclusion by having bank accounts. The indication of an increase in banked people makes it easier for banks to implement strategies of encouraging deposits. BE10 said, “You need to find opportunities to include them. Find a way of getting money and deposits, and everything from them. Because between you and me, and that informal sector, that’s where a lot of things happen. And that’s where the money is flowing.” Bank strategies of encouraging deposits from the informal market indicate positive results toward financial inclusion and are therefore recommended.

6.2. Collaboration for Financial Inclusion

Collaboration for financial inclusion mainly dealt with partnering with MNOs and FinTechs. MNOs and FinTechs have been commended for contributing to financial inclusion success. Marginalised groups without access to formal services and products were said to have benefited from MNOs and FinTechs (CGAP, 2024). The benefits accrued from partnering with MNOs and FinTechs, and the lack of capacity to cope with digitalisation, made banks embrace MNOs and FinTechs. BE10 said, “And in certain instances, you then realise that collaboration is important. There is a collaboration between banks and non-traditional banks and MNOs, where banks partner with mobile money operators.” Additionally, 27.3% of bank customers agreed that banks had been able to implement strategies to deal with customers’ preferences for digital channels. This indicates a positive perception of banks’ adaptability in this evolving landscape. The research findings revealed that a significant majority of bank customers (76.6%) reported successfully adapting to technological innovations implemented within the challenging macroeconomic landscape. This aligns with existing financial inclusion and technology literature, emphasising digitalisation’s potential to enhance access to a broader spectrum of financial products (Haider et al., 2018). Digitalisation has substantial potential to bridge the gaps in the existing inequalities of financial inclusion. Studies have highlighted inequalities in such factors as affordability and access to technology. To effectively promote financial inclusion in Zimbabwe, a multifaceted approach is required that addresses these critical accessibility and affordability concerns for all bank users. This finding aligns with observations from Finscope (2022), which highlighted successful bank strategies in mitigating the competitive threat.

Other collaborations mentioned in the study findings were reaching out to marginalised communities through collaboration with government institutions. BE07 mentioned setting up specific units that targeted excluded communities and partnering with remote institutions.

The lack of capacity to cope with digital innovations paved the way for partnering with MNOs and FinTechs. Collaboration made it possible for banks to reach out to the marginalised community. The study recommends collaboration to cope with gaps in financial inclusion.

6.3. Policymakers’ Initiatives on Financial Inclusion

There is a need for policymakers to take an active role in facilitating financial inclusion success. The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe took the initiative to implement the Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS1). This was launched on 11 March 2016 by the Minister of Finance and Economic Development (Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, 2022). The launch represented a major milestone in the efforts to establish an inclusive financial system that facilitates the participation of previously unbanked and underserved Zimbabweans in economic activities. The efforts of the Central Bank were confirmed by BE05 and BE07. The bank executives said that customers accessed financial services more than before because of financial inclusion. BE05 said, “I think financial inclusion is one of the big things initiated by the Central Bank.” Whilst the Central Bank’s intervention is responsible for policy and regulation, at a national level, there is a need to create a conducive environment for financial inclusion success. These would be in areas such as internet accessibility, promoting trust in banks, and economic crisis issues that retard progress on financial inclusion.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Financial inclusion is important for economic development and sustainability. Including low-income communities or the unbanked contributes to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of reducing poverty, reducing inequalities, and fostering economic growth. There have been notable achievements in financial inclusion. This has emanated from the NFSI and the NFISII by the government, the Central Bank, and other banks.

The study explored the extent of financial inclusion in the financial sector in Zimbabwe through a customer survey and interviews with bank executives. The results were analysed through relationship mapping and thematic analysis, respectively. Qualitative findings from the bank executive interviews were compared with the relationship mapping analysis from the survey. The results captured the extent of financial inclusion in the country.

There were positive findings on the strides towards achieving financial inclusion in Zimbabwe. These are factors such as the adoption of digital forms of transacting and policymakers’ efforts in financial inclusion. Gaps in financial inclusion were the high rate of people using informal channels and the limited intervention of policymakers in creating a conducive environment for financial inclusion. This was because some challenges in achieving financial inclusion are beyond the banks’ capability. The fragile economy in the country, poor technology standards, and its affordability were some of the challenges that should be addressed at the national level.

The study recommends a holistic approach to the success of financial inclusion in the country. The approach will include the participation of policymakers, banks, representative organisations, customers, MNOs, and FinTechs.

