Abstract

Much research has been carried out to discover partnership critical success factors that influence public-private partnership success. Since most public-private partnership projects are long-term in nature and include contractual arrangements, there is still a lot to learn about contract governance’s role in public-private partnership performance. Therefore, this study examines the effect of contract governance on the relationship between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance in Malaysia. Stakeholder Theory serves as the underpinning theory for this study. This study employed a quantitative method based on the positivist paradigm to distribute questionnaires. The information was collected from 261 contracting parties’ officials in Malaysian public-private partnership projects regulated by the Malaysian Public-Private Partnership Unit, and a stratified random sampling method was employed. The structural equation model analysis found that eight out of ten hypotheses were supported. According to this study, it has been established that contract governance has a direct favorable influence on partnership performance. However, it is also found that contract governance does not moderate the relationship between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance. Due to time constraints and the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, this study was from a cross-sectional viewpoint and adopted a quantitative methodology. The findings of this study are important in the contract governance and partnership performance literature, providing policymakers and concessionaires with new information on the impact of contract governance on public-private partnership project performance. Managers of public-private partnership projects should also be able to enhance their projects’ performance by understanding how contract governance influences the performance of their projects.

1. Introduction

Many organizations have partnered with resource shortage issues (Chakkol et al. 2018; Downey et al. 2013), including a partnership between the government and private sector in the public-private partnership (PPP) initiatives. Better organizational governance and sustained industry leadership are among the advantages of a successful partnership (Stadtler 2015; Liu et al. 2014). Due to the complexity of the PPP relationship, contractual instruments (Chakkol et al. 2018) are often utilized to control partnership relationships and accomplish desired partnership goals. In PPP initiatives, the contract describes all parties’ roles and obligations. To ensure the collaboration achieves its aims, rigorous contract governance is needed (EPEC 2014). A contract binds all participants in a PPP project and may function as a governance instrument to ensure project performance meets objectives. Public-Private Partnership, commonly known as PPP or 3P initiatives, has been adopted in many countries as one mechanism to procure public facilities and services (Mohamad et al. 2018). Hence, public-private partnership projects are usually subjected to public attention. Since its inception in 1983, the performance of public-private partnership projects in Malaysia has received positive feedback from various stakeholders to improve performance in providing public facilities and services through the participation of private parties and to reduce public spending (Mohamad et al. 2018).

In the latest development, public-private partnership initiatives can assist governments in addressing health issues, including efforts to curb the spread of COVID-19 via constructing makeshift hospitals and implementing 5G technology in China (Abbas et al. 2021) and through an industrial vaccination program in Malaysia (Ministry of International Trade and Industry 2021).

In light of theoretical research gaps, first, the literature suggests the need to look into more success factors that may influence public-private partnership performance. Identifying and focusing on partnership critical success factors is important because they are considered key drivers to partnership performance, affecting partnership success (Al-Saadi and Abdou 2016; Ahmad et al. 2021). There is also a need for all contracting parties in a public-private partnership project to understand the potential factors that make a public-private partnership produce better performance compared to traditional arrangements (Hodge and Greve 2017). Second, many previous studies on critical success factors that affect the performance of public-private partnership initiatives illustrate a long list of factors, whether focusing on a specific industry, such as road projects in Ethiopia (Debela 2022), housing in Nigeria (Muhammad and Johar 2019), biopharmaceutical in Iran (Shakeri and Radfar 2017), or the public-private partnership in general (Chou and Pramudawardhani 2015; Shi et al. 2016). Although past academics have conducted several studies on critical success factors, research on such aspects from internal and external sources appears to be limited. As a result, this study looks at partnership critical success factors from both internal and external perspectives (Ahmad et al. 2021). Thirdly, the literature on contract governance seems limited and needs further enrichment, especially in the context of public-private partnerships. Studies conducted in contract governance previously focused on the inter-firm supply-chain context (Awan et al. 2018). However, limited evidence can be found on the relationship of contract governance with public-private partnerships.

In prior studies, minimizing opportunism was found to be essential for reducing the likelihood of partnership collapse and improving partner performance. Researchers have concentrated on formal and informal governance measures to diminish partner opportunism. Contract governance is essential to ensuring that PPP initiatives are implemented successfully. It is crucial to look at the contract governance aspects to emphasize how important this function is in ensuring the success of partnership performance. Establishing a contract governance structure in PPP initiatives would be more effective. The study on partnership performance has also been conducted on various spectrums, such as partnership performance measurements (Liu et al. 2014; Yuan et al. 2012) and performance measuring tools (Ali Mohammed et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2018). Additionally, there was also another spectrum that looked into the partnership critical success factors that may influence public-private partnership performance (Debela 2022; Ahmadabadi and Heravi 2019; Kavishe and Chileshe 2019; Muhammad and Johar 2019; Sehgal and Dubey 2019; Niazi and Painting 2018).

In line with the literature about the research objectives (ROs) below were developed:

- RO1:

- to investigate the relationship between contract governance and partnership performance; and

- RO2:

- to investigate if contract governance moderates the relationship between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance.

This study contributes to the extension of knowledge on the role of contract governance towards PPP performance in Malaysia. This study also examined the moderating role of contract governance on the relationship between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance in PPP initiatives in Malaysia. This study introduces the novel concept of contract governance as the primary contribution of this study. Contract governance is the monitoring or controlling of the factors that affect the performance of a partnership. Contract governance is crucial to guarantee the success of the implementation of PPP projects. It is necessary to investigate the contract governance features to emphasize the significance of this role in assuring the success of partnership performance. The increased success rate will inspire other initiatives to follow the most efficient means of obtaining the advantages. Implementing a contract governance framework in public-private partnership projects would increase the efficiency of its implementation.

The following is a breakdown of the study’s structure. The next section introduces Literature Review and the Theoretical Background. Hypotheses Development, Methodology, Data Analysis and Results, and Discussion of results are presented in the next sections. After that, theoretical and Managerial Implications, Policy Recommendations, Limitations of the Study, and Avenues for Future Research and Recommendations are discussed in subsections. The conclusion section ends this study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Public-Private Partnership Initiatives in Malaysia

As a progressive developing nation, Malaysia began public-private partnership initiatives in 1983 under the Privatisation Policy, and the emphasis shifted to public-private partnership in 2006 (Unit Kerjasama Awam Swasta 2009a). In March 2006, the Private Funding Initiative was launched to encourage the private sector to actively engage in public procurement projects, strengthening the initiative (Unit Kerjasama Awam Swasta 2009b). In 2009, the Public-Private Partnership Unit was founded as a specialized government unit to supervise the implementation of public-private partnerships in Malaysia. General guidelines govern public-private partnership projects despite the absence of codified laws (Unit Kerjasama Awam Swasta 2009b).

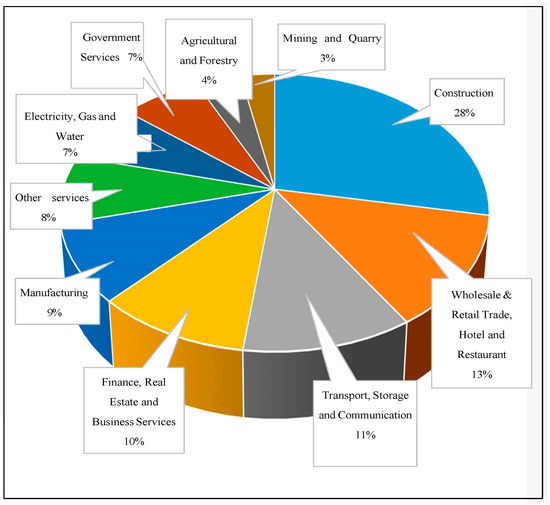

The implementation of public-private partnership projects in Malaysia includes several development sectors, with the construction industry accounting for 28% of the total contribution (EPU 2020). Between 2013 and 2019, public-private partnerships provided around RM46.2 billion in capital investment from the private sector for development projects (Unit Kerjasama Awam Swasta 2021). Even though public-private partnerships have contributed to the growth of Malaysia, they also pose significant budgetary concerns (Table A1 and Figure A1). As of June 2018, the Federal Government’s guarantee to undertake public-private partnership projects accounts for 18% of Malaysia’s total Gross Domestic Product (International Monetary Fund 2019).

