Abstract

This paper assesses the relationship between corporate governance practices and the performance of pension funds in Ghana, which is an emerging market. Data for this study came from two sources: surveys of pension fund managers and annual financial reports of pension funds. Data analysis techniques include mean score ranking and panel regression. The results showed that corporate governance practices such as upholding the rights of shareholders to know the capital structure of the pension funds, equitable treatment of all shareholders, effective internal controls, and timely supervisory functions of audit committees influence the performance of pensions funds. In addition, ensuring proper board composition, the ethnic and gender diversity of board members affect the success of pension funds in the country. The study indicates that the current challenges facing pension funds in the country include poor investment decisions and market volatilities in the investment market. This study provides insight into the governance practices of pension funds. It is relevant for policies and corporate practices to be strengthened to enhance the performance of the firms.

1. Introduction

Sound corporate governance is a great concern of every stakeholder (Claessens and Yurtoglu 2013; Cocco and Volpin 2007; Phan and Hegde 2012) Good corporate governance practices contribute to corporate success, maximise shareholder wealth, promote a positive corporate image, and maintain investors’ confidence (Abor 2007). Abor and Adjasi (2007) indicated that the primary role of good corporate governance is its focus on the supervision and accountability of managers of a firm. In addition, good corporate governance serves as a tool to mitigate corrupt practices and encourage adherence to ethical codes (Arjoon 2017; Darko et al. 2016; Kowalewski 2016; Sami et al. 2011; Soana 2011). Additionally, Adams and Mehran (2012) found that effective corporate governance mechanisms in a company reduce operational costs and increase a firm’s profitability. Furthermore, studies on corporate governance have shown that board composition (i.e., age, experience, gender), Chief Executive Officer (CEO) or chairman split, non-executive directors, and audit committees are critical indicators to boost a firm’s performance (Abor 2007; Alves and Mendes 2004; Denis 2001; Giannarakis 2014). On the other hand, poor corporate governance entrenches poor mishandling of earnings, resulting in bad corporate image and financial capital. For its importance, Škare and Hasić (2016) assert that corporate governance ensures a better relationship among of all stakeholders.

Empirical evidence reveal that corporate governance and firm performance are inconclusive, and these studies have shown mixed results (Alabdullah 2018; Buallay et al. 2017). From a positive perspective, studies found corporate governance characteristics to significantly impact the performance of firms (Ahmed and Hamdan 2015; Gupta and Sharma 2022). A research study by Buallay et al. (2017) in Saudi Arabia using 171 listed firms demonstrated that more robust corporate governance systems of a firm significantly improve its performance. However, other studies found little or no impact of corporate governance on the performance of firms (Aldamen et al. 2011; Black et al. 2006). Studies are skewed against the pension fund sector in comparative with much research geared toward other sectors such as banks, manufacturing, etc. in developed economies (Buallay et al. 2017). In emerging economies such as Ghana, few studies exist on the role good corporate governance plays in the performance of pension funds (Abor and Adjasi 2007; Anku-Tsede 2019).

A review of the literature revealed that the relationship between corporate governance practices and the management of pension funds is not clear in research outlets in Ghana (Dorfman 2015; Mpinga and Westerman 2017). As in other emerging economies (Dorfman 2015; Mpinga and Westerman 2017; Phan and Hegde 2012), the pension industry in Ghana is still evolving due to the limited income of the labour force, which is not interested in setting aside funds to cater for pensions (Stewart and Yermo 2009). Numerous factors have been identified as accounting for this phenomenon, which include including an aging population, income disparities, mismanagement of pension funds, political interference, and low investment returns (Anku-Tsede 2019). A national pension reform was kick-started from 2004 to 2009, and the outcomes of the reforms was the Pension Act 766 in 2010 that received an amendment in 2014, Act 883 (Donkor-Hyiaman et al. 2019). Ghana’s pension scheme is a three-tier pension scheme. The government manages the first tier and second tier through Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) and approved pension fund managers(Ashirifi et al. 2021; Kpessa-Whyte and Tsekpo 2020). The third tier is a voluntary scheme managed personally or the selected pension fund manager of the pensioner (Kpessa-Whyte 2011). From a modest sum of GH¢805.1 million in 2012, tier two and three pension fund contributions in Ghana managed by private schemes rose to GH¢2.6 billion in 2014 before closing in 2015 at GH¢6.8 billion (NPRA 2015).

Additional data from the National Pensions Regulatory Authority (NPRA) showed that GH¢8.3 billion was recorded in 2017 with GH¢2.7 billion contributions from funds managed by pension funds, and the amount has doubled as of 2021. However, studies and institutional reports have not established the contribution of corporate governance to this growth. Notably, the sustainability of pension funds in Ghana appears to be fragile due to the changing global events and occurrences such as COVID-19 that put returns on pension funds at risk (Kpessa-Whyte 2011). Therefore, this study’s aim is to assess the relationships between corporate governance practices and the performance of pension funds in Ghana. The specific objectives include: (1) to determine the dominant corporate governance practices of pension funds in Ghana, (2) to examine the impacts of corporate governance on the performance of pension funds in Ghana, and (3) to establish the challenges associated with corporate governance practices of pension funds in Ghana. The study’s contribution is mainly twofold: First, it highlights the key contribution of corporate governance practices of pension funds in an emerging economy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of corporate governance practices on pension funds’ performance in Ghana. In addition, the study complements existing literature on corporate governance by providing specific practices that enhance the performance of firms. Our study specifically indicates that the board composition and frequency of board meetings ensures relevant management decisions are made to strengthen the firm’s performance and ensure a better stakeholder relationship. These practices provide understanding of the role of sound corporate governance in the performance of pension funds. Secondly, the findings of this research are relevant to fund managers in knowing the key corporate governance practices for pension funds’ performance. Importantly, this research will inform the formulation of new policies and the revision of existing practices of pension funds to achieve better corporate outcomes. The remaining sections of the study include a literature review, methodology, results, and conclusions of the study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evolution of Pension Funds in Ghana

