1. Introduction

Exchange rates are pivotal economic indicators, reflecting a nation’s financial health and macroeconomic stability (

Avetisyan, 2020). This is the case in South Africa, where the exchange rate between the Rand and various major currencies is a significant barometer for the country’s economic performance and global competitiveness (

Chen et al., 2022). Further, South Africa’s status as an emerging market renders its currency particularly sensitive to global financial risk sentiment, particularly during heightened uncertainty (

Choi & Goh, 2013). Elevated global risk sentiment, indicating market-wide fear and uncertainty, often triggers capital flight from riskier assets, a phenomenon termed flight-to-quality, leading to currency depreciations in emerging markets such as South Africa. The recent financial crisis and the pandemic are a testament to this phenomenon (

Mpofu, 2021).

South Africa’s substantial reliance on commodity exports exposes its currency to significant commodity price volatility (

Chen et al., 2022). Rising commodity prices bolster South Africa’s foreign exchange reserves, leading to an appreciation of the Rand by improving the country’s trade balance and economic stability. However, a decline in commodity prices, often driven by changes in global demand, geopolitical tensions, or financial market uncertainties, directly and significantly impacts the exchange rate (

Moyo & Mlambo, 2020). These dynamics underline the intricate linkage between South Africa’s mining sector and its currency, highlighting both the opportunities and risks tied to global commodity price movements. Furthermore, the reliance on volatile commodity markets necessitates robust macroeconomic policies to buffer against sudden price swings and ensure financial stability.

Another potent factor influencing the Rand is its susceptibility to interest rate differentials, which amplifies the impact of monetary policy shifts in advanced economies (

Chen et al., 2022). Changes in interest rates in developed markets often trigger capital flow adjustments as investors seek higher yields, leading to fluctuations in the Rand’s value (

Itskhoki & Mukhin, 2021). This phenomenon is especially pronounced during periods of monetary tightening by central banks in advanced economies, as higher global rates reduce the yield advantage of holding emerging market currencies due to their inherent risks, including heightened volatility, susceptibility to political instability, and lower credit rating effects (

Baffes et al., 2015). With the constantly increasing interconnectedness of markets, the challenges of managing exchange rate volatility in a highly integrated global monetary system may increase substantially.

The interplay of global risk sentiment, commodity price volatility, and interest rate differentials can amplify their combined impact on the country’s currency, creating a melting pot of uncertainty for South Africa’s exchange rate. For example, during periods of heightened global risk sentiment, falling commodity prices can coincide with monetary tightening in advanced economies, leading to simultaneous capital outflows and declining export revenues (

Goyal & Pal, 2022). In another instance, a surge in commodity prices driven by factors such as geopolitical tensions might temporarily strengthen the Rand, only for this gain to be undermined by adverse shifts in monetary policies or sentiment (

Juvenal & Petrella, 2024). Such scenarios intensify exchange rate pressure, as complex and dynamic interactions between these factors create feedback loops that destabilise the currency.

Yet most studies tend to examine the impact of global risk sentiment (

Shang & Hamori, 2021), commodity price volatility (

Zhang et al., 2016), and interest rate differentials (

Şen et al., 2020) on the exchange rate in isolation, overlooking their intricate interactions that can significantly amplify their combined effects. As such, policy interventions based on a singular factor approach may fail to address the full extent of exchange rate volatility. This represents the gap this study sought to address, employing the autoregressive distributed lag model to capture both short-term and long-term dynamics. For a country like South Africa, this is a critical gap to address, as failure to account for these interactions in macroeconomic and monetary policy frameworks could exacerbate economic instability, erode investor confidence, and limit the effectiveness of measures aimed at stabilising the already sensitive currency.

In essence, this study aimed to empirically analyse the impact of global risk sentiment, global gold prices, and interest rate differentials on the Rand/Dollar exchange rate. This study utilised an autoregressive distributed lag model in order to capture both short-term fluctuations and long-term equilibrium effects. Given South Africa’s status as an emerging market on the African continent, its currency is susceptible to external shocks, making it crucial to understand how these factors interact over different time horizons. This study tested three key hypotheses: (H1) higher global risk sentiment leads to short-term Rand depreciation due to capital outflows; (H2) rising gold prices strengthen the Rand by improving trade balances, with both short- and long-term effects; (H3) a widening interest rate differential in favour of South Africa attracts capital inflows, supporting Rand appreciation.

The results from this analysis could provide valuable insights for policymakers, investors, and financial analysts by enhancing the understanding of key macroeconomic drivers influencing exchange rate movements. A more precise grasp of how global risk sentiment, gold prices, and interest rate differentials interact could help improve monetary policy decisions, inform risk management strategies, and guide foreign exchange interventions. Additionally, these insights could support macroeconomic planning by highlighting the need for economic diversification and policy adjustments to mitigate vulnerabilities of the exchange rate associated with external shocks. Given South Africa’s exposure to global market dynamics, this study’s findings could contribute to more resilient financial policies and better exchange rate stability in an increasingly volatile global economic environment.

2. Literature Review

The theoretical framework for this study is anchored in two fundamental approaches: the portfolio balance approach and the risk premium theory. The portfolio balance approach posits that exchange rates are shaped by the flow of capital between countries. During heightened global risk sentiment, investors typically reallocate their portfolios towards safer assets, such as those in the US denominated in the US dollar, resulting in capital outflows from emerging markets. This movement leads to a depreciation of currencies like the South African Rand as investors seek refuge in lower-risk options (

Sachs, 1991). Consequently, in times of global uncertainty, the ZAR is prone to significantly losing its value against the US dollar due to the perceived higher risk of Rand-denominated assets and the resultant reduced attractiveness of the Rand as an investment currency.

