Abstract

A credit default swap (CDS) is a derivative financial instrument that provides insurance against credit risk. CDSs on subprime Asset Backed Securities (ABSs) paved the way for securitizers to hedge the credit risk of the underlying subprime loans during the onset of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Thus, mortgage originators were least concerned about the quality of loans they securitize since they could hedge the default risk via CDS, paving way to a moral hazard concern. We argue that the core issue pertaining to CDSs, moral hazards, remains unattended even after a decade since the GFC. This paper, utilizing a lexonomic approach embedded in the second-best efficiency criteria, examines the mechanism behind a CDS and develops a regulatory framework with the view of minimizing moral hazards associated with CDSs. Our analysis indicates that incorporating an ‘excess’ on CDSs may minimize moral hazards, since originators are compelled to bear part of the risk associated with assets they create.

1. Introduction

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) has been identified as the largest banking crisis since the great depression (Acharya et al. 2013) and one of the most significant economic events that took place within the last 50 years of financial history (Allen et al. 2011). Scholars are not hesitant to submit that the GFC of 2007/8 was no accident, while emphasizing much of the blame on CDSs (Swan 2009; Arentsen et al. 2015; Purnanandam 2011; Mian and Sufi 2009; Keys et al. 2010; Senarath 2017; Rajapakse and Senarath 2019).1

In 2002, Warren Buffett identified CDSs as ‘financial weapons of mass destruction’ (Buffett 2002, p. 11). By 2007, CDSs triggered the effects of defaults and facilitated the GFC (Fostel and Geanakoplos 2012). CDSs ease creditors to hedge borrower credit risk (Fuller et al. 2018). Moreover, CDSs weakens creditors’ incentive to monitor borrowers (Kim et al. 2018) and hence can result in excessive risk taking (Baluch et al. 2011). Inter alia, CDSs result in the reduction in the cost of capital to firms, the market-wide efficient allocation of capital, enhanced transparency in pricing risk and, ultimately, should result in efficient financial markets (Angelini 2012). According to the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA), CDSs result in strengthening the financial system in four broader means (ISDA 2018).2

In July 2009, Barney Frank, the Chairman of the United States House of Representatives Financial Service Committee, indicated a prohibition of naked CDSs. Soon after, on 10 March 2010, the president of the European Commission advocated a ban on naked CDSs (Mosinsky and Kirchfeld 2010). The European Union, on 1 November 2012, banned trading in the sovereign CDS market unless investors also buy the underlying bonds (Danis and Gamba 2018). Regulation (EU) No. 236/2012 was introduced as the first worldwide uncovered CDS regulation. It prohibits buying uncovered sovereign CDS contracts in the European Union (Kiesel et al. 2015).

In a broader sense, a CDS is a derivative financial instrument (Saunders 2010). In simple terms, a CDS is an agreement between two parties whereby one party agrees to pay a certain amount in the case of a specific credit event (Stulz 2010). Even though CDSs are not treated as insurance, perhaps deliberately, a CDS operates similar to a typical insurance contract. Hence, arguably, CDSs provide ‘insurance’, which can perhaps be called ‘protection’, against default risk (Senarath and Copp 2015). Similar to an insurance contract, in a CDS, the lender of money buys ‘insurance’ against the default of the borrower (Ali et al. 2015). The party who buys the protection, known as the protection buyer, pays a spread to the party who sells the protection, known as the protection seller. In case of a credit event, pertaining to the reference obligation, the protection seller compensates the protection buyer (Shadab 2010; Johnson 2011; Brandes 2008).3 A CDS is called a ‘covered CDS’ if the protection buyer is the owner of the bond, or else is called ‘naked’ if the protection buyer is not the owner of the bond in question (Posner and Weyl 2012). CDS providers prefer naked CDSs since they can collect ‘easy money’ in terms of spread (Sjostrom 2009).4 Credit default swaps are privately negotiated bilateral agreements traded over the counter (Partnoy and Skeel 2006) and thus are largely unregulated financial derivatives and are not governed by a set of well-defined regulations or by an authority (Juurikkala 2012).

Since insurable interest is not a must for a CDS, there can be multiple ‘insurance’ over the default of a specific entity. Hence, the total value of CDS contacts can (and do) exceed the actual value of underlying debts on which they are built upon (Posner and Weyl 2012; Calice et al. 2013). In case of a credit event, the actual amount of compensation can be several times higher than the actual value of the debt instrument (Legg and Harris 2009; Shadab 2009). In years prior to the GFC, CDSs replaced their traditional association with bonds with Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) and similar asset-backed securities (Stulz 2010). When subprime borrowers started defaulting, CDS sellers had to pay gigantic amounts of compensation to protection buyers, and hence, CDS sellers went undercapitalized (Rowe 2011; Arentsen et al. 2015). Some big institutions went bankrupt, whereas some (e.g., American International Group (AIG)) which were ‘too big to fail’ were bailed out (Shadab 2010).

This paper argues that the post-GFC literature focussing on CDSs fails to address the moral hazard concern inherently embedded in CDSs. As Fuller et al. (2018) and Kim et al. (2018) identify, CDSs deteriorate a creditor’s incentive to monitor borrowers, since the risk can be shifted to a third party. Even though the post-GFC literature attempts to regulate CDSs in numerous means, the literature fails in addressing the core concern associated with CDSs, the issue of the moral hazard. Hence, the objective of this analysis is to enhance the current literature by providing a ‘skin-in-the-game’ solution embedded in the second-best efficiency criterion via suggesting an ‘excess’ for protection buyers.