Pensions in Ghana started as far back as the colonial era to cater for those who worked in the colonial administration and mine workers (Kpessa-Whyte 2011). It was a non-contributory scheme that was exclusive and available to only urban dwellers, mostly the Europeans and a few Africans, to reward and encourage loyalty. In 1950, the first pension scheme, the Pension Ordinance No. 42 (Cap 30) and Superannuation schemes were introduced to cater for the retirement benefit of Ghanaian public workers, such as teachers, university lecturers, doctors, and nurses; however, a clear majority of Ghanaians were unable to benefit from this scheme (Ashidam 2011). The Social Security Act (No. 279) was passed in 1965 to cover all private and public-sector workers who were not covered under the previous scheme. It was a provident fund, providing benefits for old age, invalidity and survivor benefit. This scheme was revoked, and the Social Security and National Insurance Act (SSNIT) was established under NRCD 127. In 1991, the Social Security Act was enacted, and the scheme was turned into a defined contribution scheme (Donkor-Hyiaman et al. 2019). However, some workers such as the Armed Forces, Police and Prison Service were exempted from joining the scheme. Ghana operates three pension benefits: Old Age Benefit, Invalidity Benefit, and Death Survivor Payment. To qualify for the old age benefit under the new scheme, a worker must have worked for a minimum of 240 months and be at least 60 years of age, while those in the mines and other extractive industries have a mandatory retirement age of 58. Workers who have been injured at work may qualify for payment under the invalidity benefit section of the social security system (Mensah 2013). If a worker dies before the required retirement age, their benefits are calculated as the present value of all contributions and paid as a lump sum to the surviving spouse or dependents; this is known as the death survivor payment. Funding of the schemes is based on contributions made by the employer and the employee on behalf of the employee. The employer contributes 12.5% of the employee’s salary, while the employee contributes 5% of their salary, totalling 17.5%. These contributions are invested, and when the employee reaches retirement age, becomes permanently incapacitated or dies before retirement, the total contributions and returns on the investment are paid as a lump sum to the employee or their dependents (Kpessa-Whyte 2011).

Over the years, concerns have been raised about SSNIT not paying enough benefits to retirees and failing to include informal sector workers, who constitute about 80% of the workforce in the scheme; this led to a reform in July 2004. This led to the drafting and passing of the National Pensions Act 2008 to provide universal pensions to all Ghanaian workers (Kpessa-Whyte 2011). The Act is divided into four parts; the first discusses having a regulatory body. The second part deals with the provision of the schemes, the third part deals with the management of the schemes, and finally, the general provisions of the Act are contained in the fourth part. Under the new scheme, 18.5% of a worker’s monthly salary will be paid towards their pension, which is distributed between the first and second tiers. The first two tiers are mandatory, and the third tier is voluntary. The first tier, which makes up 13.5% of an employee’s monthly salary, goes to SSNIT, and it is mandatory for both public and private sector workers. Still, self-employed individuals have the option of joining or not. Out of the 13.5%, 2.5% goes to the NHIS, and 5% of an employee’s monthly salary is allocated to the second tier, which is managed privately by approved pension fund managers. The aim is to give pensioners lump sum benefits compared to what is presently available under the SSNIT. The third tier is a voluntary provident fund and personal pension scheme, which provides tax benefit incentives for workers who opt for this scheme and the first two (Dorfman 2015). It could be managed personally or by approved pension fund managers. The previous pension schemes in Ghana were relatively exclusive and did not cover 80% of Ghana’s working population. The introduction of the Authority and the third tier is an effort to address the issues concerning the old pensions system, which by design excluded those in the informal sector and did not provide avenues for the citizenry to arrange their pensions in addition to the state pension. In this case, pension fund managers (firms) oversee the pensions of citizens who want to attain better pension outcomes during retirement. All pension fund managers in Ghana are required registered to register individually as limited liability firms under the Companies Act, 2019 and seek additional certifications of operation from National Pensions Regulatory Authority (NPRA 2022). There are no limitations on the forms on registrations, but it must be prescribed by the NPRA and the Companies Act, 2019 (Kpessa-Whyte and Tsekpo 2020). There are no legal restrictions on where investments can be made, as far as it is a legitimate investment venture (Kpessa-Whyte 2011).

2.2. Corporate Governance of Pension Funds

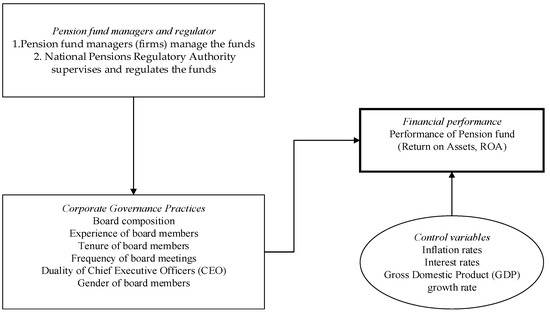

Corporate governance has been explained as a mechanism by which operational managers of entities are made to act in the interest of the owners of the entities and other stakeholders (Aboagye and Otieku 2010). The authors alluded that the organisations with good corporate governance structures report better performance, implying that when managers take keen interest in putting the right structures in place, the firm performs well. The OECD (2004) also explains corporate governance as “a set of relationships between a company’s management, its board, its shareholders, and other stakeholders. Corporate governance provides the structure through which the company’s objectives are set, and the means of attaining those objectives and monitoring performance are determined” (Alda 2021). Corporate governance includes relations between owners and top management, and these relations make it possible for agents to be accountable to shareholders (Kowalewski 2016). Corporate governance concerns rules and regulations that organisations apply and follow to achieve visions and missions translated into stated objectives for boards of directors and managers of resources. Sound corporate governance encourages the efficient use of resources and accountability for managers’ stewardship of those resources (Ioannou and Serafeim 2012). Institutions that practice good corporate governance are more likely to achieve institutional objectives and goals (Agyemang and Castellini 2015). Kumari and Pattanayak (2017) recommended that shareholders tie the remuneration of board members to their performance and that organisations develop an annual mechanism to check management cum board activities. Kowalewski (2016) advocates the need for a firm (well-informed) board to drive an organisation’s vision with a good sense of judgment in management and performance. Researchers have professed the need for strong corporate governance mechanisms in all aspects of an institution’s life to ensure the diligence and integrity of these entities’ operations. Good corporate governance is now a prime concern to owners and other stakeholders of institutions. These concerns extend to the general welfare of society. Good stewardship and sustained accountability are expected from firms by society. In pension fund management settings, two sets of factors affect corporate entity’s effectiveness. The first is the internal corporate governance factors relating to pension fund management. This involves effective interactions between internal systems relating to pension funds. The second factor is the external corporate governance factors concerning the regulatory and legal framework under which the pension funds operate. The first node in Figure 1 exhibits the managers of pension funds with the regulators from the National Pensions and Regulatory Authority (NPRA), which is a body that supervises pension fund management in Ghana. The National Pension Act 2008 (Act 766) established the National Pensions Regulatory Authority (NPRA) as the sole supervisor (regulator) of pension fund activities in Ghana (Donkor-Hyiaman et al. 2019). The NPRA monitors the operations of all pensions in the country by demanding regular reports from the pension fund managers (Anku-Tsede 2019). The regulatory body also updates the pension managers of new regulatory requirements. It oversees the registration and dissolution of pension fund managers (firms) by invoking various legal codes of the country. The NPRA trains fund managers and monitors the progress of pension funds by reviewing annual reports. The NPRA assigns supervisors to each of the pension funds, and internally, there is a specific manager within the pension fund firms to meet the requirements of the NPRA (NPRA 2022).

Figure 1.