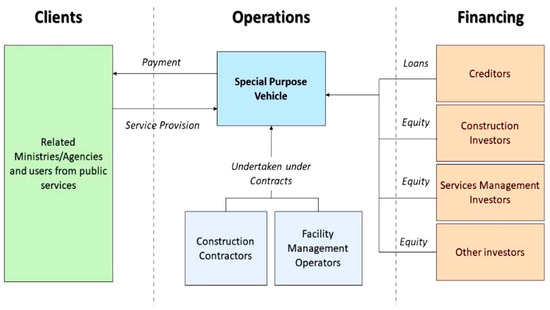

The public-private partnership project structure typically has five major players: the special purpose vehicle, the financier, the developers, the facility management operators, and the public sector organizations (Unit Kerjasama Awam Swasta 2009b). The government appointed the Public-Private Partnership Committee, which coordinates and oversees negotiations with private partners. The committee’s responsibilities include but are not limited to evaluating and taking into account public-private partnership projects that the government intends to pursue, conducting due diligence on private partners, attesting to the terms and conditions of agreements for Cabinet approval, and deciding the course of negotiations for such projects (Unit Kerjasama Awam Swasta 2020).

The government has issued six public-private partnership guidelines for administering public-private partnership implementation in Malaysia due to the absence of particular laws and statutes regulating public-private partnership implementation in the country (Figure A2). However, these guidelines seem too general and may need further explanation from the authorities. The absence of proper rules may lead to a decrease in project quality and an increase in the cost of the public-private partnership project (Ismail and Harris 2014).

2.2. Critical Success Factors of Public-Private Partnership

Hashim et al. (2017) define critical success factors as “those few key areas of activity where positive outcomes are required for a management to achieve their objectives”. Critical success factors are vital for managers to understand to accomplish project success or objectives. Critical success factors have been researched in several fields, including construction (Li et al. 2005; Alinaitwe and Ayesiga 2013; Niazi and Painting 2018; Ahmadabadi and Heravi 2019; Ahmad et al. 2021) and infrastructure (Chou and Pramudawardhani 2015; Wibowo and Alfen 2015). A long list of critical success factors in partnership initiatives can be found in previous studies. Mohr and Spekman (1994) examined the vertical interaction between personal computer manufacturers and dealers. According to the study, coordination, commitment, trust, communication quality, information sharing, engagement, shared problem-solving, and avoiding the use of smoothing over issues or extreme resolution techniques were all crucial factors of successful partnerships. The researchers identified collaboration, commitment, and communication methods as critical success factors for this kind of partnership success.

Li et al. (2005) performed another research study on the critical success criteria for public-private partnerships and private financing initiatives projects in the UK construction industry. The study ranked ‘robust private consortiums’ as the most critical success factor. The findings also found that critical success factors may be broken down into five primary components: successful procurement, project implementability, government guarantee, favorable economic conditions, and an accessible financial market. Another research on critical success factors in public-private partnerships was conducted by Babatunde et al. (2012) in Nigeria. The study discovered that only 6 out of 18 critical success factors examined were significant: adequate capital market, sound economic policy, good governance, risk allocation, risk sharing, stable macroeconomic condition, and rigorous and realistic cost-benefit analysis.

Conversely, in Malaysia, Ismail (2013) highlighted the significance of critical success factors as regarded by both public and private parties engaging in public-private partnerships in Malaysia. According to the research, the top five critical success factors for the successful implementation of public-private partnerships in Malaysia are good governance, commitment and responsibility, a favorable legal framework, a sound economic policy, and a viable financial market. Ismail’s study seems in agreement with another study conducted earlier in China. In their study, Chan et al. (2010) found that the key to the success of public-private partnerships in China is a ‘favorable legal framework’ followed by a ‘strong and excellent private consortium’. The study also classified 18 critical success factors into five categories: ‘macroeconomic stability’, ‘shared responsibility’, ‘transparent and efficient procurement procedures’, ‘political and social stability’, and ‘judicious government control’.

Hwang et al. (2013) examined critical success and risk factors in Singapore’s public-private partnerships. The researchers found that ‘transparency in the procurement process, clearly defined responsibilities and roles in the contract agreements, transparent contract conditions, and shared responsibility between the public and private sectors’ were among the success factors. According to the survey, Singapore’s top 3 critical success factors include a ‘well-organized government agency’, ‘adequate risk allocation and sharing’, and a ‘strong private consortium’.

In another research study, Hsueh and Chang (2017) found that the top 5 critical success factors were ‘realistic and feasible financial planning’, a ‘non-discriminatory, transparent, and impartial procedure to identify preferred bidders’, ‘sound legal frameworks’, an ‘incentive payment mechanism’, and ‘authorities, concessionaires, and financiers’ rights and obligations’.

Despite studies conducted in particular nations or circumstances, an effort was made to review and integrate the existing literature on the critical success factors of public-private partnerships. Osei-Kyei and Chan (2015) analyzed 27 studies from 1990 to 2013 on critical success factors in implementing public-private partnerships. Their research identified 57 variables in 27 papers. ‘Risk distribution and sharing’, ‘private consortium strength’, ‘government backing’, ‘public/community support’, and ‘open procurement’ were cited as the top 5 factors. 13 of 27 publications noted ‘proper risk allocation and sharing’, while 12 publications emphasized ‘strong private consortium’ as critical success factors.

This study examined partnership critical success factors from internal and external perspectives since it is crucial in strategic management and may enhance performance (Favoreu et al. 2016). The segregation between internal and external was guided by the definition provided by David (2013) and Liping Wang et al. (2018). The external variables are considered occurrences outside a firm’s control, and managers must devise strategies to maximize opportunities and minimize dangers. Internal factors, on the other hand, help organizations use their strengths and overcome their weaknesses.

The idea of investigating partnership critical success factors from internal—external point of view in the Malaysia context was based on the idea of Ismail (2013), who contended that despite the vast literature on critical success factors of public-private partnerships, the research on critical success factors in public-private partnerships according to internal and external spectrum is limited, particularly in Malaysia.

2.3. Partnership Performance

There is a substantial quantity of literature on partnership performance. It consists of terms such as collaboration (Austin and Seitanidi 2012; Gazley 2010), strategic alliance (Shakeri and Radfar 2017), collaborative inter-firm relationship (Piltan and Sowlati 2016b), network (Gazley 2010), multi-partners organizations (Menestrel et al. 2014), and partnership performance itself (Campos et al. 2018; Kelly 2012). These studies have been conducted from diverse perspectives, including parties’ capabilities, project characteristics, macro-environment, micro-environment, information sharing, cooperative decision-making, and risk/reward sharing (Campos et al. 2018; Piltan and Sowlati 2016a).

Ariño (2003) analyses strategic partnerships from an organizational effectiveness approach. According to the research, strategic objective achievement, satisfaction, and net spillover effect are not the same construct. On the other hand, overall satisfaction and spillover effect demonstrated convergent validity in the proposed model, which indicates that they were outstanding at measuring the same item.

In another research study, Gazley (2010) uses two distinct outcome measures to evaluate the potential impact of various partnerships and organizational characteristics on collaborative results. According to this study, formal contracts and prior experience working with non-profits and volunteers may enhance a public manager’s perception of success, but the intensity of shared objectives and the level of partnership involvement correlate strongly with actual performance improvement.

Beisheim and Campe (2012) evaluated the performance of transnational public-private partnerships in water governance via three case studies. In their study, the researchers related performance to effectiveness. Consequently, effectiveness was characterized by output, outcome, and impact.

