How Has the Renminbi’s Role in Non-USD Currency Markets Evolved After COVID-19? An Analysis Based on Spillover Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Wrangling

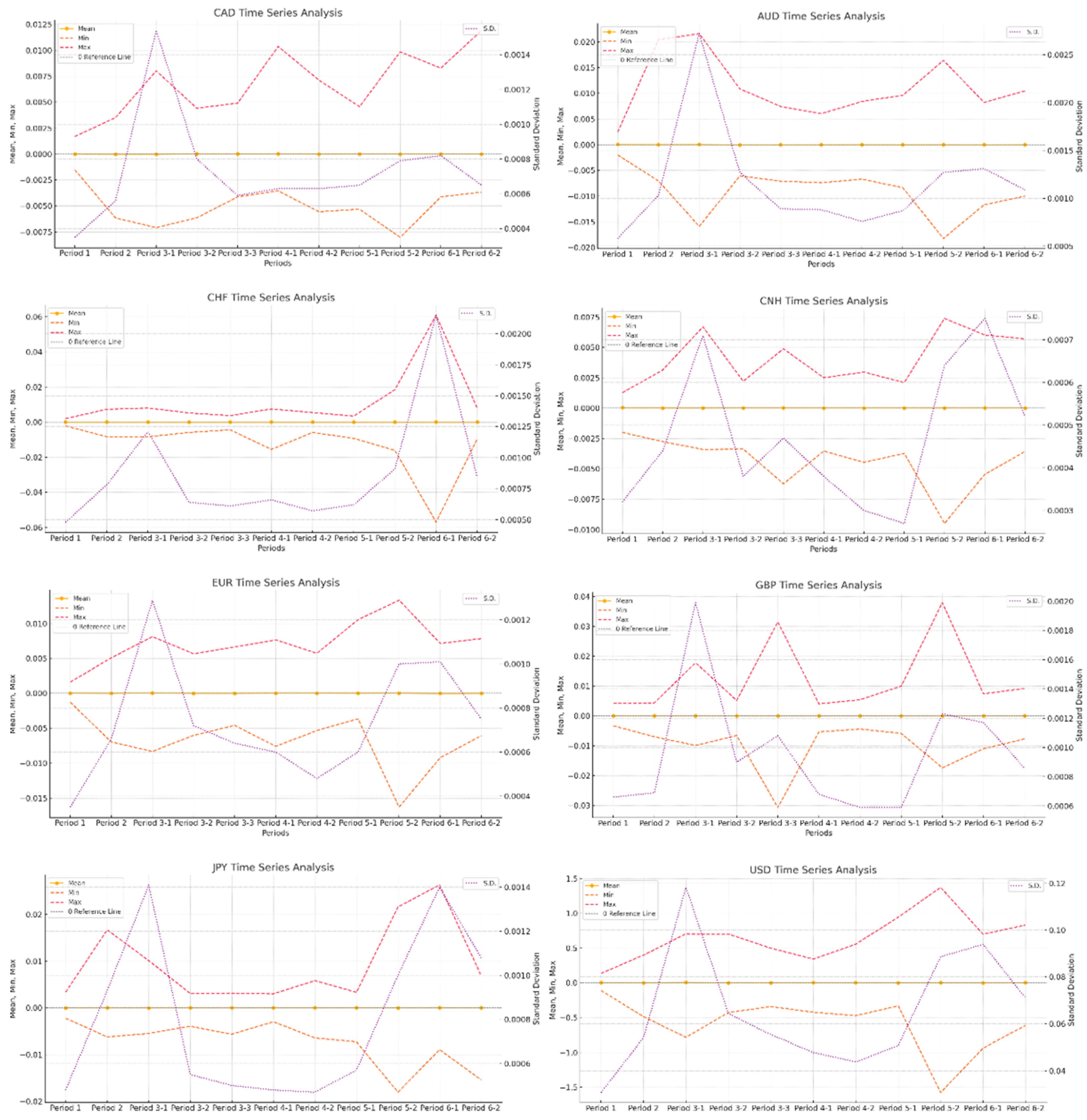

3.2. Data Description

3.3. Econometric Model Specifications

3.3.1. The Auxiliary Regression

3.3.2. The Vector Autoregression Model

3.3.3. The BEKK-GARCH Model

4. Analysis of Empirical Results at High-Frequency Data

4.1. Auxiliary Regression Analysis

4.2. Analysis of Mean Spillover Effect

4.3. Analysis of Volatility Spillover Effect

5. Analysis of Empirical Results Using Low-Frequency Data

5.1. Auxiliary Regression Analysis of Low-Frequency Data

5.2. Analysis of Mean Spillover Effect of Low-Frequency Data

5.3. Analysis of Volatility Spillover Effect of Low-Frequency Data

6. Comparison of High-Frequency and Low-Frequency Analysis

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In March 2020, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) announced the top eight most traded currencies, namely, the US dollar, the European euro, the British pound, the Japanese yen, the RENMINBI, the Canadian dollar, the Australian dollar and the Swiss franc. |

References

- Antonakakis, N., & Kizys, R. (2015). Dynamic spillovers between commodity and currency markets. International Review of Financial Analysis, 41, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, F., Aziz, S., Nguyen, D. K., Mughal, K. S., & Khan, M. (2020). On the efficiency of foreign exchange markets in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 161, 120261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2024). Annual report of the board of governors of the federal reserve system: Monetary policy report. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. [Google Scholar]

- Bordo, M. D., & Levy, M. D. (2021). Do enlarged fiscal deficits cause inflation? The historical record. Economic Affairs, 41(1), 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Liu, T., Chen, X., Li, J., & Wang, E. (2014, October 26–31). Time-frequency analysis of seismic data using synchrosqueezing wavelet transform. SEG International Exposition and Annual Meeting (SEG-2014), Denver, CO, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chng, M. (2009). Economic linkages across commodity futures: Hedging and trading implications. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(5), 958–970. [Google Scholar]