Corporate governance and pension funds.

The second node represents the components of corporate governance practices on pension funds. The third node shows macroeconomic variables that reduce the biases in the observed variables of corporate governance practices towards the performance of pension funds. These three nodes relate to pension funds’ finance performance, which is represented by the return on assets in the fourth node.

2.3. Theories and Hypothesis Development

Scholars have discussed the concept of corporate governance and ownership of assets in various stages of human development. Goldsmith (1995) referenced Adam Smith, 1776, who argues that most wealth managers cannot be expected to watch over it with the same zeal as the owners. This breeds the concept of conflict of interest amongst owners and managers of their firms. It brings in agency theory. Agency theory postulates that an agent or agency (board of directors) is hired by one or more person(s), called the principal(s) (shareholders), under a contract and is compensated by the principal to achieve desired outcomes for the principal (Ellis and Johnson 1993; Fama 1980). Owners of institutions give away decision-making rights to agents, hoping that the agents will act in their best interest and respect the fiduciary duty that promotes utmost good faith (Eisenhardt 1989). Arrow (1985) designed two models of asymmetrical information, explaining agency theory through the hidden action model and the hidden information model. In the hidden action model, the principal does not observe the agent’s actions but only observes the outcome of the actions. The hidden information model shows a principal who observes the agent’s actions but does not know the vital information needed to perform those actions (Buallay et al. 2017). Information asymmetry arises when the principal does not have all the information when analysing the agent’s performance. Adverse selection occurs when the principal selects the wrong agent for the task ahead. In addition, agents can underperform on their promises to obtain maximum compensation; this is a moral hazard (Darko et al. 2016; Ellis and Johnson 1993; Fama and Jensen 1983). The moral hazard is higher when the agent has the more specialised knowledge to perform a task but fails. Thus, it may be impossible for the principal to ensure that the agent always acts in their best interests. However, there are three ways in which this challenge can be minimised, namely:

- Board independence (to supervise management).

- Market for corporate control (mischievous managers are controlled by an active merger and acquisition market programme).

- Agent equity ownership—ensuring that agents are part owners of the organisation they manage.

The above-listed methods come at a cost to the principal (Hill and Jones 1992; Jensen and Meckling 1976). Some sources of agency cost are recruitment, adverse selection, specifying principal preferences, establishing incentives, moral hazard, stealing, side deals, monitoring and policing, bonding and insurance (Sami et al. 2011; Shapiro 2005). Sometimes, the costs incurred in regulating and controlling agents may not be worth the benefits of improved agent behaviour (Mitnick 2015; Wiersema and Bantel 1992). Studies have criticised the agency theory, saying it has been overly simple with its assumptions and does not reflect real-world activities. The usage of agency theory in academia has received its criticisms. For instance, Kato et al. (2017) argued that agency problems are not immune to only one firm but many firms. Vafeas and Vlittis (2016) have claimed that agency theory does not address any apparent organisational problems that cannot be generalised. Agents acting on their parochial interest can derail firm profitability, leading to shareholder losses.

Another theory that supports corporate governance and pension funds is the stakeholder theory. The theory assumes organisational management within a firm comes with multiple constituents made up of owners, employees, suppliers, local communities, creditors and other stakeholders (Donkor-Hyiaman et al. 2019; Jackson 2005; Korac-Kakabadse et al. 2001). Jones and Wicks (1999) argued that stakeholder theory suggests that the extent to which managers attend to stakeholder interests largely depends upon the managers’ values and moral guidelines. Good morals and values translate to their behaviour. Bonnafous-Boucher (2005) suggested that the demographic characteristics of top managers and stakeholders lead to firms’ different strategic decisions. Therefore, top management characteristics do have an impact on the firm performance. Inferring from Aguilera and Crespi-Cladera’s (2016) study, it could be hypothesised that limited studies on board characteristics such as board composition could be limited. It is important to understand the impact of board composition on firm performance. A firm’s board of directors is usually based on institutional requirements of both host and home countries (Morgan and Kristensen 2006). Hypothetically, corporate governance and the performance of pension funds have been framed as follows:

H1:

Board composition positively affects pension fund performance.

H2:

The experience of the board members positively influences pension fund performance.

H3:

Frequency of board meetings positively influences pension fund performance.

H4:

Tenure of the board members positively influences pension fund performance.

Concerning studies on performance, corporate governance structures have significantly impacted the firm’s performance (Soana 2011; Jo et al. 2014). A significant component of corporate governance is the board of directors, of which the CEO is a member. An element of corporate board structure is the separation of the board chairman from the firm’s CEO in terms of roles. CEO duality suggests that the board chairman also acts as the CEO (Samaha et al. 2012). This will lead to a conflict of interests. Lattemann et al. (2009) argue that to deal with CEO duality, there should be clear policy and practical measures to separate their roles, leading to higher levels of corporate transparency and performance. In contrast, authors such as Giannarakis (2014), Phan and Hegde (2012) have posited that CEO duality affects disclosures and organisational practices, negatively affecting the firm’s performance. It was hypothesised as the following:

H5:

CEO duality is negatively associated with pension fund performance.

A review of studies also suggests that the gender composition of the board has been usually associated with the firm’s financial performance (Sami et al. 2011). Vafeas and Vlittis (2019) mentioned that independent female directors, compared to their male counterparts, might take organisational practice issues seriously due to their stronger moral orientations and reputational reasons. Rupp et al. (2006) argued that an increasing number of women on the boards would have positive impacts on the firm’s performance. Thus:

H6:

Diversity of the board is positively associated with pension fund performance

3. Methods

3.1. Data

The study utilised a mixed data from primary and secondary sources for this research. The primary source of data came from survey questionnaires (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie 2004). The questionnaire was designed to address two research objectives (RO) 1 and 3 (refer to Section 1). RO1 aims to identify the dominant corporate governance practices of pension funds in Ghana, and RO2 aims to determine the challenges associated with corporate governance practices of pension funds in Ghana. The questionnaire survey had three key components. The first component was the profile of the respondents: work experience and job title. The second and third components of the survey questionnaire captured the dominant corporate governance practices and challenges of pension funds in Ghana, respectively. The questionnaire was reviewed by five (5) experts with academic and industry experiences spanning three decades. In addition, pre-testing through a pilot survey involving 12 managers of the pension funds was conducted. It also contained sections on demographics of respondents, and challenges associated with corporate governance of pension funds. A 5-point Likert scale, 1 for strongly disagree, 2 for disagree, 3 for neutral, 4 for agree and 5 for strongly agree, was used to measure statements on corporate governance practices and challenges associated with it. As a successful and popular measuring scale of respondents’ responses in the literature, a five-point Likert scale ascertains a common objective numerical score of diverse opinions of participants (Akomea-Frimpong et al. 2021a; Ho 2005). The information gathered from the pilot survey and the experts were used to review the questionnaires before they were distributed to the respondents.