According to Liu et al. (2014), costs and time were the most frequently assessed performance parameters in public-private partnerships. McAllister and Taylor (2015) state that a cost-benefit analysis is required for improved partnership performance. Mohamad et al. (2018) investigated two performance factors for public-private partnership initiatives in Malaysia: funding and market and innovation and learning. This highlights the need to evaluate a partnership’s financial and non-financial success.

2.4. Contract Governance

The common aspects of governance stated by earlier researchers were mechanisms to limit opportunistic behavior and the presence of the rule of law in terms of the contract that binds contracting parties. For this reason, the regulations governing these contracts were crucial. A contract mechanism as a tool for governance may improve the performance of an organization or project. Wang and Zhao (2018) describe contract arrangements as formal agreements between the public and private sectors that contain party responsibilities, role distribution, monitoring, and contingencies. Thus, it will enhance the institutional framework for contract-related rulemaking or the governance of contract law (Cherednychenko 2015).

Contract governance refers to the how-portion of a newly established partnership’s structure and often takes the shape of a formal contract arrangement (Chakkol et al. 2018). Contract governance is seen as an essential element of corporate governance, although it has received less attention in the past (Möslein and Riesenhuber 2009). Chakkol et al. (2018) noticed that contracts significantly impacted the effectiveness of cooperation. In addition, it reduces the likelihood of misunderstanding between partners by outlining expected milestones and providing business incentives (You et al. 2018). According to Möslein and Riesenhuber (2009), since the concept of contract governance is still nebulous, any study on the topic can fall into one of four categories: (1) the governance of contract law, (2) the governance of contract, (3) the governance utilizing contract law, and (4) the governance through contract.

Contract governance is one of the three primary stages of a public-private partnership’s life cycle, alongside planning and procurement (The World Bank 2018). Good contract governance increases a project’s financial viability and stability, hence recruiting better partners for public-private partnership initiatives (Al-Saadi and Abdou 2016). According to Al-Saadi and Abdou (2016), regulatory frameworks for public-private partnerships assist governments in ensuring that project partners perform successfully while safeguarding the private sector. According to their study, a robust governance framework is one of the crucial success criteria for public-private partnership infrastructure projects.

The new public management movement altered the hierarchical governance of the government’s management paradigm, resulting in contract governance (She and Tang 2017). Traditional hierarchical governance was contrasted with current contract governance. According to She and Tang (2017), contract governance prioritized ideas such as equality, consultation, collaboration, and mutual benefit. Based on empirical data, focusing on safety and risk management, enhancing government efficiency, and directing a reasonable pursuit of return on investment were effective strategies for enhancing contract governance in public-private partnership projects. Contract governance in public-private partnership projects provided three benefits: enhanced government management efficiency, economic rewards, and potential social benefits.

The relationship between contract governance and inter-organizational project performance was discovered by Lu et al. (2019). It has been shown that contract governance enhances the effect of quality management systems in inter-organizational projects. Bernstein (2015), who found that contract governance served as a means to control procurement contracts, has also shared this viewpoint. Bernstein proposed that relationship-based contracting might regulate contracts without depending on the legal system or compromising performance.

China (Li 2017) and Germany (Körs 2019) have included contract governance in policy research. Li (2017) examined China’s farmland transfer law from the perspective of contract governance. The author argues that the new procedural norms protect farmers more than the current law, which gives the government too much authority and undermines private land rights. Contract governance combines government regulation with private party autonomy. Körs (2019) later examined Germany’s policy instrument for controlling state-religious relations. The study examined Hamburg’s 2012 contracts with the Muslim and Alevi populations. The German state-church paradigm affects religious diversity granted under the “Basic Law”, or German constitution. The research found that the contracts were a vital step towards legal equality, but their effect was limited compared to non-religious life in contemporary societies. These two studies focused on public policy, but the main idea was how contract governance controls government-NGO ties. Contract governance checks both government authority and private rights. Contract governance is important in regulating public-private partnerships due to its complexity.

Contract governance creates clear requirements for all parties’ consistency. Contractual regulation may reduce the risk of participants evading their commitments by inhibiting their uncertain behavior (Lu et al. 2019). In their view, contract governance encourages collaboration via specified norms and processes. A legal and structural framework for mission execution. Contract governance supervises and manages joint endeavors.

Dahiru and Muhammad (2005) studied Nigerian PPP critical success factors. The study concluded that good governance is a top success factor for public-private partnerships in Nigeria. Kwofie et al. (2016) analyzed critical success factors for a PPP public house project in Ghana. Seventy-four participants answered questions based on 16 essential success indicators from past research. According to the study, the top six factors in Ghana’s public-private partnership public-house project were government guarantee, project identification, technical feasibility, competitive and transparent procurement procedure, a favorable legal framework, stable macro-economic conditions, sound economic policy, and a strong and robust financial market. Chou and Pramudawardhani (2015) analyzed critical success factors in Taiwan and Indonesia. The researchers modeled the Indonesian critical success factors using 17 factors. They observed that Taiwan’s critical success factors were lesser than Indonesia’s. Favorable legal framework, commitment and responsibility of the public and private sector, transparency procurement process, clearly defined responsibilities and roles, and good governance/government support were recognized as the most significant success factors in Indonesia. In contrast, Taiwan has only good macroeconomic circumstances and well-organized and dedicated governmental entities as their critical success factors.

2.5. Stakeholder Theory

The underpinning theory for this study is based on Stakeholder Theory. Even though Stakeholder Theory has no agreed-upon definition, it is crucial. Within academia, however, Freeman’s (1984) Stakeholder Theory was favored. Stakeholders are groups or individuals who may affect an organization’s aims. Stakeholder Theory emphasizes a company’s consumers, suppliers, employees, investors, communities, and other stakeholders. In short, it is to create “values” for all stakeholders, not just shareholders (Theory 2020). Miles (2017) described Stakeholder Theory as “what is and what is not a stakeholder” whose interests are attended to and, in turn, distinguishes what is experimentally examined by academics, attended to by managers, or regulated in practice. Freeman (1984) integrated Stakeholder Theory into strategic management. Since then, researchers have studied Stakeholder Theory extensively. Since then, Stakeholder Theory has been extensively published, yet various authors have offered contradictory data and logic (Donaldson and Preston 1995).

Stakeholder Theory was initially related to strategy as a method for organizing information that was becoming more vital in strategic planning to improve the effectiveness of company policy and strategy (Freeman et al. 2020). A stable organization is able to analyze and solve the challenges of its external environment by analyzing all organizations and individuals who may affect or be impacted by its actions and objectives. The idea was also different in that it laid forth notions to help decision-makers make better judgments instead of offering strategies to help a company outperform its competitors (Freeman et al. 2020).

Donaldson and Preston (1995) described Stakeholder Theory as descriptive, instrumental, or normative. A descriptive theory demonstrates that organizations have stakeholders, an instrumental theory demonstrates that firms with effective strategies consider their stakeholders, and a normative theory explains why firms should consider their stakeholders beyond strategic issues and into philosophical foundations. According to the Stakeholder Theory, all parties with genuine interests in a corporation should benefit from it, and no one group of interests or benefits should take precedence over another (Donaldson and Preston 1995). The authors related the legitimate interests of stakeholders to the input-output model of an organization, which Jones et al. (2002) later referred to as the “hub and spoke” model.

The influence of contract governance on the success of public-private partnerships may ultimately be tied to Stakeholder Theory. According to Zuhairah (2018), businesses must consider internal and external stakeholders while designing organizational strategies. Every stakeholder group has distinct performance objectives. Disparate expectations between the organization and its stakeholders may lead to conflict. Consequently, Stakeholder Theory may suggest that contract governance may have some effects on the performance of public-private partnerships, notwithstanding the ‘potential conflicts that may arise between attaining cost and time efficiency, objective effectiveness, and stakeholder satisfaction. According to this theory, contract governance will enhance partnership performance and meet stakeholders’ expectations (South et al. 2017).