The risk premium theory complements this perspective by highlighting the pivotal role of perceived currency risk in shaping exchange rates. As global risk sentiment heightens, the risk premium associated with emerging market currencies, such as the ZAR, rises sharply. This elevated premium reflects the additional compensation investors require for holding assets denominated in riskier currencies, leading to further depreciation of these currencies (

Menkhoff & Scholtus, 2012). This theory is especially relevant for South Africa, given the ZAR’s pronounced sensitivity to external shocks, including global financial crises, global commodity price fluctuations, and broader global economic instability and uncertainty. These vulnerabilities underline the critical impact of risk perception on the ZAR’s value in an interconnected global financial system.

Together, these theoretical approaches offer a powerful lens to unravel the complex dynamics of exchange rates. They illuminate the intricate interplay between global financial risks, including heightened market uncertainty and shifting risk sentiment, and macroeconomic forces, such as gold prices and interest rate differentials, which collectively influence exchange rate movements. Due to how they provide complementary insights, integrating their perspectives, this study aims to capture the multifaceted and interconnected drivers of the ZAR’s behaviour, offering a comprehensive understanding of how external shocks and domestic economic factors interact. In doing so, it provides valuable insights into the ZAR’s susceptibility to volatility and its position within the broader, ever-evolving global financial landscape.

The relationship between exchange rates and commodity prices has been the subject of extensive research over the years, with studies uncovering diverse dynamics. For instance,

Chipili (

2015) found a long-run equilibrium between copper prices and the Kwacha/US dollar exchange rate in Zambia, highlighting the importance of copper in shaping the country’s economic performance.

Rezitis (

2015) found significant bidirectional causality between agricultural commodity prices and the US dollar exchange rates, indicating a highly interconnected relationship.

Coudert et al. (

2015) advanced this understanding by demonstrating a nonlinear relationship between terms of trade and real exchange rates in commodity-producing countries, with short-term sensitivities particularly pronounced in advanced oil-exporting economies during periods of high market volatility.

Zhang et al. (

2016) showed that commodity prices more strongly influence exchange rates than vice versa, especially in the short term, highlighting macroeconomic and trade-based mechanisms.

Poncela et al. (

2017) linked rising commodity prices in Colombia to real exchange rate appreciation, evidencing Dutch disease and industrial competitiveness challenges.

Kohlscheen et al. (

2017) demonstrated that commodity prices significantly influence short-term exchange rate movements, outperforming random walk models in forecasting.

Zou et al. (

2017) emphasised the role of commodity prices in improving exchange rate forecasting, particularly for commodity-exporting nations shifting to floating regimes.

Boubakri et al. (

2019) found that low financial integration amplifies the impact of real commodity price volatility on real effective exchange rates.

Salisu et al. (

2019) showed how accounting for structural breaks and asymmetries improves exchange rate predictability using commodity prices.

Siami-Namini (

2019) further revealed that crude oil price volatility has significant post-crisis effects on exchange rates.

Butt et al. (

2020) examined Malaysia’s exchange rate and commodity price nexus, identifying asymmetric adjustments and bidirectional causality, while

Kassouri and Altıntaş (

2020) documented the asymmetric impacts of terms of trade shocks on REER in African commodity-exporting countries.

Sokhanvar and Bouri (

2023) provided evidence of commodity price shocks caused by the Ukraine war, highlighting the appreciation of the Canadian Dollar and the depreciation of the Euro and Yen, showing the differential impacts on exporters and importers.

The influence of market sentiment on exchange rates has also gained increasing attention, with studies demonstrating its potential as a valuable predictive tool. For instance,

Plakandaras et al. (

2015) found that investor sentiment, derived from StockTwits data, provides significant predictive power for exchange rate movements, suggesting that sentiment analysis complements traditional economic models. Similarly,

Bulut (

2017) showed that Google Trends data outperformed structural models and traditional fundamentals in forecasting exchange rate directions, particularly post-Great Recession, reinforcing the role of sentiment indicators in enhancing predictive accuracy.

Yasir et al. (

2019) proposed a deep-learning model incorporating event-based sentiment and macroeconomic factors, achieving superior accuracy in forecasting exchange rates for three currency pairs.

Shang and Hamori (

2021) analysed crude oil prices and a sentiment index, finding that sentiment acts mainly as a reactive factor in exchange rate dynamics during volatile periods. Similarly,

Hoang and Syed (

2021) noted that traditional sentiment metrics, like the VIX, lose predictive power during crises, highlighting the distinct nature of fear sentiment during unprecedented events. Further insights are provided by

Sibande et al. (

2021), who investigated herding behaviour in currency markets using Twitter-based sentiment proxies. The study found that extreme investor sentiment, particularly in bullish states, intensifies anti-herding behaviour, suggesting that real-time sentiment signals are effective for monitoring speculative activities. These findings align with behavioural asset pricing models, showcasing the evolving role of sentiment in foreign exchange markets.

The third group of studies examined the relationship between interest and exchange rates, revealing interesting dynamics that vary across economic and regional contexts. In this regard,

Tafa (

2015) examined how changes in interest rates on Albanian lek deposits influenced the exchange rates of USD/ALL and EUR/ALL. The findings revealed contrasting outcomes: an increase in interest rates led to the depreciation of the ALL against the USD but an appreciation against the EUR. This highlights the complexity of these dynamics and the necessity for context-specific policies to manage such dynamics. Similarly,

Ramasamy and Karimi (

2015) found that while interest rates are significant drivers of exchange rate movements, psychological factors such as investor confidence often override economic fundamentals, leading to unexpected currency behaviours.