The respondents targeted for the survey were pension managers of registered pension funds in Ghana. According to the National Pensions Regulatory Authority, there were thirty-nine pension managers (firms) in good standing in the country as of 2021 (NPRA 2022). Each pension fund has numerous managers overseeing investment portfolios and other functions areas. The targeted respondents were three hundred and ninety (390), representing ten (10) respondents from each of the thirty-nine pension managers. One hundred and ninety-eight (198) surveys were filled and returned, representing 50.7% of the response rate. After screening the 198 responses, 13 were found to be incomplete, and they were taken out, reducing the tally to 185 responses for the data analysis.

Secondary data were from the thirty-nine annual financial reports of the pension funds in Ghana. Additional data on board structure, board meetings, gender composition of the board, the duality of chairman and the years of experience of board members were obtained from the pension fund managers. Data on the control variables of inflation, interest rates and gross domestic products were obtained from the Bank of Ghana 2013 to 2021. The timeline for the data starts from 2013 because the pension managers were fully allowed to operate after the Pension Act in Ghana was promulgated in 2010. We also used GDP growth rate, interest rate and inflation derived from the World Bank and Bank of Ghana.

3.2. Definition and Measurement of the Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable for this study is firm performance. The literature suggests that the firm’s performance determines the survival of the firm. Therefore, it is important to assess the performance of these pension firms to determine whether they have the strength to move forward. Previous studies have measured profitability in return on assets (Abor 2007). Return on asset (ROA) is the profit before interest and taxes as the ratio of the total assets.

3.2.2. Independent Variables

Board diversity has been established as a strong determinant in corporate governance studies (Liao et al. 2014). Due to its relevance, this study also examined that against firm performance. It was measured based on prior studies as a ratio of female directors on the board. Board independence has been used in prior studies to determine whether the presence of independent directors would impact firm decision making or performance. We rely on the definition of Khan et al. (2013) as directors appointed without direct financial interest or any third party dealing with the firm. Independent directors provide some level of assurance in terms of monitoring firm-wide decisions. We followed prior studies to measure board independence as a ratio of independent directors to the total board size for this study. CEO duality is also another important variable in corporate governance. Prior studies have shown that it usually affects board-level decisions. This is because of the combination of the two portfolios, which often creates personalised decisions. Almost all see it as negative to firm performance (Samaha et al. 2012). Therefore, we used a dummy variable to measure where 1 represents firms with combined roles and 0 otherwise. The frequency of board meetings was measured as the number of times the board held a meeting during the year (Alodat et al. 2021). This is because meeting frequently strengthens the board’s monitoring activities.

3.2.3. Control Variables

Previous studies have identified some firm-level variables that impact corporate governance. We identified firm size, which is measured as a natural log of total assets, firm age measured as the natural log of the number of years of operations and leverage measured as the ratio of the book value of total debts and total assets (Table 1) (Khan et al. 2013).

Table 1.

Definition and measurement of variables of the panel regression model.

3.3. Method of Data Analysis

A statistical (Table 2) with descriptive analysis assisted in discussing the demographics of the respondents (Berthelot et al. 2010; Cheung et al. 2007; Cong and Freedman 2011). To assess the impacts of corporate governance on pension funds, a panel regression model to achieve this is framed as:

where: = Return on Assets; = Intercept; to = Co-efficient of the predictors; = Board composition/size of a pension fund at a point in time; = Experience of the board members in the pension industry at a point in time; = Frequency of board meetings of a pension fund at a point time; = Gender of the board members of the pension fund at a point in time; = Duality of the head of the board of a pension fund at a point in time; = Tenure of the board members of a pension fund at a point in time; = Inflation of Ghana at a point in time; = Interest rate of Ghana at a point in time; = Gross Domestic Product growth rate of Ghana at a point in time and = Error term.

Table 2.

Corporate governance practices of pension funds.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Demographics from the Survey Questionnaire

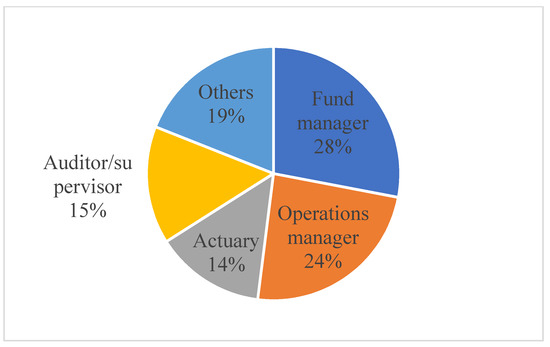

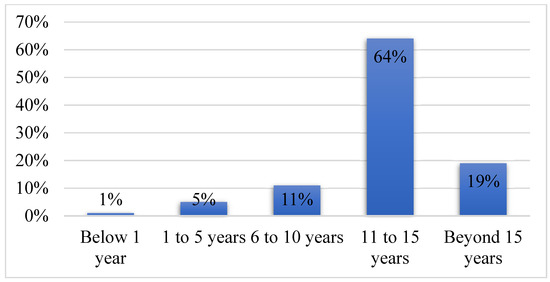

In Table 2, it could be seen that 27% of the 185 respondents are fund analysts or advisors to the pension funds. They assess and suggest that the amount the pensioners should deposit into their pension funds and, together with pension actuaries (that is, 20% of the respondents), provide in-depth knowledge of capital market analysis based on rigorous costs and benefits analysis of the investment outcomes or returns. They feed clients regularly on the suitability of the pension funds and the yields attached and whether an investment should be allowed to suffice or bring it to an abrupt end. These managers mount continuous and effective checks on the funds. The fund managers, who represented 28% of the respondents, work with all the other respondents. They check the clients’ backgrounds to ensure they have no money laundering records that will tarnish the fund’s image. They detect and report fraudulent transactions to appropriate authorities and the auditors/supervisors (17% of the respondents are auditors and accountants in Figure 2). The managers oversee supervising and correcting the wrongs in the corporate governance practices of pension fund management in Ghana. Other respondents (19% of the respondents) included administrators, statisticians, and lawyers connected to the pension funds administration. According to Vafeas and Vlittis (2016), an employee’s experience affects their sense of judgement and job performance. Figure 3 shows that 1% of the respondents have worked for less than a year, 5% of the respondents have working experience between 1 and 5 years, whilst 11% have worked between 6 and 10 years. Sixty-four percent of the respondents have worked with pension fund managers between 11 and 15 years, while 19% of the respondents have beyond 15 years of experience in the pension industry. This shows that most of the respondents, which constitutes 64% of the respondents, have enough experience in the activities in the pension industry as presented in Figure 3. These managers have adequate knowledge and understanding of the pension funds’ corporate governance practices.

Figure 2.

Job titles of the respondents.

Figure 3.

Work experience in the pension fund industry.