This study is significant to the extent that it attempts to regulate CDSs such that benefits associated with CDSs remain. The suggestions made in this paper, inter alia, discourage protection buyers from taking excessive risk, while encouraging them to engage in monitoring their borrowers. In this analysis, the emphasis is on the role of CDSs with respect to subprime mortgage-backed securities. We do agree with the fact that, in reality, CDSs have a rather broader, and perhaps traditional, focus as a means of insuring against debt defaults. For instance, before lawyers and politicians started to meddle with the CDS market, CDSs were generally acknowledged as a more efficient way of pricing credit and related risks for corporate debt than debt was itself (and even now, for liquid issues, that continues to be the case). There is a legitimate role for CDSs as a more standardized instrument, and to provide a vehicle for shorting credit risk. Although we do not identify our suggestions alone as complete nor coherent, we intend to initiate a discussion on a ‘skin-in-the game’ solution for moral hazard concerns pertaining to CDSs and similar financial instruments, and hence this analysis is directed towards formulating an argument on the same.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 of the paper is the literature review. The emphasis is, inter alia, on a post-GFC regulatory solution for CDSs. Section 3 describes the methodological approach for the analysis. Section 4 analyzes the mechanism behind a typical CDS and suggests how it should be regulated such that associated moral hazards are minimized. Section 5 is the conclusion.

2. Literature Review

The focus of this literature review is twofold. Accordingly, this literature review attempts to review the literature with the view of (i) identifying the manner in which CDSs contributed to the GFC, and (ii) identifying solutions provided in the post-GFC literature with the view of regulating existing mechanism behind CDSs.

Much of the post-GFC literature on CDSs debates the question of whether CDSs can be considered insurance or not. Even though this argument is of lesser concern for our analysis, the notable point is that scholars hesitate to treat CDSs as insurance mainly due to the fact that CDSs do not require insurable interest (Stulz 2010; Schwartz 2007; Brandes 2008; Baluch et al. 2011). Angelini (2012) argues that lenders are likely to maintain risky credit portfolios since they can hedge risk via CDSs, giving rise to a moral hazard concern. Rowe (2011) is with the view that defaults in CDSs are inevitable in economic recessions and thus affect the financial stability of major financial entities. Chen et al. (2013) identifies that, in contrast to traditional insurance (insurance with insurable interest), CDSs may lead to systemic risk during economic recessions and thus create systemic risk while triggering a cascading chain of reactions in a financial system. Posner and Weyl (2012) are also with the view that, although insurance reduces risk, CDSs may result in systemic risk in financial markets. Subrahmanyam et al. (2014) states that CDSs increase the probability of bankruptcy. According to Barth et al. (2008), predominantly in systematic situations, systemic risk is a key concern of governments since the social costs of a financial failure tend to exceed the private costs.

As far as the post-GFC solutions focusing on regulating CDSs are concerned, a bulk of the literature on CDSs focuses on prudential regulation and disclosure requirements. Sharma (2013) pays emphasis to prudent supervision as the prime means of regulating CDSs. Angelini (2012) and Saunders (2010) identify the need for a derivative register and mitigating counterpart risks, and Cerulus (2012); Schmaltz and Thivaios (2014); and Cont and Kokholm (2014) emphasize the need for a clearing house and central clearing requirements for CDSs.5 Cont and Minca (2016) prove that the central clearing of CDSs, through a well-capitalized central counterparty clearing house, can reduce the probability and the magnitude of a systemic illiquidity spiral by reducing the length of the chains of critical receivables within the financial network. Rao et al. (2012) discusses risk management procedures associated with CDSs, and Juurikkala (2012) highlights the need for regulating short selling. Posner and Weyl (2012) suggest the need for a state agency that can decide whether a particular financial instrument may or may not enter into the market. McIlroy (2010); Berndt and Gupta (2009); and Jarrow (2011) argue for stricter collateral and higher equity capital for CDSs. Many of the scholars are with the view that CDSs should be regulated and do not hesitate to emphasize the need for banning naked CDSs (Juurikkala 2012; Young et al. 2010; McIlroy 2010; Blakey 2013).

As per this literature review, we point out that (i) CDSs are a form of insurance that lack insurable interest and indemnity; (ii) CDSs result in systemic risk, and that is due to the fact that CDSs lack insurable interest (and thus used for betting); and, (iii) as far as solutions are concerned, the incorporation of insurable interest (ban on naked CDSs) and capital requirements are prominent suggestions. We argue that the literature fails to identify a skin-in-the-game solution that addresses the moral hazard issue associated with CDSs.

As we have already discussed, a CDS on subprime asset-backed securities pave the way for securitizers to hedge the credit risk of the underlying subprime loans. Originators (e.g., banks and other mortgage providers) can limit, or perhaps completely clear, their exposure to securitizations of risky loans, and thus they are less concerned about the decline in the credit quality of loans they make (and securitize), while earning lucrative fees and commissions. Banning naked CDSs solves one part of the predicament and yet is an essential must. Prudential regulation (nor banning naked CDSs), on the other hand, works as a defence against an originator’s motive to grant low-quality (subprime) mortgages and to securitize the same. We urge for a mechanism that can ‘hurt’ the originators in the case of a default of a loan they have made. The post-GFC literature fails to address the very same issue. In addressing this gap in the literature, we model the mechanism of a CDS and attempt to regulate CDSs in light of legal and economic theory.