- Dufour, J., & Tessier, D. (1993). On the relationship between impulse response analysis, innovation accounting and Granger causality. Economics Letters, 42, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, A. H., Gozgor, G., & Lau, C. K. M. (2022). Causality and dynamic spillovers among cryptocurrencies and currency markets. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 27, 2026–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R., & Kroner, K. (1995). Multivariate simultaneous generalized ARCH. Econometric Theory, 11(1), 122–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Financial Stability Report. (2021, October). COVID-19, Crypto, and Climate Navigating Challenging Transitions. International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2021/10/12/global-financial-stability-report-october-2021 (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Grossmann, A., Love, I., & Orlov, A. G. (2014). The dynamics of exchange rate volatility: A panel VAR approach. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 33, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunay, S. (2021). Comparing COVID-19 with the GFC: A shockwave analysis of currency markets. Research in International Business and Finance, 56, 101377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, W., Mensi, W., Alomari, M., & Andraz, J. M. (2023). Downside and upside risk spillovers between precious metals and currency markets: Evidence from before and during the COVID-19 crisis. Resources Policy, 81, 103350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, P., Boivin, J., Li, W., Brazier, A., Kaminker, C., & Paul, V. (2023). Active approach: BlackRock 2024 global investment outlook. Available online: https://www.rl360adviser.com/news/2023/blackrock-global-investment-outlook-2024.htm (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Hoek, J., Kamin, S., & Yoldas, E. (2022). Are higher US interest rates always bad news for emerging markets? Journal of International Economics, 137, 103585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C., Li, J., Liu, L., & Yu, F. (2023). Spillover effect of the Renminbi and non-USD currencies after the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence captured from 30-minute high frequency data. International Review of Economics & Finance, 84, 527–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Marchi, E., Cervetto, M., & Galarza, C. (2023). Adaptive synchrosqueezing wavelet transform for real-time applications. Digital Signal Processing, 140, 104133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orăștean, R., & Mărginean, S. C. (2023). Renminbi internationalization process: A quantitative literature review. International Journal of Financial Studies, 11(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, A. (2022). Changing efficiency of BRICS currency markets during the COVID-19 pandemic. Economic Change and Restructuring, 55(3), 1673–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajhans, R. K., & Jain, A. (2015). Volatility spillover in foreign exchange markets. Paradigm, 19(2), 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey, G., & Ramey, V. A. (1995). Cross-country evidence on the link between volatility and growth. The American Economic Review, 85(5), 1138–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, C. (2010). Impact of the Renminbi exchange rate on sian currencies. In Currency internationalization: Global experiences and implications for the Renminbi. Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, C., He, D., & Cheng, X. (2015). One currency, two markets: The Renminbi’s growing influence in Asia-Pacific. China Economic Review, 33, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., Gao, J., & Wang, Z. (2014). Time-frequency analysis of seismic data using synchrosqueezing transform. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, 11(12), 2042–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Cui, H., Huo, H., & Nie, Y. (2018). Application of synchrosqueezed wavelet transforms for extraction of the oscillatory parameters of subsynchronous oscillation in power systems. Energies, 11(6), 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B. (1996). High-frequency data and volatility in foreign-exchange rates. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 14(1), 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Period | Event | Time Slot | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Pre-COVID-19 | 3 January 2020–20 January 2020 | |

| 2nd | COVID-19 Detected in China | 2 January 2020–11 March 2020 | |

| 3rd | 3-1 | COVID-19 Spread outside China | 11 March 2020–16 April 2020 |

| 3-2 | Lockdown | 16 April 2020–4 July 2020 | |

| 3-3 | No Vaccine | 4 July 2020–31 December 2020 | |

| 4th | 4-1 | Vaccine Emerged | 31 December 2020–7 May 2021 |

| 4-2 | The Fist Chinese Vaccine | 7 May 2021–26 November 2021 | |

| 5th | 5-1 | Omicron (B.1.1.529) | 26 November 2021–3 February 2022 |

| 5-2 | Surging Cases | 3 February 2022–11 November 2022 | |

| 6th | 6-1 | 20 Measures Released by China | 11 November 2022–8 January 2023 |

| 6-2 | Completely Open | 8 January 2023–5 May 2023 |

| CAD | AUD | CHF | CNH | EUR | GBP | JPY | USD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period 1 | ||||||||

| Mean | −0.00001 | 0.00003 | 0.00001 | 0.00003 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | −0.00003 | 0.00159 |

| S.D. | 0.00035 | 0.00058 | 0.00048 | 0.00032 | 0.00035 | 0.00066 | 0.00048 | 0.03073 |

| Kurtosis | 5.89143 | 4.08419 | 6.26145 | 8.42972 | 5.40090 | 11.04487 | 12.45137 | 5.50201 |

| Skewness | −0.21675 | 0.08317 | 0.10320 | −0.31082 | 0.31719 | 0.93276 | 0.63142 | 0.20647 |

| Min. | −0.00152 | −0.00202 | −0.00223 | −0.00201 | −0.00127 | −0.00328 | −0.00225 | −0.11170 |

| Max. | 0.00169 | 0.00245 | 0.00204 | 0.00126 | 0.00160 | 0.00427 | 0.00334 | 0.13548 |

| Size | 537 | 537 | 537 | 537 | 537 | 537 | 537 | 537 |

| J-B | 191.27 *** | 26.92 *** | 238.96 *** | 668.30 *** | 137.98 *** | 1525.98 *** | 2034.41 *** | 143.88 *** |

| Period 2 | ||||||||

| Mean | −0.00002 | 0.00002 | 0.00002 | −0.00001 | −0.00001 | 0.00000 | 0.00002 | −0.00087 |

| S.D. | 0.00056 | 0.00103 | 0.00078 | 0.00044 | 0.00066 | 0.00069 | 0.00093 | 0.05412 |

| Kurtosis | 20.95227 | 96.62887 | 24.69183 | 9.83862 | 18.59796 | 12.86804 | 69.26898 | 17.21488 |

| Skewness | −1.37412 | 3.68193 | −0.33449 | 0.30856 | −1.03046 | −0.57317 | 3.17730 | −1.18836 |

| Min. | −0.00616 | −0.00707 | −0.00831 | −0.00276 | −0.00698 | −0.00702 | −0.00624 | −0.48788 |

| Max. | 0.00351 | 0.02043 | 0.00725 | 0.00313 | 0.00509 | 0.00440 | 0.01673 | 0.39804 |

| Size | 1766 | 1766 | 1766 | 1766 | 1766 | 1766 | 1766 | 1766 |

| J-B | 24,270.49 *** | 649,048.60 *** | 34,656.51 *** | 3469.27 *** | 18,215.10 *** | 7262.12 *** | 326,118.24 *** | 15,284.11 *** |

| Period 3-1 | ||||||||

| Mean | −0.00002 | 0.00003 | −0.00003 | −0.00001 | 0.00003 | 0.00003 | −0.00004 | 0.00397 |

| S.D. | 0.00154 | 0.00272 | 0.00121 | 0.00071 | 0.00129 | 0.00199 | 0.00141 | 0.11821 |

| Kurtosis | 6.81426 | 12.37468 | 10.39641 | 13.53076 | 8.44162 | 11.22395 | 7.60076 | 8.16118 |

| Skewness | 0.14401 | 0.18987 | −0.13292 | 0.81280 | −0.11865 | 0.64144 | 0.25517 | 0.02417 |

| Min. | −0.00709 | −0.01590 | −0.00836 | −0.00342 | −0.00832 | −0.00988 | −0.00549 | −0.78441 |

| Max. | 0.00801 | 0.02160 | 0.00799 | 0.00669 | 0.00812 | 0.01783 | 0.01012 | 0.70434 |

| Size | 1246 | 1246 | 1246 | 1246 | 1246 | 1246 | 1246 | 1246 |

| J-B | 759.62 *** | 4570.17 *** | 2843.86 *** | 5894.59 *** | 1540.24 *** | 3596.74 *** | 1112.44 *** | 1383.07 *** |

| Period 3-2 | ||||||||

| Mean | 0.00001 | −0.00003 | 0.00001 | 0.00000 | −0.00001 | 0.00000 | −0.00000 | −0.00061 |

| S.D. | 0.00080 | 0.00127 | 0.00064 | 0.00038 | 0.00072 | 0.00090 | 0.00055 | 0.06433 |

| Kurtosis | 6.99599 | 7.65678 | 11.25126 | 9.08504 | 11.43994 | 6.43656 | 8.82971 | 16.54581 |