Du et al. (

2018) identified systematic and persistent covered interest rate parity deviations in major currency markets, strongly linked to banking regulations, particularly during quarter-end periods when regulatory pressures on bank balance sheets intensify. Evidently, regulatory environments are crucial in shaping exchange rate behaviour. Furthermore, these covered interest rate parity deviations were found to be significantly correlated with nominal interest rates and fixed-income spreads, revealing how macroeconomic indicators and regulatory factors jointly influence exchange rate movements.

Engel et al. (

2019) explored the uncovered interest parity puzzle, showing that US inflation, rather than interest rate differentials, is a better predictor of short-term exchange rate changes. This challenges traditional uncovered interest parity models.

Şen et al. (

2020) used threshold cointegration methods to examine long-term relationships among interest rates, inflation, and exchange rates in the Fragile Five economies. They found a positive long-run relationship between interest rates and exchange rates in Brazil, India, and Turkey, but not in Indonesia and South Africa. This suggests that structural differences affect how interest rates influence exchange rates.

Hashchyshyn et al. (

2020), through a meta-analysis of 30 countries, concluded that policy interest rate changes have a significant short-term impact, leading to currency appreciation, although the long-term relationship appears weak. Meanwhile,

Kataria and Gupta (

2018) highlighted that policy interest rates contribute positively to real effective exchange rates in emerging markets and that domestic factors like GDP growth play a complementary role.

Of note, while the literature provides insights into exchange rate determinants, much of it is based on more developed markets or some structurally distinct emerging markets, limiting its relevance to South Africa’s unique macroeconomic environment. The Rand’s volatility is influenced not only by traditional economic fundamentals, as may be the case in other countries, but also by global risk sentiment, gold price fluctuations, and monetary policy shifts in advanced economies. Unlike the economies studied by

Chipili (

2015) and

Rezitis (

2015), South Africa’s strong reliance on gold exports heightens its exchange rate sensitivity to commodity price volatility. Similarly,

Şen et al. (

2020) found that interest rate differentials play a weaker role in South Africa, likely due to capital flow volatility and investor sentiment shifts rather than interest rate-driven arbitrage alone.

Moreover,

Bulut (

2017) and

Yasir et al. (

2019) emphasise the role of sentiment in exchange rate fluctuations, but South Africa’s exchange rate is further impacted by speculative trading and carry trade strategies, which are not as prevalent in other emerging markets. These factors highlight the need for a localised, integrated analysis. This need is heightened by the realisation that most past studies have analysed global risk sentiment, commodity price movements, and interest rate differentials in isolation, leaving a significant gap in understanding their combined effects on the Rand/USD exchange rate. While prior studies such as

Frankel (

2007) and

Hsing (

2016) have explored determinants of the Rand, they primarily focus on individual macroeconomic drivers rather than their interactive and time-dependent influences.

This study addresses that important gap by explicitly asking: “How do global risk sentiment, gold prices, and interest rate differentials collectively influence the Rand/USD exchange rate over different time horizons?” This question is particularly important given the increasing financial integration of emerging markets, the volatility in global capital flows, and the rising frequency of external shocks that simultaneously affect exchange rate stability. Understanding these interactions is crucial for designing effective monetary policies and risk management strategies that enhance currency resilience. To answer this critical question, this study employs the autoregressive distributed lag model, a robust technique suited for analysing both short-term fluctuations and long-term equilibrium relationships while accounting for dynamic adjustments in exchange rate movements.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data and Variables

This study utilises monthly time-series data spanning from 2005 to 2023, a period specifically selected to capture the effects of major global financial events, such as the 2008 global financial crisis, the European sovereign debt crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic. These events triggered sharp fluctuations in global risk sentiment, commodity prices, and interest rate differentials, making them particularly relevant for understanding their impact on exchange rate dynamics in emerging markets. By incorporating both periods of stability and high volatility, this timeframe allows this study to assess how external shocks influence the South African Rand over different economic conditions. The extended dataset ensures that the analysis captures both short-term exchange rate adjustments and long-term equilibrium relationships, enhancing this study’s ability to provide a comprehensive empirical assessment.

The South African Rand/US Dollar exchange rate serves as the dependent variable, reflecting the value of the South African Rand relative to the US Dollar. This measure, sourced from the South African Reserve Bank (SARB), is a widely recognised indicator of South Africa’s macroeconomic stability and its exposure to external economic shocks. As an emerging market currency, the Rand is particularly sensitive to global financial conditions, making it an ideal subject for investigating the interplay between global risk sentiment, commodity price fluctuations, and monetary policy shifts. This study’s focus on this exchange rate provides insights into how external market forces and domestic economic policies influence South Africa’s currency performance, contributing to a broader understanding of exchange rate volatility in emerging economies. Given that the US dollar dominates global trade and financial transactions, this exchange rate pairing is particularly relevant for policy and investment decision-making.

Global risk sentiment, proxied by the volatility index (VIX) sourced from the Fed of St Louis, serves as a key independent variable in the analysis. The VIX is widely recognised as a sentiment-based measure of market uncertainty and investor fear, influencing capital flows between developed and emerging markets. Higher VIX levels signal increased market uncertainty, often leading to capital flight from riskier assets like the Rand toward safe-haven currencies, such as the US dollar. The use of VIX as a sentiment factor is well supported by empirical research, including

Qadan and Yagil (

2012), who demonstrate that fear sentiment, as measured by the VIX, exhibits strong causality relationships with asset price fluctuations, including gold prices. This aligns with the existing literature that identifies investor sentiment as a primary determinant of exchange rate volatility in emerging markets, reinforcing the importance of incorporating VIX in assessing the impact of global financial uncertainty on the Rand/USD exchange rate.

