1. Introduction

Periods of monetary tightening are historically among the most consequential phases for both macroeconomic dynamics and financial market performance. Central banks, particularly the Federal Reserve (Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB), adjust policy rates in response to inflationary pressures and economic overheating. Yet, the aftermath of such actions—whether they result in a soft or hard landing—remains a central and debated issue in macro-financial research.

The concept of a “soft landing” refers to a scenario in which monetary policy successfully slows down inflation without triggering a recession by raising interest rates just enough. Conversely, a “hard landing” entails a policy-induced contraction in output and employment due to a harsh rise in interest rates. The empirical literature has explored these outcomes through various lenses, including monetary policy rules, market reactions, and credit transmission mechanisms (e.g.,

Clarida et al. (

2000);

Gertler and Karadi (

2015)). However, existing studies often focus on individual tightening episodes or rely on ex-ante policy stances rather than ex-post market outcomes. Moreover, relatively few papers contrast multiple historical cycles using updated data that include the post-COVID tightening phase.

This paper addresses this gap by providing a preliminary comparative analysis of recent monetary tightening cycles in the U.S. and Europe. We focus on three periods: the 1994–1995 rate hike cycle, the 2004–2006 gradual tightening, and the current post-pandemic phase beginning in 2022. Using an OLS regression approach and correlation analysis, we evaluate the transmission of rate hikes to inflation, GDP growth, and equity markets. Our model includes both monetary variables (short-term interest rates, central bank balance sheets) and real economy indicators, enabling a comprehensive assessment of landing trajectories. Therefore, a novel perspective is introduced by extending the traditional macroeconomic focus on the real economy to also examine the reactions of financial markets—both equity and debt—to contractionary monetary policy. Our aim is to uncover stylized patterns and directional relationships that can inform further research and policy discussion. While we acknowledge the limitations of this approach—including dynamic modeling and structural identification—our objective is to provide an intuitive and transparent first look at the empirical relationships in each episode.

The results indicate that while past episodes generally resulted in soft landings, the current environment exhibits features of both soft and hard dynamics—what we term a “two-phase landing.” Initial resilience in growth indicators is now giving way to fragility in equity markets and persistent inflation, raising the possibility of delayed recessionary pressures.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on monetary tightening and macro-financial transmission.

Section 3 outlines the data and methodology.

Section 4 presents empirical results and

Section 5 the related robustness checks.

Section 6 concludes with implications for monetary policy and future research directions.

2. The Existing Literature: Alan Greenspan’s Standards

In connection with the main purpose of the discussion—assessing the “landing” nature of a tightening cycle pursued by Central Banks—the existing literature is mainly related to the key pillars to follow in order to achieve a successful soft-landing (referring to Greenspan’s innovative institutional arrangements which were introduced by the first “soft-lander” in history) as well as to macroeconomic variables related analysis to point out the delivered results of a contractionary monetary policy in the real economy. Before analyzing the existing literature in terms of rising interest rates in inflationary scenarios and its impact on economic activity, it is worth understanding the exact meaning of the headline-grabbing words “soft-landing” and “hard-landing”. Broadly speaking, “soft-landing” means an economy growth only slightly impacted by rising interest rates to slow down inflation, while “hard-landing” represents the scenario characterized by a substantial slump in economic activity (recession) caused by the hawkish tone of Central banks to counteract inflationary scenario. In other words, the latter is a worst-case scenario in which the increase in benchmark interest rates from Central Banks achieves the objective in terms of target interest rate as well inflation rate, but at the expense of a severe recession with lower demand, consumption and investments, probably leading Central Banks to return back to a more expansive monetary policy. In this context, a significant contribution for the institutional arrangements for monetary policy must be attributed to Alan Greenspan, the chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 31 January 2006, who has been blamed for the 2008–2009 financial crisis despite his previous successful interventions. The way he managed the monetary policy of the Federal Reserve in different macroeconomic and political scenarios, from the Iranian Crisis immediately after its appointment to the Dot-Com bubble at the beginning of the new century, has left many teachings for his successors and more, in general, for future economists (e.g., he was the first to successfully implement a “soft-landing” in 1994–1995). Broadly speaking, he changed the way of implementing monetary policy and its contribution was revolutionary if compared to its predecessors. It is not wrong to say that there exists a monetary policy framework before Alan Greenspan and one after Alan Greenspan. Firstly, it is worth understanding the innovative contribution of his monetary policy and those which are known as “Greenspan’s Standards”.

2.1. Discretion Rather than Rules

From the 1970s, many economists (

Barro & Gordon, 1983;

Athey et al., 2005) started to outline a new way of thinking on monetary policy, which rejected discretionary decisions in favor of stricter rules, citing that period-by-period discretion could lead to higher inflation. From their perspective, “rules” in monetary policy decisions aim to establish Central Banks’ credibility by a sort of “constraining behavior” (

Linder & Reis, 2005, p. 6). Greenspan, unsurprisingly, did not agree with this view. However, it is worth mentioning that Greenspan’s monetary policy did not follow an unpredictable and irregular behavior but was driven by flexibility and adaptability to changing scenarios and macroeconomic backdrop, as well as a sound set of principles which were in line with Federal Reserve mandate and objectives. Part of Greenspan’s discretionary framework involved close monitoring of financial markets, particularly equity and bond markets, as real-time indicators of macroeconomic expectations. Empirical literature (e.g.,

Rigobon and Sack (

2004);

Bernanke and Kuttner (

2005)) shows that equity prices typically respond sharply to unexpected monetary decisions, particularly rate hikes. Similarly, bond yields, especially at the long end, respond to forward guidance and perceived inflation credibility. This suggests that financial markets should not be treated as secondary but as central to understanding how policy expectations are formed and transmitted. Moreover, Greenspan did not share the attempt of many macroeconomists trying to transform into a formula the main target of Central Banks through a minimizing exercise on the discounted value of the below periodic loss function

1:

where

is the inflation rate and

u2 the unemployment rate, while

* and

are the targets set by Central Banks, in which the parameters could be known or unknown but with a determined probability distribution. To finally compare the two different perspectives (rules vs. discretion), rule-related models have the clear advantage of speeding up computations, estimations and monetary policy decisions. However, this kind of model are verifiable and consequently falsifiable. In other words, it is very difficult to demonstrate that a model that worked in 1970s will also able to describe the economic scenario in 2022 with the same parameters.

2.2. Risk Management Rather than Optimization

Instead of optimization procedure, Greenspan introduced a new, different pattern for monetary policy: a risk management approach. It is comparable to the risk management framework which the Federal Reserve requires of financial institutions under its supervision: a set of tools, control mechanisms and structures to control activity and reduce exposure to adverse outcomes. According to criteria set forth in the Fed’s manual for bank supervisors (Federal Reserve Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual), one of the most important tools in a risk management framework is a risk matrix (see below an example) that should be used to “used to identify significant activities, the type and level of inherent risks in these activities, and the adequacy of risk management over these activities, as well as to determine composite risk assessments for each” (

Linder & Reis, 2005, p. 10). The risk assessment process consists in a sort of balancing between the level of the identified risk (which can be stated as low, moderate or high) and the overall effectiveness of the risk management framework for the measurement of that risk (which can be rated at weak, acceptable or strong). This framework, reported in

Table 1, inherently integrated financial markets—particularly stock and bond markets—into monetary policy deliberation. For example, widening credit spreads, declining equity valuations, or an inverted yield curve were viewed as warning signs of deteriorating conditions. These were not merely passive outcomes of monetary policy but active inputs into the policy decision-making process. Several studies (e.g.,

Gürkaynak et al. (

2005)) confirm that monetary surprises influence the term structure of interest rates and risk premia, particularly in periods of uncertainty. The resulting bond market adjustments can, in turn, affect borrowing conditions, investment flows, and equity market volatility. Therefore, Greenspan’s risk matrix implicitly acknowledged the interplay between monetary tightening and financial market stability. The equity and bond markets, in this framework, become early signals of whether the tightening is leaning toward a soft or hard landing outcome.

Considering the strong interconnection between the real economy and financial markets, the matrix identifies two different sources of risk: macroeconomic risk (e.g., high inflation or low employment) and financial risk. Considering that the genesis of a macro risk could emerge from either the demand side (where Central Banks have some intervention power) or the supply side (where they do not), the table takes separately into the account the risks arising from demand shocks and supply shocks. On the other hand, the table includes also the main sub-categories of financial risk, namely banking risk, credit risk, stock market risk, debt market risk and other financial sector risk. Broadly speaking, the risk matrix below could help monetary policy makers to focus attention on the rising inflation risk as well as supply side shocks (such as in the current scenario characterized by skyrocketing oil prices). Finally, it also draws attention to potential bond market shocks, mainly related to Central Banks’ speeches and short-term interest rate volatility.