Additionally, the evidence implies that contract governance may moderate partnership performance to some extent (Bai et al. 2016). Despite the fact that contracts are seen as crucial to the functioning of partnerships, there exists empirical research with conflicting and even contradicting findings (Wang and Zhao 2018). Additionally, contract governance seems to be one of the least-researched aspects of public-private partnerships (Hodge and Greve 2017). In the research by Lu et al. (2019), the capacity of contract governance to produce a positive moderating impact was also emphasized. The research demonstrates that contract governance amplifies the favorable benefits of quality management approaches on inter-organizational performance.

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. The Direct Effect of Contract Governance

Studies have shown a positive relationship between governance and performance. In Malaysia, Ismail (2013) revealed that good governance is among the public-private partnerships’ top five success factors. Good governance will improve the performance of public-private partnership initiatives. According to The World Bank (2018), a solid public-private partnership contract management system is essential to supervise the contract’s implementation. The existence of a contract management system is part of good project governance. Although one study showed contract governance to moderate partnership performance (Wang et al. 2018), many others have established a clear relationship between contract governance and partnership performance (Debela 2022; Almarri and Boussabaine 2017, 2023; Kulshreshtha et al. 2017). Another research study in India indicated that higher governance structure qualities lead to more efficient outcomes in hybrid governance (Kumar 2018). Public-private partnership hybrid governance has a good association with contract performance.

On another note, Kataike and Gellynck (2018) discovered a positive relationship between contract governance and performance. Choosing a governance structure will affect the costs of transactions between parties. Therefore, based on previous literature, a hypothesis is proposed below:

H1.

There is a positive direct relationship between contract governance and partnership performance.

3.2. The Moderating Effect of Contract Governance

Contract governance focuses on creating a framework where project participants collaborate and align with the project’s goals (Lu et al. 2019). Lumineau and Quélin (2012) state that contract governance regulates participant behavior. Consequently, contract governance and quality control activities are more efficient fin inter-organizational projects. The literature also suggests that contract governance may bring some degree of influence that moderates the partnership performance (Bai et al. 2016). Even though contracts are considered vital to partnership performancef, empirical studies show mixed and contradictory results (Wang and Zhao 2018; Ahmadabadi and Heravi 2019). Furthermore, contract governance seems to be one type of governance that is the least examined dimension in public-private partnerships (Hodge and Greve 2017).

In public-private partnerships, contract governance is a system for balancing the interests of many stakeholders. A well-designed contract can help allocate risks and rewards somewhat between public and private partners, clarify each partner’s roles and responsibilities, and establish performance criteria that reflect the needs of stakeholders. In a study conducted by Zhang et al. (2015), the influence of contract completeness on the performance of public-private partnership projects in China was analyzed using Stakeholder Theory. They discovered that contract completion positively affected stakeholder satisfaction, positively affecting partnership performance.

Using Stakeholder Theory, Liang and Wang (2019) evaluated the influence of governance mechanisms, including contract governance, on the performance of public-private partnership projects in China. They discovered that governance methods significantly improved stakeholder satisfaction and partnership performance. In research conducted by Mwesigwa et al. (2020) and Liang and Wang (2019), the impact of contract completion on the performance of public-private partnership projects in China was analyzed using Stakeholder Theory. They discovered that contract completion positively affected stakeholder satisfaction and partnership performance. The literature also suggests that contract governance may bring some influence that moderates the partnership performance (Bai et al. 2016). Even though contracts are considered vital to partnership performance, empirical studies show mixed and contradictory results (Wang and Zhao 2018). Furthermore, contract governance seems to be one type of governance that is the least examined dimension in public-private partnerships (Hodge and Greve 2017). The ability of contract governance to provide a positive moderating effect has also been mentioned in the study of Lu et al. (2019). The study shows that contract governance magnifies the positive effects of quality management practices on inter-organizational performance. This research supports the notion that Stakeholder Theory might serve as a valuable foundational paradigm for investigating the moderating impacts of contract governance in public-private partnerships. A well-designed contract can aid in balancing the interests of various parties and enhancing partnership performance. Hence, based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

Contract governance significantly moderates the relationship between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design, Population, Sampling Technique, and Data Collection

A quantitative approach appears appropriate given the study’s focus on the relationship between the variables of partnership critical success factors, partnership performance, and contract governance. This study employed stratified random sampling (proportionate stratified random sampling) to select respondents proportionate to the type of public-private partnership in Malaysia. Data for this study were gathered from officials from government agencies and private companies involved in 150 public-private partnership projects signed and implemented in Malaysia between 2009 and 2021. They are the most relevant individuals who may be able to provide adequate responses to the study’s questionnaire. The second consideration is the availability of data kept by the agency and the researcher’s ability to access those data. This study employed a self-administered questionnaire with references to existing research in the area. Since both parties are partners in a public-private partnership initiative, the same set of questionnaires was administered to them. The questionnaire aimed to gauge their perspectives about observable constructs in a public-private partnership project they handled.

This study mainly depends on primary data collected from public and private parties participating in public-private partnerships in Malaysia. The researcher sent an email to every affiliated department and company, describing the study and requesting permission to conduct it inside their organization. The researcher contacted the organization’s nominated point of contact to discuss the distribution strategy and electronic hyperlinks for surveys. Due to the Malaysian government’s mobility limitations caused by the COVID-19 outbreak, we utilized email and phone calls to interact with the groups. The questionnaire was then sent to individuals who met the researcher’s requirements. The responders then completed the online questionnaire, and the researcher’s Google Form program collected the data.

The data collection process was done between 1 February and 30 April 2021. Four hundred fifty questionnaires were sent to Malaysian respondents, which comprised public and private entities involved in public-private partnership projects in Malaysia. An email was used to send the surveys to the person elected by their organization to assist the researcher with this study. The response rate was 58%, with 261 responses out of 450 questionnaires sent. Research on the survey response rate found that the average response rate for studies using data collected from individuals was 52.7% (Baruch and Holtom 2008). In light of this, the response rate to the research is deemed adequate.

4.2. Construct Measurements

This study’s constructs are derived from prior research on partnership critical success factors, contract governance, and partnership performance. Thus, the items would be modified to assess what they were intended to measure and to accommodate the research setting. Table 1 summarizes the four main items, the number of items, and the reference sources for the assessment items utilized in this study.

Table 1.

Table of Constructs.

Although all measuring items were derived from prior research, they may be used to evaluate additional constructs. Thus, all items used to evaluate critical success factors, contract governance, and partnership performance were verified. This study used a 5-point Likert scale, as widely used in the previous study.

4.3. Reliability and Validity

According to Babbie (2010), a measurement is regarded as reliable if repeated observations of the same occurrence provide the same results, while validity is the extent to which an empirical measure accurately evaluates and reflects the true meaning of the researched topic. The Composite Reliability and Average Variance Explained criteria may be used to assess the reliability of a measurement model. According to Awang (2018), Composite Reliability indicates the internal consistency and reliability of the latent construct, while the Average Variance Explained is the average proportion of variance explained by the measuring items.

4.3.1. Reliability

Awang (2018) suggest that a value of CR > 0.6 is needed for a construct to achieve Composite Reliability (CR). In contrast, a value of AVE > 0.5 is required for any construct to reach an acceptable level. On the other hand, an instrument is regarded as reliable by Hair et al. (2013) if its composite reliability is more than 0.70. All of the study’s constructs achieve high levels of Composite Reliability value, as shown in Table 2, demonstrating the measuring model’s high degree of reliability.

Table 2.

Composite Reliability Values for the Constructs.

4.3.2. Validity

The ability of a scale to measure the intended idea it is designed to evaluate is called validity. In other words, validity is the degree to which the empirical measure correctly captures the concept’s underlying essence and assesses the notion under research (Babbie 2010; Sekaran and Bougie 2010). Convergent Validity, Construct Validity, and Discriminant Validity are the three forms of validity necessary for any measurement model, according to Awang (2018).

