Abstract

With the continuous deepening of the financialisation level of Chinese enterprises, the output of capital-deepening enterprises is inevitably affected. Taking A-share listed companies on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges in China from 2007 to 2021 as the research sample, this paper explores the impact of enterprise financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises and its underlying mechanism. The research findings indicate that enterprise financialisation negatively influences the output of capital-deepening enterprises. Through the analysis of the theoretical model in this paper, it is found that the mechanism leading to this economic effect is that enterprise financialisation significantly inhibits capital deepening. The heterogeneity analysis reveals no significant differences in the negative impact of enterprise financialisation on capital output, deepening enterprises across different aspects such as ownership, region and industry. This paper provides theoretical support for curbing the excessive financialisation of capital-deepening enterprises. It is conducive to the long-term and sustainable development of capital-deepening enterprises and offers a new perspective for researching the economic effects and internal mechanisms of enterprise financialisation.

1. Introduction

Financialisation represents a shift in the mode of accumulation wherein profits are increasingly generated through financial channels rather than through trade and commodity production (Krippner, 2011). This shift originates in the overall slowdown of economic growth and stagnation of the real economy, leading countries to rely more on financial growth to expand their monetary capital (Aalbers, 2017). The global economic order post the 2008 financial and economic crisis is expanding in an unstable, short-sighted and unequal manner, mainly due to the continuous increase in the influence of financial markets (Tellalbasi & Kaya, 2013). This raises the question of whether the actors in the financial markets will benefit while the real economy does not (Sweezy, 1995). And does excessive financialisation augment risks and impede the sustainable development of enterprises (Fu et al., 2024)?

From a macro perspective, the growth of financial investment can lead to a decrease in the share of real investment (Despain, 2015; Ricardo, 2017), resulting in high-income countries experiencing “investment-free growth” and “slowed accumulation,” leading to a decline in productivity and value-added growth (Tomaskovic-Devey et al., 2015; Pariboni et al., 2020). At a micro-level, corporate financialisation can explain this phenomenon. One significant driving factor of corporate financialisation is the ownership of listed companies. Since the 1980s, many enterprises have been led by CEOs with financial or legal backgrounds (Fligstein, 1990). The shareholder value ideology prioritises long-term profitability or corporate survival in leveraged buyouts, stock buybacks and mergers. Many financialised enterprises achieve faster and easier investment returns in the short term and can influence stock prices or rating agencies for a while. However, the effective return on capital rarely demonstrates structural growth (Aalbers, 2017; Davanzati et al., 2019). By increasing payments to the financial market in the form of interest, dividends and stock buybacks, enterprises may reduce internal funds and shorten planning horizons, thereby hindering real investment and expanding financial assets and liabilities (Włodzimierz, 2018; Rabinovich & Reddy, 2024). The asset–liability structure of the firm mirrors this scenario. A firm may issue or take on higher levels of credit, augment the quantity of short-term assets in its portfolio or pivot towards long-term investments. All of these actions can result in non-fixed assets accounting for a greater proportion of total assets than fixed assets (Klinge et al., 2021). Furthermore, firms may boost their leverage ratios by substituting debt for equity. This practice can further stimulate the growth of financial instruments, particularly during periods of low interest rates and in certain countries (Guttmann, 2017).

Financialisation, serving as an indicator reflecting the dynamics within the financial domain, has not yet reached a consensus on a unified definition (Tellalbasi & Kaya, 2013). Financialisation stems from the substantial influx of capital from developed countries into developing countries, followed by a counter-flow that helps to offset the current account deficits in developed countries. This phenomenon has reconfigured the relationship between developed and developing countries. It has brought about a qualitative transformation in finance’s role in the economy and fortified the linkages between non-financial and financial sectors (Harvey, 2005). Amidst the relaxation of financial sector regulations, the proliferation of novel financial products, the liberalisation of international capital flows and the heightened volatility in foreign exchange markets, financialisation is construed as a process characterised by the continuous progression of a market-oriented financial system. In this process, institutional investors emerge as the primary players in financial markets, and the operational philosophies of both financial and non-financial enterprises shift towards maximising shareholder interests (Stockhammer, 2008). Under this context, the financial assets of non-financial enterprises have witnessed growth, and financial investment opportunities have been augmented. Institutional investors tend to prioritise short-term profit maximisation over long-term investment. In light of this, Orhangazi (2008) defines financialisation as the process through which non-financial enterprises become involved in financial activities. Non-financial enterprises adapt their management strategies to attain business objectives and attract investors. Consequently, this has led to an increasing influence of financial institutions in both private and social spheres (Bryan & Raffertty, 2006). Overall, financialisation has enhanced the functions of financial markets, market participants and financial institutions within both domestic and international economic landscapes.

Regarding the causes of corporate financialisation, two theories can be employed for explanation (B. Huang et al., 2022). The first is Keynes’ liquidity theory. Firms hold cash driven by precautionary, speculative and transaction motives. Financial assets consist of both cash and non-cash assets, and most non-cash assets can be conveniently converted into cash. Thus, when the quantity of financial assets a firm holds exceeds that of physical assets, its liquidity is enhanced. The firm can make more flexible decisions in the face of financial constraints. The second is Jensen’s agency theory. When a firm holds a substantial amount of financial assets, the management is more prone to seeking personal interests and leveraging these financial assets to pursue short-term high performance. Furthermore, existing literature mainly explores the influencing factors of corporate financialisation from two dimensions: the macro-policy environment and micro-firm characteristics. From the perspective of the macro-policy environment, economic policy uncertainty (Si et al., 2022), regional financial agglomeration (L. Chen & Zhang, 2023), low-carbon city pilot policies (Liu & Lv, 2023), government subsidies (Qi et al., 2021), value-added tax reform (Tang et al., 2024) and the pilot reform of state-owned capital investment and operation companies all exert significant influences on corporate financialisation (M. Guo et al., 2025). From the perspective of micro-firm characteristics, mandatory internal control audits (Q. Chen & Chen, 2024), executive shareholdings (Y. Zhang et al., 2023), the proportion of female directors (Y. Huang & Li, 2024), the academic backgrounds of executives (Li & Hua, 2025) and the application of big data technology (Gao et al., 2023) can mitigate corporate financialisation. Conversely, managerial myopia and social responsibility can drive corporate financialisation (Y. Zhang et al., 2023; Su & Lu, 2023).

Capital deepening augments physical capital input per unit of output or labour. It is crucial to realise economic growth (Solow, 1956; Kumar & Russell, 2002). Acemoglu and Guerrieri (2008) posited that the interplay between variations in the proportion of factor inputs across different production sectors and capital deepening gives rise to unbalanced economic growth. Che (2010) further contended that the industrial structural changes engendered by capital deepening incur frictional costs. These costs, in turn, circumscribe the scope of industrial structural adjustments, resulting in subpar overall economic performance. Concurrently, more skilled labour may be reallocated to sectors with a relatively lower capital share (K. Guo et al., 2022). When exploring the economic implications of capital deepening at the national level, it has been found that it contributed to a more rapid growth in agricultural labour productivity in the United States from the 1940s to the 1980s (C. Chen, 2019). Additionally, capital deepening was identified as a significant contributing factor to gender discrimination in the manufacturing sector of Turkey during the 1990s (Özge, 2015). Moreover, capital deepening has led to a notable escalation in housing prices in Chinese cities (K. Chen et al., 2020).