2.3. Fine Tuning

In the years Alan Greenspan was the chairman of Federal Reserve, many economists and policy makers (e.g.,

Svensson (

2001)) have refused the concept that monetary policy should be used as a “fine tuning” instrument. Instead, still confirming its revolutionary path vis-à-vis thoughts and notions of that time, Greenspan was one of the strongest supporters of fine tuning and probably one of the most successful in using this instrument. Firstly, it is worth stating a definition of fine tuning which is similar to what Greenspan pursued in its monetary policy. Citing Blinder and Reis in Understanding the Greenspan Standard (

Linder and Reis (

2005), p. 27), this definition seems to capture Greenspan’s intention in the right way: “Using frequent small changes in the Central Bank’s instruments, as necessary, to try to hit the Central Bank’s targets fairly precisely.” One of the unmistakable signs of its “modus operandi” (not followed before him) was moving the Federal Fund Rate by exactly 0.25% (25 bps). This “innovation” was also linked to the Federal Reserve decision to focus more and more on Fund Rate rather than borrowers’ reserve. As a matter of fact, from June 1989 to January 2005, Federal Reserve changed rates 68 times, coinciding with +/−25 bps changes for 51 times. By way of reference, 16 of the other 17 changes were of 50 bps. Given the progressive small changes to interest rates, any significant cumulative easing/tightening movement requires many adjustments. It took place in 18 steps in 1988–1989, when Greenspan increased the interest rate by a cumulative 331 bps; in 1994–1995 (the first acclaimed “soft-landing” by Greenspan) tightening tone of 300 bps came in seven steps, while in 1999–2000 the 175 bps increase followed six stairs. Finally, in 2004–2006 (last decision started by Greenspan as chairman of Federal Reserve and continued by its successor Bernanke), the interest rate was increased by 425 bps in 17 steps, each of 25 bps. There are at least three reasons supporting Greenspan’s “gradualism” (

Linder & Reis, 2005, p. 30):

Interest-rate smoothing: As of today, the short-term interest rate (e.g., Federal Fund Rate, ECB Main Refinancing Operation rate) is the main instrument in the toolbox of Central Banks to implement their monetary policy. There are at least two standpoints from which seems shareable changing interest rates with steady small movements rather than sudden changes. First of all, sharp variations in the short-term interest rate could determine broader volatility in long-term interest rates (especially in the bond market), which could consequently lead to a sizeable financial risk and financial instability. This could be displayed in the above-mentioned losses’ function summarizing the main objectives of Central Banks: indeed, adding a new quadratic factor in the formula γ(it-it-1)2, larger movements in interest rates between period t and t−1 will determine higher losses. Furthermore, in accordance with expectation theory, when a Central Bank starts changing interest rates, market participants expect that in the immediate future movements will follow the same trajectory, allowing the price-setter to modify and fairly adjust assets prices;

Reverse course aversion: In connection with the last point outlined, an unbreakable dogma in people’s minds is the Central Bank’s infallibility. In light of this, it is almost utopistic that a Central Bank will rapidly revert its monetary policy after starting an easing (tightening) movement, firstly for a sort of reluctance to recognize the mistake and, secondly, to avoid increasing market volatility.

This interest-rate smoothing was particularly beneficial for financial markets, which tend to react negatively to abrupt and unpredictable policy moves. Smooth, transparent rate changes helped anchor expectations in both equity and bond markets. The literature has shown that policy predictability reduces equity volatility and prevents abrupt sell-offs, while also stabilizing term premia in bond markets. The stock market, in particular, is highly sensitive to monetary signals about future economic activity. A tightening policy viewed as preemptive rather than reactive tends to be absorbed more smoothly by equities, whereas surprises or aggressive stances can trigger corrections. Despite the many outlined positive aspects of fine tuning, there is also a potential limitation: the excessive gradualism could prevent interest rates increasing rapidly to counteract inflationary scenarios, as well as decreasing fast enough to support a faltering economic backdrop.

2.4. Taylor’s Rule Applied to Greenspan’s Decision

As mentioned above, Greenspan did not rely on any rule-related model in the decisions and implementation of monetary policy. However, the model which outlines a sort of proximity to Greenspan’s decision is the Taylor rule (1993)

2:

where

u is the unemployment rate,

u* represents the natural rate of unemployment,

π is the core CPI inflation rate,

π* is the target of inflation rate, while

α and

β are coefficients which captures the sensitivity of monetary policy with respect to unemployment rate and inflation rate, respectively. As outlined by

Linder and Reis (

2005), the Taylor formula fits well with Greenspan’s monetary policy. Indeed, if the formula above is estimated (with two lags of Federal Fund Rate to neutralize serial correlation) for quarterly data from 1987 to 2005, it displays an adjusted coefficient of determination R

2 of 0.97 and a standard error of 39 bps. This does not mean that Greenspan’s activity is largely predictable because, as stated before, discretion is one of its main pillars. It is worth flagging three situations in which his monetary policy differed significantly from what the Taylor rule prescribed:

The period 1989–1992: The first ever attempt of a “soft-landing” in history. It was almost achieved (average growth stable at 2.8% from 1988 to 1990), even if the literature does not assign the right merit to Greenspan, citing a recession beginning in August 1990. In reality, the economic downturn was related to geopolitical reasons rather than the hawkish tone from the Federal Reserve, triggered by the Japan bubble (driven by inflated real estate and stock market prices) and oil price shocks following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait (Saddam Hussein’s second invasion of a fellow OPEC member);

The period 1998–1999: The already-mentioned easing movements, given the increasing financial instability following Russian debt default and the collapse of LTCM;

The period 2001–2002: The sharp decrease in the Federal Fund Rate from 6% to 1.75%, following 11 September attacks and consequently recession concerns and fears over financial instability.

Furthermore, looking at macroeconomic variable trends during its mandate, it is rather evident that he successfully managed to control both inflation and unemployment under its multiple mandates, without any stricter rule. As a matter of fact, the average unemployment rate over the period was just 5.55% vis-à-vis an average of 6.85% observed in the previous 18 years before its first mandate. Regarding inflation, at the time of its establishment, the 12-month average increase in the core CPI Index was 3.9% while it decreased to 2.1% in 2005. However, what is less often emphasized is how financial market behavior aligned—or diverged—from Taylor-based predictions. For instance, during the 1994–1995 tightening cycle, bond markets initially reacted with sharp yield increases due to poor communication, while equity markets stabilized after policy guidance became clearer. Conversely, in 1999–2000, the Fed’s tightening cycle was accompanied by equity market exuberance, which eventually collapsed, suggesting a disconnect between policy signals and market interpretations. Such episodes highlight the need to study financial market reactions in parallel with macro outcomes when assessing landing dynamics. Ignoring bond and equity markets risks missing key early signals of policy effectiveness or overshoot. In a nutshell, Greenspan has outlined that, following some essential principles—flexibility, risk management approach, fine tuning and transparency of communication to the markets—it is possible to reach a soft-landing. However, also considering the growing interconnection between the real economy and financial markets since the end of the last century, it is useful to extend the analysis to financial market trends, assessing whether tightening cycles impact similarly on both the real economy and equity and debt capital markets and whether the financial markets trends are also reliable to outline the nature of the landing.

3. Data and Methodology

In accordance with the main aim of the project, the “soft” (“hard”)-landing of rising interest rates in an inflationary scenario is assessed looking not only at macroeconomic data (i.e., GDP growth rate, inflation rate and unemployment rate), but also at equity and debt capital markets as well as the private loan space (in US and Europe), as they are key thermometers of the economic and financial situation. The study finds support also from the increasing connection between real economy and financial markets. Monetary policy tightening could be perceived positively by investors as an effective anti-inflationary measure, thereby driving up stock market indices, sustaining investment levels, and contributing positively to output dynamics. Moreover, tighter monetary conditions may attract foreign capital inflows, which can mitigate negative impacts on investment and growth. In light of this, the analysis on the equity capital markets is applied to the most representative and liquid index of US and European markets, namely S&P 500 and Eurostoxx 50, respectively. Furthermore, the analysis is corroborated by a simple regression model that is built to better evaluate and check the relationship displayed by correlation coefficients. The model displays stock index as dependent variable (

) and interest rate as independent variable (

):