| Skewness | −0.28380 | 0.27633 | −0.25669 | −0.35780 | −0.34616 | −0.09480 | −0.37852 | 0.73677 |

| Min. | −0.00614 | −0.00608 | −0.00590 | −0.00338 | −0.00602 | −0.00659 | −0.00399 | −0.42870 |

| Max. | 0.00441 | 0.01085 | 0.00522 | 0.00221 | 0.00566 | 0.00517 | 0.00306 | 0.70026 |

| Size | 2676 | 2676 | 2676 | 2676 | 2676 | 2676 | 2676 | 2676 |

| J-B | 1816.34 *** | 2451.99 *** | 7620.67 *** | 4185.69 *** | 7995.88 *** | 1320.82 *** | 3853.29 *** | 20,701.11 *** |

| Period 3-3 | ||||||||

| Mean | 0.00001 | −0.00002 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | −0.00001 | −0.00001 | 0.00001 | −0.00118 |

| S.D. | 0.00059 | 0.00089 | 0.00061 | 0.00047 | 0.00064 | 0.00108 | 0.00050 | 0.05536 |

| Kurtosis | 7.28123 | 7.86233 | 7.18665 | 24.27787 | 11.16994 | 237.21185 | 12.63449 | 9.22763 |

| Skewness | −0.02953 | 0.16495 | −0.25277 | −0.90904 | 0.63666 | 0.18325 | −0.74273 | 0.57042 |

| Min. | −0.00413 | −0.00709 | −0.00441 | −0.00624 | −0.00460 | −0.03069 | −0.00565 | −0.34114 |

| Max. | 0.00490 | 0.00745 | 0.00373 | 0.00488 | 0.00664 | 0.03149 | 0.00314 | 0.49828 |

| Size | 6140 | 6140 | 6140 | 6140 | 6140 | 6140 | 6140 | 6140 |

| J-B | 4690.03 *** | 6076.31 *** | 4549.65 *** | 116,673.57 *** | 17,491.13 *** | 14,033,821.10 *** | 24,311.86 *** | 10,255.054 *** |

| Period 4-1 | ||||||||

| Mean | 0.00001 | −0.00000 | −0.00001 | 0.00000 | 0.00001 | −0.00000 | −0.00001 | 0.00001 |

| S.D. | 0.00063 | 0.00088 | 0.00066 | 0.00038 | 0.00060 | 0.00068 | 0.00048 | 0.04781 |

| Kurtosis | 23.14804 | 7.74342 | 80.44137 | 9.03837 | 29.34431 | 6.95194 | 6.90242 | 7.75383 |

| Skewness | 1.04767 | −0.00202 | −2.48318 | −0.08196 | 0.24124 | 0.06514 | 0.24429 | −0.00106 |

| Min. | −0.00355 | −0.00740 | −0.01559 | −0.00355 | −0.00760 | −0.00537 | −0.00301 | −0.42414 |

| Max. | 0.01036 | 0.00604 | 0.00743 | 0.00250 | 0.00766 | 0.00407 | 0.00299 | 0.34048 |

| Size | 4365 | 4365 | 4365 | 4365 | 4365 | 4365 | 4365 | 4365 |

| J-B | 74,629.50 *** | 4092.20 *** | 1,095,220.29 *** | 6636.39 *** | 126,267.69 *** | 2843.58 *** | 2813.16 *** | 4110.18 *** |

| Period 4-2 | ||||||||

| Mean | −0.00001 | 0.00001 | −0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | −0.00001 | 0.00095 |

| S.D. | 0.00063 | 0.00076 | 0.00057 | 0.00030 | 0.00048 | 0.00059 | 0.00047 | 0.04378 |

| Kurtosis | 11.54263 | 10.81769 | 11.82884 | 22.57643 | 16.16540 | 9.57808 | 16.75044 | 17.14735 |

| Skewness | −0.26459 | 0.16410 | 0.02208 | −0.68388 | 0.41157 | 0.13564 | −0.14512 | 0.48614 |

| Min. | −0.00556 | −0.00670 | −0.00588 | −0.00447 | −0.00533 | −0.00439 | −0.00644 | −0.47406 |

| Max. | 0.00712 | 0.00841 | 0.00544 | 0.00296 | 0.00572 | 0.00542 | 0.00583 | 0.55520 |

| Size | 6899 | 6899 | 6899 | 6899 | 6899 | 6899 | 6899 | 6899 |

| J-B | 21,058.23 *** | 17,599.36 *** | 22,407.47 *** | 110,702.30 *** | 50,019.30 *** | 12,459.81 *** | 54,375.26 *** | 57,805.81 *** |

| Period 5-1 | ||||||||

| Mean | −0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00001 | 0.00000 | −0.00000 | −0.00001 | 0.00000 | −0.00038 |

| S.D. | 0.00065 | 0.00087 | 0.00062 | 0.00027 | 0.00060 | 0.00059 | 0.00057 | 0.05073 |

| Kurtosis | 9.88200 | 17.83971 | 26.03651 | 25.88365 | 46.94422 | 43.14131 | 18.70600 | 57.21745 |

| Skewness | −0.40266 | 0.58912 | −1.03307 | −1.03515 | 2.01971 | 1.50972 | −0.59944 | 2.38186 |

| Min. | −0.00532 | −0.00837 | −0.00925 | −0.00374 | −0.00365 | −0.00589 | −0.00729 | −0.33117 |

| Max. | 0.00456 | 0.00960 | 0.00343 | 0.00210 | 0.01054 | 0.00998 | 0.00331 | 0.94303 |

| Size | 2346 | 2346 | 2346 | 2346 | 2346 | 2346 | 2346 | 2346 |

| J-B | 4693.02 *** | 21,661.92 *** | 52,291.34 *** | 51,606.85 *** | 190,359.48 *** | 158,398.19 *** | 24,253.33 *** | 289,557.49 *** |

| Period 5-2 | ||||||||

| Mean | −0.00000 | 0.00001 | −0.00001 | −0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00002 | −0.00002 | 0.00122 |

| S.D. | 0.00079 | 0.00127 | 0.00091 | 0.00064 | 0.00100 | 0.00123 | 0.00100 | 0.08856 |

| Kurtosis | 14.20063 | 18.16971 | 40.70444 | 20.59368 | 23.01189 | 113.47851 | 65.43784 | 32.18964 |

| Skewness | 0.22865 | −0.14845 | 0.73146 | 0.48927 | −0.19654 | 2.87051 | 2.12636 | −0.13477 |

| Min. | −0.00802 | −0.01827 | −0.01616 | −0.00950 | −0.01630 | −0.01738 | −0.01804 | −1.57566 |

| Max. | 0.00984 | 0.01641 | 0.01848 | 0.00738 | 0.01333 | 0.03797 | 0.02165 | 1.37212 |

| Size | 9567 | 9567 | 9567 | 9567 | 9567 | 9567 | 9567 | 9567 |

| J-B | 50,092.47 *** | 91,766.76 *** | 567,548.28 *** | 123,771.06 *** | 159,701.21 *** | 4,878,555.86 *** | 1,561,242.49 *** | 339,671.46 *** |