4.2. Dominant Corporate Governance Practices of Pension Funds

In Table 2, the mean score column explains the respondents’ feelings on the average of each of the statements in the first column. These feelings or opinions of respondents were ranked in the following column to determine the level of importance of the corporate governance practice to pension funds. Statements with a mean score of 2.5 average thresholds were included in Table 2. Out of the 13 statements in Table 3, the five highly ranked are the following. The rights of shareholders to know the capital structure of the pension funds were ranked the highest, with a mean score of 4.93. Shareholders prefer to know the financial viability of the pension funds before they invest in them. This phenomenon has been driven by the recent collapse of financial institutions in Ghana. Regular reporting on pension funds’ finances and other activities to shareholders was ranked second with a mean score of 4.92. Equitable treatment of shareholders placed third with a mean score of 4.91. Strong, effective internal systems of the pension funds ranked fourth with a mean score of 4.88. The supervisory role played by the board through the audit committees to make sure the internal systems are functioning effectively was ranked fifth with a mean score of 4.59. As a middle-income country, corporate governance is relevant in Ghana’s pension fund management industry. In this study, the pension fund managers in Ghana uphold shareholders’ interests and rights. The keyword in this definition has to do with the organisation’s interest and accountability through its governance structure. This definition also emphasised the need to work in the interest of the owners of the pension fund managers. Aguilera and Crespi-Cladera (2016) alluded that those organisations with good corporate governance structures produce a good performance, implying that performance would improve when managers decide in the shareholder’s interest and the firm itself. These may not necessarily be accurate, since the interest of shareholders is subjective. Shareholders are given the necessary information on the pension fund’s performance on a timely basis. Other findings from Table 3 indicated that shareholders have the right to attend Annual General Meetings (AGMs) and discuss important issues which affect the growth and the sustainability of the pension fund managers. They discuss financial statements and reports from the external auditors on their annual performance. It was also found that the pension fund managers alert shareholders of the need to make changes to their capital structure. Means (2017) has posited that capital structure plays a vital role in the performance of organisations and the management of private properties and funds. Shareholders are treated well irrespective of their share class, and their views can be expressed during AGMs. Fund managers are required to ensure transparency in all transactions and reports. The board of directors has the prime responsibility to oversee the success of the pension fund managers by making strategic decisions that will help the pension fund managers to survive for many years. Mpinga and Westerman (2017) support this position by proposing that a strong (well-informed) board is needed to drive an organisation’s vision with a good sense of judgment in management and performance. McCahery et al. (2016) recommended in their study that shareholders must tie the remuneration of board members to their performance. It seems this is precisely what pension funds in Ghana are practising.

Table 3.

Summary Statistics.

4.3. Relationship between Corporate Governance and Pension Funds

The descriptive statistics outcomes of annual data from 2013 to 2018 in Table 3 showed that the mean value of return on asset is 0.71. This could be explained by the impacts of macroeconomic indicators on the profitability of pension funds. Many pension funds recorded losses during this period. Financial distress coupled with turbulent power outages affected all businesses in Ghana, and the pension funds were of no exemption from late 2012 to early 2016 (Van Gyampo et al. 2017). In 2016, the pension funds started recovering from these losses. The standard deviation is shown in Table 4 (standard deviation = 0.133), which indicates 133% volatility of the earnings of the pension industry with a minimum of 0.23 return on assets and a maximum of 0.95. The mean value of BS is positive during the period. There was an increase in the board size with a maximum of 18 members on the board of pension funds and a minimum of three members. The mean value of BE (board members’ experience in the pension industry) and TB (tenure of the board members) are 8 and 4 years, respectively. The mean frequency of board meetings (FBM) of pension funds in Ghana is 12, with a minimum of six meetings and a maximum of 24 meetings. The number of women on the board (GEN) posted a mean of two for the period in this analysis. The mean value of DLT (duality of the board chairmanship position) of 0.52 was posted, with a minimum of 0 but a maximum of 1 for the entire period. The control variable of GDP growth rate indicates a positive and increased value in the means and their impact on the performance of the pension funds. The inflation rate and the interest, which are also control variables, indicate a negative influence on ROA.

Table 4.

Correlation Matrix.

In this section, the results of key diagnostic tests are presented here. These tests are significant because they tell whether assumptions underlining the panel regression estimation were valid and reliable. In this regard, key diagnostic tests were performed after running the data to check the robustness of the panel model. Heteroscedasticity was checked, and evidence of heteroscedasticity was found using the Breusch Pagan test for heteroscedasticity. The null hypothesis was set as a constant variance. The result showed a chi-square, chi2(1) = 586.13 and Prob. > chi2 = 0.00. Hence, the panel model is unbiased, consistent, reliable and efficient for analysing the issue at hand. No evidence of autocorrelation was found during the robust test with the Wooldridge test for autocorrelation. The null hypothesis was set as no first-order autocorrelation. The results showed an F-statistic of 0.016 and Prob. > F = 0.7432. Multicollinearity was also assessed between the variables. A correlation coefficient higher than 0.7 indicates a strong correlation, according to Chong and Jun (2005) and Kennedy (2008), and vice versa (see Table 4). Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 presents the results from the panel regression model. The Hausman test was used to test and choose between the fixed effect and random effect of the panel regression model (Hausman 1978). This test has been used widely in academic literature to choose the two effects of the panel regression model. Hausman’s test posted a Chi-square (chi2) of 25.83 with a p-value of 0.00, showing that the null hypothesis (Ho: the random effect is acceptable for this study) is rejected. This means the fixed effect is preferred to the random effect. The fixed effect in Table 5 shows that the board composition, experience of board members, frequency of board meetings, gender and gross domestic product significantly affect the performance of pension funds. These determinants have significant p-values less than the significance level of 5%. A unit change in any of these significant variables will cause a 0.28, 0.75, 0.36, 0.80 and 0.98 change in the performance of pension funds, respectively. The influence of all the independent variables (corporate governance and control variables) on the dependent variable, the performance of pension funds, is 58.2 (R-squared, R2). The fixed effect model is appropriate because the F-statistic has a value of 0.00% at a significance level higher than 5%.

Table 5.

Fixed effect panel model.

Table 6.

Random effect panel model.

Table 7.

Hausman Test Results.