3. Methodology

This paper adopts an economic-analysis-of-law or ‘lexonomic’ approach embedded in the second-best efficiency criteria following the work of Quah and Mishan (2007), Little (2002), Kolsen (1968) and Posner (2014). Accordingly, this paper analyzes actual CDS arrangements, existing regulations, market norms and practices employed by stake holders pertaining to CDSs and transactions of the same. Such are then compared against theoretically optimal contracting and regulatory arrangements derived from the legal and financial economics literature, which are used as benchmarks for the analysis. Significant shortfalls between actual and theoretically optimal arrangements form the basis of recommendations for reform to law or practice, either in the interest of ‘better’ contractual design or (perhaps) more effective regulatory design, whether within or between jurisdictions. The formulated benchmark (or, in other words, the theoretically best provisions) may not be achievable in the practical world due to constraints (e.g., consumer protection considerations). Thus, this analysis essentially follows the second-best efficiency criteria. This analysis is developed based on the farmework followed by Shavell (1979).

4. Model and Discussion

As per the literature review, we identified that CDSs contributed to the GFC due to regulatory arbitrage opportunities that arose from the practice of trading CDSs. In this analysis, we recommend a ‘skin-in-the-game’ solution to regulate CDSs to prevent ‘betting’ using CDSs and systemic risk arising with the current practice of CDSs. As we have identified, the post-GFC literature fails to address the moral hazard issue arising from the originate-to-distribute model.6 As we have already identified, the vital problem is that the lender is least anxious about the quality of the loan that he or she makes, knowing the fact that loans are for sale but not to retain. This gives rise to an information asymmetry that results in a moral hazard problem.

Protection sellers have no information about the underlying mortgages of the security they insure. The protection seller relies only on the rating granted on the security (Senarath and Copp 2015).7 Initial lenders (for example, banks), on the other hand, can grant loans to less credit-worthy borrowers, also known as subprime borrowers, or alternatively to banks (or lenders). In accordance with traditional banking practices, they do not engage in screening (before granting a loan) or monitoring (after granting a loan) of the borrower, which is cost effective for the lender. The situation can become worse if those ‘lemon’ loans8 are securitized and sold to investors around the world.

A development in the modern insurance industry addresses the moral hazard concern associated with CDSs. For example, regardless of how much a person cares about any physical damage that can occur due to an accident, legal consequences and any sentimental value he or she has on a car, a person who has purchased an all-inclusive ‘full-insurance’ cover for a vehicle has little incentive to be vigilant on the road, giving rise to a moral hazard concern. As we have discussed, in economic theory, the best solution (theoretically optimal) from the point of view of the insurance provider is a situation where the driver gives maximum care in driving the car. However, in practical terms, since the insurer cannot observe the driver (the constraint), achieving the theoretically optimal situation is not achievable, forcing us to look for a second-best solution.

As far as CDSs are concerned, a moral hazard refers to the tendency of the insurance protection (in this case, the CDS cover) to alter the insured’s motive to prevent a loss. The literature identifies two solutions to this problem. The first, as we have identified above (and perhaps the first best), is ‘observation’ by the insurer about the care taken by the insured to prevent a loss. Second, there is what is referred to as ‘incomplete coverage’ (also referred as deductive and/or excess) (Arrow 1992). Incomplete coverage provides a motive for the insured to prevent a loss by exposing him or herself to a ‘portion’ of risk, in other words, keeping his or her ‘skin-in-the-game’. The application of partial coverage, hereinafter called ‘excess’, is justified in situations where observation is impossible and/or too expensive (Shavell 1979).

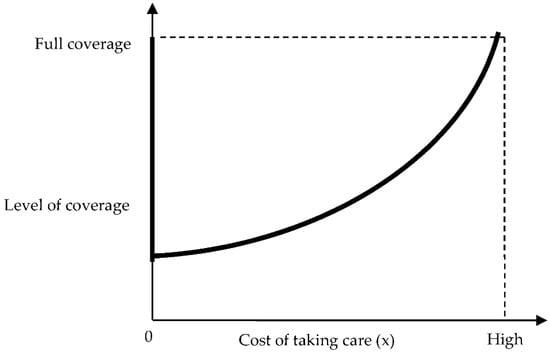

The other concern in this situation is the nature of the ‘cost of taking care’ for the insured. The incentive created to exercise care depends on the cost of taking care for the insured. The effectiveness of an excess depends on the incentive created to exercise care. The logic is that, when the cost of taking care is very low (perhaps zero, which means no cost is incurred for the insured to take care, hence minimizing the possibility of an accident), partial coverage is desirable. In contrast, if the cost of taking care is very high, then full coverage is desirable. However, the moral hazard cannot eliminate insurance. This is due to the fact that, when the cost of care approaches zero, the optimal level of coverage, although partial, approaches full coverage (Shavell 1979) (See Figure 1).9 From the insurer’s point of view, if observations are perfectly accurate, given that the cost of observation is little and that observation is possible, full coverage is desirable. However, on the other hand, as we have already noted, if it is costly for the insurer to observe and/or if information is less accurate, a partial solution is desirable.