| Period 6-1 | ||||||||

| Mean | −0.00000 | −0.00002 | 0.00002 | 0.00002 | −0.00003 | −0.00002 | 0.00003 | −0.00216 |

| S.D. | 0.00082 | 0.00131 | 0.00215 | 0.00075 | 0.00101 | 0.00117 | 0.00140 | 0.09392 |

| Kurtosis | 12.14479 | 10.86095 | 593.77455 | 11.47083 | 14.15794 | 11.10392 | 78.65187 | 14.88892 |

| Skewness | 0.45799 | −0.42152 | 2.19824 | 0.34596 | −0.58666 | −0.42268 | 4.29107 | −0.52780 |

| Min. | −0.00413 | −0.01170 | −0.05699 | −0.00547 | −0.00922 | −0.01101 | −0.00892 | −0.93902 |

| Max. | 0.00828 | 0.00821 | 0.06094 | 0.00602 | 0.00715 | 0.00738 | 0.02634 | 0.69893 |

| Size | 1935 | 1935 | 1935 | 1935 | 1935 | 1935 | 1935 | 1935 |

| J-B | 6810.08 *** | 5039.48 *** | 28,140,858.38 *** | 5823.845 *** | 10,148.77 *** | 5352.55 *** | 467,371.77 *** | 11,485.89 *** |

| Period 6-2 | ||||||||

| Mean | −0.00000 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | −0.00000 | −0.00001 | −0.00001 | 0.00000 | −0.00011 |

| S.D. | 0.00065 | 0.00109 | 0.00084 | 0.00052 | 0.00075 | 0.00086 | 0.00108 | 0.07097 |

| Kurtosis | 36.18731 | 15.29340 | 14.21161 | 11.53932 | 13.39542 | 15.58549 | 21.17901 | 17.29955 |

| Skewness | 1.63121 | −0.14530 | 0.15891 | 0.41618 | 0.27009 | 0.23378 | −0.77617 | 0.30728 |

| Min. | −0.00367 | −0.01002 | −0.00953 | −0.00358 | −0.00607 | −0.00770 | −0.01539 | −0.61384 |

| Max. | 0.01191 | 0.01046 | 0.00790 | 0.00571 | 0.00784 | 0.00922 | 0.00689 | 0.83125 |

| Size | 3943 | 3943 | 3943 | 3943 | 3943 | 3943 | 3943 | 3943 |

| J-B | 182,699.04 *** | 24,842.91 *** | 20,668.08 *** | 12,093.98 *** | 17,802.09 *** | 26,058.83 *** | 54,690.44 *** | 33,655.93 *** |

| Currencies | USD | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-1 | 3-2 | 3-3 | 4-1 | 4-2 | 5-1 | 5-2 | 6-1 | 6-2 | |||

| CNH | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | −0.00387 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | −0.00387 *** | −0.00004 * | −0.00003 | −0.00003 * | −0.00003 | −0.00003 | −0.00003 | −0.00003 | −0.00004 ** | −0.00002 | −0.00004 ** |

| AUD | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | 0.01128 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | 0.01128 *** | 0.00002 | −0.00003 | −0.00004 | −0.00001 | −0.00002 | −0.00001 | −0.00000 | −0.00002 | −0.00001 | 0.00000 |

| CAD | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | −0.00652 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | −0.00652 *** | −0.00003 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00000 | 0.00001 | 0.00000 | −0.00000 | 0.00000 | −0.00002 | −0.00000 |

| CHF | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | −0.00841 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | −0.00841 *** | −0.00001 | −0.00001 | −0.00002 | −0.00002 | −0.00003 | −0.00002 | −0.00002 | −0.00002 | −0.00002 | −0.00001 |

| EUR | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | 0.01060 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | 0.01060 *** | 0.00000 | −0.00000 | −0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00001 | 0.00000 | 0.00001 | 0.00000 | −0.00000 | 0.00000 |

| GBP | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | 0.01084 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | 0.01084 *** | 0.00001 | −0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00000 | −0.00001 | −0.00000 | −0.00000 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | −0.00000 |

| JPY | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | −0.00681 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | −0.00681 *** | 0.00004 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00002 | 0.00001 | 0.00002 | 0.00002 | 0.00001 | 0.00004 | 0.00002 |

| Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-1 | 3-2 | 3-3 | 4-1 | 4-2 | 5-1 | 5-2 | 6-1 | 6-2 | |||

| CNH_slope | 0.07126 | 0.21557 | 0.17356 | 0.12833 | 0.10237 | 0.08913 | 0.04280 | 0.10514 | 0.05384 | 0.01048 | 0.07669 |

| JPY_slope | 0.16009 | 0.02074 | 0.03541 | 0.00444 | 0.00619 | 0.00920 | 0.02935 | 0.03530 | 0.00981 | 0.00884 | 0.05092 |

| CAD_slope | 0.18590 | 0.00882 | 0.01773 | 0.00310 | 0.03823 | 0.02208 | 0.01228 | 0.02817 | 0.01915 | 0.03922 | 0.03607 |

| CHF_slope | 0.02713 | 0.09867 | 0.03179 | 0.03670 | 0.02982 | 0.00103 | 0.01477 | 0.01268 | 0.00723 | 0.00410 | 0.03148 |

| EUR_slope | 0.27699 | 0.02661 | 0.11020 | 0.07700 | 0.08021 | 0.00724 | 0.14436 | 0.13555 | 0.02625 | 0.16030 | 0.04028 |

| GBP_slope | 0.05045 | 0.05195 | 0.03191 | 0.02121 | 0.00273 | 0.01931 | 0.02218 | 0.04020 | 0.00189 | 0.01643 | 0.03905 |

| AUD_slope | 0.03447 | 0.12212 | 0.02721 | 0.02536 | 0.03097 | 0.01213 | 0.01126 | 0.00257 | 0.00464 | 0.03571 | 0.01529 |

| Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-1 | 3-2 | 3-3 | 4-1 | 4-2 | 5-1 | 5-2 | 6-1 | 6-2 | |||

| JPY_slope | 0.0322 | 0.28302 | 0.01546 | 0.02247 | 0.02487 | 0.0168 | 0.08041 | 0.03276 | 0.07 | 0.05673 | 0.00541 |

| CAD_slope | 0.01231 | 0.22508 | 0.15356 | 0.0038 | 0.01658 | 0.05023 | 0.06268 | 0.02383 | 0.03448 | 0.00296 | 0.02018 |

| CHF_slope | 0.07296 | 0.17539 | 0.05098 | 0.12426 | 0.05603 | 0.00843 | 0.02222 | 0.01731 | 0.02903 | 0.01386 | 0.00219 |

| EUR_slope | 0.01534 | 0.03057 | 0.00516 | 0.02005 | 0.00972 | 0.01147 | 0.00679 | 0.01112 | 0.01301 | 0.06242 | 0.00396 |

| GBP_slope | 0.01506 | 0.07168 | 0.10577 | 0.03513 | 0.08761 | 0.00199 | 0.01393 | 0.02947 | 0.01667 | 0.01629 | 0.01118 |

