Loans to Family and Friends and the Formal Financial System in Latin America

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Latin American Context

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Confidence in the Financial System

3.2. Responses to Financing Needs

3.3. Credit Market Between Family and Friends

4. Data and Methodology

4.1. Data

4.2. Methodology

Marginal Effects

5. Results

Discussion of Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Borrowed from Friends and Family | FD Low | High FD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Observations | Mean | Observations | Mean | Observations | Mean |

| Gender (Female = 1) | 50,113 | 0.59 | 26,010 | 0.59 | 24,103 | 0.58 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Primary_lower | 18,097 | 0.36 | 11,518 | 0.44 | 6579 | 0.27 |

| secondary | 25,736 | 0.51 | 11,475 | 0.44 | 14,261 | 0.59 |

| University | 6044 | 0.12 | 2877 | 0.11 | 3167 | 0.13 |

| age | 50,113 | 41.63 | 26,010 | 40.67 | 24,103 | 42.68 |

| Income | ||||||

| The poorest (T1) | 8850 | 0.18 | 4786 | 0.18 | 4064 | 0.17 |

| Second (Q2) | 8911 | 0.18 | 4724 | 0.18 | 4187 | 0.17 |

| Medium (Q3) | 9655 | 0.19 | 5033 | 0.19 | 4622 | 0.19 |

| Fourth (Q4) | 10,571 | 0.21 | 5278 | 0.2 | 5293 | 0.22 |

| The richest (Q5) | 12,126 | 0.24 | 6189 | 0.24 | 5937 | 0.25 |

| sample | 50,113 | 26,010 | 24,103 | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | General | FD Low | High FD |

| distrust_of_banks | 0.920 *** | 0.704 *** | 1.667 *** |

| (0.182) | (0.211) | (0.360) | |

| GDPpc | −0.610 ** | −0.404 *** | −4.131 *** |

| (0.275) | (0.0802) | (0.668) | |

| unemployment | 0.163 *** | 0.123 *** | 0.177 *** |

| (0.00859) | (0.0139) | (0.0119) | |

| women | −0.135 *** | −0.197 *** | −0.0630 * |

| (0.0250) | (0.0347) | (0.0360) | |

| years of schooling | −0.250 *** | −0.336 *** | −0.109 * |

| (0.0435) | (0.0589) | (0.0660) | |

| age | 0.0310 *** | 0.0263 *** | 0.0353 *** |

| (0.00401) | (0.00554) | (0.00585) | |

| square_age | −0.000603 *** | −0.000536 *** | −0.000667 *** |

| (4.68 × 10−5) | (6.48 × 10−5) | (6.83 × 10−5) | |

| quintiles5 | 0.0516 | 0.0869 | 0.0257 |

| (0.0415) | (0.0577) | (0.0600) | |

| quintiles4 | 0.150 *** | 0.180 *** | 0.118 ** |

| (0.0408) | (0.0569) | (0.0587) | |

| quintiles3 | 0.220 *** | 0.240 *** | 0.203 *** |

| (0.0408) | (0.0566) | (0.0589) | |

| quintiles2 | 0.148 *** | 0.150 *** | 0.148 ** |

| (0.0418) | (0.0581) | (0.0602) | |

| Country and time controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 2.377 | 0.679 | 36.43 *** |

| (2.677) | (0.721) | (6.470) | |

| Observations | 50,078 | 25,993 | 24.085 |

References

- Abdelsalam, O., Chantziaras, A., Joseph, N. L., & Tsileponis, N. (2024). Trust matters: A global perspective on the influence of trust on bank market risk. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 92, 101959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afandi, E., & Habibov, N. (2017). Pre-and post-crisis trust in banks: Lessons from transitional countries. Journal of Economic Development, 42(1), 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, M. M., Ho, S. J., Mallick, S. K., & Matousek, R. (2021). Inclusive banking, financial regulation and bank performance: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance, 124, 106055. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, B. B., Garcia-Nunes, B., Lian, W., Liu, Y., Marulanda, C., Siddiq, A., Sumlinski, M. A., Yang, Y., & Vasilyev, D. (2023). The rise and impact of Fintech in Latin America. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros, M. S. (2018). Average marginal effects and interactions in binary logistic regressions. Working Paper, Incasi. Available online: https://www.aacademica.org/matias.salvador.ballesteros/43 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Banasaz, M., Bose, N., & Sedaghatkish, N. (2025). Identification of loan effects on personal finance: A case for small U.S. entrepreneurs. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 234, 106982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas, A., & Steiner, R. (2002). Why don’t they lend? Credit stagnation in Latin America. IMF Staff Papers, 49(S1), 156–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulkaran, V. (2022). Personal bankruptcy and consumer credit delinquency: The case of personal finance education. International Review of Financial Analysis, 81, 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2008). Financing patterns around the world: Are small firms different? Journal of Financial Economics, 89(3), 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beramendi, M., Delfino, G., & Zubieta, E. (2016). Institutional and social trust: An inescapable relationship. Psychological Research Journal, 6(1), 2286–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, L., García, A. F., & Roa, M. (2008). Country risk ratings and financial crises 1995–2001: A survival analysis. Borradores de Economía, 499, 2–23. [Google Scholar]