Generally speaking, most studies on capital deepening discuss economic growth at the macro-level while paying little attention to micro-level capital-deepening enterprises. Capital accumulation serves as the cornerstone for surviving and developing capital-deepening enterprises. Integrating the abovementioned analysis, it can be seen that corporate financialisation will reduce enterprises’ share of real investment, weaken their ability to accumulate capital and inhibit the degree of their capital deepening. Therefore, compared with non-capital-deepening enterprises, corporate financialisation may have a particularly pronounced impact on the output of capital-deepening enterprises. For this reason, this paper is based on capital-deepening enterprises, aiming to explore whether the shift between financial investment and real investment by capital-deepening enterprises will delay or even undermine their capital-deepening process and have an obvious disruptive effect on their output.

This paper initially constructs a two-sector economic model. It is assumed that corporate financialisation can influence the reallocation of capital across sectors and give rise to frictional costs. Through mathematical deductions, this paper deliberates on the impacts of frictional costs on the capital deepening and output of corporations. The findings suggest that the frictional costs induced by corporate financialisation can impede capital deepening and exert a negative influence on the output of capital-deepening enterprises. Based on this, the theoretical mechanisms are analysed from three dimensions: the illusion of corporate marginal capital returns, the deviation of corporate comparative advantages and corporate creative destruction. Secondly, corresponding empirical tests are carried out using A-share listed companies with capital deepening on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges in China from 2007 to 2021 as the sample. Referencing previous research (Demir, 2009b; Y. Zhao & Su, 2022; Che, 2010), corporate financialisation is measured by the ratio of financial assets to total assets, and corporate capital deepening is represented by the ratio of net fixed assets to the number of corporate employees. These two variables are the main explanatory variables, while the total output of capital-deepening enterprises is the explained variable. The benchmark regression results indicate that corporate financialisation has a negative impact on the output of capital-deepening enterprises. To address potential endogeneity issues, this paper employs the instrumental variable approach and the system Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) to tackle the problem of reverse causality. A series of robustness tests is conducted to further validate the robustness of the benchmark regression results, including replacing the explained variable, the explanatory variable and placebo tests. Finally, this paper utilises the mediation effect model. Using the total sample, sub-samples of enterprises with high total asset turnover ratios, sub-samples of enterprises with low total asset turnover ratios, sub-samples of enterprises with high profit margins and sub-samples of enterprises with low profit margins, the theoretical mechanisms proposed in this paper are verified from five dimensions. The results demonstrate that corporate financialisation negatively affects the output of capital-deepening enterprises by inhibiting capital deepening. In addition, this paper explores whether there are differences in the relationship between corporate financialisation and the output of capital-deepening enterprises across different aspects such as enterprise ownership, region and industry. The results suggest that the negative impact of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises does not exhibit significant variations at ownership, region and industry levels.

In contrast to the existing literature, this paper makes main contributions in three aspects. Firstly, it extends the theoretical dimension of the research on the economic effects of corporate financialisation. Prevailing research has predominantly concentrated on the negative economic consequences of corporate financialisation. Existing studies have shown that corporate financialisation significantly curtails investment in the real sector (Orhangazi, 2008; Demir, 2009a; Ricardo & Sérgio, 2017; Davis, 2017). Given the influence of risks such as interest rates, exchange rates and policy regulations, the returns of financial products are fraught with uncertainty, and the likelihood of incurring losses is relatively high. These risks are likely to spill over into the real economy. Specifically, the higher the level of corporate financialisation, the greater the financial risks borne by the firm and the more pronounced the adverse impact on corporate behaviour and market performance (Ivanov, 2019; Janowski, 2015; Matt et al., 2015; Q. Zhao et al., 2025). Firms with substantial financial assets may send negative signals to creditors, compelling capital providers to demand a higher risk premium, thereby escalating the firm’s financing costs (X. Chen et al., 2024). Even more alarmingly, corporate financialisation can heighten the risks of bankruptcy and substantial stock price collapses (Matzler et al., 2018; Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010; Admati, 2017; Rachinger et al., 2018). Excessive corporate financialisation or financial deepening at the macroeconomic level will ultimately erode innovation capabilities and long-term growth potential and undermine the operational performance of real-sector enterprises (Orhangazi, 2008; Arcand et al., 2015; B. Lee et al., 2020; J. Huang et al., 2021; C. Zhang et al., 2025). It is noteworthy that the negative economic effects triggered by corporate financialisation seemingly all exert an influence on firm output. Nevertheless, no corresponding theoretical models have been developed to explore this phenomenon. This paper addresses this research gap by constructing a theoretical analysis model of the impact of capital deepening on enterprise output.

Secondly, much of the existing literature places significant emphasis on research regarding the causes of corporate financialisation. For instance, factors such as the profit crisis in the real economy (Krippner, 2005; Orhangazi, 2006), the evolution of corporate governance models and shareholder value (Lazonick, 2010; B. Huang et al., 2022), class exploitation (Hudson, 2010; Stockhammer, 2012), the motivation for capital reserve (Z. Yang et al., 2017) and the motivation for capital arbitrage (H. J. Wang et al., 2016) have been extensively explored. Nevertheless, the mechanism through which corporate financialisation undermines capital accumulation and causes enterprises to deviate from productive activities has not been thoroughly investigated (Tellalbasi & Kaya, 2013). This paper demonstrates that corporate financialisation exerts a restraining effect on capital deepening, thereby negatively influencing the output of enterprises engaged in capital deepening. Based on this, this paper delves into this mechanism from three dimensions: the illusion of the marginal return on enterprise capital, the deviation of enterprise comparative advantage and the creative destruction within enterprises. The objective is to present a novel analytical framework for understanding the mechanism underlying corporate financialisation, thus contributing to the academic discourse in this field.

Finally, most extant literature explores the factors influencing capital deepening from a macro-level perspective. For example, Aghion and Howitt (1992) posited that technological progress is crucial in propelling capital deepening. Blanchard and Daniel (2013) established that fiscal and monetary policies can influence corporate investment decisions through tax incentives, interest rate adjustments and liquidity provisions. This, in turn, impacts capital accumulation and directly affects capital deepening. Additionally, certain studies (Acemoglu & Autor, 2011) have indicated that enhancing educational attainment and human capital can augment the efficiency of labour–capital integration, thereby constituting one of the decisive factors for capital deepening. Distinct from this body of literature, this paper centres on investigating the influence of corporate financialisation on corporate capital deepening at the micro-level. It offers a novel analytical perspective for extending the analytical scope of such literature from the macro-level to the micro-level.

2. Theoretical Model

To investigate the relationship between corporate financialisation and the output of capital-deepening enterprises, this paper draws on the two-sector economic model proposed by Acemoglu and Guerrieri (2008). In this model, final goods are produced from intermediate goods in both sectors, and the elasticity of substitution of intermediate goods in both sectors is :

where represents the total output of the final product, , respectively, represent the output of intermediate products of sector 1 and sector 2; , respectively, represent the contribution rates of sector 1 and sector 2 to the total output, ; represents the period. There is only one producer in each sector, and the production function for all sectors is the C-D production function and uses only two factors of production, capital and labour .

To simplify the analysis, it is assumed that the two sectors have the same level of technology . represents the capital contribution rate of sector , and represents the labour contribution rate of sector , while sector 1 is more capital-intensive than sector 2, i.e., .

Let the final product price be ; then, the product price in both sectors can be expressed as

Assuming that labour is free to move within the two sectors in a given period, labour market clearing implies the following:

represents the labour supply at the moment , which is exogenously given.