Gold prices and interest rate differentials are also essential independent variables, reflecting fundamental aspects of South Africa’s economic structure. Gold prices, sourced from the World Gold Council, capture South Africa’s reliance on gold exports as a major foreign revenue source. Given this reliance, fluctuations in gold prices can have direct and measurable effects on the Rand, with rising gold prices often leading to currency appreciation due to improved trade balances and enhanced investor confidence. Interest rate differentials, calculated as the difference between nominal South African and US interest rates, and sourced from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) database, serve as a proxy for capital flow dynamics. The use of nominal rather than real interest rate differentials aligns with prevailing research by

Frankel (

2007) and

Hsing (

2016), which suggests that investors respond primarily to nominal yields when making cross-border investment decisions rather than adjusting for inflation differences in real terms. A higher nominal interest rate differential in favour of South Africa attracts foreign investment, strengthening the Rand, whereas a narrowing or negative differential reduces the currency’s attractiveness, leading to depreciation pressures. These variables are among the most widely recognised exchange rate determinants in emerging markets, providing a robust empirical basis for this study.

Certain macroeconomic factors—such as fiscal policies, political risk, and trade balances—were excluded to maintain model parsimony and avoid overfitting. While these factors can influence exchange rate movements, their effects are often indirect and more difficult to quantify in time-series models. Moreover, including too many explanatory variables risks introducing multicollinearity, which can distort results in the ARDL framework. Future research could explore additional macroeconomic indicators, such as investor confidence, domestic inflation volatility, and external debt levels, to refine exchange rate modelling. However, the selected variables—global risk sentiment, gold prices, and interest rate differentials—are widely recognised in the literature as primary drivers of emerging market exchange rates. By focusing on these key factors, this study ensures a clear, quantifiable, and policy-relevant analysis of exchange rate dynamics.