Figure 1.

Level of coverage.

As far as CDSs are concerned, it is rather logical to assume that it is almost impossible for the CDS provider to engage in monitoring the initial borrower (the borrower that the bank lends to, e.g., a mortgage loan). As far as banks are concerned, banks are in the best position to monitor their borrowers (pre and post-lending), which is actually (it used to be) the situation under ‘originate-to-hold’ lending. Adopting Shavell’s model, we argue that it is best to employ ‘partial coverage’ when it comes to CDSs.

4.1. First-Best Solution

Let us assume an omniscient and benevolent dictator. Let us consider the manner in which the omniscient dictator would solve the moral hazard associated with insurance. The dictator would come up with a Pareto-efficient solution.

Let:

The Pareto-optimal solution can be found as follows. In a competitive insurance market with risk-neutral insurers, the premium must be equal to the expected loss. In other words, the premium is actuarially fair. Therefore, the Pareto-efficient allocation is found by finding the level of coverage, which maximizes the expected utility of the insured. However, the expected utility of a risk-adverse individual facing actuarially fair insurance is maximized when the individual purchases full insurance. Hence, the expected payoff of the insured in the Pareto-optimal situation is simply

This expression is maximized by minimizing , the solution to which obeys

In this expression, the Pareto-optimal level of care equates the marginal cost of care (r) with the marginal benefit of care, which is the marginal reduction in expected losses

The point x* is the level of care observable by the omniscient and benevolent dictator. In this case, the insurance premium should be , where the coverage is the same as the loss ().

4.2. Second-Best Solution

Some insurance providers who are engaged in the motorcar insurance industry adopt the concept of an ‘excess’ to address the moral hazard issue associated with insurance. Accordingly, the insurer imposes a lower limit of compensation. For example, any damage under 100 USD is not compensated. If the damage exceeds 100 USD, (for example, the damage is 5000 USD), then the insurer pays an amount that is equal to the damage minus the excess. In this case, it is 4900 USD (5000–100 USD). As a result of this, the car owner knows that, in case of damage, he or she also has a cost of 100 USD. Hence, a person who purchases all-inclusive full insurance coverage with an excess tends to be cautious (more than he or she used to be) while driving. This may be (and obviously is not) the best solution for the moral hazard associated with insurance. However, it is one of the second-best solutions available.

The general problem for the insured is:

The first order necessary condition is:

Now:

We can write welfare as a function of the extent of coverage:

The change in welfare with respect to the optimal level of coverage is:

This can be re-written as:

However, the first-order condition for the individual’s level of care obeys the following expression:

Therefore, we must have:

At the optimal level of coverage, this must be equal to zero, so we must have:

or

We therefore have the following:

Proposition 1.

In the presence of a moral hazard, and under the assumption that the insurer’s expected profits are zero, a deductible or excess is optimal, i.e., the optimal level of coverage is less than the full amount of the loss, , i.e., .

Proof.

Under the assumption that the insurer’s expected profits are zero, we have . Hence, we have . Since and , we have , and hence . Hence, as well, and so:

Hence,

Therefore:

However, this implies that:

In the presence of risk aversion, this in turn implies that:

Therefore:

□

General implication: If the insurer cannot observe or monitor the insured’s level of care (and cannot charge a premium on the basis of care), then, in the second-best situation, the insured should share some of the risk in the form of an excess.

Thus, the optimal amount of excess depends on (i) the cost of taking care for the insured, (ii) the size of the loss, (iii) the degree of risk aversion in terms of the insured and the insurer and (iv) the possibility of a loss (x).

This same analogy can be applied to the CDS business. As we have identified above, the best possible and theoretically optimal solution is a situation where the lender, prior to accepting the loan application, engages in thorough screening on the borrower and his or her credit history, and then, in a post-lending scenario, the lender engages in monitoring the borrower. This minimizes the default risk. However, the insurer is not capable of monitoring the lender and cannot observe whether the lender engages in screening and monitoring in pre and post-lending scenarios. The insurer can only engage in monitoring at a very high cost, which then is not efficient.

The second-best alternative we have is to ensure that the bank performs some screening and monitoring, in contrast to zero screening and monitoring. The protection buyer can impose an excess on protections that he or she undertakes. This can be a percentage of the face value of the mortgage or a flat amount. However, our discussion needs emphasis that is more practical. Lenders earn interest by granting loans, which ties up their capital for the loan period. If the excess amount is too low and surpasses how much the lender can receive from the loan, the lender continues to execute that loan. For example, if the lender is with the view that the borrower will default in 5 more years, by which the bank can earn 100,001 USD, which is beyond the excess amount of 100,000 USD, the lender would not hesitate to approve the mortgage. The argument is that the presence of a ‘sufficient excess’ tends to make the lender vigilant or more so than he or she used to be regarding lending. This moderately excludes the moral hazard issue incorporated with CDSs. The concept of excess allows the insurer to make sure that the insured has ‘skin-in-the-game’ and does not voluntarily engage in excessive risk taking at the insurer’s expense.

As evidenced by the pre-GFC literature, the perceived probability of a credit event remained significantly low. For example, AIG believed that the probability of a CDS-related credit event was only 0.15 percent (Sjostrom 2009). If the insured incorrectly perceives risk and has a moral hazard, then this has important implications for the optimal degree of coverage and for the size of the deductible or excess. We now analyze the following case. Suppose that the actual probability of a default is , and the insured’s perceived probability is , where α < 1.