- Broekhoff, M. C., van der Cruijsen, C., & de Haan, J. (2024). Towards financial inclusion: Trust in banks’ payment services among groups at risk. Economic Analysis and Policy, 82, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, C., Chong, A., & Galindo, A. (2002). Development and efficiency of the financial sector and links with trust: Cross-country evidence. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 51(1), 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, B., Gupta, S., & Tovar Jalles, J. (2024). Fiscal policy and income redistribution in the turbulent era. In Fiscal policy in a turbulent era (pp. 155–167). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbacho, A., Philipp, J., & Ruiz-Vega, M. (2015). Crime and erosion of trust: Evidence for Latin America. World Development, 70, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didier Brandao, T., Feyen, E. H. B., Llovet Montanes, R., & Ardic Alper, O. P. (2022). Global patterns of fintech activity and enabling factors: Fintech and the future of finance flagship technical note. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2012). The intergenerational transmission of risk and trust attitudes. The Review of Economic Studies, 79(2), 645–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECLAC. (2023). Social panorama of Latin America and the Caribbean 2023. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. [Google Scholar]

- Engelberg, J., Gao, P., & Parsons, C. A. (2012). Friends with money. Journal of Financial Economics, 103(1), 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farías, P. (2019). Determinants of knowledge of personal loans’ total costs: How price consciousness, financial literacy, purchase recency and frequency work together. Journal of Business Research, 102, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J., & Wolak, J. (2016). The roots of trust in local government in western Europe. International Political Science Review, 37(1), 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromell, H., Nosenzo, D., & Owens, T. (2020). Altruism, fast and slow? Evidence from a meta-analysis and a new experiment. Experimental Economics, 23(4), 979–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. (1995). Social capital and the global economy. Foreign Affairs, 74(5), 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiani, S., Gertler, P., & Navajas-Ahumada, C. (2022). Trust and saving in financial institutions by the poor. Journal of Development Economics, 159, 102981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, A. J., & Schiantarelli, F. (2002). Credit constraints in Latin America: An overview of the micro evidence (IDB Working Paper No. 395). IDB. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ghosh, S. (2021). How important is trust in driving financial inclusion? Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 30, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2000). The role of social capital in financial development. (Working Paper No. 511). IDB. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güemes, C. (2019). “Wish you were here” trust in public administration in Latin America. Revista de Administração Pública, 53(6), 1067–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodula, M. (2022). Does Fintech credit substitute for traditional credit? Evidence from 78 countries. Finance Research Letters, 46, 102469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, K., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1993). Imperfect information and rural credit markets: Puzzles and policy perspectives. The Economics of Rural Organization: Theory, Practice, and Policy. [Google Scholar]