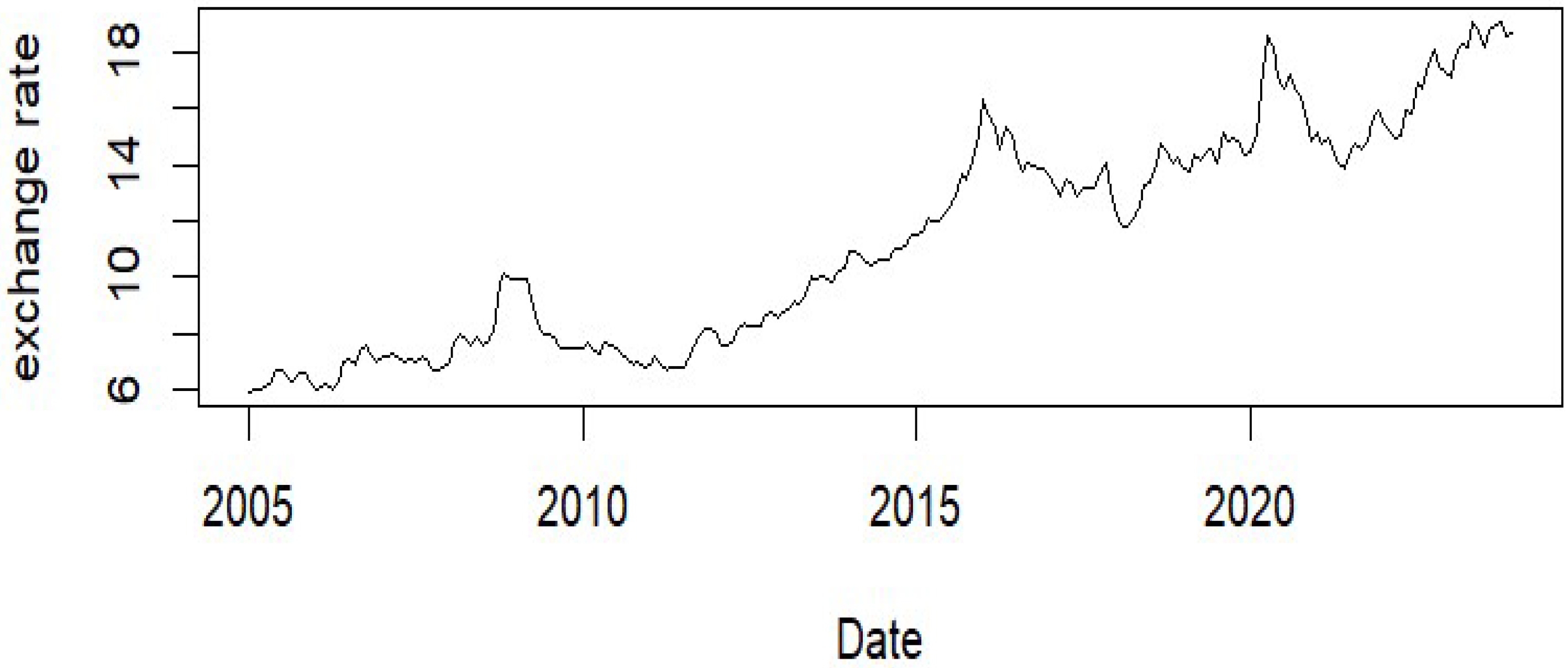

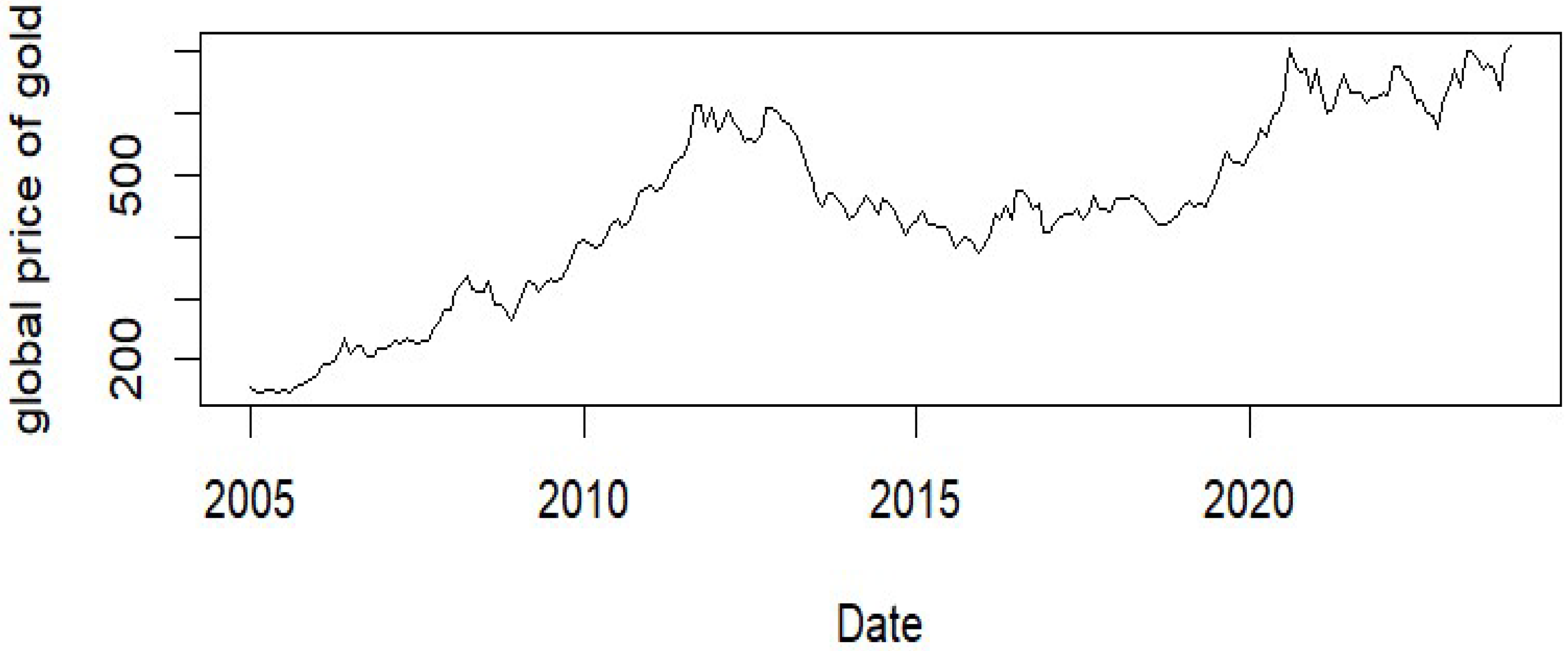

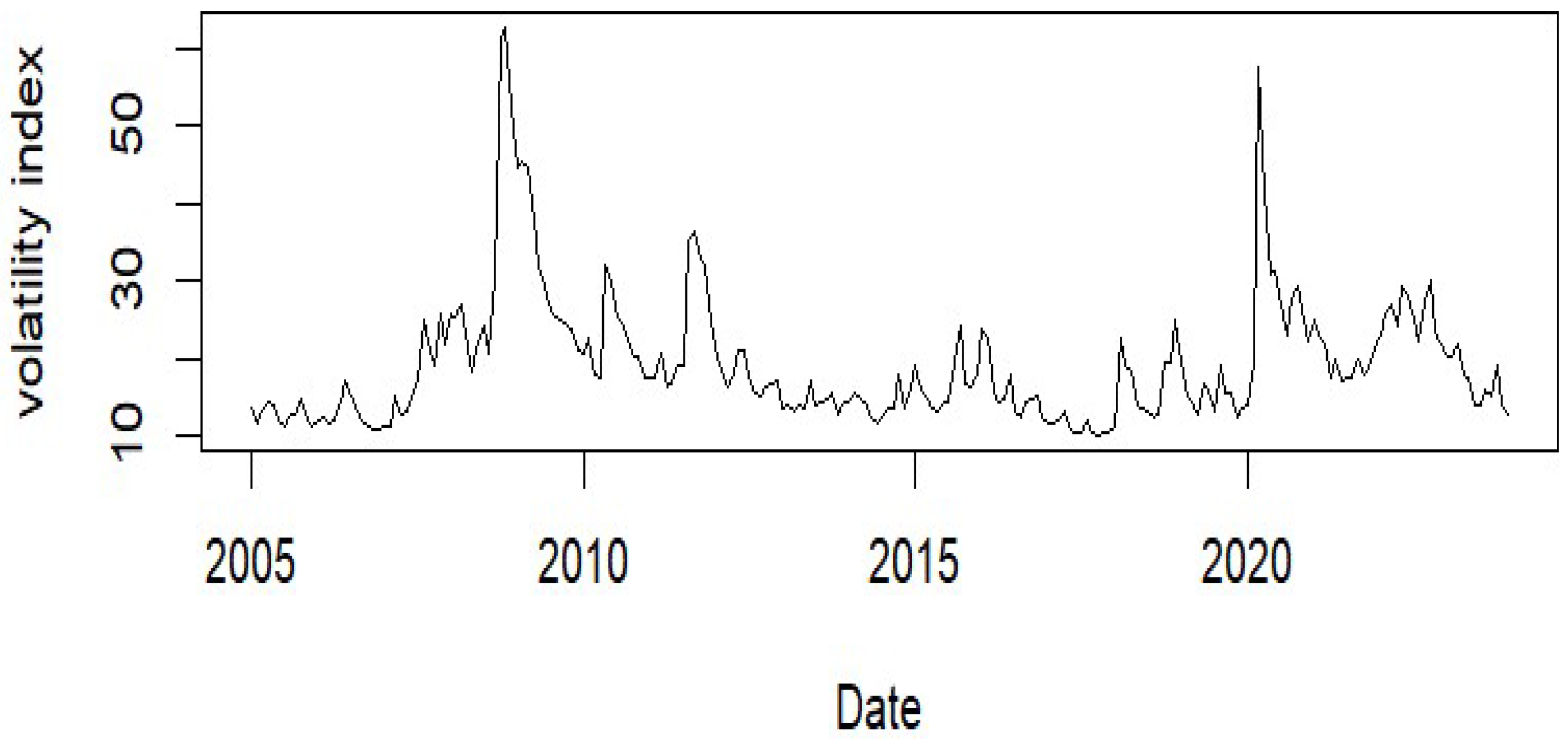

The following diagrams show the historical behaviour of the variables.

Figure 1 shows that the exchange of the South African Rand against the United States American Dollar has remained on a constant depreciation swing. In the early 2000s, the exchange rate was relatively stable. Then, towards the end of 2007, there was a spike in depreciation, which remained until 2009. Thereafter, the exchange rate improved until the end of 2011. Following this period, the exchange rate depreciated rapidly towards 2013. In the period between 2013 and 2020, the exchange rate moderated, then spiked after 2020. Thereafter, the exchange rate remained on a continuous depreciation trajectory.

The price of gold shows an upward trajectory, as expected. Since gold is used to hedge against tough economic times, during economic turmoil, the price of gold increases, whereas in good economic times, it tends to fall. In

Figure 2, from the beginning of the sample period, the price of gold appears more stable. Then, from about the end of 2006 to 2007, the price of gold increased rapidly. Thereafter, the slope becomes relatively flatter. Then, just before 2010, the price of gold increased and then fell slightly. Following the decline, there was a sharp rise in the price of gold until 2013. Subsequently, the price of gold fell and remained low compared to the previous period. At the end of 2019, there was a rapid increase in the price of gold, which continued until 2020. In the following years, the price of gold remained at approximately the same level with mild fluctuations.

From the beginning of the sample period, the interest rate differential had declined until just before 2006 (

Figure 3). Between 2006 and 2009, the interest differential increased rapidly. Subsequently, the interest rate differential fell sharply until 2011. Thereafter, the interest rate differential remained relatively flat until 2016; then, there was a slight bump, followed by a continuous decline throughout the remaining period (

Figure 3).

The volatility index shows varying degrees of variability captured. At the beginning of the sample period, there is mild volatility. Then, between 2007 and 2009, there is a spike, which is followed by other relatively smaller spikes (see

Figure 4). Thereafter, the volatility became moderate until 2020. In the year 2020, there was a noticeable spike (