The general problem for the insured is now:

The first-order necessary condition is now:

Note that this is identical to our previous expression when .

Rearranging this expression gives:

Hence, we have;

Now:

Hence, a reduction in the perceived risk (a reduction in ) leads to a lower level of care. It follows from the fact of that, to restore care to the second-best level, a lower level of coverage is required.

To see this, note that the expression for the optimal level of coverage is:

However, as we have discussed above, if the probability of harm is misperceived, we must have:

Therefore, at the second-best level of q, when , we must have:

Since , this implies that

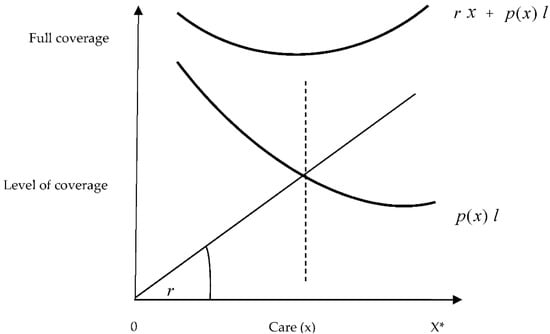

This then implies that the optimal level of coverage is lower, and the lower level is (see Figure 2). Hence, the greater level is the degree of misperception of risk, and the higher level is the optimal deductible. If the perceived risk is significantly lower than the actual risk, the CDSs that are insured do not expect to have a likely default for the insurance they undertook. As a result, CDS insurance obligations are not re-insured, no capital is maintained to meet up with the likely loss and there is no insurable interest on those CDS contracts. Therefore, there are many entities (without insurable interest) gaining insurance protection against one credit event.

Figure 2.

Optimum level of coverage.

4.3. Externalities

A final argument in favor of deductibles is that a default may produce systemic risks—in other words, it may result in externalities to the economy at large. To see this, assume now that greater care by the insured also reduces the probability of a systemic loss to the rest of the economy. Welfare is now:

where , and . Here, is the external benefit provided by the insured’s level of care, and is a scaling parameter to allow for different possibilities. The case where corresponds to the case where there is no systemic risk.

The expression for the optimal level of coverage now obeys:

Since B′ > 0 and x′ < 0, this then implies that , which implies that the optimal level of coverage is lower than the second-best level found when there is no systemic risk.

4.4. Unfolding the Story behind AIG

Founded almost a century ago, AIG was one of the largest insurance companies in the world with AAA credit ratings. The innovative solution that AIG came up with was the sale of CDSs to financial institutions. AIG provided an unconditional guarantee for financial products and thus inherited its AAA ranking for its transactions as well. AIG earned 0.02 USD per year for every 1 USD they insured. AIG had a confidence level of 99.85 percent that the super senior tranches (AAA rated) that they insured could not default. As a result, by late 2007, AIG had given 230 billion USD protection on corporate loans and 149 billion USD on residential mortgages. For AIG, CDSs were ‘gold’ and ‘free’ money (Sjostrom 2009). Among the four main business units of AIG, Financial Services dealt with the CDS business. In 2007, AIG suffered a loss of 9515 million USD on losing bets on CDSs; the same bet had given them a profit of 4424 million USD in 2005. According to the AIG calculation, the possibility of a default was 0.15 per cent, which was crystallized in 2007 (AIG 2011; SEC 2012; Sjostrom 2009; Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission 2011).

Going back in time, if AIG declared bankruptcy in 2007, that would have led to a chain of nationwide (and then global) bankruptcies. The financial safety of the protection seller (provided that the protection seller is a considerably larger entity like AIG) can trigger systemic risk.10 As we have identified in the literature review, the post-GFC literature, inter alia, emphasizes the need for capital requirement for protection sellers, regulating CDSs as insurance while incorporating insurable interest into CDSs, the need for a regulator to oversee the protection seller, prudential regulation central clearing, a derivative register, etc. We are with the view that insurable interest is necessary for CDSs, and incorporating other principles of insurance (i.e., re-insurance) can spread the risk, in contrast to risk contraction. Although we agree that all such recommendations are positive and are worth considering, we argue that none of the above recommendations alone truly address the core concern of the creation of lemon mortgages and securitizing and insuring them with CDSs. To the extent that the originate-to-distribute model is in operation, there is nothing that prevents a lender from creating lemon assets. Our recommendation of excess is a skin-in-the-game solution, in which the leader also suffers a loss if he or she creates lemon mortgages.

4.5. Implications and Further Research

We are with the view of the post-GFC recommendation, i.e., insurable interest should be imposed on CDSs. Hence, there are no naked CDSs in the market, and betting is avoided. Our recommendation may result in a number of implications in the market. Inter alia, lenders may have to engage in screening and monitoring loans for which they wish to gain CDS protection. This increases the cost of granting a loan, which cuts down marginal loans with less profitability to the lender under the new structure. Lenders are discouraged from granting subprime mortgages, which might negatively affect the welfare policies of policy makers. However, we are with the view that granting subprime mortgages to enhance house ownership should be dealt separately as a welfare scheme but should not be merged with financial transactions.11 Another argument that may arise is the fact that insurance-style excess can tend to reduce transparency in the market, which can likely pose an obstacle to trading.