- IMF. External Relations Dept. (2004). Finance & Development, September 2004. Finance & Development, 41(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inter-American Development Bank. (2021). Uruguay IDB group country strategy 2021–2025. Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. (2023). World employment and social outlook. International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackowicz, K., Kozłowski, Ł., & Wnuczak, P. (2024). Do local differences in trust affect bank lending activities? Finance Research Letters, 61, 105004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J. Y., Kanagaretnam, K., & Wang, W. (2020). Societal trust and banks’ funding structure. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 27, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaretnam, K., Lobo, G. J., Wang, C., & Whalen, D. J. (2019). Cross-country evidence on the relationship between societal trust and risk-taking by banks. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 54(1), 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaivanov, A., & Kessler, A. (2016). A friend in need is a friend indeed? Theory and evidence on the (Dis)advantages of informal loans *. Available online: http://cier.uchicago.edu/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Keefer, P., & Scartascini, C. (2022). Trust: The key to social cohesion and growth in Latin America and the Caribbean (executive summary). IDB. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knell, M., & Stix, H. (2015). Trust in banks during normal and crisis times—Evidence from survey data. Economica, 82(s1), 995–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomson, I., Koomson, P., & Abdul-Mumuni, A. (2023). Trust in banks, financial inclusion and the mediating role of borrower discouragement. International Review of Economics and Finance, 88, 1418–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewski, O., & Pisany, P. (2022). Banks’ consumer lending reaction to fintech and bigtech credit emergence in the context of soft versus hard credit information processing. International Review of Financial Analysis, 81, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laferrère, A., & Wolff, F.-C. (2006). Microeconomic models of family transfers (pp. 889–969). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinobarómetro. (2023). Latinobarómetro 2020: Indicators of trust in institutions. Available online: http://www.Latinobarometro.Org (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Li, W., & Hua, X. (2023). The value of family social capital in informal financial markets: Evidence from China. Pacific Basin Finance Journal, 77, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T., & Yin, Z. (2024). The clan and informal financing in China: An analysis of the trickle-down effect. International Review of Economics & Finance, 92, 646–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makler, H., Ness, W. L., & Tschoegl, A. E. (2013). Inequalities in firms’ access to credit in Latin America. Global Economy Journal, 13(03n04), 283–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertzanis, C. (2019). Family ties, institutions and financing constraints in developing countries. Journal of Banking & Finance, 108, 105650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, C., Tarazi, A., & Ozturk Danisman, G. (2023). Disentangling the effect of trust on bank lending. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 210, 360–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presbitero, A. F., & Rabellotti, R. (2016). Credit access in Latin American enterprises. In Firm innovation and productivity in Latin America and the Caribbean (pp. 245–283). Palgrave Macmillan US. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Suárez, L. (2016). Financial inclusion in Latin America: Facts, obstacles and central banks’ policy issues. IDB Headquarters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. M., Pisor, A. C., Aron, B., Bernard, K., Fimbo, P., Kimesera, R., & Borgerhoff Mulder, M. (2023). Friends near and far, through thick and thin: Comparing contingency of help between close-distance and long-distance friends in Tanzanian fishing villages. Evolution and Human Behavior, 44(5), 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumaré, I., Tchana Tchana, F., & Kengne, T. M. (2016). Analysis of the determinants of financial inclusion in Central and West Africa. Transnational Corporations Review, 8(4), 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2011). Trust in public institutions over the business cycle. American Economic Review, 101(3), 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J. H., Watson, M. W., & Larrión, R. S. (2012). Introduction to econometrics (3rd ed.). Pearson Education, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Switek, M., Jimenez, L., & Jefferson, N. (2025, March 11). Global opportunity index 2025: Revisiting Latin America and the Caribbean. Milken Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Szeidl, A., Rosenblat, T., Karlan, D., & Mobius, M. (2009). Trust and social collateral. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3), 1307–1361. [Google Scholar]

- Turvey, C. G., & Kong, R. (2010). Informal lending among friends and relatives: Can microcredit compete in rural China? China Economic Review, 21(4), 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaggione, J. M., & Machado, M. D. D. C. (2020). Religious patterns of neoconservatism in Latin America. Politics & Gender, 16(1), E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waliszewski, K., Cichowicz, E., Gębski, Ł., Kliber, F., Kubiczek, J., Niedziółka, P., Solarz, M., & Warchlewska, A. (2023). The role of the Lendtech sector in the consumer credit market in the context of household financial exclusion. Oeconomia Copernicana, 14(2), 609–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wälti, S. (2012). Trust no more? The impact of the crisis on citizens’ trust in central banks. Journal of International Money and Finance, 31(3), 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT press. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2021). Global Findex Database 2021: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and access to credit. Available online: https://Globalfindex.Worldbank.Org (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- World Bank. (2023). Poverty and shared prosperity 2022: Correcting course. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. (2024, October 14). The world bank in uruguay. The World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X. (2020). Trust and financial inclusion: A cross-country study. Finance Research Letters, 35, 101310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmerli, S., & Castillo, J. C. (2015). Income inequality, distributive fairness and political trust in Latin America. Social Science Research, 52, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