According to Fornell and Larcker (1981), Average Variance Extracted (AVE) may be used to assess Convergent Validity. The Convergent Validity of the measuring model is reached when all AVE values are greater than 0.5 (Awang 2018). On the other hand, Construct Validity is the extent to which a set of items accurately evaluates the presence of the construct intended to be tested (Saunders et al. 2016). According to Awang (2018), the measurement model’s construct validity is obtained when all Fitness Indexes are at the required level. At the same time, the Discriminant Validity is attained when the measurement model does not include any redundant components.

This study met all the validity test requirements in all three types of validity. The AVE values for every construct and sub-construct in this study are more than 0.5, as shown in Table 3, demonstrating that all of the study’s constructs have a high degree of convergent validity.

Table 3.

AVE Values for the Constructs.

At the same time, in Table 4, the Fitness Index met all requirements, demonstrating a high Construct Validity for the measuring model has been achieved in this study. The fitness indexes reflect the model’s fitness level to the data at hand. The goodness-of-fit indexes are crucial tools to evaluate the fitness level of a measurement model in a study that uses structural equation modeling. According to Hair et al. (2014), it is recommended to use at least one fitness index from each category of model fit. There are three model fit categories: Absolute Fit, Incremental Fit, and Parsimonious Fit. According to Hair et al. RMSEA, GFI, CFI, and Chisq/df are the most frequently reported indexes in the literature.

Table 4.

The Fitness Index for Measurement Model.

Conversely, Table 5 demonstrated the Discriminant Validity for all four constructs in this study. The diagonal value (in bold) represents the square root of the construct’s Average Variance Expected (AVE), whereas the other values show the correlation between the constructs. When the diagonal value (in bold) is bigger than the values in the row and column, as advocated by Awang (2018), Discriminant Validity is achieved for all constructions (2018).

Table 5.

Discriminant Validity Index for all Constructs.

5. Findings

5.1. Structural Model

The structural model illustrates the correlational or causal relationships between the study’s model variables and tests a specific hypothesis about these relationships (Hair et al. 2014; Jöreskog and Sörbom 1993). Based on the hypothesized interrelationships between the constructs, the researchers incorporated the latent constructs into the structural model and then examined the various goodness-of-fit criteria to determine whether re-specifying the model would result in a statistically better model fit.

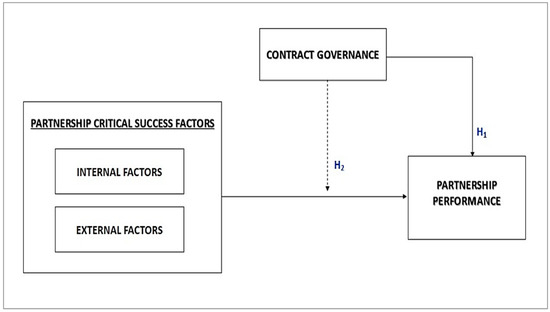

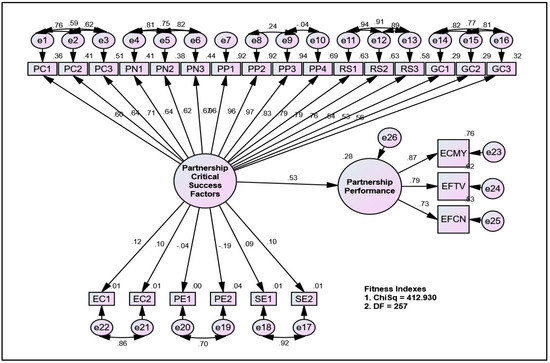

Using a structural equation model, the researchers analyzed the moderating effects of contract governance on the relationship between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance. In addition, this study investigates the direct influence of contract governance on partnership performance. Figure 1 displays the structural model hypothesis tested in this study.

Figure 1.

Structural Model for this Study.

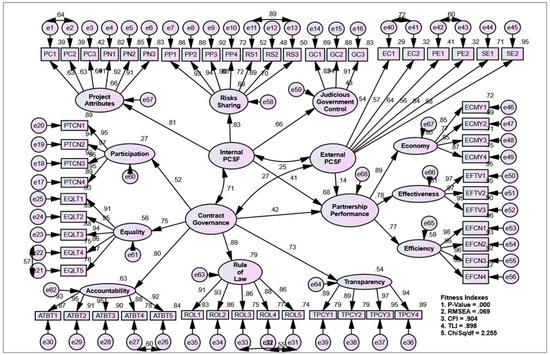

The fit of the structural model to the data was evaluated using goodness-of-fit indices, including absolute fit, incremental fit, and parsimonious fit, identical to the fit statistics for the measurement model. Completion of the structural model demonstrated a good fit with the observed data. The RMSEA, CFI, and Chisq/df results were all within acceptable parameters. Figure 2 demonstrates the results of pooled CFA generated by IBM-SPSS-AMOS.

Figure 2.

Results of Pooled Confirmatory Factor Analysis.

Table 6 displays the results of the model fit test in structural model analysis. These results indicate that the model was satisfactory and fulfilled the requirements. Since the model satisfies the requirement, it was not analyzed further. Consequently, no more adjustments were made to improve the model’s goodness of fit.

Table 6.

Result of Goodness-of-Fit Indices in Structural Model Analysis for Pooled CFA.

5.2. Direct Effect of Contract Governance

One of the objectives of this study was to establish a clear relationship between Contract Governance and Partnership Performance. To achieve this objective, Hypothesis 1 was formulated. Contract governance had a Beta value of 0.42 and a p-value of 0.000, indicating that it substantially affected partnership performance, as shown by the structural model. Similar to earlier research, our results indicate that incorporating contract governance in public-private partnership initiatives would increase project efficiency (She and Tang 2017).

In addition, Table 7 displays the Regression Path Coefficient and its Significance. The probability of getting a critical ratio as large as 4.307 in absolute value is less than 0.001 at α level. In other words, at a significance threshold of 0.001, the regression weight for Contract Governance in the prediction of Partnership Performance is substantially different from zero. Hypothesis 1 is thus supported.

Table 7.

The Regression Path Coefficient and its significance for H1.

5.3. Moderating Effect of Contract Governance

A moderator variable is a variable that modifies the causal relationship between Independent Variables and Dependent Variables (Awang 2018; Baron and Kenny 1986). In the Structural Equation Model, Multi Group Analysis is utilized to examine the moderator. The data are separated into groups during the analysis, depending on the moderator. This study explored Contract Governance as a moderating factor of the link between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance.

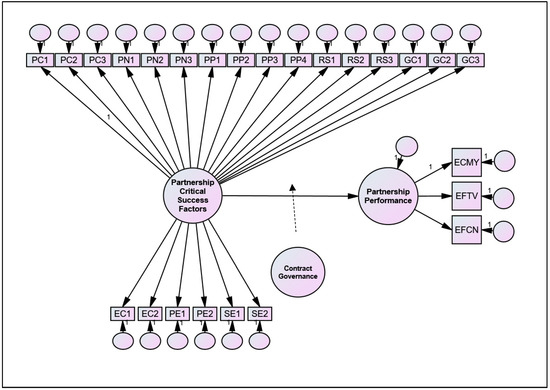

In order to test for a moderator effect in this study, the researcher separates Contract Governance into two groups, namely high-level and low-level Contract Governance. Through testing the moderator, the researcher may determine whether the impact of partnership critical success factors on partnership performance depends on contract governance. The contract governance moderating test was also run on the relationship between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance. The evaluable model of the moderating effect is shown in Figure 3 for Hypothesis 2.

Figure 3.

The framework shows the moderator to be tested for H2.

The data are arranged in ascending order based on the contract governance replies provided by respondents. Based on their judgments of contract governance, the data are divided into “Lower Contract Governance” and “Higher Contract Governance”. Awang (2018) suggest that the number of respondents in each group for parametric statistical analysis should exceed 100 to get consistent results. Eventually, both groups satisfied this supposition, making them eligible for the moderating tests.