The issuance of asset-backed securities, especially mortgage-backed securities, may decline due to the fact that only ‘non-lemon’ mortgages can build securities afterwards. Interest rates might increase (arguably), since the cost of making and maintaining a loan becomes slightly higher. Free and easy money for CDS sellers is dried-up, making an end to betting via CDSs. The average time taken for granting a loan may marginally increase due to enhanced screening requirements. Securities protected under CDSs are high in quality. Long-term stability in the securitization market is established, posing comparatively less systemic risk to the financial system.

According to the loan pricing theory, an adequate interest rate (on loans) must remunerate not only the expected loss but also the unexpected loss, in order to properly reward the bank’s stakeholders. The income in the absence of a loss (w) can be modeled considering the appropriate pricing formula and hence various risk factors, including, inter alia, the probability of default, the recovery rate, the maturity, the exposure in the event of default, the regulatory capital requested, the risk-free rate, the cost of the economic capital and the remuneration for the unexpected loss (the cost of the economic capitalegulatory capital). This is left for future research to model regarding the impact of the “Skin in the Game” in a much more sophisticated manner.

Determining the optimal leave of excess is more of an empirical task. A number of factors may affect the decision of the optimal level of excess and may vary from country to country.12 Calculating the excess for CDSs is no easy task, yet it needs careful examination, research and empirical analysis, which we leave for future research.

5. Conclusions

CDSs, which lack insurable interest and which provide protection against credit risk, have effectively been used for ‘betting’ against the credit worthiness of a borrower in the onset of the GFC_2017/8. Provided that CDSs do not require insurable interest, there can be a number of protection buyers who purchased protection over a specific credit event. Years prior to the GFC, CDSs replaced their traditional association with bonds with CDOs and asset-backed securities. When interest rates started increasing and subprime borrowers started defaulting, both naked and covered protection buyers claimed compensation. Protection sellers, who had neither sufficient liquid collateral nor re-insurance protection arrangements to mitigate risks, were pulled into financial distress. As a result, a number of ‘big’ institutions were dragged towards bankruptcy. Some institutions that were ‘too big to fail’ were bailed out using billions of taxpayer money. As a result, a chain of bankruptcies followed by an economic downturn spread across the globe.

The GFC revealed the need for regulatory solutions for CDSs, which were not regulated much. CDSs coupled with securitization-based notes accumulated a massive amount of risk in the financial system. While deviating from the conventional approach of regulating CDSs, this paper emphasizes the need for CDSs to be regulated in a similar manner to that of insurance in order to prevent a similar devastating financial crisis. This research, inter alia, brings the concept of excess, which should ‘hurt’ the originator in the case of a default of a loan that he or she has made, into the proposed regulatory suggestions for CDS, adding a further step in the existing literature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., P.R. and J.J.d.V.R.; Methodology, S.S.; Formal Analysis, S.S.; Validation, S.S.; Project administration, S.S.; Investigation, S.S.; Visualization, S.S., P.R. and J.J.d.V.R.; Writing—review & editing: N.W. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 | For example, see discussions made in Swan (2009), Arentsen et al. (2015), Purnanandam (2011), Mian and Sufi (2009), Keys et al. (2010), Senarath (2017) and Rajapakse and Senarath (2019). |

| 2 | As of 3 June 2016, the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) identified four broader means by which CDSs can benefit the financial system. Accordingly, they can enable banks to transfer risk to other parties, which makes banks capable of making more loans; result in distributing risk widely throughout the system and hence prevent risk concentration; provide significant signals about credit conditions, helping bankers and policymakers to supervise traditional banking activities; and act as a signaling function, [and thus] CDS prices produce better and timelier information. |

| 3 | Regarding the termination of a CDS, all CDSs provide two mutually exclusive scenarios. (i) The termination of a CDS is not triggered. In this case, the CDS agreement continues until maturity. (ii) The termination of a CDS is triggered by a credit event. In this situation, the protection seller physically swaps the agreement. |

| 4 | In addition, we should also note that, in the pre-GFC context where the economy was growing, corporate bankruptcies were infrequent, the housing market was booming and consumers were spending. CDSs were seen as a low-risk method to generate cash (Young et al. 2010). As per the risk models indicated, prior to the GFC, it was the belief that underlying securities would never go into default, thus providing CDSs against such securities in ‘free money’ for protection sellers (Sjostrom 2009). |

| 5 | The U.S Treasury Department in June 2009 proposed mandatory central clearing for standardized CDS contracts and prudential (bank-like) regulation of major CDS market participants together with enhanced transparency and record-keeping requirements for all CDS transactions (Shadab 2009, 2010). |

| 6 | The originate-to-distribute model of lending, where the originator of a loan sells it to a third party, was a popular mechanism prior to the onset of the subprime crisis. A number of post-GFC scholars state that the originate-to-distribute model results in information asymmetry and ultimately leads to moral hazards (Berndt and Gupta 2009; Acharya et al. 2010; Purnanandam 2011). |

| 7 | The role of the rating agencies in an ex-ante GFC context was subjected to immense criticism by post-GFC scholars. Rating agencies were paid by originators, leading to a conflict of interest. On the other hand, asset-securitization schemes structured asset tranches in such a (complex) manner that senior securities were able to gain the highest rating disregarding the nature of underling assets. Thus, ratings granted on securities were identified as “unreal” or “unreliable” by a number of scholars in ex-the post-crisis literature. See, for example, (Peicuti 2013; Crotty and Epstein 2009; Sykes 2010). |