The same regression is also replayed with a 3-month time lag on the stock index, as it is realistic to assume that equity markets could react with some delays to interest rate increases, especially if it is unexpected and not already “priced” before. It is worth mentioning that, considering the different units of measurement of the variables analyzed and the lack of a linear relationship between them, the daily observations are transformed in the form of natural logarithm. This transformation is justified by the nature of financial data, where relationships are often multiplicative rather than additive. Equity index returns tend to exhibit percentage-based changes rather than absolute shifts, making a log transformation more appropriate. Moreover, applying the natural logarithm helps to stabilize variance and normalize the distribution of returns, which improves the interpretability and reliability of the regression results. The transformation makes sense only if it is reasonable to assume an exponential relationship between the two variables—a reasonable assumption in this case, given that small, progressive increases in interest rates typically lead to compounding effects on equity prices—and the

can be interpreted as the percentage change in the stock index (

) to a 1% increase in interest rate (

)

3. Our empirical framework focuses exclusively on discrete tightening episodes rather than the full sample, thus avoiding concerns on mixed integration orders. This event-based restriction reduces the likelihood of persistent unrelated trends dominating the relationship, as both series in these windows tend to move in response to the same macro-financial shocks. In addition, focusing on these restricted periods of rate hikes ensures that the log transformation is applied to data segments with comparable volatility and trend characteristics, further mitigating risks of spurious correlation. On the other hand, the impact on the debt markets is investigated on both the public and private space: bonds and syndicated loans. For the former, the analysis looks at the Bloomberg Indexes (available for both US and European markets) which represents a reliable benchmark for bonds yield (e.g., ICE Indexes, Bloomberg Barclays Indexes). It is also worth mentioning that Bloomberg Indexes distinguish between rating classes and this allows to carry out an analysis in both the investment grade space (BBB rating category as reliable benchmark) and in the HY space (BB rating category), as the impact of rising interest rates could be noticeably different in the two environments. However, despite the equity indexes being available since 1994 and 1998, respectively, for S&P 500 and Eurostoxx 50, bond databases have been developed only from the end of the 1990s in the US and from the beginning of the new century in Europe, together with growing volumes of new issuances thanks to the speedy development of securities markets. For this reason, the analysis on the bonds market starts from 1998 in the US space and only from 2004 in Europe. Regarding the syndicated loans, data come from the databases of Refinitiv Loan Connector and PitchBook|LCD, respectively, for investment-grade loans and leveraged transactions. Considering the private nature of loan details, databases are less trustworthy in the first years following first data collection, as the number of deals disclosed have substantially increased after the worldwide financial crisis of 2007–2009 (especially in Europe). As a matter of fact, for the US, market data are available from 1994 for corporate transactions and 1998 for leveraged deals, while in the European market, historically characterized by lower volumes, statistics start from 2003 for investment grade loans and from 1999 for leveraged ones. These differences in sample lengths are acknowledged as a potential limitation, particularly in terms of directly comparing asset classes and regions over uniform timeframes. Readers should interpret the findings with this caveat in mind: longer time series allow for greater statistical power and robustness, while shorter series—although still meaningful—may be more sensitive to short-term cyclical or structural breaks. Despite this, the inclusion of diverse data series, even with differing time ranges, strengthens the generalizability of the study by capturing a broader spectrum of market responses across economic cycles. For both public and private debt markets, spreads (which are obtained deducting the base rate from the yield) are taken into account, as the base rate increases automatically as a response to Central Banks’ tightening. Equity and market trends are compared with Federal Fund Rate and ECB Main Refinancing rate, as they are the interest rates modified by the Fed and ECB. By way of reference, the Federal Fund Rate is the target interest rate determined by the Fed, at which commercial banks can borrow/lend their reserves for a very short time (overnight). Instead, the ECB Main Refinancing rate represents the interest rate paid by banks when they borrow from the ECB for a duration of one week. In addition to this analysis on financial markets, for each period conventional macroeconomics statistics are reported to better assess the impact on the real economy. It is important to note that the debt and equity markets are analyzed through different approaches due to fundamental differences in data availability and instrument structure. Equity markets offer continuous, high-frequency pricing data, which permits regression analysis and correlation testing. In contrast, bond and syndicated loan data—particularly in private markets—are often monthly, illiquid, or limited to specific reporting windows. Therefore, debt market assessment relies more heavily on spread trends and margin evolution. Nonetheless, this approach remains analytically consistent. In each period, spread and margin movements are interpreted in relation to macroeconomic and monetary policy changes. Across all tightening episodes analyzed, debt markets either remained resilient or improved, indicating that tightening cycles—when orderly—do not necessarily induce financial distress.

4. Discussion of the Results

4.1. US Economy: 1994–1995

The first truly achieved “soft-landing” of the history was obtained by Alan Greenspan in 1994–1995. Greenspan started its tightening policy in February 1994, increasing the Federal Fund Rate from 3% to 3.25%. Almost one year later, in January 1995, Greenspan completed the cycle, increasing the rate to 6% (+3% in a year in seven steps). It is worth mentioning that the tightening was rather aggressive: in contrast with Greenspan’s modus operandi, not all the increases were by 0.25%, but three of them were by 0.5% and one (in November 1994) by 0.75%. Despite the vigorous and rapid increase, both real economy and financial markets reacted very positively, resulting in a convincing “soft-landing”. Firstly, GDP growth rate reached 4% in 1994 (1% higher the value observed in 1993) and c.3% at the end of 1995 (in line with GDP growth in place before the tightening). Another signal of the extraordinary success of Greenspan’s policy was highlighted by the unemployment rate, which reached 5.6% in 1995 (almost 1% below the value observed in 1993) as well as the mild downward trend experienced by inflation rate which landed to 2.5% in 1995 (according to many economists, this value coincided with the natural inflation rate target). Also, financial markets performance confirmed the positive reaction seen in the real economy and the result should not appear obvious, considering the weaker connection between the real economy and securities markets, also due to the still ongoing development of the latter. Indeed, US equity market (see

Figure 1, Graph 1,

Section 1) did not suffer any substantial downturn but only a limited deceleration, as outlined by the S&P 500 performance: it traded at 467 pts in January 1994 and 472 pts in February 1995, concurrently with the last increase pursued by Greenspan (the average in the period was equal to 460 pts). Furthermore, the effective “soft-landing” is evident if it is considered the strong positive momentum which followed in the next months, since the index reached 615 pts at the end of 1995, resulting in a +30% vis-à-vis the value observed in January 1994. The thesis of the “legendary perfect soft-landing” (

Blinder, 2022) is also confirmed by statistical analysis. With a sample size of 380 daily observations, firstly, as in

Table 2, the correlation coefficient between the daily values of S&P 500 and Federal Fund Rate in the sub-period 1994–1995 is equal to 0.55, displaying a rather strong positive correlation between the two variables, which followed a similar path (upward trend) in the period. The value is particularly significant if compared to the correlation coefficient for the whole time-horizon (1994–2022), −0.46, which fit adequately to the widespread economic thinking, according to which an inverse relationship exists between equity performance and interest rates (easing policy should result in an economy stimulus and consequently a positive stock trend while the tightening cycle should slow down economic activity and this should be reflected in a negative performance in equity capital markets). Not only, but the results are also corroborated by a “control” regression model (

Table 3, model 1), which exhibits an adjusted R

2 of 0.3 and a positive and statistically significant β estimate of 0.13, meaning that an increase of 1% in Federal Fund Rate (i.e., 1 bps starting from 1% of Federal Fund Rate) corresponds to an increase in the stock index of 0.13%. The small percentage change could seem meaningless, but the main aim of the “soft-landing” analysis is not demonstrating that an increase in interest rates causes a better equity performance, but that, despite a tightening monetary policy expected to cool down the economy, no relevant negative impact on equity performance is noted (this is rather evident from data). Moving to debt analysis, unfortunately bond and leverage loan statistics are not available for this historical period, as they start from 1998. However, looking at the margin of investment grade loans (

Figure 1, Graph 3,

Section 1), the data still confirm the achieved “soft-landing”. As a matter of fact, the spread followed a mild downward trend in 1994–1995 (passing from an average of 48 bps to 38 bps), benefitting from the confident market sentiment and improving economy backdrop, resulting in better borrowers’ credit metrics.

Correlation. This table illustrates the correlation for the US models between the dependent variable and the explanatory variable considered in the regression analysis.