| AUD_slope | 0.08780 | 0.69372 | 0.14556 | 0.04579 | 0.00264 | 0.0332 | 0.06387 | 0.01266 | 0.03738 | 0.04174 | 0.00445 |

| Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-1 | 3-2 | 3-3 | 4-1 | 4-2 | 5-1 | 5-2 | 6-1 | 6-2 | |||

| CNH-JPY | |||||||||||

| a12 | −0.07180 | 0.10190 *** | −0.11770 ** | 0.22210 *** | −0.05685 *** | −0.17570 *** | 0.04530 * | −0.04330 | −0.00833 | 0.00351 | −0.08470 ** |

| a21 | −0.15270 *** | 0.02982 *** | −0.04794 ** | 0.05292 *** | −0.02192 *** | 0.02330 | −0.00456 | −0.00857 | 0.00925 ** | 0.05544 *** | 0.10250 *** |

| b12 | 0.50770 *** | −0.07148 *** | −0.07424 ** | −0.17010 *** | 0.04620 *** | 0.06220 ** | −0.13270 *** | 0.10560 *** | 0.10030 *** | 0.24970 *** | 0.36920 *** |

| b21 | −0.21110 *** | −0.03679 *** | 0.13940 *** | 0.08037 *** | −0.01900 ** | −0.21210 *** | 0.03120 *** | −0.03130 ** | −0.02877 *** | 0.01705 * | −0.07230 *** |

| CNH-CAD | |||||||||||

| a13 | 0.14030 *** | −0.05138 *** | −0.06670 | −0.20970 *** | −0.00290 | −0.06690 *** | 0.01690 | −0.09350 *** | 0.01750 | −0.02830 * | −0.01140 |

| a31 | 0.00621 | 0.09711 *** | 0.01980 | 0.04312 *** | 0.00856 | 0.01770 | 0.00459 | 0.00145 | 0.06985 *** | 0.02850 | 0.01610 * |

| b13 | −0.20850 *** | −0.07173 *** | −0.40510 *** | 0.26560 *** | 0.02459 *** | 0.27360 *** | −0.13350 *** | 0.11870 *** | −0.08351 *** | 0.16190 *** | 0.33560 *** |

| b31 | −0.10650 ** | −0.10900 *** | −0.04449 *** | −0.11560 *** | −0.02758 *** | −0.08550 *** | −0.00668 | −0.05240 *** | −0.12380 *** | −0.06434 *** | 0.05410 *** |

| CNH-CHF | |||||||||||

| a14 | −0.04430 | 0.13640 *** | 0.00783 | 0.09315 *** | 0.01610 | −0.10750 *** | 0.00741 | 0.04600 | 0.01881 * | −0.03130 | −0.05660 *** |

| a41 | 0.07878 * | 0.06463 *** | −0.05390 | 0.08019 *** | 0.05516 *** | −0.06670 *** | −0.03310 *** | 0.03630 ** | 0.03278 *** | 0.00232 | 0.03510 ** |

| b14 | 0.16130 *** | −0.29470 *** | 0.38690 *** | 0.03810 | −0.02773 *** | 0.26070 *** | −0.20720 *** | −0.26160 *** | 0.16460 *** | 0.00569 | 0.08060 *** |

| b41 | −0.05750 | −0.27700 *** | −0.32000 *** | −0.04042 *** | −0.03602 *** | 0.01660 ** | 0.00420 | −0.29480 *** | −0.01321 *** | −0.04789 *** | −0.01480 * |

| CNH-EUR | |||||||||||

| a15 | 0.03663 ** | −0.01100 | −0.08271 *** | −0.02136 ** | −0.00704 | −0.10270 *** | −0.02840 *** | −0.04830 *** | 0.00444 | 0.04568 *** | 0.06250 *** |

| a51 | −0.15300 | 0.34550 *** | −0.20230 *** | −0.11660 *** | −0.02390 | 0.00364 | −0.14350 *** | 0.00961 | −0.04404 *** | −0.19760 *** | −0.18150 *** |

| b15 | −0.11840 *** | −0.02779 *** | −0.06157 *** | 0.09024 *** | 0.02412 *** | 0.10180 *** | −0.01580 ** | 0.02430 ** | 0.03513 *** | 0.02432 *** | 0.01780 *** |

| b51 | −1.21400 *** | −0.01090 | −0.16670 *** | 0.08203 *** | −0.00732 | 0.03970 *** | 0.08350 *** | −0.16020 *** | 0.11040 *** | 0.19100 *** | 0.20760 *** |

| CNH-GBP | |||||||||||

| a16 | −0.21530 *** | 0.00424 | 0.05530 | 0.17680 *** | 0.10140 *** | 0.02650 | 0.01550 | −0.04260 | −0.00139 | 0.01450 | 0.05950 ** |

| a61 | 0.06280 * | −0.08222 *** | −0.03265 ** | 0.00654 | −0.00237 | −0.07660 *** | 0.01510 | 0.09560 *** | 0.00449 | −0.02680 | −0.02580 |

| b16 | 1.04600 *** | −0.90350 *** | −0.18330 *** | −0.05748 ** | −0.06837 *** | −0.08390 *** | 0.32890 *** | 0.40530 *** | −0.03734 *** | 0.15240 *** | 0.24970 *** |

| b61 | −0.01450 | −0.43270 *** | 0.02319 *** | 0.03287 *** | −0.00504 | 0.10800 *** | 0.00876 | 0.01720 | −0.00663 | 0.13030 *** | 0.15720 *** |

| CNH-AUD | |||||||||||

| a17 | −0.06860 | 0.21760 *** | −0.12460 * | 0.21930 *** | 0.08239 *** | 0.08850 *** | 0.01880 | 0.01720 | −0.06134 ** | 0.09696 *** | 0.06750 * |

| a71 | 0.18900 *** | −0.02377 *** | 0.06127 *** | −0.05767 *** | 0.02545 *** | 0.04700 *** | −0.05420 *** | −0.01340 | 0.01347 *** | −0.00861 | −0.01940 * |

| b17 | 0.13200 | −0.07879 *** | −0.39150 *** | −0.95920 *** | −0.09385 *** | −0.56830 *** | −0.66560 *** | −0.90990 *** | −0.23580 *** | −0.15930 *** | −0.44860 *** |

| b71 | −0.04630 | 0.02144 *** | −0.01698 *** | −0.11190 *** | 0.07843 *** | −0.01160 | −0.07910 *** | 0.01820 ** | −0.02429 *** | −0.08881 *** | −0.07760 *** |

| Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-1 | 3-2 | 3-3 | 4-1 | 4-2 | 5-1 | 5-2 | 6-1 | 6-2 | |||

| CNH-JPY | |||||||||||

| H0: a12 = b12 = a21 = b21 = 0 | 31.50 *** | 20.70 *** | 26.37 *** | 66.18 *** | 9.30 *** | 64.90 *** | 17.28 *** | 4.95 *** | 160.10 *** | 44.55 *** | 139.30 *** |

| H1: a12 = b12 = 0 | 38.17 *** | 31.38 *** | 6.47 *** | 72.36 *** | 15.29 *** | 18.62 *** | 31.05 *** | 8.06 *** | 233.00 *** | 64.84 *** | 222.00 *** |