| 8 | Ever since Akerlof (1970) used the term “Lemon” to identify “bad” cars in the second-hand car market, the word lemon has been used with the meaning “inferior” in the economic literature. Following the tradition, we use the word lemon to refer to subprime mortgages. |

| 9 | Whether the graph is a straight line, concave or convex is a separate question. For the purpose of this analysis, we do not put emphasis on the shape of the curve. |

| 10 | Inter alia, this appears to be one good reason why the U.S. government did not let AIG fall into bankruptcy. If one large financial entity goes bankrupt, it can lead to a chain of bankruptcies. |

| 11 | We are with the view that subprime mortgages should not be securitized. If the government needs to enhance the home ownership of a low-income-earning segment, the government is free to do so for a welfare plan but not to securitize such loans under the normal financial channels. |

| 12 | It is noteworthy that a car insurer may consider a number of items before deciding the excess, for example, the age of the driver, his or her driving history, the crime rate of the suburb where the car is usually parked, etc. |

References

- Acharya, Viral V., Philipp Schnabl, and Gustavo Suarez. 2013. Securitization without risk transfer. Journal of Financial Economics 107: 515–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, Viral V., Thomas Cooley, Matthew Richardson, and Ingo Walter. 2010. Manufacturing Tail Risk: A Perspective on the Financial Crisis of 2007–2009. Foundations and Trends in Finance. Delft: Now Publishers Inc., vol. 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, George Arthur. 1970. The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. Quarterly Journal of Economics 84: 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Paul, Jesse Jager, and Ian Ramsay. 2015. Legal Considerations for Superannuation Investors When Investing in Complex Financial Products. CIFR Paper No. 079/2015. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2667335 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Allen, Franklin, Elena Carletti, and Agnese Leonello. 2011. Deposit insurance and risk taking. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 27: 464–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American International Group (AIG). 2011. Annual Report. New York: American International Group. Available online: http://www.aig.com/content/dam/aig/america-canada/us/documents/investor-relations/2011-10k-report.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2020).

- Angelini, Eliana. 2012. Credit Default Swaps (CDSs) and Systemic Risks. Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing 8: 880. [Google Scholar]

- Arentsen, Eric, David C. Mauer, Brian Rosenlund, Harold H. Zhang, and Feng Zhao. 2015. Subprime Mortgage Defaults and Credit Default Swaps. The Journal of Finance 70: 689–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, Kenneth J. 1992. Insurance, risk and resource allocation. In Foundations of insurance Economics. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 220–29. [Google Scholar]

- Baluch, Faisal, Stanley Mutenga, and Chris Parsons. 2011. Insurance, systemic risk and the financial crisis. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice 36: 126–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, James R., Gerard Caprio, and Ross Levine. 2008. Rethinking Bank Regulation: Till Angels Govern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, Antje, and Anurag Gupta. 2009. Moral hazard and adverse selection in the originate-to-distribute model of bank credit. Journal of Monetary Economics 56: 725–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakey, James. 2013. Tax Naked Credit Default Swaps for What They Are: Legalized Gambling. University of Massachusetts Law Review 8: 136. [Google Scholar]

- Brandes, Ari J. 2008. A better way to understand the speculative use of credit default swaps. Stanford Journal of Law, Business & Finance 14: 263–304. [Google Scholar]

- Buffett, Warren. 2002. Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report. Berkshire Hathaway Chairman’s Letter, February 21. [Google Scholar]

- Calice, Giovanni, Jing Chen, and Julian M Williams. 2013. Are there benefits to being naked? the returns and diversification impact of capital structure arbitrage. The European Journal of Finance 19: 815–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cerulus, Stan. 2012. Central clearing for credit default swaps. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 20: 212–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Fang, Xuanjuan Chen, Zhenzhen Sun, Tong Yu, and Ming Zhong. 2013. Systemic risk, financial crisis, and credit risk insurance. Financial Review 48: 417–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cont, Rama, and Andreea Minca. 2016. Credit default swaps and systemic risk. Annals of Operations Research 247: 523–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cont, Rama, and Thomas Kokholm. 2014. Central clearing of OTC derivatives: Bilateral vs multilateral netting. Statistics & Risk Modeling 31: 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Crotty, James, and Gerald Epstein. 2009. Avoiding another meltdown. Challenge 52: 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danis, Andras, and Andrea Gamba. 2018. The real effects of credit default swaps. Journal of Financial Economics 127: 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. 2011. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report, Authorized Edition: Final Report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States; Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Fostel, Ana, and John Geanakoplos. 2012. Tranching, CDS, and asset prices: How financial innovation can cause bubbles and crashes. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 4: 190–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, Kathleen P., Serhat Yildiz, and Yurtsev Uymaz. 2018. Credit default swaps and firms’ financing policies. Journal of Corporate Finance 48: 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISDA (International Swaps and Derivatives Association). 2018. “Credit Default Swaps” ISDN. Available online: http://www.isdacdsmarketplace.com/about_cds_market/key_cds_facts (accessed on 3 June 2016).