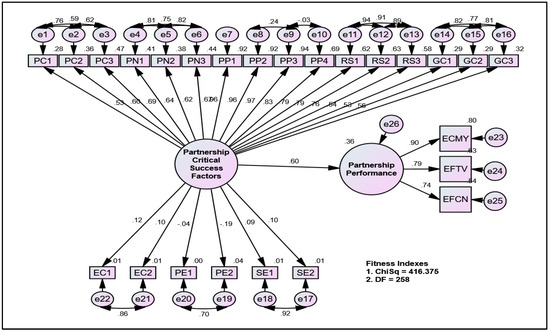

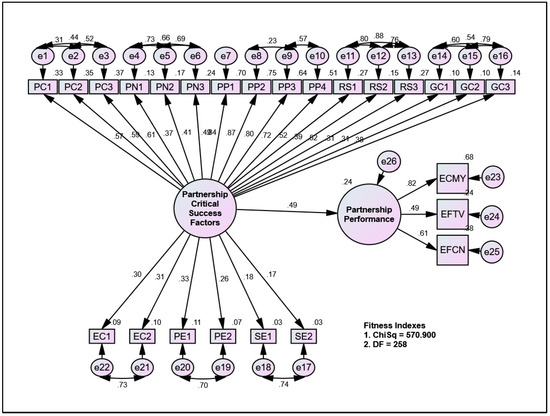

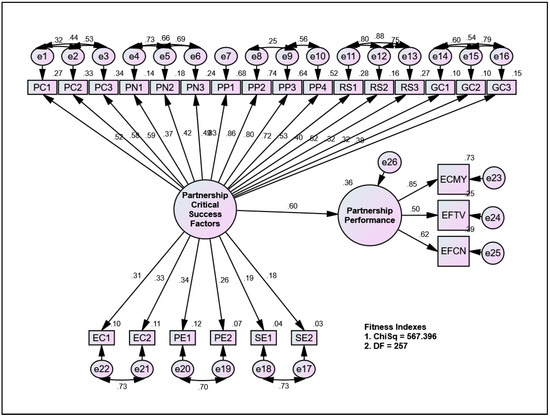

Figure 4 depicts the result of the lower contract governance group and the constrained model for the relationship between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance. In contrast, Figure 5 depicts the unconstrained model. Table 8 shows the result calculation to determine the hypothesis testing for moderating effects by the lower Construct Governance group. The Chi-Square value difference is 3445, whereas the degree of freedom is one. For a difference in Chi-Square values to be regarded as significant, it must surpass 3.84, the value of Chi-Square with one degree of freedom.

Figure 4.

Constrained Model for Lower Contract Governance Group.

Figure 5.

Unconstrained Model for Lower Contract Governance Group.

Table 8.

The Moderation Test for Lower Contract Governance Group Data.

The researcher then selects the second data set, the Higher Contract Governance group, and incorporates it into the same model. Figure 6 demonstrates the results of the moderation test for the higher contract governance group and confined model, whereas Figure 7 illustrates the outcomes for the unconstrained model for this group. Table 9 shows the difference between the Chi-Square values is 3.504, while the degree of freedom is one. To be considered significant, the difference in Chi-Square values must exceed 3.84, the value of Chi-Square with one degree of freedom.

Figure 6.

Constrained Model for Higher Contract Governance Group.

Figure 7.

Unconstrained Model for Higher Contract Governance Group.

Table 9.

The Moderation Test for Higher Contract Governance Group Data.

The beta values from Table 10 demonstrate no variation in either the beta estimates or the slope, indicating the absence of moderation in this test. Although the slope of the higher contract governance group is 0.49, the beta estimates for the lower contract governance group are 0.60. There is no difference between the two slopes, indicating neither interaction between the two equations nor moderation. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was rejected.

Table 10.

Comparison of Moderation between groups of Contract Governance.

6. Discussions

This study investigates the effects of contract governance on the performance of public-private partnership initiatives in Malaysia. Based on earlier research, contract governance has been proven to affect partnership performance directly. Still, it has also been a moderating factor for partnership performance. This investigation provides the chance to examine both situations.

6.1. Contract Governance as a Performance Factor

One of the goals of this study was to determine the relationship between Contract Governance and Partnership Performance. To achieve this objective, Hypothesis 1 is developed. The structural model revealed that Contract Governance had a Beta value of 0.42 and a p-value < 0.001, showing that it significantly influenced partnership performance. Similar to previous research, our findings imply that introducing contract governance into public-private partnership projects will boost project efficiency and uplift partnership performance, as She and Tang (2017) advocated.

This study demonstrates that Malaysian project managers for public-private partnerships think contract governance substantially impacts partnership performance quality. A written concession agreement that considers the interests of all parties will improve the performance of a given project. This need is consistent with the Stakeholder Theory, which states that a project must consider the interests of all stakeholders (Freeman et al. 2020). In this situation, the contract worked as a tool to preserve the interests of all parties.

Nonetheless, this study revealed that public-private partnership Project Managers consider “contract governance” (ß = 0.42) to have a slightly more substantial impact than the “internal partnership critical success factors” (ß = 0.41) but rather a bigger impact as compared to the “external partnership critical success factors” (ß = 0.14). Following the findings of Kataike and Gellynck (2018), it is projected that the partnership performance would perform better if project governance aspects were given more consideration during the formulation of the concession agreement.

6.2. Contract Governance as a Moderator

Based on these findings, the researchers discovered that project managers for public-private partnerships in Malaysia believe contract governance to be a partnership critical success factor that directly influences partnership performance, much like how an internal partnership critical success factor affects partnership performance. However, the PPP project managers only consider contract governance as a moderating factor to its relationship with the external partnership critical success factor. Thus, a partnership’s ability to control certain partnership critical success factors that make a difference in how the contract managers perceive the role of contract governance and its influence on partnership performance. Contract governance is seen as one of the aspects that may guarantee the partnership’s performance meets expectations, given that the partnership can manage internal success factors. This situation is consistent with David’s (2013) view that external factors are uncontrolled events, and managers must devise methods to minimize risks and maximize possibilities. This is because the partnership’s influence over these factors varies. Since the partnership can manage internal success factors, contract governance will be utilized as one of the variables to guarantee the partnership’s performance meets expectations. In the case of external success factors, contract governance is seen by managers as a moderating factor alone. Internal variables may assist businesses in capitalizing on their strengths and overcoming limitations.

7. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Study

Regardless of the subject matter, every research endeavor is subject to particular constraints that may compromise the research. This limitation arises from the challenges involved in conducting comprehensive studies. Several limitations of the current research have been identified. Based on the constraints, further studies may be conducted to analyze the study’s area and scope in greater depth, allowing for future improvements in research.

This study only examined the issue from a cross-sectional perspective, documenting the condition at a single time. Future research may employ a longitudinal methodology to provide more in-depth and valuable insights. In addition, many public-private partnership initiatives have lengthy concession periods, allowing for longitudinal analysis of the entire process.

Another limitation was the investigation of the moderating role of contract governance as to the relationship between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance per se. It is suggested that further investigation be conducted into the moderating role of contract governance in such relationships but from internal and external partnership critical success factors points of view. Even though it is found that there is no moderation effect of contract governance on the relationship between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance, there might be new findings when the investigation is to be done from a micro perspective.

Due to time constraints and the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic during half of the study period, this study’s research design exclusively employed quantitative methodologies. Consequently, mixed methods research may have a more significant impact on the study’s findings. Consequently, future studies may integrate the two methods to produce more reliable results. Since specific performance measures are subjective, interviews with public-private partnership project managers may be conducted better to comprehend the magnitude of partnership performance from their perspective.

8. Contribution of the Study

Theoretically, this study contributed to the corpus of knowledge regarding partnership performance and contract governance in public-private partnership initiatives in Malaysia. Prior research has given little consideration to the relationship between partnership performance and contract governance issues. This study illustrates the significance of contract governance as a critical success factor for partnership performance enhancement.