4.4. Key Challenges of Corporate Governance Practices of Pension Funds

Gender bias on the board of directors of pension funds remains the most significant setback in the corporate governance practices of the pension funds in Ghana (see Table 8). Male dominance continues, which is a common phenomenon in the Ghanaian corporate environment (Kakabadse et al. 2015). This challenge is followed by political interference through the National Pensions and Regulatory Authority (NPRA) of Ghana’s supervision, which dips the confidence of many pension funds, especially the privately owned pension funds (Anku-Tsede 2019). Furthermore, weak internal systems or controls of pension funds were pointed out to be caused by the incapacitated or limited resources of the pension funds. Fourthly, non-compliance of some of the pension funds to NPRA directives also has negative ramifications on the terms and conditions of their operations (Kpessa-Whyte and Tsekpo 2020). This weakens the supervisory contributions made by the regulator to strengthen the corporate governance practices of pension funds in Ghana. Auditing transactions and activities are less emphasised by pension fund managers (firms). Some pension funds do not even have fully functioning internal audit units and audit committees to supervise their operations (Akomea-Frimpong et al. 2016, 2019, 2021b). Aside from the top five challenges with the corporate governance practices, other challenges include aggressive and unhealthy competition in the pension industry, causing the pension funds to compromise their standards on corporate governance (Jara et al. 2019). In the short term, the lowering of the standards might cause an increase in the market shares of the pension funds, but this will affect them negatively later (Andoh et al. 2018). The weak legal framework could also be blamed for the inefficiencies in the pension fund activities. The lax legal and regulatory framework negatively affects the performance measures of pension funds. In addition, the non-disclosure of key transactions to shareholders adversely affects the performance of pension funds.

Table 8.

Critical challenges of corporate governance of pension funds.

5. Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Our study contributes to the literature on corporate governance and firm performance. We contribute in three ways:

First, studies have shown that corporate governance practices or mechanisms vary across countries given the differences in institutional factors. Our study, therefore, provides a contextualised understanding of the impact of corporate governance on the performance of pension fund. It highlights the key contribution of corporate governance practices of pension funds in an emerging economy such as Ghana. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of corporate governance practices on pension funds’ performance in Ghana.

Second, our study complements existing literature on corporate governance by providing specific practices that enhance the performance of firms. We find that better corporate governance practices in the context of an emerging country measured as board composition and frequency of board meetings ensure relevant management decisions are made to strengthen the firm’s performance and ensure a better stakeholder relationship. These practices provide an understanding of the role of sound corporate governance in the performance of pension funds.

Third, instead of just testing the relationship as prior studies often have, we additionally consider the challenges faced by pension fund managers which can potentially influence the relationship tested. We find that male dominance on corporate boards, weak internal systems or controls, aggressive and unhealthy competition, and political interference through the regulator continues to hamper the corporate governance of practices. This is particularly important given that the pension sector is one of the highly regulated sectors, and fund managers will have to regularly interface with the regulator. Such interactions create an opportunity for the regulator to unduly influence their corporate governance activities.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our study has shown that corporate governance practices strongly improve the performance of firms. In developed economies, corporate governance practices are advanced due to the efficient regulatory environment within which firms operate. In emerging economies, the regulatory environment is weak, which makes it possible and easier for firms and managers to circumvent the system. Our study has shown that for pension funds to be sustainable and competitive, there should be in place some specific corporate governance practices that support stakeholder relationships and enhance firm performance. First, firms should ensure that the make of the board supports dynamism, especially in these modern times where customers keep changing their preferences. The study recommends a diversified board made up of experience members, gender, young members (i.e., Millenials) to meet the changing demands of pension fund users. Second, the study recommends regularly meeting to address emerging concerns of the firms. It is evident that meeting once or twice a year may not help the board to offer significant advice to top management on emerging issues. Practically, meeting once a month is feasible to drive organisational course. Our study clearly show that CEO duality has no influence on the performance of pension funds in Ghana. This implies that the separation of the chairman of the board from the CEO of the firm in terms of roles does not influence the board decision making. Finally, the presence of corporate governance mechanisms in the organisation enables the pension firms to avoid chaos and bankruptcy, regulatory requirements and serve as a basis for monitoring organisational actions.

Pensions firms are encouraged to take lessons from this study to assign more resources to improve its corporate governance practices. It is evident from this study that the pension sector is experiencing financial difficulties partly due to corporate governance flaws(Baidoo and Akoto 2019). To repose the confidence in pensioners, it is appropriate that regulators and managers must institute stringent measures to manage pension funds well to the admiration of their stakeholders. The study recommends that pension fund managers will gain understanding of where to formulate and implement practices that ensure effective corporate governance through the effective training and revision of internal policies. The study is relevant to other industries in Ghana since they work within the same environment with weak regulatory frameworks. Similarly, the study is relevant to other emerging economies with comparable weak regulatory environments to strengthen their corporate governance practices. Research limitations of this paper could be addressed and expanded by future studies to cover the larger sector of the pension fund industry.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

A limited number of managers were contacted for this study with a limited scope on corporate governance. We were constrained in terms of time and data; thus, we were unable to consider industry-wide issues of all stakeholders in the pension industry. There was an inaccessibility of data relating to informal and small-scale pension funds due to poor national database on pension fund activities at the local level of governance in the country. Even at the national level, only the annual financial reports of the fund managers are available, and the additional information used in this paper was sought individually from the pension fund managers. Furthermore, diverse performance measures are available in past studies, but this study relied on return on assets. Future studies can develop and utilise sustainable performance benchmarks inclusive of social and environmental matters on the corporate governance of pension funds.

7. Conclusions

In this study, we investigated corporate governance and the performance of pension funds in Ghana. We examined the corporate governance practices of pension funds, the effects of corporate governance on the performance of pension funds, and the challenges associated with corporate governance about pension funds. The findings show that some of the corporate governance practices of pension funds include shareholders having the right to attend Annual General Meetings (AGMs) and discuss important issues that affect the growth and the sustainability of the pension funds. Shareholders are given the necessary information on the pension fund’s performance on a timely basis. Shareholders are treated well irrespective of their share class, and their views can be expressed during AGMs. The board of directors has the prime responsibility to oversee the success of the pension fund managers by making strategic decisions to help the pension funds survive for many years. The audit committee, remuneration committee, recruitment committee, and other committees supervise the pension funds’ success. Results from our panel data regression analysis with controlling variables from the gross domestic product, inflation and interest rates showed a significant positive effect of corporate governance on the performance of pension funds. Out of the six hypothesised and tested variables, five of them, namely board composition, the experience of board members, frequency of board meetings, and gender, were found to influence the performance of pension funds significantly. The duality of the CEO was found to be insignificant. The gross domestic product growth rate was the only control variable with a significant effect on pension funds’ performance. The challenges associated with corporate governance include gender bias on the board of directors of many pension funds, which remains, with a small percentage on the board of many pension funds in Ghana. Male dominance continues. The poor legal framework could also be blamed for the inefficiencies in the activities of pension funds.

Author Contributions

I.A.-F., E.S.T. and E.J.T. designed the study. I.A.-F., M.A. and E.J.T. conducted data cleaning and analysis, and I.A.-F., E.S.T., M.A. and E.J.T. wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors provided substantial contributions to subsequent drafts. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicate no conflict of interest.