The reallocation of capital among departments can lead to friction costs, including opportunity costs, agency costs and corresponding capital allocation costs arising from the transfer of capital from the physical investment field to the financial investment field. Opportunity cost refers to the potential income lost when an enterprise invests its capital in financial assets instead of real assets due to the substitution effect of financial asset investment on real asset investment (Tori & Onaran, 2018; Xu & Xuan, 2021). Agency cost arises from managers’ tendency to over-invest in financial assets driven by profit-seeking motives, which undermines long-term interests and sacrifices the long-term value of enterprise owners (Fu et al., 2024).

Suppose is a historical value of the capital ratio of the two sectors. When the capital ratio of the two sectors is different from due to corporate financialisation, there will be friction costs caused by corporate financialisation, .

The capital market clearing need to be met:

where represents the total capital stock at the period , and .

Assumptions are as follows:

where , and there is a positive friction cost. Given the capital stock in each period, output maximisation implies the following:

(1), (2), (3) and (4).

Solving Equation (5) implies that the marginal output of capital and labour is equal in both sectors.

Sector 1 is the capital-deepening sector, and its capital and labour shares are as follows:

Then, Equations (6) and (7) imply

In equilibrium, to examine the effect of corporate financialisation on capital deepening, let

From Equation (10), when , , it shows that corporate financialisation inhibits capital deepening; that is, as the degree of corporate financialisation deepens, the process of capital deepening will slow down. Next, let us discuss the impact of capital deepening on output.

Let Equation (12) be a function of the derivation:

Let Equation (13) be a function of the derivation:

Among them

From Equations (11)–(14), it can be seen that labour will flow to capital-deepening sectors, and the output of these sectors will increase with capital deepening. However, the output of capital-deepening sectors is negatively affected by the inhibitory influence of corporate financialisation on capital deepening.

Specifically, the inhibitory effect of corporate financialisation on capital deepening can be attributed to three reasons: ① illusion of marginal return on financial capital. In the initial stage of shifting from physical to financial investment, the marginal return on financial capital is greater than that of fixed capital, leading to the illusion of high returns from financial capital. However, as financial capital input increases and fixed capital accumulation decreases, the marginal return on financial capital gradually decreases while the marginal return on fixed capital increases. In this scenario, capital-deepening enterprises become path dependent on financial investment and face high friction costs when transitioning back to physical investment, thereby inhibiting the process of capital deepening. ② Deviation from the comparative advantage of enterprises. According to the new structural economics theory (Lin, 2011), enterprises have their factor endowment structure. When enterprise development aligns with its factor endowment structure, the comparative advantage of the enterprise is realised; otherwise, it deviates from the comparative advantage. Capital-deepening enterprises’ factor endowment structure requires continuous accumulation of fixed capital. However, corporate financialisation can cause capital-deepening enterprises to deviate from their factor endowment structure, deviating from their comparative advantage and optimal development path, further inhibiting capital deepening. ③ Weakening of the innovative capacity for creative destruction by enterprises. Compared to other enterprises, capital-deepening enterprises have a stronger capacity for creative destruction, which is the basis for long-term accumulation of fixed capital. Capital-deepening enterprises do not possess strong financial innovation capabilities and cannot promote the development of the financial market. Instead, corporate financialisation only weakens their capacity for creative destruction in the physical domain, reduces their long-term accumulation of fixed capital and inhibits enterprise capital deepening.

Based on the above analysis, the illusion of marginal return on financial capital, deviation from comparative advantage of enterprises and weakening of the capacity for creative destruction are all factors that lead to the continuous friction costs for capital-deepening enterprises in the process of financialisation, inhibiting their capital deepening process. This is manifested by the continuous transfer of capital from capital-deepening enterprises to the financial market, leading to a shortfall in physical investment in the short term and potentially causing stagnation and contraction of physical investment in the long term. The foundation of fixed capital accumulation is weakened, the accumulation path is interrupted and ultimately, the process of enterprise capital deepening is obstructed, leading to the lack of growth in output for capital-deepening enterprises. Based on the above analysis, the following propositions are proposed in this article.

Proposition 1.

Corporate financialisation has a negative impact on the output of capital-deepening enterprises.

Proposition 2.

Corporate financialisation negatively affects the output of capital-deepening enterprises by inhibiting capital deepening.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Source

This paper utilised data from all A-share listed companies on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 2007 to 2021 as the research sample. The sample was selected based on the following criteria: ① Exclusion of listed companies in the financial, insurance and real estate industries; ② exclusion of ST and ST* listed companies with abnormal financial conditions to mitigate the impact of financial information quality and outliers on empirical results; ③ exclusion of non-capital-deepening listed companies1 and ④ exclusion of samples with missing key data. This resulted in a panel data sample comprising a total of 5111 observation values. The fundamental data for this paper primarily originated from the CSMAR database, and a 1% two-tailed trimming was applied to continuous variables at the enterprise level.

3.2. Model

This paper developed Equation (15) to investigate the influence of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises (Proposition 1).

If Proposition 1 holds, it is expected that , the regression coefficient of , is significantly less than 0, indicating that corporate financialisation has a negative impact on the output of capital-deepening enterprises. In Equation (15), the subscript represents the enterprise, and represents the year. is the natural logarithm of the output of capital-deepening enterprises; is the financialisation degree index of the capital-deepening enterprises; is the control variable; is the time fixed effect used to control the common shocks of unobservable time factors on enterprises; represents the enterprise fixed effect used to control the differences at the enterprise level; is the random error term.

3.3. Variable Definition

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

The natural logarithm of output generated by capital-deepening enterprises () is the dependent variable in Equation (15). Enterprise output refers to the monetary value of products produced by the enterprise in a certain period, and it is a statistical quantity therefore, drawing on the production method of accounting for industrial output value, the current period of total operating income (market value of products sold) plus the end-of-period inventory value is used to measure the output of capital-deepening enterprises. The specific calculation formula is , and the output of capital-deepening enterprises is adjusted for inflation using the 2007 base period.

3.3.2. Core Explanatory Variable

The corporate financialisation index () is the core explanatory variable in Equation (15). Drawing on Demir (2009b) and Y. Zhao and Su (2022), the corporate financialisation () is represented by the ratio of financial assets held by the enterprise (i.e., the proportion of financial assets to total assets). Financial assets include cash, trading financial assets, net amount of available-for-sale financial assets, net amount of held-to-maturity investments, net amount of investment properties, receivables for dividends, receivables for interest and long-term equity investments. It should be noted that as the proportion of profits generated by financial activities increases in proportion to entity profits, most of the funds that entities invest in real estate are used for speculation rather than production operations. According to the definition of China’s “Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises (ASBE) No. 3—Investment Real Estate”, investment real estate refers to real estate held for earning rentals, capital appreciation or both. It is a better measure of the real estate investment of an entity enterprise; therefore, this paper includes the net investment property item in the measurement process of corporate financialisation. Long-term equity investment may be a strategic behaviour that serves the enterprise’s long-term development. Unlike general financial investment, which is to obtain short-term investment returns, it improves the efficiency of capital utilisation, so this paper will exclude the long-term equity investment from and use to measure corporate financialisation and use it as a robustness test.