This study also revealed that managers of public-private partnerships recognize the significance of the concession agreement (contract) as a governance instrument for managing opportunistic behaviors. This result is consistent with the hypothesis previously expressed by Geyskens et al. (2006) and Wacker et al. (2016), namely that comprehending the contract as an instrument to prevent opportunism would improve the project’s performance following the Transaction Costs Economy theory.

In addition, contract governance was examined as a construct with a direct relationship to partnership performance and as a moderator of the interaction between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance. Contract governance and its partnership relationship critical success factors and partnership performance have been the subject of little prior research. Prior research has only examined the role of governance in general and as a determining factor in partnership performance.

In addition, this study examines equity and equity as one of the contract governance variables. According to previous research, governance constructs are evaluated using four factors: accountability, transparency, participation, and the rule of law. On the other hand, researchers believe that equity and equitability play an essential role in determining contract governance and governance in general, as contract governance must be equitable to all stakeholders and can be modified as necessary. As a result, equity and equitability are included in this study’s evaluation of contract governance, and the findings indicate that equity and equitability significantly impact contract governance measurement.

In Malaysian public-private partnerships, contract governance moderates the relationship between critical internal partnership success factors and partnership performance. By resolving the interests of all stakeholders within the partnership’s parameters, the conclusion suggests that the internal partnership’s critical success factors will be moderated to improve its performance. This finding is consistent with South et al. (2017) explanation of Stakeholder Theory.

The findings of this study have significant implications for the management and leadership of public-private partnership projects. The results indicated that management might wish to reconsider its strategy of concentration and targeting in order to enhance the partnership’s critical success factors and performance. Despite limited resources, understanding which partnership critical success factors to prioritize could significantly impact contract governance. The significance of contract governance as a factor in enhancing partnership performance would aid managers in organizing and monitoring the factors that must be prioritized. This finding also helps managers plan for better governance of their project execution in order to keep projects on track and effective in meeting partnership objectives for enhanced performance.

Implications for Practitioners and Policymakers

The findings of this study might have important implications for public-private partnership practitioners and policymakers. This study gave them great insight into the reality that not all success factors are under their control. Others are external, while some are internal. As a result, they may re-evaluate their prioritization of factors within their control.

Second, practitioners and policymakers should reconsider the techniques for establishing concession contracts, seeing them not just as a piece of paper that binds all parties involved but also as governance instruments to guarantee that the partnership’s performance remains at its peak.

The findings of this study also imply that by incorporating contract governance into public-private partnership projects, the efficacy of internal partnership critical success factors may be enhanced to increase partnership performance. Concession agreements manage the demand and expectations of all stakeholders in such projects. As a result, in public-private partnership activities, emphasizing contract governance as a tool that may improve partnership performance is crucial. Top management must lead continuous efforts to improve performance via contract governance as the most crucial aspect in promoting contract governance features in public-private partnership ventures.

9. Conclusions

The association between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance, as well as the role of contract governance as a direct and moderating factor, were investigated in this study. According to past literature, the effectiveness of public-private partnership projects in several countries, notably Malaysia, has been debated despite extensive studies on the critical success factors that impact partnership performance. As a result, researching this topic is critical and valuable. As a result, the current study expands on previous studies that looked at the impact of partnership critical success factors on partnership performance from internal and external perspectives. The main objective of this study was to look at the role of contract governance in moderating the relationship between critical partnership success factors and partnership performance in Malaysia.

According to the study, contract governance shows its direct relationship to partnership performance. The moderation test, however, revealed that contract governance had no moderating effect on the relationship between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance. This study contributed to the body of knowledge in various fields, including contract governance. This study contributes to the body of knowledge on the addition of “equity and equitability” as an element to measure contract governance. It is also significant to note that this study helped public-private partnership managers comprehend the impact of contract governance on partnership critical success factors and performance. Future research on partnership performance should use the model developed in this study as a basis and guidance. Future research may also look into the existence of the moderating role of contract governance on the relationship between partnership critical success factors and partnership performance from an internal and external perspective. In summary, this study has helped better investigate the essential areas of partnership critical success factors, contract governance, and partnership performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.A.L., R.H. and N.A.A.; Methodology, A.S.A.L. and R.H.; Validation, N.S.J. and A.A.L.; Formal analysis, A.S.A.L. and R.H.; Investigation, A.S.A.L.; Resources, Z.I. and R.H.; Data curation, A.S.A.L., R.H. and Z.I.; Writing—original draft, A.S.A.L. and R.H.; Writing—review and editing, A.S.A.L. and R.H.; Visualization, Z.I., N.S.J. and R.H.; Supervision, A.A.L.; Project administration, N.A.A. and R.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors and can be provided upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

According to the EPU (2020), 815 public-private partnership projects were initiated in Malaysia from 1983 to 2019, as illustrated in Table A1 below.

Table A1.

Data on Privatization in Malaysia from 1983–2019.

Table A1.

Data on Privatization in Malaysia from 1983–2019.

| Privatization Achievement from 1983–2019 | |

|---|---|

| Total Projects Privatized (as at 31.12.2019) | 815 |

| Jobs eliminated from Government payroll | 113,487 |

| Savings (RM billion) | |

| Capital Expenditure | 208.5 |

| Operating Expenditure | 9.3 |

| Proceeds from Sales of Government Equity and Assets | 6.5 |

| Market Capitalization (as at 31 December 2019) | |

| RM billion | 287 |

| % of total Bursa Malaysia capitalization | 17.2 |

Source: Adapted from EPU (2020).

The implementation of public-private partnership projects in Malaysia also covers various development sectors, with an enormous contribution towards the infrastructure sector. The details of public-private partnership projects according to the distribution of sectors (EPU 2020) are mentioned in Figure A1 below.

Figure A1.

Sectorial Distribution of PPP Projects from 1983–2019 (% out of total 815 projects).

The public-private partnership structure in Malaysia is illustrated in Figure A2 below.

Figure A2.

PPP Project Structure in Malaysia.