References

- Aboagye, Anthony Q., and James Otieku. 2010. Are Ghanaian MFIs’ performance associated with corporate governance? Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 10: 307–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abor, Joshua. 2007. Corporate governance and financing decisions of Ghanaian listed firms. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 7: 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abor, Joshua, and Charles K. D. Adjasi. 2007. Corporate governance and the small and medium enterprises sector: Theory and implications. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 7: 111–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Renée B., and Hamid Mehran. 2012. Bank board structure and performance: Evidence for large bank holding companies. Journal of Financial Intermediation 21: 243–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, Ruth V., and Rafel Crespi-Cladera. 2016. Global corporate governance: On the relevance of firms’ ownership structure. Journal of World Business 51: 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyemang, Otuo Serebour, and Monia Castellini. 2015. Corporate governance in an emergent economy: A case of Ghana. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 15: 52–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Esra, and Allam Hamdan. 2015. The impact of corporate governance on firm performance: Evidence from Bahrain Bourse. International Management Review 11: 21. [Google Scholar]

- Akomea-Frimpong, Isaac, Charles Andoh, Agnes Akomea-Frimpong, and Yvonne Dwomoh-Okudzeto. 2019. Control of fraud on mobile money services in Ghana: An exploratory study. Journal of Money Laundering Control 22: 300–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, Isaac, Charles Andoh, and Eric Ofosu-Hene. 2016. Causes, effects and deterrence of insurance fraud: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Financial Crime 23: 678–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, Isaac, Xiaohua Jin, and Osei-Kyei Robert. 2021a. Developing a financial risk maturity model for public-private partnership projects. Paper presented at the 37th Annual Conference of ARCOM, Online, September 6–7; pp. 412–21. [Google Scholar]

- Akomea-Frimpong, Isaac, Xiaohua Jin, and Robert Osei-Kyei. 2021b. Managing financial risks to improve financial success of public—private partnership projects: A theoretical framework. Journal of Facilities Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdullah, Tariq Tawfeeq Yousif. 2018. The relationship between ownership structure and firm financial performance: Evidence from Jordan. Benchmarking: An International Journal 25: 319–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alda, Mercedes. 2021. The environmental, social, and governance (ESG) dimension of firms in which social responsible investment (SRI) and conventional pension funds invest: The mainstream SRI and the ESG inclusion. Journal of Cleaner Production 298: 126812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldamen, Husam, Keith Duncan, Simone Kelly, Ray McNamara, and Stephan Nagel. 2011. Audit committee characteristics and firm performance during the global financial crisis. Accounting & Finance 52: 971–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Alodat, Ahmad Yuosef, Zalailah Salleh, Hafiza Aishah Hashim, and Farizah Sulong. 2021. Corporate governance and firm performance: Empirical evidence from Jordan. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, Carlos, and Victor Mendes. 2004. Corporate Governance Policy and Company Performance: The Portuguese case. Corporate Governance: An International Review 12: 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andoh, Charles, Daniel Quaye, and Isaac Akomea-Frimpong. 2018. Impact of fraud on Ghanaian SMEs and coping mechanisms. Journal of Financial Crime 25: 400–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anku-Tsede, Olivia. 2019. Inclusion of the Informal Sector Pension: The New Pensions Act. Paper presented at the International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, Washington, DC, USA, July 24–28; pp. 491–502. [Google Scholar]

- Arjoon, Surendra. 2017. Virtues, compliance, and integrity: A corporate governance perspective. In Handbook of Virtue Ethics in Business and Management. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 995–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow, Kenneth J. 1985. Informational structure of the firm. The American Economic Review 75: 303–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ashidam, Benedict Nii Amarteifio. 2011. The Problem of the Cap 30 Pension Scheme in Ghana. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Problem-of-the-Cap-30-Pension-Scheme-in-Ghana-Ashidam/a8e24409dffa287ffe855dea8c2ce7a802dfecef#paper-header (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Ashirifi, Gifty D., Grace Karikari, and Margaret E. Adamek. 2021. Prioritizing the National Aging Policy in Ghana: Critical Next Steps. Journal of Aging & Social Policy 34: 127–44. [Google Scholar]