3.3.3. Control Variables

In order to minimise the errors caused by omission variables, drawing on literature such as Shi and Zhang (2018), C. Zhang and Zheng (2020) and Sun and Tian (2021), this paper’s control variables cover financial characteristics, corporate governance and other factors affecting corporate financialisation, specifically including the following:

is the ratio of the net operating cash flow to the book value of total assets. This ratio can effectively reflect an enterprise’s financing constraints and embody the enterprise’s capacity to manage financial investment risks. An enterprise’s investment exhibits a high degree of sensitivity to cash flow, and the cash flow is restricted by the amount of cash held by the enterprise. When an enterprise generates ample net cash flow from its operating activities, investing additional financial assets for a liquidity reserve is unnecessary. Consequently, the enterprise can allocate more funds to operating assets.

is the ratio of fixed assets to total assets. The ratio influences corporate financialisation primarily through capital liquidity and profit model disparities. When this ratio is relatively high, capital becomes locked within physical assets. As a result, enterprises rely more on physical operations, and the degree of financialisation remains relatively low. Conversely, when this ratio is relatively low, the flexibility of enterprise capital utilisation is enhanced. Under such circumstances, enterprises tend to be more inclined to conduct financial activities such as securities investment and derivatives trading. This leads to a shift from a production-oriented model to a finance-oriented one, thereby raising the level of financialisation.

is the growth rate of operating income. The ratio serves as a key indicator for assessing a company’s core business growth potential, reflecting its market performance and operational efficiency within the real economy. Corporate financialisation, characterised by the reallocation of capital from productive to financial investments, may result in diminished resources allocated to the core business, thereby hindering the growth of operating income.

is the ratio of market value to total assets. It reflects the proportion of a company’s market value relative to its total assets. While financialisation may temporarily increase enterprises’ Tobin ratios, excessive reliance on financial activities can undermine real investment in the long run, ultimately leading to a decline in the ratio.

The inset shows the ratio of net intangible assets to total assets. This ratio generally indicates a company’s level of technological innovation, brand value and knowledge-based capital. A higher proportion of intangible assets may suggest that the company places greater emphasis on technological advancement and long-term competitive positioning, as opposed to short-term financial returns.

is the ratio of profit from the main business to net income from the main business. The ratio reflects the profitability of a company’s core operations. A high profit margin typically indicates strong competitiveness in the primary business activities, whereas a low profit margin may signal weak growth prospects or insufficient earnings generation. A high profit margin tends to discourage excessive financialisation. It encourages a focus on the real economy, while a low profit margin may lead to increased financial activities to compensate for the shortfall in operational earnings.

4. Empirical Findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

The descriptive statistical results of the variables are shown in Table 1. The natural logarithm of the output of capital-deepening enterprises has a mean (median) of 21.0680 (21.0227). The mean (median) of the financialisation degree of capital-deepening enterprises is 0.2030 (0.1567), with a maximum value of 1.9144. The mean (median) of , excluding long-term equity investment, is 0.1560 (0.1180), with a maximum value of 2.0333, indicating that most capital-deepening enterprises hold financial assets and the proportion of financial assets held in total assets is relatively high. The results of the remaining control variables are not individually explained. The correlation coefficient matrix of the main variables is shown in Table 2. The Spearman correlation coefficients between and , are −0.1733, −0.1722, and the Pearson correlation coefficients are −0.2601, −0.2646, both passing the statistical test at the 1% level, thereby providing initial support for proposition 1 as proposed above. However, further robust evidence must be obtained through multiple regression analysis while controlling for other factors.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 2.

Correlation analysis of the main variables.

4.2. Baseline Regression Results

Table 3 presents the baseline regression results using model Equation (15). To test the robustness of the findings, a stepwise regression was conducted following the approach of Su and Liu (2021). Column (1) displays the regression results without control variables or time fixed effects. The regression coefficient of corporate financialisation () is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating a substantial negative impact of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises. Column (2) presents the results, including time fixed effect but without control variables, where the regression coefficient of corporate financialisation () remains significantly negative. Column (3) provides the results including control variables but without time fixed effect, while column (4) reports the results including both control variables and time fixed effect. In both columns, the regression coefficients of corporate financialisation () are significantly negative, supporting Proposition 1. This is because once capital-deepening enterprises invest in financial assets, they are inclined to hold more financial assets if they generate higher profits than non-financial investments. However, holding an excessive amount of financial assets can jeopardise the competitive advantage of the core business of the enterprises, reduce their growth potential and increase the operational risk of the enterprises (Fu et al., 2024). As a result, corporate financialisation usually has a negative impact on the output of capital-deepening enterprises.

Table 3.

Impact of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises.

4.3. Endogenous Processing

This paper utilises instrumental variables and system GMM methods to tackle endogeneity issues. The specific analysis is as follows:

(1) Instrumental variable regression. ① Construction of the deleveraging policy instrumental variable regression. The corporate financialisation has led to an increasing reliance on financial leverage tools such as loans, financing and bonds in their operational and investment decisions, neglecting the accumulation and effective utilisation of internal funds and reducing investment in research and human resources (Orhangazi, 2008; Fiebiger, 2016; Davis, 2017). These investments are the key and core of capital deepening, and reducing these investments will have a negative impact on the output of capital-deepening enterprises. The 2015 Central Economic Work Conference proposed the task of “deleveraging” and adopted the “five controls and three increases” measures. Over-indebted enterprises demonstrate a significant sensitivity to deleveraging policies, when such policies target leveraged funding sources, these enterprises tend to scale back their financial asset holdings. Capital-deepening enterprises require substantial upfront investment to support their production and operational activities, in the context of limited internal capital, firms typically use debt financing to fund their investment, elevating their leverage ratios. Consequently, deleveraging policies can influence the financialisation behaviour of capital-deepening enterprises and exert an exogenous impact on their output. The paper draws on J. H. Yang and Chen (2023) to construct a deleveraging policy instrumental variable. The first-stage regression equation is

The variable represents the product of the processing group dummy variable and the time dummy variable , which serves as an instrumental variable. The value of is 1 when the enterprise is impacted by the deleveraging policy and 0 otherwise. Raghuram and Zingales (1995) argued that a debt-to-asset ratio exceeding 70% to 80% in many industries is generally considered a high-risk threshold, as rising interest expenses may significantly reduce profitability and constrain enterprise investment capabilities. Enterprises with leverage greater than 75% are treated as the treatment group, ; enterprises with leverage less than or equal to 75% are treated as the control group, . Post-2015, the . Pre-2015, the .

Choosing 75% as the threshold ensures that the treatment group includes a sufficient number of highly leveraged firms while preserving the representativeness of the control group.

Columns (1) and (2) of Table 4 present the regression analysis results. The under-identification test statistics (, ) and weak instrument test statistics () indicate the absence of under-identification or weak instrument issues. The first stage results in columns (1) and (2) of Table 4 show a negative relationship between the instrumental variables and corporate financialisation, in line with expectations, suggesting that deleveraging policies reduce the level of financialisation in highly leveraged capital-deepening enterprises. The second stage results confirm corporate financialisation’s negative impact on capital-deepening enterprises’ output, consistent with the baseline regression results.

Table 4.

Endogenous processing.

② Construct an instrumental variable regression of the mean financialisation degree of other capital-deepening enterprises in the same industry. Drawing on Sun and Tian (2021), this paper selects the mean value of the degree of financialisation of the remaining capital-deepening enterprises in the same industry, excluding this capital-deepening enterprise, as an instrumental variable for the financialisation degree of the capital-deepening enterprises (). The results of the first and second-stage regressions using instrumental variables are presented in columns (3) and (4) of Table 4. The instrumental variable analysis does not suffer from underidentification and weak instrumental variables, and the coefficient of is negative, indicating that the finding that corporate financialisation has a negative effect on the output of capital-deepening enterprises is reliable.

(2) System GMM. This paper further solves the possible endogeneity issue using the system GMM method. Column (5) of Table 4 shows the results of the system GMM regression. The p-value corresponding to the test is 0.0000, and the p-value corresponding to the test is 0.4850. The p-value corresponding to the tests is 0.1800, which suggests that there is a dynamic relationship in the designed model, that there is a first-order autocorrelation in the difference equations of the perturbation terms but not a second-order autocorrelation and that the instrumental variables in the model are subjected to the original hypothesis of exogeneity. Under the system GMM model, the regression coefficients of are negative, and the regression results support the baseline regression conclusions.