References

- Abbas, Hafiz Syed Mohsin, Xiaodong Xu, Chunxia Sun, Samreen Gillani, and Muhammad Ahsan Ali Raza. 2021. Role of Chinese government and Public–Private Partnership in combating COVID-19 in China. Journal of Management and Governance 27: 727–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Usman, Hamid Waqas, and Kashif Akram. 2021. Relationship between project success and the success factors in public–private partnership projects: A structural equation model. Cogent Business and Management 8: 1927468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadabadi, Ali Akbari, and Gholamreza Heravi. 2019. The effect of critical success factors on project success in Public-Private Partnership projects: A case study of highway projects in Iran. Transport Policy 73: 152–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Mohammed, Saeed, Colin Duffield, and Felix Kin Peng Hui. 2018. An enhanced framework for assessing the operational performance of public-private partnership school projects. Built Environment Project and Asset Management 8: 194–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinaitwe, Henry, and Robert Ayesiga. 2013. Success factors for the implementation of public-private partnerships in the construction industry in Uganda. Journal of Construction in Developing Countries 18: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Almarri, Khalid, and Halim Boussabaine. 2017. The Influence of Critical Success Factors on Value for Money Viability Analysis in Public-Private Partnership Projects. Project Management Journal 48: 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarri, Khalid, and Halim Boussabaine. 2023. Critical success factors for public–private partnerships in smart city infrastructure projects. Construction Innovation. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saadi, Rauda, and Alaa Abdou. 2016. Factors critical for the success of public–private partnerships in UAE infrastructure projects: Experts’ perception. International Journal of Construction Management 16: 234–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariño, Africa. 2003. Measures of strategic alliance performance: An analysis of construct validity. Journal of International Business Studies 34: 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, James E., and Maria May Seitanidi. 2012. Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses. Part 2: Partnership processes and outcomes. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 41: 929–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, Usama, Andrzej Kraslawski, and Janne Huiskonen. 2018. Governing Interfirm Relationships for Social Sustainability: The Relationship between Governance Mechanisms, Sustainable Collaboration, and Cultural Intelligence. Sustainability 10: 4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, Prof. 2018. Pendekatan Mudah SEM (Structural Equation Modeling). Available online: https://eprints.unisza.edu.my/3865/ (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Babatunde, Solomon Olusola, Akintayo Opawole, and Olusegun Emmanuel Akinsiku. 2012. Critical success factors in public-private partnership (PPP) on infrastructure delivery in Nigeria. Journal of Facilities Management 10: 212–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, Solomon Olusola, Srinath Perera, Lei Zhou, and Chika Udeaja. 2016. Stakeholder perceptions on critical success factors for public-private partnership projects in Nigeria. Built Environment Project and Asset Management 6: 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbie, Earl R. 2010. The Practice of Social Research, 12th ed. Boston: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Xuan, Shibin Sheng, and Julie Juan Li. 2016. Contract governance and buyer–supplier conflict: The moderating role of institutions. Journal of Operations Management 41: 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research. Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruch, Yehuda, and Brooks C. Holtom. 2008. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Human Relations 61: 1139–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisheim, Marianne, and Sabine Campe. 2012. Transnational public-private partnerships’ performance in water governance: Institutional design matters. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 30: 627–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, Lisa. 2015. Beyond relational contracts: Social capital and network governance in procurement contracts. Journal of Legal Analysis 7: 561–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, Matheus Leite, Cristiano Morini, Gustavo Herminio Salati Marcondes de Moraes, and Edmundo Inácio Júnior. 2018. A performance model for Public–Private Partnerships: The authorized economic operator as an example. Revista de Administração 53: 268–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakkol, Mehmet, Kostas Selviaridis, and Max Finne. 2018. The governance of collaboration in complex projects. International Journal of Operations and Production Management 38: 997–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Albert P. C., Patrick T. I. Lam, Daniel W. M. Chan, Esther Cheung, and Yongjian Ke. 2010. Critical success factors for PPPs in infrastructure developments: Chinese perspective. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 136: 484–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherednychenko, Olha O. 2015. Contract Governance in the EU: Conceptualising the Relationship between Investor Protection Regulation and Private Law. European Law Journal 21: 500–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Jui-Sheng, and Dinar Pramudawardhani. 2015. Cross-country comparisons of key drivers, critical success factors and risk allocation for public-private partnership projects. International Journal of Project Management 33: 1136–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Xuhui, and Li Ma. 2018. Performance evaluation of public-private partnership projects from the perspective of Efficiency, Economic, Effectiveness, and Equity: A study of residential renovation projects in China. Sustainability 10: 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dairu, A., and R. S. Muhammad. 2005. Critical Success Factors of Public-Private-Partnership Projects in Nigeria. ATBU Journal of Environmental Technology 8: 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- David, Fred R. 2013. Strategic Management Concepts and Cases (Global Edition), 14th ed. London: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Debela, Getachew Yilma. 2022. Critical success factors (CSFs) of public–private partnership (PPP) road projects in Ethiopia. International Journal of Construction Management 22: 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieleman, Marjolein, Daniel M. P. Shaw, and Prisca Zwanikken. 2011. Improving the implementation of health workforce policies through governance: A review of case studies. Human Resources for Health 9: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, Thomas, and Lee E. Preston. 1995. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Academy of Management Review 20: 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, Laura Hall, William A. Thomas Jr., Rakash Gaddam, and F. Douglas Scutchfield. 2013. The Relationship Between Local Public Health Agency Characteristics and Performance of Partnership-Related Essential Public Health Services. Health Promotion Practice 14: 284–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPEC. 2014. Managing PPPs during Their Contract Life: Guidance for Sound Management. Available online: http://www.eib.org/epec/resources/epec_managing_ppp_during_their_contract_life_en (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- EPU. 2020. Malaysia Economy in Figures. June. Available online: www.epu.gov.my (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Favoreu, Christophe, David Carassus, and Christophe Maurel. 2016. Strategic management in the public sector: A rational, political or collaborative approach? International Review of Administrative Sciences 82: 435–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Edward. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R. Edward, Robert Phillips, and Rajendra Sisodia. 2020. Tensions in Stakeholder Theory. Business and Society 59: 213–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazley, Beth. 2010. Linking collaborative capacity to performance measurement in government-nonprofit partnerships. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 39: 653–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyskens, Inge, Jan-Benedict E. M. Steenkamp, and Nirmalya Kumar. 2006. Make, buy, or ally: A transaction cost theory meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal 49: 519–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Tomas M. Hult, Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2013. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). In Sage Publication. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2014. Multivariate Data Analysis. In Pearson Education Limited, 7th ed. London: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, Hasnan, A. I. Che-Ani, and K. Ismail. 2017. Review of Issues and Challenges for Public Private Partnership (PPP) Project Performance in Malaysia. AIP Conference Proceedings 1891: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, Graeme A., and Carsten Greve. 2017. On Public—Private Partnership Performance: A Contemporary Review. Public Works Management and Policy 22: 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, Chuen-Ming, and Luh-Maan Chang. 2017. Critical success factors for PPP infrastructure: Perspective from Taiwan. Journal of the Chinese Institute of Engineers 40: 370–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Bon-Gang, Xianbo Zhao, and Mindy Jiang Shu Gay. 2013. Public private partnership projects in Singapore: Factors, critical risks and preferred risk allocation from the perspective of contractors. International Journal of Project Management 31: 424–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. 2019. 2016 Article IV Consultation—Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Malaysia. In IMF Country Report No. 19/71. (Issue March). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, Suhaiza. 2013. Critical success factors of public private partnership (PPP) implementation in Malaysia. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration 5: 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Suhaiza, and Fatimah Azzahra Harris. 2014. Challenges in Implementing Public Private Partnership (PPP) in Malaysia. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 164: 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinarat, Veerasak, and Truong Quang. 2003. The impact of good governance on organization performance after the Asian crisis in Thailand. Asia Pacific Business Review 10: 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Thomas M., Andrew C. Wicks, and R. Edward Freeman. 2002. Theoretical and Pedagogical Issues Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art. In The Blackwell Guide to Business Ethics, 1st ed. Edited by N. E. Bowie. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, Karl G., and Dag Sörbom. 1993. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Lincolnwood: Scientific Software International, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kataike, Joanita, and Xavier Gellynck. 2018. 22 years of governance structures and performance: What has been achieved in agrifood chains and beyond? A review. Agriculture 8: 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavishe, Neema, and Nicholas Chileshe. 2019. Critical success factors in public-private partnerships (PPPs) on affordable housing schemes delivery in Tanzania: A qualitative study. Journal of Facilities Management 17: 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Claire. 2012. Measuring the Performance of Partnerships: Why, What, How, When? Geography Compass 6: 149–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körs, Anna. 2019. Contract governance of religious diversity in a German city-state and its ambivalences. Religion, State and Society 47: 456–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshreshtha, Rakesh, Anil Kumar, Ashish Tripathi, and Dinesh Kumar Likhi. 2017. Critical Success Factors in Implementation of Urban Metro System on PPP: A Case Study of Hyderabad Metro. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management 18: 303–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Chandan. 2018. Effects of Contract Governance on Public Private Partnership (PPP) Performance. Available online: http://www.igidr.ac.in/pdf/publication/WP-2018-014.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Kwofie, Titus Ebenezer, Samuel Afram, and Edward Botchway. 2016. A critical success model for PPP public housing delivery in Ghana. Built Environment Project and Asset Management 6: 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Bing, Akintola Akintoye, Peter J. Edwards, and Cliff Hardcastle. 2005. Critical success factors for PPP/PFI projects in the UK construction industry. Construction Management and Economics 23: 459–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Linlin. 2017. Improvement in the law on farmland transfer in China from a contract governance perspective. Journal of Chinese Governance 2: 169–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Yanhong, and Hongdi Wang. 2019. Sustainable performance measurements for public–private partnership projects: Empirical evidence from China. Sustainability 11: 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]