4.2. US Economy: 1999–2000

From June 1999, Greenspan began a new tightening measure (increasing the Federal Fund Rate by 0.25 bps from 4.75% to 5.00%), reaching 6.5% in May 2000 in six steps increase. Firstly, evaluating the economic environment at the end of the cycle, the efficiency of the measure is rather tangible: GDP growth only slightly decreased to 4.1%, while inflation rate was stable around 3%. On the other hand, Greenspan’s detractors pointed to the “job losses” increase as the main argument to sustain their “hard-landing” thesis. However, in this case, the criticism had some validity as the unemployment rate increased to 5.8% in 2000 and remained almost stable to 5.6% in 2001. On the other hand, equity and debt capital markets performance responded well to the monetary policy. S&P 500 continued to show a mild upward trend in 1999–2000, increasing by 1.75% (1377 pts on average) in the period (

Figure 1, Graph 1,

Section 2). With a sample size of 504 daily observations, the correlation coefficient between S&P 500 and Federal Fund Rate (daily observation) is equal to 0.49 (

Table 2) and the regression model shows a significant β1^ estimate of 0.23 and an adjusted R

2 of 0.24 (

Table 3, model 2), showing a still growing path despite the tightening cycle pursued by the Fed. In the debt capital markets, bond spread, and margin loans saw only slight widenings, showing still-resilient credit conditions. In particular, in the public market (

Figure 1, Graph 2,

Section 1), bond spread continued to trade in range (c.125 bps) in the investment grade space (BBB rated) while HY Bonds (BB rated) experienced an only limited repricing, in the 20 bps area (from c.260 to c.280 bps). In the private loan market, tightening cycle and cooling down of economic activity made the margin of both corporate loans and leveraged financings (

Figure 1, Graph 3,

Section 2;

Figure 1, Graph 4,

Section 1, respectively) increase up to c.20–30 bps (from c.75 to c.95 bps and from c.280 to c.310 bps, respectively). In this second “soft-landing” attempt, the slowdown of the economy was limited but doubtless more visible than the first acclaimed “soft-landing” in 1994–1995, as outlined by the downward trend of S&P 500 (especially starting from 2H2000), increase in bond spread and loan margin and the drop in GDP growth. Despite the criticism moved to Greenspan regarding the delay of the tightening cycle amid already evident signals of the Dot-com bubble, the economic downturn was a sort of “

recessionette” (

Blinder, 2022) and consequently was very close to a “soft-landing”, as the GDP growth dropped only to −0.1%.

4.3. US Economy: 2004–2006

The last tightening cycle started by Greenspan as chairman of the Fed dates back to the period 2004–2006. The contractionary policy was started by Greenspan and continued by its successor Bernanke, as Greenspan’s mandate ended in January 2006. This is the most aggressive hawkish tone implemented by the Fed in the last 30 years in terms of magnitude of increase (+425 bps, from 1% to 5.25%) and displays also one of the most important Greenspan’s standards: the fine tuning, as the increase was made up of 17 steps, all equaled to 25 bps step up. The contractionary cycle effectively originated a limited slowdown in the economic trajectory, as the GDP annual growth decreased to 3.5% in 2005 and 2.9% in 2006, the inflation rate passed from the 2.7% in 2004 to 3.2% in 2006 (still an acceptable value) while the unemployment rate showed a rather positive trend, decreasing from 5.5% in 2004 to 4.7% in 2006. Assessing the capital markets performance, equity (

Figure 1, Graph 1,

Section 3) continued to rise at a full speed despite the tightening cycle (+28% in the period considered and 1216 pts on average). Positive momentum was also confirmed by statistical analysis. With a sample size of 755 daily observations, the correlation coefficient between S&P 500 and Federal Fund Rate on a daily basis is equal to 0.73 (

Table 2) and the regression model displays a significant β estimate of 0.2 and an adjusted R

2 of 0.53 (

Table 3, model 3). In this period, the equity path continued to follow a positive trend also in the first part of 2007 (despite some signals in the 2H2007, market crashed in 2008). Debt capital markets (

Figure 1, Graph 2,

Section 2) outlined improving pricing terms: Investment grade bonds benefitted from c.25 bps reduction (from c.115 bps to c.80 bps) and HY Bond spread decreased by c.40 bps (from c.230 bps to c.190 bps). On the loans side, both corporate and leveraged financings (

Figure 1, Graph 3,

Section 3;

Figure 1, Graph 4,

Section 2, respectively) showed a more favorable “price”, since margin decreased by c.30 bps (from c.90 to c.60 bps for BBB-rated borrowers and from c.220 to c.190 bps for BB-rated borrowers), confirming the strong credit environment, as perceived by investors and banks. which required lower and lower compensation on bonds and loans, maybe not assessing fairly the risk of the borrowers (the credit bubble which was one of the main causes of the financial crisis). In light of this and considering only the period of tightening (July 2004–June 2006), the contractionary monetary policy pursued by Greenspan could be considered another efficient “soft-landing”, given the only limited slowdown in the economy’s growth followed by a decline of the unemployment, as well as the improving markets conditions on both equity and debt side. Also in this case, the only criticism is related to its “lazy” tightening, which may have contributed to the genesis of the credit and house-price bubble.

4.4. US Economy: 2017–2019

The last tightening implemented by the Fed (before the current and ongoing contractionary policy) started with Yellen and continued with Powell, the current chairman of Fed (has been in the office since February 2018) and clearly followed Greenspan’s fine tuning. It was intended as a very gradual normalization cycle. As a matter of fact, it took almost two years (from March 2017 to December 2018) and seven steps to raise the Federal Fund Rate by only 175 bps. Also in this case, the tightening cycle implemented by the Fed displayed an evident effectiveness in terms of consequences on the real economy: GDP growth rate remained stable at 2.2% in 2019, the inflation rate declined to 1.8% (from the 2.4% of the previous year) and the labor market remained very strong, as the unemployment rate was only equal to 3.5% (the lowest value since 1969) vis-à-vis the 5% observed in 2015. Equity performance (

Figure 1, Graph 1,

Section 4) showed a persistent growth trend in the period (+24% and 2600 pts on average versus 2250 in March 2017), not showing any significant impact of contractionary policy on S&P 500 “running”. Positive equity performance in the period is also confirmed by statistical analysis. With a sample size of 648 daily observations, the correlation coefficient is equal to 0.85 and regression model displays a significant β1^ estimate of 0.17 and an adjusted R

2 of 0.7 (

Table 3, model 4). With regard to the debt capital markets performance (

Figure 1, Graph 2,

Section 3), investment grade bonds did not recognize any price adjustments (average spread 155 bps versus 170 bps at the beginning of the tightening). HY bond spread followed a similar trend, with an average of c.230 bps which compares well to the 270 bps of March 2017. In the private loan market, plain corporate financings (

Figure 1, Graph 3,

Section 4) continued to display a margin in the 120 bps area without any repricing also due to the relationship-based nature of most exercises, while the leveraged loan (

Figure 1, Graph 4,

Section 3) margin remained steady in the 250 bps area. Considering the limited slowdown in economy’s growth and the lack of any impact on equity and debt capital markets, despite a transient crisis in late-December 2018, the tightening cycle could be easily considered another successful “soft-landing” and fine tuning. Finally, the high adjusted R

2 value of 0.70 observed in

Table 3, model (4), corresponding to the 2017–2019 period, deserves special mention. This notably higher explanatory power reflects a unique combination of factors specific to that period. First, the tightening cycle during this time was gradual and well-telegraphed to markets, reducing volatility and allowing financial markets to respond more systematically to policy moves. This policy predictability is likely to have strengthened the observed linear relationship between the Federal Fund Rate and the S&P 500, improving model fit. Second, financial markets in 2017–2019 were highly integrated, liquid, and driven significantly by macro policy signals, particularly interest rate expectations, which may explain why the regression model captures a larger portion of the variation in the dependent variable. In contrast, the lower R

2 values seen in earlier models (e.g., 0.30 in 1994–1995 or 0.24 in 1999–2000) may reflect noisier market conditions, more structural economic shifts, or the relative immaturity of financial markets at those times. These earlier periods were also characterized by higher uncertainty and more abrupt monetary moves (e.g., large step changes in 1994), which could have introduced greater variability in equity market responses not fully explained by the interest rate alone. Furthermore, markets were not as data-driven or globally interconnected, which reduces the strength of the direct relationship.