4.4. Robustness Check

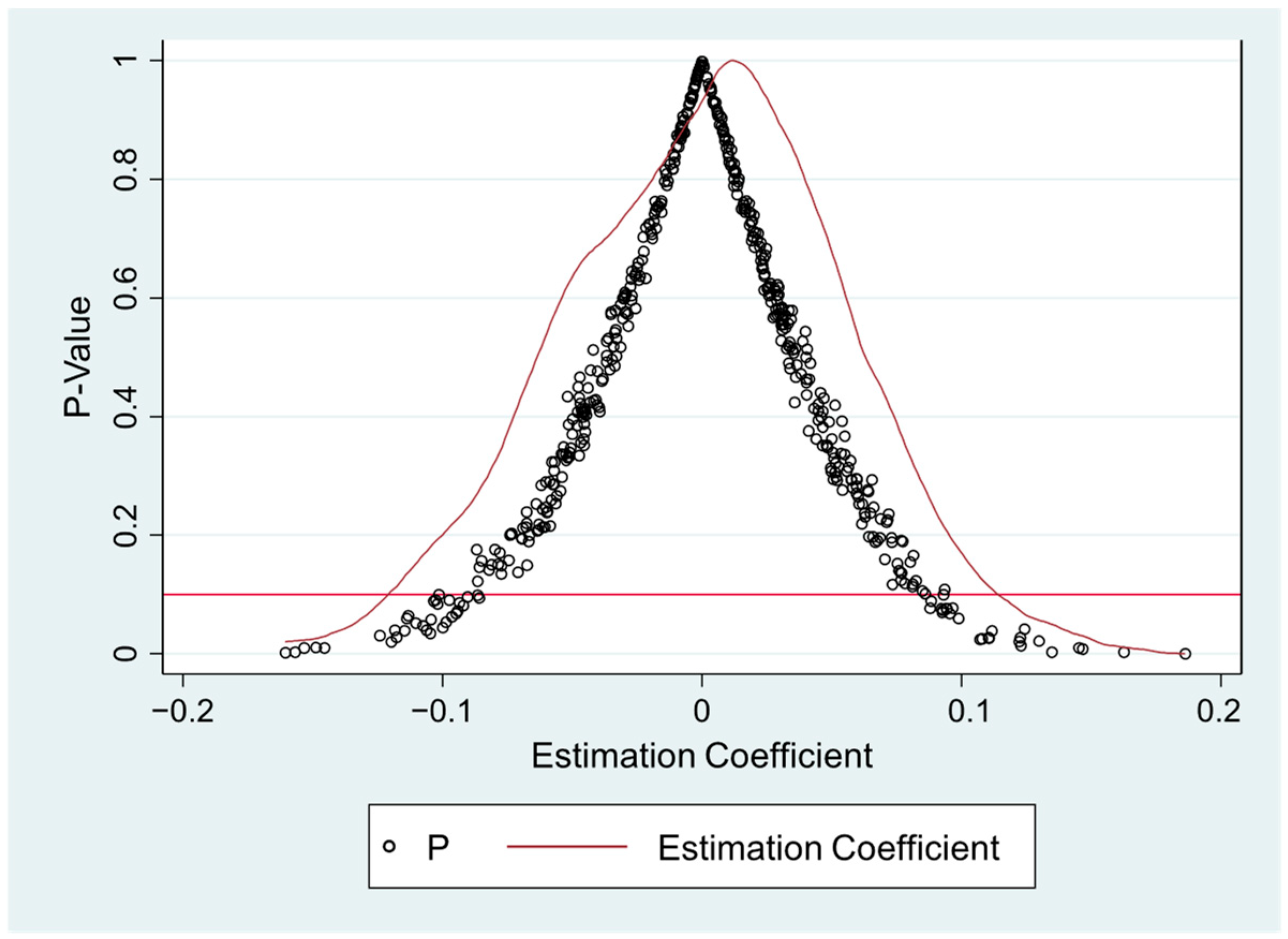

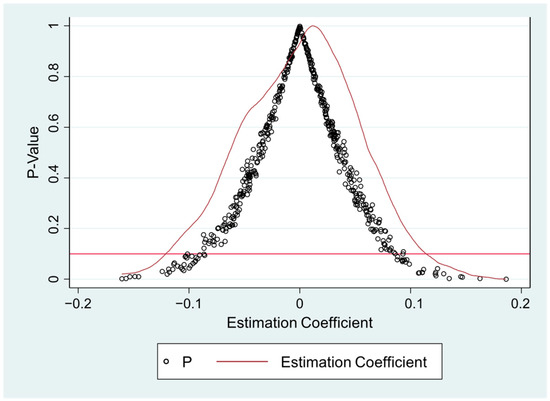

To ensure the reliability of the findings as much as possible, this paper also conducts the following robustness tests: ① Replacement of the dependent variable. The total operating income of listed companies () replaces the output () to regress the baseline model. ② Replacement of the core explanatory variable. Regarding the current controversy over whether long-term equity investment should be included in the category of financial assets, this paper further examines the impact of corporate financialisation excluding long-term equity investment on the output of capital-deepening enterprises, specifically by replacing the core explanatory variable from with and re-regressing the baseline model. The above robustness results are shown in Table 5. After the above treatment, replacing with and replacing with , all regression coefficients are still significantly negative, indicating that the baseline regression results are more robust. ③ Placebo test. Drawing on J. H. Yang and Chen (2023), this paper designs a placebo test to assess whether factors unrelated to corporate financialisation reduce the output of capital-deepening enterprises. The specific approach involves random matching of core explanatory variables with the dependent variables, namely the degree of financialisation of capital-deepening enterprises and the output of enterprises. This paper conducts 500 repetitions of the regression and creates kernel density plots for the regression coefficients of these 500 random regressions and scatter plots of the p-value coefficients. The results of the placebo test are depicted in Figure 1. It is evident that the estimated coefficients are generally normally distributed, with a mean close to 0, and most of the estimated coefficients have p-values above 0.1. This suggests a significant disparity between the randomised estimated coefficients and the baseline regression coefficient, with most of the estimates being insignificant. The conclusion that corporate financialisation reduces the output of capital-deepening enterprises is relatively stable, and regression errors due to some random factors are largely excluded.

Table 5.

Robustness test results for (1) and (2).

Figure 1.

Estimated coefficient and p-value of regression after random matching.

5. Further Analysis

5.1. Theoretical Mechanism Analysis of the Impact of Corporate Financialisation on the Output of Capital-Deepening Enterprises

Capital-deepening enterprises are mainly concentrated in industries such as energy, heavy chemical engineering, electronics and electrical engineering. The characteristics of these industries determine that the basis for the further development and capital deepening of such enterprises is sustained and sound investment in fixed assets and technological progress. However, the “departure from the real economy” of corporate financialisation may inhibit the capital deepening of enterprises, thereby weakening the foundation for the development of capital-deepening enterprises and exerting a negative impact on their output. To verify the theoretical mechanism that enterprise financialisation suppresses capital deepening and thus negatively impacts the output of capital-deepening enterprises (Proposition 2), this paper draws on Baron and Kenny’s (1986) research. It uses the mediating effect model for empirical analysis, capital deepening () concerning Che (2010) and using the ratio of net fixed assets to the number of enterprise employees as a measure. The mediating effect model can be described by the preceding Equation (15) and the following Equations (17) and (18).