- Baidoo, Samuel Tawiah, and Linda Akoto. 2019. Does trust in financial institutions drive formal saving? Empirical evidence from Ghana. International Social Science Journal 69: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelot, Sylvie, Tania Morris, and Cameron Morrill. 2010. Corporate governance rating and financial performance: A Canadian study. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 10: 635–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, Padmanabha Ramachandra, and R. Rathish Bhatt. 2017. Corporate governance and firm performance in Malaysia. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 17: 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Bernard S., Inessa Love, and Andrei Rachinsky. 2006. Corporate governance indices and firms’ market values: Time series evidence from Russia. Emerging Markets Review 7: 361–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnafous-Boucher, Maria. 2005. Some philosophical issues in corporate governance: The role of property in stakeholder theory. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 5: 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, Amina, Allam Hamdan, and Qasim Zureigat. 2017. Corporate governance and firm performance: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal 11: 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carter, David A., Betty J. Simkins, and W. Gary Simpson. 2003. Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financial Review 38: 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Yan-Leung, J. Thomas Connelly, Piman Limpaphayom, and Lynda Zhou. 2007. Do investors really value corporate governance? Evidence from the Hong Kong market. Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting 18: 86–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Il-Gyo, and Chi-Hyuck Jun. 2005. Performance of some variable selection methods when multicollinearity is present. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 78: 103–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, Stijn, and B. Burcin Yurtoglu. 2013. Corporate governance in emerging markets: A survey. Emerging Markets Review 15: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocco, João F., and Paolo F. Volpin. 2007. Corporate Governance of Pension Plans: The U.K. Evidence. Financial Analysts Journal 63: 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Yu, and Martin Freedman. 2011. Corporate governance and environmental performance and disclosures. Advances in Accounting 27: 223–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, Josephine, Zakaria Ali Aribi, and Godfrey C. Uzonwanne. 2016. Corporate governance: The impact of director and board structure, ownership structure and corporate control on the performance of listed companies on the Ghana stock exchange. Corporate Governance 16: 259–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, Diane K. 2001. Twenty-five years of corporate governance research… and counting. Review of Financial Economics 10: 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkor-Hyiaman, Kenneth, Erika Anneli Pärn, De-Graft Owusu-Manu, David J. Edwards, and Clinton Aigbavboa. 2019. Pension reforms, risk transfer and housing finance innovations. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 34: 1149–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dorfman, Mark. 2015. Pension Patterns in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review 14: 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R. Susan, and Lester W. Johnson. 1993. Agency theory as a framework for advertising agency compensation decisions. Journal of Advertising Research 33: 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, Eugene F. 1980. Agency problems and the theory of the firm. Journal of Political Economy 88: 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene F., and Michael C. Jensen. 1983. Agency Problems and Residual Claims. The Journal of Law and Economics 26: 327–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarakis, Grigoris. 2014. Corporate governance and financial characteristic effects on the extent of corporate social responsibility disclosure. Social Responsibility Journal 10: 569–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, Arthur A. 1995. The State, The Market and Economic Development: A Second Look at Adam Smith in Theory and Practice. Development and Change 26: 633–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Prashant Kumar, and Seema Sharma. 2022. Corporate governance determinants of asset quality in an emerging economy: Evidence from Indian banks. Journal of Advances in Management Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, Jerry A. 1978. Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 46: 1251–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hill, Charles W. L., and Thomas M. Jones. 1992. Stakeholder-agency theory. Journal of Management Studies 29: 131–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Chi-Kun. 2005. Corporate Governance and Corporate Competitiveness: An international analysis. Corporate Governance: An International Review 13: 211–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, Ioannis, and George Serafeim. 2012. What drives corporate social performance? The role of nation-level institutions. Journal of International Business Studies 43: 834–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jackson, Gregory. 2005. Stakeholders under Pressure: Corporate governance and labour management in Germany and Japan. Corporate Governance: An International Review 13: 419–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara, Mauricio, Félix López-Iturriaga, Pablo San Martín, Paolo Saona, and Giannina Tenderini. 2019. Chilean pension fund managers and corporate governance: The impact on corporate debt. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 48: 321–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Hoje, Hakkon Kim, and Kwangwoo Park. 2014. Corporate Environmental Responsibility and Firm Performance in the Financial Services Sector. Journal of Business Ethics 131: 257–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. Burke, and Anthony J. Onwuegbuzie. 2004. Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educational Researcher 33: 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, Thomas M., and Nadrew C. Wicks. 1999. Convergent stakeholder theory. Academy of Management Review 24: 206–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakabadse, Nada K., Catarina Figueira, Katerina Nicolopoulou, Jessica Hong Yang, Andrew P. Kakabadse, and Mustafa F. Özbilgin. 2015. Gender diversity and board performance: Women’s experiences and perspectives. Human Resource Management 54: 265–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kato, Kazuo, Meng Li, and Douglas J. Skinner. 2017. Is Japan Really a “Buy”? The Corporate Governance, Cash Holdings and Economic Performance of Japanese Companies. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 44: 480–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Mark Thomas. 2008. Getting counted: Markets, media, and reality. American Sociological Review 73: 270–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Arifur, Mohammad Badrul Muttakin, and Javed Siddiqui. 2013. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Journal of Business Ethics 114: 207–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korac-Kakabadse, Nada, Andrew K. Kakabadse, and Alexander Kouzmin. 2001. Board governance and company performance: Any correlations? Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 1: 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewski, Oskar. 2016. Corporate governance and corporate performance: Financial crisis (2008). Management Research Review 39: 1494–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kpessa-Whyte, Michael W. 2011. A comparative analysis of pension reforms and challenges in Ghana and Nigeria. International Social Security Review 64: 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kpessa-Whyte, Michael, and Kafui Tsekpo. 2020. Lived Experiences of the Elderly in Ghana: Analysis of Ageing Policies and Options for Reform. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 35: 341–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, Prity, and Jamini K. Pattanayak. 2017. Linking earnings management practices and corporate governance system with the firms’ financial performance: A study of Indian commercial banks. Journal of Financial Crime 24: 223–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattemann, Christoph, Marc Fetscherin, Ilan Alon, Shaomin Li, and Anna-Maria Schneider. 2009. CSR Communication Intensity in Chinese and Indian Multinational Companies. Corporate Governance: An International Review 17: 426–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Woody M., Chia-Chi Lu, and Hsuan Wang. 2014. Venture capital, corporate governance, and financial stability of IPO firms. Emerging Markets Review 18: 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCahery, Joseph, Zacharias Sautner, and Laura T. Starks. 2016. Behind the Scenes: The Corporate Governance Preferences of Institutional Investors. The Journal of Finance 71: 2905–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, Gardiner. 2017. The Modern Corporation and Private Property. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, Charles. 2013. Pension Contributions and National Savings in Ghana. Trends, Prospects, and Challenges. Ph.D. thesis, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana. [Google Scholar]

- Mitnick, Barry M. 2015. Agency theory. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Glenn, and Peer Hull Kristensen. 2006. The contested space of multinationals: Varieties of institutionalism, varieties of capitalism. Human Relations 59: 1467–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mpinga, Zubeda Chande, and Wim Westerman. 2017. Public Pension Fund Structure And Mechanisms: A Case Study Of The Tanzanian Pension Funds System. Central European Review of Economics and Management 1: 135–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NPRA. 2015. Annual Report; Accra: National Pensions Regulatory Authority.

- NPRA. 2022. Contact Details of NPRA’S Registered Pension Fund Managers; Accra: National Pensions Regulatory Authority.

- OECD. 2004. OECD Principles of Corporate Governance. Paris: OECD, pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, Hieu V., and Shantaram P. Hegde. 2012. Pension Contributions and Firm Performance: Evidence from Frozen Defined Benefit Plans. Financial Management 42: 373–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, Deborah E., Jyoti Ganapathi, Ruth V. Aguilera, and Cynthia A. Williams. 2006. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 27: 537–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, Khaled, Khaled Dahawy, Khaled Hussainey, and Pamela Stapleton. 2012. The extent of corporate governance disclosure and its determinants in a developing market: The case of Egypt. Advances in Accounting 28: 168–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, Heibatollah, Justin Wang, and Haiyan Zhou. 2011. Corporate governance and operating performance of Chinese listed firms. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 20: 106–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, Susan P. 2005. Agency theory. Annual Review of Sociology 31: 263–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škare, Marinko, and Tea Hasić. 2016. Corporate governance, firm performance, and economic growth–theoretical analysis. Journal of Business Economics and Management 17: 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soana, Maria-Gaia. 2011. The Relationship Between Corporate Social Performance and Corporate Financial Performance in the Banking Sector. Journal of Business Ethics 104: 133–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, Fiona, and Juan Yermo. 2009. Pension fund governance. OECD Journal: Financial Market Trends 2008: 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafeas, Nikos. 1999. Board meeting frequency and firm performance. Journal of Financial Economics 53: 113–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafeas, Nikos, and Adamos Vlittis. 2016. The Association between Board Composition and Corporate Pension Policies. Financial Review 51: 481–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafeas, Nikos, and Adamos Vlittis. 2019. Board executive committees, board decisions, and firm value. Journal of Corporate Finance 58: 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gyampo, Ransford Edward, Emmanuel Graham, and Eric Yobo. 2017. Ghana’s 2016 general election: Accounting of the monumental defeat of the National Democratic Congress (NDC). Journal of African Elections 16: 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersema, Margarethe F., and Karen A. Bantel. 1992. Top management team demography and corporate strategic change. Academy of Management Journal 35: 91–121. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).