4.5. EU Economy: 1999–2000

Almost one year after its establishment as monetary policy “setter” of the Eurozone, ECB implemented the first tightening cycle in Europe: 225 bps increase in seven steps between November 1999 and October 2000, bringing the ECB Main refinancing rate to 4.75% at the end of the cycle. Assessing firstly the real economy route, a positive growth momentum persisted in 2000, showing 3.2% GDP growth, a mild downward trend in the unemployment rate (9.8% versus 10.2% of the previous year), but also a rising inflation rate (3.2%). Instead, in 2001, the economic path faltered on the back of multiple shocks, such as the internet bubble burst, a terrorist attack in the US and geopolitical tensions in Iraq. GDP growth declined to 2% but on the other hand inflation continued to rise, reaching 3.4% in 2001. On the other hand, during the tightening cycle, Eurostoxx 50 rose significantly (+26% and 4985 pts on average) but, since the beginning of 2001, in line with S&P 500 performance, equity index showed increasing volatility, retracing all the gains at the end of 2001 (

Figure 2, Graph 1,

Section 1). The same trend is also highlighted by statistical analysis. With a sample size of 533 daily observations, correlation coefficient between Eurostoxx 50 and ECB Main Refinancing rate (on a daily basis) is equal to 0.4 (versus −0.25 of the whole dataset, in line with the economic theory) as in

Table 4, confirming the same direction path (upward). The regression model (

Table 5, model 1) corroborated the results, showing a significant β1^ estimate of 0.15 and an adjusted R

2 of 0.15. Finally, looking at the margin of leveraged transactions (the only available since Bloomberg Indexes in the euro currency and margin on corporate transactions started from 2004), final pricing terms recognized only limited repricing (in the 25–50 bps area), then remained almost steady in 2001 (

Figure 2, Graph 4,

Section 1). In light of all this, in line with considerations for US space, the first tightening cycle of ECB could be considered an “almost” successful “soft-landing”. Indeed, real economy experienced a significant slowdown only from 2H2001 which, however, did not result in a recession, while financial markets backdrop did not deteriorate significantly (at the end of 2001 Eurostoxx was traded in line with the value observed in November 1999). As per the US space, the equity market collapsed only from the first months of 2002, a sufficient time lag to not give the responsibility of the market turmoil to this tightening, but to the bubble burst.

Correlation. This table illustrates the correlation for the EU models between the dependent variable and the explanatory variable considered in the regression analysis.

4.6. EU Economy: 2005–2007

The last tightening pursued by ECB (before the ongoing contractionary policy which started in July 2022) began in December 2005, ratcheting up ECB Main Refinancing rate from 2% to 4% (June 2007) through eight steps up by 25 bps, showing Greenspan’s fine-tuning standard “transposition” also in the “modus operandi” of ECB. The gradual withdrawal of accommodating policy did not prevent the European economy to continue to follow its robust growth trajectory: GDP rose to 2.8% in 2006 and 2.7% in 2007 and the inflation rate was only slightly above 2% in 2006–2007, in line with the ECB target. Finally, the unemployment rate showed a positive downward trend, touching 7.4% in 2007 versus 9.6% observed in 2005. Regarding equity performance, Eurostoxx 50 showed a strong upward trend between 2005 and 2007 (

Figure 2, Graph 1,

Section 2), in line with the real economy’s path (+26% and 4035 pts on average). The positive trend is also corroborated by statistical results. With a sample size of 297 daily observations, indeed, correlation coefficient between the equity index and ECB Main Refinancing rate is equal to 0.9 (

Table 4) and regression model shows a significant β1^ estimate of 0.36 and an adjusted R

2 of 0.46 (

Table 5, model 2). On the debt side, spread on both investment grade and HY bonds (

Figure 2, Graph 2,

Section 1) recognized a substantial downward route, resulting in c.20 bps decrease on BBB rating issuers (50 bps versus 70 at the beginning of the tightening) and c.100 bps decrease on BB rating borrowers (200 bps versus 300 bps in December 2005). A very similar trend was followed by margin on leveraged loans (

Figure 2, Graph 4,

Section 2) which experienced a reduction of c.30 bps (220 bps versus 250 bps), showing improving borrowers’ credit metrics. The only exception is represented by investment grade loans (

Figure 2, Graph 3,

Section 1), whose margin increased by c.20 bps (from c.50 to c.70 bps). However, the increase was not related to a deteriorating credit environment, but a sort of alignment to US space pricing, as European corporate loans were c.20 bps mispriced vis-à-vis US ones. Once the “rather positive” impacts of the tightening cycle on both the real economy and financial markets are assessed, it could seem easy (as for US environment) to consider it a successful “soft-landing”. On the other hand, if we consider the “temporal proximity” between the ends of the tightening and the outbreak of the financial crisis, the cycle could appear as an accelerator of the turmoil. Instead, despite the validity of the criticism related to the delay in the tightening implementation compared to Fed policy, it is worth flagging that the European recession and financial markets collapse were a direct and natural consequence (given the increasing globalization and interconnections between global economies) of houses-price and credit bubbles burst in the US.

5. Robustness Checks

Robustness checks have been used for validating the reliability, stability, and interpretability of empirical findings. They assess how sensitive results are to changes in assumptions, model specifications, or time frames. Key robustness strategy employed in this analysis is the introduction of a 3-month lag between central bank policy rate adjustments and equity market responses. This approach acknowledges that the effects of monetary policy may not be immediate and allows for a more realistic assessment of transmission mechanisms. By analyzing equity index reactions three months after FED and ECB policy actions, this section aims to uncover delayed market dynamics that may be obscured in contemporaneous models and enhance the interpretation of soft-landing outcomes across tightening cycles.

5.1. US Economy

When introducing a 3-month lag in the S&P 500 index relative to Federal Fund Rate changes, the correlation improved significantly to 0.87 (

Table 6), with a β estimate of 0.3 and an adjusted R

2 of 0.7 (

Table 7, Model 1). These metrics support the argument that the equity market responded positively in the months following the final rate hike in February 1995. This enhanced explanatory power confirms that the delayed effect of monetary tightening was absorbed constructively by the market, reinforcing the success of the soft-landing.

In contrast, during the 1999–2000 cycle, the 3-month lag model revealed a notable drop in correlation to 0.1 (

Table 6), with a β estimate of only 0.04 and adjusted R

2 close to zero (

Table 7, Model 2). These diminished statistics likely reflect the emergence of the dot-com bubble burst and market slowdown beginning in the second half of 2000, suggesting that forward-looking investors had begun pricing in economic risks early, muting the delayed effect.

In the 2004–2006 cycle, applying the 3-month lag model yielded even stronger statistical significance. The correlation coefficient rose to 0.83 (

Table 6), and the adjusted R

2 surged to 0.68 with a still significant β estimate of 0.1 (

Table 7, Model 3). These figures indicate that market confidence persisted well into the months following rate increases, illustrating the market’s resilience and optimism amid a gradual and finely tuned monetary tightening process.

Similarly, the 3-month lag model during the 2017–2019 cycle showed almost identical robustness to the contemporaneous model. The correlation remained high at 0.83 (

Table 6), with a β estimate of 0.15 and an adjusted R

2 of 0.7 (

Table 7, Model 4). This consistency demonstrates that the equity market’s performance was largely unaffected by short-term policy shifts, and any delayed effects of the Federal Reserve’s gradual normalization were smoothly absorbed.

Correlation. This table illustrates the correlation for the 3-months’ time lag US models between the dependent variable and the explanatory variable considered in the regression analysis.

5.2. EU Economy

For the 1999–2000 tightening cycle, the 3-month lag analysis offers a significantly different perspective compared to the contemporaneous results. While the initial regression and correlation analysis indicated a moderate positive relationship between the ECB Main Refinancing Rate and Eurostoxx 50 index, the lagged analysis reveals a sharp reversal. Specifically, the correlation coefficient falls to −0.76 (

Table 8), and the regression model shows a β estimate of −0.3 with an adjusted R

2 of 0.57 (

Table 9, model 1). These findings suggest that the apparent short-term alignment between Tightening and equity market gains masked underlying vulnerabilities, which materialized more clearly in early 2001. The deterioration in financial performance, therefore, appears to have followed the monetary policy tightening with a delay, likely influenced by the broader context of the bursting of the dot-com bubble and rising geopolitical tensions.

In contrast, the 2005–2007 tightening cycle demonstrates a higher degree of consistency and resilience under the same lagged framework. When a 3-month lag is applied, the positive relationship between the ECB policy rate and the Eurostoxx 50 remains robust. The correlation coefficient remains elevated at 0.93 (

Table 8), and the regression output continues to reflect a strong association, with an adjusted R

2 of 0.46 and a β1^ estimate of 0.34 (

Table 9, model 2). These results reinforce the interpretation of this period as a relatively successful soft landing, with equity markets maintaining a stable upward trajectory despite the delayed policy transmission. This consistency underscores the credibility of ECB policy actions during this cycle, as well as the supportive macroeconomic fundamentals in the pre-crisis years.

Correlation. This table illustrates the correlation for the 3-months’ time lag EU models between the dependent variable and the explanatory variable considered in the regression analysis.

5.3. Results

The inclusion of 3-month lag models as a robustness check meaningfully enriches the empirical framework of the study. In the 1999–2000 cycle, the lagged analysis revealed a sharp deterioration in equity performance, supporting the narrative that early signs of market instability emerged after a delay, possibly amplified by external shocks. In contrast, during the 2005–2007 tightening, the strong positive correlation and regression outcomes persisted even with the lag, underscoring the credibility and effectiveness of the ECB’s gradual policy normalization. These findings confirm that the observed relationships between monetary tightening and equity market performance are not artifacts of model timing, but reflect genuine economic mechanisms. The robustness checks thus add nuance and depth to the overall conclusions, reinforcing the validity of the main results.