According to the mediation effect test procedure proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986), when , and are significant, is significant, indicating partial mediation, while is not significant, indicating complete mediation. Since the previous analysis has shown that is significant, this section focuses on the significance of , and . Table 6 tests the relationship between corporate financialisation, capital deepening and the output of capital-deepening enterprises. The results show that regardless of whether the core explanatory variables are or , , and are all significant, indicating that capital deepening plays a partial mediating role in the process of the negative impact of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises. This confirms the reliability of Proposition 2.

Table 6.

Corporate financialisation, capital deepening and enterprises’ output.

Total asset turnover and profit margin are key financial indicators used to assess a company’s operational efficiency and profitability and thus carry significant analytical value. A high total asset turnover indicates efficient utilisation of a company’s assets, which may facilitate its capital-deepening process. Conversely, a low total asset turnover suggests underutilisation of assets or operational inefficiencies, posing a substantial constraint on capital deepening. Companies with higher profit margins generally benefit from greater retained earnings and stronger cash flow, which can serve as a reliable internal source of financing for capital deepening. On the other hand, a lower profit margin limits internal capital accumulation, making it challenging for a company to support the substantial initial investment required for capital deepening. To thoroughly examine the mechanism through which corporate financialisation influences the output of capital-deepening enterprises, this paper categorises the full sample into four sub-samples: enterprises with a high total asset turnover rate, enterprises with a low total asset turnover rate, enterprises with a high profit margin and enterprises with a low profit margin2. The mediation effect model is then applied to these four sub-samples to further investigate whether corporate financialisation negatively affects the output of capital-deepening enterprises by suppressing capital deepening. Table 7 and Table 8 present the results of the relationships among enterprise financialisation, capital deepening and output within these sub-samples.

Table 7.

Corporate financialisation, capital deepening and output in enterprises with high (low) total asset turnover ratios.

Table 8.

Corporate financialisation, capital deepening and output in enterprises with high (low) profit margin ratio.

It can be seen from Table 7 and Table 8 that in the sub-samples of high total asset turnover rate, low total asset turnover rate and high profit margin, regardless of whether the core explanatory variables are or , , and are all significant, indicating that capital deepening plays a partial mediating role in the process of the negative impact of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises. In the sub-sample with low profit margin, regardless of whether the core explanatory variables are or , and are significant. At the same time, is not significant. It is demonstrated that capital deepening plays a fully mediating role in the negative impact of enterprise financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises.

Through comparative analysis, it is observed that during the process of financialisation, enterprises with high profit margin and low total asset turnover rate experience a more pronounced suppression of capital deepening. This phenomenon exerts a greater negative effect on the output of high-profit-margin enterprises and a relatively smaller negative effect on enterprises with low total asset turnover rate. The underlying reason is that highly profitable enterprises, driven by their strong earnings capacity, tend to allocate more capital to financial assets and reduce their investment in physical assets during financialisation, thereby intensifying the suppression of capital deepening. Given that these enterprises typically operate at higher output levels, the decline in real investment leads to more substantial output losses, resulting in a more significant negative impact on their overall performance. Enterprises characterised by a low total asset turnover rate, reflecting their relatively inefficient asset utilisation, tend to favour financial investments with high short-term returns.

Furthermore, given their typically smaller output base, the adverse effects of financialisation on capital deepening are more easily mitigated, resulting in a comparatively minor negative impact on output. Among the four sub-samples, enterprises with a high total asset turnover rate experience the most significant negative impact on output due to the dampening effect of financialisation on capital deepening, whereas enterprises with a low profit margin are subject to the least negative impact on output. The reason is that enterprises with a high total asset turnover ratio depend on capital deepening to sustain operational efficiency and output. When financialisation inhibits capital deepening, it leads to a significant decline in their production efficiency, and such efficiency losses exert the most negative impact on output. In contrast, enterprises with low profit margins exhibit weaker profitability and lower demand for capital deepening, resulting in a relatively minimal negative impact of financialisation on their output.

The aforementioned empirical analysis aligns with the analysis of the theoretical model. The empirical findings indicate that 1% increase in the degree of financialisation among capital-deepening enterprises is associated with a significant decline in both capital-deepening and output levels. This effect is particularly pronounced in enterprises with high total asset turnover rates.

5.2. Further Analysis Based on the Influence of Firm Ownership and Regional Heterogeneity

In order to investigate the heterogeneity of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises with different ownership, this paper divides the samples into two sub-samples: state-owned enterprises and non-state-owned enterprises. Regression analysis is then conducted on the benchmark model. The empirical results are presented in Table 9. Columns (1) and (3) report the regression results for the impact of corporate financialisation on the output of state-owned capital-deepening enterprises, while columns (2) and (4) present the regression results for the impact of corporate financialisation on the output of non-state-owned capital-deepening enterprises. Additionally, Table 9 provides significance tests for differences in the coefficient between subgroup samples. The findings indicate that corporate financialisation negatively affects both state-owned and non-state-owned capital-deepening enterprises, with no significant difference between them. There are two reasons why enterprises engage in financial investment. Firstly, financial investment can yield higher returns in the short term than real investment, allowing companies to quickly increase their profits by investing in financial assets. Secondly, when there is uncertainty surrounding physical investments, diversified financial investments can help mitigate systemic risks associated with single physical investments. Therefore, during prosperous capital markets and relatively relaxed financial supervision regulations, state-owned and non-state-owned capital-deepening enterprises opt for financial investments due to these reasons. However, this crowding-out effect from real investment by financial investment ultimately hampers the process of capital deepening and has a negative impact on output for both types of enterprises, regardless of ownership differences.

Table 9.

Corporate financialisation’s impact on capital-deepening enterprises’ output differs based on ownership.

The negative impact of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises does not vary by ownership, but is there any regional variation? The samples were divided into two sub-samples representing the eastern region and the central and western regions. Empirical tests were conducted separately for each sub-sample using the benchmark model, yielding the empirical results in Table 10. In Table 10, Columns (1) and (3) present the empirical findings regarding the influence of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises in the eastern region; columns (2) and (4) report the empirical results concerning the impact of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises in the central and western regions. Additionally, Table 8 provides significance tests for coefficient differences across the sub-samples. Both sub-samples show that the coefficient of corporate financialisation is negative, and there is no regional difference in the negative effect of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises.

Table 10.

The impact of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises differs based on region.

The inter-regional development in China exhibits significant imbalances, with the central and western regions facing challenges such as unfavourable geographical conditions, inadequate institutional environment and underdeveloped economies. Given the absence of favourable physical investment opportunities and the non-restrictive nature of financial investments based on geographical conditions (Peng et al., 2018), enterprises in the central and western regions are not inferior to their counterparts in the eastern regions when it comes to financial asset investment for capital-deepening purposes. Consequently, there is no regional disparity regarding the negative impact of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises.

5.3. Further Analysis Based on the Influence of Industry Heterogeneity

The manufacturing industry requires substantial investments in physical capital, such as factories and machinery. It is characterised by a relatively high capital-to-labour ratio and significant capital deepening. In contrast, service industries—retail, consulting and information technology—primarily provide intangible services and rely more heavily on human labour or digital tools. Consequently, the level of capital deepening in these service sectors is generally lower than in the manufacturing industry. To investigate whether the negative impact of financialisation on output varies between industries with differing levels of capital deepening, this paper divides the overall sample into two sub-samples—manufacturing and service industries—and conducts separate regression analyses. The empirical results are presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

The impact of corporate financialisation on the output of capital-deepening enterprises differs based on industry.