| H2: a21 = b21 = 0 | 27.36 *** | 9.62 *** | 50.24 *** | 52.61 *** | 8.54 *** | 106.70 *** | 8.77 *** | 3.32 ** | 81.24 *** | 9.07 *** | 102.50 *** |

| CNH-CAD | |||||||||||

| H0: a13 = b13 = a31 = b31 = 0 | 5.68 *** | 51.02 *** | 41.83 *** | 70.32 *** | 3.76 *** | 37.75 *** | 14.56 *** | 9.52 *** | 281.30 *** | 16.62 *** | 181.70 *** |

| H1: a13 = b13 = 0 | 9.68 *** | 22.53 *** | 63.01 *** | 79.71 *** | 4.05 ** | 64.99 *** | 23.01 *** | 9.86 *** | 108.50 *** | 30.86 *** | 294.30 *** |

| H2: a31 = b31 = 0 | 2.09 | 72.67 *** | 7.63 *** | 68.90 *** | 5.75 *** | 32.20 *** | 0.83 | 13.51 *** | 294.30 *** | 5.78 *** | 7.77 *** |

| CNH-CHF | |||||||||||

| H0: a14 = b14 = a41 = b41 = 0 | 3.32 *** | 167.60 *** | 204.50 *** | 10.93 *** | 28.02 *** | 42.14 *** | 7.66 *** | 125.20 *** | 137.50 *** | 8.32 *** | 13.93 *** |

| H1: a14 = b14 = 0 | 3.84 ** | 232.30 *** | 268.00 *** | 9.84 *** | 10.06 *** | 61.15 *** | 10.22 *** | 20.40 *** | 255.30 *** | 0.48 | 22.88 *** |

| H2: a41 = b41 = 0 | 2.18 | 108.90 *** | 102.70 *** | 14.13 *** | 24.55 *** | 17.15 *** | 3.46 ** | 160.80 *** | 21.57 *** | 15.00 *** | 3.52 ** |

| CNH-EUR | |||||||||||

| H0: a15 = b15 = a51 = b51 = 0 | 41.09 *** | 29.05 *** | 61.76 *** | 77.05 *** | 10.59 *** | 46.94 *** | 11.79 *** | 8.81 *** | 127.40 *** | 45.99 *** | 50.92 *** |

| H1: a15 = b15 = 0 | 21.12 *** | 9.34 *** | 86.68 *** | 136.10 *** | 19.29 *** | 70.18 *** | 10.36 *** | 9.28 *** | 52.36 *** | 61.33 *** | 29.91 *** |

| H2: a51 = b51 = 0 | 46.66 *** | 49.59 *** | 18.68 *** | 8.95 *** | 1.67 | 13.64 *** | 14.88 *** | 8.32 *** | 69.49 *** | 17.35 *** | 70.44 *** |

| CNH-GBP | |||||||||||

| H0: a16 = b16 = a61 = b61 = 0 | 60.60 *** | 590.70 *** | 15.98 *** | 11.93 *** | 9.39 *** | 57.63 *** | 73.04 *** | 96.25 *** | 6.79 *** | 58.04 *** | 156.90 *** |

| H1: a16 = b16 = 0 | 117.90 *** | 497.10 *** | 28.48 *** | 19.33 *** | 12.47 *** | 7.72 *** | 137.30 *** | 143.70 *** | 6.78 *** | 40.51 *** | 209.50 *** |

| H2: a61 = b61 = 0 | 1.40 | 415.70 *** | 5.22 *** | 5.54 *** | 1.56 | 114.90 *** | 1.74 | 21.12 *** | 0.88 | 37.12 *** | 62.18 *** |

| CNH-AUD | |||||||||||

| H0: a17 = b17 = a71 = b71 = 0 | 8.73 *** | 26.07 *** | 39.89 *** | 223.50 *** | 86.94 *** | 125.00 *** | 178.30 *** | 107.90 *** | 246.70 *** | 25.65 *** | 182.00 *** |

| H1: a17 = b17 = 0 | 1.19 | 43.81 *** | 39.92 *** | 197.30 *** | 31.17 *** | 205.60 *** | 214.60 *** | 207.60 *** | 194.80 *** | 17.23 *** | 159.50 *** |

| H2: a71 = b71 = 0 | 16.61 *** | 10.03 *** | 31.26 *** | 187.30 *** | 165.40 *** | 11.85 *** | 153.10 *** | 3.37 ** | 18.98 *** | 21.17 *** | 43.60 *** |

| Currencies | USD | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-1 | 3-2 | 3-3 | 4-1 | 4-2 | 5-1 | 5-2 | 6-1 | 6-2 | |||

| CNH | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | −0.00418 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | −0.00417 *** | −0.00004 *** | −0.00003 *** | −0.00004 *** | −0.00002 *** | −0.00003 *** | −0.00003 *** | −0.00003 *** | −0.00004 *** | −0.00002 ** | −0.00004 *** |

| AUD | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | 0.00980 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | 0.00981 *** | 0.00002 ** | −0.00002 * | −0.00004 *** | −0.00002 * | −0.00002 ** | −0.00001 | −0.00001 | −0.00002 * | −0.00002 | 0.0000 |

| CAD | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | −0.00649 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | −0.00650 *** | −0.00003 *** | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00000 | 0.00001 | 0.00000 | −0.00000 | 0.00000 | −0.00001 | 0.00000 |

| CHF | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | −0.00803 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | −0.00803 *** | −0.00001 | −0.00002 | −0.00002 | −0.00002 | −0.00002 * | −0.00002 | −0.00001 | −0.00001 | −0.00001 | −0.00001 |

| EUR | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | 0.01062 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | 0.01062 *** | −0.00000 | −0.00000 | −0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | −0.00000 | −0.00000 | 0.00000 |

| GBP | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | 0.01082 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | 0.01082 *** | 0.00001 | −0.00001 | 0.00001 | −0.00000 | −0.00001 | −0.00001 | −0.00001 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | −0.00000 |

| JPY | |||||||||||

| Non-Dummy Specification | −0.00709 *** | ||||||||||

| Dummy Specification | −0.00708 *** | 0.00004 *** | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00002 * | 0.00001 | 0.00002 * | 0.00002 * | 0.00001 | 0.00004 *** | 0.00002 |

| Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-1 | 3-2 | 3-3 | 4-1 | 4-2 | 5-1 | 5-2 | 6-1 | 6-2 | |||

| CNH_slope | 0.95810 | 1.06986 | 0.39982 | 1.26558 | 0.40620 | 0.71848 | 0.51991 | 0.08643 | 0.25345 | 0.43146 | 0.50316 |

| JPY_slope | 0.07720 | 0.55649 | 0.14134 | 0.27542 | 3.74475 | 0.93153 | 0.05141 | 0.26373 | 0.10669 | 0.01202 | 0.06620 |

| CAD_slope | 0.16097 | 0.15712 | 0.03740 | 0.01296 | 1.01397 | 0.06308 | 0.00106 | 0.15507 | 0.06081 | 0.06416 | 0.03557 |

| CHF_slope | 0.01308 | 0.27110 | 0.83269 | 0.14511 | 0.82834 | 0.10162 | 0.09205 | 0.02511 | 0.31385 | 0.00652 | 0.34085 |