6. The Contingent Economic Backdrop

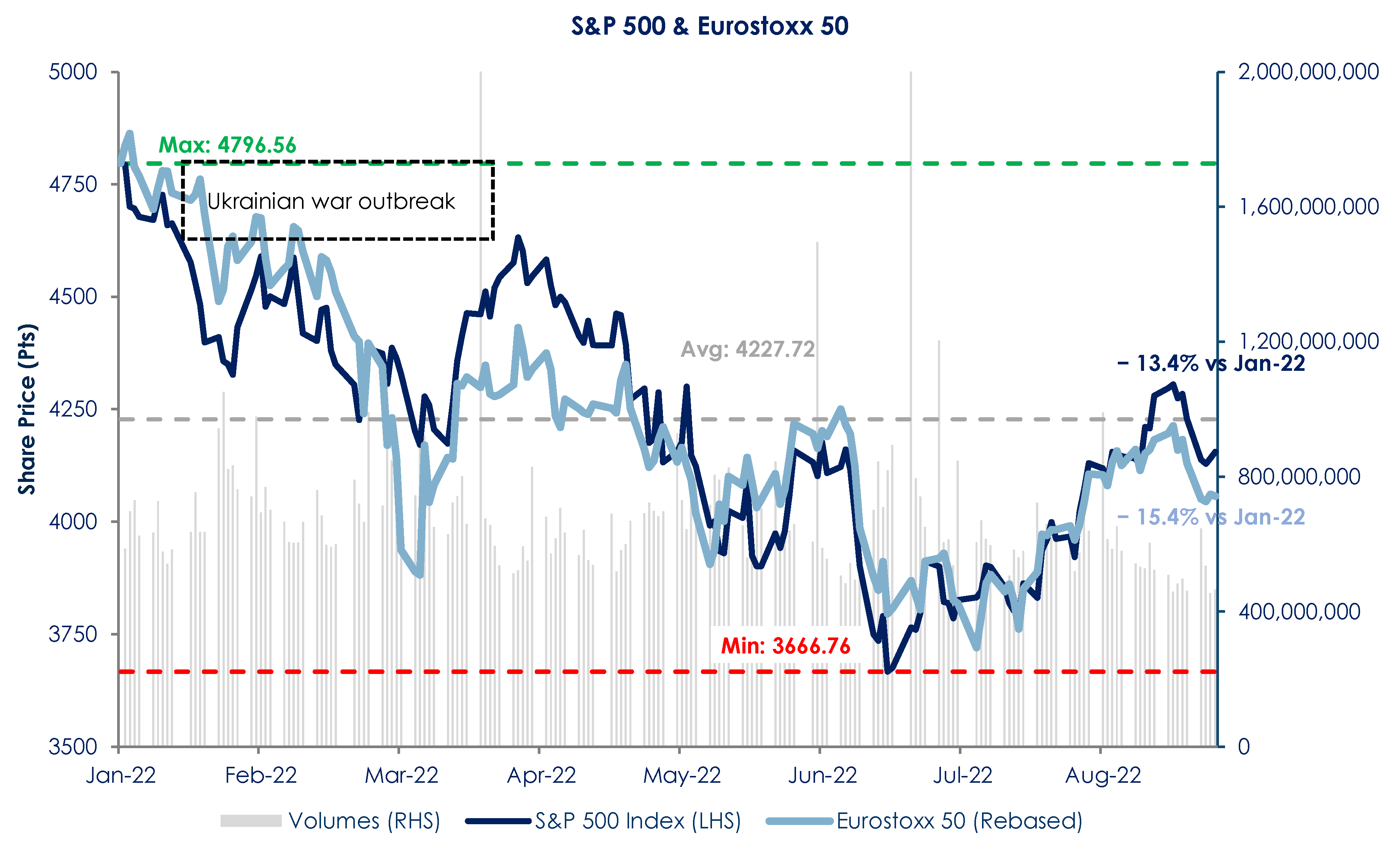

Once the tightening cycles are observed as having counteracted the inflationary pressures in the last 25 years, the analysis takes into account the contingent economic backdrop, to consider similarities and differences with the past, looking to both causes and effects of increasing inflation rate as well as Central Banks’ “reply”. Before assessing the impact on both the real economy and financial markets of the inflationary scenario which led Central Banks to set apart their prolonged accommodative policies, it is worth flagging the “genesis” of the current price instability. Indeed, inflation has been proceeding at a very fast pace in most of the advanced economies since the second half of 2021. By way of reference, in July 2022 one-year inflation rate was 8.5%, 10.1% and 8.9% in the US, United Kingdom and Eurozone, respectively. The first cause of the current inflationary scenario is related to the faster-than-expected “resurgence” from COVID-19 related headwinds, which came with inflation, buoyed by growing consumptions and investments which were muted during lockdowns (when households were in a sort of “savings” cycle), as well as accommodating policy from Central Banks. A second component had its starting-point in the supply sector, as it was related to microchips shortages amid production capacity constraints and consequent supply chain disruption, which resulted in bottlenecks in the supply of many goods (from electronics-computer sector to the automotive) and further inflation pressures. Finally, energy prices acted as third “character”. The upward trend of energy prices already started in 2021, but skyrocketing prices have been observed since the first quarter of 2022, exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which increased concerns of gas supply (Russia is the main supplier for European countries). It is worth noting that, among all the factors contributing to inflation both in the US and Europe, the main contributor has been representing by soaring energy prices. As a matter of fact, in the Eurozone the CPI index excluding energy items was 5.4% in July 2022, signaling an energy prices contribution of 3.5% (39% of inflation rate), while in the US the core CPI index (excluding energy and food items) was 5.9%, showing a contribution of 2.6% (31% of inflation rate). The analysis of the impact of current soaring inflationary pressures on financial markets starts from the equity capital markets, which is an adequate representative indicator of the financial backdrop. As observed in

Figure 3, both the S&P 500 and Eurostoxx 50 indexes have shown a similar steady downward trend since the beginning of 2022, amid a deteriorating economic environment on the back of inflationary pressures both in Europe and the US.