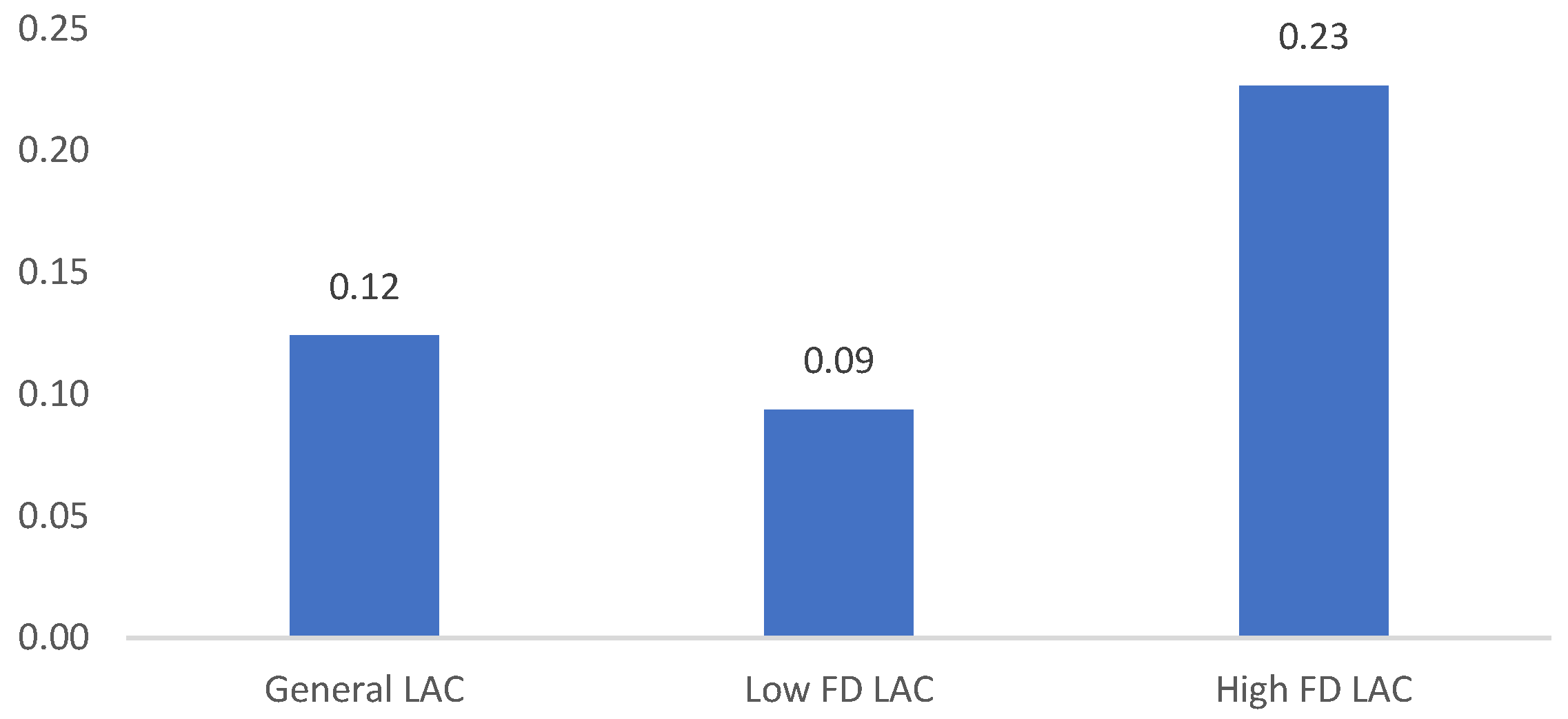

| VARIABLES | General LAC | FD under LAC | High FD LAC |

| Distrust ofbanks | 0.124 *** | 0.094 *** | 0.227 *** |

| (0.024) | (0.028) | (0.0489) | |

| GDPpc | −0.082 ** | −0.054 *** | −0.562 *** |

| (0.037) | (0.0107) | (0.0908) | |

| unemployment | 0.022 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.024 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.0018) | (0.0017) | |

| women | −0.018 *** | −0.026 *** | −0.0086 * |

| (0.003) | (0.0046) | (0.0049) | |

| primary | −0.034 *** | −0.045 *** | −0.0149 * |

| (0.006) | (0.0078) | (0.0090) | |

| secondary | −0.0065 | −0.015 | 0.0035 |

| (0.005) | (0.0072) | (0.0072) | |

| age | 0.004 *** | 0.0035 *** | 0.0048 *** |

| (0.0005) | (0.00074) | (0.00079) | |

| Age2 | −0.000008 *** | −0.00007 *** | −0.00009 *** |

| (6.32 × 10−6) | (8.64 × 10−6) | (9.29 × 10−6) | |

| Quintiles5 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.0035 |

| (0.0056) | (0.0077) | (0.0082) | |

| Quintiles4 | 0.020 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.016 ** |

| (0.0055) | (0.0076) | (0.0080) | |

| Quintiles3 | 0.030 *** | 0.032 *** | 0.028 *** |

| (0.0055) | (0.0075) | (0.0080) | |

| Quintiles2 | 0.020 *** | 0.020 *** | 0.020 ** |

| (0.0056) | (0.0077) | (0.0082) | |

| Country and time control | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 50,078 | 25,993 | 24.085 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herrero, S.; Rubio, J.; León, M. Loans to Family and Friends and the Formal Financial System in Latin America. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2025, 13, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13030116

Herrero S, Rubio J, León M. Loans to Family and Friends and the Formal Financial System in Latin America. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2025; 13(3):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13030116

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerrero, Susana, Jeniffer Rubio, and Micaela León. 2025. "Loans to Family and Friends and the Formal Financial System in Latin America" International Journal of Financial Studies 13, no. 3: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13030116

APA StyleHerrero, S., Rubio, J., & León, M. (2025). Loans to Family and Friends and the Formal Financial System in Latin America. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(3), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13030116