- Jarrow, Robert A. 2011. The economics of credit default swaps. Annual Review of Financial Economics 3: 235–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Kristin N. 2011. Things Fall Apart: Regulating the Credit Default Swap Commons. University of Colorado Law Review 82: 167. [Google Scholar]

- Juurikkala, Oskari. 2012. Credit default swaps and the eu short selling regulation: A critical analysis. European Company and Financial Law Review 9: 307–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keys, Benjamin J., Tanmoy Mukherjee, Amit Seru, and Vikrant Vig. 2010. Did Securitization Lead to Lax Screening? Evidence from Subprime Loans. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 125: 307–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesel, Florian, Felix Lücke, and Dirk Schiereck. 2015. Regulation of uncovered sovereign credit default swaps–evidence from the European Union. The Journal of Risk Finance 16: 425–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jae B., Pervin Shroff, Dushyantkumar Vyas, and Regina Wittenberg-Moerman. 2018. Credit default swaps and managers’ voluntary disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research 56: 953–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolsen, Helmut Max. 1968. The Economics and Control of Road-Rail Competition: A Critical Study of Theory and Practice in the United States of America, Great Britain, and Australia. Sydney: Sydney University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Legg, Michael, and Jason Harris. 2009. How the American dream became a global nightmare: An analysis of the causes of the global financial crisis. The University of New South Wales Law Journal 32: 350. [Google Scholar]

- Little, Ian Malcolm David. 2002. Ethics, Economics, and Politics: Principles of Public Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McIlroy, David. 2010. The regulatory issues raised by credit default swaps. Journal of Banking Regulation 11: 303–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, Atif, and Amir Sufi. 2009. The consequences of mortgage credit expansion: Evidence from the US mortgage default crisis. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124: 1449–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosinsky, B., and Aaron Kirchfeld. 2010. Naked swaps crackdown in Europe rings hollow without Washington. Bloomberg.com, March 11. [Google Scholar]

- Partnoy, Frank, and David A. Skeel, Jr. 2006. The promise and perils of credit derivatives. University of Cincinnati Law Review 75: 119. [Google Scholar]

- Peicuti, Cristina. 2013. Securitization and the subprime mortgage crisis. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 35: 443–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, Eric A., and E. Glen Weyl. 2012. An FDA for financial innovation: Applying the insurable interest doctrine to twenty-first-century financial markets. Northwestern University Law Review 107: 1307. [Google Scholar]

- Posner, Richard A. 2014. Economic Analysis of Law. Boston: Aspen Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Purnanandam, Amiyatosh. 2011. Originate-to-distribute model and the subprime mortgage crisis. The Review of Financial Studies 24: 1881–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quah, Euston, and Edward Joshua Mishan. 2007. Cost-Benefit Analysis. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rajapakse, Pelma, and Shanuka Senarath. 2019. Assessment of Current Regulation and Practice of RMBS Programmes. In Commercial Law Aspects of Residential Mortgage Securitisation in Australia. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 215–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Kishan, Kavita Chavali, and Mohan Gopinath. 2012. Credit Default Swaps: Risk Management. SCMS Journal of Indian Management 9: 102. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, David. 2011. CDSs: Lubricant or landmine? Risk 24: 68. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, Benjamin B. 2010. Should Credit Default Swap Issuers Be Subject to Prudential Regulation? Journal of Corporate Law Studies 10: 427–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmaltz, Christian, and Periklis Thivaios. 2014. Are Credit Default Swaps Credit Default Insurances? Journal of Applied Business Research 30: 1819–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Robert F. 2007. Risk Distribution in the Capital Markets: Credit Default Swaps, Insurance and a Theory of Demarcation. Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law 12: 167. [Google Scholar]

- SEC. 2012. Annual Report on Form 10-K For the Year Ended December 31, 2012. New York: American International Group, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Senarath, Shanuka. 2017. Securitisation and the global financial crisis: Can risk retention prevent another crisis? International Journal of Business and Globalisation 18: 153–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senarath, Shanuka, and Richard Copp. 2015. Credit default swaps and the global financial crisis: Reframing credit default swaps as quasi-insurance. Global Economy and Finance Journal 8: 135–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadab, Houman B. 2009. Guilty by Association-Regulating Credit Default Swaps. Entrepreneurial Business Law Journal 4: 407. [Google Scholar]

- Shadab, Houman B. 2010. Regulating credit default swaps. In Lessons from the Financial Crisis: Causes, Consequences, and Our Economic Future. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 633–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Shalendra D. 2013. Credit default swaps: Risk hedge or financial weapon of mass destruction? Economic Affairs 33: 303–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavell, Steven. 1979. On moral hazard and insurance. In Foundations of Insurance Economics. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 280–301. [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrom, William K. 2009. Washington and Lee Law Review. The AIG Bailout 66: 493–991. [Google Scholar]

- Stulz, René M. 2010. Credit default swaps and the credit crisis. Journal of Economic Perspectives 24: 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrahmanyam, Marti G., Dragon Yongjun Tang, and Sarah Qian Wang. 2014. Does the tail wag the dog?: The effect of credit default swaps on credit risk. The Review of Financial Studies 27: 2927–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, Peter L. 2009. The political economy of the subprime crisis: Why subprime was so attractive to its creators. European Journal of Political Economy 25: 124–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, Trevor. 2010. Six Months of Panic: How the Global Financial Crisis Hit Australia. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Terry, Linnea McCord, and Peggy J. Crawford. 2010. Credit default swaps: The good, the bad and the ugly. Journal of Business & Economics Research 8: 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).