Figure 4). However, it was not equivalent to the one experienced towards the beginning of the sample period. Thereafter, the volatility became relatively moderate. In the opinion of

Qadan and Yagil (

2012), dynamics in the volatility index are an indication of a risk sentiment; hence, they influence the returns of gold contracts. Furthermore, in

Abdullah’s (

2013) view, gold prices and interest rates have a negative relationship; a decline in the interest rate is associated with an increase in the attractiveness of gold, which increases its price. Therefore, an increase in interest rates increases the opportunity cost of holding gold; as a result, demand falls, and, therefore, inflation declines.

3.2. Model Specification

This study adopts a quantitative research design to analyse the relationship between global financial risks and the Rand/Dollar exchange rate. Specifically, this study employs the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model for its ability to capture both short-term adjustments and long-term equilibrium relationships, a characteristic highly significant for this study. The model’s flexibility in handling variables with mixed integration orders (I(0) and I(1)) also makes it particularly suited for financial time-series data, ensuring reliable estimation without the need for differencing. Additionally, the ARDL approach effectively accounts for current and lagged effects, making it an essential tool for understanding how external shocks and domestic factors influence Rand’s volatility across different time horizons.

By distinguishing between short-term fluctuations and long-term structural trends, this study provides a more nuanced perspective on exchange rate dynamics. Short-term movements in the Rand/Dollar exchange rate are largely driven by shifts in global risk sentiment and changes in interest rate differentials, which trigger immediate capital inflows or outflows, leading to sharp but temporary exchange rate adjustments. In contrast, gold price trends and sustained interest rate differentials play a more significant role in shaping long-term stability, influencing trade balances and investment flows over extended periods. This distinction is crucial for policymakers, as short-term volatility may require liquidity interventions and exchange rate management strategies, while long-term trends necessitate structural reforms and forward-looking monetary policy decisions.

The estimated ARDL model is expressed as follows:

where

represents Rand/USD exchange rate at time

t,

is volatility index at time

t,

is global gold price at time

t, and

interest rate differentials at time

t.