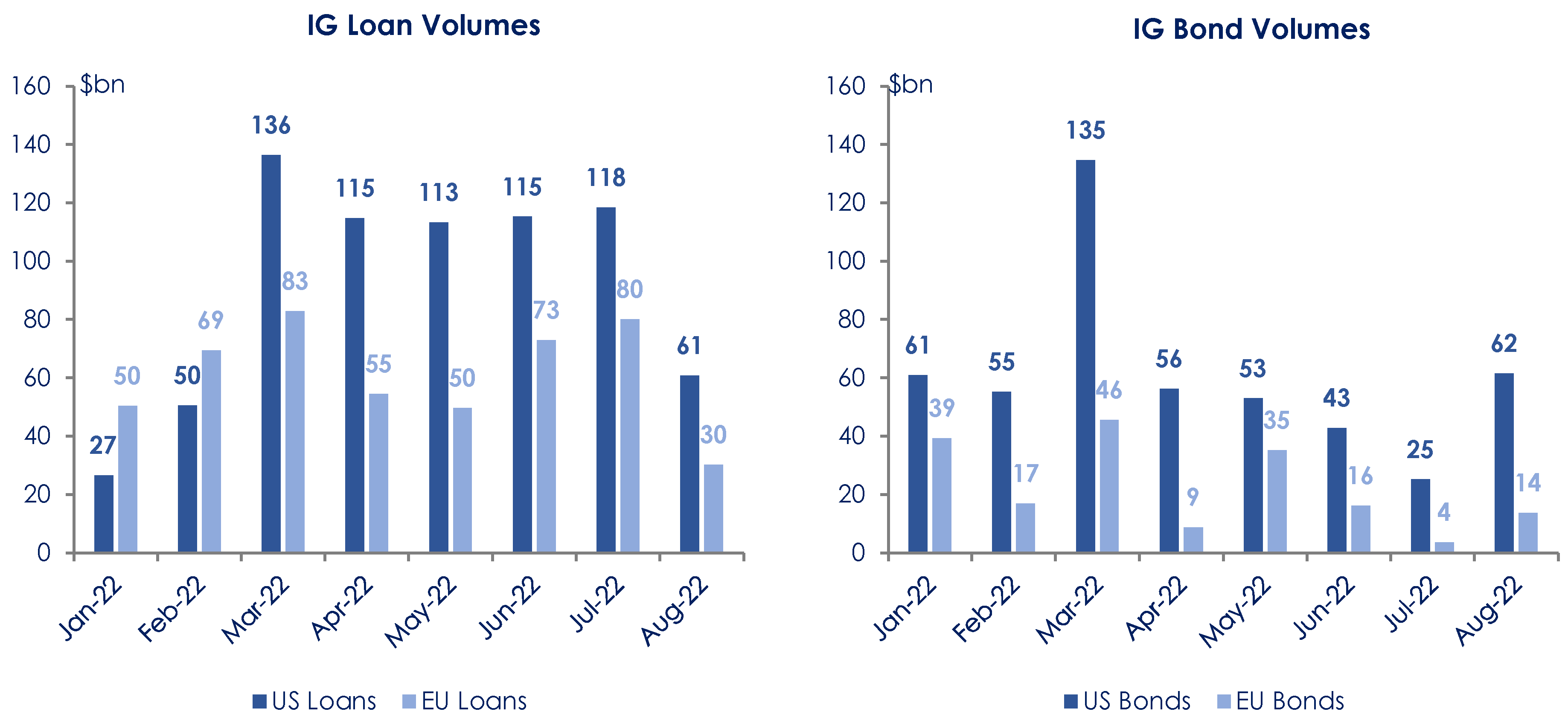

It is worth flagging that equity indexes (especially Eurostoxx 50) suffered a significant drop between late February and early-March due to the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, even if the losses were mostly retraced in the following weeks. However, in the last months, the lack of positive and crucial news regarding the Ukrainian war has clearly shifted the focus on inflation, economic growth and Central Banks’ decisions. In particular, in June both indexes experienced another slump, mainly related to concerns on macro headwinds, as downward economic growth expectations in all the advanced economies “evoked” the nightmare of stagflation, considering the continued increase in prices. On the other hand, in the last weeks, encouraging headline-grabbing news reported from US regarding still growing wages and real GDP growth (which rose 0.3% in the second quarter), easing fears regarding the “hard-landing” nature of the contingent tightening cycle, even if uncertainties persist. By way of reference, as of end of August 2022, S&P 500 and Eurostoxx 50 dropped by 13.4 and 15.4% versus the value which was observed at the beginning of January 2022. With respect to the corporate debt trends amid recent and persisting macro headwinds, it is worth outlining the different impact on public debt rather than private syndicated loans market (

Figure 4).

Indeed, price instability effects were more and more evident in the public space, where bond volumes recognized a steady downward path both in the US and European markets, following broader volatility in financial capital markets. The significant reduction in bond volumes, which resulted in a true market dislocation in Europe, was mainly related to the widening trajectory observed in final terms required from bondholders as a consequence of the market risk they had to bear. As a matter of fact, a general worsening in the credit space has been observed since the beginning of the year, also exacerbated by Ukrainian war outbreak. The most impacted are the Materials, Utility and Consumer sectors, where, considering the huge exposure to cost increases, credit spreads have been increased by c.50 bps, c.45 bps and c.30 bps, respectively. On the other hand, the more resilient private debt market has remained quite insulated from market volatility, as outlined by steady huge volumes and the lack of any repricing. In other words, considering the debt capital markets dislocation, most of the borrowers have relied on banks’ liquidity to meet their needs since March 2022, resulting in a strong increase in loans volumes (both in US and Europe). In this context, the role of banks as financial intermediaries becomes particularly relevant. When capital markets became unstable and expensive, particularly in the public debt segment, firms increasingly turned to banks for funding, reinforcing the traditional “bank lending channel” of monetary policy transmission. According to the 2022 ECB’s Bank Lending Survey, demand for bank loans significantly increased during the first half of 2022. The

BIS (

2022) and

IMF (

2022) also highlight how banks, entering the post-pandemic tightening cycle with robust capital and liquidity positions, were able to act as shock absorbers—sustaining credit flows to corporates and households even as monetary policy tightened. This intermediation buffer was especially critical in Europe, where leveraged finance markets effectively shut down following the outbreak of the Ukraine war (

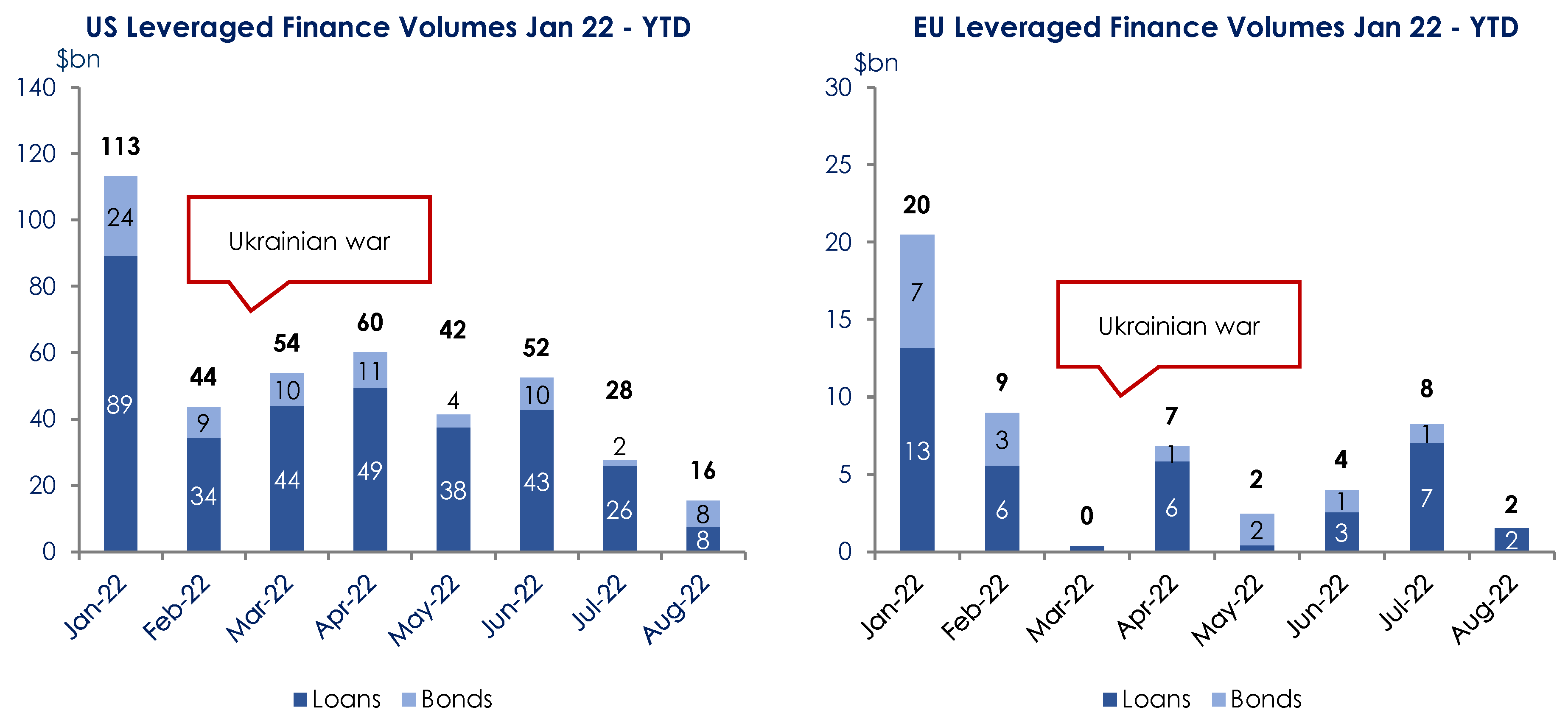

PitchBook LCD, 2022). European banks ended up carrying c.€10 bn of underwritten deals on their balance sheets by September 2022, and their willingness to continue lending privately became central to the financial stability of the corporate sector. The persistence of such bank lending activity has helped mitigate the risk of a “hard landing” in credit supply, especially in sectors that are most exposed to inflation and supply chain disruptions.

Going forward, considering the expected persisting broader volatility in public debt capital markets (in Italy, in particular, it is also exacerbated by political instability related to the new government election at the end of September 2022), it is likely that borrowers will continue to knock on the banks’ desk to satisfy their financial requirements. Without any doubt, HY debt markets (both public and private) suffered a huge market dislocation, amid macro headwinds on the back of inflationary pressures and growing fears over recession, whose effect’s magnitude is clearly higher for companies with a lower credit rating. In particular, the massive impact of the contingent weak backdrop is evident both on new issuance volumes (following a steady decrease in LBO) and the wide repricing path observed in the few new HY bonds and loans allocated in the last months. In particular, repercussions were more evident in the European space, where the leveraged finance activity was completely muted in March (after the Ukrainian war outbreak) while in the US, where markets have shown more accommodating conditions despite economic turmoil, activity recognized a significant slowdown but doors to new primary supply have remained always open.