In Table 11, columns (1) and (3) present the regression outcomes examining the effect of enterprise financialisation on the output of capital-deepening manufacturing enterprises, whereas columns (2) and (4) display the corresponding results for capital-deepening service enterprises. Furthermore, Table 11 includes significance tests for coefficient differences across the sub-samples. The findings reveal that corporate financialisation negatively influences the output of capital-deepening enterprises in both the manufacturing and service industries, with no statistically significant difference between the two sectors. This absence of significant variation can be attributed to two primary factors: First, the mechanism through which financialisation inhibits capital deepening operates consistently across both industries; second, under the background of the industrial integration trend of manufacturing service-oriented and service industrialisation, the capital-deepening behaviour of enterprises is more influenced by the institutional factor of financialisation rather than determined by the industry characteristics.

Through theoretical model analysis, this paper demonstrates that corporate financialisation negatively affects the output of capital-deepening enterprises by inhibiting capital deepening. The empirical findings are highly consistent with the theoretical analysis. During the process of financialisation, capital-deepening enterprises are influenced by three key factors: the illusion of marginal return on financial capital, deviation from the comparative advantage of enterprises and weakening of the capacity for creative destruction. As a result, these enterprises tend to pursue short-term financial gains or engage in speculative activities, thereby neglecting physical investment and deviating from their core business operations. This behaviour reduces the long-term efficiency of capital utilisation and negatively impacts enterprise output. The observed trend is prevalent across capital-deepening enterprises of different ownership types, regions and industries, and the results remain consistent.

6. Conclusions and Insights

Based on the data of A-share listed companies in China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets from 2007 to 2021, this paper examines the relationship between corporate financialisation and the output of capital-deepening enterprises. The findings indicate that corporate financialisation negatively affects the output of such enterprises. Further analysis of the underlying theoretical mechanism reveals that corporate financialisation significantly inhibits capital deepening, adversely impacting enterprise output. Additionally, heterogeneity analysis suggests that this negative effect remains consistent across different ownership structures, regions and industries.

Accordingly, this paper makes the following policy recommendations:

- Avoiding the recurrence of “unconventional” easy monetary policies. “Unconventionally” easy monetary policy can lead to rising corporate debt, and the vulnerability created by repeated leverage can spread unevenly across enterprise sizes, exacerbating the damaging effects of corporate financialisation (Baines & Hager, 2021; Xu & Xuan, 2021). Monetary policy should be moderately prudent in times of economic stability to iron out the cyclicality of corporate financialisation. Financial institutions should direct more funds into the fixed asset investment and R&D activities of capital-deepening enterprises to increase their fixed capital accumulation.

- Ensuring that the market mechanism plays its full role and limiting the formation of a monopoly market structure. A monopoly market structure will increase the tendency of capital-deepening enterprises to make financial investments, and the competitive market structure formed by supply and demand can reduce the asymmetry of information, weaken the uncertainty of the game for capital-deepening enterprises to make real investments and reduce their willingness to make financial investments.

- Transforming the governance model and shareholder values of capital-deepening enterprises. The governance model of capital-deepening enterprises should be shifted from emphasising short-term capital appreciation to focusing on long-term growth, and the shareholder values of capital-deepening enterprises should be shifted from pursuing the maximisation of shareholder value to the maximisation of corporate profits. The awareness of financial risk control among managers of capital-deepening enterprises should be enhanced, and it should be emphasised that overallocation of financial assets will inhibit real investment, increase business risks and create a long-term trend of lowering enterprise output growth.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The definition of capital-deepening enterprises has not been clearly established thus far. However, considering the calculability of capital-deepening indicators, this paper adopts the average value of such indicators as a benchmark for measuring capital-deepening enterprises. Enterprises with capital-deepening indicators lower than the average value are classified as non-capital-deepening enterprises. The capital-deepening indicator, drawing on Che (2010), is the ratio of net fixed assets to the number of enterprise employees. |

| 2 | The classification criteria are defined as follows: Enterprises with high total asset turnover rates exceed the overall sample average, while those with low turnover rates fall below the sample average. Similarly, enterprises with high profit margins are characterised by margins above the sample average, whereas those with low profit margins exhibit margins below the sample average. |

References

- Aalbers, M. B. (2017). Corporate financialization. International Encyclopedia of Geography, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D., & Autor, D. (2011). Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings. Handbook of Labor Economics, 4, 1043–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D., & Guerrieri, V. (2008). Capital Deepening and Non-balanced Economic Growth. Journal of Political Economy, 116(3), 467–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admati, A. R. (2017). A skeptical view of financialized corporate governance. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(3), 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1992). A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction. Econometrica, 60(2), 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcand, J. L., Berkes, E., & Panizza, U. (2015). Too much finance? Journal of Economic Growth, 20, 105–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, J., & Hager, S. B. (2021). The great debt divergence and its implications for the COVID-19 crisis: Mapping corporate leverage as power. New Political Economy, 26(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, O. J., & Daniel, L. (2013). Growth Forecast Errors and Fiscal Multipliers. American Economic Review, 103(3), 117–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, D., & Raffertty, M. (2006). Capitaism with derivatives—A political economy of financial derivatives, capital and class. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Che, N. (2010). Factor endowment, structural change, and economic growth. MPRA Paper. University Library of Munich. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. (2019). Technology adoption, capital deepening, and international productivity differences. Journal of Development Economics, 143, 102388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., Long, H., & Qin, C. (2020). The impacts of capital deepening on urban housing prices: Empirical evidence from 285 prefecture-level or above cities in China. Habitat International, 99(4), 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., & Zhang, C. (2023). The impact of financial agglomeration on corporate financialization: The moderating role of financial risk in Chinese listed manufacturing enterprises. Finance Research Letters, 58, 104655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q., & Chen, Z. (2024). Mandatory internal control audit and corporate financialization. Finance Research Letters, 62, 105085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Cao, Y., Cao, Q., Li, J., Ju, M., & Zhang, H. (2024). Corporate financialization and digital transformation: Evidence from China. Applied Economics, 56(57), 7876–7891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davanzati, G. F., Pacella, A., & Salento, A. (2019). Financialisation in context: The case of Italy. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 43(4), 917–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L. E. (2017). Financialization and the non-financial corporation: An investigation of firm-level investment behavior in the United States. Metroeconomica, 69(1), 270–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, F. (2009a). Capital market imperfections and financialization of real sectors in emerging markets: Private investment and cash flow relationship revisited. World Development, 37(5), 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, F. (2009b). Financial liberalization, private investment, and portfolio choice: Financialization of real sectors in emerging markets. Journal of Development Economics, 88(2), 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despain, H. G. (2015). Secular stagnation: Mainstream versus Marxian traditions. Monthly Review, 67(4), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebiger, B. (2016). Rethinking the financialisation of non-financial corporations: A reappraisal of US empirical data. Review of Political Economy, 28(3), 354–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fligstein, N. (1990). The transformation of corporate control. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X. X., Wang, S. S., & Jia, J. (2024). Equity incentives and dynamic adjustments to corporate financialization: Evidence from Chinese A-share listed companies. International Review of Economics & Finance, 92, 948–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Wang, Z., Wang, K., Zhang, R., & Lu, Y. (2023). Effect of big data on enterprise financialization: Evidence from China’s SMES. Technology in Society, 75, 102351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K., Hang, J., & Yan, S. (2022). Structural change and the skill premium. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 62, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M., Li, N., Guo, F., & Li, X. (2025). The state capital investing and operating company pilot reform and the financialization of the Chinese SOEs. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmann, R. (2017). Financialization revisited: The rise and fall of finance-led capitalism. Economia e Sociedade, 26, 857–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B., Cui, Y., & Chan, K. C. (2022). Firm-level financialization: Contributing factors, sources, and economic consequences. International Review of Economics & Finance, 80, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Luo, Y., & Peng, Y. (2021). Corporate financial asset holdings under economic policy uncertainty: Precautionary saving or speculating? International Review of Economics & Finance, 76, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., & Li, S. (2024). Female directors, ESG performance and enterprise financialization. Finance Research Letters, 62, 105266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, M. (2010). From Marx to Goldman Sachs: The fictions of fictitious capital, and the financialization of industry. Critique, 38, 419–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, I. I. (2019). Chasing the crowd: Digital transformations and the digital driven system design paradigm. In International symposium on business modeling and software design 2019 (Vol. 356, pp. 64–80). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Janowski, T. (2015). Digital government evolution: From transformation to contextualization. Government Information Quarterly, 32(3), 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinge, T. J., Fernandez, R., & Aalbers, M. B. (2021). Whither corporate financialization? A literature review. Geography Compass, 15(9), e12588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippner, G. R. (2005). The financialization of the american economy. Socio-Economic Review, 3(2), 173–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippner, G. R. (2011). Capitalizing on crisis: The political origins of the rise of finance. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., & Russell, R. R. (2002). Technological Change, Technological Catch-up, and Capital Deepening: Relative Contributions to Growth and Convergence. The American Economic Review, 92(3), 527–548. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3083353 (accessed on 8 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lazonick, W. (2010). Innovative business models and varieties of capitalism: Financialization of the US corporation. Business History Review, 84, 675–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. S., Kim, H. S., & Hwan Joo, S. (2020). Financialization and Innovation Short-termism in OECD Countries. Review of Radical Political Economics, 52(2), 259–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., & Hua, Y. (2025). The effect of corporate executives’ academic experience on firm financialization-evidence from listed manufacturing firms in China. Research in International Business and Finance, 73, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. Y. (2011). New structural economics: A framework for rethinking development. The World Bank Research Observer, 26(2), 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., & Lv, L. (2023). The effect of China’s low carbon city pilot policy on corporate financialization. Finance Research Letters, 54, 103787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, C., Hess, T., & Benlian, A. (2015). Digital transformation strategies. Business and Information Systems Engineering, 57(5), 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K., Friedrich von den Eichen, S., Anschober, M., & Kohler, T. (2018). The crusade of digital disruption. Journal of Business Strategy, 39(6), 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhangazi, O. (2006). Financialization of the US economy and its effects on capital accumulation: A theoretical and empirical investigation [Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst]. [Google Scholar]