,

,

and

represent the short-run coefficients, while

,

,

, and

represent long-run coefficients. Furthermore,

and

denote the intercept and error term, respectively. The ARDL model accounts for serial correlation while allowing for a dynamic impact. In the event that

and

are selected optimally, the ARDL is characterised by white noise innovation that is not correlated with the regressors. Therefore, in this case, the model is considered dynamically well-specified.

Using the chosen lag length of the ARDL, the F-test is conducted to determine if the coefficients of the lagged variables (

,

,

and

) are jointly zero. If they are jointly different from zero, then it would indicate the presence of a long-run relationship between variables, then an ECM would be estimated. The ECM from the ARDL model is as follows:

The error correction term, denoted by ECT, seeks to capture the adjustment to the long-run equilibrium, whilst , , and represent the short-run parameters.

3.3. Estimation Procedure

The methodological steps in this study are designed to ensure the reliability and validity of the analysis, starting with unit root testing. The stationarity of all variables is assessed using the Augmented Dickey–Fuller and Phillips–Perron tests to confirm that variables are either integrated of order 0 or order 1. This step is critical for the ARDL approach, as it cannot accommodate variables integrated of order 2. If any variables were found to be I(2), alternative modelling techniques would need to be employed. By rigorously testing for stationarity, this study ensures that the data meet the prerequisites for ARDL application, enhancing the robustness and validity of subsequent analyses. Furthermore, this ensures that the estimated relationships between variables are not spurious, which is particularly important for financial time-series data that often exhibit stochastic trends.

The second step involves conducting bounds testing for cointegration to examine the existence of a long-run equilibrium relationship among the variables. The ARDL bounds test compares the computed F-statistic to critical values at various significance levels. Suppose the F-statistic exceeds the upper critical bound. In that case, cointegration is confirmed, indicating that the dependent variable (USD/ZAR exchange rate) and the independent variables (VIX, gold prices, and interest rate differentials) share a stable long-term relationship despite short-term volatility. This step is crucial for validating the long-term analysis and supports this study’s objective of distinguishing between short-term fluctuations and long-term trends. Bounds testing adds rigour to the analysis by explicitly identifying the nature of the relationships, ensuring this study’s conclusions are built on a solid statistical foundation.

Once cointegration is established, the ARDL model estimates both short-run and long-run coefficients, comprehensively analysing the variables’ impacts on the exchange rate. An Error Correction Model is employed to quantify the speed at which deviations from the long-run equilibrium are corrected. This dual analysis enables this study to capture immediate adjustments driven by short-term shocks and the sustained effects of global risk sentiment, gold prices, and interest rate differentials. By focusing on these dual temporal dimensions, this study provides nuanced insights into the drivers of exchange rate dynamics, addressing both immediate market responses and structural economic relationships. The ECM further allows policymakers and market participants to understand the resilience of the exchange rate system, particularly how quickly it can revert to equilibrium after disruptions.