| EUR_slope | 0.05717 | 2.87538 | 0.69947 | 0.12708 | 0.77454 | 0.00891 | 0.13513 | 1.26078 | 0.19620 | 0.07117 | 0.32979 |

| GBP_slope | 0.05439 | 0.19520 | 1.52071 | 0.04954 | 0.02530 | 0.03219 | 0.07860 | 0.11323 | 0.35329 | 0.49577 | 0.33680 |

| AUD_slope | 0.26062 | 0.60672 | 0.51588 | 0.10943 | 1.42880 | 0.16042 | 0.15411 | 0.13028 | 0.58590 | 0.64051 | 0.09789 |

| Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-1 | 3-2 | 3-3 | 4-1 | 4-2 | 5-1 | 5-2 | 6-1 | 6-2 | |||

| JPY_slope | 0.05941 | 0.32929 | 0.11375 | 0.08129 | 0.00243 | 0.01040 | 0.06239 | 1.24644 | 0.01636 | 0.08344 | 0.01245 |

| CAD_slope | 0.20097 | 0.11432 | 0.04525 | 0.12041 | 0.00334 | 0.08910 | 0.19189 | 0.70112 | 0.03397 | 0.03833 | 0.05423 |

| CHF_slope | 0.16791 | 0.02571 | 0.05264 | 0.08593 | 0.00200 | 0.00088 | 0.04946 | 1.47323 | 0.01824 | 0.03204 | 0.02688 |

| EUR_slope | 0.31959 | 0.00713 | 0.02139 | 0.10409 | 0.00314 | 0.01640 | 0.00191 | 0.11325 | 0.00399 | 0.01613 | 0.02259 |

| GBP_slope | 0.11821 | 0.02761 | 0.05410 | 0.10439 | 0.07698 | 0.01853 | 0.03296 | 1.95727 | 0.02614 | 0.01902 | 0.04299 |

| AUD_slope | 0.30248 | 0.02324 | 0.09046 | 0.10329 | 0.00076 | 0.00310 | 0.08758 | 1.69849 | 0.02335 | 0.01546 | 0.03932 |

| Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-1 | 3-2 | 3-3 | 4-1 | 4-2 | 5-1 | 5-2 | 6-1 | 6-2 | |||

| CNH-JPY | |||||||||||

| a12 | −0.16370 ** | −0.10200 *** | 0.03420 | 0.00068 | −0.00204 | −0.02747 *** | 0.03766 *** | −0.06256 *** | −0.00833 | −0.05974 *** | 0.05316 *** |

| a21 | 0.02170 | 0.17480 *** | −0.03379 *** | −0.02519 *** | 0.00356 | −0.00219 | −0.02246 *** | −0.04520 *** | 0.00925 ** | −0.00382 | 0.01760 *** |

| b12 | 0.41280 *** | 0.35490 *** | 0.00281 | 0.01510 | 0.01030 | 0.02632 *** | 0.05455 *** | −0.05103 ** | 0.10030 *** | 0.14770 *** | 0.14990 *** |

| b21 | −0.17590 *** | −0.39300 *** | 0.01480 | 0.05406 *** | −0.03838 *** | 0.01935 *** | −0.01973 *** | −0.10390 *** | −0.02877 *** | −0.01056 ** | −0.05820 *** |

| CNH-CAD | |||||||||||

| a13 | 0.20410 *** | 0.06500 *** | 0.00507 | −0.00347 | 0.00335 | 0.05931 ** | −0.43440 *** | 0.04310 ** | 0.01750 | 0.01420 | 0.00202 |

| a31 | 0.10030 ** | 0.05755 *** | 0.00863 | −0.01000 | 0.03454 *** | −0.01900 *** | −0.09116 *** | −0.00963 * | 0.06985 *** | 0.00422 | −0.01070 |

| b13 | −0.33850 *** | −0.25630 *** | −0.43310 *** | −0.00368 | 0.00122 | −0.16140 *** | 0.73740 *** | 0.30470 *** | −0.08351 *** | −0.01110 | 0.10440 *** |

| b31 | −0.08575 ** | −0.13500 *** | −0.01670 | 0.02379 *** | −0.06086 *** | 0.03443 *** | 0.11060 *** | 0.05686 *** | −0.12380 *** | −0.01460 ** | −0.01744 * |

| CNH-CHF | |||||||||||

| a14 | −0.04180 | −0.00516 | 0.01970 | −0.03777 ** | −0.01277 *** | 0.02941 ** | −0.01750 | −0.01914 ** | 0.01881 * | −0.25910 *** | 0.00364 |

| a41 | 0.10710 ** | −0.00370 | 0.10090 *** | −0.00781 | 0.01296 *** | 0.00264 | 0.01512 * | −0.01638 * | 0.03278 *** | −0.00124 | 0.05060 *** |

| b14 | 0.08143 ** | 0.03963 *** | 0.01010 | −0.00045 | 0.03356 *** | −0.02150 | 0.03121 *** | −0.04618 *** | 0.16460 *** | 0.41320 *** | −0.09823 *** |

| b41 | −0.15830 *** | −0.03189 *** | −0.04940 | 0.03052 *** | −0.01240 | −0.00255 | −0.02410 *** | −0.15030 *** | −0.01321 *** | −0.01194 *** | −0.16340 *** |

| CNH-EUR | |||||||||||

| a15 | 0.01270 | 0.01121 *** | −0.03097 *** | 0.00034 | −0.00133 | 0.01060 | −0.06416 *** | −0.01232 *** | 0.00444 | −0.03600 *** | 0.00903 ** |

| a51 | 0.67260 *** | −0.72740 *** | −0.07171 * | 0.19730 *** | −0.12640 *** | −0.00378 | −0.22640 *** | 0.17070 *** | −0.04404 *** | 0.02950 | −0.06197 *** |

| b15 | 0.03092 ** | −0.03352 *** | −0.00852 | 0.02340 | 0.00396 | −0.02040 | 0.12630 *** | −0.02279 *** | 0.03513 *** | 0.07690 *** | 0.03433 *** |

| b51 | −1.14600 *** | 1.30800 *** | 0.18780 *** | −0.45690 *** | 0.38500 | −0.01371 * | 0.60030 *** | 0.20870 *** | 0.11040 *** | 0.08504 *** | 0.14900 *** |

| CNH-GBP | |||||||||||

| a16 | −0.08450 | −0.03724 *** | 0.19260 *** | −0.01140 | −0.05310 | 0.00089 | −0.12140 *** | −0.09662 *** | −0.00139 | −0.02020 *** | 0.01380 |

| a61 | 0.04020 | −0.12250 *** | 0.08577 *** | 0.05285 *** | −0.00523 *** | −0.00477 | −0.04097 *** | −0.04144 *** | 0.00449 | 0.00082 | −0.02120 *** |

| b16 | 0.10430 ** | 0.09957 *** | −0.21440 *** | 0.01560 | −0.12460 * | −0.00560 | 0.22870 *** | 0.14240 *** | −0.03734 *** | 0.01452 *** | −0.00064 |