8. Limitations of This Study

The findings in this study can only be generalised to urban settings. It did not include the rural communities. Further studies may want to look at financial inclusion in a different economic setting, other than Zimbabwe. This would be compared with the extent of financial inclusion in Zimbabwe to give a broader perspective.

Author Contributions

A.K. conceptualised and wrote this study, and B.M. validated, visualised, and supervised this study. H.M.v.d.P. validated, visualised, and supervised this study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by University of South Africa Ethical Review Committee (Code: 2022_SBL_DBL_030_FA).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barugahara, F. (2021). Financial inclusion in Zimbabwe: Determinants, challenges, and opportunities. International Journal of Financial Research, 12(3), 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikweche, T., Chaora, B., & Cross, R. (2023). Financial inclusion in Zimbabwe: Re-imagining prospects for inclusive stakeholder involvement and national development. African Journal of Inclusive Societies, 2(1), 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitimira, H., & Torerai, E. (2021). The nexus between mobile money regulation, innovative technology and the promotion of financial inclusion in Zimbabwe. Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal/Potchefstroomse Elektroniese Regsblad, 24, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitokwindo, S., Mago, S., & Hofisi, C. (2014). Financial inclusion in Zimbabwe: A contextual overview. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20), 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivasa, S., & Simbanegavi, P. (2016). Financial inclusion in Zimbabwe post hyper inflationary period: Barriers and effects on societal livelihoods, a qualitative approach: A case of Matebeleland North. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 18, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Consultative Group to Assist the Poor Organisation (CGAP). (2024). Financial inclusion. CGAP. Available online: https://www.cgap.org/financial-inclusion (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2018). The global FinDex database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank eBooks. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Government Watch. (2022). Illicit financial flows emptying Zimbabwe of its wealth. Economic Government Watch. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/704523905/Economic-Governance-Watch-10-2022-Illicit-Financial-Flows (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Finscope. (2022). FinScope Zimbabwe 2022 consumer survey. Available online: https://finmark.org.za/Publications/FinScope_Zimbabwe_2022_Consumer_Presentation.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Haider, Z. S., Rahim, A. Z., & Aslam, F. (2018). Antecedents of online banking adoption in Pakistan. International Research Journal of Arts and Humanities Empirical Study, 47, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Harney, B. (2024). Systems theory (pp. 312–318). Edward Elgar Publishing eBooks. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howitt, D., & Cramer, D. (2017). Understanding statistics in psychology with SPSS (7th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Mossie, W. A. (2023). Financial inclusion drivers, motivations, and barriers: Evidence from Ethiopia. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2167291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutale, J., & Shumba, D. (2024). The impact of digital finance on financial inclusion in Zimbabwe. African Journal of Inclusive Societies, 4, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njaya, T. (2014). Nature, operations and socio-economic features of street food entrepreneurs of Harare, Zimbabwe. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 19(4), 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K. (2018). Banking stability determinants in Africa. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 14(4), 462–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K. (2020). Financial inclusion research around the world: A review. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K. (2024). Systems theory of financial inclusion. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe. (2022). National financial inclusion strategy. Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe. Available online: https://www.rbz.co.zw/documents/BLSS/FinancialInclusion/FinancialInclusionStrategy.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Singh, V., & Pushkar, B. (2019, January 5–7). A study on financial inclusion: Need and challenges in India. 10th Conference on Digital Strategies for Organisational Success, Gwalior, India. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugochukwu, P. N. A. I. (2024). Informal financial savings practices to facilitate formal financial inclusion. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 24(3), 1970–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCDF. (2025). Financial inclusion and the SDGs. UNCDF.ORG. Available online: https://www.uncdf.org/financial-inclusion-and-the-sdgs?ref=hackernoon.com (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Varghese, G., & Viswanathan, L. (2018). Financial inclusion: Opportunities, issues and challenges. Theoretical Economics Letters, 8(11), 1935–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., & Young, T. (2018). Characterizing and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over 15 years. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winful, E. C., Opoku-Asante, K., Mensah, M. O., & Quaye, J. N. A. (2022). Financial inclusion and economic development in Africa. European Journal of Business Management and Research, 7(2), 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2024). Financial inclusion: Financial inclusion is a key enabler to reducing poverty and boosting prosperity. World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- World Bank Group. (2021). The global findex database 2021: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the age of COVID-19. World Bank Group. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Yadav, R. S., & Reddy, K. S. (2021). Banking or under-banking: Spatial role of financial inclusion and exclusion. International Journal of Rural Management, 19(1), 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).