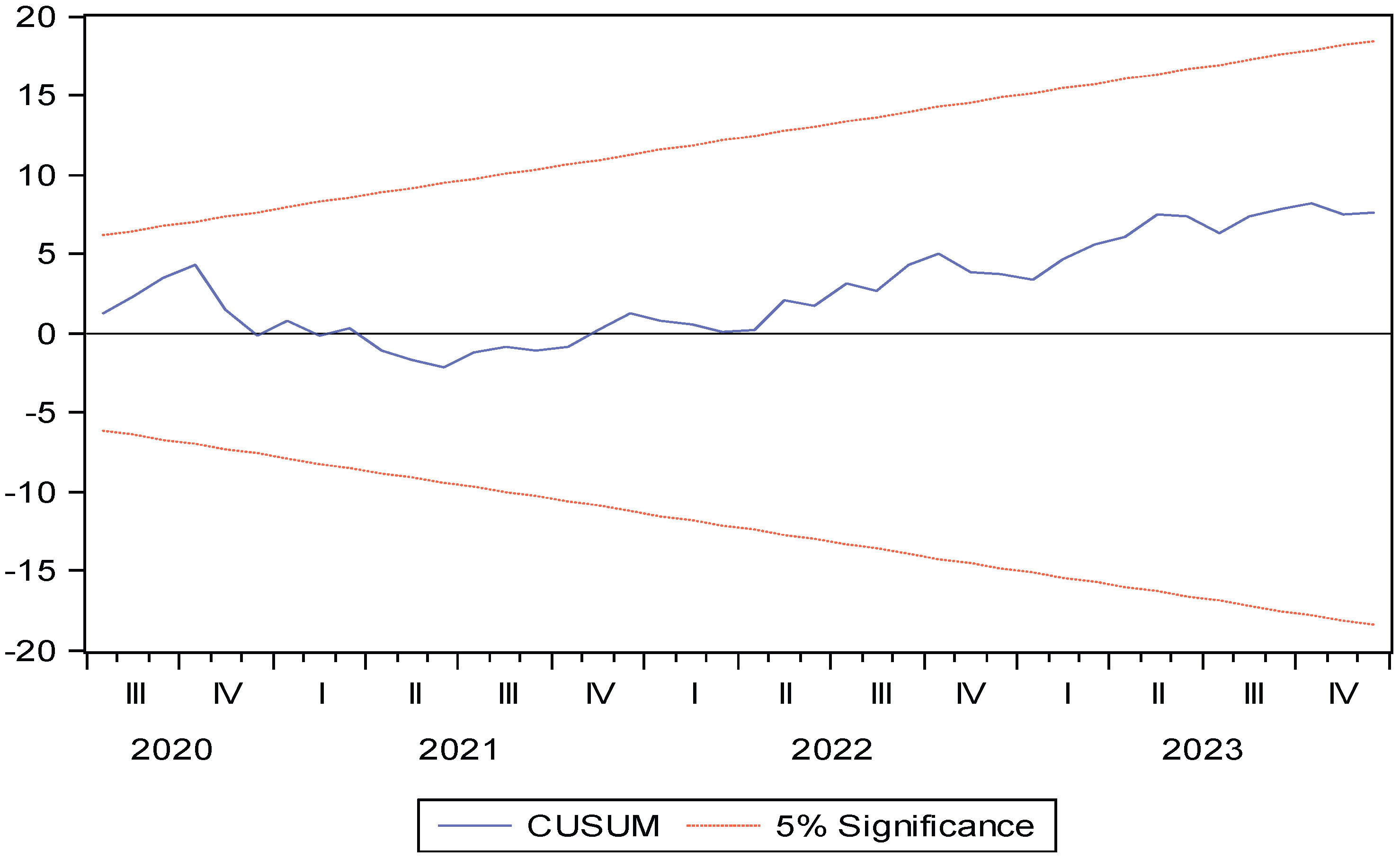

The final methodological step involves diagnostic testing to ensure the robustness and credibility of the model. The Breusch–Godfrey test for serial correlation verifies that the residuals are uncorrelated, while the White test for heteroskedasticity ensures that residuals have a constant variance, validating the consistency of the model’s estimates. Additionally, the Jarque–Bera test for normality confirms that the residuals follow a normal distribution, supporting the reliability of statistical inferences. These diagnostic tests collectively validate the ARDL model’s suitability, ensuring the results are robust and reliable for policy implications and further academic discourse. Conducting these tests safeguards against model misspecifications and strengthens confidence in the findings, allowing this study to serve as a reliable reference for future research and policy formulation.

5. Conclusions

This exchange rate volatility remains a key concern for emerging markets, influencing trade balances, inflation, capital flows, and overall financial stability. This study examined the relationship between global risk sentiment, commodity price fluctuations, and interest rate differentials and their impact on the South African Rand/US Dollar exchange rate from 2005 to 2023. The findings confirm H1, demonstrating that higher global risk sentiment, as measured by the volatility index, leads to short-term Rand depreciation due to capital outflows as investors seek safer assets like the US dollar. This sensitivity to external shocks underscores South Africa’s financial vulnerability, reinforcing the need for close monitoring of global market sentiment to anticipate exchange rate fluctuations and mitigate sudden currency depreciation risks (

Majenge et al., 2025).

The results also validate H2, showing that rising gold prices strengthen the Rand both in the short and long run. In the short term, higher gold prices improve investor sentiment toward South Africa, given its heavy reliance on gold exports. Over the long term, sustained increases in gold prices improve the trade balance, bolstering foreign exchange reserves and reducing currency depreciation pressures. Additionally, the findings confirm H3, highlighting the importance of interest rate differentials in shaping exchange rate movements. A widening interest rate differential in favour of South Africa attracts capital inflows, strengthening the Rand and supporting currency stability over time. These findings reinforce the interconnectedness of global financial conditions, commodity markets, and monetary policy, emphasising the need for adaptive policy frameworks that respond effectively to external pressures.

This study’s results align with theoretical expectations and prior literature, confirming that global risk sentiment, gold prices, and interest rate differentials significantly predict exchange rate movements. The robust long-run relationships identified suggest that policymakers must adopt proactive strategies to mitigate the impact of external shocks. This includes implementing macroprudential policies that enhance currency stability, leveraging monetary policy adjustments, and reducing dependency on volatile external factors. Moreover, continuous monitoring of global financial conditions is essential, as exchange rate fluctuations carry significant implications for macroeconomic planning, financial markets, and investment strategies. Addressing these challenges is crucial for ensuring sustainable economic growth and financial resilience in emerging markets.

To enhance economic resilience, policymakers should focus on economic diversification, reducing reliance on gold exports, and expanding technology and industrial sectors to create alternative sources of foreign exchange earnings. Strengthening foreign reserves would provide a critical buffer against currency depreciation during financial turbulence, while maintaining sound monetary policies would ensure stable interest rate differentials and sustained investor confidence in the South African economy. Additionally, fostering a more flexible exchange rate framework could help reduce the impact of speculative trading and external volatility shocks, creating a more stable financial environment.

For investors, strategies such as portfolio diversification, currency hedging, and real-time monitoring of global risk sentiment can help mitigate Rand volatility exposure. Given the Rand’s sensitivity to external shocks, foreign exchange risk management must remain a priority for businesses, investors, and financial institutions with exposure to South African markets. Additionally, enhancing financial market infrastructure could help attract stable foreign investment, reduce speculative-driven volatility, and promote long-term capital inflows. These measures would contribute to greater financial stability and a more predictable macroeconomic environment for both domestic and international stakeholders.

While this study provides valuable insights into the determinants of the Rand/Dollar exchange rate, some limitations should be acknowledged. Certain macroeconomic factors, such as fiscal policy and political risk indicators, were excluded due to data constraints and their more indirect influence on exchange rate volatility. Additionally, the ARDL model assumes linear interactions, which may not fully capture nonlinear effects or structural shifts from major economic shocks. Future research could explore alternative econometric methods, such as threshold models or nonlinear approaches, to better capture complex exchange rate dynamics. Despite these limitations, this study presents a robust and policy-relevant analysis, offering practical insights for policymakers, investors, and financial analysts navigating South Africa’s evolving economic landscape.