- Orhangazi, O. (2008). Financialisation and capital accumulation in the non-financial corporate sector: A theoretical and empirical investigation on the US economy: 1973–2003. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 32(6), 863–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers and challengers. African Journal of Business Management, 30, 4015–4023. [Google Scholar]

- Özge, Ö. (2015). Is capital deepening process male-biased? The case of Turkish manufacturing sector. Structural Change & Economic Dynamics, 35, 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pariboni, R., Meloni, W. P., & Tridico, P. (2020). When Melius abundare is no longer true: Excessive financialization and inequality as drivers of stagnation. Review of Political Economy, 32(2), 216–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y. C., Han, X., & Li, J. J. (2018). Economic policy uncertainty and corporate financialization. China Industrial Economics, 1(1), 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y., Yang, Y., Yang, S., & Lyu, S. (2021). Does government funding promote or inhibit the financialization of manufacturing enterprises? Evidence from listed Chinese enterprises. North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 58, 101463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, J., & Reddy, N. (2024). Corporate financialization: A conceptual clarification and critical review of the literature. Working Papers PKWP2402. Post Keynesian Economics Society (PKES). [Google Scholar]

- Rachinger, M., Rauter, R., Müller, C., Vorraber, W., & Schirgi, E. (2018). Digitalization and its influence on business model innovation. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 30(8), 1143–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuram, G. R., & Zingales, L. (1995). What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. Journal of Finance, 50(5), 1421–1460. [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo, B. (2017). Financialisation and real investment in the European union: Beneficial or prejudicial effects? Review of Political Economy, 29(3), 376–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, B., & Sérgio, L. (2017). Financialization and Portuguese real investment: A supportive or disruptive relationship? Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 40(3), 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J., & Zhang, X. (2018). How to explain corporate investment heterogeneity in China’s new normal: Structural models with state-owned property rights. China Economic Review, 50, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, D. K., Wan, S., Li, X. L., & Kong, D. (2022). Economic policy uncertainty and shadow banking: Firm-level evidence from China. Research in International Business and Finance, 63, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockhammer, E. (2008). Some stylized facts on the finance-dominated accumulation regime. Competition & Change, 12(2), 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockhammer, E. (2012). Financialization, income distribution and the crisis. Investigacion Economica, 71, 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K., & Liu, H. (2021). Financialization of manufacturing companies and corporate innovation: Lessons from an emerging economy. Managerial and Decision Economics, 42, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K., & Lu, Y. (2023). The impact of corporate social responsibility on corporate financialization. The European Journal of Finance, 29(17), 2047–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F. E., & Tian, Z. W. (2021). Insurance capital listing and financialization of real enterprises: “Inhibitor” or “booster”. Securities Market Review, 10, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sweezy, P. M. (1995). Economic reminiscences. Monthly Review, 47(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y., Wang, L., & Shu, H. (2024). ‘Tax reduction’ and the financialization of real enterprises: Evidence from China’s ‘VAT reform’. International Review of Economics & Finance, 92, 835–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellalbasi, I., & Kaya, F. (2013). Financialization of Turkey industry sector. International Journal of Financial Research, 4, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaskovic-Devey, D., Lin, K.-H., & Meyers, N. (2015). Did financialization reduce economic growth? Socio-Economic Review, 13(3), 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tori, D., & Onaran, Ö. (2018). The effects of financialization on investment: Evidence from firm-level data for the UK. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 42(5), 1393–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. J., Li, M., & Tang, T. (2016). The driving factors of cross-industry arbitrage and its impact on innovation. China Industrial Economics, 11, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Włodzimierz, R. (2018). Financialization and its impact upon the developed economies. Ekonomiczne Problemy Usług, 131, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., & Xuan, C. (2021). A study on the motivation of financialization in emerging markets: The case of Chinese nonfinancial corporations. International Review of Economics and Finance, 72, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. H., & Chen, S. Y. (2023). Corporate financialization, digitalization and green innovation: A panel investigation on Chinese listed firms. Innovation and Green Development, 2(3), 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Liu, F., & Wang, H. J. (2017). Are corporate financial assets allocated for capital reserve or speculative purpose? Management Review, 29, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C., Liu, C., Ma, Y., & Yang, C. (2025). Managerial myopia and corporate financialization: Evidence from China. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 36(1), 184–214. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C., & Zheng, N. (2020). The financial investment decision of non-financial firms in China. North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 53, 101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, H., Yang, L., & Xu, P. (2023). Managerial ownership and corporate financialization. Finance Research Letters, 58, 104682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q., Gan, Y. H., Song, L. J., & Fan, S. Q. (2025). Research on the impact of corporate financialization on debt financing level: From the dual perspectives of risk-taking and earnings management. International Review of Economics & Finance, 103, 104328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., & Su, K. (2022). Economic policy uncertainty and corporate financialization: Evidence from China. International Review of Financial Analysis, 82, 102182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).