| b61 | −0.11590 *** | 0.19350 *** | −0.06273 *** | −0.09196 *** | 0.03030 | 0.00613 * | 0.12210 *** | 0.15590 *** | −0.00663 | 0.01952 ** | 0.08858 *** |

| CNH-AUD | |||||||||||

| a17 | −0.16850 *** | −0.10260 *** | −0.03350 | −0.08714 *** | −0.02689 *** | 0.03876 ** | −0.13290 *** | 0.16450 *** | −0.06134 ** | −0.01190 | 0.01750 |

| a71 | −0.18950 *** | −0.04685 *** | −0.05040 *** | −0.00983 | −0.07072 *** | 0.00156 | −0.08095 *** | 0.04940 *** | 0.01347 *** | −0.00224 | −0.02510 *** |

| b17 | 0.32490 *** | 0.35910 *** | −0.02050 | 0.03010 | 0.01120 | −0.01090 | 0.24250 *** | 0.40570 *** | −0.23580 *** | 0.00957 | −0.19560 *** |

| b71 | 0.18480 *** | 0.00055 | 0.04885 *** | 0.00387 | 0.17700 | 0.00493 | 0.13800 *** | 0.13270 *** | −0.02429 *** | −0.00321 | 0.07198 *** |

| Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-1 | 3-2 | 3-3 | 4-1 | 4-2 | 5-1 | 5-2 | 6-1 | 6-2 | |||

| CNH-JPY | |||||||||||

| H0: a12 = b12 = a21 = b21 = 0 | 14.31 *** | 316.20 *** | 3.30 ** | 15.89 *** | 5.36 *** | 13.80 *** | 19.86 *** | 30.12 *** | 160.10 *** | 6.20 *** | 18.73 *** |

| H1: a12 = b12 = 0 | 14.65 *** | 152.60 *** | 1.03 | 0.34 | 1.23 | 7.32 *** | 28.47 *** | 14.09 *** | 233.00 *** | 10.37 *** | 11.93 *** |

| H2: a21 = b21 = 0 | 10.53 *** | 504.60 *** | 5.35 *** | 29.40 *** | 9.48 *** | 24.21 *** | 12.27 *** | 52.36 *** | 81.24 *** | 2.68 * | 25.37 *** |

| CNH-CAD | |||||||||||

| H0: a13 = b13 = a31 = b31 = 0 | 12.34 *** | 52.70 *** | 16.76 *** | 2.93 ** | 15.23 *** | 7.59 *** | 466.20 *** | 39.61 *** | 281.30 *** | 2.05 * | 12.43 *** |

| H1: a13 = b13 = 0 | 22.50 *** | 64.58 *** | 31.80 *** | 0.18 | 0.24 | 7.06 *** | 636.90 *** | 58.63 *** | 108.50 *** | 1.25 | 15.19 *** |

| H2: a31 = b31 = 0 | 4.04 ** | 42.32 *** | 0.90 | 5.76 *** | 30.01 *** | 8.60 *** | 169.60 *** | 13.50 *** | 294.30 *** | 2.56 * | 4.82 *** |

| CNH-CHF | |||||||||||

| H0: a14 = b14 = a41 = b41 = 0 | 6.71 *** | 26.19 *** | 4.10 *** | 6.36 *** | 7.69 *** | 2.39 ** | 12.52 *** | 49.70 *** | 137.50 *** | 24.65 *** | 29.56 *** |

| H1: a14 = b14 = 0 | 2.14 | 31.35 *** | 3.88 ** | 3.78 ** | 10.33 *** | 4.41 ** | 8.93 *** | 8.15 *** | 255.30 *** | 10.50 *** | 12.20 *** |

| H2: a41 = b41 = 0 | 8.11 *** | 14.61 *** | 5.21 *** | 7.63 *** | 4.69 *** | 0.36 | 10.00 *** | 97.14 *** | 21.57 *** | 35.34 *** | 44.59 *** |

| CNH-EUR | |||||||||||

| H0:a15 = b15 = a51 = b51 = 0 | 29.09 *** | 272.60 *** | 9.35 *** | 65.33 *** | 32.64 *** | 1.89 | 310.40 *** | 28.28 *** | 127.40 *** | 17.90 *** | 11.17 *** |

| H1: a15 = b15 = 0 | 3.38 ** | 42.24 *** | 8.67 *** | 0.97 | 0.45 * | 0.61 | 397.80 *** | 11.19 *** | 52.36 *** | 22.73 *** | 8.83 *** |

| H2: a51 = b51 = 0 | 54.00 *** | 417.40 *** | 7.58 *** | 120.90 *** | 64.89 *** | 2.90 * | 180.40 *** | 48.13 *** | 69.49 *** | 11.30 *** | 12.19 *** |

| CNH-GBP | |||||||||||

| H0: a16 = b16 = a61 = b61 = 0 | 5.77 *** | 117.10 *** | 35.61 *** | 31.02 *** | 73.67 *** | 1.24 | 213.90 *** | 72.99 *** | 6.79 *** | 5.30 *** | 4.81 *** |

| H1: a16 = b16 = 0 | 2.91 * | 45.18 *** | 28.47 *** | 0.27 | 2.71 * | 0.43 | 211.50 *** | 47.57 *** | 6.78 *** | 5.05 *** | 1.02 |

| H2: a61 = b61 = 0 | 6.76 *** | 186.90 *** | 40.55 *** | 56.11 *** | 136.10 *** | 1.73 | 197.80 *** | 116.20 *** | 0.88 | 5.36 *** | 9.29 *** |

| CNH-AUD | |||||||||||

| H0: a17 = b17 = a71 = b71 = 0 | 16.61 *** | 144.60 *** | 18.22 *** | 2.33 * | 74.79 *** | 2.58 ** | 374.50 *** | 126.30 *** | 246.70 *** | 1.02 | 21.59 *** |

| H1: a17 = b17 = 0 | 19.46 *** | 248.90 *** | 2.24 | 4.14 ** | 22.87 *** | 4.20 ** | 120.60 *** | 106.50 *** | 194.80 *** | 1.03 | 21.41 *** |

| H2: a71 = b71 = 0 | 20.48 *** | 59.72 *** | 34.16 *** | 1.32 | 124.80 *** | 2.22 ** | 411.80 *** | 144.90 *** | 18.98 *** | 0.59 | 17.09 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, C.; Yu, F.; Li, J.; Zheng, G.; Liu, L. How Has the Renminbi’s Role in Non-USD Currency Markets Evolved After COVID-19? An Analysis Based on Spillover Effects. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2025, 13, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13010012

Lu C, Yu F, Li J, Zheng G, Liu L. How Has the Renminbi’s Role in Non-USD Currency Markets Evolved After COVID-19? An Analysis Based on Spillover Effects. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2025; 13(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Changrong, Fandi Yu, Jiaxiang Li, Guanghong Zheng, and Lian Liu. 2025. "How Has the Renminbi’s Role in Non-USD Currency Markets Evolved After COVID-19? An Analysis Based on Spillover Effects" International Journal of Financial Studies 13, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13010012

APA StyleLu, C., Yu, F., Li, J., Zheng, G., & Liu, L. (2025). How Has the Renminbi’s Role in Non-USD Currency Markets Evolved After COVID-19? An Analysis Based on Spillover Effects. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13010012