As outlined in

Figure 5, looking at the volumes’ breakdown between bonds and loans, it is worth flagging that, in the US, leveraged finance activity remained well sustained by loan issuances while debt capital markets experienced a substantial slowdown, with only few issuances in the last six months. Instead, in Europe, especially after the outbreak of the Ukrainian war, new primary supply collapsed and remained almost silent in the 2Q2022, in both the public and private space. Despite a tentative rebound in April when some borrowers managed to successfully price their finances in a temporary positive window, market conditions further deteriorated in June, following a persistently volatile environment on the back of negative news on the expected growth path (in line with the above-mentioned equity trend) and a weak secondary backdrop. However, in the last weeks, a better technical support should help to ensure supportive conditions for a return of primary loan issuances in mid-September. However, the market is still faltering amidst persisting macro headwinds and recession fears: volumes are still very “thin” and future issuances will depend on investors’ appetite and overall market sentiment. Furthermore, as of September 2022, banks still have c. €-eq. 10 bn of underwritten deals on their balance sheets and this could lead, in Europe, to an attempt of market reopening in the loan rather than HY bonds space, as banks are focusing on clearing the risk. Assessing the widenings in pricing terms, in the leveraged loan space, the few transactions priced in the last months implied hefty discount and accommodating margin amid the broader market volatility investors have to bear. By way of reference, the upward path in pricing terms has materialized in a c.75–100 bps increase in margin (depending on the credit status of the borrower, size of the financing and the split between new and old money) and the OID discount in the 92–95 range, vis-à-vis 97–98 levels which were observed in clearing market conditions. Finally, trying to assess the possible outcome of the ongoing tightening, despite it being premature to draw a “soft” or a “hard-landing” scenario under current circumstances, different shades of recession have been labeled by economists dusting off their old books in attempting to describe the present macro backdrop. Calling it “Anti-Goldilocks” (where inflation gets too hot and growth gets too cold) or “Growth recession” (a protracted period of meager growth, but shorter than an outright contraction), the market consensus shares the view of a mini-recession in Q3/Q42022, where together with interest rate risk premium, almost already priced in current yield levels, earning risk premium—due to lower margins and expensive debt—also needs to be factored in valuations, leading to poor credit and equity performance into the year end. With regard to 2023 perspectives, normalization of the rates adjustment of the Central Banks once inflation peaks and of supply-demand imbalances (after the contraction of late 2022) should give some respite to world economy. A stagflation scenario (persistent inflation and high unemployment) is not on the cards at the moment as Central Banks are firmly committed to fight lasting inflation as well as labor market remains in good shape with lay-offs easily absorbed.

7. Conclusions

This paper contributes to the existing literature by shifting the analytical focus from real economic activity to financial markets when assessing the outcomes of monetary tightening cycles. While the macroeconomic response remains a primary lens to evaluate central bank effectiveness, financial markets increasingly serve as forward-looking indicators and transmission channels—particularly the bond market, which plays a pivotal role in interest rate pass-through and expectations.

The paper distinguishes itself by offering a broad and integrated perspective, examining both equity and debt markets, across different credit classes—from investment grade to high-yield and leveraged segments. In addition, the inclusion of both U.S. and European economies highlights not only the synchronicity of central bank policies but also the temporal lag in the ECB’s policy implementation compared to the Fed.

Empirical findings suggest that, over the last three decades, central banks have generally succeeded in engineering soft landings. The U.S. tightening episodes of 1994–1995 and 2017–2019 stand out as examples where inflation was contained without derailing growth, as evidenced by strong equity performance and declining spreads. In contrast, the pre-crisis hikes of the early 2000s and 2006–2007, while followed by recessions, were not themselves the direct causes of those downturns. In both cases, financial markets and real activity remained resilient during the rate hikes, and the recessions were primarily triggered by asset bubbles rather than monetary policy missteps.

However, the current tightening cycle poses unique challenges. The inflation surge post-COVID is entangled with structural shifts such as energy price volatility, supply chain realignment, and the uncertain impact of green transitions and deglobalization. These elements distinguish the present scenario from past episodes and limit the applicability of standard policy rules.

In addition, regulatory and political dimensions introduce further uncertainty into the monetary policy landscape. On the regulatory front, evolving capital requirements (e.g., Basel III/IV), the treatment of sovereign exposures, and changes to liquidity coverage ratios can alter the responsiveness of banks and institutional investors to rate hikes, weakening or amplifying transmission. Politically, central banks now operate in increasingly polarized environments, where policy decisions are scrutinized for their social and distributional effects—particularly around housing affordability, labor market dynamics, and fiscal-monetary coordination. These pressures may constrain policy space or delay responses, adding a layer of ambiguity to already complex dynamics.

Looking forward, our analysis introduces the concept of a “two-step landing.” The economy may undergo a short-lived but intense correction—a hard phase—followed by a slower, more stable recovery phase resembling a soft landing. This hybrid scenario suggests that central banks must maintain strategic flexibility and clear communication to navigate complex macro-financial dynamics without oversteering.

Policy implications include the importance of the following:

Monitoring market-based indicators alongside macro data;

Avoiding prolonged accommodative stances that fuel asset bubbles;

Anticipating asymmetric effects of tightening across credit segments;

Recognizing lag structures in transmission across regions.

In sum, the paper underscores the need to refine our understanding of monetary tightening outcomes through a financial lens, advocating for more nuanced assessments in both academic and policy frameworks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G. and F.P.; methodology, G.G., F.P. and F.S.; software, G.G. and F.P.; validation, G.G., F.P. and F.S.; formal analysis, G.G., F.P. and F.S.; investigation, G.G., F.P. and F.S.; resources, G.G., F.P. and F.S.; data curation, G.G., F.P. and F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G. and F.P.; writing—review and editing, G.G., F.P. and F.S.; visualization, G.G., F.P. and F.S.; supervision, G.G., F.P. and F.S.; project administration, G.G.; funding acquisition, G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This objective function is typically accepted in models because it is adaptable to the mandate of many Central Banks ( Woodford, 2002). |

| 2 | An alternative formula substitutes the unemployment rate u with the economic output y. |

| 3 | 1% increase does not mean an increase of 100 bps in interest rates. By way of clarity, starting from a value of 1% set by Central Bank, a 1% increase corresponds only to 1 bps. |

References

- Athey, S., Atkeson, A., & Kehoe, P. (2005). The optimal degree of monetary policy discretion. Econometrica, 73(5), 1431–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank for International Settlements. (2022). Annual economic report 2022: Chapter I—Old challenges, new shocks. Bank for International Settlements. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, R. J., & Gordon, D. B. (1983). A positive theory of monetary policy in a natural rate model. Journal of Political Economy, 91(4), 589–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernanke, B. S., & Kuttner, K. N. (2005). What explains the stock market’s reaction to federal reserve policy? Journal of Finance, 60(3), 1221–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinder, A. S. (2022). Landings hard and soft: The fed, 1965–2020 (Working paper). Princeton University. Available online: https://bcf.princeton.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Transcript-1.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Clarida, R., Gali, J., & Gertler, M. (2000). Monetary policy rules and macroeconomic stability: Evidence and some theory. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(1), 147–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, M., & Karadi, P. (2015). Monetary policy surprises, credit costs, and economic activity. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 7(1), 44–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürkaynak, R. S., Sack, B., & Swanson, E. T. (2005). Do actions speak louder than words? The response of asset prices to monetary policy actions and statements. International Journal of Central Banking, 1(1), 55–93. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund. (2022). Usability of bank capital buffers: The role of market expectations (IMF Working Paper No. 22/021). IMF. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, A., & Reis, R. (2005). Understanding the Greenspan standard (pp. 11–96). Princeton University, Center for Economic Policy Studies. [Google Scholar]

- PitchBook LCD. (2022). 2022 Leveraged Commentary & Data (LCD): Leveraged loan primer. PitchBook. Available online: https://pitchbook.com/news/reports/2022-leveraged-commentary-data-lcd-leveraged-loan-primer (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Rigobon, R., & Sack, B. (2004). The impact of monetary policy on asset prices. Journal of Monetary Economics, 51(8), 1553–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, L. E. O. (2001). Independent review of monetary policy in New Zealand: Report to the minister of finance. Institute for International Economic Studies, Stockholm University. Available online: https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/-/media/755b1eabb63a481f847bbac5dc55d5bd.ashx?sc_lang=en (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Woodford, M. (2002). Inflation stabilization and welfare. Contributions to Macroeconomics, 2(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).